May 8, 2020

Air Date: May 8, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Coronavirus Shocks US Food System

View the page for this story

The coronavirus has affected nearly all elements of the US economy, including food supplies. Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma and other books, says food shortages and massive food dumping during the COVID-19 pandemic expose major vulnerabilities in the American food supply chain. Pollan discusses with Host Steve Curwood how the pandemic presents a strong case for deindustrializing the food system. (13:52)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s installment of Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra fills in Host Steve Curwood on the cozy relationship between the current EPA leadership and coal lobbying. Meanwhile, the Trump Administration is doling out financial relief for oil and gas companies during the coronavirus pandemic, as major fossil fuel companies face huge shortfalls. And in the history calendar, they look back 200 years to the launch of the brig HMS Beagle, which would later carry Charles Darwin around the world. (04:03)

The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court

View the page for this story

Against long odds, in 2007 the United States Supreme Court decided the case Massachusetts v. EPA in favor of the states and environmental groups that had sought regulation of climate disrupting emissions. The case had enormous implications for environmental law, and it laid the legal groundwork for the Obama administration’s climate change policies as well as the global Paris Climate Accord. Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus, the author of the new book “The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court,” discusses with Host Steve Curwood the gripping behind-the-scenes story of how Massachusetts v. EPA made it all the way to the Supreme Court. (28:59)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Richard Lazarus, Michael Pollan

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

How one lawyer sparked the landmark Supreme Court climate change case Massachusetts versus EPA.

LAZARUS: In the world of environmental law, this is our Brown v. Board of Education. Because of the topic, which is climate change, the most important, pressing issue of our time, and because of the practical import. It formed the legal basis of every single one of the significant greenhouse gas initiatives of the Obama Administration.

CURWOOD: Also, Coronavirus has exposed huge vulnerabilities in the way we produce food in the US.

POLLAN: In the same way that we realize it’s a huge mistake to have a country that can’t produce its own surgical masks and depends on China for that. It’s a huge mistake to put all our eggs in one industrial basket. There has never been a more eloquent case for diversifying the food chain, as a matter of national security.

CURWOOD: Those stories this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Coronavirus Shocks US Food System

Health hazards at meat-packing plants have caused food shortages for meat. Pictured, a grocery employee restocking, wearing a mandatory mask. (Photo: Gilbert Mercier, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The pandemic has affected nearly every aspect of the US economy, including the food supply. Dairy farmers are dumping millions of gallons of milk, contract growers are plowing under perfectly good vegetables and industrial livestock farmers are euthanizing animals in the face of a corona virus outbreaks at meat packing plants. And at the same time grocery stores are running short of some supplies, including meat. Michael Pollan is the author of best-selling books including The Omnivore’s Dilemma and The Botany of Desire. He joins me now to explain this disconnect in our food system and the vulnerabilities laid bare by the pandemic. Michael Pollan, welcome to Living on Earth.

POLLAN: Thanks, Steve. Good to be back here.

CURWOOD: So, Michael, we're seeing a lot in the news lately about how the pandemic has affected the American food system: Shortages, massive amounts of food waste public health hazards and the meatpacking plants to name a few. What's happened?

POLLAN: Well, you know, we have a system of incredible efficiency, you know, the legendary bounty of the American supermarket is being challenged by two things. Initially, it was challenged by a demand crisis. At the beginning of the pandemic, you had people hoarding as they do before a hurricane or a blizzard. And this was emptying supermarket shelves, which, you know, is a phenomenon that feeds on itself. But then you moved into a second stage. And that's where I think we are now and increasingly are going to be, which is a supply problem. This hyper efficient system turns out to have some peculiarities that make it very ill suited to the kind of shock it's feeling.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, you're focusing on the fact that we have have what? Two food systems?

POLLAN: Yeah, we really do. You know, half the food dollars spent in America is on institutional food, the food you eat at work, the food you eat at restaurants, at schools, institutions of all kinds. And it has its own dedicated supply chain. And it's a dedicated group of farmers and meat packers and other people feeding into this institutional chain that has its own separate set of companies at every step of the way. It's that food chain that kind of has collapsed because people are staying home. They're not going to work. They're not going to restaurants. And it is proving very difficult to reroute all that food to the grocery outlet. Milk, for example. I mean, you know, in that food chain, it's not sold in quarts, or half gallons. It's sold in giant containers, meant to go into institutions and that milk no longer has a market. Those farmers and their distributors don't have an easy way to move it to the supermarket chain. It would involve new packaging, you know, whole new production lines. So they're dumping it and because obviously you can't store milk very long and they're plowing produce into the, into the ground. And so at the same time, we're seeing this colossal waste of food, you have lines at food banks, you know, hours long that could use that food. So you've got this specialization of supply. That was a great strength when everything was normal, but is an incredible vulnerability right now. And that's just, you know, one of these indicators that a system that's really efficient sacrifices, resiliency, and now it is resiliency that we need.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the difference between an efficient food system and a resilient food system.

POLLAN: Sure. Well, you know, whenever you achieve efficiency, one of the things you're doing is sacrificing redundancy. So when we move from a system where we had hundreds of regional slaughterhouses Then 10s of thousands of small farmers, if there was a problem at any one of those slaughterhouses, it wouldn't be in the newspapers. It would just barely make a ripple in the food system because you had all this redundancy. But over the years, due to lack of antitrust enforcement and celebration of efficiency, we've allowed the meat industry to consolidate to a remarkable extent where you now have, for example, four companies slaughtering 80 or 85% of the beef, and something like 50 plants total are processing 98% of all the meat in the country. So yeah, that actually made meat cheaper. It was a more efficient system. But it leads to a situation where farmers who are raising meat say for a Smithfield plant in Sioux Falls, Iowa, and they're contracted to take their pigs there when they reach slaughter weight, suddenly that place is closed down by the governor because of the outbreak, and they've got nowhere to take their pigs. Because you can't simply feed your pigs longer, they get too big to go into the system and you've got baby pigs coming along very, very quickly. And that's why you see the destruction of all these food animals. Millions of food animals are being euthanized right now, because there's no slaughter plant to take them to.

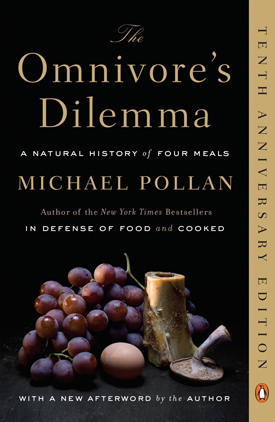

Pollan is most known for his 2006 best-selling book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, where he delves into where American food comes from. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Pollan)

CURWOOD: Now, as you've mentioned, one of the priorities of American food policy for decades has been to keep food, quote, cheap. Now, on the one hand, that sounds great if you're fighting against hunger, and it's less expensive to feed people, but what's the defect in this logic?

POLLAN: Well, as I've been saying, for years, there's a high cost to cheap food. You don't get cheap food without sacrificing other values. And yes, you're right. We have put price at the center: pile it high and sell it cheap is the motto of the American food system. And we've gotten really good at that. But in the process, I mean, we had to make certain sacrifices. One is growing the animals in these brutal conditions, you know, shooting them full of antibiotics and hormones, so they'll grow more quickly and withstand the conditions they live in. And then with the workers, you know, the slaughter plants used to be in Chicago, and they were unionized at great pain during the 20th century. And now, you know, they've moved the plants to the High Plains near the feedlots, to escape unions, by and large and filled them with many undocumented workers who work for, you know, really low, low wages. And they've also made it the most dangerous job in America working in a slaughter plant, because the line speeds are so fast.

CURWOOD: So Michael, just how quickly do these slaughterhouses, these slaughter and packing plants work?

POLLAN: Well, in the case of chickens, it's 175 birds per minute. Okay, flying by you on a line, they hang them from a conveyor, there's a knife that cuts their necks. And then the workers are opening them up, you know, de-gutting them and cutting them into parts. And the result is a very dangerous situation dangerous for the workers, formerly because they'd get cut a lot. And now because they get infected a lot. A slaughterhouse, you know, has thousands of workers, they're working shoulder to shoulder on production lines. The meat or the carcasses are coming so fast, they say they can't even pause to cover a cough without the carcasses flying by them. They can't get permission to go to the bathroom without whispering directly into the ear of a supervisor. So it's a very intimate place. Add to that the fact that a very high percentage of these workers are undocumented immigrants who have no health care, who have no sick pay, and indeed they're being forced to work even when they're sick. The meat system right now is is really one of the hot zones for this whole outbreak. There are thousands of meat workers all across the country now who are infected. Last count I saw about 20 had died in this industry. And they have no choice but to return to work every day.

CURWOOD: So, Michael, I have to ask you this. So the dollar cost at the checkout counter is low for this kind of food. But what's the real cost as a society we're paying with the health impacts of such a high meat diet?

POLLAN: Well, you know, this is a dimension of the pandemic and the food story that I don't think is getting nearly enough attention. We have learned that certain underlying conditions predispose people to severe cases of COVID. And the most important appears to be right now high blood pressure hypertension. 59% of the serious cases have an underlying hypertension. The other conditions are obesity and Type Two Diabetes. Now all three of these, I mean, let's connect the dots here. These are chronic diseases linked to a bad diet, to a diet of fast food, lots of meat, lots of sugar, essentially processed food. We may be eating precisely the wrong diet as a nation to withstand this pandemic. So, you know, I think it's yet another argument for, you know, changing our diet, that the way we eat, we know that the American way of eating is killing us, usually quite slowly. Here is a case where it may be killing us a lot more quickly.

Tomatoes for sale at a farmers’ market in Bloomington, Illinois. Pollan advocates for the local food system. (Photo: Gemma Billings, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So it's very likely that this is a major historical inflection point that we're living in right now. Something like the Great Depression. What do you think the COVID-19 disaster pandemic will do for how we handle our food supply and related health concerns going forward once the dust settles?

POLLAN: Well, you know, in my more pessimistic moments, I think we'll try to get back to what we call normal and put this behind us and not make the kind of changes we need to make. But in fact, this pandemic has exposed enormous vulnerabilities in our economy in our society. And in our food system. It's very easy to imagine a leader, a party, creating building a new politics, around the common theme of addressing the problems that the pandemic exposed. One, of course, is the so called essential worker, a term you never used to hear before. And there is this paradox that we've learned that these essential workers are the most mistreated and lowest paid. And there's something very wrong with this picture. And one thing that should come out of this and I hope will is addressing the inequities of the people we depend on most are the people that get the lowest salary and are treated the most abusively in the workplace. In food, it would mean I think decentralizing, de-industrializing the food system to the extent that we can. We tolerated the concentration of the meat industry and other parts of the food industry, because it promised lower prices to consumers. And it did deliver that. But if you think about the cost now, in terms of the fragility, the brittleness of the food system, it was too high a price to pay.

CURWOOD: Michael, what's the role of local agriculture in this and this phenomenon of community supported agriculture, the CSA is that seems to be growing.

Michael Pollan an author, journalist, Professor of Journailsm at UC Berkeley and the Lewis K. Chan Arts Lecturer and Professor of Practice of Non-Fiction at Harvard University. (Photo: Alia Malley)

POLLAN: You know, we described these two food systems we have but of course, then there's yet another which is the local organic, you know, regional food system. And it's been very interesting to watch how that has adjusted. It is turned out to be more adaptable. Farmers that were selling to restaurants for example, many of them are starting CSAs, these box schemes where you get a weekly box of produce and pick it up at a location. This marketplace is thriving right now. And these are smaller farms that can make adjustments and seek new markets. To give you an example here in my community, there was a local restaurant that has been an institution here for almost 50 years, closed down on March 15, when we were sheltered in place, and there were two or three farms that really depended on this restaurant for their support. They provided most of the produce. They set up a CSA, and every week now on Sunday, I go to this restaurant and receive a box of produce that they've put together from these farmers and this is keeping the farmers going. And it gives me a chance to see my neighbors and the people who worked in this restaurant, you know, at a distance behind masks, but it feels great to shop that way and you're supporting the restaurant. You're supporting the farmers and you're supporting yourself with some of the the best produce you can possibly buy. And I don't know about where you are. But here the farmers markets, you know, have adapted, they all have touchless payment now and they meter the number of people coming in. And they seem to be doing very well also. So we haven't completely lost the old, redundant local food system. In meat, we almost have, there's very little of that left. But in produce, it still exists. And I think if there's a lesson to take away from this, it is that in the same way, we realize it's a huge mistake to have a country that can't produce its own surgical masks and depends on China for that and various other products, including drugs of all kinds. It's a huge mistake to put all our eggs in one industrial basket, and that there has never been a more eloquent case for diversifying the food chain for having many different ways to get ourselves fed, not just this supermarket food chain and just support local agriculture as a matter of national security.

CURWOOD: Michael Pollan is a best selling author, journalist and activist based at the University of California Berkeley. Michael, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

POLLAN: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- Living on Earth’s coverage of Michael Pollan’s Book The Botany of Desire

- Living on Earth’s coverage of Michael Pollan’s Book In Defense of Food

[MUSIC: Roy Hargrove, Christian McBride, Stephen Scott ”Laird Baird” on Parker’s Mood, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: We’re indoors a lot these days. And if you would like to hear how to improve indoor air quality and thus improve well-being. Join us next Tuesday evening at 6:30 Eastern for a live streamed event with renowned Harvard public health expert, Joe Allen. He’ll be talking about his new book Healthy Buildings, and taking your questions. That’s May 12th at 6:30 Eastern. And for details click on events at loe.org.

CURWOOD: Coming up – how a single determined individual changed the course of climate change history with a case at the Supreme Court. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Cheven and Warren Byrd, “Let Us Break Bread Together” on Let Us Break Bread Together, traditional African-American, CD Baby]

Beyond the Headlines

After working as an EPA Administrator under the Trump Administration, Scott Pruitt joined the coal industry as a lobbyist. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with environmental health news that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And Peter is going to give us an update on what's going on beyond the headlines. Right, Peter, what do you got for us today?

DYKSTRA: That's right, Steve. I want to talk a little bit about something I was a little concerned about. Andrew Wheeler, the EPA Administrator, of course, was a coal lobbyists before he was in charge of environmental protection. A little concern that the coal lobby was short of personnel when Mr. Wheeler left but for the coal industry, there's good news. They lost Andrew Wheeler as a lobbyist, but they gained the guy he replaced at EPA back in 2018 Scott Pruitt. Who's now a lobbyist for Hallador, an Indiana based coal company Pruitt lobbies against the closure of Indiana power plants that are among the biggest customers for Hallador’s coal.

CURWOOD: Now, the tough times is everywhere in the economy, including the fossil fuel industry, to what extent are they getting help by the Trump administration?

DYKSTRA: There's immense help all around. Trump has made it clear that it's a priority to try and rescue the coal industry. He famously appeared during the campaign in West Virginia, while his supporters held up placards that said, Trump digs coal. And oil firms, mining firms and coal companies are receiving aid from the administration and from the payroll protection plan. In addition to Hallador which got 10 million, that's where Scott Pruitt works. There's a company called Rhino Resources. Their former CEO is now Trump's mind safety boss and Ramaco Resources got 8.4 million its CEO is on Trump's coal council. Oil companies, mining companies are all in on it, despite the fact that their troubles have very little to do with Coronavirus.

The United States company Hallador Coal received money from the federal stimulus package. Former EPA administrator Scott Pruitt works as a lobbyist for Hallador Coal. (Photo: Sicko Atzen Van Dijk, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I mean, how come they're getting this money in the middle of the pandemic?

DYKSTRA: It's hard to say. But E&E News reported that at least two clean energy companies, a wind energy manufacturer called Broad Wind got 9.5 million. And then an electric vehicle company called Workhorse got 1.4 million.

CURWOOD: And even the big companies are in trouble. Peter, right. I mean, I think there's some significant losses being posted.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the big oil companies have been running flat. Exxon actually declared its first quarterly loss since 1988. But here's one that really kind of stunned me. We remember that Chesapeake Energy was kind of the Standard Oil of the fracking business 10 years ago, they were thriving they are considering, according to Reuters, declaring bankruptcy, business has been so slow.

CURWOOD: Things are changing. Let's take a look back now at the history vault, what do you see?

DYKSTRA: I'm going to go back to 200 years May 11, 1820 the Brig HMS Beagle was launched in London. It's a Royal Navy ship designed to conduct research missions. In 1831, there was a 22 year old naturalist named Charles Darwin, who was on board. This is the trip that Darwin made to among other places, the Galapagos. And it was the basis of his writing on the origin of species a cornerstone of evolutionary science.

The HMS Beagle was launched in 1820 from Britain but its most famous expedition was between 1831-1836 when Charles Darwin sailed around the world aboard the ship. (Photo: Hugh Llewelyn, Flickr, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0 )

CURWOOD: Anything else, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, I want to give a quick congratulations to the Washington Post. A team of reporters there won a Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism for their series Beyond the Limit on Climate Change.

CURWOOD: Well, you know, me, Peter, there's no bigger story than the question of having a stable or unstable climate.

DYKSTRA: Me too, I guess that's why we're talking about these things.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We will talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay. Steve, thanks a lot, talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more of these stories on the living on earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- E&E News | “Coal company with Pruitt ties among loan recipients”

- The Guardian | “Fossil fuel firms linked to Trump get millions in coronavirus small business aid”

- Stateimpact Pennsylvania | “Report: Chesapeake Energy plans to file for bankruptcy”

- Learn More About the HMS Beagle

- The Washington Post | “Read the Washington Post stories that won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize”

[MUSIC: Emory Joseph, “New Speedway Boogie” on Fennario – Songs By Jerry Garcia & Robert Hunter, by Robert Hunter & Jerry Garcia, Capsaicin Music/Iris Records]

The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court

“The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court” gives a behind-the-scenes look at the innerworkings of the highest court in the land. (Image: Courtesy of Harvard University Press)

CURWOOD: One determined person can sometimes change the course of history, and that’s happened when one lawyer sparked the case that led the US Supreme Court to hold the federal government accountable for climate change. The high court ruling in 2007 in Massachusetts versus EPA functionally compelled the government to regulate carbon dioxide as a pollutant. Thirteen years after that court order the federal government has yet to reign in greenhouse gases enough to prevent climate catastrophe, just as racial disparities still persist after the famous 1954 Brown versus Board of Education decision that outlawed racial segregation in public schools. But just as blatant racial discrimination is illegal today so are any government moves that blatantly and unnecessarily disrupt the climate. In his new book, The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court, Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus tells the gripping story of how against the odds one lawyer built the case and another argued it in the face of strong pushback from big environmental organizations. Author Richard Lazarus has himself argued 14 times before the Supreme Court and joins me now to tell the story of Massachusetts v EPA. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

LAZARUS: Yeah, delighted to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So this book begins almost like a detective novel: one guy in a little office, almost seems like he's got a bare lightbulb hanging over him and it's a question of making rent, the genesis of this case. Tell me how this gets started.

LAZARUS: It's basically right. The first chapter of the book is titled "Joe". And that's because the genesis of this case, which would never have happened without him, was a guy named Joe Mendelson. Joe Mendelson goes to law school in the fall of 1988. And Joe is what I like to refer to as part of the second generation of environmental lawyers. Those like myself were more of the first generation. We went to law school in the 1970s, we practiced in the 1980s. And it was all about air pollution, water pollution, hazardous waste pollution. Joe Mendelson goes to law school in the fall of 1988. And that is just a few months after Dr. James Hansen did his famous testimony before Congress where he said, the greenhouse effect is here. Global warming is happening now. It was on the front page of the New York Times. So he graduates in 1991. And Joe has every reason to think, not long after that, that actually the federal government finally is going to step up to the plate, because the President of the United States is Bill Clinton. The Vice President of the United States is Al Gore. And Al Gore had literally written the book on climate change. In June 1992, he published "Earth in the Balance", where he said, this is an issue unlike any other. The climate change issue is an existential threat. It threatens humankind with potential catastrophe. We can't compromise on this issue, I will not compromise on this issue, because you can't play politics with climate change. So people like Joe had reason to think, all right, they're going to do it. But the Clinton Administration goes from the first term, '92 to '96. And goes to the second term, heading into '98;Joe's getting mad. Joe is getting frustrated, because the science is becoming clearer and clearer. And the administration isn't doing anything. It's doing lots of things on environmental issues, a lot of very good things. They're not addressing the climate issue.

The United States Supreme Court accepts only about 80 or so of the approximately 7,000-8,000 cases it is asked to review each year. (Photo: Kjetil Ree, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Why do you think nothing happened on climate, essentially, when there was so much promise with Vice President Al Gore and his call to address the matter of climate disruption?

LAZARUS: I think he succumbed to what he, the very thing he said he wouldn't do, was play politics with it. What Al Gore wanted to do was become President of the United States in 2000. He was worried that it would affect his ability to maybe get the nomination and certainly win the general election. So he shied away from it. And most of the environmental groups, all the big national environmental groups, they basically had agreed to basically stand down. They didn't want to criticize the Clinton Administration, they didn't want to criticize Al Gore. And this one guy, Joe Mendelson, he worked for a group called the Center for Technology Assessment, about five employees on Capitol Hill. At one point they were in sort of, you know, a residential place with bedrooms and closets. They got kicked out because they were violating local zoning ordinances. They lived paycheck to paycheck when they got any paycheck at all. And Joe just got fed up, and he said, "Now, you guys are saying, 'Don't rock the boat, don't challenge them on this.'" He said, "I don't work for you and your fancy big organizations with all your resources, your fancy offices in Washington, DC and New York and San Francisco. You're not my boss." So in 1998, he literally stayed up late at night, day after day, and he drafted this petition to EPA, giving the argument for why greenhouse gases were air pollutants and why EPA needed to act on it. And then he sat on it a year, he was under enormous pressure not to file it. He sat on it a year and then in 1999 he just couldn't take it anymore. And he said all right, I'm filing this thing. He literally walked from Capitol Hill, where his offices were; he walked down to EPA, and for good measure, he sent a copy of it to Al Gore in the White House.

CURWOOD: There you go. Hey, before you, you go on with the story, Professor, give us a little bit of a law lesson. Why are we talking about a petition here? Why is this not a lawsuit?

LAZARUS: Yeah, Joe needed first to go to EPA, file what's called an administrative petition. That's a petition which gets filed with the agency in the first instance. So he filed an administrative petition with them in 1999. He said, Look, this is easy. Under the Clean Air Act, you have authority over air pollutants, and air pollutants are defined to be, a chemical compound emitted into the ambient air. Well, you know, it's not much doubt: carbon dioxide, methane, they are chemical compounds. Are they emitted into the air? You bet. No one could dispute that. Then the second issue is whether or not the emissions of that air pollutant can be reasonably be anticipated by the administrator to endanger public health and welfare, in this case emissions from motor vehicles. He said, Well, that's obvious too. There's all this science, which had been building up in the 1990s. EPA has sort of acknowledged it. So you have an obligation under the statute to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from motor vehicles. That's what his petition said. He filed it during the Clinton administration in 1999. He knew they wouldn't do much with it at that point, because he figured, I'm really laying this on the plate of the next administration, to be elected a year later. And he's pretty confident who that was going to be: Al Gore. And then to his surprise, and everyone, a lot of people's surprise, it wasn't Al Gore. It was George Bush. And the new administrator of EPA actually wanted to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. That was Christine Todd Whitman. And people always forget, George Bush was the one who campaigned in 2000 to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, address climate change. It wasn't Al Gore who did it, it was George Bush.

CURWOOD: Yeah, he promises late in the campaign, what is it, like October or so, he says he's going to deal with this. And he hires Christine Todd Whitman on the basis that this is going to go forward.

The Environmental Protection Agency is headquartered in the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Moreau1, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

LAZARUS: Right. And she basically interviewed for the job and took the job, because she was a climate hawk. And this was going to be her big signature accomplishment at EPA. And interestingly, she wasn't alone in the Cabinet. She had Colin Powell, Secretary of State, he was a climate hawk, he believed it was very important to adress this issue for national security. Condoleezza Rice, the National Security Advisor, was also a climate hawk. And finally, Paul O'Neill, Secretary of Treasury. But what happened is the energy industry caught wind of this. They heard that Christine Todd Whitman was planning to act aggressively on this. They contacted Dick Cheney, and they said, Look, the moment of truth has arrived. Is this a continuation of the eco-radical policies of the Clinton and Gore administration, or is this a business friendly administration? So Vice President Cheney took up their cause, and he went to the White House. He persuaded Bush to renege on his campaign promise to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. And then he made a really stupid decision.

CURWOOD: And that was?

LAZARUS: He had Bush write a letter to Congress. The President didn't just say that greenhouse gases shouldn't be regulated as a matter of policy. He said the federal government "lacks the authority to do it" under the Clean Air Act. And in making that move, without ever talking to the EPA lawyers, without ever talking to any of the political appointees at EPA, Vice President Cheney had Bush answer a question of law. But that was a mistake, because at the end of the day, the President of the United States doesn't have the last word on the question of law. The courts have the last word on the question of law.

CURWOOD: But because of this letter, the Bush administration's lawyers were compelled to argue that in fact, this was the law.

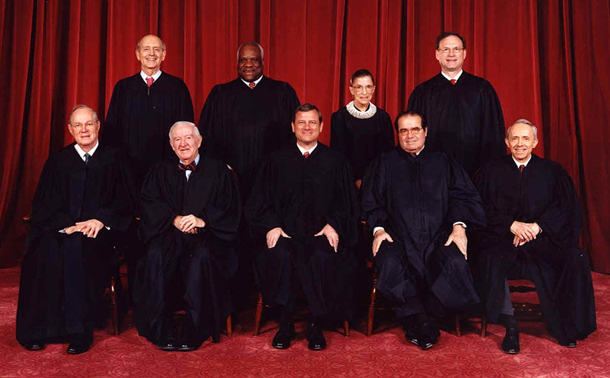

The nine Justices of the United States Supreme Court in 2006. Top row (left to right): Associate Justice Stephen G. Breyer, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Associate Justice Samuel A. Alito. Bottom row (left to right): Associate Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, Associate Justice John Paul Stevens, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Associate Justice Antonin G. Scalia, and Associate Justice David H. Souter. (Photo: Steve Petteway, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

LAZARUS: That's right. Once the President of the United States had announced the decision. He is the commander in chief, he's the chief executive. EPA had no choice but to follow it. And the way they decided to follow it was actually to deny Joe's petition. So they denied Joe's petition in August 2003. They announced that greenhouse gases are not air pollutants, and when they denied the petition, that's when Joe had the right to sue. Because they made a final decision at that point. They overrode the advice of the career people at EPA who said, just sit on it, don't do anything with this. And they said, No, we're gonna formalize it. We're gonna win in the courts. So they triggered a lawsuit. And, the environmental groups were all in.

CURWOOD: What was the actual case that Massachusetts petitioners were making?

LAZARUS: Yeah, so the actual argument they made was sort of three things. And these are the three issues that hit the United States Supreme Court. To bring a case in federal court, you have to have what is called Article III standing. And to have standing, you have to show you have injury, you have to have concrete, imminent injury. So the first thing they argued was, the injury from climate change satisfies the constitutional standard for standing. That was the ground on which the environmental groups and the states could not afford to lose. And that was why many people who believe strongly in climate change, were so worried about the Supreme Court case here. Because if they lost on that threshold issue, and the court said, this is just too different. It's so removed out in time and space over hundreds of years and thousands of miles, it doesn't fit the court's test for injury. If the court had ruled that, it would have been game over for all climate change cases in the federal court. So the first thing they argued was, the injury from climate change satisfies the constitutional standard for standing. The second thing they argued was that greenhouse gases are air pollutants, within the meaning of the statute. The first issue of standing is a question of constitutional law. The second issue is a question of how you read the federal statute. Then the third argument they made was that EPA, in not deciding yet, whether greenhouse gas emissions from automobiles endanger public health and welfare, had abused its discretion. They were required now to actually at least make that endangerment determination, or decide whether to make that endangerment determination. So those were the issues in front of the court. They lost in the lower court and the DC circuit. And that's what, those are three issues they successfully brought to the United States Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court of the United States is conducting its business remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic and hearing oral arguments by phone this May. (Photo: Phil Roeder, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Richard, to what extent did the real politic of this, that is, the concern about climate disruption and what was being said and written in this period of time, put a bit of the wind at the back of these petitioners?

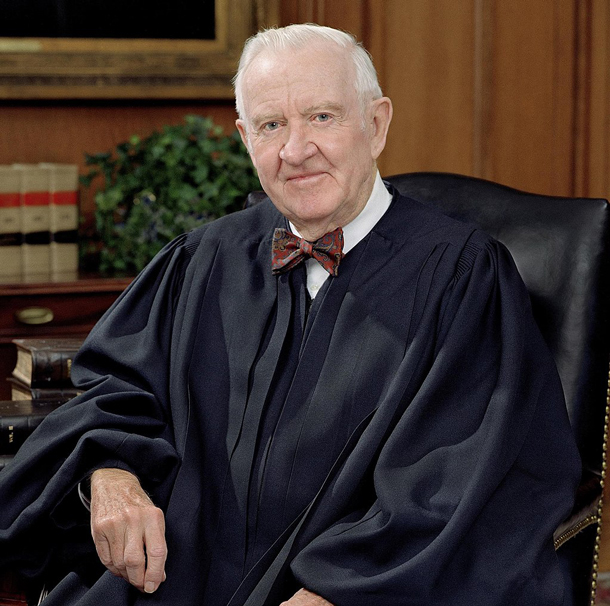

LAZARUS: Yeah, I think it undoubtedly did put a bit of wind, as science became clear. I talked to Justice John Paul Stevens. Justice John Paul Stevens, I refer to him as "the Jedi Master". He's the one who wrote the opinion for the United States Supreme Court and did an incredible job of sort of helping to keep that five justice majority. And what Justice Stevens told me, and this is part of the reason he wanted to write the opinion himself in the case, was he was frustrated. He was frustrated with the fact that so many people, including Republicans, and he was Republican, were not taking the climate change issue seriously, the global warming issue. And he thought that was a mistake. And he wanted this case and the way he wrote the opinion to be a wakeup call. What he told me was, he said, sometimes he writes opinions which are just to other lawyers, and the lawyers in the case. But other times he wrote opinions to the general public, and to policymakers. And this one, he's writing to the general public. So if you read his first few paragraphs of his opinion, it's all about climate change. It's all about the threat of climate change. And he even says who the respected scientists are. He said, the respected scientists are the ones who believe this is a real threat and that humankind is causing it. What's fascinating though, is you look to the parties and the environmental groups in this case -- in seeking Supreme Court review, and then how they pitched the case to the justices, they deliberately did not make it all about climate. They downplayed the climate dimension of the case. And that's because they were lawyers, and they were really good lawyers. And they understood the best environmental lawyers are not the best environmentalist. The best environmental lawyers are the best lawyers. They had to convince five Justices on the Supreme Court. And actually, the Justices, even the liberals, it's not as though environmental issues are their first order. There were no Justice William Douglasses on the Court, back then or even now. There are those who are more sympathetic or less sympathetic. So what they did to get the Court to take the case is they made it a question of administrative law and remedial law. They understood that maybe environmentalists, what makes their heart go pitter-patter and excites them to great passion, is like, climate change. What excites Justices and makes their heart go pitter-patter is administrative law.

Jim Milkey, who presented the oral argument in front of the US Supreme Court for Massachusetts v. EPA, is now an Associate Justice of the Massachusetts Appeals Court. (Photo: State of Massachusetts official photo)

CURWOOD: I’m speaking with Harvard Law professor Richard Lazarus about his new book, The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court. We’ll be back right after the break with how the petitioners fought and won the landmark Massachusetts versus EPA case. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Epic Brass, “Chevy Chase” on Star Spangled Pops!, by J. “Eubie” Blake, Ars Nova Digital]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gregg Stafford & Dr. Michael White, “Bye & Bye/Saints” on New Orleans, Putumayo World Music]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We continue our conversation now with Harvard Law Professor Richard Lazarus, whose new book, The Rule of Five, chronicles the harrowing journey of one of the most important environmental cases to be heard before the US Supreme Court.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the reasons that your book is so compelling is that we really get to know the people involved in this case. People like Jim Milkey --

LAZARUS: Right.

CURWOOD: Who ultimately presented the oral argument in front of the United States Supreme Court. Tell me who he was and why he was so invested in this case.

LAZARUS: Yeah, so Jim Milkey is a career attorney in the Massachusetts Attorney General's office. He went to undergraduate here at Harvard College; he went to law school at Harvard Law School. You know, many of the Harvard-Harvard types, they go off and they decide to make some money in the private sector. Jim Milkey didn't do that. He went to the Massachusetts Attorney General's office. He was a career attorney in the environmental division and Jim, to some extent, is like Joe Mendelson. In the early 2000s, he becomes increasingly concerned about the climate issue. And he starts looking for a case that he thinks he and Massachusetts can make a mark. And after they deny Joe Mendelson's petition, he basically links arms with Joe Mendelson, 11 other states, and several dozen environmental groups. But Milkey does more than that. Milkey wants Massachusetts to take the lead in this case. He basically maneuvers in a very clever way for Massachusetts to be the lead. And that's why the case is called Massachusetts versus EPA. So he played an important role there early on. But there are really two instances in this case that Jim Milkey played absolutely critical roles.

CURWOOD: Okay, and those are?

LAZARUS: First, he was the only person, really, who thought they should seek further review if they lost in the US Court of Appeals for the DC circuit. Everyone else thought, "don't do it. Let's not do that. It's too risky. We could lose everything. You know, we didn't lose so much so far. Let's just wait for another case." Jim Milkey said, "No, I think this is a good case. I'm willing to roll the dice," under enormous pressure not to do that.

CURWOOD: And before you give us the second, remind us why the case was at the Court of Appeals.

LAZARUS: Right. Basically, after EPA denied Joe Mendelson's petition, the way the Clean Air Act operates, when you challenge the EPA's decision, there's only one court you can bring your challenge. And that's the US Court of Appeals in Washington, DC. They're experts in administrative law. They do a lot of reviews of federal agency action.

Associate Justice John Paul Stevens wrote the majority opinion in Massachusetts v. EPA. (Photo: Steve Petteway, Photographer for the US Supreme Court, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: And in fact, he loses there.

LAZARUS: He loses there, in a very odd opinion, where two judges rule that EPA is right, but they actually can't agree on a rationale. Judge David Tatel is the one judge among the three judges who hear the case who believes that they're right, and he writes a blistering dissent. I spoke with David Tatel at length in his office about this. He felt very strongly about the case. The son of a physicist, someone who actually equated addressing the climate issue with civil rights concerns: underrepresented, future generations, whose lives and livelihoods are at risk; Tatel, before he went on the bench was a civil rights lawyer himself. He went to his clerk, after he learned the vote was two to one, he'd be in dissent, and he said to his clerk: "Make it long". He wanted to anything he could to make it possible the Supreme Court might hear this case. He wrote 50 drafts of his dissent with his law clerk before they published it.

In his dissenting opinion, the late Associate Justice Antonin Scalia argued that the Massachusetts v. EPA petitioners lacked Article III standing. (Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Let's go back for a moment to Jim Milkey's situation. You gave us one instance, and the other?

LAZARUS: The other is that when the case was before the United States Supreme Court, Jim Milkey presented the oral argument, for all the groups. In the US Supreme Court, the Justices only let one person argue per side. There were, you know, about 35, 36 or more petitioners on the same side. But the Supreme Court says, we don't care. You have to have one person present your argument. There is a battle, and a battle royale, about who should argue the case. Everyone always agrees on the easy thing: we should have the best person argue the case. And then, they tend to disagree about who the best person is. Jim Milkey prevailed in this case. And Jim Milkey really did present one of the single best oral arguments I have ever heard in the United States Supreme Court. And I could certainly tell you that a lot of people thought he wouldn't do that before he stood up there. But that day he was on all cylinders.

CURWOOD: Were you there that day?

LAZARUS: I actually was there that day. When you go to a Supreme Court argument, you're on pins and needles, because you know how much somebody's prepared. You know what the weaknesses of a case are, you know what the strengths are. But you're waiting to find out, what do the Justices think? And when the Justices get together for oral argument, for that one hour, which is the amount of time they devote to an oral argument in any one case, 30 minutes each side, it is the very first time the Justices learn what their colleagues think about a case. They have a tradition of not talking about the case and their views of the case before the oral argument. So two things are happening when the Justices start asking questions. One is the advocates, the lawyers like Jim Milkey, who are presenting the argument, they learn for the first time hints about what the Justices think. Second, the Justices learn what their colleagues think. So what you see during the oral argument is as much a debate and discussion between the Justices as anything else. The Justices don't address each other directly, they ask questions through the lawyer, but everyone knows what's happening. In the Massachusetts case, Jim Milkey's petitioner, he stands up there first. The beginning argument, it's no surprise, Justice Antonin Scalia is all over him. A master of oral argument, a master of destroying a party to whose position he's opposed. And a champion of Article III standing, someone who'd written that environmental groups should not have Article III standing to bring cases, generally in many instances. And Scalia was all over him. He asked about 23 questions.

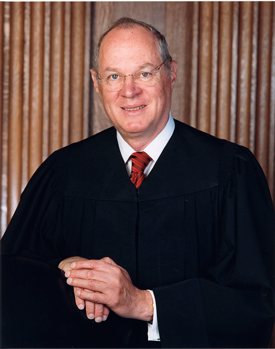

Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy saw the 1915 case Georgia V. Tennessee Copper as a key precedent for establishing that the petitioners did have Article III standing. (Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: In the course of?

LAZARUS: Oh, in the first 18 minutes. He asked him question after question, and he didn't even get to the second issue until after 18 minutes. That first 18 minutes is Scalia, again and again. And Scalia was the master of oral argument, of taking your answer, mocking it, trying to find some weakness, whether it was there or not. And basically unraveling you before the court. What was amazing, was Milkey never took the bait. He's being pummeled by Justice Scalia, and he answers every single question, over and over again, directly, candidly, convincingly; I mean, he really disarms Justice Scalia. You didn't see that happen very often. But even when that first 18 minutes is happening, as significant as it was, it's when Justice Kennedy asked a question, towards the end of that discussion, because when Justice Kennedy asked a question, everyone in that courtroom, including myself, we leaned forward. Because we were about to find out what Justice Kennedy thought. Kennedy spoke, and Kennedy asked Jim Milkey, he said, "Well, what's your best case, Counsel, for the argument that a state like Massachusetts has sort of some special right to have standing here, given the injury to the state from climate change?" And Jim Milkey gave an answer; it wasn't a sort of first-order answer. And Justice Kennedy cut him off. He said, "Well, Counsel, isn't your best case Georgia v. Tennessee Copper?" Well, that was a case decided at the very beginning of the 20th century. It was a case which had not been in any of the about 42 briefs filed in the case. No one had identified that case. When Justice Kennedy said that, everyone thought, Justice Kennedy did his own research. Justice Kennedy thinks this case helps Massachusetts. Jim Milkey thought to himself, if Georgia v. Tennessee Copper is good enough for Justice Kennedy, it's good enough for me. And, in the audience, we all basically thought to ourselves, five. The fifth vote was there. To win in the United States Supreme Court and why the name of my book is The Rule of Five, it takes five votes. And when Justice Kennedy said that, we were pretty confident we had five, at least on the standing issue. And that was the issue one could not afford to lose on. That was a big moment in the courtroom.

CURWOOD: So there's this successful argument. What happens after the argument?

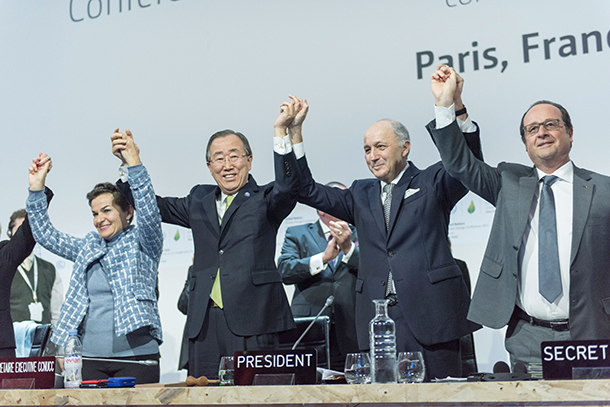

The leaders of the Paris Agreement celebrate its adoption at COP21 in December 2015. From left: Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Christiana Figueres; Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon; President of COP21 Laurent Fabius; and French President François Hollande. (Photo: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

LAZARUS: Well, when the argument ends, the Chief Justice bangs the gavel and says, "The case is submitted." The advocates get up and they leave. But that's when the action shifts, from one side of the lectern, where the lawyers stand to argue, to the other side of the lectern, where the Justices sit. The Justices stand up, they leave the courtroom. And then two days later -- this time it was Friday morning, December 1 -- they meet. They meet in conference to basically decide the case. And they went around the room, each one voting one at a time, and the vote was five to four, with Justice Kennedy supplying the fifth vote. But what most people don't realize is that's a tentative vote. There's nothing permanent about that. Justices change their mind all their time. Justice Kennedy was known to change his mind, and he'd been known to change his mind in big civil rights cases and in environmental cases. So what happens is, it's a tentative vote, and the person writing the opinion for the majority, in this case it was John Paul Stevens, he has to write an opinion that Kennedy agrees to join. And until five Justices join that opinion, it's not an opinion of the court. And Justice Stevens here, who assigned himself the opinion, knows he's not the only one trying to get Kennedy's vote. Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Roberts, they're writing dissenting opinions, and they're going to try to coax Kennedy back to their side, and turn their dissents into majorities. So Justice Stevens, he could have said, I'm gonna assign the opinion to Justice Kennedy. If he does that, the odds are very high Justice Kennedy will stick with that side. But the downside is he might write a very narrow opinion, which doesn't do very much. Justice Stevens wanted to write a sweeping opinion. So he had to write in a way which didn't lose his vote. And it took him a lot of drafts, took him eight drafts to do that. He did his first draft, and he didn't, he had four votes, including himself, he didn't have five. He did his second draft, he had four votes. His third draft, four votes. He's starting to have to make some compromises, that's what you need to do. It's not until sort of mid to late March, that Justice Stevens produced his eighth draft. And Justice Kennedy joins it. Bingo. That's opinion of the court.

CURWOOD: And by the way, you write in this that, in more modern times, Chief Justice Roberts was not in favor of upholding what we call Obamacare, the Affordable Care Act. And in that initial conference said no, but then changed his mind.

The American democratic system relies not only on the votes of a majority of the Supreme Court Justices, but ultimately on the votes of individual citizens. (Photo: Theresa Thompson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LAZARUS: Yeah, actually, I don't know that personally, myself, unlike like a lot of things I know about Massachusetts v. EPA, but that's what people have found out in talking to law clerks and the Justices. So I'm taking that at face value. That's a good example though. It's a good example of how you vote one way at conference, and then you change your mind. There's a discipline to writing, which makes people think about things in a deeper, more rigorous way. And so it's not surprisingly, the Justices change their mind. Sometimes they find, something that seemed intuitively clear, when you actually have to deal in writing with the legal issues, you change your mind. That's a good thing. We want our Justices to be thinking hard about issues. You know, we want them to not just think, Well, what do I think my intuition tells me. They're writing an opinion for the court, which is going to have to, you know, pass the test of time. But there's a risk involved. And Justice Stevens knew he had to write an opinion. And it would only become law and opinion of the court, if he could convince four Justices to join him. And he did that successfully, which is why I call him the Jedi Master.

CURWOOD: So how big a case was this? How does this compare, say, in scope and import to Brown versus the Board of Education, for example?

LAZARUS: Well, in the first instance, there's no Supreme Court case as important as Brown v Board of Education. I mean, that is, by every possible measure, the most significant decision the United States Supreme Court has ever rendered. But in the world of environmental law, this is our Brown v Board of Education. This is by far the most important decision the court has ever ruled on, because of the topic, which is climate change, the most important pressing issue of our time, and because of the practical import of the ruling, and that is it formed the legal basis of everything the Obama administration did for eight years, every single one of the significant greenhouse gas initiatives of the Obama administration made possible because of Massachusetts v. EPA, and in turn, the Paris Climate Agreement only happened because of everything that Obama did and his EPA did during those eight years.

“The Rule of Five” author Richard Lazarus is a Professor at Harvard Law School and has presented oral argument before the Supreme Court in 14 cases. (Photo: Courtesy of Harvard University Press)

CURWOOD: So this case did allow, of course, EPA to find that carbon dioxide is an air pollutant, and a dangerous one, it's endangerment finding. But some might say, you know, even with this court decision, we're not making a lot of progress right now in terms of actively taking on the threat of climate disruption. Where do we go from here?

LAZARUS: Well, I think actually, that the Obama administration rules were making an enormous amount of progress. The methane rules; the motor vehicle rules; the waiver allowing California and a dozen other states to regulate greenhouse gas emissions more stringently; the Clean Power Plan, which was absolutely a brilliant, very measured and pragmatic plan, but would lead to sharp reductions in greenhouse gas emissions for the United States. And that's what allowed other countries of the world to finally say, all right, the United States is actually doing something about it. With that said, even when Obama did by himself, even the Paris Accord was not by itself going to eliminate the threat of climate change. That's, of course, what was so disturbing, unsettling about the presidential election of 2016, because so much of that effort is being threatened by the Trump administration. Now, I say "threatened": the current administration has not yet successfully unraveled what President Obama did, but they've threatened too. They've lost a lot of lawsuits in the past several years which have stalled their efforts. If President Trump loses the election in November of 2020, most everything the Obama administration did can be put back together again on climate. If on the other hand, the Trump administration gets another four years, that'll be harder. And that's why this election is so important. But it's also why it has another lesson in my book about Massachusetts v. EPA, and that is even big cases, even a big case like Massachusetts v. EPA, a big case like Brown v Board of Education, it can have much promise, it can allow things to happen that otherwise couldn't happen. But they're never the end game. It takes more than the votes even of five Justices to make transformative change to address a pressing issue, like climate change. Massachusetts v. EPA has great promise. It's allowed extraordinary laws to be enacted by the executive branch. But whether that promise is realized, will depend on the voters, and the elected officials who they choose.

CURWOOD: Harvard Law School Professor Richard Lazarus's new book is called The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court. Thank you so much, Richard, for taking the time with us and telling this story, which I have to recommend if folks want to read a good one, this is one. Thank you so much.

LAZARUS: Thanks, Steve. Always a delight.

Related links:

- About The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court

- Read the majority and dissenting opinions in Massachusetts v. EPA

- The Harvard Gazette |“How and why the Supreme Court made climate-change history”

- About author Richard Lazarus

- About Jim Milkey

[MUSIC: Epic Brass, “Chevy Chase” on Star Spangled Pops!, by J. “Eubie” Blake, Ars Nova Digital]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gregg Stafford & Dr. Michael White, “Bye & Bye/Saints” on New Orleans, Putumayo World Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth