April 10, 2015

Air Date: April 10, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Bill McKibben on Earth Day and the Power of Protest

View the page for this story

Earth Day is typically seen as an occasion to take action to help the environment, to ride your bike to work or pick up litter along rivers and streams. But environmental writer turned activist Bill McKibben tells host Steve Curwood we need to take to the streets together to solve the massive problem of climate change. (15:00)

The State of the Gulf, Then and Now

/ David LevinView the page for this story

Five years ago, the DeepWater Horizon well explosion gushed 200 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Since then, scientists have been examining its effects on the ocean and marine life. In 2012, reporter David Levin chronicled the efforts of a team of chemists, engineers and biologists assessing the overall damage to the Gulf ecosystem. We look back on these events and host Steve Curwood turns to David Hollander, a leading marine chemist involved in this research, for an update on the state of the Gulf today. (13:30)

Patagonia's Beaver Problem

View the page for this story

In their native habitat, beavers can provide many ecosystem services, but they are invasive in Patagonia, at the southern tip of Chile and Argentina. The online publication Motherboard filmed a documentary of the beavers’ environmental destruction there. Motherboard's Editor-In-Chief Derek Mead tells host Steve Curwood about the government’s efforts to kill the invasive rodents and why the situation is so dire. (04:25)

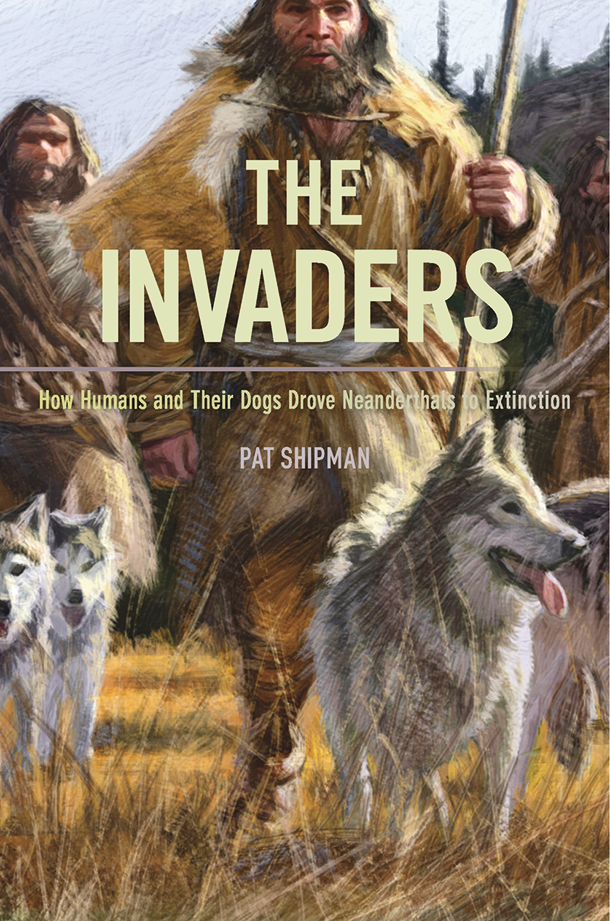

The Invaders

View the page for this story

There are many theories as to why our ancestral cousins, the Neanderthals, died out: everything from climate change to lack of intelligence. Pat Shipman, a retired Professor of Anthropology, has a new theory, explained in her book The Invaders, and in conversation with host Steve Curwood. She argues that modern humans, the most successful invasive species of all time, can thank our canine companions for this competitive edge over Neanderthals. (14:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Bill McKibben, David Hollander, Derek Mead, Pat Shipman

REPORTERS: David Levin

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. As we approach Earth Day, environmental activist Bill McKibben says it’s not enough for each of us to change our light bulbs or bike to work if we really want to save the climate.

MCKIBBEN: This is a structural and systemic problem, and its answer will be structural and systemic. As an individual the most important thing you can do is not be an individual. We need to join with each other in movements and become part of this fight, because it is a fight.

CURWOOD: What Mckibben plans to do. Plus, it's been five years since the Deepwater Horizon disaster fouled the Gulf of Mexico with over 200 million gallons of oil. We have an update.

HOLLANDER: The good news is it’s recovering, the bad news is that it's still pervasive in the area and we don’t have an exact understanding of how long it will last.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Bill McKibben on Earth Day and the Power of Protest

Divest Harvard sit-in (Photo: 350.org; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Writer Bill McKibben is the award-winning author of the End of Nature and many more books, who’s now better known as the founder of the climate change advocacy group 350.org. As Bill has changed his focus from page to picket line, he’s gone to jail protesting the Keystone XL pipeline at the White House, and toured dozens of college campuses in the push to get endowments and pension funds to stop investing in fossil fuels. And as we approach the 45th Earth Day, Bill McKibben joins us to talk about the state of the environmental movement.

MCKIBBEN: Earth Day’s interesting because the most important one by far was the first one. I mean, I'm not sure any more is a very important moment in the year, but the very first one could not have been more important. In 1970, 20 million Americans went into the streets. That was about one American in ten of the then population, and that was absolutely enough to absolutely transform the political landscape. It may have been the highest participation in any protest in American history, and what it meant was, for the next 4 or 5 years, everything with the word environment in it got passed in Washington. Richard Nixon, who was as un-environmental a human being as it’s possible to imagine, he signed the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, all because he knew that there was this tide of people who had been in the streets and were ready to go back, who were demanding action.

CURWOOD: So what happened to all that energy that did bring us the Clean Air and Water Act, Superfund and so forth? Where did it go?

MCKIBBEN: Well, I think a couple of things happened. One was the environmental groups, born many of them out of Earth Day, were winning everything in Washington. I remember the great Gus Speth, great environmentalist of the 20th century, telling me NRDC won every court case they fought for the first ten years after Earth Day. So what I think what they decided subconsciously was the way to do this is to be in Washington as experts. We've got all the juice we need; everyone's working with us. We'll just move this process along. And that's what happened for a while. The problem is, all that progress was not because they were right about things, though they were; it was because they had the power that came from a big movement behind them. It's like a battery with a lot of energy in it. Because everyone was in Washington lobbying instead of being out in the streets, revivifying that movement from time to time, that battery wound down slowly. The good news is, in the last four, five years, that movement is rebuilding. And you saw it last September in New York City when there were 400,000 people marching down Sixth Avenue to demand action on climate, that's biggest demonstration about anything in this country for a long time.

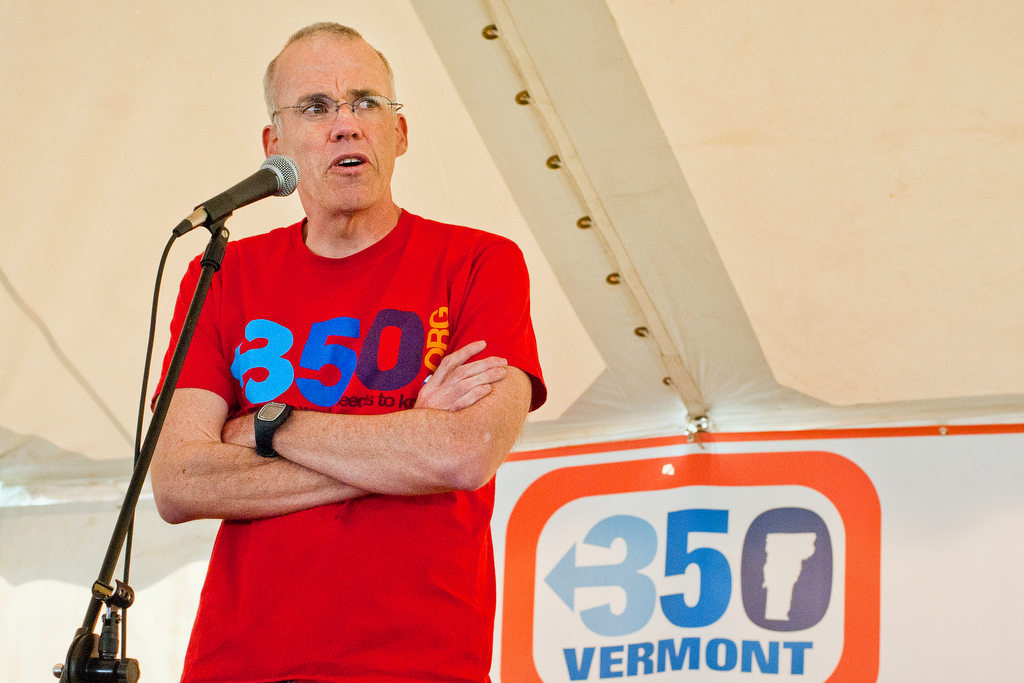

Bill McKibben at an event in Waitsfield, Vermont (Photo: 350VT; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Still, 400,000 people is a long shot from 20 million people on that first Earth Day.

MCKIBBEN: It must be said that's more people than were out in New York on that first Earth Day, and it's not as big as it needs to be yet, but people are doing a good job of building movements, and there's no reason to be discouraged I think, except that the problems that we're fighting now, climate change in particular, are different than all the other problems that we've ever fought because they come with a time limit. So the days when I get discouraged are the days when I read the latest scientific papers on the Arctic, or the Antarctic, or the acidification of the oceans, or as with today the rapid melt of glaciers in the high Andes, and realize as fast as we're building this movement, it's possible that it’s not fast enough.

CURWOOD: That means you're virtually discouraged every day because science is telling us we're in a lot of trouble over the climate.

MCKIBBEN: In some part of every day I'm discouraged. And in some other part of every day I am optimistic as hell because I look at my email inbox and see the messages flooding in from people in every corner of the planet. There are people going to jail today in Australia to fight the biggest proposed coal mine on Earth, people racking up new victories against fracking in Poland or France or Scotland. The indigenous communities around the world, which over the last year or two have risen up to assume leadership of this great fight. It's inspiring to see it all and whether or not it's going to happen in time, I try not to spend an immense amount of time thinking about it, it doesn't do us any good. We've got to do what we've got to do.

CURWOOD: So, yeah, let's talk a little bit more about the climate here. Even at Earth Day plus 20 it seems like society was good to go to confront the climate. Even the first President Bush signed onto the framework convention of the international negotiation on climate change. There was a loud hurrah across the political spectrum. What happened do you think?

MCKIBBEN: Well, what happened was the fossil fuel industry fought back. This is the richest industry in the history of the planet, and they have no problem rallying their troops because their troops tend to be people like congressmen and public service commissioners who they think they are for sale. And they've been able to use their fleets of political representatives to push back actual action on climate change. It turns out that delaying action is the easiest thing on Earth in our system. If all you want to do is keep the status quo, and you have plenty of money, then you're able to do pretty well until some movement rises up and gets in your face.

CURWOOD: So, you've had a key role in trying to build a more confrontational environmental movement. For all these years, you've been a writer. When is it that you decided that that was not enough, that you needed to found something that you called 350.org.

A climate change rally in Bangladesh (Photo: Oxfam International; CC BY 2.0)

MCKIBBEN: Well, of course, as a good writer, my sense was that this was an argument, and reason and data would prevail and we would do the right thing and I foolishly went on about that for ten or 15 years. Until it dawned on me that we won the argument long before the science was entirely clear, economics were entirely clear, the engineering was entirely clear, we even had the thing - solar panels, windmills - that we needed to turn the corner. There wasn't an argument about any of those things. It was a fight, as fights usually are, about power. And that's why we need to organize. Now I think the emotional moment for me came in Bangladesh where I was doing some reporting. And as you know, Bangladesh will take it on the chin from climate change. But while I was there they were having an acute problem, their first big problem of Dengue fever, a mosquito-born disease that is spreading like wildfire as the climate changes. I was spending a lot of time in the slums, and eventually I got bit by the wrong mosquito and got sick myself, and was as sick as I've ever been. But, of course, I didn't die because I was strong and healthy going in. But sitting in the clinic, looking at the people shivering and some of them dying. I was reminded of the fact that if you looked at the global tables, 180 million people in Bangladesh, you can't even calculate how much carbon they produce - it's a rounding error in the calculations, whereas my country historically is by far the biggest producer of carbon. At some point, those sort of things just persuaded me that another book was not going to move the needle. Instead, we needed to organize. I didn't know if we could, but as it turns out we've been able to.

CURWOOD: So you decided it's time to start a movement. What was your strategy here? What would be the tactics you'd employ?

MCKIBBEN: So, for the first few years, the job of movement building in a sense is to educate, to get people on the same page. But very quickly, because of the time frame we felt that physics was imposing; we felt the need to go beyond education to confrontation. We kind of started the fight about the Keystone Pipeline that has helped lead to a lot of other fights all around the continent and around the planet, and though those are very good and important fights, and we'll do them all, we also felt the need to go beyond playing defense, trying to sort of stick our finger in the dyke and prevent each new pipeline or coal mine or whatever from coming along. We were running out of fingers, you know? So we also wanted to play offense and offense in this case is this divestment movement, which means going after the financing and the political legitimacy that allows these guys to do their things. We can't actually bankrupt Exxon, but we can politically bankrupt them, and we can make it politically hard for them to do their work. The argument, Steve, that has undergirded the divestment movement came from some financial analysts in Great Britain who pointed out that these fossil fuel companies had in their reserves about five times as much carbon as the scientists say would take us past the two degree red line for warming, i.e. if they carry out their business plan, the planet pays. First it was Naomi Klein and I that sort of hatched the idea. This seemed to us reason to consider these companies rogue companies in the same way that companies that supported Apartheid in South Africa a generation ago were rogue companies. And so we've been asking people to sell their shares and take a stand, and a lot of them are doing it. An Oxford University study said this was the fastest growing such anti-corporate campaign in history, even in the last month we've had two new billion dollar endowments, the Guardian Media Trust and Syracuse University unload their shares. The high point of this campaign probably came last September, the night of that big climate march in New York, and that evening after those hundreds of thousands of people had paraded through the streets that evening, the Rockefeller family announced they were divesting their chief philanthropy, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund from coal and gas and oil. As symbolic moments go, they don’t get much better than that. This was the first family of fossil fuel. They decided it was immoral and imprudent to be invested in this stuff any more and if you wanted to pick a symbolic hour that was the kind of the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel age. The question now is how fast we can bring it to an end, and if we can do it quickly enough to save the climate.

The divestment movement at the University of Wisconsin. (Photo: Fossil Free UW Coalition; CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: How much credit would you give your movement to the remarkable drop in the stock prices for fossil fuels? Coal is 15, 20 percent of what it was just a couple of years ago. Even oil prices have dropped precipitously fairly recently. Any relationship to what you're doing?

MCKIBBEN: Oil prices are notoriously volatile and always have them, and that's one of the problems with relying on oil. That's why it will be so nice when we move to the sun. I think that movements have probably done even more to make it difficult for these guys to get financing for these projects. Even last summer before the price of oil began to drop, some of the big oil companies pulled about 17 billion dollars out of plans for tar sands expansion, for instance, because they have no faith they'll ever get the pipelines built that they need. So I think movements in general are doing a lot of the work. I think the other half of the work is coming from the engineers. Every month now the price of a solar panel drops another one and a half, two percent. It's dropped 90 percent in the last six or seven years. What that means is to the degree that we're able to kind of enact a de facto fossil freeze, we've also got going on at the same time a massive solar thaw, and that is changing the economics on an almost hourly basis where there were days last summer that the Germans generated 80 percent of their power from the sun. The Danes last year got 40 percent of their power from wind. Spain last month got 47 percent of their power from renewables. Costa Rica managed to get all its energy from renewables for the first three months of this year. It's possible to do it. The question is: do we have the will to scale it up fast? The engineers have done their job. We're going to have to scale up of political will to make that happen.

CURWOOD: Now, in a bit you'll head to Boston to participate in some divestment actions at, well, we're you went, Harvard. What's going on at Harvard and why is that an important divestment target?

MCKIBBEN: Well, it's one of many. And probably Harvard will be one of the last ones to come along. I just did a piece for Slate about how Harvard has reacted to every instance of social progress. The 150 years it took for them to decide that women were worth fully educating, or their 60-year campaign to keep gay people away, or the fact that even 60 years ago they weren't letting Jews marry at the college chapel. But it's important to go raise the flag there like it is every place else. Students have done an important job pointing out the hypocrisy of Harvard's position. This is one of those research institutions where we actually figured out what was going on the planet. Its scientists have been crucial in this, but its Wall Street heavy corporate board simply is unwilling to do the logical thing that places as diverse as Stanford and Syracuse and the University of Dayton have done and begin the process of cutting ties with the dirtiest industry on Earth that just won't do it. So, we'll go and make as strong as a show as we can and it'll be fun because there will be all kinds of good people on hand, lots of Harvard alumni who have endorsed this, ranging from the obvious Al Gore to the unexpected, Bevis Longstreth, two-time Regan appointee to the SEC who has become an outspoken proponent of divestment.

US Senator Ed Muskie, author of the Clean Air Act speaks on Earth Day 1970 (Photo: Peter54321, Wikimedia CC BY 3.0)

CURWOOD: Before you go, in recent times Earth day has evolved into a time where people pick up some litter or buy a Prius. How can folks get more involved in this more confrontational movement that you're so much a part of, Bill?

MCKIBBEN: So, environmentalists have spent, maybe wasted, a lot of time on individual action in the last few years. It's not that they're not important. My house is covered in solar panels and I drive an electric car and eat locally and all of that. But I try not to fool myself that it's changing the outcome here. This is a structural and systemic problem, and so its answer will be structural and systemic. That means that as an individual, the most important thing you can do is not be an individual. It means we need to join with each other in movements. That's why we set up things like 350.org, to give people easy on-ramps into becoming part of this fight because it is a fight.

CURWOOD: Bill McKibben is the founder of 350.org. Bill, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MCKIBBEN: Thank you, brother, very, very, much.

Related links:

- 350.org

- http://350.org

[MUSIC: Imogean Heap, Earth, Elipse, Meagaphonic 2009]

CURWOOD: Coming up...checking up on America’s biggest oil spill disaster five years later. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dick Hyman Group Featuring Howard Alden. I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles, Sweet and LowDown]

The State of the Gulf, Then and Now

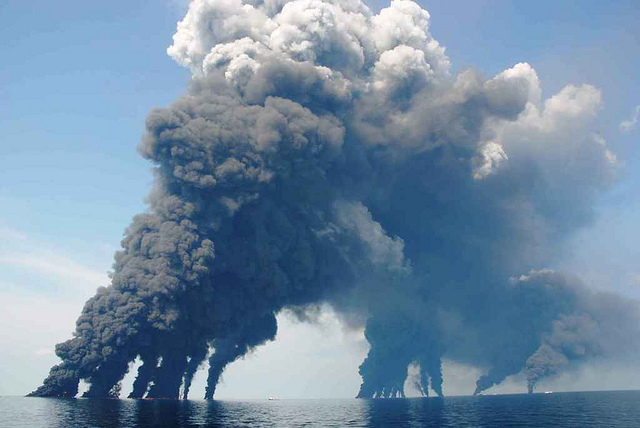

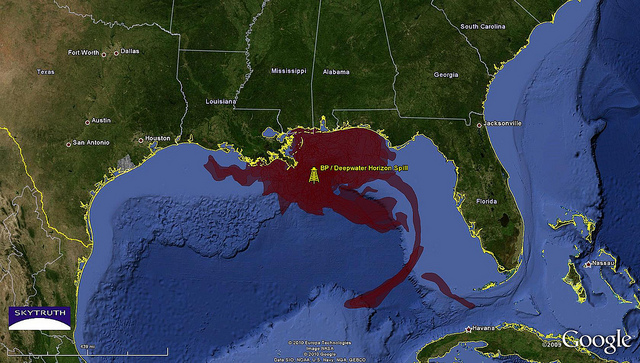

4.9 million barrels of crude oil had escaped the well by the time the flow was staunched, making the Deepwater Horizon oil spill the largest by far ever to occur in U.S.-controlled waters. Cleanup efforts involved gathering and burning the oil. (Photo: SkyTruth, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. On April 20, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico exploded, killing eleven workers as a sea bed well blew out and began spewing over 200 million gallons of crude into the Gulf. Since then, science has been trying to understand exactly how such a torrent of oil affects the marine ecosystem. The University of South Florida leads a collaboration of chemists, engineers and biologists investigating this, and as part of updating Living on Earth stories during Earth month we’re catching up on this effort. David Levin went along with the team in 2012, and here is part of his report.

LEVIN: For three straight months, oil sprayed up from the wellhead to the surface, and as it rose, vast plumes of toxic chemicals and oil droplets broke off, staying suspended in the seawater at different depths. They drifted around the Gulf like toxic clouds.

HOLLANDER: This is not a black layer in the ocean. It doesn't even look like vinaigrette when you bring it up. It looks like crystal clear water, and the reason is because they were such fine droplets that you couldn't see them.

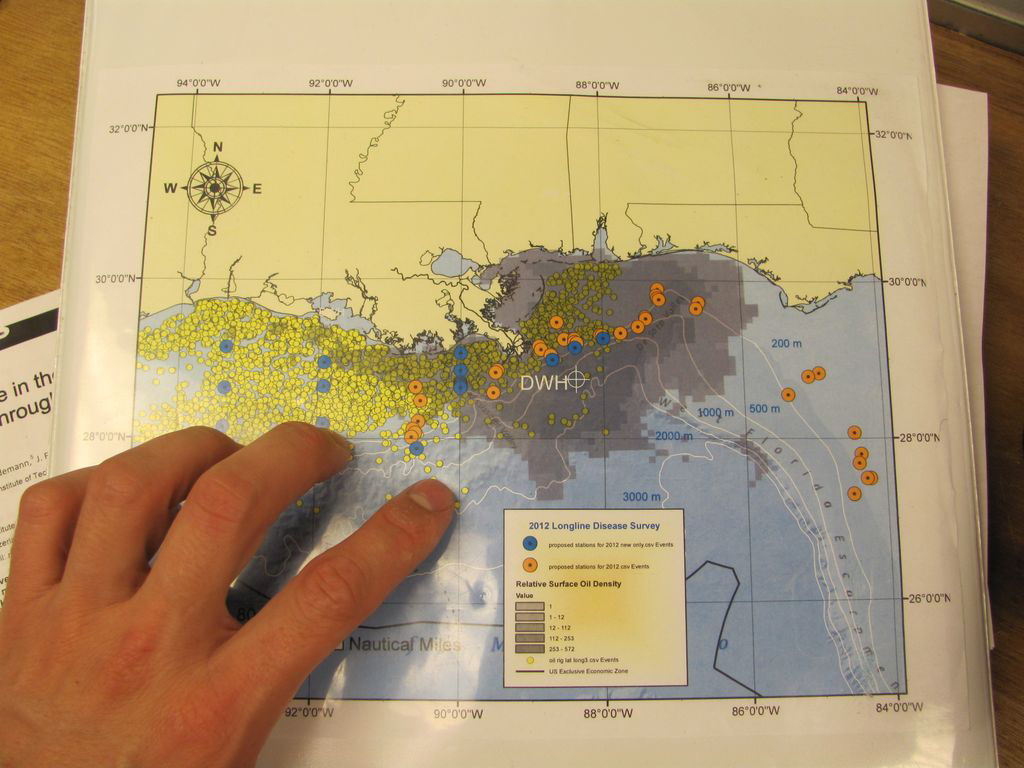

This map shows thousands of oil platforms (represented by yellow dots) scattered throughout the Louisiana and Mississippi Coast in the Gulf of Mexico. White crosshairs mark the site of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, and blue and orange circles represent C-IMAGE sampling sites. (Photo: David Levin)

LEVIN: The underwater plumes eventually floated into the continental slope. That's where the ocean falls out dramatically. It falls from a few hundred feet deep to a few thousand. When the plumes hit the slope, they left a smear of oily residue. Hollander and his team are using this cruise to visit those oil-soaked areas. Their mission: collect both sediment and fish to measure the plume’s impact on the Gulf ecosystem, from huge whales to tiny single-celled animals.

This project’s part of a larger research effort Hollander helped start at USF. He’s organized scientists from around the world to study the aftermath of the spill. The group calls themselves C-IMAGE, and this cruise is the first part of their collaboration.

[CLANKING FOOTSTEPS ON GANGPLANK, ENGINES WHIRRING]

LEVIN: For the next eight days, our home base will be here, on the Weatherbird II, a 115-foot research vessel.

WHITE: Welcome aboard, glad to finally have everybody on board. Looking at a 4 a.m. start, 5 a.m. start…

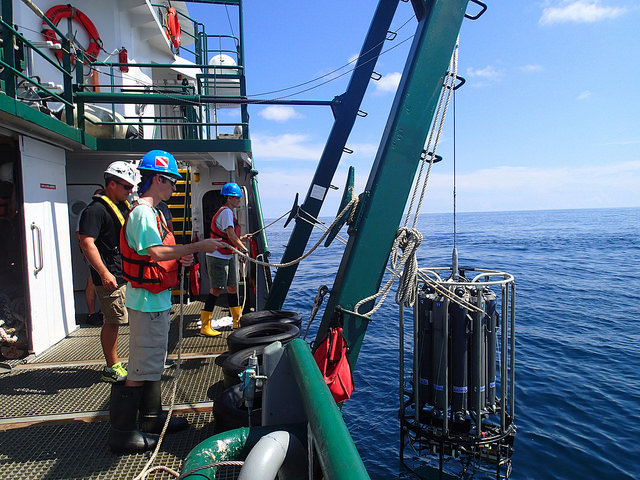

C-IMAGE scientists Patrick Schwing and David Hollander help bring in a multicorer, a device that samples sediment from the ocean floor. Inside the frame are eight thick plastic tubes that sink into the mud when the device hits the bottom, sealing the sediments inside. The samples will help Schwing and Hollander determine the extent to which oil has affected the ecosystem at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico.

LEVIN: That’s Matt White, the ship’s captain. We’re about to set sail for an area of the sea floor called the Desoto Canyon, about 60 miles southwest of the Florida panhandle. It’s one of the places where the oil plumes bumped into the continental slope.

[CRANE WHIRRING]

By midnight, we’re at our first stop. Hollander’s team lowers a device called a multicorer into the water. It’s a metal frame about 10 feet tall.

SCHWING: The multicorer literally looks like a giant spider, or a giant lunar lander…

LEVIN: Patrick Schwing is a post-doc in Hollander’s lab. He’s watching the multicorer disappear under the waves. When it hits the bottom, eight plastic tubes inside it will grab mud from the seafloor.

SCHWING: …and at that point we start pulling it back up.

LEVIN: These coring samples are crucial for understanding how the spill moved around the Gulf. They’ll help the team predict what happens to oil after a deep-water blowout, and how long it’ll last in the water. But the life of the oil is only half the picture. To understand its impact on the ecosystem, the team needs to know how fish and other animals are faring.

[ON DECK]

MURAWSKI: Look at that sunrise. That’s sharp.

LEVIN: The next day, at 6 in the morning, Steve Murawski stands on deck, holding laundry baskets full of bait.

A view forward from the stern deck of the R/V Weatherbird II, the 115-foot research vessel used by C-IMAGE, as it waits to embark on an 8-day research cruise in the Gulf of Mexico. (photo: David Levin)

MURAWSKI: It’s a combination of squid and Boston mackerel…

LEVIN: Murawski is a biological oceanographer at USF, and he’s running this research cruise along with Hollander. He’s setting up for a long day of fishing. His team is using a winch the size of a 50-gallon drum to let out five miles of metal cable. Strung out along the cable are 500 baited hooks. It’s a technique called long-lining. As the cable spools out, it settles across the bottom, attracting fish that live near the oily sediments.

MURAWSKI: It’s a unique opportunity to see what’s going on with the fishes in the really deep water. We know that there’s oil on the bottom. What we’re trying to see is if that oil is having any food chain effects.

LEVIN: Murawski thinks the toxic chemicals may have been absorbed by tiny animals that live in the sediments…like clams, snails, and worms, which all get eaten by fish. So if there’s any oil lower down in the food chain, it might end up in the fish. And if it does, Murawski wants to know. So he’s taking samples from all the species he catches on his long line.

These dogfish (actually type of shark) are common in the Gulf of Mexico, and come up frequently on C-IMAGE fishing lines. (photo: David Levin)

MURAWSKI: So what we're going to do is look at the bile, the blood, the liver, the muscle, and then some of the organs of the fish. So that should tell us number one, is there active oil in the environment, and number two, is it being uptaken by these fish, some of which are of commercial importance.

[FLOPPING FISH ON DECK]

LEVIN: One by one, fish come off the long line and flop onto the deck. Red snapper, Dogfish. Eels. Grouper. Tuna. This part of the research is grueling. Murawski and his students work in 100 degree heat, cutting out fish guts so they can test them for chemicals from the oil.…and when they’re done with that, they reach for the bone saw.

[BONE SAW CUTTING INTO FISH HEAD]

HERDTER: Whoo! Perfect!

LEVIN: Liz Herdter, one of Murawski’s students, just split open the head of a yellowedge grouper. She uses tweezers to pull out delicate bones from its inner ears. They look like tiny oyster shells.

USF Graduate student Liz Herdter carefully removes delicate inner ear bones called "otoliths" from a Yellowedge Grouper. Chemicals trapped in various layers of the otoliths provide a detailed record of the fishes' exposure to toxins throughout its life, and may help provide clues to the fishes' exposure to oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill. (photo: David Levin)

HERDTER: These are otoliths. They’re like an earstone. Steve likes to call it the flight recorder.

LEVIN: That’s because a new layer of bone forms around an otolith every year. They’re laid down like the rings of a tree, and by analyzing these layers; you can track the health of the fish over time.

HERDTER: If they came into contact with any chemicals, there’ll be a chemical marker, so they’re a really neat way to determine what’s been happening in the life of the fish.

LEVIN: Murawski’s team wants to use these samples to create a big-picture view of fish and ecosystem health in the Gulf. Even today, some fish are still in bad shape… Like the 50-pound red snapper Murawski’s holding. It’s got a skin lesion.

MURAWSKI: It’s also got a bad eye! See his eye? His eye’s gone. So this is the kind of fish we want to investigate for whether it has any relationship to oil or not.

LEVIN: Sick fish like this one don’t surprise Murawski. He thinks their bad health is connected to what’s going on in the sediments, and Hollander just found some evidence to back that up. At a work table crammed into a corner of the deck, Hollander points to one of the cores his team pulled up the night before. It’s a clear plastic tube, about two feet long and six inches wide. It’s full of grey mud, where tiny worms, snails, and clams have burrowed, mixing it all up… But a few inches from the top, that uniform grey suddenly turns brown. And that, he says, means trouble.

From L to R: C-IMAGE researchers transfer a sediment core sample into a storage tube on the deck of the R/V Weatherbird II. (Photo: David Levin)

HOLLANDER: What this really represents is where the subsurface plumes actually touched the sediment surface.

LEVIN: When the plumes hit the sea floor, they wiped out the tiny creatures that usually mix up the sediment. So after the spill, all that churning activity ground to a halt.

HOLLANDER: If there were organisms mixing this, you wouldn’t find these distinct layers, so those organisms are gone.

LEVIN: In some parts of the Gulf, they still haven’t come back. And since some fish live in and near the sediments, Hollander thinks the chemical plumes probably affected them, too, causing the liver problems and skin lesions Murawski’s been seeing. But it’s hard to know for sure. Figuring out what the toxins may have done to the fish is a challenge, and it’s tough to pinpoint which chemicals could be the culprits.

HOLLANDER: You know, you have to be able to trace the oil from its origin, through the water column, onto the sediments, and then as that material degrades, how do you follow it? Not that easy.

From top to bottom: C-IMAGE researchers Patty Smukall (USF Teacher-At-Sea), Theresa Greely, David Hastings, and Patrick Schwing process samples in the onboard lab lof the RV Weatherbird II. (Photo: David Levin)

CURWOOD: That’s marine chemist David Hollander at the University of South Florida, in David Levin's report on the team studying the long term impact of the DeepWater Horizon catastrophe on the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem. Professor Hollander is a key researcher in this effort, so we called him up to get a handle on new developments and the state of the gulf today. When he spoke to us his parakeets joined in.

[PARAKEETS CHIRPING]

HOLLANDER: We have definitive perspectives on the fisheries that are being affected and are still affected and we have an understanding of their contaminate chemistry and how they got contaminated through the sedimentary system and the deposition of oil onto the sediments. The good news is that it’s recovering. The bad news is that it's still pervasive in the area and we don't have an exact understanding of how long it will last.

CURWOOD: So, what are the affects of all this the fish life down there? What kind of clues do you have?

Above, C-IMAGE researchers lower a CTD (Conducticity, Temperature, and Depth) rosette into the Gulf to study the effects of the oil spill on water quality. C-IMAGE is a consortium of 19 institutions in six different countries studying the long-term impacts of the Deepwater Horizon and Ixtoc oil spills on the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem. (Photo: courtesy of C-IMAGE Consortium)

HOLLANDER: The clues actually come from the fish themselves. Hydrocarbons, oil in particular, it's not like a heavy metal, it doesn't accumulate in fish but actually is metabolized and when you measure these compounds, these petroleum hydrocarbons in fish liver and importantly in fish bile, we can see their prevalence in those tissues and those liquids. We've seen a decline since 2010 and 2011 of about 30 to 50 percent, and that does vary by compounds but we are still seeing the persistent contamination of the food that fish are actually consuming especially those that are associated with the bottom and those are called benthic-dependent fish and they make up some of the most important economically and recreational fish species in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

CURWOOD: For example?

HOLLANDER: The Red Snapper, for example, which is a quite common fish in restaurants as well as in recreational fishing. Grouper are another species as well.

CURWOOD: So, Professor, the situation you're seeing there. What kind of ideas, what kind of better ideas does it give us of how we should deal with a future blowout if one were to ever happen?

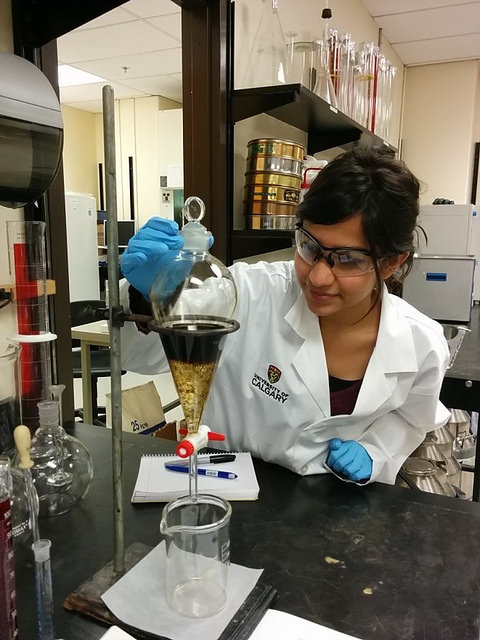

Back at the lab, researchers working with C-IMAGE run tests on samples collected from the Gulf. (Photo: Courtesy of C-IMAGE Consortium)

HOLLANDER: In the case of the Deepwater Horizon there was oil that was marching its way towards the coastline and into the marshes and so the forces that be opened up the floodgates of the Mississippi, opened up the diversionary channels to push freshwater out of the marshes and push the oil into the offshore region. But associated with those waters came a significant amount of clays and nutrients and they had a unexpected consequence, that is, the dispersants were also applied to the oil from the surface as well as oil was skimmed and burned. The oil with dispersants lends itself to smaller droplets, which very, very effectively binds with the clay minerals. The nutrients, which came out of the river system, produced an algal bloom, which in the presence of oil and dispersants, the algae produce a very mucilaginous, very sticky substance. And essentially, it's a stress response by the organisms.

CURWOOD: It sounds like oily snot.

HOLLANDER: That's precisely it. There was actually a term coined ‘sea snot’ to represent the sticky mucilaginous material. So the oil mineral aggregates would adhere very readily to that sticky mucilaginous material with the algae, and all of a sudden you had this combination of oil and mineral and algae material, which were able to sink out of the water very, very quickly. This material was falling like a blizzard, and we coined the term ‘the flocculent dirty blizzard’ because it represented really the process that was going on.

CURWOOD: Now talk to be about the state of the marshes and the rest of the gulf, the beaches, the oyster bed. How have they recovered so far?

Oil from Deepwater Horizon spread out over 3,850 square miles of the waters in the Gulf. (Photo: SkyTruth, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

HOLLANDER: The oysters were, of course, affected by the opening up of these floodgates of the Mississippi and the diversionary channels. They require a very precise range and salinity and that salinity was dropped significantly and really compromised those oyster beds. They've come back in some locations, in other locations they don't seem to have recovered as strongly. The beaches themselves look pretty good. They use a lot of physical techniques to mix up the oil with the sandy sediments, and that essentially dilutes the oil in the sediment on the beaches, but you can still find very resistant oil molecules and oil molecules that have actually transformed to very bio resistant molecules that have a long-term persistence in the environment.

CURWOOD: Obviously, preventing blowouts is the best possible way to proceed but what are the lessons we should learn as a society, especially about our relationship with oil well extraction from the research that you've done there on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico.

David Hollander is an Associate Professor of Chemical Oceanography at the University of South Florida. (Photo: courtesy of David Hollander)

HOLLANDER: I think that the take home message is that if in the event of deep water blowouts it is a complex series of chemical reactions that are occurring that can lead to really unpredicted consequences, and the standard cleanup procedures that we have can also lead to fairly unexpected consequences that we never recognize, namely the process of sedimentary oil deposition and that a significant component of the oil that's on the surface could actually return back to the sedimentary system and that this material can have a long-term biological and ecosystem consequence. If you're trying to save one part of the ecosystem you could very well jeopardize another one. With the use of the dispersants and the burning and the opening of the Mississippi...this was thought of as very little consequence to pushing this oil into the offshore regions but what we've been able to recognize is that indeed this oil has a fate and it does end up in the sediments and it is affecting biological systems and there is a consequence and ultimately there is an economic impact of this. The long-term good news is that the oil is essentially marching its way down the continental slope and so its ultimate destiny is to move into environments where there's lower biological activity but it's still there.

CURWOOD: David Hollander is a Professor of Marine Chemistry at the University of South Florida. Thanks so much for taking the time.

HOLLANDER: It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- USF College of Marine Science homepage

- USF "Adventure at Sea" blog

- The C-IMAGE website

- About the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative

- About David Hollander

- Steve Murawski's USF homepage

- Mote Marine Laboratory

[MUSIC: Locil, Zero, Triple Point, Kranky 2001]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a new view of modern humans as an invading species that used canine companions to outcompete the Neanderthals. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[MUSIC: Locil, Zero, Triple Point, Kranky 2001]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a new view of modern humans as an invading species that used canine companions to outcompete the Neanderthals. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC; Noah and the Whale, Instrumental 11, the First Days of Spring, Mercury 2009]

Patagonia's Beaver Problem

Patagonia beaver. (Photo: courtesy of Motherboard)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Think invasive species and you might picture starlings, purple loosestrife or kudzu. Or perhaps more damaging creatures come to mind — zebra mussels overrunning the Great Lakes, Burmese pythons squeezing the Everglades, or feral hogs wrecking the landscape in Hawai’i. But even furry creatures like beavers can become a problem when dropped into an ecosystem with no predators to keep them in balance. These busy, little dam-builders are profoundly affecting Patagonia, a once pristine region at the southern tips of Chile and Argentina. The online publication Motherboard recently made a documentary, entitled “The Beaver Slayers of Patagonia,” that chronicles the devastation by beavers and human efforts in response. Derek Mead is Editor-In-Chief of Motherboard, and he joins me. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MEAD: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: The headline in your story says beavers are killing Patagonia. That's a strong accusation against the small creature. What's going on?

MEAD: You know, I felt about the same way because they're such small guys, but I found out there are about 100,000 beavers in Patagonia that don't belong there. They've completely changed the entire ecology of the region.

CURWOOD: So how are beaver impacting the landscape down there?

MEAD: So part of the difference between Patagonia and North America is that Patagonia has a bit more scrubland and a little bit more of kind of a Beech forest, which is bit more dense than we would expect in North America. Trees down there when they're cut down to the levels that beavers can, when they're really cut back they're not able to regenerate the same way they are here, partly because they haven't evolved in an environment with animals like beavers. One of the biggest things you'll see is literally just a barren wasteland of all the old Beech trees that had been growing nice and tightly just cut down and just left with stumps. Basically mud. And as soon as there's rains and heavy flooding, all of that gets washed away. So you go from having a tight river with trees on both sides to just an open huge pit where there's nothing left and nothing can grow. So, they're small guys, they don't have a huge amount of territory they've destroyed on their own, but they are wrecking river systems.

A Patagonia beaver hunter. (Photo: courtesy of Motherboard)

CURWOOD: Now your story calls beaver ‘furball hydrologists’. What exactly do they do to deserve that moniker?

MEAD: Well, you know, they're incredibly good engineers. Their whole goal is to build themselves dams and they're very industrious and so chopping down trees and diverting rivers, they're able to pretty much completely reshape a river system to the detriment of everything else there.

CURWOOD: How did they wind up in Patagonia?

MEAD: In 1946, 25 pairs of Canadian beavers were brought to the region to hopefully kickstart a fur trade. Initially the industry just didn't take off; it had a lot of trouble getting momentum, partly because you know there's a lot of trapping elsewhere.

CURWOOD: And what are the natural predators of beaver in South America?

MEAD: Well, that's kind of the rub is that they don't really have any natural predators in South America and the goal was to have humans be their predators and turn them in the fur coats and everything else.

Distribution of North American beaver, C. canadensis. (Photo: Wikipedia CC)

CURWOOD: So what's the legal situation for beaver? In the film we see a chef preparing beaver meat for customer dinners.

MEAD: Well, right now there's a big emphasis on, from both the Chilean and Argentinian governments to try to get both government people and any old hunter to try and kill them because that's the best way to manage them right now, set up traps, hunt them...versus trying to poison them en masse or something like that. Because of that, it's pretty much a free-for-all for hunting beavers right now which is why you have a chef cook them up with no trouble.

CURWOOD: So, Derek, what's the lesson for people engaged in conservation and ecological management here?

Derek Mead, Editor-In-Chief of Motherboard. (Photo: courtesy of Motherboard)

MEAD: I think the main lesson here is the fact that there's a natural balance that's really been able to settle in for most ecosystems, and as soon as you throw in a huge wrench into the works it's really hard to bring the balance back. Patagonia has been a similar way for a very, very long time, and throwing in beavers have thrown off tens of thousands of years in just seven decades. The key thing is to be able to protect ecosystems and try to keep them as natural as possible from the very beginning. But should there be a natural disruption, getting them back to what we know of, as the natural balance is the most important thing we can do.

CURWOOD: Derek Mead is Editor-in-Chief of the online publication Motherboard. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

MEAD: It’s been fantastic being here. Thank you.

Related links:

- Motherboard’s “The Beaver Slayers of Patagonia”

- A study on the eradication of invasive beaver, an ecosystem engineer, threatening southern Patagonia

- Argentina and Chile imported the beaver in 1946 and are now fixing their mistake

The Invaders

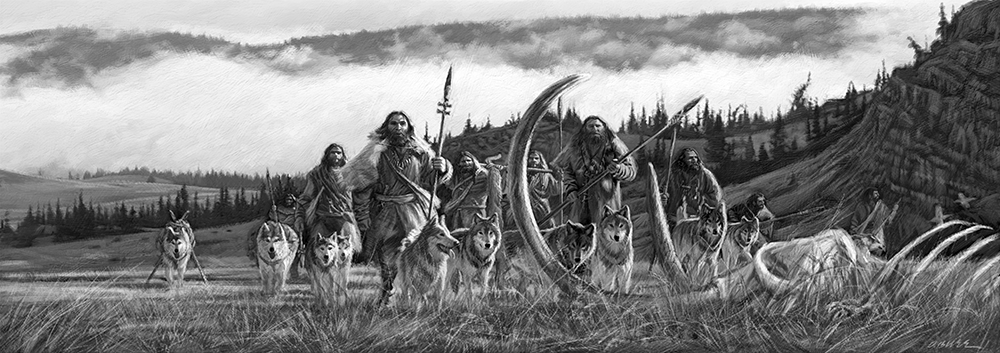

Pat Shipman, a retired Professor of Anthropology at Penn State, used new anthropological findings to argue in her book The Invaders that modern humans and their canids drove Neanderthals to extinction. (Illustration: © 2014 Dan Burr)

CURWOOD: And now, a provocative view of modern humans.

SHIPMAN: We have been the most successful invasive species as far as I can think of. We have moved out of the place where we evolved, in Africa, into Europe and Asia and now the Americas, and just about every place that it would be possible to live, and we're doing astonishingly, or maybe appallingly, well.

CURWOOD: That’s Pat Shipman, a retired Professor of Anthropology at Penn State University, whose new book "The Invaders" makes the case that our partnership with domesticated wolves gave us a competitive edge over Neanderthals, hastening their extinction. This is a different hypothesis from those previously put forward for why Neanderthals died out, and new techniques of carbon dating suggest this all happened both earlier and faster than previously believed. Pat Shipman, welcome to Living on Earth.

SHIPMAN: Thank you for the invitation.

CURWOOD: So this is a new concept, a new hypothesis. What did we used to think the reason was that Neanderthals went extinct?

SHIPMAN: The dominant theory until lately has been climate change. There certainly was a rapidly shifting climate starting about 45,000 years ago, and it went from colder and dryer to warmer and wetter and back again pretty rapidly by a geological time scale. And it certainly had an impact on vegetation, on the other animals, so of course it had an impact on Neanderthals and modern humans. However, Neanderthals had lived through several episodes like this before, that were as cold and dry as what happened in that crucial time period of overlap. So there's no obvious reason why they would have been unable to cope with it and modern humans would have been less hindered, except, of course, we had dogs. Another one was, oh, they're just too stupid, and we have so much evidence now of some very sophisticated things they did, that I don't think that holds up very well. They had survived for hundreds of thousands of years. They may not have been as adaptable, they may not have been as good at communicating with dogs, but they weren't the old-style Neanderthal saying "Ugg". That's kind of a slander against them. They were better than that. So I think there's something wrong with many of the theories that have been put forward by now that we owe to the new dating improvements and we owe to these very sophisticated techniques for identifying dogs as dogs.

CURWOOD: So, what has changed now that we have the technology that gives us a more accurate view, at least we think we have a more accurate view, of when things happened? What's different now about what happened to the Neanderthals and us for that matter?

SHIPMAN: OK, we now would say based on the dates we have at present that modern humans got into Eurasia perhaps 42,000 years ago, maybe 1,000 or 2,000 years earlier than that. Neanderthals had already been there for a couple of hundred thousand years. What used to be believed with fair reason because that's what the technology of the time told us was that Neanderthals then hung on until about 25,000 years ago when they went extinct, so that would be a 20,000 year period of overlap. The new dates now tell us that 20,000 years may only have been 2,000 years so it's a pretty rapid event after the arrival of modern humans.

A Neanderthal skull (Photo: Paul Hudson; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So some 40,000 years ago, 42,000 years ago you suggest Neanderthals start to go extinct just as little as 2,000 after modern humans show up in Europe. What happened?

SHIPMAN: To try to answer this, I took a look at what we know about the effects of invasive apex predators, that is top predators. And I turned to events in Yellowstone National Park in the American west where 31 gray wolves were released into the park. Now, there had not been gray wolves in Yellowstone National Park in the immediate area since the very early 1900s. So the Yellowstone National Park that most of us have grown up with is actually an impoverished ecosystem because we took out the top predator or certainly one of the top predators. When they came back in to rebalance and restore the original ecosystems some very fascinating things happened. Coyotes, which are of course doggy animals not that different from wolves except primarily in size, got absolutely hammered. The overall population of coyotes in the park dropped by 50 percent. So what that tells us in a very simple analogy is when a new apex predator comes then it strains the whole ecosystem and the predator that's already there that is most like the new one is the one that feels the competition most keenly.

CURWOOD: Oh my God. So, humans, sort of like a well financed person in Manhattan, just simply bid the ecological space up out of sight for the Neanderthals, it sounds like.

SHIPMAN: Yes, basically that's it. It was already a crowded ecosystem with a lot of very able predators and very shortly after we arrived Neanderthals went extinct and you can then tick off different species different kinds of predators and even different kinds of prey that eventually went extinct.

CURWOOD: So what's fascinating about your book is it you say that modern humans move into the turf of the Neanderthals and start to push them out of the way as top predator but physically of course the modern human was perhaps smaller and had a lot less strength that the Neanderthal, and you also say that probably intelligence was comparable. So you came up with a rather interesting hypothesis as to why humans win this battle of being the top predator. What's the core of your idea here and why are wolves, or rather dogs involved in that?

SHIPMAN: In 2009, a Belgian colleague of mine, Mietje Germonpre and group of international researchers worked out a way to tell from the fossils alone what was a wolf and what was a dog. And then once they had established that the system worked, start throwing in canid skulls from the fossil record. One of the first groups of canids they looked at involved a skull from Goyet cave in Belgium and it turned out to classify as a dog. So they had the skull redated with the new dating techniques. It came out to be almost 33,000 years old; it might be as much as 37,000 years old. This was at least 20,000 years older than anybody had expected and as they continued to use this system they found more and more and more of these animals that I call ‘wolf dogs’. And they now have identified over 40 individual wolf dogs from various sites in Central and Eastern Europe. And these turn up very, very shortly after Neanderthals went extinct think so I'm willing to say what that this was a major advance in lifestyle and hunting efficiency for modern humans and all of these wolf dogs turn up in modern human sites. There are none in Neanderthal sites.

Modern humans and early wolf-dogs teamed up and out competed Neanderthals, driving them extinction in possibly as little as 2,000 years. (Illustration: © 2014 Dan Burr)

CURWOOD: So modern humans had domesticated the wolf and turned the wolves into hunting buddies, your book says.

SHIPMAN: Yes, basically. I don't want people to be thinking about hunting dogs now, which have had a long time to evolve and be especially bred for different tasks involved in hunting. But wolves are of course hunters. They are pack hunters. They're used to cooperative hunting, and what I think was going on was that modern humans managed to get at least a somewhat domesticated wolf dog that could live with them, could hunt with them, providing benefits to both partners, but that made them a much more efficient hunter than they had ever been before.

CURWOOD: Explain to me what the deal was for the wolf dog and what the deal was for the human.

SHIPMAN: For the wolf dog there would be several significant advantages. What I believe happened is that wolf dogs would do what wolves often do with big prey, that is they'd isolate one individual, they'd surround it, they'd drive it away from the others and hassle it, threaten to attack it, maybe take a good chunk here and there until the prey animal was exhausted, couldn't run anymore, but was still feisty. Now a wolf would then have to go in and pull that animal down. That's where they get hurt. However, if you have modern humans working with you, at that point the modern humans kill the animal with a bow and arrow or a spear with a spear thrower. Nobody gets hurt and they can actually prevent other predators from coming in and stealing it. But they can share the task. So you get more prey, you get it faster; you get it with less risk and less energy expenditure.

CURWOOD: So if humans and Neanderthals had similar skills and intellect, how come Neanderthals didn't domesticate the wolves?

SHIPMAN: I don't have an answer based on evidence. I can give you some answers based on speculation. Neanderthals appear to have been less adaptable than humans. Another issue is there is a signal that humans can give that is very important in cooperative hunting. We read direction of gaze. We use that without even thinking about it to make predictions about what another person is going to do. We are the only primate in the world that have white sclera, that is, the whites of our eyes surrounding the dark colored iris. If I look at you and I want to signal you something about the animal we’re hunting together I can look at you, look over at the animal, or look at the direction I'm going to go, look at the bush I'm going behind and you can read that from a considerable distance, I don't have to shout and wave my arms and do all kinds of obvious things. Dogs are very, very, very good at reading direction of gaze. Wolves for a nondomestic canid are rather good at reading direction of gaze, but in fact, they're not looking to people for guidance or cooperation or anything else. They would like to get on with their wolfy thing and would like you to get out of the way. So that wolves and animals that hunt in packs like that tend to have not big visible whites of the eyes as we do and as dogs do relative to other dogs, but they have contrasting fur around the eye so that you can see the direction of gaze. One of my speculations is that Neanderthals didn't have this. Maybe they didn't have whites to their eyes. It's such a rare trait in primates maybe they never evolved it.

A map depicting the range of Homo neanderthalensis. (Photo: Nilenbert; CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: This is the same trait that people playing American football -- defenders use. They look where the quarterback is looking to see where he is going to throw the ball.

SHIPMAN: That's exactly it.

CURWOOD: Of course, there's always a question. How does this begin? How did the modern human bring the wolf in and the domesticate the wolf or is it the other way around? Did the wolf domesticate the human?

SHIPMAN: Well, there certainly is a two way relationship going on. The way it probably happened - here's speculation again - is starting with pups. I'm guessing because it's such a normal human thing to do, somebody at some time picked up a lost puppy. It was little, it was cute, it was fuzzy. They took him home; they kept it around. If it got obnoxious they killed it and ate it. If it was a little less aggressive or a little more cooperative, maybe they continued to keep it around and later brought a second one in and so on. And so I think it has to have happened by accident. There was a very dominant theory that wolves might have actually domesticated themselves by hanging around village dumps, garbage dumps when there were first villages and towns. There are two points that mitigate against this idea. One is if they were really, around 40,000 years ago there weren't any permanent settlements. There weren't any garbage dumps so that's not going to work. The other side of it is that in fact wolves who are exposed to humans, who feed off garbage dumps now, who watch humans, those are the ones that are more likely to become aggressive and attack. So my money would be that it started almost accidentally with somebody taking home wolf puppies and over time you got a progressively more and more domesticated animal that understood people better, that communicated with people better and they kind of liked hanging around the campfire with people. So it's that ability to work with us, to work cooperatively, to add their skills to our skills, is a long and ancient story.

CURWOOD: Pat Shipman is author of "The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction". Thanks much for taking time with us today.

SHIPMAN: Thank you.

Related link:

More about Pat Shipman’s The Invaders

[MUSIC: Ego Likeness, Wolves, Water to the Dead Metropolis 2013]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, remembering pioneering scientist Theo Colborn.

VANDENBERG: I was extremely privileged to work with someone like Theo. She really took a stand for the sake of planet earth and human health.

CURWOOD: Her research raised the alarm about endocrine disrupting chemicals. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Geroge Clements, Santa Fe, Reason for Flight, Metropolis 2013]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us any time at LOE.org and like us please at our Facebook page it’s PRI’s Living on Earth, and we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth