September 16, 2016

Air Date: September 16, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Standing Rock And The Feds

View the page for this story

After a judge denied a halt to construction of the section of the Dakota Access pipeline that borders the Standing Rock Sioux Nation reservation, three federal agencies issued a joint hold on the portion in dispute. This marks a change in attitude by the federal government concerning Native American rights. Host Steve Curwood turned to Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau to explain the legal basis of this action and what it implies in future. (10:00)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, Peter Dykstra brought host Steve Curwood a touch of whimsy, with news of a new parasite that bears President Obama’s name, joining beetles honoring other presidents and prominent figures. Also, the big changes Tesla hopes to make to the auto sales model, and a reflection on the Hurricane of ’38. (04:55)

War Veterans Farm For Health

/ Sean PowersView the page for this story

Veterans must often wait months for health appointments at V-A facilities. So a combat vet in Georgia founded a farm designed to immerse returning soldiers in the restorative rigors of working the land, a special boost for those suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Reporter Sean Powers has the story. (06:20)

From Orange To Green

View the page for this story

Former prison inmates are planting trees in Baltimore, helping to rejuvenate some of the city’s tough poor and crime-ridden neighborhoods. Alex Smith, head of field operations for the Baltimore Tree Trust spent 15 years in prison. He tells host Steve Curwood how planting urban trees is turning lives around and remaking the city. (11:05)

'Fish Guy' Aims To Scan All The Fishes

View the page for this story

University of Washington biology professor Adam Summers has a deep ambition: to make CT scans of every species of fish in the world, and he is well on his way. Summers tells host Steve Curwood how he is achieving this goal and why researchers anywhere have free access to this growing database of digitized images. (14:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Alex Smith, Adam Summers

REPORTERS: Sean Powers, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. As Dakota pipeline protests continue the Obama Administration overrides a federal court decision, blocks construction and calls for better consultation with Native American Nations.

PARENTEAU: Native Americans have kind of fallen off the radar screen in terms of politics and in terms of attention. I think this exemplifies that there's a strong feeling within what we call Indian Country that they too are suffering from a lack of respect, a lack of consideration from the federal government.

CURWOOD: How this decision could change those relations in the future. Also, calling in farm animals to help war veterans deal with Post Traumatic Stress disorder.

JACKSON: Animals don’t care about your bad day. They’re going to come up and they’re like, “I want you to pet me.” You’re like, “Ok, but I’m feeling really mad right now, but I’m petting you,” and, man, they don’t know the amazing stuff they’re doing for our vets who come through.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada Zoetrope from In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Standing Rock And The Feds

The Sacred Stone Camp where the Sioux and their allies have been camping out in a collective show of dissent for the Dakota Access pipeline project. (Tony Webster, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. When the Obama Administration overrode a federal judge to temporarily halt construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, it marked a turning point in what is now a mass movement for Native American rights. For years Native Americans have seen their ancestral lands mined, flooded, and appropriated, desecrating holy ground, gravesites and artifacts. And after the Army Corps of Engineers approved the pipeline route through sites revered by the Standing Rock Sioux Nation, it ignited a prairie fire of protest with thousands demonstrating and blocking construction. After a federal judge refused to order a temporary halt of the pipeline on Sept 9th, the Army Corps, Justice and Interior Departments immediately stepped in and suspended the project on federally owned land, and urged the developers to stop work on adjacent private property. To explain the issues at play here, we turn to Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau. Welcome back to the program, Pat.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, after the judge decided here, why did the federal agencies step in and intervene?

PARENTEAU: I think the word came down, frankly, from the White House to the Justice Department and to the Corps of Engineers to take another look at this situation. Some evidence had come to light that the company building this pipeline had actually bulldozed sites of extreme importance to the Standing Rock tribe and the news obviously of the protests and some of the violence, some of the security guards had literally sicced dogs on some other protesters. So it looks to me like higher authorities stepped in and said we need to take another look at this case.

CURWOOD: Well, how much of a precedent is this, do you think?

PARENTEAU: I haven't seen anything quite this rapid before where literally within hours of a judge's decision the government completely turned around and said, “We are going to stop the construction that's going on around the crossing of the Missouri River near the tribe's reservation, and we are going to look at this again and maybe do a more full environmental review and also importantly do a better job of consulting with the tribal government.”

CURWOOD: Yes, some of the folks in Indian country are saying this recent action by the Obama administration could turn around literally generations of bad treatment in bad faith. Is this a game changer?

PARENTEAU: I think there are significant implications. I mean, this echoes back to all that that violence around the Wounded Knee occupation, and Native Americans have kind of fallen off the radar screen in terms of politics and in terms of attention. I think this exemplifies that there's a strong feeling within what we call Indian Country that they too are suffering from a lack of respect, a lack of consideration from the federal government, and the fact that there are 120 tribes on site at this point says a lot.

CURWOOD: Remind folks whose memory might not be that long about what happened at Wounded Knee.

PARENTEAU: Right. So this is in the 1970s, early 1970s when this protest movement occurred. The Native tribes all came together and made a stand against what they perceive to be - This is going to have echoes of what we're seeing today with the Black Lives Matter movement - a pattern of abuse from law enforcement were Indians were being singled out for particularly harsh treatment in terms of prosecution, where they were actually forbidden to use some of their Lakota practices which, of course, involves things like Sweetgrass ceremonies and peyote and some other things that might be controversial. But the point is that the Native peoples were saying you know these are parts of our culture our religion and you're curtailing those, and so this was a very strong protest from the Native communities. It ended quite violently with people being killed, people being prosecuted and eventually the federal government taking control for a while.

Demonstrators marching near the pipeline site that’s hotly contested by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in court. (Joe Brusky, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what are the broad requirements here that, at least according to the Indians, the Army Corps of Engineers went wrong with?

PARENTEAU: The major one is under the National Historic Preservation Act which protects obviously historic properties, but it also protects archaeological resources, artifacts, including Indian tribal artifacts. There's a lot of that. I mean you can imagine how long the Sioux tribes have occupied these lands. There's graves. There are religious sites. There are historic sites, and this pipeline is running right through the middle of all of that, and there is evidence that some of the bulldozing that was done in a hurry to try to beat the court's decision did in fact destroy some of these of these artifacts.

CURWOOD: So, Pat, how might this affect her future decisions like this?

PARENTEAU: The core of this issue is what's called government to government consultation on major projects like this. And one of the things I noticed when reading the court's decision here is that the judge completely missed the point that, from the tribe's perspective, what they expected to happen was the highest ranking official of the Corps of Engineers - This would be the Colonel in the district office in Omaha Nebraska - They expected the Colonel to reach out to the Tribal Chairman and engage in discussions at that level. Instead what you had is the Corps staff engaging the staff of the reservation and a complete disconnect between the two authorities, and that's at the core of this. The federal government just has to learn that tribes expect a protocol that recognizes their hierarchy and to take advantage of that means of communication. That, I think, is going to change.

CURWOOD: Pat, what was the reasoning that the judge, the district court judge, offered for denying the injunction by the Standing Rock tribe?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, he labored over this. He showed a lot of sympathy towards the tribe. I think he was actually looking for a reason to agree with them, but when he went through the history of sort of miscommunication between the Corps and the tribes he concluded the tribe was as guilty of failing to consult as was the Corps, that the Corps made these various overtures to tribal staff members and didn't get responses, and for a federal judge looking at an administrative record being under the deference doctrine that you're supposed to defer to agencies, he felt he didn't have enough evidence to charge the Corps with violating this consultation requirement. The other thing that he said was the tribe didn't prove, before him at least, that the construction was actually threatening or actually destroying some of their resources. That is called into question by the fact as there are some other indications that there was damage to tribal resources. So it's not entirely clear that the judge had all of the evidence in front of him, that maybe there was, and on appeal it'll be interesting to see what happens with some of that.

Pat Parenteau is an environmental law expert and a professor at the Vermont Law School. (Photo: Vermont Law School)

CURWOOD: Well, look into your crystal ball. What have they offered on appeal and how might the Circuit Court of Appeals look at this, do you think?

PARENTEAU: I think if the tribe is able to convince the Court of Appeals that there is an imminent threat to important tribal resources, they have a good chance of convincing the court to actually issue a stay and an injunction. The scope of that injunction is still open to question, how much of the line...but I think there's enough of a serious question about the Corps’compliance with the Historic Preservation Act, and there's some other laws that apply that as long as the court is convinced that it should step in and stop construction I think there's a good chance it'll do that.

CURWOOD: To what extent is this politics? A presidential election year...Green party presidential candidate Jill Stein has warrant out for her arrest. How political is all of this?

PARENTEAU: Well, you know, it does have overtones of and environmental justice. That does play into the narrative of this particular election campaign where we have disadvantaged people being very upset and angry that the government is not listening to them and not taking care of their concerns, and this is a manifestation of that, I think. This pipeline was originally scheduled to be routed north of Bismarck, which is quite a ways up river from the tribal reservation, and there was an outcry from the citizens in Bismarck, saying,“We don't want a pipeline running near our water supply. Move it.” And so they moved it down to the reservation, and the tribe I think is a legitimate complaint to say, “If it was too dangerous for Bismarck, it's too dangerous for us.”

Thousands across the nation have marched in solidarity with the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, invoking the popular “keep it in the ground” phrase, which was also used to protest other pipelines such as Keystone XL. (Photo: Peg Hunter, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: How vulnerable is all this, if the White House changes parties? If Mr. Trump takes the White House as opposed to the Democrat Hillary Clinton?

PARENTEAU: Well, everything's at risk if Mr. Trump wins the election. All of these laws and enforcement of environmental laws…I mean, Trump has already called for abolishing the EPA, so I think that gives you some indication of where he stands on some of these environmental issues, but that's a game changer for sure. If Mr. Trump wins the election, all bets are off in terms of how the federal government honors these commitments to the tribes and probably the other communities.

CURWOOD: Pat, to what extent is all this related to the Keep It In The Ground movement that a number folks are very concerned about doing any more infrastructure to advance fossil fuel resources?

PARENTEAU: I think it's directly related, Steve. We just signed the Paris agreement again, ratified it in the language of international negotiations along with China, and in that agreement we committed to reducing our greenhouse gases by 28 percent by 2030, and the only way you are really meet those commitments is to phase out fossil fuel reliance and infrastructure like this pipeline. That is the bigger story here, is this continued sort of schizophrenia on the part of the federal government on the one hand for the clean power plan trying to reduce emissions and on the other hand granting permits to infrastructure like oil pipelines. They're working at cross purposes and we've got to sort that out.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a professor of law at the Vermont Law School. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Pat.

PARENTEAU: You're certainly welcome, Steve.

Related links:

- Joint statement from federal agencies

- Live updates on lawsuit progress

- District Court Judge injunction ruling

- Democracy Now! footage of the bulldozing of sacred sites

Beyond The Headlines

Naming a parasitic flatworm Baracktrema Obamai was apparently meant as an honor to the president. (Photo: Marc Nozell, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time to visit with Peter Dykstra in Conyers, Georgia now. Peter's with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org and he's been busy probing the world beyond the headlines. He's on the line now. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. As President Obama prepares to leave office, his admirers will line up the accolades just like most other presidents of any political stripe. Last week, a retired biologist who’s both an admirer and a distant relative of the President named a newly discovered creature in his honor.

CURWOOD: A new creature...what?

DYKSTRA: The new species is Baracktrema Obamai, a two-inch flatworm that's a parasite and makes its home in the bloodstreams of turtles. It joins a spider, two small fish species, a prehistoric lizard, another parasitic worm, and a rainforest bird named to honor Obama.

CURWOOD: Parasitic worm, I’m thinking the President’s going to be offended.

DYKSTRA: Well I don't see why. After all, one of President George W. Bush’s admirers in the biology community discovered four new species of slime mold beetles and named one Agathidium Bushi in honor of the 43rd President. Then he christened two other slime mold beetle species - Agathidium Cheneyi and Agathidium Rumsfeldi, in what he insists was a compliment to all three men.

CURWOOD: And just whom did he honor with his fourth slime mold beetle discovery?

DYKSTRA: Well that was Darth Vader.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] You've got to be making this up!

DYKSTRA: No this is probably one of those times when I have to insist that I’m not making this up.

CURWOOD: Peter, uh, don’t they usually name – you know - federal buildings and airports and high schools after Presidents?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, in fact they renamed EPA headquarters after Bill Clinton a few years ago, and that building is right next to the Ronald Reagan Federal Building.

CURWOOD: See, the list goes on, right?

DYKSTRA: Yes, here are some more examples: NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, not far from George H. W. Bush Intercontinental Airport; Richard Nixon High School, but that’s in Liberia, and the Navy’s nuclear-powered attack submarine, the Jimmy Carter. I always thought that last one was a little special, since President Carter served aboard submarines when he was in the Navy.

CURWOOD: But like President George W. Bush and Homer Simpson, he couldn’t quite pronounce the word “nuclear”.

DYKSTRA: Yeah it's more like “nucular”.

CURWOOD: And now it’s flatworms and slime mold beetles. I can already hear the Marine Band playing Hail to the Parasite. What do you have next for us?

DYKSTRA: The beginnings of a political and economic battle that could have huge implications for the environment and not only that – our car culture and our home-towns. The electric car-maker Tesla is obviously challenging how we power our cars, but, you know what? They’re also threatening to take down the time-honored, legally-binding way we sell cars.

CURWOOD: You mean with screamingly loud TV commercials for car dealerships?

Your next Tesla car might not come from a dealer because of the company’s new direct-to-consumer business model that’s upsetting traditional car dealerships. (Photo: Chris Baird, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: In a way, yeah. The established automakers all work through a system where they can’t sell cars directly. They have to work through locally-owned dealerships. Tesla’s challenging that, and they’ve been cleared in nearly half the U.S. states to sell directly to consumers without the middle-man dealerships. And there are signs that the big U.S. automakers and their foreign competitors may follow their lead, moving to a system that’s based more on online sales, with showrooms that don’t have a sea of new cars parked outside ready to be bought and driven away.

CURWOOD: Well Tesla may want that kind of direct sales system, and others may follow, but I can’t imagine that local car dealers are all that pleased.

DYKSTRA: Oh, no. The National Automobile Dealers Association is now the biggest-spending lobby group in the whole auto industry. The Tesla marketing model is clearly more efficient, but there’s an argument for old-school dealerships that’s a little bit more than sentimental. Auto dealers may be spending more on lobbying, but they’re also a traditional cornerstone of support for local charities – like hospitals, schools, non profits, youth sports, and a lot more. It’s potentially one more triumph for Wall Street over Main Street.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Well let’s move on now to the weekly history lesson.

DYKSTRA: You know, we’re a little bit past the halfway point in the Atlantic Hurricane season. Let’s cross our fingers that we don’t get anything like what happened on Sept 21st 78 years ago, when the Hurricane of 1938 took between 600 and 700 lives on Long Island and in Southern New England.

Fallen trees in Wolfeboro, New Hampshire in the aftermath of the New England Hurricane of 1938. (Photo: Lakewentworth, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

CURWOOD: Well, thankfully we don’t have death tolls that high here anymore, what with better forecasts and warning systems.

DYKSTRA: You’re absolutely right about loss of life, but consider this: If the Hurricane of ‘38 hit today along a much more densely-developed coastline, the damage would be epic. It was a category three storm at landfall, with some weather stations reporting wind gusts up to 180 miles per hour, a 12-foot storm surge that swamped downtown Providence, Rhode Island, and serious in-shore flooding from heavy rains.

CURWOOD: And heavier rains are just what we're promised with global warming. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter, talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: Thank you, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on all these stories at our website LOE.org.

DYKSTRA: Oh, and, Steve, don't forget...Hail to the Parasitic Flatworm!

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

Related links:

- Barack Obama is officially now a parasite (it’s an honor)

- Weird species named after celebrities

- Washington Post: “The battle between Tesla and your neighborhood car dealership”

- NOAA on the Hurricane of 1938

- Book: “The Great Hurricane: 1938”

[MUSIC: “Hail To The Chief” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxgoajDI1WQ]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...greening the mean streets of Baltimore with some of the folks that used to make them mean. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Elaine LaZizza Cronin, “The Water Is Wide,” Folk Salad, Traditional American, Off the Record]

War Veterans Farm For Health

Veterans care for livestock and grow fresh produce at Comfort Farms in Milledgeville, Georgia. (Photo: Comfort Farms)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The US Department of Veterans' Affairs recently reported that more than a half a million veterans are waiting longer than 30 days for their mental and physical health appointments at the VA. That’s up from this time a year ago. But there is an imaginative and novel push in Georgia to improve care for vets by helping them connect with their roots - down on the farm. Reporter Sean Powers of Georgia Public Broadcasting has the story.

[SOUNDS OF OUTDOORS, GOATS]

POWERS: On a 25-acre farm in rural Milledgeville, in Baldwin County, Jon Jackson looks through a gate separating him from his goats.

JACKSON: Animals don’t care about your bad day. They’re going to come up and they’re like, “I want you to pet me.” Your know? And you’re like, “Ok, but I’m feeling really mad right now, but I’m petting you,” and, man, they don’t know the amazing stuff they do for our vets who come through.

Jon Jackson, a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, tends to his farm. He has been introducing other vets to farming to combat the emotional and physical scars of war. (Photo: Sean Powers)

POWERS: It’s been a long journey for Jackson, going from battlefield to farmland. He served six tours in Iraq and Afghanistan and returned home with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. Getting care has been a challenge. Initially he was seeing a psychiatrist at the VA center in Tuskegee, Alabama. But, he says, he was told he had to wait six months between appointments. Last year he had a meltdown. He called the VA’s crisis hotline, and he says the earliest they could see him was in eight weeks. After a lot of pushing, they moved that up to two weeks, but Jackson says it shouldn’t have been that hard.

JACKSON: Every appointment that I got with them was because “No I need to see you right now.” I had to push it and it was like I’m fighting, fighting, fighting. You know what, man? You get sick and tired of fighting. Why am I fighting for care? Well, guess what happened within that six months? Guess what happened? I come back, and I find I got diabetes. So, I’m taking all these medications. You know, there’s nobody watching Jon Jackson.

POWERS: Well, that’s not entirely true anymore…

[ROOSTER CROWS.]

POWERS: Instead of waiting for care, Jackson wanted more immediate attention. So, he moved to Milledgeville with his family, started going to a nearby VA facility in Dublin, where he says care is better, and he started a farm. It’s called Comfort Farms, named after a friend of Jackson's who was killed in action in Afghanistan. Comfort Farms is ripe with everything from okra and tomatoes to chickens and pigs.

[PIGS GRUNTING]

POWERS: For Jackson, farming fits like a glove as he readjusts to civilian life with the scars of war.

JACKSON: You know, farming is chaos and I like chaos. So, it’s just like one of those things where I’m constantly here, struggling against Mother Nature, struggling against pests, but, you know, when you win, you get those small battles, those small victories.

Veterans and volunteers gather to celebrate a September 2016 donation to Stag Vets, the nonprofit that runs Comfort Farms. (Photo: Comfort Farms)

POWERS: Veterans coming back from conflict often struggle with transition to civilian life. They have higher rates of depression and suicide, and are more likely to be unemployed. Jackson hopes to change that by introducing more vets to farming. He’s got a USDA grant to travel the state training vets on agriculture. 150 vets and their families have visited his farm so far this year. One of them is Thomas Scott Kennedy, who also suffers from PTSD.

[SOUND OF CAR DRIVING]

POWERS: I’m in his car as we ride to the VA center in Dublin, where he has three appointments that were scheduled a little less than a month ago. VA data released in August shows on average 92 percent of vets with appointments are waiting 30 days or less for care. Kennedy says working on the Comfort Farms helps him while he waits.

KENNEDY: You’re dealing with the VA on a every other week, every once a month type of situation where in the farming environment with Jon and the farm, every morning you’re up doing something. You’re taking care of the animals. You’re looking outward. You’re not looking inward. That’s helpful.

POWERS: That’s a huge leap from where he was a few months ago. During Memorial Day, he charged head-first into the side of his house. His family watched in horror as blood ran down his head. His wife applied for a protective order. A judge ordered Kennedy to stay away from his family for a year.

KENNEDY: And that basically sent me over the edge again, and that’s when I went into the woods and starting taking medications in order to end my life.

NEWS ANCHOR: Investigators in Oglethorpe County are looking for a missing Marine veteran who they say could be suicidal, 49-year-old Thomas Scott Kennedy last seen June 2nd. He drives a silver, 2004 Toyota Tundra…

POWERS: A friend found Kennedy and connected him with Jon Jackson. Now Kennedy lives on Jackson’s property,on one condition – that he helps on the farm. Melinda Paige is a counselor in Atlanta. She works with people suffering from PTSD and she says having them work together - like on a farm - can help stimulate brain activity.

PAIGE: I believe they do better when they have a shared mission. They’re extremely resilient, strong individuals and since PTSD is a medical condition, it’s a treatable medical condition, it means their brain is simply injured by the high stress that they’ve lived with and can be healed.

Reporter Sean Powers talks with veteran Thomas Scott Kennedy as they head to the Carl Vinson Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Dublin, Georgia. (Photo: Sean Powers)

POWERS: Nearly half of veterans returning from Iraq & Afghanistan are from rural areas. But the USDA says very few go into farming. The director of the Dublin VA sees her center’s location in rural Georgia as an opportunity. Maryalice Morro is talking with the state’s Department of Agriculture about growing fresh produce on site that can be used in her center’s cafeteria.

MORRO: We house approximately 115 veterans in our domiciliary, mental health rehabilitation program that helps veterans with homelessness, PTSD, substance abuse and/or a combination of those get back on their feet. They’re usually here for a period of 60 to 90 days, so it would be a great way to teach them new skills or give them something to do while they’re here. Could be therapeutic.

POWERS: There are still a lot of unknowns about the benefits of farming for veterans. But it may take off as the nation’s farmers get older, and the VA searches for ways to improve care while cutting down on wait times. For Living on Earth, I’m Sean Powers in Atlanta.

Related links:

- More about Comfort Farms

- The nonprofit Stag Vets uses farming in part to promote veterans’ mental health

- National Center for PTSD

- About reporter Sean Powers

[MUSIC: David Coffin, “Processional/Two Polkas,” Flight Of Time, Traditional French (after the playing of Cabestan), Good Dog Records]

From Orange To Green

Crews with Baltimore Tree Trust plant trees on the sidewalks in front of rowhouses (Photo: Baltimore Tree Trust)

CURWOOD: From life on the farm, to life in the gritty inner city. In the predominantly black and low-income neighborhoods of Baltimore, violent crime is all too commonplace along bleak asphalt and concrete streets. But there is now an effort to green these neighborhoods and uplift residents by putting them to work planting trees. In particular, nonprofits are giving former inmates and would-be drug dealers the opportunity to take ownership of their home turf, while earning a living wage. Among them is Alex Smith, who spent 15 years in prison but has turned over the proverbial new leaf and now works for the Baltimore Tree Trust. Alex, welcome to Living on Earth.

SMITH: Hey, how are you doing?

CURWOOD: Good. Hey first, tell me what you do as a staff member of the Baltimore Tree Trust?

SMITH: Well, my official title is Field Operations and Outreach. Essentially, I'm a foreman and I work with fellas and ladies who come from rough backgrounds, and we go out and plant trees all over Baltimore.

CURWOOD: Even when it's hot?

SMITH: Even when it's hot. It's hot today and I just finished planting some Zelkovas.

CURWOOD: Zelkovas. What are those?

SMITH: They are a good hardy street tree. They are one of the most popular trees that we plant.

CURWOOD: Alex, I understand that you were in prison for some 15 years or so before joining the Tree Trust. What was that like and how did you make the most of your time behind bars?

SMITH: I don't really know how to explain prison to anybody who hasn't been there. I can sum it up in two words: It sucks.

CURWOOD: Well, how did you make the most of your time behind bars?

SMITH: Reading, exercising, studying. Behind bars is actually where I learned horticulture and started working with plants. I'm a certified Master Gardener due to Merlin Cooperative extension program.

CURWOOD: And what inspired you to get into working with plants, working with gardens?

Alex Smith leads the field operations and outreach effort at Baltimore Tree Trust. (Photo: Baltimore Tree Trust)

SMITH: Well, they had a little horticulture program. It was a guy that came from Frostburg University, Dr. Wayne Yoder. He would come there and teach about plants, but it was not like we could put it into practical application. We were just learning about it. But when we approached the staff about a garden, this idea started growing that we could actually transform the grounds and that we could use what we were learning in the classroom inside of the prison.

CURWOOD: How did you feel once you started that horticultural program there in prison, that you were going to green the place?

SMITH: It was definitely a good feeling. It was a feeling that if you know, one, that we were even paid attention to. You know, a lot of times I've written letters to different organizations and they went unanswered or they were simply returned, so, for us to actually have somebody starting to pay attention to us, that exciting to begin with. It was a foundation that actually helped us out, the TKF Foundation. They were already doing meditation gardens around the city. Their only requirement was that we somewhere put a meditational Peace Garden. So we did that right out in front of the chapel.

CURWOOD: At the prison.

SMITH: Yes, in western Maryland, WCI.

CURWOOD: So you build these gardens in the prison and then you get out? How did you find your job with the Baltimore Tree Trust?

Baltimore Tree Trust cares for the trees they plant for the first two years (Photo: Baltimore Tree Trust)

SMITH: Well, I was working a couple of jobs. At the time I was working construction, but you know in construction that you have a lot of downtime because of weather or what have you, so what I was doing was landscaping on the side. Someone suggested I buy a pick up, that I shouldn't let the landscaping skill just sit on the shelf, so I took their advice, and because I volunteer at the Center for Urban Families, I would show some of the people around there, some of the stuff that I could do. Part of it was in hopes to get a couple of new clients, but I was also proud of my work. So I guess Dan walked in and talked to one of the career counselors. Dan Miller, he's the Executive Director of the Baltimore Tree Trust, my boss, he walked in looking for somebody who could work with the Baltimore Tree Trust, and my name came up, and they said I know someone who does that work.

CURWOOD: Now, how do you recruit other people who've had similar experiences, spent time in jail? How do you recruit them to help you plant trees?

SMITH: Well, everywhere I go in Baltimore and I'm asked, “Are you hiring?” So it's pretty easy when I'm in the Baltimore Tree Trust truck, and I have a vest and I'm out working. It's pretty easy to get people who say they're interested in jobs, but mostly I come to the Center for Urban Families and get people that have come through STRIVE program.

CURWOOD: STRIVE. Tell me more about STRIVE.

SMITH: STRIVE is an employment readiness program which basically sharpens up or refreshes people soft skills and it helps them not only get jobs but keep jobs.

CURWOOD: Alex, why plant trees in Baltimore?

Baltimore’s economically-depressed neighborhoods largely lack trees (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

SMITH: One, it's for beautification. You put trees in a block, it changes the whole environment. It's not just concrete and asphalt and brick, but two, it definitely helps our environment. They trap rainwater and the bad stuff that it doesn't get filled by the tree pits and the trees and roots themselves, all the stuff goes right into the Chesapeake Bay. But beautification and how it changes what people see when they look out their window, that's the most important part to me.

CURWOOD: Is there a place with trees in Baltimore that's a particular favorite of yours?

SMITH: Well, it's a place that I haven't planted, but it's a small street near York Road in Baltimore that has full grown trees that just canopy the whole street, like it reminds you of maybe what the block looked like some 56 years ago. Pretty amazing to see these trees. Until I started working for the Baltimore Tree Trust I never really paid attention to them. That's what I envision when I'm out there planting a tree, that one day the tree that I plant will look like that. And we plant some of the same varieties, so you know I'll be checking it out in 30 years, to see.

CURWOOD: How do people in the community respond to the work that you're doing now, planting trees?

SMITH: For the most part, we definitely community support. It is not just the people who are seeking employment or are interested in that way. It is just from normal, everyday people who just like to see trees, like to see people working, but we do have those people who we have to convince that planting trees in the neighborhood, planting trees in front of their house is a good thing. There's a lot of myths about trees bring rats, tree strangle pipes. That's like the number one issue that we get, and some people just they just don't want them because of bugs, mosquitoes. We get all kind of things. When we are out in the community we are definitely armed with information and sometimes, you know, even if you show people, they still don't want the tree.

CURWOOD: What kind of ownership, what kind of responsibility for the trees do people in neighborhoods take once you plant the tree?

SMITH: Well, Baltimore Tree Trust, we give them a bucket that has a lot of pointers on it about trees. We pass out flyers. Part of my job is to do outreach. So, it's not just outreach with the fellas that I hire to help me plant these trees but is outreach in the community to dispel some of the myths about the trees and to teach people who to care for them. But we also maintain the trees for two years after we plant them. So, people in the neighborhood, they see us maintaining the trees and pruning the trees and making sure that we care for the tree, so any chance that I can, I'm always giving people advice and giving him pointers and tips on how to take care of the tree. Some people have actually taken ownership of the trees, you know, “That's my tree.” Even some of the neighbors squabble over whose tree it is. For the people who care about the neighborhood and care about the way the neighborhood looks, we get a pretty good response from those people.

CURWOOD: Now Alex, many neighborhoods you work in are mostly African-American, but the Baltimore Tree Trust is mostly a white institution. How do people respond to that?

SMITH: I've never had anybody directly have a problem with it. I do know that in Baltimore City people do have a feeling that there's a lot of white organizations that come in the city hall without asking, do people want the services or products and things like that, and they just shove them down people's throats. That's what people believe in the neighborhood for the most part. I will like to think that because I was presented this opportunity, it is my chance to try to change that, change that perception. So, what I'd do is knock on people's doors, and I say, hey, a tree is coming. I tell them the laws concerning the tree, but I also ask their opinion about it and sometimes, if they are adamantly against the tree, we don't plant it. I definitely make sure that the community in which we're working in are considered. It’s not that they will open the door one day and see 20 people standing in front of house planting trees.

CURWOOD: Imagine some people might be worried about gentrification, that planting trees could raise property values, and end up pushing out the very people who they are supposed to benefit.

SMITH: That's a definite concern and a lot of people do believe that the trees didn't come until the property values starting raising in some of the neighborhoods that I worked in, and nobody cared about the sidewalks or the streets until people from the outside started investing and remodeling some of the bigger homes in the neighborhood. I really don't know the answer to that, but I know that the Baltimore Tree Trust, we plant trees for everybody. And I don't see any bulldozers or tanks pushing people out of the neighborhood. Even though I can say that you know when you raise prices to a certain level you will squeeze out certain buyers, you know, and that's an issue that is way above Tree Trust. That's an issue that should concern everybody, everybody that is looking to keep Baltimore a city that welcomes everybody. That’s something that we all have to work together on.

The Western Correctional Institution in Maryland, where Alex Smith served 15 years. (Photo: Jon Dawson, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Alex this has worked well for you, helped you turn your life around. What about other prisoners and former prisoners, people getting out of jail trying to establish themselves in communities again?

SMITH: Well, I hope that I'm not an anomaly. I would hope that eventually this catches on because every day that I'm out in the street I see opportunity. While I'm planting trees, I see the tree pits that aren't being taken care of. I see the trees that have been planted years ago that aren't being cared for. I'll see the litter that is in the tree pits. All those are unemployment opportunities. You know if the government, the communities, if they're just a little creative and can see that the opportunities that I see while I'm out there in the street, I think that it definitely can work out for other people.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Alex, tell me about your vision for the future of Baltimore's environment including the trees.

SMITH: My vision for Baltimore and myself is that I learn more about the trees, I learn more about how they impact our environment. I learn more about how I can help other people. I mean, I'm a servant for my community and I feel like I'm blessed to be given this opportunity so every day that I go out in the street is for me, it's an opportunity to give back. You know, I took away so much from the streets and from the neighborhoods. I was the bad element at one time. I just hope that I can have an impact and I can help other people the way I've been helped.

CURWOOD: Alex Smith leads field operations and outreach for the Baltimore Tree Trust. Alex, thanks for taking the time with us today.

SMITH: No problem. Anytime.

Related links:

- Read Rona Kobell’s story for the Chesapeake Bay Journal about ex-cons in green jobs

- Baltimore Tree Trust

- About the gentrification of Baltimore

- About Alex Smith

[MUSIC: Jo Ann Smith, “Rhythm Of the Rain,” Autoharp Legacy, John Claude Gummoe, Arts In the Woods]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how Snickers bars have helped to advance science. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jo Ann Smith, “Rhythm Of the Rain,” Autoharp Legacy, John Claude Gummoe, Arts In the Woods]

'Fish Guy' Aims To Scan All The Fishes

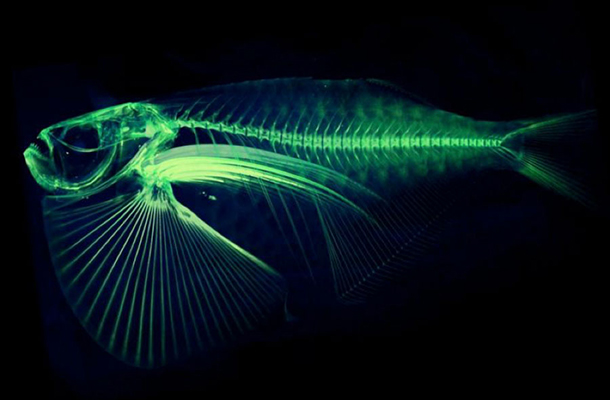

A digitized CT scan of spotfin hatchetfish (Thoracocorax stellatus). (Photo: courtesy of Adam Summers, University of Washington)

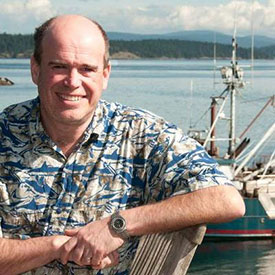

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Some people think big, really big, and that's certainly true of University of Washington biology professor Adam Summers. Often called "the fish guy", Professor Summers wants to make CAT scans of every species of fish on Earth. He also advised the Pixar company on how fish move for the films, "Finding Nemo" and "Finding Dory". To find out how he expects to achieve his hugely ambitious goal we called him up at his lab on San Juan Island off Seattle, Washington. Adam Summers, welcome to Living on Earth.

SUMMERS: Thank you for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So CT scans, CAT scans of every fish on the planet seems like a monumental task. So why are you doing it? Why are you doing this?

SUMMERS: [LAUGHS] I'm doing it because I have a deep fascination with fishes. I mean, a fascination with fishes that started when I was probably two or three years old and proceeded through the sort of fish tanks and fishing and building fly rods and tying flies to giant nets and big tanks and basically devoting my life to doing research on them. And I find their skeletons endlessly fascinating, I mean, just full of fabulous data that I can extract for all sorts of purposes.

CURWOOD: So what do you think all these CT scans will show that we don't already know?

SUMMERS: Well, every single CT scan that I look at I see things we didn't know. I can give you an example. One of the most iconic wrasses - You can look this up on YouTube - is a thing called a Slingjaw wrasse. This animal shoots its jaw out the full length of its head to catch prey. I mean, just explodes out of its head, and the front end is been looked that really deeply. A friend brought one by and he said, "You know, could you CT scan this too, just throw this into your project?" And I grabbed it, and I CT scanned it, and I found that the ribs at the back end of the fish, the end that nobody has looked at are fused. They make a continuous connection between the back end of the dorsal spine, the spinal column, the ribs through to the anal fin spine. It's a huge defensive bulk work against being grabbed by a predator. We had no idea it was there because we've never looked at the skeleton. So skeletons are woefully understudied, and here's an avenue for recording basically everything that's on the inside that's hard tissue.

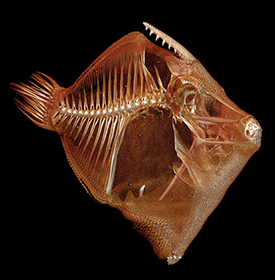

Digitized CT image of a spadenose clingfish (Cochleoceps spatula). (Photo: courtesy of Adam Summers, University of Washington)

CURWOOD: So how do you get this image? I mean does the wrasse stay still or does he have to sacrifice his life for science?

SUMMERS: Well, the wrasse comes to me dead. I scan museum specimens, specimens that have collection data that have a place in a museum so that someday, if someone needs to know something about that particular animal, they can go back and get the very one that we CT scanned, and we have scanned specimens from all the great collections in the United States and several from around the world.

CURWOOD: Aha. OK, I don't have probably enough fingers for this, but how many species of fish are there and how many have you scanned so far?

SUMMERS: So, more or less 33,000.

CURWOOD: OK.

SUMMERS: And we're just clearing 600.

CURWOOD: You have a ways to go.

SUMMERS: We do have a ways to go, but we have been doing it for very long. So we've been doing it since about February and really the big breakthrough came because I, I just got this question over and over again. I use Twitter a fair bit, so I would tweet out these skeletons. I'd say, “Here's my latest CT scan skeleton,” and people would tweet back and say, “Oh, what's up next?” And I'd say, “I can't tell you. I want to scan all of them. I want to scan all fish.” And at the time I was saying it, it seemed like a joke because 33,000, I mean, you pick a number...an hour two hours to scan...three hours to scan. That's more hours than I have left in my career, so it was kind of a joke. But then we realized that we could package these fish up. If you've ever had a CT scan, or seen someone get a CT scan, they get stuck in a donut and the donut passes over their body or their body passes through the donut. Everything in that donut gets scanned, the table they're lying on and, most importantly from my point of view, the air that surrounds them. It would be much more efficient when we CT scan someone if we just piled up all the sick people at once on the table...

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

SUMMERS: .. and shoved them through the doughnut all at once because that would be very efficient and then we scan them and then afterwards we digitally dissect them. Well, that's what we do with the fish. We're not scanning one fish at a time we're scanning 20 so it's not 33,000 scans that we have to do it's more like 1,500 and that becomes a manageable number, and it's important that this is, you know, this scan-all fishes-initiative has touched off a really interesting project run by this guy Dave Blackburn at the University of Florida, to scan all vertebrates. You think I'm ambitious...33,000. He's going to scan every vertebrate, so I am a cog in his machine.

CURWOOD: OK, how many vertebrate species are there?

SUMMERS: Oh we're talking 60, maybe, 60,000. So he's into it. He's doing every single one.

CURWOOD: I'm assuming when you do 20 of these, that they're laid out in a row there.

SUMMERS: No.

CURWOOD: They're all stacked on each other?

Digitized CT image of a fringed filefish (Monocanthus ciliatus). (Photo: courtesy of Adam Summers, University of Washington)

SUMMERS: Here's what we do. So we get in a shipment of fishes from a museum. We arrange them all so they're in the same size class, right? We want all the fish about the same size, and then we take wet cheesecloth because these are in ethanol, these fishes, and we've got to keep him perfectly damp otherwise they dry out, and curl, and museum curators get really angry at me. And you sit there and you put one fish down and you take a photograph of it and you put a little letter on it that's radio opaque so you can tell one from another. Then you roll it in a little bit of cheesecloth and then you set the next fish down, and you take another picture of that one with the little letter on and you keep rolling and rolling and rolling until you have 10, maybe even 20, fish in a big burrito and then you slide this burrito into a can, into a plastic can that we 3D print and you put that plastic can in the CT scanner.

CURWOOD: Huh, I don't know how tasty that burrito would be, Doctor.

SUMMERS: It would be vile, it would be absolutely horrendous tasting because ... not only are fish just terrible to eat. Fish that have been fixed in formalin and then stored in ethanol are just terrible things.

CURWOOD: Oh, wait, you don't eat fish?

SUMMERS: No, I don't.

CURWOOD: They are your friends.

SUMMERS: They are my friends. Fish are my friends.

CURWOOD: OK, now how do you handle something like a whale shark or an ocean-going sunfish?

SUMMERS: So, I've scanned ocean sunfish already.

CURWOOD: That's a big CT scan.

SUMMERS: Nope, because you're forgetting all of them start out really small.

CURWOOD: Oh, babies. [LAUGHS]

SUMMERS: I've scanned the little guys. So I have larval sunfish that I've scanned and you can grab off the twitter feed. You can see these things called ranzania laevis. They're gorgeous spiky little things that look really nothing like the adult, but they're pretty cool. So it's a legitimate question to ask, how am I going to get the big ones? How am I going to get the rare ones? The truth is I'm unconcerned. I mean, if I can get to 30,000 and there's 3,000 left, we're down to the seeds and stems. I mean I'll go to Boeing and use their big CT scanner that they use for jet engines. I'll do whatever I need to do to get the last big ones, but right now the average bony fish is 30 centimeters. I can fit all the average and below fish in, no problem.

CURWOOD: So, so far your workaround about the big fishes are taking pictures of them when they are little, but sometimes they don't look much like their daddies.

SUMMERS: No, there's a huge transformation in most fish between what we call the larval stage and the juvenile stage. Larval fish often look absolutely nothing like the juveniles. So we have typically scanned things from juveniles up to adults, and we're limited in size. So when someone gave me a chance to scan some larval sunfish I jumped at it. They're fabulous looking fish and they're very different than the adults. Someday, we'll get the juvenile and get it in the CT scanner but as juveniles they are the size of dinner plates, so you know even as juveniles they're not little teeny-tiny things.

CURWOOD: So how did you get involved with doing CT scans anyway?

SUMMERS: Well, I've been CT scanning fish since about 1994 or 5, and I got into it because I worked on stingrays that eat hard prey. And these have a cartilagenous skeleton, and they crush snail, and they crush mussels and things for their diet. And I couldn't really understand how that could happen. So I wanted to CT scan some of them, and I wanted to scan a Spotted Eagle ray at first, a beautiful, beautiful fish, to show all of the mineral that was in this cartilage. And what was really neat was, you go around to all these hospitals and say, "Excuse me, um, I'm a graduate student, and I've got a big dead fish I want to CT scan." And invariably, they sort of looked at me like I was completely insane and said, "That's a fabulous idea, but you can't come anywhere near our CT scanner with your big dead fish."

Eventually I found a place that was willing to, if I came at night, let me scan a well wrapped fish, and so I scanned them, and the first time I saw the inside of that skeleton, and I hadn't cut it. You know, I had dissected them all the time, but here was everything in situ, here was everything arranged the way it should be arranged, not arranged the way it happens when you pull apart the tissue and look inside. I was knocked out. I thought this is, this is the best, this is how we have to do this. So I started CT scanning every fish I could find. You know, and I proceeded along. It's very expensive, and we never had any money for this. We never had any funding. So I would beg the CT scan techs to scan stuff for me. I'd give them print outs of the pictures so they could see why we wanted to do it, you know. I think my oddest bartering element was, I had a guy at a CT scan, he was a CT scan tech, he had the use of a CT scanner, and he loved Snickers bars. And I could go in there with a bag of fish and a pocket full of Snickers bars, and he’d let me scan all night.

Digitized CT image of an antlered sculpin (Enophrys diceraus). (Photo: courtesy of Adam Summers, University of Washington)

So, what happened was about a year ago we raised private funds to make the Karel F. Liem Biovisualization Center, and that facility, one of the conditions of these donations which bought a $340,000 CT scanner, one of the conditions was that anyone be allowed to use it for free. There's no disposable costs in a CT scanner, so, you know, it's like turning on and off a light switch. Eventually the bulb fails, but there's a little electricity cost, you get light for free. So, I started circulating the word, you know, "Bring your fish. Let's get everything scanned." And then, we figured out how to scan multiple things at once, and realized we have a shot at actually scanning the vast majority of fish. So these private donors really enabled this project.

CURWOOD: And now you have your own scanner, you don't have to trade Snickers bars, huh.

SUMMERS: I know. The best thing is the Snicker bars come to me. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] OK. So you mentioned that this process has allowed you to apparently identify new species.

SUMMERS: Yes.

CURWOOD: What are some of the other rewards? What are some of the things that you have found using CT scanning?

SUMMERS: So I'm a biomechanist. I'm an undergraduate trained engineer and mathematician who took a PhD in biology after spending a lot of time not doing biology, and what I do as a biologist is, I look for new technological solutions inspired the living world, typically fish, but not always. And I look for new kinds of materials, new ways of doing things that have been, you know, the way an animal lives, and I find inspiration there. So we’ve looked at how fish stick to things. Looking at CT scans of these fish that stick to rocks? These fish stick to rocks that are incredibly irregular. Just basically imagine yourself at the seaside in the crashing waves. You grab a rock. Look at that rock. It's rough, you know, it's not smooth, it's all beaten up and it's covered in snot. It's covered in living crap that's growing on it.

There's a fish called a Cling Fish that can stick to that, and it can stick to it with 300 times its body weight, and so we what to know how it sticks. The underlying skeleton for that disc is fascinating and shows you not just how it sticks but how it releases. Then you say, well, what's the use of that? Well, think about the inside of you. You got all sorts of irregularly shaped parts that are slick and covered with crap, and it would be kind of cool if we could open you up and use these suction cups inspired by fish to hold things up and move things from one place to another without grabbing on with, you know, rough pinchers and things which is the current state-of-the-art. So we used it to understand how that skeleton works.

I'm very interested in armor, how are you go through trade-offs of being really well armored and yet still be able to move, and so I've got a lot of CT scans of an armored group of fish called Poachers and we're trying to understand how that armor grows, how they start out as flexible little fish and turn into these little tanks. So those are couple of things that, you know, I use this in my own research.

CURWOOD: Adam, before you go, tell me how can other researchers get access to your digital images of these fish and what ways are they using them so far?

SUMMERS: So I think my favorite thing about this project is we make the data available free for anyone to use for any purpose immediately after we get it. So, we put it up on a something called MorphoSource and another site Open Science Framework, and you can go there and get the sliced data and you can do anything you want with it.

Adam Summers, also known as “the Fish Guy” (Photo: Adam Summers)

You want to make, uh, you wanted set up your own phylogenies and measure your own morphological characters? Absolutely, go for it. Do science. But if you're just a dad who wants to make a Christmas tree ornament for his kid out of their favorite fish, there you go. You could do that too. And if you're an entrepreneur who wants to make helmets that looked just like fish heads, go for it. The data is there. It's for you. So we make this available, open source, completely free for anyone to use. And I think that's one of the coolest things about it. It's inspiring all kinds of research and also other outreach things that we never would've thought.

CURWOOD: Adam Summers is a biology professor at the University of Washington. Thank you so much, Adam. Keep on taking those pictures.

SUMMERS: Thanks a lot, Steve. It was nice talking to you.

CURWOOD: And if you dive into our website LOE.org, you'll find some fishy pictures.

Related links:

- Chicago Tribune: “Washington scientist launches effort to digitize all fish”

- Adam Summers on Perfecting the Science in Pixar’s Finding Dory

- About Adam Summers, “The Fish Guy”

- OSF Project Information

[MUSIC: Thomas Newman, “Wow,” Soundtrack to Finding Nemo, Walt Disney Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. And we're happy to welcome Savannah Christiansen as an intern this week. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth