May 24, 2019

Air Date: May 24, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Global Warming Poor Tax

View the page for this story

As if the crop failures, infrastructure damage, and biodiversity loss linked to climate change weren't already enough, new research finds that since 1961 global warming has reduced the GDP of poorer countries an average of 25 percent while some richer countries have actually benefited. Stanford University’s Marshall Burke tells Host Steve Curwood how climate disruption is worsening global economic inequality. (09:20)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Looking beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss a number of recent lawsuits filed against Bayer- Monsanto. The company’s popular herbicide, Roundup, contains the chemical glyphosate, which litigants allege has led to their development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and other health problems. They then discuss Montreal’s new marketing campaign to address pollution from cigarette butts, and conclude by looking back in history to May 25, 1958, when President Eisenhower ordered the switches flipped to start the nation’s first electric utility nuclear power plant in Shippingport, PA. (04:22)

BirdNote®: Recycle Your Egg Shells to Help Nesting Birds

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Female birds need to eat calcium to have enough of the mineral to lay their eggs. But it can be hard to find enough in nature. We can help our backyard birds by offering them some extra calcium in bird feeders and by recycling our used chicken egg shells. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein explains. (01:49)

Saving West Africa’s Last Rainforest

View the page for this story

When an oil palm development in the poor West African country of Liberia uprooted indigenous communities, destroying their religious shrines and burial grounds, and moved to cut down the last major swath of tropical rainforest in the region, lawyer Alfred Brownell jumped into action. He and his colleagues were able to persuade the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil to get the company to back off, but not without great personal risk. Attorney Brownell, who has been recognized with a 2019 Goldman Environmental Prize, tells Host Steve Curwood why the remaining Liberian tropical rainforest is so important to protect, as a vital natural resource and as the home of indigenous people. (26:44)

Grammy Goes A-Gatherin’

/ Ann MurrayView the page for this story

Dandelions can be the bane of a lawn owner’s existence. But for 97-year-old Virginia Dobell, whom everyone calls Grammy, dandelions are a culinary delight. Reporter Ann Murray of The Allegheny Front went out picking dandelions with Grammy on a nice spring day and has our story. (01:11)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alfred Brownell, Marshall Burke

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Ann Murray, Michael Stein

THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Climate disruption is already creating winners and losers in the world’s economies.

BURKE: Some of the colder parts of the world have actually benefited from this warming, they've warmed up a little bit and actually become more productive. We see that clearly in the data. The hotter parts of the world have had the opposite effect. They've actually experienced declines in their economic productivity.

CURWOOD: Also, a Goldman prize winner says protecting nature is worth the ultimate sacrifice.

BROWNELL: If no one is prepared to lay their life down, to fight to preserve Mother Nature, to protect this planet, to ensure that generations unborn will come and have a safe and healthy environment, if the world and the planet is not worth the battle, what else are you prepared to give your life up for?

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth, stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Global Warming Poor Tax

Warming temperatures make already warm places extremely difficult for life to thrive in, including humans. (Photo: Flickr, Kenya Red Cross Society CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The sharpest increases in global average temperatures have come since the 1950s, and it turns out for the short term, that’s good for business in the richer parts of the world, which happen to be cooler. But on the other hand, the poorer countries in the hotter parts of the world have seen their economies grow slower, or in some cases even decline as the planet has warmed. In other words, climate change is worsening global economic inequality. This is according to a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Noah Diffenbaugh and Marshall Burke. And Marshall Burke, who is an assistant professor of earth science at Stanford University, joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

BURKE: Thanks a lot, Steve. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So let's start by having you briefly summarize the results of your study.

BURKE: Sure. So what this study looks at is the overall economic impact of the global warming that we've already seen over the last half century. So we often think of global warming as something that's going to happen in the future. But it turns out the world has already been warming due to anthropogenic or human-caused influence. And so, what we wanted to understand in this study is what has been the impact of the warming that we've already seen? Has this done anything to economies around the world? And what we found is that indeed, it has. I mean, it turns out that some of the colder parts of the world have actually likely benefited from this warming. They've warmed up a little bit and actually become more productive, we see that pretty clearly in the data. The hotter parts of the world have had the opposite effect, they've actually experienced declines in their economic productivity. So, most of the rich countries in the world happen to be cold, most of the poor countries in the world happen to be hot. So, if the cold countries are benefited, and the hot countries are harmed, then you get an increase in global economic inequality. And that's the main finding of our study.

CURWOOD: Give me a couple of numbers here. How did this decrease the wealth of the world's poorest countries? And what's the gap between the group of nations with the highest and lowest economic output per person?

BURKE: Sure, so we should be clear that we're thinking about, and your listeners should have in mind, two different worlds. The world that we experienced, that warmed up roughly half a degree or a degree over the last half century. And we want to compare that to a world that did not warm up by that much, where the temperature was fixed at pre-1950s levels, right. So, compare two words, one that warmed and one that didn't. And we're saying all right, what's this economic wedge between those two worlds. And what we find is that in poor countries, their economies might be 20% smaller today than they would have been had we not experienced the warming we did.

Recent studies show that rising global temperatures intensify global inequality. (Photo: Flickr, World Meteorological Organization CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, one of the rather disturbing aspects of the results is that, at least with a modest amount of warming, it benefits the richer countries, to the detriment of poorer countries. In a funny kind of way, a little bit of warming is good for business for rich folks.

BURKE: We do indeed find that. So, if you're in the colder parts of the world, we do see fairly clear evidence that their economies are more productive when the earth warms up a little bit. If you look around the world, like let's take the coldest places in the world, and let's take the hottest place in the world. So, take Antarctica versus the Sahara, right? We don't produce anything in Antarctica, it's too cold, we don't produce anything in the Sahara, it's too hot. But warm up a little bit the northern reaches of Russia, we start to see some economic production, right. Similarly, with Sahara cooled off a little bit, we start to see more economic production. So, our basic findings are built on this insight that if you're really cold to start with, if you warm up a little bit, that could benefit you. If you're really hot to start with, you see the opposite effect is likely to harm you. And you're absolutely right that in colder countries, Scandinavia, Russia, Canada being good examples, if you warm it up a little bit, we see clear historical evidence that this has small but meaningful benefits in these economies.

CURWOOD: And then looking over the horizon at the much larger increases that are being forecast if we continue with business as usual. Even if we get the brakes on climate disruption, things are likely to get really bad for those poor countries. But how far is it to say that the richer countries will start to maybe see their economic advantage here start to diminish as well?

BURKE: Yeah, I think that's right. So, what we see in the historical data is it looks like there's an optimal temperature for economic production. So again, if you look at data from around the world, from all countries in the world over the last half century, what these data tell you is that somewhere between 10 and 15 degrees Celsius seems like the best temperature for producing things. That's just where we're at our most productive. And no coincidence, if you just look in the US, some of our most productive areas, or cities fall right in that window. So, Boston, Massachusetts, where you guys are, that annual average temperature is something like 11 degrees Celsius, which is about 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Bay Area where we are is about 13 degrees Celsius, or 55 degrees Fahrenheit. And that actually, we find, is the global optimum temperature for producing things.

CURWOOD: The Goldilocks Range.

BURKE: The Goldilocks Range, that's exactly it. So, what that means is you take a place like the Bay Area, and you warm it up three or four degrees, or five degrees, as you say, like we're going to get in the future, that's going to push us off this optimum. And that's going to likely generate, especially over the long haul, pretty negative impacts on our economic productivity.

Recent studies show that rising global temperatures intensify global inequality. (Photo: Flickr, World Meteorological Organization CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: What countries seem to be getting hit the hardest economically by climate change based on this research?

BURKE: So, the countries hit the hardest are the countries with the highest annual average temperatures right now. So, this is a lot of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of South Asia and Southeast Asia. In our analysis, these would be the countries that have suffered the most so far under the increases in temperature that we've seen. Again, many of these countries have performed reasonably well, economically. Southeast Asia has grown quickly, South Asia recently has grown quickly, parts of sub-Saharan Africa are growing quickly. So, climate is not the whole story here. But what our evidence suggests is these countries would have done even better had it not been for the warming that we've seen over the last few decades.

CURWOOD: What relationship, if any, might there be between those temperatures and the difficulties in places like Guatemala and Honduras, and even parts of Mexico that are contributing to the outflow of people from those countries?

BURKE: Yeah, that's a great question. So, there's pretty strong evidence in the literature that, again, if you're in a pretty hot place to start with, you increase the temperature, you often see substantial out-migration from those countries. And this has been shown in Latin America, it's been shown in sub-Saharan Africa, which again, I think is very consistent with your question, Steve. So, you crank up the temperature, people are less productive, and they want to go somewhere else where they can be more productive, right? And so, in Latin America, or Central America, they often go north. In sub-Saharan Africa, they go north as well. So, you see a large increase in the number of asylum applications in the EU, for instance, in years in which sub-Saharan Africa is hotter than it normally is.

CURWOOD: How do you think your research affects the perceptions of the difficulties of poor countries dealing with climate disruption?

BURKE: Well, our hope is that it puts numbers on this very important issue. I mean, I think a lot of people have the intuition that poor countries are likely the most harmed by changes in climate. But to make informed policy decisions, we really need numbers around that. How much harm has already occurred? How much harm might happen in the future? Right? We need to know the size of the problem before we can figure out how to allocate resources to address the problem. So, what our study does and what studies like this do is put numbers on it. And again, the hope is that this will inform better policy decisions about what sort of agreements we should come up with, what sort of financial transfers need to be made from rich countries to poor countries.

CURWOOD: Now, what optimism do you have for this trend for this disparity between rich and poor nations with the force of climate disruption changing things? What optimism do you have for this trend to turn around?

Marshall Burke is the deputy director of Food Security and the Environment at Stanford University. (Photo: Courtesy of Marshall Burke)

BURKE: One point of optimism is the success that many developing countries have had in recent years in developing their economies. Some of the fastest growth rates in the world, or most of the fastest-growing economies in the world are in the developing world right now. China being the best historical example, but many other countries have performed similarly over the last few decades. And so, I think that's the biggest source of optimism. A lot of these economies are growing pretty quickly, even in sub-Saharan Africa, which for decades’ experience very slow or even negative economic growth, many of these countries are growing quite rapidly. And again, that has nothing to do with climate change, right? Those are things that are happening completely separate from anything going on in the climate system. Where I'm less optimistic is in what future changes in climate are going to do to those trajectories. Again, it's... climate is not destiny, it's unlikely that climate is going to completely reverse the progress that we've seen. But our results and our research would suggest it could slow it down substantially, right. And so, these places might keep developing, but they will do so much more slowly than they would have otherwise. You can imagine it as someone running into a headwind, right? They're still making forward progress, but they're making much less forward progress than they would have had the wind been at their back, as it has been in many wealthier countries.

CURWOOD: Marshall Burke is the Deputy Director of Food Security and the Environment at Stanford University. Thanks for talking with us, Marshall.

BURKE: Thanks, a lot, Steve. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Read the Inequality study here

- Learn more about Inequality study co-author Marshall Burke

- Find out more about Inequality study co-author Noah Diffenbaugh

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder/V.M. Bhatt/Sukhvinder Singh Namdhari/Joachim Cooder, “Isa Lei” on A Meeting By the River, Water Lily Acoustics]

Beyond the Headlines

Monsanto markets a popular herbicide called RoundUp. A series of recent lawsuits allege that RoundUp has had negative health effects on its users. (Photo: Salva Barbera, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. He's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: We're going to start by talking about an immense court judgment: $2 billion, billion with a B, against Monsanto for non-Hodgkins lymphoma caused to a husband and wife allegedly by Monsanto's pesticide/herbicide called Roundup, with key ingredient glyphosate.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, Monsanto was bought up by Bayer, and I gather that this lawsuit and others is causing them, well, a headache.

DYKSTRA: It's really serious for a mega pharmaceutical and chemical company like Bayer or “Bayer,” as it's known in its native Germany. And since the Monsanto merger a little bit more than a year ago, Bayer has lost an estimated 44% of its stock value, virtually all of that attributable to the vulnerability to herbicide lawsuits.

CURWOOD: And just how many of those herbicide lawsuits are out there?

DYKSTRA: Right now, there are literally thousands of lawsuits being filed against Monsanto and Bayer for alleged harm from glyphosate, the key ingredient in Roundup.

CURWOOD: But Peter, there's dispute over whether Roundup causes cancer, isn't there?

DYKSTRA: It's a mixed verdict. Right now, the US EPA has said that they could find no link between glyphosate and lymphoma. However, the World Health Organization of the United Nations lists glyphosate as a probable carcinogen.

CURWOOD: Okay, so what else have you found?

DYKSTRA: We have a redefinition of a term that was really popular on American TV about twenty years ago. And of course, I'm referring to the word "butthead," but we're not talking about the Beavis and Butthead character. The city of Montreal has redefined the name and concept for anybody who throws cigarette butts in the street as a "butthead" in a major new marketing campaign to clean up a real public nuisance.

Montreal has launched a new marketing compaign to combat litter from cigarette butts, labeling litterers “buttheads”. (Photo: Admanchester, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, so how big a deal are cigarette butts in Montreal?

DYKSTRA: They measured how many cigarette butts they picked up and cleaned off the streets over a six-month period. It was half a million cigarette butts. That's enough to fill 92 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

CURWOOD: And of course, once they get in the waste stream, they can wind up in the ocean.

DYKSTRA: They can wind up in the ocean. And even before they wind up in the ocean, research shows that cigarette butts contain lead and arsenic in some cases. And the reason that they're on cigarettes is to try and filter out some of the bad stuff. And that includes other carcinogens like benzene.

CURWOOD: Oh, my. So, what are smokers supposed to do with their butts?

DYKSTRA: Well, the first thing, having lost my dad and my sister to lung cancer, is maybe not smoke. And the second thing is if you do smoke, deal with them responsibly, which means putting them in a garbage can after they're fully extinguished.

CURWOOD: All right, let's look back in history, Peter. What do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: We'll go back to May 25, 1958. President Eisenhower is in a TV studio in Denver, Colorado. He theatrically waves a magic wand, and a couple thousand miles away in Shippingport, Pennsylvania, the first US commercial nuclear power plant is dedicated.

In 1958, President Eisenhower dedicated the United States’ first nuclear power plant in Shippingport, PA. (Photo: US Department of Energy, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: And what happened to that plant?

DYKSTRA: Well, it ran until 1989. It's been decommissioned. It provided power for some in the Pittsburgh area for many years. It was based and modeled after the reactors already in use by the US Navy in nuclear submarines, and also in aircraft carriers all designed by the notoriously quirky Admiral Hyman Rickover.

CURWOOD: Of course, naval reactors, those on boats, would have a natural emergency backup in case of a meltdown: the entire ocean.

DYKSTRA: Right, and Shippingport had only the Ohio River, and it was surrounded by cities like Pittsburgh upstream, and Cincinnati and Louisville downstream.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: Thank you. And there's more on our website, Living on Earth. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Up next – Trial in Monsanto’s hometown set for August after $2 billion Roundup cancer verdict”

- Fortune | “Bayer Has Now Lost Over 44% of Its Value Since Its Monsanto Merger”

- CBC | “11-year-old environmentalist wants to stop cigarette butts from washing into the ocean”

- Global News | “Montreal redefines the term ‘butthead’ in bid to cut down on pollution”

- American Society of Mechanical Engineers | “Shippingport Nuclear Power Station”

- Read about our coverage of a previous Monsanto/Glyphosate suit verdict from September 2018

[MUSIC: Afro-Cuban All Stars, “Fiesta de la Rumba” on A Toda Cuba le Gusta, traditional/arr.Juan de Marco Gonzalez, World Circuit/Nonesuch Records]

CURWOOD Coming up –an environmental lawyer in West Africa escapes assassination. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Afro-Cuban All Stars, “Fiesta de la Rumba” on A Toda Cuba le Gusta, traditional/arr. Juan de Marco Gonzalez, World Circuit/Nonesuch Records]

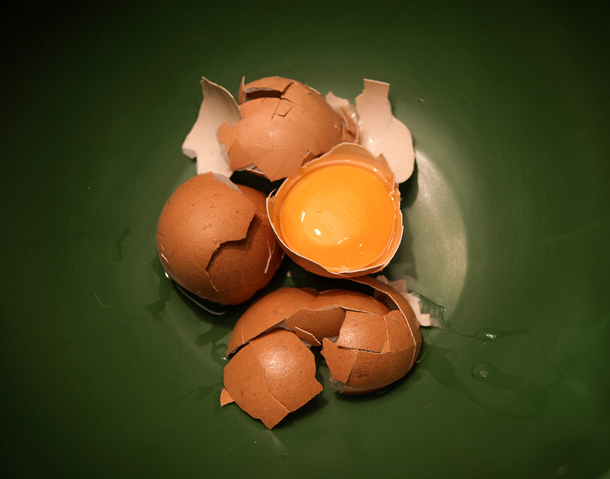

BirdNote®: Recycle Your Egg Shells to Help Nesting Birds

Female Robins need to consume calcium in order to lay eggs. (Photo: © Justin Oliver)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

Chickens put a lot of energy into producing strong egg shells and there are ways to reuse them. They can add calcium to compost, and in the garden, they are supposed to deter slugs. And as BirdNote’s Michael Stein reports, you can even recycle them for wild birds, especially in spring time.

BirdNote®

Recycle Your Eggshells to Help Nesting Birds

[American Robin song]

Birds’ eggs are among nature’s most elegant creations. But they’re not easy to make.

This American Robin will lay one egg per day for three to four days.

[American Robin call]

To make her eggs, the female robin has to use a great deal of calcium. But she can’t just pour herself a nice big glass of milk! She has to find her calcium in nature.

Dried chicken eggshells are a great source of calcium for nesting birds. (Photo: © Kevin O’Mara)

And it can be tough to find enough.

But we can help. During the nesting season, we can give the birds that visit our homes some of that crucial calcium.

Start off by putting calcium-enriched seed and suet in your bird feeders.

For the many species that don’t eat seed or suet—like robins—you can give them leftover chicken egg shells instead.

Rinse the shells off in the sink, spread them out on a cookie sheet, and bake them in the oven at about 250 degrees for ten minutes. You just want the shells to dry, not brown. When you’re done, crush them up.

Crushed eggshells can be mixed with birdseed and set out in a feeding tray or scattered right on the open ground.

And remember, always wash your hands after handling raw eggs.

[American Robin call]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Producer: John Kessler

Managing Producer: Jason Saul

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

Narrator: Michael Stein

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by Wil Hershberger.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2019 BirdNote May 2019

ID# egg-06-2019-05-14 egg-06

https://www.birdnote.org/show/recycle-your-eggshells-help-nesting-birds

Related link:

BirdNote® | “Recycle Your Egg Shells to Help Nesting Birds”

[MUSIC: The Beginning Of the End, “Funky Nassau” on a single, by Ray Munnings and Tyrone Fitzgerald, Alston Records and Atlantic Records]

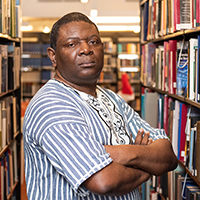

Saving West Africa’s Last Rainforest

Lawyer Alfred Brownell fought and won against Golden Veroleum Liberia’s attempts to take over indigenous land and wreck West Africa’s largest remaining tropical rainforest without due process. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: The winners of the Goldman Environmental Prize each year are nothing if not courageous. Many risk their lives to protect endangered species, rare natural resources, and indigenous land rights. Lawyer and human rights advocate Alfred Brownell of Liberia is the 2019 Africa recipient for his work to save over 800,000 acres of Liberia’s Upper Guinean rainforest from development into massive palm oil plantations. This rain forest and carbon sink is the largest in the region and nicknamed the “lungs of West and North Africa”. It’s a biodiversity hotspot and home to many indigenous people. Attorney Brownell’s conservation efforts nearly cost him his life as he battled Liberian government officials and the palm oil company, Golden Veroleum Liberia. And after he found a way to block the financing of the project he was forced to flee with his family to the United States, where he is now serving as a Distinguished Scholar at Northeastern University’s School of Law in Boston. Alfred Brownell joins me now in Living on Earth’s studios. Welcome.

BROWNELL: Thank You, it’s a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: You’ve risked your life to protect this forest, please tell us why you were willing to risk everything to guard it against the palm oil plantation folks?

BROWNELL: What more of an honor it is to fight for this planet, to fight for this forest, to fight for a way of life of people who are preserving it? It's a life worth giving. If no one is prepared to lay their life down, to fight to preserve Mother Nature, to protect this planet, to ensure that generations unborn will come and have a safe and healthy environment, and clean water and soil that is not poisoned by agrochemicals, and species in nature that are protected, that allow for generations unborn to perpetually and continually serve. If you're not able to give your life for that, then what cause you are able to stand up for? So I think I was always prepared to give that life, and even now I'm prepared to do that. The sort of threat we now face because of the way our forests and landscape are being destroyed, that is now warming of our planet, that is now creating the sort of challenges that the world now face -- drought, flood, forest fires, mass migration, poverty, and conflict. If the world and the planet is not worth the battle, if you are not able to stand up and allow yourself to be counted, and put your life on the line to fight for that, what else are you prepared to give your life up for? What is the meaning of your life? What is the meaning of your purpose on this planet?

Now living in exile in the United States, Brownell teaches at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Locally, in Liberia, why is the conservation of the Upper Guinean forest essential to the preservation of the local people who are there, the indigenous folks who are there, and their culture?

BROWNELL: If you flew over Liberia, all you see is the vast expanse of forests. It's like you are flying over an ocean of trees, green in color. It's actually one of the wonders of the world, to just see a continuous span of trees going over. And all that one will feel and think is that, these are just trees. And below them these are just animals. But a forest is also your home, to indigenous people. It represent their history, their culture, their tradition, their way of life. They refer to the forest as their supermarket, this is where they go and get the food. They refer to the forest as their pharmacy, this is where they go and have its medicinal plants. They refer to the forest as their university, this is where they teach the young people about the way of the tribes and the culture; how to become farmers -- and sustainable farmers; how to develop indigenous business enterprises. So over the years, they've learned how to coexist their life with nature, in a very sustainable way. That's why this forest is important. But much more than that, this is the last refuge of what west Africa once used to look like. If you went back in the times in West Africa, it was completed green across the entire region. Completely green, it was completely blanketed in green forests. The only portion of that blanket of forest in that entire region is what we now have in Liberia. It's the only intact forest. In other countries, they are all fragmented. So that's why it's important to protect this forest. It's the largest carbon sink in all of North and West Africa.

CURWOOD: So when you got concerned about this in a public way, what happened when you started speaking out against the Golden Veroleum Liberia company, these are the folks that want to do palm oil plantations, and you used your training as an attorney to, to launch a legal advocacy campaign against that firm. What happened to you?

BROWNELL: [LAUGHS] Well, of course they were not happy. I mean, this is a multi billion-dollar investment that has come. And the Government of Liberia had signed away massive amount of land. Think about that, 350,000 hectares of forest. That's as almost like, almost 800,000 acres of land, to this company. The government had not consulted the communities; the government had not even gone to do any kind of mapping of the land area. You know, it's how, you know sometimes elites in many other countries, you know, don't have respect for locals who have lived on this land, and just give this land to this company. And they went ahead and you know, said well, we have authority from the government and we want to take the land. And started to evict folks and clear away the land. And so my attention was drawn to what was happening. And I went and I saw what has happened; I was shocked, because I have seen entire towns and villages, completely bulldozed, by these companies. I have seen stream and creeks poisoned. I've seen people shrines, religious sites, their gods -- desecrated. I have seen people's burial grounds of their great warriors, their tribal chiefs, those who establish their towns and villages -- and like in the US it's talking about someone going in and desecrating the graves of -- what's the first president?

CURWOOD: George Washington.

BROWNELL: George Washington. And I'm wondering what Americans will say about that. Or it's like, to the African American, someone going and trying to desecrate the grave of Martin Luther King. What would they say about that? This is what these companies were doing to those people. Their entire history, their value, their way of life, their culture, their very essence, what made them indigenous people, was under threat and attacked by these palm companies.

Liberians discussing the threats oil palm developments are bringing to their land and indigenous communities. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So what did you do?

BROWNELL: So I had to act. So the first thing we did was, well, we felt, maybe this has been done out of ignorance, maybe there wasn't an awareness, the government didn't know about this. So at the local level in the region, we informed the local authorities, government officials; we moved into the cities; we went from ministries and agencies of the government to complain; organized massive press conferences, to draw attention. No one cared. They were in deal with the companies and was taking on destruction.

CURWOOD: So we're talking about the motivation of money here.

BROWNELL: Absolutely. This was not a venture that was intended to fail, it was too big to fail. This was intended to transform Liberia into a desert of oil palm. So we had to find a way to organize. The plan was to challenge just the grant of the rights, on the basis that the government of Liberia had no authority to give the lease rights to a transnational corporation, on land that indigenous people have existed on and occupied, even before the existence of Liberia.

CURWOOD: But how do you stop that? I mean, if the government is going to rule on any complaint that you bring forward, they're in charge of this process.

BROWNELL: Absolutely. Given how the government was involved in this process, and given that they ignored all of the pleas that we made, we felt that if we had gone to court, we probably wouldn't have prevailed.

CURWOOD: So what's the answer?

BROWNELL: And then a friend of mine said, Well, you know, Golden Veroleum is a member of an international consortium called the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, which is a certification body to ensure that palm companies were engaged in the sustainable production and marketing of oil palm.

CURWOOD: So your strategy is, this palm oil company needs to certify their palm oil as sustainable, because there are great concerns about this from Indonesia to West Africa. And so you went to this certification agency to tell them, uh-uh, this ain't sustainable.

BROWNELL: But certification is not just about a label that would give to them, you have to understand what the label means to the companies that are involved in the production.

CURWOOD: Okay, what does it mean?

BROWNELL: Because, given what has happened in Southeast Asia, given the alarming nature of how palm oil companies are operated in Indonesia and Malaysia, and the impact on the forest, and the species and orangutans -- it's creating alarm, it's creating concern, among activists, environmentalists, and social activists, and among consumers, and they demand for more sustainability. So it meant that many palm companies were not even having the financing to engage in production and to engage in the marketing. So they needed this label, to show to the banks, to investors, to shareholders, to their suppliers, to the consumers, that indeed they can get the financing to do this. And so we filed a complaint. We actually said, "We are open to an independent assessment and verification of the allegations we made." And they took the bait.

Alfred Brownell’s position at Northeastern University has given him a new platform and resources with which to fight oil palm developers’ attempts to take indigenous lands. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Ooh.

BROWNELL: Yes.

CURWOOD: So they came and investigated.

BROWNELL: Of course.

CURWOOD: And they found?

BROWNELL: And they found that we were right, every single bit. This is very important for our audience to understand what this is, because sometimes many folks will pitch this as development. How come poor villagers, living in misery and poverty, will have concerns about a multi-billion-dollar investment coming to their community, why are they opposing that? Don't they want a better way of life? But what many people don't understand is how this occurred on the ground. So imagine Golden Veroleum, for example -- a multi-billion dollar, the second-largest palm person in the world, going to poor villages. These villages, before the palm came, had their own palm. They had indigenous palm, they had their food crops, and the company wanted that. So the women, for example, had planted oranges, that they would sell every year, between the harvests. An orange tree will produce anywhere from between 8 to 12 bag of oranges. A bag of orange will sell for 10 U.S. dollars. So if a lady was able to harvest a tree of oranges, and had 12 bags, it meant that she had 120 U.S. dollars in her pocket. She would have that to support she and her family and her kids. The oil palm companies came and they didn't want that. They took away that tree, and guess how much they paid this woman.

CURWOOD: Nothing?

BROWNELL: 20 U.S. dollar per tree. Per tree. Not even the economic or market value. So what development is that, that will further impoverish people who already, out of their bootstraps, have engaged into entrepreneur activities? And so we had to act. And so, when those were established, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil wrote them and said, you have to stop further clearing, further development, and sit down and negotiate with these villagers.

In addition to a monetary prize, Goldman Prize winners each receive a bronze Ouroboros sculpture. Common to many cultures around the world, the Ouroboros, which depicts a serpent biting its tail, is a symbol of nature’s power of renewal. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: We're speaking with Attorney Alfred Brownell, Goldman Environmental Prize winner from Liberia and we'll continue with his story of protecting West Africa’s largest old growth rain forest after the break. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: King Sunny Ade, “Samba E Falaba Lewe” on JuJu Music, originally on Island Records (Now on Mango)]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We continue our conversation now with Alfred Brownell, the Goldman Environmental Prize winner from Africa who saved West Africa’s largest rainforest from palm oil development. In the middle of the fight the palm oil company allegedly tried to have Attorney Brownell killed.

The six 2019 Goldman Environmental Prize recipients participated in a ceremony on Friday, April 26th. From left: Belén Curamil Canio of Chile (on behalf of her father, Goldman recipient Alberto Curamil); Jacqueline Evans of the Cook Islands; Alfred Brownell of Liberia; Linda Garcia of Vancouver, Washington; Bayarjargal Agvaantseren of Mongolia; and Ana Colovic Lesoska of North Macedonia. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BROWNELL: And they try, they try to assassinate me, you know, their private securities. And this is very emotional.

CURWOOD: Tell me this story, what happened? Talk to me about the day that you understood that the assassins were coming for you What happened that day?

BROWNELL: Do you really want to hear this story?

CURWOOD: Yes, people should know.

BROWNELL: It's very personal... it's very personal. But you know, as a defender, I also know that there are many others who were not lucky like me, to be sitting down before you to tell this story. Many of my people, the communities I come from, as environmental and rights defenders, have paid the ultimate price. And bowed down and gone to see their ancestors. People like Berta and others, Ken Saro-Wiwa and others, who have died. And so in as much as this is very painful, I have actually made a commitment that I can be their voice, to keep echoing what, what this really is: the danger the defenders are facing. So as you will know, they were very angry. Now they have the stop order, and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil had instructed them to sit down and negotiate, develop a work plan and obtain the consent of communities. So they figure out that well, this certification board is based in Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. We are in Liberia in remote villages; we can ignore what they said and continue to do this. So part of our job was to investigate their compliance with this order. So when they told them to stop, they did not stop. They continue to take the land. They build much more strong relationship with the government. They pressure the government to put more pressure on us. So that's where the threats started to come in, from the government to us. That's where we're being labeled as anti-country, anti-development, anti-investment. My very citizenship was being questioned, that I was not a patriotic Liberian. How dare I challenge an investment that will build the infrastructure and generate revenue and create employment. But we kept reporting back to the certification body that Golden Veroleum was not following their order. And so they organize the first fact-finding mission ever done by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil to a country to ensure that one of his members was actually following their instructions. So when the team came to Liberia, we took them to a place called Tarjuowon, in Sinoe County. It was in fact an area where, after the stop order was issued, Golden Veroleum had identified that it would build a mill. It was on a hill which was referred to as Palloh Hill. This was a shrine, a religious site, of the Blogbo people in Sinoe Tarjuowon, the indigenous people, who every year, would go and pray and pay homage to their ancestors. It was so revered; it was so sacred. And this was where the company decided that they would make it the site for their mills. And so the local decided to show this to the fact-finding mission. So we went in, and we proved, we actually met the earth-moving equipment that were tearing down these shrines. And when I turned around to look at these community people, some folks just dropped on the soil. People were just crying, they were just crying, they just couldn't believe that their religious site, their shrine, had been completely torn apart. So unknown to us while we're doing that inspection, assessment, Golden Veroleum and maybe some actors in the government had decided that, well, we are really going too far. And that would have been the last day I was taking my breath, and so on our way back, as we came out of the operation area, we enter a town called Sinoe Town. We came across a group of men and there was a massive roadblock, they had logs on the road. And then our cars were all surrounded by these men. And they were going around shouting, "Where's the lawyer? Where's this lawyer, we are looking for Brownell! Where's the lawyer, we are looking..." And so they were searching for me. And then one of the guys said, "Here is Brownell." And then there was a shout from the crowd, they were so happy that they found their prey. And then, you know, they started threatening and trying to open the car doors, trying to puncture the tires, knocking the glass. These men were all dressed in the company uniform, they had the coats, they had the working tools from the company. And they started dancing, "Well, today is your last day." They were happy. Then I noticed that some other folks were sharing alcohol. So folks started to drink, they started to beat drums. And then some folks stared to put chalk, the traditional war dance -- in Liberia they have to the traditional war dance that the tribes would do.

Aerial view of an oil palm monocrop and the remaining forest in Sentabai Village, West Kalimantan, Indonesia, in 2017. (Photo: Nanang Sujang / CIFOR, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: You put chalk on your face.

BROWNELL: Chalk on your face. And some of the leaders came to the car and said, Well, you know today is going to be your end, you're never going to stop this company anymore. You know, we are going to, to eat your heart. We're going to take out your heart and eat it. And then someone say in fact, my boss is waiting for your skull. You know, he's going to turn it into a mug, he's going to drink his palm wine from your skull. And I was just being taunted, back and forth, they were dancing. And it was not easy. The colleagues who were in my car had all like given up. Some of the folks in the vehicle had already fainted. So I didn't know what to do. I just kept praying, what will happen? And I was just waiting for my time. Then they said, "Well, let's get the chief." Now this local chief was actually on the side of the company, we knew that he was one of the persons who was being paid by the company. It meant that if he gave his order, it meant that that was the end for us. So they went and they brought the chief. And he reached my vehicle and he knocked my windshield and said, "Roll down," -- I rolled down. And the chief said, "Are you Mr. Brownell?" I said, yes. He looked at me, and he said, "These people want to kill you. But I'm the chief. I don't know how that's gonna happen." And he turned around and said . . . [CRYING] he told them, he told them, "I'm not going to let you kill this man here. I'm not going to let you kill him. This blood must not waste on my land; this blood must not waste on my land. If you want to kill him take him to another town, but I am not going to allow you to kill him, and this blood will not be on my land." Then a young man who stood by him was very angry, and then he assaulted the chief and hit the chief. Then some of the young people from the village got angry that the chief had been assaulted. And there was conflict. The chief said, "Ah, so you insulted me. Then I'm going to remove the roadblock, and this car's going to go." And you know, they went and were fighting over the logs, tried to move that. And then we managed to flee the area. And we went to another village, where we stopped in a place called Buto, where we started our original campaign. And the company guys tried to chase out there and the Buto people came and said, "We're not going to allow you to touch our lawyer." We stay there for like, five days, protected by the indigenous people. Every night a movement from one house to another house in the night; people don't know who or where they would come but just like as in customs, trying to locate me. But the tribes protected me through all the time. And then they found a way to provide safety along the road back to the city. And we went, we came back to the city, we complain, we issue press statement. Couple of months later, my office strangers burglarize. I had electronic gadgets in my office, no one tried to take them away. There were DVDs, and phones, cell phones; I even had some money, some petty cash on my desk. No one took the money.

CURWOOD: What did they steal?

An oil palm stem, weighing about 10 kg (22 lb), with some of its fruits picked. (Photo: T.K. Naliaka, Flickr CC BY-SA 4.0)

BROWNELL: Documents, financial records. Then I started having strange vehicles following me. And then five years of bank records from my organization was taken. There were stories written to the media saying that I was corrupt, that I was using donor money to create a slush fund for myself. But I continued to persevere. And to be honest with you, I felt that it was worth the fight. It was worth the battle. And like I told you earlier on, if I faced the same attack again, I would go on. . . I'm embarrassed when I have to tell this story.

CURWOOD: Why?

BROWNELL: Because it makes me look like I'm weak.

CURWOOD: Courage is weak?...

BROWNELL: But I feel that it's important for the world to hear it. Because like I said before, I'm lucky to live, but I want the rest of the world to know what this is about. That an ingredient that you wouldn't even notice if you walk into your supermarket or grocery store, or you bought a bottle soap, or you bought chewies, or you went into McDonalds and you bought your fast food, or you went to Kentucky Fried and took your fries and your chickens. Or if you're someone who love lipstick, who buy lipsticks; or you love ice creams. You have no idea that oil palm is all over you. It's all over you. And while you are enjoying this -- both beautifying yourself and enjoying the flavor that it brings, and the happiness and joy that it brings to you and your family on this side of the world, it was raining destructions on another side of the world. So while you are beautifying yourself as a lady, there were women who were being flogged, who were being stripped naked, and chained in prison. There were the history, there was a culture, there was a religion, there were the shrines of people who have been desecrated. This is what the palm oil was doing to that country.

CURWOOD: So ultimately, of course, you felt that you had to leave. That it was just too much for your family and yourself and you came to the United States. But I imagine that the Liberian government is still trying to pursue this deal, still trying to pursue palm oil development, and other threats to the Upper Guinean forest. So now, from here in America, what kinds of legal or political strategies do you think could be used to protect the forest now from this development?

Orangutans in Borneo are quickly losing their habitat to oil palm developments. (Photo: Andrea Schieber, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BROWNELL: Well, so sometimes folks believe that they are threatening you. And maybe that's how the government of Liberia and the palm companies felt, when I left Liberia they felt they had won a victory with my removing, and they can do business as usual. But I think now they realize it was the biggest mistake in their life.

CURWOOD: Because?

Many if not most packaged products Americans consume contain palm oil. It’s found in lipstick, soaps, detergents and ice cream. (Photo: Rain Rabbit, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

BROWNELL: It was here in the US, it was here at Northeastern University School of Law. When I came and Northeastern University offered me a refuge and gave me a platform, a desk to continue my work in dignity. That's the idea -- when you go into exile, you lose everything. I left Liberia, just in one suit. The day my office was attacked by the police on the raid, I was not able to go back to my office, neither to my home. My family left in just the clothes they had on; I had to grab my kids, friends had to help me to take my wife and my kids along with me out of the country. And quickly fly me to a third country before I came to the US. But here in the US, at Northeastern, I had a platform. I had a group of students who was involved in my research, who are supporting with research. I had professors who were assisting me, I had an office, I had 24-hour electricity. I had 24-hour fast speed internet.

CURWOOD: So you can tell the story.

BROWNELL: So I could sit down and tell the story. I could sit down and continue to put pressure on the certification body. It was here that when the company launched its appeal against our complaint, that they lost. People put a lot of pressure on them. And so it was in August of 2018, a year and a half later, of sustained engagement, both supporting the communities directly in Liberia from a platform here in the US, using WhatsApp and other social media, working directly with the coalition head office that we were able to counter the appeal, and we won. And it is from here that I will continue pursuing those cases, to make sure that they are not going to take away that forest.

Alfred Brownell and his kids sharing a moment of fun in the snow. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Alfred Brownell is the founder and lead campaigner of Green Advocates International and this year's recipient of the African part of the Goldman Environmental Prize. Professor Brownell, congratulations. And thanks for coming by.

BROWNELL: Thank you. It's a pleasure.

Related links:

- About Alfred Brownell, 2019 Goldman Environment Prize recipient

- Watch: Alfred Brownell’s Goldman story

- Listen to our conversation with co-recipient Linda Garcia

- Listen to our conversation with co-recipient Jacqueline Evans

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, “The Curtain” on Sylva, Backed by the genre-crossing Metropole Orkest, Impulse Records]

Grammy Goes A-Gatherin’

Grammy and her dandelions. (Photo: Chris Fetter)

CURWOOD: Dandelions are one of the surest signs of spring and a promise of summer. They can also be a nuisance if you are working on a perfectly manicured lawn. But one person's grass-choking weed can be another's culinary delight. Ann Murray of the public radio program The Allegheny Front has this story on one longtime dandelion-lovin’ grandma.

CHRIS: I don't think you should walk over there.

GRAM: I can do it, come on buddy.

MURRAY: This afternoon, 97-year-old Virginia Dobell, a.k.a. Grammy, will not be deterred by some uneven ground and wild grasses. She's doing what she's done for the past ninety springs...gathering the season's first batch of dandelion greens for dinner.

GRAMMY: Look at this. This is like a bed of 'em.

MURRAY: So this looks promising?

GRAMMY: Yes, and if you tell me they're all red, I'll probably faint.

MURRAY: Red stemmed dandelions are a no-no for connoisseurs like Grammy.

Ninety-seven year old Virginia Dobell, aka Grammy, has loved dandelions for most of her life. (Photo: Chris Fetter)

MURRAY: If it's red, does it tell you that it's a bad taste?

GRAMMY: They're very, very bitter. OK, gotta have my knife, toots.

MURRAY: Grammy's grandson, Chris Fetter, pulls out a small kitchen knife from a paper bag. With considerable effort, Grammy hangs on her cane, bends over and starts cutting a big dandelion out of the ground.

GRAMMY: You always leave the base of the dandelion on...like so.

MURRAY: So what do you actually eat here? What part are we looking for to eat?

GRAMMY: Right there.

MURRAY: She points at the long light green, almost white dandelion stems and spines.

GRAMMY: They come in the tall grass. When they're about that tall...they're the yum yum ones.

MURRAY: Grammy should know. She's been rounding up dandelions since she was seven. Back then it wasn't just for fun. She and her big family depended on dandelions and potatoes for food all spring and summer. Just like the European settlers who brought the dandelion over here to fill out their paltry diet. The roots contain taraxacin, which stimulates digestion, and the leaves are full of vitamin A and D. Today, Grammy's passing on the tradition to Chris.

Grammy picks a plant. (Photo: Chris Fetter)

GRAMMY: You have to cut all the way around. Atta boy. See if you pull 'em up, you're in trouble. (Laughs)

CHRIS: I didn't do too good on that one.

GRAMMY: That's a white one, see. There you're talking sense.

MURRAY: While Chris cuts dozens of plants, Grammy tells me some dandelion pickin' stories. On one of her first excursions, her brother followed her to the family's apple orchard.

GRAMMY: So he gets in a tree and hides. When I get all my dandelions that I think's gonna do us for supper, I start for the house. And all of a sudden out of the tree he came. Grabbed my bag and spread the dandelions all along the way.

MURRAY: What a dirty trick.

GRAMMY: LAUGHS. Yes, a dirty trick it was.

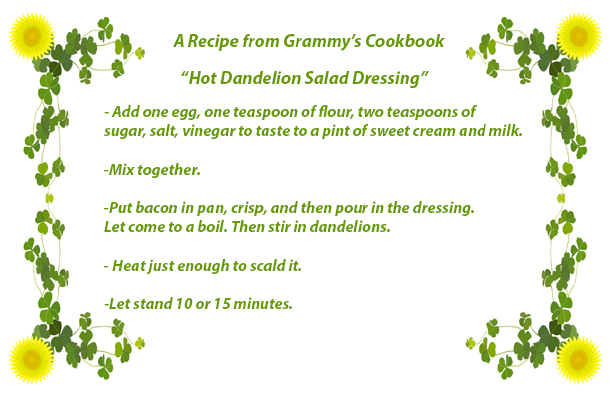

MURRAY: Dirty tricks aside, Grammy's been making dandelion salads for years. Back in her apartment, she thumbs through the well-worn cookbook her mother passed on to her in 1925. In the margin, her mom's written 'very good' next to the recipe for hot dandelion dressing.

GRAMMY: Of course, the first thing we do is fry the bacon and make that real nice crisp.

MURRAY: While Grammy gets the bacon going, Chris chops the dandelion greens.

CHRIS: Do you want to leave the leaves long, Grammy, or do you want them…?

GRAMMY: No, in half so they’re, you know, easy to eat.

MURRAY: After they finish up, they pull out a big pan and mix in milk, egg, a little flour and lots of vinegar.

CHRIS: Tell me when.

GRAMMY: That's good enough.

MURRAY: Then they pour the concoction in with hot bacon grease.

A recipe from Grammy’s cookbook. (Photo: Chris Fetter)

GRAMMY: And we keep stirring, stirring, stirring. Now we're going to put it on the salad and just swish and swish and swish. OK, it is ready.

MURRAY: Just in time for Sunday dinner. The table's set and Chris and his mom, Gloria, let Grammy take the first bite of dandelion salad.

GRAMMY: Ohhhhh it is good!!

CHRIS: Good job, Grammy.

GLORIA: Good job.

CHRIS: Tastes great.

MURRAY: This is Ann Murray.

GRAMMY: Oh heavenly days….

Related links:

- See a story from the LOE archives about a plant biologist’s love for dandelions

- Find out more about The Allegheny Front

[MUSIC: Eddie Pennington, “Over the Rainbow” on Eddie Pennington Walks the Strings…and Even Sings, by Harold Arlen/E.Y. Harburg]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joseph Winters, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth