February 24, 2017

Air Date: February 24, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Standing Up for Science

/ Jaime Kaiser, Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Hundreds of scientists and supporters rallied in Boston’s Copley Square on February 19th, 2017, to affirm the importance of science, research, and factual reporting of results. Early moves by the Trump administration, including gag orders and travel restrictions from some countries, raise fears of political interference, data loss and censorship. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering and Jaime Kaiser report to host Steve Curwood on the mood at the rally, and the message from the square. (06:05)

Science Censorship Ended in Canada

View the page for this story

The new US administration quickly clamped down on scientific government agencies communicating via social media or with reporters. This type of government control is familiar to Canadian scientists who saw a similar crackdown under former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper that was later reversed by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. Host Steve Curwood asked Simon Fraser university biologist Wendy Palen what advice she has for her American colleagues. (09:00)

Greening the Military

View the page for this story

Deploying renewable energy helps the U.S. military function better, and saves the lives of soldiers, says Jim Goudreau, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy. He discusses with host Steve Curwood how green technologies such as solar 'blankets' and hybrid vehicles have improved operations within the Marine Corps and the Navy. ()

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood reflect on the settlement for health damage from chemical leak in Parkersburg, West Virginia, size up some chemical and agribusiness mega-mergers, and consider the effects of a Chinese ban on North Korea’s main export - coal. Then they remember how ignored warnings led to the deadly Buffalo Creek mining waste dam collapse 45 years ago that spurred legislation still in effect today. ()

BirdNote: Crossbills Nest in Winter

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

It may still be winter in parts of the US, but reporter Michael Stein explains that crossbills are already busy eating and nesting thanks to nutritious pine-cones. ()

Science Note: Yellow-Shafted Flickers See Red

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

The North American woodpeckers known as flickers have red feathers under their wings in the west, and yellow feathers in the north and east. But some birds in the eastern range have been turning up with red-colored feathers. Scientists thought they were somehow breeding with their red-shafted cousins, but have now discovered they’re actually just feeding on red berries from the invasive Asian honeysuckle. ()

“The Book That Changed America”

View the page for this story

The book that changed America is Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, says Randall Fuller, the Chapman Professor of English at the University of Tulsa. The book arrived in New England in 1860, as the slavery debate raged and civil war loomed, and its ideas were instantly fodder for those discussions. Randall Fuller explains the influence of Darwin’s new theories with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. ()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Wendy Palen, Jim Goudreau, Randall Fuller

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Scientists and supporters rally in Boston to protest the Trump administration’s perceived opposition to action on environmental defense and global warming.

PROTESTOR: I can’t believe that we’re having to protest in support of science! Are we going to have to protest next weekend in support of arithmetic?

HERMAN: Facts, we know, are facts. They can’t be changed by some kind of verbal jujitsu.

CURWOOD: Government hostility to science isn't new. In Canada, under Prime Minister Stephen Harper there were stark cuts in government funding and communication.

PALEN: There was a decline of about 80 percent in the research having to do with climate change after these rules went into place. It had a very -- what we call a chilling effect -- on our ability to study these problems with the environment as well as our ability to communicate about them.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies. Innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Standing Up for Science

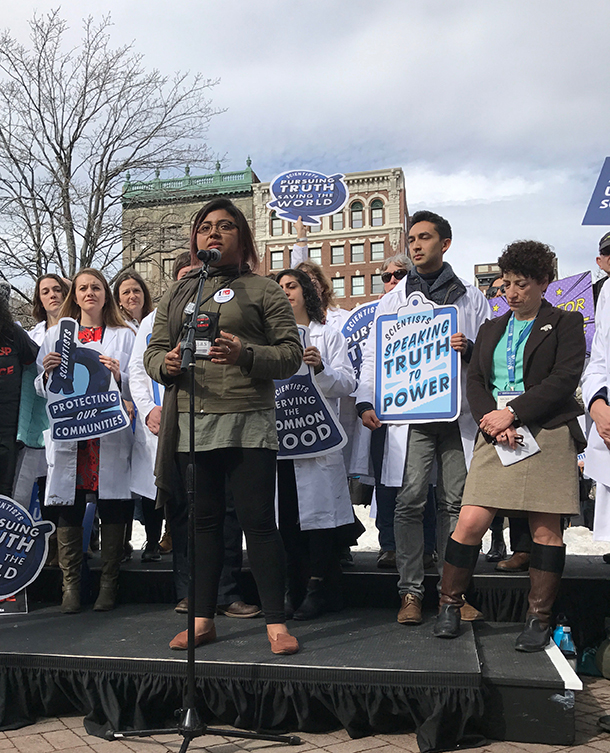

A group of scientists wearing lab coats lined the rally stage. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[CROWD CHANTING: STAND UP FOR SCIENCE! STAND UP FOR SCIENCE!]

ECONOMOPOULOS: We’re here because science serves the common good.

CURWOOD: In Boston’s Copley Square, barely a stone’s throw from where, two and a quarter centuries ago, American patriots came together to oppose repressive policies of the ruling regime, a new kind of opposition is taking shape. Hundreds of scientists crammed into the square – along with plenty of media – including Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering and Jaime Kaiser. Jenni, describe the scene.

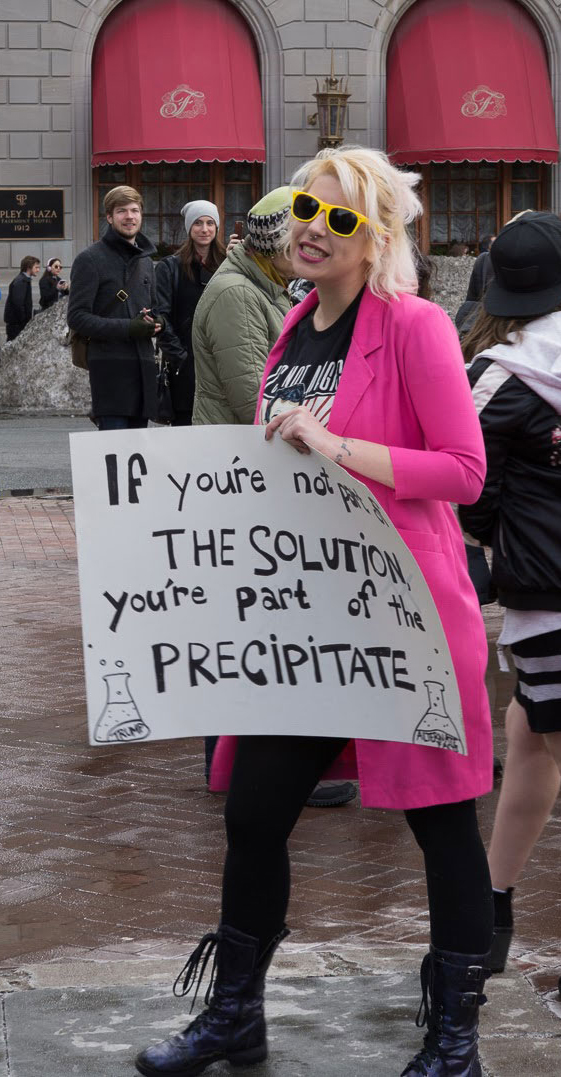

A crew of activists with their homemade signs. (Photo: Jaime Kaiser)

DOERING: Well, Steve, it was a crowd of several hundred, far smaller than the thousands that turned out for the Women’s March in Boston a month ago. But just like at that march, there were a lot of homemade signs, and families with kids, even some kids swimming in white lab coats that said “Future Scientist.”

GIRL: I’m one of those geeky kids. Science is part of my life and it’s just really important to everybody and obviously it does so much and it helps us discover so many things and explain so much and we can understand a lot about what our world is.

DOERING: She was there with her dad and two younger sisters. The middle sibling chimed in.

.jpg)

One protestor used an etching and a quote from the Spanish romantic painter Goya, and a play on President Trump’s campaign slogan “Make America Great Again,” to make a point about the importance of reason. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

YOUNGER GIRL: Like, our whole family are like, scientists. The kids are like mini-scientists.

CURWOOD: So it seems people at every stage of their scientific careers showed up, huh? What else did you notice?

DOERING: [FADE IN CHANTS] Well, there were familiar chants, of course...

DEMONSTRATORS: When science and research are under attack, what do we do? Stand up fight back! We’re here in alliance, standing up for science!

DOERING: And as you might expect of a rally of scientists, many of the signs were clever, and in some cases more interdisciplinary than you might think.

MAN: Well, it’s a Goya print, an etching in which a man is sleeping and monsters are in his dreams and it says, ‘The Sleep of reason produces monsters – Goya.’ And on the other side it says, ‘Facts, Logic, Reason, Empiricism: Make the Enlightenment Great Again.’

Two demonstrators commune at the entrance to Trinity Church in Copley Square. On the left, a woman wears a pink ‘pussyhat’ that echoes the many that were seen at the Women’s Marches all across the U.S. in late January. (Photo: Jarred Barber)

CURWOOD: So why did he call on Francisco Goya, the Spanish romantic painter?

DOERING: Well, it was personal, actually.

MAN: I’m a big Goya fan. I teach Gothic fiction at Boston College and I never thought we’d be living in a Gothic political climate. I can’t believe that we’re having to protest in support of science! Are we going to have to protest next weekend in support of arithmetic? Because it seems the Trump administration can’t get any of this right!

CURWOOD: So, Jaime, you were at the protest, too. What struck you about the demo?

KAISER: Steve, there was simply no avoiding the fact that the word “fact” came up again and again. It was brought up by many of the scheduled speakers, and it was evoked by others in the crowd. One man I spoke with used a telling quote from history to evoke their importance.

A demonstrator in a pink lab carried a chemistry-inspired sign. (Photo: Jarred Barber)

MAN: ‘Facts are stubborn things’ was what John Adams said in the Boston Massacre trial and that quote has echoed down through the ages. “Facts are stubborn things” and one of our founding fathers said so and this needs to be told to the Republican Party.

CURWOOD: Wow, a rally in support of facts! It seems, stranger than fiction.

KAISER: I thought so too. Robin Herman, a retired Dean at the Harvard School of Public Health, also had something to say about this.

HERMAN: Facts, we know, are facts. They can’t be changed by some kind of verbal jujitsu. And I was thinking this morning you know that phrase...

KAISER: She quoted a line from Lin-Manuel Miranda’s speech at the Tony Awards, just after the shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando.

HERMAN: ... love is love is love is love. And here we’re saying, facts are facts are facts are facts.

The crowd in the square was filled with scientists, families, citizens and students of all ages. (Photo: Jarred Barber)

KAISER: The event was organized to coincide with the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, AAAS.

CURWOOD: So, may I assume many of the conference attendees also rallied at Copley Square?

KAISER: Yes and no. Harvard Professor Naomi Oreskes, who spoke at the conference and at the rally, pointed out that some scientists just want to stick to science.

ORESKES: Some of you may have hesitated to come here today. I hesitated to come here today. We all have colleagues who didn’t come because they didn’t want to be political. So, I think it’s really crucial for us to be clear why we are here. We did not politicize our science. We did not start this fight. Our science has been politicized by people who are motivated to reject facts because those facts conflict with their worldview, their political beliefs or their economic self-interest. [CHEERING]

DOERING: But, Steve, the speakers in Copley Square weren’t just there for science. Yvette Arellano spoke about environmental justice and impacts on low-income communities of color.

ARELLANO: Know that science is the last line of defense between the interest and corporate greed of the industry that is oil, that is gas, that is chemical. You are the last line of defense we have! Know that you are real, live heroes.

DOERING: Some of those heroes were kept out of the United States by the Trump Administration’s original executive order restricting immigration from seven majority-Muslim countries. At least five scientists canceled their plans to come to the AAAS conference when the ban was briefly in place. And the AAAS leadership stated that the Executive Order would negatively affect not only students and scientists from banned countries, but also their colleagues in the US.

CURWOOD: Yes, there still seems to be a lot of uncertainty about how immigration policies from the Trump administration could affect the scientific community at home and abroad.

DOERING: That’s right, and while that uncertainty and fear did cast its shadow, on the whole, the people at the rally had a positive, fighting spirit.

Yvette Arellano of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (T.E.J.A.S.) used her speech to call out environmental injustice. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

[MUSIC PLAYED LIVE]

FUNKYTOWN MAN: Without optimism you just decline into despair. I mean, there’s only so much mourning one can do. We mourned a lot after the election and now just coming out and mobilizing, making a stand.

KAISER: And, Steve, you can take that man at his word. He, along with a few others, struck up an impromptu dance party as the rally was ending.

[MUSIC PLAYED LIVE: “She’s Blinded Me with Science” by Thomas Dolby.

CROWD SHOUTS AND CHEERS OF “SCIENCE! SCIENCE!”]

CURWOOD: [MUSIC PLAYING UNDER]: Thanks, Jaime and Jenni. That was Living on Earth’s Jaime Kaiser and Jenni Doering describing the scene at the recent Rally for Science in Boston, Massachusetts.

[MUSIC FADES OUT]

Related links:

- Stand Up For Science Facebook event page

- AAAS Annual Meeting Homepage

- A summary of Naomi Oreskes’ address to AAAS attendees

- More scientific signs from the rally

Science Censorship Ended in Canada

Beginning with the Death of Evidence march on Ottawa in 2012, the Canadian science advocacy group, Evidence for Democracy, continued organizing a series of “Stand up for Science” rallies in 2013 to protest Stephen Harper’s silencing of federal scientists. This one was held in Vancouver, British Columbia. (Photo: Chris Yakimov, Flickr CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, one of the issues that brought hundreds of scientists out on the streets in Boston was the call for science to speak freely. When President Trump took over the US government in January, staff at several government agencies were told not to send out news releases or communicate by social media, and most mention of climate change disappeared from some government websites. Changing the message on issues that could affect policy is standard operation with a change of administration, but many saw this as censorship of government scientists, akin to moves taken in Canada under now former Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Back in 2007, he restricted federal scientists from speaking to the media, particularly on environmental issues. Among the Canadian scientists reaching out in support of their counterparts in the US is Wendy Palen, biology professor at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, and chair of the group Evidence for Democracy. She joins us from near Vancouver. Welcome to Living on Earth.

PALEN: Thanks. It's a pleasure to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: First off, tell me what kind of research do you do?

PALEN: I work on water and the organisms that depend on water, so I study climate change, I study energy. I study where water is today, and where it's going to be tomorrow -- what the repercussions are for many different organisms that depend on water, including humans. One of the things that I'm working on right now is actually trying to provide a bit of a scientific synthesis or an overview of what we understand and what we don't understand about things like unconventional oil and gas materials in freshwater and marine ecosystems. So that's about the large uncertainties around our ability to plan for environmental contamination from unconventional oil and gas.

CURWOOD: Now understanding that you’ve done a fair amount of work on the impact of what happens when oil hits water. I imagine that you were the bull’s-eye went by Minister Steven Harper first began censoring federal scientists.

PALEN: It was certainly of concern to myself and many other of my colleagues. As an academic scientist, I am protected in a way that most federal scientists are not from political influence because I work at an institution of higher learning and higher education where my job is really about knowledge and discovery, but I was concerned about my federal science counterparts in politics.

CURWOOD: So, what was it like when former Prime Minister Stephen Harper first began censoring the federal scientists, and what else happened?

PALEN: You know, one of the challenges was actually finding out about that censorship and the stories came out in sort of bits and pieces from colleagues and it was hard to discern originally the effect of, you know, kind of any one manager requesting a scientist not going to a meeting or not speak to the media from a more pervasive issue that emerged which was that this was actually coming from very high within the government -- that censorship was happening across federal agencies, not just any one agency, and that scientists were routinely being denied permission to speak to the media -- being denied permission to speak about their research at conferences and that they felt like they would suffer repercussions if they spoke out about it.

CURWOOD: And what happened in terms of funding or access to research facilities at the same time?

During his time in office, former Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper prevented many federal scientists from speaking with the media and cut funding to many environmental research programs. (Photo: Remy Steinegger, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

PALEN: Yes, so around the same time what happened was a budget bill was passed that actually cut the funding to many different research institutions as well as locations where work was done, so fieldwork and research stations in the high Arctic as well as a place called the experimental lakes area that has sort of been the marquee example of where the government works with scientists to actually understand how contaminants and environmental pollution interacts in our ecosystem and what the human health consequences are of those kinds of pollutants, and that facility was ... their entire funding was slated to go to zero essentially, as was an Arctic research facility and several others. And there's sort of a systematic almost feeling to it -- that the kinds of facilities that were being closed or whose budgets were slashed were the kinds of organizations that were documenting changes in our environment, from atmospheric changes to water quality changes for human health to environmental and biodiversity changes.

CURWOOD: Which disciplines of science were the most affected do you think by this call for censorship by the Harper government.

PALEN: You know, it was initially our understanding was that it was primarily environmental scientists, but I mean that in a very broad definition. So, these are atmospheric scientists, environmental chemists, people who study snow, people who study water as well as people who study endangered wildlife or contaminants in the environment.

CURWOOD: And what effect did this have on research?

PALEN: What we know is that there was a decline of about 80 percent in the research having to do with climate change at least in terms of how it was communicated and published from those agencies after these rules went into play. So it was...it had a very, what we would call a chilling effect on our ability to study these problems with the environment as well as our ability to communicate about them.

CURWOOD: And to what extent did scientists speak out during this time?

PALEN: I think that's where we as a Canadian scientific community really came together was trying to create support for scientists to be able to speak out. So part of it was documenting the problem and seeing that it was actually quite systematic, and then the next step was really trying to create opportunities for those scientists to safely share their stories either anonymously or through their academic colleagues or scientific societies, and so that's where we really came together to speak out about the problems and most prominently so during what's called the Death Of Evidence rally in 2012 which was sort of a staged mock funeral on the stairs of Parliament in Ottawa where scientists came out and marched as a funeral procession holding up signs about the death of evidence and the way in which scientists were being censored and muzzled.

CURWOOD: How safe was the data they had gathered, and how much of it survived?

PALEN: You know, that's a pretty hard question to answer. We know that there are some cases where datasets were actually literally thrown into dumpsters. There were libraries that were closed, research libraries at different facilities where we know that some of the older documents that were in those libraries were never digitized, and so they predated the electronic forms of communication, and so some of that is lost forever. It's a little bit hard to even imagine the value of those documents, but in other cases where there were electronic copies. Things were well protected.

CURWOOD: What's the biggest thing that you notice now that Prime Minister Trudeau has taken over compared to what life was like during the Harper years?

Wendy Palen is an associate professor of Biology at Simon Fraser University and board chair of Evidence for Democracy. (Photo: Wendy Palen)

PALEN: I think what I notice is that there is a lot of vocal support for the role of science and evidence in decision-making, and I think that there's a lot of genuine interest in protecting scientists as a group with people who are tasked with expanding our knowledge and science by itself is completely apolitical. Facts are apolitical. And so recognition by government is a very important thing and that serves to reassure those of us in scientific community.

CURWOOD: What advice do you have for scientists in the United States who are facing similar restrictions? The Trump administration has issued gag orders for scientific agencies, including the EPA.

PALEN: You know, the lessons we learned in Canada are very relevant to the United States right now, and there's a couple of key messages that I would have for scientists in the US. One is that you need to find ways to document the abuses or cases where there's unethical behavior happening within agencies or scientists being individually censored or told that they need to change something in a report or that they can't speak to the media, but the broader message is about coming together as a scientific community. So those of us that are in relatively safe and protected positions need to really stand up for our colleagues who are more vulnerable, and right now I think those are the colleagues that are in federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency or the Department of Energy.

CURWOOD: Typically scientists, they want to work in the lab and on their data, aren't much interested in politics, and yet you seem to suggest that's also part of the job, that people need to look at what's going on in the society around them if they're scientists.

PALEN: Yeah, I do. I agree with you. I think that a lot of my colleagues as scientists are much more comfortable putting their nose to the microscope, working on these really important problems that they and a close community of colleagues really understand, and that it is harder to stand up and actually speak as a group and to speak out publicly, and I think what we learned in Canada is that there's incredible value in doing that because what it does is it potentially engages the public in these issues that they deserve to know about, and if every scientist kept quiet, kept their nose down, we would never hear about this. And so there is a really important role for scientists to speak up for the integrity of the process of science when it's being threatened.

CURWOOD: Wendy Palen is Associate Professor of Biology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. Wendy, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PALEN: You bet. Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Wendy Palen’s Op-Ed article in the New York Times

- The Palen Lab website

- Evidence for Democracy’s homepage

- Living on Earth March 8, 2013: Canadian Government Gag Order For Scientists?

- The Atlantic’s look back on Canada’s political fight over science

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Sinister Minister,” on Flight of the Cosmic Hippo, Warner Brothers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vPT3CGe4FS0]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the American military embraces renewable power. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: “Mele H’bibi” on Kenza, arr. Steve Hillage, Ark21 Records]

Greening the Military

On a combat outpost in Afghanistan in November 2012, two corporals in the U.S. Marine Corps installed solar panels to provide power to radios, laptops, and computers. (Photo: Lance Cpl. Alexander Quiles / U.S. Marine Corps, CC government work)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. For the US military, climate change poses a national security threat. So they are already adapting to global warming in ways to add strength to American fighting forces. That’s the view of Captain Jim Goudreau, a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy, who spent over two decades in the supply corps and is now the Head of Climate at Novartis. Jim, welcome to Living on Earth.

GOUDREAU: Thank you very much, Steve. Pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So, first, brief us on why climate change has such an impact on national security.

GOUDREAU: Climate change itself may not create conflict. It may not create wars, but it's a threat multiplier that changes conditions that will lead to greater chances of physical conflict and certainly will lead to tension over resource scarcity.

CURWOOD: One need only think of Syria, I guess.

GOUDREAU: Absolutely. People that had been on the same land for generations weren't able to raise the crops they had been. They moved off that land into the city, an urban area which was already stressed for water, which was already incredibly dense from a population perspective and then put greater pressure into that existing ecosystem. Unfortunately, given competition for resources and if that becomes an issue for your survival, that becomes conflict, and all too frequently the US is involved in trying to help mediate that conflict or resolve that conflict, and so it changes where we operate and what conditions are.

Solar panels on a U.S. Marine Corps Expeditionary Forward Operating Base (ExFOB) in Morocco. (Photo: ZeroBase Energy, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Your background is in the supply corps. You’re someone who handles logistics. Tell me, what did that entail and how did that relate to energy efficiency and its relationship to climate?

GOUDREAU: At one point during my career, I handled the logistics support for all of the amphibious fleet for the US Navy in the 7th Fleet area. So, in practical terms that's from Hawaii to Pakistan and from Vladivostok down to the Antarctic. Trying to move fuel to all of those ships and all those Marines in a theater that large is incredibly complex. If everything goes perfectly well, it's a tough day to make things happen on schedule. If the slightest thing goes wrong then you miss replenishments. It impacts ship schedules, it impacts your ability to respond to natural disasters, to regional flare-ups -- and that really informed my concern on how can we perform better, how can we leverage the scarce resources in that type of environment and be better at the job that our nation charges us to do every day.

The US military burns over 1.25 billion gallons of fuel a year. The Department of Defense is the single largest consumer of fossil fuels in the US, and when you talk climate issues you can talk mitigation or adaptation. Every single gallon of fuel that we burn is carbon going into the atmosphere. That has an impact on the climate. That impact on the climate then drives operational tempo as we respond to more disasters as a result of weather events, as we respond to regional insecurity and instability which then, of course, drives greater fuel consumption, putting more carbon into the atmosphere. It just feeds into itself. And at some point, we've got to break that, and we've got to break our dependency on fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the Marine Corps Experimental Forward Operating Base demonstrations where you integrated renewables for what were -- I think -- three units involved in this.

An example of a portable solar recharging system used by the U.S. military, called REPPS, or the Rucksack Enhanced Portable Power System—or simply, ‘solar blanket.’. (Photo: U.S. Army CERDEC, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GOUDREAU: Absolutely. A couple years ago, the Marine Corps did a study, and for every 50 fuel convoys that moved in theater, they had a casualty -- either wounded or killed. So, the Marine Corps tests gear in real circumstances with real Marines to see what can be used by them to drop their energy consumption, to reduce what has to be moved to them in the logistics convoys and to change, essentially, how they consume energy in the battle space. Those efforts led to equipment that was deployed in Afghanistan starting in 2010, and on two of their forward operating bases, the Marine Corps was able to completely reduce the need for fuel resupply. They took solar units, and they hooked up their computers, their radios, their artillery targeting software, all to solar arrays that had battery storage, and they were able to fight the fight on a daily basis without moving liquid fuel in. They also did that in another location and were able to reduce their fuel requirements by over 90 percent. In real terms, that means a young Marine didn't have to go into harm's way simply to move fuel to that forward operating base.

CURWOOD: So, what have you seen in terms of how renewables can improve operations?

GOUDREAU: Renewables themselves give, in the Marine Corps’ case, greater agility, greater speed, greater self-sufficiency. Marines don't really focus on environmental issues. They need to be lethal, and if you can tell a Marine that I'm going to give you gear that gives you a better chance of winning the battle and coming home, then they're all for it. An infantry Marine will carry about 120 pounds in their pack today when they go out on patrol. The Marine Corps in 2010 sent out flexible solar blankets, small blankets you could roll up, and rechargeable batteries for the equipment that they had in their pack and that they would use for the combat gear. And instead of putting 25 to 30 pounds of batteries into their pack, they were able use rechargeable batteries and solar blankets to execute their mission, which means as a young marine you're either lighter and faster and more agile, or you can put more ammunition into that pack and be more lethal during that mission, and give yourself a greater chance of coming home alive.

CURWOOD: And describe a solar blanket for me, would you please?

GOUDREAU: If you were to take a piece of canvas maybe two feet by two feet and put a very thin flexible solar cell onto it, you can just roll that up and put it into your backpack. Or you can clip it onto the outside of your backpack and as you're walking along, you’re getting a charge from the sun. When you stop, you can lay that out and connect batteries and recharge those batteries.

Jim Goudreau is a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy. (Photo: Jim Goudreau)

CURWOOD: Broadening that out now to the Pentagon's operations across our fighting forces -- how efficiently is our military working now, from an energy standpoint?

GOUDREAU: I think our military is more efficient now than they have been before, even though consumption has gone up. One thing to understand is that the equipment that we are bringing to the fleet and bringing to the Marine Corps consumes more energy because we have more computers, more electronics, greater requirements from that equipment as they operate in a networked combat environment, but they are more effective, the Marine Corps recognizing that the enemy knows that we need fuel and if they can interrupt that supply then that gives them an advantage. Being able to install things like variable speed motors, pumps and drives, hybrid electric drives on board destroyers and to incentivize different behaviors on board a ship are moving the Navy to where they can stay on station longer, and they can be more capable war fighters.

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent do you anticipate that the incoming Trump administration and the Secretary of Defense General Jim Mattis will embrace this approach?

GOUDREAU: Well, I certainly think that Secretary Mattis will do so. He, while he was in charge of theater in central command, made a very strong push with his troops to focus on operational energy -- to understand what they were consuming, what benefit they got operationally from it, and to try to reduce vulnerabilities by using less fuel. He understands the operational vulnerabilities that exist because of the fuel that we use, and I feel that he's going continue to look at developing the capability that can make our Marines more agile and more lethal. He's a tremendously well-read and serious member of the profession of arms. He understands what's happened with forces in the past who have had energy challenges, and I think he'll be determined to prevent that from happening in the future.

CURWOOD: By the way, Jim, before you go, a number of government scientists feel that they are under assault by the incoming administration. How important is science to the military?

GOUDREAU: It's incredibly important. It's the foundation for our capability. It serves as a foundation for forecasting into the future. Just simply technology development. Nuclear propulsion...we wouldn't have the fleet and the capabilities that we have today if the government had not made significant investments in basic science, basic research and development and then applied science and research and development. If we didn't invest in satellites, we wouldn't have the weather forecasting technology that we have today that's critical to safe operations at sea. We wouldn't have GPS, which is critical to operations all over the globe for the US military. So I would say that it serves as the foundation for our capability and will continue to serve as the foundation and absolute requirement for our continued operations.

CURWOOD: Jim Goudreau is a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Navy and now Head of Climate at Novartis. Captain Goudreau, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

GOUDREAU: Thank you so much, Steve.

Related links:

- Utility Dive: “Will Trump disrupt the US military’s clean energy mission?”

- Jim Goudreau’s “About” page on the U.S. Navy’s Green Fleet website

- About the USS Makin Island hybrid Navy amphibious assault vessel

- The Marine Corps Expeditionary Energy Office (formerly ExFOB)

[MUSIC: Khaled, “Melha” on Kenza, arr. Ahmed Hamadi/Khaled, Ark21 Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A power plant generates energy for North Korea’s capital, Pyongyang. The authoritarian country’s biggest trading partner, China, has just cut off all coal imports through the end of 2017. (Photo: Clay Gilliand, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time to check in with Peter Dykstra of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and the world beyond the headlines. He’s on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. One of the world’s largest chemical manufacturers just recently settled a massive, sixteen-year-old lawsuit in Federal Court. DuPont manufactured perfluorooctanoic acid -- it’s usually known as PFOA -- at a plant in Parkersburg, West Virginia. PFOA is key to manufacturing one of DuPont’s marquee consumer products, Teflon. This chemical leaked into water supplies near the plant, local residents sued, saying PFOA, which EPA lists as a likely carcinogen, is responsible for various illnesses and birth defects.

CURWOOD: And the EPA also got DuPont and other manufacturers to stop using PFOA several years ago, right? So what kind of money are we talking about in this settlement?

DYKSTRA: $671 million dollars, to be split among thousands of plaintiffs, and, of course, a boatload of lawyers. DuPont’s stock actually went up after the settlement was announced, because some experts thought they’d be paying out more like a billion dollars.

CURWOOD: So the people with health problems they link to PFOA aren’t likely to be seeing much in terms of compensation I guess…And DuPont execs are looking at a rather eventful year on other fronts, I think.

DYKSTRA: Yes they are. This settlement has cleared the decks for a chemical mega-merger with their longtime rivals, Dow Chemical. The $130 billion deal is expected to be completed later this year. But wait --- there’s more! German-based Bayer is seeking approval to take over US-Based Monsanto to the tune of $66 billion this year also. And the EU is expected to rule on another giant takeover in April – a $43 billion deal between ChemChina and Syngenta.

CURWOOD: So the global giants of chemicals and pesticides are poised to grow even bigger huh? What else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, if you want an example of how a pretty straightforward energy issue can become a major global security issue, look no farther than North Korea.

CURWOOD: Oh, North Korea, what could possibly go wrong there?

Strip-mining can wreak havoc on natural environments, like this site in Southern Ohio. In 1972 a strip-mining waste dam collapse caused the death of 125 people. (Photo: Larry Wfu, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, they’ve been busy lately -- a little saber rattling about nuclear weapons, and of course the apparent murder of Kim Jung Un’s half-brother. And when North Korea acts up, its economic lifeline, China, sometimes acts too. China announced they’re cutting off all North Korean coal imports through the end of the year -- probably the single biggest source of currency for the perpetually cash-starved nation.

CURWOOD: But aren’t there concerns that a country with an unstable leader might do something regrettable in response?

DYKSTRA: Well let’s leave the United States out of this. But North Korea -- developing nukes and missiles to deliver them, and constantly threatening to unleash its conventional artillery on South Korea, is entirely unpredictable. China’s decision to put North Korea in coal time-out could be the key to toppling North Korea, or it could result in something very, very bad.

So let’s move from North Korean coal to domestic U.S. coal for our history item -- in fact, back to West Virginia.

CURWOOD: OK, sounds good, what do you have?

DYKSTRA: Well, Pearl Woodrum was a resident of Saunders, West Virginia, a small coal mining town in the southern part of the state. In the late 60s and early 70s, she repeatedly contacted the state government, concerned that a mining waste dump uphill from her town was unsafe.

CURWOOD: Now mining waste is different from the coal-ash dumps we’ve heard so much about in recent years, right?

DYKSTRA: That’s correct. Mining waste, or coal slag, is the toxic mess left behind from the actual extraction of coal. Coal ash is the toxic mess left behind when that coal is burned in a power plant or factory.

After three rain-soaked days, on the night of February 26, 1972 -- forty-five years ago this week -- heavy rains forced coal waste dams to collapse, burying Saunders and three other small towns. Pearl Woodrum survived, but 125 other people died.

CURWOOD: Now this was in the era of strip mining. Were there any meaningful reforms?

DYKSTRA: Five years after what became known as the Buffalo Creek disaster, Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977, putting the clamps on strip-mining.

CURWOOD: So today we have mountaintop removal instead, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yeah we do. It’s a ruthlessly efficient and destructive method that needs far fewer miners to execute, sacrificing both jobs and mountains throughout Appalachia.

Residents of Parkersburg, West Virginia have sued the energy company DuPont after it accidently leaked perfluorooctanoic acid into local water supplies. (Photo: Paul Sableman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And burying valleys and streams with waste, as well. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks Peter, we’ll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Ok Steve thanks, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stores at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Reuters: “DuPont settles lawsuit over leak of chemical used to make Teflon”

- Market Watch: “Investors heartened by Trump’s apparent support of a Bayer-Monsanto merger”

- Reuters: “EU regulators delay ChemChina/Syngenta merger decision to April 12”

- NYTimes: “China Suspends All Coal Imports From North Korea”

- The Buffalo Creek Flood and Disaster: Official Report

BirdNote: Crossbills Nest in Winter

A red crossbill. (Photo: Skinnbrager)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: There’s still snow on the ground in places in America -- but the days are getting longer. And as Michael Stein points out in today’s BirdNote, some species are already busy with the tasks of spring.

http://birdnote.org/show/crossbills-nest-winter

BirdNote®

Crossbill Audacity - Crossbills Nest in Winter

[White-winged Crossbill call]

STEIN: From the tip-top of a black spruce, a White-winged Crossbill sings a rapid-fire tribute to winter. He’s got a good reason to sing. Even in the cold, crossbills are nesting.

Among virtually all our songbirds, the breeding season begins with the longer, warmer days of spring — and the seasonal bounty of insects, fruits and seeds. But for crossbills … it’s all about the food. When the evergreens hang heavy with snow and cones, crossbills can get all the calories they need for the demands of reproduction: courtship, egg-laying, and feeding young.

North America’s two crossbill species, White-winged and Red, are vagabonds, wandering in flocks until they find a suitable cone crop, where they might then stop to breed in small groups … almost any time of year.

[Red Crossbill call]

Crossbills are finches, and yes, their bills do cross at the tip — an oddity that helps them pry and extract seeds from those nutritious cones of spruce, fir, pine, and tamarack.

[White-winged Crossbill call]

So even in the grips of winter, when most songbirds are months away from the breeding season, somewhere among the snowy conifers, crossbills are already warming up!

I’m Michael Stein.

###

The white-winged crossbill. (Photo: Zak Pohlen)

Written by Bryan Pfeiffer

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. 133361 and 133363 recorded by Geoffrey A. Keller. 138310 recorded by Gregory F. Budney and Matthew A Young.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org February 2017 Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/crossbills-nest-winter

CURWOOD: To catch a glimpse of these birds, go to our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Listen on the BirdNote Website

- Audobon: “How Crossbills and Other Birds Are Re-writing the Rules of Evolution

[MUSIC: Gerardo Nunez, “Isa” on Colors of the World (originally released on Jucal from Alula Records), Allegro Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how birds of a feather can have different colors. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies -- combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI. Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gerardo Nunez, “Isa” on Colors of the World (originally released on Jucal from Alula Records), Allegro Records]

Science Note: Yellow-Shafted Flickers See Red

Photo: A yellow-shafted flicker with red feathers. (Photo: Chris Hansen; courtesy of Rebecca Heisman, American Ornithological Society)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In a minute -- how Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution fanned the flames of America’s civil war, but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: Northern flickers, medium-sized North American woodpeckers, come in two varieties -- red shafted in the west, and in the east and north yellow-shafted. The two names relate to the color of the feathers under their wings. But since the red and yellow flickers interbreed where their ranges meet, there are some birds with a salmon-pink blend of both colors.

For several years, ornithologists have documented some flickers in the east sporting red-orange wing feathers, and assumed that was due to interbreeding. But some of the yellow-shafted flickers with red feathers were thousands of miles east of the nearest red-shafted flickers.

Now scientists from the Royal Alberta Museum in Canada have solved the mystery. The red color in yellow-shafted flickers’ feathers is actually due to the birds eating red berries from invasive Asian honeysuckles. Using sophisticated optical laboratory techniques the scientists determined that a pigment in the berries called rhodoxanthin causes the red color in the eastern birds’ feathers, while it’s carotenoid pigments that make the western flickers’ feathers red.

Scientists think the berries also turn the tips of tail feathers of another bird species, the cedar waxwing, orange, instead of their normal yellow color.

This change in flicker feather color isn’t just an interesting curiosity. Scientists hypothesize that this new color variation could affect mate selection if the flickers can no longer rely on normal plumage color to signal a prospective mate’s body condition and fitness.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Audubon: “Mystery Solved: Invasive Berries to Blame for Turning Flickers’ Feathers Pink”

- The journal article: “Diet explains red flight feathers in Yellow-shafted Flickers in eastern North America”

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds: Northern Flicker

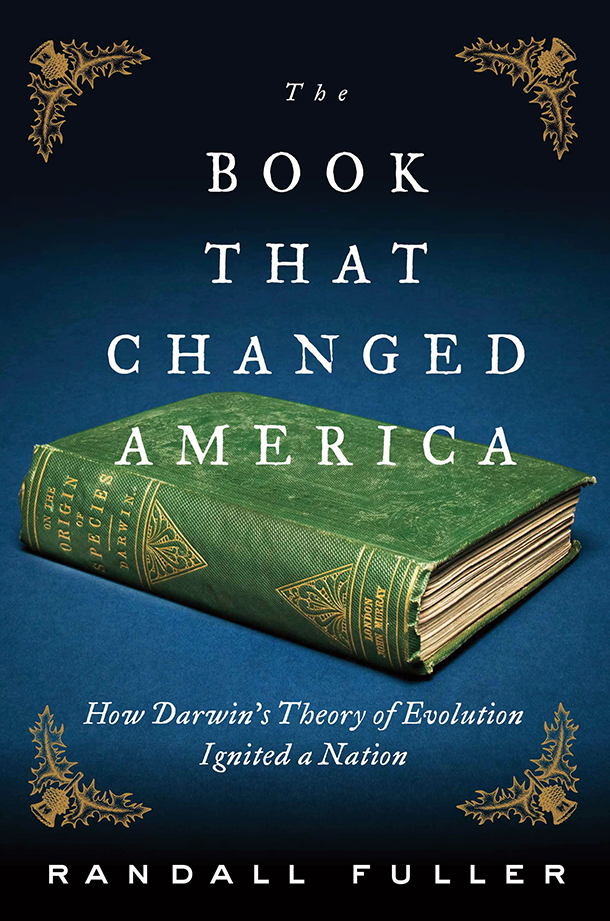

“The Book That Changed America”

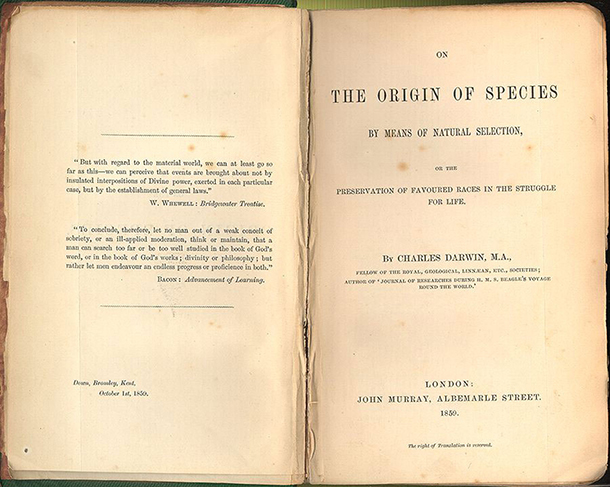

The Book That Changed America: How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Ignited a Nation (Photo: Randall Fuller)

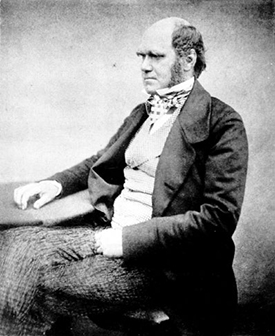

CURWOOD: “On the Origin of Species” by Charles Darwin was “The Book That Changed America” according to Randall Fuller. Professor Fuller writes how Darwin’s book came out in 1859, as the debate about slavery raged and civil war loomed, and how its revolutionary thesis challenged, excited, confirmed or infuriated the intellectual elite. Randall Fuller teaches English at the University of Tulsa, and he laid out his argument for Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: So Randall Fuller, you subtitle your book, “How Darwin’s Theory of Evolution Ignited a Nation”. When “On the Origin of Species” arrived in the New England, the slavery debate was already pretty red-hot. How did Darwin’s theories play into that debate?

FULLER: Well, you're right. The divisiveness over slavery was already bubbling over as a result of the John Brown affair, but what Darwin's book did was enter a cultural moment where questions of competition between regions and especially the relative status of black people versus white people was incredibly heated and contentious, and so, what Darwin did essentially was bring to an already very fractious and volatile moment a new take on an old discussion about racial ideology and slavery.

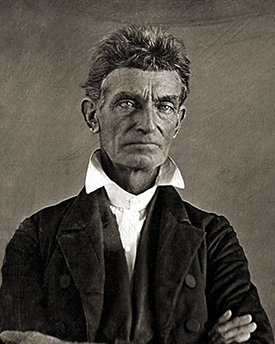

PALMER: Now you mention the John Brown affair. Can you tell me exactly what that was?

Daguerrotype of Henry David Thoreau in June 1856. (Photo: Benjamin D. Maxham, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

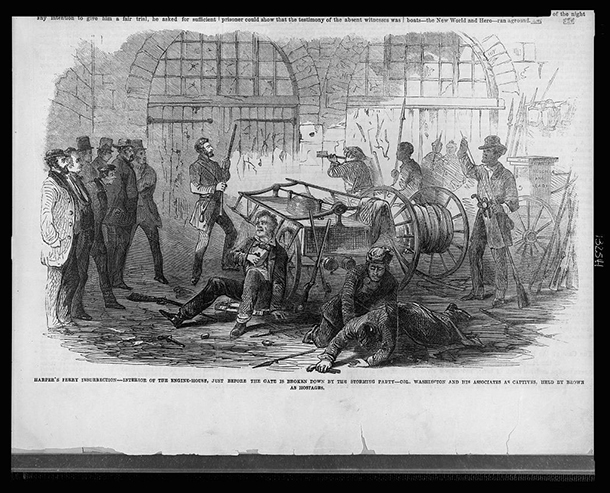

FULLER: In October of 1859, just as Darwin was finishing his book, John Brown led a small band of white and black rebels, as it were, to raid a federal armory in Virginia in the hopes of releasing weapons to the slave population and fomenting a slave rebellion. The rebellion went horribly wrong. Brown was injured and imprisoned almost immediately. And in December 2nd, in a widely publicized trial, he was executed. And that trial galvanized American opinion about slavery, it intensified animosity throughout the two regions, the north and the south, and it occurred just as Darwin's book was arriving on the shores.

PALMER: Before we leave the issue of Harper’s Ferry, I'd like you to read a piece of your book, if you wouldn't mind. It's on page 220. I think one of the important things about this is that it's almost the thesis of the book.

FULLER: Yeah, the argument here is that if John Brown had not attempted his raid on Harper's Ferry, a whole sequence of domino effects might not have occurred and likely Lincoln would not have won the election, and so Brown's raid is really a seminal moment in American history that led to Lincoln's election and also led after Lincoln's election to the dissolution of the Union.

PALMER: If you could read that, please.

FULLER: Lincoln's ascendance to the country's highest office was a direct result of Brown's attack on Harper's Ferry which had divided Democrats and left them without a viable candidate. During the summer of 1860, while debates over Darwin's theory reached their apex, America's pro-slavery press had vilified Lincoln, using his ungainly visage in countless cartoons. Lincoln was portrayed as a suitor of black women or as the missing link between blacks and whites. Sometimes he was even a gorilla -- Ape Lincoln. After the election, the south immediately revolted. Former Democratic President James Buchanan addressed Congress to complain of ‘the long continued and intemperate interference of the northern people with the question of slavery in the southern states.’

Charles Darwin, age 51 (Photo: Messrs. Maull and Fox, from book by Karl Pearson, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

The different sections of Union are now irate against each other, and the time has arrived, so much dreaded by the father of his country when hostile geographical parties have been formed. Buchanan was referring specifically to a series of rallies held throughout the south in support of secession. But this language made use of the same powerful metaphors of struggle and extinction that had appeared a year earlier in the origin of the species.

PALMER: That's a very interesting to me argument. That, in fact, the importance of Harper's Ferry was indeed to give you Lincoln the president and ultimately the Civil War and emancipation.

FULLER: That's exactly right, and I suppose one of the things I was getting at with my book was the way a kind of cultural configuration had already developed itself in the US. And so, when Darwin's book arrives in early December 1859, it's as though it explains everything going on in the United States about race, but also about the enormous divisions and competition between the two regions.

PALMER: And also this whole question of whether or not man is one race or many races. “On the Origin of Species,” obviously suggests that ever-fitter ever-fitter variations on any species are coming along, suggests that man is heading towards a more perfect being, and where do slaves or where do black people fit into that?

1859 edition of Darwin's Origin of Species (Photo: Author unknown, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

FULLER: That's the primary conversation that Darwin's book contributed to in the first year of its arrival in the US, and we often forget that that in the 1840s a dominant scientific strain of thinking about human races had become prominent. The so-called American ethnologists argued that the various races had been created separately and in different places. The white race was the best that God had managed to do. Other races were sort of trial experimental efforts that hadn't gone quite as well as He had initially hoped, and of course this was enormously satisfying to the Southern slave powers. And Darwin enters into that debate by suggesting that all creatures, including human beings, share common ancestors, and that in point of fact, blacks and whites are not separate species or differently created humans but are, in fact, brothers and sisters.

PALMER: So, that's obviously gives an enormous goose to the anti-slavery forces because here is another child of God in chattel slavery.

FULLER: That's exactly right. So, my contention is that Darwin's book initially arrives in this country and really just spreads like wildfire. "On the Origin of Species" is published in the US a month after the British edition arrives, and it's described in all sorts of newspapers and periodicals within the first month or so. But the reason it has such widespread readership and interest had to do with the slavery question first and foremost.

A daguerreotype of John Brown produced by John Bowles, c. 1856. (Photo: John Bowles, Boston Athenaeum public domain)

PALMER: Now, it was Asa Gray that first brought Darwin to this country. Who was Asa Gray? And how was important he in spreading the ideas?

FULLER: Asa Gray was the first botanist at Harvard College, and he was a world-class, largely self-taught scientist who had been in correspondence with Charles Darwin throughout the 1850s. Darwin, he liked to ask Gray questions about botany because he himself was more of a zoologist, and throughout the 1850s Asa Gray provided loads of evidence and examples for Darwin, which eventually made their way into "On the Origin of Species." In the late 1850s, a little-known scientist named Alfred Russell Wallace on his own independently came up with the exact same theory of natural selection that Darwin had come up with, and Darwin was crestfallen and believed all of his work on the theory had been for naught until he remembered that he had told Asa Gray about the theory several years earlier. So he owed an enormous amount of gratitude to Gray, and to show that gratitude he sent Gray the first copy of "Origin of Species" to these shores and Gray read it enthusiastically and takes it upon himself to become the American proselytizer of Darwin's theory, and in three essays in the summer of 1860, he argues for the legitimacy and the credibility of Darwin's work in the pages of "Atlantic Monthly."

PALMER: But another very famous Harvard luminary was very much not convinced about Darwin. Tell me about that. It was Louis Agassiz.

Depiction of the interior of the engine house during John Brown's raid, published in Frank Leslie's illustrated newspaper November 5th, 1859.

FULLER: Louis Agassiz was the Professor of Zoology at Harvard College, and far and away the most well-known popular scientist of his day, and the foremost opponent of Darwinian theory in America in 1860, and the reason that he was so vehemently opposed to Darwin's theory is because he was also the strongest advocate for the theory of special and separate creation that I discussed earlier. He was a proponent that blacks and whites and other races had been created separately, just as he believed Monarch butterflies were created in specific environments. Darwin's theory threatened his own belief in special creation, and so he fought back vigorously.

PALMER: Now, it arrived quite soon in Concord, which was the home of Henry David Thoreau among others, and there was a huge intellectual foment going on anyway there. What was their reception of this book?

FULLER: So, it was mixed as Darwin's reception has been mixed to this very day. Ralph Waldo Emerson read it in a somewhat shallow way and saw the idea of evolution as progressive and developing always to something better and more majestic, and so he read Darwin as essentially a confirmation of his own theories of transcendental progress. Bronson Alcott, who was even arguably a greater idealist than Emerson, rejected Darwin outright, and his argument was that any theory that began with material processes and the physical was starting at the wrong end, that one had to begin with the divine spirit and work one's way down. Only Henry David Thoreau of the transcendentalist cohort really grappled with Darwin's theory. In a way that was both supple, tough-minded and ultimately I think synthetic. That is to say, he was able to combine his transcendental beliefs with Darwin’s materialism in a new kind of approach to nature.

PALMER: Now, what were the other strands of thought or arguments that were being played out in Concord at the time, as well as the slavery debate?

FULLER: Well, the other primary debate that quickly surrounded Darwin's book had to do with the question of religion. Darwin's theory, by not requiring a divine providential design in the creation of either animals or people, smashed the long-held belief that people had been created in God's image. Theological magazines picked up on this pretty quickly. The Concord transcendentalists took a while to realize that those were the stakes of Darwin's argument. They were so smitten by the way the book could be used in the abolition debate that they really were not overly concerned about the religious debate until about the middle of 1860 or so.

PALMER: Though, actually, Darwin, of course, pulls his punches himself a bit on this. He leaves open exactly where everything started and how everything started, and indeed, what the relationship is between the primates and humans.

Randall Fuller (Photo: Erik Campos)

FULLER: That's right. Darwin was very cagey this way. He wisely left out all discussion of humans in "On the Origins of Species" but it's also important to state that in 1860 Darwin himself was on the fence about the role of a divine creator in nature, and only over time does he increasingly realize that God is not necessary for his theory to operate.

PALMER: Were Darwin's theories actually widely accepted in the north? I mean, you've spoken about Agassiz being very opposed, but among the general population did they go down well?

FULLER: They were pretty quickly absorbed into the culture. We may not believe or think that given the enormous difficulty the theory has in contemporary America, but by the late 1860s, less than a decade after the book arrived, Darwin's theories were taught in all colleges as credible theory.

PALMER: But you hardly mention the south. I mean, at this time, did these theories get down to the south and how were they received there?

FULLER: Finding out how Darwin's theories were received in the south is a little trickier than in the north where we have access to diaries and journals of all of these major thinkers, but the reviews of the book which appeared first in New England -- almost immediately appeared in places like Richmond, Virginia, and New Orleans -- and without the kind of resistance that you might think. They were usually reviews that reported upon this interesting new theory that proposed to explain the creation of new species.

PALMER: As I read this book, there seems to be more than a few parallels between what was happening then and what is happening now. Do you think it has lessons for us?

FULLER: Well, I certainly think it does and particularly I think there's a cautionary tale about bending evidence or facts to a preconceived narrative or ideology, and this is why Thoreau is sort of a hero for me in the book. He tries not to do that to the best of his abilities.

CURWOOD: Randall Fuller’s new history is “The Book that Changed America.” He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- “The Book That Changed America”

- About Randall Fuller

[MUSIC: Lawrence Blatt, “Black Rock Beach” on The Color of Sunshine, LMB Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Kit Norton, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org -- and like us please on our Facebook page -- PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment. Developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment -- supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Jean Ferenbach of Boston Massachusetts, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth