December 27, 2019

Air Date: December 27, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

How the Border Wall Could Harm Wildlife

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Amid outcries about its immigration policy, the US government is moving forward with an expansion of the border wall with Mexico. Biologists are raising the alarm that the wall can be a dead-end for migrating animals, including some bird species. Host Bobby Bascomb reports from the border on how construction of the wall can disturb nesting birds and damage sensitive habitat. (13:59)

Bison and Sustainable Land Management

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Bison, which are native to the great plains of North America, have many ecological advantages over their cattle cousins, which were introduced by Europeans. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on ranchers in Mexico who are breeding bison to help the species rebound and manage their land more sustainably. (10:15)

Science in Danger at the US-Mexican Border

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Scientists working on the US-Mexico border face unique challenges when trying to study borderlands ecosystems, thanks to everything from outright harassment at the hands of Border Patrol officers, to tight restrictions on what natural materials can cross the border. They say it’s gotten much worse in recent years since the Trump Administration began advocating for a massive border wall as well as taking a hard line on illegal immigration and asylum seekers. Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb is producing a series of dispatches from the US-Mexico border and discusses the challenges of doing science on the border with Host Steve Curwood. (07:53)

Water Ranching in Mexico

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Bobby Bascomb visits acclaimed land preservationist Valer Clark at her ranch, Cahone Bonito, in Agua Prieta, Mexico. Valer has been a steward of dried up lands in Mexico and the southwestern US since she purchased this property in the 1970’s, and she’s dedicated herself to finding ways to restore and maintain it. Alongside Valer and other experts, Bobby explores this ecosystem, its history, and the methodology that strives to bring it back to life. (13:11)

BirdNote®: Lily-Trotters, Jesus Birds

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

The strange wading birds known as jacanas are nick-named "lily-trotters" for their ability to walk on lilypads. In Jamaica, they're known as "Jesus birds," because they appear to be walking on water — a feat made possible by their long toes. But that's not all that's cool about jacanas, and BirdNote’s Michael Stein tells us more. (01:36)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Michael Stein

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Ranchers in Mexico are looking away from cattle and toward bison to manage their land more sustainably.

PAULSON: Research indicates that bison meat is leaner and more nutritious than beef. Generally speaking, bison are considered hardier, more adaptable animals. They can withstand heat and cold better than cattle. And in fact I would say that they are the perfect North American animal, if there is one.

BASCOMB: Also, scientists working on the US-Mexico border are feeling intimidated amid the wall construction and crackdown on immigration.

SERRAGLIO: I do feel threatened in my office in downtown Tucson, because my organization has received death threats, you know, many times in the past because of the work that we do. And I fear that one of these days, somebody's going to walk into our office and shoot the place up.

BASCOMB: That’s this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

How the Border Wall Could Harm Wildlife

The border wall between the US and Mexico follows the hills and valleys of the rugged arid landscape (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood is away.

This week, we’ll be taking a look back at a series of stories we reported this year from the US-Mexico borderlands, starting on the US side where the Trump administration is hard at work on new border wall construction. The US border with Mexico spans more than 1900 miles from the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California to the Gulf of Mexico in coastal Texas. Over a third of the border, nearly 700 miles, currently has some sort of barrier or wall, and amid the controversy over immigration the Trump administration has pledged to fill in the rest.

To see what that might mean for wildlife in the region I went on a road trip along part of the wall in Arizona, starting at the base of the Patagonia Mountains, 60 miles south of Tucson.

[SOUNDS OF WIND]

BASCOMB: Thorny cactus with pink and yellow flowers dot the arid landscape. From this elevation it’s easy to see how the border wall perfectly mirrors the topography of the land, rising and falling with these hills and valleys. Except for a small break at a river, the wall extends as far as the eye can see to the West, some 40 miles to Nogales. But to the east it’s a different story.

SERRAGLIO: Up here on the hill we can look East here and see the point at which the border wall ends out there, it doesn't actually go up and over this really rugged terrain that crosses the border right here.

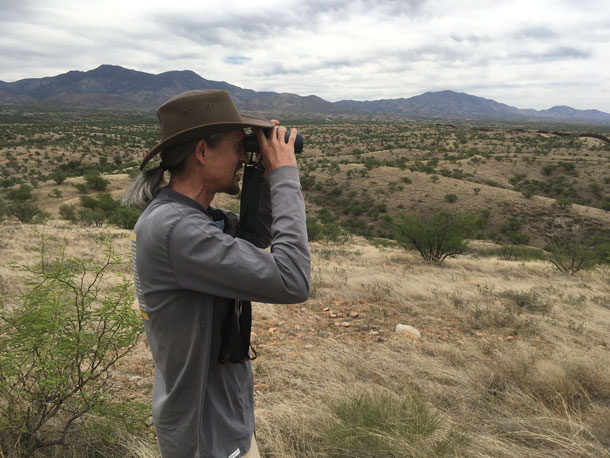

Randy Serraglio from Center for Biological Diversity looks across the landscape towards the US Mexico border wall. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Randy Serraglio is the Southwest Conservation Advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity. He’s tall and thin with gray hair pulled under a cowboy hat, and binoculars, at the ready, hanging from a strap around his neck. He says this break in the border wall is a lifeline for migrating animals, including jaguar.

SERRAGLIO: This is one of the handful of really prime jaguar movement corridors, places where jaguars can move back and forth across the border.

BASCOMB: Historically, jaguars ranged from Brazil's Amazon rainforest through Central America and as far north as the Grand Canyon. Today, only a handful of jaguar males are known to live north of the border, including El Jefe, or “the boss”, so named by local school kids. Randy points across the wall to the Mexico side of the border.

SERRAGLIO: He was born there and emancipated and came up here as a relatively young and vulnerable male Jaguar at the age of maybe two or three.

BASCOMB: Using camera traps, biologists were able to keep tabs on El Jefe for several years as he grew into a healthy adult while living in the nearby Santa Rita mountains. Then he abruptly disappeared.

SERRAGLIO: And biologists believe the most likely explanation is he came right back through here and went right back to wherever the females are, and then when he got to his breeding prime around the age of seven, he went back to wherever those females are. And that is critically important for jaguars, they have to be able to do that in order to survive, they have to be able to roam long distances and find territories of their own, and yet still remain connected to that core population. And that's why a place like this is absolutely essential for jaguar recovery.

BASCOMB: The borderlands in general are home to a huge variety of animals, including pronghorn, javelinas, ocelot, mountain lions, bobcats, Mexican Gray Wolf, black bears, and bison, to name a few. Dozens of endangered and threatened animal species use these rugged, barrier-free mountains as a highway for migrating between the US and Mexico.

The US border wall is strung with razor wire on the US side of the wall. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

SERRAGLIO: There's a herd of bison in the boot heel of New Mexico. And their favorite foraging grounds is on one side of the border and their favorite watering hole is on the other. So they often cross back and forth on a daily basis. But if there's a border wall built there, they won't be able to do that anymore. At a certain point, you fragment the landscape enough and you fragment the habitat enough and you isolate populations, and they start winking out. That's how species go extinct. I mean, we just know that for a fact.

[SOUND OF DOOR CLOSING, KEYS, ENGINE STARTING UP, CAR DRIVING]

BASCOMB: Randy and I pile into his pickup truck and drive a few miles down a dirt road to another type wildlife corridor. A lush green band of walnuts, willows, and cottonwood trees hint at the water that lies just below the surface.

SERRAGLIO: These are trees that rely on water, they have to have shallow groundwater in order to survive. So they only grow in these narrow stretches right along the river.

[CAR DOOR OPENS, GETTING OUT OF THE CAR SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: In the monsoon season this riverbed would be full of rain water. But it’s the dry season so we stand in the middle of the dusty riverbed to have a look around. Randy lifts his binoculars and points out a small brown and yellow bird.

[BIRD CALL]

SERRAGLIO: Oh, there’s a cute little fly catcher. Oh, yeah, look at that. They have a crest in their head. And so they'll perch out in the open like that. And then they'll fly out and catch bugs on the wing and then go back to the same perch again.

BASCOMB: Hence the name flycatcher.

SERRAGLIO: Yeah, they're very acrobatic, they're fun to watch.

BASCOMB: What are those two there?

SERRAGLIO: Those two are kestrels, and one of them had a lizard in its mouth. And the other one was chasing it. There, they just landed up in that tree there.

Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb at the border wall in Arizona. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Oh, like the other one is trying to get its dinner?

[BIRD SOUNDS]

SERRAGLIO: Yeah, that's why they were kind of whining. Like, whee, whee, give me that. It could be that that the one was a young fledgling flying around after mom or dad saying, feed me, feed me. And they're at the point where like, now you gotta start feeding yourself. Get a job.

BASCOMB: Tough love.

SERRAGLIO: Yeah.

[HAWK SOUNDS]

SERRAGLIO: That's the high plaintive call of a gray hawk, which is a beautiful hawk that lives in these riparian areas and nowhere else. So it's probably in that big giant cottonwood tree over there. Might even, might even have a nest, which would kind of be a disaster.

BASCOMB: A disaster because this riparian habitat teeming with life is also a construction zone. It’s Sunday, so the bulldozers and cranes are sitting idle, but Border Patrol is hard at work 6 days a week building a box culvert, a kind of small bridge, across this river. And Randy says all the noise, lights, and cleared land is devastating for wildlife.

SERRAGLIO: See that bank of high intensity lights over there?

BASCOMB: Yeah?

SERRAGLIO: -- with the shiny covers and everything --

BASCOMB: Yeah.

SERRAGLIO: I mean, that is completely disorienting for bats and migratory birds and insects at night. You've got these big dump trucks and cranes, and concrete mixers and all this other stuff going on here. And they've completely bladed all the vegetation. It's just this big, dusty, you know, wasteland now, it's like acres of just dust now, whereas before, it was this lush vegetation.

BASCOMB: Indeed, nearly all the birds we’ve seen are on the Mexican side of the border, which is lush and green with huge trees and a blanket of grass at the bottom of the riverbed. The US side is a dirt road, a pile of gravel, and heavy equipment.

The border wall needs constant maintenance and frequent upgrades. Those construction projects can be disturbing for wildlife in the area. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We can easily see into Mexico from here because instead of 18-foot-tall steel slats, which is much of the wall, the border here is simply a car barrier, waist high pieces of metal sticking out at 45-degree angles from the ground.

SERRAGLIO: When we have our summer monsoon, we have these big thunderstorms and the floods would knock this border wall down if they built it right through there. So instead, what we have here is vehicle barriers that are actually in the floodplain, in the riverbed, and they're this old school, Normandy style, cross hatch, you know, steel things, and they stop cars from driving through, but you know, people could climb right over.

BASCOMB: And so can wildlife. It’s relatively short with large gaps, which allow water to flow through as well as migrating animals.

SERRAGLIO: So vehicle barriers are much more wildlife friendly. And there's still a road that gets bladed, you know, when they have vehicle barriers, but they're not the kind of, you know, absolute obstruction that the border wall creates.

BASCOMB: Customs and Border Protection recently received 2.5 billion dollars for barrier replacements, which includes repairing damaged walls, but it also means “improving” the wall from these vehicle barriers, permeable for wildlife, to the full border wall, steel slats up to 30 feet high and a complete dead end for animals.

This section of the US side of the border wall is a construction zone to build a small bridge across a floodplain. Ecologists say the heavy machinery and disturbance to the land is detrimental for local wildlife. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

SERRAGLIO: They call it replacement barriers, and they're trying to pretend it's not a big deal. But it's a huge difference in the disruption that's caused between, you know, a border wall and a vehicle barrier in terms of wildlife.

BASCOMB: And it’s not just large mammals that can’t get around the wall. Even some birds, including the cactus pygmy owl, will have a hard time getting over a higher wall.

SERRAGLIO: The border wall would be a blockage for this animal because they rarely perch any higher than about 10 feet off the ground. And in some places, this bollard construction is going to be 30 feet tall. And so it will block migration of the cactus ferruginous pygmy owl. And again, this is a species that exists on both sides of the border. We have a small population remaining in the US, and there's also a small population in Sonora, and for those populations to be split, just makes it more likely that either or both of those populations will wink out. I mean, again, that's how species go extinct. You know, they become fragmented and smaller and smaller to the point where they're no longer viable.

BASCOMB: So the wall will be impassable for some wildlife, but Randy says, not necessarily so for the people it’s supposed to stop.

SERRAGLIO: There was a school group down here looking at the border a few years ago, and these two high school girls, they're like 16, 17 years old, they climb to the top of the border wall, free climbing in about 17 seconds. I mean, you know, it's not gonna really slow people down very much.

BASCOMB: The top of the wall was recently strung with spools of sharp razor wire, on the US side.

Construction on the US side of the border can be disturbing for wildlife. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

SERRAGLIO: They could put it on the other side, because actually, there's another 10 feet there of US property. It's on this side so people can see it. It's for show, this is for people to see to make it look like the military is doing something and be afraid. And it's this Mexican invasion, and oh, my God, we all have to be so scared and spend billions of dollars on this ridiculous monstrosity, you know?

BASCOMB: So if you are somebody trying to get over this wall it would make a heck of a lot more sense to put the razor wire on the wall on the side that you're scaling, not the side that you're jumping off from.

SERRAGLIO: Because I mean, if you really wanted to, you could, you could jump out over this and land right here.

BASCOMB: Yeah, you could you probably a little banged up. But you could do that easily, relatively easily.

SERRAGLIO: You might sprain your ankle, and a lot of people do. But you know, it's uh, it's just, the whole thing is just for show.

BASCOMB: That sentiment is echoed by Congressman Raul Grijalva, who represents Arizona’s 3rd District, including a 300-mile-long stretch along the US Mexico border.

GRIJALVA: The effect is going to be minimal, in terms of unauthorized people coming or going. It’s just, the wall is not the deterrent that Trump wants it to be.

BASCOMB: Mr. Grijalva is Chair of the House Natural Resources Committee. Nearly 60 percent of his state is public land and because of that, Mr. Grijalva says Arizona has been targeted for more border wall construction.

GRIJALVA: I think he put Arizona's public lands at crosshairs. And the reason the public lands are so susceptible, is because they're public. They don't get hung up like they are in Texas on the issue of eminent domain and takings.

BASCOMB: Mr. Grijalva says those large tracts of public lands are often critical habitat for wildlife and a source of revenue for Arizona. And a border wall puts both in jeopardy.

GRIJALVA: It's going to rip through two wildlife refuges, wilderness areas, a very fragile desert river and two units of the National Park Service: Organ Pipe, and the Coronado National Memorial. Both those brought in about 260,000 people and about 30 million to these local economies in terms of revenue and tax, and spending in the area. So one has to wonder what is the purpose? It's been part of a campaign strategy that everybody in the borderlands is going to have to pay for, and suspending and waving laws is a dangerous precedent for the rest of the country.

The Mexico side of the border wall is lush and green, habitat for numerous species of birds, mammals, and reptiles. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: The Trump administration invoked the REAL ID Act of 2005 to suspend dozens of environmental laws in the borderlands, including the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act and the Clean Water Act. Under normal circumstances, those laws could be grounds to sue the government and suspend construction projects. But the dozens of laws routinely cited to protect the environment and wildlife do not apply in the borderlands.

GRIJALVA: And that's what I think bothers us the most than anything else, that there is no -- the rationale for it doesn't fit the price tag and cannot justify the suspending of laws and more importantly, the long term harm that it does to the environment.

BASCOMB: Paul Enriquez is the acquisition, real estate, and environmental director in the border wall program management office for the US Border Patrol. He says it’s necessary to waive those environmental laws so the Border Patrol can meet their deadlines for wall construction.

Sections of the US side of the border wall are construction zones, full of heavy machinery and equipment that disturbs animals in the area. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

ENRIQUEZ: Getting the barrier up and ensuring and making sure that the Border Patrol has the resources, the tools they need to secure the border is what's the priority and why the expeditious construction is needed.

BASCOMB: But Paul says they still do what they can to work within the existing environmental laws, even though they are not required to do so.

ENRIQUEZ: The goal is not to just disregard those environmental laws that are waived, the goal is to ensure we're following the intent as closely as possible of those laws, working with the resource agencies that generally have the responsibility for executing those laws, like Fish and Wildlife Service.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Back at the border Randy Serraglio stops his truck at a scenic vista near the Coronado National Monument and looks across the rugged hills towards Mexico.

Southern Arizona, the way a jaguar sees it. The rocky landscape is a critical migratory corridor for animals in the Southwest. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

SERRAGLIO: Now you're looking at the world the way a jaguar sees it. He stands up here and he sees that mountain range over there. And he says, Yeah, I could get there tonight. And see that one over there farther away, I could be there by tomorrow night.

BASCOMB: But, of course, only if there’s not a wall blocking the way. The Customs and Border Patrol recently received 1.375 billion dollars for new wall construction in the Borderlands, including right here in the Coronado National Memorial.

Related links:

- Center for Biological Diversity

- Center for Biological Diversity on El Jefe

- Coronado National Memorial

- Arizona Congressman Raul Grijalva

- Customs and Border Protection

[MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Pan Eros” on Pan Eros, CMP Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Cattle ranchers in Mexico are looking back to bison for more sustainable land management. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Punch Brothers - Passepied (Debussy) From the Album The Phosphorescent Blues, Nonesuch]

Bison and Sustainable Land Management

Bison tend to graze on a wide variety of plants in open areas and encourage a diversity of grasses on the arid Great Plains. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

[MUSIC: Tom Roush, “Home On The Range” on Silver Threads Among the Gold]

BASCOMB: Ahhh … home on the range. Two centuries ago the Great Plains of North America from Canada to Mexico teemed with prairie dogs, pronghorn, and the bison or buffalo that inspired that iconic song. Today those herds of bison are few and far between, after massive slaughters, and grasslands were lost to agriculture. But from Alberta to Chihuahua, bison are coming back, and in Janos, Mexico I found a ranch that’s working to restore them.

[WIND SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: The great plains of Mexico are dry, mostly tan in color. But a bird’s eye view reveals dark brown squares of tilled land waiting to be planted and bright green circles -- irrigated fields of wheat, corn, or alfalfa. But for the spine of the Sierra Madre mountains, northern Chihuahua looks a lot like Kansas.

I’m here to check out the El Uno bison ranch near the town of Janos. Flora Moyer greets me when I arrive.

MOYER: Welcome, welcome!

BASCOMB: Thank you, so windy today!

MOYER: Janos is where the wind was born apparently.

BASCOMB: Really? It feels that way.

MOYER: [LAUGHS] So they say. So we have been weathering lots of wind these last few days. I’m Flora.

BASCOMB: Flora, I’m Bobby. Nice to meet you.

BASCOMB: Flora is the coordinator of the private lands conservation program for the nonprofit Fundo Mexico, the Mexican Fund. Holding her cowboy hat on her head so it doesn’t fly away, she leads the way out of the wind and into the El Uno ranch. Flora says it’s always this windy here.

Bison frequently roll on the ground and create small basins that hold moisture and serve as microhabitats for a variety of plant and animal species. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

MOYER: But what has been increasing are the dust storms. And so you’ll see sort of these dirt devils all around. Yesterday, you couldn't see the entire mountain range that's on the other side of the valley, which is not that far away, and pretty massive. And it just was completely disappeared behind the dust clouds.

BASCOMB: Those dust clouds are a result of years of cattle grazing and water-intensive agriculture on semi-arid land.

MOYER: These processes of desertification that come from the mismanagement of the land and the overgrazing that has resulted, so you have all this barren land, but also, because of all of the agriculture that has been brought in has loosened up all the soil that doesn't have vegetation for large periods of time. It's just been more and more that there are these events where the valley is just filled with dust.

BASCOMB: But Flora says Fundo Mexico acquired this property with the hope of addressing the erosion problem and at the same time promoting sustainable ranching.

MOYER: The goal of this property is to create a demonstration site where we set out from the beginning to have a working ranch operation that has conservation goals integrated into its operation. So we really want to be an example that neighboring ranches or other properties in the area, can look at and say, okay, if they can do it, then we can do it.

A group of females and calves at El Uno Ranch in Janos, Mexico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Like many ranches in the area, El Uno makes money from cattle ranching. But cattle, introduced by Europeans, can degrade land in ways their native cousins, bison, do not. Bison historically ranged from Southern Canada to Northern Mexico, west to the Rocky Mountains and possibly as far east as Florida and New York. Roughly 30 million bison roamed North America before white settlers arrived. By the turn of the century there were fewer than 600. El Uno is hoping to help the species recover while sustainably managing the land and turning a profit.

A tall order, but Pedro Calveron is up to the challenge. He’s the self-described ranch bison whisperer.

CALVERON: If you don’t know how to talk bison it really becomes a problem.

[TRUCK SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Pedro has a short black beard and wears a long sleeve plaid shirt with a brown handkerchief tied around his neck. His official title is ranch manager and I’m tagging along as he drives a pickup truck around the ranch to check on the herd. At more than 45,000 acres, El Uno is three times the size of Manhattan so we drive for a while before we find a large group of females and calves.

CALVERON: The one who is laying has his calf right in front of him, of her. And the other one is nursing their calf.

BASCOMB: We get out of the truck to get a closer look.

[DOOR SOUNDS]

CALVERON: OK, so just be quiet and don’t look the herd to the eyes. [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: Any other advice?

CALVERON: No, no just stay with me.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: He pauses to tie his cowboy hat under his chin so it won’t fly off in the wind. We walk through ankle-high brittle yellow grass towards the herd of one-ton animals and their babies.

Part of the El Uno Bison herd. (Photo Bobby Bascomb)

CALVERON: Can you see the bunch of newborns here?

BASCOMB: Yeah, they’re tiny. How old are those, you think?

CALVERON: The darker ones, more than a month, and the lighter ones around a week.

BASCOMB: Pedro says bison have two advantages over cattle when it comes to managing the land sustainably. First, bison tend to lay down and roll on the ground, which creates bison sized basins on the land, and that keeps more water on the dry landscape.

CALVERON: The moment that you have moisture, or rain, you are able to maintain the moisture in those basins.

BASCOMB: And those moist basins can create microhabitats for a variety of animals including burrowing owls. Some wildflowers and grasses that pronghorn antelope feed on also like bison basins. And Pedro says he’s noticed another advantage that bison have over cattle.

CALVERON: They are less selective than the cattle to eat vegetation so they’re going to graze more this kind of grass more shrubs than the domestic cattle.

BASCOMB: They eat the grass more indiscriminately so I would guess that you would have more different types of grass as opposed to a monoculture growing up.

CALVERON: Yup.

BASCOMB: So, do you think the bison then, do you think that they encourage a diversity of grass locally?

CALVERON: Totally.

BASCOMB: Pedro’s observations are backed up by many studies comparing cattle and bison. Laura Paulson is an independent consultant focused on sustainable ranching policies. She used to work at El Uno Ranch and says bison tend to roam more than their cattle cousins.

PAULSON: The bison make very large movements across the land throughout the day for grazing, instead of staying in one area like cattle do.

BASCOMB: Cattle tend to congregate near trees and water sources, and can lead to erosion in riparian areas. Bison prefer to graze in open areas and travel far in a day, creating those microhabitats, and leaving their fertilizer behind.

PAULSON: And then, generally speaking, bison are considered hardier, more adaptable animals. They can withstand heat and cold better than cattle. And in fact I would say that they are the perfect North American animal, if there is one.

BASCOMB: Indeed, President Obama declared bison our national mammal in 2016. And Laura says bison have at least one more advantage.

Pedro Calveron is the El Uno Ranch manager and staff “bison whisperer.” (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PAULSON: Research indicates that bison meat is leaner and more nutritious than beef.

BASCOMB: Bison meat is lower in fat and calories than beef and higher in protein. In the US bison are considered livestock. There are a few wild herds, mostly in public lands like Yellowstone and Wind Cave National Parks, where roughly 5,500 bison still roam free. But private ranchers graze far more bison as livestock. Ted Turner alone raises more than 50,000 bison, some of which end up on the menu at his restaurant chain, Ted’s Montana Grill.

South of the border, in contrast, bison are managed as wildlife and their sale for consumption is prohibited. It seems counterintuitive but Laura says there is a case to be made for opening up new markets for bison meat in order to save the species.

PAULSON: These are some of the public policy issues that do need to be looked at closely and really figured out how can they be modified in a way that perhaps would be a win-win for both the conservation authorities in Mexico as well as private landowners who are interested in working with bison.

[WIND SOUNDS FROM EL UNO RANCH]

BASCOMB: And that’s a question that Pedro at El Uno in Mexico is struggling with. He says the ranch can support up to 800 bison. But they plan to stop breeding them at just half that number and split the ranch evenly between bison and cattle. They need to turn a profit to maintain the ranch and to demonstrate to other ranchers how that can be done sustainably. But they also want to be leaders in the bison conservation movement.

CALVERON: We are right at the limit of the distribution at the South. So the genetic of the bison here in El Uno is already adapt to this desert ecosystem. So, looking at the big picture between Canada, United States and Mexico, and northern Great Plains and everything. If there is more interest or there is more initiatives to create more conservation herds, we are the ones who has the animals ready to be part of those conservation herds because they already adapt to these conditions on the desert.

BASCOMB: So, you already have some genetic diversity built in to offer to other ranches.

CALVERON: Yes.

BASCOMB: El is Uno is currently home to 206 bison and they expect have about 230 by the end of the calving season. But unless they can find a market for bison they will have to stop breeding far short of what the ranch could support. Economic necessity demands they continue running cattle even though they can be degrading for the land.

For now, Pedro says they’ll continue experimenting with the best ways to manage their herds, with the hope of conserving bison and impacting sustainable land management far beyond this one ranch.

Related link:

El Uno Ranch on Facebook

[MUSIC: Mickey Raphael, “Home On The Range (Instrumental)” on Red River Valley, Cumberland Records]

Science in Danger at the US-Mexican Border

The border between the United States and Mexico is among the most heavily guarded in the world, causing complications for the nature that exists there, as well as the scientists that study that nature. (Photo: Courtesy of Sergio Avila)

BASCOMB: The border wall between the United States and Mexico is already impeding migratory animals, and if the wall is expanded, endangered animals like jaguar will have an even harder time finding a mate or territory. And the scientists who study borderland ecosystems are also having a hard time doing their work. Shortly after I returned from the border last summer, I sat down with Steve Curwood to tell him that nearly every scientist I spoke to had some story about how the wall and the crackdown on immigration is affecting their ability to do their work.

CURWOOD: Really, how?

BASCOMB: Well, there are a couple different ways. The first and most obvious is just your classic harassment and intimidation.

CURWOOD: Oh?

BASCOMB: Yeah, one of the most egregious stories I heard was from Sergio Avila, a wildlife biologist with Sierra Club. Sergio is originally from Mexico but he’s been a US citizen since 2016. He told me about a particularly unnerving experience he had a few years ago in the mountains near the border. He said he heard a truck coming down the mountain, out of sight and around a bend in the road. He assumed it was Border Patrol, so he just waited for it to arrive.

AVILA: And so, when they saw me, they accelerated really fast and got to me next to me really quick and they stopped to a screech really make a big cloud of dust and say: What are you doing here? Well, I'm a biologist, and I'm studying wildlife. So I had to show my ID, which is my driver's license, I had to show my passport, I had to show that my passport had a visa, I had to show papers that I had from the organization I was working with, to see that it matches my name with my project with the organization. Because for these guys, it's very hard to believe that there is somebody studying jaguars out there, right? Like that's the first step for them to say this is not true. Or they always say oh, they taste good, those are the ones that you make carne asada with, you know, like, they have to make comments like those. And then one of them still inside of the car just pulls this huge semi-automatic weapon in front of him, out the car window and just says that, aren't you scared of people with guns like this, but he's pointing at me showing me, right? And so my first thought was like, but you're doing it? But yes, I am. I'm in front of you. And I'm scared right now. Right? Like, what makes you think that I'm not scared now? The interactions came to a point really, when law enforcement started increasing that I just had to stop a lot of my fieldwork, it was safer for me to just not do it.

Sergio Avila is a wildlife biologist, as well as an outdoor activities coordinator with Sierra Club. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: And Steve, Sergio has also had run-ins with the Minute Men, those are non-government volunteers who patrol the border with guns looking for people crossing illegally. And because they are not working in any official capacity the Minute Men are in some ways even scarier for people like Sergio because there’s no accountability.

CURWOOD: Yeah, it kind of sounds like they are vigilantes. So, I gather altogether he just didn’t feel safe anymore doing field work.

BASCOMB: Right, exactly, and Sergio is a trained field biologist with decades of experience working on endangered species in the area. Who knows what he might have found in his work that we no longer have access to? Then you extrapolate that out to the many scientists doing work in this area and it’s really a tremendous loss to science.

CURWOOD: Yeah, right….

BASCOMB: And Sergio feels that he is especially targeted for harassment because he is Mexican-American.

AVILA: Because I have dark skin color, and black hair and an accent, I get helicopters flying over me. But if I was white none of those things would happen to me, so it's basically because of racial profiling.

BASCOMB: And Steve, that sentiment was backed up by another researcher that I met up with, Randy Serraglio of the Center for Biological Diversity.

SERRAGLIO: I'm a white man. So I benefit from white male privilege every day. And no, I have not been harassed by Border Patrol as much as you would think. Because really, they operate on racial profiling. So a lot of times I come up to the checkpoints, and I just get waved through. I'll just look like some white guy that lives in Arizona. I feel frightened sometimes on these dirt roads out here in the middle of nowhere, because every now and then you'll come across a Border Patrol vehicle driving like a maniac, you know, at high speeds. And it's very dangerous. The number one cause of death for Border Patrol agents is single person car accidents. You know, it's a it's one guy driving his vehicle too fast, and he rolls it and dies. So I certainly don't want one of them to run into me and it's come close couple times.

Ecosystems like the Sonoran desert are not confined to national borders, leading to complications when scientists need access to both sides of a border. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Randy told me he doesn’t really feel threatened by Border Patrol directly, but he does feel afraid of ordinary citizens who don’t like his line of work.

CURWOOD: That’s right, the Center for Biological Diversity is pretty vocal in is opposition to the wall, right?

BASCOMB: Yes, they are, and they also want to do things like limit cattle grazing on public lands where endangered animals live, that sort of thing. Here’s Randy.

SERRAGLIO: I've done all kinds of fieldwork, right along the border on both sides, northern Mexico, southern Arizona, you know, out in those places that our government wants you to fear and wants you to think are overrun with violent criminals and everything. And I have never felt threatened in those places. However, I do feel threatened in my office in downtown Tucson, because my organization has received death threats, you know, many times in the past because of the work that we do. And I fear that one of these days, somebody's going to walk into our office and shoot the place up. Seems to be the newest, you know, pastime in the US.

CURWOOD: So, intimidation can take a lot of forms for people working in the border areas. You mentioned earlier that there’s also another way scientists are being hampered in their work.

BASCOMB: Yeah there is! Just physically crossing the border has become difficult in the last few years. I spoke with the executive director of the Sky Island Alliance, Louise Misztal.

MISZTAL: There's longer wait times at border crossings. Mexican staff that work with Sky Island Alliance have had challenges and been, you know, harassed and delayed coming across the border. It's been very challenging and I think for some of my staff, it's kind of frightening.

BASCOMB: And I actually had a similar experience myself crossing the border. I was with a group of journalists and scientists and we were detained for an hour and a half and searched.

CURWOOD: Um, that doesn’t sound like much fun, what happened?

BASCOMB: It wasn’t. When asked if we had anything to declare, Gary Paul Nabhan, an agricultural professor and researcher, said yes, I have a couple of small plants I’m using for my research. Gary identified himself as a researcher and we were traveling in a truck that said University of Arizona on the side of it. Well, that led to us being pulled aside for further inspections.

I actually recorded the first part of our detainment. First you’ll hear the border agent and then Gary.

AGENT: It's very important that you tell me everything related to agriculture. Because if I do find something it’s up to a $1,000 fine. You have any fruits or vegetables?

NABHAN: No.

AGENT: Do you have any plants?

NABHAN: Yes.

BASCOMB: After some more back and forth about other items we might have in the truck we were told to get out and wait.

AGENT: If everybody can just get down, we're gonna do a quick exam of the vehicle.

[CAR BEEPS, SOUNDS OF GETTING OUT OF THE CAR]

BASCOMB: That quick exam of the vehicle involved going through our truck with a fine-toothed comb, I mean they took apart our suit cases, checked everyone’s pants pockets, went through our toiletry bags… everything. And, in the end, they found a walking stick, some lemons I picked in Tucson and forgot about, and a handful of seeds in Gary’s pocket that he also didn’t realize were there, and we were charged $300 for a fine.

CURWOOD: Oh man, what an ordeal.

BASCOMB: Yeah, and it’s becoming a common ordeal that botanists like Gary have to deal with every time they need to bring samples across the border for their work. You know, there’s actually a list of prohibited items that you can’t bring into the US and Gary asked for it while we were waiting but the border agents said they couldn’t give us the list because it’s constantly changing. So, if your work involves bringing samples back and forth what are you supposed to do?

CURWOOD: In other words, catch 22.

BASCOMB: Yup exactly, then add in the harassment and it’s getting really hard to be a scientist on the US-Mexico border.

Related links:

- Listen to Bobby’s story about wildlife at the US-Mexico Border here

- Listen to Bobby’s story about the Coronado National Forest here

[MUSIC: Vasen, “Pa Vag” on Rule of 3, by Olov Johansson, NorthSide Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The Sonoran Desert was once a patchwork of rivers, streams and wetlands and one rancher is working to bring that water back to her land. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Symon Wynberg, “Mariah’s Watermill” on Guitar Works, Narada Lotus]

Water Ranching in Mexico

Valer Clark next to a riparian forest, which serves as a bridge between the water and the land (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Today the lands of the Southwestern US and Northern Mexico are considered desert or semi-arid. But for a couple months each year the region is awash with water from the seasonal monsoons. The normally dry river beds fill with flood water and swell to create habitat for all manner of water birds and amphibians. The watery paradise is short lived though, and most of those streams dry up in a matter of weeks. But that wasn’t always the case. A network of streams, rivers and wetlands once crisscrossed the landscape. In fact, more than 150 years ago, around the time of the Civil War, people in the region struggled with malaria, a mosquito-born illness typically associated with tropical wet climates. In Mexico I found a ranch owner that’s working on ways to keep some of that water on the land longer.

[FOOTSTEPS AND VOICES IN ECHOEY HALL]

Dry grass vs. healthy green grass. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

My journey starts at the Gadsden Hotel in Douglas, Arizona. It’s a grand building with walls the color of gold and marble pillars holding up an ornately painted ceiling. A step in the gray marble staircase bears a chip legend says was left by the Mexican Revolutionary Pancho Villa when he rode his horse up these stairs. Today it’s a popular spot for weddings and it’s here that I met Valer Clark.

CLARK: Good morning, so, this is a piece of history.

BASCOMB: The opulence of the hotel hints at an earlier time of prosperity and wealth. Valer says the whole region, north and south of the border, was made rich more than 100 years ago by the same things.

CLARK: This was copper, cotton, and cattle. The three Cs, you know, all in the early 1900s.

BASCOMB: Those three Cs made a lot of money but heavily degraded the land. Before the arrival of settlers the region didn’t have much water but there were some dense grasslands. Forests grew alongside rivers that meandered across the open landscape. And wetlands popped up every 20 or 30 miles along those rivers. But when Valer first visited back in the 70s, decades of mining and agriculture left the arid soil dry and cracked, few trees remained and the river beds were deeply eroded.

Valer came from a wealthy family in New York City. She and her husband at the time were travelling in Mexico and fell in love with the austere land. The wildness of the open parched landscape drew them in.

CLARK: We just came across this ranch, by accident. And he said, Well, why don't we bid on it, and I bid so low, I didn't think we'd ever get it. So I was thinking in terms of this being a summer place or something like that.

A beaver dam. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: That whim of a purchase of a summer place eventually ballooned into her life’s work.

CLARK: When I got here and started seeing the lack of water and seeing the situation, what it looked like, and the hills were bare, and there was no grass. And I thought I wonder if you could make a change. I wonder if there's something you can do about this. And I started doing it. And I realized you can, and I guess I got hooked.

BASCOMB: Valer eventually bought and rehabilitated some 150,000 acres of land in northern Mexico and the Southwest US. That’s more than 10 times the size of Manhattan. And her work here has been transformative, says Ron Pulliam.

PULLIUM: There are four great geological forces: there's volcanism, plate tectonics, there's erosion. And there's Valer. And Valer is one of the forces that has created the landscape around us here.

Wetland greenery. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Ron is an ecologist, formerly with the US Department of Interior, and founder of the nonprofit Borderlands Restoration Network.

[CAR DOOR SOUNDS, DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I pile into a pickup truck with Ron. Valer, in her own truck, leads the way out of Douglas, Arizona and across the border to Agua Prieta, Mexico.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We leave behind the maquiladora factories in the duty-free trade zone of Agua Prieta and drive an hour southeast to Valer’s ranch. Pavement and two-story buildings give way to dusty soil and brittle pale green grass. To me, as a New Englander, the landscape looks rather inhospitable, but Ron says this is prime cattle grazing territory.

PULLIAM: Generally speaking now, the stocking ratios are on the order of one cow to one hundred or two hundred acres in this area. And then think of around the turn of the century, 100 times that number of cows.

BASCOMB: And all those cows led to disaster for this delicate landscape.

PULLIAM: And so if you put hundreds of cows out on a small area here you basically reduce all the ground cover. So, when the rain comes it just runs off the land rather than being caught up in the vegetation.

BASCOMB: And keeping that rainwater on the land is the fundamental key to what Valer is doing to rehabilitate her property. More water will mean more grass and trees, habitat for the wildlife that was once common here. It’s sort of a build it and they will come philosophy.

Abundant reeds in the wetlands. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[FOOTSTEPS ON GRAVEL]

BASCOMB: We arrive at Valer’s Cajon Bonito Ranch and she takes me on a walk around her property. She wears a cowboy hat over thick gray hair, jeans, and a white button-down shirt. She is tiny, so petite one might think her fragile, but she is shockingly strong and sets a fast pace over the rugged terrain.

In a similar way, Valer’s solution to rehabilitating the degraded land is equally small but powerful.

CLARK: This is what we call a gabion, which is a wire basket that is filled with rocks.

BASCOMB: That’s it, a wire basket full of rocks. They’re about 3 feet tall, some just 5 or 6 feet wide, others more than a hundred feet across. Valer and her crew have built more than 20,000 of them on her property. They all sit in riverbeds which are dry most of the year until the monsoon rains come. That’s when the gabions get to work. They slow down the water rushing through the river bed so silt can accumulate behind them, like a sponge.

CLARK: And that sponge holds the water. And so the water, instead of just whipping through fast, when it rains, 30% of it’s held back and goes into the ground. And so it filters down very slowly. And this is somewhere near the bottom. So you see pools of water.

[WATER SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Those pools of water are home to insects, birds, rare frogs, and endangered fish species.

CLARK: And trees, all these trees coming up, they’re a result of having water here.

BASCOMB: So how old are these trees? I mean, these are 30, 40 feet high. So how old are they?

CLARK: Not old at all, these grow very fast, these grow very fast, these trees. Some of them grow 10 feet a year.

During monsoon season, rivers in the area fill briefly and bring green before quickly drying back out. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Nearly all these trees have sprouted up since Valer began keeping more water on the land. Near the stream, a canopy of cottonwood trees towers over us and a lush green understory creates the feeling of a jungle that follows the narrow band of water. We continue our walk on the edge of the forest, which she says is a vital corridor for wildlife in the region.

CLARK: We’ve seen ocelot, we've seen bobcats and lions and bears and coatimundis and javelinas, ring tailed cats. . . .

BASCOMB: Have you seen a jaguar?

CLARK: We didn’t but a jaguar was photographed right coming….

BASCOMB: [screams] my goodness! What is that?

CARK: That is a gila monster!

BASCOMB: You’re kidding.

CLARK: They’re very rare, I mean they’re very very… yes.

BASCOMB: I almost stepped on it.

CALRK: Take a picture, take a picture! Quickly. That’s a find. You found, that was very exciting.

BASCOMB: After being startled by the venomous lizard Valer and I head back to her ranch house. We meet up with Ron Pullium to see some more of Valer’s work.

[DRIVING SOUND]

BASCOMB: We drive past parched bare earth cracked into the shape of a hexagon and stop at a different ecosystem all together.

[WETLANDS SOUNDS, RUNNING WATER, BIRDS]

BASCOMB: Instead of a riparian forest this is a wetland teeming with life. Reeds and cat tails poke up through the water. At least a dozen different species of brightly colored birds dart about, butterflies sun themselves, and bright blue dragon flies copulate in mid-air. Ron Pullium says this region is a hotbed for insect diversity, including some 450 different species of bees and….

Gabions are baskets of rocks that Valer Clark places in stream beds to slow the water as it rushes through. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PULLIUM: Very strangely, the desert area through here has exceptionally high dragon fly diversity. And that's one of the signs of the past extent of wetlands in this area.

BASCOMB: Indeed, historical records from the Spanish settlers suggest this region was once a patchwork of wetlands just like this. Gary Paul Nabhan is a desert ecologist with the University of Arizona. He says the word Sonora, as in, the desert here, actually means spring-fed wetland in a native language.

NABHAN: In an area the size of Connecticut, you might have 20, maybe 30 of these, but they were so important to human life and to wildlife that every one of them was named. And probably one in 10 is left, probably more like one in 20 or one in 30.

BASCOMB: How important are these types of habitat for the whole region, for the ecosystems?

NABHAN: Well, incredibly so, -- and look at the Vermilion flycatcher, I'm sorry, they’re showstoppers. They are just so beautiful.

BASCOMB: Oh, they're bright red, and they're beautiful. Yeah, yeah.

NABHAN: First of all, in a historical ecological sense. These were the seed beds for all the, the vegetation. But secondly, they were the hubs of human habitation because this is where all the ecosystem services happen. And so they were as important as the oases were in the Sahara Desert, you would travel 30 miles out of your way to reach a place like this.

BASCOMB: And important for migrating wildlife too. These were wet stepping stones between central Mexico and Canada.

[WETLAND SOUND]

BASCOMB: Bright and early the next morning I meet up with Ron Pullium to go birding near another wildlife corridor, which it turns out was a highway of a different sort not so long ago.

BASCOMB: Morning!

PULLIUM: We’re up for a late morning walk.

BASCOMB: Late morning? It’s 5:30.

PULLIUM: [LAUGHS]

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We walk alongside a small creek, craning our necks up, hoping to spot some birds.

PULLIUM: This creek is interesting just in itself it was protected by Valer because it was identified as the most intact fish stream in northern Mexico, and perhaps the most intact in all of Mexico. And it had several species, five or six species, of rare and endangered species. And this also used to be the bus route. And it looks like a pristine natural stream now. But in the 1950s there was a biologist that camped on the shore right over here. And he, in the night, he counted five buses driving up the stream. This was the road between Sonora and Chihuahua.

Valer Clark perches on a gabion. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Somehow those endangered fish species managed to survive living in a bus route and are now on the rebound. Even beavers have re-colonized the river. At one-point Valer Clark introduced a few beaver pairs to one stream on this river. But now several more have been drawn to the water that is once again running free and the broad tailed volunteers are getting to the business of building dams for her.

For all her ecological work, Valer is still mindful of serving as a model for other ranches in the region that depend on raising cattle for their livelihood. She removed most of the cows from her ranch when she bought the place. But she did keep a small herd and is very deliberate about where and when they graze. And it’s paid off. Her ranch manager recruited members of his family to enter three novio steers in a large cattle exposition.

Bobby narrowly avoided stepping on this gila monster while out with Valer (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CLARK: All the people in Sonora bring their animals to this big thing, this big do. And so his daughter, Sarah, won first prize among novios. And she won the grand champion, the overall prize. And then when the animal was slaughtered, we won overall, the prize of having the best cut up meat too. So we couldn't, we couldn't get any better than that.

BASCOMB: The hope is that public win will encourage other ranchers in the area to explore the sustainable ranching that results in award-winning beef. And Valer’s biggest hope is that they will see the advantage of rehabilitating their own degraded land.

CLARK: I think the next thing is having people come and see the benefits of what we've done, that it is possible to turn land around, I think it's important, the next step would really be to reach out to other people, and let them know that it's possible to heal really sick land.

BASCOMB: In fact, Valer’s work is already spreading across the region, literally. The water she retains with her gabions does not stay on her land alone. It seeps into the water table and flows downstream, hydrating degraded lands for miles around. And in a region where water is wealth, Valer is already sharing in the profits of restoration.

Related link:

The Cuenco Los Ojos foundation, which supports preservation and biodiversity in Mexico and the United States

BirdNote®: Lily-Trotters, Jesus Birds

An African jacana appears to walk on water with the aid of lily pads and its long toes. (Photo: zsispeo, CC)

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BASCOMB: Here’s this week’s BirdNote with Michael Stein.

BirdNote®

Jacana - Lily-trotter

[Northern Jacana calls, LNS # 140224]

STEIN: The Northern Jacana (for information about pronunciation, please see below*), found in Mexico, Central and South America, and Cuba. And the bird with the longest toes -- relative to its body size -- of any bird. Those toes are l-o-n-g, and they're made for walkin'. Living in wetlands, Jacanas are nicknamed "lily-trotters," for their ability to walk on lilypads. In Jamaica, they're known as "Jesus birds," because it looks as if they're walking on water. Feats possible only because of those toes. [LNS #140224 2:40 and 3:14]

But that's not all that's cool about the jacana. The males carry their young under their wings. Now, you've seen a mother housecat -- kitten dangling from her mouth -- carrying kittens one by one to safety. Well, the male jacana will carry his young, too – except that he can carry several at once. [Northern Jacana LNS # 140224]

An immature wattled jacana stretches its wings (Photo: © Dory Hamlyn)

So picture this wildly colorful wading bird, crouching down and spreading his wings. The young move in under him, and he sweeps them up and carries them off, tiny legs dangling from under his wings. It doesn't look very comfortable for the young ones, but it sure is safe. [Northern Jacana LNS # 140224]

I’m Michael Stein.

[Northern Jacana LNS # 140224]

###

Written by Ellen Blackstone

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Jacana recorded by Gerrit Vyn

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org February 2018 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# jacana-01-2015-02-09 jacana-01

* "Jacana" seems to be pronounced in many different ways. Julie Zickefoose in her blog says the pronunciation of "jacana" in the Tupi Indian language is zhuh-sah-NAH, with the emphasis on the last syllable. However, the Cornell recordist of the Northern Jacana heard in this show, Gerrit Vyn, says juh-CAH-nuh, so in this case, we went with that. (Listen here: http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/140224) For a pronunciation in Brazilian Portuguese, check out Forvo.com: http://www.forvo.com/word/ja%C3%A7an%C3%A3/#pt

https://www.birdnote.org/show/jacana-lily-trotter

Related links:

- Watch a Jacana carrying its young

- This story on the BirdNote website

[MUSIC: Gary Burton, “Walkin’ In Music” on Next Generation, by Julian Lage, Concord Records]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org. Steve Curwood will be back next week. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth