November 14, 2014

Air Date: November 14, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Historic US & China Climate Accord

View the page for this story

In an unprecedented move, US President Obama and Chinese President Xi announced ambitious mutual commitments to cut their nations' global warming gas emissions. Jennifer Morgan of the World Resources Institute and host Steve Curwood discuss the scope of the pledges and their implications for achieving a tough global agreement at UN climate negotiations in Paris next year. (11:05)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood how fall increases wildlife collisions on roadways, coal’s falling stock prices, and recalls the mystery of plutonium technician and union activist Karen Silkwood. (04:55)

Using An Oil Legacy to Save the Oceans

View the page for this story

David Rockefeller, Jr. is the great-grandson of John D Rockefeller Sr., the co-founder of Standard Oil, the enterprise that produced one of the largest family fortunes in US history. Now David Rockefeller, Jr. tells host Steve Curwood about using some of that oil-derived fortune to help save our oceans. (07:55)

Climate Change & Pacific Northwest Glaciers

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

Glaciers in the Pacific Northwest are essential for the region’s drinking water, hydropower and salmon survival. But as EarthFix’s Ashley Ahearn reports, disappearing glaciers make the Northwest uniquely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. (06:15)

Meltdown in Tibet

View the page for this story

The glaciers of the Tibetan plateau feed into rivers that provide water for over a billion people in Asia. But to generate hydropower for its own population, China has begun damming those rivers. Writer Michael Buckley discusses his new book about the exploitation of Tibet’s natural resources with host Steve Curwood. (09:55)

Harvesting "Himalayan Viagra"

View the page for this story

A Tibetan fungus is being sold on the Chinese medicine market as an aphrodisiac, bringing income and problems to rural villages on the Tibetan plateau. Anthropologist Geoff Childs of Washington University tells host Steve Curwood how one village is managing to harvest the resource sustainably. (07:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jennifer Morgan, David Rockefeller Jr., Michael Buckley, Geoff Childs

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: The two biggest global warming polluters on the planet cut a deal to cut emissions.

MORGAN: It’s the first time that, first of all, China has agreed to peak its emissions at an absolute level ever, and it’s a big deal because President Obama has also continued to stay the course and to continue to decarbonize the US economy. And they’ve done it together.

CURWOOD: How they can do it in the face of opposition from Congress.

Also, melt water from glaciers is the key to hydropower in the Pacific Northwest.

RIEDEL: Having glaciers provides stability to our water supply. So, you get into the mid-late July and the snow is melted out of the mountains, if it weren’t for glaciers, our stream flow would drop pretty dramatically.

CURWOOD: But now the glaciers are melting. We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME RETURN]

Historic US & China Climate Accord

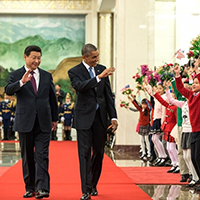

Chinese President Xi and President Obama reached an historic climate deal in Beijing on November 12, 2014 after months of secret negotiations. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza; Whitehouse.gov)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. We follow the progress - or lack of it - towards an international climate change agreement closely. But the latest stark UN science reports, and the hopes to hammer out a meaningful agreement by next year’s climate summit in Paris are giving the subject new urgency. And at the recent Asia Pacific meeting in Beijing, the two largest carbon polluters, China and the US, announced a startling new deal. The US will double its pace of cutting its global warming gas emissions in the next decade, and by 2030 or earlier, China’s emissions will start to fall. A long-time observer and participant in the UN talks is Jennifer Morgan of the World Resources Institute. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Jennifer.

MORGAN: Thanks. Great to be here.

CURWOOD: So how big of a deal is this?

MORGAN: You know, it's a really big deal. It's the first time that, first of all, that China has agreed to peak its emissions at an absolute level ever, and it's a big deal because President Obama has also continued to stay the course and to continue to decarbonize the US economy. And they've done it together, which I think is just this tremendous signal that the world's two top emitting countries have pledged cooperation in trying to solve this problem. It's a big deal.

President Obama arrived on November 10th for the 22nd APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting in Beijing, China. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy; Whitehouse.gov)

CURWOOD: Now, what exactly did President Xi commit to, and how does China get there?

MORGAN: He committed to a peak in their emissions by around 2030 with an intent to be as early as possible, so hopefully it will be more around 2025, and he also agreed to move their non-fossils, so their renewable, energy targets to a 20 percent share by 2030, which is quite a big lift as well. That's about as much renewables as non-fossils, that will include nuclear as well as they have in coal right now in China. How we'll get there...I think there's a couple of different measures they have in place. One is: they certainly have a good renewable energy law that I imagine that they will amend to ratchet up and meet these targets. They have pilot cap and trade systems happening across China, and they've said they're going to do a national cap and trade system by 2016. And they also have a discussion about capping their use of coal which is very important. They're doing that right now in a number of provinces and cities, and there's a discussion about doing that nationally. They have a tremendous air pollution problem along with climate change and so they're taking that quite seriously.

CURWOOD: So what exactly has President Obama committed to and how does the US get there?

In addition to the threats of climate change, China’s severe air pollution problem provides an additional impetus to reduce its burning of coal. (Photo: V.T. Polywoda; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MORGAN: So President Obama has committed to a 26 to 28 percent reduction below 2005 levels by 2025, and he's committed to stick to that long-term goal of an 80 percent reduction by 2050, so a real transformation of the economy. He will get there through his own presidential climate action plan that he announced last year. He has the authority under the Supreme Court to move forward and regulate different sources of greenhouse gas emissions, so he's put in place a new standard for new power plants that means no new coal will be built. He's working on one for existing power plants. He's making the cars more efficient, appliances more efficient, so he needs to continue to move forward with that.

CURWOOD: President Obama's in office for two more years, but he now faces a Congress dominated by the Republicans, many of whom are determined to stand in the way of the EPA's power plant emission caps. How dependent on Congress is this deal?

MORGAN: Well, Congress is not all that involved in this because of the fact that this is done through the Clean Air Act, and is then a partnership with the states. The states have to put in place implementation plans about how they will meet these different standards. Congress, of course, could get in the way if they decide not to fund the EPA anymore or if they decide to try and shut it down, but as you know, that all has to go through the White House at the end of the day. So if they were to try and take such extreme measures, President Obama would need to show that he is really serious about this issue and use his veto power.

China is by far the world’s largest consumer of coal, accounting for 49% of global coal consumption. (Photo: Marshall Segal; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: I know you don't spend a lot of time on Capitol Hill, but what's your view of how unified the Republicans are on opposing climate action?

MORGAN: My sense is that there's a growing awareness across both parties of the impacts of climate change and what it means for various parts of the country, whether they're in Florida, whether they're in Virginia looking at sea level rise. My hope is that those impacts and the growing constituency and public call for action to avoid those costs will help open this debate. We need a bipartisan open debate about how to solve this problem together.

CURWOOD: Specifically, John McCain, a senior Republican has been quite vocal on climate action in years past. What role do you think he might play at this point?

MORGAN: Well, Senator McCain has indeed been a great leader in the past on climate change, and I think particularly his interest in security issues and his likely role there gives him a great position to be looking at the risks of climate change to the security of the United States, moving forward. Hopefully he can bring some of those science hearings that he called when he was chairman before, into the Senate moving forward.

CURWOOD: Now, how does the US pledge compare to previous commitments that America's made?

China emits 23% of global carbon dioxide emissions, while the U.S. nips at their heals with 19%. (Photo: V.T. Polywoda; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MORGAN: So this pledge is very consistent with the previous pledge of the Obama Administration in Copenhagen that pledged to cut emissions by 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020. This is an extension of that it's doubling the annual reduction rate which is great, but really keeps on track for what the Obama Administration has done. I think it's fair to say that before the Obama Administration, really not that much had happened to tackle this problem despite efforts and blockages, and so it's really been on his watch that the US has stepped up to the plate to tackle this issue.

CURWOOD: How does China's commitment today compare to previous pledges it's made?

China may be the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gas emissions, but the U.S. emits approximately 16 tons per capita, compared to China’s 7 tons. (Photo: Greg Goebel; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

MORGAN: China in the past, its commitment in the Copenhagen agreement was to try and slow down the carbon intensity of its growth, but it didn't set an absolute target that it would then reduce from. It also had a set of measures around renewables and other non-fossil energy sources like nuclear. It had a forestry set of commitments moving forward and I think we might see some of those emerging still as part of the full contribution that China makes to the global community moving forward, but the big difference is this peak, which was quite unimaginable even just a couple years ago.

CURWOOD: So, some say that this deal really gives China a free pass over the next 15 years to ramp up emissions as long as they peak by 2030. How fair is that analysis?

MORGAN: I think it misses two points. One is that the commitment is, I think, closer to a 2025 peak, so it's a bit earlier than that claim, but the other thing that people need to realize is that China is indeed still developing in many parts of the country and so it is fair that China gets a little bit more time to shift its enormous economy into this direction. I think it's really the intent and the direction that matters, and that will take a huge effort to make that type of the shift occur.

CURWOOD: You’ve called for the need for China and the US, and I'm quoting here, to "race to the top," to cut emissions and lead the world and build momentum for the negotiations in 2015. What does this deal announced by the US and China mean in terms of the UN reaching a strong agreement on reducing emissions next year?

Morgan says the joint US/China pledges to cut emissions will help catalyze international negotiations at the UN Conference of Parties in Paris in 2015. (Photo: Moyan Brenn; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

MORGAN: I think it is tremendously important. It puts Paris really on the map because these two leaders have stepped forward in the context of those UN negotiations to work together to both reduce their emissions and to strike an international agreement next year. It puts peer pressure on other countries to also step up and put their targets on the table. We've heard from Europe, but what about Japan? What about Australia? What about Canada? What about India? Many other countries still have work to be done, and it takes away this potential for other countries to hide either behind the US or China in saying they're not acting because China is not acting, or they're not acting because the US isn't acting.

CURWOOD: Of course, the big question has been: What will the US and China do? Now that that's out on the table, what are the remaining obstacles, do you think? What are the remaining major obstacles?

MORGAN: So I think the other obstacles, one is the finance issue. So developed countries pledged $100 billion dollars a year for developing countries to be delivered by 2020. It's unclear how that will be delivered, and there's now a pledging exercise for this new green climate fund, which was set up to support developing countries.

Since China and the U.S. together emit nearly half of global greenhouse gas emissions, a commitment to curb their emissions is seen as essential to limiting climate change. Morgan says that the pledges to cut carbon emissions put forth by Obama and Xi should spur other world leaders to follow suit. (Photo: klem@s; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MORGAN: First of all, getting those pledges in place to support developing countries is important, and then looking at how this agreement can catalyze the trillions to be shifting into the low carbon economy. That's a big piece of work that needs to get done. I think the other one is really trying to build an agreement that's here to last and something with an architecture that every five years countries come back to the table and strengthen those commitments that they've put forward. There's lots of discussions about that, but getting that cycle right, getting the timing right, I think is more of an opportunity than an obstacle. And there's other countries out there that aren't as committed as the US and China are right now and so, you know, we need commitments from all major economies, and I think getting all of those in, in time, is a challenge as well.

CURWOOD: Overall, how do you think other countries are going to respond to this deal?

MORGAN: I think that just about everyone would like to see even more ambition coming from US and China, recognizing the challenging target of staying below 2 degrees, but it puts a bounce in the step, I think, of negotiators.

Jennifer Morgan is the Global Director of the World Resources Institute’s Climate Program. (Photo: World Resources Institute)

CURWOOD: Jennifer, you've been involved with the question of climate change and international negotiation for a long time. How you feeling today?

MORGAN: I'm pretty relieved, and I have to say that I was quite speechless. I think I was pretty speechless at the leadership shown to make this happen, and very clear that much more needs to happen, but I'm feeling a little bit later today, feeling that that we have a good chance of galvanizing the type change that we need to make a real difference.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is a Global Director of the Climate Program at the World Resources Institute. Thank you so much, Jennifer.

MORGAN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read the U.S.-China joint announcement on climate change agreement

- Listen to Jennifer Morgan’s analysis on the U.N. Climate Summit commitments in September 2014.

[MUSIC: Real Estate from “Out of Tune” from Days (Domino Recording Company 2011)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a philanthropist turns his passion for sailing into a campaign to save the oceans. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Coleman Hawkins; “Uptown Lullaby” from The Art of Jazz Saxophone: The Masters (Laserlight 1997)]

Beyond the Headlines

More wildlife accidents happen in the Fall than other time of year, due to migrations. Many state and national Departments of Transportation work with wildlife biologists to minimize total the number of collisions throughout the year. (Photo: Heather Paul; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. We turn now to Peter Dykstra for a glimpse beyond the headlines. Peter publishes Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org, and he’s on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Steve. You know, a few weeks ago, I was driving near my house and I had a close encounter with a deer. It darted out right in front of my car. I hit the brakes hard, and maybe just barely clipped the deer.

CURWOOD: Wow. Is everyone all right?

DYKSTRA: Well, I mean, who’s on the show this week, me or my obituary? You know, I’m fine; the car's fine. The deer didn’t break stride and disappeared into the woods. But it was a huge reminder for me that wildlife collisions can be costly and deadly. There was a really thoughtful piece in the New York Times recently with some of the numbers.

CURWOOD: OK. What are some of the numbers?

DYKSTRA: 200 human deaths a year due to animal collisions, almost three-quarters of them with deer. $8.3 billion dollars in car damage, medical costs, police time, not to mention towing away both cars and towing away an occasional moose. Moose collisions are bad, very bad. And get this, a recent study put the number of bird deaths from vehicles as high as 340 million a year.

CURWOOD: Wow. Any remedies, besides the obvious one?

DYKSTRA: By obvious, I’m assuming you mean “slow down,” and yes, I wasn’t driving crazy, but I’m sure I was a tad over the speed limit. You know, there are some engineered solutions for avoiding some wildlife accidents: fences along the road, for example. Florida builds tunnels for ’gators and panthers, and in Canada, they’ve built overpasses for grizzly bears. The feds put out a helpful report on wildlife collisions a few years ago with some advice, and for deer, one big piece of advice: take those “deer crossing” signs seriously, and slow down!

CURWOOD: Well, that’s always good advice, this time of year. What else do you have this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, generally, people who follow the environment don’t always pay close attention to Wall Street, and maybe vice versa. But now it’s time for the Living On Earth business report.

CURWOOD: So, from the floor of the stock exchange...

The New York Stock Exchange trades in commodities like coal. (Photo: Perpetual Tourist; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: It’s been nothing but gloom on Wall Street for some of the biggest US coal producers. A year ago, Alpha Natural Resources sold for over $8 dollars a share. But with coal-fired power plants closing, an uncertain future for the industry worldwide, and growing pressure to clean up the coal industry, Alpha hit rock-bottom at a $1.64 in October. Since Election Day though, Alpha’s jumped back up to $2.76 a share, hardly a complete recovery, but a pretty clear suggestion of how this coal company received the election results, and their coal competitors have seen the same thing happen, like Arch Coal, Peabody Energy, and others have followed exactly the same pattern.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Did the same thing happen with oil stocks?

DYKSTRA: Well, mostly, yes. There weren't any 50 percent-plus drops, but there was a dip in oil stocks in October. Remember that’s when retail gasoline prices dropped, as well, and oil made a comeback after Election Day. Some of the stock analysts cited one more election signal that’s good for both oil and coal – the increased likelihood that the Keystone Pipeline gets approved.

CURWOOD: I get how that’s good for oil companies, but how does it help coal?

DYKSTRA: Well, the fracking boom in this country is having a huge impact on rail freight, the more oil tankers on the tracks, the more coal gets crowded out, and the oil demand for rail lines makes it more expensive to transport coal. So whatever environmental baggage the Keystone pipeline has for a lot of people, the coal guys are actually rooting for the oil guys to win their pipeline.

CURWOOD: Time for our weekly step back into environmental history, Peter. What's on the calendar this week?

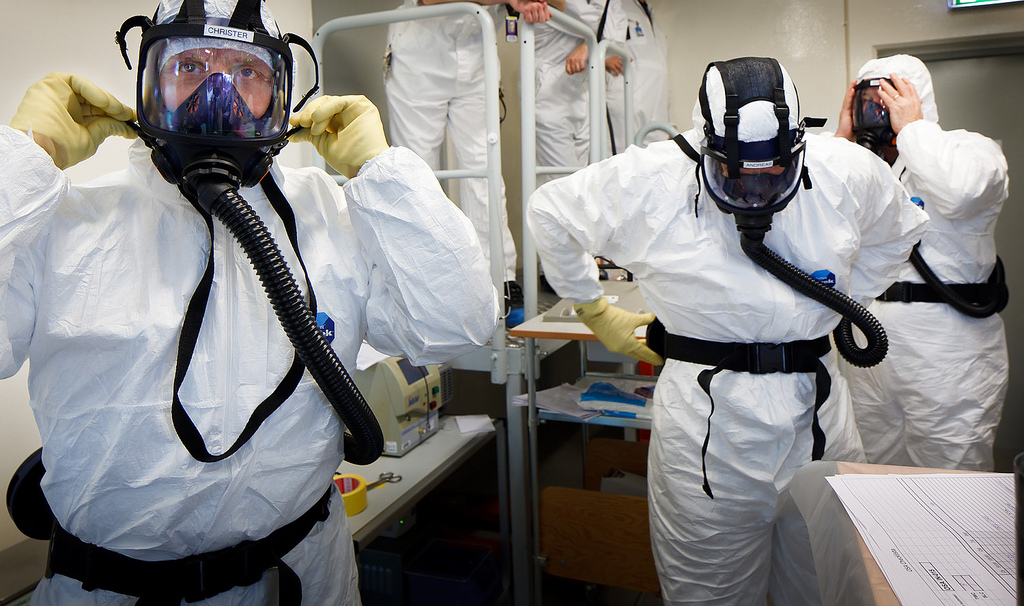

Handling plutonium is dangerous, so strict regulations require that workers suit up before interacting with the element to avoid exposure. (Photo: National Nuclear Security Administration; Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: 40 years ago this past week, Steve, Karen Silkwood died in a car wreck. She was a technician at the Kerr-McGee plutonium fuels production plant in Crescent, Oklahoma. She was kind of a feisty character, at least if you buy Karen Silkwood as played by Meryl Streep in the 1983 movie about her.

DKYSTRA: Karen was contaminated by plutonium from the plant, so was her roommate, so was her boyfriend, and Kerr-McGee put them through a battery of extensive tests. Meanwhile, she crusaded to improve worker safety conditions at the plant and she was on her way to meet New York Times reporter David Burnham when she ran off the road or was run off the road. The Oklahoma Highway Patrol said she fell asleep; others maintain she was murdered. There’s never been closure on how she died, but a lawsuit over her contamination dragged through the courts for 12 years until Kerr-McGee paid her family $1.3 million dollars.

CURWOOD: And whatever happened to the Kerr-McGee plutonium plant?

DYKSTRA: It closed in 1975, a year after Karen Silkwood’s death. Kerr-McGee was later bought out by a firm called Anadarko Petroleum – you might recall them as a player in the Deepwater Horizon oil spill four years ago. And a federal judge just approved a record settlement where Anadarko will pay $5 billion dollars to clean up Kerr-McGee’s radiation mess, not just in Oklahoma but elsewhere.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much, Peter, for taking the time today.

DYKSTRA: Ok, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- New York Times’ piece on highways’ toll on wildlife

- US DOT’s 2008 Wildlife-Vehicle Collision Reduction Study, Report to Congress

- Coal producer, Alpha Natural Resources’ stock price

- Arch Coal Inc.’s stock share

- Value of Peabody Energy Corp on the stock market

- Karen Silkwood’s story of plutonium exposure, nuclear power and worker safety on Frontline

- Meryl Streep stars in Silkwood

- Anadarko To Pay Record Settlement To Clean Up Kerr-McGee's 85-Year Toxic Legacy

[MUSIC: Sepalcure “The One” from Sepalcure (Hotflush Recordings 2011)]

Using An Oil Legacy to Save the Oceans

David Rockefeller Jr., grew up sailing and his love for the oceans spurred him to create Sailors for the Sea. (Photo: David Thoreson)

CURWOOD: Nearly 140 years ago, John D. Rockefeller, Sr. co-founded Standard Oil, which revolutionized the petroleum industry and helped build one of the largest family fortunes in US history. He also helped revolutionize philanthropy, creating, among other funds, the Rockefeller Foundation, now chaired by his great-grandson, David Rockefeller, Jr. David was also a member of the Pew Oceans Commission and is using some of his family’s wealth to help save our seas. Welcome to Living on Earth, David.

David Rockefeller, Jr. sailed on the vessel, Ocean Watch, during the Around the America's expedition. (Photo: David Thoreson)

ROCKEFELLER: Thank you so much, Steve. Glad to be with you.

CURWOOD: So what got you so interested in oceans?

ROCKEFELLER: Well, I grew up on the ocean, and then I became a sailor. And I got to see, not only the coast of Maine but other coasts, and the ocean looked great. It looked wonderful. But then I joined the Pew Oceans Commission in the year 2004 and for three years learned about what lurked under the seemingly beautiful surface of the ocean.

CURWOOD: And with that experience, I gather you became something of an activist.

ROCKEFELLER: I did. Well, you know, commissions and reports are just that. They don't themselves transform policy or create action, but they hopefully lead to it, and so I said to myself, "Well. I've been on this commission for three years. What is it I am best capable of doing now that I know the threats to the ocean?" And the answer was fairly simple in a way: I'm a sailor; I don't think most of my sailing friends or boating friends have the faintest idea - and this is 10 years ago - what the problems of the ocean are. And I am going to form an organization to help educate them and then activate them into being ocean stewards. So that was my dream and my thought process.

David Rockefeller Jr., traveling around Cape Horn. (Photo: David Thoreson)

CURWOOD: Now, you came together to start an organization that you ended up calling, what, Sailors for the Sea?

ROCKEFELLER: Yes.

CURWOOD: And I'm wondering what role do you see sailors or other recreational users have in the effort to protect the oceans?

ROCKEFELLER: I started Sailors for the Sea with the idea that there were some excellent previous models of recreational users of sensitive environments, and my models were: Surfrider, protecting the beach areas, Audubon, protecting flyways and marshes and places where rare birds collected and migrated, and then Trout Unlimited, which protected the trout streams. And in every one of those cases, the recreational users became passionate advocates to keep pristine and well stocked the areas that they depended upon for their recreational enjoyment. So, the oceans. Who could protect the oceans? Sailors and other boaters.

CURWOOD: And how's it going so far?

David Rockefeller, Jr., Captain Mark Schrader, David Treadway, and the late Dr. Ned Cabot on the bow of Ocean Watch as they round Cape Horn. (Photo: David Thoreson)

ROCKEFELLER: It is going very well. We're now...Sailors for the Sea is a little more than ten years old. We got the ear of as many as 5 million sailors and interested boaters when the America's Cup occurred in San Francisco recently. We've got hundreds of thousands of children and sailors who were involved in our regatta programs and education programs.

CURWOOD: So briefly, what you see as the biggest threat to the oceans today?

ROCKEFELLER: Carbon is the biggest problem, not something that the Pew Oceans Commission actually even focused on, so it's really come to our attention recently. And carbon when it dissolves in the ocean increases the acidity of the water and the acidity then keeps shellfish shells from hardening and interferes with the activity of the reefs in a negative way. And all of that undermines the ability of the oceans to provide food for the world, so I think food is the big reason to care about oceans and the big threat is carbon.

Chile’s Cape Horn is the southernmost tip of South America. Strong winds, large waves, currents and icebergs make these waters hazardous for sailors. (Photo: David Thoreson)

CURWOOD: So, CO2 leads to all this acidification in the ocean that has you concerned. What should we do about the sources of CO2?

ROCKEFELLER: Well, humans are the principle source of CO2 emissions through the cars that we drive, the factories that we operate, etcetera, and so the more that we can use alternative forms of energy, the more that our cars are electric or we use bicycles or walk or use mass transit, the better things can be. If, for example, 10 percent of the registered vehicles in the US drove just a mile less a day it would eliminate 22 million tons of CO2, which is about the same amount of the ocean absorbs every day.

Looking beyond the Ocean Watch’s spinnaker, which featured an image of North and South America, representing that we all live on one island surrounded by one ocean and that we must work together to protect this precious resource. (Photo: David Thoreson)

CURWOOD: What about overfishing?

ROCKEFELLER: Well, overfishing certainly is a problem, and it's a problem all around the world and it's driven, of course, by global population. A century ago we were something like 2 billion people. We're 7 billion now. We will, it seems, be 9 billion by mid-century and those people need protein. They need energy. They need food, and as countries like China become wealthier, they will demand more food and more sea protein. So this is a huge challenge and has pushed overfishing.

CURWOOD: Now, you and the Bloomberg philanthropies are trying to leverage the power of private markets to, and I'm quoting you here, "to save our oceans and fisheries." What exactly are you doing?

A beach covered in plastic pollution in Peru was spotted during the Around the America's expedition. Every square mile of the ocean contains approximately 46,000 pieces of plastic, the majority of which originates on land. Plastics such as this poison and kill wildlife and ecosystems. (Photo: David Thoreson)

ROCKEFELLER: Well Bloomberg has made a very big commitment and the Rockefeller Foundation is still working on where it will make its commitment, but we are looking at what it would take to convince, especially artisanal local fishermen, to stop fishing for a period of time, to give the oceans a rest, and what it would take them to finance their livelihood between the time they stop and the time they can resume. Very important because obviously, if you're asking fisherman, most of whom are not wealthy people to give up their livelihood, you need to help them deal with that, so that's the zone that we are looking at.

CURWOOD: So, David, you're chair of the Rockefeller Foundation; your sibling foundation Rockefeller Brothers Fund recently divested from fossil fuels. What steps do you think you'll take at the foundation you chair in terms of divestment?

David Rockefeller Jr. is the Founder of Sailors for the Sea, and Chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation (Photo: David Thoreson)

ROCKEFELLER: The Rockefeller Foundation that I chair already has a very, very low level, I think it's less than 1 percent of its investments in coal and oil and gas, and those were the targets that the Rockefeller Brothers Fund said it was going to bring its level of investment to down to something comparable, which is a wonderful thing. So we're already at a low level and we will probably continue to look at it, but we won't go to the divestment route, but I'm very proud of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund for speaking out publicly about this issue.

CURWOOD: David Rockefeller, Jr. chairs the Rockefeller Foundation and the NGO Sailors for the Sea. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

ROCKEFELLER: Thank you so much, Steve. Glad to be with you.

Related links:

- Sailors for the Sea

- Rockefeller Foundation

- Rockefeller Brothers Fund

Climate Change & Pacific Northwest Glaciers

Erin Lowery is a fisheries biologist for Seattle City Light. His job is to figure out where salmon are spawning on the Skagit River and then make sure his employers’ dams release the right amount of water to allow the eggs to incubate safely. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

CURWOOD: Well, we stick with a watery theme, the frozen water this time of the glaciers of Washington State. The Evergreen State has more glaciers than any other, except Alaska. These ice fields are breathtaking to look at, exciting to climb, and a vital part of the water supply in the Pacific Northwest. But these days they’re melting away. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn has our story.

Jon Riedel, standing just below the Easton Glacier of Mount Baker. He has been monitoring glaciers for the National Park Service for more than 30 years. He's documented the rate at which glaciers in the North Cascades have been shrinking in recent years. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

AHEARN: Guess how many glaciers feed into the Skagit River? Just take a guess. Answer: 376. No joke.

[FOOTSTEPS IN NATURE]

AHEARN: Jon Riedel is hiking up to one of them, on the slope of Mount Baker in Washington’s North Cascades.

RIEDEL: We’re headed up along Rocky and Sulfur creeks and then we’re going to turn and follow Rocky creek up toward the terminus of Easton Glacier.

AHEARN: Riedel’s been studying glaciers with the National Park Service for more than 30 years. The sheer number of glaciers in this region sets us apart from the rest of the country, but it also makes us uniquely vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Glaciers are key contributors to drinking water supplies, hydropower generation and salmon survival in the Northwest.

Riedel pauses just shy of 4,000 feet elevation in the middle of a field of boulders. No glacier in sight.

RIEDEL: If you were here in 1907 you’d be looking right at the terminus of the glacier.

AHEARN (on tape): And now where is it?

RIEDEL: Now it’s around the corner. You can’t see it. The terminus is closer to 4,400 feet and probably at least a kilometer horizontal distance.

AHEARN: Photographs from the 1800s show this whole valley covered in ice. But that’s changing. Glaciers in the North Cascades have shrunk by 50 percent since 1900. Riedel says throughout history, glaciers have advanced and retreated over these mountains hundreds of times. But now it’s different.

RIEDEL: The glaciers now seem to have melted back up to positions they haven’t been in for 4,000 years or more so we’ve kind of gone beyond that natural scale of variability.

AHEARN: Glaciers provide billions of gallons of water to rivers in the Northwest. But it’s not just about the supply - that water arrives when demand is high.

RIEDEL: Having glaciers provides stability to our water supply. So, you get into the mid-late July and the snow is melted out of the mountains, if it weren’t for glaciers, our stream flow would drop pretty dramatically. So the glaciers are providing this meltwater at a time of year when we get no rain, when the snow’s gone, in other words, when we need it the most.

[BOAT ENGINE]

AHEARN: Perhaps no one understands that better than the people in charge of operating dams for hydropower.

RAYMOND: My name is Crystal Raymond and we are at the base of Ross Hydroelectric projects.

AHEARN: Ross dam towers 450 feet above us as we motor up Diablo Lake in Washington’s North Cascades. Raymond works for Seattle City Light. The utility operates three dams on the Skagit River that provide about a quarter of the power for the city of Seattle.

RAYMOND: So we are unique. There are not too many dams that operate in a place where some of the runoff for the project is coming from glaciers.

AHEARN: At the hottest, driest times of year, glaciers are the biggest source of water for some of the streams that feed this hydropower facility. It’s Raymond’s job to figure out what to do when the glaciers are gone. She says Seattle City Light will need to change how it stores water above the dams, maybe expanding the reservoirs to capture more rainwater and save it for those late summer months. Helping customers cut back on energy use is also going to be key. By the time millennials are retiring, summer hydropower production in the Northwest is expected to be down by roughly 15 percent. But Raymond is an optimist.

RAYMOND: It isn’t hopeless. There’s certainly a lot of uncertainty, but we know enough now to start getting prepared and with time we’ll know more, but the sooner we start the more likely we are to reduce the impacts. And there’s no time like the present.

[WATER SPLASHING]

AHEARN: Several miles downriver from Ross Dam, Erin Lowery scans the clear water for salmon nests or redds, as they’re called.

LOWERY: Right there you can see the dark shape, right there in the water. So it’s sort of near the edge of the redd. So that’s a Chinook salmon sitting on the redd.

AHEARN: Lowery is a fish biologist for Seattle City Light. The utility is required to manage its dams to protect spawning fish. Too much water released from the dams and the redds will get washed away. Too little, and they’ll be left high and dry. This mama Chinook’s tail is ragged and white where she’s used it to shovel away the gravelly riverbed to make room to lay her eggs. Now she’s guarding them.

LOWERY: She’ll sit on that redd and defend it until she loses energy and dies.

AHEARN: And Erin Lowery will do his best to defend her.

[CALLING OUT MEASUREMENTS]

AHEARN: He and his team record the location of the redd and how deep the water is there. Lowery says, glaciers aren’t just important because of the water they provide in the summer. It’s the temperature. Glacial melt flows into warming rivers like dropping an ice cube in a glass of lemonade. No glaciers means warmer rivers, and that’s bad news for salmon.

Erin Lowery is a fisheries biologist for Seattle City Light. His job is to figure out where salmon are spawning on the Skagit River and then make sure his employers’ dams release the right amount of water to allow the eggs to incubate safely. (Photo: Ryan Hasert/ EarthFix)

LOWERY: We start to affect, not only the fish themselves, but it can have a negative effect on their eggs, but in rivers that are dominated or have a glacial component to them, we see reduction in temperature, which is key to cold water fish like salmon.

AHEARN: Lowery says it hasn’t come down to a choice between fish or power yet. But he loses sleep thinking about that possibility some day.

LOWERY: I think as we move forward, I mean, it’s going to be a hard look at how we manage flows in the river with a changing climate, with a reduction in glaciers and snowpack because people are moving to the Puget Sound constantly and they’re all going to need electricity.

AHEARN: Scientists aren’t sure exactly when the glaciers will disappear. It could be within a few decades. It could be by the end of the century. But when they’re gone, they’ll be missed.

I’m Ashley Ahearn on the Skagit River.

[MUSIC: Cut Copy “Voices In The Quartz” from In Ghost Colors (Modular 2007)]

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for the public media collaborative, Earthfix. There are videos of glaciers, salmon and dams at our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

EarthFix's "What Climate Change Means For A Land Of Glaciers"

CURWOOD: Coming up: a trip to the Roof of the World, source of fresh water for more than a billion people. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Duke Ellington “Caravan” from Jazz Moods: Hot – Duke Ellington (Columbia 1937//2004)]

Meltdown in Tibet

China’s construction of dams on the Lancang (or Upper Mekong) threatens a complex ecosystem downstream that supports over 60 million people in Southeast Asia. Five megadams have already been built, eight are underway, and several more are being planned upstream in Tibet and Qinghai. In October 2012, International Rivers went to investigate the current status of dam building on the Lancang River. The 990MW Wunonlong Dam would displace several largely Tibetan villages. Two tunnels have been built to house power stations inside the mountain. (Photo: International Rivers; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Only the Arctic and the Antarctic have more ice than the glacial highlands of the Tibetan Plateau, earning it the nickname "the third pole." The headwaters of some of the world's most powerful rivers - the Yangtze, the Yellow, the Brahmaputra, the Irrawaddy, the Ganges, the Mekong - flow from the high altitude plateau into Asia, providing life-giving water for drinking, agriculture, fisheries and recently, hydropower. That’s the subject of a new book from travel writer Michael Buckley, called “Meltdown in Tibet,” which focuses on China’s exploitation of the natural resources of the Tibetan plateau, especially water. He joins us now from Singapore. Welcome to Living on Earth, Michael.

BUCKLEY: Pleased to join you.

CURWOOD: So, you started off as a travel writer. How did you get into political polemics?

BUCKLEY: Well, it really started with a rafting trip. I was on the Drigung River, just out of Lhasa, and I'd never been on a river that powerful in my life. I was told this is just a pimple in terms of Tibetan rivers; this is nothing. But they're also talking about, the biggest problem with the kayaking and the rafting is dams, you know, because they can't get around them, get stopped by them, and I said, "Dams? Which dams?" And they said, "Well, they're all over the place." And I said, "Wait. I wrote a guidebook. I should know about this stuff. Can you tell me more?" So I starting listening to what they were saying, and they said, "Well, if you think about it, it's quite logical. There’re about 10 major rivers that come off the Tibetan Plateau that originate within China. The rivers are the most powerful in world. You've got the hugest hydro-potential ever because you’re starting in the Himalayas and dropping 3,000 or 4,000 meters." So then I started delving into it. That's where the thing got off the ground really.

CURWOOD: When did China begin building dams on these rivers?

Melting glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau feed into many of the regions’ rivers, which China is damming for hydropower. (Photo: ventdroit; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BUCKLEY: Well, China's been gung-ho on dams ever since Mao Zedong came into power, but it was never on the Tibetan Plateau. It was always in the east, but the dam movement in China is expanding with no end in sight. See, they're really big on this green energy thing, and they're saying, "Well, you know, coal is bad;" they're expanding the use of that too. But they're looking upon hydropower as being clean. And so what they're doing, they want to double the amount of hydropower by 2020, and the way to do that is they're looking at the rivers of Tibet because the rivers of China are thoroughly dammed; you can't dam them anymore. China has more dams than the rest of the world put together, so they’re gradually working their way towards the Tibetan Plateau because they build dams in cascades. So they start off on the lower ground and as they build upwards; they use the power from other dams to complete the cascade because you need power to build more power.

CURWOOD: Overall, what would you say is the impact of all these dams on the rivers?

BUCKLEY: It's minimal for now, but it's going to get much, much worse because they've got some big dams coming up. We're not taking about small dams; we're talking about megadams which are defined as over 15 meters in wall height for a certain size reservoir. These things, what they do...they stop the migration of fish. They stop the movement of fish, and they also stop the movement of silts. The silt carries rich nutrients to the countries downstream, and if you don't have those nutrients you’ve got to resort to fertilizers. So it has a huge impact, especially in places like Cambodia.

CURWOOD: Why Cambodia?

BUCKLEY: Well, Cambodia backs up into the one of the biggest freshwater lakes in the world, called Lake Tonie Sap. The fish catch there has dropped drastically in the last 5 to 10 years and they're pinpointing the dams as the cause because the dams reduce the flow of water into that Tonie Sap and Tonie Sap relies on annual flooding. It must be flooded or the fish hatching will not take place properly. Cambodians rely on protein from fish for something like 70 percent of their diet, so if they don't have the fish, what are they going to do? What are they going to turn to for sustenance? It becomes a food problem.

A nomadic tent atop the Tibetan Plateau. (Photo: Nathan Bishop; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So where is all the power going? What are the benefits to the Tibetans from all this?

BUCKLEY: The Tibetans? These dams are not built for Tibetans at all. I mean, you've got a very low Tibetan population; it's always been low. And they're not involved in industry and everything; they're involved in agriculture or herding so they don't need power. They have their own source of power. For thousands of years they've used yak dung. That's all they need. You know, they stack up the yak dung, that's what they use for heating, that's what they use for cooking, that's what they use for everything because there is very little wood on the high plateau. The dams are not for them. The dams are for the Chinese, for their industry, for the military. It's very big for mining. They need dams to power mining, and mining has taken off on a very large scale now.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the mining projects that are going on there and the environmental impact of them.

BUCKLEY: Yeah basically this has picked up a lot. It used to be a small operations like gold miners, individuals, small groups, nothing major, and then along came the railway which is from basically Xining to Lhasa. It's being extended also the moment and eventually they want to take it down to Kathmandu. That railway enables cheap labor to come in and it also enables economic exportation of minerals for the first time in Tibet's history. So what's happening now is that you're getting very large scale mining going on and Tibet has huge reserves of copper, lithium, gold, silver, you name it. It's got a lot of stuff that's never been touched because the Tibetans never mined anything. It's against their religious practices to dig up anything. They didn't like disturbing the ground.

CURWOOD: I gather that there've been a lot of land grabs for mining projects in Tibet.

BUCKLEY: Yes, and this is a practice that's not only in Tibet; it's across China. In the case of Tibet, they've taken over land in the grasslands especially, which traditionally is being grazed by the Tibetan nomads, and they've just ripped up any contracts that they've got with these people and told them, "Your 30 year lease is not worth anything now. Move along. Just go and get settled in the house over there."

In order to make the land grabs much more easy, they've declared these areas national parks, and this is the worst form of greenwashing you will ever come across. They declare a place to be a nature reserve and they go and inform the nomads, "You're in a nature reserve. You'll have to leave." And they say, "We've been here for thousands of years, hundreds of years." And they say, "Well, that doesn't matter."

China’s exploitation of Tibet’s natural resources is increasingly forcing the displacement of Tibetan nomads. (Photo: gill_penney; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BUCKLEY: And as soon as they move out, they wait a little bit and along comes a mining company suddenly on the grasslands. The thing Tibetans really object is when they start mining at sacred mountain sites - a lot of villages have their own sacred mountains - and if you disturb the spirits, it's very bad karma for them. They really do not like mining at sacred grounds and mountains and there's a fair bit of that that goes on.

CURWOOD: Now what's the status of wildlife there in Tibet?

BUCKLEY: Unfortunately a lot of the wildlife has gone missing. There was a delegation from about 1980 from the Government-in-Exile, and they were shocked at the conditions the people were living under, but also, they were also shocked by the silence of the grasslands. They did not hear the herd of animals that they would normally hear, you know, the wild asses, the wild yaks, the thundering hooves, and even the birds were missing, and they started looking around. And they could not find any wildlife, and it was gone. It was just decimated. And we put this down to the military, the settlers—the Chinese settlers coming in. They would eat the wildlife for meat or export it back to China - it was considered a delicacy - but back in the 1930s the Tibetan Plateau was considered to be the Africa of Asia, you know, like the Savannas. It was lots and lots of wildlife up there, but it's all gone missing.

CURWOOD: How are the yaks doing?

BUCKLEY: Well, the yaks are doing poorly. You've got two kinds of yaks. You've got the wild yaks and then you've got the domestic ones. The wild yaks are almost double the size of a regular, domestic yak, but there's probably fewer than a thousand left in Tibet. Thousands of years ago, the wild yaks were domesticated—they were tamed by Tibetan nomads to become the beast of burden for the plateau. They get everything from the yaks. They get the yak dung as fuel. They use the yak hair to make tents. They don't want to really eat the yaks, though, because if they eat them, they lose them. So their objective is to milk them, get the butter, cheese, whereas the Chinese attitude is a little bit different. They came up with this idea that they should make these yaks into meat where we can actually eat them.

Michael Buckley is the author of Meltdown in Tibet. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Buckley)

BUCKLEY: It’s very alien to Tibetans, this idea; they don't like this idea at all. When the nomads are settled, in order to make it a non-reversible process, the Chinese will take away the yaks and send them to the slaughterhouse. If they don't have yaks, they can't survive. What you need to do with these nomads if you’re going to settle them is you have to retrain them because otherwise they have no skills. Their skill is survival on the grasslands. They know how to do that very well; they've done it for centuries. But as soon as they settle into these houses, suddenly they have to pay for water. They have to pay for electricity. They don't have a food source. So they become nobodies, like refugees in their own land.

CURWOOD: Michael, where do you see all this heading? I mean, what chance do Tibetans have at slowing down the damming of the rivers, the mining of their mountains, the displacement of their nomads?

BUCKLEY: Well, they're up against a military industrial complex that whatever they try to protest, it would just be squashed; people are imprisoned. People disappear. I mean, there have been a number of demonstrations against mining where Tibetans have been killed. The only chance that you might have for stopping some of this damming, which happened in the southeast, in Yunnan, Szechuan, is Chinese groups. They don't like those dams either, and they have mounted fierce protests in Szechuan and Yunnan, and they've had some successes. So I think the only chance of really stopping activity like this, lies with Chinese NGOs and Chinese groups for being very brave and manage to highlight the issues and manage to stop a few projects.

CURWOOD: Michael Buckley's new book is called “Meltdown in Tibet: China’s Reckless Destruction of Ecosystems of the Highlands of Tibet to the Deltas of Asia." Thank you so much.

BUCKLEY: OK. Well, good talking to you and thanks very much.

Related link:

Meltdown in Tibet by Michael Buckley

Harvesting "Himalayan Viagra"

Cleaning harvested yartsa gunbu prior to sale. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CURWOOD: Among the many resources of Tibet is a fungus that Chinese medicine prizes as an aphrodisiac. It’s been the target of collectors and speculators, and the source of conflicts and even some deaths up in the fragile Himalayan grasslands. But one community in the highlands of Nepal has found a way to manage the harvest sustainably using cultural traditions, laws and concensus. Geoff Childs is an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, who wrote in the journal Himalaya about the fungus called yartsa gunbu.

Anthropologist Geoff Childs with Lama Gyatso (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Yartsa Gunbu in Tibetan means “summer grass winter worm”. It's actually a caterpillar of the ghost moth, which becomes infected by a fungus, and in the springtime, the fungus shoots a stoma out of the ground, which allows people to locate it in highland pastures. Generally it grows at 12,000 feet and above, and it's become very popular in Chinese herbal medicine for health, longevity, to boost the immune system. It's considered to be a libido enhancement, which is why some people like to call it the Himalayan Viagra.

CURWOOD: I gather it sells very well.

CHILDS: It's extremely popular in China now to the point where in many rural areas on the Tibetan Plateau, gathering it has become the primary source of income for rural dwellers, so people are basically suspending all other activities in the months of picking which generally come starting in late May and run through June. And the whole family moves up to the high pastures to gather it, so that it can be sold to middlemen who take it to China and that's where the market really takes off.

CURWOOD: So in general how has it been harvested in recent years?

CHILDS: People will basically crawl along the ground looking for it and when they find it they'll carefully dig it out with the spade or some digging implement and remove it from the soil because you want it intact: You want the caterpillar body and the fungal stoma as well. That's where it's got the value. If it's broken apart it doesn't have the same value so they dig it out very carefully and, you know, a good day somebody can maybe find 20 to 30 of these. Some people are adept and can find 100 or more.

CURWOOD: Wow. And each one of these is worth quite a bit.

Yartsa gunbu (Ophiocordyceps sinensis), also known as Himalayan Viagra. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Yeah. Each one has gotten from middlemen about 500 rupees. If it's really good, maybe 750 rupees. So $5 to $7.50, which, in a place where there is very little income earning opportunities, that's a lot of money.

CURWOOD: What are the environmental impacts of all this harvesting? I mean, all these people running around the hillsides there in the mountainous Himalayas, some of that's pretty fragile stuff.

CHILDS: Yes, that's certainly going to have an impact, and especially in those areas were they allow a lot of people to gather. Number one, you're going to have people chopping down the juniper for fuelwood because they have to cook their food and keep warm, so there's going to be an environmental impact there. There is also a lot more people digging up the turf, which is fragile high-altitude alpine turf, so that we'll certainly have an impact. And then there's the garbage issue. People will bring in goods and set up stores. It's not just the harvesters that are making money, it's people who are catering to their needs who make money, and behind those stores there's often a very large heap of garbage.

CURWOOD: Now, you did much of your research in this small Tibetan area called Nubri and you say that they are doing things differently there. How so?

Rudimentary shelters inhabited by yartsa gunbu collectors. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Yes, correct. Nubri is a valley in Gurkha district in the country of Nepal. The residents are ethnically Tibetan. They've been living there for about 700 or 800 years, so it's an indigenous population of Nepal. What they have done in contrast to other areas is they've limited the number of collectors to only residents of the villages, and so that keeps the number of collectors way down.

CURWOOD: Tell me how the community of Nubri got its regulations put in place.

CHILDS: What they've arrived at in Nubri is a combination of what they call “yultim” which we could translate as village regulations, secular regulations, and “chutim” which are religious regulations. On the religious side, there's a long tradition of protecting the landscape through these ceiling decrees. It's called a “shukya”. What they will do is, they will decree certain areas off-limits to human exploitation, and usually that's a sacred grove of trees, a certain slope of a mountain that a deity inhabits or something like that. So some areas are totally off grounds for gathering because they have been decreed a religious protected area. In terms of the sustainability of Yartsa Gunbu, that's going to be important because those are areas where annually nobody will harvest it. So it can come to fruition. It can spore. It can live out its normal life cycle.

In terms of the village regulations the first one that I just mentioned is the exclusion of all outsiders. The second one is they've got a designated starting date, and they arrive at that by looking at the snow melt, looking at the conditions in the alpine pasture and figuring out what's going to be the likely time when it's best to gather it. And so for a couple weeks prior to the official starting date, every adult in the village has to check in four times daily to the village meetinghouse to prove that you're not collecting early. A third thing that they do is they tax it. For the first member of your household, the tax is very low; it's 100 rupees or approximately $1 dollar. For every additional household member, it's 4,500 rupees, so about $50 dollars and they gather that tax and use it for communal purposes.

CURWOOD: So this consensus process, everybody agrees, everybody trusts, but they also verify.

Mt. Manaslu (26,759ft.) in Nubri is the 8th highest mountain in the world. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CHILDS: Exactly. It's a very transparent system, but it is also regulated in such a way that you need to show up. Everybody takes it very seriously.

CURWOOD: So, how has Yartsa Gunbu harvest changed the economics of Nubri?

CHILDS: It's changed it tremendously. There's positives and there's negatives. The positives are people suddenly have money that they can use for their children's education; a lot of people are using it to send their children to boarding schools. They can improve their housing. I've seen a lot of improvements in local housing, upgrading the conditions of their housing. They can buy food with it. They don't produce enough food locally; they’ve had to trade various products in the past to get enough food. Now they've got cash to purchase food. On the negative side, you can imagine that people who have never had this type of income, when they suddenly come into money, it can cause a lot of social problems, so gambling and drinking are way up. There's also friction within families. Younger members tend to take the income and go to the city and blow it all really quickly, whereas the older members want to conserve it and use it in a way that benefits the family. So it has certainly improved their livelihood and their standard of living, but of course it does come at a cost.

Prayers inscribed on stones mark the trail to the high pastures where people collect yartsa gunbu. (Photo: Courtesy of Geoff Childs)

CURWOOD: So Jeff, looking at this from a broader resource management perspective, what are some lessons that we can take away from what's happening in Nubri?

CHILDS: Trust indigenous people. Don't immediately assume that as outsiders with more education we can come in and devise a system that will work for them. I think, first of all, study what's in place. Study with an open mind and move from there.

CURWOOD: Jeff Childs is an Anthropology Professor at Washington University in St. Louis. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today Professor.

CHILDS: Thank you for talking with me. It's been a pleasure, Steve.

Related links:

- Anthropologist Geoff Child’s paper on sustainable harvesting and management of Yartsa Gunbu

- “Himalayan Viagra fuels caterpillar fungus gold rush” Press Release on how Tibetans devise a sustainable regulatory management plan

- Geoff Childs is an Associate Professor of Anthropology with Washington University in St. Louis

[MUSIC: The Black Keys “Lonely Boy” from El Camino (Nonesuch 2011)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of the team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us please on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth