June 7, 2019

Air Date: June 7, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

New Hampshire Fights PFAS Pollution

View the page for this story

New Hampshire may be one of the smallest states in the US, but it’s suing some of the largest chemical companies in the world for knowingly polluting the environment with the persistent toxic class of chemicals called PFAS and PFOA while failing to disclose the risks to public health. Now, New Hampshire wants DowDuPont, 3M and six other companies to pay for investigations, cleanup, and remediation of the persistent chemicals’ pollution. Host Steve Curwood and Vermont Law School professor Pat Parenteau discuss the lawsuit. (08:36)

Youth Climate Suit Plea

View the page for this story

June 4th, 2019 marked the latest effort of 21 young people to be able to call federal government witnesses and defendants to account in a trial of their climate change lawsuit against the US government. Attorneys for the plaintiffs and defendants in Juliana v. U.S. made oral arguments to a panel of three judges of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Host Steve Curwood has the story. (01:57)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstaView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood take a trip beyond the headlines to find some good news. First, they discuss an innovative technology that results in fewer wind turbine-caused bird deaths. Then, they examine initiatives around the world to decrease plastic pollution. Finally, the pair salute the birthday of legendary scientist and writer E.O. Wilson at age 90. (04:38)

Recomposing the Departed

View the page for this story

For most of recent human history, we’ve laid our dearly departed to rest through burial and cremation. But these can bear an environmental burden linked to land use and greenhouse gas emissions. Now, Washington State residents have a new green option: human composting, also known as natural organic reduction. Host Steve Curwood spoke with Recompose CEO Katrina Spade about the process of human composting and her mission to help families turn lost loved ones into fertile soil. (08:01)

Global Warming Clues from Henry David Thoreau

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

The Nineteenth Century writings of environmental philosopher and naturalist Henry David Thoreau are treasured not only by students of literature, but by today’s scientists as well. Boston University Professor of Biology Richard Primack is using Henry David Thoreau’s careful observations of New England in the 1850s to help track how a warming world is now affecting trees and flowers in the region. On a rainy spring day Living on Earth’s Don Lyman met up with Professor Primack for a stroll around Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts. (08:47)

Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

In the mid-nineteenth century, the nature writers and transcendentalists Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson shared a rich and fulfilling friendship, but it wasn’t always smooth sailing. A new book, "Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson", traces this complex relationship through the two writers’ journals and letters. Author Jeffrey S. Cramer is the curator of collections at the Walden Woods Project in Concord, Massachusetts, and sat down with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to discuss how the two helped each other grow as writers. (12:28)

BirdNote®: Henry David Thoreau and the Wood Thrush

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

In June 1853, Henry David Thoreau wrote of an enchanting encounter with the Wood Thrush: "This is the only bird whose note affects me like music. It lifts and exhilarates me. It is inspiring. It changes all hours to an eternal morning." BirdNote®’s Michael Stein has more on these awe-inspiring birds. (02:13)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jeffrey S. Cramer, Pat Parenteau, Richard Primack, Katrina Spade

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

The tiny State of New Hampshire is taking on the giant chemical companies that make PFAS and PFOA chemicals, linked to drinking water pollution.

PARENTEAU: They’re arguing that these products are unsafe, and that the manufacturers knew of some of the risks, and did not warn people, and did not take steps to actually try to find alternatives to these particular chemicals.

CURWOOD: Also, how Henry David Thoreau's observations near Walden Pond in the 1850s are helping scientists today.

PRIMACK: Plants are flowering about one week to about 10 days earlier now than they did in Thoreau's time. And the trees are leafing out about two weeks earlier now than they did in the past. And so this example from Concord, Massachusetts is one of the best examples of the effects of climate change that we have in a biological system from anywhere in the United States.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

New Hampshire Fights PFAS Pollution

Drinking water contaminated with PFAS chemicals has put hundreds of families in New Hampshire cities including Merrimack and Portsmouth on bottled water. (Photo: Thad Zajdowicz, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

New Hampshire may be one of the smallest states in the US, but it is suing some of the largest chemical companies in the world for knowingly polluting the environment with the persistent toxic class of chemicals called PFAS and PFOA while failing to disclose the risks to public health. Billions of dollars could be at stake, especially if other states join New Hampshire with similar suits against 8 chemical companies, including giants Dow DuPont and 3M. The chemicals involved range from no-stick compounds for cookware and pizza box liners to fire retardants, and once released into the environment they can contaminate water supplies for decades, for humans and wildlife alike. PFAS and PFOA exposure is linked to diseases including liver cancer and reproductive malfunction, and New Hampshire claims the chemical manufacturers knew about those dangers but didn’t inform the public or search for safer alternatives. Now the state wants the companies to pay for investigations, cleanup, and remediation of the chemicals’ pollution. Pat Parenteau is a law professor at the Vermont Law School. Hi Pat, welcome back to Living on Earth.

PARENTEAU: Hey, Steve, good to be back.

CURWOOD: So New Hampshire is suing some eight chemical companies that produce these PFAS compounds. By the way, what are these contaminants and where are they found?

PARENTEAU: They're found in just about everything. A lot of these chemicals are used in fire retardant foam and so forth, but you can find them in pretty much any consumer good you can think of. There are Teflon pans, they're used to line pizza boxes to keep the pizza fresh. So they're used in a whole variety of commercial products right off the shelf.

CURWOOD: And what's so bad about them?

PARENTEAU: Well, they are suspected carcinogens. They tend to, what's called bio-amplify up through the food chain. So they concentrate, they're persistent. And so once they're out in the environment, whether it's in the water or the air, they don't go anywhere. I mean, they concentrate, they aggregate over time, they move through the food chain. And you know, science is still trying to study the full effects of these chemicals. But what we know so far is that you don't want them in your food or your drinking water, for sure.

CURWOOD: And what's the particular issue with drinking water? This seems to be a real flashpoint.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, because once they get into a public water supply – there are like 150,000 public water supplies in the country – first of all, they don't have what's called a maximum contaminant level for these chemicals. EPA has been slow to set these MCLs, as they're called, and of course the Trump administration is dragging its feet. So we don't really have a national standard, a safety standard for these chemicals. So individual states are beginning to adopt them. And get this: some of these standards are measured in the parts per trillion. So that's how potentially toxic they are.

CURWOOD: Now, the State of New Hampshire has brought this suit as the state against these companies. What exactly is New Hampshire alleging here?

PFAS contaminants are found in many consumer products and they can leach into the environment. Landfills may contain an especially high concentration of the potentially toxic chemicals. (Photo: Alan Levine, CC BY 2.0)

PARENTEAU: They're arguing that these products are unsafe, and that the manufacturers have failed to disclose the risks associated with them. This is a typical story, Steve, we've heard this before, where the companies that are involved, Dow and many, many others, knew of some of the risks and did not warn people and did not take steps to actually try to find alternatives to these particular chemicals. So these are the kinds of cases, public nuisance, when it comes to contaminating water supplies, that can be litigated as a public nuisance. So you know, we've seen these kinds of suits with Monsanto and Roundup, where the juries in California have returned huge verdicts against Monsanto for the use of glyphosate in pesticides. States are beginning to flex their muscle in court to go after these major companies for damages and for money to monitor where the contamination exists, and of course, how to clean it up.

CURWOOD: Now, what's unusual about this lawsuit, if I have this correct, is that the State of New Hampshire as a state is bringing this action, as opposed to individuals who say they've been injured. What's important about that difference, if there is one?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so the state is using its powers of sovereignty with a doctrine that's known as parens patriae. They're acting, of course, on behalf of the public, both current generations and future generations, that will be exposed to these chemicals. Similar to what the states did with tobacco, similar to what some of the states are doing with climate change that we've talked about before. So these are not individuals, as you said, these are not class action lawsuits. This is, the state's basically saying, "We want these companies to come into our state and look at all the places in which we suspect there to be contamination." That would include things like landfills, because of course, when products are finally used up, they get dumped in the landfill. But these chemicals stay there and they come out over time into the water, into the groundwater. So you know, the state is looking for a really comprehensive remedy that – New Hampshire, I mean – they want their entire state, basically, to be investigated, at least those places where it's most likely you're going to find the contamination, and then figure out what you're going to do about it.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, in New Hampshire a lot of the impetus, a lot of the concern, was raised by people, in particular mothers, in the area of the former Pease Air Force Base outside of Portsmouth. But this lawsuit doesn't simply talk about that area, it's talking about the whole state.

PARENTEAU: The whole state, yeah, it's a generic lawsuit saying, you know, "We're a trust, the state is a trustee for all of the public water supply, and private water supply wells in the state. And we're not going to go one by one, that would take forever. We're going to want a global agreement with the companies if we can get it, or a verdict from the court if we need it, that orders a comprehensive approach to getting on top of this problem and cleaning it up."

CURWOOD: So what kind of money are we talking about here if New Hampshire is successful and other states decide to bring similar actions?

New Hampshire, a state that prides itself for its abundance of natural resources, is suing eight chemical companies for damages allegedly caused by a class of chemical compounds known as PFAS. The chemicals have leached into the state’s rivers, groundwater, and drinking water. (Photo: Stanley Zimny, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Well, New Hampshire didn't put a dollar figure on what they were seeking, because of course they're saying we don't even know enough about the extent of the contamination to put a number on it. But you can easily think about verdicts in the hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars. I'm thinking now that New Hampshire recently won an award against Exxon Mobil for MTBE contamination of water supply. That is the additive, the gasoline additive, that Exxon was using to meet clean air standards. And now that's turned up in water supply systems all across the country, so easily talking about hundreds of millions of dollars in verdicts against these companies, and probably approaching a billion. So I think New Hampshire is feeling pretty confident that they know how to litigate these cases against major companies and win them. So that may be a big reason for it, this Attorney General's office, you know, has had a fairly recent victory, 2015. And they're feeling bullish about it.

CURWOOD: So this particular lawsuit, brought in May of 2019, how soon might there be results from this, do you think?

PARENTEAU: That's a good question, I think you're looking at... I mean, the state is hoping to negotiate a settlement, obviously, but that'll take years. And as far as getting a trial and getting through all of that, that's going to be at least a couple of years with the appeals on top of that. So unless there's a settlement in the case, which I think is unlikely at this point, we're looking at several years before we see a final resolution.

CURWOOD: Why do you think it's unlikely that there will be a settlement?

PARENTEAU: Well, I'm sure that DuPont is terrified of setting a precedent, just the mere fact that the company is going to agree to pay even if they say we're not admitting liability, but in the interest of settling the case, we're willing to pay you to make the case go away. The minute that that happens, of course, there's going to be lawsuits all over the country. In fact, I wouldn't be surprised if even before we see the end of the New Hampshire case, there'll be other cases filed. I know that Michigan is looking at these issues, Wisconsin is looking at these issues. Vermont, my home state of Vermont, had this problem in an area of Southern Vermont around Bennington, Vermont. So states are lining up to bring these cases. And if DuPont ever shows the slightest inclination to settle them, I think they might as well get out the big checkbook.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a law professor at Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PARENTEAU: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- NHPR | “N.H. Sues Makers of PFAS Chemicals for Drinking Water Contamination”

- ABC News | “New Hampshire sues 3M, DuPont, other chemical companies”

- Environmental Working Group | “Mapping the PFAS Contamination Crisis”

- Pro Publica | Suppressed Study About PFAS: The EPA Underestimated Dangers of Widespread Chemicals

[MUSIC: Kavita Shah, “Tabla Interlude” on Visions, by Stephen Cellucci, Inner Circle Music]

Youth Climate Suit Plea

The 21 youth plaintiffs in the Juliana et al. v. United States case. (Photo: Robin Loznack, Our Children’s Trust)

CURWOOD: Back in 2015, 21 young people filed suit against the US Federal government on the grounds that it is not protecting them from the growing dangers of climate disruption. But the suit has yet to come to trial as the government has sought to throw it out on procedural grounds, resulting in four appeals seeking to keep the case alive. The latest effort spearheaded by attorney Julia Olson for the youth came before three judges of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals with oral arguments on June 4th. Jeff Clark of the Justice Department claimed the courts do not have the right to force the Trump Administration or Congress to act on climate.

CLARK: It is a case that is a dagger at the separation of powers. There are no logical stopping points in Ms. Olson’s theory. You can take that, you can apply it to any Clean Air Act situation because people breathe air pollution; they can die. They can have lung dysfunction. They can have other forms of health problems.

CURWOOD: Attorney Julia Olson offered an example of why the government is responsible for depriving the youth of their due process rights to a livable climate.

OLSON: Almost 25 percent of US emissions come from federal public lands. And when the federal government controls the system, facilitates it, subsidizes it, promotes it, as it does, that creates a claim for a substantive due process violation.

CURWOOD: The three judge panel seemed sympathetic to the cause, but as Judge Andrew Hurwitz explained, in this case, its unclear the courts have jurisdiction.

HURWITZ: You present compelling evidence that we have a real problem. You can make compelling evidence that we have inaction by the other two branches of government. It may even rise to the level of criminal neglect. The tough question for me, and I suspect for my colleagues, is do we get to act because of that?

CURWOOD: Both the youth and the Trump Administration now await a ruling from Judge Hurwitz and the other two judges on the appeals court panel, Mary Murguia and Josephine Staton, on whether there will be a trial.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Judges Give Both Sides a Grilling in Youth Climate Case Against the Government”

- Our Children’s Trust | “Juliana v. United States”

- Listen to Living on Earth’s earlier coverage of Juliana v. United States

[MUSIC: Robert Glasper, “So Beautiful” (Live At Capitol Studios) on Covered (Live), Blue Note Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A new, green alternative for laying our loved ones to rest. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Robert Glasper, “So Beautiful” (Live At Capitol Studios) on Covered (Live), Blue Note Records]

Beyond the Headlines

One criticism of wind power is the danger the turbines can pose to birds, especially endangered ones. A.I. technology such as Identiflight is working to decrease the bird deaths caused by these turbines. (Photo: Neil, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Well, it's time to take a look beyond the headlines now, with Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, how are you doing? What's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, let's start with something upbeat, and constructive, and solution-oriented, and positive. And that's birds being killed by wind turbines.

CURWOOD: Uh, this is supposed to be good news, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, yeah, because we're talking about reducing bird deaths in wind turbines. It's been something that anti-wind people, including the President, have invoked as a way of opposing wind power and clean energy. But the solution part of the story comes with a technology called IdentiFlight. It involves artificial intelligence, video monitors, sensors. They identify the kinds of birds that may be approaching wind turbines. And if it's something like a golden eagle, a bird that is under serious risk in a lot of the American West, the system can identify that bird and actually shut the wind turbines down.

CURWOOD: Well, that sounds good. How well does this work, though?

DYKSTRA: They're still getting the bugs out of the bird system. It's been deployed a lot of places, particularly in the American West, and the wind industry is looking at it with extreme interest.

CURWOOD: Hmm, well, that sounds pretty good. So, any more good news for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, we've solved the plastics in the ocean problem, or at least a tiny, tiny, tiny bit of it. The state of California became the first state in the nation to ban those tiny plastic hotel shampoo bottles. So we can all pop the corks on those tiny champagne bottles and celebrate.

California has passed a bill banning the small plastic toiletry bottles often used in hotels in an effort to reduce single-use plastic waste. (Photo: Ashley Ringrose, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Well, I don't know, Peter… But, you know, I have to say that I do find those little bottles annoying because you're at a hotel, you use, say half of the shampoo, or half of the conditioner, or half of the face wash, all the things that come in those little bottles. And then what do you do? Throw it away, which doesn't feel very good, or you take it with you, and then what are you going to do with it, then?

DYKSTRA: You develop a collection of half-empty shampoo bottles from hotels. It does reduce one thing from the waste stream, it helps maybe to make us a little bit aware of how we contribute to a huge problem like plastics in the ocean. But on the other hand, it does have a bad side, because it can anesthetize us to the larger problem, it can create the illusion that we've taken a big step towards solving ocean plastics, when we've actually taken just a tiny little step. Here's an example of a major step. The European Union has outlawed all single-use plastic items, grocery bags, disposable bottles by the year 2021. So having a single state bar a single plastic thing doesn't measure up to that. But let's hope it's the beginning of a major movement towards stemming the tide of plastics into our waterways and into our oceans.

CURWOOD: I can certainly agree with that. At this point in our gatherings, Peter, we typically look back at a note in history, and I'm wondering what you have today?

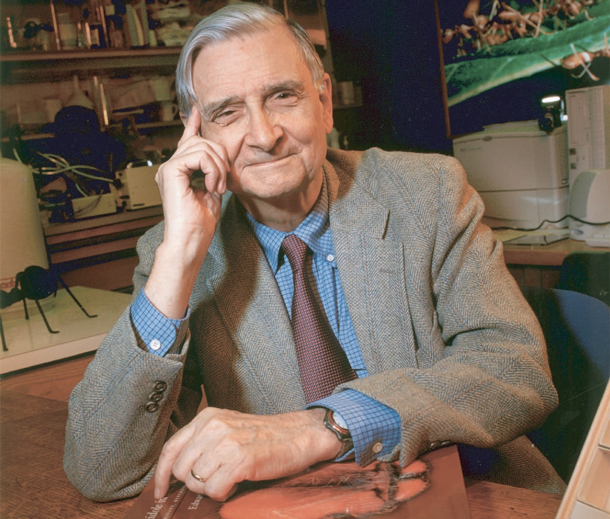

DYKSTRA: Well, how about a birthday party? June 10th is the 90th birthday of the legendary E.O. Wilson, the Harvard scientist who's won two Pulitzer Prizes for Nonfiction due to his fascination with ants.

CURWOOD: And his fascination with all the other creatures that we evolved with, which he put together in a hypothesis known as the biophilia hypothesis. That is, we evolve with everything else on the planet, so we need to have those creatures and those plants around us.

Harvard Professor E.O. Wilson is a biologist and author, sometimes called the “father of biodiversity”. (Photo: Jim Harrison, PLoS, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.5)

DYKSTRA: And thus he's taught us a lot about biodiversity. His two Pulitzers – one was for a book called The Ants. Starting as a young boy born in Alabama, he documented all the ant populations in the state of Alabama, found what is believed to be the first invasive population of fire ants that entered the US through the port of Mobile, near his home. His other Pulitzer was for an earlier book called On Human Nature, where he took and applied his fascination with ant and insect behavior, and used it to teach how humans behave in everything from everyday life to sex.

CURWOOD: In other words, we're not all that different from the ants, and the termites, and the bees, and everything.

DYKSTRA: Well, we're two-legged mammals. They're six-legged insects, but we can learn a lot from them.

CURWOOD: Oh, thanks, Peter. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these fairly good news stories at the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Revelator | “AI-Backed Sensors Help Reduce Wind Turbine Risks to Protected Birds”

- Mother Jones | “California Passes Ban on . . . Hotel Shampoo Bottles”

- The Guardian | “European Parliament Votes to Ban Single-Use Plastics”

- Read more about E. O. Wilson at The E. O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation’s website

[MUSIC: The Beatles, “Birthday” on The White Album, by Lennon/McCartney, Apple Records]

Recomposing the Departed

The process of natural organic reduction, or human composting, became a legal form of after-death care in Washington State on May 21st, 2019. This is an artist’s rendition of Recompose’s vision of their future human composting, death care facility. (Photo: Courtesy of Recompose, Credit: MOLT Studios)

CURWOOD: The ritual of bidding farewell to our deceased loved ones is an important step in the mourning process. Most of us are familiar with the traditional casket burials and cremation. But now there is a third option: natural organic reduction, or human composting. On May 21st, Washington became the first state to legalize this form of death care. Katrina Spade is CEO of Recompose, a company that helps people compost their loved ones into fertile soil. Katrina, welcome back to Living on Earth!

SPADE: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Now, the process of human composting is based on the principles of livestock mortality composting. So, talk to me about that and how it would translate for people.

SPADE: Well, I found out about livestock mortality composting back when I was a grad student in architecture school. And, it's this great practice that farmers have used for decades now in the US to recycle farm animals back to the land. And, it had never been done for humans before, but it seemed really like a great option. And, so, I started to investigate what it would mean to take that sort of agricultural process and make it feel meaningful and appropriate for humans.

CURWOOD: Just what exactly happens in this human composting -- or recomposing, as you say.

SPADE: The basic idea is we take a body and create the perfect environment around it, using natural materials like wood chips, and straw, and alfalfa, for microbial activity. My favorite way to think about this process is it's almost exactly what's happening on the forest floor, as dead organic material like leaf litter, sticks, and your errant chipmunk break down and become topsoil. What we're doing is basically creating that same process, but controlling it more carefully and accelerating it by providing all the right materials and the oxygen that those microbes need.

CURWOOD: And how long does this composting process take?

SPADE: So, the process takes about one month. And, that includes the breakdown of bones and teeth as well. It's pretty quick.

Katrina Spade is the CEO of the human benefit corporation Recompose. (Photo: Courtesy of Recompose, Credit: Craig Willse)

CURWOOD: From an ecological and economic standpoint, why is human composting a better form of burial than cremation or a traditional casket?

SPADE: The main reason I started to develop this idea was that neither cremation or burial felt particularly meaningful to me. I started to wonder what would my family do with my body if I died, and I realized they'd probably cremate me. But they would do so just because it was a default, not because fire is of particular meaning to me or my family. And by the way, the rates of cremation in the US are rising really fast. And, so, in Washington State, where I live, we have a 78% cremation rate. And in the US more broadly, it's rising very quickly. So we can assume that cremation is becoming the default for most Americans. And when I started to look into cremation, I realized it has a significant carbon footprint, and, you know, of course, uses fossil fuels. And so it just seemed to me like the last gesture we make on this earth -- well, for me anyway -- I didn't want it to be one that contributed more to the state of the world as it is.

CURWOOD: And, compared to the traditional burial, casket and all?

SPADE: There's definitely a carbon footprint with conventional burial as well. There's the manufacturer and transport of caskets and grave liners and headstones. I mean, the truth is, I believe everyone should have the choice that feels meaningful to them. So, I'm not saying that natural organic reduction should replace these other options. But, just that we should have an option – we should all have an option – that feels right for us.

CURWOOD: Now, human bodies do come with all kinds of chemicals. I know we're mostly water, but there are also some medicines, things of that nature, oh, there could be the odd piece of metal from a hip or knee replacement or something like that. With composting, these chemicals may get released into our environment. What's the process for dealing with that?

SPADE: Well, this is a great question, because one of the things we did early on was say, okay, we know from livestock mortality composting that the process of composting breaks down livestock on a molecular level. And so there's actually some studies showing that antibiotics, for example, that have been given to livestock do break down in the composting process. But, when we did a pilot with donated bodies at Washington State University, our questions were, what happens to pathogens, what happens to heavy metals, and what happens to pharmaceuticals? And we were able to kind of tick off, or check off each of those boxes – which was not surprising, like we expected that result. But it was very satisfying to see that, in fact, it's a very safe process. And, so, the first thing to know is for pathogens – you know, those are bacteria that cause disease – the process creates a great deal of heat from microbial activity, and that heat is what destroys dangerous pathogens. And so what we're looking for when we do a successful natural organic reduction is a certain temperature threshold, again, created by microbial activity, that destroys pathogens. And we saw this reached very quickly and many times over in our study. And when it comes to heavy metals, what we're looking to see is that the levels are way below EPA’s limits for heavy metals in soil. And we saw that as well, which again, wasn't very surprising, but was great to see. And then finally, the thing about pharmaceuticals, for example, is we have a big problem with pharmaceuticals in our environment, that has to do much more with wastewater and how we use the bathroom than it does with actual dead bodies. At the same time, we were really thrilled to see a 95% reduction of pharmaceuticals from the composting process. So we can say with confidence that natural organic reduction won't add to the problem of pharmaceuticals in our environment. This particular form of death care actually does solve that problem.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the amount of soil that human bodies can create and, and what you suggest people use that soil for.

Natural organic reduction, or human composting, is a process that only takes about a month in which loved ones are composted into fertile soil as a new form of after-death care. (Photo: Courtesy of Recompose, Credit: WSU Communications)

SPADE: Yeah, so, because the body is laid into a mixture of wood chips, alfalfa, and straw -- and it's quite a bit of that mixture -- we see a creation of about a cubic yard of soil. It's a lot. And what we're doing is creating partnerships with conservation lands around the Puget Sound area, so that if a family only wants a small amount of that soil, they can know that the rest of it is going to restore forest lands that need that. If a family wants all of that cubic yard and wants to go grow a tree on their own, that of course is great, too.

CURWOOD: You know, probably not everyone is comfortable even listening to our interview and a lot of people respond negatively to the notion of human composting like a banana peel or something. So, how do you approach this sort of “Jeez, sounds kind of yucky” mentality?

SPADE: Yeah, you know, I even hesitated to say the word dead bodies back there! But it can be hard, I think, to think about death and the care of bodies after we die, no matter how we're talking about caring for them. It can be a difficult thing to listen to. And I think when it comes down to it, if you look closely at any death care option, if you look closely at the process of embalming, if you look closely at what happens to a body in a casket underground, if you look closely at cremation itself, any of those things can feel a little uncomfortable. And so I'm sure that the same is true when people think about what is often called human composting. I've found personally that thinking about death on a daily basis has really given me a lot of joy in living life. I've been very aware over the past few years because I'm thinking always about death care itself. And, that's brought me an incredible, I think, perspective about how precious life is. So there's some beauty in talking about this stuff, but it can be very difficult.

CURWOOD: Katrina Spade is the CEO of the human composting corporation Recompose. Thanks for taking the time with us today, Katrina.

SPADE: Thank you so much for having me

Related links:

- Learn more about Recompose’s process here

- Learn more about the bill that legalized this form of death care in Washington State

[MUSIC: Paul Winter, “Bedrock Cathedral” on Canyon, by John Clark, Living Music]

Global Warming Clues from Henry David Thoreau

The fire cherry (Prunus pensylvanica) was one of many species for which Henry David Thoreau tracked both the flowering and leafing-out dates more than a century and half ago. (Photo: Dan Mullen, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: In the historic suburb of Concord about 20 miles west of Boston there is an oasis of woods and water made famous by writer Henry David Thoreau, called Walden Pond. Back in the 1850s Mr. Thoreau wrote his famous book, "Walden; or, Life in the Woods" about his time living there in a 150-square-foot, hand-built cabin. The volume has been an inspiration to nature writers ever since and includes detailed descriptions of his daily walks around the Walden Woods and the plants and animals he encountered. Today Henry David Thoreau’s writings are helping scientists who study how a warming world is affecting trees and flowers in New England. One of them is Boston University Professor of Biology, Richard Primack. On a rainy spring day Living on Earth’s Don Lyman met up with Professor Primack for a stroll around Walden Pond.

LYMAN: So Professor Primack, what are we looking for today?

PRIMACK: We've been doing a study for the last 16 years, where we've been repeating the observations made by Henry David Thoreau, the famous environmental philosopher and naturalist who lived by Walden Pond in the 1840s. And we're repeating his observations of when plants were flowering and leafing out in Concord, observations which he made in the 1850s. And we're seeing if they are doing the same things today that they were doing 160 years ago. So, you know, we're walking here along the edge of the beach, not far from the main beach area. And what we're doing here is we're looking at some of the plants that we are presently monitoring. And what we can see here is this is a plant that I'm actually specifically looking for, this is a plant that has silvery leaves, and the leaves are just starting to expand, I can see the shapes of the leaves. And this is a bigtooth Aspen, the leaves are all drooping down, but I can clearly see their shape. They'll expand over the next few days. And this is the stage that Thoreau would have recorded as leafing out. And then if you look over here on the edge of the beach here, we have these leaves coming up from the ground. These are three-parted leaves that look like clover, most people would look at them and think they're clover leaves. But in fact, these leaves here are the leaves of the yellow wood sorrel. And even though it's leafing out very well, it's not flowering yet. Should be flowering this time of year, but we've actually had extremely wet weather, over the last four weeks, we've had about the most rain of any April and early May that's ever been recorded in Massachusetts, it's very close to the record. So this is what we're doing on today's walk, we're looking for plants and seeing whether they are flowering yet and leafing out yet. And we're making the same observations that Thoreau made. And a lot of Thoreau's observations were made here right along Walden Pond. And in fact, he might have even been looking at the same, some of the same plants that we're looking at.

Walden Pond and the surrounding woods, including the site of Henry David Thoreau’s famous cabin, are now protected by Walden Pond State Reservation. (Photo: ashokboghani, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

LYMAN: When Thoreau was making his observations, how formal was he – was he keeping a journal, was he drawing pictures of things?

PRIMACK: What we think that Thoreau was doing is he was walking around, and he was making small notes on scraps of paper. And he made fairly detailed notes on his papers. And then he would come back and he would take these notes, and he would enter them into his journal in formal writing and sentences. And he would often create a lot of descriptions of things and make connections between things. And then what he began to do in the late 1850s, was to go back to his journals and extract out the flowering time and the leafing out information from his journals. And then he made these into formal tables, which are actually now held at the Morgan Library in New York. And so what we do is we compare our observations over the last 16 years with Thoreau's observations from these tables.

Stones marking the outline of Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond. (Photo: Mike Mahaffie, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

LYMAN: And what have your general results showed you so far?

PRIMACK: The general results have shown that plants are flowering about one week to about 10 days earlier now than they did in Thoreau's time, and that the trees are leafing out about two weeks earlier now than they did in the past. And so this example from Concord, Massachusetts is one of the best examples of the effects of climate change that we have in a biological system from anywhere in the United States. And we also see something else very distinctive, which is that if we look at the changes in the abundance of species in Concord, the species which have tended to decline the most in Concord are the cold-loving northern species, and the species that have increased the most in abundance in Concord are the warm-loving southern species. So we can see the signature of climate change in several different ways in Concord.

LYMAN: So how much has the temperature increased since Thoreau's time?

PRIMACK: Well, the temperature has increased by about two to three degrees Centigrade, or about four to six degrees Fahrenheit since Thoreau's time. Southern New England is actually interesting, because we've actually warmed up by about twice as much as the global average in ways that people don't really understand. So this region has had particularly a lot of warming. Thoreau also lived at the end of the period known as the Little Ice Age, so Thoreau lived at the end of a several-hundred-year period when the temperatures were actually much colder than they'd been before or since. The temperature warmed up over the next sort of 50 or so years after Thoreau's death. And then it kind of underwent a period of fluctuations for about another half a century. And then particularly starting around 1980, the temperatures in this region have been steadily increasing, probably because of climate change.

Henry David Thoreau tracked the flowering dates of yellow wood-sorrel (Oxalis stricta), which looks a lot like common clover. (Photo: David Short, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

LYMAN: So you said that trees are now leafing out about two weeks earlier than they did in Thoreau's time and wildflowers are leafing out about one week earlier than they did in Thoreau's time. Why would there be that discrepancy? Why are the trees leafing out two weeks earlier than 160 years ago because of climate change, but the wildflowers are only leafing out a week earlier than they used to?

PRIMACK: Don, that's a great question! So that's actually the main area of research of our group at the present time. So we think that the trees are leafing out faster because the branches can respond directly to air temperature, and air temperature can warm up very quickly. But it takes a couple of weeks extra for the ground to warm up because the ground is much denser, it has a lot of water in it; it takes a lot more warming to really warm up the ground so the wildflowers can start coming up. And so we think that the trees are more responsive to climate change than the wildflowers. This actually has a lot of interesting ecological implications. Because in the New England area, often the wildflowers – for example, things like the violets, and the anemones, the Columbines – they start leafing out earlier than the trees in order to get a period of full sunlight before the trees start leafing out and start shading them. So there was a period of about three or four weeks in Thoreau's time when the wildflowers came out before the trees started leafing out. And that period of full sunlight is actually getting shorter, because the trees are responding faster to climate change than the wildflowers. And that means that these wildflowers might not get enough energy in this early, full-sunlight period in the early spring in order to take their flowers and mature them into fruits. And if the wildflowers can't mature their fruits, they can't make seeds, then that prevents them from getting the next generation. And that will lead to the long-term decline of wildflowers in Concord and, we think, in really a lot of other regions in the northeastern United States.

LYMAN: So to what extent does the connection with Henry David Thoreau help you communicate your findings, your research findings, to the public?

On a trail not far from the site of Henry David Thoreau’s cabin, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman (left), Walden Pond State Reservation Interpreter Jacqui Kluft (center), and Boston University Professor Richard Primack (right) discuss the enduring legacy of Thoreau’s writings. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

PRIMACK: People have read "Walden" or they've read various writings of Thoreau, so by connecting Thoreau to this issue of climate change, it really helps me and my colleagues reach a much wider audience. Thoreau, in the book "Walden", has a couple of themes like observing nature very closely, living simply, becoming very actively involved in the critical issues of the day. And these are really the same types of ideas that we really need to deal with this issue of climate change. The really, the answer to dealing with climate change is that for us as individuals, and as a society to use less fossil fuels, to be more aware of how we're impacting the environment; also, that if we go out and we start making very careful observations about when plants flower in the spring, when the birds leave in the autumn, we can also see the effects of climate change right around us. All of us can see it, no matter where we live in the world. And also, the way to deal with the problem of climate change is to be actively involved in the political process, to join political parties, to write letters, to interact with people in groups, because it's really a global issue, which we need to be involved in as individuals, but only when we as a society grapple with the problem, will really the problem of climate change be solved. So there are very strong connections between what Thoreau was doing in his time and the book "Walden" and the present issue of climate change.

CURWOOD: That’s Boston University Professor Richard Primack speaking with Living on Earth’s Don Lyman at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Boston Globe | “Can Thoreau make us care about wildflowers?”

- About the Primack Lab

- The Journal of Henry David Thoreau

[MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “Minstrel Boy”, Traditional melody/Thomas Moore]

CURWOOD: Coming up: a new book takes a close look at the friendship between Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “Maple Leaf Rag” by Scott Joplin]

Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Walden Pond in Corcord, MA was a source of inspiration for nature writers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. (Photo: Flickr, Mike Mahaffie CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Henry David Thoreau might never have built his tiny cabin at Walden Pond or written his classic book "Walden" if it weren’t for Ralph Waldo Emerson, his mentor, friend, and fellow nature writer. While a student at Harvard, young Henry came across Mr. Emerson’s essay on nature.

MAN READING FROM “NATURE”: In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes), which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, all mean egotism vanishes.

CURWOOD: While Ralph Waldo Emerson is little read in the 21st century, his thoughts are echoed in Henry David Thoreau’s "Walden", which is widely read by high school students today.

MAN READING FROM "WALDEN": I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

CURWOOD: Jeffrey Cramer is the curator of collections at The Walden Woods Project, a non-profit dedicated to protecting the woods surrounding Walden Pond where Mr. Thoreau lived deliberately. And Jeffrey Cramer has a new book called "Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson". He spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Living on Earth producer and reporter Jenni Doering sat down with "Solid Seasons" author Jeffrey S. Cramer. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

DOERING: Why did you decide to write a book about the friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson?

CRAMER: I've never quite been happy with the way the friendship has been portrayed in biographies. So, I felt that it was time to really bring out the personalities of both men, to make them more human rather than iconic, and to tell their story.

DOERING: So, why did you call your book “Solid Seasons”?

CRAMER: So, I did that because there was a phrase that Thoreau used in "Walden" where he said, “there was one other with whom I had solid seasons, long to be remembered at his house in the village.” And he's talking about Emerson and he's talking a little bit about a rift they had in their relationship at one point. But, what surprised me was, I found that same phrase in a letter that Emerson had written to Thoreau from New York, in which he said, “I have had what Quakers call a solid season, once or twice.” And, therefore that phrase, “solid seasons”, was something that Thoreau picked up from Emerson. So, I just love that they both use that one phrase, to talk about those kinds of very strong and powerful personal friendships. And, what I take it to mean, and I think it's certainly how Emerson and Thoreau both used it, was that the solidity of the friendship, the strength, the power of that, and that's something that's so rare. So to have that season of friendship, whether it's short or long with that kind of powerful solidity was just an amazing thing.

DOERING: When did they first meet?

CRAMER: They met sometime after Thoreau graduated from Harvard. There are a few different stories. So they may have met shortly before that shortly after, but they met primarily because people noticed connections between Thoreau's early writings and Emerson's, and they brought them to Emerson's attention. And he took Thoreau into their household, ostensibly as a handyman, but also to help with editing Emerson's works and to learn more about the whole writing process.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, you write in your book how people were talking about Thoreau as imitating Emerson. To what extent do you think that was true, or just an impression?

CRAMER: I think it might have been true, but not conscious. So I think definitely there were things in Thoreau's mannerisms that may have been unconsciously trying to imitate Emerson, whom he admired. I don't think it was something he set out to do. I don't think he tried to be Emerson in his writings. I don't think he meant to start looking like Emerson as people claimed he did, or talking like Emerson, but I think it was just something that happened.

"Solid Seasons" provides new insight to the friendship between Emerson and Thoreau. (Photo: Courtesy of Counterpoint Press)

DOERING: I mean, their relationship wasn't uncomplicated, right? And, I think Thoreau had a lot more angst maybe than Emerson about it, from what you write. So, what was the issue there? What came between them? And why was there such a concern about, is this really the friendship that we want?

CRAMER: Yeah. So, both men I would say had ideals about what a friend should be. Thoreau seem to have put all of his faith in one person at a time. So, the friend, the ideal friend he wanted, particularly after his brother John had died, seemed to be Emerson. And so Emerson disappointed him in various ways along the times of their friendship, particularly in relation to his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, that Thoreau felt that Emerson should have promoted more. Emerson, however, didn't try to find the one ideal friend in one person, he found different aspects of that ideal friendship in many people. So Thoreau was just one of the many friends that Emerson had; although, certainly later in life, he kept referring to Thoreau as his best friend. So it became something greater than I think Emerson realized at the time when both men were alive.

DOERING: That actually reminds me about the fact that reading your book, it sounds like Emerson, just, his respect for Thoreau, after Thoreau had died, just kept growing until the end of his life or you know, near the end of Emerson's life. That he recognized what a great soul the world had lost, a great writer. Why do you think that that sort of transformation happened for him? Or can you characterize that?

CRAMER: Well, I think one of the things is Thoreau could be annoying. He could be a difficult friend. As one friend said, “I love Henry, but I do not like him.” So I think sometimes when you would have Henry in the room with you, it would, might be difficult to actually hear some of the things he's saying. I think when Thoreau died, and Emerson started reading his journals very carefully, and all of his writings again and again and thinking about him in relation to writing his eulogy, but other things – I think he realized what Thoreau offered the world. And at that point, the personality, the things that could be annoying in the friendship, were gone. And all he’s left with is the brilliance of Thoreau's words and writing, as well as the love that still remains in his heart for his friend that he lost. So I think at that point, he could really start thinking about Thoreau in a different way. And, as you mentioned, over the next 14, 15 years of Emerson's life, he really spent all that time talking about Thoreau, and people would come to visit Emerson in Concord, and he would say, you know, “let's not talk about me, let me tell you about Thoreau.” And it was just so interesting to see that. And he realized also that a lot of his own ideas, which had been represented in Thoreau's writings, or were very similar, Thoreau took them to a greater degree, and Thoreau tried to live that life. And Emerson was more on an intellectual level. He wrote about things; I don't think he felt them as deeply as Thoreau did. And I think that's one of the reasons we connect with Thoreau now and not Emerson is that we feel that there is a person who is speaking directly to us. And it's why so many Thoreau scholars, when they write about Henry, or talk about – I just did it – why we start calling him “Henry” and not Thoreau, but nobody ever calls Emerson “Waldo”.

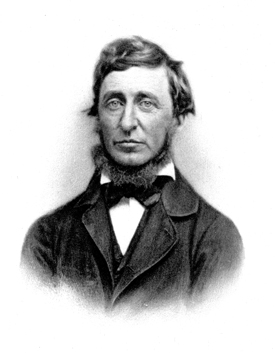

Henry David Thoreau is widely known for his works "Walden" and "Civil Disobedience", as well as many others. (Photo: Courtesy of the Walden Woods Project)

DOERING: So, you mentioned that after Thoreau died, Emerson started reading his journals. But we now have both of their journals. What do you think they would have thought about their private thoughts being read by all these millions of people now?

CRAMER: Well, the journals in those days were not quite the same as a diary today. So they weren't as private, they did get shared, you might actually loan your journal to a friend. And so it wasn't quite the same. But there were certainly remarks in both men's journals about the other person that may have been difficult for Emerson to read, certainly later on, as he's reading what Thoreau had to write about him. But overall, I don't think they wrote things knowing that the other person would read them and as a form of criticism that they should read, but I think they used it as a place to put down their thoughts and if the other person happened to read them at some point in time, so be it.

DOERING: What kinds of surprises did you come across in writing this book?

Ralph Waldo Emerson was known to be a mentor to Thoreau, but he was greatly influenced by his mentee as well. (Photo: Courtesy of the Walden Woods Project)

CRAMER: The surprises that I came across was, for me, how much Thoreau influenced Emerson. I mean, it's, it's obvious in every biography that Emerson influenced Thoreau. What I found was, and this was surprising, was how much they worked off of each other and shared ideas and grew from that exchange. One of the other things was, as I put the book together, I would put all their writings about each other in chronological order. So I could sort of get a better picture, which didn't quite exist when you read each man's work separately. And what I found was that at certain points when they're out together on the pond, or in the woods, having a conversation, when they go home, and they're both writing in their journals about the same experience, how do they write about it? And I remember one particular time where Emerson finished his first book of essays, which contains the essay “Friendship,” and they went off to Walden Woods for a picnic. And they’re both having a nice time and they go home, and Emerson's writing, you know, it's a lovely day, the sun on the water is beautiful, and our friends are nice and blah, blah, blah. And Thoreau goes home and he writes, Friendship is horrible! People suck! And he goes home and he's ranting about what is not right about his friendship with Emerson; I'm thinking, you two just spent like an hour or two in the woods, having the same conversation with each other, seeing the same scenery, and you both go home and write completely different things. Those kinds of things don't show up unless you start merging all of their writings together, which is what I had to do to create this book.

DOERING: I mean, and they seem to have a different relationship with nature, although they were both writing about nature a lot and talking about it. But, Thoreau was the one who would go out and actually be more part of nature. I think Emerson was a little more cerebral about that.

CRAMER: Definitely. But, Emerson did love being out in nature. I mean, he would go for walks, he would go boating on the river with Thoreau, or on the pond. He spent a lot of time outside, but it wasn't quite to the level that Thoreau did it. I mean, Thoreau needed desperately to be outside three, four hours a day. It didn't matter what the weather was, that was part of his life, that was part of his work, that was part of his being. For Emerson, it wasn't the same, he enjoyed going out into nature and seeing nature, he enjoyed being out on the pond, he enjoyed going for long walks in the woods. But it wasn't that kind of same integral part of his life.

DOERING: They were both very independent thinkers, and you know had a, a strong moral framework. What do you think that they would think about sort of the political system we have today – and climate change, this huge moral dilemma that we're, we're facing?

Jeffrey S. Cramer is not only the author of "Solid Seasons", but also the Curator of Collections at the Walden Woods Project’s Thoreau Institute Library. (Photo: Courtesy of Tom Hersey)

CRAMER: Both of them were very involved in social reform and political things that were going on in the world in their day. But they also stayed out of it for a little bit. I mean, Emerson was often reluctantly drawn into various frays; once he was there, he was in it full heart. Thoreau, had no love for the political system, the political world. So he again, he stayed out of it as much as possible. For Thoreau, the idea of changing the world was through self-reformation. That we change ourselves, change how we live, we change what we're doing that affects other people or the world. That is how we make change. So, for him, if we're looking at global warming and climate change, what are we doing as individuals that are causing this dilemma, this problem, and he would change things in his life so that he's no longer contributing to it. And, so, he's throwing the responsibility for what is happening directly back to the individual. We cannot rely on other people to solve our problems. We have to solve them ourselves. There are a lot of people who say that's not going to work anymore. I mean, Bill McKibben's clearly said, you know, driving your Prius isn't going to save the world anymore. Still, if we all drove Priuses, it would. If we all did this or that it would change things. So Thoreau and Emerson would take that sense of we as individuals have to reform our lives. And, that's the way to change the world.

CURWOOD: That’s Jeffrey Cramer, author of "Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson", speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- "Solid Seasons: The Friendship of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson"

- More about Author Jeffrey S. Cramer

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Henry David Thoreau and the Wood Thrush

The Wood Thrush is a small, pot-bellied bird, recognizable by its reddish-brown top feathers and speckled underparts. (Photo: © Greg Miller)

CURWOOD: The two-million-word journal of Henry David Thoreau is full of detailed

descriptions of the nature in and around Concord, Massachusetts. And like many of us who get out into the pine woods at dawn or dusk, the naturalist was especially taken with the song bird called the wood thrush. Here’s BirdNote®’s Michael Stein.

BirdNote®

Henry David Thoreau and the Wood Thrush

[Wood Thrush song]

STEIN: Perhaps as much as any man, Henry David Thoreau enjoyed his walks in the woods. In June 1853, Thoreau wrote in his journal of an enchanting encounter with the Wood Thrush:

“The wood thrush launches forth his evening strains from the midst of the pines. [Wood Thrush song throughout quotation] I admire the moderation of this master. There is nothing tumultuous in his song. He launches forth one strain with all his heart and life and soul, of pure and unmatchable melody, and then he pauses and gives the hearer and himself time to digest this, and then another and another … ” *

About a week later, Thoreau wrote again of the Wood Thrush: “This is the only bird whose note affects me like music … It lifts and exhilarates me. It is inspiring . . . It changes all hours to an eternal morning.” **

Wood thrushes thrive in expansive forests, and though they face threats from habitat loss, protected areas offer a home for these inspiring birds. (Photo: © Patty McGann)

[Wood Thrush song]

Wood Thrushes thrive in large expanses of forest. And their numbers have declined as forests have been cut on their breeding grounds and where they winter, in southern Mexico and Central America. Yet nearly half of Wood Thrush pairs have two broods per nesting season, so given a chance, their numbers could rebound. Protected areas like Adirondack Park, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and Ozark National Forest give them that chance.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Song of the Wood Thrush provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by G.F. Budney.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org June 2018/2019 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# SotB-WOTH-02-2011-06-05

Quotations from: Henry David Thoreau “Thoreau and the Birds”. In Hay, John (editor). The Great House of Birds. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1996. p. 69-70. *June 14, 1853 **June 22, 1853

https://www.birdnote.org/show/henry-david-thoreau-and-wood-thrush

CURWOOD: For pictures, flit on over to our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more at the BirdNote® Website

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology | “All About Birds: Wood Thrush”

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder/Vishwa Mohan, “Isa Lei” on A Meeting by the River, Water Lily Acoustics]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joseph Winters, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, iTunes and Google play – and like us, please, on our Facebook page, PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth and you can find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth