September 5, 2014

Air Date: September 5, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

World’s Biggest Carbon Trading Market?

View the page for this story

China recently announced plans to launch a national carbon trading market, to help reduce its 30% contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions. Host Steve Curwood discusses the importance and ambition of this plan with Barbara Finamore, the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Asia Director. (08:10)

U.S. Preps for 2015 Paris Climate Summit

View the page for this story

With the Paris climate summit just a year away, the Obama administration is crafting the US plan for action. Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists tells host Steve Curwood that the US could use the climate treaty from 1993 to tighten its ambitions to control greenhouse gas emissions without congressional approval. (05:40)

Rafting down the Unbound Elwha

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

The National Park Service just finished removing the last dams that blocked the Elwha River for over a century in Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. The river now flows freely, open once more for salmon, otters, bears and rafters. Ashley Ahearn of EarthFix takes us for a ride down the river. (04:10)

Freeing the Arteries of the Planet

View the page for this story

The Elwha River restoration project is part of a broader movement to dismantle dams and let rivers run their natural course freely. But there is still a hydroelectric boom in developing countries and as International Rivers Director Jason Rainey tells host Steve Curwood, that’s putting many of the world’s major rivers in crisis. (07:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about the surprising results of a poll in West Virginia, two former coal towns trying to reinvent themselves and the story of the cod war. (05:00)

The Green School

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

In Bali, Indonesia, lies the school of dreams for disaffected school children and environmentalists alike. The Green School’s buildings are made of local grass and bamboo. Gardens scattered around campus mimic a natural forest ecosystem, and it’s on track to get 100 percent of its electricity from renewable sources. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb takes us on a visit. (12:05)

The Quarry

/ Rod ClarkView the page for this story

Writer Rod Clark revisits an old limestone quarry near the village where he grew up, and finds the towering cliffs and hidden caves still a magnet for children today, and full of memories. (02:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Barbara Finamore, Alden Meyer, Jason Rainey

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra, Rod Clark

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. China says it will launch a nationwide carbon market to cut global warming emissions; it’s a matter of self-preservation.

FINAMORE: They forsee an extremely grim impacts of climate change including increasingly severe water shortages, major reductions in grain output, and very heavy vulnerability of their long coastline to sea level rise.

CURWOOD: Also some experts say the mega-dams that generate megapower are destroying a vital resource.

RAINEY: The state of the world's rivers is in grave peril, and there is no international institution looking squarely at the question of: what are the tipping points, how much is enough, can we dam all our rivers for the sake of hyrdoelectricity and still have viable societies here on Earth?

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

World’s Biggest Carbon Trading Market?

Much of China’s carbon emissions is related to buildings, cars and other sources of energy consumption. China’s pilot programs in its regions and its proposed national program can help to reduce this. (Photo: Shinsuke JJ Ikegame; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In a couple of weeks, the UN will hold a high-profile, one-day climate summit among world leaders in New York. And while the U.S. is a necessary leader in tackling climate change, China, responsible for nearly 30% of global greenhouse gases, is the largest emitter and a key actor. And China seems to be facing the challenge. Recently a key senior official announced that the country will introduce a national carbon trading scheme in 2016, building on pilot projects it’s already running. This will help China reach its goal of cutting what’s called the “carbon intensity”, the amount of carbon emitted for each unit of GDP, nearly in half by 2020. Well, to help explain what exactly all this means, we’re joined by Barbara Finamore, Asia Director of the Natural Resources Defense Council. Welcome to Living on Earth.

FINAMORE: Thank you very much. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So China has been running pilot carbon trading schemes in some provinces. How do these work, and how well do they work?

China is currently responsible for 30% of the world’s carbon emissions from human activities. Much of this global warming gas emission is from coal consumption. (Photo: LHOON; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

FINAMORE: Well, China has begun pilot projects of carbon trading in seven regions: that's mostly province-wide, but a couple of large municipalities. So they cover about 700 million tons of carbon emissions per year, but each one of these seven pilot systems is being run in a different way. And so, that's part of the testing phase, to see what works best, and of course the situation in each one of these provinces is different too. China varies tremendously in terms of the level of economic development and also the types of carbon emissions, amount of heavy industry and so forth.

CURWOOD: Give me an example please of how one of these pilot training schemes is working?

FINAMORE: Well, the smallest one is in Shenzhen, which is one of the first free-trade zones in China. So, they are the only one of these regional pilots to include large buildings, which is rather useful because actually buildings are one of the fastest-growing sources of carbon emissions in China because of the amount of electricity that they use, and 80% of China's electricity comes from coal. So that's one innovative feature of Shenzhen. Another is that they're going to allow trading in foreign currencies because they're looking ahead at some point in the future, when these pilot trading programs are indeed a national trading program for carbon in China, might become international, and they might be able to trade with other countries as well.

China is the world’s largest consumer of coal. (Photo: Harald Groven; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: What reduction in carbon intensity is China saying that this new carbon trading scheme will shoot for?

FINAMORE: Well, we don't know, because we don't even know what carbon emission reduction has already been achieved by the seven pilot projects. There's a problem with data transparency; so we don't know what the targets were and how much progress they've been making towards achieving them.

CURWOOD: Now with this carbon market kicking in in 2016, I would imagine this will be the biggest in the world. How do you think this will work really -- just a national thing for China, or will it be a focus for Asian or even world carbon trading?

Air pollution in China due to smog has contributed to health problems. (Photo: Martin Nikolaj; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

FINAMORE: You're right. Once it comes into operation, this carbon trading program will dwarf any other in the world, and there's talk about whether or not at some point in the future these national programs for carbon trading might be linked and allow trading among countries. And there's some, you know, advantages to that because the whole point of trading is to allow companies that have to meet a certain reduction limit to buy permits from another company or country that can reduce them at a cheaper price, and that could result in financial flows, and it could result in a system of overall greater economic efficiency.

CURWOOD: Is this move now something that takes China out ahead of the rest of the world, trying to the curb greenhouse gases? Or are we just looking at an explanation of how it's going to achieve its stated goals?

Barbara Finamore is Asia Director for the Natural Resources Defense Council. (Photo courtesy of Barbara Finamore)

FINAMORE: Well, the International Energy Agency has calculated that if China meets its voluntary commitment to reduce its carbon intensity by 40 to 45% by 2020, it will have made its contribution to the global effort to reduce global warming.

CURWOOD: To what extent you think it's real versus posturing or looking for international approval?

FINAMORE: I think to a large extent it's real. Although it will help China meet one of its goals, which is to increase its international image on climate issues since it is now the largest emitter of greenhouse gas, but China has its own reasons for reducing its carbon emissions and one is the very strong level of vulnerability that China itself has to climate change. Its second national assessment report on climate change in 2012 and it said, they foresee an extremely grim impacts of climate change including increasingly severe water shortages throughout the country, in a country that's already one of the most water stressed in the world, major reductions in grain output and very heavy vulnerability of their long coastline to sea level rise, which would increase its vulnerability to typhoons and to flooding, and also impact the heavy industry that is located along that coastline. So its own levels of climate vulnerability are helping to drive this forward. And besides, China has other reasons for pursuing a transition to a cleaner energy system and one of them is the choking levels of air pollution that is increasingly plaguing the country.

By developing renewable clean energy, China can cut its carbon emissions and meet it’s goal for 2020. (Photo Zeng Han Jun; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: China is still burning vast quantities of coal.

FINAMORE: China burns more coal than the rest of the world combined, so that's right. And so China does see the need to transition to a cleaner energy society and one of the reasons that they are moving to renewable energy at a very rapid pace, is for energy security reasons because they have huge potential in wind and solar, and in fact it is now the largest investor in the world in renewable energy. It has the largest capacity in wind power in the world right now, and the largest manufacturer of solar panels. And it's increasingly deploying that solar energy domestically rather than just for export.

CURWOOD: How do the Chinese plans compare to what the United States at this point is saying it's willing to do?

FINAMORE: Well, that's a good question because the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency under President Obama announced a proposed rule earlier this summer that is the most ambitious effort in the United States to date to reduce its carbon emissions. Now this is still a proposed rule, but it is showing U.S. leadership on this issue as well. And I think in the international arena when the negotiations come up, the level of ambition that the United States is demonstrating is going to help it show leadership to other countries, and the same for China. So I think these are very positive developments in both countries.

CURWOOD: Barbara Finamore is Asia Director of the Natural Resources Defense Council. Thanks a lot.

FINAMORE: My pleasure.

Related links:

- Read China’s 2012 Policies and Actions Plan for Addressing Climate Change

- More about China’s national carbon market, it’s pilot markets and how it might operate with Asia and Pacific markets

- Read about China’s debut of carbon trading schemes in its regions

U.S. Preps for 2015 Paris Climate Summit

The EPA’s new power plant rules have been the Obama administration’s most ambitious climate control effort to date. (Photo: Robert Donovan; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, both China and the U.S. have their eyes on Paris, the host city for a two-week climate summit in 2015 that is expected to produce a worldwide agreement for further cuts in global warming gases. The U.S. is still bound by the UN umbrella climate treaty that the United States Senate ratified back in 1993, and the Obama Administration is apparently poised to invoke that treaty as its authority to act in these upcoming negotiations. And that means that the U.S. could sign on to tighter limits without congressional action, says Alden Meyer, Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists, and he joins me now on the line from Copenhagen. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

MEYER: Thanks, Steve, great to be with you.

CURWOOD: So if the United States wants a strong positive outcome for the Climate Summit in Paris in 2015, it needs to have a plan now. What kind of plan do you think the White House has?

Hurricane Sandy in 2012 brought the reality of climate change home in the United States, but many around the world aren’t impressed with the United States’ actions on climate to date. (Photo: Timothy Krause; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MEYER: Well my understanding is that they are working on a proposal that they will put forward early in 2015 to the rest of the world saying what we can do after 2020. The agreement that’s being envisioned for Paris in December 2015 would involve all the major countries of the world including not just the U.S. and other industrialized countries, but China, India, Brazil and other emerging economies, but it would only be for an agreement that would take effect in 2020 and commit countries to shoot to reduce their emissions by 2025 or 2030.

CURWOOD: How deep a reduction is the White House thinking about making?

MEYER: Well that’s a big question, and the fact is we don’t know. They’re saying very little, understandably, about the specifics of what they’re considering; clearly it would have to be deeper reductions than the current target that’s on the table of 17% by 2020, if it was going to get the credibility internationally with their negotiating partners.

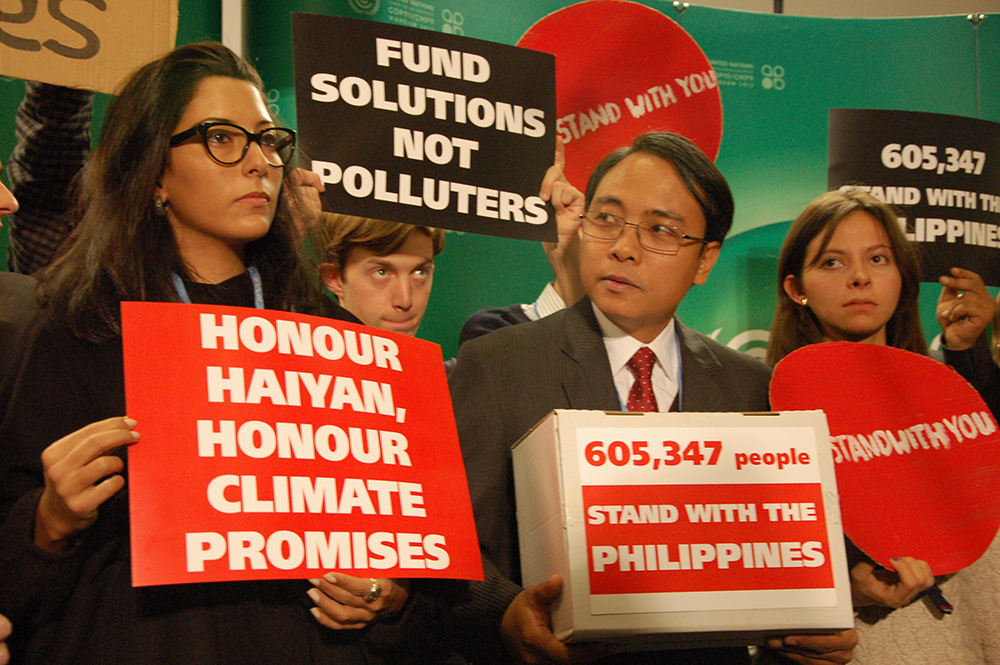

Typhoon Haiyan was a major topic at the 2013 climate negotiations in Warsaw (Photo: 350.org)

CURWOOD: Now how much of this can President Obama do on his own, without looking for 67 votes in the U.S. Senate to ratify some new treaty?

MEYER: Well it depends on how the agreement is structured. If it’s an agreement under the existing Framework Treaty that was negotiated by the first President Bush in 1992 and ratified by the Senate, then it would just be seen as implementing that current agreement. Of course, that agreement because it was purely voluntary, didn’t have kind of kind of any compliance measures or consequences for non-performance as the Kyoto Protocol did, so that would be a shortcoming in a COP decision – a Conference of the Parties decision - but the advantage of course is that you would not be relying on the ability of this president to the next president to come up with 67 votes in the Senate and of course it's very difficult to envision 67 votes in the Senate for just about anything regarding an international treaty these days, much less something as controversial, at least within Republican circles, as climate change.

President Barack Obama (Photo: Justin Sloan; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now how are other countries responding to this approach that the U.S. would come with - it sounds like a souped-up voluntary commitment to reduce emissions?

MEYER: Ahh – they’re not very happy about it to be honest with you. There’s been a lot of gnashing of teeth from some of the developing countries, from the Europeans, including just recently, the European Climate Commissioner, Connie Hedegaard, saying that we need something that is more binding than that. But on the other hand, they all recognize the dilemma that the president faces, and they remember well the outcome of the Kyoto process, where the Clinton-Gore administration negotiated an agreement and then didn’t have a strategy to get it though the Senate. And they don’t want to repeat that experience where the U.S. is left on the sidelines, so I think there’s a lot of discussion underway about ways you might structure something for the US to come in later or for the U.S. to have some sort of enhanced reporting requirement or something else that could give this more teeth, but at the end of the day, the reality is as we found out with Kyoto, where Canada pulled out of the agreement with basically no penalty or consequences, the compliance is really at the domestic level, it’s really at the national level, where you have the ability to hold the feet to the fire of polluters and compel them to do something on their emissions. So what’s really more important is -- does the rest of the world believe that the next president will be as committed as President Obama has been on the climate issue and is there any prospect that within the timeframe of this new agreement, 2020 to 2025 or 2030, that you can envision a future Congress coming in and doing something like an economy-wide cap on carbon or a price on carbon as was tried in the first term of the president.

Alden Meyer (Photo: Union of Concerned Scientists)

CURWOOD: So the White House is keeping close to its vest the actual numbers that it thinks it will put in in terms of reductions, what kind of numbers do you think they should have?

MEYER: Well clearly if you look at what we need to do to get the world as a whole on track to staying below the temperature limits that the president and other world leaders committed to in Copenhagen 5 years ago, which is a commitment to stay below an increase in temperatures of about 2 degrees Celsius, or about 3 and a half degrees Fahrenheit, the US would have to do a lot more than its currently doing and it would have to be joined by all the other major emitting countries in the world, reductions much greater than the 17% that are now on the table, and eventually by midcentury as the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report shows, we need to have deep reductions globally and be moving towards the decarbonization of the global economy if we're going to have the best chance of avoiding the really catastrophic impacts of climate change, so the question is how much can you do it the next 5 years beyond 2020 – you know we think they ought to get quite a bit further down the path; somewhere in the range of 30-35% reduction.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is the Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

MEYER: Thanks, Steve. Good to be with you.

[MUSIC: The Kinks “The Contenders” From Lola vs. The Powerman And The Money Go-Round Pt. 1 (Deluxe Edition) (Sanctuary Records 2014)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: Fish gotta swim, and now they can again...up the whole length of the Elwha River. There’s more ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gilles Peterson/Various Artists/Gene Russell “Black Orchid” from Black Jazz Radio (Snow Dog Records 2013)]

Rafting down the Unbound Elwha

Now that the dams are gone, rafters are enjoying the changing Elwha River. (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

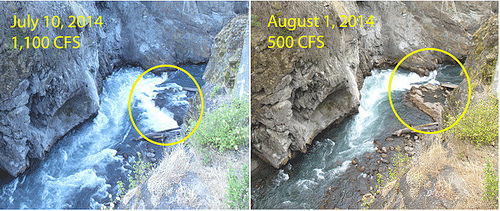

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. It cost $325 million, but now the largest dam removal project in U.S. history is finally complete. The Elwha River, which runs through the Olympic National Park in Washington state, now flows freely all the way to the sea for the first time in more than a century. Two massive hydropower dams blocked the Elwha and barred Chinook salmon and steelhead trout from swimming deep into the forest to spawn. But over decades, biologists, conservationists and Native Americans managed to convince Congress that the value of the dams for electricity was far less than the value of a flourishing salmon river; so now the dams are down, and the salmon are heading up. Ashley Ahearn, a reporter for the public media collaborative EarthFix, took to the water to see the river unbound.

AHEARN: If you were going to, say, try to raft a river while holding a microphone, Morgan Colonel is they guy you want at the helm. He’s been a river guide for ten years.

Two dams blocked Elwha River for over 100 years. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

COLONEL: Alright, gang. Who wants to get the wettest?

[PARTICIPANTS VOLUNTEERING]

AHEARN: Colonel runs Olympic Raft and Kayak. He bought the company three years ago when he heard the Elwha dams were coming out and he’s had a front row seat to watch the recovery process ever since.

AHEARN: Colonel says the river’s changed a lot. New channels come and go as the Elwha twists back and forth across her bed, trying to find the fastest way to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

COLONEL: We’re kinda just figuring it out a little bit as we go. Brand new river to pioneer.

AHEARN: Salmon are starting to come back. This summer, state fisheries biologists counted more than 1,500 King salmon above the former site of the lower dam, and the otters, eagles and bears are catching on.

Un-damming of the Elwha River in Washington State (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

We head into a rougher patch of river as Colonel tells a story about the demise of one sockeye salmon at the hands of a mama otter and her pups, not too long ago.

The otters cornered the fish in a small eddy of the river but it escaped and took off downstream.

COLONEL: That otter was on it. I mean, from the word “go,” that mom headed downstream, but then five minutes later she comes back up holding the sockeye by the mouth. And that sockeye was about as big as her.

[RUSHING WATER]

AHEARN: Millions of tons of sediment have been released from above the dams, creating sandy beaches where there used to be rocky shoreline.

National Parks Services hopes to restore Elwha’s ecosystem. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

AHEARN: Rob Elofson joined Colonel to run the river today. He’s a member of the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe, which has been pushing for dam removal for decades. This is the first time he’s rafted the river since the dams came down. As the group paddles along, Elofson points out that the river is already looking more salmon friendly.

ELOFSON: The small sediment, sand and gravel, wasn’t here. It was just large rocks. And yeah, it’s completely different. It’s the way it’s supposed to be now.

AHEARN: We round a bend and the water grows louder as it rushes into a tight curve, flashing with rolling white caps. This stretch of river is known as Ferngully, Colonel explains.

Rob Elofson on the Elwha (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

COLONEL: This is going to be our best rapid of the day. This is the fun…can be class three in higher water; probably class two plus right now.

[WATER CRASHES]

AHEARN: We come out of Ferngully and the water slows, beautiful and clear beneath us. We’re above where the lower dam used to be, scanning the water for intrepid salmon, who have made it into this newly accessible territory to spawn. Nothing yet. We float quietly.

SCHMIDT: There’s one. I saw something shadowy.

Morgan Colonel, owner of Olympic Raft and

Kayak, on the Elwha (Photo: Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: Kati Schmidt spots a sockeye salmon. She’s with the National Parks Conservation Association.

The gleaming flash of red darts beneath us, headed upstream and into the Ferngully rapids.

SCHMIDT: Ah! Yup! Yay! Go fish go!!

AHEARN: Now that the dams are gone, that sockeye could be the mother, the grandmother, and someday the great-grandmother of countless generations of salmon to come—all free to colonize the Elwha, once again.

Since the removal of the first dam, the salmon have been coming back. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

[RAFTS TOUCH DOWN]

AHEARN: Whew, we made it.

[FEMALE LAUGHTER]

AHEARN: I’m Ashley Ahearn on the Elwha River.

CURWOOD: To see a GoPro video from Ashley’s trip down the Elwha, paddle over to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Elwha River Restoration project from the National Parks Service.

- To measure the effects of the dam’s removal, biologists made baseline assessments of the ecosystem in 2011.

- Ashley Ahearn brought us into a hatchery in 2011 to explore another facet of this project.

- Destruction of the first dam filled the river with sediment—and the fish thrived. Hear more here.

Freeing the Arteries of the Planet

Fall along the Elwha River (Photo: NOAA; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The long awaited dam removal on the Elwha River in Olympic National Park is part of a growing movement to restore rivers that have been hurt by hydropower development. Not only are large-scale dams tough on fish like salmon, they also disrupt other parts of the ecosystem as a whole, and can even contribute to climate change, river advocates say. Jason Rainey is the Director of International Rivers and he joins us now to discuss the Elwha and the state of rivers around the world. Welcome to Living on Earth.

RAINEY: Thanks, it’s great to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So how possible is it to restore a salmon run on a river like the Elwha?

RAINEY: Well the evidence has already come rushing back in. As soon as the dams were breached, the very next run had thousands, tens of thousands of salmon of various species moving into waters that they had not seen in 70 years, so quite remarkable and epic. You need a remnant run to recolonize, but they did so naturally and willingly in this case.

This dam on the Elwha was taken down as part of an effort to restore the natural flow of the river (Photo: Paul Cooper; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Interesting, because neither those fish or their grandparents or even their great-grandparents had ever made that run.

RAINEY: It's true, but there's something instinctual that it brought them up as far as they could go for generations and generations and generations, and once that barrier was removed, they were able to find better, more suitable spawning grounds.

CURWOOD: How common is what's happening on Elwha? Where else are dams coming down here in America?

RAINEY: Yeah, well in the United States there have been over 1,000 dams removed, a lot of them small dams on the East Coast and eastern seaboard. The Elwha dams are the largest of two that are being removed, but others have been removed in the Pacific Northwest as well and have supported a rebounding of salmon populations and another ecological benefits.

Now the Elwha River runs unimpeded. (Photo: claumoho; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What you think about the argument that we need hydropower because it's a renewable source of electricity?

RAINEY: Yeah well that's really the arena that I'm most engaged in these days at International Rivers. There's a hydropower boom happening globally that is unlike any other time before, and the pressure put on the world's rivers is great. My response to that question is that hydropower is really not a renewable resource in the most strict sense of the term—it's dirty energy in terms of what it does to polluting rivers and also polluting the climate with methane emissions, and it also fundamentally disrupts the ecological processes of rivers. And solar and wind are examples of true renewable resources that don't fundamentally alter sunlight or fundamentally change wind currents. Large hydrodams are very different story.

CURWOOD: Talk to me more about methane and hydropower.

Thai villagers gather at the Thai Supreme Court to voice their opposition to a hydroelectric dam on the Mekong River. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Yeah, well, particularly in the tropics when you dam a river and flood an area, the vegetation begins to decompose in anoxic conditions with low oxygen. And the chemical reaction, to just put it very simply, is one that produces methane and methane can be emitted from those reservoirs. There are examples of reservoirs in the Amazon, for example, that are four, five, seven times more climate impact in their emissions than a coal power plant of similar megawatts. So these can be very major contributors to our carbon imbalance. It's estimated that dams and reservoirs account for four percent of anthropogenic carbon emissions globally, which is equivalent to all of the airline traffic globally.

CURWOOD: Now, for a number of years the World Bank said it wouldn't fund ginormous dam projects like we're seeing in developing countries. Why are they coming back on the drawing boards?

A boy holds a fish he caught on the Mekong River in Thailand. Critics say that the proposed Don Sahong Dam on the Mekong would be terrible for the fish population. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Yeah, that's a great question. They did back away because of a calculus and recognizing that the impacts and the voice of concern from throughout the world was too great and that they couldn't build these projects to meet their environmental and social standards, and that they're also generally not great returns on investment. What's changed is that there are many, many actors involved in hydropower building today: China, Brazil, India, a whole multitude of other development banks that are forming. And the World Bank and the leadership behind it—primarily the United States—is interested in not losing out, so it's part of a broader geopolitical game, really, that the World Bank is getting involved in hydropower development again.

CURWOOD: Now, Jason, your organization, International Rivers, recently released an online platform for looking at the health of the world's rivers. How does that work?

The Salween River in Burma is the largest undammed river in Southeast Asia, and these children want it to stay that way. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Yeah, State of the World's Rivers is a Google Earth based platform, and it's a spatial database, which means we've compiled a lot of information about dams. And we've focused on 50 major river basins of the world. And we've also looked at a whole range of indicators of river health if you will, factors such as water quality, biodiversity, the fragmentation of the river, and we've put this all on an interactive map-based platform that allows you to search through these 50 river basins. You can see how the various basins ranked according to one another on these various ecological health indicators.

CURWOOD: So overall, how are the world’s rivers doing?

The fast moving Baker River runs through Patagonia. “Sin Represas” means “Without Dams” in Spanish. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Well, the world's rivers are in grave crisis. We have over two-thirds of the world's rivers functionally impaired. They're not providing the range of services that they normally would, and we've known that for a long time. What this tool is intended to do is to start a conversation at the same level that is deserving of our climate crisis, which is that the state of the world's rivers is in grave peril, and there is no international institution, no panel of experts, looking squarely at the question of: what are the tipping points, how much is enough, can we dam all our rivers for the sake of hydroelectricity and still have viable societies here on Earth?

CURWOOD: What are we at risk of losing if the river crisis continues unabated, in your view?

Peruvian children watch the Ene River in front of their village in an area that would be flooded by Pakitzapango Dam. (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: Well, to begin with, we already know that we're losing more species in our rivers really than in any other ecosystem. The rate of species extinction is greatest in aquatic freshwater ecosystems, but beyond the animals that will never come back and the food web that they provide, we're really dealing with planetary cycles here. Rivers connect us to deltas and to coastal marine systems; they carve their way through the land and are the ribbon of life in dry and wet communities. So we really are on a grand experiment where we're seeing deltas shrinking and deltas are not just interesting ecological zones with a lot of birds. I mean, these are places where people live and are productive and can be used well, as in the case of the Mekong Delta, which provides rice for a great percentage of Southeast Asia.

Indigenous people protest the Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River in Brazil (Photo: International Rivers)

CURWOOD: Some use an analogy and call rivers the "arteries of our planet". If you were to go down that path, those arteries are getting clogged. Are we headed for some sort of metaphorical heart attack?

RAINEY: Yeah, it is a powerful metaphor. We are very much clogging the arteries of the planet, and in many cases, we're doing so under a very simple and false paradigm that says, well, you know the lungs of the planet are ailing—the climate is ailing; the atmosphere is out of balance—and the alternative right now is we'll just dam our way to some sustainable future.

Jason Rainey is the Executive Director of International Rivers (Photo: International Rivers)

RAINEY: And it's really, it's an absurdity from an ecological perspective to think that that's possible and that is exactly what we're confronted in nation after nation and region after region throughout Latin America, Africa and Asia, regions that have very legitimate needs for energy access and development, but are doing so by pushing a mega-dam energy agenda. And that's - it's just a dangerous course for the planet.

CURWOOD: Jason Rainey is Executive Director of International Rivers. It's been my pleasure to speak with you.

RAINEY: Thanks so much, Steve.

Related links:

- International Rivers

- The State of the World’s Resources Map

[MUSIC: Jaco Pastorious “Continuum” from Jaco (Warner Bros 1976)]

Beyond the Headlines

An Atlantic codfish, which has been overfished and in danger since the late 20th century. (Photo: saipal; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time to visit the world beyond the headlines now. Our guide to those sometimes-overlooked stories in the news is Peter Dykstra, publisher of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org. He’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hey, Peter, what’s up today?

DYKSTRA: Well, Steve, let’s start by shaking up a little political conventional wisdom. When you think of West Virginia politics, you think all coal, all the time. But a poll last week by the Charleston Daily Mail asked West Virginians what would turn their heads and change their minds in the voting booth. “The future of coal” finished in fourth place.

CURWOOD: Fourth? What were their top three concerns then?

DYKSTRA: Well, the top three may well be the top three in a lot of places around the country. Unemployment and jobs was number one; healthcare finished second as a voting priority in West Virginia; and the Federal Budget finished third.

CURWOOD: But wait, Peter, you could easily argue that jobs and unemployment is also about coal when you talk about West Virginia.

DYKSTRA: Good point. But it’s still an interesting stat., and here are a few more. I was digging through the data in other recent polling – all of this is from The West Virginia Poll, which is put out by a company called Repass –I found a few more things that make West Virginia unique. President Obama has an unusually huge disapproval rating, 63%, that's more than twice any local official got in West Virginia, and West Virginians showed up on both sides of the fence on a crucial environmental issue. They scored way over the national average when asked if environmental regulation goes too far, but they also have stronger-than-average feelings about big companies having too much power.

CURWOOD: Huh. So there’s a little rugged individualism in West Virginia? Or are we talking about cognitive dissonance here?

DYKSTRA: Maybe a bit of both, but let's get back to coal and the election. With tight races for West Virginia’s house seats and one of its two Senate seats this year, whatever you think of the War on Coal, the candidates are using coal in their war on each other. But let’s move to a different coal story from a different state.

CURWOOD: Yes, please. Anything to move us farther away from war.

DYKSTRA: Well, here’s a story that’s not about war, but redemption and salvation. When a lot of coal barons, politicians and environmentalists jaw at each other over coal, one fact we shouldn’t forget about this huge political train wreck is that coal communities are tied to the tracks and they don't often see a way out of a dying economy. But this week, an Associated Press reporter named Travis Loller wrote a great story about two such coal towns in East Tennessee, Briceville and Lake City. Both have ambitious plans to cheat death by reinventing themselves: Briceville’s taking the academic route, with a foundation doling out over a quarter of a million dollars in college scholarships, most of it going to families where no one’s ever gone beyond high school.

CURWOOD: OK, so that’s the game plan for Briceville, what about Lake City?

Many descendents of Tennessee coal-miners are out of work and searching for better education. Thacker’s Coal Creek Watershed Foundation has helped to fund college education for three dozen Briceville, Tennessee students. (Photo: Hunter Desportes; CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well for starters, Lake City never actually had a lake, so they changed their name to Rocky Top, Tennessee and went all showbiz. They’ve got a theme park, water park, a music venue, and an old-fashioned paddleboat on the drawing board. Of course, they have to build a lake so they actually have a lake to float the paddleboat on.

CURWOOD: Wait a second. Rocky Top is kind of a sacred name in Tennessee. It’s the fight song for the University of Tennessee sports teams, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yes, it is, and that’s why the town of Rocky Top is getting sued by the song’s publishing company. But good luck to both Briceville and Rocky Top in digging out of a coal conundrum down in East Tennessee.

CURWOOD: Yeah, good luck indeed. Hey, Peter, why don't you take us out with a bit of environmental history?

DYKSTRA: It would be my pleasure, but I’m afraid we’re going back to a war story. Fifty-six years ago this week, 20 years of off-and-on hostility began between Britain and Iceland in what became known as the Cod War. It wasn’t out-and-out combat, mind you, but it got a little nasty. And it was all over the codfish. In 1958, Iceland was angered by British fishermen hauling up cod in what was traditionally Icelandic territory along the coast. Iceland imposed a 12-mile limit around its waters. The Icelandic Coast Guard tried to seize a British trawler, but then they were driven off by the British Royal Navy.

CURWOOD: Well why not. I mean, what’s a pub without fish and chips?

DYKSTRA: Well, Iceland managed to defend its coastal fishery, but the Cod Wars flared up well into the 1970’s. There were several ramming incidents: a few shots were fired across the bows of a fishing boats; a few nets were slashed. And then finally in the ’70s, the Secretary General of NATO put both nations’ fleets in a time-out and brokered a deal largely favorable to Iceland’s wish to protect its codfish.

CURWOOD: But all is not well in the Atlantic now though, is it?

DYKSTRA: No, it isn't. Fishermen on both sides of the Atlantic are hurting. On this side of the pond, U.S. and Canadian fishermen have seen years of decline in the cod catch, and over on the other side, when you order the iconic fish and chips, it probably doesn’t have an iconic codfish in it at all any more.

CURWOOD: Things do change, Peter. Peter Dykstra is the Publisher of Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much for taking the time, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve; thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Coal industry’s waning influence on West Virginian voters for Congressional seats.

- Retired Coal towns, Briceville and Rocky Top, Tennessee offer inducements to revive their economies including college scholarships and tourism development.

- The tale of the North Atlantic Cod Wars

- Coal’s importance in the West Virginia Senate race

- More on the decline of Atlantic cod and its sluggish recovery

[MUSIC: Traffic “Low Spark Of high Heeled Boys” from The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys (Island Records 1971)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: a green classroom without walls. That's just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies, and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ernest Ranglin: “Nana’s Chaulk Pipe” from Below The Bassline (Island Records 1996)]

The Green School

The Green School solar panels are oriented straight up and resemble a forest more than a solar array. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Across the U.S., Labor Day is the signal for students to head back to school. It’s also a time of conspicuous spending—with new backpacks and markers, books and a new back to school wardrobe. But on the other side of the world, in the tourist paradise of Bali, there’s a school that the U.S. Green Building Council named the greenest school on Earth for 2012. It’s called the Green School, and it educates some 300 students from 25 different countries. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb went to check out what’s so green about the school, and arrived during a benefit concert.

FRANTI: Thanks for coming out on the first ever day of the Soulshine Festival, making it amazing.

[DRUM BEATS]

BASCOMB: Musician Michael Franti greets an audience of students, parents, and music lovers on the first day of a weekend festival to benefit the Green School in Bali.

The Green School is located in Bali, Indonesia. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

[MUSIC: “ALL I WANT TO DO IS BE WITH YOU”]

BASCOMB: The Green School offers a K–12 education with all the usual subjects and a strong environmental focus. Tuition is $13,000 per year- far too expensive for most Indonesian students. Franti says the proceeds from the festival will go towards a scholarship fund for local kids.

FRANTI: We want to highlight the great eco-work that they do here. But we want equal opportunity for everyone. So, we want Indonesian kids to be in this school as much as the ex-pat kids.

BASCOMB: The Green School opened in 2008. It was the brainchild of John Hardy, a Canadian jewelry designer who moved to Bali in the 1970s. Years later when Hardy retired, he invested his own money in the school.

FORD: He sold his business and when most people say, “Ok, which yacht should we buy?” He said, “I wanna give back. I want to contribute to the healing of this planet.”

With a $100 donation or more people can receive “bamboo immortality” and have a name or image written on a bamboo pole that supports the heart of school. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

BASCOMB: Charis Ford is Director of Communications for the Green School. He’s tall and thin, wears a checkered shirt, shorts, and flip-flops. On a sunny Balinese morning, he leads a tour of the school as musicians perform sound checks for the festival. On the far side of a wide grassy athletic field lies the main academic building, known as the heart of school. The circular three-story building is built from more than four miles of bamboo poles. From a distance, it looks a bit like a spaceship, a bamboo spaceship.

FORD: Bamboo is extremely strong. I've heard it compared to the strength of iron and steel. It is the fastest-growing plant on Earth. If you're patient and willing to sit there, at a certain point in bamboo’s growth cycle, I think when it's around the bamboo shoot phase; you can actually see it kind of –- eeeeek -- stretching into its adulthood.

BASCOMB: It rains a lot in Bali. Humidity and bugs typically destroy a bamboo structure in about 4 years, but the Green School buildings should survive 20 years or more.

FORD: We use treated bamboo, but it’s been treated with salt essentially. We heat water and we submerge the bamboo poles into the saltwater and it makes the bamboo unpalatable to termites and mold and funguses and other things that would biodegrade the bamboo.

On extremely hot days a canvas envelope can be pulled around a wall-less Green School classroom so cool air can be piped in to keep kids comfortable. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

BASCOMB: Most of the support beams are covered with words like ‘inspire’ and ‘create’. Or names like Ben and Jerry’s.

FORD: Whenever anyone donates $100 or more, they earn what we refer to as “Bamboo immortality,” where they get their name, or a quote, or an image carved into the bamboo posts that hold the building up.

[CLUNKING OF WINDCHIME]

BASCOMB: Some 20 huge bamboo trunks hang from the ceiling. Kids walk through this moving bamboo forest, to create a giant wind chime.

[CLUNKING OF WINDCHIME]

BASCOMB: Bamboo is locally grown and used to make everything: floors, bookshelves, chairs, even bamboo bolts to hold the whole building together. Only the roof is made from something else—that's a local grass called elong elong.

FORD: It is basically like very tall grass that has been cut at about three-feet tall and then they fold it over slats and the slats then become a curtain, if you will. And we layer those curtains one over another on the rafters of the building much like you would tile or shingles, or something like that.

All the furniture at Green School is made from fast-growing bamboo. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

BASCOMB: I've been here a few days now and it poured! I've never seen rain like that, but the thatch holds up?

CHARIS: Yeah! Oh, it holds up! Yeah, I heard from a Balinese man that if you put the elong elong on thick enough it can last up to 20 years, which blew me away. Our roof system is not so thick as that, so we need to replace it from time to time. We find uses for our old roofing. We put it into the paths of our garden, or mulch our garden beds with it, compost with it. So, we end up getting a lot of use out of it.

BASCOMB: From the Heart of School we follow winding dirt paths cut through the grass to check out more of the campus. Charis stops at a photovoltaic set up that looks more like a forest than a solar array.

FORD: The solar panels are set on bamboo poles and they are positioned like you might see leaves scattered on a forest floor instead of all lined up like a row of billboards.

BASCOMB: Bali sits just eight degrees south of the Equator. So solar panels here are angled almost straight up instead of pointing south as they do is the U.S., and it works well. At the moment the Green School gets 70 percent of its energy from solar.

Bamboo signs mark the path. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

FORD: But we are in the process of building our hydroelectric energy generator to the produce the rest of our power.

BASCOMB: It’s called a vortex hydroelectric power generator. Essentially they will divert a small part of the river that runs through the campus and direct it into a round enclosure, some 15 feet deep with a turbine and a drain at the bottom. The vortex harnesses the power of a whirlpool to create a constant source of energy.

FORD: That's going to produce 100 percent of our energy alone. So, we'll be producing an extra 70 percent once the vortex power plant is up and running.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Charis leads the way to one of the classrooms, another round bamboo building with a grass roof. But one thing is noticeably missing.

Michael Franti plays for music lovers at the Soulshine Festival. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

FORD: We don't have walls.

BASCOMB: It was part of John Hardy's vision for the school that the classrooms be open, so students can learn while immersed in nature.

FORD: All the building companies that he spoke with were like well, “You have to have walls. All schools have to have walls,” and John said, “Why do they have to have walls?” They rubbed their chins and scratched their heads and said, “Well, where are the kids going to hang the art?” As it turns out, you don’t have to have walls. And we don’t have walls and we’re quite happy about it.

BASCOMB: Just outside the classroom, a chicken wanders through a patch of green beans. Gardens are everywhere, integrated throughout the campus. They mimic a natural forest ecosystem using edible plants, a design called permaculture.

FORD: When you wander around Green School's campus, you might think it looks kind of like it's wild, but then as you tune in and look at the plants that you're around, you'll see that that's a bean trellis, and that's a guava tree, and that's ginger. Even though it looks like a jungle setting, you get a little closer and you see that's chocolate - cacao pods - hanging from a tree next to you.

BASCOMB: All the pupils at the school learn how to grow food as part of the curriculum, including Charis Ford's own two children.

FORD: My fifth grade boy, his class raises the chickens, and they collect the eggs and design the cage. That's their responsibility. My first grader has a garden patch outside of his classroom. He and his classmates weed and harvest and plant, and they bring home armloads of veggies to their families.

Green School gardens are integrated throughout the campus. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

BASCOMB: Each grade has a different responsibility in the garden. Sixth graders Ben and Chayton say they like getting outside to grow food and being inside to learn.

CHAYTON: The classrooms are nice because, like, there are no walls and everything -- sometimes animals will walk in.

BEN: At Green School, you actually experience what you’re learning. And you, like, go outside and do stuff, I don’t know. If you like math, you measure plants or something, I don’t know. But you go outside, and it’s much better than just getting a textbook and learning out of it.

BASCOMB: Is there anything you don’t like about your school?

BEN: No, no, no. It’s a great school.

BASCOMB: Ben says that, but Chayton looks dubious.

BEN: What?

CHAYTON: Well, I mean. Even Ben… I mean...everyone...most kids, kind of don’t like…I mean, it’s not a problem but still, I don’t really like homework that much. But it’s fine.

Green School students Ben (left) and Chaytum (center) are enrolled in the Green School. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

BEN: Oh, yes. I don’t like homework.

BASCOMB: It seems some things are just universal. Still, many kids here love the focus on the arts, especially music.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BASCOMB: Ibu Jan is one of the music teachers here. She’s originally from Hawaii and teaches Zimbabwean marimba.

JAN: It’s beyond my wildest dreams as a teacher to be outdoors, to have children who are focused and open minded to learn new things, in my case learn new music.

BASCOMB: Do you find that the kids are distracted by what’s going on outside, and not paying attention: lack of walls and lack of structure, that sort of thing?

JAN: Yeah, that’s interesting. In the beginning for a lot of students here, you know, there’ll be this big, gorgeous tetrablue butterfly the size of your hand that will just pass through and it does cause a little bit of distraction. But no, I think the subjects are so interesting that they’re pretty riveted by what they’re learning.

The Green School's hydro vortex will produce 100% of the school's energy needs by harnessing the power of a small river that runs through campus. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

[MARIMBA MUSIC]

BASCOMB: On the second day of the music festival, Ibu Jan takes the stage with a group of her students.

BASCOMB: After their performance, I sat down with the students in the band. Sixteen-year-old Adele Geiten moved here from Germany.

GEITEN: I came here from a pretty normal German state school and found myself in absolute heaven, really. It’s funny, you move to Bali from Germany and you start playing music from Zimbabwe, but that’s sort of how it is here. There’s people from all over the place with all different ideas and cultures and they mix together in a really beautiful way.

BASCOMB: Critics point out that the focus on music and the environment could come at the cost of academics. Art student Kathleen Hamilton is from the U.K.

HAMILTION: My friends that did go to more academic-based schools maybe had to work harder on certain exams so people had to push themselves based on what they wanted to do after, which meant a lot of, like, independent study and guiding ourselves essentially.

BASCOMB: But parents seem to think their kids are getting a good education here. Joanne Gelky has two young children at Green School.

GELKY: My kids are excited to learn and excited to come to school, and they don’t want to come home. They can’t wait for school to start. So, I’m happy with the level of math and English and all that stuff their getting. I’m beyond happy with how excited they are about learning.

BASCOMB: And part of what they are learning at Green School is to take care of the environment. Joanne Gelky’s daughter, Chinoa, wrote a song about polar bears that went viral on YouTube.

[CHILD SINGING]

FORD: That came out of the music class.

BASCOMB: Again, Communications Director, Charis Ford.

FORD: Even if a fraction of these kids get it and can contribute to the awakening, or the reorienting of our value set, you know, where we spend more time thinking about how to protect the planet. That’s what the goal of the school is: to raise and inspire people who want to be green leaders.

BASCOMB: These kids will eventually leave the Green School and possibly Bali, but the parents and teachers hope they’ll remember the lessons they’ve learned and become environmentally-engaged leaders and true global citizens.

[CHILD SINGING “I hope you care about the polar bear. That’s all!”]

BASCOMB: For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb at the Green School in Bali.

Related links:

- The Green School’s website

- Creator John Hardy’s TED talk on his “green school dream”

- The U.S. Green Building Council’s Center for Green Schools explains its decision to name Green School Bali as the 2012 Greenest School on Earth.

[MUSIC: The Meters “It Ain’t No Use” from Rejuvenation (Atlantic Records 1974)]

The Quarry

Just below Lover’s Leap (Photo: Rod Clark)

CURWOOD: Some memories remain evergreen in our minds, decades after the person who had the experience has moved on. At least that’s what writer Rod Clark found, when he revisited a childhood haunt decades later.

Mysterious woods on the upper level (Photo: Rod Clark)

CLARK: Children are playing hide and seek in the old limestone quarry at the edge of the village where I grew up. I hear them as I walk; their voices ringing high and clear, echoing off the high stone walls among the mysterious trees. Crows complain; squirrels scold the invaders from the safety of green branches. And suddenly, I am carried back to summer days in the ’50s, when my brothers and I played “Scatter” and “Capture the Flag” on the two wooded levels of the quarry.

Near Deadman’s cave (Photo: Rod Clark)

CLARK: Remembering how we crept among the sumac and the shadows of boulders. How honeysuckle perfumed the air; how once I saw a possum hanging by its tail in the cool shade of a Catalpa. And I remember how we named the secret places of our playground: “Pirates Path”, “Lover’s Leap”, “Dead Man’s Cave”, and most marvelous of all, “Cool Cave”, which possessed in its depths a limestone nook where you could keep a bottle of Coke cold even in the heat of summer.

The entrance to the cool cave (Photo: Rod Clark)

CLARK: And as I ascend the path to the uppermost ridge to look down on a world mapped by children, some of whom are no longer alive, a small boy pops out of the brush in front of me, his eyes wide, burrs tangled in his hair. “Are there any pirates down there?” he demands breathlessly. But I am no longer of his world and cannot answer him.

Pirates Playground, lower level (Photo: Rod Clarke)

CLARK: Without waiting for a reply, he plunges into the green realm below. I hear the rapid patter of his feet descending to the second level—punctuated with improbable leaps and bounds, and suddenly I realize what it is I have been seeking when I make this pilgrimage to the old quarry. Because it is my childhood that is racing away from me, down the steep pathway, among the mysterious trees.

Quarry wall on the upper level (Photo: Rod Clark)

CURWOOD: Rod Clark lives and writes in Cambridge, Wisconsin. He's the editor and publisher of Rosebud magazine, and he took some pictures of the old quarry. They're at our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

Rod Clark is the editor of Rosebud Magazine

[MUSIC: Leo Kottke “Three/Quarter North” from One Guitar, No Vocals (BMG Music 1990)]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, the U.S. Agriculture Department has a new organic way to keep down weeds.

FORCELLA: We had the idea, "I wonder if you could use sandblasters to kill weeds?" Initially, we thought that had to be the dumbest idea in the world. I still can hardly believe that it works.

CURWOOD: Weed-whacking with a sandblaster. That's next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: We leave you this week splashing about in a fountain. Right next to our studios in downtown Boston, there’s a huge circular fountain at the Christian Science Center that is designed for people to come and play in during the hot days of summer.

[KIDS PLAYING IN FOUNTAIN]

CURWOOD: And on this 80-degree day, dozens of kids from around the city have donned their bathing suits and brought their squeals of delight as the cool water refreshes and energizes.

[WATER SPALSHING, KIDS LAUGHING AND SHOUTING]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. We bid a grateful farewell this week to Abi Nighthill and Olivia Powers – thank you both for your cheerful hard work and best of luck. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth