April 26, 2013

Air Date: April 26, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

EPA Finds Keystone Environmental Impact Statement “Insufficient”

View the page for this story

The EPA has written to the State Department, criticizing its draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Keystone XL oil pipeline. UCLA law professor Ann Carlson joins host Steve Curwood to discuss the criticisms in detail and explain how this might impact the Keystone decision. (05:15)

Preaching for Keystone

View the page for this story

TransCanada, the company planning to build Keystone XL, needs permission from land owners for the pipeline to cross their property. Company land agents across rural Nebraska are trying to get landowners to sign on the dotted line, but one agent has attracted controversy because he's also a Baptist preacher. Nebraska farmer Terry Van Housen talks to Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about his experience with the preacher land agent. (05:15)

Pipeline Proselytizing and Eminent Domain

View the page for this story

On Earth editor at large Ted Genoways tells host Steve Curwood that if the Baptist preacher can’t convince residents to sign a land easement, the possibility of taking the land by eminent domain might. (04:15)

Deepwater Disaster Three Years On

/ David LevinView the page for this story

Just three years ago, the DeepWater Horizon oil spill gushed 200 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Reporter David Levin from Mind Open Media reports on a team of chemists, engineers, and biologists that is attempting to assess the overall damage to the Gulf ecosystem. (08:55)

Low Cost Renewable Energy Storage With Hydrogen

View the page for this story

The problem of storing energy from renewable sources is a great limitation of alternative energy technology. The solutions are either inefficient or unaffordable. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Curtis Berlinguette from the University of Calgary about his team's research into a more affordable and efficient mechanism to store renewable power. (06:15)

BIRDNOTE®/SPRING RAINS REFRESH THE DESERT

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Every spring, the rain brings bird songs back to the California desert. Michael Stein has this week’s Birdnote®. (01:55)

.jpg)

Old Whales Learn New Tricks

View the page for this story

A new study in Science magazines claims that whales in the Gulf of Maine have learned a novel feeding behavior from each other through a form of cultural transmission. Study author Luke Rendell, lecturer in biology at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, tells host Steve Curwood about the emergence of and reason for this behavior. (07:30)

Joe’s Pond Ice Out Contest

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Every spring, Central Vermonters flock to general stores to buy tickets to the Joe’s Pond Ice Out Contest. If they can correctly guess when a flag will fall through the frozen pond, they’ll go down in the history books, and win a decent chunk of change. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports from West Danville, Vermont. (07:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood,

Guests: Ann Carlson, Terry Van Housen, Ted Genoways, Curtis Berlinguette

Reporters: Bobby Bascomb, David Levin, Michael Stein, Emmett FitzGerald

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The EPA finds fault with the State Department's environmental assessment of the Keystone XL pipeline - and that might affect final project approval.

CARLSON: It's a political decision, it's a symbolic decision, it's an economic decision and the Environmental Protection agency's letter I think is going to provide good legal and good political arguments about why the pipeline decision ought to be no.

CURWOOD: Also, where folks find inspiration to pick a date for the official ice-melt at Joe's Pond in Vermont.

LARABEE: It’s birthdays, anniversaries, lucky numbers. Sometimes we have the dowsers come in and they’ll dowse with a pendulum over a calendar. You know it’s just one of those things, whatever floats their boat.

CURWOOD: And there's a sweet prize if they win. We'll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

EPA Finds Keystone Environmental Impact Statement “Insufficient”

Ann Carlson (photo: University of California at Los Angeles)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Some say the proposed Keystone XL pipeline to bring tar sands crude from Canada would unleash climate disaster - others claim it would provide jobs and energy security. The US State Department has released a draft Environmental Impact Statement that favors the project. But now the US Environmental Protection Agency is calling the State Department analysis "insufficient," saying it downplays the pipeline's likely hazards. UCLA law professor Ann Carlson says the EPA challenges the State Department on a number of key points.

CARLSON: They really have three objections, but I would say one is the key objection and really, really important. And that is, in the draft Environmental Impact Statement, the State Department concluded that the greenhouse gas emissions impact of building the pipeline would not be significant, and that’s not because the extraction of the tar sands that would then be exported through the United States through the pipeline aren’t extremely greenhouse gas intensive, they are. In fact, they are much more intensive than traditional crude oil. The conclusion of the State Department is that if we don't build the pipeline, the oil’s going to get used anyway, and it will be either shipped by train or shipped through another pipeline, perhaps that goes to British Colombia and then is shipped to China. And so their conclusion is, no matter what we do, those emissions are going to be emitted. The Environmental Protection Agency is not so sure about that, in large part because there are estimates that suggest that if you don't have the pipeline the transportation costs of shipping the oil probably by rail are sufficiently higher or could be sufficiently higher then it might make the oil too expensive to actually extract in the first place.

CURWOOD: And what are the other two things the EPA objected to?

CARLSON: The second objection is that the possibility of a spill as a result of the building of the pipeline could result in the release of the kind of oil that’s being shipped that’s particularly environmentally damaging, and that more analysis and attention should be paid to try to minimize those risks. The third problem the EPA identifies is that the State Department hasn’t adequately addressed an alternative route that would avoid going over some of the land in Nebraska that is particularly sensitive and has an important aquifer underneath.

CURWOOD: So how important is the EPA's opinion here? How much of an impact can they have on this decision?

CARLSON: I think the Environmental Protection Agency's opinion is extremely important for two reasons. Most important reason is that the leader of environmental issues in the Obama administration is now saying that the conclusion of the draft Environmental Impact Statement from the State Department is inadequate in the most important respect, and that is their conclusion that the pipeline would not have a significant effect on greenhouse gas emissions - either wrong or ignoring important information. So as a political matter I think it's extremely important. It's also important legally because the State Department is going to have to change its Environmental Impact Statement - remember this is the draft - to address the concerns of Environmental Protection Agency or it’s going to face a lawsuit suggesting that the Environmental Impact Statement is inadequate with very good support from the Environmental Protection Agency agreeing with that assessment.

CURWOOD: So with all these questions being raised, what do you think the timeline is on the Keystone XL pipeline decision?

CARLSON: I am not certain that this EPA letter significantly slows down the decision-making process because I suspect - although I don't know for certain - that the State Department already has some of this information at its fingertips. The question is now incorporating it into the final Impact Statement. So I think the much more important question is actually not on time; it’s on substance. What is the State Department going to do in response to these criticisms from the Environmental Protection Agency? Will it change the department’s bottom line conclusion that the building of the pipeline does not have a significant environmental impact?

CURWOOD: The Keystone debate is really heating up. On Earth Day, for example, critics gathered over million comments opposing the project. Where do you think this thing might wind up?

CARLSON: Well, I think at the end of the day, this really is a political decision. President Obama made clear in the state of the union that he wanted to do something, as much as he could on climate change to try to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. If he wants to show the world that he’s serious about that, I'm not sure that approving a pipeline that has the potential, at least, to significantly increase greenhouse gas emissions is the symbol he wants to send the rest of the world. It’s a political decision, it’s a symbolic decision, it’s an economic decision, and the Environmental Protection Agency’s letter I think is going to provide good legal and good political arguments about why the pipeline decision ought to be no.

CURWOOD: Law Professor Ann Carlson is Director of the Emmett Center on Climate Change and the Environment at UCLA. Thanks for joining us.

CARLSON: Thank you. It was a pleasure to talk to you.

Related links:

- EPA letter

- State Department Draft Environmental Impact Study

- Ann Carlson faculty page at UCLA

Preaching for Keystone

If approved, the Keystone XL pipeline will pass through rural farmland. (photo: Bigstockphotos.com)

CURWOOD: TransCanada's pipeline would cross thousands of parcels of private land. So the company has sent agents to win permission from landowners. One land agent in rural Nebraska has attracted controversy because Myron Stafford is also a part-time Baptist preacher, and some folks aren't sure about a preacher proselytizing for a pipeline. Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb got one of them on the phone.

VAN HOUSEN: My name is Terry Van Housen and I'm a farmer from Nebraska. My main operation is feeding cattle. I feed 10,000 heads. I’ve been farming for 45 years.

BASCOMB: Can you tell me about your experience with Myron Stafford? I understand he came out there to talk to you about Keystone?

VAN HOUSEN: Myron called me one day and wanted to set up a meeting about running a pipeline across my land. So I met with him. We went back into the break room so it wasn’t so noisy. We started talking about what they wanted to do with my land. We started talking about that...and then the conversation got switched into...he said that he was a Baptist preacher for three and a half years up at Polk, a little town five miles from my office. And he went on to say that he married people up there, and he buried some of my friends, and that he thought that God sent him there because it’s such a nice area. And to me, I just felt like he was trying to gain my trust to get me to sign the agreement to TransCanada to bury that pipeline across my land. So right then and there that kind of threw a red flag up for me.

BASCOMB: So he came to you as an employee of Keystone, but he’s also a preacher of a local church. What did you think of his two roles?

VAN HOUSEN: I thought it was a little odd that he was bringing so much of God into our business because in the conversation he said that he would never bring work into a house of God. But he sure brought God into my house of work.

BASCOMB: How did you resolve that conversation with him?

VAN HOUSEN: Well at the end of the first meeting, I had six questions for him that he could not answer. So he answered them the second meeting, plus I told him on the first meeting that you should be able to freshen up the price a little bit - a lifetime easement for Keystone XL and only a one time payment for me. So, the second meeting come around, he answered the six questions, he sweetened up the pot a little bit - there was a little more money he added - and I left it with him that I will think about it and then we’ll talk about it again. And he reminded me that after the 22nd that his offer goes off the board. In other words, you better make up your mind, get on board, or you’re going to end up with nothing. That didn’t really trick my trigger either.

BASCOMB: Can I ask you, how sweet was that pot?

VAN HOUSEN: It’s a 50 foot swath through my field, six foot deep, and for a lifetime easement, it was like $27,000. And he sweetened it up to $30,000. I got to thinking about that. I said, “You’re going to be making millions of dollars. There’s over $50 million dollars worth of crude oil going through that every day, and he’s offering me a measly $30,000 for a lifetime easement.” I don’t want it anyway. If he freshens it up a lot more, I still don’t want it because I found all the danger of that pipeline - what it could do to our nice clean water.

BASCOMB: Before you met Mr. Stafford, did you have any opinions about the Keystone Pipeline? How familiar were you with it?

VAN HOUSEN: I was very not familiar. And then Valentine’s Day, me and some friends were going out, and one of my friends, she was talking about the pipeline. And I said, “yes, that’s going across my land.” And she said, “Oh, gosh, haven’t you heard the whole story about that? And I says, “No.” And thought maybe it was a good thing. She says, “Oh, no. You should be talking to some people and doing some research.” So that’s when I got on top of things. And I couldn’t find anything good about it. It was all bad.

BASCOMB: Do you have any sense about the feelings of your neighbors and your friends? What do they think of this?

VAN HOUSEN: Their concerns are our nice clean water, what happens if there’s a break in the pipe. The Ogallala aquifer is right underneath of us. It’s the cleanest water in the world. And we’re on top of an ocean of it. And if that crude gets down into our water system, it could ruin their drinking water, or bathing water, my water for irrigation, to raise the corn, plus my cattle wouldn’t be able to drink that water. It’s toxic. It would put me out of business.

CURWOOD: That's farmer Terry Van Housen speaking with Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb.

Related link:

Trans Canada

Pipeline Proselytizing and Eminent Domain

Much public opinion has turned against the proposed pipeline. (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Native Nebraskan Ted Genoways is an editor-at-large for the magazine OnEarth, published by NRDC. We asked Ted to describe Polk, the town where Myron Stafford preached at the local Baptist Church.

Ted Genoways is editor at large for On Earth Magazine. (photo: On Earth)

GENOWAYS: Polk is a very small town, it's a town of about 300 people that is entirely supported by agriculture. And really the only reason people come into town is to have dinner at the diner, to get supplies at the hardware store, or to come into the church on Sunday. When Myron Stafford came into Polk the first time, as a land agent, he very quickly came a part of the church life there. He became one of the deacons, and when the sitting minister retired, he was asked to fill-in, and ended up being the fill-in minister for three and a half years. And in that time, he not only performed weddings and funerals, but he also managed to secure land agreements from a significant number of the congregants at the church.

CURWOOD: Ted, in your article in OnEarth, you wrote if land owners don’t go for the soft sell from the local preacher, that Keystone will send other representatives that can sometimes threaten people. Can you tell me about that?

GENOWAYS: Yes, there’s at least one land owner I’ve spoken to who said that they not only received letters, but phone calls that came in daily, and then multiple times a day. And eventually, were threatening to use eminent domain in order to condemn the property, and said, if we have to go through that process, you’ll have no say in where the pipeline is eventually sited when it crosses your land. And as it stands, it may be all the way to the western edge of your property and far away from your home and your front step. But if we have to go through all of this, we may decide we’re going to run the pipe right where your house is now. And we’ll demolish your house and run the pipe through your living room. I think a lot of land owners feel that sort of threat crosses a line. It’s not at that point a business negotiation, but it’s intimidation. What I can say is that I hear enough stories from landowners who I’ve approached cold and people who haven’t come to me, but people I’ve just gone up and knocked on their door. And they’ve told me the same stories. I think there’s no question that sort of thing is going on with the land agents.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the governor of Nebraska has given the green light to TransCanada to use eminent domain to build the pipeline. Please tell me about that how a governor could have that power.

GENOWAYS: Ordinarily, the power of eminent domain would be determined by the Public Service Commission. In this particular case, the legislature, as part of a special session, passed a law that specifically removed that power from PSC and put it into the hands of Governor Dave Heineman, someone who everyone understood was a supporter of TransCanada and of the project. So, with that in hand, the letters that have been going out from TransCanada now always start by reminding landowners they have received the power of eminent domain from the governor, and they will use it if they don’t get cooperation.

CURWOOD: So let me see if I have this right. So a private foreign corporation is being given the power to take land from people against their will to make money.

GENOWAYS: That’s right, and under the guise of being for the public good.

CURWOOD: And in general, what kind of response are you seeing from people in Nebraska about the proposed pipeline now?

GENOWAYS: People here, I think, have really gotten their hackles up and said, if this project requires all of this strong-arming in order to go through, there must be something wrong with it.

CURWOOD: Ted Genoways is an editor-at-large for On Earth Magazine. Thanks so much for taking this time.

GENOWAYS: Thanks again for having me.

CURWOOD: Repeated attempts to reach Myron Stafford were unsuccessful. TransCanada says it sees no conflict in this arrangement.

Related link:

Read the On Earth Article

[MUSIC: David Byrne/Brian Eno “Strange Overtones” from Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (Todomundo Records 2010)]

CURWOOD: A promising breakthrough in energy storage is just ahead Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Charles Mingus: Duke Ellington’s Sound Of Love” from Changes One (Atlantic Records 1975) Happy Birthday Charles 4/22/1922 & Duke (4/29/1899)]

Deepwater Disaster Three Years On

Sunset over the gulf (photo: David Levin)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Just three years ago, on April 20th , a deep water BP oil well in the Gulf of Mexico burst open, spewing over 200 million gallons of crude into the Gulf, fouling beaches, fishing grounds and the sea-bed. Now science is trying to understand exactly what effects a spill like this has on the marine ecosystem. One collaboration of chemists, engineers and biologists, at the University of South Florida, is called C-IMAGE, which stands for the Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem. Since August 2012, the C-IMAGE team has been collecting samples in the Gulf of Mexico, and reporter David Levin went along with them. His story comes to us from Mind Open Media.

[CAR RADIO BLARING]

LEVIN: It’s 9 a.m., and David Hollander is driving me around St. Petersburg, Florida, listening to the morning news. Hollander is a marine chemist at the University of South Florida. We’re running some last-minute errands. In a few hours, we’re shipping out for an eight-day research cruise in the Gulf of Mexico. But first, we’ve got an important stop to make. The wig store.

[BEEP FROM CASH REGISTER SCANNER]

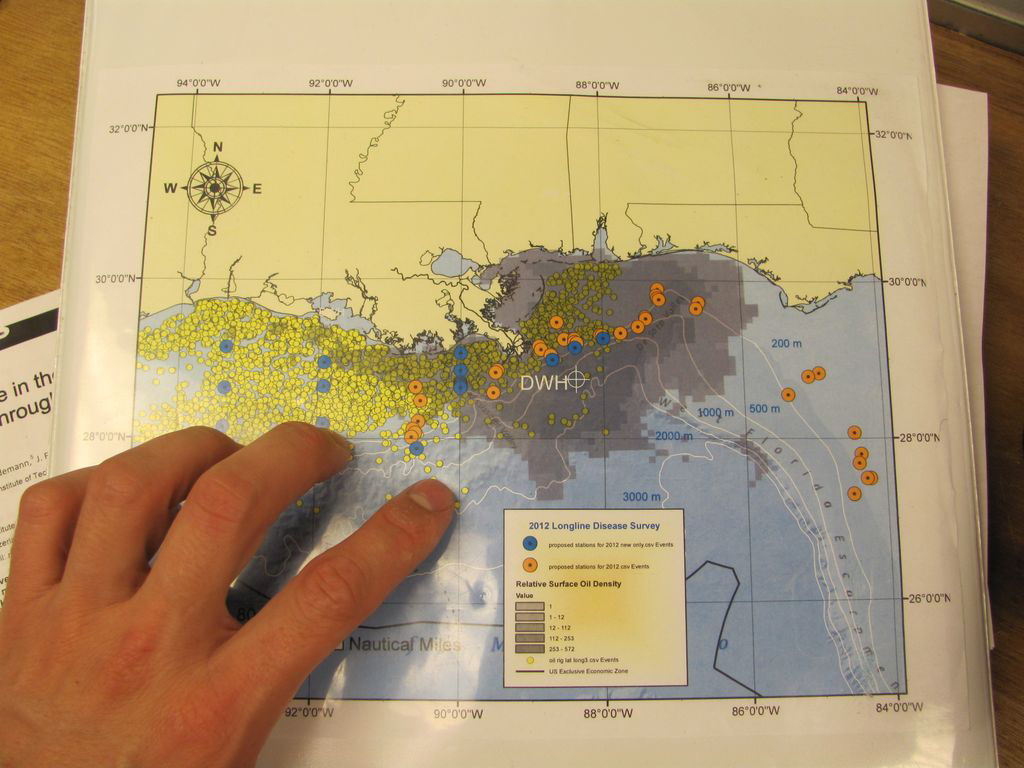

This map shows thousands of oil platforms (represented by yellow dots) scattered throughout the Louisiana and Mississippi Coast in the Gulf of Mexico. White crosshairs mark the site of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, and blue and orange circles represent C-IMAGE sampling sites. (Photo: David Levin)

HOLLANDER: We’re picking up Styrofoam heads. It’s for research, believe it or not.

CLERK: [LAUGHS] OK, good luck to you. Take care.

[WALKING OUT, STORE AUTOMATIC SLIDING DOORS OPEN]

LEVIN: This is something of a tradition - on the research cruise, Hollander and his students will attach the heads to instruments they’ll lower down to the ocean floor.

C-IMAGE scientists Patrick Schwing and David Hollander help bring in a multicorer, a device that samples sediment from the ocean floor. Inside the frame are eight thick plastic tubes that sink into the mud when the device hits the bottom, sealing the sediments inside. The samples will help Schwing and Hollander determine the extent to which oil has affected the ecosystem at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico.

HOLLANDER: …and the heads, because of the pressure, shrink to about a third their size. And if you paint them nicely, it turns out to be quite a memento.

LEVIN: The plan is for these heads, and the instruments, to descend to the source of the Deepwater Horizon spill, at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. Back in April 2010, a floating rig owned by BP exploded. It sank a mile down to the bottom, leaving a broken wellhead on the sea floor about 40 miles off the Mississippi Delta. For three straight months, oil sprayed up from the wellhead to the surface, and as it rose, vast plumes of toxic chemicals and oil droplets broke off, staying suspended in the seawater at different depths. They drifted around the Gulf like toxic clouds.

HOLLANDER: This is not a black layer in the ocean. It doesn’t even look like vinaigrette when you bring it up - it looks like crystal clear water. And the reason is because they were such fine droplets, that you couldn’t see them.

LEVIN: The underwater plumes eventually floated into the continental slope. That’s where the ocean floor drops out dramatically - it falls from a few hundred feet deep to a few thousand.

When the plumes hit the slope, they left a smear of oily residue. Hollander and his team are using this cruise to visit those oil-soaked areas. Their mission: collect both sediment and fish to measure the plume’s impact on the Gulf ecosystem—from huge whales to tiny single-celled animals.

This project’s part of a larger research effort Hollander helped start at USF. He’s organized scientists from around the world to study the aftermath of the spill. The group calls themselves C-IMAGE... And this cruise is the first part of their collaboration.

[CLANKING FOOTSTEPS ON GANGPLANK, ENGINES WHIRRING]

LEVIN: For the next eight days, our home base will be here, on the Weatherbird II, a 115 foot research vessel.

WHITE: Welcome aboard, glad to finally have everybody on board. Looking at a 4 a.m. start, 5 a.m. start…

LEVIN: That’s Matt White, the ship’s captain. We’re about to set sail for an area of the sea floor called the Desoto Canyon, about 60 miles southwest of the Florida panhandle. It’s one of the places where the oil plumes bumped into the continental slope.

[CRANE WHIRRING]

By midnight, we’re at our first stop. Hollander’s team lowers a device called a multicorer into the water. It’s a metal frame about 10 feet tall.

SCHWING: The multicorer literally looks like a giant spider, or a giant lunar lander…

LEVIN: Patrick Schwing is a post-doc in Hollander’s lab. He’s watching the multicorer disappear under the waves. When it hits the bottom, eight plastic tubes inside it will grab mud from the seafloor.

SCHWING: …and at that point we start pulling it back up.

A view forward from the stern deck of the R/V Weatherbird II, the 115-foot research vessel used by C-IMAGE, as it waits to embark on an 8-day research cruise in the Gulf of Mexico. (photo: David Levin)

LEVIN: These coring samples are crucial for understanding how the spill moved around the Gulf. They’ll help the team predict what happens to oil after a deep water blowout, and how long it’ll last in the water. But the life of the oil is only half the picture. To understand its impact on the ecosystem, the team needs to know how fish and other animals are faring.

[ON DECK]

MURAWSKI: Look at that sunrise. That’s sharp.

LEVIN: The next day, at 6 in the morning, Steve Murawski stands on deck, holding laundry baskets full of bait.

MURAWSKI: It’s a combination of squid and Boston mackerel…

LEVIN: Murawski is a biological oceanographer at USF, and he’s running this research cruise along with Hollander. He’s setting up for a long day of fishing. His team is using a winch the size of a 50-gallon drum to let out five miles of metal cable. Strung out along the cable are 500 baited hooks. It’s a technique called long-lining. As the cable spools out, it settles across the bottom, attracting fish that live near the oily sediments.

MURAWSKI: It’s a unique opportunity to see what’s going on with the fishes in the really deep water. We know that there’s oil on the bottom. What we’re trying to see is if that oil is having any food chain effects.

LEVIN: Murawski thinks the toxic chemicals may have been absorbed by tiny animals that live in the sediments…like clams, snails, and worms, which all get eaten by fish. So if there’s any oil lower down in the food chain, it might end up in the fish. If it does, Murawski wants to know. So he’s taking samples from all the species he catches on his long line.

MURAWSKI: So what we're going to do is look at the bile, the blood, the liver, the muscle, and then some of the organs of the fish. So that should tell us number one, is there active oil in the environment, and number two, is it being uptaken by these fish, some of which are of commercial importance.

[FLOPPING FISH ON DECK]

LEVIN: One by one, fish come off the long line and flop onto the deck. Red snapper, Dogfish. Eels. Grouper. Tuna. This part of the research is grueling. Murawski and his students work in 100 degree heat, cutting out fish guts so they can test them for chemicals from the oil.…and when they’re done with that, they reach for the bone saw.

These dogfish (actually type of shark) are common in the Gulf of Mexico, and come up frequently on C-IMAGE fishing lines. (photo: David Levin)

[BONE SAW CUTTING INTO FISH HEAD]

HERDTER: Whoo! Perfect!

LEVIN: Liz Herdter, one of Murawski’s students, just split open the head of a yellowedge grouper. She uses tweezers to pull out delicate bones from its inner ears. They look like tiny oyster shells.

HERDTER: These are otoliths. They’re like an earstone. Steve likes to call it the flight recorder.

USF Graduate student Liz Herdter carefully removes delicate inner ear bones called "otoliths" from a Yellowedge Grouper. Chemicals trapped in various layers of the otoliths provide a detailed record of the fishes' exposure to toxins throughout its life, and may help provide clues to the fishes' exposure to oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill. (photo: David Levin)

LEVIN: That’s because a new layer of bone forms around an otolith every year. They’re laid down like the rings of a tree, and by analyzing these layers, you can track the health of the fish over time.

HERDTER: If they came into contact with any chemicals, there’ll be a chemical marker, so they’re a really neat way to determine what’s been happening in the life of the fish.

LEVIN: Murawski’s team wants to use these samples to create a big-picture view of fish and ecosystem health in the Gulf. Even today, some fish are still in bad shape… Like the 50-pound red snapper Murawski’s holding. It’s got a skin lesion.

MURAWSKI: It’s also got a bad eye! See his eye? His eye’s gone. So this is the kind of fish we want to investigate for whether it has any relationship to oil or not.

LEVIN: Sick fish like this one don’t surprise Murawski. He thinks their bad health is connected to what’s going on in the sediments, and Hollander just found some evidence to back that up.

At a work table crammed into a corner of the deck, Hollander points to one of the cores his team pulled up the night before. It’s a clear plastic tube, about two feet long and six inches wide. It’s full of grey mud, where tiny worms, snails, and clams have burrowed, mixing it all up… But a few inches from the top, that uniform grey suddenly turns brown. And that, he says, means trouble.

From L to R: C-IMAGE researchers transfer a sediment core sample into a storage tube on the deck of the R/V Weatherbird II. (Photo: David Levin)

HOLLANDER: What this really represents is where the subsurface plumes actually touched the sediment surface.

LEVIN: When the plumes hit the sea floor, they wiped out the tiny creatures that usually mix up the sediment. So after the spill, all that churning activity ground to a halt.

HOLLANDER: If there were organisms mixing this, you wouldn’t find these distinct layers, so those organisms are gone.

LEVIN: In some parts of the Gulf, they still haven’t come back. And since some fish live in and near the sediments, Hollander thinks the chemical plumes probably affected them, too, causing the liver problems and skin lesions Murawski’s been seeing. But it’s hard to know for sure. Figuring out what the toxins may have done to the fish is a challenge, and it’s tough to pinpoint which chemicals could be the culprits.

HOLLANDER: You know, you have to be able to trace the oil from its origin, through the water column, onto the sediments, and then as that material degrades, how do you follow it? Not that easy.

From top to bottom: C-IMAGE researchers Patty Smukall (USF Teacher-At-Sea), Theresa Greely, David Hastings, and Patrick Schwing process samples in the onboard lab lof the RV Weatherbird II. (Photo: David Levin)

LEVIN: The C-IMAGE team still has a long way to go. Over the next three years, they’re planning a few more research cruises that will take them back into the Gulf. And next time, Hollander promises to do something with those Styrofoam heads – which we painted onboard this cruise. He plans to lower them to the seafloor at the exact site of the Deepwater Horizon spill. In a way, he says, he’ll give those inanimate heads a look at what’s going on down there - just like he and his students are doing from the surface.

For Living on Earth, I'm David Levin in Tampa Florida.

CURWOOD: David's story comes to us from Mind Open Media. To learn more, head to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- C-Image home page

- USF College of Marine Science homepage

- USF "Adventure at Sea" blog

- Kendra Daly's Zooplankton Ecology Lab homepage

- David Hollander's lab homepage

- Steve Murawski's USF homepage

- Mote Marine Laboratory

[MUSIC: Quantic “Trees And Seas” from Mishaps Happening (Tru Thoughts Ltd. 2004)]

Low Cost Renewable Energy Storage With Hydrogen

Electrochemical cell containing an electrode coated with an iron oxide catalyst film and a counter-electrode that produce oxygen and hydrogen fuel (photo: Curtis Berlinguette/University of Calgary)

CURWOOD: Batteries. They are a convenient but expensive way to store electricity. There is another path to storing electricity that physics has known about for centuries, also expensive and even less convenient. It’s called electrolysis and that happens when a current is passed through water, and separates H2O into its two elements of hydrogen and oxygen. The energy that was in the electricity is released when the hydrogen is burned or oxidized to make water again. Trouble is, this process needs very expensive catalysts to work. Well, now a team of Canadian scientists may have solved the problem of cost, and that could revolutionize the storage of renewable energy. Curtis Berlinguette, a professor of Chemistry at the University of Calgary, explains.

Curtis Berlinguette (photo: University of Calgary)

BERLINGUETTE: Well, the fundamental problem with electricity generated by renewable sources such as sunlight and wind, is the fact that there’s no real good way of storing that energy. If you think of a solar module that’s being installed on the roof of your home, and you go to work during the day when the sun is shining, well, that electricity that’s being generated is not doing you a lot of good. Same thing for wind turbines that are producing electricity at two o’clock in the morning when there’s no demand. So ideally what you want to do is have a storage mechanism that can store that electricity that can’t be used at that particular point in time. And then bring it back to the grid when there is high demand. And that’s the real opportunity with storage.

CURWOOD: And right now, what’s done is that people with solar power or wind turbines put it to the grid as they get it, whether or not the grid particularly wants it.

BERLINGUETTE: Exactly.

CURWOOD: So explain to us how you solved this energy storage problem.

BERLINGUETTE: So we’ve been working on catalysts to make a more efficient transformation of water into hydrogen fuels using that electricity provided by those wind turbines and solar modules. When you do produce that hydrogen, it can then be stored in a tank for as long as you want. And when you need that electricity back, you can convert that hydrogen, mix it with oxygen, and generate electricity that way. Or you can just plug that hydrogen into your furnace and heat your home directly with the hydrogen that’s been produced.

CURWOOD: Now, the big deal with these metal compounds that you’re using for your reactions, I gather is, their makeup. Can you explain to me what’s different from what people have done in the past?

BERLINGUETTE: Well, commercial electrolyzers in operations today rely on crystaling catalytic materials. We’ve been developing some amorphous materials.

CURWOOD: And amorphous is a fancy word for shapeless, all mixed up.

BERLINGUETTE: Exactly. So, if you think about a crystal material like lasagna, where you have an ordered layered structure, you throw that sauce on that lasagna, the sauce will only be able to interact with that top layer. Amorphous materials are much more randomly oriented, much like spaghetti noodles. And so, when you pour sauce on that spaghetti, it can better interact with all of the spaghetti noodles. And this is the real advantage of coming up with amorphous material. In our case, water can come in and interact with all those different metals and make a much more efficient process.

CURWOOD: So you found that having them all disordered really helps. And then, as I understand your paper, you found something else that needs to be done to make this more efficient. What’s that?

BERLINGUETTE: Our big breakthrough is that we’ve been able to introduce multiple different metals to these amorphous materials. If you think of cooking with a single spice, you get a nice tasty dish. But if you have the right combination of multiple different spices, you can make the dish a truly amazing experience. Our finding is that now we’re able to make in a reproducible way, mixed metal oxide films, and metals can then act cooperatively to better mediate this transformation of water into hydrogen fuels.

CURWOOD: What kind of metals are we talking about here?

BERLINGUETTE: We’re taking iron oxide, which is rust, and just doping it with cobalt and nickel. These are Earth abundant metals, and they’re much cheaper than what’s being used today. We find that they give us the efficiency that is comparable or better than the rare and expensive metals that are used, like iridium and ruthenium. If we’re able to match performance of ruthenium, which costs thousands times more than iron, then it’s certainly a big discovery for the field.

CURWOOD: Give me some numbers, Curtis, how much more efficient are these catalyzers compared to what people use today?

BERLINGUETTE: Well, the ones in our original paper just show comparable performance to metals that cost a thousand times more than materials that we’re using. But we have developed some catalysts in our labs that are about 20 percent more efficient than what’s being used today.

CURWOOD: We have a producer in our office who’s very proud of her solar array on her house. And she makes electricity – of course, she just gives it to the grid right now. With your technology, she’ll be able to store that at home and use it at will?

BERLINGUETTE: That’s right. So my utopian view here is for her home not to be connected to the grid in any way. So that way every home in suburban America and Canada, you never have to worry about tying them up to natural gas pipelines or electrical grids.

CURWOOD: So when shall we see these electrolyzers that use your process on the market?

BERLINGUETTE: Well, we’re currently in the testing phase with a large scale electrolyzer with a current player on the market. So these could be out there as early as 2014. The smaller scale units are projected to come out hopefully in 2015.

CURWOOD: Oh, and by the way, is there a name or a nickname for this process or the company that you’re forming?

BERLINGUETTE: We formed a company called Fire Water Fuel...coming to a home near you.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So out of the laboratory and into business it sounds like, professor?

BERLINGUETTE: [LAUGHS] Yes, the reason I went into academia is to stay away from the real world, but here I am.

CURWOOD: Curtis Berlinguette is an Associate Professor of Chemistry at the University of Calgary. Thank you so much, professor.

BERLINGUETTE: Thank you.

Related links:

- Curtis Berlinguette’s research lab website

- University of Calgary Institute for Energy, Environment, and Economy website

- Firewater Fuel website

[MUX - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BIRDNOTE®/SPRING RAINS REFRESH THE DESERT

Cactus Wren, on a cactus! (photo: Tom Grey)

CURWOOD: Spring. There is nothing like its rains to bring the California desert back to life. Here's Michael Stein with today’s BirdNote®.

[RAIN FALLS]

STEIN: A light April rain falls in the Anza Borrego Desert, in southeast California. Cacti and wildflowers glisten with raindrops, and birds begin to sing.

[FINCH AND WREN SING]

The sweet, jumbled notes of a House Finch rise above the sound of the rain.

[HOUSE FINCH SINGS]

Male House Finch in full song (photo: Tom Grey)

A Bewick’s Wren buzzes then breaks into exuberant song.

[BEWICK’S WREN SINGS]

Bewick’s Wren (photo: Tom Grey)

A Cactus Wren joins the chorus, standing atop a barrel cactus, calling gruffly….

[CACTUS WREN HARSH RAPID SEQUENCE]

A Costa’s Hummingbird hovers at a cactus blossom, beating the air with thrumming wings.

[HUMMINGBIRD WINGS SOUNDS]

Costa’s Hummingbird, female (photo: Tom Grey)

A Mourning Dove coos.

[DOVE COOS]

Mourning Dove (photo: Tom Grey)

Spring rains rejuvenate the desert.

[BIRD SONG CONTINUES]

I’m Michael Stein.

CURWOOD: To see some photos of the all these birds, flap your way to our website LOE.org.

[###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Sounds of the desert recorded at Anza Borrego Desert State Park [California] by Gordon Hempton, soundtracker.com. Featured call of Morning Dove provided by Macaulay Library at Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, recorded by W.R. Fish.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org April 2013 Narrator: Michael Stein]

Related link:

Check out this episode on the Birdnote® website

[MUSIC: Jake Shimabukuro “Five Dollars Unleaded” from Live (Hitchhike Records 2009)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...betting on the final throes of winter. Stay tuned for more at Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Duke Ellington: “Midriff” from And His Mother Called Him Bill (RCA/Bluebird records 1987) Happy Birthday Duke 04/29/1899]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Old Whales Learn New Tricks

.jpg)

Humpback feeding (photo: Jennifer Allen, Whale Center of New England)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. As the saying goes, “sharing is caring.” And for a population of Humpback whales in the Gulf of Maine, sharing a new hunting technique with each other is more than caring - changing their hunting culture seems to have helped them survive and adapt to a prey shortage. A new study in Science magazine explains what happened. Luke Rendell teaches biology at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and is one of the study’s authors. Luke Rendell, welcome to Living on Earth.

RENDELL: Hi, it's great to be here.

Luke Rendell (photo: University of St. Andrews)

CURWOOD: So how do Humpback whales normally go about finding their food?

RENDELL: So before this new behavior came along, there was something called the standard technique which involved the animal locating some prey and diving down underneath it and blowing a cloud of bubbles around that shoal of prey. For some reason, small fish don't like to swim through bubbles, whether it’s actually physically difficult for them to do it, or because they perceive this big cloud of bubbles as like a big predator or something scary in the waters. So when the whale blows these bubbles, it creates a kind of barrier to the fish, and this helps them gather the fish together in a nice tight shoal that they can then engulf with their very large mouths.

CURWOOD: So how is it that these Humpbacks needed to find a new way to hunt?

RENDELL: We’re not exactly sure. You can imagine it's very difficult to observe, reliably, see in the water what the whales are doing, and what they’re feeding on. Because we know from research fishing...so fishing boats that go and sample how many fish there are of each species in the area, and the National Marine Fisheries Service in the United States does this on a regular basis in the Gulf of Maine...we know that Herring, which had been a major prey for the Humpback whales crashed in the late 1970s. And then in the early 1980s, another species, the sand lance went through a boom. So we think that the need to develop a new or improved feeding technique was related to this kind of shift in prey.

.jpg)

Humpbacks feeding (photo: Jennifer Allen, Whale Center of New England)

CURWOOD: Please describe for me exactly what the whales did for this new technique?

RENDELL: Well they kind of added something new onto what they were already doing before. So they would already do this bubble feeding, and then they added on a behavior that’s called lobtailing. Lobtailing just means hitting the water with your tail. This is not new to Humpbacks as a whole because they do it all the time in social interactions. What was new is that they stuck it on the start of their bubble feeding sequence. So instead of just diving and making bubbles they would hit the water with their tail a few times and then dive, and make bubbles and go through their normal hunting technique. We don’t really know for sure what function that serves. We think maybe that it creates a disturbed patch of water at the surface, which prevents the fish from swimming and jumping out the way, for example. But that is something we’re not totally sure about.

CURWOOD: And now this feeding method has spread among the whales.

.jpg)

Humpback lobtailing (photo: Jennifer Allen, Whale Center of New England)

RENDELL: That's correct. Yes, so from one whale doing it in 1980, the current estimates are that somewhere between 35 and 40 percent of the population now know about and do this behavior.

CURWOOD: And your paper says this feeding method is spread among whales by observation. So I'm just wondering how much of a new discovery is it that Humpback whales learn from each other like this?

.jpg)

Humpback feeding (photo: Jennifer Allen, Whale Center of New England)

RENDELL: Well, in terms of actual physical behaviors like this lobtail feeding, then that has never been described before. What we do know, of course, obviously is that Humpbacks are very famous for the songs. In the 1970s, there was a craze of putting out CDs with Humpback songs on them. They’re very striking and famous animal displays, and we know that they learn that song from each other because we've observed population songs changing very rapidly in ways you can't explain in any other way than they are learning the song from each other. So the idea that they learn some kind of behavior from each other is not new, but we had no idea that it would actually involve things like their feeding behavior as well as their song.

CURWOOD: So this is essentially a cultural change?

RENDELL: Yes, so it's culture in the sense that it is learned from other individuals, right? And the pattern of spread that we observed was much better explained if we took the social network into account than if we did not. So animals that hung out together a lot - if you hung out with an animal that knew the behavior already, you were much more likely to learn the behavior yourself. So we don’t actually know for sure whether this lobtailing is functional in the way that I sort of speculated about earlier, or whether it is just an arbitrary thing, right? We just wave our tails this way before we eat. In many respects, from the perspective of understanding it as a cultural behavior it doesn’t really matter whether it’s functional or not. The interesting thing is that is spreading to the population in the way that we seen that it does.

CURWOOD: So how extensive is the whale’s sense of community? To what extent do they share knowledge and behavior widely, do you think?

RENDELL: Well, to really answer that you have to be inside a whale’s head yourself, right? [LAUGHS] But we can deduce from what we observe is that the animals have a very clear sense of their identity and the identity of the group with which they are involved right? So the Humpbacks, each breeding population has his own song, and the animal can very easily know whether it's with its population just by listening to the songs that the males are singing, for example. And we also know there are some long-term relationships, so year on year certain pairs of females will often be seen together on the feeding grounds.

CURWOOD: So what can we learn about other creatures - and I include us humans in that - by studying this behavior in whales?

RENDELL: I think we can potentially learn a lot about the evolutionary history of our species. People have been fascinated about the evolution of the culture in humans for decades. Traditionally they have focused on our closest living relatives - chimpanzees and other great apes as well as monkey species all from the same kind of primate lineage. I think what this study does and a number of other studies that have been coming out recently on whales and dolphins is really question whether that approach is the best one. Whether we should just simply restrict ourselves to looking at our closest ancestors, or whether we can't understand something more about the evolutionary processes that lead to things like culture by looking at completely unrelated lineages.

CURWOOD: I suppose if you study the whales long enough you might find out all sorts of things. I mean, you might find that they switch their food not so much for scarcity, but for flavor?

RENDELL: Yes, we understand that there are some Killer whales who eat fish, and some Killer whales that eat dolphins. And they do not switch. The fish eaters keep eating fish, and the dolphin eaters or the porpoise eaters or the seal eaters keep eating those animals. And even though the salmon are swimming right by their nose...

CURWOOD: Wait, wait. You’re telling me that some Killer whales love red meat and others just won't go for it?

RENDELL: Yes, that’s right. There are fish eaters and mammal eaters. They live in different groups and have different call dialects. And they do not mix.

CURWOOD: Biologist Luke Rendell of the University of St. Andrews in Scotland is one of the authors of a new study about whales and their culture in Science magazine.

CURWOOD: Luke, thanks a lot.

RENDELL: Thanks for having me. It’s been great.

Related links:

- Rendell's staff page

- Paper in Science

- Whale Center of New England

[MUSIC: Darcy James Argue “Redeye” from Infernal Machines (New Amsterdam Records 2009)]

Joe’s Pond Ice Out Contest

The ice begins to recede from the shore before the flag goes through (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

CURWOOD: Spring is well underway in much of the country, but way up North in Vermont, winter is only now loosening its icy grip. And that means it’s time for little Joe’s Pond, tucked between the towns of West Danville and Cabot to step into the spotlight. As the thaw takes hold, Vermonters head to general stores throughout the state to buy tickets for the Joe’s Pond Ice Out contest. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald - Vermont born and bred - has the story.

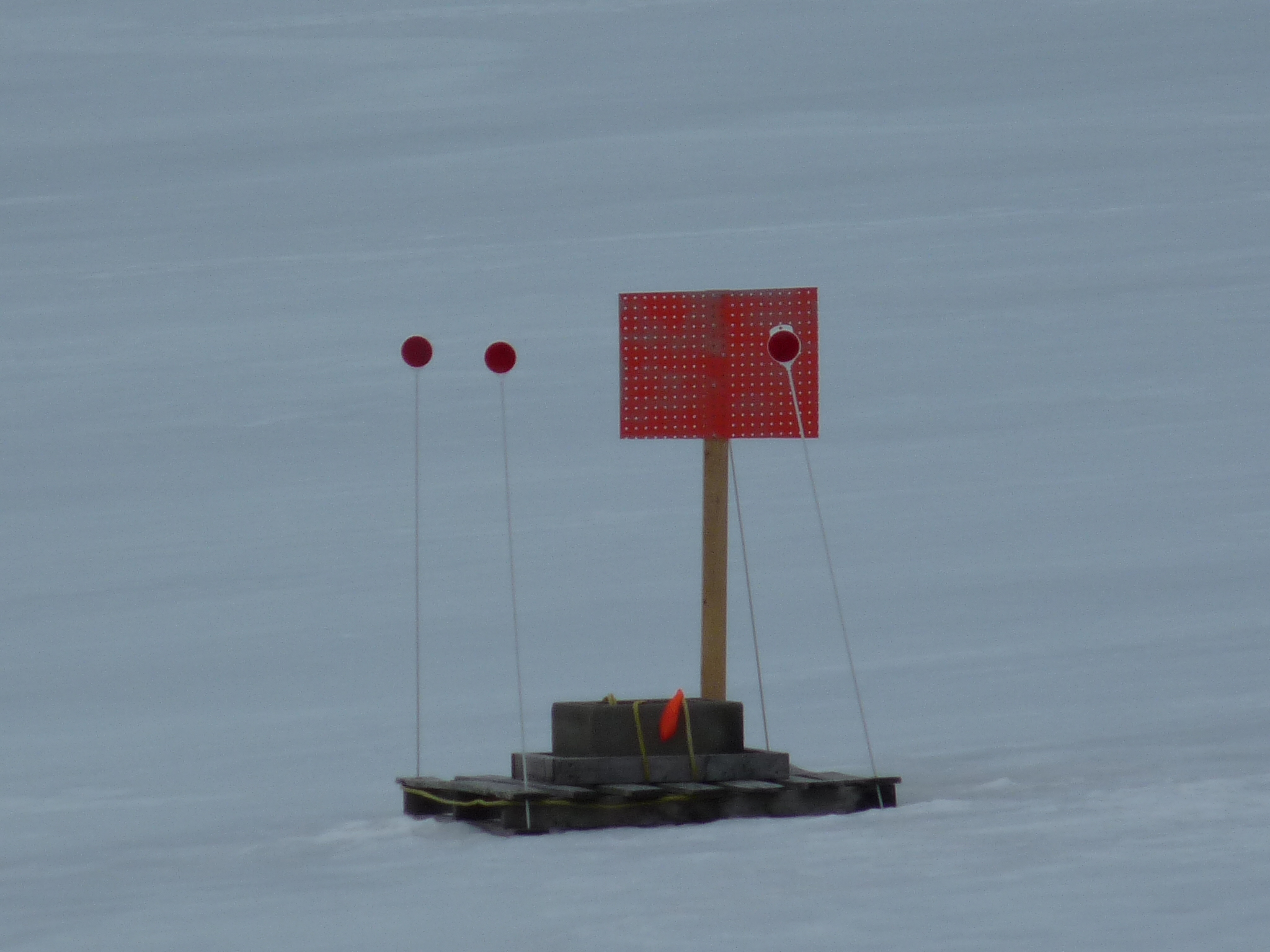

The flag (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

FITZGERALD: All you have to do to win the Joe’s Pond Ice Out contest is guess the precise time that a flag attached to a cinder block resting in the middle of Joe’s Pond in West Danville, Vermont, will fall through the melting ice. The Ice Out title goes to the best guess.

JANE BROWN: Whoever comes closest, or, usually it’s right on. The exact minute.

FITZGERALD: Jane Brown is the current co-chair of the Joe’s Pond Association’s Ice Out committee. When the contest began in 1988, only a few hundred people took part. But, she says, the competition has grown.

JANE BROWN: This year we sold almost 12,000 tickets.

FITZGERALD: Tickets go for a dollar a piece. The organizers take out their expenses, then the pot is split between the Joe’s Pond Association and the contest winner. This year, it’s decent chuck of change.

JANE BROWN: It will be just under $5,000 after the split.

FITZGERALD: I grew up in Montpelier about 30 miles away from Joe’s Pond. As a kid I saw Ice Out tickets for sale in local shops and wondered about the contest, so I decided to check it out. I met Jane at her house, and her husband Fred took me down to the pond.

[CAR DOOR SLAMS, FOOTSTEPS]

The flag in the center of Joe’s Pond (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

FRED BROWN: My role mainly is really to help my wife, and in addition to that, I’m the webmaster for the Joe’s Pond Association.

Jane and Fred Brown (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

FITZGERALD: He takes me to the shore where the dark ice stretches to the opposite bank. It’s a balmy 65 degrees, but it’s still frozen. The only open water is right at the edge, where a fountain shaped like an otter spits water into the pond.

[WATER FLOWING]

FITZGERALD: Fred points out the red flag sticking up from a cinder block about a hundred yards out. Then we head back to the deck of a small house, where the official Ice Out clock is set up.

The official Ice Out clock (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

FRED BROWN: Actually this is a new clock this year, also. It’s a weather-proof clock.

FITZGERALD: A series of wires connect the clock to a rope that runs all the way out to the flag.

FRED BROWN: You see the wires coming from the clock, down to the other deck and out to the flag.

FITZGERALD: When the flag breaks through into the lake, or floats away on a loose chunk of ice, the rope goes taut.

FRED BROWN: When that connection down there is pulled, this clock will stop, so that will be the official ice out time.

FITZGERALD: The rules of the Joe’s Pond Ice Out have been in place since a man named Jules Chatot started the contest in 1988. Chatot and his friends would come out to the pond during the winter for beer and cards.

You need snow shoes to get across Joe’s Pond in the winter (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

FRED BROWN: Probably they had a little cabin fever and so they just started saying ‘let’s guess what time the ice will go out’. It spread from then and pretty soon they started having tickets in the stores and here we are today.

FITZGERALD: The place that sells the most Ice Out tickets today is the Hastings Store in West Danville. A wooden sign on the front porch reads “Ice Out Tickets Sold Here” in painted red letters. It’s squeezed next to the Joe’s Pond Craft Shop, and doubles as the town’s only post office. The Hastings Store is the hub of this one street downtown.

Hastings Store in West Danville, where many Ice Out tickets are sold (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

[DOOR SLAMS AT HASTINGS STORE]

FITZGERALD: Hastings looks like what is, an old fashioned family business.

LARABEE: It’s been in my family since October 13, 1913.

FITZGERALD: That’s Jane Larabee, formerly Jane Hastings. She says that her family has been tracking the ice for generations. Before the contest got going, her father and a friend of his would bet on whether the ice would go out before May 1.

LARABEE: And they’d bet a dollar, and they would tack that dollar to the ceiling. Right about there. Then whoever would win would let it ride to the next year so we had those two dollars stuck to the ceiling for years.

FITZGERALD: Jane and her husband have sold over 1,000 Ice Out tickets at the Hastings Store this year. Most of these go to locals, but the Joe’s Pond Ice contest has begun to go global.

Joe’s Pond Association members Larry Rossi and Jon Klee setting up the flag during the winter (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

LARABEE: I did sell a ticket one fall foliage and in May I got a phone call, and I said, where are you calling from and he said, “South Africa”. So you know, we’re known far and wide!

FITZGERALD: Jane shows me one of the tickets. It has the dates of the last three Ice Outs on it, but that’s all the help you’re going to get. She says her customers have some unique ways of making predictions.

LARABEE: It’s birthdays, anniversaries, lucky numbers. Sometimes we have the dowsers come in and they’ll dowse with a pendulum over a calendar. You know it’s just one of those things. Whatever floats their boat.

FITZGERALD: These days, competitors have a new variable to contend with—global warming. Over the past few years, Vermont winters have been getting milder, and the Ice Out times are creeping up the calendar. In 2010, the ice went out on the earliest date on record, April 5.

LARABEE: That’s was the year that had 3 or 4 days of 80 degree weather, that’s very unusual. In fact, my husband sold that ticket and he told the fellow it's never gone out that early, and the fellow said, well it’s just a donation then. Guy won $5,000.

FITZGERALD: But this winter has been cold, and Jane’s hoping the ice will hold out until May. Each year she buys one ticket.

LARABEE: I always pick May 2, at 12:51 because that’s when my son was born. It hasn’t won in 35 years, but then, there’s always this year!

FITZGERALD: There’s usually only one Ice Out winner - although there can be ties - but the contest is good for the whole community. It brings Central Vermont a bit of publicity and gives neighbors something to chat about during the winter when they’re picking up their mail at the Hastings Store. And the other half of the money funds the Fourth of July firework display.

LARABEE: If you win the jackpot, fine. But if you don’t, you still get to see the fireworks and they’re reflected off the pond so you actually get to see them twice, which is wonderful.

FITZGERALD: When the ice melts, the process begins all over again. Hastings never has to take the sign down because they start selling tickets for the following year right after the winner has been announced.

This year, the flag went through the ice on April 23rd, but the clock didn’t officially stop until April 24th at 8:46 AM because the rope had frozen into the ice. (photo: Jane and Fred Brown)

LARABEE: Could I interest you in a ticket?

FITZGERALD: For next year?

LARABEE: Just as soon as the ice goes out they print new ones.

FITZGERALD: Well I’ll stop by next time I’m in Montpelier.

LARABEE: You do that. And we’ll be sure to get you a nice fresh one.

FITZGERALD: On April 24, we got word that the clock had stopped at precisely 8:46am, when the flag finally fell through the ice. The winner of the 2013 Ice Out is Gary Clark of Barre, Vermont. I called him up. Congratulations, Gary!

CLARK: Thank you very much. I’m still in shock. Time to come down off the cloud and move on I guess.

FITZGERALD: How did you make your guess? What kind of methods did you use to make your prediction?

CLARK: I’ve been playing the last few years and this year I decided to splurge and bought thirty tickets. And I decided to work backward from May 1 picking a time in each day. So that’s about my scientific procedure.

FITZGERALD: So you cast a wide net?

CLARK: Yes.

FITZGERALD: Now, Gary, if you don’t mind my asking, how much is the purse?

CLARK: Just under $5000.

FITZGERALD: And what are you going to do with the money?

CLARK: Oh, probably donate some of it. I’m not quite sure. My wife knows about it so she’s entitled to some of it.

FITZGERALD: Thanks for joining us Gary.

CLARK: Thank you very much.

FITZGERALD: So Gary won $5,000 dollars. Maybe I will buy a ticket for next year! For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald.

Related links:

- Joe’s Pond Association’s Ice Out page

- Fred and Jane’s Brown’s Joe’s Pond Blog

[MUSIC: Bonobo “Don’t Wait” from The North Borders (Ninja Tune Records 2013)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth, Christiana Figueres, the UN climate negotiations chief, says she’s optimistic about finding a real solution to global warming.

FIGUERES: We don’t have an option. We don’t have a plan B because we don’t have a planet B. We are going to solve this.

CURWOOD: Finding the way forward for global climate negotiations next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Alicia Juang, Qainat Khan, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. A special thanks this week to Ari Daniel Shapiro and Mind Open Media with support of the BP/Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth