October 20, 2017

Air Date: October 20, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Global Warming Minefield

View the page for this story

These times of deadly hurricanes, firestorms and severe drought are linked to global warming, with the prospect of unpleasant surprises ahead. Penn State climate scientist Michael Mann explains to host Steve Curwood that the risk is not so much a single tipping point but rather ‘unknown unknowns’ with the power to disrupt, like a secret minefield. Known dangers include rising sea levels from ice loss and higher energy storms. (14:00)

Puerto Ricans Flee Maria For Florida - Where They Can Vote

View the page for this story

Much of Puerto Rico’s water and power systems are still broken after the destruction of Hurricane Maria and while tough economic conditions on the island have stimulated migration to the mainland over the past decade, the devastation of hurricane has turned this flow into a torrent. Thousands are heading to Florida and as they move in, their climate-related migration is coming with political implications. Puerto Rican voters have leaned Democratic in recent state-wide and presidential elections when the winning margins have been roughly 1%. The Director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, Edwin Meléndez, and Professor of Government and Politics at the University of Southern Florida, Susan Macmanus, join host Steve Curwood to analyze the impact of these newcomers on this major swing state’s politics. (06:00)

Republicans Move to Open Arctic Refuge For Drilling

View the page for this story

Fierce debate over drilling for oil in ANWR, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is decades old. Now the possibility is closer to becoming a reality, with a rider on budget measures passed by the U.S. House and Senate. Host Steve Curwood discussed the developments and drilling prospects with Alaska Dispatch News reporter Erica Martinson. (09:00)

BirdNote®: Here Come the Merlins

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

The Merlin is one of the world’s smallest falcons yet it’s something of a trailblazer. Rising global temperatures are forcing species to head north, but as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports, these adaptive predators have begun to move south to occupy the abandoned homes of other avian migrants. (02:00)

Rough Riding for Wild Horse Country

View the page for this story

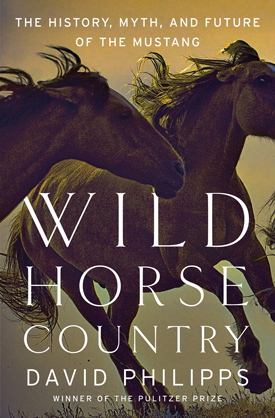

Tens of thousands of wild horses, or mustangs, still roam the vast, undeveloped public lands of the American West. Cattle ranchers argue the horses’ booming population threatens their livelihoods, and the health of the rangeland. But the public generally opposes any plans to send wild horses to slaughter. Author David Philipps’ new book, Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the Mustang tells the story of a tough survivor that defies the efforts of cash-strapped government agencies to control it as it continues to live up to its reputation as “the one that got away.” (16:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Mann, Susan McManus, Erica Martinson, David Philipps

REPORTERS: Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Devastating fires, monster hurricanes, biblical floods. These disasters alert us to more dangers as global warming accelerates.

MANN: There isn't one tipping point, there isn't one cliff that we go off. It's more like we're stepping out onto a minefield, and we don't know exactly where those mines are, but the further we step out into that minefield the more we warm the planet, the more likely it is that we do set off these mines.

CURWOOD: Also, a dilemma. Mustangs continue to roam the west by the tens of thousands.

PHILIPPS: The wild horse has become this divisive symbol. It once was sort of this universal symbol of American grit, but now for a lot of rural communities it is a symbol of federal interference, crazy ideas from city slickers that are imposed on them, and it affects policy in a big way.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

The Global Warming Minefield

Fire-destroyed homes as viewed from a helicopter over Santa Rosa, California. (Photo: The National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Record breaking Atlantic hurricanes and storms, reaching from Texas to Ireland, along with record firestorms in California linked to record drought raise the question of whether the Earth moved this year into another phase of global warming. And some wonder if climate disruption is slipping into a runaway trajectory that feeds on itself.

Well, for insight, we turn now to leading climate expert Michael Mann at Penn State University. Welcome back to Living On Earth, Michael.

MANN: Thanks, it’s great to be with you.

CURWOOD: So, this season we've seen a rash of all these hurricanes, really intense fires. To what extent, then, do you think we should view these events as our new normal?

MANN: Well, unfortunately, it's worse than a new normal because what we're seeing is the veritable tip of the iceberg, and if we continue on the path that we're on, there's no reason not to expect that we will see even more intense hurricanes and more extreme weather events of the sort we're already starting to see, unprecedented flooding events, unprecedented heat waves and droughts and wildfire, which is a consequence of heat and drought, and if we don't do something about the problem and get our carbon emissions under control, we have every reason to expect that we will see even more devastating and extreme events.

CURWOOD: So, how much is this year an outlier for hurricanes?

MANN: Well, you know, the sort of season we're seeing isn't unprecedented. We saw a similarly active season in 2005, and of course, that gave us Katrina and Wilma and just a number of devastating storms. There are aspects of what we're seeing now, however, that are unprecedented. Irma, for example, was the strongest hurricane as measured by peak sustained winds ever in the open Atlantic. Ophelia, the first category three hurricane to make it as far east as it made it.

One other thing, over the last few years, we have seen record global ocean temperatures, and during that time period we've seen the strongest hurricane on record, that was Hurricane Patricia a couple of years ago in the Pacific. The strongest storm in the northern hemisphere, that was Patricia. The strongest hurricane in the southern hemisphere, that was Winston, and now with Irma, the strongest storm ever in the open Atlantic. It's not a coincidence as these ocean temperatures continue to warm, we are going to see the strongest storms get stronger.

CURWOOD: People worry about tipping points beyond which there is no return, at least in terms of human lifetimes. What of those, if any, have we reached?

As Texans dealt with Hurricane-induced flooding in September, monsoon floods ripped through much of Bangladesh. (Photo: Amir Jina, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MANN: Yes, this notion that's very widespread that there's some tipping point, that once we warm the planet enough, once we put enough carbon into the atmosphere, we sort of go off this metaphorical cliff. In reality, it's much more subtle than that. There isn't one tipping point. There isn't one cliff that we go off. It's more like we're stepping out onto a minefield, and we don't know exactly where those mines are, but the farther we step out into the minefield, the more we warm the planet, the more likely it is that we do set off these mines, that we do encounter devastating tipping point-like changes in the climate, and I'll just give you one example.

One of those tipping points is the melting of the ice sheets. Once we set in motion the melting of the West Antarctic ice sheet, once we set in play the destruction of the Greenland ice sheet, then we commit to 30 feet, potentially, ultimately of global sea level rise that would be devastating, and one of the things we're learning is that there are other tipping points that might it create. Once we dump a whole lot of fresh water into the North Atlantic, there's the potential to shut down this ocean circulation pattern that we call “The Great Conveyor Belt”. It was popularized in the movie, "The Day After Tomorrow," and while very little of what was portrayed in the movie is likely to happen, if we were to shut down that ocean current that could have a devastating impact on fish populations. You know, the North Atlantic is one of those productive marine environments in the world, and we would lose that productive population of fish that we rely on. There's some emerging evidence that if that ocean circulation pattern were to shut down, you could actually get even more warming in the tropical Atlantic, in the Caribbean, and ironically further intensification of those hurricanes that we've been talking about.

CURWOOD: Now, one thing about the El Niño, the El Niño southern oscillation you guys call this as scientists, is that when it's operating it tends to blow off the top of the hurricanes for the east coast of the US, and you don't get them. So, it would be nice to keep that system going. How we doing in terms of not disrupting the El Niño? I know it's selfish, it's mostly about North America, but hey that's where we live.

MANN: It's a great question and, in fact, El Niño influences not just North America but Africa, Australia, India. It is perhaps the most influential natural climate phenomenon, and it has a profound impact on regional weather patterns. That's going to impact climates in regions around the world, sometimes in very detrimental ways as you allude to. El Niño can sort of be a good thing when it comes to Atlantic hurricanes. El Niño years tend to be years where there's more of what we call “wind shear,” variations in the winds with altitude, and when you have that in the atmosphere, that's adverse to the formation of a hurricane. A hurricane likes to have a nice vertically stacked pattern. So, El Niño is a good thing from that standpoint.

Now, there is a debate within the scientific community, and this is a real debate, it's not a fake debate like, “Is climate change real, or is it human caused?” Those are settled matters. But how will El Niño change because of global warming. That's still a debated proposition, and there is an agreement among the various climate models that scientists use when it comes to what will happen to El Niño. There is some evidence that climate change, counter-intuitively, could actually cause the climate in some ways to look more like the flip side of El Niño, La Niña. La Niña is when the eastern tropical Pacific is actually cooler than usual, and it tends to have the opposite impacts from El Niño. So, La Niña years tend to be dry in the western US, and they tend to be active hurricane years because there's less of that wind shear in the atmosphere.

If climate change, as we've speculated, does lead to a more La Niña-like state of Earth's climate, that could mean that the impacts, when it comes to Western drought, will be worse than the models currently tend to forecast. It could mean that the intensification and increase in activity when it comes to Atlantic hurricanes could be worse than the models currently project. So, it underscores a very important principle here. Yes, there's uncertainty when it comes to some of the details about climate science, but uncertainty is not our friend here, and if it turns out that we are in store for a bit of a surprise, a more La Niña-like future, well, then things would be worse than we currently project.

Citizen Soldiers alongside residents of the municipality of Cayey conduct a route clearing mission after the destruction left by Hurricane Maria through Puerto Rico. (Photo: The National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: As of right now, how much in terms of global warming gases is in the atmosphere? Where are we?

MANN: Pre-industrial levels of carbon dioxide were about 280 parts per million. We have now passed about 410 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere. That level of CO2 in the atmosphere is unprecedented for millions of years. Now, if you add together all the other greenhouse gases - the methane, nitrous oxide, ozone, which is a pollutant but it's also a greenhouse gas, chlorofluorocarbons, the same molecules that were destroying the ozone layer and were banned, those are also greenhouse gases. If you sort of lump them all together, then the equivalent amount of CO2 is more than 450 parts per million in the atmosphere. But here's the key number. We're at about 410 parts per million actual CO2 in the atmosphere. If we cross about 450 parts per million CO2 in the atmosphere - just CO2 alone - that's where we most likely commit to catastrophic warming of more than two degrees Celsius. And again, there isn't one tipping point. Like I said, it's a minefield, but once we warm the planet more than two degrees Celsius, three-and-a-half Fahrenheit, relative to the pre-industrial, that's when we start to run into the most dangerous mines that are in that minefield.

CURWOOD: Professor Mann, how are we doing in terms of keeping global warming below two degrees centigrade, three-and-a-half degrees Fahrenheit? What needs to change to stay below that threshold, and what do you think of that threshold anyway? How safe would we be?

MANN: Yeah, well, you know, if you're somebody in Bangladesh right now, if you live in the Caribbean islands, if you live in Puerto Rico, if you're a farmer in California, dangerous climate change has already arrived. So, it's somewhat of a fallacy when we talk about dangerous climate change being at the level of two degrees Celsius warming. We've warmed the planet a little more than one degree Celsius, about a degree and a half Fahrenheit thus far, and we're already seeing dangerous impacts on climate. If you live in a low lying Pacific Island, two degrees Celsius warming is way too much. Your home is gone. Your island is gone. So, two degrees is really a number that has been set as more or less a political consensus as to what is viewed as achievable.

So, how are we doing with respect to that challenge? Well, that's where there's a little bit of good news. Global carbon emissions have actually flat lined for the last three years. They haven't grown, even as the global economy has continued to increase. That suggests that we're starting to see this separation between economic growth and carbon emissions, this decoupling of our economy from carbon emissions, and that's attributed to the dramatic growth in renewable energy around the world.

Well, that's not enough. Flat lining our emissions means we continue to put 30 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere every year. So, as long as we're flat, we're still loading the atmosphere with carbon. We've got to bring those emissions down to zero, and the irony is that if we had acted decades ago when we knew there was a problem, that emissions curve, we would be coming down a bunny slope. Now, instead we've got to come down the black double diamond slope. We've got to bring those emissions down very dramatically, and that's going to take action that goes beyond the commitments of the Paris agreement. At the next major conference of the parties, the participating nations of the world will need to ratchet up their commitments.

Michael Mann is Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University. (Photo: Penn State University)

CURWOOD: Michael, in the past you've referred to Mr. Trump's attitude towards "post-truth politics" as really dangerous in terms of our ability to fight climate disruption. How do we avoid some of these difficult scenarios with a president who’s in the process of trying to take us out of Paris and really not acknowledging the risks to our national security, indeed, our survivability from climate disruption?

MANN: Yeah, it's a challenge. There are really a couple things here. First of all, there will be a referendum on the direction that this country has taken under Donald Trump in less than a year, and, you know, if we want enlightened policies when it comes to issues like climate change, we have to elect enlightened politicians. And so, people need to get to the voting booths. If you don't like the direction that things have taken now when it comes to climate change and a host of other issues, you have the ability to express your voice at the voting booth. Ironically, not just the past administration but over the past half century, environmental protections that were put in place by Republican and Democratic presidents alike are currently being dismantled under the current administration, and that's unprecedented.

The carbon reductions that we can expect in the years ahead based on what states and municipalities are doing and based on the trends in the energy market and the rapid increase in renewable energy and electric vehicles, it looks like we will meet our obligations under the Paris Treaty with or without Donald Trump behind it, and so that's good news. Now, the bad news is, just imagine what we could have done given that all that. Just imagine what we could have done if our president had sought to build on the successes of the prior administration rather than try to dismantle them. Some amount of progress inherently will be lost because of the different direction that this administration has taken, and the lack of leadership in Congress to do something, but, again, in less than a year we've got an opportunity to change directions.

CURWOOD: What new research leaves you optimistic about our ability to manage what's coming in terms of climate disruption?

MANN: Well, we've done some research ourselves on what reductions in carbon emissions are necessary to avoid dangerous planetary warming. The good news is that there still is a carbon budget. There's still a certain amount of carbon we can afford to burn and remain below that sort of two degrees Celsius, three-and-a-half dangerous threshold. Dangerous in some generic sense, as we said before, in many places we're already seeing the dangers. But if that's the goal and that seems to be the goal that's been agreed upon by the nations of the world, we can still do it, and our own studies show that there is a path forward.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science and Director of the Earth Systems Science Center at Penn State University. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

MANN: Thank you, Steve. Always a pleasure.

Related links:

- Michael Mann’s website

- Common Dreams: “Four Years Ago Puerto Rico Warned of “Climate Tipping Points” – Did Anyone Listen?”

- FEMA Climate Change Facts

[MUSIC: Huancara, “La Telesita” on Sounds Of Indian Summer – Contemporary Native Music From the National Museum Of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution.]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how climate change is spurring migration inside the US. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jessica Martinez Maxey, “All My Blessings”]

Puerto Ricans Flee Maria For Florida - Where They Can Vote

After Hurricane Maria, residents near Utuado, Puerto Rico were stranded due to severely washed-out country roads. The path to full economic recovery for the island is similarly long and winding. (Photo: Coast Guard News, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Weeks after Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico, much of the island remains without water or electricity, and now it’s beginning to lose another valuable resource, its people.

MELENDEZ: What our data suggest is that between 100,000 and 200,000 people will leave Puerto Rico this year. Half that flow will go to Florida, even more than half.

CURWOOD: Edwin Meléndez directs the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College.

MELENDEZ: That exodus is going to continue for a few years. Over the last 10 years, more than half a million Puerto Ricans migrated so we can safely talk about the depopulation of Puerto Rico nowadays.

Edwin Melendez is a professor of Urban Affairs and Planning at Hunter College and the Director of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies. (Photo: Center for Puerto Rican Studies)

CURWOOD: As Puerto Ricans are US citizens, Florida’s election watchers see that influx as a possible curve-ball to politics in the swing state. Susan McManus is a Professor of Government and International Affairs at the University of South Florida in Tampa.

MCMANUS: We are the state that’s long been known as an immigrant magnet state, particularly for Puerto Ricans. There are large concentrations of Puerto Ricans in our state and have been for quite some time.

CURWOOD: Now, with 100,000, perhaps 200,000 more Puerto Ricans, that he says that next year probably more of the same, how will this influx of Puerto Ricans from the island to the mainland where, of course, they can immediately register to vote, how might this affect the balance of power between Republicans and Democrats? I'm thinking particularly about the statewide elections, for example presidential and gubernatorial and senatorial elections where they have been some razor-thin margins.

MCMANUS: Absolutely. For the last four elections, two governor's races and two presidential races, the margin of victory in our state as just been one percent. We're known as “the one percent state”, and a lot of it has to with that people come from all over, including other countries, and of course, Puerto Rico. Only about a third of the people who live here were born here.

CURWOOD: So, how would you characterize politically, the recent migrants coming from Puerto Rico into Florida?

MCMANUS: Historically, what's happened is, people who have come straight from the island have really not have strong party attachments, and they have been very up for grabs by most parties and particularly influenced by adept campaigners who can speak Spanish. I go back to the days of Jeb Bush who did well among the Puerto Ricans and Marco Rubio as well.

While southern Florida has long been home to the state’s politically influential Cuban American communities, central Florida, which includes Orlando (above) is seeing the greatest growth in Puerto Rican demographics. (Photo: Jeff Krause, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

But there are also those who come to Florida via the northeast, go from the island to New York and New Jersey down to Florida. They are staunchly Democrats. But more recently we see that young Puerto Ricans are leaning more independent, but if they have a choice and it's party-intensive, they lean more Democratic. The Puerto Rican population coming here is fairly young, and so Democrats right now are salivating. They see a terrific opportunity to register all the new arrivals, and Republicans are very worried because we are a one percent state.

CURWOOD: Now, there are a number of factors in a number of races, but if you were to look ahead to the presidential race, and should President Trump be running, I would think that the Puerto Ricans who have had to leave the island in a relative hurry...well, they might be as mad as heck.

MCMANUS: That's certainly what Democrats are counting on, and it's why they are already aggressively organizing registration drives for people who arrive here. We have, for example, right on the heels of the terrible hurricane, around 35,000 Puerto Ricans and more are coming every day, but there's already talk of some wanting to return again. So, you know, we don't know the net figure, but Democrats see this as a golden opportunity, knowing that the demographics of this state are changing and the Hispanic vote is very important.

Susan MacManus is a distinguished professor of Government and Politics at the University of South Florida. (Photo: Florida State University)

CURWOOD: So, how does the environment affect voters there in Florida?

MCMANUS: It's interesting that you ask the question because just yesterday we released a USF/Nielsen Sunshine state survey of 1,200 Floridians, and the topic was the environment, and the question was "What is the biggest threat to the environment in Florida?" And it varies tremendously from what part of the state you're talking about. For example, concern about rising sea levels is very intense in the heavily populated southeast part of the state and it shows up as the number one issue in both the Miami, Fort Lauderdale and Palm Beach media markets. Whereas, in other parts of the state they are more invasive species. In other places, it's the Lionfish that has come in, and in some places it's related to the Everglades.

So the environment is a big issue in Florida, but if you just say climate change by itself, the really significant thing is that the group of voters that are most engaged and driven by that wording are the young millennials. And many people do not realize that Florida is no longer just a retiree state. In 2016’s election cycle, 50 percent of Florida's voters were either millennials or GenExers, and they are what we are calling “the environment generation”.

CURWOOD: Susan McManus is a Distinguished Professor of Government and National Affairs at the University of South Florida in Tampa. Thank you so much, Professor for taking the time with us today.

MCMANUS: I appreciate it being on your very, very powerful program. Thank you so much.

Related links:

- NYTimes: “An Exodus From Puerto Rico Could Remake Florida Politics”

- State of Puerto Ricans 2017 Study (Edited by Edwin Meléndez)

- Center for Puerto Rican Studies

- About Edwin Meléndez

- About Susan MacManus

[MUSIC: Luis Fonsi, “Despacito” on Despacito and My Greatest Hits, featuring Daddy Yankee, by Luis Rodríguez/Erika Ender/Ramon Ayala, Imports Records]

Republicans Move to Open Arctic Refuge For Drilling

The Porcupine Caribou herd is one of many species that rely on the coastal plain section of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to breed and migrate through. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The massive Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, ANWR has the largest variety of plant and animal life of any protected area north of the Arctic Circle, including vast herds of migrating caribou, as well as countless birds, wolves, muskoxen and grizzly bears. But seismic tests also promise billions of barrels of oil under ANWR, and the US House and Senate have now advanced separate budget resolutions that would effectively open up its pristine coastal plain to drilling. Efforts to open ANWR have gone down to defeat many times since the 1980s, but this year could be different.

To untangle what’s going on, we called up Erica Martinson, Washington DC-based reporter for Alaska Dispatch News. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Erica.

MARTINSON: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, first describe the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for us, especially what is known as section 1002.

MARTINSON: Well, the refuge commonly known as ANWAR, is in the far north of Alaska, and it is 19 million acres large. I mean, this is no small place. The 1002 area, that refers to a section of the law in the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, it’s one and a half million acres. A small section of is believed to have a great amount of oil there, and when they set aside the refuge for protection in 1980, the law sectioned off this small bit, the 1002 area saying that maybe in the future there could be drilling there, but first we need to check it out, you need to decide how much is there, then you need to do an environmental impact statement, and then it's going to take an act of Congress, and that last part, the act of Congress has been something that they've been fighting over for the last three to four decades now.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand with the question of drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge back on the table that the indigenous folks there, the Gwich’in have come to Washington to make a point. What are they saying is the problem for them?

MARTINSON: Well, they visit quite often because this fight is always going on for Alaskans. They say that this is a sacred land and that there should never be any drilling there, and they're worried about going into areas that mean a lot to them as native Alaskans.

CURWOOD: So, as a Capitol Hill reporter you have to give us now a lesson in legislation. As I understand it, the resolutions that are being offered here, they are budget resolutions and actually nowhere if you look closely, do you see the words Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. What is going on with these budget resolutions that do involve the area?

MARTINSON: Right, as it turns out it says nothing about ANWR, it says nothing about drilling. What's going on is a lot of listeners may be now familiar with the budget reconciliation after the Senate recently attempted to use the fiscal year 2017 reconciliation to pass health care reform. Their next plan is now for the 2018 budget reconciliation to pass tax reform. By using this, they set up a budget that shows just the basic outlines of where they're going to get what money, and that only requires a simple majority. They don't need a filibuster-proof number of senators to vote for it, which is a tough call these days in the Senate as there are only 52 Republican senators. They just need 51 to pass anything that they've got done on the budget resolution. Turns out that wasn't enough for health care, but we'll see how it goes for tax reform. So, this is just a provision that's going to change the political calculus here because it's not fully about ANWR, this is going to be about tax reform and about whether or not ANWR is a big enough issue to pull away some Republicans.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is a 19-million-acre area of protected land in northern Alaska. The refuge, which is projected to have billions of barrels of oil lying beneath its surface, has been the focus of contentious debate about whether to allow drilling for that oil. (Photo: Thayer A. / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: So, Erica, tell me, how could these budget resolutions lead to oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge?

MARTINSON: Well, in both the House and the Senate the resolutions offer instructions for committees to find revenue. In the House, they asked the House Natural Resources Committee, that's Alaska Congressman Don Young's home committee, to find five billion dollars in revenue. They say that they're going to do that through a provision that allows drilling in ANWR. In the Senate they've asked Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski's energy natural resources committee to find one billion dollars in revenue, and it's well known to everyone around on Capitol Hill that her number one way for doing that is going to be drilling in ANWR.

CURWOOD: By the way, how could drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge generate that kind of money for the federal budget? If you're going to raise a billion dollars, you know a medium lease is, what, 30 or 40 or 50 dollars proposition on the land. How do you get to a billion dollars even? Certainly how to get to $5 billion?

MARTINSON: There's certainly some question about that, especially since the last time they did any real seismic testing in the area to see how much oil we're talking about was in the '90s. About 10 years ago, the National Budget Office projected that drilling in ANWR could raise about five billion dollars for the federal government, and so that's part of what they're going off of. Now, those numbers obviously were at a time when oil was worth a lot more. Your cost per barrel now is not going to get anywhere near that, and so I think that's where they scaled it back on the Senate side and said we could do one billion. So, it's definitely a volume issue.

CURWOOD: What do you see as the political factors at play in terms of this budget resolution ultimately being passed or not?

MARTINSON: Well, there's definitely plenty of opposition in the Democratic Party, but they're opposing this tax bill anyways. So, the question is, where your Republican senators who have been opposed to ANWR drilling in the past are going to land and whether or not this provision is important enough to them to tank tax reform. Now, I talked to Alaska senator Dan Sullivan recently and I asked him, “What are you telling your colleagues about this ANWR fight? What are you doing to try and convince them that they should do this now?” And he was telling me they the fight he's making now is that things have changed in the last 20 and 30 years. When we were originally talking about drilling in ANWAR, the footprint of these oil drilling operations was much larger, and with things like fracking now, you're looking at a much smaller oil heads, you're looking at a less impactful process, doing less to the surface of the land to get to what's underneath it, and also the argument that there are drilling operations only a couple of miles away from the 1002 area of ANWR.

Republican Senator of Alaska Lisa Murkowksi has long supported oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: UAF School of Management, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, today's oil price is relatively low. Why are proponents of drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge pushing for it now when it's questionable how economic it would be?

MARTINSON: Well, the answer to that is because they're pushing forward always.

[LAUGHS]

It's not the best time obviously, financially, but they say that this is the biggest chance they have. You know, Republicans have the House and the Senate and the White House and a president who has very clearly said he wants to open up Alaska for oil drilling, open it up for business, and the Senators and Congressman from Alaska have been trying to do this for decades. It's been something that they've never backed away from, and if they have an opening they're going to take it.

CURWOOD: And what do the opponents say? Who are they and what do they argue?

MARTINSON: Well there are I think 40 Democrats who joined in on a bill earlier this year in the Senate arguing that they should never open up ANWR. There are some Native groups in Alaska who are opposed to it and they argue that this is a sacred area for many Native people, and they argue that it's a very key environmental area, that if you were to go in and drill oil that you're just not going to get it back, that this was set aside by Congress for a reason, and we shouldn't go back on that.

CURWOOD: So, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is considered the largest remaining wild part of America. So, what are the potential environmental impacts of drilling for oil there?

MARTINSON: Well, they’re the impacts that there are always for drilling. You're going to have to disturb the area with human activity, with trucks, with moving things towards a pipeline. They're talking about pulling out up to 16 billion barrels of oil, so it's not without impact on the animal and wildlife there, particularly the Porcupine caribou herd, and if you interrupt that area it could have a serious detriment to the environment there, and to subsistence living for the Natives that live there.

CURWOOD: To what extent do opponents make the "keep it in the ground" argument, that in this age of climate disruption as a year that we've seen some crazy storms and fires that it makes no sense to go get more oil when there's already plenty available.

MARTINSON: That's certainly a big part of the argument. I mean, it's not projected that taking this oil from ANWR will actually affect the world oil price even. We're not talking about an amount that is life changing for most Americans at the pump. It could make a big difference for Alaska's economy but not outside of the state necessarily, and if you're looking to avoid drilling more oil and adding to the problem of climate change then it doesn't make sense for you to open up more areas or oil. To the contrary others argue that Russia is expanding its Arctic drilling, and if you don't allow companies to do it here they'll do it there.

CURWOOD: Erica Martinson is the Washington D.C.-based reporter for Alaska Dispatch News. Thank you, Erica.

MARTINSON: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Erica Martinson for Alaska Dispatch News: “US House passes budget bill that provides option for opening ANWR to drilling”

- The Wilderness Society: “The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge”

- Alaska Dispatch News: U.S. Senate passes bill that offers a chance to open Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling

BirdNote®: Here Come the Merlins

The Merlin may be small, but it packs a serious punch. In Medieval times, nobility used the bird to hunt sky larks. (Photo: Greg Thompson)

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: They are tiny birds, but tough ones.

And they are flying against the trend of wildlife moving toward the poles as the planet warms, as Mary McCann tells us in today’s BirdNote®.

[BirdNote®]

Here Come the Merlins

[Merlin calling, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/197047, 0.19-.22]

MCCANN: Want to see one of the blazing thunderbolts of the bird world? Smaller than a pigeon — but fierce enough to knock one from the air — are the powerful, compact falcons known as Merlins.

While global climate change is pushing ranges of many birds farther north, Merlins are actually expanding southward.

The Merlin’s migratory patterns actually run counter to the direction of rising temperatures. Scientists have found that these small predators are nesting further south, even as most birds are moving north. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

Merlins nest in northern forests around the world. But in recent years, more and more Merlins have been nesting farther south, in towns and cities across the northern United States. These small falcons will take over old crow nests, especially in conifer trees — in parks, cemeteries, and neighborhoods.

[Merlin calling, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/197047, 0.19-.22]

No one knows precisely why, but part of the answer may lie in a rebound of Merlin populations since the banning of pesticides like DDT. And it’s a reminder that bird behavior may be more flexible than we sometimes imagine.

[Merlin call, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/105837, 0.15-.17]

Merlins reach their peak southward migration in October. Although some, like those in the Pacific Northwest, remain year round, most scatter to the south for winter. Some travel as far as Ecuador.

With any luck, you might see these adaptable, pint-sized thunderbolts in your neighborhood.

[Merlin call, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/105837, 0.15-.17]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by Bob McGuire and Geoffrey A Keller.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org October 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

Sources: http://www.hawkmountain.org/raptorpedia/hawks-at-hawk-mountain/hawk-species-at-hawk-mountain/merlin/page.aspx?id=503

http://www.fllt.org/the-mysterious-merlin/

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Merlin/lifehistory

http://birdnote.org/show/here-come-merlins

Related links:

- The “Here Come the Merlins” story on the BirdNote® website

- About the Merlin from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

[MUSIC: Jorge Ball, “La Marusa”]

CURWOOD: Coming up, roping in the wild horses that roam what’s left of America’s Wild West. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to “The Race to 9 Billion” podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jorge Ball/Inti-Illimani, “La Marusa” on Imaginacion, EMI Import]

Rough Riding for Wild Horse Country

Wild horses run free after being released back onto the Nevada range by the Bureau of Land Management during a roundup or “gather” in February 2017. (Photo: Kyle Hendrix/BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WLoYFvbR0XY

[MUSIC: Roy Rogers, Don’t Fence Me In]

The King of the Cowboys there, Roy Rogers, with the stuff of romantic legend, the freedom of the endless fenceless prairie, the cowboys, and doggies and wild horses by the millions running free. As the Wild West was tamed, mustang numbers declined and some were even rounded up for meat. A public outcry stopped that and now the wild horse herd is growing, to more than 70,000 at the latest count. A book, "Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the mustang", explores the controversies around this iconic animal and its future. David Philipps is the author and he joins me now from Colorado Springs. David, welcome to Living on Earth.

PHILLIPS: Thank you for having me on.

CURWOOD: So, your book is all about the mystique and the reality of the mustang. Tell me why do you think Ford Motors took the name “Mustang” for the first muscle car that they built back in the 60s? The iconic one.

Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the Mustang is David Philipps’ second book. (Photo: courtesy of W. W. Norton)

PHILLIPS: Well, so this goes back to what we think of the mustang as being. In a way, it's the most American animal. It's an immigrant. It comes from no sort of aristocratic background. It came over here as a nobody and sort of got what it got through grit, which is exactly the story that we tell of ourselves. You know, the old “up from the bootstraps” type of stuff. And so, when they built a car that was small, dependable, and fast it embodied a lot of the things that Americans at the time thought of the mustang.

CURWOOD: Of course, the mustang officially an immigrant but actually in your book you say it wasn't really an immigrant if you look back in paleo history.

PHILLIPS: Yes, so that's what's interesting about the debate over wild horses. They really spent most of their ancient history developing in North America, about 55 million years. They spread all over the world from where they developed here, and then about 10,000 years ago they disappeared right about the time that humans crossed the land bridge into North America. Then they returned with the Spanish and spread back all over the place, and the question is, if an animal was here for 55 million years, disappears for 10,0000 and then comes back, is it invasive or is it native, and should we be surprised if it spread so quickly over an area that it had evolved to thrive in?

CURWOOD: By the way, where does the name “mustang” come from?

PHILLIPS: Mustang is the word that the Spanish used back in the days when they were first moving into Texas, they had a word “mesteño” meaning a stray horse that belonged to the herders. The BLM and certainly a lot of ranchers will say these wild horses out here, “They aren't mustangs. They are just a bunch of feral ranch strays that got away”, and that is true. If you look at the genealogy of the wild horse, it's like us, it's a mix of everything. It is Spanish horses that have been here for hundreds of years. It is ranch horses that may have escaped in the 50s, and so it was always a name that meant essentially “the ones that got away”.

CURWOOD: So, you're not actually a horse guy yourself. You're not one of those folks who spent more than, you know, a few hours, I guess, in your lifetime on a horse. Why write a book about the mustang?

.jpg)

A helicopter rounds up horses in the Bureau of Land Management’s Stone Cabin Herd Management Area in Nevada. (Photo: David Philipps)

PHILLIPS: Yeah, I'm almost embarrassingly not a horse guy. All those things, like I don't know what withers or fetlocks are anything like that, but what I am is I'm a guy who grew up in the west, who loves the untamed and open nature of it, and so in a lot of ways, I saw the wild horse as an attempt for us to try to preserve that idea through federal legislation, and I saw how mixed up it got, and so I thought to myself, “OK, if you can understand the horse and what we tried to do with it and how it failed, you can probably understand a lot about how we feel about the wild parts of our country and how we can better approach trying to let them thrive”.

CURWOOD: So, why is it the fact that wild horses are roaming the West today is so contentious?

PHILLIPS: A lot of it comes down to numbers. How many horses should we have in the west? The government says sustainably we can have about 27,000. Any more than that and they are not only going to damage the range, but they're going to compete with the cattle ranchers and sheep raisers that are already there, and those folks have a very old claim on the land as well. The problem is that the government has never been able to control those numbers. In fact, in a lot of places horses are at two or three times the prescribed amount, and if you're trying to raise cattle and make a living that way you can understand that that impact would make you pretty angry. And so, in a way, the wild horse has become this divisive symbol. It once was sort of this universal symbol of American grit but now for a lot of rural communities it is the symbol of federal interference, of crazy ideas from city slickers that are imposed on them. That divide between urban and rural is certainly there, and it affects policy in a big way.

Wild horses from the Reveille Horse Management Area enter the wings of a trap during a February 2017 gather. (Photo: BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: The mustang is famous for being such a tough horse, and when the Spaniards brought the horse back to North America, Native American tribes got a hold of them. How did the introduction of the horse by the Spanish change Native American tribes?

PHILLIPS: Wild horses were a sea change for tribes. Once they were stolen from the Spanish and spread through trading and stealing and warfare, they very quickly reached almost every tribe in the west and changed everything. They changed how they hunt. They changed how they moved. Because they were moving more often they changed what they lived in. All of the sudden the tepee became, you know, the dominant form of housing. It changed their songs. It changed their religion. It changed their view of the universe literally. The Navajo say that the sun is pulled across the sky by a chariot of four horses. It created entire new tribes, tribes that didn't exist before. The Comanche were a nothing part of the Shoshone, and then they decided to get horses and became one of the most powerful and feared tribes in the entire west, able to hold off both the American and the Spanish empires at once and claim most of the Southern Plains.

CURWOOD: It is interesting, you point out that at the Battle of Big Horn, General Custer showed up with a shiny thoroughbred from Kentucky and the Native Americans had mustangs and the surviving horse from that was….?

Wild foal and mare in Cold Creek, NV. In the absence of population control, wild horses are quite successful at raising young on the range. (Photo: James Marvin Phelps, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

PHILLIPS: A mustang. In fact he was a mustang who had been shot several times by arrows, and yet had a long life afterwards, and that, is really the story of the mustang in the west. There are stories from Little Big Horn or folks like Buffalo Bill of riding mustangs 100 miles at a clip and having them outrun some of the best horses. These are horses that natural selection has acted on for centuries. Anything that wasn't going to be really tough got weeded out a long time ago, and so what is left is almost the perfect horse. It may not look like much but, man, it can run.

CURWOOD: David you open your book with a visit to, well, what we think of as a round up. Briefly tell me that story, what you saw and how you felt.

PHILLIPS: Every year, in order to keep the wild horse population at a set level, the federal government removes thousands, sometimes more than 10,000 horses through helicopter round ups. The way that works is one or two helicopters will sweep across some desert valley and bring the horses into a funnel-shaped corral. When the helicopters bring them in, you see these herds pushed together and galloping, and it’s really something out of a movie, beautiful multicolored bands coursing across the sage, and then what's amazing is how quickly, once they're pushed into these corrals, these circular corrals, they sort of stop and stand around and are pushed onto semi-trucks, and the wildness is gone. It's a very efficient operation, and in one round-up, sometimes they remove 500 horses.

CURWOOD: So, what happens to these horses after they've round them up, and why are they running on them up to begin with? I mean they're wild horses, why not let them run?

PHILLIPS: The reason that the federal government rounds up wild horses is because the Wild West is not what it once was. We have scraps of it and on those scraps where wild horses live, the federal land managers have decided, well, those scraps of land can only support so many horses. That is sort of the crux of the problem of wild horses because when we remove them, we don't know what to do with them. The plan has always been to remove horses and have them adopted by people. Those people can then train the horses and use them as saddle horses, but we have never had enough people adopt, to take care of the horses that are removed, so there's literally a government surplus in wild horses.

In the 80s and 90s, and to a certain extent in recent years, the Bureau of Land Management has quietly looked the other way while people bought them and sent them to slaughter, and that's happened to tens of thousands of horses. As the public figured that out and demanded that it stop, the BLM has instead taken those extra horses and put them into what it calls “the holding system”, and the holding system is this vast network of private ranches that they pay to store wild horses at a cost of about $50 million dollars a year, making some big, already wealthy ranchers very rich.

CURWOOD: To what extent is this a program of horse incarceration?

.jpg)

A lone mustang on the open range in the Stone Cabin Herd Management Area of Nevada (Photo: David Philipps)

PHILLIPS: The holding system is certainly not the wild. They are separated by sex in these huge pastures. Now, I've got to say these pastures are great. Most of these ranches are in the Flint Hills of Kansas and Oklahoma, and they are beautiful, some of the most lush rolling grassland in the world. In a lot of ways they are much better forage than these horses could ever have out in wild horse country. I don't know if I would call it incarceration, but maybe purgatory. When I went to see these big holding pastures, the thing that struck me is, it was sort of like if you took a bucket from the Colorado River, and put it to the side, you still have the water there but the wildness, the life, is sort of gone, and in a way that that's what's there. They're waiting around to die.

CURWOOD: So, how well is the federal wild horse management program working today?

PHILLIPS: At this point the wild horse program is in a crisis. It has so many horses in storage that it can't afford to run the rest of the program. It's sort of fallen into an addict's dilemma, where an addict might want to go to rehab but can't afford it because they're spending all their money on drugs. The BLM, I think, wants to develop alternatives. The BLM wants to look at different ways that it can control horse populations besides rounding up, them up with helicopters and storing them, but it doesn't have the money because it's too busy rounding them up with helicopters and storing them.

So, now that program is grounding to a halt. They are spending so much money on storage that they can't really round up horses anymore, and so they are leaving them on the land. The government says that we should have about 27,000 horses on the land. That's what they think is sustainable over time. Right now we've got about 75,000, and it's going to go up and up because they don't have money to address the problem. So the train is about to come off the rails, and the question is, when it does, what will we do?

CURWOOD: So, David, all right, too many horses. What about birth control?

Wild horse advocate TJ Holmes, with her dart gun slung over her shoulder. She uses it to administer the birth control PZP to wild mares. (Photo: David Philipps)

PHILLIPS: Actually the BLM is doing this, and it works surprisingly well. They have a drug they use called PZP delivered by a dart that keeps mares infertile for one year. They have had this drug for 30 years. They have used it in very, very small numbers and said almost every year that they are going to roll it out in big numbers because they think that it's a great solution. But really they are stuck in a place where they don't have money to use the fertility control drugs because they are too busy storing horses. The only places that they're using fertility control drugs effectively right now are places where local volunteers have set up a program. They're doing the darting themselves, often middle-aged horse aficionados who know nothing about this but have taught themselves, and they are controlling those populations while the BLM is busy doing other things.

CURWOOD: Now, in other places - I'm thinking particularly of France where they're quite proud of horse on the menu - many other places actually send horses to slaughter who can't find an economic or an ecological niche for themselves. Why don't we do that in America?

PHILLIPS: Well, there are a number of people who have suggested that the way out of the wild horse dilemma is to just allow them to be slaughtered, and I think that, practically speaking, simply in terms of how easy it would be to do, it is maybe the easiest solution unless you consider the politics. I don't think that any in Congress, even really conservative members who have voiced support for this, would vote to slaughter tens of thousands of horses in storage because there would be an outcry. It's become so politically polarized that we don't even have horse slaughterhouses any more in the United States. There are number of American horses that get slaughtered but they're all exported to either Canada or Mexico. But I think one of the reasons for that is that we have this cowboy myth and the myth of the horses' companion. You know, we see it as a companion animal and so we would no sooner eat a horse than we would a dog.

CURWOOD: One of the most intriguing parts of your book, David, is your final chapter when you bring forth a potential, perhaps more wild solution for controlling wild horse populations, and that's bringing back mountain lions to parts of the west that the mountain lions have vanished from. Why do you think this could work?

Reintroducing mountain lions to some remote parts of the American West holds promise for controlling wild horse populations. (Photo: cohenHD, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

PHILLIPS: First of all, let me say that, if there's any wildlife managers listening right now, they have probably just spit out their coffee and are rolling their eyes because there is an orthodoxy within the wildlife management world that mountain lions do not eat horses. They can't, and they won't, and therefore to even talk about it marks you as somebody who doesn't really understand the issue.

So, that's where I started until I started actually reading the scientific literature on it, and over the decades lots of people have studied mountain lions in the west and lots of people have studied wild horses in the west and often times their research has been interrupted because too many mountain lions were eating too many wild horses. It happens over and over and over again, and it always happens in the same way. During the spring and summer when horses have their young, and they go to drink at a desert spring, the mountain lions will bound out of the brush and take down a foal, and sometimes they're taking down a foal a week, and this can have real impact on wild horse population numbers. You know, it's almost like the, the "Mutual of Omaha" movies that you see of the of the Serengeti where that where the zebra goes to the watering hole. This is our American Serengeti still at work.

CURWOOD: You talk about a person you met in the course of this question of mountain lions and horses. I believe his name is John Turner.

David Philipps is a Pulitzer Prize-winning national reporter for the New York Times. (Photo: Mark Reis)

PHILLIPS: Yeah, John Turner is a long time wild horse researcher, a biologist who's been studying horses out on the border of California, Nevada for decades, and what he realized is that even though the Bureau of Land Management was denying it was happening and no one had ever recorded it, this small population of mountain lions, maybe about six or seven, was holding a population, a herd of wild horses in check in this one valley and had been doing so for decades. For me, this was really exciting. This was a way to preserve the wildness that we wanted in the first place. When we preserve the animal wild horse, what we really wanted to preserve was that idea of liberty, of toughness, of independence, and we haven't done it because we left the wildness out of the equation.

CURWOOD: David Phillips is the author of "Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth and Future of the Mustang". David thanks so much for taking the time for us today.

PHILLIPS: Thanks for having me on.

Related links:

- Wild Horse Country: The History, Myth, and Future of the Mustang

- About the BLM’s Wild Horse and Burro Program

- National Geographic: “Can Fertility Control Keep Wild Horse Herds in Check?”

- John Turner’s research on predation of wild horses by mountain lions

[MUSIC: Minneapolis Orchestra/Antal Dorati, “Hoe Down” from “Rodeo” on Copland-Antal Dorato, composed by Aaron Copland, Mercury Living Presence Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Jake Rego engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth