November 23, 2012

Air Date: November 23, 2012

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Hope for UN Climate Talks

View the page for this story

Talks open in Doha, Qatar November 26th for the 18th round of U.N. climate change negotiations. But climate change projections are increasingly dire and few express hope for consensus. Host Steve Curwood talks with Jennifer Morgan, Director of the Climate and Energy Program at the World Resources Institute. (06:05)

Recycling for Food

View the page for this story

Mexico City’s landfills are at capacity but the government has come up with an innovative way to encourage recycling. Economist journalist Tom Wainwright tells host Steve Curwood that Mexico City residents can bring recyclables to a market and trade them in for locally grown produce. (06:10)

Power Shift - Prospering Public Transportation

View the page for this story

Despite robust and rising ridership, many transit systems around the country are deeply mired debt, and Boston’s MBTA is a prime example. But there is a way out, according to Christopher Leinberger, a developer and professor at George Washington University. He has a plan called “value capture” that would use transit-related real estate profits to solve the MBTA’s fiscal problems and reduce Boston’s carbon footprint to boot. Leinberger discusses his plan with host Steve Curwood. (09:15)

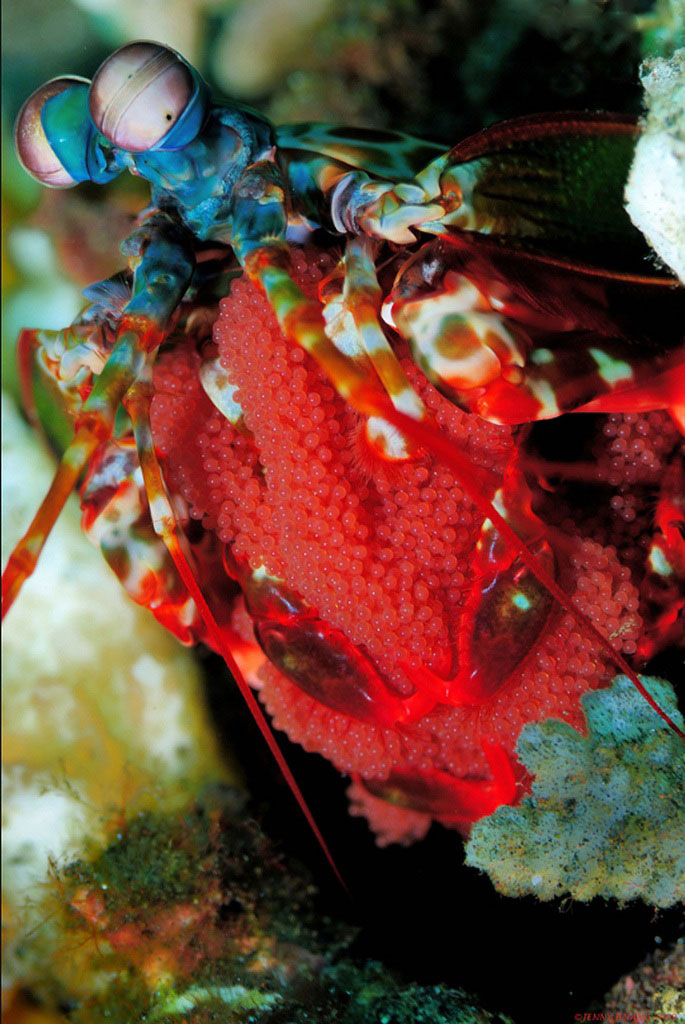

Science Note: Mantis Shrimp

/ Annabelle FordView the page for this story

The peacock mantis shrimp throws a surprisingly strong punch for its small size. Researchers have discovered that the shrimp can crack shells with its lightning fast punch. The composition of the shrimp’s club is now being used to inspire stronger and more lightweight military protective gear. Annabelle Ford reports. (01:45)

Tricky Lizards

/ Ari Daniel ShapiroView the page for this story

Creatures come in all shapes and sizes - and in the case of some lizards called Anoles, where they live is the key to the form they take. Ari Daniel Shapiro reports. (05:40)

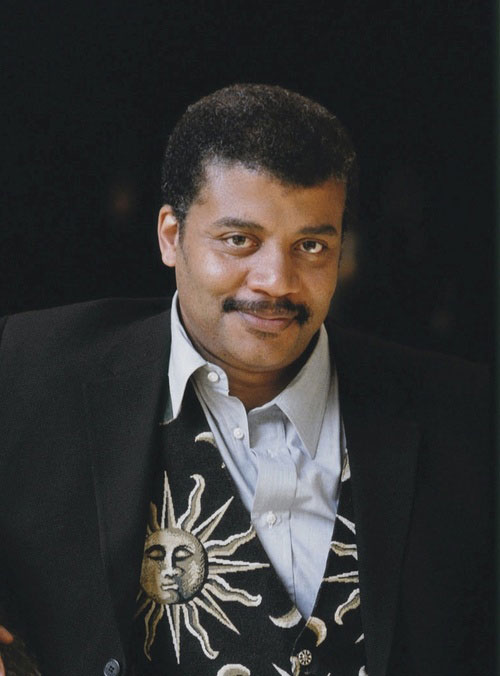

Superman of Astrophysics

View the page for this story

He's an astrophysicist extraordinaire, and director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York City. And Neil deGrasse Tyson is also now a comic book character. He talks with host Steve Curwood the latest developments in space news and his appearance in the Superman comic. (17:00)

A Visual Feast

/ Rod ClarkeView the page for this story

Before Thanksgiving 2012 has sunk over the memory horizon, Rod Clarke turns his attention to the horizon over his Wisconsin farmhouse in his poem Planning for Thanksgiving. (01:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jennifer Morgan, Tom Wainwright, Christopher Leinberger, Neil de Grasse Tyson, Rod Clarke

REPORTERS: Annabelle Ford, Ari Daniel Shapiro

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The next round of UN talks to try to fight climate change kicks off in Doha this month. Superstorm Sandy may add a new urgency, and perhaps the way we build and live in our cities could be part of the solution.

LEINBERGER: I believe that walk-able urbanism, the building of great walk-able places, will be the number one way we're going to address climate change.

CURWOOD: Also, the problems biologists face trying to track down the animals they research – especially when they're well camouflaged.

CASTAÑEDA: Like when you see them in the field, you have to look really hard to make sure that this is not a twig. And they stay still so perfectly that you'd have to wait to see them move and really realize there's a lizard there.

CURWOOD: We'll have lizards and a lot more this week, on Living on Earth.

Stick Around!

[THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm.

Hope for UN Climate Talks

Doha's skyline seen from the south side of Doha Bay. (Photo: Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Talks open in Doha, Qatar, for the 18th round of U.N. climate change negotiations at the end of this month. But as nations from around the world come together, climate change projections are increasingly dire and few express hope for a broad consensus.

One veteran observer of many rounds of these talks is Jennifer Morgan. She is the Director of the Climate and Energy Program at the World Resources Institute and is their lead representative at the upcoming meeting in Doha starting November 26th. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MORGAN: Thank you, good to be here.

WRI Climate and Energy Program Director Jennifer Morgan (Photo: CC flickr/ World Resources)

CURWOOD: So, what’s this session of the climate negotiations all about?

MORGAN: Well this session is actually a finalizing the rules session – not as exciting or as big bang of a meeting as previous years – but I think certainly people are hoping that ambition will also be on the table because not enough is happening right now.

CURWOOD: So, as they say though, the devil is in the details. What’s likely to get done and where are things likely to get stuck?

MORGAN: So, in the details you have number one, the Kyoto Protocol. Kyoto is important because it has institutions that people care about, it has a carbon market, it has a fund for developing countries and those things need to stay and be part of a bigger package in a couple of years. And countries like the EU and Australia are ready to move forward with the Kyoto Protocol, but they have to decide how long does the Kyoto Protocol last. That’s one big detail.

Or, for example, within the finance side of things, the fast-start countries have pledged money for it up to this year – what happens after that? That’s less of a detail and more of a fundamental thing: Is there new money on the table for developing countries to deal with the impacts of climate change?

CURWOOD: Back in 2009, President Obama and other world leaders agreed on this Green Climate Fund, which, what, promised $100 billion a year in financial aid to developing countries? The world economy is still pretty sluggish, what’s happening with the Green Climate Fund? You indicated it’s coming to the end of its first round of cash.

MORGAN: Countries in Copenhagen pledged funds for up to 2012. But there’s a lot of uncertainty between now, the $30 billion number, and how to get to $100 billion by 2020. And so that’s questionable. Will countries say that they’ll leave it at the same levels or increase it? And, certainly in an economic downturn, that’s difficult. But some countries like Germany seem ready to move forward and developing countries will certainly be looking for at least the same level of support that they’ve had.

2011 United Nations Climate Change Conference, Durban, South Africa. From left to right: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, President of South Africa Jacob Zuma, President of the Conference Maite Nkoana-Mashabane and UNFCC Deputy Executive Secretary Richard Kinley. (Photo: Wikipedia).

CURWOOD: The UN Climate Change conferences have become a magnet for criticism. They get labeled as antiquated, cumbersome, unproductive. Jennifer Morgan, from your perspective, what have these talks done and what alternatives do we have to this UN process?

MORGAN: Well, I think the talks have brought countries together and set a long term goal of staying below two degree temperature rise – I don’t think that would have happened without the United Nations. I think they’ve catalyzed further domestic action – many of the pledges that came forward over the last years from China and India and the United States, I’m not sure would have happened without the UN framework convention.

CURWOOD: Where is China in all of this? I understand that the government there is looking to install a 30 percent renewable electricity portfolio standard by the year 2015, which would put it ahead of the US in this process.

MORGAN: Well, China has taken quite substantial actions domestically. And in some cases, more than the United States. They have a strong renewable energy target, they have capped coal use in some places, they have strong efficiency targets. I don’t expect anything new from them for some time because they’re in a transition, but certainly domestic forces are showing they’re taking the issue seriously.

CURWOOD: What are the marching orders that the White House is likely to have given, do you think, for Doha. And what effect, if any, do you think superstorm Sandy will have on the American approach?

MORGAN: Well, I don’t think we know yet. I think the hope is that the White House will give in some ways a mandate to the delegation to press the restart button on its international climate diplomacy, and that the US will go to Doha with a much clearer strategy, and say: You know, we do want to keep global average temperatures below two degrees.

We hear and actually are now experiencing what the impacts of climate change look like and so the hope, I think, would be clarity from the US on this long-term goal. How is the US going to meet that 17 percent target they signed up for a couple of years ago, they haven’t made that clear yet to the world. And also, just a clear statement: we’re in this.

We’re not only starting a national conversation as President Obama said, but we’re moving into an international coalition building to really solve this problem. Thus far, it’s been more incremental tactics. I think the world is looking for the big strategy and leadership.

CURWOOD: Jennifer, I think what we’re hearing here and what we saw in New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, is what the small island states have been seeing all along. How are they feeling about these negotiations?

MORGAN: Well, I think the island states are feeling quite desperate. To be clear, they are not seeing the type of signals that other countries are really taking this seriously. And I guess that’s really the question for the developed countries and economies around the world: Will they start acting more like the island nations now, will they understand more what’s at stake, and be willing to take the political risks that it will take to get this job done? Because otherwise, those island nations and many areas – low-lying areas around the world – will have a short future.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is Director of the Climate and Energy Program at the World Resources Institute in Washington. Thanks for talking with us, Jennifer!

MORGAN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Website for the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Doha, Qatar

- More about Jennifer Morgan

- “Issues To Watch At The Doha Climate Negotiations (Cop 18)” by Jennifer Morgan

[MUSIC: Brad Mehldau “Always Returning” from Highway Rider (Nonesuch Records 2012).]

Recycling for Food

A Mexican market displays the type of produce that can be traded for recyclables in Mexico City. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Legend has it that the Aztecs founded Mexico City in the 14th century, ordered by one of their many gods to build a city where they found an eagle perched on a cactus with a snake in its beak. That eagle turned out to be on an island surrounded by a lake.

Over the centuries the Aztecs, and later the Spanish conquerors, filled in the lake and built a city that today is home to more than 21 million people. The buildings are famously sinking into the filled land and a more visible problem plagues Latin America’s biggest city…. trash. Many landfills are at capacity and rubbish is piling up in the streets.

So the city government has developed a unique way to deal with it. Tom Wainwright is the Mexico/Central America correspondent for the Economist magazine, and joins us on Skype. Welcome to Living on Earth!

WAINWRIGHT: Thank you!

CURWOOD: So how significant is the trash problem in Mexico City?

WAINWRIGHT: Well, it came to a head earlier this year when the city government shut down one of its biggest trash dumps which was just on the edge of the city. This was a huge place that, until recently, had been receiving thousands of tons of trash every single day – it was about the size of 450 football pitches – but they shut this down just towards the end of last year, and so around the beginning of this year, these great big heaps of trash started piling up around every corner of the city because the city authorities just didn’t know how to get rid of it. They’ve solved that problem for the time being, but there’s no doubt that unless they can change something fairly fundamental, the trash problem is going to continue in Mexico City.

The Mexican flag features an eagle gripping a snake in its beak while standing on a cactus, a nod to the founding of Mexico City. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: I understand that the government in Mexico City is offering people carrots, literally, to start recycling their trash. Can you tell me about that?

WAINWRIGHT: (Laughs). That’s right, they’ve got this new thing that they call a barter market which takes place in one of the parks in the center of town every month. And you go along with your recyclable trash – your glass, your metal, your paper, your plastic, all of this stuff ¬– and you hand it in, and in return they give you want they call green points, or green tokens. And with those tokens you can buy, as you say, vegetables, fruit, plants, all kinds of things, in return for your rubbish. So people are going along with their weekly household waste and going home with a bagful of vegetables to have for lunch.

CURWOOD: So how much food has been exchanged for trash, so far?

WAINWRIGHT: So far, they’ve got through about 140 tons worth of trash, which is a small proportion of the amount that the city produces everyday, but none-the-less, they’ve gotten rid of all of this rubbish and they’ve swapped it for about 60 tons of fruits and vegetables!

CURWOOD: And once the government has all of this trash, what do they do with it?

WAINWRIGHT: Well, here’s the interesting thing, their message, that the government is very keen to give people, is that what you think is trash isn’t necessarily worthless. And they put that idea into practice by selling all of this recyclable waste to companies that can convert it to new things.

So, for instance, the paper that they have they sell to companies that can mash it up and turn it into new paper, and they do the same thing with the glass and metal, and with all things they receive. And, so, every month they take about 20 tons of trash, and they sell this waste for about $3,000, which doesn’t completely cover the cost of the vegetables, but it goes quite a long way towards it.

CURWOOD: So you say they get about $3,000 for the recyclables, and it costs more for the food, how much more for the food, and how would that compare to the cost of having to gather this stuff up or find more landfill space?

WAINWRIGHT: The amount they spend each month on the food comes to almost double what they make in selling the rubbish. So every month they make about $3,000 from selling this recyclable trash and they spend about $6,000 on the fruits and vegetables, so the project is making a loss – it’s not intended to be a moneymaking project. But the government sees it as a sort of educational mission, they reckon that at the net cost of about $3,000 per month, that’s not too bad a price to pay for educating a city of 20 million about the importance of recycling their waste.

CURWOOD: Obviously the main purpose here is to encourage recycling, but this is a significant boost for local farmers, you observed.

WAINWRIGHT: Well, it is, yeah. In the south of Mexico City, there’s this fascinating neighborhood called Xochimilco, which looks a bit like the original city would have done hundreds of years ago before the conquistadors arrived. It’s a sort of network of canals –as you said in your introduction, Mexico City used to be an island in the middle of a lake and this part in the south of the city still resembles what the edge of the lake would have looked like hundreds of years ago.

You go down there and it’s a network of canals with floating man-made islands on which these farmers grow these vegetables. They make these islands by getting these old rotten boats, which are made to sink, and they fill them up with mud, dirt, and they grow vegetables in them.

CURWOOD: So, overall how do you think this program is working out so far? To what extent are people recycling and what about plans to possibly expand?

WAINWRIGHT: Well, I think it’s going pretty well. I went down there last month with a few old computer cables and things of my own which I swapped for some carrots and some broccoli, I think it was, and even early in the morning it was absolutely jam-packed.

People tell me that lines start forming first thing in the morning because people want to get there as early as possible to get the best fruits and vegetables that they can. Apparently, if you go early enough, they even have cheese. But I confess, I’ve never been able to get up on time to be there in time to get any cheese!

But it’s obviously been successful, it’s very, very full every month. So much so that they’re actually thinking about expanding the project – they’re actually talking about making this a fortnightly thing rather than a monthly one. So I think so far it’s been pretty successful. There’s a political question over it because in December, the new city government takes over, there’s a new mayor who is going to be taking over, so the future of the project will depend on what he makes of it. But given the popularity of the project, I think it’s likely we’re going to see it expanding even more.

CURWOOD: Tom Wainwright is a reporter for the Economist based in Mexico. Thanks so much, Tom!

WAINWRIGHT: No, Thank you!

Related link:

Tom Wainwright’s Economist Article

[MUSIC: Pat Metheny “Sueño Con Mexico” from Works (ECM Records 1984).]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – some old - and new ideas to solve the problem of paying for public transportation - Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ray Bryant: “Cold Turkey” from Cold Turkey (Capitol Records 1964).]

Power Shift - Prospering Public Transportation

Urban walkers (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. As more and more people move into walk-able city centers, public transit ridership is on the rise - and under stress.

Nowhere is the trend more stark than Boston, home of the nation’s first subway system.

[BACKGROUND NOISE, SUBWAY]

WOMAN: This morning I was on the 6:00am Heath Street train and there was a broken down car ahead of us and we had to get off of three different trains and back on, and everyone on the train was late for work. They did a lot of service cuts recently, I feel like they’re just short on people or something. I don’t know, but it’s definitely been way worse than what I’ve experienced in the past few years.

MAN: I actually waited last week for like a half an hour for a B-line train, I think. I saw a bunch of other trains go by and then mine came and it was so full that I had to wait for the next one. And then the next one came and that was even still full so I just squeezed my way on, shoved my way on.

CURWOOD: Despite the boom in ridership and a recent fare hike, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority is in deep financial trouble, with some routes strained to the breaking point. The combination of debt, operating deficits, long deferred maintenance, and growing ridership looks like an intractable problem, especially with governments' budgets squeezed.

But there is a way to finance operations and expansion that taps the profits that transit can bring to business, according to Christopher Leinberger, a George Washington University transportation researcher. He says - think of transit attached to walkable districts as a means of sustainable economic development that then helps pay the transit tab, and fights climate change.

LEINBERGER: Transportation, whether it be roads or rail transit, or bike lanes, have always been subsidized. The airlines have been around 100 years, and the net profit that those airlines have made in that 100 years, is zero, the few good years get offset by crushing losses. The question is – who pays? We have a situation where the federal government is not going to play its historic role funding a significant amount of mass transit, the state governments are in the same situation, so where does that money come from?

And I’m suggesting, and Locus is suggesting, and a lot of developers are suggesting that we need to learn from how we used to build our transit systems 100 years ago. This country 100 years ago had the finest rail transit system on the planet. And the vast majority of it was paid for by real estate developers, and it’s not as if the economics were different then than now – those rail transit systems, those trollies, those subways in New York, lost money. So why did developers build them?

They built them to get their customers out to their land, so land profits subsidized the transit, and that’s what we’re proposing with value capture as well. Value capture is capturing the value that’s created by transportation improvements. And it’s not as if you can just assume that developers are just going to pay for it all, that’s not going to happen. Think of it as a layer cake of different financing sources.

Some is going to be from the federal government, some is going to be from the state government, and some will be from the developers that will commit a portion of their profits, a portion of their up-sides that pay off the bonds that build those transit systems.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, how could this concept of value capture work for existing transit systems? Consider Boston for example, the fare box just pays for the debt, but businesses have been getting the MBTA for free, so why would they now want to pay?

LEINBERGER: Because they could get increased density, possibly. So that you could go to the existing property owners and say, ‘we will zone a higher density for you. In exchange, we want a piece of that upside to help pay for either the operations of or the capital improvements of the rail system.’

CURWOOD: Let’s focus for a moment more on new transit systems – how does value capture work exactly for those new routes of mass transit?

LEINBERGER: With a new system, such as the new line that’s going out to Tyson’s Corner in northern Virginia from downtown DC, about a third of that cost is being paid for by the property owners at Tyson’s. Tyson’s, 25 years ago, led the market in DC, the highest rents, the highest absorption, they were the king of the hill. Today, they’re near the bottom, and that’s because the market wants more walkable, urban, higher-density places.

So, the Tyson’s developers, very intelligently, said they have to bring metro out to Tyson’s. And so they taxed themselves to pay for about a third of the cost of that very expensive rail system. Another way is the New York Ave. metro station in DC, a bunch of developers got together and said: We’d like to build a station, and we so need this station that we’re willing to pony up, again, about a third of the cost, and they put the money upfront.

And I’ve talked to one of them recently and he says it’s the best investment he’s ever made because money in that metro station increased the value of his land so much that he made a phenomenal return on that investment.

The Washington DC tube (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: What about Boston? Boston wants to extend its green line out from the Lechmere area out to Somerville. How could value capture work for that new route?

LEINBERGER: Well, there’s a number of new developments that are being proposed along that green line, and there are some very substantial developers that are proposing it. They too could help pay for the stations and they could also cut a deal with the MBTA to maybe share a piece of their financial upsides to help pay for the operations.

Because, with transit, you’ve got both the issue of capital costs and operating costs – most systems, the operating costs are not even covered by the fare box and then you have to find separate sources of funding to pay for the capital costs, and that’s just the way it is, so we have to deal with that.

CURWOOD: What’s the formula for having this economic success. If you bring a transit line to a certain place, what needs to be there to get the development that you say, and how critical is walkability?

LEINBERGER: Walkability is driving this. Walkable urban places have a significant price premium over drivable suburban, and so much so that the variability in economic performance, about 2/3s of it is explained by how walkable it is. It’s a major economic driver. The other two, by the way, happen to be job density and work force education level, how many people have their college degrees. That explains over 90 percent of the reason why these walk-able urban places perform so well economically.

A passenger waits for the T in Boston (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: How does Boston move forward? What do you recommend?

LEINBERGER: Think of it as a baseball team. Think of it as the Boston Red Sox. And the infielders are the walkable urban places, whether they be in the suburbs or the city. The outfielders are the 128 drivable suburban places. They’re both important, but you have pent up demand for more walkable urban places and the market wants a lot of those to be in the suburbs.

The center city is growing and the suburbs are not just not growing, they may be shrinking. The market would love to have those nodes of energy out in the suburbs as well, and right now, in Boston, it’s illegal to build high-density walkable urban places around your subway stations and around your commuter rail lines. And oh, by the way, I believe walkable urbanism, the building of great walkable places, will be the number one way we’re going to address climate change.

You may remember, two years ago in Washington, it was legal to talk about climate change, but 99 percent of the discussion was about supply efficiency. Very important topic, as far as renewables, as far as increased efficiency of our cars, but the other side is demand mitigation ¬– providing places to live that by their very nature do not require the burning of fossil fuels. We’ve known for a long time that of climate change gases, about 75 percent of them are generated by either buildings or the transportation systems we use to get between our buildings. More research needs to be done to confirm this.

But if you move a drivable suburban household out there on the fringes of Boston, into Cambridge, and they move into a townhouse or into a condo, you will reduce their household energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions by about 50 and 75 percent. So with that huge reduction in the built environment, this could conceivably be the number one way we are going to address climate change.

CURWOOD: Christopher Leinberger is a professor at George Washington University, and President of Locus, part of smart growth development. Thank you so much, sir.

LEINBERGER: Thank you.

Related links:

- More about Chris Leinberger

- Dukakis Center for Urban and Regional Policy

- Smart Growth America

[MUSIC: The Meters “Just Kissed My Baby” from Rejuvenation (Atlantic Records 1974).]

CUTWOOD: Just ahead - how function creates form - at least among lizards - but first this note on emerging science from Annabelle Ford.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Science Note: Mantis Shrimp

The peacock mantis shrimp hides away on the ocean floor. (Photo Aziz T. Saltik)

FORD: The peacock mantis shrimp can grow up to 7 inches and is brightly polka-dotted. And while the shrimp doesn’t seem particularly intimidating, researchers have discovered that it packs a surprising punch.

Scientists at the University of California Riverside clocked the speed of the shrimp’s bright orange club-like arm at 50 mph underwater. That’s the fastest punch for any living animal on record. It can crush its prey with a force greater than 1,000 times its own weight and break through exoskeletons of crabs and other crustaceans known for their impact resistant shells.

The brightly colored peacock mantis shrimp and its bright orange arms, which throw the fastest recorded punch of any living animal. (Photo: Silke Baron,)

The super strong shrimp even needs to be housed in special quarters in the lab, since its fist could break through a standard aquarium tank!

The key to the peacock mantis shrimp’s power is three-fold. The arm’s top layer is composed of high mineral concentration, and is reinforced by a shock-absorbing web of fibers underneath. A third layer of fibers encapsulates the entire club, keeping it intact during hits. These layers create an incredibly strong, resilient and lightweight weapon.

Researchers plan on copying the shrimp’s design to improve military armor. Soldiers currently lug about 30 pounds of protective equipment with them. Scientists hope to reduce that weight by 2/3rds and increase the gear’s durability.

Peacock Mantis Shrimp (Photo: Jenny Huang)

It’s said that size doesn’t matter: well the peacock mantis shrimp is living proof that a small arm can bring big changes to a weighty problem.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science, I’m Annabelle Ford.

Related links:

- University of California at Riverside article about the Mantis shrimp

- More about Prof. David Kisailus

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Tricky Lizards

An Anole Lizard, partially hidden behind a leaf. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: One of the most powerful pieces of evidence that helped Charles Darwin formulate his theory of evolution was the way species changed when isolated on different islands. In Darwin's case, it was finches - but as Ari Daniel Shapiro reports, the same kinds of changes can be found among species of lizards in different parts of the Americas.

SHAPIRO: Rosario Castañeda can’t get her 1‐gallon jar to open.

Do you want me to help?

CASTAÑEDA: Yeah, please.

SHAPIRO: The lid won’t budge. Oh, boy... Until finally

[SOUND OF LID POPPING OPEN]

SHAPIRO: The jar’s brimming with ethanol. And submerged in that preservative are half a dozen lizards the size of turkey basters. They’re called anoles. And in this story, we’re going to use anoles to talk about eco‐morphology – that is, the relationship between how organisms use their environment and the way their bodies have evolved.

CASTAÑEDA: Let’s get one of these out.

[SOUND OF FORCEPS AGAINST GLASS]

SHAPIRO: Castañeda – an evolutionary biologist here at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology – uses a pair of long tweezers to pull an anole out of the ethanol. She has the preserved anole by the belly. The lizard’s a dark chocolate brown. It came all the way from Cuba, where it lived up in the forest canopy.

CASTAÑEDA: They can actually move into, like, really small branches proportional to their body size. The other thing is that they have these really large heads. They eat larger prey and harder prey as well.

SHAPIRO: Like what?

CASTAÑEDA: Beetles, things that are a little bit crunchier.

SHAPIRO: This anole belongs to a species called Anolis equestris

[JAR NOISES]

SHAPIRO: Then Castañeda pops open a much smaller jar, which contains Anolis occultus, from Puerto Rico. It’s tiny – about the size of a twig. Which is no coincidence. Occultus lives on small twigs, and they’re masters of camouflage.

CASTAÑEDA: Like when you see them in the field, you have to look really hard to make sure that this is not a twig. And they stay still so perfectly that you’d have to wait to see them move and really realize there’s a lizard there.

[SOUNDS OF SHELVES MOVING]

The profile of an Anole Lizard. (Bigstockphoto.com)

SHAPIRO: Castañeda leads me into the anole collection at the museum. The shelves are filled with jars of anoles of all shapes and sizes. Many of these specimens come from the Caribbean where you find not just big anoles like equestris in the forest canopy and little ones like occultus clinging to tree twigs, but also mid‐sized ones living only on the trunks of trees, and others that split their time, scuttling between the base of the trunk and the forest floor and nowhere else.

CASTAÑEDA: So you have a huge diversity in what would look at the beginning as a single habitat.

SHAPIRO: Namely, a single tree. But for an anole, a tree’s made up of half a dozen different micro‐habitats, and the various types of anoles have adapted accordingly, over and over again. Take the big anoles. They scamper about the forest canopies on all the Caribbean islands – Cuba, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Hispaniola – but they’re not the same anole.

Each island has a different species of big anole up in the canopy. And each island has a different species of little anole on the twigs. And so on. The anoles have repeatedly evolved in more or less the same way throughout the Caribbean, on every island. It’s an example of eco‐ morphology. Again, that’s where a variety of habitats reliably produce the same spectrum of body shapes.

Castañeda studies anoles in South America. She’s looking for a pattern, maybe one that’s similar to the Caribbean. The first step was establishing who’s related to who. So she set out to collect anole DNA. She always collected at night. Unlike in the Caribbean where you can’t help but see lizards.

CASTAÑEDA: Lizards everywhere.

SHAPIRO: In South America, there are far fewer.

CASTAÑEDA: During the day, you will hardly see them. So it would be easier to go at night because at night they sleep over leaves. So when you flash them with the light, they look whitish over the background of the green leaf.

SHAPIRO: Then she moves a little loop on the end of a fishing rod into position.

CASTAÑEDA: Then you’ll pass the loop around the head of the lizard, then you’ll grab your lizard.

SHAPIRO: Through the DNA work, Castañeda’s found that within each species of anole in South America, there can be a lot of physical variation.

CASTAÑEDA: Variations in size, the number of scales, and coloration.

SHAPIRO: Now she’s moved on to measuring the anoles – the length of their bodies and their legs, for example. She’ll try to match those characteristics with their habitats and see if there’s any evidence for eco‐morphology. But already things look different than the Caribbean. She’s found South American anoles living near water, or on boulders and rocks – and they don’t match anything that’s been reported before. Even the ones living in the trees look different.

CASTAÑEDA: Species that you would expect would have longer tails, they have shorter tails, or things like that.

SHAPIRO: Any one of a number of reasons could have steered anole evolution in a different direction on the South American mainland. Maybe the snakes and birds snacking on the anoles attack differently. Or maybe the habitats are just plain different. Castañeda spends half her time working her way through this puzzle.

The rest of the time she earns her keep as a fellow for the Encyclopedia of Life – a website that devotes a separate webpage to every creature on the planet. And it supports this series, by the way. Castañeda’s in charge of the anole pages.

CASTAÑEDA: The idea is to get people to compile high quality data on species. So you know that whatever you’re reading on Encylcopedia of Life, somebody that really knows about the topic is writing that.

SHAPIRO: Castañeda is working on all the anole species.

CASTAÑEDA: There’re roughly 385 species.

SHAPIRO: As for how many she’s done?

CASTAÑEDA: Complete? Like, 5 at this point.

SHAPIRO: Only 380 jars to go.

[MORE JAR NOISES]

SHAPIRO: For Living on Earth, I’m Ari Daniel Shapiro.

[MUSIC: David Crosby “Cowboy Movie” from if I Could Only remember My Name (Atlantic Records 1971).]

CURWOOD: Our story about the Anoles was reported by Ari Daniel Shapiro for the series “One Species at a Time.” It’s produced by Atlantic Public Media, with support from The Encyclopedia of Life. Check out the pictures at our website loe dot org.

Related link:

One Species at a Time- Anoles

CURWOOD: Coming up – some stellar words of advice for President Obama in his second term - from Neil deGrasse Tyson. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Johnny Otis: “Cold Turkey” from The Capitols Years (Capitol Records 1989).]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Superman of Astrophysics

(Wikimedia Creative Commons)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[SOUNDS FROM OLD SUPERMAN VIDEO – “FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET – MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE – ABLE TO JUMP TALL BUILDINGS AT A SINGLE BOUND”– “LOOK! IT’S A BIRD!” – “IT’S A PLANE!” – “NO – IT’S SUPERMAN!”]

CURWOOD: Well, it's not actually Superman – but it is super astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson.

TYSON: (laughs) I don't stop and jump tall buildings, I take the elevator.

CURWOOD: Neil deGrasse Tyson is Director of the Hayden planetarium in New York City and now a comic book character.

TYSON: Well, what happened was DC comics called up, they wanted one of their installments to involve Superman visiting the Hayden planetarium. So, ostensibly all they really wanted was permission to represent the museum and the planetarium in the comic, and then from there it kind of grew.

They said: Can we draw you showing him his home star on the dome? You know, this is Superman, right, so you’ve got to say yes to that. Had it been Aquaman, or Elastic Man, no! It’s gotta be Superman (Laughs.)

CURWOOD: Not even Spiderman, huh?

TYSON: Maybe Spiderman. But, you’ve gotta rank your super heroes in this regard, otherwise how would you allocate your time in any sense of the word.

CURWOOD: But, Superman’s home planet, which is Krypton, it blows up as he’s flying away as a baby, so how is he going to see it blow up from the Hayden planetarium?

TYSON: This is where the plot thickens. As the story tells it, he has come every year to the Hayden planetarium to look at his planet Krypton orbiting his host star. Now, the only way that can happen is if he arrived through a wormhole. So, remember, he’s launched as a baby in a basket, kind of Moses-style, and then he arrives as a baby. So, in his life, hardly any time had elapsed.

Now, the only way to get him here sooner than the edge of light that’s carrying the information that Krypton exploded would be to get him here in a wormhole. So, every year he’s been observing Krypton except this one particular occasion, where it’s about 27 years later and he’s in his late 20s, and when he was born Krypton was destroyed, so this particular visit to the Hayden planetarium, he’s in for a sad moment.

CURWOOD: And, that moment of course being…

TYSON: Spoiler alert here: he observes the destruction of Krypton. So, if it was only… I help them observe this for this melancholy moment, then it’s just they’re representing me with my vest, my trademark vest, and all this, that’s kind of cool. However, it was more than that, I said: I could probably find a real star that’s 27 light years away that’s red just like Superman’s home star, so let me comb the catalogs, as I did. Found them a star!

It’s official title is LHS 2520, if you’re taking notes, and it’s in the constellation Corvis, that’s Latin for crow, visible from the Southern Hemisphere. And not only that, those of you who are Superman aficionados will know that in Smallville, his High School mascot was the crow. So, you combine all this together and it makes for this, not only interesting sort of sad chapter in Superman’s life. But there’s some science, actual science infused in that storytelling, and I was delighted to actually be able to assist them in this effort.

CURWOOD: So, let me just review the science. The hypothesis here is that Superman as a baby travels through a worm-hole which goes much faster than the speed of light, but to see his natal planet, ordinary light is what he uses, so it’s 27 light years away. And that means that by the time he’s 27, he gets to see it blow up.

TYSON: Exactly. It turns out we don’t know how to observe planets in that detail using visible light, so you need a kind of mondo-interferometer, where you combine many different telescopes across the width of the Earth, which then enables the width of the Earth to act like it is a single telescope dish that is that size.

Neil deGrasse Tyson in his trademark vest. Dr. Tyson is director of the Haden Planetarium in New York. (Photo: Neil deGrasse Tyson)

And when you have a telescope technique that’s using that technique it’s called interferometry, and by the way, they use that word in the comic – I was like: ooh, so cool. Using actual astrophysics terminology there - and so when you combine the telescopes that way, which we don’t really know how to do yet, you can get an image, high enough resolution to watch Krypton destroyed. So, Superman, uses… he, like, stares at the computer and his superpowers help the computer calculate this image, and so it’s another invocation of his powers in order to tell this story.

What I didn’t know is that several episodes a year, DC Comics introduces key personal elements in Superman’s life that are worthy of press releases, and this was one such episode. It’s Action Comics #14.

CURWOOD: Action Comics #14. To see super astrophysicist Neil de Grasse Tyson and Superman together…

TYSON: And I’ve gotta tell you, I spoke to the illustrator, and I said: You know if it makes no difference, if it doesn’t matter, could you like trim a few pounds off my waist? If it’s no difference to you? And they said: Dr. Tyson, this is the comics, everybody looks good. (Laughs.) So I come out from the back room, rolling up my sleeves, looking buff, so that was cool.

CURWOOD: Now, there are some other developments in space…

TYSON: There always are!

CURWOOD: Yeah, that I wanted to ask you about. And there’s something that I’d never heard of… a rogue planet?

TYSON: Oh yeah! Oh, you’ve never heard about the rogue planets? Well, we didn’t even think to think of these things until our models of the formation of the solar system showed us that if you start out with a star and a collapsing gas cloud making surrounding planets, you can make planets in all kinds of places in orbit around the host star, but not all of those places are orbitally stable.

And what we found was the solar system itself might have started with two, three dozen planets, and depending on where their orbits are relative to other planets, they might not maintain a stable, forever, orbit around their host star, and they can end up getting flung into interstellar space. And when this happens, they become rogue planets. Homeless planets. And what makes it interesting is some planets still have heat left over from when they formed.

Jupiter still has heat left over. Actually, it’s generating heat because it’s slowly collapsing so it radiates more heat than it receives from the sun. And of course Earth has all this heat from its geologic activity, we’ve got this magma sitting below the crust and all of this volcanic activity… that heat, that energy is not traceable to the sun. That’s born here on Earth. So you could imagine flinging a planet out into interstellar space, and still have energy there that could possibly sustain life.

So it’s been hypothesized that most life in the universe is found on rogue planets, where they don’t need a star. And we’re pretty sure that there are more rogue planets than planets that are in happy, stable orbits around host stars.

CURWOOD: What if they’re headed this way?

TYSON: Sure, but space is really empty, and so you worry that one is going to be on a collision course with Earth, I suppose, in principle that’s possible. But the sun’s gravity and Jupiter’s gravity is so much greater than Earth’s gravity that they are going to do most of the redirecting of what comes near our solar system. So we have our big brother protectors out there in the schoolyard.

CURWOOD: Make sure those rogue planets don’t mess with us!

TYSON: (Laughs.) That’s right… the bully planets coming through.

CURWOOD: Now, there’s something else out there that has astrophysicists excited. There’s a super hot gas cloud headed for a black hole – what does that mean and what’s likely to happen?

TYSON: Well, black holes are only rendered visible in the galaxy and the rest of the universe… because they’re black right, so how do you even know they’re there. And one way we detect them is they dine upon anything that comes too close – it could be gas clouds, it could be entire stars.

In fact, one of the classic ways to detect a black hole is the black hole used to be a star, a full red-blooded star that died, and the black hole is its death state, and it was in orbit around another star which is still alive. And stars in their later stages get big and fat, they become red giants, and their outer layers would then become flayed by the black hole that’s in orbit around it. Then it’s the descent of this gas down to the center of the black hole that ends up getting heated and radiates profusely at very high temperatures, so high that it’s radiating ultraviolet and x-rays.

And so the very first black holes ever discovered, were discovered with x-ray telescopes. It’s a whole different window to what’s going on in the universe, when you put on x-ray eyes. So if you know in advance that a gas cloud is approaching a black hole, then get ready for the fireworks, because it’s going to be a scrumptious meal for the black hole that is soon to come.

CURWOOD: Tell me more about this black hole. Isn’t this now in the Milky Way, and if so, what might we be able to see?

TYSON: What we’re bracing for is at the point a black hole eats anything, typically it is revealed by what this stuff does, whatever be the material, whether it’s a gas cloud or an entire star. As it descends into the black hole, it becomes ferociously hot before it crosses over into the event horizon where it’s gone forever. But just before that, the act of descending into the black hole generates heat and that heat renders the material visible to an x-ray and ultraviolet telescope. So what you get ready to do is prepare your x-ray telescopes, line them up and just watch the fireworks unfold.

CURWOOD: We won’t be able to see anything from our back porch, huh?

TYSON: Oh, you want to be able to see a black hole eat something from your back porch? I’m sorry, I can’t help you there. (laughs)

CURWOOD: Um, I want to bring you a little closer to Earth here, Neil deGrasse Tyson, in the wake of superstorm Sandy a lot of people were so impressed by the accuracy of the satellite projections, being able to see the storm and the path nine days in advance, but I understand the satellite we relied on in that storm was actually a backup! What’s going on with the satellite fleet that’s up there… it seems to be aging!

TYSON: Yeah, so they’re aging. A lot of the satellites were launched in the… sort of conceived and then launched in the 70s, 80s and 90s. Satellites don’t live forever, so there’s the natural life cycle of satellites, that’s not what the concern is. The concern is if the satellites go through their life cycle and you don’t have ones to replace them, then what started out as this major effort to monitor the various atmospheric and oceanic conditions on Earth so you can create accurate weather prediction models, if you’re not replacing them at the rate that they were first put up there, then your capacity to monitor Earth fades.

So there’s an interesting sort of impasse here. Everyone thinks of NASA, as: These are the people who go into space. And we think of orbiting Earth as space, and so therefore weather satellites are the purview of NASA. Well, I kind of view the world differently. I think NASA should be the agency that expands a space frontier. Right? Go some place tomorrow that we haven’t been today. That’s, I think, what NASA should be. And you have other agencies like NOAA, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, which they’re tasked with monitoring the Earth. All they do now is get the data from these NASA-launched weather satellites, but maybe a whole organization should be tuned and tooled just for this purpose.

And that way you can let NASA continue to expand the space frontier, re-trick out NOAA, which would be very hard to do at this point because that’s not what they do, they don’t have labs, they don’t have designers and engineers to do this. But if you did, then you’d have an entire agency whose task it is, is to monitor Earth. And maybe we’re long overdue for that. And then they’ll say: Yeah, we need more satellites! And you wouldn’t be competing the funding for an Earth satellite with a Mars rover, they’d be separate concerns, which in fact, they are.

CURWOOD: So the problem has been this financial competition and now, NASA being a place of exploratory science, they have not been willing to make enough noise to make sure that the weather satellites are replaced ¬– is that what you’re telling me?

TYSON: Yeah. I mean, there are many things competing for money in the limited budget of NASA’s portfolio. So if you want NASA to do it, then fund it at that level. This is not a hard problem to solve. But if you’re not going to fund it at that level, then Peter is getting robbed to pay Paul. By the way, it’s not just ‘how good is your picture from the satellite that’s moving from one municipality to the next,’ it’s ‘what are the surface temperatures of the land and the ocean,’ and ‘observe the Earth in infrared, invisible light and these other bands where Earth might be trying to tell you something.’

And if you’re missing that branch of data, then your model then cannot be correct because the model may depend on this. Then there’s the heating from the sun – is it reflecting off the clouds, is it returning to the Earth, is it being trapped by your carbon dioxide? What’s reflected back from the glaciers? How much glaciers do you have left? It’s a hugely complex problem and you need as many satellites up there as you possibly can. And we have less money being spent on weather satellites today than we did 20 years ago, so that’s a problem.

CURWOOD: So, Neil deGrasse Tyson, President Obama, of course, got a second term. So what do you think that might mean for space funding, for NASA funding going ahead?

TYSON: Yeah, I don’t know for sure, I haven’t seen an official document, but I know there’s pressure on him to actually go back to the damn moon! Excuse my language! What he did in his first term and I was at his speech and it sounded great and everybody applauded it, until you reflect on the consequences of it.

What he said was: We don’t need to go back to the moon, we’ve been there already. Let’s set our sights further away. Let’s go to Mars, let’s go to asteroids. This is the first time I’d ever heard a president speak at that length about deep space, so it sounded great, it sounded visionary. And then I thought about it and I said, well, wait a minute, we have thousands of people, engineers, planning on going to the moon, building spacecraft to enable this. So, what happens to them? Well, they lose their jobs – they lost their jobs.

And so I kind of want to demonstrate again that we know how to get there. It’s been 40 years since we’ve been to the moon. You can get there in three days, right? It makes a nice media cycle, we can like track them as they go– how’s it going and what music are you listening to? And that becomes a very sellable trip, I think, to the American people.

That way you reinvigorate a near-term space plan. This: Oh, well, let’s go to Mars… when? In the 2030s. Well, excuse me, that’s like under the leadership of a President to be named later, under a budget not yet established. So I’m concerned when a President promises something that they never actually have to shepherd… have a nice day! (Laughs.)

CURWOOD: (Laughs.)

TYSON: (Laughs.) You know, I’m just saying! We live in a free country and you vote for who you want, I’m not going to tell you who to vote for, but I will tell you the consequences of certain actions or inactions that are in progress, and the country belongs to We the People, last I checked. To say, what’s Obama going to do, it’s what are WE going to do? He works for us! Congress works for us!

So I don’t have the attitude, I wonder if this leader will take us back into space – if you want to go back into space, vote that way. Create the imperative that law-makers must then follow, otherwise they simply get voted out of power.

CURWOOD: Neil deGrasse Tyson is Director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York. And his latest work is a DVD entitled the Inexplicable Universe, part of the Great Courses. Thanks so much for being on the show, Neil.

TYSON: Thanks for having me. By the way, if you are interested I also tweet the universe. They're really more like cosmic brain droppings but if you're interested I tweet at Neil Tyson so check it out if you have nothing better to do with the free time of your day.

CURWOOD: Alright, we're all a twitter. (Laughs)

Related links:

- Hayden Planetarium: More about Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Neil deGrasse Tyson on Twitter

[MUSIC: Echo And The Bunnymen “Super Mellow Man” from B Sides and Live (2001-2005).]

A Visual Feast

A sunset in the north woods of Wisconsin (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Before this year's Thanksgiving with its groaning tables and groaning stomachs has disappeared over the memory horizon - we offer this short poem from writer Rod Clarke. Among all his festive preparations - he turned his attention - not to food - but to the horizon over his Wisconsin farmhouse.

CLARKE: So I asked the guy down at the sunset shop:

“What do you have in a soft evening cranberry?

We need it for the walk in the woods

twixt pie and gravy blessed bird.”

And he said: “Sorry sir, we’re out of that—

but what would you say to a tangerine sun

plunging through pale pumpkin skies

to the dark meat of the hills?”

CURWOOD: Rod Clark lives and writes on a small farm in Cambridge, Wisconsin.

He’s editor and publisher of Rosebud Magazine.

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “Poem For Eva” from Good Dog, Happy Man (Nonesuch Records 2000).]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth… simple energy-saving options are being introduced on college campuses:

RANAHAN: We've saved the university millions and millions of dollars. Millions and millions of kilowatt hours, therms of gas and carbon emissions.

CURWOOD: How LED lights - easy transit and passive solar buildings - are paying off - that's next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC CONTINUES]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald , Helen Palmer, Annie Sneed, James Curwood, Meghan Miner, and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at just eat organic dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Go Forward Fund and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax World dot com. Pax World, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth