May 15, 2015

Air Date: May 15, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Tornado Clusters

View the page for this story

Tornadoes are highly destructive weather events that now seem to arrive in clusters, up to 30 at a time. Host Steve Curwood hears from climate professor James Elsner, of Florida State University, how his study suggests that with climate change there are fewer days with tornadoes, but when they do come they are in clusters and more powerful than before. (06:50)

Talcum Powder Linked to Ovarian Cancer

View the page for this story

Talcum powder has been used for decades as a lubricant, in cosmetics and for personal hygiene, and for diapering babies. But studies going back years have suggested a link between talc and ovarian cancer. Now women with this cancer are suing Johnson & Johnson, claiming the company kept quiet about the product’s putative dangers. Myron Levin of the public health focused news-site FairWarning.org, discusses the lawsuits and the possible risks of talc with host Steve Curwood. (07:15)

Honoring an Environmental Health Pioneer

View the page for this story

Dr. Frederica Perera has been lauded as a tireless champion of children’s health by the Heinz Family Foundation which awarded her its 2015 Environmental Prize. Dr. Perera, a professor of Environmental Health Science and founding director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, tells host Steve Curwood about her pioneering epidemiological research on the consequences of prenatal chemical exposure and argues that exposure control and prevention could help mitigate diseases down the road. (07:20)

Driving Down Diesel School Bus Emissions

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

In the US diesel fuel powers mostly trucks and buses, and the exhaust contains thousands of chemicals and over 40 toxic air contaminants. This is particularly hazardous to children, who ride diesel school buses and are exposed to the fumes, especially when buses idle beside schools. But as the Allegheny Front’s Julie Grant reports, new EPA legislation, funding and technology are cutting school bus emissions. (05:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about the continuing, slow collapse of coal investments; how Shell won approval to drill for oil in the arctic, despite many unfavorable conditions; and that experimental forest areas have provided scientists with important acid rain research. (04:20)

The Puffin Project

View the page for this story

When National Audubon Society Vice President Steve Kress first began his quest to restore the historic puffin population on a small island off the coast of Maine, he had no idea it would become his life’s work. That journey is the subject his new book called Project Puffin, co-written with Boston Globe editor Derrick Jackson. Kress describes the long and difficult process to host Steve Curwood, and discusses how some of the lessons he learned could help conservationists trying to protect other bird species. (16:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: James Elsner, Myron Levin, Frederica Perera, Derek Jackson, Steve Kress

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Experts believe global warming will make weather systems more volatile and energetic, and some think there might already be some signs in tornadoes.

ELSNER: Yeah, I mean, I think climate change is having an effect on the tornado activity. There are some ominous indicators, especially with the clustering and perhaps with the length and width of these tornadoes.

CURWOOD: Also, reducing pollution from school buses, and a major award for a pioneering researcher who identified toxins making children sick.

PERERA: Once we identify as harmful environmental exposures, they by their very nature are preventable. And the potential benefits are huge. The costs of childhood illness due to environmental contaminants were estimated at $76 billion.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Tornado Clusters

June 16, 2014, twin tornadoes touch down at 4:15pm off US route 275 north of Pilger, Neb. (Photo: video screen grab courtesy of James Elsner)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. A warmer world is leading to more volatile weather events including extremes of heat and cold, and rainfall. 2014 was the hottest year on record, and with the rising concentration of greenhouse gases that trend of extremes will likely get worse, but it’s a challenge to predict how that might affect tornadoes. It’s not that there are more of them, but there do seem to be more ferocious bursts of tornado activity – with the biggest more than a mile wide and as many as 70 touching down over a couple of days recently.

Professor James Elsner of Florida State University has been looking into the possible links between climate change and tornado behavior, and published some results of his work in the journal Climate Dynamics.

ELSNER: The number of tornadoes from year to year doesn’t change very much. We get about 1,000 tornadoes a year, some years more than others. But there's no long-term trend, so we looked at instead is how many days are there with tornadoes? And we found that there's actually fewer days in which tornadoes form and so that means that a day with tornadoes has to have more tornadoes if the total number isn't changing.

CURWOOD: Why do you think that is? Why are tornadoes bunching up?

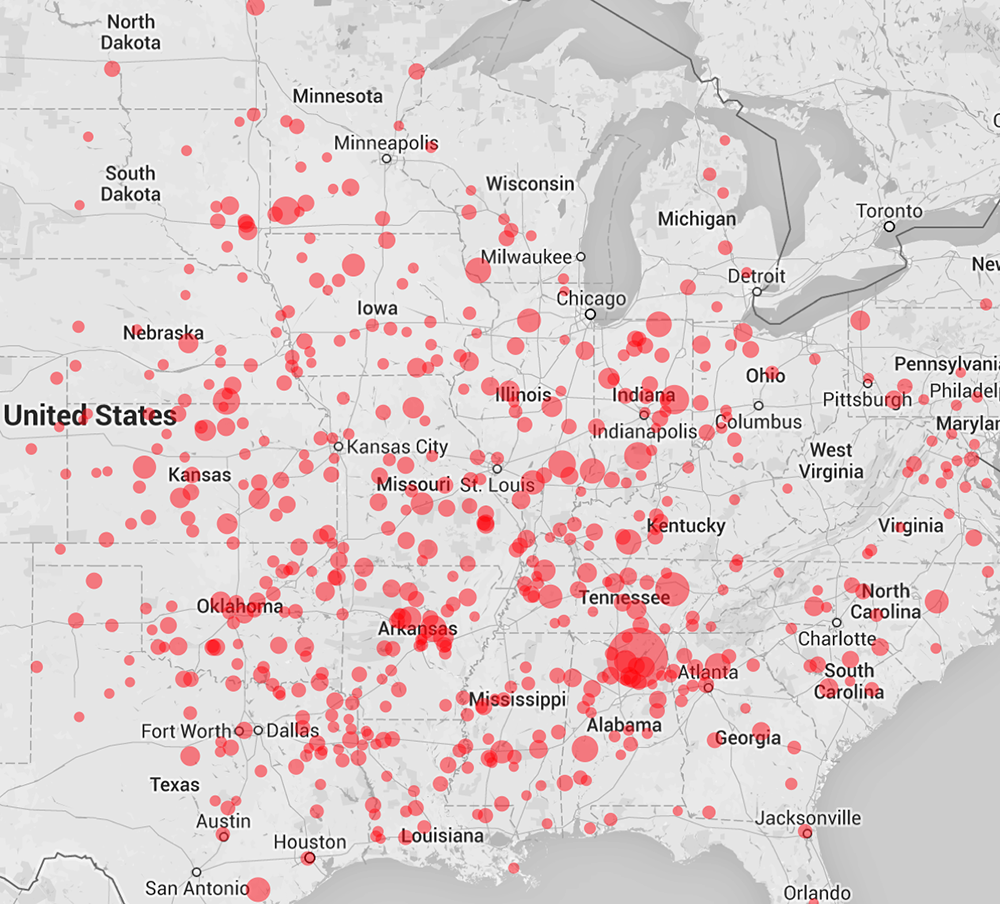

Medoids of all clusters over all days with at least 16 tornadoes (1954--2013). The size of the circle is proportional to the number of tornadoes in the cluster. (Photo: James Elsner)

ELSNER: Well, it's not clear yet. What we speculate is happening is as the climate warms were seeing more moisture in the air, more humidity. And that's really the fuel for tornadoes. But at the same time the higher latitudes are warming faster than the lower latitudes, and so that tends to decrease the amount of winds that are blowing aloft above the ground. And so you need both of these ingredients; you need strong winds blowing above the ground and you need humidity to create the conditions for tornadoes. And so it seemed like it a kind of a draw. So it appears that even though we're seeing less or slower winds, when they do blow fast on occasion then the extra humidity creates days with lots of tornadoes.

CURWOOD: So tornadoes are now occurring more in clusters. How close together are they and how long between touchdowns?

ELSNER: On a given day we can get a family of tornadoes. We can get a single thunderstorm producing a tornado. We call that a super cell thunderstorm and that tornado then can then last anywhere from just a few minutes to 20 or 30 minutes on average, only about five to six, maybe up to 10 minutes. But then it can recycle and as the storm continues to move downstream, maybe an hour later, two hours later it can produce another tornado. So we're seeing this type of thing happened more regularly.

CURWOOD: Typically how many tornadoes come in these clusters?

ELSNER: Well that can range. We can see a single isolated tornado, but what were seeing is generally between 10 and 30 tornadoes in a given cluster.

CURWOOD: Wait, you said 30 tornadoes on the same day near the same place, really, or in the same storm system?

ELSNER: Yes, well I mean, not at the same location exactly, but over an area the size of eastern Kansas, for example. I mean, I think the fact that they are bunching up both in space and time is cause for some concern.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the United States has more tornadoes than any other country in the world. Why is that?

ELSNER: Well, the United States is in a unique position, at least in the central US, in that there is a mountain range to the west that runs mostly north to south, the Rocky Mountains. And then, in close proximity to that, the Gulf of Mexico, and the gulf provides the source for the heat and moisture, and when that starts flowing north in the spring time, that encounters the fast-moving winds above the ground flowing over the Rocky Mountains. And so those are the conditions that tend to produce the tornado outbreaks.

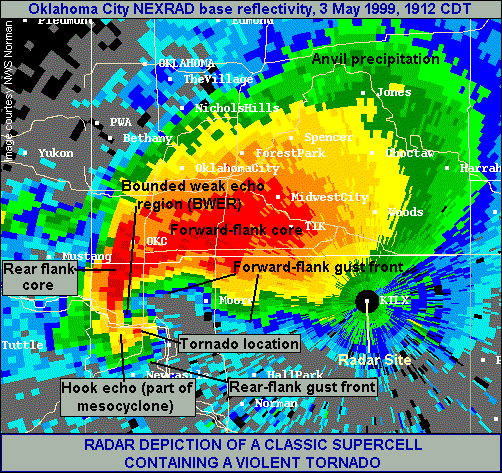

May 3, 1999, a radar image of a violently tornadic classic supercell near Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. (Photo: Storm Prediction Center, NOAA/National Weather Service)

CURWOOD: What about the strength of these tornadoes? How do today's tornadoes compare to the ones a decade or two ago do you think?

ELSNER: Well, we've been working on that problem also. I think that question is important but it's difficult to determine from the data we have because there've been changes in how we record tornadoes over time, but there are some indications that tornadoes are lasting a little longer, they're staying on the ground a little longer, so their paths are getting longer, their widths are also getting longer, the damage width is getting longer. So this indicates that they have more energy then they did in the past. Again,

it’s not clear whether that trend is due just to better ways of surveying the damage or whether that's part and parcel of this warm or warm waste atmosphere that allows the tornado to stay on the ground longer and become more ferocious.

CURWOOD: What does your work tell you or suggest about the future of tornado events as, well, the climate continues to warm?

ELSNER: Well, most of my research is based on looking at the historical record and so it's difficult to just extrapolate these trends that we are starting to detect into the future without a strong theoretical background of why this is occurring. So that has to be worked out yet. But there are some ominous indicators especially with the clustering and perhaps the length and width of these tornadoes, and so I think we have to pay attention, we have to do more research, try to understand why this is occurring.

CURWOOD: Number one suspect...climate disruption?

James Elsner is a Florida State University professor specializing in hurricanes and tornadoes (Photo: Matt Coker and Chris Frohsin)

ELSNER: Yeah, I mean I think climate change is having an effect on the tornado activity. I don't think folks would have imagined this even 10 years ago but I think there is a connection and you know it may not manifest itself in the next couple of years, but I think there is some indication that we could see more powerful tornadoes, longer-lasting tornadoes and just more of a cluster of these tornadoes going into the future.

CURWOOD: James Elsner is a Professor at Florida State University and co-author of the paper "The Increasing Efficiency of Tornado Days in the United States." Professor, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ELSNER: You’re welcome.

Related links:

- Climate Dynamics Study: “The increasing efficiency of tornado days in the United States”

- Tornado statistics on NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center

- 10 Worst US Tornado Outbreaks

- Tornado Watch Summary for 2015 to date

- James Elsner is a Florida State University professor studying hurricanes and tornadoes

Talcum Powder Linked to Ovarian Cancer

Many women use talcum powder as part of their daily feminine hygiene routine. But epidemiological studies establish a correlation between talc use in the female genital area and ovarian cancer, and call its safety into question. (Photo: Austin Kirk, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, think talcum powder, and you’re likely to picture chortling babies and smiling moms changing diapers. Nothing seems more safe and wholesome, and indeed, many women use talc daily as well, for feminine hygiene and after showering.

LEVIN: Shower to Shower, marketed to women...a sprinkle a day keeps odor away...and Johnson's Baby Powder, which is a more than a 100-year-old product, one of the legacy original products of the Johnson & Johnson Company.

CURWOOD: That’s Myron Levin, founder of FairWarning, a news site that focuses on public health, safety and environmental questions. He’s just written an article about long-held concerns about talc’s possible association with ovarian cancer, and the hundreds of lawsuits filed on behalf of women or their survivors against Johnson and Johnson. Myron Levin joins us now. He says these studies go back a long way.

LEVIN: Yes, at least to the early 70s when a British study, actually 1971, reported that an analysis under microscope of 13 ovarian tumors found talc particles in 10.

Johnson & Johnson asserts that because there is no proven mechanism for how talc might cause ovarian cancer -- only theories -- it cannot be held liable for failing to warn women of the potential risk, despite research that dates back decades. (Photo: Austin Kirk, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And since then there've been a number of studies in the US and in Europe as well I gather.

LEVIN: Yes that's true there've been a number of studies beginning in 1982 and many others to follow which not universally but in most cases certainly have found that women who used talc for feminine hygiene have higher rates of ovarian cancer than women who don't, on average about a 35% higher risk.

CURWOOD: That's a significant risk if you use talcum powder, but those studies don't offer a mechanism for this or prove that it is causal so what are the ideas here?

LEVIN: Well the idea is that the talc can travel through the genital track to the ovaries and that the inflammation that then is caused by talc particles being deposited there leads to cancer.

CURWOOD: Talk to me, Myron, about the statistics on ovarian cancer and what proportion could possibly be linked to talc?

LEVIN: There in the neighborhood of 21,000 cases diagnosed in United States every year and about 14,000 people die a year. Researchers who believe there is a definite causal link say that use of talcum powder could be the cause of up to 10%, or in the neighborhood of 2,100 cases of ovarian cancer a year.

CURWOOD: So this is an issue that goes back some 40 years. Why is it coming to the fore today?

LEVIN: Well, as you know, much of what constitutes our regulatory system in this country now is the civil courts. Decisions probably that should be made somewhere else are resolved by people filing lawsuits against major companies and scientists and experts being arrayed on both sides to argue about what the evidence is, and that's why this is happened. There was a lawsuit that was tried to a verdict in 2013. A woman named Deane Berg who had ovarian cancer asserted that this caused her use over many years of talc powder for feminine hygiene sued Johnson & Johnson. The jury found that Johnson & Johnson was liable for not warning of the risk of ovarian cancer, but strangely awarded no damages to Deane Berg.

Deane Berg, an ovarian cancer survivor, filed a lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson in 2013 for negligence: failing to warn consumers of the risk of ovarian cancer. (Photo: courtesy of Deane Berg)

CURWOOD: What you make of this verdict?

LEVIN: It's kind mystifying, isn't it? She was stage III, her prognosis was very bad, but she's doing very well and so she didn't die, OK. But she certainly suffered financial losses from missed work, from medical bills, tremendous amount of pain, some permanent loss of feeling in her hands and feet, some hearing loss, and so if you find that they should've warned her and they didn't you would think that they would give her some money. We tracked down the jury foreperson and asked her about this, and she just said that we thought they should have put a warning on but we did not believe that the medical evidence was so persuasive that we concluded that her cancer actually was caused by her use of talc.

CURWOOD: How many cases are now pending against Johnson & Johnson by women who feel that they were exposed to things that led to ovarian cancers as a result of using the J&J products?

LEVIN: There are in the neighborhood of 700, most of them in St. Louis and in New Jersey where Johnson & Johnson is headquartered. But the numbers are still going up, so there probably will be more.

CURWOOD: How are folks bringing these claims addressing the mechanism question?

LEVIN: Well, they did offer theories about how it happened in the Berg case, that's the only case that's been tried but proving things to a scientific certainty is not necessarily required in a civil trial. It has to be more probable than not in the minds of the jury that harm was caused by the defendant. So even if that isn't proven to the satisfaction of Johnson & Johnson or to many scientists, it doesn't mean that they're home free.

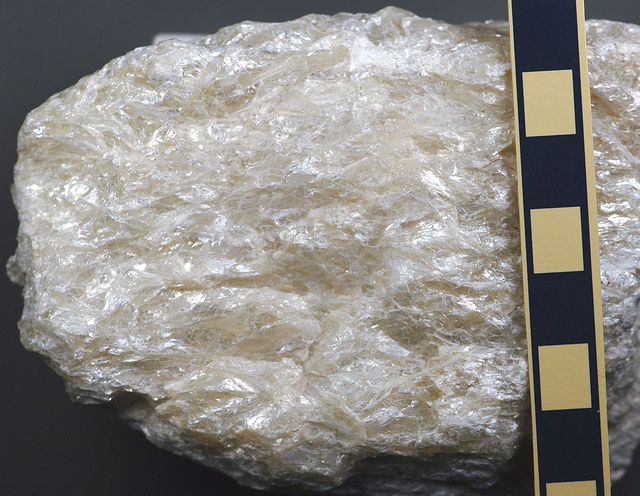

Talc is the softest-known mineral, softer even than the human fingernail. While asbestos is often found in talc deposits, Johnson & Johnson claims that asbestos is not present in its talcum powder products. (Photo: James St. John, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What's Johnson & Johnson's argument when it comes to this association?

LEVIN: Johnson & Johnson says talc powder does not cause ovarian cancer so we had no reason to warn. They say that there's no biological mechanism for causation proven and the types of studies generally that found a higher risk introduced what's called recall bias because people who have an illness or any kind of adverse health outcome tend to number of exposures or habits or things they did better than people that are healthy, so it makes it appear in other words that more people who have ovarian cancer use these products than didn't.

CURWOOD: What regulatory bodies have determined that talc may in fact be carcinogenic?

LEVIN: IARC, the International Agency for Research on Cancer which is part of the World Health Organization considered this in 2005 and 2006 and came to a finding that talc was what they call a ‘2B possible human carcinogen’ when used in this manner. There's a lot of products that are in that category and so the industry has tried to sort of dismiss this as being insignificant, but they were very, very upset when this happened. Basically what IRC said was that there's a remarkable consistency of these epidemiological studies. On the other hand confounding factors and biases can't be ruled out. But other agencies have considered this and decided to make no finding because there wasn't enough evidence.

CURWOOD: And what attracted you to this particular story?

Myron Levin is the founder and editor of FairWarning, a nonprofit (501 (c) (3)) investigative news organization that “focuses on public health, safety and environmental issues and related topics of government and business accountability.” (Photo: courtesy of Myron Levin)

LEVIN: You know, we're in a world of very ominous sounding, unpronounceable chemicals. What could be seemingly less ominous than talc? It's only four letters, we put it on babies’ bottoms, it's in all manner of industrial products as well as consumer products that are used up close and personal. You just sort of have no idea if you're the ordinary consumer that there might be a risk here.

CURWOOD: Myron Levin is founder of the investigative journalism site FairWarning, thanks so much for taking the time today Myron.

LEVIN: Well, thank you.

CURWOOD: There is more information about the suspected links between talc and ovarian cancer, Johnson and Johnson’s statement and Myron Levin’s reporting at our website, LOE.org

Related links:

- FairWarning.org: “Talc-Ovarian Cancer Links Sparks Growing Legal Battle”

- American Cancer Society on Talcum Powder and Ovarian Cancer

- Johnson & Johnson’s statement on the safety of talc in its products

- Understanding Ovarian Cancer

[MUSIC: Bright Eyes Middleman Cassadaga 2007 Saddle Creek]

CURWOOD: Coming up...honoring a pioneer in children’s environmental health. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dick Hyman Group Featuring Howard Alden, I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles Music from the Motion Picture Sweet & Lowdon 1999 Sony]

Honoring an Environmental Health Pioneer

2015, Dr. Perera receives her Heinz Award. (Photo: Josh Franzos)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. She’s “a tireless champion of children's health”. That’s the accolade Dr. Frederica Perera received as she recently won the 2015 Heinz Environmental Award. The jurors honored Dr. Perera with the $250,000 prize for her “research and advocacy that laid the groundwork for a robust body of evidence on the links between environmental toxins and childhood disorders.”

Dr. Perera is Professor of Environmental Health Sciences and Founding Director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health. She joins us now on the line from New York. Welcome to Living on Earth and congratulations.

PERERA: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: So, you've done so many things over the years. What were some of the watershed moments for you?

Dr. Perera pioneered the field of molecular epidemiology with her studies of the effects of prenatal and childhood exposure to environmental toxins. By examining chemicals in newborn cord blood and conducting epidemiological studies that followed children into adolescence, Dr. Perera and her colleagues found that the developing fetus is prone to chemical exposure. (Photo: lunar caustic, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

PERERA: I think the watershed moment was in the early 1980s. I was researching environmental causes of cancer, specifically lung cancer, and at that time I really did not know or understand the extent to which children were being exposed to environmental contaminants even before they were born. I was using DNA from what were thought to be pristine control cord blood placental samples from newborns in these studies of adult cancer and to my surprise I found that is so-called pristine untouched samples from newborns showed molecular fingerprints not only of exposure but of DNA damage linked to cancer and that was a real wake-up call for me to go ahead and learn more about the potential risk from these very early exposures.

CURWOOD: What sorts of chemicals were you seeing in that blood?

PERERA: I was interested in getting a biologic marker or molecular fingerprint of exposure in blood of the chemical that is found in air pollution from combustion of fossil fuel like traffic emissions, coal plant emissions, oil burning and also it’s found in tobacco smoke. It's a powerful carcinogen and it's called benzo[a]pyrene. It's a PAH or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. And it definitely should not have been in those samples from newborn babies, I thought, and we really needed to learn more. This early work let me with my colleague Bernie Weinstein to propose a whole new approach to the study of environmentally related disease. We called it molecular epidemiology because we were incorporating molecular approaches into epidemiology, which is the study of causes of human disease. And the whole idea here was to use this approach to prevent disease, helping us understand the links between exposure and disease and flag risks early before disease was entrenched so we could actually do something about it to interrupt the process.

Tobacco smoke is a source of benzo(a)pyrene, a carcinogen that’s classified as a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH). While studying lung cancer in adults, Dr. Perera was surprised to find benzo(a)pyrene in a control sample of newborns’ cord blood, prompting her to study prenatal and childhood exposure to environmental toxins. (Photo: Justin Masterson, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some of the practical applications of what you discovered, this molecular epidemiology approach that you developed.

PERERA: I and my colleagues have applied it here to better understand the causes of the diseases in children that are so common and were escalating back when I was beginning - childhood asthma, obesity, ADHD, autism - and we found that not only did air pollutants play a role but also that we were finding many different synthetic organic chemicals in blood or urine from pregnant mothers and also from the newborn cord blood and they included bisphenol A and phthalates, both found in plastics, the flame retardant PBDEs, and pesticides like Chlorpyrifos. And so we used this tool to study to enroll pregnant women and follow their children from before birth to learn about the impacts on children's health and development of the mother's exposure during pregnancy. And these studies occurred in, not only New York City, but Poland and China. And we have found evidence that all of these exposures can play a role in various of the health outcomes that we were concerned about in children; neuro-developmental problems and even increased risk of cancer, and very strikingly we found some evidence that certain of these exposures may also alter the anatomical development of the brain early on.

CURWOOD: What are the largest sources of the chemicals of concern?

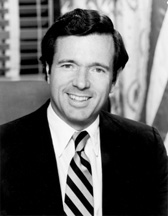

Senator John Heinz earned a reputation for protecting the environment by his involvement in “Project 88,” which recommended market-based solutions to environmental problems, the Pennsylvania Wilderness Act, and his chairmanship of GLOBE USA (Global Legislators for a Balanced Environment). He served in Congress as a Representative of Pennsylvania from 1971 to 1976, and as a Pennsylvania Senator from 1976 until his untimely death in 1991. (Photo: Mattes, Wikimedia Commons)

PERERA: The chemicals that we and others in finding an children's bodies come from many different products that are used in everyday life - consumer products, components of buildings, furniture, cosmetics and found in our food. Many of them get into our food and these exposures are largely involuntary, that is, individuals don't have control over them.

CURWOOD: Now Dr. Perera, you've testified in Congress urging revisions in the Toxic Substances Control Act. That hasn't happened so far. What else have we learned in recent times that suggest perhaps now is the time that that law should be changed to reflect your research and others’ research?

PERERA: There are now 80,000 chemicals in use and only 7% according to EPA had a complete set of toxicity screening data. That's a big problem that chemicals have been manufactured and released into the environment and are now capable of reaching our bodies and the bodies of our developing fetuses and young children. We do we need a change in that regulatory structure to require pre-manufacture testing to look at the chemicals and exposures that are most harmful. It's a question of shifting the burden from individuals or researchers or even EPA to show that there's a problem with chemicals to the manufacturers to show that they are actually safe. The good news is that once we identify as harmful environmental exposures they by their very nature are preventable, and the potential benefits are huge. The costs of a childhood illness due to environmental contaminants in 2008 were estimated at $76 billion.

CURWOOD: Dr. Perera, this is all pretty depressing stuff what these chemicals can do. What makes you optimistic?

Dr. Frederica Perera is a professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University and founding director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health. (Photo: Kelly Campbell)

PERERA: Well, I'm optimistic that robust science can help drive preventive policies. The research from our center has been credited with prompting changes at the local level to reduce emissions from traffic and also residential heating, and to eliminate toxic pesticides in city housing. We also were able to show that there are some economic benefits when we reduce pollution that can play out over the lifetimes of the children and also possibly into future generations.

CURWOOD: Dr. Frederica Perera is Professor of Environmental Health Sciences and Founding Director of the Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health, and winner of the Heinz Environmental Prize this year. Congratulations and thank you so much for taking the time.

PERERA: Thank you very much, Steve. I enjoyed it.

Related links:

- Announcing the 20th Heinz Awards Honorees

- About Dr. Frederica Perera

- Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health (CCCEH)

- About Senator John Heinz

- The Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA)

Driving Down Diesel School Bus Emissions

New legislation will require that school buses shutdown their engines after 5 minutes of idling. Some newer buses automatically turn off after a few minutes of idling. (Photo: Julie Grant)

CURWOOD: Back in 2007 new federal rules went into effect that sharply reduced sulfur in diesel fuel, which is mostly used in trucks and buses, and new diesel vehicles have to run much cleaner. The goal is to achieve a 90 percent reduction in particulate pollution, which is hazardous to health, with the elderly and children most at risk. But many older school buses don’t have the new pollution control systems, and new ones are expensive.

So at the urging of the EPA many states, including Pennsylvania now limit the idling of school buses, especially where kids line up. Julie Grant from the public radio program the Allegheny Front has our report from Pittsburgh.

[STREET SOUNDS]

GRANT: It’s fifteen minutes before school lets out for the day, and buses are lined up on the street by a Pittsburgh school building. Some of them are idling: sitting there running the engine.

[BUSES IDLING]

GRANT: It’s a sunny, cool day.

FILIPPINI: That’s true; it’s probably in the 40s or so.

GRANT: Rachel Filippini is with GASP. The Group Against Smog and Pollution. She says even if were below freezing, state law says buses aren’t allowed to idle.

FILIPPINI: Regardless of the temperature, the law says you have to turn off your engine within five minutes.

GRANT: Filippini says GASP has been monitoring buses in the Pittsburgh School District, to see if they’re following the state’s no idling law. They’re worried about kids’ health - on board the bus, and sitting in nearby classrooms, where diesel fumes can waft in. Filippini says particles in diesel fumes are so tiny; they can make their way deep into the lungs and the blood.

FILIPPINI: They’re kind of sticky, and irregularly shaped, and they have sometimes other toxics or heavy metals that are stuck on to them. And those things which you do not want to be inhaling, are getting a free ride into your body, where they can cause a lot of problems.”

GRANT: The federal government says diesel exhaust is a likely cause of lung cancer, as well as asthma attacks, chronic bronchitis, and heart disease.

[BUS OFFICE]

GRANT: Sue Roenig thinks buses are cleaner than they used to be.

ROENIG: Actually, I think, being around school buses my entire life, I can tell the difference just walking outside here.

GRANT: Roenig’s family owns a bus company that contracts with Pittsburgh and other school districts in the region. At their garage in rural Sarver, a half hour north of Pittsburgh, the country air can fill up with exhaust fumes.

ROENIG: Like in the morning, when the buses out are lined up, ready to go to pick up students, my eyes don’t water anymore when I walk through the parking lot. So that has to be something. I think there is a big difference actually.

GRANT: Beginning in 2007, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency started limiting the pollution – the particulate matter, and oxides of nitrogen, from heavy-duty diesel vehicles. Companies that run school buses must either retrofit their exhaust systems, or when they purchase new buses, buy vehicles with pollution controls built in.

The Heinz Endowments offered a half million dollars in 2007 to area bus companies to retrofit them with the new filters. But Roenig’s was one of the only companies to take them up on the offer.

ROENIG: I think it was probably just a matter of a lot of people at the time holding back just to wait to see how it actually worked out. Because sometimes you do things, and it sounds really good on paper, but it doesn’t turn out that way.

[MECHANIC SHOP SOUNDS]

ROSS: I thought it was going to be a disaster.

GRANT: That’s Roenig’s mechanic Bill Ross.

ROSS: But this really worked good. It really did.

GRANT: The Allegheny County Health Department says they don’t know of a central database tracking how many school buses have the cleaner technology, but estimates that around three-fourths should have lower emissions since the law went into effect.

Sue Roenig says some of the new buses they’ve purchased won’t let drivers idle - not even to warm up on a winter morning.

ROENIG: They just shut off. Every ten minutes you have to go restart them trying to get the motors warmed up. Makes for a long morning sometimes.

GRANT: Research shows when everyone in an area uses cleaner vehicles, it can make a real difference in air quality. Albert Presto studies air pollution at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

PRESTO: When these technologies are working well, they can reduce over 90 percent of the particulate matter emissions from diesel vehicles.

GRANT: That’s right, he said 90-percent cleaner. Presto gives the example of Oakland, California,

PRESTO: Which is an enormous seaport.

GRANT: California forced old trucks running from the port to storage facilities to reduce their emissions - quickly. And Presto says it worked. They significantly reduced diesel pollution.

PRESTO: And that helped improve air quality at the Port, and in the neighborhoods near the Port.

GRANT: Pennsylvania is moving toward the same diesel control standards as California. But so far, Presto says it’s been difficult to parse out the impact of cleaner school buses in a city like Pittsburgh. There are so many older diesel buses and trucks still on the road without pollution controls.

[BUSES AT PITTSBURGH SCHOOL]

GRANT: Back at that Pittsburgh school, clean air advocate Rachel Filippini says construction sites and even riverboats can cause more diesel pollution than school buses. But buses have such a direct impact on children, especially when they idle.

Filippini’s group GASP has given schools signs that say “No Idling” to post at pickup zones. The day we were there, some drivers idled anyway, but many did shut down their engines.

FILIPPINI: This is a vast improvement from what I saw last fall.

GRANT: Filippini says when they monitored buses that time, more than a quarter of the buses surveyed were idling, and that’s too many. The Department of Environmental Protection says they’ve gone after some drivers too long, but Filippini says better enforcement could go a long way to keeping the air cleaner for kids. I’m Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie reports for the public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- More about idling buses, air pollution and health impacts on the Allegheny Front

- State of the Air 2015: Most Polluted Cities

- GASP, the Group Against Smog and Pollution

- IdleFreePA: problems with idling and PA laws against it

- GASP’s campaign to clean up school bus emissions

- The EPA’s National Clean Diesel Campaign (NCDC)

Beyond the Headlines

Bank of America plans to pull investments in the coal industry. (Photo: Mike Mozard; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: OK. We’ll head off to Conyers, Georgia, now to see what Peter Dykstra has dug up in the world beyond the headlines. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org and he’s on the line. Hey there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Let’s start with another blow in the so-called “War on Coal,” this time, from those tree-hugging, capitalism-hating folks at the Bank of America.

CURWOOD: Well I had no idea that bank-hated capitalism so much. Or maybe there’s a touch of sarcasm in there.

DYKSTRA: Yes, just a touch. At its annual meeting, the Bank of America announced that it’s pulling back from many key investments in the coal industry, saying they’re “reducing our credit exposure to the coal mining sector globally.”

CURWOOD: So can the fossil fuel divestment movement take any credit for this?

DYKSTRA: Yes they can. The bank acknowledged several years’ worth of pressure from activist groups but said they’ll continue to promote what they call “the responsible use of coal.” But make no mistake, this is a bank, a very big bank, and it’s about money first and foremost. Which brings us to another Living On Earth stock report.

CURWOOD: Yes, stock reports, precisely why people tune in to Living on Earth.

DYKSTRA: Right but here’s an update on the continued collapse of coal stocks. It’s gotten much worse since we talked about this several months ago. In 2011, Arch Coal, one of America’s biggest producers, peaked at about $38 a share. It’s now just below one dollar, officially a penny stock. Another coal giant, Alpha Natural Resources, has gone from about $75 to about 78 cents in that same time frame. Both companies have been warned by the New York Stock Exchange that they could be de-listed. The Bank of America may hear climate activists talking, but that’s some money talk that’s too loud to ignore. And one more – Patriot Coal, a big player in the eastern US, filed for bankruptcy for the second time this past week.

CURWOOD: So a lot of folks in the coal industry who have never accepted the science on climate change are up against...what - the Big Bank Theory?

Shell attempted to drill in the Arctic a few years ago, but failed to meet environmental and safety standards. Despite this history, the Obama Administration approved Shell’s fossil fuel exploration plans in the region. (Photo: Day Donaldson; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Nice one. Let’s move on to another item from the fossil fuel world. Having obtained a crucial approval from the Obama Administration, Shell says it’s headed back to the Arctic for offshore oil exploration. They’re doing so despite a whole host of apparent reasons why maybe they shouldn’t.

CURWOOD: The most obvious one being fossil fuels and climate change, but that’s never stopped oil exploration before.

DYKSTRA: Sure, but also, Shell’s abortive first attempt in 2012 was a comedy of errors and Coast Guard safety violations. In addition, the US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management said six months ago that Arctic drilling carried a 75% chance of at least one significant spill, and dealing with an oil spill in the cold, stormy, and for the moment ice-choked Arctic would be a daunting task. But then there’s the 1,000-pound polar bear in the room.

CURWOOD: What’s that?

DYKSTRA: Extracting oil from the Arctic is almost prohibitively expensive, and despite some recent jumps in oil prices, petroleum products are still going cheap. We’re way under $100 a barrel for the foreseeable future. The USGS among others have estimated that oil prices would have to be anywhere from $100 to $300 a barrel to give Arctic oil drilling even a slim chance of being profitable, let alone safe.

CURWOOD: So unless Shell knows something we don’t, the numbers don’t add up. Hey, what’s the stop on the history train this week?

Thanks to much of the research done at Hubbard Brooks Experimental Forest, we now know more about the effects of acid rain. Acid rain erodes many stone structures, particularly limestone. (Photo: Nino Barbieri; CC BY 2.5)

DYKSTRA: Let’s pay tribute to thinking ahead, and the value of smart science. Sixty years ago this week, the US Forest Service established the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire—three thousand acres of protected forests where geeks can play with trees. Hubbard Brook has provided invaluable information about forest ecosystems and protecting streams, and it’s been one of the most important research sites in the world for learning about acid rain.

CURWOOD: Of course we’ve covered the problems and progress on the acid rain issue over the years.

DYKSTRA: And in addition to Hubbard Brook, whose work continues, we should mention Canada’s Experimental Lakes Area in Ontario, another pioneer in acid rain science, which the Canadian Federal government put on the chopping block two years ago, but a mix of private and provincial money came to the rescue and is keeping this landmark facility alive.

CURWOOD: And moving science forward. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and the DailyClimate.org. Hey Peter thanks for taking the time today.

DYKSTRA: All right Steve, thanks a lot, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And if you want to hear more or see more on these stories visit our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Bank of America's to limit credit exposure to coal

- Arch Coal Stock

- Alpha Natural Resources Inc. Stock

- Arctic Drilling is likely to lead to a large oil spill

- Estimates of oil drilling in the arctic are costly

- More about Hubbard Brook Ecosystem Study and acid rain research

- Our coverage of acid rain and the Clean Air Act

- Canada's Experimental Lakes Area saved

[MUSIC: Pavel Egorov, Schumann Forest Scenes Op. 82 - Farewell To The Forest 1994 Australian Broadcasting Corp]

CURWOOD: Coming up...they’re cute, they have brightly colored bills, and now they’re back. Puffins are just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Andres Segovia, Fantasy; Segovia: The Great Master 2004 Deutsche

Grammophon]

The Puffin Project

Puffins gathering on a rock (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Environmental success stories are favorites here at Living on Earth. So we were excited to read a new book called "Project Puffin: The Improbable Quest to Bring a Beloved Seabird Back to Egg Rock". One of the book's co-authors and photographer is Boston Globe editor and columnist Derek Jackson.

JACKSON: It’s pretty funny for me because I started off as a sports writer, and so once upon a time the only birds I knew about were the Atlanta Hawks, the Philadelphia Eagles, St. Louis Cardinals and Baltimore Orioles. But because my wife's an outdoor person I got into the outdoors and I heard about these puffins, and at that time the success of it was only five years old so it was still pretty exciting to be at a place where life that had been lost had been restored.

A puffin inspecting one of the decoys set up by Kress’ team (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

CURWOOD: That restoration was the work of the book's other co-author, Steve Kress. Steve is the vice president of the National Audubon Society, and since his early 20s he has been working to restore the historic puffin population to Egg Rock off the coast of Northern Maine. Steve says his devotion to the puffin was rooted in a childhood spent close to the birds and bees.

KRESS: As a kid I was fortunate in meeting ornithologists and other birders and they shared their passion and enthusiasm with me and I caught the bug of just enjoying being out in nature. It started with non-birds. It started with lizards actually. The blue-tailed skink was my greatest of prizes as a child, but any frog or turtle, or reptile; anything that I could actually get my hands on was terrifically interesting. So yeah, that's how it all started. And then it just sort of stuck from there. I just kept meeting more people and realizing there was a relatively small world of birders out there and there's so much interconnection and all pathways sort of pointed me toward Hog Island which is sort of where ornithology had its beginning in the northeastern United States.

Flying with fish (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

CURWOOD: How's that?

KRESS: Well there’s this beautiful island, a 330-acre pristine island, spruce covered island, offshore near Damariscotta, Maine, where Roger Tory Peterson, the sort of undisputed father of birding in United States was the first bird instructor. Alan Cruickshank another famed early American birder and others have followed and they just sort of started a tradition of people coming there and learning about birds. I started working at the Audubon camp in 1969 and learned that puffins once bred about eight miles from where I was working on Hog Island, and once I've discovered those islands were once home to puffins, I couldn't see them the same as I used to. I saw them as places that were devoid of life rather than full of life. It was a strange twist of perspective, but once I realized that they were a diminished place I began setting out to try to bring them back. I didn't know that I would be at this for decades. When I started this I thought, oh, this will take a few years and I'll be on to something else, but I guess hasn't worked out that way.

Puffin flying with fish (photo: Derrick Jackson)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I guess not. So what did you think you could restore these Puffins to the places that they had been hunted off almost a century before?

KRESS: The idea of bringing the puffins back probably was influenced by other bird conservation projects at the time, notably the Peregrine Fund was starting its work at Cornell trying to reestablish the Peregrine falcon, a bird that had disappeared because of the use of DDT. It was still a novel idea and many people at the time felt that it was better just to let nature to take its course, and the species that would best adapt to living with humanity would be the ones that would be the future co-inhabitants of the planet and if we lose some on the way they were the ones that just didn't fit anymore.

CURWOOD: And I suppose this philosophy struck you with – let’s see, who cohabitates with people best - roaches, rats - things that we don't particularly like.

Taking flight as one (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

KRESS: So, I've come to realize that the species that benefit the most from people tended be scavengers and, yes, the species that seemed to do the best of them are often considered nuisance species by people. In the bird word that would include lots of native birds, not just introduced species but natives like gulls, herring, and blackback gulls would be the most obvious example of that along the Maine coast, scavenging behind fishing boats and in garbage dumps. So if that was the pattern then we were going to lose birds like the puffins and there was nobody out there really trying to help these specialized species especially if they were not an endangered species. Endangered birds had a certain cachet just in their rareness, but common species, not necessarily. Especially species that were still nesting in the millions, and the puffin was among those. You could find millions of them if you would just travel to Iceland and some would say to me: “why should you bother to restore a common species when if people want to see them, they should just go to Iceland”. I felt that we had lost them on the Maine coast; perhaps it was the proper thing to do to bring them back.

CURWOOD: Now, you got to say if you look at a puffin, it's hard not to - come on – laugh! They're roly-poly, they have this brightly colored beak, they stand up directly - they almost look like a penguin - and they're charming, right?

Puffin with bands on its legs (photo: Derrick Jackson)

KRESS: Puffins are a charming bird. They kind of are caricatures of the human form. They're upright. They stroll. They waddle back and forth and they have this comical face, clown-like face, so yeah, they are sort of built-in endearing. Of course it's all functional from their point of view. They're feet are all way back because they're used as rudders underwater and they have those short wings they hold to their sides because they use them as flippers underwater. It's all about function. But it also happens to characterize a human clown like form which people love.

CURWOOD: And you in particular really, they sucked you right in, of all birds you could've chosen to devote your life to - although I gather you didn't know it was going to turn out to be a lifelong exercise - I mean, are there any that are cuter than this?

KRESS: I don't think there's any that are cuter than a puffin. [LAUGH]

CURWOOD: So you decided at age 20 that you are going to figure out a way to save these birds to bring them back to this place where they had been. How did you just start?

KRESS: I started the idea of bringing puffins back by learning as much as I could about them. A few things I learned was that was that puffins just lay one egg. They don't usually lay it until they're several years old and then interestingly enough at the end of the breeding cycle which is about six weeks long the chicks head off to sea by themselves not with parents which is very helpful to me in my plan because there's no way I was going to follow these chicks to sea. But the key part of the story was that they learned were home was while they were at the island. My hope was that I could find puffin chicks that were impressionable and that I could move them before they learn where they were hatching, hand-rear them, release them and give them the two to learn about the release site, the new home. That method is called translocation now and it's widely used, but at the time it was never used before for a seabird.

CURWOOD: So where can you get extra spare baby puffins?

Feisty puffin chick in hand (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

KRESS: Fortunately there are still large colonies of puffins in Canada and I had to travel all the way to Great Island Newfoundland. And with the cooperation of the Canadian Wildlife Service, and with their help out, we climbed down the cliffs of the Great Island where at the time about 160,000 pairs of puffins. It was an awesome site. We moved as many as 200 of them at a time.

CURWOOD: And how do you move a baby puffin?

KRESS: You pick it up, take it out of its burrow, put in a specially built carrying case and as fast as you can you bring it back to Maine.

CURWOOD: I would imagine ma and pa puffin weren't too thrilled about this.

KRESS: When you reach into a puffin burrow you have to be careful because if the parent puffins are in there, that big colorful cuddly looking beak is actually quite a crusher and if they grab ahold of your finger and start twisting and shaking with their raptor like hook which they have it can be damaging. But we did it and we reached into enough puffin burrows and we obtained enough puffins to bring them back. We tried not to revisit the same puffin burrow in more than one year; so that we didn't have the same ongoing disturbances same parent puffins. And most of the chicks survived we brought from Newfoundland. They are very hardy little birds. They trucked off to sea with our bands and disappeared in the darkness.

CURWOOD: You brought hundreds of birds from Canada to Egg Rock Island where you hoped to get a new puffin colony but, how would you know you had succeeded?

KRESS: The only way we would know whether we were having success was see the puffins come back and we put leg bands on them before they fledged, that's before they left the island, so we would recognize them in the future. A metal band on one leg and usually a color band, a plastic band on the other leg, and then we just had to sit out there and wait. And the thing is that we had to wait four years without seeing anything at all. Four years into the project, we had released several hundred puffins and none of them had come back. I was starting to get questions from the supporters; the providers of the puffins, and the Canadian Wildlife Service were wondering what is going on. When are you going to have some success? I asked for patience - no one's ever done this before - we have to see this out because if we fail at this other people in the future probably won't want to try something similar. And there's a great need. Even then I knew there were many rare seabirds would benefit from this project if we could prove success.

Steve Kress and students in Maine (Photo: courtesy of Stephen W. Kress)

CURWOOD: So big goose egg so far – or maybe big puffin egg so far. But no birds back so this is the point that you're about to give up but by the title of your book obviously you didn't. What happened?

KRESS: In four years we needed to have some success. I began trying to think like a puffin and I realized that one of the things that were missing was the fact that there were no other puffins on the island. Puffins are social birds. They nest in colonies. And a young puffin coming back even if it did remember Egg Rock might not come ashore without the sight of other puffins, so I came up with the idea of using decoys. So we got some decoys specially made, specially carved, not something you can buy off the shelf any place, put some in the water, put some on land and we didn't have to wait very long before one showed up. Within days there was a puffin that landed on the island, and then it landed with the decoys on land, and it had our leg bands. I was so excited.

CURWOOD: So puffins like a party huh?

KRESS: Puffins don't like to be alone. They like other puffins. Now puffins do land with decoys we discovered and they'll pick at the beak and they'll pick at the belly and eventually they will get bored. They'll leave. Because they're not getting much response and they're not really fooled by the decoy for long, but I decide to put out mirrors, boxes with mirrors on all sides, and the puffins would land with the decoys then they would waddle to see the reflection in the mirror and they would just sit there and look at themselves and they move a little bit, the reflection would move. I don't think they really were totally fooled by this to think it's another puffin but what did happen was that other puffins would land with the puffins that were sitting among the decoys and the mirrors and eventually we start seeing more and more puffins sitting on the island.

Checking out one of the decoy puffins (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

CURWOOD: So you've created a puffin party by having models. That always helps a party scene. You have a mirror ball that helps the party scene. But what about the sound?

KRESS: We didn't use sound for puffins, recorded sound. Later when I started attracting terns I started using recorded sounds for terns and that has proved to be very attractive from the terns. With puffins I was trying to keep it simple and with puffins they're not that loud. They don't call a lot, especially at that stage in their lifetime. Later in life they have a deep growling call. It sounds sort of like this. [NOISE] That's a call between a mated pair but the prospecting birds, these young birds, they don't call much, so we want to try to keep it as simple as we could. And the mirrors, the decoys, they started coming back, but they still weren't breeding. We were eight years into this project, still no nesting.

CURWOOD: So what do you do then? If these birds are propagating themselves you're going to be bringing chicks from Canada forever.

KRESS: And even a greater concern was that some of our birds brought from Canada started nesting at a nearby puffin colony Matinicus Rock.

CURWOOD: Traitors.

KRESS: I was worried that they would move over there after all my efforts—so close but so far. Eight years into the project, the critics were really becoming increasingly vocal at that point, that this had not worked, stop spending money on it, stop saying that it's working. We still needed birds breeding and that's why in 1981 on the fourth of July when we saw the first puffin flying in with fish, that's the clue we were looking for, and finally we had success at Egg Rock.

Coming in for a landing (Photo: Derrick Jackson)

CURWOOD: Flying in with fish to...

KRESS: Feed its chick. Fly in with fish and drop under the rocks and they come out without the fish, and that's the sign we're looking for. That meant there was a puffin chick under the rocks, the first puffin chick in nearly 100 years.

CURWOOD: Steve, a number of people have emulated the techniques you developed on the puffin project, there are a number of bird restoration projects around the world, and in your own book, you can wrestle with the question of sustainability. You say that people ask you how sustainable is this, and your answer is that's maybe not the right question. So what is the right question and what's the right answer?

Derrick Jackson and a guillemot chick (photo courtesy of Stephen W. Kress)

KRESS: Project Puffin is showing that if you just don't do this kind of work these species are not going to come back. To stop this kind of work they probably still will disappear, but they are still capable of living in this environment with a helping hand. When I was a young man, one of my mentors, Duryea Morton pointed out to me that people are the only species that can make other animals go extinct. People therefore have an opportunity, perhaps even an obligation, to be the only species that can help sustain life on Earth, because if we stop, these species that have been affected by humans will disappear. We live in a time of extinction, and without active intervention we can be sure that we will lose species, and if we do future generations will not have the opportunity to do the restoration that we have today.

CURWOOD: Steve Kress and Derek Jackson are co-authors of the book: "Project Puffin: The Improbable Quest to Bring a Beloved Seabird Back to Egg Rock". Steve, thanks for taking the time today.

KRESS: My pleasure.

Related links:

- Puffin Project: The Improbable Quest to Bring a Beloved Seabird Back to Egg Rock

- Derrick Jackson is a columnist for the Boston Globe

- Project Puffin

- More about Steve Kress

[MUSIC: David Carbonara Elevator Gossip Mad Men - After Hours 2010 Umg

Recordings]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth...change is inevitable – and Lester Brown says a total transformation is coming to the way we power our civilization.

BROWN: The exciting thing about this is how fast it’s going to happen. I think we're going to see a half-century of change compressed into the next decade.

CURWOOD: The Great Transition to a renewable energy economy. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and John Jessoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more; www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth