February 7, 2020

Air Date: February 7, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Democrats Unveil CLEAN Future Act

View the page for this story

In the face of the climate crisis, the House Energy and Commerce Committee released a draft of the CLEAN Future Act, a plan to put the United States on track for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Congressman Paul Tonko of New York’s 20th District joins Bobby Bascomb to discuss how the act seeks to leverage public and private dollars to drive electrification of the transportation sector, decarbonization of the electricity grid, green jobs growth and more. (07:18)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb discuss the one brief nod to the environment in President Trump’s State of the Union speech. Also, a locust plague of biblical proportions is threatening livelihoods and food security for millions in the Horn of Africa. Finally, in anticipation of Valentine’s Day, Peter Dykstra celebrates another, less saccharine February 14 milestone: the founding of the Society of Environmental Journalists. (04:37)

How Wildfires Affect Water Quality

View the page for this story

As the Australian bushfires continue to rage, we take a look at how wildfires, and the methods we use to fight them, can seriously impact water quality downstream. Host Bobby Bascomb sat down with Newsha Ajami of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment to discuss the impacts of wildfires on water quality, and what can be done to mitigate the damage. (07:57)

Regrowing Australian Forests

View the page for this story

After years of repeated bushfires, some of Australia’s eucalyptus forests can no longer come back on their own, so humans are giving them a helping hand by carefully collecting and distributing their seeds. Owen Bassett of Forest Solutions and Host Bobby Bascomb discuss how the re-seeding works, and the impacts of prolonged drought and climate change on Australian forests. (10:07)

Sounds of Winter

/ Sy MontgomeryView the page for this story

Listen closely. The frigid months of winter have a sound uniquely their own. As commentator Sy Montgomery points out, the austere quality of winter helps it sound vibrant. (04:01)

Wine Regions Struggle with Climate Change

View the page for this story

As the climate changes, the wine-growing regions of the world are shifting location. Professor Elizabeth Wolkovitch of the University of British Columbia joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about how viticulture will be impacted by climate change and how it can adapt. (09:47)

Feed Your Ex to a Bear for Valentine's Day

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

Wildlife centers are offering some catharsis for anyone feeling bitter at an ex this Valentine’s Day. For a small donation, people can name a fish or cockroach after an ex and then watch a livestream of it being fed to a predator. Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill sits down with Host Bobby Bascomb for the details. (02:42)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Newsha Ajami, Owen Bassett, Sy Montgomery, Paul Tonko, Elizabeth Wolkovich

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Aynsley O’Neill

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

House Democrats look to the 2020 presidential election as they unveil sweeping climate change legislation. The goal- net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

TONKO: We are not going to let a climate denier, sitting in the White House, be a factor to slow us down. Because there is no time that we can waste with this crisis. We have used this time to build a package, and when there is acceptance in the Executive Branch, we'll be able to roll forward.

BASCOMB: Also, as the planet heats up the wine producing regions of the world are beginning to shift.

WOLKOVITCH: Roughly speaking, cooler regions growing wine grapes now are the winners, hotter regions are the losers but it really depends on what places choose to do. So, France for example where many of the most famous varieties come from sees balance losses and gains.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Democrats Unveil CLEAN Future Act

Solar panels are one of the most prominent forms of generating clean energy. (Photo: Pieter Morlion, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

The House Energy and Commerce Committee recently unveiled the CLEAN Future Act, a plan to tackle climate change. It translates many of the ideas laid out by the Green New Deal into specific policies. The overarching goal is for the United States economy to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Highlights include a national climate bank that would channel public and private funds for green investments, especially in communities disproportionately impacted by climate change and pollution. Also a "Buy Clean" initiative would encourage more sustainability in federal work projects. Congressman Paul Tonko is a Democrat representing New York’s 20th district.

He chairs the Subcommittee on Environment and Climate Change within Energy and Commerce and has worked closely on the draft legislation. Congressman Tonko, Welcome to Living on Earth!

TONKO: It's my pleasure to join you.

BASCOMB: Now, I understand the CLEAN Future Act is still being worked on. But it's already over 600 pages, and we'll unpack a few of the specifics. But broadly, what does this bill intend to cover?

TONKO: Well, it basically is a very strong response to the climate crisis. This is a bold, innovative draft, to put Congress in the position to advance comprehensive climate action at the earliest opportunity.

BASCOMB: Well, let's talk about a few of the specifics here. Our largest source of emissions as a country, close to 30%, comes from the transportation sector. How do you intend to bring that number down?

TONKO: Well, certainly electrification within the transportation sector is important. So this bill is all about targeting pollution. And with that, we create a national climate bank that will enable individuals to receive the efforts of public and private financing that will enable us to transition to a clean economy, including electrification of that transportation sector, and making certain that we move to clean transportation.

BASCOMB: Well, if you want to electrify the transportation sector and our electricity comes from coal, that doesn't do much good in terms of emissions. Can you tell me what your plan is to make our electricity generation more, more green?

TONKO: Sure, in the energy generation sector, if we're going to electrify the transportation sector, of course, we want that to grow cleaner. So every effort is made to put competition in play with the pollution that comes and so the standards that we develop, the opportunities we offer for a competitive federalism, so to speak, enables these energy generating players to buy into the concepts of responding to the 2050 goals. So that will develop, I believe, more reliance on renewables, more reliance on energy efficiency and on innovation. I think we will see the the market shift accordingly. We have state climate plan initiatives that are part of our package so that it fosters cooperative partnerships between the federal government and the states, or compact of states, to ensure that each state or region will achieve those national climate targets. It will direct the EPA to develop a menu of policies, which states can implement, and it also includes a federal backstop to ensure that our emission reductions in the states is going to be targeted in a way that they will have to respond with an approvable plan if they're missing those targets.

BASCOMB: Now, it seems that whenever this idea of reining in emissions comes up, there's always a knee-jerk reaction from some to say, "Oh, no, we can't do that. It's going to destroy our economy." How do you respond to that sentiment, and what provisions do you have here to soften the blow for businesses and industries that might be impacted?

Electric buses are a clean-energy option for mass transit. (Photo: LoveofZ, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

TONKO: Right, there will be targeted assistance that we can provide with our policies. I would also argue that there will be many, many jobs created not yet on the radar screen that will enable the economy to grow. And certainly, the investment in technology and innovation in research is important. I believe that there is a global effort going on as we speak, that is compelling for us to be involved. And basically, overall, the mantra here is like the cost of inaction overwhelms, I believe, the cost of taking action here.

BASCOMB: Now, Congress has tried and failed before to address climate change, most notably with the Waxman-Markey bill in 2009 that passed the House, only to die before it ever even reached the Senate floor. What makes this bill different?

TONKO: Well, I think a lot has changed in 10 years. The Waxman-Markey bill was a major effort that, as you cite, was approved by the House. But you know, the cost of renewables has dropped significantly, well beyond what they had forecasted. The economy is much stronger. You know, we were at the, in the shadows of a recession, and the Obama administration led that march upward, and so I think now we have a better economy. The general public has bought, has accepted this concept. It's no longer simply about polar bears; that matter. But it's a backyard issue. You know, flooding in Nebraska, record rises of the Mississippi, wildfires in the Southwest, people watching the news and seeing international flooding like never before. They have now come to understand that there is something to this climate concept, and the climate crisis is real. So we believe that there is great opportunity here to get favorable response to solving the climate crisis.

BASCOMB: And yet, you know, sitting in the White House, we have a President who has called climate change a hoax. How likely is it that he would sign off on this kind of legislation, or are you may be hoping to run out the clock and next year have a President who's more willing to work on this issue?

TONKO: We are not going to let a climate denier that calls climate crisis a hoax, sitting in the White House, be a factor for us to slow down. In fact, we have used this time while the denier is in the office to build a package, and now have people respond to that package. So we're not wasting any time because there is no time that we can waste with this crisis. And when there is acceptance in the Executive Branch, we'll be able to roll forward.

BASCOMB: And what kind of reception are you receiving from your Republican colleagues?

TONKO: Well, you know, people are looking at the bill. It's new, it's thick and bulky and voluminous. But what we have here is a proposal that even includes a number of Republican proposals that are in our package, including efforts for energy efficiency, funding for carbon capture and the like. So we're just actually working with individuals out there and aggressively moving forward and asking people for their input. Many hearings have been held to get us to this point and I'm certain many hearings will be held to fine-tune our package.

BASCOMB: Congressman Paul Tonko represents New York's 20th District and is Chair of the Subcommittee on Environment and Climate Change. Thank you so much, Congressman Tonko, for taking this time with me.

TONKO: It has been my pleasure and I appreciate the interest you have shown.

Related links:

- CLEAN Future Act Fact Sheet

- The CLEAN Future Act, section by section

- More climate info on Congressman Paul Tonko's website

- Draft text of CLEAN Future Act

- CLEAN Future Act press release

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, unnamed original tune]

Beyond the Headlines

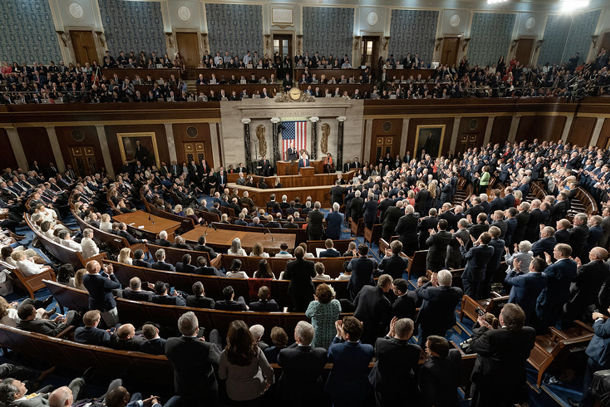

In his State of the Union Address, President Trump celebrated energy independence without mentioning the possibilities of wind and solar power. (Photo: Joyce N. Boghosian, The White House, Flickr, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, did you happen to catch the State of the Union this week?

DYKSTRA: I did, Bobby. I never miss it because I want to hear the six or seven words spoken about the environment, and Donald Trump didn't disappoint.

BASCOMB: What did he have to say?

DYKSTRA: Well his only line that was strictly about the environment came midway through the speech. Before that he did brag on energy independence, mentioning only oil and gas, and not that energy independence might possibly include the rapid growth of wind and solar. Then about halfway in, Donald Trump very briefly decided he would speak for the trees.

BASCOMB: Okay, a Lorax moment, let's hear it.

PRESIDENT TRUMP: To protect the environment, days ago I announced that the United States will join the 1 Trillion Trees Initiative, an ambitious effort to bring together government and private sector to plant new trees in America, and all around the world.

BASCOMB: Um, a trillion trees. Wow, that sounds ambitious. But how realistic is that goal?

DYKSTRA: Oh, it's it's not. It would certainly help to plant 2 trillion trees. It's not only not realistic, though, if you do the math, but it would be a danger in the sense that it would make us think we're solving the climate problem when it's only a partial solution at best. In order to cancel out US carbon emissions, you would have to cover land twice the size of Texas with trees in order to do this.

BASCOMB: Okay, well, that's going to be a tall order, to say the least. Hey, by the way, who was the Designated Survivor this time around?

DYKSTRA: This time, it was Interior Secretary and former oil lobbyist, David Bernhardt. You can draw some possible conclusions about the fact that if there's so little about the environment in the speech, the Secretary of Interior can stay home, get a bowl of popcorn and watch on TV. The Designated Survivor, of course, is the one cabinet member that's left behind that doesn't attend the speech in case there's some kind of disaster. That person would become president in the line of succession, meaning we would have a guy who was an oil lobbyist a year and a half ago become president of the United States. It's actually the sixth time an Interior Secretary has been the Designated Survivor. That's tied for first place along with the Secretary of Agriculture.

BASCOMB: All right, Peter. Well, what else do you have for us this week?

The devastating locust plague threatens to continue spreading. (Photo: Eonora (Ellie) Enking, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We're gonna go straight to the book of Exodus, specifically, the plagues that God directed Moses to visit upon the Pharaoh of Egypt. And number eight, was the plague of locusts. Right now there is a plague of locusts afflicting the Horn of Africa. It's something that was called quote, "an unprecedented threat to food security and livelihoods throughout the region."

BASCOMB: Man, and I'm sure that's in an area that could hardly stand to have another challenge thrown at them much less a plague of locusts.

DYKSTRA: No they don't really need any biblical metaphors like that.

BASCOMB: No, indeed. Well, what do you have from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: Oh, shout out to some good friends of ours. The Society of Environmental Journalists has its 30th birthday on Valentine's Day, back in February 14, 1990. They were inspired by a diss from the famous ABC news reporter Sam Donaldson, who talked disparagingly about, quote, "the ecology beat." Some reporters got together, including Pulitzer Prize winners, founded the Society of Environmental Journalists. Now 30 years later, into the, we're going into the third decade of the 21st century. SEJ has 1300 members, and it is a wonderful resource for people who write and report on environmental journalism. And Bobby, can you name any other entity, a nonprofit dedicated to environmental journalism that's been around for anywhere close to 30 years?

The Society for Environmental Journalists (SEJ) boasts members from more than 43 countries. (Photo: Jon S, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, I think I know where you're going with this. I can, in fact, Living on Earth has been around for nearly 30 years now.

DYKSTRA: It's been around forever. Both Steve and I are near charter members of SEJ. And Steve, of course, is the charter member of LOE.

BASCOMB: All right, Peter, well, thanks for reminding us of those great milestones. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks again, Peter. We'll talk to you real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more any stories on our website loe.org.

Related links:

- Click here for an explanation of the State of the Union’s Designated Survivor

- Read more about the locust plague

- More on the Society for Environmental Journalists’ work and history

[MUSIC: Booker T. & the MG’s, “Time Is Tight” on I’ll Take You There: Voices In Classic Soul, Hear Music/Rhino]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Rain helps put out wildfires but it can lead to disaster for nearby waterways. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Booker T. & the MG’s, “Time Is Tight” on I’ll Take You There: Voices In Classic Soul, Hear Music/Rhino]

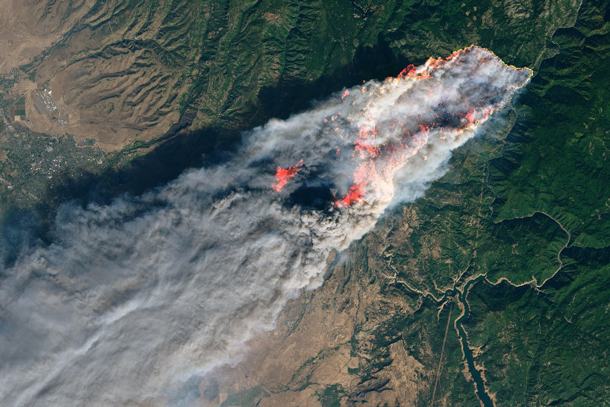

How Wildfires Affect Water Quality

Debris from wildfires can flow downstream, carrying toxicants from nearby towns and cities (Photo: Joanne Francis, Unsplash)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

During a wildfire, like those still raging in parts of Australia, firefighters pray for rain to help them battle the blaze. And though rain brings relief it can also lead to a whole new set of problems for local waterways. For more, I’m joined by Newsha Ajami. She’s a hydrologist at Stanford University and sits on California’s regional water quality board.

Newsha, welcome to Living on Earth!

AJAMI: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So, generally speaking, how does wildfire affect water in nearby rivers and streams and even lakes?

AJAMI: So, basically, wildfires change the landscape significantly, and they actually can create a deluge that eventually with the rain and the storm can end up in the water systems. Now, if the wildfire has an interface with urban areas, that becomes a lot more intense, and it will include more toxic materials from the burning of the chemicals, electronics, appliances, and a lot of other daily fixtures in our household. Also, smoke can eventually travel and go to different places and transport some of these chemicals through atmospheric processes. So, some of these impacts can go beyond the region that has been experiencing fire.

BASCOMB: And you talked a bit about urban areas and the things that could wash off into rivers there, but what about, you know, in a more wild area?

AJAMI: Yeah, so those are more natural materials that get burned, right? Trees, bushes. And it doesn't necessarily create chemical pollution in our water systems. However, it still can impact the waters by creating a smoke smell in the water or actually sediment that needs to be cleaned up. So, it's slightly different, but they both can impact the water quality.

BASCOMB: And what about the use of chemicals to put out fires? Those must also make their way into the water.

Fire suppressant chemicals such as Phos-Check fire retardant absorb oxygen, and when they wash into rivers following fires, can damage the oxygen balance of waterways. (Photo: Ben Kuo, Unsplash)

AJAMI: So yes, those fire retardants include some chemicals that are used to sort of suck oxygen out of fire and make sure it turns off, right? So it doesn't grow more. But those chemicals, actually, if it's washed off, it ends up in some of the water bodies in the close proximity to the fire area. It can have a lot of impact.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm. Now, I've read that some of the streams in Australia actually began to boil, if you can imagine that, during the fires there. That's of course, a really extreme case, but generally speaking, how are the wildlife in these areas impacted both during and after the fire?

AJAMI: They actually can be significantly impacted. We have to remember: they are the first receiver of some of these chemicals, and contaminants, and materials, and pollutants. And because of their body size, they are much more vulnerable to some of these chemicals and they can be significantly impacted. And also remember, water quality degradation is not just for the chemicals, also heat can be a water quality problem. And the freshwater ecosystem or marine ecosystem are very sensitive and vulnerable to some of these extreme changes in the temperature. Sometimes various regions have experienced big loss of these species due to some of these wildfires.

The aftermath of the 2014 Carlton Complex Wildfire from across the Okanogan River in northern Washington (Photo: Adam Cohn, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Now, what kind of impact can wildfire have on drinking water in an area?

AJAMI: Depends on what kind of wildfire we're talking about. If the wildfires are happening in the rural area or in the forest area, or an area that's not necessarily interfacing with human urban areas, they can impact the amount of sediment in the water or the smell of the water. When we're talking about the urban areas, sort of being part of these fires, and if you have this whole, urban wildland interface being burned, then we can have some metals or other chemicals that we use in our daily lives ending up in the water that needs to be cleaned up and handled or managed differently.

BASCOMB: After a wild fire that burns hundreds or thousands of acres, how in the world can you clean that up?

AJAMI: So, for example, when we had the fire in Northern California a couple of years ago, the Army Corps of Engineers in collaboration with the Regional Water Board and a few other entities set up a coordinated effort, and they all went and cleaned up some of the sediment and sort of sandbagged some of the burnt areas. And that was very helpful to make sure some of these materials doesn't end up in the water systems. And one other thing I have to actually mention is these fires can also increase the possibility of erosion, especially when it's in the wildland. We experienced that in California in the Santa Barbara area because there was some fire that burned some of their wildland and urban areas. And then afterwards, we had an intense rainy season, which caused some landslides due to the loss of species that helped to keep the soils together. So that can also be one of the side effects of these fires.

After the November 2018 Camp Fire in Northern California, emergency response teams in Butte County relied on experts to evaluate wildfire impact and identify areas likely to experience flooding, debris, and mudslides (Photo: Stuart Rankin, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0))

BASCOMB: Now, you, of course, are an expert on California and the waterways there. But the world is looking to Australia right now as they battle with intense fires there. What are your thoughts on the Australia fire and how does that compare to what you've dealt with in California?

AJAMI: It is truly devastating and really worrisome, to be honest with you. I wonder if that's where we're looking at in a few years. Because right now, there have been chain of fires happening there. A lot of people have been impacted. A lot of wildlife have been impacted. And it's truly devastating. So far in California, our fire season has definitely been extended and has become longer and we have fires different times of the year now. And every year, we just hope that, you know, we can manage to make it through it. But, with Australia, right now their fire season haven't even started and the country is burning like this. So, God knows what's ahead of them.

BASCOMB: It's scary to think of. I mean, the thing is this problem with wildfires, it's not going to go away. As you mentioned, it's likely only to get worse. What do you think can really be done to mitigate the potential impacts on you know, specifically water that we're talking about here?

Newsha Ajami is Director of Water Policy at Stanford's Woods Institute and a member of the California Regional Water Quality Board (Photo: Stanford Woods Institute)

AJAMI: One point I'll make, we have to definitely reconsider how we are treating the water, how we are handling post-fire management. Actually, some of the most important work that we can do should be done pre-fire. So we are trying to manage land in a way that we can either reduce the intensity of some of these fires or prevent them from happening by doing forest management, wildland management, to make sure that we can reduce the intensity of these fires, or actually prevent them from happening. One might think, okay, the comments that I just made, this has nothing to do with water. But the reality is if we can't prevent these fires to happen, it can eventually impact our water bodies. That means that some of the water agencies and water utilities and different layers of local government and state government and federal government that are dealing with water and its accessibility should be considering to invest in the efforts to prevent or reduce intensity of some of these fires.

BASCOMB: Mmhmm.

AJAMI: I would say that's the cheapest and easiest way to get involved. Then we have to also consider how we need to change our treatment process or work with some of these groups that are on the ground to help us to clean up after the fire as fast as we can, deal with some of the post-fire sediments in a strategic way, that we don't impact our water bodies.

BASCOMB: Newsha Ajami is Director of Water Policy at Stanford's Woods Institute and she sits on the California Regional Water Quality Board. Newsha, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

AJAMI: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Click here to read about Professor Ajami’s work with the Water in the West initiative at the Stanford Woods Institute

- Yale e360 | "How Wildfires Are Polluting Rivers and Threatening Water Supplies"

- Learn more about scientific research in your watershed

[MUSIC: Voice Of the Turtle, “Estaz caza” on Balkan Vistas – Spanish Dreams, traditional Bulgarian wedding song, Titanic Records]

Regrowing Australian Forests

A helicopter sowing alpine and mountain ash seed into the ash of a recent bushfire. (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

BASCOMB: The Australian fires have so far burned an area nearly the size of West Virginia. The bushfires have burned through dry habitats home to many of Australia’s most iconic species like koalas, kangaroos, and wallabies. They’ve even burned the more humid eucalyptus forests, home to the lyre bird, lead beater possum, and the great glider – an animal so adorable it’s been nicknamed a flying teddy bear. Some of these humid forests aren’t naturally equipped to deal with frequent fires and are struggling to grow back on their own. But humans are helping give them a shot at recovery. Owen Bassett is Director of Forest Solutions which is helping the government re-seed forests in Victoria and New South Wales. He joins us from Melbourne, Victoria. Owen, welcome to Living on Earth!

BASSETT: Thank you for having me. It's a pleasure.

Australia’s ash trees can grow 80 or more meters tall. (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

BASCOMB: So please describe the forests where you work. What do they look like and what does it feel like to be there?

BASSETT: Yeah, the forests that I work in are tall mountain forests, they're known as ash forest. I suppose in terms of stature they're similar to your California redwoods. So they're very tall, very large trees and sort of a wet forest. So you might think that a lot of Australia is covered in dry forest; most of it is of course, and most of it is arid, but along the southeast corner, we have beautiful wet forests that run up the Great Dividing Range and they are gorgeous to be in. They're cool, they're damp, full of great native wildlife. Yeah, just beautiful to be in and visit, yeah.

BASCOMB: Wow, it sounds, sounds amazing. What kinds of animals live in the forest there?

BASSETT: So yeah, we have all of those marsupials that you American people know about, the jumping ones and the kangaroos; we have a species, or a number of species of wallaby that live in those forests. And we also have arboreals, so these are mammals that live up in the canopy of the forest. And then we have this magnificent songster, I don't know if you've heard of the superb lyrebird. It has the capacity to mimic a whole range of birds and sounds that it hears in the forest. And it's an absolute joy to listen to them. So these forests are sort of like a cathedral to be in. And so sounds like the lyrebird just, they just resonate.

Male superb lyrebird. Lyrebirds can be found in mountain and alpine ash forests and are so skilled at imitating sounds that they can mimic the sounds of chainsaws, camera shutters, and even laughter. (Photo: Brian Ralphs, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: I think we actually have some recordings of the lyrebird we can play here. Let's have a listen.

[LYREBIRD SONGS]

BASSETT: They do have the ability to imitate the shutter sound of cameras.

Young ash trees growing after aerial sowing (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

[LYREBIRD IMITATING CAMERA SHUTTER SOUNDS]

BASSETT: They can imitate the sounds of chainsaws. . .

[LYREBIRD IMITATING CHAINSAW SOUNDS]

BASSETT:. . . dogs barking, all sorts of things like that. But the main repertoire is, is the full suite of other birds that are, and animal sounds that are in the forest.

[LYREBIRD SONGS]

BASSETT: They're quite talented, if you like. [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: So you mention that this is a very wet forest. Why is it burning now, and how common is that?

BASSETT: Yeah, look, it's unfortunately very common at the moment, but it's not common in terms of the forests', I suppose, geological history, if you like. All eucalypts have evolved with fire, so fire is part of the environment here in Australia, a little bit like your California. But the thing is that, you know, we do have a changing climate here at the moment, a drying climate. And we're currently caught in this real cycle of droughts, okay, so, in southeast Australia, we had this mammoth drought. We refer to it as the Millennial Drought. It went for 12 years, from 1997 to 2009. So what that left was this huge legacy of soil moisture deficit. And then we've had a sequence of small droughts since that time. And we're currently in one at the moment. And the problem with the Millennial Drought and the legacy it's left is that every other small drought that comes along has this sort of disproportionate impact. And this year, we've, we have never measured drought index so high. That is why these forests are burning. And in the last 20 years, these forests have burned on average every four years. And because those fires are so, or that interval is so short, the species just can't catch up. The species needs at least 20 years to be able to then reproduce, because young trees don't flower. And so these four year intervals are just too quick and where you get these fires overlapping, then the species is in big trouble. And we're experiencing that now in Australia, is forests that are at the stage of population collapse. Classically, it occurs in species like alpine ash and mountain ash that, you know, require much longer periods of fire intervals to survive.

Australian ash forests are also home to arboreal species like the Greater Glider (Photo: CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: So it sounds like if there was no intervention, these forests would likely turn into some different type of ecosystem altogether, maybe savanna or grassland or something like that. But you and your group, you're intervening, and can you talk about that? What are you guys doing exactly?

BASSETT: Yeah, look so, because these species are obligate seeders, if we have enough seed, and we have the means to spread that seed where the forest is going to experience population collapse, then we can intervene, lay seed on the ground or sow seed on the ground, and these forests will return. But it's easier said than done. So we have to collect the seed, we have to distribute the seed, and that's a mammoth operation, yeah.

An aerial view of an ash forest burned when still too young to produce seed shows no self-recovery. (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

BASCOMB: Mmm. And how does that work? How do you collect them?

BASSETT: So for the last 26 years, I've been monitoring the flowering of these species. So mountain ash, for example, is the tallest flowering plant in the world. And every year I go up in a light aircraft, and I actually map the distribution of the flowering. So once it's flowered and we know where it is in the landscape, one year later, we can expect that there will be seed there. And so at that point, we send climb teams in and they climb these tall 80-meter trees. And they de-limb, just a, we keep the tree alive. We just delimb maybe a third of the branches that are on that tree and we keep the tree healthy, we keep the growing tip in place. And so we take just a section of that crown out and from that, we can pick the seed pods, if you like. They're sent away and the seeds extracted from that fruit or those pods. The seed looks a little bit like coarse pepper, so tiny seeds, the seeds are not, not big and it's extraordinary to think that such a tall tree, something akin to your California redwoods, comes from this tiny, tiny piece of cracked pepper size seed, yeah.

Aerial view of a flowering ash forest (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

BASCOMB: Nature is amazing that way, huh? And so how many pounds of seed or maybe kilos of seed are you getting? And then, and then how do you distribute them?

BASSETT: Yeah, so we need about a kilogram of seed for every hectare. That's about a pound per acre. We distribute these using helicopters. And so the seed is put in a hopper inside the helicopter, and the seed is spun out the bottom of the helicopter. And so you get this picture like, as the helicopter's going along, the swathe of seed is only 20 meters wide, 60 feet, so it's not very wide at all. And so you get this picture, in this huge expanse of burnt landscape, you get this picture of the helicopter having to go up and back, up and back, up and back, many, many times to cover that huge amount of area. Because I'm actually expecting up to ten thousand hectares, so that's like 25,000 acres or something. So it's a, it's a massive operation.

A climber ascends an ash tree to gather seeds to help a burned forest recover. (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

BASCOMB: And so how long have you been doing this type of regeneration with helicopters, you know, distributing the seed in this way?

BASSETT: Yeah, since we started that, I mentioned earlier that we've had fires on average frequency every four years. So since 2003, we've been having to, to sow, aerially sow, seed across large areas to recover forests that are in danger of imminent population collapse. Just last year, we had to do this operation. From all those earlier fires, we have all this young regrowth. So that's burned again, all that young real growth has burned again. So we're even asking the question, you know, you know, should we keep sowing seed, you know? What's, because, we're re-sowing sites now that burned like four or five years ago. And we've always struggled with having enough seed and this year, that's probably a major challenge, is insufficient seed to sow this huge area that we're expecting to have to sow.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I understand that you also have a seed bank that you're working on. Can you tell me about that?

BASSETT: Yeah. So the concept of a seed bank is one that, you know, you put some seed away for a rainy day. We needed 10 tonnes of seed this year. At the moment, we might have a third, maybe to a half of that. Now I've been advocating for a seed bank for about 10 years, and the state government has only ever funded small seed collection operations that were emergency in nature, if you like. "Okay, we've got a bushfire, we'd better go and get some seed."

Alpine and mountain ash grow to hundreds of feet tall, from tiny seeds the size of coarse cracked pepper. (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

BASCOMB: Hmm, it's gotta be very frustrating for you.

BASSETT: Yeah, it's very frustrating. But look, at this stage, we battle on. The question we really do, it sounds a bit corny, but do we want these forests for our grandchildren? And yes, I do. Yes, we do. That's the cry from Australia, is that we want to save these forests. We want these tall forests, we want our grandchildren to be able to walk under them. That's what drives us. That's the passion, if you like, to get these forests regenerated, yeah.

BASCOMB: Owen Bassett is the Founder and Director of Forest Solutions in Melbourne, Australia. Owen, thank you so much for all of your hard work and for taking the time to talk with me.

BASSETT: Oh, thank you for having me. It's a pleasure, yeah.

Recovering ash growth (Image: Owen Bassett [Forest Solutions])

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, "The Train Of Thought" on Elec tric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Unlucky in love this Valentine’s Day? Try feeding your ex to a bear. Well, kind of…. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

Related links:

- Associated Press | “Fires set stage for irreversible forest losses in Australia”

- About Owen Bassett and Forest Solutions

- WATCH: BBC’s “Lyrebird sings like a chainsaw” with David Attenborough

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “The Train Of Thought” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

Sounds of Winter

A beautiful winter landscape. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Well, Punxsutawney Phil did not see his shadow this year, which foretells an early spring. But before the season slips away Living on Earth commentator Sy Montgomery suggests we should stop and take a moment to appreciate the sights and sounds of winter.

[CHICKADEE CHIRPING AND WINGS FLAPPING]

MONTGOMERY: At no other time of the year are sounds so sharp. The scolding winter call of the chickadee. Wind howling through oaks, or whispering through pines. The clarion call of wind chimes, piercing as the cold itself.

[XYLOPHONE-LIKE SCALE OF WIND CHIMES SOUNDING]

MONTGOMERY: Hearing may be the richest sense. Helen Keller wrote she felt its absence a handicap far worse than blindness. As if to make up for winter’s void – of colors muted, touch numbed, and scents sealed – winter’s sounds are the most vibrant.

[WHIZZ OF RUBBER SNOW TUBE SLOWING TO A STOP, CHILDREN LAUGHING]

MONTGOMERY: Sound travels further over frozen ground. Frozen surfaces are rock-hard, so they don't absorb sound – they reflect it. And when the atmosphere above is warmer than the ground, sound bounces back toward the ground. Winter’s freeze is like having a sound reflector in the sky.

[SCRAPING, RHYTHMIC GLIDE OF SKATES ON ICE]

MONTGOMERY: Winter’s bareness amplifies and clarifies its voices. Spring and summer are crowded with ambient noise: the sounds of birds and insects, the rustle of animals in the woods, the whisper of grasses and leaves – not to mention the hubbub of so many people and their machines.

[CREAK OF SWAYING TREE]

The frozen land of Ice and snow has a sound all its own. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

MONTGOMERY: In summer, leaves absorb sound, especially the higher frequencies. But now, the trees are bare, summertime’s murmurs are hushed, and snow is covered with hard ice crust. Sound slices through the air—stark, clear, pure.

[CRUNCH OF FOOTSTEPS IN SNOW]

MONTGOMERY: So this is the best time of year, I think, to go somewhere secluded – just to listen. Listen for the voice of the wind. The ancients said that Boreas, the north wind, loved a nymph who was changed into a pine tree. Boreas still rages and howls through oaks and maples and beech, but his voice is quite different when he speaks to his love.

Listen to the voices of the trees. They creak like rusty hinges as they sway in the wind. Sometimes trees will even pop loudly – it can sound like fireworks – their wood expanding and contracting during sudden changes in temperature.

Listen to the voice of the ice. On a lake, sometimes, you can hear the ice squeak, or crack, or even boom. Even safe, solid ice will make a cracking sound as it expands. Scary to an ice skater – but if you’re walking in the woods, the booming of a lake is like music.

And remember, in winter, that one of the greatest rewards of listening can be silence. Orchestras know this. At the end of a performance of Mozart’s Fantasy in C Minor, a thousand ears strain for the last note.

[PIANO MUSIC RUNNING UNDER]

MONTGOMERY: Silences are different in winter, too. This is not the soft, glowing stillness of pre-spring, or the absorbing quiet of swimming underwater. No, winter’s silence, like its sounds, is piercing, clear and cleansing, like a shooting star, well worth seeking and savoring.

[PIANO MUSIC CONTINUES AND FADES AWAY]

BASCOMB: Sy Montgomery is the author of more than a dozen books including How to Be a Good Creature, Tamed and Untamed, Soul of an Octopus, and the Good Good Pig. For links to her work and our conversations with her, go to the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Sy Montgomery's website

- More about Sy Montgomery

[MUSIC: Mozart Fantasy in C minor K475 Mitsuko Uchida]

Wine Regions Struggle with Climate Change

Chile is a major producer of Cabernet Sauvignon which is usually aged in American oak adding hints of vanilla, spice, and tobacco. (Photo: Fer Quintana, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, Valentine’s Day is just around the corner. For some that might mean a cozy table for two at a nice restaurant and a favorite bottle of wine. Whether it’s a dry cabernet or a fruity pinot noir, people can be passionate about their wine. The 2004 film Sideways was about a man named Miles with very strong opinions on wine. Here a friend is talking to Miles about how to behave as they head in on a double date.

JACK: And if they want to drink merlot, we’re drinking merlot.

MILES: No, if anyone orders merlot I’m leaving. I am not drinking any merlot!

JACK: Ok, ok relax Miles. Jesus, no merlot.

Bordeaux is a dark blue colored grape grown in the Bordeaux region of France. The wine itself is made up of a blend of at least two parts of cabernet sauvignon, merlot and cabernet franc. (Photo: Meghan Cole, Flickr, Bordeaux Chateau Smith, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, according to a recent study, the Miles of the world will have to be a bit more flexible about their wine preferences in the future. That’s because climate change is already wreaking havoc on what grapes can be grown where and the trend is only expected to get worse with time. In fact, a recent study found that roughly 85 percent of current wine producing areas will be lost, no longer able to grow grapes, if the world average temperature rises by 7 degrees Fahrenheit, a scenario scientists believe is possible if we don’t adequately address the climate crisis. For more I’m joined now by Elizabeth Wolkovich. She’s a Professor of forest and conservation sciences at the University of British Columbia. And lead author of the recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Elizabeth Wolkovich, welcome to Living on Earth!

WOLKOVITCH: Thanks for having me. It's great to be here.

BASCOMB: In terms of the wine regions of the world, who are the biggest losers and winners when it comes to climate change?

WOLKOVITCH: Certainly what we see at a broad scale is that regions that are hot now, places like Italy, Spain, much of Australia, where they currently grow wine grapes right now, are already on the edge of which varieties they can choose. So they have a limited amount of diversity to consider planting in the future and that means that in our projections, which do look at just a slice of the diversity, we see those regions seeing major losses without significant gains. So upwards of 80%, or more of the current growing regions in those areas could be lost with warming. On the flip side, places that are cooler like the United Kingdom, Tasmania, New Zealand, the Pacific Northwest of the United States, those regions gain lots of opportunities to grow different wine grapes or more varieties of wine grapes. So roughly speaking, cooler regions growing wine grapes now are the winners, hotter regions are the losers, but it really depends on what places choose to do. So France, for example, where many of the most famous varieties come from sees balanced losses and gains. So we see that they will lose potentially 25% of their regions due to certain varieties that they grow now becoming less suitable, but they can grow later ripening varieties at about the same rate. So you wouldn't really predict major regions in France to go away based on these results.

South African wine was established by the Dutch East India company. Its most common types of grapes are cabernet sauvignon, merlot, shiraz and pilotage. (Photo: Jack Whites, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Is there anything they can do besides just growing different varieties of grapes? I mean, is there any other, you know, agricultural practices that would be useful, anything like that?

WOLKOVITCH: Yes, as with all agriculture, there are lots of different ways to modify a crop to try to deal with warming. So for wine grapes in particular, growers have been feeling climate change for decades now, many of them already have options that they use every year for the most part to deal with the warming. Across California most growers at this point use something called shade cloth that basically just takes some of the sunlight off the berries to try to reduce the local climate right next to the cluster, for example. Growers in California have also switched to micro misters, if they can afford it, so if you think of when you go to the grocery store, and you see those micro misters coming down on produce, people actually install those outside and it has a dramatic effect on the climate right around the plants so that can reduce temperatures. Growers can do other dramatic things like change rootstocks, so wine grapes are different on the bottom than on the top and they have options for trying to change within their vineyard where they grow things. So if they have a slope that's a bit cooler, they might start planting more there. So there's lots of options out there.

BASCOMB: And it sounds like those adaptations, I mean, they could be kind of expensive, you know, misters, and all of these things to introduce, I mean, that's not free and then at the same time, they're probably taking a hit to their bottom line, just in terms of their productivity in the, in the meantime; how do you expect, you know, the economics around growing wine to change in the future?

WOLKOVITCH: Yeah, the economics of growing crops in general and especially wine grapes is a billion dollar or more question right now. Certainly, it's really expensive to change a variety. It's not an easy solution, it's not a cheap solution and it has knock on effects once you've even changed the variety, you have to figure out how to harvest it figure out how to make great wine out of it and none of the solutions are cheap. So places that are large that have a lot of money have already started buying land in other places. Taittinger is a famous maker of champagne from Champagne, France, and they now own a sizable area of the United Kingdom that they believe will be ideal for making champagne wine grape varieties in the future. Major groups in Bordeaux own parts of China in the mountain region that they think will be high quality regions soon, climatically. And so I think the issue is none of the solutions to climate change adaptation for growers are ideal in terms of economics, the questions are which ones are even an option for most growers. Smaller growers really can't think about buying land somewhere else and continually changing what they do in terms of the geography. So even though changing varieties could be a huge economic hit, it might be the difference between continuing to grow wine grapes or not.

Grenache or Garnacha is one of the most common wine grapes and thrives in hot dry condition such as those found in Spain. (Photo: Francisco Martinez Arias Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Can it still be called champagne, if it's grown in England, doesn't it have to be from the Champagne region of France?

WOLKOVITCH: It can't legally be called champagne. So champagne usually contains three wine grape varieties for the most part, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. So you could say you are growing champagne varieties in another place, but you legally cannot call it champagne unless it comes from champagne.

BASCOMB: And I understand that climate change can also actually affect the alcohol content of wine. Is that right? And how does that work?

WOLKOVITCH: Yes, there is lots of evidence that alcohol content in wine has increased probably about a degree or more over the last several decades. So we used to drink wine that was maybe thirteen percent alcohol and it's possible nowadays to grab a bottle that's fifteen or fifteen-point-five percent, that's pretty high alcohol. With higher temperatures growers are harvesting earlier, when you harvest earlier, you basically have to harvest at higher sugar content. And that's just the functional way the berry works: hotter temperatures, more sugar, that sugar goes into the juice and that juice becomes higher alcohol, it's a simple process. And the higher alcohol is actually to the level where lots of growers are looking into de-alcoholizing processes.

BASCOMB: Wow.

WOLKOVITCH: So these can be complicated things where you run the grape juice through a machine to try to get some of the alcohol out. Or I've even heard of growers adding water or trying to do other manipulations to bring the alcohol content down. So it's definitely something that growers around the world are seeing and they're concerned about because they know at some point consumers don't want super high alcohol wine. It's harder to make a good high quality wine when it's that high in alcohol and certainly changing varieties is a way to get the alcohol down and growers know that. So the higher alcohol content comes from keeping the variety you're growing in a certain region there and having to harvest it earlier because it's gotten hotter. But if you shift to a later ripening, more heat tolerant variety, it's going to ripen towards the end of the season and we'll have a more natural sugar level that's much more appropriate to what we think of for wine sugar levels.

BASCOMB: As a consumer of wine, what can you do about this? I mean, it seems like an overwhelming problem.

Eizabeth M. Wolkovitch is an Associate Professor of Forest and Conservation Science at the University of British Columbia. (Photo Courtesy of Elizabeth M. Wolkovitch)

WOLKOVITCH: So as a consumer of wine, I think you have sort of immediate things you can do about how you purchase wine and then the much bigger issue of how much warming are we contributing to as a globe. So at the very local scale, depending on where you live, if you know the winemaker or the growers in your area, you can talk to them about how much warming they've experienced and what they're considering. Growers are often afraid to talk about how much warming they know they have in their vineyard and how they're adapting to it already because terroir, this important term that describes the wine growing region, its soil, its climate, its slope, all these things really come back to climate. And so they know if they admit that their climate is changing, they're saying their terroir is changing and they're, they're nervous to say that but they're interested in what consumers are willing to taste and to try. So as a consumer if you're buying blended wines more often or unusual varieties from a region, if you are more focused on flavor profiles you like over certain varieties. That's what growers want to hear. That's what allows them to make decisions about how they adapt and whether they change varieties. But I will say our research really shows that the biggest impact we can have on wine growing regions and wines we love is by limiting further warming. So adaptation potential works, it works at a three point six degree Fahrenheit warming event, fairly well saving half of the potential losses but it doesn't work that well at a seven point two degree Fahrenheit warming event. We end up losing well over half the current wine growing regions, even if growers make this huge adaptation choice to rapidly change varieties. And I should say at that seven point two degree warming event, which is what we're more or less headed towards by the end of the century, growers have to keep changing. So they don't just change varieties once in our models, they change every thirty or so years to new varieties. So it's a constant cost burden for them and it's unclear how many growers could really continue to do that over the long term.

BASCOMB: Elizabeth Wolkovitch is a professor at the University of British Columbia in forest and conservation sciences and lead author of this study. Thank you so much for taking this time with me.

WOLKOVITCH: Thanks.

Related links:

- The Harvard Gazette | “As Climate Changes, So Will Wine Grapes”

- Inhabitant | “How Climate Change Will Impact Wine”

- Union of Concerned Scientists | “Climate Change and Wine - Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty”

- New York Times | “How Climate Change Impacts Wine”

- Click here to read the study: “Diversity Buffers Wine Growing Regions from Climate Change Losses”

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick et al, “Voyager’s Tale” (single)]

Feed Your Ex to a Bear for Valentine's Day

Metaphorically feed an ex-lover to a bear by naming a fish after them with Wildlife Images Rehabilition Center’s “Catch and Release” promotion for Valentine’s Day. (Photo: patrickmoody, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Valentine’s Day is coming right up, and for happy couples, it’s a time to celebrate their love. But not everyone is happily paired up this year, and some might even be feeling burned by a recent break up. Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill has been looking into some options for those folks that might take the sting out of the romantic holiday. Hey there Aynsley!

O’NEILL: Hi, Bobby, and happy early Valentine’s Day!

BASCOMB: Thanks, same to you! So, what have you been looking into here?

O’NEILL: Well, I have found a few places that will turn your ex into prey for wild animals.

BASCOMB: Umm wow. This took a dark turn really quickly. What are you talking about?

O’NEILL: Not literally, not literally. But take the Wildlife Images Rehabilitation & Education Center in Grants Pass, Oregon. If you have someone in your life who’s kind of slimy, or maybe a bit of a bottom feeder, you can name a fish after them and have that fish fed to one of the center’s bears. A twenty-dollar donation gets you the standard package with a special certificate and livestream access so you can watch the carnage in all its glory.

BASCOMB: Haha, I can imagine that could actually be really satisfying, I don’t know it’s so primal.

O’NEILL: Yeah. Some people will also write the name of a sports team that just keeps disappointing them, or maybe the name of a politician who’s not quite living up to their standards and El Paso Zoo has a similar event, only with cockroaches instead of fish.

BASCOMB: Oh man, I mean every creature is important right? But we don’t think too highly of the cockroach. Somehow it feels I don’t know fitting to name one after a person you’re still angry with.

O’NEILL: Exactly! I feel like seeing a meerkat or hornbill chow down on a cockroach named after an ex-boyfriend has to be pretty cathartic. And the El Paso Zoo then livestreams the feedings for Valentine’s Day and the next few days, so you can enjoy that catharsis for a while.

BASCOMB: Ok, well what if you want to support and you don’t have anybody you are angry with on Valentine’s Day?

The Bronx Zoo will name a Madagascar Hissing Cockroach after your significant other for Valentine’s Day. Why? Because roaches are forever. (Photo: Liz West, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: Ahh…then The Bronx Zoo is the thing for you! Their tagline is "roaches are forever”.

BASCOMB: Yeah, they are.

O’NEILL: It’s perhaps the most romantic way of thinking about an insect known for being a pest that just won’t die. This time, your donation will name one of the zoo’s Madagascar hissing cockroaches after your loved one. And you can get some roach-themed goodies as well, like socks or a candle that…may or may not be roach scented.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I don’t want to think I want a roach scented candle. But you know Aynsley, I don’t want to pry, but do you have anybody in your life that you’d want to name a fish or a roach after?

O’NEILL: Well, I shouldn’t name names, but I can definitely think of a few people in my life who I wouldn’t mind metaphorically feeding to a bear.

BASCOMB: Haha! Alright, Aynsley, well thanks for that report.

O’NEILL: Sure thing, Bobby!

BASCOMB: Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill. And for links about turning your ex into a cockroach or fish, go to the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Wildlife Images Rehabilitation Center’s “Catch and Release” Program

- El Paso Zoo’s “Quit Bugging Me” Program

- The Bronx Zoo’s Roach Program

[MUSIC: Burt Bacharach, “What the World Needs Now”]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Anna Saldinger, Candice SEA-WING Ji, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth