January 17, 2014

Air Date: January 17, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Risky Business

View the page for this story

Billionaire and green activist Tom Steyer has partnered up with former NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg and former US Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson to form an organization called “Risky Business.” Steyer tells host Steve Curwood the mission of the organization is to quantify the growing risks of climate change. (12:30)

Bad Data for Bad Water

View the page for this story

There’s no federal standard of safe exposure to MCHM, the chemical that contaminated the drinking water in the Charleston, West Virginia Region. Environmental Defense Fund scientist Richard Denison explains to host Steve Curwood that the West Virginian authorities are relying a single study and a lot of guesswork to say what level of MCHM is safe in drinking water. (06:30)

How Safe is Your Lipstick?

View the page for this story

For many women and girls, wearing make-up is essential. But Youth Radio's Joi Morgan started to wonder what exactly was in the bubblegum pink lip-stick she loved to wear, and when she investigated, she got some surprises. (05:35)

Beyond the Headlines ‑- Noisy Oceans and Wind Power in Spain

View the page for this story

In a trip beyond the headlines today, Peter Dykstra of Dailyclimate.org and Environmental Health News, ehn.org, discusses with host Steve Curwood how wind power reigns in Spain, how the oceans are getting noisier, and recalls the inspiring environmental words of Richard Nixon in the State of Union speech 44 years ago. (04:45)

Navy Personnel Claim Radiation Sickness From Fukushima

View the page for this story

More than 70 people--sailors, marines and their offspring have sued TEPCO, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, for not warning the US Navy that its ships were sailing into radioactive plumes when it responded to a call to help after a tsunami caused the Fukushima nuclear reactor melt down. Host Steve Curwood talks with Navy Lt. Steve Simmons, who learned of the risk too late to avoid drinking contaminated water, and Simmons's lawyer, Paul Garner. (06:35)

Life in Chernobyl and Fukushima

View the page for this story

Chernobyl, Ukraine and Fukushima in Japan were the sites of the world's two worst nuclear disasters. Years later some residents choose to stay in the affected communities instead of moving. Michael Forster Rothbart tells host Steve Curwood about his new photo documentary showing the lives of ordinary citizens that remained behind. (09:30)

BirdNote® -- Peregrines and Merlins and Gyrfalcons

View the page for this story

The weather outside may be frightful, but as Mary McCann explains in today's BirdNote®, winter's a good time to see some of our most dramatic raptors. (02:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Tom Steyer, Richard Denison, Peter Dykstra, Steve Simmons, Paul Garner, Michael Forster Rothbart

REPORTERS: Joi Morgan, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. A billionaire gives up his Wall Street job to focus on the environment, spending big to stop the approval of the Keystone XL pipeline and move business investment and the national dialogue away from fossil fuels.

STEYER: In my opinion, I don't think there's any question. Either the scientists don't know what they're talking about or as a society we have to start to make different decisions about how to generate and use energy.

CURWOOD: A conversation with green champion Tom Steyer. Also chemical safety…probing exactly what is lurking in the lipstick that fashion conscious women are painting on their mouths each day.

HAMMOND: We were looking at eight metals and what we particularly found were that cadmium, chromium, manganese and aluminum were present at levels that could actually rise to the level of some concern.

CURWOOD: We'll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The

Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Risky Business

Keystone Protest in Washington DC (photo: Tar Sands Action)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Tom Steyer isn’t your typical environmental activist. Nor is he your typical Wall Street billionaire. The founder of Farallon Capital has mostly dropped out of the investment game to become a warrior in the fight against climate change. His weapons are dogged determination, an enormous checkbook, and access to some of the most powerful people on the planet. Tom Steyer recently joined with former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg and ex-Treasury Secretary Hank Paulsen to found Risky Business, an organization that quantifies the economic risks of climate change.

We sent an audio engineer to Tom Steyer’s office in San Francisco to record this interview, but sadly before she could send the recording to us, her gear was stolen from her car, leaving us just with the phone connection. But you should be able to hear him just fine. Tom Steyer, welcome to Living on Earth.

STEYER: Thank you for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So tell me, why did the three of you come together to start Risky Business?

STEYER: Well, I think that all three of us were concerned that we frame the energy and climate issue in the United States in a thoughtful and responsible way, and we thought that together we were stronger than apart because we had different political affiliations and different backgrounds, and we live in different parts of the country. We felt as if we were going to try and address a national issue with people who are geographically and politically dispersed.

CURWOOD: Now how does climate change alter the investment and business landscape in this country, do you think?

Tom Steyer (photo: Next Generation)

STEYER: I think that when people are making investment decisions what they’re trying to do, to a very large extent, is to anticipate and forsee all the possibilities in the future. So when we talk about a dramatic change to the natural environment, you’re talking about something that is going to change in some ways that we can predict, and in many ways that we can’t predict, outcomes of how people are going to live and how economies are going to work. I think businesses are already taking into account the changes that may occur and will occur in the natural world, and also trying to anticipate governmental responses to those changes. So in thinking about what we’re doing in Risky Businesses, we’re trying to set a framework where we agree on kind of what’s likely to happen so that then, subsequently, we can talk about what we should do about it.

CURWOOD: So, fossil fuels have long been considered sure bet stocks, but at this point, in your view, how prudent is it to be investing in fossil fuel stocks from an economic perspective?

An oil pipeline in Alaska (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

STEYER: [LAUGHS] Well, I think that the question for fossil fuel companies that have decades of reserves to produce is whether the way that we generate and use energy is going to change over those decades, and to the extent that there’s a lot of value put on the out years, then the question is, “is the world going to have changed enough that for some reason the way that we’re used to generating and using energy will have to change?" If that’s the case, then you got to include that in your investment thinking, your projections of the future.

CURWOOD: And what do you think is the answer to that question?

STEYER: I think there are only two possible outcomes: either all the scientists are wrong or we’re going to have to generate and use energy differently. The reason we’re doing Risky Business is to try and show the different scenarios that can happen so that people can start to think about how they should anticipate the future differently. So in my opinion, I don't think there's any question: either the scientists don't know what they're talking about or as a society we have to start to make different decisions about how to generate and use energy.

CURWOOD: Now, rather than an investment response, we’ve seen a social response on this investment question, if I could put it that way, with the fossil fuel divestment movement picking up steam around the country. What role do you think divestment can play in the climate change fight?

Keystone protesters marching in Washington (photo: Ben Schumin)

STEYER: Well, I view divestment as primarily a political statement and an ethical statement and a moral statement. And let me just define that for you for a second, which is this: if a college endowment divests $3 million worth of Exxon stock in the real world does that change the cost of capital for Exxon? I would argue no, that is de minimis change in a huge capital market. I think something else is going on, which is without trying to demonize fossil fuel companies - because I do believe that the actual answer to the way we will generate and use energy in new ways will be created and promulgated by business - the point of a university divesting is to make the statement that we have to make a change. That’s the point of divestment is, for institutions which have high ideals to gird their loins and say it is no longer OK for us to continue with business as usual, as a society we need to confront this and do what we do best, which is rise to the challenge and come up with innovative solutions that will actually make us better off in the long run.

The fossil fuel divestment movement has taken hold around the country. Tom Steyer says divestment is an important moral statement (photo: James Ennis)

CURWOOD: By the way, I think you’re on the board of one of your alma matters, the Stanford B-school. Have you offered any advice about divestment there?

STEYER: We have talked about it, and Stanford has been studying it. I have actually funded two centers at Stanford to study and work on new energy solutions and climate change. So the university is definitely engaged in that fight, and they are trying to find the best ways to try and lead in it. They have not divested, and it is something which is under discussion and evaluation.

CURWOOD: What about your own personal holdings? What do you have in terms of fossil fuels these days?

STEYER: I have done that, I mean we have invested for 30 years across the spectrum of investments, and I have been working since I have left Farallon to try and make sure I don’t have fossil fuel investments because I actually feel that it’s important to be consistent in what you do, and I feel that for me to be sitting here advocating the change for everybody else, I have to already have made that change myself.

CURWOOD: So one of the largest fossil fuel investments that sits on the board right now, of course, is the Keystone XL pipeline and you put a lot of money into opposing Keystone. Why is this such a big issue for you?

STEYER: If you examine what’s really going on with that pipeline, it is enabling a remote and gigantic fossil fuel reserve that is very dirty to come to the world market. It is decades of production, and it’s the kind of thing which is going to be very, very difficult or impossible to turn off. So it’s a perfect example of where business as usual will lead us to a place that could well, you know, be extremely difficult and painful, and therefore to allow it in the first place is a big mistake.

CURWOOD: So, Tom Steyer, you’ve made a lot of money on Wall Street, but I wonder how many billionaires have gone to the Mall in Washington [DC] to speak out at a protest march the way you did in the Keystone demonstration last year.

[CHEERS]

RECORDING OF STEYER ON MIC: We can’t afford 40 more years of dirty energy.

[CROWD YELLING “NO”]

RECORDING OF STEYER ON MIC: We can’t afford the droughts, the storms, the disasters...

[CROWD JEERS]

RECORDING OF STEYER ON MIC: And most of all, we can’t afford not to build a cleaner, cheaper, more secure energy system.

[CROWD CHEERS]

CURWOOD: Well, you got a lot of applause there, Tom Steyer. How did it feel to give a speech like that?

STEYER: [LAUGHS] Well the funny thing - I'll say two things about speaking at the Mall, it was a really, really cold day, and I tried to keep my remarks as short as possible because people were freezing, and second of all, my then 21-year-old daughter had come down from college to listen to the speeches, and I was extremely intent on trying to say something that I thought was both true and positive and forward thinking, thinking of her and the people of her age and trying to represent our generation in speaking about what is good and how American democracy really works, which is when people confront our problem they come up with new ideas and positive ideas. I wanted to make sure she knew that I and the rest of our generation was going to do that.

CURWOOD: Tom, why have you made this issue the primary focus of this phase of your life?

STEYER: Well, I think that...it’s funny...Keystone has a huge, and we discussed it, impact from a substance level, and it also has a huge symbolic impact. The United States of America is arguably the leading country in the world from a political standpoint and an economic standpoint, and when we make decisions people watch very closely and they take cues from it. In addition, this is very specifically a global pollution problem. We can’t solve this by ourselves. So if you’re going to lead a coalition, or participate in the leadership of a coalition, it’s really important you have some credibility to do the right thing. There’s going to be a big international climate conference in Paris, in December of 2015. It’s very important that good things come out of that, and for us to lead, we have to basically say, "we’re willing to make the hard decisions, we recognize the situation, and we’re doing the right things, and that’s why we have a right to encourage you to do the right things as well, so we can get on a path to sustainability as soon as possible". So, therefore, when we think about Keystone and say, “oh we can just do the wrong thing,” and then we can go to everyone else in the world and say, “but you must do the right thing,” I don’t think that will wash for one second.

CURWOOD: You know, historically, policy hasn’t really solved things. We knew slavery was wrong, but there was a social movement. The rights of women, again, there was a social movement. Civil rights, a social movement. What role, if any, do you feel you need to play in the social movement to change the perspective on the urgency of the climate question?

STEYER: Let me say this: we have been involved in a number of campaigns inside California and outside California, and it is absolutely clear to us that for this to get political momentum, the understanding and concern and urgency must be shared across a very broad part of society. And in fact, what we’ve seen surprises most people because they have, in my mind, cliched images of who cares about energy, climate and the environment.

The truth is that across the United States, and very definitely in California, the ethnic group that cares the most about the environment is Latinos, number two is Asian Americans, number three is African Americans. The fact is we need a broad base group not limited to the people who necessarily label themselves as environmentalists or are labeled as environmentalists, that is definitely bipartisan and includes both organized labor and business groups. Until that happens, we won’t have enough political oomph so that elected officials feel like the time has come when we absolutely need to act.

CURWOOD: By the way, you didn’t mention faith-based groups in those movements. Any role here for them do you think?

STEYER: Absolutely. I speak at churches and places of worship fairly regularly, and I love to do it because my feeling is that people of faith see this thing in two very powerful ways: one is that it is incredibly important to protect what God has given us, and second of all, I think people feel very strongly that we must protect the poorest among us. And they are under the - in my mind, correct assumption - that people who will bear the cost of this the most will be the poorest people. And so I think, faith-based groups are people who respond, in my experience, very emotionally and powerfully to this.

CURWOOD: Tom Steyer is the Co-founder of Next Generation and one of the Co-Chairs of Risky Business. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Tom.

STEYER: Steve, it's a pleasure. Nice to meet you.

Related links:

- Read Tom Steyer’s bio here

- Check out Tom Steyer’s newest initiative, Risky Business

- Risky Business just announced the full committee of people who will be examining the economic costs of Climate Change

[MUSIC: Donny Hathaway “Valdez In The Country” from Extension of A Man (Atlantic Records

1973) Donny Hathaway passed away way too early on 01/13/1979]

CURWOOD: Coming up...why regulators really don’t know if it is safe to drink the water in

Charleston, West Virginia. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Allen Toussaint: “Blue Drag” from The Bright Mississippi (Nonesuch

Records 2009) Happy Birthday Allen Toussaint 01/14/1938]

Bad Data for Bad Water

Members of the West Virginia National Guard’s 1257th Transportation Company, along with members from the City of Mt. Hope and the Summit Bechtel Reserve have been working together drawing from the water supply at BSA complex in support of Operation Elk River. (photo: US Army)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The January 9th leak of the toxic chemical

MCHM near the intake of the water supply for the Charleston area of West Virginia forced

hundreds of thousands of people to rely on bottled water to drink, cook and wash. But even after

the authorities declared that where there was less than one part per million of MCHM in the water, it was safe to drink and shower again, folks showed up in emergency rooms complaining of itching,

eye irritation, stomach pain, vomiting and diarrhea. It turns out that there is no federal standard of

safety for exposure to MCHM, and public health officials in West Virginia made their decision

largely on the basis of guesswork. Richard Denison, Senior Scientist at the Environmental Defense

Fund, joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

DENISON: Thank you, Steve. Great to be back.

CURWOOD: So how safe is it to drink this water with this one part per million of MCHM in it?

DENSION: Well, the answer is, we really don’t know, and the reason is that one part per million level was set using apparently the only available study, which has still not been publicly released, but was a study that only examined how much of this chemical was necessary to kill a rat outright. And we’re not talking about people drinking this water and dropping dead, we’re talking about likely much more subtle kinds of effects.

CURWOOD: So how exactly did they use the results of that test for lethality to set what they say is

a safe level for drinking water?

DENISON: Well, we don’t know all of the details because the officials in the state and at the

federal level that did those calculations have been unwilling to make them public. What we surmise

from the press reports that cite those officials is that they took that acute lethality study, and they

applied a series of uncertainty factors to account for the fact that it was a study done in rats and

people might be more sensitive. The most sensitive individual, like a child, might be much more

sensitive than a healthy adult. Then they attempted to apply an extrapolation factor to account for

this use of the lethality study to predict other kinds of effects, although apparently only a small

adjustment was made there.

The problem with all of that is the starting point of the calculation is wrong in two ways: one, it’s a lethality study when we’re really talking about other kinds of effects, and two, they didn’t use a study that identified the lowest dose at which an effect was seen and then adjust accordingly from there. They used a study and picked the median value, in other words, the dose of this chemical that would kill 50 percent of animals exposed to it in a very short period of time. And those are departures from standard practice in risk assessment, and it means that I have no confidence if that one part per million level is safe. I want to emphasize, I’m not saying that this chemical is unsafe. I’m saying we don’t have enough data to know whether it’s safe or not.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, people who are in the areas that have been given the OK to

use the water say they nonetheless can smell the characteristic locorice odor when they turn on their showers. That indicates, obviously, some presence of the chemical, I would say.

Bethany Whisman and Blake Kenney, both of Poca, W.Va., volunteer by handing out cases of bottled water to those affected by the Elk River water contamination on Jan. 11, 2014 (photo: US National Guard)

DENISON: Yes, it does. Now one thing that’s true certainly with some chemicals is that the

amount of the chemical necessary to allow you to smell it is often quite a bit lower than the amount

that would cause a toxic effect. I don’t know that that is the case, one way or the other with this

chemical, because that information has not been provided.

CURWOOD: So what risks does this chemical pose in tiny doses, say down to parts per billion?

DENISON: No idea. No idea because the data simply do not exist, and that is a data gap that can

be traced to the fact that the law that is supposed to regulate these kinds chemicals does not require

them to be shown to be safe to be on the market. That law is the Toxic Substances Control Act that

dates all the way back to 1976, and this chemical MCHM is one of the chemicals that was grandfathered in when that law was passed. It was simply assumed to be safe. I do think that this kind of an incident may help to spur forward the legislation that’s being considered in Congress to reform this Toxic Substances Control Act. I’m hopeful that it will provide greater impetus to getting the debate moving, and getting this legislation moving through Congress.

CURWOOD: In view of what some call the “precautionary principle”, what’s your opinion

of the decision by the public health officials in West Virginia to allow people to start using this

water again at one part per million.

Jeff Heath, of CMS Oilfield Services, puts water in a bucket for a resident affected by the Elk River water contamination on Jan. 11, 2014, at Poca High School in Poca, W.Va. Residents of Kanawha, Boone, Putnam, Lincoln, Logan, Clay, Roane and Jackson counties were told to stop using tap water after a chemical leak contaminated the West Virginia American Water company’s system in those areas. (photo: National Guard)

DENISON: Well, on one level I have some sympathy for them. They’re flying blind here, and

clearly the major disruption of losing residential water for 300,000 people is not to be taken lightly.

So I understand the pressure they’re under. I don’t know what I would do in their shoes, but I think

what we need to be looking at is how did we get into this mess, recognize the fact that any of tens

of thousands of other chemicals might have been in that tank, and had they leaked, we might have been very much in the exact same boat because we have an overall system of regulation here that has allowed these chemicals simply to be presumed safe, and the only time anybody ever looks at them is in a situation like this, and suddenly everyone’s scrambling and trying to cover the decisions they made. This was a disaster waiting to happen. Tanks do leak. Even when there’s good monitoring and containment, accidents happen, and we need to have the information at hand to deal with them in a responsible way, and this example tells us we were far from that situation.

Richard Denison (photo: Environmental Defense Fund)

CURWOOD: Richard Denison is a Senior Scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund. Thank you

so much, Richard.

DENISON: Thank you very much.

Related link:

Read Richard Denison’s blog post about the chemical spill in West Virginia

[MUSIC: Ultimate Spinach “(Ballad Of) The Hip Death Goddess” from Ultimate Spinach (Iris

Music group 2006 Reissue]

How Safe is Your Lipstick?

Joi Morgan wanted to find out more about what was in her lipgloss (Youth Radio)

CURWOOD: Well, given that so many chemicals were grandfathered into use and not tested for

safety at a federal level, some states are taking on the job of protecting consumers themselves. One

of the leaders is California, which has just set up the Safe Cosmetics Program Product Database,

allowing the public to go online and check if such products as makeup contain potentially

dangerous ingredients. This website arrives at a timely moment for Youth Radio's Joi Morgan.

Like many women, buying and wearing the latest cosmetics is almost a ritual for her, but she has

started to wonder exactly what is in those colorful glosses and bright pink lipsticks she paints on

her mouth. Here's Joi.

JOI: One thing I know for sure, my friends and I count on the perfect lip gloss to set off our looks,

whether we’re heading to class or a night out. Right now I’m totally into bubblegum pink. But I

was surprised to learn what's in these tubes!

JOI: Polybutene, Titanium Dioxide...

VOX 1: I've never read the labels, the fine print.

JOI: Stearalkonium...I don’t know how to say that.

VOX 2: I didn't even know there were instructions on the back.

JOI: Mica, Ricinus Communis...Oh I know that one, That’s castor oil!

VOX 3: Yeah it does matter, I mean, it’s on your mouth, meaning you’ll be putting that in your

mouth. Ultimately it's going to affect you.

JOI: Teenage girls spend nearly $14 a month on cosmetics. More than even their 18-24 year old

peers, according to a recent youth beauty market report. That’s one reason why researchers at the

University of California, Berkeley, collected popular lip products from a youth group in Oakland.

Dr. Katherine Hammond, an environmental health scientist, led the investigation tested the lipsticks

and glosses.

HAMMOND: We were looking at eight metals and what we particularly found were that cadmium,

chromium, manganese and aluminum were present at levels that could actually rise to the level of

some concern.

JOI: Consumer advocacy groups and the Food and Drug Administration, the agency that regulates

make-up, have both found lead in cosmetics, but disagree about whether the concentrations are

harmful or not.

HAMMOND: So the fact that these chemicals and metals were there does not surprise me, I had

some suspicion that they might be. On the other hand that they reached the levels that we might be

concerned, that did somewhat did surprise me.

JOI: The Personal Care Products Council stands by the safety of their products. But as a teenager

who wears a lot of make-up, how much metal am I actually exposing myself to?

HAMMOND: On average a person uses it just 2-3 times a day, you know, average is just an

average of many numbers, but nobody’s average right?

JOI: Right. It’s just, I have a feeling I’m waaay beyond average. When it comes to maintaining

my look, it takes more than 2 to 3 touch-ups! I wanted to be sure, so I walked around with a bulky

recorder and mic around my neck, looking like a dork, for a couple of days, capturing every time I

put on my lip gloss.

Testing, testing, testing, testing

[MUSIC: Lipstick: Vybz Kartel “Lipstick Gloss”]

JOI: I was sitting on the couch in my living room, getting ready to walk out the door in the

morning, when I applied a pretty pink punch shade for the first time.

OK, so I'm on the Bart right now and I just had some cookies, and that caused me to re-apply my

lip gloss. This is re-apply number 3. It’s 11:45...

It’s before noon and I’ve already hit the average daily application.

OK, it is 4:10. I just had some ice cream from Rite Aid so I have to re-apply again.

I reached 11 lipstick touch-ups by the end of that Friday night. And on Saturday, when I kept track

again, I reapplied 20 times. Which is the norm for a night out with my girls. But these two ladies at

the hair shop across the street from my office, Rashida and Gracie, stomped my average!

JOI: How often would you say you apply your lip gloss?

RASHIDA: On a good day where I think I’m looking real good, I’ll say, maybe every hour?

GRACIE: Because my profession causes me to talk so much, I am a mother and I talk so much and

I eat. I probably apply my lip gloss every 30 minutes it seems like…

JOI: I guess kids aren’t the only heavy users! How much is too much? I asked the Food and Drug

Administration spokesperson on cosmetics, Tamara Ward.

WARD: One of the things that we’d like our consumers to know is that unlike drugs, cosmetic

products do not receive premarket approval. The manufacturers are responsible for making sure

their product is safe and we will step in when we know that there is an issue with a cosmetic

product.

JOI: Seems like the only directions on the side of my lip gloss are “apply as needed.”

WARD: Well the label is saying “as needed”, so “as needed” is vague but it is the choice of

consumer.

JOI: I get that it’s my choice. At least now, in California the Department of Public Health has

set up a website to actually tell us what's in our lipstick and shampoo. So maybe I’m taking that

information to the cosmetic aisle next time I’m looking for a new shade of babydoll pink lip-gloss

to match the bronzy-gold around my eyes...

For Living on Earth, I’m Joi Morgan in Oakland.

CURWOOD: Joi reports for Youth Radio. Ike Sriskandarajah produced our story.

Related links:

- Check out more stories produced by the young people at Youth Radio

- Personal Care Products Council

- California Department of Public Health

- FDA Info on the Chemicals in Cosmetics

Beyond the Headlines ‑- Noisy Oceans and Wind Power in Spain

Wind turbines in Andalucia in Spain (photo: Manfred Werner)

CURWOOD: Time now, to peer behind the headlines with Peter Dykstra, who publishes the Daily

Climate.org and Environmental Health News. He joins us now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there,

Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: So what have you got for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, how about we start off with a little good news: wind power. Wind power reigns

in Spain. There was a government report, a Spanish government report out that says Spain got 21.1

percent of its electricity last year from wind power. That edges out the number two source: nuclear.

There’s also been an increase in hydropower in Spain, the hydropower because they had a wet

year and, of course, if you’re in Spain, and you have hydropower, the source of hydropower is, of

course, is the precipitation in Spain.

CURWOOD: Ah, yes, how precipitous was Spain about this? I mean, is this conscious, or just a

result of Spain’s bad economy, and the fact that factories aren’t using as much conventional power

these days?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s a little bit of both. The coal and nuclear for electric generation declined

in Spain last year. That’s certainly partly due to the fact that the slower economy needs less

electricity. But Spain has also built windpower in as part of the path out of a bad economy. It’s a

booming business in Spain just like it is in other European countries like Denmark and Portugal.

CURWOOD: So, that’s our dose of good news for the week, that’s Spain’s top source of energy is

wind, but, Peter, I suspect you have some of that other kind of news, huh?

DYKSTRA: I’m afraid so. As we aggregate the news each week at EHN.org, we picked up a story

from a mid-sized newspaper, one that deserves a lot of credit for doing a great job of consistently

covering the environment, that’s the Wilmington News-Journal, the biggest paper in the tiny, very

low-lying state of Delaware. And a reporter there named Molly Murray filed a piece on our noisy

oceans. That’s not a totally new topic, but with marine mammals and fish species so dependent on

sound - they use it for communication and they use it for navigation - the increase in ship noise and

other human activity is a big deal and a potentially big change in the marine environment.

CURWOOD: So the natural ocean is more like being in a library, and now the ocean’s become

more like being in a factory?

DYKSTRA: That’s right. Molly Murray, the reporter, called it the urbanization of the ocean. I

think that’s a pretty apt phrase. Because we’re not just dealing with ship noise, there’s military

activity, including weapons testing, and on the East Coast, off the coast of Delaware, there’s the

possibility of oil exploration using seismic testing. Seismic testing is the use of these immense,

noisy cannons that shoot airbursts at the sea floor, and they read the signals they get back from

the sea floor and figure out whether or not there’s oil beneath that part of the ocean. The scientists

don’t know how much ultimately this noise is going to impact whales and dolphins and some fish

species and all the marine life, but they know it’s going to have some kind of impact so we’ll just

have to wait and see.

CURWOOD: It doesn’t sound good to me, Peter, I have to say. And, well, finally, bring us

something from the environmental calendar, would you please.

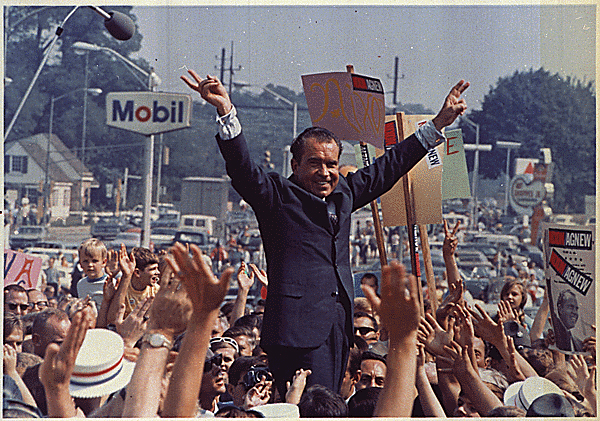

DYKSTRA: You know, one of my favorite environmental things ever said by an American

President: 1970 State of the Union speech, 44 years ago this week, and I quote, “Restoring nature

to its natural state is a cause beyond party and beyond factions. It has become a common cause of

all of the people of this country.” Those words spoken by President Richard Milhous Nixon.

Richard Nixon on the campaign trail in 1968. He used environmental issues to his political advantage, but privately he was scornful of environmentalists (photo: National Archives)

CURWOOD: Richard Nixon. And before he was forced out of office, he signed the Clean Air Act,

the Endangered Species Act, and he founded EPA. But, tell me. Peter, was Richard Nixon really a

tree-hugger?

DYKSTRA: No. Richard Nixon wasn’t a tree-hugger. You've got to remember that he also vetoed

the Clean Water Act. He said it was too costly. Congress overrode his veto and made the Clean

Water Act law. Nixon was a shrewd politician. He needed an issue to blunt the unpopularity of the

Vietnam War which he inherited. He needed to get a little cozier with an environmentally-minded

Congress. But when the cameras were off in the privacy of the Oval Office - and we know this

thanks to that Oval Office tape recorder that later got him in a whole lot of trouble - he gave a very

different view of environmentalists. He met with auto executives, and he said, environmentalists

wanted to make Americans live “Like a bunch of damned animals,” but when the TV cameras were

rolling, he told us to play nice with each other, and with the planet.

CURWOOD: And thank you, Peter, for playing nicely today. Peter Dykstra is publisher of

Environmental Health News and the DailyClimate.org. ‘Til next time, Peter.

DYKSTRA: My pleasure, Steve. Thanks.

CURWOOD: You can find links to all these stories at our webpage at LOE.org.

Related links:

- Follow Peter Dykstra on Twitter

- Peter Dykstra is the editor of ehn.org

- and the dailyclimate.org

- Read more about wind energy in Spain

- Read Molly Murray’s article on the impact of sound on ocean creatures

- In the 1970 State of the Union speech, President Richard Milhous Nixon: said “Restoring Nature to its natural state is a cause beyond party and beyond factions.

[MUSIC: Incognito “Expresso Madureira” from Transatlantic R.P.M. (Shanachie Records 2010)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...revisiting Fukushima and Chernobyl to find out who stayed behind and

why. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the

protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving

the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The

Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for

coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Captain Beefheart: “Semi Multi-colored Caucasian” from Ice Cream For

Crow (Warner Bros. 2006 Reissue) Happy Birthday Don Van Vliet (01/15/1941 – 12/17/2010)]

Navy Personnel Claim Radiation Sickness From Fukushima

Nuclear Power plant at Fukushima Japan (Photo: kawamoto takuo)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In March 2011, a strong earthquake off Japan launched an immense tsunami that set off catastrophic meltdowns at the Fukushima nuclear power complex. Among the first responders on the scene was the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan. It was one of 25 US naval vessels that arrived bringing clean water and other humanitarian aid. But now at least 71 of the Reagan's sailors and marines are suffering with what they are sure are the effects of radiation poisoning, and they're suing TEPCO, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, that they say hid the truth about just how deadly the radioactive plumes were in the air and water. One of those sailors is Lt. Steve Simmons who told us he learned of the danger too late.

SIMMONS: At one point, we had actually brought up into the water filtration system...they had actually come across the intercom system of the ship letting everybody know that we had a little problem that we had actually sucked up contaminants into the water system. I had had already been up, I had already been showered, Ihad already been to the ward room and had a couple glasses of water, and I had filled up my water bottle a couple of times, and that water goes everywhere throughout that ship. It’s what they use for cooking, it’s what they have at every water fountain throughout the ship. You know, honestly, at the time that it happened, I didn’t want to create any panic or hysteria or anything like that, so I just kind of joked about it, shrugged it off, and made some kind of wisecrack about, well, if I ingested any nuclear contamination it’s too late now, what’s done is done...what can I do about it at this point?

_and_two_ships_from_the_Indian_navy's_western_fleet_sail_in_formation_during_a_passing_exercise_in_the_Indian_Ocean_081022-N-HX866-003.jpg)

USS Ronald Reagan (photo: United States Department of Defense)

CURWOOD: So here, we are, three years later, and, as I understand it, you’re experiencing some rather serious health problems. What’s going on?

SIMMONS: I am. We returned from deployment in September and by November my health started to decline. The first thing I noticed, I was actually driving to work, and I blacked out, and I drove my truck up on a curb. And I had gone to see the doctor to see what was going on. They ran labs, couldn’t figure anything out, and from there they sent me up to Walter Reed, to the infectious disease clinic, and same thing, ran labs, couldn’t figure it out, so by this time it was January timeframe of 2012, and by this time I was admitted into the hospital for workup, and I told the intern about the radiation exposure, because honestly, up until that point, I had been healthy. The intern just blew me off.

Lt. Steve Simmons before his exposure to nuclear contamination on the USS Reagan (photo: Steve Simmons)

CURWOOD: What were the symptoms you were experiencing at this point? You had a blackout. What else?

SIMMONS: By this point, I had unexpectedly dropped between 20 to 25 pounds. And my lymph nodes started swelling. From January to March I was running a pretty solid fever as high as 102.9. I was discharged from the hospital the first time for a so-called “sinus infection”, and three days later I was actually readmitted because that’s when my lymph nodes started swelling. During that second hospitalization I was just coming out of the restroom and I stopped and my legs just buckled. And that was when the weakness started. So then I started experiencing weakness in the legs, and it just started progressing further and further. And then shortly after that it got to the point where Summer was actually carrying me up and down the stairs.

Liutenant (jg) Steve Simmons after the Fukushima accident (photo: Steve Simmons)

CURWOOD: These days you’re in a wheelchair, I gather?

SIMMONS: Yes, I spend all my days in a wheelchair now. My muscle weakness just continued to progress up the legs into my arms, my hands, and now the latest issue that I deal with is neurogenic bladder. Now the signals aren’t getting from the brain to the bladder, so now I actually have to catheterize every four hours.

CURWOOD: Navy Lieutenant Steve Simmons. And he's not the only one of the Reagan's former

crew with medical problems.

A second degree burn Simmons received while out in the sun in Hawaii. He suspects that radiation may have intensified the impact (photo: Steve Simmons)

GARNER: Many leukemias, other forms of cancer, unremitting of bleeding of both anally and vaginally, migraine headaches, hair loss...these are all young people, by the way, in their 20s. And they were all basically in the same place at the same time.

CURWOOD: That's attorney Paul Garner, one of the lawyers arguing this case in federal court in San Diego. The lawsuit faces twin hurdles. Not only is it extremely hard to prove environmental causality for illnesses, but there's also a web of jurisdictional complexity that involves the US military, and the Japanese authorities. The court initially dismissed the case on what it termed "political grounds", though it has allowed an amended complaint, due to be filed next month. TEPCO's lawyers argue US courts have no jurisdiction in this matter, and also cite US Navy estimates that the crew of the Reagan was not exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. Meanwhile, attorney Paul Garner has no doubt who's to blame for his clients' medical problems.

GARNER: The people who were operating the boiling mechanism, Tokyo Electric Power Company, they were operating a nuclear power plant which they knew was an accident waiting to happen. So who’s responsible? The people who were operating the instrumentality are responsible. It’s a product liability situation. Here’s the nub of it, OK? This is a man-made disaster. They knew on Day One they were in the process of a LOCA, Loss of Coolant Accident, in the industry. They knew they couldn’t cool down the core reactor number one, we know from former Prime Minister Naoto Kan’s discussion at the Japanese foreign press recently, the core meltdown occurred within five hours of the earthquake of March 2011. The Reagan and the other vessels didn’t arrive until the next afternoon. They should have been warned, just like the rest of the world should have been warned, but the people there kept it quiet. It’s a coverup, and it’s unfortunate that so many people are cooperating with this and that mainstream media just hasn’t really paid attention to this for almost three years.

CURWOOD: That's Carlsbad, California, lawyer Paul Garner. There's more about this suit at our website, LOE.org, where you can aways listen to our show.

Related link:

Read the latest information on this issue from the US Navy

[MUSIC: John Renbourn “Midnight On The Water” from Keeper Of The Vine: The Very Best Of John Renbourn and Stefan Grossman (Shanachie Records 2005)]

Life in Chernobyl and Fukushima

The red specks in this photo are actually traces of radiation hitting the camera lense. (Saha Kupny)

CURWOOD: When any disaster forces people from their homes, those who survive face the choice of eventually returning or starting anew someplace else. But when the disaster isn’t over in a couple days but lingers for generations, and when your home may not be safe, it's a tough choice. People who lived near nuclear power meltdowns in Chernobyl, Ukraine and Fukushima, Japan, have considered those alternatives, and it’s the central question of photojournalist Michael Forster Rothbart’s recent book, Would You Stay? Michael, welcome to Living on Earth.

ROTHBART: Thanks, Steve, it's good to be here.

CURWOOD: So you spent two years living near Chernobyl, and you’ve also spent a lot of time living near Fukushima, Japan, describe those two regions for us.

ROTHBART: It’s interesting. If you go into the exclusion zone in Chernobyl or Fukushima, they actually feel quite similar. There’s just a feeling of small farming towns that have been forgotten and then abandoned. But people have this vision of the Chernobyl exclusion zone being a dead zone, and really, nothing could be further from the truth. There’s a lot of plant life, there’s a lot of animal life, and there’s actually a lot of people still living and working in the Chernobyl exclusion zone.

CURWOOD: Of course, they’re not allowed in the Fukushima exclusion zone yet.

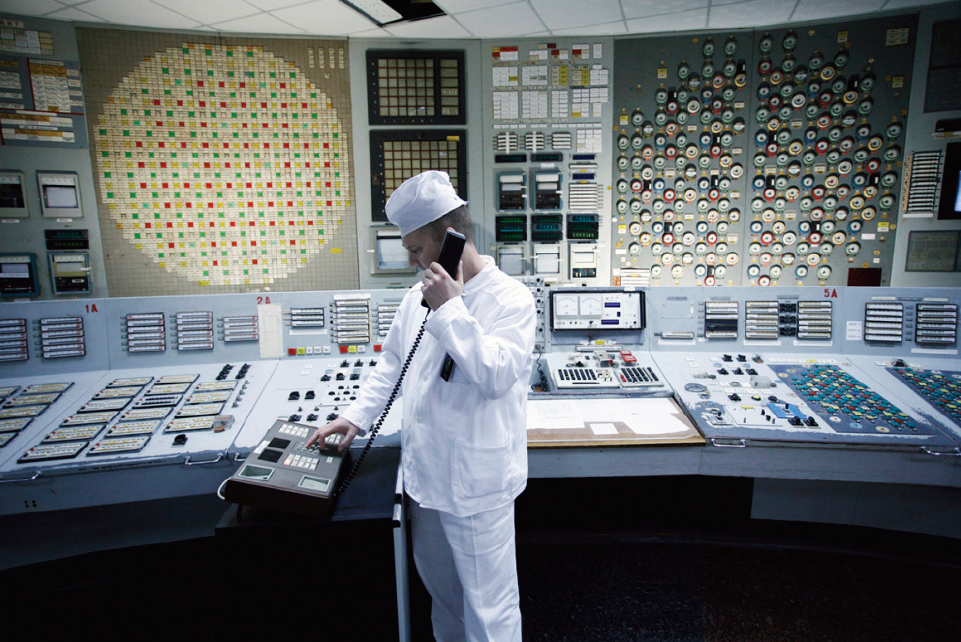

A shift supervisor keeps an eye on things inside the Chernobyl control room. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

ROTHBART: The Japanese government’s very eager to try to get people back into the Fukushima zone, and so they’ve actually designated three different sections of the zone, one section they’re hoping to get people back in as soon as possible, and obviously, the more contaminated zones, it could be decades or centuries before people are let back in.

CURWOOD: When you look in these areas very close to Chernobyl, it doesn’t look like a disaster zone, you say.

The forest around the Chernobyl nuclear reactor appear normal unless you know what you are looking for. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

ROTHBART: If you know what to look for, you can definitely see the signs of radiation, but if I’m just walking through the woods, it looks like a quiet forest anywhere. I spent a lot of time with these biologists who taught me how to see the signs of radiation. For example, pine trees typically have something called “apical dominance” which means that the branch that grows the most is the topmost branch, and just continues to grow up and up and up, and that’s why you get pine trees with narrow triangular shape. But because of the radiation that has stopped them, instead you get these distorted trees with branches going out in every direction, and they look more like shrubs than trees. So that’s just one simple example.

Nina Dubrovskaya (center), Michael Forester Rothbart’s landlord has tea with friends in her kitchen. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

Also, I saw with these biologists I saw birds that had minor deformities. And so there’s actually an interesting scientific debate that’s been going on for years in Chernobyl because one school of thought says that actually humans are the biggest disruptor to natural life, natural habitat. So if you take the humans out of the equation by creating these exclusion zones, actually the animals do quite well. The people in that camp cite there are wolves that have returned to the Chernobyl exclusion zone, there are actually wild horses that were reintroduced there that are doing reasonably well. But the other school of biologists have been doing some very careful studies - bird counts and things like that - discovered there are insects and birds and other animals you’d expect to find there that are not there, and that there’s some direct correlation between the level of radiation in a particular spot and what is living there.

CURWOOD: Of course, Fukushima’s a disaster is a lot younger. What were you able to see in the exclusion zones that was, well, different?

ROTHBART: Well, when I first went into the Fukushima exclusion zone, I was actually amazed how similar it looked to the Chernobyl exclusion zone. The same little farming villages, and a

feeling of abandonment. What’s different in Japan I found...well, first of all, is the scale. Estimates are that Fukushima released between 10 and 30 percent of the amount of radiation as Chernobyl, and Chernobyl actually contaminated an area of about 56,000 square miles, which is roughly the

size of New York state, whereas Fukushima, the area that was contaminated is closer to the size of Connecticut, about 4,500 square miles, you know, maybe 10 percent of the size.

Temporary housing for Fukushima residents displaced after the tsunami and meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear reactor. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about a couple of specific pictures here, Michael. Tell me about Sasha Kupny, he’s a Chernobyl plant worker.

ROTHBART: Sasha’s an interesting character. He’s an amateur photographer, and so although he’s been working at the Chernobyl plant for decades, his dream really was to take pictures, and so we became friends. Sasha Kupny showed me this photograph that he had taken inside the sarcophagus, basically, in the reactor hall, and what’s amazing is the picture, if you zoom in on it and look closely, is you see these green, blue and red dots on the picture, what it’s showing is basically radioactive particles hitting the camera sensor during the one-second exposure. But Sasha described the experience to me. I asked, “Why are you willing to go in here,” and he said to me, “Have you ever climbed a mountain? Well you know when you get to the top and you look around and you realize you’ve gone as far as a human can go?” He said that he had that feeling inside the reactor hall.

CURWOOD: Now there’s another photo. This one’s from Fukushima. I think it’s rather telling. There’s a man who’s straightening bicycles in a bike rack. Why is he doing that?

ROTHBART: One day, I came back from being in the Fukushima exclusion zone, and I got back to Fukushima City, and right outside the train station, there’s a man straightening bikes. And I watched him for a while, and I talked to him, discovered that this is his job, 12 hours a day, seven days a week. It’s basically to take bikes that people park and line them up. He measures them out with his feet so they’re all about 12 inches apart, and he just goes down the line and he makes them all parallel and neat. And I couldn’t help thinking, why, when there’s so many needs for so many people, would you be spending government money, municipal money, to pay someone to straighten bikes. I think the answer is that people have a really strong desire for normality. So even when there’s chaos around you, perhaps even more when there’s chaos is around you, you just want some things to be normal. In this country, we wouldn’t care...a chaotic bike rack, we wouldn’t even notice it. But in Japan, which is a culturally orderly society, people do notice that the bikes are in disarray, and that disturbs them, and so it’s worth it to them to pay somebody to continue to straighten them.

CURWOOD: So how does the culture in Japan compare to the culture of Ukraine in terms of how people have reacted to these nuclear disasters, at the time and following?

ROTHBART: To make some broad generalizations about culture, I’d say the Ukrainians stereotypically are this pessimistic culture, that things are terrible and they’re never going to get better, so let’s just share another bottle of vodka...

CURWOOD: ...and complain, huh?

A worker near Fukushima straightens bikes to make the city feel more orderly and comfortable for residents. (Michael Forester Rothbart)

ROTHBART: ...and complain, all the time, of course. And if you don’t have a good complaint, then you have to think one up. Whereas in Japan, I learned this word called gaman, which translates sort of loosely as stoicism, but it’s much deeper than that. It’s sort of taking pride and being able to survive any situation and very specifically to not complain, not to show people that you’re struggling, to continue living and doing the best you can, and going on, no matter what the circumstances are. It’s interesting now the state government, the prefecture government in Fukushima, is really pushing people to downplay the consequences of radiation, to say, life goes on, things are fine. Let’s promote our city, let’s promote our prefecture and encourage tourism to come back. Because there’s this social pressure not to complain, and not to talk about your fears, people are very close-mouthed, you have to get to know people pretty well before they really start to open up and talk about what they’re afraid of.

CURWOOD: Now that the government is saying, well, you can’t quite move back to the way we thought you could, how are people reacting? How do you think they’re going to react to that news?

ROTHBART: Once people lose faith in their government, it’s really hard to regain it. And I heard this over and over again in Japan, that people said, we trusted the government and they let us down. They lied to us, they misinformed us, they weren’t there to help us, so people lost faith and I think this latest news that people who they’re promising would be able to return may not be able to return is just another nail in the coffin. Like 9-11 in this country, the Fukushima disaster was a watershed moment for Japan where everything changes. And I think decades from now looking back, people say nothing was ever the same after Fukushima.

CURWOOD: So why do you suppose that some people stay, and others go? What’s the typical answer that people would give you when you asked them why they were staying in places like right near Chernobyl?

ROTHBART: I really found two things: one is that people replied to me and said, “well, why should we leave?” It’s hard for us to understand it. We live in such as transient world in this country. We’re so mobile moving every couple of years, but if you live in the same house as your ancestors, it takes a lot of uproot you. I talked to some old woman, for example, who said, “OK, we’ve been through the Nazis, we’ve been through a famine, we’ve been through changes in government, and all these terrible things that have happened to us in the past, we’re not going to leave just because of some invisible radiation. And I think the most basic reason is just because this is home, and home is such an important notion to people. People suffer great difficulties in order to stay in their home.

CURWOOD: Michael Forster Rothbart’s book is called Would You Stay? Thanks so much, Michael.

ROTHBART: It was great talking with you, Steve. Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Would You Stay?

- After Chernobyl

- Michael Forester Rothbart

[BIRD NOTE® THEME]

BirdNote® -- Peregrines and Merlins and Gyrfalcons

Gyrfalcon (photo: Elena Gaillard)

Winter can be a tough time for birds, but it’s also a time when tough birds are on display.

Here's Mary McCann with today's BirdNote®.

[Winter wind]

Female merlin (photo: Tom Grey)

MCCANN: Each season ushers in its own bounty of birdlife. Winter is the best season to highlight North America’s feathered thunderbolts: the falcons. [Peregrine Falcon calling] Northern-nesting species of falcons, like this Peregrine we’re hearing, move southward, closer to their many admiring observers.

[Peregrine Falcon calling]

Hurtling through the air on blade-like wings, falcons rank among the fastest of all birds and the most adept at capturing prey in flight.

One falcon much more prevalent across the U.S. in winter is the Merlin. [Merlin calling] Ten inches tall with a two-foot wingspan, the Merlin chases down small birds from sparrows to sandpipers. Small but powerful, the fearless Merlin will buzz even a huge eagle that enters its airspace.

The majestic Gyrfalcon drifts south in winter to the northern tier of states. [Gyrfalcon calling] Larger than a Red-tailed Hawk, in a direct sprint the Gyrfalcon can overtake even the fastest duck.

The mid-sized Peregrine Falcon nests in some locales across the country, but its numbers are greatest in winter, especially near the coasts. During its dive on a hapless pigeon or Dunlin, a Peregrine may reach an air speed approaching 200 miles per hour.

Peregrine Falcon (photo: Evan Bornholtz)

[Peregrine Falcon calling]

I'm Mary McCann.

CURWOOD: And for some photos of these falcons, dive into our website LOE.org.

[Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Merlin recorded by G.A. Keller. Peregrine Falcon recorded by G. Vyn. Gyrfalcon recorded by A.L. Priori.

Wind Nature SFX Essentials #2 recorded by Gordon Hempton of QuietPlanet.com.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org January 2014 Narrator: Mary McCann]

Related links:

- Listen to this story on the BirdNote® website

- Listen to more stories at the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Pat Metheny “Chris” from The Falcon And The Snowman Soundtrack (Capitol Records 1985)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. This week, we're delighted to welcome two new interns -- Clairissa Baker and Catalina Pire-Schmidt. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth