July 16, 2004

Air Date: July 16, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

A Changing South Africa – Part One

View the page for this story

The Wild Coast of South Africa boasts beautiful beaches, sandstone gorges, and a diversity of plants, some found nowhere else in the world. During apartheid, the black homeland of the Transkei in the Wild Coast was passed over by developers and the region stayed relatively isolated. The region stayed pristine but the people living there remained poor. Now, a proposed toll road promises to bring development to the region, but at what cost? (12:45)

A Changing South Africa – Part Two

View the page for this story

We meet Tony Abbott, a world-renowned, self-taught botanist. He takes host Steve Curwood to a sandstone gorge in the heart of the Wild Coast and introduces him to newly discovered species that have yet to be named. (07:30)

A Changing South Africa – Part Three

View the page for this story

On horseback and on foot, Living on Earth travels through spectacular Wild Coast beaches, red sand dunes and the grassy hills that are home to the Xhosa people. Our host is Amadiba Adventures, South Africa’s only community-owned and operated eco-tourism business. (10:00)

A Changing South Africa – Part Four

View the page for this story

Rooibos, or red bush, tea is grown only in the western part of South Africa. The area has a unique climate and ecosystem. Climate scientists are working with farmers in a small town in the region to help them adapt their farming practices to predicted climate change. (16:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. South Africa is one of the three richest countries in biodiversity, but many of its people are poor. And now plans to create jobs by putting a highway through critically endangered habitat has environmental activists speaking out.

KAY: You certain have flora that is found nowhere else in the world. We have brand new species of plants that haven’t even been given names yet.

CURWOOD: But others say the region has been too poor for too long.

QUNYA: We are saying now to the people, even the environmentalists, they must compare and balance the issue of social needs and the issue of animals and trees, because we like trees and animals to be there, but you need to balance with the poverty along the coast.

CURWOOD: Also in South Africa, the emerging science of helping farmers adapt to global warming, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

A Changing South Africa – Part One

Thatched houses called rondavels are scattered throughout Amadiba land. (Photo: Hazel Lum)

Thatched houses called rondavels are scattered throughout Amadiba land. (Photo: Hazel Lum)

CURWOOD: From the wild coast of South Africa, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[BOY WHISTLES AND CALLS FOR COWS]

CURWOOD: As the sun starts to set a young boy of the Amadiba Tribe calls in the cows.

[WHISTLE]

CURWOOD: Nobody here in this community along the Wild Coast of South Africa is in a hurry, least of all the cattle that plod home along paths that have been worn for centuries. This is a place that time has mostly forgotten. The treacherous waters of the Indian Ocean off shore kept European explorers and settlers away, and during the years of racial apartheid, the Wild Coast was isolated in the so-called black homeland of the Transkei. Economic development mostly bypassed this region, and that’s led to some overgrazing of cattle; but, on the whole, there is little environmental degradation.

The Wild Coast still has stunning undisturbed beaches and hundreds of species found nowhere else in the world. But with the arrival of democracy in South Africa, there are new pressures on the fragile balance between humans and nature. The impoverished people here aspire to do more than scratch out a subsistence life based on a porridge made from corn called mealies, and they are making their voices heard.

Zamile Qunya is the chairman of, the Amadiba Coastal Community Trust.

QUNYA: The people are cultivating and find mealies, which is the only food that they have, and also they do fishing. And they were working cutting sugar cane. And we have a very problem of people that are illiterate in our area. So our people are very starving. It’s the poorest of the poor. There are people that live with no food in my area.

CURWOOD: South Africa is the richest country in Africa, with an economy that is two thirds of the entire continent. Cities such as Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban have glittering malls, plenty of fast cars and luxurious homes.

The people here on the Wild Coast would like to share in the bounty, but they have some choices to make. One path would take them in the direction of development that would sustain their rich traditional Xhosa culture and unique ecology. Another would simply trade their economic hardships for the impoverishment of their environment and culture.

Already the natural geology and beauty of the Wild Coast is attracting developers who see the potential of profits in bringing highways, mines, hotels and casinos. As an alternative, the Coastal Trust began an experiment with eco-tourism in 1997.

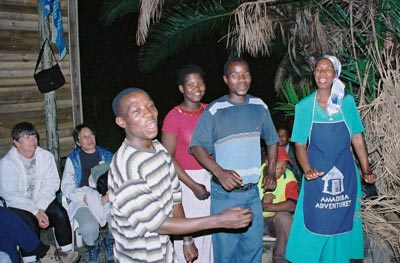

[SINGING AND CLAPPING]

CURWOOD: Around the fire at the Kwanyana campground, workers for the community eco-tourism project called Amadiba Adventures are sharing dances, songs and stories with their tourist visitors. This song is about learning not to fear the baboons, which can be ferociously pesky in their quest for food. The singers stomp in place around a circle, gyrating their arms and torsos in a monkey-like motion. [BABOON SONG UP AND UNDER]  Kwanyana camp crew (Photo: Karen Wildfoerster) Kwanyana camp crew (Photo: Karen Wildfoerster)

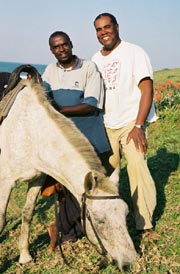

CURWOOD: The idea behind the Amadiba Adventures tours is simple: Get folks who like the outdoors to come and camp, hike, canoe and horseback ride in this unique ecosystem and it will generate jobs. Getting started wasn’t easy. [CRICKETS UP AND UNDER] CURWOOD: When a white man named Simon Speering, who enjoyed hiking in the area, brought the idea of eco-tourism to the tribe 1997, he was met with a lot of suspicion. But once the Amadiba tribe set up a trust with local ownership and control, Lindele Mxhuma, a guide for Amadiba Adventures says, local people became enthusiastic. MXHUMA: Because they see that it gave them some money in the beginning. So they were happy to see it happening here. And they have seen that no one took their land away as they thought. People come and see our rivers and bays and they pay for just seeing all those things and then they go back home, not damaging anything. CURWOOD: Lindele’s work is to shepherd visitors along the Wild Coast on horseback and on foot. Part of his job is sharing his culture, like telling stories about playing games and tending cattle as a Xhosa boy. MXHUMA: There are so many things that you did as boys, you know. When you are looking after the cows the other boys that were older than us, they used to come to us and make us fight each other, you know. What they did, they used to put a stick between you and the other boy. If that boy jumps the stick, then you have to fight because they will say he has defeated you, so you have to fight. If he comes across the stick you have to fight until he goes back. But not big fights, no. Just fights for boys, you know. We didn’t have grudges for that. [FOOTFALLS, CONVERSATION]  Lindele's family (Photo: Steve Curwood) Lindele's family (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Lindele’s father’s home is sometimes a part of the Amadiba Adventure experience. Visitors sleep at the compound, which has several round huts with thatched roofs, whitewashed walls and dirt floors, and a small square house for dining. There’s no sanitation beyond an outhouse, no easy access to fresh water or medical care or schools, and no lights beyond candles that they are lucky enough to afford, thanks to their modest income from the tourism project. [CHICKENS PEEPING] CURWOOD: But Lindele’s family is among only a fortunate few, observes Amadiba Trust chairman Zamile Qunya. Seven years into the tourism project, despite a stream of business from South African and European tourists, there are still no jobs for the vast majority of people here and he is disillusioned.

QUNYA: But I must tell you the reality fact as a chairperson, and everybody will support me: there was no big impact in terms of job employment, in terms of spin-off that the tourism has created other jobs. What we are doing is that most of the people that are working in tourism as the tour guide, they are part-time and they are small people that can cook because of the tourists arriving. But they didn’t make any big impact in terms of the poverty we have and the population we have. CURWOOD: So to bring more jobs and income to the area, Mr. Qunya tells me he has become a proponent of a project to build a highway that would link the cities of Durban and East London with a high-speed toll road. He has some powerful allies who agree. OLVER: The Transkei itself has been historically very underdeveloped. It's an area with the highest levels of poverty in South Africa and the lowest levels of infrastructure. CURWOOD: Crispian Olver is the Director-general of Environment and Tourism for South Africa. OLVER: You know, for a long time government has been wanting to bring development to that area. And the best strategy for doing it that government has come up with is linking this development corridor to the north and the development corridor to the south, and, in a sense, creating an eco-tourism route that will then bring jobs and bring investments to Transkei. And, in particular, along the coast, to the wild coast. CURWOOD: But the idea is steeped in controversy. For a while there was a debate over whether major parts of the largely pristine Wild Coast should become a national park. That discussion is now on hold, but the concerns that gave rise to the proposal are still very much on some people’s minds. South Africa is one of the three most biologically diverse nations on earth, with many endemic species -- that is, those that are found nowhere else. In fact, the World Wildlife Fund lists this part of the Wild Coast, known as Pondoland, as a critically endangered global hot spot. Cathy Kay is National Director of Conservation for the Wildlife and Environment Society of South Africa, the largest environmental organization in the country. She says putting a toll road through this sensitive part of the Wild Coast doesn’t make sense.  Cathy Kay Cathy Kay

KAY: It’s the heart of the Pondoland Center of Endemism and was recognized by Conservation International at the World Parks Congress for its uniqueness, for its biodiversity and its plant species. CURWOOD: For example, what’s in the biodiversity here that’s of so much import? KAY: You certainly have flora that is found nowhere else in the world. You have the Pondoland’s Tea Man’s Bush which is over a thousand years old, growing in some of these valleys. We have brand new species of plants that haven’t even been given names yet. CURWOOD: Just to the north of the Wild Coast, the beaches are crowded with hotels, condos and casinos. And while most of the new toll road would follow the present alignment of a two-lane road far away from coast, an 85-kilometer section would slice right through critical coastal habitat. KAY: The only bit that we’re complaining about is this 85 kilometers. CURWOOD: Again, Cathy Kay . KAY: For the rest of the other 85 percent of the road, we have no problem. It’s only this 15 percent that we’re saying, “if you bring it this close to the coastline, what you’re going to have is another south coast” which is across the river from here where there’s solid wall-to-wall concrete right along our primary dunes, right across our estuaries and it’s actually destroyed the aesthetics of the coast. CURWOOD: But Zamile Qunya of the Amadiba Trust says building the road would pay social and economic dividends for years to come. QUNYA: We don’t have any industry, any factory in Transkei. So starting to put a road, which you make an access to, you will build garage, you will create a lot of employment. We are saying now to the people, even the environmentalists, they must compare and balance the issue of social needs and the issue of animals and trees. They must not be biased on trees and animals. They need to balance it because we like trees and animals to be there, but you need to balance with the poverty along the coast. CURWOOD: Zamile Qunya also favors another proposal to bring jobs and income to the area: a mine that would dig out the titanium and other valuable minerals that have been found in the red sand dunes just inland from some of the most spectacular beaches. The Environment and Tourism Ministry opposes the mining, which they say could pollute the estuaries and threaten the area with sprawling shantytown development with people who come looking for work. Mining might create 700 jobs that would be lost when the minerals run out, according Environment and Tourism Director General Crispin Olver, as opposed to the 9,000 tourism jobs that he says the area could sustain over the long haul. Still, he cites the bid to put in a mine as an urgent reason to find alternate means of development, including a toll road and more tourism. OLVER: A solution that doesn't address poverty is ultimately going to lead to the entire erosion of the environment in that area. So, you know, one has to come up with a development strategy. The question is what development strategy. And for me, the basic choice on the Wild Coast is are we able to put an eco-tourism strategy on the table that works and brings jobs and brings investment into the area? Or are we going to allow alternative strategies like mining -- or I know there are a couple of agricultural proposals -- allow those strategies to go ahead? But it's going to be one or the other. [CRICKETS]  Steve Curwood and guide Lindile Mxhuma Steve Curwood and guide Lindile Mxhuma

CURWOOD: Lindele Mxhuma, the tour guide, feels strongly about what he expects would happen if the mine comes. MXHUMA: This project that we have here will die. Definitely, it will die if the mining come here. Tourism and mining don’t go together. CURWOOD: And what about putting a toll road through the Pondoland Wild Coast? MXHUMA: Yeah, I don’t think that would be a good idea or a bad idea. You know, I’m neutral. What makes me neutral is that yeah, we do need the road, but we don’t need it very close to the coast. [SINGING] CURWOOD: We’ll take a closer look at the biological diversity of Pondoland and find out more about the eco-tourism project involving Lindele and the Amadiba Trust just ahead, so stick around. I’m Steve Curwood and you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. Related link:

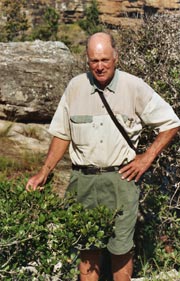

A Changing South Africa – Part Two[JOSTLING TRUCK] CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, in the Pondoland along the Wild Coast of South Africa riding along in a four-wheel drive truck with Tony Abbott. Tony is perhaps one of the foremost amateur botanists in the world. He’s an Englishman who left Zimbabwe more than two decades ago to try his hand at growing bananas in South Africa. Tall, craggy, and quick with ironic wit, he started hiking with a well-known amateur botanist throughout the region and learning plants. Today, even though he has no formal training, Tony has been credited with discovering at least five species and having them named after him in the scientific literature. He says there are even more to discover in the Pondoland, which is one of perhaps fifty major botanical regions in the world still largely in its natural state -- and famous for the rare Pondo Man’s Tea Tree. We’re off to see some of the plant life and other natural features near Nyameni Falls in an area that has been staked out as a possible route for a toll road linking Durban and East London. [DOORS SLAM, FOOTFALLS] CURWOOD: Tony Abbott gets out of the car and heads towards some bushes. Suddenly, the vista opens up into a massive sandstone gorge with a spectacular waterfall cascading down the far wall. He describes why the Pondoland region, which is two thirds of the size of the state of Rhode Island, is a biodiversity hotspot.  Botanist Tony Abbott (Photo: Steve Curwood) Botanist Tony Abbott (Photo: Steve Curwood)

ABBOTT: It’s not very big. It’s 180,000 hectares, and it’s the smallest of these centers in the country. The most exciting thing about it is that many of the plants which are special here occur in very small distributions. And we always quote the Pondoland Palm as being the sort of flagship species of confined distribution because it grows along the estuaries of two rivers only. CURWOOD: Which ones? ABBOTT: The Mtentu and the Mzikaba, just to the south of us here. It only grows on the north bank of those estuaries, and it doesn’t grow anywhere else in the world. But we have rarer plants than that. We have the Pondoland Ghost Bush, which for a long time was known from the odd single specimen; in 1965, we knew of one. And then that died, and then we found another one. And it was only in 2001 that we found a small breeding population. And that is the only place that they breed. So this is a plant which is obviously on its way out, because at the turn of the century -- not this century but the turn of the last century, in the 1900s -- it was spoken of as being fairly common on these sandstone waterfalls. CURWOOD: Tony, how many different species of plants are there in this region, do you think? ABBOTT: We talk about more than 2,000 species of plant in the Pondoland Center Plant Endemism, with certainly 10 percent of those endemic. But we’ve got a much closer idea with the Umtamvuna Nature Reserve. There it’s three and a quarter thousand hectares in extent. There’s 1,350 species of flowering plant and another 100 species of non-flowering plant. So we’re talking about 1,450 species. And these I have collected and they are kept in a hyberium so I can say this number with confidence. And in that three and a quarter thousand hectares, you’re looking at sort of the same amount of number of plants that occur in the whole of the United Kingdom, which is quite, quite remarkable. So, we are very unhappy because there are major decisions being made about development in the area, and we believe that they are being made without taking cognizance of just how rich and diverse this area is. So I think, yeah, we have a big problem there.  A newly discovered species (Photo: Steve Curwood) I’ll show you on that point over there, there’s a new species of cabbage tree. Do you know what a cabbage tree is? CURWOOD: I’m afraid not. I know what a cabbage is, I know what a tree is, but I haven’t thought of them as being together. ABBOTT: This only came to light last year. There’s another tree further up which has only come to light this year. There’s a morning glory, a species of Ipomoea, which I’ve only seen on two different occasions. It’s never been seen before. There are so many. There’s a species of Erica, a Heath, which is awaiting description. And all these things are coming out and, unfortunately for me, I suffer from something I call orographic degeneration. STEVE: Okay. ABBOTT: And that means the mountains are getting taller [LAUGHTER] ABBOTT: I no longer walk like I used to walk and we need more young people to get out there into these sort of areas and to walk in the wilder parts. But one thing I must tell you, walking up here towards the falls with a group of people, we went in down river from here and we were walking up and there was an incredible sweet scent drifting down the river, superb scent. And we could see nothing that was flowering until we walked around a corner, and there was a new species of tree. It’s undescribed at this time. New species of tree flowering there with big yellow flowers, and this incredible scent filling the whole valley. And you know, to put across to people who are perhaps not interested in plants, the excitement and the thrill of seeing and experiencing something like that was a very, very special event in my life. It was superb. CURWOOD: (sniffing) Too bad you can’t smell things on the radio. (laughter) I’ve heard that you’ve had, what, some five trees named after you? How did that happen? ABBOTT: Well, it happens because first you’ve got to find things that are unknown. And people say, well how do you do that? How can you look at a tree or a plant or a shrub or a flower in the field and say that it’s new, it’s different? And the best way I can describe that is that – there goes a Lanner Falcon. There he goes. Isn’t he beautiful? Just coasting across the way. There he goes – – it’s like in your workplace or in your school, and you know all the faces. And suddenly a new person moves in there and you say, where do you come from? Now how do you know it’s a new person? And it’s exactly the same with a plant. You have a mind picture of the people that live in your area and you recognize them. And when somebody new comes in, doesn’t fit your mind picture, you recognize it. And it’s exactly the same with plants. CURWOOD: You have no degrees in botany? ABBOTT: No, no, I’m totally ignorant. I’m just a farmer. In fact, I usually say, “I’m just a banana farmer.” CURWOOD: But, of course, you know a lot more than that. ABBOTT: Well, it’s…if you have an interest, you don’t need qualifications at the beginning. You gain it all as you go along if you’re interested in it. And I don’t want the kind of deep qualifications, I don’t want to sit in an office in a hyberium studying through microscopes and writing vast papers on computers. Not my interest at all. This is where I want to be. This is where I’m happy. Out here with the waterfall in the background, Lanner falcon over the top, and there were some black swifts here just now, and all these wonderful plants that are my friends. [FOOTFALLS] CURWOOD: Tony Abbott is world-renown amateur botanist who lives in Pondoland on the Wild Coast of South Africa.

A Changing South Africa – Part Three[FOOTFALLS, CRICKET SONG] MXHUMA: It has so many things. Like desert-like areas, and forest, and all landscape, gorgeous. It’s because of its beauty. CURWOOD: Lindele Mxhuma loves his workplace: the Pondoland Wild Coast of South Africa. He works as a guide, leading tourists on foot and horseback to various attractions and campsite in the area [HORSES TROTTING IN SAND] CURWOOD: Riding horses along the beach, a group of Living on Earth listeners has joined producer Eileen Bolinsky and myself for a few days to sample an eco-tour led by Lindele. The Amadiba Coastal Community Trust has created these eco-tours as part of their efforts to bring jobs and income to the community without undermining the traditional culture or altering the landscape. JEFFERIS: The beaches are just a fascinating asset, just some of the most beautiful beaches I have ever seen. CURWOOD: Frank Jefferis is a Living on Earth listener from Illinois. JEFFERIS: Long, wide open beaches, no one there, with a big beautiful dark green dune from the foliage behind you. And beautiful rolling waves. It's just a beautiful asset they have here. [HORSES TROTTING ]

|

Zamile Qunya (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

Zamile Qunya (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

Michael Giles of Heritage Africa (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Michael Giles of Heritage Africa (Photo: Steve Curwood)  Sbongile Hlongwa manages the Kwanyana campsite (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Sbongile Hlongwa manages the Kwanyana campsite (Photo: Steve Curwood)  A cultivated rooibos field, after harvest. (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

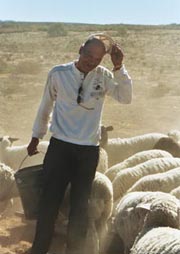

A cultivated rooibos field, after harvest. (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)  Koos Koopman and his sheep (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Koos Koopman and his sheep (Photo: Steve Curwood)  Koos Koopman

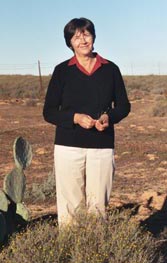

Koos Koopman  Mariette van Wyk (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

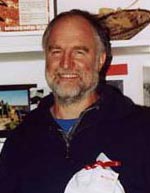

Mariette van Wyk (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)  Dr. Emma Archer (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Dr. Emma Archer (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Noel Oettle of the Environmental Monitoring Group (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

Noel Oettle of the Environmental Monitoring Group (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

Rhoda Louw (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Rhoda Louw (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Rhoda Louw measures a rooibos bush. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Rhoda Louw measures a rooibos bush. (Photo: Steve Curwood)