January 16, 2026

Air Date: January 16, 2026

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Ices Climate Diplomacy

/ Marianne LavelleView the page for this story

The Trump Administration recently announced plans to withdraw the United States from dozens of United Nations treaties and organizations including the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, a treaty that was ratified by the US Senate in 1992 and is the key international forum for addressing the climate crisis. Marianne Lavelle, the Washington Bureau Chief for Inside Climate News, speaks with Host Jenni Doering about what this decision could mean for global climate progress. (14:52)

Western Water Crisis Boiling Over

View the page for this story

The Colorado River provides water to seven western states, and there is not enough to go around. Recently the federal government ordered the states to agree on a plan on how to share what's left amid a worsening drought. Luke Runyon co-directs The Water Desk at the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism. He joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss the challenges of allocating water resources when demand continues to outstrip supply. (13:14)

Choosing Nonviolence: MLK and Nature

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The nonviolent resistance preached by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was far from passive. It required peaceful confrontation and fierce courage to protect Black Americans from the constant threat of racist violence. Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence, Mark Seth Lender sent us this essay about an encounter in Yellowstone National Park years back that reminded him of a story he heard from one of Dr. King’s defenders. (03:48)

Fungi and Climate Resilience

View the page for this story

Mycorrhizal fungi form intricate and vital partnerships with plants through enormous underground networks that could help ecosystems and agriculture withstand climate impacts. But these fungi are threatened by habitat loss, nitrogen pollution and more. 2025 MacArthur Fellow Toby Kiers is leading fungi research and conservation efforts. She shares with Host Jenni Doering the wonders of fungi and why they’re worth protecting. (15:01)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

260116 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Paloma Beltran

GUESTS: Toby Kiers, Marianne Lavelle, Luke Runyon

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The US federal government abandons international climate diplomacy.

LAVELLE: The Trump administration has decided it's really not in our interest, not only to have any concern about climate change, but to cooperate and dialog with other nations.

DOERING: Also, cooperation and partnerships are at the core of the incredible world of fungi.

KIERS: There’s really a need right now to focus on what we call the 3 “Fs”. So we used to just say “flora and fauna.” But now we’re saying “flora, fauna, and funga.” It’s really important for conservation efforts around the world to embrace that third “F”.

DOERING: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Ices Climate Diplomacy

President Trump recently announced the United States’ withdrawal from over 60 international treaties and organizations. (Photo: Matt H. Wade, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The Trump Administration recently announced plans to withdraw the United States from over 60 international treaties and organizations, many of which concern climate change. One of them is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or UNFCCC, a treaty that was ratified by the US Senate in 1992 and is the key international forum for addressing the climate crisis. The US will also bow out of UN Water, UN Oceans, the International Energy Forum, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change or IPCC, which provides vital reports on the state of climate science every few years.

Joining us now to discuss is Marianne Lavelle, the Washington Bureau Chief for our media partner Inside Climate News. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Marianne!

LAVELLE: Glad to be here with you, Jenni.

DOERING: What rationale is the Trump administration providing for withdrawing from all of these different organizations and treaties?

An event at COP30, “Connecting solutions and accelerating implementation actions,” took place in Brazil in 2025. One of the treaties the US will exit is the UN Convention on Climate Change, or UNFCCC, which is the treaty which forms the basis for the annual Conference of the Parties climate meetings. (Photo: hlcchampions, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

LAVELLE: Well, the announcement simply said, they are no longer in the US interest. And what that means is the Trump administration has decided it's really not in our interest, not only to have any concern about climate change, but to cooperate and dialog with other nations. And it seems very significant that this happened on the same week as the invasion into Venezuela, which was just a very unilateral move. All of the ground rules that we have, these agreements that really have been the way we function, that we get to influence the direction of policy worldwide. Just the idea that we walk away from that table is really quite dramatic, since we are the country that it took the lead in establishing the world order after the devastation of World War Two, deciding that cooperation is better than war. And on climate change, it's a recognition that this is a global problem that one country cannot solve alone, and often the US role has been to slow down action more than other nations have wanted to move and it's just striking that even that amount of leverage the President has decided is no longer needed.

DOERING: This latest action certainly seems far beyond the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Climate Agreement, which President Trump has done twice now. So what's the impact of the US exiting virtually all international cooperation on climate?

At the start of Donald Trump’s second term, he pulled the United States out of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. On January 7th, 2026 President Trump also formally withdrew from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, logo shown above) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (Photo: UNclimatechange, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LAVELLE: I think that most analysts believe that another country, likely China, will go into that leadership vacuum and really be the country that steers the future direction, and that's not necessarily great for addressing climate change. China still is a very big emitter of fossil fuels. However, it also is a huge, huge investor in alternatives to fossil fuels, and world leader in electric vehicles, in solar and wind energy, and just the fact that it will have a stronger hand in leading the way the rest of the world goes will affect us, but we won't really have a say in the negotiations on how fast we decarbonize.

DOERING: What do you think are some potential economic consequences of eliminating the US from these kinds of international conversations about climate?

LAVELLE: Any company that is doing business globally with other countries that do have climate goals in place are going to be at a disadvantage because they won't have their government kind of at the negotiating table, you know, making the case for them. One really clear example of that is that the European countries are planning to put into place these carbon border adjustments, and that could be an area where really negotiation would be needed to be able to export their goods into Europe. So that's just one example of how this really could affect US companies. Most of these multinational companies would like to be selling across all markets, not just in the US.

DOERING: Marianne, what's the practical impact of the US withdrawing from the world's main climate science body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC?

Many U.S. scientists have continued their work with the IPCC despite the federal government’s withdrawal from the UN body. Scientists are often funded by or affiliated with U.S. universities including Harvard University, (pictured above) which have also been under attack by the Trump administration. (Photo: Rizka, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

LAVELLE: Yes, so that's a really interesting question, because right now, there are about 50 US scientists who are participating in the latest assessment. I think they actually had their first meeting in December, and all of the US scientists, and this is for the first time, I believe that this has happened, the US scientists are not government scientists. They're all with other universities or institutions. They're private citizens, really, who are participating. It's kind of a volunteer sort of thing, but this is what they're doing on their own. Does the US have any way of stopping them? I don't think so. But does the Trump administration have leverage over their institutions? Obviously, the Trump administration has done that. We've seen what it did to Harvard and Columbia over the last year, so I think we have to see what's really going to happen. The US scientists have so much to contribute to that assessment. They, in many cases, are leaders in these realms of science. And there's so many realms of science involved, from energy technologies to marine science to weather and atmospheric science. It's not clear that these US scientists can be stopped from participating, but pressure can be put on them, and it can just kind of change the whole cooperative flavor of the IPCC.

DOERING: Now, I know this is a huge question, but what do you think withdrawing from these organizations and treaties means for the climate?

China currently leads the world in renewable energy development, giving it greater leverage to steer global climate action while the U.S. retreats from that world stage. (Photo: Roy Bury, Wikimedia Commons, CC0 1.0 Universal)

LAVELLE: It definitely remains to be seen. It is clear that the Trump administration's bet or wager is that without the United States, the Framework Convention, all of the world action on climate can't really go anywhere. He made that clear when he spoke at the UN last fall. He called Climate Change a con job. He wants other countries to stop their action on climate, and he wants them to buy us natural gas, for instance, and US oil. So that's one possible scenario that, you know, it all falls apart, and we don't have a world that worries about climate change. I think that that's a pretty unlikely scenario. I think despite everything the US has done to drag its feet over the last few years, Europe and Asia have really moved forward into clean energy technologies and decarbonization. I think that that is the future, and it makes the US have less of a hand in shaping the global future.

DOERING: Of course, when the first Trump administration pulled the US out of the Paris Agreement, a bunch of cities, mayors, businesses, organizations, they said, we are still in and they sort of formed a coalition around that. And so similarly, as we see the US pulling out of the underlying UN Framework Convention on Climate Change that dates all the way back to 1992, to what extent do you think local organizations and local governments within the US will try to step up and keep participating in these international forums on climate?

LAVELLE: Well, this was the biggest response that we heard when this happened, was state and local governments saying, we're still in, and we're setting our goals and we're taking action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and I know that they will continue with that work. However, what's different this time than last is that the Trump administration is actually aggressively going after the states and local governments to argue in court that they do not have the legal authority to act. For example, there are some ordinances in California that new buildings need to be electric, not using natural gas. The Trump administration sued two of those communities last week. At the same time, the Trump administration is suing New York and Vermont and Hawaii, which are all trying to have climate change laws.

The U.S. remains the world’s largest historical greenhouse gas polluter. Its withdrawal from global climate treaties also raises questions about how the fight against the climate crisis will be financed. (Photo: tokage.shippo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Yeah, these are the like "Climate Superfund" laws, I think you're referring to.

LAVELLE: Right, that New York and Vermont have "Climate Superfund" laws. So the Trump administration is saying those laws are illegal. So you have to watch, because this is a really multi-pronged effort. The Trump administration is not just saying, hey, we're not going to do anything about climate change at the federal government. They're trying to stop states from acting. And in a real sense, through this withdrawal from the international treaties and organizations, the Trump administration is trying to stop the rest of the world from acting on climate change. It's like a multi-pronged strategy.

DOERING: And by the way, Marianne, what's the legal basis for the President of the United States to do this alone, to pull out of all of these organizations and treaties by himself? The UNFCCC was ratified by the US Senate in 1992, so for example, does the Senate need to give its consent for withdrawal?

Under the Constitution, the U.S. can join a treaty only if it is ratified by a ⅔ vote in the Senate, but there are no constitutional rules for withdrawing from one. Many scholars have questioned the legality of Trump’s withdrawal from global treaties like the UNFCCC without obtaining Senate approval. (Photo: ttarasiuk, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LAVELLE: These are all questions that are yet to be answered, and the fact that the Trump administration is taking this action means that it wants to test the legality or test really the meaning of the constitutional requirement that the Senate ratify international treaties. Under the Constitution, the US cannot enter into a treaty without ratification by the Senate, a vote by more than two thirds of the Senate, but it never has been tested of whether the President can exit a treaty that the Senate has already approved and ratified just on his own. If he can, it really dilutes the meaning of ratification. And the Trump administration most certainly will face a legal challenge over this, and it could very well be an issue that goes all the way up to the Supreme Court. And you know, depending on how it rules, that could really change the landscape on international treaties in the future.

DOERING: What are the stakes of the US, a major economic power, still a superpower, what are the stakes when it comes to us walking away from climate and international cooperation?

Marianne Lavelle is the Washington Bureau Chief for our media partner, Inside Climate News. (Photo: Courtesy of Marianne Lavelle)

LAVELLE: Well, it's very harmful to the credibility of the whole process. If the largest historic contributor to world greenhouse gasses isn't doing anything about its greenhouse gasses, how do you urge other countries to act when it's not going to have any impact compared to the impact if the US reduced its emissions. Also just finance for those countries that did almost nothing to cause the climate crisis but are feeling the worst effects. One of the most hotly negotiated things over the last ten years has been to get some relief and funding for those countries, if for no other reason than to stop the climate migration crisis that is ahead of us if we don't do anything. So there's lots of good, self interested reasons for the United States to be involved in doing something about climate change, and I'm not sure that just asserting, it's not a problem, is going to prevail when, obviously, the impacts are already happening all over the world.

DOERING: Marianne Lavelle is the Washington bureau chief for our media partner, Inside Climate News. Thank you so much as always, Marianne.

LAVELLE: Thank you, Jenni, glad to be here.

Related links:

- U.S. Department of State | “Withdrawal from Wasteful, Ineffective, or Harmful International Organizations”

- The White House | “Withdrawing the United States from International Organizations, Conventions, and Treaties that Are Contrary to the Interests of the United States”

- The White House | “At UN, President Trump Champions Sovereignty, Rejects Globalism”

- Heatmap | “Can Trump Exit a Senate-Approved Treaty? The Constitution Doesn’t Say.”

- European Commission | “Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)”

- National Security Archive

- Earth.org | “A Closer Look at the ‘Climate Superfund’ Laws Trump Is Threatening to End”

[MUSIC: Grant Green, “Maybe Tomorrow” on Visions, Capitol Records, LLC]

BELTRAN: Coming up, Climate change is drying up a thirsty West. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Grant Green, “Maybe Tomorrow” on Visions, Capitol Records, LLC]

Western Water Crisis Boiling Over

The Colorado River snakes through desert canyons in the American Southwest, supplying drinking water and irrigation for the region’s cities. (Photo: Alexander Heilner, The Water Desk with support from LightHawk)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

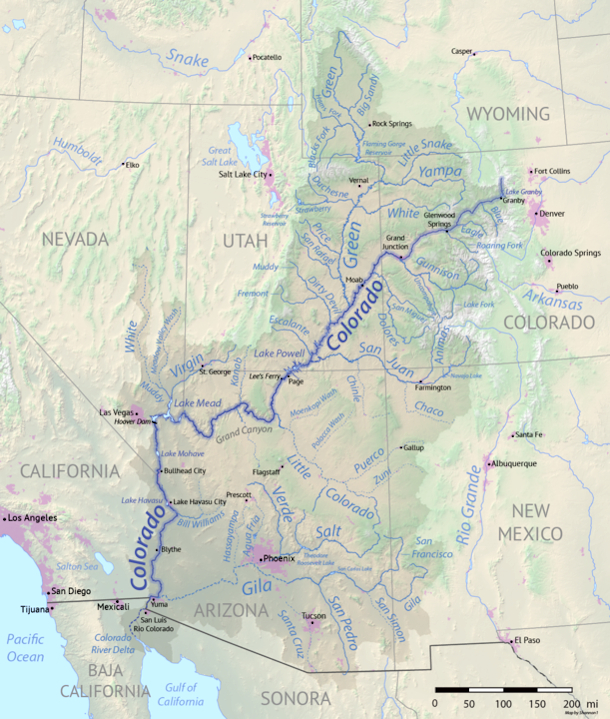

The Colorado River provides water to seven states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. But the river has been overtaxed for decades. And recently the federal government ordered the states to come up with a plan on how to share the river amid a worsening drought. Lakes Mead and Powell, the two largest reservoirs on the Colorado River, are less than a third full, threatening both energy generation and the critical water supply for the population in the West. The river is also a lifeline for the region’s farmers, who need about 80 percent of the diverted water to grow crops.

Luke Runyon has covered issues in the Colorado River Basin for a decade. And he is co-director of The Water Desk at the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism and he joins me now. Luke, welcome back to Living on Earth.

RUNYON: Thanks for having me.

BELTRAN: Why is the Colorado River Basin considered to be in a state of crisis?

RUNYON: Well, the Colorado River is a really critical water supply for really the entire southwestern region. So about 40 million people rely on the Colorado River for drinking water supply; most of the major cities in the Southwest — Denver, Albuquerque, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, Phoenix — rely on the river for some amount of its drinking water. It's also a really critical agricultural water supply. Some really productive farmlands in Southern California, Arizona, throughout the Southwest, rely on the river for irrigation water to grow food. And the big issue on the river right now is that our demand is outstripping the supply, and there's not enough water to go around. We've over allocated the Colorado River. We've known that we've over allocated the river for a long time, and really now the rubber is meeting the road in terms of instituting cutbacks to make sure that that water supply and demand is balanced.

The Colorado River basin. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed, while California, Nevada, and Arizona make up the lower watershed in the US. The Mexican states of Sonora and Baja California use water from the river as well. (Photo: Shannon1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: What role does a warming climate play in worsening this crisis?

RUNYON: It plays a huge role, partly because it's speeding up conversations that needed to be had decades ago on the Colorado River. The Colorado River has been over allocated since its kind of foundational legal documents were signed back in 1922. The river never had enough water to satisfy all of the demand. As infrastructure was built out over the decades, that demand eventually outstripped the supply. So, we would be having an issue on the Colorado River, regardless of climate change. What climate change is doing is limiting the supply even further, and kind of catalyzing all of these discussions that are taking place around conservation. The way that that plays out on the ground is that climate change is upending how the water cycle in the Southwest functions. The Colorado River is snow fed. We know that less snow is falling in the southern Rocky Mountains. We're getting more precipitation as rain instead of snow. That has a huge effect on how the Colorado River behaves as in water supply and as an ecosystem. And the warming temperatures are also having all sorts of other knock on effects, like reducing soil moisture, so the ground that the snow falls on ends up acting like a dried out sponge, soaking up more of that snow when it eventually melts off, meaning it doesn't end up in streams and reservoirs. And so the warming temperatures have such a profound effect on how the water systems in the Southwest function, and we're really grappling with, how do we manage a system that is undergoing so much rapid change?

BELTRAN: Several years ago, there was an emergency agreement pushed by the Biden administration for Arizona and California to reduce their usage. Where does that agreement stand?

RUNYON: Well, leaders throughout the Southwest have come up with agreements over the past 25 years to try and address some of the issues that are going on in the Colorado River, namely, the scarcity, the water scarcity that we're seeing. And a set of guidelines were passed back in 2007— that's the operating guidelines that the river is currently under that guide how its largest reservoirs are managed. And after those guidelines were passed, conditions continued to worsen. And in the subsequent years, federal leaders, state leaders, would come back together every now and then to continue to kind of deal with that ongoing crisis. The latest agreement was this, it’s called the Lower Basin Plan, and came together a few years ago during the Biden administration. And it was really an effort amongst the Lower Basin states, California, Arizona and Nevada, to rein in their water use. But what we found is that even though there are some cutbacks that have taken place on the Colorado River, they're not enough. The supply is shrinking faster than we're able to curb our demand, and so the cutbacks that are needed now are significant in order to balance the supply and demand on the river.

Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, is a key piece of storage infrastructure for Los Angeles, Phoenix, and agricultural areas in both the U.S. and Mexico. (Photo: Ross Rice, The Water Desk with support from LightHawk)

BELTRAN: The annual Colorado River Basin Conference was held in Las Vegas in December. Negotiators from seven states were there. What was the mood at the gathering? You know? What were some of the highlights coming out of that conference?

RUNYON: I thought it was kind of like Groundhog Day, because the situation on the Colorado River hasn't really changed in the past year in terms of policy. The conditions on the river have actually gotten much worse. But this is an annual conference that takes place in Las Vegas every year, and you get everyone who cares about the Colorado River all in one place. And the situation on the river is reaching a really critical point, but the policy to actually manage the crisis in this current moment is not there. And what you get is a kind of really interesting interplay, and kind of a peek into the politics of water into the southwest, because the current issue that's going on on the river is that there is the set of guidelines, these 2007 operating guidelines that expire this year. And so the states on the river are trying to negotiate a future set of managing guidelines. And every now and then, the federal government, which operates these large dams that the Colorado River has, like Hoover Dam near Las Vegas, Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona, those dams are under threat of losing the ability to generate hydropower. So the federal government has an interest here in order to keep producing hydropower at these large dams. And the current stalemate when it comes to policy really comes down to who has to take cutbacks to their water supply under what condition and how much water are they talking about reducing their use of? And that's a really difficult conversation to have, because people see water as their future. States see water as an economic driver, whether that's for agriculture, whether that's for development and residential growth, whether that's for industrial growth. We've heard lots about data centers popping up in the Southwest. So leaders see access to water as the kind of foundation that the rest of their economy is built on. And so when you're talking about reducing the amount of water, people immediately think, how am I going to grow my economy without enough water, without access to this kind of foundational aspect of our society?

The Colorado River has been in a state of crisis for years due to a warming climate and increasing drought conditions. (Photo: G. Lamar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: What are some successful examples of people using less water across the West?

RUNYON: A lot of it has come from, you know, kind of in different pockets, whether you're talking about farms or cities. In cities, it's been people replacing their old toilets in their homes that would maybe use like four gallons a flush. Well, you get a new toilet, it uses one gallon a flush or less. That's one small way that people can make an impact. It could be ripping out your front lawn and replacing it with water-wise landscaping, your zero scape landscaping. For farmers, it might mean changing your irrigation practice from flood irrigation, where you send water over an entire pasture, to something where you're moving to a sprinkler system that uses a lot less water. For large cities, sometimes that means installing, you know, a water recycling plant where you're treating your effluent, your wastewater, and making it drinking water again. We have the technology to do that these days, and so it really is just kind of it varies across the entire basin depending on what your resources are, what your needs are, how you might go about using less water.

BELTRAN: And we're talking about seven states here across the Colorado River Basin, you know, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and California. Some of these states are red and others are blue. How does politics play a role in this debate?

Luke Runyon is the co-director of The Water Desk at the University of Colorado Boulder. (Courtesy of Luke Runyon)

RUNYON: Well, water is one of those interesting issues that doesn't fit neatly into our partisan divides that pop up in almost every other issue in American life these days. More often than not, it pops up in sort of a rural, urban divide. And so you do, you have kind of a mix of really conservative states and really liberal states. You know, everywhere from Wyoming, one of the most conservative states in the country, down to California. So it is an issue that doesn't neatly fit into those kind of paradigms that we have, blue state, red state. And I think, you know, I mentioned that the federal government is involved in some of these talks as well. I think the federal administration does not really know how to make this a partisan issue, which is why they've kept an arm's length at some of these negotiations. I think if it was one of those issues that neatly fit into our partisan politics, they would have already turned it into a partisan issue, but instead of have kind of kept this whole debate at arm's length and are really letting the states kind of guide the discussion.

BELTRAN: What are the major obstacles to finding a viable plan here?

RUNYON: The obstacles are huge. I mean, you you have this is sort of something that is in the psychic mentality of how the Southwest was settled. You know, these kinds of fanciful ideas of how much water the Colorado River could provide. And you know, this is a huge paradigm shift for the region too. For decades, the conversation in the Southwest has been, how much more water can we get from the Colorado River? Where's the next big infrastructure project? Where's the next straw going into the river to draw for name your big metropolitan area? That has shifted very recently. No one is talking about big new projects in terms of additional water supply, and that's because there's just not the water to meet the need. And that is a massive paradigm shift for the entire region, because it moved from where does my next drop of water from the Colorado River come from, to Oh, no, I don't have enough water. No one has enough water, and we all have to reduce our use. That's a big shift in the mentality of leaders in the Southwest, and it's taking place right now.

BELTRAN: To what extent has Manifest Destiny been a part of the conversation around water use across the West?

Antelope Point marina is located in the dwindling Lake Powell, the nation’s second largest reservoir and a crucial part of the Colorado River water supply. (Photo: Alexander Heilner, The Water Desk with support from LightHawk)

RUNYON: I think it's huge. I mean, you know, this is a very arid region that was settled by European colonizers back in the late 1800s, early 1900s with federal incentives for land and agriculture. And when the kind of initial management conversations were happening around the Colorado River, around the turn of the century, the 1920s, no one was talking about the environment. No one was talking about the needs for Native American tribes. No one was talking about the needs for recreation and a recreation-based economy. It was all about consumptive use for agriculture and for cities. And so over the subsequent century, what we've seen is that those other powers, those other interests on the river are trying to assert themselves and really kind of stake a claim, saying, like, we deserve access to water too. The river itself deserves to have some allocation of water that it's not just a water supply, it's an ecosystem. It's a, it's an environmental force in in our region. And so I think that that conversation continues to today.

BELTRAN: Luke Runyon is a veteran journalist and co-director of The Water Desk at the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism. Luke, thank you so much for joining us.

RUNYON: And thanks so much for the conversation. I had a great time.

Related links:

- Read more on how the federal government is planning to address a dwindling Colorado River.

- KUNC | “Feds Publish Possible Playbook for Managing Dwindling Colorado River Supply”

- Look into the new guidelines for operations at the Colorado River post 2026.

- Learn more about the work of The Water Desk.

[MUSIC: John Denver, “I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to Be Free” on Rhymes & Reasons, Sony Music Entertainment]

Choosing Nonviolence: MLK and Nature

Valerie Elaine Pettis, artist and wife of Mark Seth Lender, draws the grizzly spotted in Yellowstone National Park. (Photo: © Valerie Elaine Pettis)

DOERING: As the US honors the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who paid the ultimate price for advancing civil rights in this country, we remember that the nonviolent resistance he preached was far from passive. It required peaceful confrontation and fierce courage to protect Black Americans from the constant threat of racist violence.

Explorer-in-Residence, Mark Seth Lender sent us this essay about a moment in Yellowstone National Park years back that reminded him of a story he heard from one of Dr. King’s defenders.

Non Violence

Grizzly Bear, Yellowstone National Park

Homo Sapiens, Bogalusa, Louisiana

© 2026 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

From the top of the hill the land falls off into a gulley where water in a thin cold stream cuts through, and on the other side a gradual grassy rise. There at the high point a young grizzly is feeding. It is impossible to tell what he is feeding on because he is standing on it, all fours. Newly awake from a winter of forty, fifty below for months he’s been feeding on himself. Now it is someone else’s turn. To be fed upon. He is not about to lose possession of this first meal. He rips and tears and every few seconds when he raises his head to swallow, he scowls. Brow furrowed, eyes screwed tight. Jaws working once twice. He does not need any more than this to make his point: I want to rip your head off. The subtext being, Try to take what is mine, from me, and I will.

There is more to the message than that. And it reminds me of something.

I met Charles Sims a couple of times in the late 1960’s. He was the president of the Bogalusa Deacons for Defense and Justice and one of its founders. Low to the ground, broad chested, intense; everything about him said: not to be messed with. I liked him very much. He liked me too or he wouldn’t have bothered with me. Still, it wasn’t until the second time we saw each other that he opened up a little. This is the story he told me.

Martin Luther King was on his way to Mississippi by way of Bogalusa, planning to spend the night. The Deacons had found a house for him, on the edge of town because they did not want anyone to know he was there. The Ku Klux Klan found out, anyway. And Charlie Sims found out about that. When the Klan came around the corner that same evening they saw a line of black men, seven or eight, no more than that, very calm, standing in front of the porch between them and Dr. King and each of them had a shotgun in the crook of his arm. The mob became very, very quiet, Charlie said, and they kind of, looked at their feet, and went back the way they came.

Charles Sims and the Bogalusa Deacons for Defense and Justice saved the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr.’s life that night. And not for the last time.

Nonviolence as practiced by Charlie Sims and by grizzly bears is violence held back, an invisible cordon, a boundary written on the air that must not be crossed.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related link:

Visit Mark Seth Lender’s website.

[MUSIC: Wynton Marsalis Septet, Wynton Marsalis, Susan Tedeschi, Derek Trucks, “I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to Be Free – Edit” Single, Jazz at Lincoln Center, Inc.]

BELTRAN: Just ahead, The incredible ancient partnerships between plants and fungi. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander — celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility — who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: RYUTO KASAHARA, THE SOUL EATERS, “I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to Be Free – Instrumental” Single, INSENSE MUSIC WORKS INC. / Arigata record]

Fungi and Climate Resilience

Toby Kiers is a 2025 MacArthur Fellow and a cofounder of SPUN, the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks. (Photo: Seth Carnill)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

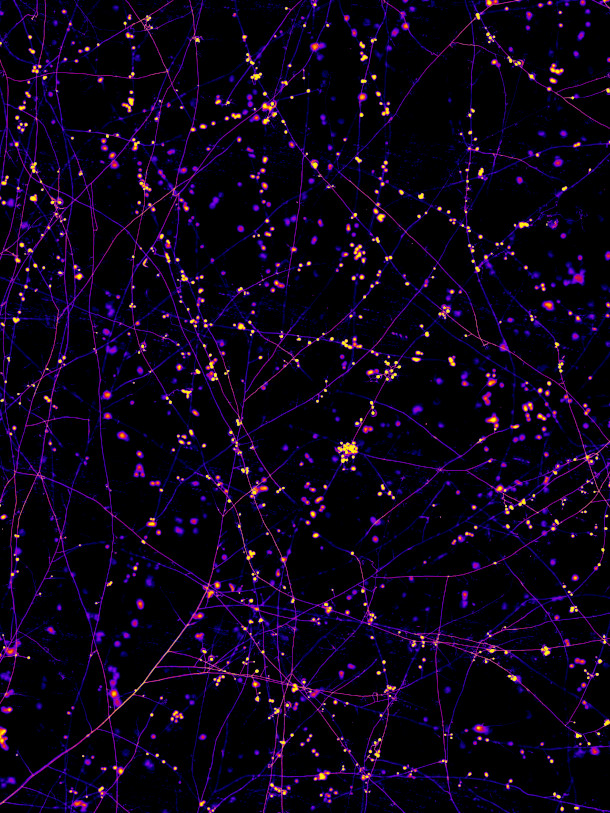

When most of us think of fungi we probably picture the mysterious mushrooms growing in our backyards, or the yeast in our sourdough starter. But for 2025 MacArthur Fellow Dr. Toby Kiers, fungi are at the root of our entire world, literally. Toby studies mycorrhizal fungi, which form intricate and vital partnerships with plants through enormous underground networks known as mycelium. Just a gram of soil, about a quarter teaspoon, can contain nearly 300 feet of mycelium. But habitat loss, nitrogen pollution, and more are endangering these amazing networks. So, much of Toby Kiers’ work revolves around researching and protecting them, and she’s here with me now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth, Toby!

KIERS: Thank you so much for having me.

DOERING: And by the way, congratulations.

KIERS: Thank you. Such incredible news.

DOERING: So I'm not sure that people understand just how much plants depend on fungi. Talk to me about this incredible relationship.

KIERS: Yeah, fungi, they really lie at the base of life on Earth. They're key ecosystem engineers, and one of the most important roles they play, I think, is to build soil. So if you think about our soils, right, they store about 75 percent of terrestrial carbon, and you're not going to believe this number, but they also contain about 59 percent of the Earth's biodiversity, so a huge amount of biodiversity underground. And all of this life is possible because of a class of fungi called mycorrhizal fungi. That's a big word, mycorrhizal fungi, but mycos means fungi, and rhizal means root. And these are basically network forming fungi that associate with plants. It's not just some plants. It's about 80 to 90 percent of all plant species. And if you were to picture these networks, they facilitate these very crucial exchanges. And so, as a result, you can kind of think of these fungi as like a circulatory system for the Earth.

DOERING: Toby, by the way, fungi, fungi, funga, what's the right way to pronounce this here?

KIERS: That's the beauty of the word, is that it can be pronounced any way that you feel comfortable, fungi, fungi. And anyway, it's a very inclusive word.

DOERING: And what exactly is this partnership between the plants and the fungi, like, what are they sending back and forth?

KIERS: This is a partnership based on carbon to nutrient exchange. So the plants are sending carbon down into the fungal network, and the fungi need that carbon to be able to survive, to build their bodies, to process energy. They need that plant carbon, but it doesn't come for free. In exchange, they are out collecting phosphorus and nitrogen and water and providing all kinds of benefits to the plant. So they put those nutrients in their network and send it up to the root system. And it's beautiful. If you were to actually look inside a root system, there's this structure called the arbuscule, and that's where the exchange of carbon and nutrients take place, and it's sort of like this beautiful tree like structure inside the plant cell.

DOERING: And each of these partners make sure that it's a fair trade, don't they?

KIERS: They do. So, over this evolutionary relationship that's about 450 million years old, both partners have evolved very clever strategies to be able to make sure that it's a fair trade. And it's not that it's fair every time, but just that on average, that both partners are benefiting from the relationship.

Kiers studies mycorrhizal fungi, which are primarily underground and form crucial partnerships with plants. In the photo above, the mycorrhizal mushroom Cortinarius albomagellanicus emerges from a hyper-diverse but hidden underground fungal community in Tierra de Fuego, Chile. (Photo: Mateo Barrenengo)

DOERING: So I think one of the most mind blowing aspects of this is realizing that I don't know these networks don't necessarily have a mind like we do, you know, like a centralized nervous system. Or maybe they do. I don't know. How exactly are these decisions being made? And what's driving this, I guess?

KIERS: Well, welcome to our lab. I mean, we spend most mornings waking up thinking, "How is information processed across a network that has no central nervous system?" I mean, growing up as biologists, I think we always think of intelligence as having a central nervous system, some sort of central processing, like in humans, like a brain. Fungi are very different, yet we know that they're able to engage in these very sophisticated trade strategies. What I mean by that is that through about 10 years of work, we've been documenting how they move resources in a way that really maximize the amount of carbon that they get from a plant system. So they'll do things like hoard nutrients in their network until they get a higher price, or they'll move it actively across the network to a place where demand is higher and they're able to get more carbon per unit phosphorus. So we've been doing these kinds of experiments for about 10 years that show these very sophisticated trade strategies. And so now the big question is, how do they do it? How are they sensing all the conditions, again, across billions of growing tips?

DOERING: So I imagine that while a lot of this research is taking place in your lab, to what extent do you have to go out and collect samples from all over the world, all kinds of different soil and and where is that happening?

KIERS: Well, this was the real motivation for starting SPUN. So SPUN stands for the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks. And it had a really like simple but audacious mission, and that's to actually go out and map the networks of mycorrhizal communities that regulate the Earth's ecosystems, and then start advocating for their protection. And so SPUN started, really, to transform how fungi are used in climate change strategies and conservation and restoration efforts. But to be able to do that, you need to map. You need to understand which mycorrhizal communities are where and what they're doing. So that's what we started doing. We, in 2021, we started working with researchers all over the world and local communities across, I guess, some of the most understudied ecosystems on Earth, and start generating these global data sets of what these fungi, who they are, and what they're doing.

Underground fungal networks are crucial to the vast majority of plant species’ survival, not just plants in forests or jungles. (Photo: Mateo Barrenengo)

DOERING: I mean, it sounds a lot like a network. I mean, it sounds like, literally, the form that SPUN has taken is something akin to the fungi networks that you're studying.

KIERS: It is. It's celebrating decentralized ways of doing science, and I think that's really important. It's really a celebration for decentralized ways of thinking and operating that fungi have mastered. So in this case, it's networks of scientists all over the world trying to analyze local patterns of underground biodiversity and then coming together to make this global map. And we're really excited about, even in the last four years, what SPUN and all of these researchers around the world has accomplished. Just in July, we published something called the Underground Atlas, which is a very cool resource for anybody to look up. And you can go and actually enter a location anywhere in the world. And what it does is zoom in on that location and give a prediction for mycorrhizal richness, which is a measure of biodiversity. So you can look at patterns all over the world of something that's been so hidden for so long. And I think what's important is that it's not just about this one idea of like, let's make a map, but instead, it's really about trying to use fungal data for applications, for everything from policy to litigation to land management. So restoration is an important field right now, and we know that restoration success could really be improved if people are also thinking about underground restoration and what underground fungal rewilding would look like. And so with this new map, what we can do is actually we can offer benchmarks for what we think an intact, healthy mycorrhizal biodiversity community should look like, and that can be used as a target for people that are working on degraded land trying to restore an underground ecosystem.

DOERING: Wow, yeah, it sounds like you don't just want this to be research that's interesting. You want it to make a difference in the world too.

KIERS: Yeah, exactly. And there's really a need right now to focus on what we call the three F's. So we used to just say flora and fauna, but now we're saying flora, fauna, and funga. It's really important for conservation efforts around the world to embrace that third F and start conserving fungi.

DOERING: So tell me more about climate change and fungi and how they could maybe be part of the solution, or a solution, at least, to helping us weather the storms ahead.

A photo of mycorrhizal fungi network. Mycorrhizal fungi form vast underground networks that transport nutrients in a way to maximize how much carbon the fungi receive from the plants. Despite the research, no one quite understands how the fungi do this without a central nervous system. (Photo: Loreto Oyarte Gálvez - VU Amsterdam)

KIERS: Well, we know that fungi lie at the base of life on Earth, and so we have to protect these fungi. The amount of carbon that is going down into mycorrhizal networks is astonishing, and we need to keep that circulatory system alive. Fungi create this scaffolding underground. You can really think of it as like a physical scaffolding that holds all of these underground ecosystems together, and if you lose that scaffolding, then these ecosystems wash away. And so when we're thinking about climate change and all of the global change that we're facing, fungi offer all kinds of solutions, whether it be to carbon drawdown to protection against pollutants and heavy metals, to sustainable sources of nutrients. They offer solutions that we just haven't considered before. So it feels like it's a great time to start collaborating with fungi.

DOERING: Could you please tell us a story, to give us a sense of what some of these projects that SPUN is undertaking, what they look like?

SPUN conducts research all over the world to map ecosystems’ fungal communities, including in difficult to reach places, like this forest in Ghana. (Photo: Natalija Gormalova)

KIERS: Of course. So some recent ones, recent expeditions that I've been working with are, for example, in Tunisia. Tunisia is an incredible country that's facing extreme changes as we face the climate crisis in terms of drought, and so we had an expedition with scientists in Tunisia to really understand the fungal communities that allow plants to adapt to extreme drought. So that involved collecting fungi right on the edge of the Sahara and trying to understand what was unique about these fungal communities that allowed plants to survive such harsh conditions. This is particularly important for agriculture. What are the fungi that are going to allow our crops to survive in the future as conditions get more and more extreme? In other cases, it's working with fungi that might be destroyed or lost to global change. We had a project with scientists in Ghana, for example, where we are trying to map the fungal biodiversity along the coast, Ghana's coast, which is facing extreme changes from sea level rise. So one worry that we have is that whole fungal communities are going to disappear. How do we protect those fungal communities? So in some cases, it's about leveraging and working with fungal communities, let's say, for agriculture, and in other cases, it's about drawing attention to really important fungal communities that may be lost and trying to protect — sort of, you could think of them as libraries of solutions — before they disappear.

DOERING: So what are some of the threats to underground fungal ecosystems, and how are they different from the threats to above ground ecosystems?

KIERS: Well, in some cases they're the same, and in some cases they're very different. So of course, a lot of these communities face threats from things that you'd normally think of, like deforestation, erosion, agricultural practices, but there's hidden dangers to fungal communities, things like nitrogen from the rainwater. The rainwater is becoming more and more nitrified, more and more nitrogen coming down in rainwater, and that really changes the balance between how much carbon that plants are going to feed to the fungi, if they're just getting so much nitrogen from the environment already. So they stop providing carbon to some of these mycorrhizal communities because they're getting so much nutrients already from the rainwater. And if there is this loss of carbon, then a lot of these fungal communities aren't surviving. So other things like dead wood, you know, you can think of some habitats where land managers are taking dead wood out of ecosystems, and that can really change the balance of which fungal communities survive. So there's a lot happening in terms of threats that are kind of hidden, that we don't really think about, for things that are underground. I think this is a real problem, though, the destruction of these underground networks. It can increase global warming. It can accelerate biodiversity loss. It can disrupt nutrient cycles. So there's a real urgency here. When we look at the work that SPUN has been doing, I think it's something like less than 0.02 percent of the Earth's surface has been mapped for mycorrhizal fungi.

DOERING: Oh my gosh!

KIERS: So there's a huge amount of work to do ahead.

DOERING: What do you think we humans can learn from these cooperative underground networks?

KIERS: Again, I think we can learn about how to work in a decentralized way. So much of our science until today has been very top down, and we haven't really embraced this way of collective learning, of how we learn across very diverse ecosystems and habitats and ways of thinking, and fungi are so good at that. So if there's one thing we can really do, it's embrace this decentralized way of learning and thinking.

DOERING: It's something we could really use in this world right now, I think.

KIERS: Exactly! It's this idea of partnerships, right? And partnerships are always fragile. So if you think about this partnership between plants and mycorrhizal fungi, there's always going to be a tension that the fungi really need a lot of carbon and the plants really need a lot of nutrients. But over time, there's this beautiful balance that emerges because of that tension. So we shouldn't be scared of tension that can really drive evolutionary innovation. It can drive all kinds of ideas. But at the base of that is a really healthy partnership.

DOERING: Toby Kiers is the university research chair and a professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolution at VU in Amsterdam. She's also a co-founder of the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks and a 2025 MacArthur Fellow. Thank you so much, Toby.

KIERS: That was so fun. Thanks so much.

Related links:

- Learn more about The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks.

- Read Toby Kiers’ MacArthur profile.

- Find out about the mycorrhizal fungi in your area by using the Underground Atlas.

[MUSIC: Tycho, “Melanine” on Dive, Ghostly International]

BELTRAN: Next time on Living on Earth, how gardening can help people with autism grow resilience and social skills.

MAYS: We always have a task to do, usually it’s reading, and a lot of times they begin with, oh, no, no, no, I don't want to touch the dirt and I'll say, I understand, all you need to do is five times. 1-2-3-4-5 Yay, you did a great job.

BELTRAN: That's next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Tycho, “Melanine” on Dive, Ghostly International]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Sophie Bokor, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Julia Vaz, El Wilson, and Hedy Yang. We bid a fond farewell this week to Daniela Faria and Melba Torres.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music,

And like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram, Threads, and BlueSky at living on earth radio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth