February 17, 2017

Air Date: February 17, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Pruitt and Conflicts of Interest

View the page for this story

Scott Pruitt, former Oklahoma attorney general and President Trump’s choice for Environmental Protection Agency Administrator has brought multiple lawsuits against the agency, some of which are still pending. Living On Earth Host Steve Curwood spoke with lawyer Paul Nolette, a Marquette University political science professor, about how Pruitt’s actions and previous business entanglements offer insight into his vision as head of the EPA. (10:00)

Catholic Call Against Corruption

View the page for this story

President Trump has signed the repeal of the Securities and Exchange Commission’s transparency rule that required extractive industries to reveal payments to foreign governments to prevent graft. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood spoke with Catholic Bishop Oscar Cantú, who’s visited developing countries to see how corruption fueled by foreign cash exacerbates poverty and misery. (03:10)

Coal Mines and the Stream Protection Rule

/ Reid FrazierView the page for this story

The new GOP controlled Congress acted quickly to overturn the Department of Interior’s new Stream Protection Rule. The Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports on how the rule might have affected coal mines and protected streams in Pennsylvania and the rest of Appalachia, had it survived. (04:30)

A Coal Miner’s Take on Stream Protection

View the page for this story

Coal has deep roots in Appalachia and its local communities, but this way of life too often comes with persistent water pollution. With the recent overturn of the Stream Protection Rule, coal companies are under less pressure to control and clean up their environmental impact. Former miner Gary Bentley and host Steve Curwood explore the murky future of coal country’s water and its future. (07:00)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood talk about the costs and benefits of a proposed Uranium mine to a small fishing community in Greenland, discuss environmental justice and the pig industry in North Carolina, and reflect on a famed Swedish chemist who was one of the first to calculate the global warming potential of CO2. (04:10)

Radiation Spikes At Fukishima

View the page for this story

Almost six years after a tsunami caused a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, the facility’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power (Tepco) faces overwhelming problems to clean up the site. Tepco now reports radiation in reactor 2 that would kill a worker in thirty seconds, and even destroys robots. Arjun Makhijani, the President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research and host Steve Curwood discuss the implications of this new report and the challenges of cleanup. (08:00)

Up-Close With Massive Elephant Seals

View the page for this story

Northern Elephant Seals, the size of SUVs, haul out on the beaches of Año Nuevo State Park in California by the thousands in February to give birth and mate. The park has set up a live webcam so anyone can tune in to see the drama, and host Steve Curwood called up State Park Interpreter Mike Merritt to watch and discuss the seals. (08:20)

An Elephant Seal Pup Nurses

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Elephant seal milk is high in calories, well-suited for feeding fast-growing pups in a short amount of time. Living on Earth’s Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender observes an Elephant Seal mother off the coast of Antarctica nurse her hungry pup, and finds the infant’s cries somehow familiar. (02:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Paul Nolette, Oscar Cantú, Gary Bentley, Arjun Makhijani, Mike Merritt

REPORTERS: Reid Frazier, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. President Trump’s choice to head the EPA, Scott Pruitt, has critics raising red flags about possible conflicts of interest and his suits against the agency.

NOLETTE: In his term as AG in Oklahoma, there were some real concerns that his actions were too closely aligned with the business interests that were contributing both to him directly as a candidate and to the Republican Attorneys General Association.

CURWOOD: Also, walking a California beach amid Elephant Seals the size of SUV,s as the females care for their new pups and fend off the amorous males.

MERRITT: Elephant Seals are known for their noises. The male really stands out, its a very low, guttural sound. I once had someone say it sounds like a Harley Davidson starting up in an empty garage.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Pruitt and Conflicts of Interest

U.S. EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Perhaps one of the most ironic choices President Trump has made for his cabinet is Scott Pruitt as EPA Administrator. As the Attorney General of Oklahoma, Mr. Pruitt led a group of Republican attorneys general opposing many EPA rules and regulations. Indeed he has sued the EPA more than a dozen times, and perhaps most famously led a group of states and companies in the continuing court fight against the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan. And, yes, the Clean Power Plan is a rule crafted by the agency Mr. Trump has asked Mr. Pruitt to take over, the EPA. To get a handle on Mr Pruitt’s political philosophy and potential conflicts of interest, we called Paul Nolette, a lawyer and political science professor at Marquette University, who joins us. Welcome to Living On Earth.

NOLETTE: Thanks for having me here.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, what was your reaction when you heard that Scott Pruitt was Trump's selection for the EPA?

NOLETTE: Well, I mean the first thing that I immediately thought was that it was quite ironic that you have somebody who really made his career as a state attorney general suing the EPA, now chosen to lead it.

CURWOOD: Yeah, in fact, the last time you were on our program you described some of these lawsuits that Pruitt had brought against the EPA as Attorney General of Oklahoma. Remind us again, what were some of those lawsuits?

NOLETTE: Yeah, some of his earliest lawsuits dealt with some of the regional haze rules, for instance. Many of these dealt with air pollution rules. Probably most famously he led an effort to challenge the Clean Power Plan. I think it's fair to say that virtually every environmental rule that came out of the EPA, at least any major role, Pruitt was involved in either as a lead plaintiff or signed onto a multistate lawsuit that other Republican AG's were bringing, and there were a total of, I think, about 14 lawsuits that Pruitt was involved in suing the federal government, suing the EPA.

CURWOOD: So, there are a number of matters that Mr. Pruitt sued the EPA about as the Attorney General of Oklahoma. As an Administrator of the EPA, when these matters come before him, what obligation does he have to recuse himself because of the conflict of interest?

NOLETTE: Yeah, in that case, it's really not entirely clear because, for one thing, it's not literally the case where he's suing himself as EPA Administrator, presumably somebody else will be Oklahoma’s state attorney general at that point - He's not going to be literally holding both roles - but in this case he does have a lot of discretion in the regulatory process and both in the process of implementation to avoid carrying out these Obama era rules. One thing that's actually getting some attention during the course of the confirmation hearings was Pruitt's action as Attorney General on a case that he inherited from Drew Edmondson, who was the Democratic AG of Oklahoma prior to Pruitt, and it involved a lawsuit against some poultry farms in Arkansas. Edmondson had been prosecuting the case pretty strongly, but once Pruitt came into office it sort of languished in the courts for quite some time, and actually it's been seven years that that case has been in court with no rulings because the Oklahoma AG Pruitt never filed briefs in the case, and it was an example of, I think, Pruitt inheriting a case he disagreed with and finding a way not to move the case forward. He'll have a lot of opportunities as Administer to do something similar.

The Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium in Washington, D.C. connects the two wings of the federal EPA office. (Photo: NCinDC, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, Scott Pruitt was chairman of the Republican Attorneys General Association, which has received I'm told, what, $4 million or nearly $4 million from fossil fuel related entities. Now, how do you think those kinds of ties to the fossil fuel industry affect his role at the EPA?

NOLETTE: It's going to be a big question, and I mean it's a legitimate conflict of interest here that I think Pruitt would do well to explain because in his term as AG in Oklahoma, there were some real concerns that his actions as AG were too closely aligned with the business interests that were contributing both to him directly as a candidate and to the Republician Attorneys General Association. And I mean, there was that blockbuster New York Times report back in 2014 which highlighted how in several cases Pruitt's complaints that he had been filing in some cases were actually written by industry lawyers, and so that raises the question about, well, I mean, a state Attorney General is supposed to represent the state's interests, not the interests of any particular group or industry.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, Oklahoma's a big fossil fuel state, a big oil and gas producing state. So, Mr. Pruitt could argue, well, he was really working for the benefit of the people of Oklahoma, a lot of jobs. The economy's based on it. How might that change when he's representing all of us in America at the Environmental Protection Agency?

NOLETTE: Yeah, well, for quite some time now Republicans and Democrats have had very different views on environmental policy and what the right balance ought to be struck between, say, economic growth and environmental protection. So, I think, from Pruitt's perspective, what I would anticipate him to say is I as EPA Administrator is, “Totally agree I need to carry out the rules dictated by Congress, however, during the Obama administration the EPA went well beyond what Congress authorized them to do, and that's why I sued them as, as Oklahoma AG. So, what I'm going to do as EPA administrator is pull back on those rules that went beyond Congressional intent.”

CURWOOD: Where do you expect Scott Pruitt to scale back on EPA regulations, as he's tried to do for much of his career?

Protestors at a rally in Mears Park in St. Paul, Minnesota. (Photo: Fibonacci Blue, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

NOLETTE: Pruitt will scale back on a number of things, including, for instance, new rules to scale back or end the Clean Power Plan if that does in fact pass court muster. In other areas dealing with water pollution, for instance, I would imagine that he's going to cut back on some of the rules of the Obama administration there as well, but at the same time, I don't know if it's going to be quite as drastic as some Republican saying, well, basically we should just get rid of the EPA together or slash its staff by two-thirds. I don't think you're going see something that drastic, but you're still going to see some, some real changes in policies that really adhere to Pruitt's view that the EPA was running wild and going beyond its statutory ability.

CURWOOD: So, how might the tenure of Scott Pruitt at the Environmental Protection Agency marginalize or enhance its operations and some of its important research, do you think?

NOLETTE: Well, I think one big thing that's going to happen is that a lot more of the responsibility for environmental protection will be put to the states. One thing that's really an open question, I think, is how much does he push back on states like New York and California and Massachusetts that want to have stricter environmental rules? Really, I can see that going one of two ways. One that he either says, kind of adheres to the Republican vision of environmental protection more limited in favor of economic growth and push back against that, or that he does take a robust federalist vision and say, “Hey, the Californias of the world, if they want to have strict environmental protection then that's fine with me as long as they don't try to impose it on states like Oklahoma.”

CURWOOD: In the Obama administration, you had a Democratic agency and a Republican Congress that was constantly asking the EPA administrator to come up and testify. Now, presumably you have a Republican agency and a Republican Congress. How will Scott Pruitt work with the Republican Congress, do you think, going forward?

NOLETTE: Well, it's going interesting because I can imagine that Scott Pruitt as EPA Administrator will in many ways ask Congress to actually limit the discretion of the EPA to act on a number of issues. So, for instance, after Massachusetts v. EPA, said to the EPA, “You do not have the ability to interpret the Clean Air Act in a way that prevents you from regulating greenhouse gases.” What you might see is Scott Pruitt calling for Congress to actually say the EPA can no longer regulate greenhouse gases. And so, actually in some ways taking away power from the agency that he leads.

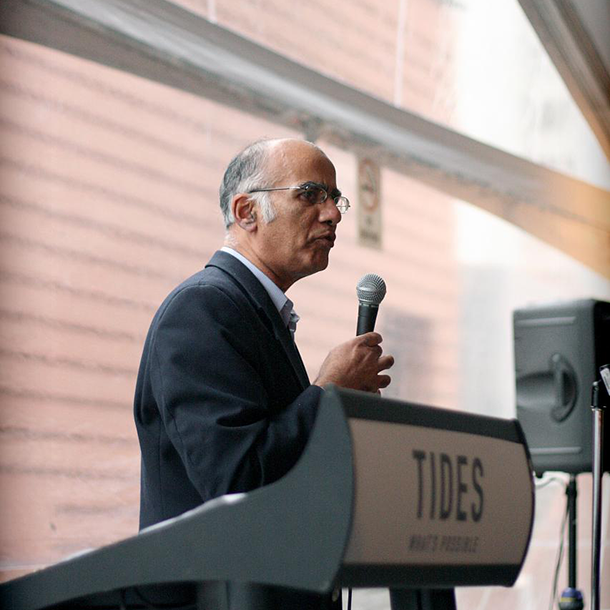

Paul Nolette is an associate professor of political science at Marquette University. (Photo: Marquette University)

CURWOOD: From your vantage point, how would you characterize his leadership style as an attorney general and how do you think that will translate into his new role with the EPA, going forward?

NOLETTE: He ran a state office in Oklahoma that you might think from the outset, oh, Oklahoma it it's not like California or New York or Texas, one of the really big states, but, nevertheless, I mean he was able to make the most out of relatively limited resources that he had in Oklahoma, hired excellent people and convinced them to pass up other jobs, maybe graduating even from Harvard Law school, and passing up other jobs and saying, “Come work for the Oklahoma AG's office because this is where the action is going to be during the Obama administration.” He's very smart, he's very detail-oriented and is also quite ideological. So, I do think that he's going to be more measured than say a President Trump is when it comes to talking about environmental deregulation.

CURWOOD: Value judgment before you go, Professor. The environment is going to be better off under the leadership of Mr. Pruitt or worst off, do you think?

NOLETTE: Well, the balance is definitely going to turn more towards economic growth versus environmental protection, I think. While I think states can take up some of the slack on some issues, when it comes to a lot of interstate issues -- And a lot of air pollution issues are interstate in nature -- or global issues like climate change, given Pruitt's emphasis on states taking up more the slack, it's going to be much more difficult to address these sorts of nationwide and global issues that the Obama administration made a priority.

CURWOOD: Paul Nolette is a lawyer and political scientist teaching at Marquette University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Professor.

NOLETTE: It was great talking with you.

Related links:

- Professor Paul Nolette bio

- Trump announced Scott Pruitt as his EPA pick in December

- Pruitt vote delayed by Senate Democrats’ concern over emails

- Paul Nolette on Republican AGs challenging environmental regulations in court

[MUSIC: NINA SIMONE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QH3Fx41Jpl4]

CURWOOD: Coming up, the human impact of some rolled back regulations. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fabian Beghin/Didier Laloy, “Frost Waltz,” Cryptonique, Homerecords]

Catholic Call Against Corruption

Some fear that the repeal of the Cardin-Luger Transparency Provision will mean less accountability for oil companies and other extractive industries operating around the world. (Photo: Global Panorama, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

It was hardly the Valentine that transparency and anti-graft lovers wanted, but on February 14th Donald Trump signed legislation to overturn a recent Securities and Exchange Commission rule requiring big oil, gas, and mining companies to report cash that they pay to foreign governments. The rule was written under the Dodd-Frank Financial Reform law and was scrapped through the rarely used Congressional Review Act.

Refining tin into tin powder in the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Photo: Fairphone, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

It‘s not only environmental and transparency groups that are outraged. So is the Catholic Church. Oscar Cantú, the Bishop of Las Cruces, New Mexico is chairman of the Committee on International Justice and Peace of the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, and it’s part of his job to visit developing countries to see what effect extractive industries have on local communities.

CANTÚ: One of the places that I went to visit was the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Congo is a very naturally rich country. And one of the issues, among many, is corruption in the local government at all levels. The difficulty there is that with these extractives, whether it's coal or whether it's diamonds or whether it's gold or whatever it may be, sadly it’s only the government and personalities that are benefiting from the richness of the land. So these local communities that are very rich in mineral resources don’t have paved roads. They don’t have basic access to clean water. So that is the difficulty with a lack of transparency.

CURWOOD: Bishop Cantú says his concern is not political, but moral. He says governments need to serve the people, especially the poor, and they are his main concern.

Bishop Oscar Cantú. (Photo: Roman Catholic Diocese of Las Cruces)

CANTÚ: I’m essentially a pastor. I’m much more comfortable preaching to my flock than sitting down in a boardroom with senators or representatives, but what gives me courage to do that is the faces of the people I meet who are suffering the ravages of poverty.

CURWOOD: According to the transparency advocacy group Global Witness, the U.S. already lags behind other major economies, such as Canada, Norway, and the European Union, in requiring rigorous transparency from extractive companies. Now this rule has been overturned, the SEC must craft another provision, but it can’t be “substantially similar to the previous one”. For Bishop Cantú, strong legislation is important to help protect the poor and vulnerable.

CANTU: I’m sure that this one particular legislation wouldn’t solve all of the issues but it is one piece because laws not only have a practical effect, but they also enshrine the values of society. And one is simply that those entrusted with authority in society be responsible to the people that they represent.

Related links:

- More information on the overturning the Cardin-Luger Transparency Provision

- A press release from the bishop on the repeal of the transparency provision

- Context and explanation of the Congressional Review Act

Coal Mines and the Stream Protection Rule

Veronica Coptis shows pictures of the reconstruction of Polen Run, a Greene County stream undermined by Consol Energy. (Photo: Reid Frazier)

CURWOOD: Meanwhile another Dodd-Frank rule is in the crosshairs, and that is the one about conflict minerals. That rule seeks to ensure that metals such as tin, tungsten, and gold, mined in the Congo and other African countries, don’t fuel even more conflict there.

Now, another rule undone by Congress was one of the last environmental shields created by the Obama administration, a regulation called the Stream Protection Rule. It would have made it harder for mining companies to bury or discharge mine waste into streams. But coal companies argued the rule would hurt their struggling industry, and Congress agreed. The Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier reports the rule could have had a big impact on coal mining in Pennsylvania.

Aerial view of mountaintop removal mining in West Virginia. (Photo: Natural Resources Defense Council, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FRAZIER: Up a trail in Greene County, Veronica Coptis walks a path she’s taken many times before.

COPTIS: It's really pristine. It's really relaxing. It's a beautiful place. It's even more gorgeous in the summer, I promise, it's more green.

FRAZIER: We are in Ryerson Station State Park, a few miles from the West Virginia border.

COPTIS: Right now we're above the 2L-1L section of the mine.

FRAZIER: That mine is Consol Energy’s Bailey complex, the largest producing underground mine in North America. Consol had planned to mine beneath Kent Run, the stream that runs through the park here, but Coptis, and her group the Center for Coalfield Justice, have helped stop that plan. The group, along with the Sierra Club, appealed Consol’s mining permit here. A state environmental hearing board judge sided with the environmentalists, and Consol announced 200 miners would be temporarily laid off because it can’t mine beneath Kent Run.

At issue is subsidence caused by mining, which could cause cracks in the streambed. When this happens, water can run into these cracks and dry up the stream. Between 2008 and 2013, 39 miles of streams in Pennsylvania suffered subsidence effects, according a state tally. Coptis said, she doesn’t want it to happen here in Kent Run.

COPTIS: We're trying to prevent any significant subsidence damage. So cracking in the stream bank, we're worried about loss of springs that are feeding the stream water.

FRAZIER: Consol and the state Department of Environmental Protection argued that the company would be able to fix the streambed by pouring cement in any cracks opened up, or, if that didn’t work, rebuilding the stream entirely. Coptis and other environmentalists were hoping they would soon get help from the federal government on issues like this.

The Department of Interior finalized the Stream Protection Rule in December, in one of the Obama administration’s final acts. But using a law called the Congressional Review Act, the new Congress quickly voted to take the new rule back. The Stream Protection rule would have tightened requirements for mining companies through more rigorous permitting, water monitoring, and stream restoration requirements, says Erin Savage of the environmental group Appalachian Voices.

Pine Box Trail in Ryerson Station State Park (Photo: Chris Collins, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

SAVAGE: In laymen’s terms, basically, they would need to assure the regulatory agency they’re not going to ruin water quality downstream.

FRAZIER: The rule was initially designed to address problems with mountaintop removal, a type of mining common in Central Appalachia which has buried over 1200 miles of rivers and streams.

SAVAGE: It was a moderate rule, it wasn’t some sort of drastic tree-hugger rule, it was updating an existing rule based on current science.

FRAZIER: But the mining industry hated the rule, and Republican-controlled Congress wasted little time dispatching it. Rachel Gleason, of the Pennsylvania Coal Alliance, said the rule was overly broad and could have been used to regulate underground mining like the kind commonly done in Pennsylvania.

GLEASON: They expanded it to areas that it should not be expanded to and said, it’s a one size fits all for entire nation. That does not work.

FRAZIER: Gleason said her group was worried that in Pennsylvania the stream protection rule would have restricted the ability of coal companies to mine beneath streams, and that would have made it virtually impossible for them to make money mining coal in Pennsylvania.

GLEASON: Given the hydrology and the makeup of Pennsylvania and the peaks and the valleys and the hills, it would be very difficult to do.

FRAZIER: A spokesman for Consol energy, in an email, called the Stream Protection rule quote an “ill-conceived concept”, and said the ideology behind it was rejected by voters in November.

The Center for Coalfield Justice’s case against Consol will be headed to a state appeals court.

I’m Reid Frazier.

CURWOOD: Reid reports for the public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- The story on the Allegheny Front website

- U.S. Department of Interior: Final Stream Protection Rule

- Ryerson Station State Park

- Journal article: “The environmental costs of mountaintop mining valley fill operations for aquatic ecosystems of the Central Appalachians”

A Coal Miner’s Take on Stream Protection

Gary Bentley is a former coal miner, mechanic and writer living in Lexington, Kentucky. (Photo: Gary Bentley)

So the coal companies say this stream protection regulation was unnecessary. But no one is nearer to this debate than the miners themselves, and, to get a view from closer to the coal seam, we called up Gary Bentley. He’s a former miner, now working as a writer and mechanic, and he joins us from Lexington, Kentucky.

Welcome to Living on Earth!

BENTLEY: Thank you for having me!

CURWOOD: And first, for the record, how long did you work in coal mining, and when did you leave the industry?

BENTLEY: I was an underground miner for 11 years in numerous mines across eastern Kentucky, mostly in Letcher and Knott County and then also in western Kentucky for one year.

CURWOOD: And, in your experience on the job, to what extent did you ever witness a chemical runoff or other pollution?

BENTLEY: I wouldn't say that I saw a large impact of pollution or runoff directly, but there were many events that happened around my hometown and around the region where there would be landslides that were created by the mining industry or containment ponds which were to hold pollution that would flood the streams and some of the areas where people lived. Of course you can just drive through the area and see the effects of surface mining.

CURWOOD: Gary, just briefly describe for us the surface mining operations and how they can cause a lot of contamination of local water systems.

BENTLEY: So, of course, when you go into the area, it has to be logged, the timber needs to be removed and then you have the strata - in layman's terms the rock and dirt - that covers the coal seam. Then holes are drilled and chemical explosives are used, and what that does is that separates the rock and the debris, the strata, that covers the coal system, so they can bring in the heavy equipment to load out the coal and much larger amounts than what we could do as underground miners.

Before miners can reach valuable coal stores, they log sites like this one in Redfox, KY and use controlled explosives to remove outer layers of rock and dirt. (Photo: Gary Bentley)

CURWOOD: Gary, tell me, when did you become aware that there was, well, a problem with water and a lot of stream contamination?

BENTLEY: Living in the region for 30 years, water contamination has always been a problem. We grew up with water contamination issues, not to discredit the trouble in Flint, Michigan, but when that news came out, I was like, “Oh, wow I've lived with these conditions all of my life,” and it was normal. We didn't think about it as in a life-threatening issue that it was, and it's very common in my hometown to have boil-water advisories for families multiple times in a month, sometimes multiple times in a week.

CURWOOD: How adequate did you think the Stream Protection Rule was as a plan for preventing pollution associated with coal?

BENTLEY: I'm a little bit torn on the rule as a person from Appalachia and as a coal miner. The rule really only affected new permits. Current mining operations weren't going be held to those same standards, but with a decline of the industry, I really don't see any new surface permits being issued or being requested at this time. So, I'm not too concerned about the immediate effects of this being repealed. What I am concerned about is the future effects when it comes to mind reclamation and then also, if there was a resurgence in the coal industry, the effects that it would have on us then.

CURWOOD: There are some folks who say the rules are what is killing the coal industry, and that it was good thing to repeal this water protection rule because it will protect jobs. Your perspective?

BENTLEY: I may not have the most popular perspective amongst people in those communities, but it's not that they're not concerned with the protection of their environment. You're talking to a group of people in a region that have never been offered an alternative to this industry. They've relied on a single economy for over 150 years, and so, when I go in and talk to these people and I explain to them, you know, this rule actually did not affect the industry. It didn't go into effect until January 19th of 2017. We were already losing these jobs back in 2008. And so when you start to talk about the market change in the industry, the ideas begin to change.

CURWOOD: At what point, did you become aware of the detrimental effects of coal mining, and particularly, the environmental effects, and then what prompted you to start speaking out about them?

BENTLEY: So, I've always been aware. I've always seen boom or bust cycles. There's always issues with our health - cancer rates, infant death, in the region, and we've always known it. I begin to speak out - I think it was round 2012 - I started seeing miners losing their jobs, coal companies pulling out of the region and not doing anything to support the communities when they left, and coincidentally it was also about three weeks after my first time speaking at an EPA hearing where I lost my job as a miner.

According to Bentley, mining jobs have been in sharp decline since 2008, well before the implementation of the Stream Protection Rule. Bentley himself was laid-off in 2012 along with 754 other miners. (Photo: Gary Bentley)

CURWOOD: Do you think there was any connection between those two?

BENTLEY: I feel that there was a very strong connection because within two days after I spoke, I received phone calls and had meetings with corporate officers, and then it was about a week or two after those meetings I was laid off with another 754 miners.

CURWOOD: There're some politicians out there that say that there is a war on coal. What your perspective?

BENTLEY: So, to say there's a war on coal, especially from a governmental standpoint, is ridiculous. It's just a change in markets. Natural gas is cheaper for energy. Actually, solar is now a cheaper form of energy.

CURWOOD: Gary, from your perspective, what should the federal government be doing to help folks in the coal fields of Kentucky and West Virginia?

BENTLEY: What they can do right now, is they can push through the Reclaim Act, which is a bipartisan bill to accelerate $1 billion from the Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fund. And, under the plan, $200 million would be distributed to participating states over a period of five years. We already have numerous support from Senators in West Virginia, Ohio, Virginia, and as a Kentuckian, I'm working alongside other Kentuckians to encourage support from the Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. The bill has been presented since February of 2016, and he has set it aside numerous times for well over a year now.

CURWOOD: What gives you hope these days? Coal is down, pollution is up. It's a time of difficult political ferment in this country.

Clements Fork in Eastern Kentucky runs through the heart of coal country. The Stream Protection Rule required mining companies to assess the quality of water systems like this one before digging and commit to its protection once they left. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BENTLEY: We are in a little bit of turmoil, but it seems as through people are coming together. We're going to see a lot more people gathering together, organizing. It may take a while, and it may be hard for a few years, but I do think we'll see a change in a more positive direction.

CURWOOD: Gary Bentley is a former miner and writer and mechanic in Lexington, Kentucky. Thanks so much, Gary, for taking this time with us today.

BENTLEY: Thank you.

NATIONAL MINING ASSOCIATION COMMENT ON THE STREAM RULE

For this story we also contacted the National Mining Association. Their written comment on the Stream Protections Rule is published below:

“The stream rule is to bad regulations what the Sistine Chapel is to Renaissance art. It’s a pure expression of all that ordinary Americans loathe about rule by bureaucracy.

It costs up to one third of current coal mining jobs, it’s redundant as it duplicates what states and other federal agencies are already doing, unnecessary since state reports to OSM show companies achieve reclamation with little off-site impact, unlawful as it flatly contradicts clear congressional intent in existing law (SMCRA)) and self-serving, allowing OSM to expand its authority at the expense of states and other federal agencies. This explains why Senate Democrats as well as Republicans agreed to a resolution of disapproval for this rule.”

Related links:

- Gary Bentley’s Op-Ed: “Coal communities will suffer because Congress repealed protections for water”

- Gary Bentley’s short stories on the life of a miner are published in Daily Yonder

- National Mining Association

[MUSIC: Travelin' Light, William-Sonoma Sunday Brunch 2000]

Beyond The Headlines

The view of the Greenlandic village of Narsaq from a boat. (Photo: Greenland Travel, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From Lexington Kentucky to Conyers Georgia, to meet up with Peter Dykstra now, and dive beyond the headlines. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn dot org, and DailyClimate dot org -- hi there Peter!

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. When we think about Greenland, we think about Vikings and a vast, ice-covered expanse where rising temperatures may be in the process of unleashing enough melting ice to wreak havoc with ocean levels worldwide.

CURWOOD: Yeah, well that would be the downside to making Greenland green again.

DYKSTRA: But there’s something else at play in Greenland. Huge, cold, barren, and beautiful, Greenland’s looking to modernize while addressing the unique social challenges of the Arctic, where alcoholism, depression, and suicide are widespread. And in the southern village of Narsaq, a fading fishing industry has locals tempted to welcome the foreign investors in one of the largest open-pit mines in the world for uranium and other rare metals prized in the electronics industry.

CURWOOD: Hmmmm, a struggling town pondering the lure of jobs from a huge mine. Kind of sounds familiar.

DYKSTRA: And this small town of sheepherders, native sealers, and a recently-closed seafood plant are tempted indeed. The mine complex would cover five square miles, much of it disposal areas for mining waste. Narsaq could be a boomtown for as much as forty years until the mine plays out, but its pristine setting and traditional ways could be sacrificed.

CURWOOD: Well, money can make people do all sorts of things. What else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: We’ve talked a lot about environmental justice, how poor and minority communities take a major hit from pollution, often with very little recourse. North Carolina’s sprawling hog farms are a prime example. And it’s no secret that Big Pig holds a lot of sway on the state’s government. Last month the federal EPA’s Civil Rights Office put the state on notice that it’s concerned about official discrimination against African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans who live near industrial hog waste facilities.

A factory hog farm in North Carolina. (Photo: Waterkeeper Alliance Inc, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And, to be clear, you’re talking about the same Federal EPA that’s clearly in the middle of a retreat from enforcing environmental laws?

DYKSTRA: And there are allegations that state regulators may have directly violated the law by tipping the hog industry off to what were supposed to be secret negotiations with the Feds, and by allowing folks who complained about odor and pollution from hog operations to be harassed. There’s further complication. While the 2016 election may have swung the Feds away from protecting the environment, a very close governor’s race in North Carolina, that a Democrat won, may push state regulators to take a harder line with hog waste and environmental justice. So like the situation in Greenland, it’s wait-and-see.

CURWOOD: Well I think in Carolina may be more like “wait-and-smell.” Let’s move on to the annals of environmental history now. What do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: February 19, 1859: Svante Arrhenius is born in Sweden. He came from a farming family and developed an affinity for botany and other ag sciences. His passion for science stretched to a whole range of studies in physics, chemistry and biology, as well as the links between the three fields, and in 1903 Aarhenius received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on conductivity and electrolytes.

CURWOOD: But we’re not remembering him today because of Gatorade, right?

DYKSTRA: No sir, we’re not. In 1896, Arrhenius published one of the first important works on what we now call “the greenhouse effect”. He studied the consequences of coal burning and the potential impact on temperatures in Europe and estimated that a doubling in atmospheric CO2 could raise temperatures by nearly ten degrees Fahrenheit. Current science confirms the rise but probably not by quite as much as that.

Svante Arrhenius was a Swedish chemist who published one of the first studies about the greenhouse effect. (Photo: Photogravure Meisenbach Riffarth & Co. Leipzig, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, but he wasn’t that far off either, and a hundred twenty one years-worth of evidence later, some people still want to argue about it.

DYKSTRA: That’s true. And finally, Steve, let’s clean up a little mess I made a couple of weeks ago. I mentioned what I called a “new” study describing lower-than-expected levels of tension between industry and state environmental regulators. Well, that study was actually based on a survey done in 2013, so it’s not exactly new. Thanks to one of our alert listeners for straightening me out.

CURWOOD: Thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- More on Greenland’s uranium mining dilemma

- Environmental injustice in North Carolina hog country

- Svante Arrhenius, Nobel Prize winner

- Arrhenius and his greenhouse study

[MUSIC: Oranj Symphonette, Baby Elephant Gunn (Baby Elephant Walk & Peter Gunn), Oranj Symphonette,Plays Mancini, Rykodisc 1996]

CURWOOD: The seal with a nose like an elephant. That’s ahead here on Living on Earth -- stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney, and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI. Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Derrane/Zan MacLeod, “Caprice,” on The Tie That Binds, Joe Derrane, Shanachie Records]

Radiation Spikes At Fukishima

Juan Carlos Lentijo of the International Atomic Energy Agency looks at tanks holding contaminated water and the Unit 4 and Unit 3 reactor buildings during a February 2015 tour of the tsunami-stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. (Photo: Susanna Loof / IAEA, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

Six years after an earthquake and resulting tsunami devastated Fukushima, Japan and led to the melt down of three nuclear power reactors there on the coast, radiation levels have reached a staggering 530 sieverts an hour, many times higher than any previous reading. Tepco, the plant’s operator, claims that radiation is not leaking outside reactor number two, site of these readings, but concedes there’s a hole in the grating beneath the vessel that contains melted radioactive fuel.

Joining us now to explain what it all means is Arjun Makhijani, President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. Welcome back to Living on Earth Arjun.

MAKHIJANI: Thank you, Steve. Glad to be back.

CURWOOD: So, this report from TEPCO seems serious, maybe even ominous. What what exactly is going on?

MAKHIJANI: Well, they are exploring the molten core of the reactor in reactor number two with robots, and the robot called Scorpion went farther into the bottom of the reactor in an area called “the pedestal” on which the reactor kind of sits and measured much higher levels of radiation than before. The highest level was 73 Sieverts per hour before and this time they measured a radiation level more than seven times higher. It doesn't mean it's going up. It just was in a new area of the molten core that had not been measured before.

CURWOOD: Still, it sounds to me like it's problematic, that six years after this meltdown there's such a high reading.

MAKHIJANI: It is a very high reading; they may encounter even higher readings. The difficulty with this high reading is that the prospect that workers can actually go there, even all suited up, becomes more and more remote. Robots are going to have to do all this work - That was mostly foreseen - but the radiation levels are so high that even robots cannot survive for very long. So now they're going to have to go back to the drawing board and redesign robots that can survive longer or figure out how to do the work faster, and it's going to be more costly and more complicated to decommission the site.

The lid of Unit 4’s Primary Containment Vessel lies close to the reactor building. The reactor was shut down for maintenance at the time of the accident. (Photo: Gill Tudor / IAEA, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Remind us, Arjun, please, of the human impact of this kind of radiation. What's toxic to humans?

MAKHIJANI: Right. So, if you get high levels of radiation in a short period of time, four Sieverts is a lethal dose for about half the people within two months. So, in 530 Sieverts per hour would give you a lethal dose in less than 30 seconds.

CURWOOD: Wow.

MAKHIJANI: So, it's a very, very, very high level of radiation. That's why people cannot go into the reactor and work there. That's not the end of the bad news, but that's quite a bit of it.

CURWOOD: OK. All right, there is more bad news. I'm sitting down. Tell me.

MAKHIJANI: Yes, so the bottom of the reactor under the reactor there is a grating and then under the grating there’s the concrete floor, and what this robot discovered -- It was supposed to go around the grating and survey the whole area, but it couldn't because a piece of the grating was deformed and broken. So, now it appears that some of the molten fuel may have gone through the grating and maybe onto the concrete floor. We don't know because even robotic surveys are now difficult, and a high radiation turns into heat, so the whole environment around the molten fuel is thermally very hot, and so whether it is going through the concrete, whether it is under the concrete, I don't know that we have a good grip on that issue.

CURWOOD: So, Arjun, what's going on with the reactors one and three? There have been published reports that TEPCO, Tokyo Electric Power Company that has these reactors, hasn't really taken a good look at those reactors. What do you know?

MAKHIJANI: Well, they have to develop the robots, and I think that developing them, by looking at reactor two, and they're finding these surprises, radiation levels much higher than previously measured. It shouldn't actually be unanticipated. The big surprise here was that a part of the grating was gone, and so that the molten fuel would possibly have gone through the grating. So, I think similar surprises will await reactors one and three because each meltdown will have a different geometry.

Storing contaminated water in tanks at the Fukushima Daiichi site presents an ongoing risk, says Makhijani. (Photo: Gill Tudor / IAEA, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, now what about the decay products here? We're starting with the Uranium family, but we wind up with Cesium and Strontium - Strontium 90. What risk is there of Strontium 90 getting into groundwater there?

MAKHIJANI: Yeah, so the peculiar thing about a nuclear reaction is the initial fuel, Uranium, is not very radioactive. It's radioactive but you can hold the uranium fuel pellets in your hand without getting a high dose of radiation. After it's gone through the nuclear reaction - Fission, that's what generates the energy - the fission products which result from splitting the Uranium atom are much more radioactive than Uranium, and Strontium 90 and Cesium 137 are two of the products that last for quite a long time, half-life 30 years, and are quite toxic. So, Strontium 90 is specially a problem when it comes in to contact with water. It's mobilized by water. It behaves like calcium, so if it gets into like sea water and get into the fish, the bones of the fish, or human beings, of course, it gets into the bone marrow and bone surface, increases the risk of cancer, leukemia. So it's a pretty nasty substance, and Strontium 90 has been contacted with water. You know, rainwater goes and contacts the molten fuel. Groundwater may be contacting the molten fuel. So, we have had Strontium 90 contamination and discharges into the ocean. They also collect the water. They've got about more than 1,000 tanks of contaminated water stored at the Fukushima site. By my rough estimate may be about 100 million gallons of contaminated water is being stored there.

CURWOOD: What happens if there's an earthquake?

MAKHIJANI: That's exactly right. So about a week into the accident, I sent a suggestion to the Japan Atomic Energy Commission that they should buy a supertanker, put the contaminated water into the supertanker, and send it off elsewhere for processing. They do have a site in the north of Japan which was supposed to be for plutonium separation, but it could be used to support the cleanup of Fukushima. But they rejected that proposal more than once and decided to build these tanks instead. They have a decontamination process on-site, and there are a very vast number of plastic bags on the site filled with contaminated soil. Nobody wants the stuff and nobody knows what's going to happen with it.

Arjun Makhijani is the President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. (Photo: Francisco Martinez/Tides Momentum, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's six years after the original meltdown. How much of a disaster is Fukushima today?

MAKHIJANI: Well, Fukushima is possibly the longest running, continuous industrial disaster in history. It has not stopped because the risks are still there. This is going to take decades to decommission the site, and then what is going to happen with all this highly radioactive waste, ‘specially the molten fuel? Nobody knows.

CURWOOD: Arjun Makhijani is President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. Thanks for taking time with us today, Arjun.

MAKHIJANI: So good to be back with you, Steve.

Related links:

- The Guardian: “Fukushima nuclear reactor radiation at highest level since 2011 meltdown”

- Washington Post: “Japanese nuclear plant just recorded an astronomical radiation level. Should we be worried?”

- TEPCO’s Decommissioning Plan for Fukushima Daiichi

- About Arjun Makhijani

[MUSIC: Geoff Bartley, “Lemonade Redux,” Blackbirds in the Pie, Joshua Omar’s Music/MCR]

Up-Close With Massive Elephant Seals

A male elephant seal trumpets among the crowd of beach dwellers (Photo: Mike Merritt)

CURWOOD: Now, February isn’t just the month for roses and candy for us humans, it’s also the month of new pups and hot-blooded males amid the sand and seaweed on some special beaches in California.

In Año Nuevo State Park, between Santa Cruz and San Francisco, thousands of Northern Elephant Seals return each year to give birth, breed, and molt their skin. Park Interpreter Mike Merritt works closely with them, and they’ve set up a webcam there so anyone can see these enormous animals close up, very personal and truly Living on Earth.

We tuned in for a look and called up Mike Merrit. Welcome to the program!

[ELEPHANT SEALS TRUMPETING CONTINUE THROUGH THE STORY]

MERRITT: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: So, we have your webcam going here, and for those of us who can't see what we're looking at, what are we looking at?

MERRITT: Well, we're looking at Northern Elephant seals. They are pinniped in the animal family, and they come to Año Nuevo State Park all throughout the year, mainly in the winter to breed, and our video here is showing us out on the beach, and you can see quite hundreds of animals here. There's big animals, those are the males. There's medium size, those are the females, and of course there are little black ones and those are the pups, just born this year.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about the noises that we're hearing.

In February, beaches like those at Año Nuevo are home to thousands of northern elephant seals (Photo: Amit Patel, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MERRITT: Yeah, elephant seals are kind of known for their noises. The male really stands out. It's a very low guttural sound. I once had somebody say it sounds like a Harley-Davidson starting up in an empty garage. And it can be heard miles away. It's really fantastic, and so every once in a while they'll belt out their noises. They're doing that to warn other males to stay away. Lots of communication between the males in that. We'll also hear the females.

CURWOOD: Wait a second. We see one of those big guys – male, I guess - climbing up on top of a smaller one, I guess a female, but she's not...

MERRITT: Yeah, he wanted to mate with her, but because he stopped, it meant something bigger scared him away. There's a lot of intimidation going on here on the beaches to the big males.

CURWOOD: So, my God, the noses on the front of these guys. I mean, they're humongous. Tell me about that.

MERRITT: They are. That's a sort of a sexual characteristic of the Elephant seals. It's kind of like guys with beards and things like that. Only the males have them, and that nose, the older they get, the bigger it gets. I've seen noses from large males that hang down like a Christmas stocking full, and of course, that's where they get their name from. It doesn't really do anything for them, except help show off how big they are.

CURWOOD: How big are they? Because they're not the size of elephants, they get their name from that proboscis, that nose hanging down like an elephant. But just how big are they?

MERRITT: Yeah, that's a good question. Well, they max out at about 5,000 pounds.

CURWOOD: Wait, did you say 5,000 pounds?

MERRITT: 5,000 pounds, yeah. I mean, they're there as long as an SUV and weigh as much.

CURWOOD: Oh, my. Now it looks like two of them just tried to synchronize their barking, grunting, what's that all about?

MERRITT: Yeah, again they are calling back to each other, and they use their voices, their vocalization to try and intimidate each other. Like this guy right here, they're trumpeting and they're trying to convince each other to back down, and if they don't back down they'll actually charge each other, and if they still don't settle back down they will fight, but sometimes, you can see he ran away. That's all it took.

A female elephant seal and her pup along the beaches of Año Nuevo (Photo: Mike Merritt)

CURWOOD: The littler guy is moving away here, huh?

MERRITT: If they do fight, they don't really fight to kill. That's not their prerogative. They're just fighting to intimidate and dominate. And it's kind of like a boxing match. They kind of like duke it out for a while, and someone backs down.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about this particular colony. How long have they been coming to Año Nuevo, do you think?

MERRITT: Well, that's a great question. So, we actually have an island here about a quarter mile away, and they first came there in the 1950s. They had been decimated as a population, and they had been slowly coming back, and our island offered refuge. There are no predators, no people there. So they colonized that, and they spilled over to our mainland, and today we have about 10,000 animals that come back to our park each year.

CURWOOD: What's their health as a species? I mean how endangered are they, if at all?

MERRITT: Well, they're actually not endangered, but they were an really epic conservation story. They were hunted for their blubber just like a whale. You can render oil out of these animals, and of course, in the 1800s, there was a big demand. They are estimated to have gone down to just about 100 animals. There was one island off the coast of Baja Mexico called Guadalupe Island, and it was the last refuge for Elephant seals. It's kind of remote, it's kind of out there. Luckily, Elephant Seals were migrating when hunters would appear, and so it just so happened that they thought they were extinct. In fact, three times they claimed this animal was extinct, but they weren't, and they survived. And soon, oil dropped in demand, we gave them protection, and from 100 animals we now have over 200,000 Northern Elephant Seals, and they're not endangered or threatened. They're thriving right now.

CURWOOD: So, they must be close cousins then, huh?

MERRITT: Well, there you go, yeah, so you asked their health. They are all healthy animals, but there is this kind of worry that, if they get sick, if there's a big disease comes through, it can really wipe them out because their genetic bottleneck is very small. It's going to take eons of generations to break that up.

CURWOOD: By the way, what do they eat?

MERRITT: Well, they are kind of deep ocean-bottom dwellers. They love squid, but they'll eat skates, rays. They actually eat small sharks. It's kind of ironic they eat small sharks and get eaten by big sharks - and they also eat a lot of microscopic animals that are along the ocean floor.

CURWOOD: So, ocean floor. What kind of diving ability do they have?

Although the elephant seal camera exists because Año Nuevo Island is off-limits to the general public, visitors to the state park are allowed to view elephant seals on the mainland through guided walks. (Photo: Mike Merritt)

MERRITT: Well, Steve, you really hit on one of the big things about these animals. They are diving machines. The Elephant Seals can dive over a mile deep, mainly the females, and they can hold their breath for up to two hours at the extreme. The males will dive along the Pacific coast up and along Aleutians of Alaska. They're vastly large migrators, too. These animals migrate twice a year, so they're going to the north Pacific and back twice, and the females actually just broke records. There was one female - Her actual name was Phyllis - and she swam beyond the international date line out on the Pacific which never been recorded before. So, they're still breaking records to this day.

CURWOOD: Wow. So, there's quite a few animals there. What do they do for food? There's a lot of chubby folks there. I imagine there's not that much food handy.

MERRITT: There is not. No. The only ones eating are the pups. They're the ones nursing with their mothers. But the rest of them, the males and the females and mothers, they are not eating. They're only living off their blubber, which is why, when a female shows up, she gives birth within five days, super quick, and then she feeds her pup for 28 days, and then she leaves. She doesn't teach the little guy how to swim or avoid sharks. She just gets out of here because she's hungry. She has to go back in the water.

CURWOOD: Wow. And so who takes care of the seal pups then, the guys?

MERRITT: No. There's no family structure here. There is a mother and a pup. The males really don't care about the pups. They could be rocks. They're in the way. The little guys, the pup, they get weaned. So, we actually call them “weaners” here, and these weaners will run around and kind of like find each other. They've all lost their mom, and they'll band together and then they'll slowly go into the water and they'll learn how to swim, and that migration instinct will kick in, and off they go into the Pacific to migrate and to feed. But, because no one's taught them anything, only 50 percent of this generation will return. The mortality rate the first couple of years is pretty high. But, if they can make it until four years old, they'll be pretty good the rest of the way.

Mike Merritt is a State Park Interpreter with Año Nuevo and works closely with the elephant seals who call this place home (Photo: Mike Merritt)

CURWOOD: Now, some of this noise, it looks like the pups are talking to each other there?

MERRITT: Yeah, we see some that are nursing with their mother. And, yeah, they have this kind of monkey-like cry. It also kind of pierces the air when you're near them. And that's them, always calling for milk or calling for mom. And actually, I heard a few years back they actually used the noises of the pups in the Lord of Rings movies for the orcs and goblins.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Oh, really.

MERRITT: So, you made have heard it before, yeah.

CURWOOD: Mike Merritt is an interpreter at Año Nuevo State Park. Mike, thanks for taking the time with us today.

MERRITT: Oh, it was my pleasure.

[CALLS OF ELEPHANT SEALS]

CURWOOD: And there's a link to the web cam at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Live Webcam of Año Nuevo Island

- Video for the webchat

- Sacramento Magazine: “Sex on the Beach”

- Año Nuevo state park video

An Elephant Seal Pup Nurses

An elephant seal pup (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: We stick with Elephant Seals but head to the far Southern Ocean and South Georgia Island with our resident explorer Mark Seth Lender. There he came across a breeding colony of these mighty creatures with many mothers and pups and found them both foreign and, somehow, familiar.

Elephant seal family (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Elephant Seal Pup Nursing

Godthal, South Georgia Island

© 2016 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: For the lifelong have-no-child-ers, the live-alon-er’s, the penultimate one-room-dwell-ers waiting for that Bell to Toll; for the married men with a man-cave in the cellar who’ve never ever changed a diaper - even for them - the sound of this Sounder is as Family and Familiar as a -

Come on over and bring the kid, the young’un, your new baby! Boy, she’s got a set a lungs, gonna sing the whole La, La Traviata a regular concertina you just wanna squeeze her we’ve got the Queen of – Everything – right here

The softer features -

The small pink tongue that cups at the edges -

Yes. You know. You right-off recognize the raspy waller of an unanswered caller who can and will just like that - Allllll day (until he gets his always, hungry, way).

The pup nurses (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Newborn Baby Elephant Seal raises a tireless commotion loud as the Soundings of the Southern Ocean. Baby’s Mamma? She just wants to sleep. Respite and relief don’t stand a chance against the Need that Will Not Keep. She gives in, and slides her wide webbed flipper off the teat that her own may take of rich, warm, drink.

Now before us all the stages, hauled out along the shoreline the quickly passing ages, parents and the young, the newborn and the old they will become. The needful and the needed, the suckling and the satisfaction that justifies -

All this.

To our surprise –

- We recall -

- We recognize -

(As the Flower Knows the Seed)

The babe all babies used to be.

Related links:

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Learn more about elephant seals on the National Geographic website

[MUSIC: Mrs Mills - Yes Sir, That's My Baby

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3FFmDVphq8M]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Kit Norton, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Thanks today to One Ocean Expeditions. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth