Tar fields along the Athabasca River in Alberta, Canada. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004) Tar fields along the Athabasca River in Alberta, Canada. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

CURWOOD: Let’s talk a bit about oil recovery technologies. Now, you grew up in the oil fields there of east Texas. They used to just, what, put a drill in the ground and go, right?

ALLEN: That’s exactly it. And then some things came on called “secondary recovery,” at which you could inject either water or gas into the ground and drive that oil out of the oil shale, or the oil sands, up into the pipes for recovery. And that has really increased greatly the recovery and the amount of oil you can recover from each field. And now the Russians have begun using this kind of technique in their areas, and it has really increased their production quite dramatically. As a matter of fact, they just surpassed Saudi Arabia as the world’s largest oil producer. And that’s primarily because of the secondary techniques. They’re now beginning to drill for oil and to recover oil in the same way that the United States has been doing for a long time.

CURWOOD: So, what’s the true cost, then, of these emerging oil technologies in terms of, well, the environment, as well as the political and social impacts?

Tar oozes from sand along the Athabasca River. Formed millions of years ago as oil leaked from reservoirs, the tar, or bitumen, permeates more than 15,000 square miles. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004) Tar oozes from sand along the Athabasca River. Formed millions of years ago as oil leaked from reservoirs, the tar, or bitumen, permeates more than 15,000 square miles. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

ALLEN: Well Steve there are things that are really the hidden costs of oil. And using gasoline, for example, some are even more subtle than others. If you adjus the cost of the oil itself, about 50 percent of the cost of a gallon of gasoline in this country comes from the crude oil cost itself. But then you have other costs, such as refining, and distribution, and the profit to the oil companies, etc. And then you have taxes. Now, in this country we pay probably less tax than almost anyone else in the world on oil. If you look at Germany or England or some of the other European countries, you end up with $3 or $4 per gallon in taxes.

But there are other hidden costs, such as the cost of sitting in traffic and burning fuel that is not being used to push someone somewhere, but is just being burned while you’re sitting at stoplights or in gridlock someplace. And the cost of accidents. But there’s an even more hidden cost than that, and it’s one that’s almost impossible to measure: what is the cost of securing oil fields around the world? This is in terms of military presence, of security presences, around the world, whether it’s in the oil fields themselves or in the shipping lanes to protect that.

Right now there’s a big worry in the Malacca Straits around Indonesia as to what’s going to happen if Al-Qaeda should suddenly launch an attack there. You have a very narrow choke point about a mile across. If a big tanker or something is sunk there, then you’re going to have to have a bit of a diversion in an additional thousand miles in your trip to get oil especially to Japan, for example. So these are all really, really hidden costs and there’s almost no way to put a cost, a price on that.

CURWOOD: Let’s make a try at looking at these hidden costs. What do you estimate it costs us in terms of, say accidents?

ALLEN: I would guess probably about $1 a gallon to sit there and burn oil while you’re sitting in a traffic jam, and about another 80 cents for traffic accidents and stuff. So by the time you add all of these things together you’re looking at a price somewhat over $4 a gallon, is the actual cost of the oil that you’re burning in your car now.

CURWOOD: What kind of stab could you make at the defense costs? I mean, what’s sort of the minimum amount that we could attribute to our military presences required to maintain oil security at this point?

ALLEN: That’s an even more difficult number to come up with. It would just be a wild guess for anyone to come up with what percentage of our military budget is devoted to that. But I would think it has to be at least another dollar or $2 per gallon.

CURWOOD: So at the end of the day, oil, gasoline for cars, is costing everybody about $6 a gallon?

ALLEN: That would probably be about right, six, maybe even $7 a gallon, Steve.

CURWOOD: We don’t pay that at the pump, of course, because it comes from things like the defense budget, or people’s health insurance for taking care of accidents, or companies really losing their productivity of employees stuck in traffic.

ALLEN: That’s exactly it. And that’s why those are such hidden costs, and why it’s so hard to narrow those things down. But they are indeed real costs of oil.

CURWOOD: So, Bill, how do you get that number into the public discussion about the way we use energy, the way we use oil?

ALLEN: Well, Steve, I think one of the best ways is to do exactly what you’re doing right now. Get it out there and make people know what the true cost is. And then maybe they will be able to figure out that, hey, this is an extraordinarily valuable commodity. Maybe we should concentrate a little bit more on that one-third of our oil supply that is not being burned but is used to produce fertilizers, for pesticides, for plastics for your soccer balls and bike helmets, cell phones. That kind of thing may be an even better use for the oil that we have now.

CURWOOD: I want to ask you more about that, but we need to take a break right now. My guest is Bill Allen, editor-in-chief of National Geographic magazine. In just a minute we’ll continue our discussion with Bill Allen, and then talk with the chief economist from the American Petroleum Institute. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. If you’re just tuning in, my guest is Bill Allen, editor-in-chief of the National Geographic magazine. This month’s cover story is called “The End of Cheap Oil.”

Bill, before the break, you were telling us how oil is used for more than just gassing up our cars. While two-thirds of it is used for transportation here in the U.S., you said the remaining third goes for a wide variety of other purposes. Now what are some of these other uses of oil?

ALLEN: Well, let’s see, if you have some kind of carpeting in your home, that’s probably, unless it’s cotton or wool, is probably going to be derived from oil products. Almost anything that’s plastic, a lot of parts of televisions, cell phones, a lot of these things are derived from oil. It takes about three-quarters of a gallon of gasoline to produce a pound of steak. It takes about seven gallons of oil to produce a tire. So there’s a lot of things that we don’t really think about that are directly related to the rest our lives.

We have a lot of things that are produced, and as a matter of fact, some people have said perhaps it is that oil is too valuable to burn. It’s much more useful for all of these other, for the entire plastics industry, for all of this. The cost of our food, for example. The reason that corn costs, is relatively inexpensive, is probably because of relatively inexpensive oil.

CURWOOD: Oil that’s used as fertilizer.

ALLEN: Oil that’s used as fertilizer. That’s another huge use in our agricultural area that people don’t really think about. Pesticides, those are also derived. If we didn’t have pesticides or fertilizers derived from oil products, our cost of food would increase dramatically and would have a direct effect on all of us. I presume that everybody likes to eat.

CURWOOD: (laughs) guilty as charged. If oil gets more expensive, it would seem that alternatives would swing into place, that that very high price would change people’s behavior like in the old embargo, say from the 70s, people started building and buying much smaller cars.

ALLEN: Steve, you’re right. We have seen that actually happen, back in 1983, we saw about a 15 percent drop in US domestic oil consumption when the oil prices did go up to about $70 a barrel, and we saw people demand more fuel-efficient cars. So that kind of thing in all probability would happen. Also you see the same kind of thing from taxes. In Germany for example, where a lot of the cost is maybe $3-$4 in that range of the cost of a gallon of oil, gallon of gasoline rather, is by taxes.

You do see a demand for more fuel-efficient cars. So that kind of thing could delay the time at which we have to switch to an alternative. And it takes a lot time, Steve, to find these new technologies that are going to replace oil. We’re talking 20,30,40, some even say 50 years to find new technologies that would be able to replace oil. And every day that we can buy by conserving gives us a little bit more time to develop those technologies.

CURWOOD: What do you think the world is going to look like when this oil crunch comes?

ALLEN: Well I think there’s going to be a lot of shock. You know, in this country especially, we’re not very good at planning ahead many times. We sort of wait for other people to force the action, and then we react. Americans have a great way of reacting very quickly to problems, but we don’t have the same kind of great track record for anticipating problems. So I would think that as the time gets closer and the oil prices begin to creep up, there’s going to be a slow realization that we really do have to conserve. And we have to find other ways to use more fuel-efficient cars, for example, since we do use about two-thirds of this for our fuel.

CURWOOD: So Bill, what’s being done then to guard against the day when oil is no longer cheap? I mean, what changes should we be making that we’re not right now?

ALLEN: Well, one of the things we really can do that’s almost pain-free, is to demand and look for more fuel-efficient cars. This is the kind of thing that doesn’t really take a lot of sacrifice on everyone’s part, and you can continue using those cars. That’s probably the biggest single thing we can do. Obviously conserving energy in all forms is going to be another way.

CURWOOD: Now one question about burning oil: With all the concern about climate change, how long do you think we’ll be able to keep burning oil the way we’ve been burning it?

ALLEN: Well, there’s no indication that there’s a great deal of incentive to stop burning it. So I think we’ll probably continue to burn it until the price gets too expensive. And that’s when we’re talking about cheap oil. As long as it is so cheap that we can almost use it as a disposable commodity, we will probably continue to use it as a disposable commodity.

CURWOOD: How do you get people to change their approach to this, the political system to change its approach to this?

ALLEN: Well, it’s very difficult, you know, it’s going to be political suicide for anyone to say, you know what we really need in this country is about $3 a gallon tax. I can’t even imagine a President supporting that, or the majority of the House or Senate, or the Senate doing anything like that. So it’s going to be very difficult to attack it from that point of view. And what’s going to happen, as these prices go up, and as we see what the effect is of this increased oil price, we’re going to give away to other countries and to other petroleum suppliers the ability that we have to control our own destiny.

We could control by finding some way to encourage further conservation in this country and more gas mileage in cars, for example, but it’s going to be very difficult to do. It’s going to take a lot of political will, and it’s going to take a lot of explaining by a lot of politicians, and it’s going to take a lot of courage by politicians to say, you know, we have a serious problem that we’re going to be facing here. And until we can develop new technologies for this, we have to make sure that we’re going to have the oil to get us through that bridge time. It may be that there has to be some other drastic, drastic step that is taken, but what’s going to happen is that drastic step is probably going to have to be taken outside of our political system. Because we might react very well to that, but I don’t think we’re going to be pro-active.

CURWOOD: You say it would take drastic action. What do you mean by that?

ALLEN: If there is another bump in oil prices, if there is a huge political change in some country that has control over a significant part of the supply in the world, and you see oil suddenly double or triple in price, that’s drastic action. At that point, there’s going to be an enormous gas line down the street. There’s going to be an enormous increase in the cost of food, in all the things we use oil for. Plastics, anything that has plastic would go up, if you see that price spike in petroleum products. So it’s that kind of thing that would then be outside the control of the United States that we would have to react to.

We have the ability to try and change standards in automobiles, to even consider the possibility of reducing oil consumption in some way. But if we don’t do it and someone else does, then that’s the kind of shock that everyone is going to see, and recognize, man, we have really been hit right between the eyes on this.

CURWOOD: Bill Allen is editor-in-chief of the National Geographic magazine. Bill, thanks for taking this time with me today.

ALLEN: Thank you very much Steve, I enjoyed it.

CURWOOD: To get a different perspective, I’d like to turn to John Felmy. He’s chief economist and director of policy analysis and statistics for the American Petroleum Institute. John, welcome to Living on Earth.

FELMY: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Now I gotta ask you this. We hear from folks who say the days of cheap oil are coming to an end, that oil production could peak sometime soon, say by 2016 and gradually head down from there. How accurate do you think these predictions are?

FELMY: I don’t think they’re at all accurate. Folks have been arguing that we’re gonna run out of oil very soon for the last 100 years. But unfortunately the facts don’t prove them correct. Each year we tend to find more oil than what we consume, so we build our reserves. And as long as that happens, the end is not in sight.

CURWOOD: So from your research, what would you say is the worst case scenario for the global oil supply that you consider in your long range planning? I mean, at what point is there gonna be tightness in the supply? Is it five years, ten years, twenty, fifty, 100, 200, at what point does your research say, well, we should be concerned?

FELMY: First of all we’re never going to run out of oil, it’s a question of the price and the tightness as you indicated. It’s clear that there are abundant resources, we’ve got a trillion, maybe 1.2 trillion barrels of oil that we know about, and there’s probably twice that that we haven’t simply found. The question is, will we be able to go about and get it? Will we be able to explore for the oil and will we be able to develop the resources that are the most promising?

CURWOOD: Ok, and the answer is?

FELMY: The real concern I have is for the restrictions to be placed on the industry and not allow us to do that. And then it could be short-term in terms of supply impact. So it’s really the political framework that I can see as a restriction on supply.

CURWOOD: What would those constraints be, John?

FELMY: Basically preventing us from developing resources where we know they are. Alaska’s an excellent example where we can produce 10 billion barrels of oil, but we can’t explore and produce it there. The outer continental shelves of both the West and East coast are another example, some Rocky Mountain areas. And then internationally there’s of course the politics of various countries that may prevent that kind of exploration. So it’s more of not being able to develop it that’s a big concern that I have.

CURWOOD: John, at some point in the years ahead, the economy’s gonna make a change in how it consumes energy, whether it’s over the near term or further out. At what point do you see economies making a shift away from burning oil?

FELMY: It’s likely not to change within our lifetimes. If you look at what share oil comprises of our consumption, it’s roughly 40 percent. There are very few other alternatives to oil, especially for transportation, that we can see. Developments such as hydrogen and other alternatives, whether they be electric vehicles or things like that are much further down the pike than we can see at this point. There are some promising alternatives that can be developed such as methane hydrates, which is natural gas frozen in ice crystals, which could perhaps play an important role say in the latter part of this century. But in the short run, the role of oil, coal, gas, nuclear, and hydro are likely going to be the same, and those are our conventional energy sources.

In Texas, a crew plugs a well abandoned by the owner when its flow slackened to a trickle. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004) In Texas, a crew plugs a well abandoned by the owner when its flow slackened to a trickle. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

CURWOOD: Now people say that if you were to take today’s dollars, that the last peak of oil back in the late 70s, early 80s, was about the equivalent of $70 a barrel. How close to accurate is that for you?

FELMY: When if you adjust for inflation, you’ll find that the price of a barrel of crude oil in 1981 was about $72 a barrel, and gasoline prices were almost $3 a gallon when you adjust for inflation.

CURWOOD: So from that analysis you would say that we have a long ways to go in the present price run-up before we feel the discomfort of the 1970s, 1980s?

FELMY: Well, it’s clear we’ve already begun to feel some of the discomfort, because of course, higher oil prices mean lower incomes, lower purchasing power, a drag on the economy. But we’re far from the peak of oil prices that we experienced in the early 1980s.

CURWOOD: What would it do to the economy if we got back to those early 80s oil prices, if oil in fact was $70 a barrel?

FELMY: If we went from the current price which is slightly less than $40 a barrel, to over $70 a barrel, many economists would argue that it would likely push the economy into recession.

CURWOOD: And what are the odds of that happening at this point, do you think?

FELMY: At this point it’s very difficult to tell. It’s going to depend on first of all OPEC behavior, how well things turn out in Iraq, Venezuela, Nigeria. And then on the demand side, will the Chinese economy continue to grow at the very fast rate that it has been growing, and will other economies continue to grow, such as India. And each of these economies has increased their demand for petroleum dramatically, and has had a real impact on the world marketplace for crude oil.

CURWOOD: So maybe the question is not whether, but when we will see $70 a barrel oil.

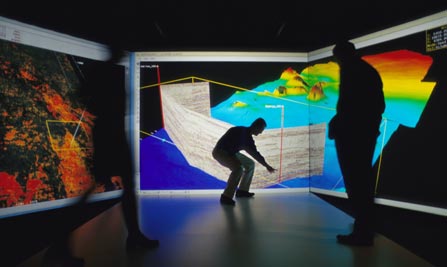

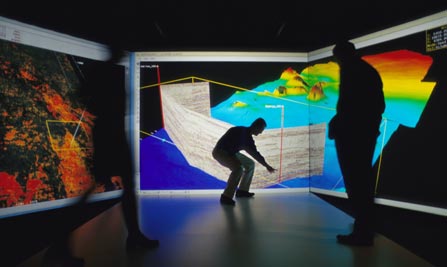

FELMY: Well, then you have to get back to the supply side. As we’ve seen, technology in the oil industry has continued to dramatically improve. We have been able to find oil much more easily than we have in the past at much lower cost. We’ve been able to produce oil in thousands of feet of water. We’ve been able to produce oil in extremely hostile environments, and we’ve been able to find it such that you can find a deposit of oil five miles away using the seismic technology that we have. So as long as the technology continues to develop at the pace it has been, then what it means is you’re able to bring more and more oil on stream more cheaply.

Like a surgeon’s CT scan, a three-dimensional seismic image reveals rock formations that may hold oil. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004) Like a surgeon’s CT scan, a three-dimensional seismic image reveals rock formations that may hold oil. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

CURWOOD: Now how do these new oil recovery technologies compare with the traditional of drilling the industry was built on? Particularly cost-wise?

FELMY: They’ve brought the cost of finding and producing oil down dramatically. We’ve seen over even in the last 20 years a dramatic fall in what we call finding costs of oil, so that we’re able to find it and produce it for far less than we did even a short period of time ago. It’s really a wonderful example of how American industry has responded to the challenge.

CURWOOD: At what point do you think that oil will be a smaller part of the energy mix than it is today?

FELMY: I don’t see oil taking up a smaller part of the energy mix until the latter half of the century.

CURWOOD: Ok, well this is helpful, so the latter part of this century, so we’re looking at maybe 2050 or so, in the second half of the century, that we’ll see this gradual shift away from oil?

FELMY: Well, it’s hard to even say at that point. I think the latter half of the century, I would think more of as the last quarter of the century. So maybe I’m using improper English, which is typical of a central Pennsylvanian, but I see that we’ll continue to develop more resources, natural gas will continue to grow in share, primarily in electricity generation. But it’s going to be very, very difficult to shift off of oil for transportation, until we see some fundamental breakthroughs in the technologies involved.

CURWOOD: John Felmy is chief economist and director of policy analysis and statistics for the American Petroleum Institute in Washington. John, thanks for taking this time with me today.

FELMY: Thank you very much, Steve, thanks for having me.

Related links:

- National Geographic Magazine

- American Petroleum Institute Back to top

CURWOOD: Just ahead: tracking the trail of the eastern cougar. First, this note on emerging science from Jennifer Chu.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

CHU: New research from England suggests that ducks, like their human counterparts, have regional accents. According to Dr. Victoria de Rijke of Middlesex University, a duck’s environment is a big factor when it comes to fine-tuning its dialect. De Rijke recorded the various sounds of Cockney ducks in the heart of London and their Cornish cousins at a farm in Cornwall. The mallards were all born and bred in their respective locales. And after some careful listening, de Rijke noticed some audible differences.

[SOUND OF CORNISH QUACK]

CHU: These Cornish ducks communicate in long, relaxed quacks. De Rijke attributes this to the slow pace of country living.

[SOUND OF COCKNEY QUACK]

CHU: These city ducks prefer louder, brassier quacks. De Rijke believes that the fast pace of London breeds louder, more stressed ducks. These quackcents are much like the accents of human inhabitants of the same regions. Cornish speakers are known for their more open and drawn out sounds, whereas the Cockney brogue uses shorter and more guttural vowels. In the future, Dr. De Rijke hopes to take this duck research abroad, and explore the quacks of Scottish, Welsh and Irish fowl throughout the British Isles.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Jennifer Chu.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for NPR comes from NPR stations, and: The Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving Math and Science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12; The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, making grants to improve the health and health care of all Americans. On the web at rwjf.org; The Annenberg Foundation; and, The Kellogg Foundation, helping people help themselves by investing in individuals, their families, and their communities. On the web at wkkf.org. This is NPR, National Public Radio.

[MUSIC]

Related link:

The Quack Project Back to top

[LETTERS THEME]

CURWOOD: Time now for comments from you, our listeners.

[LETTERS THEME]

CURWOOD: Our interview with Dawn Prince-Hughes, author of “Songs of the Gorilla Nation,” touched a lot of listeners. She told us about growing up with a form of autism called Asperger’s syndrome, and how her interactions with gorillas helped her understand herself.

The discussion struck a chord with Robert Porrazzo, who hears us on WEDW in Stamford, Connecticut. Like Dawn Prince-Hughes, Mr. Porrazo was not diagnosed with Asperger’s until he was an adult. And while more attention has been paid to the disorder in the last decade, Mr. Porrazzo laments what he says is the lack of funding for services. “My Asperger’s,” Mr. Porrazzo writes, “is my block in the road of life.”

Our piece on taxidermy raised the hackles of some listeners. Norm Phelps of the Fund for Animals listens to the show on WYPR in Baltimore, Maryland. He writes, “Taxidermy exists to support trophy hunting which is nothing more than killing harmless and helpless animals for ego gratification and bragging rights.”

Katherine Bowman of Traverse City, Michigan, expressed dismay that we didn’t explore the chemicals used in taxidermy. Ms. Bowman used to do taxidermy and tanning until she “woke up and decided I must be part of the solution to creating a healthier and sustainable world.” She continues, “There is just no environmentally conscious way to dispose of used taxidermy chemicals….what kind of legacy would I be leaving future generations?”

And finally, an apology for an error. Sid Miller of New York listens to us on WNYC and wrote in to take us to task for a comment we made in our coral reefs story. We compared a damaged coral reef to “a ragged neighborhood in the south Bronx” and Mr Miller says that reference is not only “untrue” but “prejudicial.” We here at Living on Earth agree and apologize. That comment was originally edited out of the broadcast and got back into the show tape by mistake.

And if you have a gripe, or hear something you like, you may call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88. Or write us at 20 Holland Street, Somerville, Massachusetts 02144. Our e-mail address is comments@loe.org. Once again, comments@loe.org. And you can hear our program, and our previous programs, for that matter, by visiting our web site livingonearth.org. That's Living on Earth dot org.

Back to top

CURWOOD: The big cat scientists call Puma concolor goes by a number of common names in the U.S.: puma, panther, mountain lion, catamount, cougar. The long list of names reflects the animal's wide historic range: people once encountered the cats in nearly all wooded parts of North America.

Mountain lions still inhabit much of the West. But wildlife experts say the cat no longer exists in the East; hunters and settlers wiped it out long ago. Or did they? From the Southern Appalachians to New England, hundreds of people insist the big cats still roam remote patches of the eastern states. And they're determined to prove the experts wrong. Living on Earth's Jeff Young reports.

[TRUCK ON HIGHWAY, INTERIOR]

YOUNG: Todd Lester should be asleep. He just worked the night shift in a West Virginia coal mine, then showered, pulled on one of his mountain lion t-shirts, and drove four hours to this remote part of the Monongahela National Forest. Now he’ll spend hours in the wet woods in search of something most experts tell him does not exist.

LESTER: Yeah it probably is an obsession. You know, somebody’s calling you a liar and you know what you saw. It does something to ya.

YOUNG: Lester spends most his free time traveling these back roads and trails in a quest for photographic evidence of the animal he says he caught sight of some ten years ago: an eastern cougar.

[TRUCK COMING TO STOP, DOORS OPENING, BOOTS TRAMPING ON WET TRAIL]

YOUNG: Each month he places a couple dozen camera traps--cameras triggered by motion and heat sensors--in an effort to monitor all of the nearly one million acres of national forest here.

LESTER: So camera number 18 got 30 on it. So that done real good. And just one cougar is all we need.

YOUNG: The coal miner has become a self-schooled cougar expert. He knows the intimate curves of cat’s paws by their tracks. He recites in hushed detail the deer carcasses left by a cougar’s ambush: bite marks on the neck, disemboweled and partly buried in leaves.

|

The cougar Tecumseh reclines in Coopers Rock Mountain Lion Sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers) The cougar Tecumseh reclines in Coopers Rock Mountain Lion Sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers)

|

And he knows the routes a cougar would likely take through this forest. That’s where he straps his camera traps to trees.

And he knows the routes a cougar would likely take through this forest. That’s where he straps his camera traps to trees.

LESTER: Well, I mainly look for good well used game trails and old logging roads or railroad grades or something like that and I try to get in remote areas where there’s not a lot of human activity. That would be the places that a cougar would use. But it’s really a shot in the dark y’know, a cougar could come within 50 feet of the camera and cut off trail so its…

YOUNG: So what do you think when you’re collecting these up? Are you excited, you think maybe this is the one that’s going to have the shot on it?

LESTER: Yeah I’ll tell you, you take these pictures to Wal-mart, you know, and you take 20 rolls of film in and you give them to them and they do an hour service on them. One-hour-photo. Once you get all the pictures you know I take ‘em out to the truck and I’m like a little kid on Christmas morning, you know I can’t wait to open ‘em up and look at the pictures.

YOUNG: Last year’s camera traps yielded 639 shots of deer, 204 black bear—one destroyed the camera. There were 40 startled coyotes, 20 bobcats, various raccoons, hikers, hunters and mountain bikers. One shot was labeled unknown; the tawny animal was too close to the camera to identify.

LESTER: And then you go through all of ‘em and none of ‘em’s got a cougar on it, you know what I mean. Then your heart’s kinda broke, then you think of all the work you put into it and the time you put into it and it didn’t pay off. So one minute your emotions are real high and the next minute you’re crushed (laughs).

YOUNG: All this started for Lester back in 1983 while he was coon hunting not far from his home in southern West Virginia. He was looking for one of his hunting dogs and instead found a cat.

LESTER: Seemed like, you know, when we made eye contact, you know standing there looking at each other, and the cat turned and left, it seemed like it took a piece of me with it, you know. And I’ve always wanted to prove, you know, that they was here, you know. It captured a piece of my heart, you know, and really got me interested in it.

YOUNG: He later found tracks an expert confirmed were those of a cougar. Lester had heard of other such sightings around Appalachia. He started the Eastern Cougar Foundation to record them. The foundation was soon taking in hundreds of cougar accounts each year from all over the eastern US. But wildlife officials generally recognize only one small population of cougars in the east: the endangered Florida panther. So when Lester and others phone officials with cat sightings from elsewhere around the east, they are often met with skepticism.

NICKERSON: I’ll believe in cougars when one lands on my lawn piloting a flying saucer.

YOUNG: That’s Paul Nickerson, an endangered species biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

NICKERSON: Here’s the painful reality. It’s a wonderful romantic notion that wild cougars exist here because wild cougars engender a lot of passion just like wolves do. And everybody in their heart of hearts wants to believe that they’re out there but I’ve been looking at this stuff for 25 years. They’re just not here! They’re just not here as a breeding species.

YOUNG: Skeptics say most of those who “see” cougars really see something else: bobcats, dogs, deer. And the few sightings and tracks that are confirmed, like Lester’s? They say those animals are probably escaped captives, pets let loose after becoming unmanageable.

Mark Jenkins knows all too well how many cougars are unwisely kept as pets.

[JENKINS AND GROWLING CAT, GATE OPENING]

Mariah is one mountain lion kept at the Coopers Rock Mountain Lion sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers) Mariah is one mountain lion kept at the Coopers Rock Mountain Lion sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers)

YOUNG: Some of the cats end up in his Coopers Rock mountain lion sanctuary outside of Morgantown, West Virginia.

JENKINS: This is Tecumseh

[CAT VOCALIZING]

JENKINS: You can hear him talk right there, they make about 12 different vocalizations. And he’s just greeting us here.

[CAT GROWLING]

YOUNG: This has aroused some interest here obviously.

JENKINS: Right, they do see the meat here so he’s getting a little excited

[CAT GROWLING, HISSING]

YOUNG: It’s easy to see why someone might want to release a cougar once it turns into 180 pounds of unpredictable predator. It’s also easy to see why people want them as pets in the first place. The cubs are adorable, and the big ones can still be as affectionate as your little Tabby.

[SOUND OF CAT MEWLING]

JENKINS: They do purr. They’re the largest cat in the world that still purrs like your house cat purrs.

YOUNG: Participants in the Eastern Cougar Foundation’s recent conference visited Jenkins’ sanctuary for at least one guaranteed cougar sighting. Many in the group claim to have seen the cats in the wild, and in some unlikely places: Ohio, Massachusetts or Rhode Island. That’s where Bill Betty says he spotted one not far from his home.

BETTY: Up from behind the log a mountain lion stood up and I saw the tail, it was probably three or four inches in diameter and about three feet long. That was really one of the most exciting moments that I can recall in my life.

YOUNG: Betty says he’s no tree hugger or animal rights type. He listens to Rush Limbaugh, works for a defense contractor, and he’s getting pretty tired of his co workers busting his chops about seeing a mountain lion behind every tree.

BETTY: People who see mountain lions or think they see them are often subjected to a lot of ridicule. And that’s a concern. You don’t want to have people to make fun of you. And that’s one of the problems we have, getting witnesses to come forward to talk to us about what happened. But I think really the difference between me and other people that do this is that I’m not guessing that there are mountain lions in New England, or I’m supposing. I know they’re here.

[PEOPLE MILLING ABOUT AT CONFERENCE HOTEL]

YOUNG: At times the conference seemed like a sort of support group for cougar true believers who must endure the scorn of skeptics. But there was more to it. Experts like veterinarian Jay Tischendorf were on hand for polite but hard-nosed analysis of alleged cougar evidence. Bill Reichling says he’s seen cougars in Southern Ohio. He showed Tischendorf some plaster casts of tracks.

REICHLING: I was thinking a cougar or cat with a young one because we found where one or the other had killed a rabbit right along a chain link fence so then I found this.

TISCHENDORF: I would really bet, and again I don’t know if I’d bet my paycheck, but pretty sure that this is a canid track of some kind. These claws if you look at the where base of the toe would be—

REICHLING: Uh-huh. It’s right there.

TISCHENDORF: Somewhere in this vicinity, you know.

REICHLING: I was thinking they were claws that came down but OK.

YOUNG: Turns out the tracks are of a dog and a bobcat. A Massachusetts man who says he saw a mountain lion from his back porch shares some video he shot.

[PEOPLE VIEWING VIDEO, COMMENTING]

MALE 1: The coloring isn’t right for a mountain lion. Looks like a Siamese cat.

MALE 2: Yeah looks like a siamese cat to me, too.

MALE 1: Yeah, tail’s not long enough for cougar…

YOUNG: The animal in the video is a cat--a house cat. Tischendorf is diplomatic with his debunking. He shares this fascination with mountain lions and says he understands why people want to see cougars so much that they think they see them.

TISCHENDORF: If I had to put my finger on it in a general sense I think the mountain lion probably embodies everything that many of us would long to be: lithe, muscular, intelligent, capable, confident, a survivor, adaptable. And I think it’s also a reminder that nature is very wild, so I guess a lot of us like to think that perhaps man doesn’t have all the answers, and that nature still has a few aces up her sleeve, and this puma in the east story may be one of those. But I think the true skeptics, the scornful skeptics, will eventually have to eat a little bit of crow because it’s hard to deny the hard evidence that we’re seeing right now, particularly in the Midwest and the Great Plains.

YOUNG: On the Foundation’s maps showing recent cougar sightings, the Midwest and Great Plains states are the hotspots. Scat, tracks, and photos have been confirmed across the area and a cougar biologists had tagged was killed by a train on the Oklahoma/Kansas border—more than 600 miles from its home range. It’s enough to catch the attention of the Cougar Foundation’s lone skeptic, biologist Dave Maehr. Maehr’s a professor of large mammal conservation at the University of Kentucky. He doesn’t put much stock in most eastern cougar sightings, but recent reports tell him the Western cats could be on the move.

MAEHR: Now I think something is happening, I think there’s a phenomenon underway where western populations or most nearby western populations are expanding for one reason or another. There’s some very compelling evidence that something’s happening that’s very different than what’s been occurring over the last century. And I think it is just a matter of time before they are back here.

YOUNG: Maehr says any official effort to reintroduce mountain lions to the east would certainly fail. Habitat is highly fragmented, and people would likely resist putting a new predator in their backyards. But the cats seem to be offering to reintroduce themselves. That’s one of three explanations for cougars in the east: that the cats are gradually migrating back to historic ranges, much as the coyote did years ago. The second explanation is that the few isolated cats in the east are just escaped captives. The third is that they never went away. That’s the theory coal miner Todd Lester believes.

[SOUND OF BOOTS ON WET TRAIL]

YOUNG: It’s what keeps him going back to the woods on weekends. He scans topographic maps dense with rugged hills, looks out from this ridge onto miles of misty green and thinks.

LESTER (walking and talking): Aw, you can go over here on edge, you know, look off, man that’s a lot of territory.

YOUNG: Mountain lions could have survived here.

LESTER: Lot of people we talk to they’ve got the impression that the whole east coast is one big large city y’know, a continuous city, and they say no, there’s no way cougars could survive there. And I’ve asked ‘em well have you ever been to the Appalachian mountains? They’s a lot of habitat for cougars.

[MOUNTAIN BIKE PASSES BY IN THE MUD]

BIKER: What’s going on?

YOUNG: Just then a trio of mountain bikers stops, curious about Lester’s camera equipment. And at the mention of the word cougar, mountain biker Joey Boyle gives Lester another sighting account to add to his collection.

BOYLE: I knew it was a cat, a big cat, because it had that big long thick tail. I rode with it for 100 yards or something and then we got to a dead end and there was a huge pile of dirt and that thing was just gone, it just bounded out of nowhere. It was pretty amazing.

YOUNG: Lester listens intently and thanks Boyle, but he’s remarkably unexcited. Boyle’s account is years old and Lester has taken in more than three thousand such reports. What he needs now is to go beyond sightings to hard evidence--the kind he’s sure his camera traps will produce.

LESTER: I woulda thought, you know, we woulda got pictures sooner, you know, if there was a population here but, you know, I still haven’t given up hope yet. I think we’ll eventually get a picture, I really do. Yeah, I just can’t foresee myself giving it up now, y’know?

YOUNG: Obsessions are like that. For Living on Earth I’m Jeff Young in the Monongahela National Forest.

Related links:

- Cooper's Rock Mountain Lion Sanctuary

- Eastern Cougar Network

- Eastern Cougar Foundation Back to top

CURWOOD: And for this week - that's Living on Earth. Next week – At MIT’s Media Lab, a professor and his graduate students are exploding the boundaries of music – creating new instruments, new ways of composing, and new ways of understanding musicians and audiences.

MACHOVER: You begin by creating a pulse, and then you can play a simple pattern like [SOUND OF PATTERN BEING PLAYED] and then it hops over to another of the beat bugs.

CURWOOD: A new concept of music, next time on Living on Earth. And between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to livingonearth.org. That’s livingonearth.org.

[STORM NOISES]

CURWOOD: Before we go – we get drenched by an evening thunderstorm.

[EARTH EAR: HERE-INGS]

CURWOOD: What begins as a drizzle turns to a downpour, drumming rhythmically on a metal roof. Steve Peters recorded these sounds near the foothills of the Manzano Mountains in central New Mexico.

[EARTH EAR: HERE-INGS]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced for the World Media Foundation by Chris Ballman, Christopher Bolick, Eileen Bolinsky, Jennifer Chu, Ingrid Lobet, Susan Shepherd and Jeff Young.

Our interns are Jennie Cecil Moore, Diana Schoberg, and Monica Wright. You can find us at livingonearth.org. Our technical director is Paul Wabrek. Al Avery runs our Web site. Alison Dean composed our themes. Special thanks to Ernie Silver and Carl Lindemann. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes form the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and Stonyfield Farm – organic yogurt, cultured soy, and smoothies. Ten percent of their profits are donated to support environmental causes and family farms. Learn more at Stonyfield.com; The Ford Foundation, for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, for coverage of western issues.

NPR ANNOUNCER: This is NPR – National Public Radio.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea. Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment. The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs. Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

| | | |

Discovered in 1911, California’s South Belridge field has produced more than a billion barrels of oil. Tapped by 10,200 wells, it may have several decades of life left – but with a declining output. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

Discovered in 1911, California’s South Belridge field has produced more than a billion barrels of oil. Tapped by 10,200 wells, it may have several decades of life left – but with a declining output. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)  Tar fields along the Athabasca River in Alberta, Canada. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

Tar fields along the Athabasca River in Alberta, Canada. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)  Tar oozes from sand along the Athabasca River. Formed millions of years ago as oil leaked from reservoirs, the tar, or bitumen, permeates more than 15,000 square miles. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

Tar oozes from sand along the Athabasca River. Formed millions of years ago as oil leaked from reservoirs, the tar, or bitumen, permeates more than 15,000 square miles. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)  In Texas, a crew plugs a well abandoned by the owner when its flow slackened to a trickle. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

In Texas, a crew plugs a well abandoned by the owner when its flow slackened to a trickle. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)  Like a surgeon’s CT scan, a three-dimensional seismic image reveals rock formations that may hold oil. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)

Like a surgeon’s CT scan, a three-dimensional seismic image reveals rock formations that may hold oil. (Photo: National Geographic Magazine, June 2004)  The cougar Tecumseh reclines in Coopers Rock Mountain Lion Sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers)

The cougar Tecumseh reclines in Coopers Rock Mountain Lion Sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers)  Mariah is one mountain lion kept at the Coopers Rock Mountain Lion sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers)

Mariah is one mountain lion kept at the Coopers Rock Mountain Lion sanctuary. (Photo: Gary Lake/WV Wallpapers)