August 25, 2017

Air Date: August 25, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Value of National Parks

View the page for this story

Research from Harvard and Colorado State finds that Americans value maintaining the National Parks system through their taxes at over 30 times its annual appropriations. Host Steve Curwood sat down with Harvard professor Linda Bilmes to discuss why Americans care so deeply for these iconic places and how to put their future and protection on a sustainable financial footing. ()

BirdNote: Voices of Our Public Lands

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

We the People own nearly 850 million square acres of US public land and ocean, and as BirdNote’s Mary McCann points out, these spaces provide vital habitat for over a thousand diverse species — from the Bachman’s Sparrow in the Southeast to Alaska’s Willow ptarmigan. ()

Emerging Science Note: Backyard Garden Threat to Bees

/ Jay FeinsteinView the page for this story

Pesticides are a leading contributor to recent widespread declines in honeybee populations. But don’t blame farmers. As Living on Earth’s Jay Feinstein reports in this note on emerging science, a new study in Nature magazine found a large amount of bees’ pesticide exposure came from non-cultivated areas, including backyard gardens. ()

Squash Bee: The Pollinator That Follows Farmers

View the page for this story

Thousands of species pollinate our plants and guarantee our food, but one particular bee specializes in the squash family. As ancestral farmers spread the cultivation of squashes through the Americas, the squash bee followed. North Carolina State biologist Margarita Lopez-Uribe explains the history to host Steve Curwood. ()

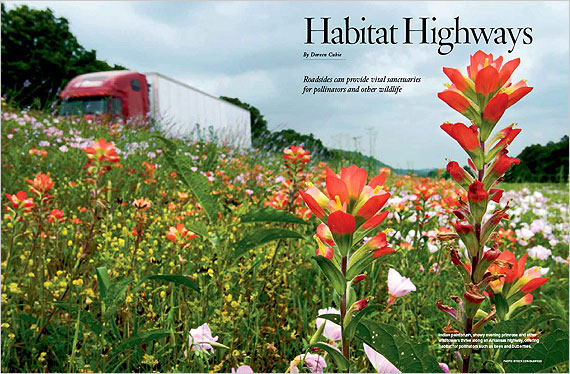

Roadsides as Vital Habitat

View the page for this story

Some 17 million acres of green space line US highways and byways, and it’s vital habitat for pollinators, as well as small voles and mice and birds. Bonnie Harper-Lore, a restoration ecologist formerly with the Federal Highway Administration, tells host Steve Curwood about the value they offer to wildlife and how President Lyndon Johnson’s wife, Ladybird, helped uplift this elongated haven for creatures and wildflowers. ()

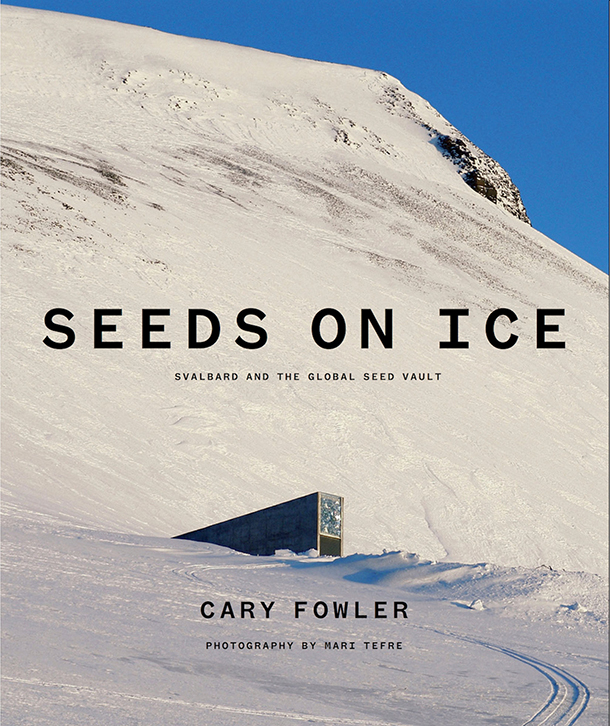

Seeds on Ice: Preserving the World’s Agricultural Heritage

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Deep in an icy mountain not far from the North Pole are rows upon rows of boxes filled with seeds -- nearly a million samples gathered from nations collections around the globe. Cary Fowler is a founder of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and the author of the new book documenting its story and its treasures called Seeds on Ice. He joins Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer to explain why humanity needs a seed vault at the top of the world to ensure the genetic diversity of our agricultural heritage. ()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Linda Bilmes, Margarita Lopez-Uribe, Bonnie Harper-Lore, Cary Fowler

REPORTERS: Mary McCann, Jay Feinstein, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Public opinion may seem divided -- but Americans do love their national parks and a survey finds they’d pay more taxes to protect them.

BILMES: Could we quantify the fact that I might place a value on protecting the Grand Canyon, even if I don't visit – that that still means something to me. We were amazed to find that the value was $92 billion dollars, which is more than 30 times what the annual appropriation for the parks is.

CURWOOD: Also, birds, bees and butterflies aren’t just pretty – they pollinate many of the plants that feed us—

LOPEZ-URIBE: Squash, pumpkin, zucchini – are actually all pollinated by this squash bee. And this bee expanded its range dramatically thanks to the cultivation of crops outside of the native range of the plants that are not domesticated.

CURWOOD: Native Americans, the squash bee and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Value of National Parks

The view from Glacier Point in Yosemite National Park. As of June 30th of this year, attendance was up by 3 million from that time last year. (Photo: Taylor Davis, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Ryan Zinke’s Interior Department and the President are reassessing the size and status of some 27 National Monuments, but Americans are overwhelmingly in favor of public lands. Indeed, taxpayers seem prepared to actually pay to support the National Parks.

That’s what Linda Bilmes of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and colleagues from Colorado State University discovered when they carefully surveyed taxpayers. Their research shows that the public would pay more than $90 billion a year to preserve and protect iconic places from Acadia to Zion. Congress typically grants the US National Park system less than $3 billion a year, and there’s a multi-billion dollar backlog of corroded or broken infrastructure. Professor Linda Bilmes is also a former US assistant secretary of commerce for administration and budget, and we joined her in her office at Harvard. Welcome to the Living on Earth!

BILMES: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: What prompted you to do this study?

BILMES: I was lucky enough to serve on the Second Century Commission. It was a group of prominent Americans including Sandra Day O'Connor, Sylvia Earle, Rita Colwell, James McPherson of Princeton, and a number of senators and congressmen, and we were thinking about how to protect the National Parks over the next 100 years. And one of the conclusions that we reached was that the financial picture was not sustainable given the way that the National Parks are funded at the moment. So in order to begin thinking about creating a more sustainable financial structure for the national parks, we needed to establish a baseline for what the parks were actually worth, and actually no one had done this before. So this led me to begin thinking about how one could estimate the total economic value of the National Park Service and to do it in time for the centennial.

An assessment of the economic value of the National parks that was published this month puts the worth of America’s national parks at $92 billion per year. (Photo: Lorne Sykora, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now some would say that our National Parks are priceless, you can't put a price on something like the Grand Canyon or the Grand Teton. So what you're talking about, I gather, is the capital value of this, that is, as an asset that America should look at. It's not really for sale.

BILMES: No, it's not for sale, but you raise a very important point, which is how do we actually value a priceless asset? And economists do this by asking what one would pay not to lose that asset, so in the conservation field we are particularly at a disadvantage because there's a very robust, well-established accounting procedure for figuring out what the value is of constructing a building, for example, but there's no agreed-on methodology for how one accounts for not constructing a building, for protecting the land.

CURWOOD: So how do you solve this dilemma?

BILMES: Well, we used a methodology similar to that used by civilian US agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration and OSHA, and we conducted an economic survey. So I want to stress that this was not a poll, but an economic survey in which we went out and asked households what they would pay to not lose the National Park Service units and programs. Surveys were sent out to households across the country, and with different amounts of money on them, and so we could figure out that at the higher levels of payment fewer people would be willing to pay, even if they love the parks, and at the lower levels, for example, $10, $15, practically everyone was willing to pay that much in higher taxes. And we're not advocating higher taxes for parks, but this was a way of getting at what the value was that the public attributes to protecting the parks and park programs.

CURWOOD: So, some 90, 95 percent in your study said that these parks are important. I mean, what else are we unanimous about as Americans these days?

BILMES: Well, I think that there are very few entities and public assets that command this kind of respect, and really love, that we heard in this survey. But I think beyond that what we felt we were trying to do was to understand how people who didn't necessarily visit the parks felt about the parks and the programs because we already knew that those visit the parks typically love them and many surveys show that a lot of people like the parks very much. They think they are wonderful, but the question was, could we quantify the fact that I might place a value on protecting Gettysburg or protecting Ellis Island or protecting the Grand Canyon, even if I don't visit, that that still means something to me, and that's where we were amazed to find that the value was $92 billion which is more than 30 times what the annual appropriation for the parks is.

CURWOOD: So what is being spent on the park service now and what does it need?

Linda Bilmes is a Senior Lecturer in public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. (Photo: Diana Bowen/NPS)

BILMES: Well, the Park Service currently gets an annual appropriation of about $2.5 billion a year and the Park Service budget has actually been declining over the past 20 years. In fact it's 15 percent below, in today's dollars, what it was in 2001. In addition, the park service has a maintenance backlog of about $12 billion, and that is a backlog of infrastructure projects, for example, campgrounds and trails and bridges and roads and things like that. So not only is the annual appropriation insufficient to cover its needs, but it has been completely unable to finance its long-term infrastructural, maintenance needs. So, in other words, the National Parks as they're currently funded are decaying because of the fact that we're not keeping them up.

CURWOOD: And yet the public is willing to spend much, much more, almost 30 times more then what the annual appropriation is. So why are we in this state?

BILMES: Well, I would say that there are two major points around the National Park funding. First of all, our study shows that the public places a very high value on the parks and so we are urging Congress to give a birthday present of some amount of money to begin tackling the maintenance backlog for the parks. But when you think about the broader issue which is that the public is conservatively valuing the parks at 92 billion, and the amount we spend on the parks, even including fees and so forth is below $3 billion, there's no way that the government is going to be able to make up that huge gap.

So this is where private philanthropy comes in, and there is a National Park Foundation, which has operated for a number of years. The private philanthropy has played a role in shoring up many individual parks. However, we don't have an overall philanthropic, long-term perpetuity funding structure for the Parks. So I've been urging for some time that we set up an endowment for the Parks which is a funding mechanism that Harvard University has, for example, and many museums and hospitals and others that have a kind of forever mission because the mission of the parks is to protect these special places, unimpaired forever and the only way that they can do that is if they have an endowment which they can tap into to try and make the investments and keep up with the long-term maintenance, repair, and stewardship which is their mission.

CURWOOD: Your favorite park or parks?

BILMES: You know, I have to say that I grew up in San Mateo, California, and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area is probably my favorite because I know it best. It stretches along the coast of San Francisco, is a fantastic place, and it also does an enormous amount of educational efforts. I'm also very, very partial to Yosemite and to Yellowstone in the winter. Yellowstone Park, when it's empty in February and it's cold, is like no place on the planet.

CURWOOD: Linda Bilmes is the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Senior Lecturer in Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. Thanks so much for taking the time.

BILMES: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Read the paper: “Total Economic Valuation of the National Park Service Lands and Programs”

- Also by Linda Bilmes, et. al: “Carbon Sequestration in the U.S. National Parks: A Value Beyond Visitation”

- Linda Bilmes Faculty Profile

- National Park Service Centennial

- Annual Park Budget Justifications

BirdNote: Voices of Our Public Lands

Willow Ptarmigan. (Photo: Patty McGann, Flickr CC)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: The nation’s public lands stretch from Alaska to Florida – and given the wide variety of landscapes and temperatures, it’s no surprise they give a refuge to an astonishing variety of birdlife. Mary McCann has today’s BirdNote.

http://birdnote.org/show/voices-our-national-public-lands

BirdNote®

Voices of Our National Public Lands

[Bachman’s Sparrow song]

Bachman’s Sparrow (Photo: ©Joanna Kamo)

MCCANN: The diversity and richness of bird voices across the United States! Wow!

In the Southeast, at Florida’s Ocala National Forest, a Bachman’s Sparrow sings a lovely, clear whistled song.

[Bachman’s Sparrow song]

In the Midwest, at Rice Lake State Park in Minnesota, a Yellow-headed Blackbird offers its gruff repertoire of growls and toots. [Call of Yellow-headed Blackbird]

After dark in the Southwest, at Arizona’s Bill Williams River National Wildlife Refuge, a Black Rail utters its unmistakable call. [Call of Black Rail]

And in Alaska’s Denali National Park, a Willow Ptarmigan chuckles loudly across the tundra. [Call of Willow Ptarmigan]

Northern Hawk-Owl (Photo: ©Gregg Thompson)

But all of these places have something vital in common. They are part of our National Public Lands, lands owned by us, the American people. Comprising nearly 850 million acres of land and 3.5 million square miles of ocean, our public lands and waters provide habitats vital to more than 1,000 species of birds. Now that’s something to crow about! [Call of Willow Ptarmigan]

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Song of Bachman Sparrow [166561] recorded by R. Faucett; song of Yellow-headed Blackbird [105686] by G.A. Keller; Black Rail [56890] recorded by G.A. Keller; ambient drawn from Willow Ptarmigan [50031] recorded at Denali by L.J. Peyton.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org September 2013 Narrator: Mary McCann

www.publiclandsday.org

http://www.neefusa.org/programs/index.htm

Bachman’s Sparrow © Joanne Kamo http://www.pbase.com/jitams/image/113389755

Yellow-headed Blackbird - Joseph Higbee FCC https://www.flickr.com/photos/21876608@N02/14009277500

Northern Hawk-Owl © Gregg Thompson

Willow Ptarmigan - Patty McGann FCC https://www.flickr.com/photos/pattymc/9060981651

http://birdnote.org/show/voices-our-national-public-lands

Yellow-headed Blackbird (Photo: Joseph Higbee, Flickr CC)

CURWOOD: For photos of the Willow Ptarmigan and all those other birds including the Bald Eagle, whistle on over to our website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Learn more about birds on public lands on BirdNote

[MUSIC: John Denver, “Windsong,” on Windsong, by John Denver and Joe Henry on RCA Records https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXOihxjXqAo]

CURWOOD: Coming up –How roadsides can help protect wildlife. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jim Henry + Brooks Williams, “Minor Swing” on Ring Some Changes, by Reinhardt/Grappelli, Signature Sounds]

Emerging Science Note: Backyard Garden Threat to Bees

There are fewer than 10 different honeybee species -- a fraction of the 20,000 known species of bees. (Photo: Louise Docker, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. In a minute, new facts about one of the busiest agricultural workers, but first this note on emerging science from Jay Feinstein.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

FEINSTEIN: 80 percent of pesticides used in the U.S. are sprayed on agricultural sites, according to the EPA. Environmental advocates often argue this is partly responsible for the recent widespread decline of honeybees. Yet, a new Purdue University study suggests that key to helping save these vital pollinators is what we do in our own backyards.

The Western Honey Bee, also known as the European Honeybee, is the most common honeybee worldwide. (Photo: Ricks, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Scientists found that contrary to popular belief, most of the pesticide-ridden pollen bees gather may be from urban landscapes and non-cultivated plants. For 16 weeks, researchers collected pollen from bees at three different sites in Indiana and analyzed it for pesticides. They chose locations with wildflowers, shrubs and trees to test non-agricultural sites. Then, they tested different sites at the border of maize fields in areas that received chemical treatments such as the neonicotinoid Clothianidin and finally areas that received no treatments.

The researchers found that bees collected a much larger amount of pollen from the non-cultivated plants than from the food crops and that the samples from these uncultivated areas also contained a larger amount of pesticides. This suggests that pesticide exposure for bees in non-agricultural sites may be higher than previously thought and they found that the pyrethroid insecticides, commonly used by homeowners to kill pests like mosquitoes, were present in the largest quantities and also likely cause the most harm to bees.

A Western Honey bee bringing pollen back to its hive. (Photo: Muhammad Mahdi Karim, Wikimedia Commons GFDL 1.2)

The scientists note that these results provide important information on bee foraging habits and bee hazards, along with tips gardeners might consider when treating their yards.

That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Jay Feinstein.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- The Nature article about the study

- An information sheet about pesticide use which includes EPA statistics about the amount used in agriculture

- Listen to a previous LOE report on how pollinator declines impact public health

- National Geographic: The Last, Best Refuge for North America’s Bees

Squash Bee: The Pollinator That Follows Farmers

Peponapis pruinosa bees gather pollen from a squash flower (Photo: USDA Agricultural Research Service, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Honeybees make a $20 billion contribution to US agriculture, according to the American Beekeeping Foundation, but they’re by no means the only bee that helps feed us. There’s one particular wild pollinator that follows human activity. The squash bee moved beyond its native range in the Americas as people spread the cultivation of indigenous squashes. Margarita Lopez-Uribe studies evolutionary biology at North Carolina State University and co-authored the paper laying out this connection. She joins us from her lab -- Margarita, welcome to Living on Earth!

Zucchini and many other squashes are pollinated by squash bees (Photo: Sea Coast Local, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Hi. Thank you.

CURWOOD: What are we really talking about when we say the squash bee? How different are these bees from the familiar honeybee?

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, they are very different. There are about 20,000 species of bees in the world and the honeybee is only one of them. So when you're talking about the squash bees, actually there are about 20 species that specialize in squash pollination, and the one that I focus on is only one of those 20, and it's called Peponapis pruinosa.

CURWOOD: And what does it look like?

LOPEZ-URIBE: The bee is about the size of a honeybee, but it looks a little bit different to someone that has you know, a trained eye. And one of the big differences morphologically is that the honeybee collects the pollen in a structure in the hind legs. It's called a cubicula and it's basically a basket. So the honeybees visit the flowers, they collect the pollen, they put a little bit of nectar in the pollen and then they make these wet balls of pollen that they store in those baskets in the hind legs. The squash bee does not have that basket. It has an incredibly long and very conspicuous hairs in the hind legs, and so the pollen gets actually stuck in those hairs, and one of the features of the squash pollen is it has very large grains of pollen, so it easily gets attached to those hairs in the hind legs.

Squash bees are solitary and make their nests beneath squash plants (Photo: Silar, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Now, tell me the crops that they pollinate for humans. When you say squash, what are we talking about here?

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, they specialize in pollination of one plant genus, the genus Cucurbita and that plant genus happens to actually be the genus of a lot of different crops. So we are talking about squash, pumpkin, zucchini. All of those crops are actually part of the genus, the plant genus Cucurbita and they're all pollinated by these squash bees.

CURWOOD: What's neat about your paper is that you figured out the bees spread their range thanks to the cultivation of squash. What prompted you to look at this?

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, so if you look at the distribution of the bee today, for a big chunk of their distribution they are only co-distributed with plants that are domesticated by humans, and so we already predicted that the bee had expanded its range outside of the ancestral range of the plants that were not domesticated by humans. What I did was I looked for genetic markers to actually see if there were signatures of the genetic level that could corroborate this hypothesis that we had, and that's what we found, that indeed this bee expanded its range dramatically thanks to the cultivation of these crops outside of the native range of the plants that are not domesticated.

CURWOOD: What surprised you most about your findings?

Squash bees’ long hairs allow the pollen of plants in the Cucurbita genus to stick to their legs. (Photo: The Packer Lab, Creative Commons)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, there were a couple of things that were very interesting. One thing was the route of the movements of the bees. So, these bees are very very abundant in northeastern North America. One possible way they got there was actually kind of you know like along the east coast of North America, but actually what I found is that the bees moved through the Midwest and then colonized the northeast of North America. So they kind of like took the longer route to get there. The other interesting finding was even though this was a rapid expansion, we did find some signatures of severe bottlenecks. What happens is that even though these bees have been in eastern North America for quite a while – we’re talking about thousands of generations - they still show very low genetic variability. This is interesting and it's something that I'm really curious to keep investigating because what I hypothesize is that the fact that these bees are so tightly associated with crop management and agricultural systems that means that probably there is something that we're doing with the crops of these bees are relying on that is keeping the genetic variability of these populations extremely extremely low. And that would make them really vulnerable to changes in the environment.

CURWOOD: You term these bees as being solitary, but, of course, how do they reproduce then?

Instead of long hairs, honeybees use ‘baskets’ on their legs to carry bundles of pollen in. (Photo: Aphaia, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, the lifecycle is very different. So what happens is as I told you these bees nest underground and they have a yearly lifecycle. Usually by midsummer, the females and males emerge from the ground, they mate, all females are fertile, and then the females who have mated, they start looking for areas where they can make their own nest. Once they find a good spot, they make the nest, they start collecting pollen and nectar, they lay eggs, they close those nests and then they never see the babies. They die that summer, and then the next year those eggs of course go through the whole development and adults emerge and the cycle starts again.

CURWOOD: I imagine that if they build their nests in the ground, it's close to the plants. What happens when the plows come through?

Common agricultural practices like tilling can harm the squash bee by destroying their ground nests (Photo: CC BY-SA 2.0)

LOPEZ-URIBE: [LAUGHS] Yeah, so that's one of the things that I'm worried about, and that I think it's probably driving some of these low genetic diversity populations is the fact that agricultural systems of squashes and pumpkins actually include what we call crop rotation and soil tillage, and so I think a large number of these individuals just dies every year as a result of these agricultural practices.

CURWOOD: So, if I understand this, honeybees can also pollinate squash, so what's the difference here?

Margarita López-Uribe with a honey comb. Social honey bees store food, but the solitary squash bee does not. (Photo: courtesy of Margarita López-Uribe)

LOPEZ-URIBE: Well, there are major differences. One of them is the time of the day that these bees forage. So Peponapis pruinosa is a very early morning bee. When I was doing fieldwork for the study, I would have to get up really really early because most of the foraging happens the first one or two hours of the day. Honeybees and other pollinators of these crops like bumblebees, they usually pollinate later in the day and for much longer.

The other difference, and this is something we don't really know much about, is it seems to be the pollen of these crops has some chemical properties that make the pollen highly unattractive to most bees. Peponapis pruinosa pollinates squashes and pumpkins because the female bees are collecting the pollen. So in the movement between the flowers they are transferring pollen grains between flowers. The honeybee goes to the flowers only for the nectar, and so it's a much less specialized behavior in terms of the foraging. We know a lot about the honeybee but very little, almost nothing about the other thousands of the species of bees in this planet.

CURWOOD: Margarita Lopez-Uribe is a postdoc researcher at North Carolina State University. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

LOPEZ-URIBE: Thank you so much. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- About the paper, “Crop domestication facilitated rapid geographical expansion of a specialist pollinator, the squash bee Peponapis pruinosa”

- More about squash bees

- About Margarita López-Uribe

- Watch “Journey of the Squash Bees”, a short video featuring Dr. López-Uribe

Roadsides as Vital Habitat

The National Wildlife Federation recognizes roadsides as vital sanctuaries for pollinators and other wildlife. (Photo: courtesy of NWF)

CURWOOD: When you set off for that summer road trip – take a good look at the medians and roadsides. All those miles of broad, green highway rights of way turn out be vital habitats for many small critters, as well as pollinators including bees, butterflies and birds. Bonnie Harper-Lore was a restoration ecologist for the Federal Highway Administration, and a member of the Commission on Minnesota Resources. Welcome to Living on Earth, Bonnie.

HARPER-LORE: Greetings, Steve, how are you?

CURWOOD: Good. Thanks for joining us today. Now, we're talking about those strips of vegetation along the highways. There's often commercial or residential property right behind them. So, nationwide, just how much of this habitat is there?

HARPER-LORE: Well, I think the listeners will be surprised to find out that the area between the pavement and the right of way fence on county, state, and interstate highways adds up to a total of 17 million acres – possibly millions of acres of conservation opportunity.

Bees are some of the pollinators that depend on roadside habitat. (Photo: Beatriz Moisset / USDA)

CURWOOD: You know, recently we saw National Pollinator Week, which was a time to celebrate the pollinators, spread the words about what people could do to protect them. So what we have to celebrate in terms of roadside habitat for pollinators now?

HARPER-LORE: Well, the fact that it’s a news item at all is something I'm celebrating because I always saw roadsides from the beginning of my career 30 years ago as an opportunity to benefit wildlife, small wildlife, small birds, small mammals, and migrating birds also use these same corridors. So if they have places to find food and cover, they are all going to do better and their populations will continue to hold where we need them to hold.

CURWOOD: By the way, I also understand that this roadside habitat has some of the most endangered habitat in various areas – like there are parts of the original prairie that are protected alongside roads, sort of by accident. You can sometimes find real old-growth trees. I mean, how much of a treasure trove is this territory?

HARPER-LORE: Well that's just it: We don't have a complete inventory of all of our roadside vegetation. I would indeed like to see that happen because I think we would be surprised at how many remnants of these old forests, old prairies, old wetlands even do exist. We began doing a bit of that inventory in 1993 in California – found 19 remnants within a very short time and began protecting them, managing differently, not mowing and spraying as they had in the past. So there are some of these. I mean, it's surprising that they do exist. I know Florida has also some endangered, I believe, pitcher plants that are growing in their rights of ways and they are now watching over them differently than they have in the past. So if we know they're there we can do differently.

Monarch butterfly caterpillar feeds on milkweed. Along Interstate Highway 35, a 1,568-mile-long road between Duluth, Minnesota and Laredo, Texas, Monarch habitat is being preserved. (Photo: Marshal Hedin, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, give us the big picture as to who are the partners in these pollinator conservation efforts.

HARPER-LORE: Well, there were actually a few states that were doing pollinator-focused efforts. Wisconsin comes to mind in that the Karner Blue butterfly is an endangered species and they actually put together, I believe, a 20 member partnership quite a few years ago to protect the Karner Blue and that partnership was mostly private sector but some state and county agencies, too, and they've done a great deal to keep the Karner Blue safe in Wisconsin. So those kinds of things have happened individually but you have to realize every state Department of Transportation basically does its own thing, makes it own priorities but now, now that there's been a White House task force there has been a pollinator-enhancing bill, a reauthorization act that actually supports pollinators, all of the states will start moving in that direction, especially if they know the public is interested. So public support needs to be there.

CURWOOD: Yeah tell me about the multistate project known as the I-35 corridor, and what's been done in terms of Monarch protection there?

HARPER-LORE: Well, ironically back in 1993, a group of six states asked the Federal Highway Administration, where I worked at the time, to work together and get some funding to support their effort to actually restore prairie along the I-35 corridor and to protect any remnants that already existed there.

CURWOOD: And remind us where the I-35 corridor is.

Ladybird Johnson, First Lady during the Lyndon Johnson administration of the 1960s, spearheaded the Highway Beautification Act. (Photo: Frank Wolfe / LBJ Library, Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

HARPER-LORE: It runs from Minnesota through Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Texas, therefore connecting Mexico to the edge of Canada and of course that's where the Monarchs fly.

CURWOOD: What other wildlife uses this roadside habitat? You know, you often see hawks hanging out there. The hunting must be pretty good for them, I guess?

HARPER-LORE: It certainly is. I watch hawks, all kinds of raptors, sitting on the light standards along highways and signposts just waiting for lunch to materialize down there in the vegetation on the roadside. Yes, they do well there because there are lots of mice and voles, other small things possible, plus one that actually motivated reduced mowing here in the Midwest, pheasants and other waterfowl, different kinds of ducks will nest in these rights of ways. So, it's amazing, when you're screaming by at 55 to 70 miles an hour, what's happening out on that green strip that you probably will never ever imagine.

CURWOOD: Lady Bird Johnson, first lady during the Lyndon Johnson administration, her signature cause was highway beautification back there in the 60s. What kind of impact – what kind of lasting impact – has her work had on roadside habitat and pollinators do you think?

HARPER-LORE: Well, I smile because it's because of Lady Bird Johnson that my job even existed with the Federal Highway Administration. I was working for the Minnesota Department of Transportation establishing their wildflower program back in the 1980s when I got an invitation from Mrs. Johnson to come visit with four other states who were also interested in planting wildflowers and we sat and talked with her for two days, and the thing we didn't know she would do – because she asked us what did we need to be able to do more – within that same year, she saw to it that there was an amendment to the transportation bill that requires all states to use a certain percent, not a large enough percent, but a certain percent of their budgets on native wildflowers. So, a few years later, I was looking for a job and I talked to the people I had met at Lady Bird Johnson's and they said, “Well there's an opening in Washington”, and within a few months I was able to be in charge of the national wildflower program. Thanks to her, we've come some distance. I've had people write me with their thank yous for the wildflower program over time. One of them was an 18-wheel truck driver who said, “Thank you for the wildflower program, I drive from coast to coast and it helps me...gives me something to look at and keep me alert and awake,” and I was like, “What a surprising thank you letter that was.” And there are others too. I have a file full of them.

CURWOOD: Bonnie Harper-Lore served in the Federal Highway Administration as a restoration ecologist. She is now with the Commission on Minnesota Resources. Bonnie, thanks for taking the time with us today.

HARPER-LORE: You're welcome. Thank you for what you do.

Related links:

- The I-35 Corridor To Become a Habitat For Bees, Monarch Butterflies, and Other Pollinators

- A Transportation Research Board webinar about how roadside mowing affects pollinators

- Bonnie Harper-Lore serves on the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota

- Tips for preserving roadside habitat from the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

- Green Highways: New Strategies To Manage Roadsides as Habitat

[MUSIC: Bobby McFerrin and Yo-Yo Ma, “Flight Of the Bumblebee” from The Tale of Tsar Saltan, on Hush, composed by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Sony Records

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nxr6Gu31Qms]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Seed saving on a super scale…That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bobby McFerrin and Yo-Yo Ma, “Flight Of the Bumblebee” from The Tale of Tsar Saltan, on Hush, composed by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Sony Records

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nxr6Gu31Qms]

Seeds on Ice: Preserving the World’s Agricultural Heritage

Cary Fowler led the effort to create the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (Photo: Mari Tefre)

CURWOOD: Time now to dive into a breathtaking and beautiful book that chronicles a profound and visionary investment of hope. It’s called Seeds on Ice. There are not many words but plenty of pictures that explain the thinking and work that created the Global Seed Vault at Svalbard, Norway. Author Cary Fowler spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Cary Fowler, you are the father of the Global Seed Vault. First of all, tell me what exactly this global seed vault is.

FOWLER: The Global Seed Vault – the Svalbard Global Seed Vault – is a backup insurance policy for all the seed banks around the world, and the idea is that we want to provide failsafe protection for the diversity of our agricultural crops, diversity that is stored in the form of seeds. You need cold temperatures, freezing temperatures, to conserve seeds long term. So we went close to the North Pole where it's very cold, and we built a facility inside of a mountain, which makes it also very secure, and there we're storing backup copies, seed samples of currently more than 850,000 different crop varieties.

PALMER: They are already national collections, as you've said, and seed vaults. Why do we need a backup?

The photographs in Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault are by Mari Tefre. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

FOWLER: We need a backup because bad things happen to seed banks, and there's so many examples of this that are catastrophic at a local or national level. There's been a fire and a flood inside the Philippine national gene bank, the Iraqi and Afghanistani gene banks were destroyed or at least very much harmed by the wars there. Seed banks in a way are a little bit like libraries and every once a while something bad happens to an individual book in a library and, likewise, even in a really great seed bank something bad will happen to a particular sample just by accident or mismanagement. And every time something bad happens like that, we lose that variety. In other words, it's an extinction event. We don't talk about saving a representative sample of Rembrandts and Goyas. We would like to save them all and ditto with agricultural plant diversity. We want to save all of that diversity. They’re all treasures.

PALMER: You point out that Norway is the ideal country, both to host this and indeed has the ideal place to put it, and indeed is accepted by the international community as an honest broker. Why is that so?

FOWLER: Norway has always played a really positive role in international discussions and debates frankly about how to conserve this material and how to exchange it between countries. It's a fairly contentious issue, believe it or not, and countries are formulating rules about how to and under what circumstances and conditions to exchange crop diversity. No country on Earth has the requisite amount of crop diversity to fuel their own plant breeding programs into the future and that includes the United States. So, every country on Earth is dependent on other countries, or interdependent with the globe, to secure the biological foundation of its own agricultural system. So Norway's played a great positive role in that and Norway provided the perfect conditions and not coincidentally, it also provided the funding for it, and we needed that.

PALMER: So tell me about Svalbard. Where is it and what is it exactly?

FOWLER: Svalbard is a group of islands, and if you look at a map, or you have a globe handy you go to the North Pole and look just a little bit southward. So if you were in Oslo, Norway, which most people think of as far north, you would need to fly about 1,300 miles north of there to get to Svalbard. The seed vault itself is located at 78 degrees North and it's the farthest North that you can fly on a regularly scheduled airplane, albeit only about once a day, and it's a remarkably beautiful exotic otherworldly place. It can snow on any day of the year. This is an area that’s twice the size of Belgium and about 60 percent covered with glaciers. Still, great infrastructure, very safe, secure. It was just the ideal location.

PALMER: It has to be said we're in an era of global warming. How safe is Svalbard for global warming? I mean, we hear about glaciers melting all over.

The seed vault contains more than a half billion seeds. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

FOWLER: Oh yes, well, Svalbard is not safe from global warming, no place on Earth is, but the idea with the seed vault and with all the good seed banks around the world is that you want to freeze the seed down to about minus three or four Fahrenheit, minus 18 Celsius and there's no place on Earth where you can do that naturally without mechanical cooling. So the challenge then is simply to find a place that gives you naturally cold temperatures, as cold as you can get, and from there you have to lower it a little bit further. So that's what we have in Svalbard, and the permafrost, we've built a tunnel that goes 130 meters into the mountain. It's a bit below freezing there. It's about minus five Celsius, and so even at that temperature, if our mechanical freezing were to fail, it would take months and months and months for that facility to warm up to something still below freezing, and even at that rate we calculate the seeds would be safe for decades. So we’d have a long time to fix the problem.

PALMER: There's one kind of irony and that is that the cooling that you have in the vault is actually powered by coal, and one of problems we've got of course, is global warming, and coal is one of the dirtiest fossil fuels we’ve got. Has this ever come up as an issue?

FOWLER: Well, we have to power the facility in some way. It doesn't take much. We don't have a big electricity bill, and there is a village up there that has to be powered and electrified, of course, and coal is local, it's locally mined. So, you know, we're not shipping oil over the ocean to power that facility, and in a place like that where you have three months of polar night every year, it would be pretty hard to run it solar.

The vault houses more than 860,000 seed samples packed in boxes placed on shelves. Each sample packet contains 500 seeds. (Photo: Jim Richardson)

PALMER: I've looked at the pictures in the book and they are stunning. I mean, it's very bleak and large and colorful and lots of northern lights, and lots of polar bears and not many people.

FOWLER: That's true. There are, I think, more polar bears than people and certainly more reindeer up there than people, and when you're up there particularly if you leave the little village you will have I think an emotional experience that few people on Earth have these days, and that's an experience that comes from being untethered to civilization, and you realize you're really out there, you get a pretty profound feeling that you're on your own and that nature is in control and that nature is a little bit bigger and more powerful than we are individually. It'll have quite an impact on you.

PALMER: So you’ve got this vault at the end of a 300 foot tunnel more or less. What exactly is it? What does it consist of?

FOWLER: At the end of the tunnel we have three vault rooms, and each vault room is, well, about 30 meters long, 10 meters wide and five meters high, and we're only storing seeds in one of those vault rooms. Everything about the seed vault has a lot of built in redundancy, so I did some calculations about how much space we would need to store all of the agricultural seed diversity in the world, and we have about three times as much storage space as my estimates indicated we would need because, well, I could be wrong. And when you walk into this final chamber it's extremely cold and it looks a little bit like a warehouse, frankly. We have shelves and we have boxes in the shelves, and each box contains about 400, 500 seed samples.

There are three main tunnels within the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (Photo: Mari Tefre)

They're all in individual packets, about 500 seats per packet, so currently I think we have about 500 million seeds down there, quite a few tons. And the boxes, they're pretty. They come from countries all over the world, and they have their little insignias on it, and when you walk down the aisles, you have to walk down the aisles with some humility because what you're seeing is the results of agricultural evolution over the last 15,000 years. It's essentially a biological history of agriculture, but it's also everything that agriculture could be in the future is represented in that diversity.

PALMER: Has every country bought into the idea of the need to preserve this seed heritage?

FOWLER: Well, the seed vault has seeds that are sourced from just about every country in the world including some countries that no longer exist, but that doesn't mean that every institution in every country has participated yet, and I think eventually they will. One of the other aspects of the management plan that we had to work out was a question about property rights. Who owns these seeds? So the way that we set up the seed vault was it would function like a safety deposit box at the bank where Norway owns the facility itself. In other words, it owns the mountain, but the individual depositor would own their seed deposits themselves and they and only they would have access to those seed deposit. So we don't send the United States collection to Canada or vice versa or whatever, but some countries simply take longer than others to come around to that that idea had to work through the bureaucracy so I'm not too worried about that, but I think we have a fairly good sample of the diversity in the world. I mean, we're looking at more than 150,000 different types of rice, and more than 150,000 different kinds of wheat and I think about 35,000 different bean varieties and on and on.

PALMER: So why do you need 150,000 varieties of wheat or rice?

FOWLER: We need that kind of diversity because we don't have a crystal ball about what the future will bring. We know that there are always surprises, that agricultural crops they're evolving as are the pests and diseases that strike them. And with global warming, we're seeing the natural range of pest and diseases change and so new assemblages of species are coming into being and we don't know how crops are going to react to that, and human beings change their tastes and the food industry changes its requirements over time and all of that means that we need different traits, and so this diversity is a little bit like an artist’s palette. We want as many colors as possible so that we can create new paintings and every time you take away a color, every time you take away diversity you limit your options and there have been cases in our lifetime where we've had to search the entire collection of a particular crop and have only been able to find one variety containing particular genes, in other words, traits, that are needed to essentially rescue the crop.

Different varieties of wheat are stored in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. (Photo: Marc Di Luzio, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

PALMER: Some people would argue that science has been able to breed new varieties. You don't think science could just be the answer here? You think we need nature?

FOWLER: Oh, I love science and I have a lot of respect for it, and this diversity is used by scientists every day both in basic biological research but also traditional plant breeding. But we're not gods and not only are the individual genes, traits, important but I think we're, in the future we're going to learn a lot and benefit a lot from understanding the combinations of traits that have been assembled by our ancestors. Our diverse...our old heirloom varieties of grains and fruits and vegetables and such are the result of countless evolutionary experiments and they are the successful results of those experiments. So we have much to learn and I don't think we're going to have a substitute for this diversity anytime soon.

PALMER: How much genetic variety have we actually lost?

FOWLER: I don't know how much variety or diversity we've lost because frankly we never had a headcount on it to begin with. We do have some records, at least in reasonably modern times. If you go back to the 1800s, the US Department of Agriculture was essentially doing a census of the varieties of fruits and vegetables that were grown by American farmers and we know we've lost a great deal of those varieties. I would make a distinction that varieties and diversity aren't quite the same thing because you can have a trait that appears in more than one variety of apple, for example. So losing a variety of apple doesn't mean you've lost that trait necessarily, but in some cases of course it would.

PALMER: Are you still collecting? Are there any other seeds you would really like to get?

FOWLER: Absolutely. There's always more diversity out there. Diversity is cropping up all the time so this task will never really end. We would like to get more of the wild relatives of our domesticated crops, they're pretty tough plants and in a situation where the weather is bad or there's global warming, those kind of traits are really interesting and useful for agriculture. Some of the very minor crops, we don't have good collections of some of those so I'd like to add to those, and there are a few countries that haven't participated in the seed vault yet. It doesn't mean that we don't seeds that were collected by other institutions in those countries, but we don't have those country’s collections as well so we want to add China and India and Ethiopia, Iran, to that list, of course.

The seed vault is tucked into a frozen mountainside on the Svalbard archipelago. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

PALMER: When you say minor crops, what are you talking about?

FOWLER: Some of the vegetables, for instance, there's a whole category of African leafy vegetables. There are minor crops that you probably never would've heard of, I mean, Bastard Cabbage and Mormon tea and Love Lies Bleeding and Cheesy Toes, maybe these are forage crops but these are exotic names and I don't really know much about those as well, but we could use some more diversity of things like that.

PALMER: How long will the seeds stay viable in the vault?

FOWLER: It depends on the species. At the short end, some species would be fine for maybe 7,500 years or more. Our major grain crops, if you look at rice or wheat, barley, those should be viable somewhere between one and 2,000 years from now. Sorghum we estimate would be viable more than 19,000 years from now. Having said that I would add that this is not a time capsule, so yes eventually, even if eventually is 2,000 years from now, the seed will lose its ability to germinate. But what we've tried to do with the seed vault is to establish a facility whose conservation standards are equal to or better than any of the depositing institutions. So, in other words, the seeds in the seed vault will decline in their germinability no more quickly than those in in the best seed banks around the world and those seed banks monitor their seed supplies all the time so when they see that a seed sample is declining in its viability, they will take some seats outgrow them in the real world, multiply them and when they do that they'll send more seed to the seed vault. It's a living facility and will always have seed coming in.

PALMER: So it's constantly being replaced as it were. Does it also work as a kind of lending library of seeds?

In 2015, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) became the first seed bank to withdraw seeds from the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Conflict in Aleppo, Syria forced the organization from its facility there. (Photo: Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

FOWLER: That's a good analogy. It is a library but the lending library portion of it really is up to the depositing institutions. It's pretty impractical to go to the North Pole or Svalbard to get seeds if you need them for a research project or plant breeding, so you would go to the normal national seed bank or one of the international research centers to get the seeds directly there. This is the backup, this is the insurance policy for all of those, but mostly we built the facility not thinking about doomsday or anything like that. That word doesn't appear in any of the planning documents. We built it because doomsday really occurs on an almost daily basis and one of the hundreds of seed banks around the world where they're losing a sample here and there, and that might be the sample that not just that country but all of humanity needs for that particular crop. By the way, we have had our first withdrawal of seeds and that was both a sad and a happy occasion. It was sad that the withdrawal needed to take place. It was happy that we had the backup copy so the collection in question wasn't lost.

PALMER: So, who needed to withdraw seeds?

FOWLER: There was a wonderful international institution located outside of Aleppo, Syria, with the acronym ICARDA, the International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas. This was not a Syrian facility, this was an international facility and they specialized in conserving and breeding wheat, barley, lentils, chickpea and a wonderful crop called grasspea or Latherous, major suppliers for farmers in that region particularly working on drought tolerant varieties which are of course very important and food security in the Mideast is of global importance.

So when the war came to Syria the researchers had to abandon their research station, but fortunately we had anticipated that there might be a problem then we worked with that institute to get a spare copy of all their seed samples out of Syria and up to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault before the fighting really started, and they reestablished their center in Morocco and Lebanon and of course they don't have access to the seed bank in Syria any more so they really needed to start to get their seed supplies back and we shipped them back in September 2015, and they will multiply those seeds and they'll start to use them again in their own research project and then as you can imagine they will be rather highly motivated to send us a copy back again.

Old coal transport infrastructure contrasts with the ice and snow of the mountains near the town of Longyearbyen, Norway. Coal is plentiful in the Svalbard archipelago and powers the seed vault. (Photo: Mari Tefre)

CURWOOD: That's Cary Fowler, author of "Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault" talking with Living on Earth's Helen Palmer. Cary Fowler insists Svalbard is not a Doomsday Vault – and though there was a scare in October of 2016 when usually heavy rains and high temperatures resulted in meltwater leaked into the outer tunnel, the Norwegian Government says none of the seeds were ever at risk.

Related links:

- Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault

- More about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault

- CNN: About ICARDA’s withdrawal of seeds following its move from Aleppo, Syria

[MUSIC: Ravi Shankar and Philip Glass, “Meetings Along the Edge” on Passages, composed by Ravi Shankar, Private Music, distributed by BMG]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with sounds of the Earth…

[SOUNDS OF RUMBLES AND BURPS]

CURWOOD: These are Earth sounds as you’ve probably never heard them – sped up 10,000 times and transposed up about 13 octaves…

[MORE EARTH SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: The sounds come from seismic recording stations in North America and Central Asia –

[MORE EARTH SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: The frog-like burbs you can hear are earthquakes, large ones followed by the chirps of aftershocks.

[MORE EARTH SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: John Bullitt created this unusual soundscape of our solid, restless planet for the CD Earth Sound.

[MUSIC: Natraj, “Introduction” on Deccan Dance, composed by Jerry Leake, Galloping Goat Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Matt Hoisch, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Helen Palmer, Olivia Reardon, Rebecca Redelmeier, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth