January 17, 2020

Air Date: January 17, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Democratic Debaters United on Need For Climate Action

View the page for this story

At the final Democratic primary debate before the 2020 Iowa caucuses, the six top polling candidates onstage all discussed their concerns about climate impacts and their plans for addressing the problem and broadly agreed on the need to address climate disruption. CNN and the Des Moines Register hosted the debate in Des Moines, Iowa, and Host Steve Curwood highlights the main climate change moments from the evening. (09:56)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, even as Australia is plagued by wildfires, torrential rains have caused flooding that have left dozens dead in Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta. Host Bobby Bascomb and Peter Dykstra also examine the threats to underwater ecosystems posed by deep sea mining of everything from diamonds to metals. And in the history calendar, fifty years ago this week, President Richard Nixon protected the integrity of the Florida Everglades by blocking a proposal to build a jetport in the park. (04:04)

Senator Lisa Murkowski Talks Up Public Lands

View the page for this story

Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) is known for reaching across the aisle to broker bipartisan deals, including the bipartisan 2019 Dingell Act to protect and expand public lands. Host Steve Curwood and Senator Murkowski discuss the Dingell Act and her plans for her final year as Chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. They also cover her views on the Trump Administration’s plans to exempt the Tongass National Forest from the roadless rule, and the need to balance oil drilling and climate concerns in the state nicknamed “The Last Frontier”. (11:06)

Trump Moves to Weaken NEPA

View the page for this story

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), forms the bedrock of environmental protection at the federal level. It was signed into law 50 years ago by President Richard Nixon and requires environmental review before federal agencies begin substantial new infrastructure projects that could cause or increase environmental harm. Now the Trump Administration says it wants to streamline procedures under NEPA to make it easier for large federal projects to move forward, but critics say it will gut certain environmental protections. Michael Gerrard, an environmental law professor at Columbia Law School, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss. (07:14)

Note on Emerging Science: Plastic-Eating Mushrooms

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Around 300 million tons of plastic is produced annually, and only a tiny fraction of that plastic is recycled. Since most plastic will take about 400 years to decompose, plastic pollution poses a huge threat to the environment. But, as Living on Earth's Don Lyman explains, the discovery of a mushroom species that feeds on polyurethane might change all that. (01:45)

After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales

View the page for this story

Communities in Appalachia have been hit hard economically as coal production has dropped, leaving miners out of work, and their communities with shrunken tax bases and fewer paying customers for local businesses. It’s a story that has also played out in Wales in the UK. The experiences on both sides of the Atlantic are the theme of Tom Hansell’s new book, “After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales”, also a documentary. The book and film tell the story of the After Coal Project, an initiative that seeks to bridge former Appalachian and Welsh coal mining communities. Tom Hansell joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how the After Coal Project is helping breathe new economic and cultural life into these regions. (12:41)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Gerrard, Tom Hansell, Lisa Murkowski

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Alaska Republican Lisa Murkowski on her tenure as chair of a powerful Senate committee and her bipartisan success with a landmark public lands bill.

MURKOWSKI: Our public lands, our waters, how we care for these lands, these are issues that can bring us together, rather than divide us, particularly at partisan and divisive times.

CURWOOD: Also, highlights from the Democratic presidential debate.

SANDERS: Given the fact that climate change is right now the greatest threat facing this planet, I will not vote for a trade agreement that does not incorporate very, very strong principles to significantly lower fossil fuel emissions in the world.

CURWOOD: We’ll hear from all of the candidates on the debate stage and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Democratic Debaters United on Need For Climate Action

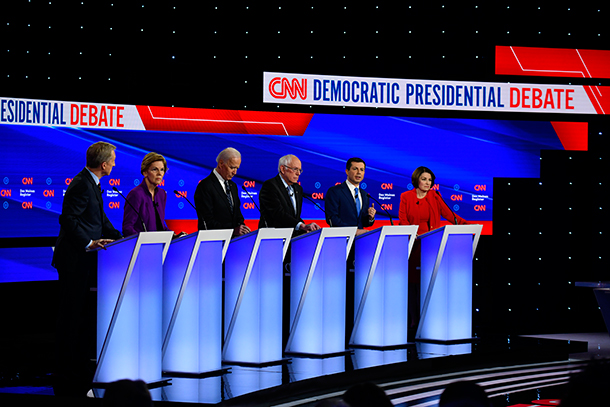

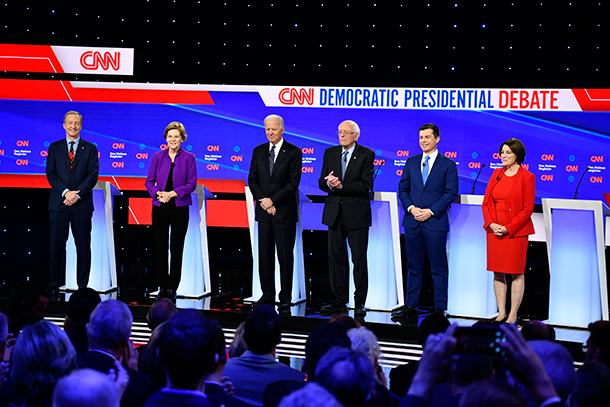

The six Democratic presidential candidates at Drake University in Iowa for the debate before the Iowa caucuses. From left to right: Tom Steyer, Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Pete Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar. (Photo: CNN)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The cable news network CNN and the Des Moines Register hosted a debate in Iowa on January 14th among the six top polling Democratic candidates for President, just nineteen days before the Iowa caucuses. One of the debate moderators was Brianne Pfannenstiel, she is the chief politics reporter for the Des Moines Register.

PFANNENSTIEL: Let's turn now to the climate crisis. Here in Iowa parts of the state remain under water after record-breaking flooding began last spring, racking up an estimated $2 billion in damages. Today many Iowans are still displaced from their homes. Mayor Buttigieg, you have talked about helping people move from areas at high risk of flooding. But what do you do about farms and factories that simply can't be moved?

BUTTIGIEG: That's why we have to fight climate change with such urgency. Climate change has come to America from coast to coast. Seeing it in Iowa. We have seen it in historic floods in my community. I had to activate our emergency operation center for a once-in-a-millennium flood. Then two years later had to do the same thing. In Australia there are literally tornadoes made of fire taking place. This is no longer theoretical and this is no longer off in the future. We have got to act, yes, to adapt, to make sure communities are more resilient, to make sure our economy is ready for the consequences that are going to happen one way or the other. But we also have to ensure that we don't allow this to get any worse. And if we get right, farmers will be a huge part of the solution. We need to reach out to the very people who have sometimes been made to feel that accepting climate science would be a defeat for them, whether we're talking about farmers or industrial workers in my community, and make clear that we need to enlist them...

Both Senator Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and former South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg plan to use market incentives to fight climate change. (Photo: CNN)

PFANNENSTIEL: But, Mayor Buttigieg...

BUTTIGIEG: ... in the national project to do something about it.

PFANNENSTIEL: ... to clarify, what do you do about farms and factories that cannot be relocated?

BUTTIGIEG: We are going to have to use federal funds to make sure that we are supporting those whose lives will inevitably be impacted further by the increased severity and the increased frequency. And by the way, that is happening to farms, that is happening to factories, and that disproportionately happens to black and brown Americans, which is why equity and environmental justice have to be at the core of our climate plan going forward.

PFANNENSTIEL: Thank you, Mayor Buttigieg.

CURWOOD: Next up, was Tom Steyer.

Tom Steyer says he will declare climate change as a national emergency and invest in infrastructure resilient to natural disasters. (Photo: CNN)

STEYER: Look, what you're talking about is what's called managed retreat. It's basically saying we're going to have to move things because this crisis is out of control. And it's unbelievably expensive. And of course we'll come to the rescue of Americans who are in trouble. But this is why climate is my number one priority. And I'm still shocked that I'm the only person on this stage who will say this. I would declare a state of emergency on day one on climate. I would do it from the standpoint of environmental justice and make sure we go to the black and brown communities where you can't breathe the air or drink the water that comes out of the tap safely. But I also know this, we're going to create millions of good-paying union jobs across this country. It's going to be the biggest job program in American history. So I know we have to do it. I know we can do it. And I know that we can do it in a way that makes us healthier, that makes us better paid, and is more just. But the truth of the matter is, we're going to have to do it and we're going to have to make the whole world come along with us. And it's going to have to be...

PFANNENSTIEL: Mr. Steyer...

STEYER: ... priority one.

PFANNENSTIEL: Mr. Steyer, to clarify, you say you're the climate change candidate, but you made your $1.6 billion in part by investing in coal, oil, and gas. So are you the right messenger on this topic?

The six Democratic Presidential candidates agree on recommitting to the Paris Climate agreement if elected in 2020. From left to right: Tom Steyer, Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Pete Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar. (Photo: CNN)

STEYER: I absolutely am. Look, we invested in every part of the economy. And over 10 years ago I realized that there was something going on that had to do with fossil fuels, that we had to change. So I divested from fossil fuels. I took the Giving Pledge to give most of my money away while I'm alive. And for 12 years I have been fighting the climate crisis. I have beat oil companies in terms of clean air laws. I have stopped fossil fuel plants in Oxnard, California. I fought the Keystone pipeline. I have a history of over a decade of leading the climate fight successfully.

PFANNENSTIEL: Thank you, Mr. Steyer.

STEYER: So actually, yes, I am the person here who has the chops and the history that says, I'll make it priority one, because I have been doing it for a long time.

CURWOOD: The Trump Administration has moved to roll back a number of environmental rules including NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act, and you can find details of that on the Living on Earth website. Senator Warren was next in the debate and she was asked about the rollback.

Senator Elizabeth Warren plans to invest $3 trillion to expand renewable energy. (Photo: CNN)

WARREN: Climate change threatens every living thing on this planet. And the urgency of the moment cannot be overstated. I will do everything a president can do all by herself on the first day. I will roll back the environmental changes that Donald Trump is putting in place. I will stop all new drilling and mining on federal lands, and offshore drilling. That will help us get in the right directions. I'll bring in the farmers. Farmers can be part of the climate solution. We should see this though for the problem it is. Mr. Steyer talks about it being problem number one. Understand this, we have known about this climate crisis for decades. Back in the 1990s we were calling it global warming, but we knew what it was. Democrats and Republicans back then were working together because no one wanted a problem. But you know what happened? The industry came in and said, we can make big money if we keep them divided and make no change. Priority number one has to be taking back our government from the corruption. That is the only way we will make progress on climate, on gun safety, on health care, on all of the issues that matter to us.

PFANNENSTIEL: Thank you, Sen. Warren.

Sen. Klobuchar, some of your competitors on this stage have called for an all-out ban on fracking. You haven't. Why not?

CNN’s Abby Phillip (left) and Wolf Blitzer (center), and the Des Moines Register's Brianne Pfannenstiel. (Photo: CNN)

KLOBUCHAR: Well, first of all, I would note that I have 100 percent rating from the League of Conservation Voters. And that is because I have stood tall on every issue that we have talked about up here when it comes to this administration, this Trump administration, trying to reverse environmental protections. I think it is going to lead to so many problems. And one thing that hasn't been raised, by the way, is the rules on methane, which is actually one of the most environmentally dangerous hazards that they have recently embarked on. And I would bring those rules back as well as a number of other ones. When it comes to the issue of fracking, I actually see natural gas as a transition fuel. It's a transition fuel to where we get to carbon neutral. Nearly every one of us has a plan that is very similar. And that is to get to carbon neutral by 2045 to 2050, to get to by 2030 to a 45 percent reduction. And I want to add one thing that no one's really answered. When we do this, we have to make sure that we make people whole.

CURWOOD: Senator Sanders was next.

SANDERS: Let's be clear. If we as a nation do not transform our energy system away from fossil fuel, not by 2050, not by 2040, but unless we lead the world right now — not easy stuff— the planet we are leaving our kids will be uninhabitable and unhealthy. We are seeing Australia burning. We saw California burning. The drought here in Iowa is going to make it harder for farmers to produce the food that we need. This is of course a national crisis. I introduced legislation to indicate it's a national crisis. We have got to take on the fossil fuel industry and all of their lies and tell them that their short-term profits are not more important than the future of this planet. That's what the Green New Deal does. That's what my legislation does. And that is what we have to do.

Senator Bernie Sanders spoke about climate change as an economic and social justice issue and was the first presidential candidate to back the Green New Deal. (Photo: CNN)

PFANNENSTIEL: Vice President Biden, your response?

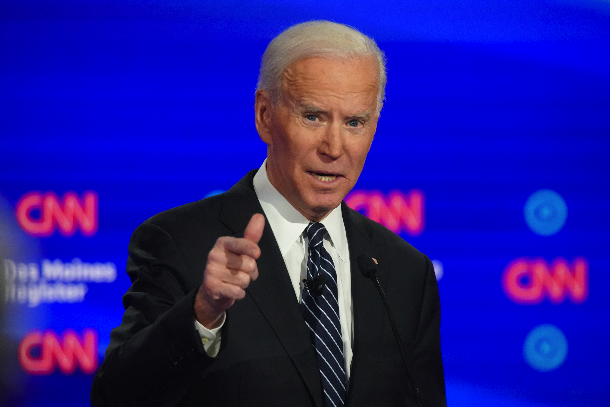

BIDEN: My response is, back in 1986, I introduced the first climate change bill — and check PolitiFacts; they said it was a game-changer. I've been fighting this for a long time. I headed up the Recovery Act, which put more money into moving away from fossil fuels to — to solar and wind energy than ever has occurred in the history of America. Look, what we have to do is we have to act right away. And the way we act right away is, immediately if I'm elected president, I'll reinstate all the mileage standards that existed in our administration which were taken down. That's 12 billion gallons of gasoline — barrels of gasoline to be saved immediately. And with regard to those folks who in fact are going to be victimized by what's already happened, we should be investing in infrastructure that raises roads, makes sure that we're in a position where we have — that every new highway built is a green highway, having 550,000 charging stations. We can create — and this is where I agree with Tom — we can create millions of good-paying jobs. We're the only country in the world that's ever taken great crisis and turned it into great opportunity. And one of the ways to do it is with farmers here in Iowa, by making them the first group in the world to get to net zero emissions by paying them for planting and absorbing carbon in their fields right — there's more to say, but I know my time is...

Former Vice President Joe Biden plans to include emission reduction in foreign policy agreements. (Photo: CNN)

CURWOOD: Mr. Biden cut himself off as his time ran out and the moderators moved on to another topic. In sum, all six of the top polling democratic presidential candidates pretty much agreed on the need to address climate disruption. The Iowa caucus is scheduled for February 3rd. The next Democratic presidential debates are February 7th and February 19th, just before the New Hampshire primary and the Nevada caucus respectively. Those excerpts from the Democratic presidential debate in Des Moines, Iowa on January 14th came to us courtesy of CNN. And there is more on the race for the White House on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related link:

Click here to watch the entire Democratic debate

[MUSIC: Ray Charles, “Ain’t Misbehavin’”, on Ray Charles: The Genius After Hours, by Fats Waller, Andy Brooks, & Andy Rozof, Mills & Joy, Atlantic Masters]

Beyond the Headlines

Jakarta is home to 10 million people and is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. (Photo: Iqbalnuril, Pixabay)

BASCOMB: It's time for a look now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org, and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby, we're going to start off on a less than happy note. We've all heard about the disastrous fires in Australia and the pretty clear links to climate change. But a few thousand miles away from Australia is a climate driven phenomenon that may be just as bad and it's a of a very different nature.

BASCOMB: What are we thinking of here?

DYKSTRA: Torrential rains in Indonesia. Some areas received over a foot of rain. In the capital, Jakarta, floodwaters have absolutely submerged this metro area of well over 10 million people. And of course, Jakarta has been a focus for climate change for a couple reasons. The seas are rising at the same time that the land that the city is built on is subsided.

BASCOMB: Right. I know they're talking about actually moving the capital from Jakarta to the island of Borneo, which would bring with it a whole lot of other challenges. I mean, it's a very ecologically diverse island, Borneo, but it seems like the people are really in a tough spot there.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, throughout Indonesia they're in a tough spot. Deforestation is another serious challenge and a serious problem that's building in its impact.

BASCOMB: Well, what else you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: There's an era of deep-sea mining on the horizon. It promises fabulous wealth. It promises some legitimate scientific advances, like we don't know what kind of biologics and potential medicines we find there. But it also promises a level of destruction of the sea floor that's the ocean-based equivalent of how we're destroying the Amazon today.

The deep sea contains a variety of valuable metals and gemstones, including diamonds. (Photo: Skeeze, Pixabay)

BASCOMB: Oh, man, well, what could that potentially mean in terms of the ecology there if we start drilling and mining?

DYKSTRA: Well, here are a few things that are already underway. There are big mining companies like Rio Tinto, diamond companies like DeBeers that are already scraping the ocean floor to get literally diamonds. DeBeers has found a sizable, marketable quantity of diamonds on the ocean floor. Other companies like Rio Tinto are looking for other valuable metals, strategic metals. And the agreement, the global agreement that would help prevent environmental abuse has never fully taken effect. That's the Law of the Sea Treaty. One country that has never opted into the treaty, ratified and signed it is the United States.

BASCOMB: Well, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: A 50th anniversary of that old tree hugger is at it again. President Richard Nixon on January 16, 1970, formally killed a proposal that would have built a massive jetport in the middle of the Florida Everglades.

The proposed jetport in the Everglades would have interfered with waterflow into the park and compromised water quality. (Photo: Sjones68, Pixabay)

BASCOMB: A jetport in the Everglades that seems like an inherently bad idea. I mean, it's a very unstable area, you know, to be building on.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, what could possibly go wrong? 36 miles from downtown Miami, it would also serve Fort Myers and Naples in the west coast of Florida peninsula. It's a project that had great commercial potential but it's a project that also would be a major step toward the ruin of the unique quality of the Everglades.

BASCOMB: And how far along did they get with it?

DYKSTRA: There is actually a runway that's built. It's in the middle of the Everglades. If you go onto Google Earth, and head west from Miami about 36 miles, you can see a completed runway in the middle of an otherwise pristine swamp, a swamp that thanks to Richard Nixon, we didn't drain.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- More on Indonesia’s climate disaster

- Deep sea mining is generally unregulated

- President Nixon sought to balance the need for a jetport with the need to protect the Everglades

[MUSIC: Television's Greatest Hits Band, “Theme From ’77 Sunset Strip’” on "Television's Greatest Hits: Vol. 1”, by Jerry Livingston and Mack David, TeeVee Toons]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The granddaddy of environmental laws comes under fire from the Trump administration. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ray Charles, “Ain’t Misbehavin’”, on Ray Charles: The Genius After Hours, by Fats Waller, Andy Brooks, & Andy Rozof, Mills & Joy, Atlantic Masters]

Senator Lisa Murkowski Talks Up Public Lands

President Donald Trump signs the John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management and Recreation Act on March 12, 2019, in the Oval Office of the White House. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, the bill’s sponsor, stands at far left. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

As the US Senate prepared for the historic impeachment trial of President Donald Trump, the first person to reach across the aisle from the Republican side to the Democratic minority on the question of witnesses was Alaska’s senior Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski. And few were surprised as Senator Murkowski is known for brokering bipartisan deals, including pulling together more than 100 separate bills to enact the 2019 Dingell Act to protect and expand public lands. The law creates new national monuments, parks and wilderness areas and fixes some local concerns, such as land allocation rights for Alaska’s Native American Vietnam veterans. Because of Republican term limits Lisa Murkowski is in her last year as Chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. And this year won’t be without controversy as the Trump administration seeks to exempt the largest remaining temperate rainforest in the world, the Tongass National Forest in Alaska, from roadless protections. Senator Murkowski joins us now from the Capitol. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MURKOWSKI: Good to be back with you, Steve, thank you for the invitation.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. Time flies. So, your last five years as Chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, had a number of events including this 2019 Public Lands Act, I guess it's called the Dingell Act. What are you most proud about that?

MURKOWSKI: Well, I'll tell you. I think the thing that makes me most proud of that package was that it was probably the most substantive land/water conservation bill that has been signed into law in at least a decade. But the fact that we advanced 120 bills together in a package, and received overwhelming bipartisan support, at a time when -- we were in the midst of a government shutdown last year, when, when we began moving this through, when theoretically, Republicans aren't talking to Democrats and the administration was not being cooperative. What we were able to do was pretty impressive. And we not only moved it out of the Senate overwhelmingly, 85 to 12, it then moved over to the House. And the House had switched hands, from Republican leadership at the time that this package was created, to now in control of the Democrats. And the package that we had worked on had been done so cooperatively through the process. And so when the House took up the Senate-passed bill, and didn't make any changes, adopted it 366 affirmative votes, and then to have the president then stand behind it and applaud the work that went to it. That was as important to me as anything. And it was a reminder to me that care about our public lands, our waters, how we care for these lands -- these are issues that can bring us together, rather than divide us, particularly at partisan and divisive times. So I think in retrospect, that's probably the thing that I was most proud of.

Alaska’s Tongass National Forest is home to the largest remaining temperate rainforest in the world. (Photo: Ian, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: A while back, I was visiting Prince of Wales Island, speaking to some Native American Vietnam vets, who were very concerned that when they came back, they never got the land allotments. What did you do in this act that made them whole?

MURKOWSKI: What we were able to do, and in fairness, the final solution is not one that makes everybody happy, because in an effort to make sure that those who had been denied that opportunity to file for their allotments because again, they were serving their country. We basically were able to reopen so that they could make application for their allotments. But what we weren't able to do was to open it to areas that they had perhaps had close connections to the land prior to their service, because these lands were now either in the Tongass, or they were in parkland, or wilderness area. It was important for a compromise to recognize that there were going to be some lands that were off limits. But we have allowed now for equity for those who were denied the opportunity while they were serving their country.

CURWOOD: Let's talk more about the Tongass National Forest. The Tongass is, what, 40% of our whole National Forest assets. And I understand there are plans to exempt the Tongass now from the roadless rule, that of course limits logging there, and you welcome this decision. Why is the Tongass different in this regard than other forests where the roadless rule does apply?

MURKOWSKI: Well, I think it's important to put the Tongass into context. You note the size; the Tongass is the largest national forest in the country, at 16.7 million acres, it's larger than West Virginia. It's about 80% of the land base there in Southeast Alaska. And there's 32 islanded communities within Southeast; I happen to have been born in one of them, in Ketchikan; lived in Wrangell, and in Juneau. And these are communities that are surrounded by a National Forest. One reality to the Tongass, and those who live there know this very well: it is overwhelmingly road-free, unlogged, rich in wildlife. And what I think is important to stress is it will remain so, even if exempted from the roadless rule. The debate that is going on now and what is happening as they're moving through the draft environmental impact statements is that we have been dealing with a roadless rule that, in my view, has been kind of a one-size-fits-all approach, an additional layer of regulation that I have maintained, the other members of the delegation have maintained, the governor has maintained, previous governors have maintained, just should never have been applied to the State of Alaska. And we're not talking about an opportunity to clearcut the Tongass. What we're talking about is access for some of the smaller operators to be able to, to have a somewhat reliable, albeit small, supply of timber. But it's more than access to just timber. It's access to be able to build a road to allow for renewable energy operations; to be able to allow access to individuals for whether it is recreation or harvesting firewood. And so when we talk about access, I think it's important to recognize that relieving the Tongass from the roadless rule is not going to open it up to unlimited, unrestricted timber harvest. There are so many other protections at the state and at the federal levels to ensure that the Tongass is as we know it, a rich and truly beautiful area, and an area that can sustain the local communities with the small economies that they have.

CURWOOD: Alaska is beautiful, and also it's energy. How do you balance the effect of carbon based energy, where you see communities like Shishmaref dealing with climate change, and your economy in Alaska where there's plenty of hydrocarbons, and much of the economy is based on extracting those? How do you balance that going forward on the public lands? How do you balance the risks of climate disruption against the question of using oil and gas?

Earth’s poles are warming much faster than the globe as an average, and Alaska is already experiencing climate impacts from thawing permafrost. (Photo: NPS Climate Change Response, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MURKOWSKI: Well, it's something that in Alaska, we have always been challenged to try to achieve balance. When it comes to climate change, we know, in Alaska, we're on the front lines, there's no question that our climate is changing - we are seeing it. And so my big push to us in the state, and really, to us in this country is, we have resources that come from our ground. We have an obligation and a responsibility to be good environmental stewards. So as we access these resources to our benefit, what are we doing to make sure that we are limiting our impact, whether it is levels of emissions or whether it is just waste. So utilizing the technology, utilizing a level of research and development, whether it's pushing out on carbon capture and utilization, storage, efficiency, advanced renewables, what we are doing every day to develop new and cleaner technologies that will help us reduce our carbon output is something that I think we need to be focused on every day. This is what we need to do in Alaska, this is what we need to do around the country. On the Energy Committee, we spent a fair amount of time this past year focusing on what we're seeing with climate change. We've had hearings on energy innovation, we had another one on the electricity sector in a changing climate; good, good discussions about solutions that can help us diversify our energy portfolio, to integrate more renewables into the grid, more R&D, greater investments in clean energy. So, making sure that the national conversation gets us to a better place, a healthier place, we need to be able to talk about it so that we can get to solutions.

CURWOOD: And because of Senate Chair limits, of course, this is your last year now as Chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. What would you like to accomplish during this last year?

Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) chairs the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (Photo: Committee on Energy and Natural Resources)

MURKOWSKI: Well, I have an energy bill that I've been working on now for several years. We haven't seen substantive energy reform since 2007. So I am working with my partner on the committee, Senator Manchin from West Virginia, our staffs are going through over 50 different bills that we have worked on over the past year to put together an energy package that the Senate, the House and hopefully the President can all sign off on. But when you think about where we were in 2007, iPads had not even been invented then. We haven't reformed our energy laws since then. We've got some updating that needs to happen. We're going to be ready to go here very shortly with this. And that, to me would be significant, it would be enduring, and in my view, long past due. So that's going to be my big push early this year, is to get our energy laws updated -- everything from what we're doing with renewables, to cyber security, to efficiency, to nuclear. So we've got a lot on our plate, lot of work, and we're going to be moving.

CURWOOD: Lisa Murkowski is the senior Senator from Alaska and Chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Senator, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MURKOWSKI: Thank you for the opportunity to be back with you. Look forward to it again.

Related links:

- Listen to our interview with Senator Murkowski on the passage of the 2019 Dingell Act

- Listen to our interview with public lands bill cosponsor Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA)

- Read the full Senate Bill, the “John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act”

- Alaska Public Media | “Thousands of Alaska Native veterans now eligible for land allotments, but hurdles remain”

- NYTimes | “Forest Service Backs an End to Limits on Roads in Alaska’s Tongass Forest”

- The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources

[MUSIC: Diana Krall, “Almost Blue” on The Girl In the Other Room, by Elvis Costello, The Verve Music Group]

Trump Moves to Weaken NEPA

The Trans-Alaska pipeline, with its 12 pumping stations and hundreds of miles of feeder pipelines, is an example of the kind of infrastructure project which requires NEPA review. (Photo by Arthur T. LaBar, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: President Trump has moved to roll back rules under the granddaddy of environmental protection laws, the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. NEPA was signed into law 50 years ago by President Richard Nixon and mandates that federal agencies conduct formal studies before they begin any new infrastructure projects that could cause harm to the environment. NEPA reviews often uncover human health risks, endangered species or sensitive habitat in areas slated for development and in certain cases can compel the government to consider reasonable alternatives. Now the Trump Administration says it wants to streamline procedures under NEPA to make it easier for large federal projects to move forward, but critics say it will gut certain environmental protections. For more, I’m joined by Michael Gerrard, an environmental law professor at Columbia Law School. Michael Gerrard, welcome to Living on Earth!

GERRARD: Thank you glad to be here.

BASCOMB: The Trump administration has rolled back dozens of environmental laws and regulations in the last three years. Why is this proposed change significant, in the grand scheme of things, compared to those?

GERRARD: NEPA is such a bedrock law that underlies our implementation of most of the other laws and it's really putting a dagger to the heart of the structure of US Environmental Law to cut back on what it covers.

BASCOMB: Well, can you give me an example please of the NEPA rules in action? I'm thinking of the controversial Keystone XL pipeline and its many delays.

GERRARD: That's right. The environmental review of the Keystone XL pipeline was one of the major reasons for its delay. NEPA has also delayed or required rethinking of a very broad range of federal actions, whether it's allowing pipelines or military bases, or plans for extraction of oil and gas and coal from federal lands. It really is a pervasive law.

BASCOMB: And so what is the Trump administration proposing with these new NEPA rules?

GERRARD: The Trump administration is making hundreds of changes. The most important single change is probably that they would say they no longer need to look at the cumulative impacts of projects. You look at the impacts that a particular project has. But it would be in isolation from all of the other things that also affect that. And so if you have an area that has a lot of air pollution already, traditionally, there would be an examination of how this project would add to the pre existing levels of air pollution. The proposed rules would limit it to just what effect with this isolated project have.

BASCOMB: And I understand that the new rules would not require regulators to consider climate change when approving new projects. How significant are the NEPA roles in our fight against climate change?

GERRARD: So the rules don't explicitly say don't look at climate change, but by eliminating the need for cumulative impact assessment, they would have that effect to a large extent. The federal government undertakes many actions that have an impact on climate change. NEPA is the principal way by which we systematically think about the impacts of climate change. And if you have an administration that wants to fight climate change, it informs decisions on maybe what we should and should not be doing. During the Obama administration, they issued guidance calling for that kind of analysis. And that has become an important part of NEPA, both of looking at the impacts that projects may have on climate change through their greenhouse gas emissions, and the impacts that climate change may have on projects such as through sea level rise that could cause project areas to be underwater in the years to come.

When Navajo Bridge in Northern Arizona needed to be replaced in the mid 1990s, environmental impact assessments suggested the new bridge be located right next to the old bridge, in order to minimize disturbance to the local ecosystem. (Photo by Al_HikesAZ, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And to what degree do you see this as an environmental justice issue? I mean, a lot of polluting industries are already cited in lower income and minority communities. Might we see an uptick in that trend if these changes are implemented?

GERRARD: One important effective of eliminating the consideration of cumulative impacts is that the communities that are most affected by cumulative impacts are often low income and minority communities. If you are putting a polluting facility in a low income and minority community, you would want to know from an environmental justice perspective, what is already there? What is the pollution that is already happening in that community? This new proposed regulation would say, no, you don't have to look at that you just look at this particular project. And so, this proposed change would make it easier to cite polluting facilities in environmental justice communities.

BASCOMB: Now, what if state and local agencies want to employ stricter standards than the federal laws would require?

GERRARD: This does not affect what states and cities can do. Many states and a few cities have their own laws on environmental impact assessment. And they are free to continue to do that, despite what happens at the federal level.

BASCOMB: And there's also a component here to speed up the amount of time that agencies can spend on environmental impact statements, can you tell me about that, please?

US Army Corps of Engineers, Fort Irwin water treatment plant. (Photo: US Army Corps of Engineers, Los Angeles District, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

GERRARD: There have long been complaints that the NEPA process takes years and years and that it slows down construction projects of all kinds. So this proposed regulation tries to speed that up. There is the risk that if it does that, that will be too short a time to do the necessary studies. And that the environmental impact statements that are prepared, will be inadequate and will be thrown out by the courts. The regulations do allow the head of the agency to say that they need more time, so it does have that degree of flexibility.

BASCOMB: Now, how likely is it that Mr. Trump has had any personal experiences as a real estate developer with these NEPA regulations?

GERRARD: So many of the developments that Trump wanted to build in New York were subject not so much to NEPA, but to the New York State equivalent of that, and that held him up in many instances and in some occasions, that actually led to stopping the project. Years ago, he wanted to build one of his golf courses in Westchester County north of New York City, next to a drinking water reservoir that was a sole source of drinking water for the village of Mount Kisco. Mount Kisco hired me to oppose the project because they were afraid that the pesticide runoff from his golf course would contaminate their drinking water. We were able to show through the environmental impact statement process that that was a real risk. That led to several years more delay in Trump's project and he ended up canceling the golf course entirely. And the drinking water supply of Mount Kisco was protected.

BASCOMB: Well, what happens now with these proposed NEPA rules, I mean, this seems ripe for a legal challenge. And I understand there's also a public comment period coming up.

Michael Gerrard is Professor of Environmental Law at Columbia University, and Founder of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Gerrard)

GERRARD: So there's a public comment period, a whole lot of comments will come in, it'll take quite some time to go through the comments. They may or may not finish before the election. Once the new regulations do go into effect, if they survive, they will definitely be challenged in court. I would expect multiple lawsuits. But that can't happen until the regulations are in final form.

BASCOMB: And so how likely is it that you think these proposed rule changes would actually go into effect?

GERRARD: I think there's a good chance that they won't ultimately survive either as a result of political actions or because of litigation, but it's really too early to tell. We can't be confident of that.

BASCOMB: Michael Gerrard is a Professor of Environmental Law at Columbia Law School. Thank you for taking this time with me today.

GERRARD: Thank you.

Related links:

- Click here to read the White House Fact Sheet on the proposed regulations

- Click here to learn the basics of what NEPA does now

[MUSIC: Sessa, “Tesao Central” on Grandeza by Sessa, Boiled Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A look at how communities in Appalachia and Wales coped with changing economics when the coalmines shut down. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Buckshot Lefonque, “James Brown (Parts 1 & 2)” on Music Evolution, by B. Marsalis, Columbia Records/Sony Music Entertainment]

Note on Emerging Science: Plastic-Eating Mushrooms

Every year, approximately 300 million tons of plastic is produced around the world. Very little of it is recycled, leaving a large majority to end up as plastic pollution in nature. (Photo: Bastian, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Just ahead, as coal mines in the US and the UK shutdown former coal communities on either side of the Atlantic look to each other for support. But first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

LYMAN: Worldwide approximately 300 million tons of plastic is produced annually, but only a tiny percent of that plastic is recycled. Now researchers have discovered something unexpected that might help deal with discarded plastic - mushrooms. Researchers from Yale University discovered a species of mushroom Pestalotiopsis microspora in the Amazon rainforest that is able to feed on polyurethane a key ingredient in many plastics. Scientists estimate that most plastic will take about 400 years to decompose on its own. But in controlled experiments, mushrooms were able to break down plastic in just a few months, safely converting it into organic matter or compost. Another study by a researcher at Utrecht University in the Netherlands found several other species of mushrooms that can consume plastic, including common edible species, like the oyster mushroom. If the mushrooms are proven safe to eat after they've broken down the plastic, they may have the additional benefit of providing a food source for people. The initial results are promising but the question of scale remains. The mushrooms in the experiments took several months to degrade a relatively small amount of plastic. Can plastic eating mushrooms keep up with global plastic production? And is there a way to process bigger batches of plastic? Researchers are working on addressing these issues as they continue to experiment with an interesting new way of recycling plastic waste. That's this week's note on emerging science. I'm Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Smithsonian Magazine | “Chow Down on a Plastic-Eating Fungus”

- Click here to read a story on the biodegradation of polyurethane by this fungus

After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales

Picture of a Kentucky Mine Supply building in downtown Harlan. To this day, protests over unpaid Kentucky coal miners continue. (Photo: Tom Hansell)

CURWOOD: Some of the fiercest opposition to climate action in the US has come from regions that built their economies on fossil fuel extraction. Think Texas and Oklahoma for oil and gas and especially Wyoming Kentucky, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio for coal. Those regions have been hit hard economically as coal production dropped, leaving miners out of work, and their communities with shrunken tax bases and fewer paying customers for local businesses. It’s a story that has also played out in Wales in the UK. The experiences on both sides of the Atlantic are the theme of Tom Hansell’s new book, After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales. Tom Hansell joins me now for more. Tom, welcome to Living on Earth!

HANSELL: Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So, Tom, how did you get involved with the story of After Coal?

HANSELL: I learned about this long-term exchange that had been started by, through the center for Appalachian studies here and learned that they were bringing students and community members over to South Wales where the coal mines had shut down in the 1980s. And so I thought that would be really interesting to go over, gather stories of how those communities had survived, bring them back to Appalachia, and start an international conversation about how communities can survive the loss of the main industry that, that they were built around.

A coal washery windfarm at Onllwyn, Wales. (Photo: Tom Hansell)

CURWOOD: Now, one of the most interesting parts of your reporting here, Tom, is about the unions. And in both places, unions have been a major part of how these coal communities’ function. And one of the things that's really interesting about the union phenomenon, it's, it's like a huge, almost secular society of the people who live in these communities. They literally provide meeting places but it's a way that everyone relates. So talk to me a little bit about the history of that and how communities today can fill up that space.

HANSELL: I was really interested to learn that in Wales, the unions were not just doing these gathering spaces you were talking about and building political power for the miners, but they were also providing continuing education services. There was a whole system of miners' libraries and free courses after hours so that miners could continue their education and fully participate in, in civic life, which I thought was really interesting. And then other kind of cultural aspects of the unions including male voice choirs or brass bands are big things happening in the UK. In Appalachia, union halls also very much community gathering places, places where local foods are celebrated, places where you can hear great traditional music. But the difference between the actually complete domination closed shop and nationalized industry in the UK and the private industry and the, the lesser power of the unions in the United States was also pretty much a stark contrast. So I think the key question that you asked, looking for the future, is these social spaces, these cultural spaces, these democratic spaces, for the most part, were built up around this industry, and what is there to take their place when the industry crumbles? And I think that's really important. I think people are still gathering sometimes in churches or chapels, sometimes around arts projects. There were some interesting arts projects, particularly the higher ground of Harlan County project that I followed in Eastern Kentucky that provided really interesting ways for diverse groups of people to participate in making something new that spoke to their identity and their history and their hopes for the future. I think there's, there is a lot of community life happening, but it's perhaps a lot more dispersed than it was in the days when union halls were the place that you went to see your neighbors and to get together.

The local market in Ystradglynlais, a Welsh mining community. (Photo: Tom Hansell)

CURWOOD: You spend quite a bit of time in your book talking about how essential it is to support communities and help them prosper for our overall society to stay stable. So in this time of the climate crisis, with the potential for so many more communities to get left behind in the energy transition, how do we support those communities affected by taking the economy greener and climate disruption?

HANSELL: I'm glad you brought that up, because that is actually one of the central points that the After Coal Project tries to address and obviously, we have to address the climate issue. That's what the science tells us. And it's crucial to do it sooner rather than later. At the same time, I believe that the only way to get deep and lasting solutions is to reach out very first to people that have been part of an extractive economy, whether that's the oil fields, or the gas fields or the coal fields. These places that have been built up around a single industry need other options, and sometimes and maybe need some extra support. I would argue that particularly in the case of the coalfields, the coal fields power of the United States, for most of the 20th century. There was coal that helped us win world wars, there was coal that helped build the strongest industry and economy in the world. And very little that wealth was left behind. Most of that wealth went to corporations that were headquartered outside of the coal fields. And there needs to be some system where some of that wealth gets returned and some of the opportunities that coal provided to the nation get returned and focused back in the coal fields. Especially important as those jobs are being lost and as we're experiencing this shift from a fossil fuel powered economy to a greener economy. It's really crucial to bring the most vulnerable populations along.

CURWOOD: One way that you cite that is helping to restore these communities is the power of things like local food and the arts. Talk to me a bit about that.

Women of the DOVE workshop, which is aimed at helping workers left behind by a global economy in the South Wales Coal Mines. (Photo: Tom Hansell)

HANSELL: I was actually really impressed at the amount of local farming that's sprung up really during the time of the After Coal Project. My last project was actually looking at the controversy around a coal-fired power plant in southwestern Virginia. In Wise County, Virginia. That plant eventually was built. It's actually one of the most recent coal-fired power plants built in the US. And as a result, I wanted to do these public forums in Wise County and was working with local organizations to talk about what a greener energy future might look like there. So I called them the Wise Energy Forums. But it was interesting at those forums, people wanted to talk about farming and agriculture and local foods. And it took me a while to listen and to understand that when they were talking about diversifying the economy, that's where they saw their assets, and that that was really important to follow their lead. And what's happened since that time and even since the time the After Coal Project is gone, is that local foods and local agriculture have really exploded in the coal fields. There is a former miner name's Shane Lucas, who created a small farm on his family's land, was connected with a network of farmers markets. And now that that network is actually expanded, this is in Letcher County, Kentucky. And they have a project where the local health care agency was able to use some of the Medicare expansion funds to offer kind of like tokens, but prescriptions for fresh vegetables from the farmers market. So they give their patients tokens to get fresh vegetables. The patients can go down, turn in those tokens to the local farmers like Shane Lucas, the former miner, and then the local farmers bring them back to the health care provider and get paid in cash. And so what you end up doing is dealing with issues like diabetes by increasing the amount of fresh vegetables, dealing with issues like economic development by supporting local farmers and supporting the local health care industry. So I think that's a really fascinating example and one that I didn't get a chance to get into as deep in the After Coal book, but it's really nice for me to see these projects grow and build from the coal fields.

CURWOOD: Now how did having the people in Appalachia and in the southern part of Wales, in those communities that used to do largely coal, how did it help these folks move forward when they got together, when they did these exchanges, when they went to visit each other and their places?

Filmmaker Tom Hansell (left) and Suzanne Clouseau (center) interviewing Geraint Lewis (right) in Abercraf, Wales where in 1966 an avalanche of coal waste killed 144 people. (Photo: Tom Hansell)

HANSELL: That transition was going on whether the After Coal Project was happening or not. I'd like to think it perhaps provided people a way to reflect, maybe provided some new ideas, some ways to brainstorm. I think, ultimately, you know, if you look at the per capita income in each place, it hasn't dramatically changed since I've done the After Coal Project. But I do think that the economy has diversified. And I would say that both these conversations and the After Coal Project as a whole, have increased the recognition of locally-driven organizations that are doing the work. So I've for example, spend a lot of time with the Dove Workshop in Banwen, Wales, an educational workshop that now has a small restaurant catering, business and childcare business all opened in a former coal mine office. Likewise in Appalachia I was able to work with the southern Appalachian labor school in Oak Hill, West Virginia. They actually have taken over a former school in that town that had closed down due to school consolidation. And we did things like a fundraising dinner and film screenings. Working with the Apple Shop Media Arts Center in eastern Kentucky, we did a music exchange where we brought musicians from Wales over to their annual festival, the seat time on the Cumberland festival and did a performance and a discussion there. We also brought performers from Appalachia over to Wales to the Hay Festival and did a performance and discussion. So you know, in terms of a bottom line, how much it's increased the per capita income, I'm not sure we can measure that. In terms of how it's participated in building a movement and supported the people that are in these communities on the ground doing the work, I feel pretty good about that.

CURWOOD: I'd love to hear some of the music that you had in those exchanges.

HANSELL: Yeah, I think the piece that I will definitely share with you all was a performance that took a song that originated in Wales as a hymn called Calon Lan was brought over to the United States and became a bluegrass gospel song that you might be familiar with called Life's Mountain Railroad. And that's a really fascinating story, and you can hear it in the melody of that song.

CURWOOD: Let's take a listen.

[MUSIC: Frank Hennessy, Lolo Jones, Trevor McKenzie and Rebecca Branson Jones, medley based on "Calon Lan." ]

CURWOOD: So this is not a fair question Tom, but here it comes.

Tom Hansell is an award-winning filmmaker and author of After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales. (Photo: Tom Hansell)

HANSELL: Yeah. All right.

CURWOOD: In the end, what, what do you think these communities in Wales and Appalachia got out of the After Coal Project?

HANSELL: I think the first thing is the people that directly participated in the project, there were dozens on each side in Appalachia and Wales, I think gained a little bit of a deeper understanding and appreciation of not just their own communities, culture and history, but how it connects to and relates to other culture and history. I think, also, that a lot of people did actually get the opportunity to travel. There were several people that we were able to bring back and forth and I think it will be interesting to see what happens next. There's definitely talk of a youth media exchange. And there's actually two reporters from West Virginia Public Broadcasting that have recently gotten a grant to go over to Wales and explore a little more of this idea of Life After Coal. I think that there have been some lasting connections that have been made and that will continue to be fruitful, hopefully over the next decade or two or three.

CURWOOD: Tom Hansell's book and documentary projects are called After Coal: Stories of Survival in Appalachia and Wales. Tom, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

HANSELL: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The After Coal Project

- A musical collaboration between Appalachian and Welsh participants in the project featured in the story

[MUSIC: Frank Hennessy, Lolo Jones, Trevor McKenzie and Rebecca Branson Jones, medley based on "Calon Lan." ]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, Candice Siyun Ji, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe. org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth