November 20, 2015

Air Date: November 20, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

New Toxic Substances Control Act Likely

View the page for this story

The Toxic Substances Control Act was passed in the 1970s, but since then has proved mostly ineffective at regulating toxic chemicals. A bill updating TSCA is moving through Congress now, and Andy Igrejas of Safer Chemicals Healthy Families tells host Steve Curwood that while the bills are weak, it’s a start. (07:05)

Prenatal Chemical Exposure Linked to Obesity

View the page for this story

Inadvertent chemical exposures from dumping can provide epidemiologists with unique insights into the possible effects products can have on human health. Brown University professor Joseph Braun tells host Steve Curwood about a group of pregnant women in Cincinnati with high blood levels of the industrial chemical, PFOA, whose children were fatter, possibly giving them an increased risk of health problems later. (05:40)

Health Risks of Water Fluoridation Raise Concerns

View the page for this story

Two-thirds of Americans have tap water with added fluoride, thought to help prevent tooth decay, but research has raised questions about the additive’s safety. Host Steve Curwood examines the science around fluoride’s health effects and hears from eco-activist Laura Turner Seydel about potential, under-reported risks and measures the public can take for protection. (08:10)

Let's Talk Turkey

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Almost all of the turkeys eaten in the United States are the same species: the Broad-Breasted White, but as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports, heritage breeds of turkeys, like the Bourbon Red and Blue Slate, are making a comeback. (04:50)

Cranberries Take Centerstage

/ Emily TaylorView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Emily Taylor brings us an audio postcard of an old Thanksgiving standby: the cranberry. (04:20)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about EPA’s enforcement of federal regulations in states, the claim of a conspiracy to brand red meat as a health hazard, early retirement of Exxon’s PR executive and how opening canals can allow more than just ships to pass between seas. (04:15)

Pawpaw: America's Forgotten Fruit

View the page for this story

The largest edible fruit native to the U.S. is unknown to most, yet the pawpaw has earned a loyal following among those who are familiar with it. A new book peers into the pawpaw’s storied past, how its popularity has grown today, and why it’s not a staple in the produce aisle. Writer Andrew Moore tells host Steve Curwood about his mission to find the human story in this forgotten fruit. (13:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Andy Igrejas, Joseph Braun, Laura Turner Seydel, Andrew Moore

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra, Emily Taylor

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: The Toxic Substances Control Act, or TSCA, is nearly 40 years old and from the very beginning it has protected the public poorly.

IGREJAS: The TSCA when it passed in 1976 it had a key flaw. For all the chemicals that were on the market at the time, it basically said these are presumed fine unless the EPA can prove that there’s a problem.

CURWOOD: New versions are working their way through Congress, but critics say they still fall short. Also, as Thanksgiving approaches, farmers are saying old-fashioned heritage turkeys are flying out of their coolers…

STILLMAN: Almost everybody who ordered a turkey from us last year has ordered two turkeys. So I don’t know if they’re thinking they’re going to pop one in the freezer and keep it for Christmas or something like that but people raved about the turkeys.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In a Beautiful Place Out in the Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

New Toxic Substances Control Act Likely

Mothers at a rally in support of TSCA reform (Photo: Senate Democrats CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. We begin our broadcast today with Tosca, but not the famous melodramatic opera by Puccini. No, this TSCA is the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 that lists some 85,000 chemicals in its inventory, though there is plenty of melodrama in the decade-long efforts to modernize it. In fact there was practically a deathbed scene when the long-term proponent of TSCA reform, New Jersey Democratic Senator Frank Lautenberg, cut a deal with Louisiana Republican David Vitter just days before Lautenberg’s death. But another longtime proponent, California Democrat Barbara Boxer, denounced that pact as a giveaway to industry, and turned against some provisions of current TSCA reform legislation now before the Senate. Andy Igrejas, director of Safer Chemicals Healthy Families predicts the bill will pass, but he thinks it’s too weak. Andy, welcome to Living on Earth.

IGREJAS: Thanks for having me!

CURWOOD: The Toxic Substances Control Act I believe was done back in 1976 and really hasn't been revised since then. Why has it been stuck for so long?

IGREJAS: Well, the Toxic Substances Control Act when it passed in 1976 it had a key flaw in it in that it basically said that the government was going to require an approval process for chemicals that were invented from that point forward, that industry wanted to bring to the market, but for all the chemicals that were on the market at the time, it basically said these are presumed fine, unless the EPA can prove that there's a problem. Pretty quickly it turned out that the legal hurdles and the administrative hurdles to the EPA being able to prove that there was a problem with those existing chemicals and that's still the bulk of chemicals, it was 62,000 at the time. The legal hurdles to EPA actually taking action on those chemicals proved insurmountable. They spent the 80s trying to regulate asbestos and when they finally got around to a full-fledged rule to restrict asbestos, the federal courts struck down the rule and EPA basically gave up at that point on trying to restrict those chemicals that were on the market at the time that TSCA passed. And the chemical industry enjoyed that protection and didn't want to change TSCA until relatively recently.

Without federal regulation, retailers have taken action to eliminate potentially harmful chemicals from commercial products, like BPA from cans. (Photo: Artizone, Flickr CC BY-2.0)

CURWOOD: And what's been the incentive now for industry to stop its opposition to this and be willing to move forward on additional regulations on toxic substances?

IGREJAS: There are three things that changed in the country and the world in the 2000s basically that brought the chemical industry to the table. The first is that state government started to fill the void and to review and restrict certain chemicals, and the pace of that state activity went from a couple of things here and a couple things there to more comprehensive laws getting passed in different states. Then there was a phenomenon that the industry calls retail regulation where you had Walmart, Target and some others responding to consumer demands about avoiding certain toxic chemicals and they started to just restrict them themselves. And the third major change is that Europe overhauled its chemical regulation in ways that started to set a new standard for the world and has set a new standard for the world and so you have a lot of our trading partners around the world really keying off of what Europe is doing with chemicals instead of what United States is doing. And all three of those things had the chemical industry say“well, wait a second, we'd rather have one stop shopping in Washington for how chemicals are getting reviewed than all of these changes out there in the world.”

CURWOOD: Andy, I think one of the core issues around the Toxic Substances Control Act is that there are just thousands of chemicals in our country today that are waiting on some kind of review by the Environmental Protection Agency. How well would this version of the law equip the government to do the review that's necessary? Someone told me that the math under the present system, it would take a millennium to actually review all these chemicals.

IGREJAS: The review is still, under either bill - the one that's passed the House or the one that's passed the Senate - the pace of reviews will be pretty glacial compared to the amount of chemicals that are in commerce. Basically, the house bill calls for EPA to review and potentially restrict at least 10 chemicals a year. The Senate bill has a schedule that is weaker than that, 25 chemicals over eight years. There's some differences...the Senate schedule is more enforceable, people outside could sort of sue EPA if it didn't make the schedule. The way the House one is structured you couldn't. But under either context we're talking about some fairly slow progress. One of the questions is can EPA only require testing for the chemicals that it is at the moment it's reviewing their safety, or can it require testing of a batch of chemicals to help decide whether these are chemicals that need to be reviewed, and at least shine more of a light on more chemicals than that just the ones that are under its lens at a given moment. And that's something that the bill's differ on a little bit too but at least EPA will be getting in on the act of reviewing chemicals, but we're talking about a pretty modest step when measured against the amount of unreviewed chemicals that are out there.

CURWOOD: Help me on the math of the unreviewed chemicals. How many thousand unreviewed?

IGREJAS: Officially the TSCA inventory is up at around 84,000.

Andy Igrejas is the Executive Director of Safer Chemicals Healthy Families. (Photo: Safer Chemicals Healthy Families)

CURWOOD: 84,000 chemicals, 10 chemicals a year.

IGREJAS: At best 10 chemicals a year.

CURWOOD: So that's 840 years. That's not quite 1,000 years.

IGREJAS: It's not quite 1,000 years. I think the math of it is ridiculous. One of the things is most people agree that's sort of the official tally of chemicals in commerce. Most people think that the number is probably half that or maybe less than that so I think it's a little less stark than those statistics make it sound. But it is still a problem. The earlier versions of reform that we've been pushing really called for grappling with that schedule in a more aggressive way dealing with batches of thousands, but the chemical industry and others kept blocking that effort so what we're looking at now is going to be a fairly limited set of reviews. They would still be meaningful compared to the status quo because if EPA reviewed chemicals that are a problem right now and really looked at all the uses of the chemical and either banned the chemical or restricted the uses to a few things where it's really necessary where people aren't being heard and they can demonstrate that, that would be progress, that would be potentially significant progress even doing that for 10 chemicals a year compared to the status quo, but measured against the problem it's certainly not enough progress.

CURWOOD: Andy Igrejas is Director of Safer Chemicals, Healthy Families. Thanks so much for taking time with me today, Andy.

IGREJAS: Thank you so much. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- TSCA Modernization Act of 2015

- 'Stalemate' over LWCF-TSCA push

- U.S. chemical regulation reform gets boost as House passes TSCA rewrite

- Andy Igrejas is the Executive Director of Safer Chemicals Healthy Families

Prenatal Chemical Exposure Linked to Obesity

Babies exposed to certain chemicals in the womb have a higher risk of weight and health related issues later in life. (Photo: Drpoulette from Mexico City, Mexico, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, many chemicals in common use have made things easier – from detergents and industrial lubricants to insecticides and flame retardants - but exposure to some of those same products might be working against our health. In particular, some common chemicals ingested during pregnancy seem capable of promoting obesity in offspring. It turns out that some children who were born in the Cincinnati area downstream from some industrial dumping in the Ohio River now have more fat if their mothers had roughly twice the level of a certain chemical in their blood during pregnancy. Dr. Joseph Braun, Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at Brown University is lead author of a study of these children in the Journal of Obesity. Dr. Braun, welcome to Living on Earth.

BRAUN: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So it's not ethical to test people by exposing them to possibly toxic chemicals, so in this case I gather that upriver, up the Ohio River, there was some sort of a chemical dump containing these chemicals?

BRAUN: Yes, so what had happened in the past is there was a DuPont plant up in Parkersburg, West Virginia, that had been manufacturing fluoro polymers. So these chemicals have a variety of uses. They include being used in industrial processes as a surfactant to make fluoro polymers and to make other chemicals. They are also used to repel stains or to repel water as a coating in stain and water resistant textiles. They're also used in some food packaging, places where you have both water and oil and you don't want that water oil to soak the paper that's been used as packaging, and they're also used in firefighting foams, and in the process of manufacturing these chemicals they used one specific chemical called perfluorooctanoic acid, and up until 2000 they were releasing this chemical into the environment.

CURWOOD: So in this case it's not necessarily how these women in Cincinnati were exposed to this chemical but a possibility.

BRAUN: Exactly. We suspected the vast majority of exposure to these chemicals comes from the diet. So we speculate that the elevated levels of this particular chemical perfluorooctanoic acid or PFOA could be related to the ingestion of contaminated drinking water. However, we were not able to show that in this study and this is something we're trying to look at in our future work.

CURWOOD: Now, you suspect these chemicals are in a class that you scientists have called obesogens. What are obesogens and how do they affect people?

BRAUN: So, obesogens are chemicals that upon exposure to them may increase the risk of obesity or other diseases related to obesity, like diabetes or cardiovascular disease. And obesogens may work by affecting hormonal systems that are involved in programming fetal growth or growth in the child. They may also affect the programming of our appetite or metabolism. Or they could affect how our genes are expressed.

CURWOOD: So what did you look for in your study exactly?

BRAUN: We measure the concentration of several perfluoroalkyl substances in the blood of these women, including perfluorooctanoic acid, which we often call PFOA. So what we did is we looked at the relationship between levels of these chemicals and women's blood during pregnancy and their children's adiposity at eight years of age.

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) is used to make non-stick coatings, like those used for frying pans, which help separate oil from water. (Photo: Jean-Pierre, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Adiposity, you mean physical fatness?

BRAUN: Yeah, we had things like body mass index, their waist circumference and then an estimate of their total body fat percent in our study.

CURWOOD: So, when you studied these pregnant women's exposure perfluorooctanoic acid, what did you find?

BRAUN: So, compared to children born to women in the lowest third of exposure to this chemical PFOA, we found that the children born to women with higher concentrations of PFOA in their blood had .9 to 2.4 pounds more body fat at eight years of age. We worry about this for a couple of reasons. One is that any amount of increase in body fat is bad because it's very difficult to lose fat once you gain it. We can get children to lose weight but it's difficult to get them to sustain that weight loss, and the decreases in weight aren't as big as we'd like. In addition, increases in body fat, any increase even these small amounts can be associated with later life risk of disease like some cancers, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

CURWOOD: How prevalent this PFOA among Americans these days?

BRAUN: So, levels of these chemicals have been going down over the last few years because they're being phased out of commerce voluntarily by the manufacturers that use and make them, however, they are still detectable in over 90 percent of people in this country, and we're concerned though as well because these are persistent chemicals that have long half-lives in the environment and they have a long half-life in our body. They can stick around in our body for over three years at a time and so this is the concern.

CURWOOD: So we have this obesity epidemic in America. Two-thirds of us are overweight, fully a third are obese. What relationship if any do you think this is to the widespread exposure to PFOA chemicals?

BRAUN: We don't know for certain that PFOA or this class of perfluoroalkyl substances is responsible for the obesity epidemic, nor do we know if the broader class of chemical obesogens is responsible for the epidemic. However, we do know that some chemical exposures, some of which we suspect are obesogens, could increase an individual's risk for obesity or increase their body fat. So we have only I think begun unpackaging these associations between obesity and genetics, environment and other factors that we think contribute to obesity like diet or lack of exercise.

CURWOOD: Joseph Braun is Assistant Professor of Epidemiology at Brown University. His paper is published in the "Journal of Obesity. Thank you so much for taking the time today, Dr. Brown.

BRAUN: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- PFOA exposure in utero linked to child adiposity and faster BMI gain

- Braun et. al study: Prenatal perfluoroalkyl substance exposure and child adiposity at 8 years of age: The HOME study

- About PFOA

- CDC: Childhood overweight and obesity

- More about Prof. Joseph M. Braun

[MUSIC: Andre Kostelanetz and his orchestra and the Columbia Symphony “E lucevan le stele” from Tosca, Act III Giacomo Puccini Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...science is seeing more dangers in the widespread use of fluoride in drinking water to prevent tooth decay. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bill Frisell/Greg Leisz/ Jenny Scheinman Remember The Intercontinentals Nonesuch]

Health Risks of Water Fluoridation Raise Concerns

About two-thirds of Americans have fluoridated tap water. (Photo: jenny downing, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. For years anyone who questioned the safety of adding fluoride to the public water supply was seen as fringe and anti-science. Since shortly after World War II, fluoride has been added to water here in the US to help strengthen children’s teeth, and today it comes out of the taps in about two thirds of America’s households. But recently water fluoridation has come under closer scrutiny from science, and about 97 percent of tap water in Europe is now fluoride-free. Activists say it is time the US took similar steps. Topical fluoride in the form of toothpastes and rinses seems to be effective in combatting tooth decay, but studies now indicate swallowing fluoride with every drink of water could interfere with neurological development and thyroid function. Dr. Steven Peckham of the University of Kent published a paper on the association between fluoridated water and underactive thyroid, or hypothyroidism, earlier this year.

PECKHAM: We looked at the levels of hypothyroidism in general practice populations across England, and found an association or a risk, of higher levels of hypothyroidism in practices in fluoridated areas.

Stephen Peckham led a study on the association between water fluoridation and hypothyroidism in the U.K. that was published earlier this year. (Photo: University of Kent)

CURWOOD: And in 2014, we spoke with Dr. Philippe Grandjean, a Professor at the Harvard School of Public Health, about his research that found a correlation between fluoride exposure and lower IQ.

GRANDJEAN: We looked at more than 20 studies from China where they had compared children exposed to high fluoride content in the water and low. And on the average, the difference in performance among those kids was seven IQ points. That’s a sizable difference. And obviously some of the kids have been exposed to substantial fluoride concentrations in water, some of them were just a little bit above what’s common in this country and, therefore, I find that evidence very worrisome, and we need to follow up and determine if there is any risk in regard to fluoride exposure under US conditions.

CURWOOD: The US Centers for Disease Control maintains that water fluoridation helps to prevent cavities. But the Cochrane Collaboration, a global network of doctors and researchers who analyze science to improve public health, suggests the evidence is not so clear. The group found earlier this year that only three studies since 1975 have established credible links between fluoridated water and cavity prevention. Again, Dr. Peckham.

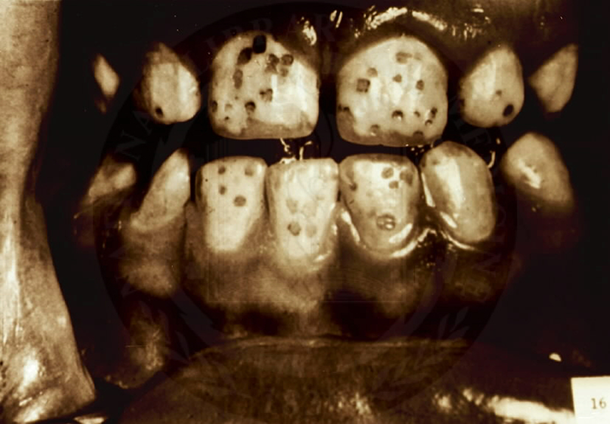

Dental fluorosis is pitting and discoloration of tooth enamel, and can be caused by drinking fluoridated water. In the U.S., dental fluorosis affects about 40% of children age 12-15. (Photo: National Institutes of Health, public domain)

PECKHAM: Their main conclusions were that there was no evidence to suggest that it reduced inequalities in dental health, that there was no evidence to support that it had a positive effect on adult teeth, and that there was no evidence to suggest that if you stopped water fluoridation, levels of decay would increase.

CURWOOD: The Cochrane group draws the line at 1975 because that’s about the time when products like fluoride toothpaste, rinses, and treatments in the dentist’s office became widely available. The group found strong evidence that fluoride can prevent tooth decay when applied topically. Fluoride that isn’t swallowed doesn’t carry the potential health risks to IQ and the thyroid that Drs. Grandjean and Peckham say are a concern. Dr. Peckham says we just don’t know enough when it comes to fluoridated water.

Philippe Grandjean’s observational study on the developmental neurotoxicity of fluoridated drinking water was published in Environmental Health Perspectives last year. (Photo: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health)

PECKHAM: It’s surprising that there hasn’t been a lot of really good-quality research looking at the effects of water fluoridation, and if you were to put water fluoridation up now as an intervention which was to be started, I suspect that on both scientific and ethical grounds, it would not be introduced.

CURWOOD: The lack of scientific research has caught the attention of activists including Laura Turner Seydel, co-founder of the Atlanta-based Mothers and Others for Clean Air. Ms. Seydel is urging the CDC to stop endorsing water fluoridation and in the meantime says consumers should protect themselves from unwanted fluoride. And it’s personal; Laura Turner Seydel told me she believes she has experienced the effects of fluoride in the public water supply.

SEYDEL: It’s something that I became concerned about seven or eight years ago. I have a problem with my thyroid, and the doctor that I went to suggested that it could have come from over-fluoridation, that I’d just had too much, and that it compromised the function of my thyroid. So I started delving into it deeper.

CURWOOD: What exactly does fluoride do to our hormone system? To our endocrine system to affect the thyroid do you think?

SEYDEL: Well, first of all, in the 40s and 50s, fluoride was used as medication for people who had hyperthyroidism, which means that your thyroid produces too much of a good thing, and so it would push you more into the normal range. So if people in this country are exposed to this much fluoride in our drinking water, in the food that we eat, the drinks that we drink, the soups that we consume, we're getting too much of a good thing and it pushes you over into the hypothyroid category, which means that your thyroid is not producing enough of the hormones that your body needs. And it weakens your immune system, it causes your metabolism to slow down, weight gain, things like that.

Sodium fluoride, shown here in tablet form, is one form in which fluoride is added to water to try to prevent cavities. (Photo: Mysid, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: What are some of the other likely effects of fluoride in the body?

SEYDEL: Well, what we found out from some of the research is that one out in three African-Americans have a condition called dental fluorosis, and that is the pitting and discoloring of the hardest surface and your body, your enamel. So either white spots or yellow spots or brown spots, and I think we need to be telling communities of low income and communities of color that there is fluoride in their drinking water and we should assist them by making sure that they have healthy alternatives.

CURWOOD: So what are some of the alternatives for consumers then who want to use fluoride to strengthen teeth enamel?

SEYDEL: Well, I'm not calling into question topical treatment and good oral hygiene that would include fluoride. I think that parents need to watch their children very closely because a lot of those toothpastes taste like candy, they're bubblegum flavor, they are strawberry flavor...they taste really yummy to a young child and children should not have more than a tiny amount, and a parent should be there to make sure that they spit it all out.

Laura Turner Seydel is an environmental advocate working to bring about a healthy and sustainable future. (Photo: courtesy of Laura Turner Seydel)

CURWOOD: So the bottom line is if one can afford it right now better to have either well water from a place that's not in the municipal system getting fluoridated or to go for bottled water, as expensive as it is.

SEYDEL: Well, I would say so. It's something that I definitely don't want in my drinking water, but I have reverse osmosis in my house so we can take the fluoride and other toxics out of our water. You know, if you can afford to have a system in your house, I would say do that or you can buy distilled water at the grocery store, but the best thing to do is to call the people in charge of the municipal water supply and let them know that you're not happy about it. Contact your elected officials. Contact the mayor of your city. There are about 99 cities around the country that have banned water fluoridation and you can see which ones those are on the Fluoride Action Network website.

CURWOOD: Eco-living expert Laura Turner Seydel is Co-founder of Mothers and Others for Clean Air. Thanks so much, Laura, for taking the time with us.

SEYDEL: Well, thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: And for more information about organizations that are looking into fluoride, please go to our website at LOE.org.

Related links:

- Study: Fluoride levels in drinking water and hypothyroidism prevalence in England

- Study: Developmental Fluoride Neurotoxicity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- “Facts About Fluoridation” from LiveScience

- Fluoride Action Network

- Newsweek: Fluoridation May Not Prevent Cavities, Scientific Review Shows

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on water fluoridation

- Our previous conversation with Dr. Philippe Grandjean

Let's Talk Turkey

A Bourbon Red tom turkey struts his stuff. (Photo: Yumiko Yumiko, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

[MUSIC: Joe Pipik “Turkey Blues” from ‘Give Up the Gobble’ (Self released—1983)]

CURWOOD: Yes, at Thanksgiving, the turkey reluctantly takes pride of place on dinner tables across America. Today 99 percent of the turkeys Americans eat over the holidays are the same species—the broad-breasted white. But as people increasingly choose organic and locally grown food, interest in old-fashioned breeds of livestock, including turkeys, is rising.

Ancient varieties of turkeys are enjoying a come-back—as Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb discovered down on a farm in Massachusetts, the state known for the very first Thanksgiving.

[TURKEY GOBBLES]

BASCOMB: Kate Stillman runs a family farm. Behind her mustard-colored farmhouse small fields bordered by stonewalls are dotted with sheep and turkeys. But these are no ordinary turkeys.

Turkey and sheep are pastured together at the Stillman turkey farm. Turkeys eat insects that would otherwise bother the sheep. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

STILLMAN: If you look at the heritage turkeys, their heads are beautiful! These are blue slates that we're looking at and most of their head is this iridescent light sky blue color with a red neck and I mean, the colors are fantastic but they're very reptile looking.

[TURKEY GOBBLES]

BASCOMB: Kate and her husband Aidan raised 50 heritage turkeys this year. They also raised about 200 of the more conventional white turkeys.

STILLMAN: The heritage ones are—well, they look like they don’t have that big of breasts. They're a little leaner, slimmer birds.

BASCOMB: But a trim turkey with a small breast isn't what most people want on their Thanksgiving table.

SMITH: For whatever reason, Americans love the breast and the white meat.

BASCOMB: Andy Smith is a turkey historian. He wrote the book on turkeys—literally. His book, “Turkey: An American Tale,” traces the history of our favorite fowl. The first European explorers took wild American turkeys back to Europe where breeders started to raise them—for their feathers.

Where did its face go? Many species of heirloom turkeys have brightly colored wrinkly skin. (Photo: Marc Renaghan)

SMITH: And hence their names: black and white and Bourbon red and buff and slate, etcetera. The exception to that of course was the bronze turkey, which was the largest heritage breed and had the largest breast.

BASCOMB: That broad-breasted bronze was crossed with the Holland White to create the turkey we know today—73 million of them will be eaten over the holidays. Smith says most of them are raised on factory farms.

SMITH: They've had their toes snipped off a few days after birth. They've had their beaks snipped off in order to prevent turkeys from attacking each other, which they do in confined spaces.

BASCOMB: Milton Madison, senior agricultural economist at the USDA, says most turkeys are kept in big barns. And as for removing beaks and toes, he describes it as more of a turkey pedicure.

MADISON: At times the toes and beaks will be trimmed slightly so that they're a little more blunt. Similar to trimming your finger nails so that you don't scratch yourself or others around you.

[TURKEYS GOBBLE]

A Blue Slate tom turkey struts his stuff. (Photo: Marc Renaghan)

BASCOMB: Raising free-range heirloom turkeys is more expensive than mass producing them. They cost three times as much to buy as babies, and take several months longer to mature. A heritage turkey from the Stillman’s will cost $100, compared with about $60 for the traditional birds. But people are willing to pay. Don Schrider of the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy says that’s going to help save these birds from extinction.

SCHRIDER: If people eat heritage turkeys then more breeding stock is maintained and then the next season more heritage turkeys can be produced. And it actually gives them a job and the population grows.

BASCOMB: The number of heirloom birds has increased eight fold in the last ten years. Farmer Kate says people like the taste of the old-fashioned birds.

Kate Stillman is a farmer in Hardwick, Massachusetts. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

STILLMAN: The heritage birds have a higher percentage of dark meat, which for dark meat lovers—I mean, that’s usually the more flavorful part of the turkey. Almost everybody who ordered a turkey from us last year has ordered two turkeys. So I don't know if they're thinking they're going to pop one in the freezer and keep it for Christmas or something like that but people raved about the turkeys.

BASCOMB: The demand's been so great this year that the Stillmans actually ran out of heirloom birds.

STILLMAN: You know, I had somebody call me this morning and she said to me, ‘oh please Kate, can we get a turkey from you, we've been away I really wanted to call.’ And she's been a really good customer. We were supposed to be saving two turkeys for my aunt for Thanksgiving so I called my mother and I’m like, ‘well you guys are only getting one turkey because I really couldn't say no to her.’

BASCOMB: And so come Thursday the Stillmans might go without a heritage turkey at the center of their table, but they’ll have made a lot of Massachusetts families very happy. For Living on Earth, I'm Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: -- By the way, Stillman’s farm has grown since Bobby visited -- this year they’ll sell some 100 heritage turkeys – and 800 conventional ones.

Related links:

- The National Turkey Federation

- Stillman's at the Turkey Farm

- United States Department of Agriculture

- Andrew Smith’s book, The Turkey; An American Story

[MUSIC: Deeper Blue Charles Michael Brotman/Charlie Recaido Deeper Blue Palm Records]

Cranberries Take Centerstage

Although cranberries can be dry-harvested, most of the U.S. crop is harvested when growers flood the fields to collect the berries. (Photo: Massachusetts Office of Travel, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, that first Thanksgiving table in Plymouth, Massachusetts featured a food more American than apple pie—the cranberry, or at least that’s how the legend goes. Cranberries are one of the most healthful foods on the holiday table. But as Living on Earth’s Emily Taylor found when she headed to the cranberry bogs, that’s not why people pile on the cranberry sauce.

CAKOUNES: My name is Leo Cakounes and I run Cape Farm Supply and Cranberry Company.

[MUSIC: Sue Keller "Cranberry Stomp" from 'Ol' Muddy: Riverboat Ragtime-Era Piano Sounds' (HVR - 2003)]

CAKOUNES: Naturally what I think of when I hear the word cranberry is my mortgage payment because basically that's what we do for a living is grow cranberries.

MAN: Thanksgiving time—so cook them up for turkey.

WOMAN: Decoration with cranberries. I decorate during Christmas time with cranberries myself.

MAN: I suppose cranberry sauce and having Thanksgiving dinner is definitely the theme.

Cranberries were originally called “Craneberries” by the Pilgrims because their small, pink blossoms reminded them of the head and bill of a Sandhill crane. (Photo: naturalhistoryman, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CAKOUNES: There's a lot of nostalgia with cranberries, associated with Thanksgiving and that's understandable but for us it's a crop that we grow for the purpose of making a living.

MAN: Well, I used to go wild cranberry picking on the Cape with my dad. He'd always take me up on the dunes and show me all the hotspots.

WOMAN: Umm fifth grade. I don’t know, I think I had a dream about a bog. I don't know. It was kind of weird, but fifth grade.

GIRL: When I think of cranberries I think of coyotes because on Cape Cod there's tons of cranberry bogs and around them thousands of coyotes live there.

MAN: Since I was a child. I think I was fascinated the first time I saw a cranberry bog.

MAN: The bogs and uh, Cape Cod.

CAKOUNES: The harvesting process of cranberries is probably the most interesting process because that's the time of year most people want to come and see a cranberry bog.

WOMAN: (singing) Did you ever go to the cranberry bogs? Some of the houses are hewed out of logs. The walls are of boards that are sawed out of pine. That grow in this country called cranberry mine.

CAKOUNES: There's two basic kinds of harvesting. There's the dry harvest. The dry harvest is done first, usually mid September. It's done when the bog has to be completely dry, that means no dew or anything on it. The dry harvesting produces what's called the fresh fruit. Which is the large cranberries that you buy in the store that the consumer ends up buying, the actual cranberry itself.

WOMAN: He eats them plain, right out of the box. He and his sister both love to eat the cranberries plain.

MAN: I actually eat them plain a lot. I remember going to the museum and seeing them bounce down the little stairway for grating. We'd just pop them in our mouth.

WOMAN: I feel very puckered up and I feel like I'm going to eat something sour. I'm not interested at all (laughs).

Cranberries are one of three native fruits of North American that are grown commercially. (Photo: catharticflux, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MAN: The first time I had real cranberry sauce made with whole cranberries, I was blown away. It was marvelous stuff.

CAKOUNES: The second kind of harvest, which is probably most familiar to people is called the ‘wet harvest.’ And we drive a machine out on the bog which beats the berries off the vine and then coral them with either boards or a cranberry barrier. And then those berries are pumped or loaded into an open truck with a conveyor and then they're shipped to the supplier. And they're actually called processed fruit. Those berries become your concentrate for drinks. They become your cranberry sauce.

MAN: For years I thought cranberry sauce was the stuff shaped like a can.

WOMAN: When I was a kid the only cranberries we ate were out of a can. But my mom would just put it on the plate like, whole in this gelatinous mass, you know. And she'd open up one end and it would just ooze out the other end and be like slurping sounds.

MAN: Canned cranberry sauce is almost never good.

WOMAN: The stuff in a can. You just sort of squish it out of the can and it sits there and jiggles on the plate.

MAN: Slice it.

WOMAN: That's right and you slice it, you can't even serve it with a spoon.

CAKOUNES: The market for fresh fruit hasn't really increased that much. There are still some people out there who are still dedicated to buy fresh cranberries and serve them on their Thanksgiving table and we think that's wonderful. But we are really working hard producing new products. Hoping we can get into the candy market and the cereal market which will pretty much help us year round as opposed to waiting for one Thanksgiving dinner to pay our bills.

CURWOOD: Our cranberry audio postcard was produced by Emily Taylor and Dennis Foley.

Related links:

- Cape Cod Cranberry Growers’ Association

- Bog owner Leo Cakounes’ Cape Farm and Cranberry Company

- Cranberry Marketing Committee – USA

[MUSIC: Sue Keller "Cranberry Stomp" from 'Ol' Muddy: Riverboat Ragtime-Era Piano Sounds']

CURWOOD: Coming up...tasting America’s most unusual native fruit. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Punch Bros. Passepied (Debussy) The Phosphorescent Blues Nonesuch]

Beyond the Headlines

Earlier this year, the WHO said that processed meats cause cancer, but some think that this is a well-timed conspiracy before the COP21 meeting in Paris in December 2015. (Photo: intermac, CC0, public domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Time to catch up with what’s beyond the headlines now. Peter Dykstra’s our guide. He’s with the DailyClimate.org and EHN.org, that’s Environmental Health News, and is on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. A not-so-veiled threat from the EPA caught my eye this week. The federal agency informed the state of North Carolina that its environmental enforcement and regulations are so weak that the Feds may swoop in and take over.

CURWOOD: Whoa, that’s a pretty serious move if it happens. How did it come to this?

DYKSTRA: The big catalyst is a state effort to block local environmental groups from doing something that’s a time-honored part of environmental politics – challenging pollution permits, in this case for a cement plant and a limestone quarry. EPA says the state should not shut out its own citizens from the process. North Carolina says it’s all a big misunderstanding. The federal EPA has tangled with states before for failing to enforce federal pollution laws. But this action comes at a time when many states are already hauling EPA into court over clean energy and water pollution rules, and it’s one to watch. This could play out over months or even years.

CURWOOD: I’m sure you’ll help us keep an eye on it. What’s next?

DYKSTRA: Remember the uproar over the World Health Organization’s report on red and processed meats and cancer risk?

CURWOOD: Of course. It was bacon’s day in the sun about a month ago.

DYKSTRA: Well, I’d recommend against eating month-old bacon that’s been left out in the sun! But that apart, some have seen a sinister motive in all this much ado about meat. Social media, Rush Limbaugh, the Wall Street Journal, and Fox News smell a climate change conspiracy, because after all, large agriculture and meat are bad for the climate, right? A journal op-ed said the WHO report was “particularly well timed” for the Paris climate talks; at least three different Fox News shows defended bacon’s honor while connecting those same dots, and Rush Limbaugh said “these jerks at the United Nations are advancing a political agenda.”

CURWOOD: Uh, so, Peter, did they offer any proof that this was a big conspiracy?

DYKSTRA: Humph, you and your “proof.” You know, that’s why people hate journalists. We’re talking about the United Nations against bacon, for goodness’ sake!

CURWOOD: Yeah, so did they offer any proof?

DYKSTRA: Steve, why do you hate bacon so much?

CURWOOD: Oh, I get it...obfuscation is the name of this game for this sizzling story, huh? Well, all right, let’s pull something out of the history vault for this week instead. What have you got?

DYKSTRA: In November of 1869, the Suez Canal opened, and it changed a lot of things: The Canal cut a few thousand miles off shipping between Europe and Asia. It hosted its first oil shipment via tanker in 1892, and the oil business certainly helped the Canal become a strategic flashpoint, notably in 1956 when Israel, France and Britain invaded Egypt, which caused the Canal to shut for six months. All of which brings us to the environmental side.

CURWOOD: Uh, which is?

DYKSTRA: Well, pretty much from its first days, Suez became a passageway for species, as well as ships. Non-native jellyfish, crabs and other sea life moved between the Red Sea at the south end of the canal, and the Mediterranean at the north end. And since cargo ships have gotten a wee bit bigger since 1869, canals have to grow too. A major expansion plan for Suez has marine scientists worried that the wider, deeper canal could multiply the invasive species problem.

CURWOOD: We’ve covered similar worries about the planned canal across Nicaragua, connecting the Atlantic and the Pacific.

DYKSTRA: Well, they first tried to build the Nicaragua Canal around the same time as Suez, but it failed, and in 1914, the Panama Canal became the shortcut through the Americas.

And one final note on the present, rather than the past: Ken Cohen, the Exxon Mobil spokesman, announced his retirement this past week. He’s been much in the news lately, including an interview with you, Mr. Curwood, a few weeks ago, responding for Exxon to news reports on how the company dealt with information from its own scientists on climate change over the years. Ken Cohen will turn 65 in January, which Exxon says is its mandatory retirement age.

CURWOOD: Well, folks who find themselves in the middle of a storm of criticism don’t always answer interview requests, so whatever you think of the Exxon story, we were grateful that Ken Cohen did agree to come on the show – and we wish him well in his retirement. Peter Dykstra is with EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot, talk to you next time.

CURWOOD: And there’s more at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- EPA: NC risking federal takeover of environmental regulation

- The Climate Agenda Behind the Bacon Scare

- Fox Business Tries And Fails To Prove Climate Agenda Behind Report Linking Bacon To Cancer

- Rush Limbaugh: World Health Organization Scientists Announced Bacon-Cancer Link To "Advance A Political Agenda"

- Building the Suez Canal - 1859-1869

- Egypt's Expansion of the Suez Canal Could Ruin the Mediterranean Sea

- Nicaraguan Canal

- Exxon Mobil Top Public Affairs Executive to Retire in January

[MUSIC: Woody’s version, “So Long it’s Been Good to Know Yah”, Dust Bowl Ballads, RCA Victor]

Pawpaw: America's Forgotten Fruit

Pawpaws grow in clusters of one to six green fruit, which darken to a yellowish-black as they ripen. (Photo: Anna Hesser, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The largest edible fruit native to the United States was once a treat and a source of sustenance for everyone from Native Americans, presidents, and enslaved African Americans. Today it can still be freely foraged in the forests of some 26 states. Chances are, though, you’ve never tasted and only ever sung about the pawpaw. Andrew Moore explores the economic, biological and cultural reasons for our naiveté about this singular fruit in his new book, Pawpaw: In Search of America’s Forgotten Fruit. He joins us now. Andrew, welcome to Living on Earth.

MOORE: Steve, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: You've brought in your book, "Pawpaw: In Search of America’s Forgotten Fruit" and you've brought in a pawpaw.

MOORE: Yes, a pawpaw itself, and this is maybe one of the last pawpaws that I'll be lucky enough to get this year.

CURWOOD: Describe it for us please.

The taste of the pawpaw is usually described as a cross between a banana and a mango, but Moore says that subtler flavors like vanilla, caramel, and melon can also be discerned in the fruit, and its flesh varies in color from pale yellow to orange. (Photo: Mr.TinDC, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MOORE: It kind of looks to me like a small mango. It's very green. Some other people describe it, it kind of looks like a russet potato.

CURWOOD: It is really fragrant.

MOORE: Really fragrant. The studio is really filled with the aroma now.

CURWOOD: I describe it as almost a mango aroma as well, so I've got to ask what it taste like?

MOORE: Sure, so you mentioned mango already and a lot of people do describe it commonly it as a cross between a banana and a mango and what that's really getting at is that it has an unusual tropical flavor for an otherwise temperate fruit, and then the banana aspect gets at this creamy texture that the pawpaw has.

CURWOOD: Well, can I find out?

MOORE: Sure, yeah, do you want to cut into it?

CURWOOD: Yeah, OK, you go ahead. You're the expert cutter here.

[SOUNDS OF KNIFE ON PLATE AND CUTTING]

MOORE: The way I like to do it is to cut it in half, kind of like you might an avocado and twist it apart like a double stuff Oreo and then when you do that you reveal essentially two cups of custard. The pulp as you can see is is this vibrant yellow, near orange and in some places, and then you've also revealed a few rows of seeds down the center of the pawpaw and these are all large black lima bean sized seeds that you can pick around or pull apart.

The Ohio Pawpaw Festival, which always takes place at the height of Ohio’s pawpaw season in September, drew a crowd of over 10,000 this year. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: Now, I think it's been 20 or 30 years since I’ve tasted a pawpaw, so here it goes. Yum, that's really good.

MOORE: Does it taste like you remember?

CURWOOD: Yeah it tastes like it's got this slight little tangy edge to the banana, but it's mango, but no wait it's banana, no, wait it's mango and it's delicious. You know there are a lot of things one can do in life, Andy, why have you spent so much time researching traveling around paying attention to pawpaw? What drew you to the pawpaw?

MOORE: When I learned about it, first of all what happened was I was captivated. I was at the Ohio pawpaw festival and out in the woods, outside of the festival fairgrounds is a patch of wild pawpaws, and the experience of picking pawpaws from the trees, of picking them up from the ground, this wild bounty, this tropical tasting fruit that I had never heard of, that none of my family or most of my friends have never really heard of this thing, I was fascinated that something this good, this large, it's the largest edible fruit in the Native American woods, that it could be so unknown. And so I just wanted to learn more, so I just kept researching and and looking online and I met the people who are working with pawpaws and I was certain that I wanted to write a story because I realize it had a really compelling human story as well.

CURWOOD: So you started on a pawpaw quest. What's it like to go pawpaw hunting?

MOORE: It's a lot of fun, and that was another reason why I set out writing the book. It was just it was really fun to go to these places, whether it was wild patches on the banks of the Mississippi or whether it was Monticello in Mount Vernon or an experimental orchard where people were growing pawpaws and doing selective breeding. It was just a lot of fun to go to these places and and meet these people.

CURWOOD: By the way, describe the pawpaw tree for me. What's it look like?

MOORE: Sure. Yeah, the pawpaw tree, and again it's confusing to me as to why it would be so unknown because the tree is beautiful as well. It has this lovely pyramidal shape when grown in full sun and it has these long tropical looking leaves. There are among the broadest and a longest leaves you'll find in eastern forests and in fall they turn a striking yellow.

CURWOOD: And where can you find pawpaws?

MOORE: I often say that the pawpaw is a river fruit. It's native to 26 states in the eastern US and many of these rivers in these states are, in fact, lined with pawpaws in the deep alluvial rich soil and so that's a good place to start looking for them.

CURWOOD: So how come most of us have never heard of the pawpaw?

Pawpaw gelato is one of the more popular creations made from the fruit. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

MOORE: Right, well I call it the forgotten fruit - that's in the subtitle - certainly some people have maintained memories of pawpaws, but for the most part we stopped knowing pawpaws when we stopped going to the woods for food. In the middle of the last century with the rise of supermarkets and global food and industrialized foods, our diets became a lot more homogenized and industrial and something that you would have to go to the woods to gather was left by the wayside. And pawpaws not the only food certainly that we stopped eating and that we had neglected. There were so many heirloom fruits and vegetables - we had thousands of apples and old tomatoes. And so pawpaw is among those fruits that were lost, but that thankfully we're seeing a revival of.

CURWOOD: So, since it's free and available on the wild and such, what's your favorite survival story of somebody who needed the pawpaw to get over whatever challenge they were meeting?

MOORE: Well, among the early stories are Lewis and Clark subsisting on pawpaws at the end of their expedition along the Missouri River. They had completely run out of food and all they had was the wild bounty of pawpaws. Some people when they talk about it they'll say that the pawpaw saved them from hunger or they were near starvation, but in reality there were just so many pawpaws it was never a concern. They were all content and happy and just eating pawpaws for three days.

Marc Boone harvests pawpaws on his property in Michigan, at the northernmost extent of the pawpaw’s range. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: So, historically, how did Native Americans use the pawpaw?

MOORE: Unfortunately there's not a lot of citations for Native American foodways before Europeans. There are some citations that survive that that we pawpaw people are thankful for. The Iroquois, for one, are cited as having dried pawpaws and cooked them into corncakes, which I found fascinating because corn is low in niacin and pawpaw is high in this nutrient. It's high in antioxidants and some of the same antioxidants that are found in red wine and chocolate. We also know that is high in various vitamins, vitamins A, C, potassium. These old folkways, they develop for a reason and there's a lot of wisdom in them.

CURWOOD: What's the relationship between the pawpaw and people of color?

MOORE: Enslaved African-Americans, they were looking to supplement diets if they had the liberty to pick things from the wild, pawpaws would've been one of those things that they could've gathered each year, as well on the Underground Railroad. Slaves seeking freedom in the north, pawpaw would have kept people alive as they were going north.

A pawpaw grown by Jerry Lehman weighs in at a whopping pound-and-a-half. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: So, as you went on your odyssey around America looking for pawpaw, how many festivals did you get to?

MOORE: There were two prominent festivals that I went to when I was researching: the Ohio which is a large gathering now in its 17th year around 8,000 people come out every year for that, and then in North Carolina which was newer at the time which is also growing. But now there's festivals in Rhode Island and Maryland in New York, Pennsylvania...they're just popping up everywhere and so it's a really fun time for pawpaw people.

CURWOOD: And how do the people who hunted and ate pawpaws a long time ago, say as kids, how do they react now when they taste their first pawpaw in decades?

MOORE: It's a really fun thing to share pawpaws with people who haven't had them in decades. They remember and they say, “oh, I used to love eating these as kids. We'd go on the river and pick them.” If they were coming home from school this was candy for them, they didn't have access to all these sweet foods like we do today, it was such a cherished treat, and it really seems like a personal fruit, everyone has these personal memories of a gathering pawpaws, and that I think some of that has to do with the fact that as children, they did wander and gather these, but they were also shown this by loved ones, grandparents, or parents. It was like a family tradition to go and gather these things.

CURWOOD: The pawpaw place?

MOORE: Yes, the pawpaw place. The picking place.

CURWOOD: What are the various ways that people eat and I guess can even drink pawpaws these days, huh?

MOORE: Yeah these days the skies the limit with what you can do with pawpaw and it's an interesting time. There's some great recipes out there but I think the best things that you can do with the pawpaw are products yet to be seen as people start experimenting with it. I make a pretty good pawpaw ice cream, pawpaw gelatos, sorbets, these are all very wonderful. Crème brûlée even and recently at the Ohio Festival, I tasted pawpawcello, so like a limoncello, a hard pawpaw lemonade and there were 11 pawpaw beers on hand. I didn't get a chance to drink all of them.

CURWOOD: That's right, I mean, good sweet fruit can lead to booze.

MOORE: Booze, absolutely and that's a tradition that goes as far back as the 17, 1800s. People in and around Pittsburgh and in the Ohio Valley down through Ohio were making pawpaw brandy and liquor and beer, and it's been known to be a strong alcohol even from those days on through today.

CURWOOD: Pawpaw kapow.

MOORE: [LAUGHS] That's right.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] What are some of the challenges of cultivating and marketing pawpaws?

MOORE: Often it's said that the pawpaw's short shelf life and it's fragility is why it has not been cultivated. That's a good starting place for talking about problems in domesticating the product. It is soft, and it does have a short shelf life, so it's not necessarily a fruit that lends itself well to sitting on the back of a truck and then going to distribution centers and then sitting on a supermarket shelf for several weeks. So it's just going to have a different niche. It's maybe not going to be something that is found across every Wal-Mart across the country, but it's more likely something that will be found at farmer's markets and local food co-ops.

CURWOOD: And perhaps on a menu of perhaps a local restaurant.

MOORE: Absolutely. We're seeing that more and more from New York to Missouri, chefs are adding it into their menus and doing wonderful things to it.

Author Andrew Moore found numerous pawpaw trees in easternmost Kentucky. (Photo: Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: Now, at one point in your book you write about Neil Peterson working to improve pawpaw traits. Tell me his story.

MOORE: Sure, he's often described as a Johnny Pawpawseed character. He was a graduate student at WVU and he tasted his first pawpaw along the banks of the Monongahela, and like myself and so many others, he was excited and eager to learn more, and as a plant scientist and a horticulturalist, Neal had the skills to try to do something with it, so he set about doing a breeding experiment, and he started crossing the country himself seeking out old plantings and old cultivars from 50, 60 years ago when people had a greater interest in pawpaw and had started selecting pawpaws and naming them. So he planted two orchards with well over a thousand trees and after several decades selected the best pawpaws and released them to the public. Neal named his pawpaws after American rivers with Indian names in tribute to the original horticulturalists of the fruit - so Susquehanna, Shenandoah, Potomac - those are Neal's pawpaws and they're considered by many to be among the best that are available.

CURWOOD: Andy, could you please read from your book?

MOORE: I'd be happy to.

CURWOOD: Just describe for me with what's going on here when the search for the Ketter fruit.

MOORE: Yeah, in Ironton, Ohio I had been looking for the lost Ketter fruit. It was that prize-winning fruit from the 1916 contest for the best pawpaws in America, and I spent about three days searching for it.

[READING] In the morning, after a biscuit and fried apple breakfast, I decided to look for the trees planted by the uncle of my waitress at Jim's. Since the Ketter fruit has thus far eluded me it would be a boost in my sleuthing esteem to at least track down something. I find them, a massive pair, each 30 or 40 feet tall reaching above the power lines, and more or less right where she said they would be. Their leaves are deep green and yellow at the top of each pyramidal shape they've managed to make a Bradford pear or a black walnut look small in comparison. I stand in the grass taking photos when a neighbor calls out to me from her porch across the road. "Some people want to cut those trees down," she says. I ask why and who. "Just some neighbors on the block," she says. "They just want them gone. Don't want them anymore." I told her I don't see any sense in that. That they're good trees. "Tell me about it," she says. "I'm confused by all of it." But at least she offers some explanation as to why some things disappear - whims of the obstinate.

Andrew Moore is a writer and gardener who lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (Photo: courtesy of Andrew Moore)

CURWOOD: How many of these do have in your backyard now?

MOORE: I have three trees in my backyard. It is a small backyard otherwise I might have more.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] And are they big enough to produce fruit yet?

MOORE: I'm hoping to get my first for next year actually. The flower buds have formed and I'll see them next spring and hopefully we get some fruit.

CURWOOD: So where oh where is little Andy?

MOORE: Way down yonder.

CURWOOD: In his pawpaw patch, huh? Andrew Moore is a writer and gardener living in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, just within the range of the pawpaw. "Pawpaw" is his first book. Andy, thanks so much for taking the time.

MOORE: Steve, thanks so much for talking to me.

Related links:

- Pawpaw: In Search of America’s Forgotten Fruit

- About the pawpaw fruit

- The Ohio Pawpaw Festival

- The Kentucky State University Pawpaw Program

- Facts about pawpaws

[MUSIC: Clark Jones, Paw Paw Patch, Early American Folk Music and Songs, Folkways]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you from the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, and Jennifer Marquis. We’re joined by a new intern today – Amber Rodriguez; welcome aboard!

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Kendeda Fund, and Trinity University Press, publisher of Moral Ground; Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril, 80 visionaries who agree with Pope Francis, climate change is a moral issue for each of us. TU Press.org, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth