December 14, 2018

Air Date: December 14, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Rules To Save The Climate

View the page for this story

UPDATE: Rules for reporting climate protection progress were adopted at the 24th Conference of the Parties (COP24) in Katowice, Poland, as almost all 190-plus countries in the climate treaty called for stronger international commitments on climate action. While many countries called for rapid climate action, a contingent including the United States downplayed new scientific research and touted the benefits of coal. From Poland Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists detailed for Host Steve Curwood how delegations responded to the challenges. COP25 will be in Chile. (09:04)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood explore some novel concepts for bringing sails back to shipping, and discuss the beginning of the end for the popular plug-in hybrid electric vehicle, the Chevy Volt. Then, they remember the iconic “Earthrise” photo, taken 50 years ago by the crew of Apollo 8, the first people to ever orbit the moon. As they entered moon orbit on Christmas Eve, they shared the picture with the world. (04:29)

Climate Action Off Track

View the page for this story

The Climate Action Tracker keeps tabs on countries’ progress towards meeting the Paris Agreement goals of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial levels or at least “well below” 2 degrees C. Its latest report finds that just two countries, The Gambia and Morocco, currently have policies to meet the 1.5-degree target. The Climate Action Tracker’s Yvonne Deng speaks with Host Steve Curwood about which countries’ pledges are “critically insufficient,” and how India is taking a low-carbon path compatible with 2 degrees. Morocco’s former Environment Minister Hakima El Haite discusses why her country’s history of addressing climate change for decades is helping it meet the Paris goals. (09:21)

Most Republicans Believe In Climate Change

View the page for this story

A recent poll from Monmouth University shows that nearly 80% of Americans believe that the planet’s climate is changing, including a majority of Republicans. But only a third of Americans believe climate change requires immediate action. Director of Monmouth University’s Urban Coast Institute, Tony MacDonald joins Host Steve Curwood to break down the numbers and discuss how Americans are changing their thinking about climate change. (08:48)

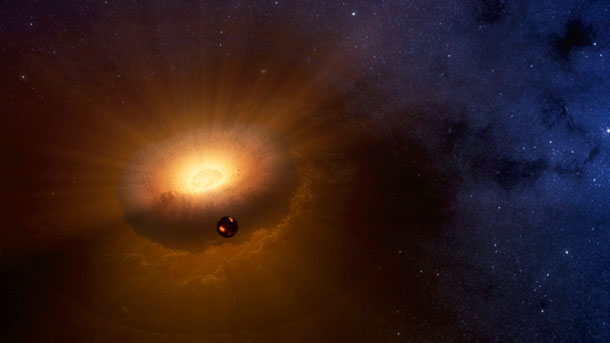

Creating The Earth And Moon

View the page for this story

University of California, Davis Professor Sarah Stewart, one of 2018’s MacArthur Fellows, is a planetary scientist trying to understand the origins of the Earth and Moon. She theorizes that the Moon and the present Earth actually came from the same vaporized cloud of rock from a gigantic celestial collision, which she calls a synestia. Prof. Stewart spoke with Host Steve Curwood about her research and about pursuing her early dream of becoming a scientist. (10:37)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Yvonne Deng, Hakima El Haite, Tony MacDonald, Alden Meyer, Sarah Stewart

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

As nearly 200 nations gathered in Poland to work out rules for the Paris Climate Agreement, countries were urged to stop stalling and move forward while there is still time.

BAINIMARAMA: Act now with courage and resolve, or God forbid, ignore the irrefutable evidence and become the generation that betrayed humanity and our responsibility to future generations.

CURWOOD: And while the Trump Administration drags its heels, polls show the vast majority of Americans believe climate change is real.

MACDONALD: We really saw a huge jump in the last three years in the number of people who believe in climate change, and that was bipartisan. However, there's still a huge disconnect between the seriousness of the problem, and the need to take action, which most of the respondents think doesn't have to happen for ten, or fifteen years.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Rules To Save The Climate

Greenpeace activists project the words “No hope without climate action” on the roof of the COP24 conference venue in Katowice, Poland. (Photo: Greenpeace Polska, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Delegates from nearly 200 nations recently gathered in Katowice, Poland to move forward the Paris Climate Agreement. And as the session opened Fiji Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama cited the warning from IPCC scientists that without rapid action the Earth’s temperature will increase more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, with even more dire consequences the warmer it gets.

BAINIMARAMA: As the scientists have just told us, the window of opportunity to act is closing very fast time is running out. And we must move quickly to have any hope of capping global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-Industrial Age. Act now with courage and resolve, or God forbid, ignore the irrefutable evidence and become the generation that betrayed humanity and our responsibility to future generations.

CURWOOD: As we go to air it was unclear how and when countries will account for meeting the individual goals they set for themselves back in 2015, and we will update the final results of the COP24 meeting on our website, loe.org. But at the moment, of more than 190 countries only two nations report they are on target to meet their share of the Paris climate goals. Alden Meyer of the Union of Concerned Scientists is in Poland and joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Alden!

MEYER: Good to be with you again, Steve.

CURWOOD: How would you characterize the mood of this Conference of the Parties compared to ones you've attended in the past?

MEYER: Well, it's workman-like; they're trying to get the rules to implement the Paris Agreement, everything from what kind of information countries have to put forward when they submit their national pledges under the Paris Agreement, how you track and report on how well you're doing on those, what kind of market mechanisms they should set up to let countries cooperate. Tricky areas like land use, forestry and agriculture; just a whole series of issues, they have to address really setting up the guts of the Paris Agreement and how it's going to operate going forwards.

CURWOOD: So when countries showed up in Katowice, how were they doing in terms of meeting the targets that they had set themselves individually, three years ago after Paris?

MEYER: Well, the latest analysis by the United Nations Environment Program that was released just last month says that basically, we're only about a third of the way to the reductions between business as usual levels, and where we need to be in 2030 to have a chance of staying under two degrees, which is the less ambitious of the temperature goals set in Paris. It said we should shoot to stay well below two degrees Celsius and aim for 1.5 degrees. Just for comparison, we are now at about one degree Celsius increase over pre-industrial temperature limits. So we have a lot more work to do.

A ministerial dialogue on Climate Finance at this year’s COP. (Photo: Ministry Of Environment, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So with the United States pull back from the climate negotiation process, how was our delegation, folks associated with the Trump administration, how were they treated there in Katowice?

MEYER: Well, they haven't pulled back entirely, they're still a party to the Paris Agreement until they're actually able to formally pull out one day after the 2020 Presidential election, as it turns out. So they’re still participating actively in the rule book negotiations. Of course, they have pulled back on climate finance, cutting $2 billion out of the $3 billion dollar pledge to the Green Climate Fund that President Obama put forward.And of course, everyone is aware that President Trump and his team are actively seeking to dismantle virtually every aspect of domestic climate action. And so I think the negotiators are negotiating with one hand tied behind their back because they're not seen as leaders on climate ambition and climate finance the way they were during the Obama years. And yet, there's this sense that everyone wants to maintain the ability for the United States to come back in to Paris after President Trump leaves office. And that's what gives the negotiating team here for the US a little bit of leverage, is that people are hopeful that the US will eventually come back into Paris, if President Trump does indeed pull us out just before his first term ends.

CURWOOD: Katowice, Poland is at the heart of Poland's coal country. And the United States made a presentation during this conference on the US view of coal that we need to use more of it and it's really important. How was that received?

MEYER: Well, this is sort of a repeat of what they did last year, at the Conference of the Parties in Bonn, Germany, they hosted a side event with a number of panelists addressing coal as well as advanced nuclear. And their argument was that the world is using fossil fuels, and so we ought to deploy slightly cleaner coal technology that doesn't use quite as much coal per unit of electricity, and that would be better for the planet. But as the IPCC report made crystal clear, if you want to get anywhere near the temperature goals that countries agreed to three years ago in Paris, you have to virtually phase out use of coal by mid century unless you can develop carbon capture and storage technology and make that economic. So it was kind of viewed as a bit of a sideshow, a distraction. One delegate told me it was like a tobacco company setting up a booth and handing out free cigarettes at a cancer doctors’ convention. So it didn't go over too well with a number of countries. It was protested by global youth from around the world who occupied the space at the beginning, did a protest and then walked out about 15 minutes into the event.

CURWOOD: What still needs to be decided at this COP?

MEYER: Well, they have to make the final decisions on just about everything. They have been discussing the individual elements of the Paris rule book, but they have yet to bring those together at the ministerial level into an overall political package, so the countries can decide if there's enough in there for them. They have to decide what to put in the final decision in terms of the IPCC report, how to characterize that, what expectations there are on countries to take action by 2020 to revise their existing commitments under Paris. Basically, a lot of it is wide open. There's a few small things on adaptation and technology where they've reached a consensus and not too much heavy lifting there. But on the major issues they really haven't yet made, the political compromises that are going to be needed to reach a final agreement. Those are going to have to happen in the coming days.

CURWOOD: Shortly before this meeting began, it was understood that Brazil would host the next one. But I gather, they've backed out; why, and what does that mean for the process?

MEYER: Well, they said they backed out because the financial cost; hosting one of these Conference of the Parties can cost 80 to 100 million dollars for the host country. And they said it was a fiscal measure, but people suspected may have been related to the incoming president who takes office in January, President Bolsonaro, who is much more a climate skeptic about the science and has said that he wants to cut back on enforcement of laws and policies designed to reduce deforestation in the Amazon. So there's a bit of a sense that the real reason for this is that Brazil wasn't interested in being such a climate champion as they might have been in past years. The Latin American region is now discussing which country will get the bid to host the conference next year. It looks like the front-runners at this point, are Chile and Costa Rica. And they will have to make a decision on this by the end of this meeting so it can be formally accepted by the full Conference of the Parties.

CURWOOD: So Alden you've been going to these for a long time, first Conference of the Parties, 1995 in Berlin; original deal back in 1992 set up in Rio de Janeiro. How are you feeling about the process now?

A Polish anti-coal protestor demonstrates outside the COP venue. (Photo: campact, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

MEYER: Well, I'm feeling good about the action that the Paris Agreement has spurred around the world, if you look at the cities, the businesses, the states and provinces, a number of countries that are making pretty transformational commitments, whether it's to get 100% of their electricity from renewable energy or trying to get to net zero emissions. But the reality is that we haven't done enough, emission trends continue to go upwards. The problem as you well know, Steve, is that we're running out of time, we don't have a lot more time and we're not keeping up with the physics in the atmosphere. And the problem is mounting. So it's a bit of a yin and yang I guess you'd say, there some indications of hope and progress and some areas that are raising concern, and on balance we're clearly not doing enough.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is Director of Strategy and Policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today Alden, it's always a pleasure.

MEYER: Great Steve, I've enjoyed being with you.

UPDATE: A deal was finally struck regarding rules for the Paris Climate Agreement after marathon negotiations. COP25 will be in Chile in November of 2019.

Related links:

- John Kerry: "Forget Trump. We All Must Act on Climate Change." The Paris Climate Agreement co-creator and former US Secretary of State speaks out

- New York Times COP24 Delegates Reach Agreement After Marathon Negotiations

- A statement from Alden Meyer about efforts to downplay IPCC Report

- Time | The Trump Administration Pitched Coal At A Climate Change Conference

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the climate treaty

[MUSIC: The Napa Valley Duo, “Vocalise” on A Soft Message To You, by O. Messiaen, John Song Music]

Beyond The Headlines

December 24th, 2018 marks 50 years since astronaut Bill Anders shot the iconic “Earthrise” photo as the Apollo 8 mission became the first crew to orbit the moon. (Photo: Bill Anders, NASA)

CURWOOD: Well it's time to check in with Peter Dykstra now for a look beyond the headlines. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN dot org, and Daily Climate dot org, on the line now from Atlanta, I believe; Peter, you there?

DYKSTRA: I am. How you doing Steve.

CURWOOD: Good, and what do you got for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well we're talking about an old, old idea that may help our current big, big problem of climate change and greenhouse gas emissions.

CURWOOD: OK?

DYKSTRA: Ships at sea are a huge, huge contributor to greenhouse gas. And engineers and startup companies are looking at sails on even our biggest cargo ships.

CURWOOD: Wow. That would be amazing because I think I saw a statistic go by the other day that says all those ships out there would be number eight country in the world for global warming emissions. So what's the plan?

DYKSTRA: Well there are a couple different designs. None of them have gone into the actual use phase. One of the ideas that's popular: not really sails per se, but these cylindrical turbines right up and down the deck that suck in wind and cut down on the use of bunker oil and the heavy fuel that powers big ships. Another one involves solar panels on masts put on the deck. There's a third design that uses the 21st century version of actual sails. Couple of quick numbers, they're looking at immense potential cuts in fuel costs, maybe as much as half of the current fuel costs. Fuel on a typical cargo ship can be fifty thousand dollars a day or more. And by that I mean a lot more.

Cargo ships are powered by bunker fuel, which is a major source of air pollution. (Photo: Wolfgang.W., Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Oh my. Well, hey we've been using sails as a civilization since, what, last couple thousand or more years, maybe this will work? What else do you have for us today.

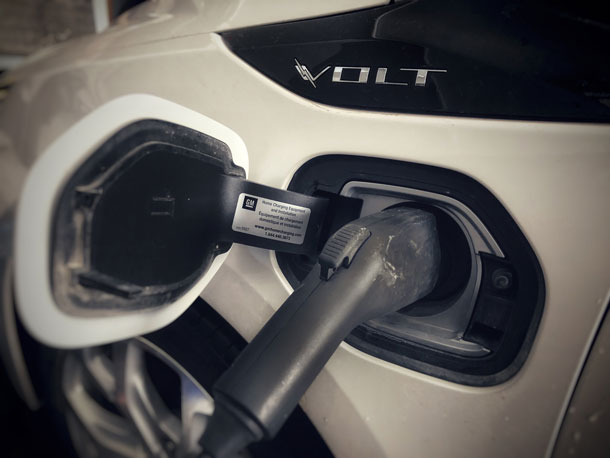

DYKSTRA: Some news from GM. There was of course the announcement earlier in the month that they were going to close five factories and lay off about 15,000 people. One of the factories they're closing down is in Hamtramck, Michigan outside Detroit. That's where they make the Chevy Volt. And when that factory shuts the Chevy Volt goes away.

CURWOOD: Why are they doing this, does it have to do with the seventy five hundred dollar tax credit disappearing do you think?

DYKSTRA: That's a possibility. Right now there's a federal tax credit of up to seven thousand five hundred dollars. But there's a catch: once a specific model reaches 200,000 cars sold, that tax credit goes away. Tesla's already there. They've sold over 200,000; the Chevy Volt could reach that limit before it ends production in the month of March.

CURWOOD: Hmm, you know, I guess people wouldn't be interested in paying another seventy five hundred dollars for the same car at this point.

DYKSTRA: Right.

CURWOOD: Hey what do you have from the history vaults for us.

DYKSTRA: Fiftieth anniversary. This is actually a bit later in the month just before Christmas, but it's a really cool anniversary. In December 1968, Apollo 8, one of the precursor space missions to Apollo 11 that landed men on the moon -- but on Apollo 8 there were three astronauts, Frank Borman, James Lovell, and Bill Anders. Anders took a photograph that endures as one of the most famous photographs ever, of an Earth rise, something that human beings had never seen before.

CURWOOD: Peter, how did you feel when you first saw that photograph?

DYKSTRA: I thought it was pretty cool. And for some reason I was expecting the earth to be a different color, even though it's predominantly ocean. But it was just a beautiful picture from space. It led to a lot of speculation about all of the things we can learn about Earth, about living on Earth, from space.

CURWOOD: And when I saw that I had a couple reactions: first thing, I-I choked up, because it just was so astonishing. And then I thought about the people who'd gotten us this photograph and how huge the void is, because the Earth in that picture is so tiny compared to the vastness of space, and how they had to have everything work right in order for them to get back home safely.

GM is discontinuing production of the Chevy Volt, a breakthrough electric car model. (Photo: Shelby L. Bell, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: And they had computing power on board that was less than we carry in our pockets under an iPhone.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Hey Peter, we're heading into the holidays so it'll be a little while before we talk to you again. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN dot org, and Daily Climate dot org. Happy Holidays, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Yeah happy holidays to you and the staff and all the listeners. Thanks a lot Steve.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, LOE dot ORG.

Related links:

- Marine Insight | “Top 7 Green Ship Concepts Using Wind Energy”

- Fuel costs in ocean shipping

- The Wall Street Journal | “GM Bids Farewell to Its Breakthrough Electric Car”

- What you need to know about the EV tax credits

- About Apollo 8’s “Earthrise” photo

[MUSIC: Mâcon symphonic orchestra, “Earth, the Bringer Of Life”, A new planet for the Holst Planets Suite, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbHQ6eWANIo]

CURWOOD: Coming up – We’ll take a look at the individual countries that are on target to meet their climate goals and those that are lagging behind including the US. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Brian Rolland, “Along the Amazon”, Dreams of Brazil, ℗ 2002 On The Full Moon Productions]

Climate Action Off Track

The CAT Thermometer shows the world has a long way to go between current policies and the Paris Agreement goals. (Image: Climate Action Tracker)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Arthur and Mongstar, “1.5 To Stay Alive”, Heights Music and Minor Productions, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r3rokuuRPsA]

CURWOOD: “1.5 to stay alive” is a rallying cry for island nations at the UN climate talks. In 2015 island states pushed for the Paris Climate Agreement to focus on keeping the Earth’s temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, as even a bit more warming will flood low-lying island nations. And scientific evidence shows that a world that becomes even 2 degrees warmer is far more disastrous for civilization than a world that warms by 1.5 degrees or less. Let’s check in now with Yvonne Deng, a member of the independent group Climate Action Tracker to see which countries are meeting their share of the 1.5 degree goal. She joins us from COP24 in Katowice, Poland, and notes that the tracker ratings take into account the unique situations of each country.

DENG: When you look at the overall emission reductions that we need to see globally, it doesn't mean that every country has to reduce their emissions, right? There are countries that are still developing, they need to be allowed to increase their emissions still from current levels. And there are countries that have already developed and they really need to look at decreasing emissions. And there are various different, actually, schools of thought or approaches to how you share this sort of global emission reduction across different countries. You could think of an approach where you say, well, we should all get to a certain per capita emissions level by a certain date and sort of draw a line between now and then, or you can think of approaches that account for the fact that some countries of course, historically emitted a lot of emissions to further their development. And you could think of approaches which say, well, the wealthy nations would do more. At the Climate Action Tracker, we don't take a pick. We actually use all of the approaches out there and we look at the whole range of possible emission levels per country, in any of these approaches, and then we determine what we call the fair share range of emission reductions, and that informs our rating scale.

The five countries in the “Critically Insufficient” category include Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Saudi Arabia and the United States. (Image: Climate Action Tracker)

CURWOOD: So, which countries are really not doing a whole heck of a lot to meet their commitments under Paris?

DENG: So, the majority of our countries are not quite there yet. But we certainly have a group of countries that we rate critically insufficient or highly insufficient. These include countries like Russia and Ukraine, Saudi Arabia, Turkey. The US is obviously one and this is at the federal level. We need to be very clear that in the US there's a lot happening at state and local level, but at the federal level, of course, we have a lack of action and rather a reversal of direction. Really, all countries could do more to reduce emissions.

CURWOOD: So, now with the U.S. taking a step back, you see China really in the leadership both in the negotiation process and in terms of infrastructure. How does your analysis rate China's progress on meeting the Paris targets?

DENG: The Climate Action Tracker currently rates the Chinese target under Paris as highly insufficient. It's not strong enough, unfortunately. So, they can step up ambition. But the good thing with China is that when they set themselves a target, they also tend to achieve it. China is doing a lot on the ground. They published their 13th five-year plan, which has seen a cap on coal in primary energy; it’s seen a cap on energy demand, and it's got capacity targets for non-fossil power, and they're also doing a lot in roll out of electric vehicles. So, China is certainly doing a lot, and can do more also in terms of coal, which I believe has taken a slightly larger share again in recent years. But I think they can be a leader if they step up and address the coal issue.

A graph from the Climate Action Tracker’s December 2018 update shows the wide emissions gap between policies currently in place and the 2 degrees Celsius and 1.5 degrees Celsius Paris targets. (Image: Climate Action Tracker)

CURWOOD: What about India? How well is that doing?

DENG: I'm glad you mention India. In the group of the big economies that we track, India is really a shining light. They have set themselves a target that we already rate as being 2 degree compatible. If they increase that ambition, they could become the first large economy to be one-and-a-half degree compatible. And they have also put policies in place to really scale up their renewables, and they're thinking about policies on electric transport and others. But India also still is relying a lot on coal, they’re also still thinking of expanding coal and that's something they will have to address.

CURWOOD: By the way, if you go to your website, you see something called the C-A-T, the CAT thermometer. What is that? What does it do?

DENG: So, in addition to rating each of the countries’ commitments under Paris, we also look at these emissions levels they've committed to, and we roll them all up to global level, and then we say well what does it mean in terms of the warming we expect by the end of the century? If countries did what they've committed to under Paris, how much warming would we see? And currently we're seeing around three degrees or so warming by the end of the century with what countries have committed to. We also look at what the warming would be if countries carried on as they're currently planning. So, our warming projections for the current policy trajectory are slightly above three degrees. But the good news is that we have almost all the technologies available that we need for this. Some things we have to figure out. But the vast majority we have, and the challenge really is in getting them out there and getting them scaled up. So this is a political problem. It's a question of willingness to do it. It's not a question of figuring out how to do it technically; that would be even scarier but we know how to do it.

CURWOOD: Yvonne Deng is an associate director at Ecofys, a Navigant company which is part of the Climate Action Tracker. Yvonne, thanks for taking the time with us today.

DENG: Thanks for having me.

Morocco and The Gambia are leading the world with policies that are compatible with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degrees Celsius target. (Image: Climate Action Tracker)

CURWOOD: The Climate Action Tracker rates just 2 countries as compatible with

the Paris Agreement target to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, The Gambia and Morocco. The Gambia just embarked on a six-year, $25 million project to plant trees and restore degraded lands. And Morocco is already close to 40% renewable energy and in a decade more than half will be renewable. The country’s former Environment Minister Hakima El Haite says Morocco has been on a path to a low-carbon economy for decades.

EL HAITE: Since 1964, we had understood in Morocco that we are affected by climate change. And that time our dead King decided to create dams in Morocco, big dams, to store water because he wanted to ensure drinking water to the people of Morocco and to ensure the food security for the Moroccans. So, we began our fight against climate change many, many, many decades ago. And then our King Mohammed VI decided to cut the subsidies on fossil fuel, and now Morocco is choosing green technologies in its investment.

CURWOOD: So, since Morocco is now doing its part to meet the target of keeping things below one-and-a-half degrees Centigrade, how does your country feel about the lack of ambition that we see on climate change from the United States and many other countries at this point?

EL HAITE: I’ll be very frank; when you see that Americans withdraw from the Paris Agreement, I'm not only disappointed, I'm feeling that politicians are not taking their responsibilities. United States was a leading country during the negotiation, and now, as President Trump decided to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, they are still blocking the negotiation. And this is not correct! Africa, the whole of Africa is only four percent of the emissions worldwide. The ones who are impacting the world are the ones who are fuel producers and industrial developers, and those countries should lead the negotiation. I’m thinking about the United States, Russia, China, Europe, etcetera.

So, I'm really feeling as a Moroccan, as an African, as a citizen of the world, disappointed and feeling that those who are blocking the negotiation now are not taking their responsibilities. And many millions and millions of people will die because of this decision.

CURWOOD: So, looking down the road, what kinds of climate impacts could affect Morocco in the years to come?

EL HAITE: Oh, we are already affected. Drought. Desertification. Migration... in Africa, I will tell you, 500 million hectares are degraded because of climate change. Millions and millions of people are migrating and dying in the Mediterranean Sea because of climate change. And those are not things we’re reading in reports, you know? Those are things we are living already.

Wind turbines along the Morocco coast, near the town of Tarfaya. (Photo: TEDxTarfaya, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hakima El Haite served as Morocco's Environment Minister from 2013 to 2017, and she's now President of Liberal International. Minister El Haite, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

EL HAITE: Thank you.

Related links:

- The Climate Action Tracker’s Warming Projections Global Update, December 2018

- The Climate Action Tracker thermometer graphic

- About Liberal International

- The Berlin Declaration On Climate Justice

[MUSIC: Chalf Hassan, “Lahssab Talata We-Talatin” on Arabic Songs From North Africa, ARC Records]

Most Republicans Believe In Climate Change

Recent polls show that more Americans believe in climate change than ever, regardless of their party affiliations. (Photo: Stephen Melkisethian, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: A majority of Republicans have now joined a majority of Democrats and Independents to say they are concerned about climate change, according to the Monmouth University Polling Institute. More than 800 US adults were polled amid the news of the California wildfires. But while nearly 80% of those surveyed say they believe in climate change, only about a third feel immediate action is needed to meet the growing climate crisis. Tony MacDonald is the director of Monmouth University’s Urban Coast Institute, and he joins us now.

MACDONALD: Thank you very much for inviting me.

CURWOOD: So, what's the major takeaway of this study?

MACDONALD: I think the one is that we really saw a huge jump in the last three years in the number of people who believe in climate change. And that was bipartisan. There was over a 15 percent increase in the number of Republicans from 49 to 64 percent. So overall, 78 percent believe in climate change. And increasingly, we are seeing that this is not as often reported as just a Republican or Democratic issue.

CURWOOD: There is a tilt though that remains, that independents are more likely than Republicans to believe in climate change and Democrats even more so. But still, a majority of people you say?

MACDONALD: Yeah, I think the tilt starts to come out and be a little bit pronounced when you think about how serious it is. So again, we are seeing some increases in the amount of people who think that it is a serious problem. So, again, 54 percent think it's a very serious problem, up from 41 percent three years ago. But you do see that essentially the Democrats, 82 percent think it's very serious, where only 25 percent of the Republicans do. So, I think where you start to see the breakdown is that the need to take action right now, how serious it is, and that is still a fairly big gap.

CURWOOD: And what about this notion of “believing in climate change”? Because, you know, a number of folks out there say, Well, yeah, there's climate change, because the climate always changes on the planet, and humans don't have that much to do with it.

Monmouth University’s polling overlapped partially with the Woolsey and Camp wildfires in California – two natural disasters that are part of a pattern of more severe fire seasons in the West. (Photo: National Park Service, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MACDONALD: That's a good observation because our polls showed that actually, there was a split on what the causes were. So 37 percent, a plurality, still believe that it is essentially human and environmental caused, and so they don't single out the human contribution to it. And only 29 percent believe that it's primarily caused by humans. So again, there's still a lot of disconnect, that I think obviously leads to a concern that if you don't believe that humans are the problem, then you might not necessarily think that action is needed to change human behavior. So, I do think it starts to split apart again, and when you look at the need for action, and when to take action.

CURWOOD: So, what does your data tell us about the outlook of Americans when it does come to climate change across the board? How worried are they? How optimistic are they, do you think?

MACDONALD: Well, interestingly enough, there is some optimism that there is still time to take action in general. But what you do have is that 31 percent think it has to happen in the next two years. But over 46 percent believe it doesn't have to happen for 10 or 15 years. So, although there's optimism, it might be the sort of hopeful optimism that maybe the problem will go away, it will be something we can deal with another day. Again, I think there's no really broad consensus of a need to take immediate action. There was an interesting finding, as well, however, that the majority of Americans did think that government could take more action. So, it would be appropriate for the government to take action. But that is kind of undercut by the other finding that says that very few people have any confidence in Congress to take action.

CURWOOD: Now, studies show that registered voters who rank environmental issues as their number one or number two issue tend to be young, African-American, Latino, live in urban areas, many of them also make under $50,000 a year. What did you see in the demographic breakdowns of your study?

MACDONALD: We didn't go to that level of detail, Steve. But we did find that in fact, more young people did think that climate change was a very serious issue, and they saw a need to take action sooner. And they also were, as young people tend to be, a little more optimistic about the ability to respond. So, we did sort of verify, I think, your general sense that the younger folks are more interested in it. But it does seem that, you know, Hispanics, Blacks, 74 percent think that it is a very serious problem. But I mean, they might just feel more vulnerable in general to the impacts. I mean, there's many minority communities who are in coastal urban areas and cities that might feel more at risk, they might feel also that they have less ability to respond. I mean, you read a lot right now about after storms in the ability to rebuild and if you don't have insurance or are not self insured - so again, this is speculation - that I think they would probably feel more vulnerable to not only the physical impacts, but also the dislocation of jobs and homes. That could be some of the reason that you see a higher concern in the Hispanic and Black communities.

Polling data shows that younger generations are more likely to think the environment is a serious issue, but are also more likely to be optimistic about our ability to enact change that can help protect our planet. (Photo: Fibonacci Blue, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Tony, how do you feel when you look at these results? How expected were they?

MACDONALD: I think they were not expected in terms of the degree of a shift in the direction of climate being a significant issue and one that needed action. And I think it's a fairly significant shift. We don't see that shift that often. I would say, however, I'm still concerned that maybe the motivations are going to be still political and economic in the end, and in the costs of responding. And there's still some significant disconnect between communities in terms of the need to take action quickly. And so, there's still a huge disconnect between the seriousness of the problem, which I think most scientists agree is now and the need to take action, which, still, most of the respondents think doesn't have to happen for 10 or 15 years.

CURWOOD: We recently talked to folks from what's called the Environmental Voter Project who had surveyed some 20 million registered voters who say they list the environment as their number one or two concern. And in 2014, only a little more than 4 million of those people bothered to show up at the polls. Twice as many showed up at the polls at this last midterm election, closer to 8 million. Given the trends that you see in concerns in these kinds of voter polls, where do you think we might be headed in terms of getting more action on dealing with the climate?

MACDONALD: Well, I think there's a couple of things. One is I think sometimes in the US, I think association with the environment can be perceived as something really that's simply about nature, not as an aspect of the environment. So, I think traditionally, environment has ranked low in past years, it's starting to come up again, which we haven't seen in a long time. But I do think environment’s been perceived as protecting nature. I think the climate issue is such a more complex one, that it really is about protecting societies and social fabric.

Tony MacDonald directs Monmouth University’s Urban Coast Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of Monmouth University)

So, I do think you see political movements and politicians that are making connections between the environment and everything from social justice, to religion, to social elements to responsible business. I do think it's a very positive thing and I think you really are starting to see a real kind of a recipe for change.

CURWOOD: Which of your results concern you, Tony?

MACDONALD: I do think that lack of sense of immediacy is the thing that concerns me most. So, they may be long-term problems, and they may be investment over a long period of time. But if we don't start now, I do think we may get behind the 8-ball in significant ways. So I would say my most active concern is the lack of immediacy.

CURWOOD: We’ve pretty much known about this climate disruption for a quarter century now, had a United Nations treaty to deal with it; every year, there are reports that are saying it's getting worse and worse. And yet, we seem to think it's something that we can deal with in the future, the majority of us do.

MACDONALD: Yeah, I have seen how, particularly in the international fora, it takes a long time to reach a consensus, although the US is backing off from Paris. It was a long time to reach the kind of consensus about the need for dramatic action. So, I do think those legal processes can move slow. But I think that the real conflict here is that it is a long-term problem. So, the real effects aren't going to be felt for a long time. We can defend for a while. We can live the way we currently do for a while. There will be a lot of casualties along the way. But again, the reality is we're building a wall that's going to collapse eventually. So, I think it's the disconnect between the length of the commitment it's going to take to solve this problem and the need for immediate action. So, I think people are afraid about, our lives are going to change and we are much more able to do that after something significant happens. You know, we all don't worry about our health until something goes wrong, and then we might radically change the way we perceive ourselves. And so, I do think that's just an unfortunate reality, that this is a complex and long-term problem that does defy short-term quick fixes.

CURWOOD: Tony MacDonald is the Director of Monmouth University's Urban Coast Institute. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

MACDONALD: Thank you. It was good talking with you.

Related links:

- Monmouth University Polling Institute: “Climate Concerns Increase; Most Republicans Now Acknowledge Change”

- EcoWatch | “Climate Change Acknowledged by Increasing Number of Republicans, New Poll Finds”

- Read the Poll Report Here

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Silent Night” on Jingle All the Way, by Franz Gruber, Rounder Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up -- A scientific creation story for the Earth and our nearest neighbor, the Moon. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “River” on Jingle All the Way, by Joni Mitchell, Rounder Records]

Creating The Earth And Moon

An artists’ rendering shows how the Earth and Moon formed from the vaporized rocks of a synestia. (Photo: Sarah Stewart/ UC Davis based on NASA rendering, courtesy of UC Davis)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The tremendous force of a collision in space can create as well as destroy planets. And in an attempt to understand how the Earth, and our nearest neighbor, the Moon, were created, scientists including Sarah Stewart use the next best thing to planetary collisions: a gun. Sarah Stewart is a Planetary Scientist at the University of California, Davis and a recipient of one of this year’s MacArthur Fellowships. Sarah Stewart, welcome to Living on Earth.

STEWART: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: Putting the cards on the table, Sarah, there are not a lot of women who are scientists, senior scientists these days; not a lot of astrophysicists. What got you into science?

STEWART: As a child, I read a lot of science fiction. I watched Star Trek with my father and it seemed real, right? It wasn't something that was impossible to conceive, that I could do these things too. And I had a fantastic high school physics teacher who really got me hooked, and I credit him, Eric Curry, at O'Fallon Township High School for really nurturing my interest in science. So I went to college thinking I would be a physicist. And so I think that alone is unusual in that there was nothing around me that said, this was an odd thing that I wanted to do.

CURWOOD: So, who was your favorite character on Star Trek?

STEWART: Oh, well, of course, Spock [LAUGHING] because, you know there's something attractive about analysis, about breaking things down, and trying to figure out how it works. And even though he had other extreme personality traits, that process was very interesting.

CURWOOD: So, the MacArthur people became fascinated with you, in no small measure, because you've been looking at the question of this thing we call the Moon – how did we get it, and how's it related to us? What about this area of study drives you?

STEWART: I think there's an inherent curiosity to where we came from, and how the Earth came to be the planet that's so different from our neighbors. And even though that's a general question that people are interested in, what we have today are comparisons -- we have exoplanets that tell us that our system is not the most common in the universe, and that Earths are not common in the universe. And so, I basically have been trying figure out why, what is it about the way the Earth grew, that was different. And our nearest neighbor, our partner in space, the Moon, is a key part of that story, because it set the ending of Earth's growth and the beginning of our climate in ways that did not occur on the planets next to us.

CURWOOD: So, what got you first interested in this question of where the heck did the Moon come from?

STEWART: So, in trying to understand the general problem of planet formation, I learned that collisions were a key part of the process. And I didn't know that I was going to do that as part of planet formation. I thought I was going to be an astronomer. But when I went to graduate school, there was a professor, Tom Errands, who had a gun lab - literally cannons in the basement of the building - and he could do these impact experiments that mimicked planet formation. And I did a first year project with him, and I was hooked.

CURWOOD: So, there you are, you're in the airplane and person next to you says, “So, what do you do?” What's your 30 second speech to them about what it is that you do and what you've discovered?

STEWART: I study how planets form and evolve. I combine lab experiments that recreate planetary collisions with computer models to answer questions that we see in the solar system.

CURWOOD: And what have you discovered so far?

STEWART: What we've learned is that a giant impact transforms the Earth into a new planetary object. And we call it a new object because it's no longer a planet. It's not a planet with a disk orbiting around it like the rings of Saturn. We make an object that we named a synestia. A synestia is a vaporized planet spinning rapidly that looks kind of like a giant space donut and within that vapor of the synestia, we propose that the moon grows. And because the moon is growing inside the vaporized rock of the Earth, the moon inherits the chemical signature of the Earth. And that explains the unusual similarity between the Earth and the Moon.

CURWOOD: So our mantel, which in some respects is kind of like a coat, or something, or coating around this core, and the moon itself, made of the same cloth, if you would say, and it all came out of this swirling sort of donut thing, from this synthesia form that you call it, and that's how we're related. How the heck did you figure that out?

STEWART: We run computer models, but there's a human step of needing to interpret what comes out of these models. And it turns out that scientists have probably been making synestias in their computers for a long time before realizing what they had. And that's partly because we make assumptions when we analyze the data. And one day my student, Simon Locke, and I were sitting in front of the computer making plots that we had never made before. Meaning, rather than making assumptions, we just said, what does it look like raw? And what does that mean for what comes next. And we convinced ourselves that what we had been assuming about what comes next was absolutely wrong, and that we had something completely different. And so, that was our big moment.

CURWOOD: Now, how does this differ from the other hypotheses out there about how the moon was formed?

STEWART: So, the giant impact model rose out of the Apollo mission 50 years ago almost, or the first rocks from the moon. And they disproved every previous model of lunar origin that was in the literature. And the giant impact hypothesis basically constrained the total mass of the moon, the fact that the moon has a small iron core. And when computer simulations were run with a giant impact model that satisfied those constraints, the moon was made primarily out of the object that hit us. But because no two objects in the solar system are identical, it did not explain the chemical observations that we had. And this has been a problem the whole time that we've had the giant Impact Theory. And people have proposed different Band-Aid solutions of how to try and get around this problem. But we were at the point where the whole idea of the giant Impact Theory was about to be thrown out because we did not have a reconciliation of the physics and the chemistry.

Sarah Stewart is a planetary scientist and one of 2018’s Macarthur Fellows. (Photo: Courtesy of UC Davis)

CURWOOD: And then you...can you call it a tweak, what you did?

STEWART: So, I say, we still have a giant impact origin for the moon. But we changed everything else about it, except the name. [LAUGHS] It is a variation, it's higher energy, higher spin. And the reason why those two things are important is that's what makes the synestia, and the moon forming in a synestia is a different environment than the moon forming in the old giant impact models. The moon forming in the old giant impact models was primarily a debris disc derived from the impactor and the moon didn't have a direct connection with the Earth, not the same way that there is a genetic relationship between the Earth and the Moon within a synestia.

CURWOOD: Why is it important for us to know all of this?

STEWART: The origin of the Earth is intimately tied to the origin of the moon, in trying to understand what makes the Earth the habitable planet that it is, we want to know how much water it retained, how much atmosphere it retained, and this is the last major energetic event in Earth's formation. And the Earth is a different object right as the moon is forming, and trying to understand how the Earth re-constitutes itself and becomes a solid body again, with an ocean and an atmosphere, is key to understanding the initial conditions that led to where we are today. And so we're trying to understand what happens next in Earth's evolution. How does it become the planet we see today?

CURWOOD: And the answer?

STEWART: It's hard. [LAUGHS] It's hard to do. So, this is work in progress. Understanding how the vaporized planet cools is another exercise in stretching our imagination. For example, in the synestia, the Earth has no surface. There's no magma ocean to float a boat on. Instead, what we have is continuous vapor up to a high pressure liquid with no boundary. Temporarily, the Earth is more like a giant planet like Jupiter, which also has no liquid surface. And so even that starting point and thinking about the moon is something that we have to now invent techniques to attack and understand that we didn't need before.

CURWOOD: Sarah Stewart, what advice do you have today, particularly for young women who might be looking at science?

STEWART: My advice for young women interested in science is to go for it. If you love it, don't let anything around you beat out your love of science. And a way to be successful is to accept that everybody needs help and to ask for help. It is possible to live your life the way you want to and have a career in science. And the trick is finding what works for you.

CURWOOD: Sarah Stewart is an astrophysicist and a professor at the University of California, Davis, and one of this year's MacArthur fellows. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

STEWART: Thank you very much, Steve.

Related links:

- Prof. Sarah Stewart’s Lab homepage

- Macarthur Award Description

- Journal of Geophysical Research | “The Origin of the Moon Within a Terrestrial Synestia”

- Learn more about the Shock Compression Lab

[MUSIC: Miles Davis, “It’s Only a Paper Moon”, Dig, Apex Studios, New York]

CURWOOD: Starting next week we’ll take a look back at a few of our favorites from this year and feature some holiday storytelling. Next week our show will include a visit with Denny Breau in the frozen north of Maine.

CURWOOD: So you grew up in...

BREAU: I grew up in Lewiston, Maine.

CURWOOD: Mainers...when you go home there's, yeah, the place where you live and then there is camp.

BREAU: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. Camp is a very important thing, and we’ve been going to this one particular camp for 30 years, the family and I. Every year, at the end of the summer when we start to close it up for the season, we do what they call an “I-C.”

CURWOOD: An “I-C?”

BREAU: An “I-C.” That's an "idiot check".

CURWOOD: Oh. [LAUGHS]

BREAU: You kind of go through the camp and make sure you didn't forget your sunglasses or your favorite bathing suit or your favorite CD. It could be just about anything you just don't want to leave there so you have to go back ’cuz it's a ways away. One year we forgot the dog. Yup, we left the dog there. Had to turn around go back. "I thought you had the dog." "I thought you had the dog." Well, nobody had the dog, so…

CURWOOD: Now, I imagine your camp is some place near a lake in Maine.

BREAU: Yeah, it's up in Peru, Maine, a place called Worthley Pond.

CURWOOD: And of course, because winter is coming along, that sets you up for a great Maine tradition.

BREAU: I've never actually ice-fished myself. I've sat in the shacks and shared a few stories and a couple of glasses of this and that. You actually cook meals and just wait for a bite, and certainly around the holidays a lot of people love to get together and get ice-fishing and maybe have a nice fresh salmon along with the pot roast, ya’ know.

So anyway, this next song is called “Ice-Fishing.” I kind of wrote it to poke fun at Mainers a little bit and their garb and the tradition itself and just all of the fun aspects of ice fishing. I hope you like it.

[BREAU PERFORMS SONG “ICE FISHING” ON ACOUSTIC GUITAR.]

BREAU: Way up north where the cold wind blows

When the lake freezes over people chop little holes

Drop a line and kick back in a little square shack

And if the ice didn’t melt they’d never go back.

A little wood stove just a waitin’ for a bite

Drinkin’ all day and drinkin’ all night

Gonna sit right here ‘til the winter ends

And I’ll be sittin’ right here when it comes again.

Ice fishin', nothing is quite the same.

I’m itchin’ to get back in the game.

They say 20 below and three feet of snow.

Grab your stuff ‘cause we’re still gonna go.

Ice fishin’, just a party by another name.

Ice fishin’, a tradition here in Maine.

Green gummy boots lined with felt

A bean pocket knife hanging off of my belt

Plenty of beer and plenty of time

A knitted wool cap that’s one of a kind.

If you don’t like fishin’ you can still tag along

‘cause there’s plenty of fun on that frozen pond

Stories to tell, guitars in hand.

Supper ‘s swimming around ready to jump in the pan.

Ice fishin’ nothing is quite the same.

I’m itchin’ to get back in the game.

They say 20 below and three feet of snow.

Grab your stuff ‘cause we’re still gonna go.

Ice fishin’ just a party by another name.

Ice fishin’ a tradition here in Maine.

CURWOOD: Singer songwriter Denny Breau joins us next time for some holiday storytelling on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Sultans Of String, “Himalayan Sleigh Ride,” on Christmas Caravan, by Chris McKhool, Kevin Laliberte, Anwar Khurshid, MCK (McKhool/Laliberte) Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And you can see us on instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening! And enjoy the holiday season.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth