June 14, 2013

Air Date: June 14, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The US and China Strike A Climate Deal

View the page for this story

The world’s two largest global warming gas emitters, the United States and China, have forged an agreement to work together to cut their use of climate-disrupting hydrofluorocarbons. Jennifer Morgan, director of climate and energy programs at the World Resources Institute, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss the significance of the deal. (05:25)

Methane Leaks

View the page for this story

A new report from the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, C2ES, pegs US carbon dioxide emissions at levels not seen since the mid 1990’s. Natural gas replacing coal for power generation has helped to lower emission rates, but methane leaks from wells and pipelines adds a powerful greenhouse gas to the atmosphere. C2ES president Eileen Claussen explains the methane leaks to host Steve Curwood. (06:10)

Science Note

/ Naomi ArenbergView the page for this story

Researchers at the University of Texas have developed an “invisibility cloak” using a meta-screen of ultra-thin copper wire. Naomi Arenberg reports on the implications of this disappearing act. (02:05)

Elwha Dam Comes Down

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

The removal of hundred year old dams along the Elwha river in Washington State have freed up salmon runs, but they have also clogged up a water treatment plant with sediment. Still as Ashley Ahearn of the public radio collaborative EarthFix reports, that sediment is creating a great habitat for fish. (05:45)

Nicaraguan Canal

View the page for this story

The first ships sailed down the Panama Canal in 1914. Now, nearly one hundred years later, Nicaragua has an agreement with a Chinese company to build a canal of its own to link the Pacific and Atlantic. Journalist Tim Rogers and host Steve Curwood discuss the potential environmental impacts of this 40 billion project. (07:05)

Vanishing Point

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The American Bittern’s camouflaged plumage makes it nearly impossible to see when standing still. But writer Mark Seth Lender was lucky enough to find one strutting its stuff on a pond in northern Maine. (02:05)

Winery Adapting to Climate Change

View the page for this story

A new report suggests that by the year 2050 as much as half of South Africa’s wine growing region will no longer be able to grow grapes as a result of climate change. Living on Earth host Steve Curwood visited Backsberg Estate Cellars, South Africa’s first carbon neutral vineyard to see how it is already adapting and implementing creative solutions to reduce its contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. (18:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Jennifer Morgan, Eileen Claussen, Tim Rogers

Reporters: Alicia Juang, Ashley Ahearn, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Global greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, and there's no mandatory agreement to control them. But a new deal between the two largest polluters might help.

MORGAN: It's very significant that these two players are coming to the table. It's a new era in a way for US-China relations on climate, which hopefully then will build much more transformational change in the future.

CURWOOD: What the US and China agreed - and what it might achieve. Also, when a dam comes down, how the river can heal itself.

MCHENRY: We've seen pools that have amphibians in them already. There's a lot of insect activity here. It's not a moonscape, it's an early successional landscape that's just going to get better.

CURWOOD: We'll have those stories, and a close encounter with an American Bittern and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic smoothies, yogurt, and more.

The US and China Strike A Climate Deal

HFCs are used for refrigeration and air conditioning (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, This is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The UN has been haggling over rules to address climate change since 1992, but has yet to reach a comprehensive deal. But now the world’s two largest emitters, the US and China, have struck an agreement to limit their use of the potent greenhouse gases called hydrofluorocarbons, HFCs. The pact is based on the rules of the Montreal Protocol that governs the gases that destroy the ozone layer. To put this in perspective, we're joined now by Jennifer Morgan, Director of the Climate and Energy Program at the World Resources Institute. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MORGAN: Thank you. Good to be here.

CURWOOD: So first off, what exactly are these chemicals and how are they currently being regulated on an international level?

MORGAN: Well, these are chemicals that go into refrigerators and air conditioners and currently they aren't all that regulated on the international level. They were replacements for CFCs which people might remember back from the late 80s which were a main cause of the hole in the ozone layer - these were the replacements for those over time. But now it's been found is that they are very potent greenhouse gas emissions and cause climate change.

CURWOOD: So - don't make a hole in the ozone layer, but heat up the planet.

MORGAN: Exactly. These are very damaging. They’re kind of like super greenhouse gas emissions, 1000 times more potent than carbon dioxide, which is the main greenhouse gas that comes from the burning of fossil fuels. A small share, but a very big impact.

CURWOOD: So what exactly have United States and China agreed to at this point?

MORGAN: Well the U.S. and China basically have agreed that they’re going to work together and that they're going to work under the Montreal protocol to phase down both the consumption and the production of HFCs. So I think what they're aiming for is to bring other countries along to implement...to agree to and then implement...such a phase out by 2050.

Jennifer Morgan (photo: World Resources Institute)

CURWOOD: So if China really goes along with this it would be accepting then binding limits on this particular gas?

MORGAN: Yes, that's part of how the Montreal protocol works. There's a fund to help give support - it’s unclear whether China would get that - but it's basically stepped out from its position with India and is working with United States on this one.

CURWOOD: How significant is it that these two giant polluters are coming to the table in terms of the climate negotiations?

MORGAN: It's very significant that these two players are coming to the table. It builds confidence, I think, of other countries for the most part - especially in Asia - that they're going to work to find solutions rather than battle it out and things collapse. It's a new era in a way for US-China relations on climate which hopefully will then build much more transformational change in the future.

CURWOOD: How does this rapprochement over HFC's impact the UN climate negotiations?

MORGAN: I think it will inspire many, because one of the key worries often of other countries is whether the US and China can work together as the two biggest polluters. So I think it will inspire that. I think it will put pressure on countries that want to work with China like the EU to really step it up and have their heads of state engaging the Chinese president as well. But I think it’s going bring a bit of a jitter in a positive way into the climate negotiations because it shows that international cooperation is really possible.

CURWOOD: Now, just recently a group of countries announced that they are establishing what they call a renewables club to deal with renewable energy issues together. Can you describe that club for me and what it might mean for climate negotiations?

MORGAN: Sure. The German environment minister brought together 10 countries in total; Germany and China and India, South Africa, and even the United Arab Emirates and a couple of European countries to create this renewables club and the main goal is to scale up renewables as quickly as possible. Germany clearly is doing this; it's got almost quarter of its electricity right now from renewable energy. And the goal is really step-by-step to do that; to look at how they can work together to make that happen. I think for the climate negotiations it is part of this debate of trying to get more ambition now because it's recognized that what's currently being implemented around the world is not enough.

CURWOOD: What do you make of China and India being invited to the renewables club, but not the United States?

MORGAN: It's not that much of a surprise. These countries all have ambitious national policies in place and that has been proven to be the main thing to drive the buildup of renewables. So these are major players in the global marketplace, and as of yet US is lagging behind. So I think it's an indication of that. And the US needs to put a national policy in place to drive renewables then and they can join I think.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is the Director of the Climate and Energy program at the World Resources Institute. Thanks so much for joining us.

MORGAN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- White House statement on US-China HFC-related climate deal

- Jennifer Morgan’s Page at the World Resources Institute

Methane Leaks

The valves on natural gas pipeline are a source of leaking methane. (Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions just reported that CO2 pollution in America is at rates last seen in the mid 1990’s, partly due to power plants switching from coal to cheaper natural gas. While gas is less polluting than coal, it still pollutes, and its main ingredient, methane, often leaks from wells and pipelines. Eileen Claussen, former Assistant Secretary of State and now President of the Climate Solutions Center, joins us now from Washington, DC.

CLAUSSEN: There's no question that if natural gas replaces coal in power plants there’s a net benefit for the climate. But natural gas is a fossil fuel and burning it does result in greenhouse gas emissions - and there’s always been some amount of leakage. It’s really an issue of the wells and the pipelines. The numbers are not huge, but methane is a potent greenhouse gas. And one of the challenges is to make sure there are virtually no leaks of methane as we move natural gas to the power plant, to the home, to the manufacturing facility.

CURWOOD: Where does this methane come from? You say pipeline and wells...what about fracking?

C2ES President Eileen Claussen (Photo: C2ES)

CLAUSSEN: We actually don’t have very good data to know whether fracking itself is part of the problem here. There is an effort underway right now to do some real measurements so we will have a handle on how much methane is being released, where it is being released, and then we can apply the technological solutions that we know work to wherever those leaks are or could be.

CURWOOD: So these numbers look quite small. You say we’re down to one and a half percent of methane escaping. Why is that a problem?

CLAUSSEN: Well, let me say that one and a half percent is an EPA estimate and we don’t actually know whether that’s the right number or not. But there are many sources of methane. I mean, natural gas leaks is a relatively small amount compared to livestock or landfills or other ways that methane gets into the atmosphere. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a problem because methane is a very potent greenhouse gas with a relatively short lifetime. So it’s more potent than carbon dioxide, but carbon dioxide lives in the atmosphere much longer. So if you want to make short term gains in addressing greenhouse gas emissions, dealing with methane is really important. But we actually have a lot to do to deal with methane across the board and globally as well.

CURWOOD: By the way, how do you detect and then manage a methane leak?

CLAUSSEN: Well, there are a whole lot of technical and engineering solutions that can help here. There are zero-bleed pneumatic controllers; there are good valves, improved valves; there are corrosion resistant coatings; there are dry seal compressors. We can do a much better job of leak detection and leak repair, and make sure not much actually gets out. From an engineering or technical point of view, there are actually a lot of things that can be done and we should do them.

CURWOOD: You would think the industry would want to do this. I mean, every time they lose a molecule of methane, then they’re losing money, right?

C2ES President Eileen Claussen at the Natural Gas Report release (Photo: C2ES)

CLAUSSEN: Well, absolutely, and all the efforts to date, let’s say over the last ten years or so, have been undertaken voluntarily by the industry. EPA estimates - and these are estimates - that leaks from natural gas systems declined by about 10 percent between 1990 and 2011 even with the expansion of natural gas infrastructure. So there is an effort to make sure that the methane is captured, and we’re hoping that those efforts continue and are speeded up so that we don’t end up emitting greenhouse gases from our natural gas systems.

CURWOOD: Where else besides electricity generation might we substitute natural gas to reduce carbon dioxide emissions?

The CEOs of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions discuss the emissions of natural gas at the release of the report. (Photo: C2ES)

CLAUSSEN: There are a couple of other uses that I think could be really valuable. Heavy duty trucks and fleets often use diesel. There would be a real environmental benefit to replacing that with natural gas. In home heating and home appliances, we use a certain amount of natural gas, but the more natural gas we use the better off we’ll be because there’s a huge amount of energy loss in our electrical systems when you use electricity for heat and home heating and so on. And even in manufacturing, if we were to use combined heat and power, we would be emitting fewer greenhouse gases. So there actually are a lot of different places where increased use of natural gas would benefit the climate.

A natural gas power plant cuts down on carbon dioxide emissions but may increase more potent methane emissions. (Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: The low price of natural gas these days has helped the tar sands extraction in Alberta. They use it to make it more liquid. How important is that use of natural gas?

Natural gas wells may leak methane into the atmosphere. (Photo: bigstockphoto.com))

CLAUSSEN: [LAUGHS] It’s better than using something else. And there’s a bigger question, of course, about the tar sands themselves. When I look at the use of natural gas, I think that there’s no question that it’s a benefit, but if you’re using natural gas and, as a result of that, not using, for example, renewables, that is clearly not a benefit. So it’s a question of making sure you use natural gas in ways that actually provide you with a climate benefit.

CURWOOD: Now at the end of your report, you note that natural gas can’t be the long term solution. Why not?

CLAUSSEN: Well, I think natural gas is a bridge to a really clean energy future - a zero carbon future. It’s a pretty long bridge. We have a lot of natural gas. If we use it to substitute for other fossil fuels, greenhouse gas emissions will continue to go down. But again, we have to make sure that we have better solutions, whether it’s wind or solar or nuclear, by the time we get to 2030, 2040, 2050, if we really want to avoid serious climate change.

CURWOOD: Eileen Claussen is the President the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions Center in Washington. Eileen, thank you for joining us.

CLAUSSEN: It’s a pleasure.

Related links:

- Eileen Claussen

- Report(ed)

[MUSIC: Steve Earle “Invisible” from Low Highway (New West Records 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...plans to build a new canal to link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. That story is just ahead here on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sometime Ago” from return To Forever (ECM Records 1972) Happy Birthday Armando “Chick” Corea 06/12/1941]

Science Note

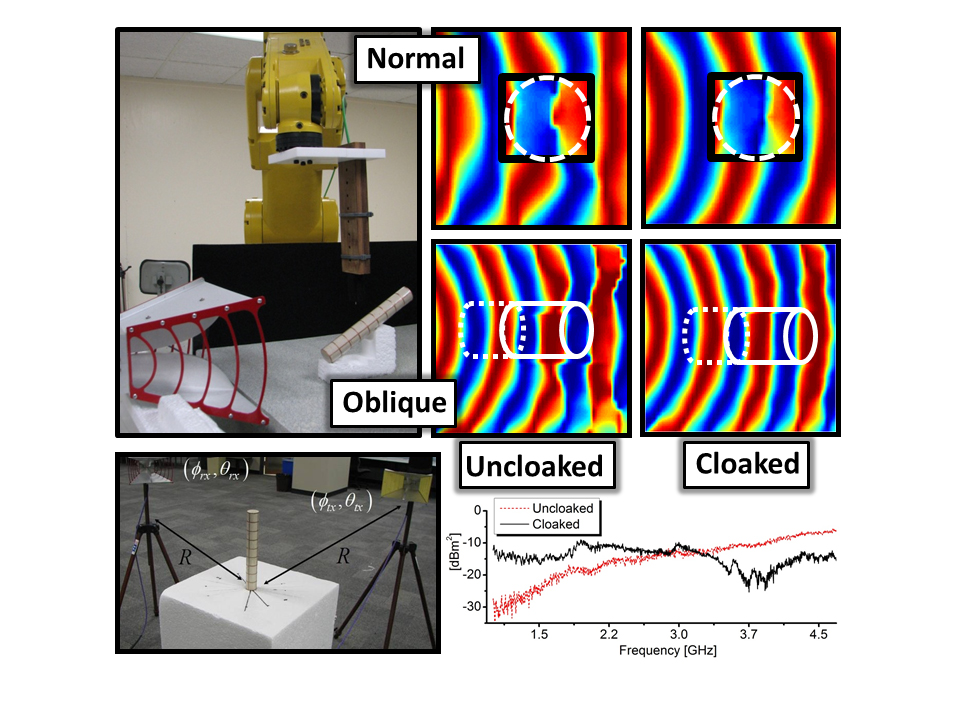

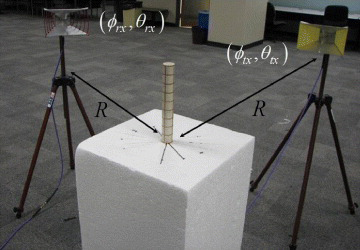

“Invisibility Cloak” at the University of Texas, Austin, and graphs describing the effectiveness of the device (Image: Adrienne Lee, University of Texas)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. One of the most potent powers of a superhero can be invisibility. Now scientists in Singapore appear to have managed that trick for real, with panels of glass that bend light and make a goldfish disappear. But in this week's note on emerging science, Alicia Juang reports that that's not the only way to achieve this superpower.

Our science note is read by Naomi Arenberg.

ARENBERG: Anyone who has read the Harry Potter books remembers his reliable Invisibility cloak, a magical, silky garment that helps him evade trouble. But what was once confined to science fiction and fantasy is becoming reality. Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin have developed a sort of invisibility cloak of their own. It’s called a “metascreen” and is made of threads of ultra-thin copper attached to a polycarbonate film. This cloak works by emitting radiation to cancel out disturbances from electromagnetic waves hitting the cloaked object.

The researchers call this technique “mantle-cloaking” and say it’s better than previous technology that bent waves around an object. And old cloaks also required thicker, bulkier materials. So far, the cloak can only make objects “invisible” to a particular range of electromagnetic frequencies. This means, if you navigated using radar, the object would be invisible, but if you used your eyes, you’d see it. But since light also is a kind of radiation: the Texas researchers say that the principle of scattering waves should also work with visible light.

This development opens up many possibilities; for instance, better camouflage and more sophisticated optics technology. So the idea of disappearing with the swish of a cloak, as Harry so often does in the corridors of Hogwarts, may one day be also possible in our Muggle world.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I'm Naomi Arenberg.

Related links:

- Print Your Own Invisibility Cloak

- University of Texas Newsletter

- Open Access Journal for Physics story on the University of Texas development

- Scientific American story on invisibility research in China

Elwha Dam Comes Down

Ancient stumps from the Elwha River bed (Photo: Ashley Ahearn/ Earth Fix)

CURWOOD: Workers in the state of Washington have almost finished tearing down the hundred year old dams on the Elwha River. The hope is to restore some once legendary salmon runs and allow the coho, pink, sockeye and chum to flourish again alongside the steelhead trout. But the newly free-flowing river has churned up so much sediment that it's clogged a local water treatment plant. Still, as Ashley Ahearn of the public media collaborative EarthFix reports, the rich sediment is providing excellent habitat for fish and wildlife on the Olympic Peninsula.

[WALKING OUTDOORS]

Mouth of the Elwha, where millions of cubic yards of sediment, released from above the dams, are creating new beaches and sandbars. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn/Earth Fix)

AHEARN: I’m at the mouth of the Elwha catching up with Anne Shaffer, who is a tough lady to keep up with, I will tell you that much.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

Everything is fresh. That’s my first impression. This is a new place. I’m walking on new earth that’s been delivered from above the lower dam now, millions of cubic yards. It’s making little tidal pools, sand banks, depositing hundreds of huge logs. It’s coming back to life.

SHAFFER: It’s unvegetated but this is definitely the habitat that juvenile fish need.

[PEOPLE TALKING]

AHEARN: Anne Shaffer stands with a group of volunteers in hip waders. She’s the executive director of the Coastal Watershed Institute. Every month she and the team come out to these tidal pools near the mouth of the river with a large net called a seine net.

SHAFFER: You ready?

[SEINE NET HITS WATER WITH A SPLASH]

AHEARN: The group gently works the net in a narrowing circle, corralling the fish into one place where they can count and measure them.

SHAFFER: Shake down as you go, watch for fish.

AHEARN: The goal is to keep tabs on what kinds of fish are using this new habitat to fatten up before heading out to the open ocean. Volunteers call out the names and lengths of each fish in the net, as Anne Shaffer jots them down on a clipboard.

WOMAN: Starry flounder 150.

MAN: Steelhead 140, 147.

AHEARN: Chris Byrnes is a fish biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and one of the volunteers today. He’s cupping a tiny Steelhead in his hands.

BYRNES: Do we have a camera? I’d like to get a picture of this one.

AHEARN: How come?

BYRNES: Because his fins are all eroded. He looks really roughed up.

[WATER LAPPING]

AHEARN: All the sediment that’s been released from above the dams is making life hard for fish right now. But there’s more to come. So far only one-fifth of the total sediment the dams have held back over the past 100 years has been released.

BYRNES: And all the steelhead look this way. They look really kind of haggard.

AHEARN: Anne Shaffer says it’s too early to know just how much the sediment is affecting fish population numbers.

SHAFFER: We’re still seeing a lot of fish, we’re still seeing approximately the same species richness and then we’re seeing changes in the abundance by species. And it’s too early to really interpret that other than there’s a response going on and that’s certainly to be expected.

AHEARN: The sediment rushing down from below the dams may not be great for fish right now, but it’s doing wonders for their habitat. All that dirt and clay is forming new beaches and mudflats here. And the fish are using them. But the mouth of the Elwha isn’t the only part of the river where new habitat is emerging.

[FOOTSTEPS]

MCHENRY: We’re going to head down here a ways a quarter mile or so and I’ll get you out on the former reservoir surface.”

AHEARN: Mike McHenry is a fisheries habitat biologist with the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe. He’s taking me to a place very few people have seen - because it’s been underwater for 100 years. We’re about 5 miles from the mouth of the Elwha – just above where the lower dam used to be. Not too long ago, this was a 250-acre reservoir known as Lake Aldwell. Now it’s a lifeless-looking mudflat with the Elwha flowing through it in braided, chocolatey channels. But McHenry says nature’s already bouncing back.

MCHENRY: We’ve seen pools that have amphibians in them already. There’s a lot of insect activity here. It’s not a moonscape, it’s an early successional landscape that’s just gonna get better.

Volunteers from the Coastal Watershed Institute count and measure fish using the newly available estuarine habitat at the mouth of the Elwha this spring (Photo: Ashley Ahearn/Earth Fix)

AHEARN: This newly-exposed mudflat won’t be brown for long. The Lower Elwha Klallam tribe is working with Olympic National Park to plant native trees and shrubs here. 66,000 trees have been planted and about 350,000 more will go in above both dams by the time the dam removal process is finished. McHenry leans over to brush the green leaves of a sturdy looking plant, fighting its way out of the sandy soil.

MCHENRY: We have thimbleberry here, which is a native shrub.

AHEARN: This area was cleared and logged 100 years ago – and then submerged when the dams went in. Now that the lake has drained away, giant ghostly stumps have emerged. Mike McHenry is not a short guy – and he is dwarfed by the remnants of these trees.

MCHENRY: And you can see the old growth stumps. The stumps out here are preserved almost like they were cut yesterday and there were some amazing trees that stood in this valley at one time.

AHEARN: The stumps make for a sort of forlorn scene now – like something out of the children’s book ‘The Lorax’. We clamber up one of them. It’s about 12-feet tall but there are toe-holds carved into the sides by the loggers that felled this tree so long ago.

Mike McHenry rests his elbows on the surface of the stump. It’s wider than an eight-person dining room table. He runs his fingers over the exposed tree rings tracing back over the tree’s growth history – hundreds of years. He says someday there could be trees like this here again.

MCHENRY: You and I won’t be around to witness it, but hopefully our grandchildren and great grandchildren will be. So that’s a pretty exciting thought.

Ashley Ahearn (photo: EarthFix)

AHEARN: And big fish.

MCHENRY: Big fish too. Big trees, big fish, they go together.

AHEARN: I’m Ashley Ahearn on the banks of the Elwha River.

CURWOOD: Ashley's story comes to us from the public media collaborative, EarthFix.

Related links:

- Check out the piece on the EarthFix website

- EarthFix is a public radio collaborative reporting on environmental issues in the Pacific Northwest

[MUSIC: Led Zepplin “Rain Song” from Houses Of The Holy (Atlantc Records 1973)]

Nicaraguan Canal

Greytown from the air. This is the furthest Nicaragua ever got to a canal—a 2 km canal cut by Cornelius Vanderbilt 150 years ago (photo: Tim Rogers)

CURWOOD: It’s been almost 100 years since the first ship sailed through the Panama Canal. Now, as Panama expands its canal to accommodate bigger ships, another Central American country is looking to connect the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. A deal between a Chinese company and the Nicaraguan government has been reached to build a rival canal. Tim Rogers is a correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor based in Managua and he joins us now by Skype.

ROGERS: Nicaragua's been sort of fantasizing about a canal for almost 150 years in one form or another, and this is an issue that never goes away. It’s sort of a chimera that Nicaragua has been chasing for a very long time.

CURWOOD: Give us a bit of a geography lesson that makes Nicaragua a prime candidate for this.

Tim Rogers on Lake Nicaragua (photo: Tim Rogers)

ROGERS: Well, Nicaragua was actually considered before Panama for the original transoceanic canal. It’s in Central America; it’s one of the more narrow divides of the hemisphere. And it’s got an Atlantic and Pacific Ocean coast. Nicaragua also has an enormous lake right in the middle of it. It’s tempting because the spit of land on the Pacific side is very narrow. Looking at a map, Nicaragua almost makes the most sense for the canal, and that’s what they originally thought 150 years ago.

CURWOOD: But, of course, it didn’t. Panama was a better deal because...?

ROGERS: Panama was a better deal for a number of considerations. One of which was the amount of seismic activity in Nicaragua. Nicaragua is very seismically active, and people who were Panama boosters back at that time played that to their favor by stirring up fears about volcanic eruptions and earthquakes in Nicaragua. It was also very politically unstable, and that also worked to Panama’s advantage.

CURWOOD: Now, tell me about this Chinese company. What role would it play in this project?

Ometepe, Lake Nicaragua (photo: Tim Rogers)

ROGERS: Well, the Chinese company would basically be designing, constructing, managing and operating the canal. Their concession is for 50 years, and they’ve got a 50-year option on top of that. So that could be for the next 100 years. Very little is known about this Chinese company. They’ve very recently formed. They’re called HKND. The HK stands for Hong Kong where they’re supposedly based, although they are also registered in the Grand Caymans. So no one really knows much about them. Their CEO is a gentleman named Wang Jing who is a telecom tycoon in China who apparently has no experience in major infrastructure projects such as the canal - this will be his first.

Possible canal routes, map from previous administration (Image: Tim Rogers)

I should say that when we’re talking about a canal project, that’s really a mega-project, there are really several projects that are all bundled together. The concession that the Chinese firm is getting is not just to build a water canal. It’s also to build a transoceanic railroad that would be called the dry canal. It’s to also build two airports; it’s to build two new deep-water ports on the Atlantic and the Pacific side; it’s to build an oil pipeline across the country. So this is an enormous project.

CURWOOD: What’s the back of the envelope calculation of what this project would cost and who would pay for it?

Nicaragua is known as the land of lakes and volcanoes. Lake Nicaragua, facing the twin volcanoes of Ometepe Island (photo: Tim Rogers)

ROGERS: Both of those are very good questions, and neither one of those has been explained clearly. The government continues to change its calculations almost from one week to the next about how much this is going to cost. The original calculations were about $18 billion, and they’re up to $40 billion already. And who is going to pay for it is also a good question. Nicaragua does not have diplomatic relations with China so there is a lot of speculation and doubt about what the Chinese government role is and will be in this project.

The Chinese government has not made any declarations about the canal so far. If the Chinese government were to partner or offer some financing for this project, it would definitely give a major toehold in Latin America which is something they’re interested in doing. If they were to control an oceanic canal, that would be a major game changer for geo-strategic relations in the Americas.

The rusted remains of Vanderbilt’s dredge is still sitting in the San Juan lagoon 150 years later (photo: Tim Rogers)

CURWOOD: Now, what would be the environmental impacts? What would be the environmental costs of a project like this?

ROGERS: Now that the concession has been approved, the next step will be to start the feasibility study and then move on to the environmental impact study. So none of this has been conducted yet. But some sort of early concerns are that this could really be devastating for the Nicaraguan environment.

CURWOOD: How?

Lake Nicaragua at sunset (photo: Tim Rogers)

ROGERS: Well the concern is that Lake Nicaragua is not deep enough to host a canal of this magnitude, and that it would pollute the lake; it would use up Nicaragua’s water resources. Lake Nicaragua for many years has been considered the future source for Central America’s drinking water. So if they start using it for a canal instead, that plan would go out the window.

CURWOOD: How big is Lake Nicaragua?

ROGERS: Lake Nicaragua is one of the biggest lakes in the world. I believe it’s the second biggest lake in Latin America and the eighth largest lake in the world. I heard one statistic that you could put Puerto Rico inside of Lake Nicaragua and it would still be an island.

CURWOOD: Tim, do a little handicapping for us here. How likely is this deal to go forward?

ROGERS: If history is any indicator of the success of this then it won’t happen. Nicaragua’s been talking about this for 150 years. Nicaragua has had different plans on the table multiple times over the past century, and none of them have really made it beyond paper. Nicaragua thinks at the moment that this is its opportunity, this is its moment in history to sort of reach for the brass ring. And so to talk about this, it was sort of like talking about a world series championship with a Chicago Cubs fan. It’s just sort of really touched...a real sort of collective dream that Nicaraguans have and sort of the promise of alleviating this historic frustration.

Whether or not that’s going to happen I don’t know. What I can say is that the way this project is starting sort of is under a cloud of doubt. We don’t know how much the project will cost. We don’t know who the partners are. We don’t know about the company that’s about to get this concession. We don’t know how long it’s going to take. We don’t even know what the route will be. There are five different routes that Nicaragua’s considering. So right now there are far more doubts than there are answers about this, and so it sort of seems to be getting off on the left foot as they say in Nicaragua.

CURWOOD: Tim Rogers is a correspondent for the Christian Science Monitor. Thanks for taking this time, Tim.

ROGERS: Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Tim Rogers’ article on the canal in the Christian Science Monitor

- Check out Tim Rogers’ online news site The Nicaragua Dispatch

[MUSIC: Bomba Estereo “Bosque” from Elegancia Tropical (Soundway Records 2012)]

Vanishing Point

Bittern sitting on a log (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: The American Bittern is a secretive bird with highly developed camouflage that literally lets him hide in plain sight. Writer Mark Seth Lender had an unusually close and prolonged encounter with a bittern in a pond in Northern Maine, which is rare enough. And then, Mark writes, the bittern showed him something truly extraordinary.

LENDER: Stut-stut-stut stutter step stutter step stop! American Bittern. He’s the one who walks the walk. If you wear scales, if you’re amphibian, if you sit, if you swim, if you skim the surface under his grim gaze, his beak, his bumpy ways - you gonna die, Old Son.

Bittern swimming (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Shhhh! Don’t move an inch: In the high grass of sweet marsh by sweet water, Bittern stands tall. Long neck swaaaaays to the one side, swaaaaays to the other, beak in the air like a stem, like a stalk. He looks out past that killer bill, same as you with your nose in the air, he’s thinking: “I can seeeeee you… You can’t seeeee me.” It’s true: Unless you find that tall grass of American Bittern on the move - stutter step, stutter step stop - you’ll never know the who what where, you’ll never find him at all…

See Old Bittern perched on a stump?

Took a long step in,

And went across the pond.

Slip into the weeds

Like butter through a sieve

Vanish like the wind

Like he waved a magic wand.

With its grassy plumage, the American Bittern can be extremely difficult to spot (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

He didn’t see Bittern

Sittin’ on a log

And it’s one more tadpole

Won’t make frog.

Bittern with a tadpole in its mouth (photo: Mark Seth Lender)

She was lookin’ down -

When she shoulda looked sharp -

And it’s one more minnow

Never get to grow up.

Step stop stutter -

He’s agile as an otter

He can hide in the shadows

He can hide in the light

Every time he goes fishin’

He’s gonna getta bite!

CURWOOD: Mark Seth Lender is author of Salt Marsh Diary. There's a video he took of the bittern he encountered and many photos at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- More about Mark Seth Lender

-

[MUSIC: Jenny Scheinman “Ali Karka Touche” from Mischief and Mayhem (Jenny Scheinamn Music 2012)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the changing climate and its effects on one of life's oldest pleasures - a nice bottle of wine! That's next on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway, for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Horace Silver: Song For My Father from Song For My Father (Blue Note Records 1963)]

Winery Adapting to Climate Change

The entrance sign at Backsberg Estate Cellars. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The National Academy of Science says that thanks to climate change, there will be dramatic shifts in where wine grapes grow over the next 40 years. And that could mean more wine from, say, Missoula, Montana and Surrey, England. But researchers also predict a reduction of 50 percent in land suitable for wine in many places, including the Napa and Sonoma valleys in California, Bordeaux and the Rhone Valley in France, Tuscany, in Italy and South Africa.

With the end of apartheid 20 years ago, the Cape region of South Africa put its people and its Mediterranean climate to work and built a billion bottle a year wine industry that now exports eight times as much as it did just a dozen years ago. And South African wine makers are taking the climate threat seriously, with associations offering advice on how wineries can both mitigate and adapt to climate risks by becoming more sustainable, managing water and lowering carbon footprints.

[HEAVY RAINFALL]

CURWOOD: It’s raining on and off on a winter day in May when I stop by the Backsberg Estate Cellars. The wine farm lies on the lower reaches of Simonsberg Mountain near Paarl and Stellenbosch, a 40-minute drive from Cape Town. In 2011, Greenpeace gave Backsberg an award for Climate Change leadership, after it became the first winery in Africa to go carbon neutral. It’s a matter of pride for Simon Back, a young man with bright inquisitive eyes and an easy manner, who manages marketing and exports for the vineyard. He says the weather already seems less stable.

Simon Back (Photo: Backsberg Estate Cellars)

BACK: We’re at the end of May now and May was a relatively dry month so it feels like all the rain is coming in the space of a couple of days. There’s a huge amount of rain that’s come in the last 48 hours and there’s more to come in the next few days.

CURWOOD: So more weather volatility, that’s what you’re seeing.

The vineyards of South Africa’s Backsberg Estate Cellars. (Photo: Backsberg Estate Cellars)

BACK: It would appear so on the surface, definitely. I can’t really claim, at least in the short time that I’ve been working at the farm, that I can say definitively that there has been a rise in temperatures but I can definitely see a changing in weather patterns. So for instance this year, the harvest was almost two, three weeks later than usual. Normally in the past we could more or less pinpoint to the day exactly when we were going to harvest a particular block.

CURWOOD: And there is a long record to compare today's timing against. As the rain takes a break, we settle in for a chat on the veranda of the winery restaurant where Simon Back tells me this land has been in his family for four generations, since his great-grandfather emigrated from Lithuania.

BACK: My family is Jewish and they were fleeing some of the interesting stuff going on in Europe at that time. He got on a boat and arrived in Cape Town in 1902 and a few long years of lots of work and probably some tears along the way, but he managed to own a butchery in a nearby town called Paarl. He worked at the butchery for a few years. In 1916, someone came into the butchery and said, “Hey, do you want to buy a farm?” He saw it as an opportunity. He sold his butchery and bought what is today Backsberg.

CURWOOD: So, this wine farm has been here for nearly 100 years and I gather you’d like it to be here for another 100 years at least.

BACK: Exactly, I’m the fourth generation and hopefully there will be many more after me.

CURWOOD: There’s a challenge though. This recent paper from the National Academy of Sciences says the area that South Africa is going to be able to grow grapes for wine is going to shrink by half over the next 30 or 40 years. What does that mean for you here?

BACK: I think climate change is very much a reality and a challenge that the South African wine industry is going to have to face and come up with ways of managing over the next few years.

CURWOOD: So, when you come into your estate there’s a big sign that says South Africa’s first carbon neutral vineyard. What does that mean?

BACK: In 2006, mostly my father but really the rest of the company, really sat down and said, “What are we responsible for as a winery and as a business? What is our impact on the environment?” We as a family and as a business have enjoyed the fruits of the land for many years. It was this feeling that we now need to A, take account and B, reverse the clock on some of the impacts that we’ve had. What we’ve really tried to do here is produce great wine, which is something we are not willing to compromise on but do it slightly differently and really look at what we are doing and making reductions in the emissions, reduce our impact on a day to day basis.

CURWOOD: OK, so let’s walk around and you can show us some of these things that you’ve been talking about.

[WALKING]

BACK: Should we talk a little about what’s going on in the restaurant?

CURWOOD: Sure.

[RESTAURANT ATMOSPHERE]

The restaurant at the Backsberg estate. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

BACK: If you look at the furniture and roof within the restaurant we’ve tried to give a kind of second life to our oak barrels. The wine industry is effectively cutting down trees in France that are perhaps 300 years old. We’re turning it into a barrel; we’re using the barrel for between five and seven years and then effectively it’s a waste product. What we’ve tried to do here at Backsberg is make furniture out of it. We’ve got tables, we’ve got chairs and our roof is covered with oak staves.

CURWOOD: Well, you have a full restaurant now; are you selling this furniture elsewhere now?

BACK: Yeah, we’ve got a full-time carpenter who makes a lot of this furniture and we’re trying to sell it as well.

CURWOOD: He then leads the way into what seems to be a mostly empty warehouse, scented with fresh wine.

[CELLAR ECHO]

BACK: So now we’re kind of in the heart of the cellar and this is where, over harvest time, it’s a very busy area where the fermentation happens and the pressing of the grapes happen. So if you look within a cellar there’s a massive demand for electricity and that electricity is primarily used for refrigeration and controlling the fermentation.

CURWOOD: And the electricity is used to cool and pump and…?

BACK: Exactly so; in the case of red wine we want to control the fermentation in degrees Celsius at around between 27 and 29, and in white wine around 11, 12, 13.

CURWOOD: The way you’re supposed to drink it.

BACK: Exactly. [LAUGHS] So the things that we’ve done here is that we’ve tried to sort of manage the electricity usage here. And in the case of red wine we’ve figured out that, and again this is not really so much a technological advancement as much as it is just using some of the information out there. We’ve got a large irrigation dam just up the hill here and we realized that water beneath a certain depth was a constant 15 degrees and as I said with the red wine fermentation, that has to happen at 27 degrees and so we realized we could actually just use dam water below that level in managing the fermentation. And so with all our red wine now we’re hardly using any electricity to control the fermentation. In the case of white wine we couldn’t use the dam water because the fermentation happens at a temperature below that of the dam water, but we can use that initial cooling and just supplement that to control the white wine fermentation.

CURWOOD: Not only do they save on cooling costs in the summer heat, no pumps are needed to drain the fermentation vats as they are mounted on a balcony where the wine can be fed by gravity into the barrels. Simon estimates the vineyard has cut its electricity consumption by 20 to 25 percent by harvesting the low hanging fruit of efficiency. And for the bulk of remaining energy needs they’re using biofuels.

[WASHING OAK BARRELS]

CURWOOD: A biomass boiler makes hot water for all kinds of applications, including the cleaning of the oak barrels used to age the wine.

[WATER BLASTING]

CURWOOD: The fuel for the biomass boiler is free.

BACK: Right now we have a partnership with a sawmill down the road and we’re using a lot of their waste cuttings and sawdust, which we’re feeding our biomass boiler with.

[BIRDS CHIRPING OUTDOORS]

CURWOOD: But just in case the sawmill stops giving away its waste cuttings, Backsberg wants to be prepared.

BACK: So, we are looking at all sorts of ways of actually growing our own biomass here on the farm itself. And to that point, if you look over the field here what you see growing there is actually prickly pears. And that is a potentially huge source of biomass that we can potentially dry and feed our biomass boiler with. And one of the fantastic things about this plant is that it’s very hardy and doesn’t require a lot of water.

The Back family hopes prickly pear cactus will be a source of biofuels for them in the future. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

[WALKING]

CURWOOD: What about putting, say, solar panels here or windmills?

BACK: Both of those, solar and wind, are becoming very interesting. Up until recently, solar has just been too expensive but the last couple years, even the last year, the prices have come down dramatically and there’s even now a rebate that’s available so we are seriously looking at putting in some solar to add into the mix of what we’re doing.

Wood scraps from a nearby lumberyard serve as a source of fuel for the vineyard today. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

CURWOOD: And windmills?

BACK: Unfortunately, we don’t have sufficient wind over the whole duration of the year to make it a viable proposition so unfortunately, wind isn’t going to work for us at this stage.

CURWOOD: But you do have plenty of sunshine.

BACK: We do have plenty of sunshine, and us on the farm, and South Africa in general is a huge resource as far as that goes. The other thing we’ve done as far as offsetting emissions part is where ever we…on small parts of the farm where it doesn’t make sense to grow vines, we planted trees. Here before you you can see an array of trees which is part of offsetting our carbon emissions. If you drive around the farm you’ll see little pockets of trees everywhere.

[CAR DRIVES BY]

CURWOOD: And Backsberg also sponsors the planting of trees elsewhere in South Africa to make sure they have offset all their carbon emissions. This vineyard constantly looks for ways to become more sustainable. They’ve planted acres of blueberries to diversify their crops, and they have a gleaming tower of tanks devoted to an experiment of making biodiesel. They’ve also expanded their water reservoirs, as well as reusing their gray water. And under what looks like a large greenhouse frame, they are working to turn their waste cardboard cartons into an asset.

BACK: So, right here where we are standing now, you can see the beginning stages of a project which involves farming with earthworms. We’ve got a lot of waste carton from the winery, which we are trying to get rid of and worms really love to eat the carton. Basically, what happens is on the one hand we’re getting rid of the carton and two we’re having some amazing compost as well. And the other thing is that you can actually harvest the worms and mash them up and dry them and get protein. And with the protein you can do a number of things as well, in terms of actually just selling it in the form of protein.

Worms turn cardboard waste into rich fertilizer. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

CURWOOD: Who would buy worm protein?

BACK: A lot of fish farmers would use protein and so that’s going to be one of the shortages in the world going forwards, if you look at how our seas are being overfished. There’s going to be a big shortage on the protein front I think.

CURWOOD: So, you apply the compost as fertilizer to your vines?

BACK: Exactly, so we’ll take the compost from this and put it back into the vineyards and that will hopefully contribute to having healthier vines.

[DIESEL ENGINE]

CURWOOD: So, where are we off to now?

BACK: I’m going to take you on a tour of the farm and specifically show you the lyre trellising system that we put in place as well. We are starting to roll it out over the farm when we plant new vineyards.

The lyre trellising system at Backsberg Estate Cellars. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

[HAND BREAK]

BACK: Shall I turn the car off?

CURWOOD: Yeah, we’ll get out for a moment.

Simon Back shows Steve Curwood the lyre trellising system. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

[DOORS OPEN, WALKING]

CURWOOD: So, what are we looking at here now?

BACK: So, this is a block of sauvignon blanc that we are looking at and the interesting thing that I want to point out is that it’s quite a different trellising technique to your standard vertical straight line planting system. What you’ve got here is the lyre system, basically you plant them closer together but then you train them left and right up into a kind of Y shape and what you have here is kind of a double hedge so the widths of the rows are wider so you are driving up and down per hectare effectively less but you’ve got more or less the same vineyard canopy space. It’s a real win because you’re saving on irrigation pipe, you’re saving on wire, you’re saving on polls, and you’re driving in the vineyard less.

CURWOOD: Can we walk up just a little bit?

BACK: Sure.

[WALKING]

BACK: If you look at the slope there across the way there’s nothing planted to vine there and this section of the farm going down into the valley is an area we’ve set aside for the preservation of the fynbos, which is the kind of natural vegetation of the area. We are part of a program run by the WWF called the biodiversity and wine initiative as part of that we’ve set aside 10 percent of our land holding for the preservation of fynbos. And within that program we are a so-called champion of biodiversity. I think there are 20 wineries or so in South Africa that have gotten that status.

CURWOOD: So what creatures are here because you’ve set aside this land?

BACK: The great thing is that we’ve seen an incredible increase in bird life. For instance, every year we have a bird club come and visit and document all the bird life on the farm and we’ve seen a number of different birds come back to this area...and small buck. It’s been really amazing to see a kind of rejuvenation of the area.

CURWOOD: And this is no small matter. Without conservation reserves, mature producing vineyards offer poor habitat value for native species.

[WINE TASTING ROOM]

CURWOOD: Just before our final stop on the tour - the wine tasting room - we meet Michael Back, Simon’s father. Michael is the third generation of Backs to grow grapes on this land and the driving force behind the innovations Simon showed me.

Michael Back (Photo: Backsberg Estate Cellars)

M. BACK: I’m the chief cook and bottle washer. So, I’ll sign the checks or I’ll shovel the you know what. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Why did you decide to try to make your vineyard climate neutral?

M. BACK: I think it comes from a long way back. If you’re in the agricultural sector you have access to big equipment so when a big tree is in your way you don’t need to work around it. You just push it out of the way. One day, 15 or more years ago, I was driving around the farm and I thought, hang on, we’ve actually done a lot of damage to the property and we need to start to slowly rebuild it back. That’s when the penny dropped that you can farm, you can be commercial, but you can be concerned about the environment at the same time.

CURWOOD: We head into the wine tasting room, complete with oak barrel furniture, the Backsberg Estate Cellars' whole suite of over two dozen fine wines, including some special reserves and several gold medal winners. Along one wall there’s a group of wines that’s been a real hit with the hiking and biking crowd in South Africa, called Tread Lightly.

BACK: It’s a range of wines that’s in fact bottled in PET, so plastic, if you will. Wine connoisseurs might be shocked at this notion but in fact there are many benefits to bottling a wine in PET. First of all, the bottle itself weighs about 50 grams, which if you compare to a glass bottle weighs 450 to 500 grams. You’re talking about a tenth of the weight. Imagine how this gets multiplied out through the supply chain. The shipping of the bottles to the winery and us exporting the wine around the world - there’s massive savings as far as fuel and emissions go.

CURWOOD: So what about the quality of wine in these plastic bottles?

BACK: The wine is really good quality. In fact a number of the wines have picked up some awards, so that’s great news. I think the only thing you have to be aware of is that wines in PET generally at this point in time are not going to keep for more than two years. So, if you’re intending on cellaring wines for 10 to 20 years, then it’s not something you maybe want to do in the case of PET.

CURWOOD: So, you better drink it right up.

BACK: Yeah, you better drink it right up, which I know in my case is not a major problem!

[LAUGHS]

[BIRDS CHIRPING OUTDOORS]

Tread Lightly is the Backsberg wine sold in plastic bottles. It’s reportedly been a hit with hikers and bikers. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens Curwood)

CURWOOD: And from what I tasted with Simon Back at the Backsberg Estate Cellars it wouldn’t be a problem for me either. Backsberg and other sustainable wine estates are being closely watched for clues as to how well the growers of this finicky crop can cope with the increasingly volatile climate with extremes of heat, drought and rainfall. And who knows? While there may be some territory that simply becomes totally unsuitable for wine production, good management may allow vineyards like Backsberg to continue to succeed, and serve up plenty of fine and delicious vintages to enjoy in the years to come.

Related links:

- "Climate Change, Wine and Conservation " in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences

- Vinintell's "Future Scenarios for the South African Wine Industry Part One-Climate Change (May 2012, Issue 12)

- Backsberg Estate Cellars

- Cape Chameleon 2011 article about Backsberg

[BIRDS CHIRPING OUTDOORS]

[MUSIC: Abdullah Ibrahim “Mandela” from Water from An Ancient Well (Blackhawk Records)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Poncie Rutsch, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. This week, we say farewell to Alicia Juang - thanks for all your hard and cheerful work, and we welcome a new intern, Erin Weeks. We had engineering help this week from Dana Chisholm. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth