September 6, 2002

Air Date: September 6, 2002

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

From the World Summit in Johannesburg

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood reports from Johannesburg, South Africa on the outcome of the United Nation’s Summit on Sustainable Development. The summit ended on a mixed note. Many delegates called it an important first step in implementing lofty goals to curb global poverty and environmental degradation. But, most environmental activists labeled the meeting a failure, saying it was co-opted by corporate and U.S. interests. (13:00)

Almanac/Rio Summit

/ John RudolphView the page for this story

This week, reporter John Rudolph takes us back ten years to the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. After a last minute decision to attend the summit, the elder George Bush received criticism of his environmental agenda. (02:30)

White House P.O.V.

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood talks with James Connaughton of the White House Council on Environmental Quality. As one of the U.S. government’s representatives in Johannesburg, he discusses the Bush administration’s goals and accomplishments at the summit. (04:00)

Small Scale Nuke

/ Terry FitzPatrickView the page for this story

The South African government wants to build, what it claims is, a safer type of nuclear reactor. Pebble-bed reactors use different fuel than nuclear facilities currently online. What’s more, the government says, pebble-bed reactors are smaller and cheaper to build. They may be a way to supply developing nations with cheap power. But critics say the claim about safety is unproven. From Cape Town, Terry FitzPatrick reports. (08:30)

Solar Salon

View the page for this story

Renewable energy was a big focus in talks at this year’s Earth Summit. To test a possible application, Connecticut GOP Congressman Christopher Shays puts his hair where his mouth is and gets a solar-powered haircut. (03:00)

Health Note/Save the Children

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new initiative announced at the Johannesburg summit. The World Health Organization wants to cut the number of child deaths from environmental hazards. (01:20)

South Africa Water

/ Bob CartyView the page for this story

Water was a key issue at the sustainable development summit this year. Worldwide, more than a billion people do not have clean water to drink. South Africa has been able to distribute water to seven million people in seven years. But to do that, it has embraced a free-enterprise model for charging people, including the poor, for water. Bob Carty reports on whether using the market is the best strategy towards sustainable development. (08:25)

Corporate Accountability

View the page for this story

Though most environmental advocates call the summit in Johannesburg a failure, groups did manage to get language in the final document that could lead to a future international treaty on corporate accountability. Host Steve Curwood talks with Greenpeace representative from Brazil, Marcello Furtado, about this development. (04:00)

Voice of the People

View the page for this story

The 2002 Earth Summit may be over, but the talks are not. Conference attendees gathered together for a post-summit party in the spirit of the South African word "ubuntu," meaning "coming together for the common good." (03:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: John Rudolph, Terry FitzPatrick, Bob CartyGUESTS: James Connaughton, Rep. Christopher Shays, Marcello FurtadoUPDATES: Diane Toomey

(THEME MUSIC)

CURWOOD: From NPR News, it’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The world’s leaders come to Johannesburg, South Africa to answer a call for action for people and the planet.

MBEKI: We stand now ten years on from the Rio Earth Summit at the beginning of a new millennium. We see a world that is ailing from poverty, inequality and environmental degradation. We see a world that has pity neither for beautiful nature, nor for living human beings. This social behavior has produced and entrenches a global system of apartheid.

CURWOOD: Also, criticism of the agenda for public/private partnerships for development.

SHIVA: The summit has ended up being an auction house for selling the resources of the earth to the highest bidder, which happens to be giant multinational corporations.

CURWOOD: Conflict and compromise at the World Summit on Sustainable Development, this week on Living On Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWS]

From the World Summit in Johannesburg

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa.

[AFRICAN SINGING]

MBEKI: We welcome the peoples of the world to a place that is recognized as the cradle of humanity. The Johannesburg World Summit for Sustainable Development is, therefore, for all of us, a homecoming. A return to the place from where all humanity evolved to cover the globe.

CURWOOD: South African President Thabo Mbeki.

[AFRICAN DRUMMING]

CURWOOD: At a celebration on the eve of the summit, President Mbeki reminds the tens of thousands of people who have come to Johannesburg what’s at stake.

We’re here in the richest city in Africa where the shantytown legacies of apartheid reflect the growing gap between the poor and the prosperous around the world. And where urban sprawl and dirty air are daily reminders of an environment in crisis.

MBEKI: We stand now ten years on from the Rio Earth Summit at the beginning of a new millennium. We see a world that is ailing from poverty, inequality and environmental degradation, despite the agreements at the Rio Earth Summit. This is a world in which a rich minority enjoys unprecedented levels of consumption, comfort and prosperity, while the poor majority enjoys daily hardship, suffering and dehumanization. We see a world that has pity neither for beautiful nature, nor for living human beings. This social behavior has produced and entrenches a global system of apartheid. The suffering of the billions, who are victims of the system, calls for the same response that drew the peoples of the world into the struggle for the defeat of apartheid in this country. Our common and decisive victory against domestic apartheid confirms that you, the peoples of the world, have both the responsibly and the possibility to achieve a decisive victory against global apartheid.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Everyone at the summit seems to agree with the fundamental goals of helping the poor while protecting the environment. But as the delegates get down to business, the role of business itself is taking center stage with a long string of announcements of partnerships among the UN, national governments and corporations. They cover everything from hydroelectric power to clean water and sanitation projects in the developing world.

Sir Mark Moody-Stuart, the former chairman of Shell Oil, helped pull these initiatives together for the summit under the banner of Business Action for Sustainable Development.

MOODY-STUART: Business realizes that if we damage the environment, it damages our position. Now we come to realize that if we are not seen to be perceived as useful members of society, our long-term existence is also threatened. This is, could be seen as self-interested. It is in a sense self-interested, enlightened self-interest, I hope. And I don’t have any problem with enlightened self-interest.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you this, are there things that private business can accomplish in terms of environmental protection and social development that governments can’t?

MOODY-STUART: You can’t alleviate poverty by governmental charity or corporate charity alone. There just isn’t enough of it to go around. So we need investment and we need to be sure that the building of that economic activity is done in a way which does not damage the environment, and where the proceeds of it are perceived to be distributed in a fair way.

CURWOOD: Though Sir Mark Moody-Stuart believes in the power of enlightened self interest, thousands of environmental and social activists who have come to Johannesburg, don’t buy it, and don’t think the UN should, either.

[CHANTING PROTESTERS, HELICOPTERS,]

CURWOOD: The summit is supposed to be about the environment. Is it?

MAN: I don’t think so. It’s about, rather to forgetting about the environment. Because what we are promised in the back ten years in Rio, you know, forgot here. Completely. It’s about the sustainable capitalism not about sustainable development.

[HELICOPTER WITH PROTESTERS IN BACKGROUND]

CURWOOD: Thousands of police officers, many in riot gear, are lining the rutted streets of the poor black township of Alexandra. Their mission: crowd control of some twenty thousand demonstrators who are here in a protest march on the summit. This is the largest march in South Africa since the protests against apartheid.

[CHANTING PROTESTERS]

CURWOOD: How do you feel about the summit?

WOMAN: It’s a failure. They don’t take in consideration the real rights of the people.

CURWOOD: Hunter Lovins, tell me, why are you here today?

LOVINS: I’m here to petition my own government, my own government is not here in a, anything like a honest representation. When the heads of state are gathering to talk about the fate of the Earth, my president ought to be here and he’s not. And I am ashamed of that.

CURWOOD: How do you think this demonstration affects the official summit?

MAN 2: Well, I hope they get the message. I don’t know that they will, but there’s enough people here that they should really see what’s going on. But I’m not sure that they will be paying any attention.

[AFRICAN SINGING]

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: The World Summit on Sustainable Development is the largest gathering of world leaders ever in Africa. 190 nations are represented with more than 80 heads of government in attendance. Only two of the world’s top leaders aren’t here: America’s George W. Bush and Russia’s Vladimir Putin.

(APPLAUSE)

CURWOOD: As the plenary opens UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan sets the tone.

(Photo courtesy of BASD)

ANNAN: We look to the environment for the food and fuel and the medicines and materials that our societies depend on. We look at it as a rim of beauty and of spiritual sustenance. But let us not be deceived when looking at a clear blue sky into thinking that all is well. All is not well. All is not well.

SPEAKER AT PODIUM: I am pleased to announce today…

CURWOOD: Leader after leader from the world’s most affluent nations speak of partnership as they sketch out their plans and promises to meet the global challenge. France calls for a tax on multinational corporations. Japan offers training to help emerging economies avoid its own mistakes with pollution. Britain’s Prime Minister Tony Blair brings his checkbook.

BLAIR: I can tell you that Britain will raise by 2006 its commitment to development aid to Africa to 1 billion pounds a year and it’s overall levels of assistance to all countries by 50%. This is not charity. It is an investment in our collective future. If Africa is a scar on the conscience of our world, the world has a duty to heal it. We know the problems. We know the solutions. Let us, together, find the political will to deliver them. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Many leaders from the developing world remain doubtful that the good intentions and calls for partnership will translate into appropriate action. Bharrat Jagdeo is president of Guyana and chair of the Caribbean group.

JAGDEO: For partnership to work, it must be founded on trust. From my conversations with many of my colleagues, heads of government, it is clear that they feel that that trust does not exist. It is equally clear that this is due to the increasing prevalence of double standards in the conduct of international politics and economic affairs. It cannot be that partnership and interdependence are concepts to be invoked by some countries only when they feel themselves victimized and in need of international support. The type of partnership we seek between states must be based on the interest of all parties, mutual trust and respect.

CURWOOD: As the leaders are speaking, their ministers are putting the final touches on the Johannesburg Plan of Action. Much of the tension is over the balance between the demands world trade and the need to address environmental and human poverty. The agreement creates voluntary commitments regarding water, sanitation, agriculture, bio-diversity and health. The clauses on renewable energy are watered down at the insistence of the United States.

And perhaps the most important treaty spawned from the Rio process—the Kyoto climate change treaty –moves to center stage as Canada, China and Russia declare they will ratify the agreement. This will soon make Kyoto the law of the planet, except in the United States and Australia, unless they change their minds about the pact. It all makes for a chilly reception when it is time for U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell to speak:

(Photo courtesy of IISD/ENB-Leila Mead)

POWELL: The United States is taking action to meet environmental challenges, including global climate change. We are committed…. We are committed….

[SHOUTS FROM CROWD INTERRUPT POWELL, GAVELLING BY MODERATOR]

(Photo courtesy of IISD/ENB-Leila Mead)

POWELL: We are committed…. We are committed not just to rhetoric and to various goals. We are committed to a billion-dollar program to develop and deploy advance technologies to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. We have unveiled at this conference, four new signature partnerships in water, energy, agriculture and forests. These programs will expand access…

[RISING CHANTING FROM CROWD; GAVELLING FROM MODERATOR]

POWELL: …to clean water and affordable energy.

[AS CHANTING INCREASES, MODERATOR GAVELS AND TALKS OVER POWELL: "This behavior is totally unacceptable."]

POWELL: …provide jobs and improve food supplies for millions of people in need.

[CHEERING AND APPLAUSE FROM HALL]

CURWOOD: As summit security forces remove some of the demonstrators from the plenary hall, several environmental and social advocacy leaders, including Vandana Shiva of India, are staging a walk-out.

SHIVA: We’re leaving because the summit has betrayed the mandate of the summit, which was a follow-up of Rio. It has become a follow-up of WTO. This is not what these governments were sent here for. This is not what the public that sent them here is expecting. This was supposed to have been a sustainability summit. It has become a non-sustainability summit. Instead of representing the rights of the poorest to their vital resources – their land, their water, their biodiversity – the summit has ended up being an auction house for selling the resources of the earth to the highest bidder, which happens to giant multinational corporations.

CURWOOD: Many business leaders say they’re pleased with the outcome of the summit and the larger role at the UN for commerce, but most environmental activists say they gained little in Johannesburg. As the session ends, The UN Secretary General speaks to reporters.

ANNAN: I know there are those who are disappointed, and we didn’t get everything we expected to get here in Johannesburg. But I think we have achieved success, and I am satisfied with the results.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: We’re dedicating our entire program this week to issues raised at the Johannesburg Summit. We’ll be looking at efforts to bring fresh water to the poor of southern Africa. We’ll take a fresh look at nuclear power and its impact on climate change.

And up next we get an inside view on the environment from the White House. Stay with us. There’s more to come on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Arabesque, "Der Bauch", Gut Records]

Related links:

- Official Website Johannesburg Summit 2002

- International Institute for Sustainable Development

Almanac/Rio Summit

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg. Ten years ago, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro set much of the agenda for this meeting in South Africa. Reporter John Rudolph went to Rio and I’ve asked him to take us back to 1992 for this week’s Living on Earth Almanac.

RUDOLPH: The Earth Summit showed widening differences between industrialized countries and poor nations over how to solve environmental problems. It also featured the most intense security I’ve ever seen, with one security person on duty for every individual attending the conference, and heavy artillery aimed at the entrance to at least one of Rio’s infamous slum neighborhoods.

As the conference began in early June 1992, Mr. Bush still wouldn’t say if he was coming. Critics said he was trying to undermine the Earth Summit. The President did not support the proposed treaty on biodiversity, and his administration had worked to weaken the proposed climate change treaty designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In the end, President Bush did come to Rio to be part of the largest gathering of world leaders in history, and to defend his environmental record.

BUSH: America’s record on environmental protection is second to none. So I did not come here to apologize. We come to press on with deliberate purpose and forceful action. And such action will demonstrate our continuing commitment to leadership and to international cooperation on the environment.

RUDOLPH: The Earth Summit produced Agenda 21, a broad action plan to promote sustainable development--that is economic development that conserves resources for future generations. The conference also yielded two treaties, one on climate change, which Mr. Bush signed while in Rio, and one on biodiversity, which he continued to oppose.

At the Earth Summit, Mr. Bush’s speech was widely criticized for lacking new ideas and new financial commitments to developing nations. But ten years later that speech is now considered by some environmental activists to have been a call for forceful action. Just before the Johannesburg meeting began this year, the Natural Resources Defense Council issued a press release praising the 1992 speech and calling on President George W. Bush to fulfill his father’s promises at Rio.

That’s this week's Living On Earth Almanac, I’m John Rudolph.

White House P.O.V.

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa.

One of the top coordinators of U.S. policy in the negotiations here has been the Chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality, James Connaughton, and he joins me now. Hello, sir.

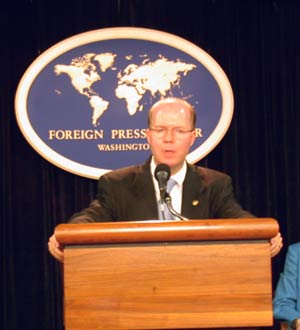

James Connaughton at an 8/21 press briefing on the World Summit for Sustainable Development. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Department of State.)

CONNAUGHTON: Hello. Good to see you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how has this gathering been different from the Earth Summit in Rio?

CONNAUGHTON: The Earth Summit in Rio was largely an effort to set the agenda for sustainable development and put sustainable development on the map. As we move forward, we’ve been working and focusing on implementation. And that’s really been the question all along: How much implementation of that agenda are we seeing? What distinguishes the World Summit then is it is focused on poverty eradication as a theme. And we are looking at poverty eradication in specific subject areas: water, energy, health, agriculture, and even biodiversities, creating good environments for communities to grow.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what were the U.S. objectives here in Johannesburg?

CONNAUGHTON: It was our view all along that this summit should be dedicated to not just having governments internationally getting together, but bringing civil society in the private sector forward, along with environmental groups, consumer groups, citizen representation, to, again, talk about concrete actions related to the agenda that we’ve set for ourselves.

CURWOOD: Why didn’t President Bush come? His dad went to Rio ten years ago.

CONNAUGHTON: The president worked hard with the other world leaders earlier this year and they came together this year in Monterrey, Mexico. And there they announced the new Compact for Development. Having announced that compact with the world leaders, the president then personally carried that message to the G8. When it comes then further to the president’s further personal commitment, he has already announced he will be coming to Africa early next year. And I think there, at that point, he will put his own personal mark on our commitment to development in this part of the world.

We look to this summit, as we did to the Food Summit earlier this year, as a key implementation summit. We have representatives from almost every department of the U.S. government, the President’s top leaders, responsible for implementing the actions that we need to see.

CURWOOD: And what were the most important concrete actions here?

CONNAUGHTON: We announced a major initiative with respect to providing water for the poor. It was a $970 million dollar initiative that will leverage non-governmental resources up to $1.6 billion dollars to deal with what everybody recognizes as the fundamental issue with respect to poverty, and that’s lack of access to clean, safe water.

CURWOOD: Here in Johannesburg, the U.S. opposed any specific goals for renewable energy. Why was the U.S. so concerned about not having specific goals?

CONNAUGHTON: First of all, our commitment from the outside couldn’t be stronger to the advancement and promotion of renewable energy technologies. And our spending both at the national level and the international level in promoting those is unsurpassed in the world. Our objection to putting in a specific date and a specific target is the fact that we have not sat down, either at the international level or even at the regional level, to identify the plan by which that would be achieved. We are trying to reset the international conversation to sitting down and creating the plan, coming up with the target, and then holding ourselves to it. You create that kind of energy, we can get the market forces to bring those prices those prices down. The prices come down, you’re going to get a lot more renewable energy, and that will accomplish much more than any stated target in the document.

CURWOOD: James Connaughton is Head of the White House Council on Environmental Quality. Jim, thanks for taking this time with us today.

CONNAUGHTON: Thank you.

Small Scale Nuke

CURWOOD: Whatever the future mix may be for renewable energy, engineers in South Africa are developing an ambitious plan to expand the role of nuclear power. They’re hoping to build small scale nuclear plants throughout the world, leading to what some are calling a nuclear renaissance. Living on Earth’s Terry Fitzpatrick has been taking a closer look.

(WAVES HITTING SHORE)

FITZPATRICK: There’s a heavy surf outside Cape Town, and a rainbow in the cloudy sky. Along the storm swept beaches of Africa’s southern tip you’ll find some of the world’s most rugged coastal beauty.

(HUMMING OF KOEBERG ELECTRIC STATION)

FITZPATRICK: You’ll also find the only nuclear power plant on the African continent. The Koeberg Electric Station, two concrete containment buildings, with atomic twins inside.

DE VILLIERS: We take in water at the rate of 80 tons per second. It will fill up an Olympic size swimming pool in, literally, 30 seconds. Poof, you’ll have all your water in there (chuckles)…

FITZPATRICK: Karen D e Villiers is the spokeswoman for Eskom, the government-owned company that built the Koeberg plant 18 years ago. She’s guiding reporters on a hard hat tour.

[SOUND OF PUMPS]

FITZPATRICK: Past the powerful pumps that suck in ocean water to cool the reactors.

[POUNDING OF TURBINES]

FITZPATRICK:Past the giant turbines that use the heat of an atomic chain reaction to generate electricity.

[MORE PLANT SOUND]

FITZPATRICK: Koeberg looks like a typical, large scale nuclear plant in the United States. But Eskom is hoping to pioneer a new type of atomic facility here. The new reactor will be radically different. It’s much smaller, generating just a tenth of the power of a traditional plant. It uses helium instead of water to cool the atomic core.

DE VILLIERS: Helium is a very nice gas. It’s what they call an inert gas. It doesn’t pick up any of the radioactivity. So it goes in clean, it comes out clean. So if you have a leak, it’s not a problem.

FITZPATRICK: Another pebble-bed innovation is a new type of nuclear fuel. Instead of traditional fuel rods with exposed uranium, the new plant will use uranium pebbles the size of tennis balls. Each pebble is coated with protective layers of graphite and silicon carbide. Ms. De Villiers says this coating will prevent the fuel from overheating. She says a nuclear meltdown is physically impossible.

DE VILLIERS: And that is why we talk about it being inherently safe. If you had to lose all the helium which cools down that reactor, you had a break on the part, the guards could actually walk away from the reactor, leave it for two days, it would grow a little bit hotter. But we could come back three days later, clean it up, it would be a hell of a mess in the station, but it would not affect you or me or anybody off the site.

FITZPATRICK: Conventional nuclear plants need emergency cooling systems and containment buildings to isolate the reactor from the environment. But engineers say the newer, smaller design--known as a pebble-bed--won’t need the same level of protection. And that’s part of what makes them attractive. With less of a need for expensive safety equipment, pebble-bed plants can be built in just two years at a fraction of the cost of a conventional nuclear station.

KADAK: It will, in fact, revolutionize, I think, the way we produce electricity.

FITZPATRICK: Nuclear engineer Andrew Kadak has been working on pebble-bed designs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

KADAK: People are desperately looking for emission-free energy sources. And as energy demand will grow, as developing nations such as China, seeks to expand its per capita electricity consumption, India, the entire continent of Africa, people are going to need a way to produce electricity that doesn’t pollute our planet. And nuclear can do that.

FITZPATRICK: South Africa is a case in point. It’s anticipating an acute energy shortfall beginning in 2006. Right now, the country depends on coal for 90 percent of its electricity. Eskom is developing wind and solar sources, but the company wants to increase its nuclear capacity to help close the gap. Ultimately, Eskom and its partners hope to sell hundreds of pebble-bed plants worldwide. The problem is convincing the public that many reactors are safer than the old style plants made infamous by the accidents at Chernobyl and Three Mile Island. Again, Andrew Kadak.

KADAK: We shouldn’t judge the future by the past. We’ve learned a great deal about how nuclear power plants work. And all these lessons are being applied to these advanced designs to make them more technologically solid. So, yes, we are at a crossroads. And if we can make these plants economic and competitive to natural gas or other sources, they will, in fact, be deployed worldwide.

(FOOTSTEPS)

FITZPATRICK: Not everyone believes the assurances of the nuclear industry, least of all, some of the people who live near Eskom’s existing facility.

C. MENTOR: If you look over here, here’s the plant, that’s Koeberg plant.

FITZPATRICK: Clarence and Julie Mentor live a couple of miles from the site where the new reactor may be built. They’re leaders of the local development forum in the township of Atlantis. Clarence Mentor is worried about the radioactive wastes that the pebble-bed will generate, which will be kept on site. He’s also concerned about the integrity of the reactor building.

C. MENTOR: As we’ve seen during the attack on the World Trade Center, a plane can penetrate a building. So, if there’s no containment building, it’s going to be very worrying to us.

FITZPATRICK: Julie Mentor thinks her community is being used as a guinea pig for unproven technology.

J. MENTOR: Atlantis is so small, and we do not have the resources to really cope with any emergency, especially as serious as with nuclear. I can’t imagine 100,000 poor people who don’t have cars, how they will ever be removed from an area.

FITZPATRICK: Scientists in Germany and the U.S. have been experimenting with pebble-bed research reactors for decades. They say, all but one ran smoothly, and the trouble at that plant involved an oversized reactor and mechanical design flaws, mistakes they promise not to repeat in South Africa.

Still, the safety questions persist. Professor Kadak at MIT thinks the only way to settle the debate is to build a full scale pebble-bed plant and try to melt it down to prove it can’t be done. He’s asking Congress for half a billion dollars to run the experiment at a government facility in Idaho.

KADAK: I’ve called our approach the politically correct reactor, which is some people smile about. But what we want to do is demonstrate the safety. Not just tell people about the safety, but demonstrate it actually by conducting such a test of losing all coolant and watching nothing happen.

[WAVES ON BEACH]

FITZPATRICK; Back on the beach beside the Koeberg plant, Charlene van de Merwe is walking with her dogs and son. They come every day when the migratory whales are here.

VAN DE MERWE: We saw 13 whales out here the other day.

FIZTPATRICK; What kind?

VAN DE MERWE: The Southern Right Whales.

FITZPATRICK: Ms. Van de Merwe lives about a mile from where the South African pebble- bed project might be built. She is ambivalent about it.

VAN DE MERWE: On the one hand, this Koeberg is a good idea because it provides power to people that wouldn’t normally get. And if they make more, more people would have electricity and not freeze to death in all this rain.

FITZPATRICK: But Ms. Van de Mewre wonders if the risk is worth it. She looks out at the ocean, and then at the Koeberg plant.

VAN DE MERWE: It’s scary, I think, because we will be incinerated if anything goes wrong here, especially if it’s an experiment thing. There’s a lot of people that live here.

FITZPATRICK: The South African government is expected to decide by the end of the year if the Koeberg pebble bed reactor may be built.

For Living On Earth, I’m Terry FitzPatrick in Cape Town.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

Solar Salon

SHAYS: My wife told me I needed a haircut, and I understand that all of this is powered by solar?

MINOR: Yes.

SHAYS: The clippers is solar powered?

MINOR: Yes.

CURWOOD: Congressman Christopher Shays, Republican from Connecticut. You’re going to get a haircut here?

SHAYS: I’m going to get a haircut, and it’s powered by solar energy. I know I have a good barber. My only concern is that I’m going to have a hard time getting here to get a second one.

[SOUND OF CLIPPERS]

CURWOOD: Some people might say this is a metaphor for what’s going on in the world energy-wise, your haircut and what the world is facing.

SHAYS: You mean, because I’m losing a lot of my hair, is that what you mean? [LAUGHTER] You mean my head is threatened and so is the world, is that what you mean?

CURWOOD: What I mean is that some people think that we should trim our use of energy and certain forms of energy.

SHAYS: Well, clearly, we need to do a much better job. We need economic development. But we have a threat. Global warming is for real. Climate change is for real. It doesn’t sound very loud, but it’s able to cut my hair off, huh?

MINOR: Yes.

CURWOOD: How well do the clippers work here using solar power?

MINOR: They have enough energy to go on for the whole day.

CURWOOD: And what’s your name?

MINOR: My name is David Minor.

CURWOOD: And we’re in your barbershop, which is actually this big yellow shipping container. And next door there’s a juice bar, and there’s, what, an electronics repair show, and a business center where there are a bunch of computers.

MINOR: Yes.

CURWOOD: How do you feel using solar power?

MINOR: It makes me feel great because it is part of environmental safety.

SHAYS: I just got to tell you, my head isn’t round, so if you press too tight, you’re not going to have a good haircut here.

CURWOOD; You sit in the Congress. What kind of things can you do in Congress to be responsive to the calls here at the World Summit?

SHAYS: All the financing that the major developed countries are doing for the undeveloped countries, ten percent, at least, should go for energy that is sustainable. When we help a third world country invest in a fossil field plant, we’re stuck with that plant, they’re stuck with that plant for the next 50 years. And yet, they could start fresh. They don’t have to make all the mistakes that were made in the United States.

Uh…I’m getting a little concerned. You’re laughing. Are you laughing at my haircut?

(LAUGHTER)

CURWOOD: Well, you know, there was a guy, what was his name? Kojak?

[LAUGHTER]

SHAYS: You know, this is a tough interview, because while you’re asking me important questions about the future of the world, I’m wondering what I’m going to look like when I show myself to my wife.

CURWOOD: Christopher Shays is a Republican Congressman from Connecticut. Thanks for taking this time with us.

SHAYS: Thank you for taking the time with me and for laughing as I get my haircut.

[BUZZING OF HAIRCLIPPERS]

Health Note/Save the Children

CURWOOD: When water and corporations mix. Private business and the public water supply in South Africa is next on Living On Earth, after this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[THEME MUSIC]

TOOMEY: The U.N.’s World Health Organization announced a new Children’s Health Initiative at the Sustainable Development Summit in Johannesburg. Speaking at the summit, the WHO’s General Director Gro Harlem Brundtland told delegates that environmental hazards kill the equivalent of a jumbo jet full of children every 45 minutes. Preventing these deaths, she said, should become one of the highest social and political priorities of this decade.

Children are at risk from such things as poor sanitation, indoor air pollution from cooking stoves, and neurological damage from improperly applied pesticides. For instance, in places that can’t afford modern sewage systems, human wastes often pollutes ground and river water where children live and play. That situation contributes to the grim statistic of one child death every eight seconds from a water-related disease.

Children are at particular risk from environmental dangers because in relation to body weight, they breathe more air and consume more food and water than adults. The WHO is promoting such low-tech solutions as solar-powered water disinfection units, and insecticide treated mosquito netting to prevent malaria.

The WHO hopes to enlist partners in this effort from corporate, government and non-governmental organizations, as well as from local communities worldwide.

That’s this weeks Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Primal Scream, "Trainspotting", Reprise Records]

South Africa Water

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg.

There’s nothing more basic to life than water. Yet about a billion people have to, somehow, get by with dirty drinking water. The world’s leaders here at this Summit pledge to cut that number in half by the year 2015. South Africa is already on the way. The end of apartheid brought more water taps to the desperately poor, but it came at a price, literally. A market-based model for water delivery has proved to be less workable than the government would have liked. Bob Carty has our story.

[WATER RUNNING AND PEOPLE TALKING]

CARTY: A group of women and young girls are filling up plastic containers with water. The water flows from a brand new stand pipe sticking out of the ground in the Province of KwaZulu-Natal. One pre-teen girl here balances a 55 pound bucket on her head. Another girl struggles with a wheelbarrow filled with three of those jugs. It’s probably twice her own weight. The two of them head up the hill toward home.

This is how many South Africans get their water everyday, many times a day. But they have water due to the effort of the South African government.

VIDEO: (over music) To date, the program has delivered water services to seven million people in seven years. South Africa’s success will make the country a valuable contributor to the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development. (fades under)

MULLER: One beats one’s own drum but in rural areas, many places people do say we do actually now have water.

CARTY: Mike Muller directs the national Department of Water. When his government came to power in 1994, one-third of all South Africans lacked clean drinking water. Mike Muller’s department cut that number in half. And that became one of the country’s bragging points at the summit.

MULLER: We think the rate of delivery is pretty good. And if you compare it to the Millenium development goals to which all our heads of state have committed, which is to half the proportion without safe water by the year 2015. So they made that resolution in 2000. So in 15 years to halve it, we’ve halved it in seven years. So we’re going pretty well.

CARTY: But it’s not going so well for many South Africans. And you see it driving around the township on the outskirts of Cape Town following two small trucks from the municipal government.

(DRIVING IN CAR)

DAVIS: These are the people that come in and cut the water off of the people. They’re going to lose their water now, and they don’t know what to do. What are they going to do without the water?

CARTY: My traveling companion is Cecelia Davis, a resident of this township. The trucks up ahead suddenly stop in front of a small house.

(CAR DOOR OPENING AND CLOSING)

CARTY: Two armed security guards get out of one truck, six men jump out of the other with wrenches and hammers.

[CLANKING OF OF TOOLS]

CARTY: The workers lift up a water covering on the street and starting shutting off the meter going into the home.

(WRENCHES TWISTING)

CARTY: He’s turning off the water now, right?

DAVIS: Yes, he’s turning it off now.

CARTY: In 15 minutes the job is done. The residents of this household are now like thousands of others in this township who are fortunate enough to have water pipes in their homes, but no running water. One of them is Cecelia Davis herself. Cecelia is a single mother with four children still at home. And home is a dark, cold, three-room cement shelter, with no water.

[FAUCET CREAKING]

DAVIS: I’m opening the tap, but there’s no water coming out. No water, not even a little bit now. No water. Because the water has been cut off the meter has been removed. That was last October.

CARTY: Last October?

DAVIS: Last year, October.

CARTY: Almost a year?

DAVIS: Almost a year.

CARTY: So how do you get water?

DAVIS: I get water from an opposite neighbor, with the pots.

CARTY: For Cecelia Davis, life now revolves around fetching water in pots from the neighbors, one pot for cooking, one to flush the toilet, ten to do the washing. Cecelia Davis has no income, just the support of neighbors and family, and that’s not uncommon here in the townships where 60 percent are unemployed. Over the years the city raised Cecelia’s monthly water bill by 300%. She couldn’t pay it. And even though she had two sick children in the house, the city cut her water off. It wasn’t what she expected from the post-apartheid governments of Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki.

DAVIS: Before the new government, they weren’t doing these things. I’m very, very, very disappointed in the government of South Africa really.

CARTY: And Cecelia Davis is not alone, according to Professor David McDonald.

MCDONALD: Our estimate, based on a large national survey that we did in 2001, is that as many as ten million people have had their water cut off since 1994. Now, some of that has been very short term, but some of this has been for months and months on end. People are very, very angry.

CARTY: David McDonald is a Canadian who has been working in South Africa studying municipal services. McDonald says that when the African National Congress came to power, they privatized water services. Most water boards were still publicly owned, but they had to run like a business. So they implemented full cost recovery, charging people for water, regardless of their ability to pay.

The goal was to discourage people from wasting water and to collect money for reinvestment in more water pipes for more people. Some see this as a good form of sustainable development. David McDonald does not. He argues that with pressure from the World Bank, cost recovery here became an inflexible ideology.

MCDONALD: And that’s okay at the top end for people who can afford it. So someone might think twice about filling their swimming pool or washing their car yet again. But at the bottom end where people are extremely poor, people are saying things to us like, "I have to choose between water and food." So it’s a question of at what point do you start cost recovery? This notion that you’re saving money is really a false notion because of the hidden cost of privatization.

(WATER FLOWING)

CARTY: Those hidden costs are apparent here, back at the water pipe at KwaZulu-Natal. Two years ago, the municipality installed meters on the public taps. You could only get water if you paid in advance for a computerized card to insert in the meter. Getting water became like going to a gas station. People found they couldn’t afford the water they needed, and they smashed the pre-paid meters. So, the local authorities put locks on the pipes. And then, according to David Hemson of the Human Science Research Council of South Africa, a disaster happened.

HEMSON: It forced people to go back to the original sources of water, to rivers and to polluted streams and the like. And that was a direct cause of the cholera epidemic. There’s no doubt about that. We’re looking at about 350,000 people who were affected, just below 300 people dying from cholera. There were emergency hospitals set up. Tents were set up for rehydration purposes. The cost has been tremendous. And just imagine if all of that money is being spent on providing services in the first place?

[CHANTING AT DEMONSTRATION]

CARTY: Water cut-offs have generated protests across the country. Here at the largest demonstration outside the Summit in Johannesburg, there are placards reading, "Our water is not for sale." Many in the crowd are wearing T-shirts against privatization. They believe cost recovery will lead to the takeover of water by foreign corporations.

In part because of these protests, and in part because of the cholera epidemic, the South African government has now changed its water policy. There is still cost recovery, but there is also a pledge to provide at least six gallons per person, per day, free of charge. But many of the poor say they have yet to see it.

There continues to be a debate here about the balance between the market and the state in delivering something so essential as water. Privately, government officials admit they went a bit too far in making the liquid of life a commercial commodity.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bob Carty.

[PEOPLE CHANTING]

Corporate Accountability

CURWOOD: We’re here at the Ubuntu Village which I’m told is the world’s largest tent. It’s been something of a crossroads during this summit, where delegates and activists from civil society have been strolling among the various displays. Many governments have elaborate presentations here. Germany, Malaysia, Japan, Sweden, Brazil. So do many corporations, Chevron, British Petroleum, and others.

Marcello Furtado joins us now. He heads up the Greenpeace Campaign for Corporate Accountability. Hello, sir.

FURTADO: Hi, how are you?

CURWOOD: I would like us to look forward from the Johannesburg Summit, if we could, to what comes next. There’s a lot of talk, and frankly, a lot of commitments from corporations at this summit to help promote environmental protection. But your group lobbied for and got in the text of the agreement coming out of this, some language about corporate accountability. Can you tell me about that?

FURTADO: Sure. We actually work with a lot of other NGO’s and other groups from civil society, human rights groups, community groups. And what we got here was a great precedent for this international treaty because it moves corporations from the voluntary initiatives into something that will be eventually legally binding. In fact, the language basically says, "to actively promote corporate responsibility and accountability based on the real principles, which means human rights, precautionary principle, and including through the full development an effective implementation of intergovernmental agreements and measures. That’s very important, because that’s our ticket for an international treaty.

CURWOOD: Why is an international treaty necessary if corporations have made very public pledges here and elsewhere on a whole wide range of issues, and environmental groups like yours, I imagine, are closely monitoring them. Why have a formal treaty?

FURTADO: Well, first of all, because it’s not our job to monitor a corporation. It’s the government’s job to do that. The reason why we’ve been going around and taking samples of what’s going on is simply to make the case that voluntary agreements are not enough. Corporations that have standards, that have made their pledge for the environment and for people, are using double standards and contaminating communities and water in our environment. And worse than that, they talk a lot, but they do very little. So we want to move them beyond the voluntary, to regulations, where then they have to be accountable.

CURWOOD: What would you like to see in a convention on corporate accountability?

FURTADO: Well, I think we have a wide range of views and elements we can put in. But, for example, we would have right to know. We would have human rights. We would have the possibility of seeking compensation, to seek liability, all at the international level. Because we have now corporations operating in every country they want in the planet at the international level. But people, when they suffer a consequence, when they are contaminated, they don’t have an international forum to go for compensation.

CURWOOD: How would such a treaty be enforced? Would there be some sort of a world court or corporate court or something like that?

FURTADO: Well, we still have to discuss that. I think we have a lot of institutions in place that could handle this. But if not, we should create one. The bottom line is that I’m sure that for our sake and for the corporations, and for governments, they would all want a very transparent process that works.

CURWOOD: We’ve heard a lot of expressions of frustration, and a number of environmental groups walked out at various times in these proceedings. But how would you rate the actual outcome of this summit?

FURTADO: Well, we think the summit was a failure, but we have little crumbs of hope. And I think the best one that we have is the corporate accountability decision.

CURWOOD: Thanks for joining us.

FURTADO: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: Marcello Furtado of Greenpeace.

Voice of the People

(PEOPLE MILLING IN BACKGROUND)

CURWOOD: Let’s see what the message is that other folks here at Ubuntu Village is going to take home with them from this World Summit on Sustainable Development.

Excuse me, can I ask where you’re from?

WOMAN 1: I’m from Oxford.

CURWOOD: What’s the message you’re going to take home from this summit?

WOMAN 1: The message I’m going to take home from here is that we are not alone in the world anymore. But we have to contribute and participate in respect of elevating our own standards of development.

[SOUND OF DRUMS]

CURWOOD: Can I ask where you’re from?

MAN 1: Honduras. We’ve got to do it ourselves, with a little help from our friends, like Colin Powell.

MAN 2: Back in my community in Des Moines, Iowa., I’m taking a strong concern for the position of the United States. Very concerned about their attempt to move the agenda from sustainability to trade, in line with the WTO.

MAN 3: My major concern is fresh water. Water and sanitation are the human rights.

CURWOOD: Can I ask where you’re from?

WOMAN 2: The United States. The message is, ultimately, it is the individual who has got to have their voice heard and who has got to make a commitment to something that is sustainable in their behavior, attitude and way of living in this world. Because the governments are not going to do it for them.

MAN 4: Basically, what we need now is to go for implementation so we will not see the same as after Rio where there was a lot of high flying ideas and too little implementation.

MAN 5: Well, I accomplished a great deal by meeting a lot of new people and making a lot of friends and business contacts, and a stack full of business cards. So that’s been my main accomplishment.

WOMAN 3: I’m originally from England, but more recently I’m in Geneva in Switzerland. I think I felt that bringing together all the people from the world has brought a lot of hope in spite of a lot of the negative messages, and that there really is something that each one can do. But a lot of it really depends on attitudes. So it’s really a matter of looking inside and really knowing what I want for myself, and then what I want for the world.

CURWOOD: Thank you very much.

WOMAN 3: Thank you.

[SOUND OF DRUMS]

CURWOOD: Over here is, this has got to be the biggest drum I’ve ever seen. It’s made out of baobab wood, and it’s here, smack in the middle of Ubuntu Village, in a replication of a tropical rainforest. And right in the middle of the pavilion is a tree. It’s called the Dream Tree. And school children from all over South Africa were asked to write out leaves that have their dreams.

Here’s one that comes from Robin Hills. "My dream is that we should plant more trees and cut less down."

Here’s another one that says, "My dream is that everyone in South Africa, you and me and everybody, would be joyful and content in their lives.

This is from Matthew, at Trinity House Preparatory School. He says, "My dream is that all war will stop, that we can accept other people, that people will stop killing animals, that there will be no poor people, no more pollution, and that we can take care of the environment."

(DRUMMING)

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living On Earth. Next week, Northwestern Montana is home to the Yaak Valley, where the landscapes of the Pacific Northwest and the Rocky Mountains meet. It’s a wilderness to which people escape, but where visitors have a limited welcome.

PARVIN: We spent the longest day of the year in this lovely place. It has worked its spell, our long, dark winter seeming far behind us now. But the tight circle of hours we’ve been here, maybe even that small amount is too much for this tired valley.

CURWOOD: Life in the Yaak, next time on Living on Earth. But before we go, we leave you with the sounds of the baobab drum right here at Ubuntu Village.

[SOUND OF DRUMS AND SINGING]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by The World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber, Maggie Villiger, Jennifer Chu, and Al Avery, along with Julie O'Neill, Susan Shepherd and Carly Ferguson. Special thanks to Ernie Silver, and to Terry FitzPatrick who made our Johannesburg program possible.

We had help this week from WNYC New York, and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Allison Dean composed our themes.

Our Technical Director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our Western Bureau. Diane Toomey is our Science Editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our Senior Editor. And Chris Ballman is the Senior Producer of Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood, Executive Producer. Thanks for listening, and "sala kahle" from South Africa.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from The World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include: The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of Western issues, The National Science Foundation, supporting environmental education, The Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth's expanded internet service, The Educational Foundation of America for coverage of energy and climate change, The Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation for reporting on marine issues, The W. Alton Jones Foundation, supporting efforts to sustain human well-being through biological diversity, www.wajones.org, The Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of marine issues, and The Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth