June 19, 2020

Air Date: June 19, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Juneteenth and African Foodways

/ Ike SriskandarajahView the page for this story

African Americans celebrate their ancestors’ emancipation from slavery on June 19th, a holiday known as Juneteenth. On that day, families gather to picnic and cook out. The voyage from Africa isn’t often on people’s minds, but it is in their stomachs. Living on Earth’s Ike Sriskandarajah digs into the foodways that traveled the Atlantic. (07:26)

The Racial Gap of Pollution Responsibility

View the page for this story

Fine particle air pollution is especially dangerous for human health, and a well-established body of research has found that minority groups are disproportionately exposed. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences documents the racial gap between who’s most responsible for air pollution and who breathes it. Host Steve Curwood sits down with Dr. Christopher Tessum, lead author of the study. (06:18)

Redlined Real Estate & Extreme Urban Heat

View the page for this story

In the 1930s, while the world was digging out of the Great Depression, the US government came up with a plan to rate neighborhoods based on their presumed suitability to receive home loans. The neighborhoods that the government, and banks, considered riskiest were outlined in red. These “redlined” neighborhoods tended to be in city centers and home to black Americans. Today as climate change exacerbates urban heat, they’re experiencing much higher temperatures than surrounding areas. Vivek Shandas is a lead author of the research and speaks with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about the unequal impacts of racist ‘redlining’ practices. (10:35)

Why I Wear Jordans in the Great Outdoors

View the page for this story

Some stereotypes about who can be “outdoorsy” can leave people of color out, so environmental educator CJ Goulding actively and creatively works to encourage young people of color to feel that they belong in the outdoors, too. CJ Goulding speaks with Host Steve Curwood about how his Air Jordan “Bred' 11 sneakers help him link young people of color to the great outdoors. (06:33)

Farming While Black: A Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

View the page for this story

Soul Fire Farm in upstate New York is dedicated to not only growing food, but also cultivating environmental, racial and food justice. Its ten black, brown and Jewish farmers aim to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah Penniman is the co-founder of Soul Fire Farm and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss her book, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land, and her journey as a person of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world. (16:31)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: C.J. Goulding, Leah Penniman, Vivek Shandas

REPORTERS: Ike Sriskandarajah

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

We’re celebrating Juneteenth this week with stories of challenges and triumphs in the African American community, starting with farming.

PENNIMAN: Contrary to popular belief, black and brown folks do want to farm. And, this was something that just surprised me, cause I thought I was just a weirdo out here. I was going to start this farm with my family, grow food, you know, provide to those who need it the most in the community, and that was going to be it.

CURWOOD: Also, a look at the foods brought from Africa that slaves grew to feed themselves and much of America.

CARNEY: We think of plantations as places that produced export crops, but we don’t think about them as also places where human beings had to also know how to farm for their own nourishment.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Juneteenth and African Foodways

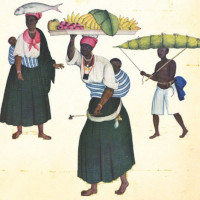

Judith Carney is the author of “In the Shadow Of Slavery: Africa's Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World.” (University of California Press)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

On the nineteenth of June in 1865 black slaves in Texas finally heard about the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, and started celebrating freedom with the holiday now called Juneteenth. Sadly, freedom for slaves in Texas was delayed for more than two years, much as delays for justice still persist today for black people in America. And Juneteenth is now officially observed by some 46 states, and African Americans typically celebrate with picnics and cookouts. Often overlooked at these gatherings is the role that Africans and slave ships played in bringing some of those foods to American tables. Today as Living of Earth celebrates Juneteenth we reprise a report from Ike Sriskandarajah about how culture and agriculture overlapped in that dark chapter of American history.

SRISKANDARAJAH: For 1,000 years before the Atlantic slave trade started, the origin of humanity was also its cornucopia. Many of the world’s staple foods first sprouted from African soil. They’re on your picnic table, from the sesame seeds on your bun to the Worcestershire sauce in your hamburger to your slice of watermelon. And if you reach into the cooler…

[COKE CAN OPENS]

CARNEY: The cola in cocoa cola is an African plant as well, the cola nut.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Judith Carney, is the author of In The Shadow of Slavery, Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. Her book traces the path of foods that traveled with slaves including an ingredient in the world’s most ubiquitous fizzy drink.

CARNEY: Cola came on slave ships - they used cola in the casks of water that were carried on the ships to refresh water that was going bad during the prolonged voyage.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So they were drinking coke 400 years ago on slave ships?

CARNEY: [LAUGHS] No, no, but, you need the coca part of it and the sugar I think. I would say it’s slightly more bitter than eating a potato raw.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Another of our favorite drinks, coffee, also comes out of Africa and millet, black-eyed peas. Judith Carney tracks the migration of these foods through historical records.

CARNEY: I went back and looked at the journals and the diaries. What did the ship captains, the “slavers”. How are they feeding people for six weeks to three months voyages?

SRISKANDARAJAH: One such log was written by a 17th century slave trader, moored off the coast of western Africa.

[OCEAN WAVES, SEAGULLS SQUAWKING]

MAN 1: A ship that takes in 500 slaves, must provide above a hundred thousand yams; which is very difficult, because it is hard to stow them, by reason they take up so much room; and yet no less ought to be provided, the slaves being of such constitution, that no other food will keep them; so that they sicken and die apace.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The slaver’s human cargo was valuable. So captains bought food the captured Africans could eat, and they bought enough of it. Sometimes the ships would even land in the New World with surplus.

CARNEY: And that I argue, the unwitting conveyance of bringing African food to the Americas was the slave ship.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Once in the Americas the slaves were scattered to work on plantation cash crops. But they were also expected to feed themselves.

CARNEY: We think of plantations as places that produced export crops, but we don’t think about them as also places where human beings had to also know how to farm for their own nourishment.

SRISKANDARAJAH: A Danish Traveler, Johan L. Carstens, wrote a diary describing his observations of the Americas during the early Eighteenth Century

Michael Twitty curated the African American Heritage Seed Collection.

[FIFE MUSIC]

MAN 2: These plantation slaves received nothing from their master in the way of food or clothing except only the small plot of land at the outermost extremity of his plantation land that he assigns to each slave.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The staples from Western Africa flourished in the South, and from those meager plots came a rich food tradition. It was good enough for slaves, it was even good enough for a founding father. Culinary historian Michael Twitty says that Thomas Jefferson actually bought food from his slaves.

TWITTY: Oh yeah, oh yeah. The day to day needs of his own kitchen table, much of that was supplied by the enslaved population of Monticello. There are extensive records of purchases for the main house from the enslaved community. He would buy cabbage, watermelon, he’d buy sprouts.

SRISKANDARAJAH: President Jefferson wasn’t alone.

TWITTY: Before the new immigrants come in at the turn of the 20th century, we are the ethnic restaurateurs of America.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And Twitty says that African Americans didn’t just add ingredients to America’s Melting Pot, they spiced it up too.

TWITTY: Oh yes, red pepper was the most important, ubiquitous spice.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So important, that in 1780, close to 100 slaves newly imported from West Africa, protested until plantation owner Josiah Collins supplied the spice.

TWITTY: Within a year of their arrival he has to order 1000 pepper pods to season their food because they will not eat bland food. They expressed to him that we want the pepper pods!

SRISKANDARAJAH: Hot sauce has been on most southern tables since. African American cuisine still has its roots in those peripheral plots but, but African Americans’ connection to the land has changed.

TWITTY: We were an agrarian people for millennia even through the period of slavery. We went from being 90 percent agrarian to 90 percent urban in less than a 100 years think about that.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Freedom wasn’t free, emancipation cost the slaves their link to the land. African Americans couldn’t own or lease land - their only option was punitive sharecropping.

TWITTY: All that oppression hurt us in the long run because it divorced us from the land, it divorced us from nature and through food we can reconnect with that and begin to repair that link.

SRISKANDARAJAH: That’s part of Michael Twitty’s mission, he works to bridge that gap. He’s put together the African American Heritage Seed Collection. It offers heirloom seeds to today’s gardeners.

TWITTY: To see an okra plant that you know was growing in gardens of people who worked in Mt. Vernon or Monticello, to see a kind of rice that was grown in 17th century South Carolina. It gives you the sense of such connection. Because I always tell people my own little corny saying, growing history is knowing history.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And knowing history can turn your bowl of gumbo into a portal back through time.

CURWOOD: Ike Sriskandarajah first prepared that report in 2010.

Related links:

- Michael Twitty's blog, Afroculinaria

- Judith Carney's book "In the Shadow of Slavery"

- Vox | "Juneteenth, explained"

[MUSIC: Louis Jordan, ''Juneteenth Jamboree'' on Decca – 7723]

The Racial Gap of Pollution Responsibility

Emissions rising from working factories. (Photo: Unsplash, Desmond Simon)

CURWOOD: Dirty air is common in the US and studies show that African American and LatinX communities are disproportionately affected, especially by particulate pollution, which has been linked to high corona virus death rates among people of color. And a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science documents the racial gap between who’s responsible for air pollution and who breathes it. Here to tell us more is Christopher Tessum, a research scientist at the University of Washington, and he joins us from Seattle. Welcome to Living on Earth!

TESSUM: Hello. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So talk to me, what kind of air pollution are we talking about? And why is it dangerous to public health?

TESSUM: In our study, we looked at fine particulate matter, or PM2.5. These are particles that are basically so small that you can't even see them. When there's a lot of PM2.5 pollution in the air, it will show up as kind of a haze. But otherwise, you can't see it at all. These particles are so small, they go all the way down into your lungs and get stuck in the very bottom. And then they cause inflammation, which can lead to problems with your heart problems, with your lungs, and eventually it can contribute to death.

CURWOOD: How important is the risk of air pollution for environmental health?

TESSUM: Ambient exposure, to PM2.5, just fine particulate matter is the largest environmental cause of pollution. Ambient air pollution causes about 4% of total deaths United States, which is more than three times the number caused by motor vehicle crashes.

CURWOOD: Your research added some statistical certainty that racial and ethnic minorities are acutely vulnerable to air pollution because of where they live. There's also an interesting element that you put in here, which is to look at who's responsible for those pollutants that are inhaled disproportionately by blacks and Hispanics, what made you consider the exposure here for this, and the responsibility by blacks and Hispanics, and what was your measurement for that responsibility?

TESSUM: One way of thinking about it is that there's these two kind of problems or issues in society that, you know, people spend a lot of time thinking about, talking about. One is inequity in income. And then there's kind of inequity, racial ethnic inequity and exposure to environmental burdens. So what we're trying to do is trying to look for a way to look at these two problems together, because they're really related. When you have somebody operating an electricity generator, they're not just operating it for fun, you know, and they're not just sending the pollution out of it for fun, they're doing that to meet an economic demand for electricity. We try to connect, you know, who's demanding products and services with who’s emitting the pollution and who's exposed to that pollution. And so in order to do that, we came up with a metric called pollution inequity, which basically is kind of the percent difference in between the amount of pollution and the amount of exposure to pollution that people are causing, through their activities, their daily activities, their consumption of goods and services, as we call it. So the percent difference in between that, and the amount of pollution that those people are being exposed to.

CURWOOD: So what exactly were your results; give me some numbers here, compare the responsibility versus the burden for pollution among blacks, Hispanics, and then whites.

TESSUM: So we find that blacks and Hispanics are bearing kind of on average, we call a pollution burden, which is that they're exposed to more pollution than they're causing. So we find that black people are exposed to about 56% more pollution than they cause. And Hispanic people are exposed to about 63% more pollution than they cause. Conversely, we find that white people and other races on average are exposed to about 70% less pollution than they cause.

CURWOOD: So 17% less pollution than generated by their own consumption, you're saying?

TESSUM: Yeah.

The “haze” that Dr. Tessum was referring to. (Photo: Unsplash, Anz Designs)

CURWOOD: Now, from your findings, what are the overall driving factors for the air pollution problems that create these particles? And how did you measure the pollution for the folks who are in your study?

TESSUM: One of the kind of tricky parts of all this is that there's not any kind of one or a couple of different things that are causing all this air pollution, it's really a lot of different things. So historically, things like coal power plants, and heavy duty trucks and light duty cars were kind of the, maybe the three dominating factors. But over time, there's been a lot of regulation in those sectors for the power plants and the cars and the trucks, so that now, you know, the pollution is less from those; hasn't necessarily been decreasing as much for some other sectors -- in agriculture, is a more important one over time; industrial sources, things like that.

CURWOOD: So many sources of air pollution have been decreasing along the years thanks to regulation, but the inequity of exposure seems to have remained the same. So why are blacks and Hispanics contributing less to pollution but still being affected more do you think?

TESSUM: What we saw in the study was that the amount of pollution per dollar spent was getting less over time. But the thing is that black and Hispanic people are still living in places that had higher pollution levels, and white people and other races are still spending more money on average. So the underlying factors that were contributing to the inequity are staying the same, it's just that kind of pollution intensity of the economic activity has decreased over time.

CURWOOD: So when you look at an urban area, what do you see in terms of this racial disparity in terms of exposure to pollution?

TESSUM: There's kind of this long history of why people live in certain neighborhoods in the US, you know, and why certain racial ethnic groups tend to live in certain neighborhoods that may be nearer to highways, things like that, within a certain city. And different racial ethnic groups tend to live in different neighborhoods. It turns out that the neighborhoods that black and Hispanic people live in tend to have higher concentrations of PM2.5.

CURWOOD: So what's next for you for research?

TESSUM: Yeah, so there are a couple of things that we kind of ran into while we were doing this study that we would be interested in exploring a little bit more. One is looking at how this type of story plays out on a global scale, kind of looking at how maybe pollution in one country is induced by consumption in another country. And another thing that we're interested in is that this kind of pollution inequity metric that we've introduced here could really be used to study all kinds of different things, you know, things like inequities in water pollution, climate change, things like that.

CURWOOD: Christopher Tessum is a research scientist at the University of Washington and lead author of the study we've been discussing. Christopher, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

TESSUM: Thank you. It was great to be here.

Related links:

- NPR | "Study Finds Racial Gap Between Who Causes Air Pollution and Who Breathes It"

- The study in PNAS | “Inequity in Consumption of Goods and Services Adds to Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Air Pollution Exposure”

- CNN | "Hispanic and Blacks Create Less Air Pollution Than Whites, but Breathe More of It, Study Finds"

[MUSIC: Kim and Reggie Harris, “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle” on Get On Board, by Roberta Slavitt, Appleseed Recordings]

CURWOOD: Coming up – An African American outdoor educator on diversifying the outdoors culture. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Patty Larkin, “Banish Misfortune/Open Hand” on Angels Running, Tradition Irish/arr.Richard Thompson, BMG Records]

Redlined Real Estate & Extreme Urban Heat

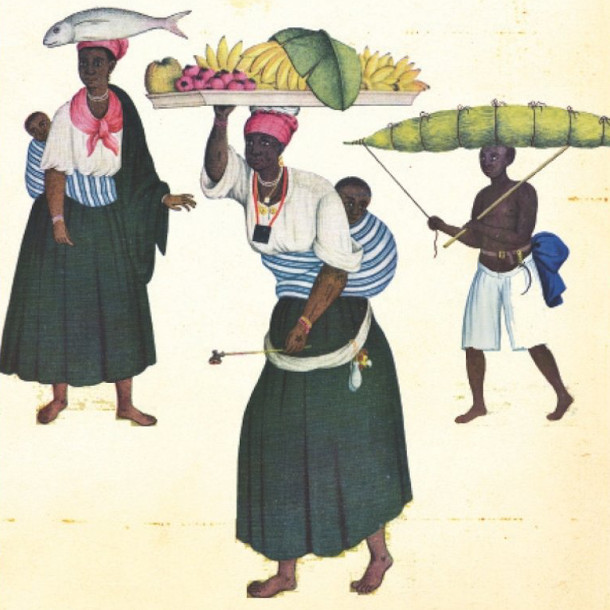

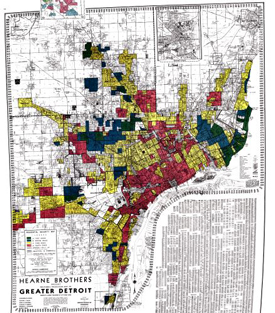

Jacksonville, Florida has a long history of segregation. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

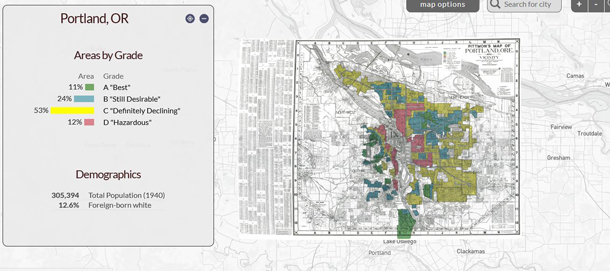

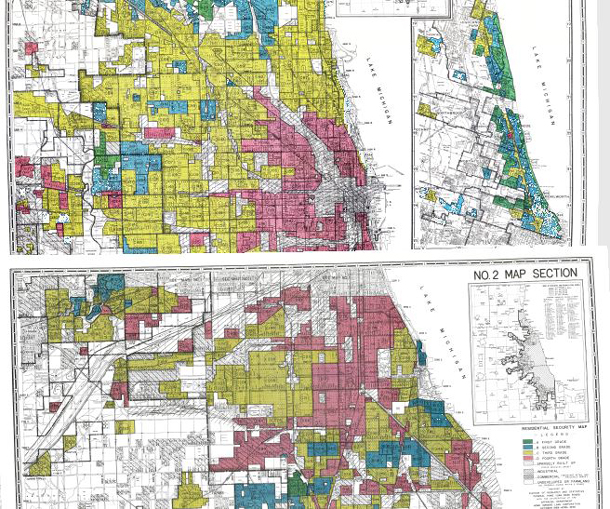

In the 1930s, while the world was digging out of the Great Depression, the US government drew up maps of more than 200 cities and gave grades to individual neighborhoods based on perceived suitability for homebuyers to obtain a bank loan. A-grade areas were outlined in green. They were largely suburban and white. D grade neighborhoods were outlined in red. Those tended to be in city centers and black and brown. Despite similar household incomes, home age, and other factors minority areas were more likely to be inside a red line than white ones, making it much tougher for people of color to get home loans. Nearly 100 years later the legacy of redlining persists in many ways, including increased risks from heat waves linked to climate change. Writing in the journal Climate, researchers found that during heat waves redlined neighborhoods can be as much 10 degrees hotter than other districts in the same city. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb spoke with Vivek Shandas, a lead author of the study and a professor at Portland State University.

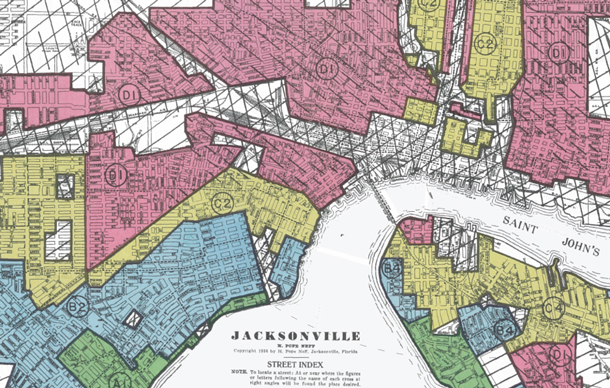

SHANDAS: What we wanted to look at is just one climate induced stressor that we know is going to increase in frequency, magnitude and duration over the coming decades and that's urban heat. Urban heat kills more people than all other natural disasters combined in the U.S. and it particularly is a very selective killer in that the people who have died have been historically underserved communities, historically, black communities. And so we wanted to see was that policy that was fundamentally based on race and social class was that playing out to affect the communities today in terms of who's exposed to those intense heat waves at a much higher magnitude than others. And what we found was that pretty much across the country in the hundred and eight cities, we looked at those areas that were hotter, were those redlined neighborhoods.

BASCOMB: And to be clear, I mean, this is the same city we're talking about. So you're sitting in Portland, Oregon, which I believe was the city with the highest discrepancy of temperature in these redlined areas versus non-redlined areas. But why is that? I mean, why within the same city are you seeing such a dramatic temperature difference?

SHANDAS: The temperature differences are largely a factor of differences in the physical environment. So what is in those neighborhoods now that where formerly redlined. And what we see consistently is that those neighborhoods are often either right on top of or adjacent to industrial areas. Those areas are often where the biggest freeways or highways were put in, in the 1950s. We see those areas as often having a lot fewer trees and a lot more impervious surface or that kind of concrete or asphalt that really absorbs heat over time. And so this is a phenomenon that is consistent across these cities we looked at and these historically, redlined areas have the built environment that absorbs the sun's radiation and amplifies temperatures a lot more. And as you were saying Portland, Oregon is top of the list though, Denver, Minneapolis, Columbus, Jacksonville, Philadelphia, Louisville, Baltimore. They're all in that top range of cities as well.

BASCOMB: Well, what kind of effects do you see in communities that are hotter than others? I'm thinking of even crime. I mean, I know I get cranky when it gets hot out. And we routinely see spikes in crime rates in cities, particularly when it gets really hot. Do you think that any of that can go back to this policy?

Only 11% of Portland, Oregon was considered desirable for mortgage loans between 1930 and 1940. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: Yeah. So we've seen that people's behavior changes when it gets hotter. We've seen for example, more use of energy, we've seen greater hospitalizations, we've seen more issues of road rage and violence that happen when things get hotter in cities. And what that really comes down to is our mental health ability to cope as well as our physiological ability to cope and health impacts from increased heat as well. So we can talk about children that are exposed to heat. We've seen studies come out about how children at school are not able to focus are not able to actually do well and learn as a result of hotter classrooms or hotter environments. And so that can have a long-term effect on an ability to actually complete school. And that leads to a whole series of outcomes as well. We see this playing out in terms of our financial health; people are running their air conditioner much harder if they have access to air conditioning and have financial resources to run it. So that's money that's going away from other things like food or education or health that can be some of the basic needs for a community. And then of course, we have older adults, particularly those that have pre existing health conditions like asthma or any kind of heart condition. We've seen more recent work that's been done on stroke, brain health, in terms of heat, and that can have profound effects as well. Working with some folks at UCLA Medical School to try to better assess some of those impacts and there's no shortage of heat and and health related impacts that are occurring.

BASCOMB: We had a story on the show recently, in which we talked a bit about the dramatic difference between white and African American babies and infant mortality rates. And the statistic that really struck me is that a black woman with an advanced degree is more likely to lose her baby than a white woman with an eighth grade education. So it's not about affluence. It's not about, you know, education. To what degree is it possible that living in hotter communities is putting a physical stress on pregnant African American moms and resulting in higher infant mortality rates for them?

Map of redlined areas in Detroit from 1940: 6% were considered desirable (marked in green), 14% was considered still desirable (marked in blue), 51% were considered declining areas (yellow), 28% were considered hazardous (pink). (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: Right. Fascinating question about the relationship between race, health and climate and a lot of the study really has some potential directions. While we don't study that in this work right here, I will say that with redlining, we find that the communities living in historically redlined areas are still communities of color are still immigrant communities are still indigenous communities and, in part what that suggests is that if you have communities of color, like a black woman living in a formerly redlined area, what you're going to see is temperatures that are sometimes five eight, ten, twelve and we've even documented air temperatures of 20 degrees hotter in particular parts of a city. So if you're talking about a 90 degree day for one part of the city, another part of the city could see 110 degree day. And once you cross that, around 98.6, about 37 Celsius degree our body is trying to cool down so our body uses sweat to be able to cool itself down. And I'm not a medical doctor though in collaboration with them, I've learned that this sweating process really helps us cool down though if the ambient temperature is hotter than 98.6 and if the humidity levels are high, we could reach this threshold called wet bulb temperatures, that's W-E-T B-U-L-B temperatures which are a point at which our body is unable to kind of cope and cool down. And so that stress that the body faces goes right into the womb that an unborn child is in and that's a level of stress that's part of that pregnant mother and that then affects the child. What we've seen in a project we're working on with five states and cities and in five states where we're looking at birth outcomes in relation to heat and air quality, we've actually seen that the smallest babies have some of the biggest effects. So these are preterm births have some of the biggest effects from the mother being exposed to extreme heat and poor air quality. So what that means is that a child being born very small actually ends up being born even smaller as a result of this exposure. And the smaller the baby gets, the more that baby has to really struggle in order to be able to live and it leads to as we've learned from the field of epigenetics, long term consequences on the health and well being of that person. The effects of redlining then can really play out in terms of what the environmental conditions are that a person, let's say, in this case, a black woman is exposed to, and that can lead to long term consequences on their ability to manage their own as well as their children's health.

BASCOMB: Well, it's just, it's just shocking, really how, a racist policy from almost a century ago, is persisting in so many different ways and has such long term health impacts on people that had nothing to do with that back then.

This is a map of the different levels of redlined areas in Chicago. The green areas represent desirable areas (A areas), the blue areas are still considered good but not a “hotspot” (B areas), the yellow C areas are considered declining areas, and the pink D areas are considered hazardous. (Photo: Digital Scholarship Lab)

SHANDAS: Right, right. And you know, in public health, it's a very common phrase now to be talking about your zip code is more important than your genetic code. And I've heard that said by a lot of very impassioned and very committed public health staff and various agencies and community health workers, etc. And what occurs to me is that the fact that your zip code is so important for your health and well being has a lot to do with how we're going about planning our places and planning our cities. And that's really what a lot of this work kind of comes back to is, how did this policy really underscore the racial underpinnings of the country.

BASCOMB: So for somebody that's listening right now and nodding their heads in yeah, you know what it is hotter where I live, then where I work. Maybe I'm living in one of these communities that's suffering from these racist practices, what can you say to those people?

Vivek Shandas is a professor of climate adaptation at Portland State University and co-author in this study. (Photo: Vivek Shandas)

SHANDAS: Part of my job is to study cities. And I've heard a lot about people really pointing and blaming and saying, you know, I wish people in that neighborhood would take better care of their place, or I wish they would be more engaged, or I wish they would be doing things differently. And there's a lot of this, that I hear from communities that I talked to about blaming communities of being kind of, quote, sketchy or being, quote, not really worth visiting. And these are things that really hit me pretty hard, because I see through studies like the one we did, that this was a very systematic process that actually is no fault of the people that actually live there. And I guess that's really kind of at the core of what I'm hoping that this study will help reveal is that these are kind of underlying challenges that have been there and a long time. And our work then in front of us is to be engaged with the planning that's happening in our backyard with the planning that's happening all around us and to be kind of really mindful about the fact that the decisions made today could have repercussions twenty, fifty, one hundred years later, and to kind of go into this planning process thoughtfully and with recognition that these historical practices are things we have to undo and things we have to center in our current work, climate or otherwise.

CURWOOD: Portland State University professor Vivek Shandas, speaking with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- Click here for a virtual map of redlined zones across the United States

- Click here to read The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat: A Study of 108 U.S. Urban Areas

[MUSIC: Pat Donohue, “Ain’t Misbehavin’” on Jazz Classics for Fingerstyle Guitar Volume Two, by Thomas “Fats” Waller/Harry Brooks/Andy Razaf]

Why I Wear Jordans in the Great Outdoors

CJ Goulding has only ever owned one pair of Air Jordans – a status symbol to some African-Americans -- but he’s not too concerned with keeping them pristine. (Photo: Cherish, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: A lot of backpackers wear special hiking boots when they are out on the trail, but not C.J. Goulding. CJ is a Program Manager for the Children and Nature network and when he leads young folks out for a hike C J himself wears basketball sneakers named after Michael Jordan. Here’s an excerpt from his blog on why.

GOULDING: I am an African American natural leader. That phrase is not an oxymoron but it's also not something that you normally see in the environmental world. In the few years that I've been involved in environmental education and connecting people with outdoor spaces, there have been numerous occasions where I'm the only person of color in the program, or the only African American leader. Growing up, there was no one from my neighborhood traveling, hiking, canoeing, or spending time outdoors unless it was a part of a regimented program.

But do not misunderstand the meaning behind that statement. Do not miss my point. I write neither to complain that the outdoor world is an elitist one, nor to lament the disconnect between the world I grew up in and the natural world where I now lay roots. I write to celebrate the amazing opportunity available for me and others like myself to be a bridge between the two worlds.

On my feet as I write our Jordan Bred 11s the only pair of Michael Jordan sneakers I've ever owned in my life. His sneakers are a status symbol in the neighborhood I grew up in, a memento of importance and significance. Unfortunately for some people, they hold higher value than food, books rent, and in some extreme cases, even the life and well being of another individual.

So it makes sense that while facilitating an outdoor youth summit at Harpers Ferry National Park in Virginia, an African American teenage boy stopped me to ask why I was wearing these Bred 11s outdoors. I laughed. I asked him if he had seen anyone who would wear Jordans exploring the outdoors like we were. He said no. Right there, the disconnect between the two circles was evident. And as we looked around, we could see that even there at that event we were in the minority.

I've heard the rallying cry echo, through the trees affirming that the outdoors are for people of all creeds, countries and colors.

My Jordans are now falling apart, worn from adventures in places like the Grand Tetons and the Grand Canyon. Hiking through the topography of Los Angeles and Arctic Village. This goes directly against how people quote unquote should wear them and what people quote unquote should wear outdoors. But I wear them wherever I go to remind me of the fact that though there are two worlds, I am a bridge. And I'm constantly reassured of its validity whenever I see another young leader follow the footprints of my Bred 11s into the woods.

CJ Goulding leads participants from Los Angeles and Alaska in the Fresh Tracks: Leadership Program. Fresh Tracks is a cultural exchange program that builds participant skill/knowledge in cultural competence, civic engagement, and hometown stewardship. (Photo: Tony Teske)

CURWOOD: So CJ, what was the outdoors experience that hooked you?

GOULDING: Growing up as a kid I was a wanderer and so I'd just explore the neighborhood, the trees, any forested areas, my grandmother's backyard, spending a lot of time working in her garden, and planting things and flowers and vegetables and things like that. So that's a key component of my environmental ethos.

CURWOOD: CJ, what do you think it is that keeps Black people away from nature here in the United States?

GOULDING: I think white supremacy has existed to amplify the disconnect that we have had with nature. A lot of times, history of Black people and African Americans is told starting at slavery, and that's not true. Before that, way before that we had a connection to the land, we had a connection to each other and communities. And so oftentimes, that story gets lost. And it's on purpose because a grounding and a connection in nature, amplifies and completes us and strengthens our culture. So that disconnect shows up through the way that communities of color and black people live inside inner cities with not easy access to nature, that shows up in the way that our education doesn't include that kind of knowledge. That shows up in the way that white folks have taken over some of these industries connected to the outdoors and made them an experience that requires a lot of time and a lot of money. So that connection is always with us. But I think white supremacy showed up in a way that wants to separate us from these life giving qualities.

CJ Goulding has been involved in REI’s #OptOutside campaign, which is aimed at connecting people to nature and reducing waste across the outdoor industry. (Photo: Tony Teske, REI)

CURWOOD: Tell me how do you think the the Jordans Bred 11 helped to connect with folks.

GOULDING: I call it my stepping stone theory. And for me the idea of connecting people to nature or connecting people to anything unfamiliar sometimes it's like a river that's or a creek that's running by and you can't jump it immediately. You're not comfortable enough to make that large leap. And so the Jordans helped me to be that stepping stone in the middle where I'm able to build a connection with someone and help them feel comfortable stepping into the middle because they understand that I'm there. They connect to me because I'm showing up as myself because they understand that I know who they are and where they come from. And then they feel more comfortable stepping into that unknown whether it's nature or anything else in terms of development and exposure that they're looking for.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent did you get pushback or question or even ridicule from white people who saw your show up in what they see is anachronistically his tennis shoes?

GOULDING: I think sometimes it shows up as 'hey, you're not wearing the right shoes' because they think they know the correct shoes to wear outside or outdoors and understanding that the outdoors can get to gear centric and you really don't need right shoes. You don't need $120, $200 boots to go outside. All you need other sneakers that are on your feet.

CJ Goulding is lead organizer at the Natural Leaders Network based in Seattle, Washington. (Photo: Tony Teske)

CURWOOD: Those Jordans aren't cheap though.

GOULDING: Well mine were. I got those for $4.95 at a thrift store in Alabama, so I would definitely consider that inexpensive.

CURWOOD: So after they said those aren't the right shoes, what did you say to them?

GOULDING: I don't care. [LAUGH] I mean, I realized that I had something to teach them as much as they had to teach me. Understanding that there are some cases where I need special gear and equipment and then understanding that there are some cases where it's just marketing. And I knew that my primary purpose was one to stay safe and I was doing that but ultimately to connect with the young adults I was working with.

CURWOOD: CJ Golding is a program manager for the children and Nature Network. CJ, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

GOULDING: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read more from CJ Goulding

- CJ Goulding is a Lead Organizer for the Natural Leaders Initiative from the Children & Nature Network

- CJ Goulding's essay is featured in the book, “Coming of Age at the End of Nature”

CURWOOD: Coming up – Farming while black, a conversation about reconnecting with the land. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “Hula Lady” on Wooden Boat, Dancing Cat Records]

Farming While Black: A Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

Run by a collective of Black, Brown and Jewish people, the mission of Soul Fire Farm is to end injustice within the food system. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Leah Penniman is an activist working towards environmental, racial, and food justice through her work at Soul Fire Farm, a collective of ten Black, Brown, and Jewish farmers. Their goal is to dismantle racism within the food system while reconnecting people of color to the earth. Leah has a book called, Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm's Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land. In it, she describes her journey as a woman of color reclaiming her space in the agricultural world, while providing a comprehensive guide for others who may want to follow her path. Welcome to the show, Leah!

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: Tell me a little bit about your journey falling in love with nature and farming, and how it has led you to create your book, “Farming While Black”.

PENNIMAN: Well, nature was my only solace and friends growing up in a rural white town. Our family was, you know, one of the only brown families, if not the only in the entire town. So, we were subjected to a lot of harassment and assault and abuse, and so, in absence of peer connection, I went to the forest and found a lot of support and love in nature. And so, when I became old enough to get a summer job, I was looking for something that kept alive that connection and was able to land a position at the Food Project in Boston, Massachusetts, where we grew vegetables to serve to folks without houses, to people experiencing domestic violence. And there was something so good about that elegant simplicity of planting, and harvesting, and providing for the community. That was the antidote I needed to all the confusion of the teenage years. So, I've been farming ever since.

CURWOOD: Now, that's interesting. A lot of people say when they connect with nature, they connect with creatures. You connected with plants, it sounds like.

PENNIMAN: Well, plants don't talk back, right?

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

PENNIMAN: No, I feel connected to the whole ecosystem, but the plants are incredible. They have these secret lives that we can't see, or even imagine. So take, for example, the trees of the forest, right? There's a underground network of mycelium that connects their roots, and they're able to pass messages and warnings. They pass sugars and minerals to each other through this underground network. And they collaborate across species, across family. And so, when we tune into that, I think we learn something about what it is to be a human being and how to live in community with each other in a way that if we're not connected to nature, we sort of lose that deeper sense of who we are, who were meant to be.

Leah Penniman is the author of Farming While Black and one of the co-founders of Soul Fire Farm. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

CURWOOD: Now, your book is not only a how-to guide for folks who are interested in pursuing a path similar to yours, but it also, well, it has some history, sociology, environmental lessons all wrapped up in this package. Why did you add those additional stories and information in with your guide, rather than it, well, having it be strictly a manual?

PENNIMAN: Well, I wrote this book for my younger self. So, after a few years of farming, I would go to these organic farming conferences, and all the presenters were white, you know, all the books were written by white folks, mostly white men. And so I started to feel this real crisis of faith in my choice to become an organic farmer, like wondering, as a brown-skinned woman, whether I had any place in this movement, if I was being a race traitor, and I should, you know, focus on housing issues, which are equally important, or some other issues. And so, in putting together this book, I was really thinking about myself as a 16-year-old and, all the other returning generation of black and brown farmers who need to see that we have a rightful place in the sustainable farming movement that isn't circumscribed by slavery, sharecropping, and land-based oppression, that we have a many, many thousand-year noble history of innovation and dignity on the land.

So, those anthropological pieces that uplift, you know, the raised beds of the Ovambo and the terraces of Kenya, and the community supported agriculture of Dr. Whatley, those are to remind us that, you know, we've been doing this all along, and we belong, and we're standing on the shoulders of our ancestors. We're not trying to create something new right now.

I mean, aside from writing it for my younger self, I'm a super nerd. And so, there was something that, you know, I had heard, for example, that Cleopatra was really into worms. And so casually, I'm telling this antidote to youth who come to our farm, right? I'm like, oh, yeah, these worms, Cleopatra was into them. She was like, into vermicomposting. But I wasn't super sure that that was true. And so in writing a book, you can't just write down anything you feel like writing, you know, you have to do research. And so this process of digging through the literature and finding and verifying these stories about our people just satisfied this academic itch that I had.

So, more importantly, though, than my personal need, we have waiting lists for our black and brown farmer training programs many years long. And so, I didn't want to be a gatekeeper any more to this really important practical knowledge, or the historical and psycho-spiritual knowledge. And so putting it in a book, just lets a lot more folks have access to the things we've learned in over a decade of practice at Soul Fire Farm.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, you have a waiting list of people who want to come to Soul Fire Farm and learn how to do this?

PENNIMAN: Right? Contrary to popular belief, black and brown folks do want to farm. And this was something that just surprised me because I thought I was just a weirdo out here, I was going to start this farm with my family, grow food, provide it to those who need it most in the community. And that was going to be it. And I got a call our first year from this woman, Kafi Dixon in Boston who said, you know, through tears, I just needed to hear your voice to know that it was possible for a woman like me to farm, and that I wasn't crazy, and that there's hope. Right? And that was the first of thousands and thousands of phone calls and emails to come of folks saying, “I need to learn to farm, I want to do it in a culturally relevant, safe, space. I want to learn from people who look like me.” And so we opened the training program and I posted on Facebook. It filled in 24 hours. So I posted another one and it filled. And that's just the way it's been. It seems that we have realized as a generation that we left something behind in the red clays of Georgia, and we want to get it back. And so we're doing our best to respond to that call at Soul Fire.

Soul Fire Farm is located in Grafton, New York and is active year-round. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: Talk to me a little bit about how access, or the lack of access to healthy food can have an effect on a family, especially families of color.

PENNIMAN: So, we're living under a system that my mentor Karen Washington calls food apartheid. So, in contrast to a food desert as defined by the US Department of Agriculture, which is a high poverty zip code without supermarkets, right, a food apartheid is a human created system, not a natural system like a desert. It's a system of segregation that relegates certain people to food opulence, and others to scarcity. And there are consequences to that. We see in black and brown communities a very high disproportionate incidence of diabetes, heart disease, obesity, cancer, even some learning disabilities, and poor eyesight, and mental illness can be linked to having access to Hot Cheetos and Takis and Blue Drink, but not having access to those fresh healthy fruits and vegetables that we really need to be healthy and also to be part of democracy to do our civic duty. If I'm feeling sick, or my body is too heavy, or, you know, I'm trying to just find something to eat, I'm certainly not going to be going down to City Hall and talking about how we need fair wages for farm workers or anything like that. So food is right now a weapon in our country, when it really should be a basic human right.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about urban farming, and how that can alleviate the food apartheid situation for some families.

PENNIMAN: I'm all for urban farming, and I think we actually need to do more as a society to provide the technical support through the US Department of Agriculture and other agencies so that urban farmers can be taken more seriously and provide a greater benefit for their communities. Folks who are growing food in cities are meeting the USDA definition of $1,000 worth of products, are feeding their communities, are oftentimes doing that much more efficiently because there's no transportation hurdle to overcome. So, I think it's really unfortunate that we don't often consider urban growers as farmers.

CURWOOD: By the way, one of the most intriguing sections of your book “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land” is this explanation of how you can clean up lead-contaminated soil, which you find in so many places in the urban environment. You have a very practical guide as to how you can use natural plants to chelate, that is, to remove lead from the soil, so that it's safe to grow food there. I don't think I've seen that anywhere else.

PENNIMAN: Well, that's deeply personal for me because in the same time period, when my husband Jonah and I, cleaning up soils, we would bring our newborn with us and we didn't know anything about lead in the soils at the time, and she got lead poisoning. When we went back and tested, we found around some people's homes 11,000 ppms. Now, the safe limit is 400 parts per million. So 11,000, that's a super toxic site. And these are people's yards, where children are playing. So, our daughter is fine. But we started a project called Toxic Soil Busters to clean up that lead. And there's an incredible plant, it's an African origin plant called Pelargonium or scented geranium, and it's a hyper accumulator. So, you can plant it, you acidify the soil, you plant it and it will suck the lead out and store the lead in its body. So, then you can dispose of that plant in a safe place. And over months or years, depending how bad your situation is, you have a healed soil. And that's so important because, you know, as black and brown folks, as poor folks, oftentimes we don't have access to prime bottom lands, soil. And so that doesn't mean actually giving up on the earth or giving up on self sufficiency. We have to be able to restore degraded and marginal lands.

Farming While Black is not only a manual but a look into the history, sociology and science of farming. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

CURWOOD: Sometimes the sciences, especially that love of nature and the environment and pursuing a career in those fields can seem, well, rather taboo for people of color. Why do you think that is? How do you think your book response to this?

PENNIMAN: It's heartbreaking for me, though, not surprising, because what it really speaks to is the depth of the inherited trauma from the centuries of slavery, sharecropping, and tenant farming to the point where just seeing a plant or seeing the soil is going to be a triggering experience for a lot of folks. Look at nature for really what it is, it's the scene of the crime. The nature is the scene of the crime, but she's not actually the crime. The way we try to address that is a couple of ways. One is to again, reach back beyond those 500 years to the 10,000 years of, of noble history on land and revive those stories and live into those stories. But it's also to confront the trauma head on.

CURWOOD: In your view, what have people of color lost by not having the farm as possible place of family refuge?

PENNIMAN: I was talking to an elder friend of mine, Donald Halfkenny, who is a civil rights veteran and was telling me stories about his time during Freedom Summer, registering people to vote in the south. And he was saying that they all stayed on black farms, all these activists, and they were protected. The farmers, to prevent Night Riders from coming and attacking the activists, would cut down trees and put barriers across the only road that got you out to these rural areas to slow down or to impede members of the Ku Klux Klan. All the meetings, if they you needed your shoes fixed, you needed a meal, it was the black farmers, and Mr. Halfkenny was saying that, you know, this was a clandestine network too, because then you'd see the same people that put you up in town the next day, and they act like they didn't know you because they also had to protect their own safety. And so I think about that a lot, that there really would be no civil rights movements without black farmers.

CURWOOD: And what do you think people of color lost when we lost contact with the land?

PENNIMAN: Certainly not all folks of color, right? Right now, about 85 percent of our food in this country is grown by brown skinned people who speak Spanish. And there's a whole history to why that is. But I would say, particularly for black folks, after the Great Migration, when six million of us fled the racial terrorism of the South, I think we did leave behind a little piece of ourselves. And, you know, it's a belief in West African cosmology that our ancestors exist below the earth and below the waters, and by having contact with the earth we've received their wisdom and guidance. And with the layers of pavement, and steel, and glass, and the skyscrapers, it’s harder to feel that contact, it's harder to have the generational wisdom. So, my personal belief is that many of us go around with this nagging sense of emptiness that we can't quite name. And when folks come to Soul Fire and get their feet back on the earth, what I hear time and again is, I'm remembering things I didn't know that I forgot.

When we own land, we also have power, we have autonomy, we have agency. When we depend on a system that hates us for our basic rights, our basic needs, we depend on a system that hates us for our food, our shelter, our meeting space, we're always in some way going to be beholden to that system. And so it limits our ability to resist. Folks, half joking, but maybe not, are always saying, well, thank God we have Soul Fire because when Armageddon comes, or when such and such, we have a place to go, and there will be food and there will be safety.

CURWOOD: Leah, how can farming and food be a healing and culturally restorative process for someone?

PENNIMAN: Hmm. You know, so often as black Americans we’re fed this myth that we don't have any culture, it was all lost in the transatlantic slave trade, we have no language, you know, we don't have a religion. So, we just need to try to emulate the ways of Europeans. And the better we get at it, you know, the higher status we gain. And in using food and land as tools, we reconnect to a different meter stick of success and belonging. And it's one that comes from our people. I mean, for example, just the other day, we're harvesting squash that we grew ourselves. Squash seed was a gift from the Taíno people to the enslaved black people of Haiti. In exchange for the seed that we brought over, hidden it in our braids, which was the cowpea, or the black-eyed pea. And so we took this squash seed as a gift from the native people and we grew it. And for many years, the ones who call themselves masters, the French did not even allow black people to eat this squash, we called it joumou, it was such a delicacy. It was a very tasty, and smooth, and sweet, so it was only prepared for white folks. After the successful revolution in 1804, we celebrated, our people celebrated by making the squash, the joumou soup, and every house made some. You go from house to house and sip it and taste all the different recipes. And that's been a tradition every January 1.

Soul Fire Farm offers trainings for People of Color to connect with the land and learn essential agricultural skills while also addressing the long and complicated history between people of color and nature. (Photo: Soul Fire Farm)

CURWOOD: How do you feel about organizations like your Soul Fire Farm? How do you feel they're doing it bridging this gap between people of color and reclaiming their birthright really?

PENNIMAN: How are we doing? I mean, I don't know if it's really for me to say because I feel like we're in service to our ancestors and to our community. And so everything we do is because we've been asked to do it. But I can say for sure that everyone who's gone through our program has talked in some way about this being what it would feel like if we were free, about this being a calling home to not settling anymore for being less than our full selves, for this being a healing repurposing. And we have, last time we did a survey, 86 percent of folks who graduated from our program have continued the work, so they're growing food, or they're organizing for food justice. And that means the world to me because I really want to be, not so much to expand and grow up as an organization, but really more like mycelium to grow out and figure out how to feed our alumni and other folks in the community who are doing projects that meet their local needs. And, you know, I think we're starting to see that, we're starting to see that resurgence.

CURWOOD: Leah Penniman’s book is called “Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land”.

PENNIMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Soul Fire Farm

- The Farming While Black book website

- Leah Penniman speaking March 23, 2018 in Ithaca, NY: "Uprooting Racism in the Food System: A Legacy of Resistance"

- More about foreword Author Karen Washington

[MUSIC: Curtis Mayfield , “Move on Up” On Curtis 1970 Warner Bros records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Mark Seth Lender, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us please, on our Facebook page- Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth