August 28, 2020

Air Date: August 28, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Republican National Convention

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

The 2020 Republican National Convention featured testimonies from people across the country. Climate change was rarely mentioned in the convention with a few exceptions where curbing carbon emissions were represented as a menace to the American economy. Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Bobby Bascomb to discuss what was said about climate change in the 2020 Republican National Convention. (09:31)

Container Farming in the City

/ Aynsley O'Neill & Jay FeinsteinView the page for this story

Modern industrial agriculture is a resource-intensive endeavor, requiring massive amounts of land, water, and energy. Some urban farmers are thinking outside the box by bringing their farms inside the box in the form of shipping containers. Living on Earth's Jay Feinstein and Aynsley O'Neill took a trip to Corner Stalk Farms, in East Boston, Massachusetts to find out more. (11:13)

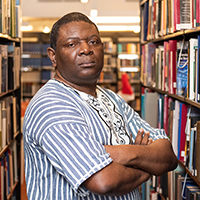

Saving West Africa’s Last Rainforest

View the page for this story

When an oil palm development in the poor West African country of Liberia uprooted indigenous communities, destroying their religious shrines and burial grounds, and moved to cut down the last major swath of tropical rainforest in the region, lawyer Alfred Brownell jumped into action. He and his colleagues were able to persuade the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil to get the company to back off, but not without great personal risk. Attorney Brownell, who has been recognized with a 2019 Goldman Environmental Prize, tells Host Steve Curwood why the remaining Liberian tropical rainforest is so important to protect, as a vital natural resource and as the home of indigenous people. (26:16)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alfred Brownell, Shawn Cooney,

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Aynsley O'Neill, Jay Feinstein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX this is Living on Earth

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

A Goldman prize winner says protecting nature is worth the ultimate sacrifice.

BROWNELL: If no one is prepared to lay their life down, to fight to preserve Mother Nature, to protect this planet, to ensure that generations unborn will come and have a safe and healthy environment, if the world and the planet is not worth the battle, what else are you prepared to give your life up for?

CURWOOD: Also, turning one of those big metal shipping containers into an indoor urban vegetable garden.

COONEY: It is basically a hyper local thing. The reason we keep the customers is it's a better product than what you can by at, you know, pretty much anywhere. Basically what it comes down to is it looks better. It tastes better, and it's got more nutrients, and it feels better. It's got better texture. So that's kind of what people are buying.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jerry Garcia and David Grisman, “Teddy Bears Picnic,” on Not For Kids Only, by John Walter Bratton and Jimmy Kennedy, Acoustic Disc]

Republican National Convention

President Trump gave his closing speech for the Republican National Convention from the south lawn of the White House. (Photo: Screenshot of 2020 Republican National Convention)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Well, the Republican National Convention is now in the history books and for more here’s Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: The RNC this year was held against the back drop of wildfires raging in California and hurricane Laura battering the Gulf Coast – they types of natural disasters that scientists tell us are becoming more common and destructive with climate change.

The threat of climate change though, was barely mentioned in the prime time RNC speeches.

Mr. Trump did talk about renewable energy before a small group of supporters at the convention in Charlotte, North Carolina.

He explained the difference between himself and his Democratic opponents.

TRUMP: We've achieved American energy independence and we're now number one in the world by far. [CLAPS] And I saw where I saw where these phonies, you know, they want to end everything we've done they want to end it they want to go to wind they don't even know if they want to go to wind. I think they want to just basically close up our country because they take away our strength, but they want to do something, but there is no such thing. Solar can do it. I love solar so fun, you know, very very heavily expensive, very expensive but they want to go to other forms of alternate alternative energy and I think that's okay. Except we don't have them and it's not going to power these massive factories. So we need an hydro, I love it. It's it's one of my all time favorites. hydro hydro I love I have to tell you, that's the great dams. You don't see that too much. You know why the environmentalist say you can't build a dam there. But now we can because we've done we've done things that nobody thought were possible. Like example, the Keystone pipeline we got that approved the Dakota Access Pipeline they were all bogged down. Right, right? We got it approved.

BASCOMB: For more on the Republican National Convention I'm joined now by Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with environmental health news that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter. So what was your take on the RNC this year?

DYKSTRA: Or what didn't I see? Hi, Bobby. There's very little direct mention of environmental virtue in here. A lot of the attacks on past environmental policy and on Biden and Harris's potential future environmental policy dealt with excessive regulation, which of course, was a big focus of the first term for Trump and Pence. Much of that was presented through a lobstermen, a logger and a farmer who came on almost ensemble form as the anti regulatory village people.

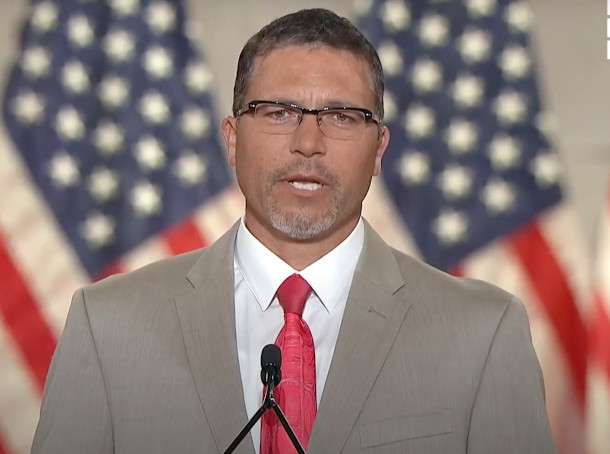

BASCOMB: Right? Yeah, there was a lobstermen from Maine named Jason Joyce, who used his time to talk about environmental extremists and his opinion, he was really upset about the Obama administration setting aside ecologically sensitive Atlantic canyons were endangered whales and other species live and he said that it affected his industry it affected lobstering. Let's listen to him.

Jason Joyce spoke on the second night of the republican Convention about the struggles faced by the fishing industry. He thanked President Donald Trump for choosing to remove protections to Atlantic Canyon. (Photo: Screenshot of 2020 Republican National Convention)

JOYCE: I make my living from lobster fishing, oyster farming and providing eco tours in the beautiful waters near Acadia National Park, where I have over 200 years of family history. I live in an island with 370 residents and lobstering is how we provide for our families. Main's lobstermen, are true environmentalist. We practice conservation every day. If we didn't, we'd be putting ourselves out of business. Four years ago, the Obama Biden administration used the Antiquities Act to order thousands of square miles of ocean off limits to commercial fishermen. They did it to cater to environmental activists. Although Main's lobstermen don't fish there, Obama's executive order offended us greatly, it circumvented the Fisheries Council's input. President Trump reversed that decision reinstating the rules that allow stakeholder input and he supports a process that seeks and respects fisherman's views. As long as Trump is president, fishing families like mine will have a voice but if Biden wins, he'll be controlled by the environmental extremist who wants to circumvent long standing rules and impose radical changes that hurt our coastal communities.

DYKSTRA: Of course, now your self respecting lobsterman or no self respecting lobster would find themselves in an area of sea mounts and deep canyons, that's what that Obama created national monument was for. One thing we didn't hear that we could have heard from the good captain, is that there are multiple studies telling us that climate change and warming ocean waters could take lobsters completely off the menu in Maine, possibly within 30 years, as it's largely already done in Long Island in Southern New England. The convention also featured a dairy farmer complaining about regulations and a Minnesota timberman doing the same.

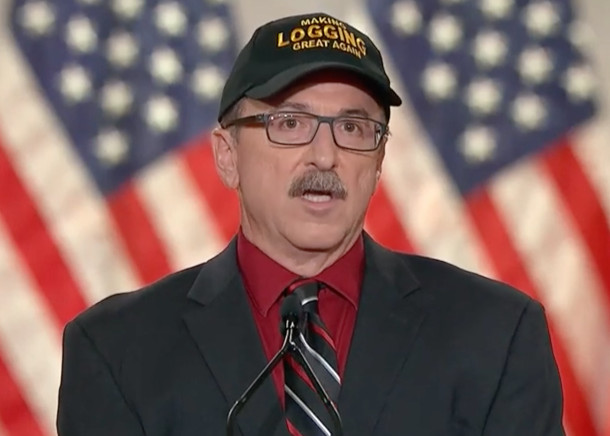

BASCOMB: Right? The logger, his name is Scott Dane. Let's hear what he had to say.

DANE: Under Obama Biden radical environmentalists were allowed to kill the forest. Wildfire after wildfire shows the consequences. Managed forests the kind my people work in are healthy forests. Under President Trump, we've seen a new recognition of the value of forest management in reducing wildfires and we've seen new support for our way of life. Where a strong back and a strong work ethic can build a strong middle class.

Scott Dane, a Gilbert Logging representative, spoke at the Republican National Convention about the logging industry and expressed his support for President Trump. (Photo: Screenshot of 2020 Republican National Convention)

DYKSTRA: Mr. Dane seemed kind of cheesed off by environmental regulation and in general. Another thing that was happening with forests at the time, are those massive and tragic blazes out in California. The prescription for solving them was reiterated this week by President Trump, when he once again said that all we needed to do to control massive wildfires is to rake the forest floor.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's a not a commonly held View From what I understand. Well, you know, Peter, last week we talked about the Democratic Party platform and the fact that the Dems kind of hid their environmental ambitions there, instead of putting them front and center in the Primetime speeches. But the republicans this week they actually didn't put out a new party platform and from what I understand, it's the first time since 1854, when the Republican Party was formed, that they didn't put out a new platform. Instead, they decided to keep word for word, the exact same party platform that they adopted in 2016. What do you make of that?

DYKSTRA: To me, the only thing you could make of that is that the republicans don't see any platform problems that need fixing that goes for the environment as well. Several times they bashed what they call the current administration in the platform, even though the current administration is the Trump administration when they meant to say, the Obama administration.

BASCOMB: Right, yeah, it was rather confusing to read at some points. They did put out a 50 bullet point plan for the next term that included things like deregulation for energy independence and keeping our water and air crystal clear, as they call it and working internationally to clean up oceans. You know, from what I saw, these were literally one sentence long points, there was nothing to say how they plan on doing any of those things,

DYKSTRA: Right, no roadmap for seeing them through. Of course, if you have a platform, not knowing whether or not you're going to maintain control of the Senate, that's an issue as well that has to be in the back if not the front of everybody's mind. And as far as crystal clear water goes, that's going to be harder to achieve if you're rolling back big sections of the Clean Water Act. As for energy independence, there's precious little mention of clean energy as a role to that not just coal and oil and gas.

BASCOMB: Well, it was an interesting week. In any case. What are your take homes from it?

The Republican National convention kept the same party platform and slogan “Make America Great Again” from 2016. (Photo: Screenshot of 2020 Republican National Convention)

DYKSTRA: Well, a little historical digression. Back in 2016, there was a guy destined to be a major environmental player who spoke for six minutes at the convention. That was a young congressman from Montana former Navy SEAL and Eagle Scout. That's Congressman Ryan Zinky. He didn't speak about the environment, he spoke about the military but a few months later, he found himself as Trump's first Secretary of the Interior until parallel corruption scandals broke out about alleged cronyism and wild spending for things like $139,000 for new doors for the Interior Secretary's office. That's Ryan Zinky for you. He lasted a little less than two years. There's one other little irony that I think went largely unspoken in the Republican Convention it was held in a beautiful venue called the Mellon auditorium on Pennsylvania Avenue, right next to the Trump International Hotel, by the way, it's a federal property but it can be rented out by anyone in America. It was rented out by the Trump campaign. The landlord's there are the Environmental Protection Agency it's in their building. And that building is named the William Jefferson Clinton Federal Office Building. That turns out to be a venue where the Trump campaign bashed the EPA and bashed every Democratic president in recent memory.

BASCOMB: And of course, the William Jefferson Clinton building is probably more better known as former President Bill Clinton.

DYKSTRA: That would be President Trump's second favorite Clinton.

BASCOMB: Alright, Peter. Well, thanks so much for watching these past two weeks and keeping us informed.

CURWOOD: That's living on earth Bobby bascom speaking with Peter Dykstra.

Related links:

- Click here to watch the four days of the Republican National Convention

- E&E News | “Trump Ignored Climate. 5 Things Are Happening Anyway.”

- NPR | “Fact Check Trump’s Address to the Republican Convention, Annotated”

Coming up – Thinking inside the box when it comes to growing fresh local food.

Shipping container farms, just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER:Support for living on earth comes from sailors for the sea and Oceana, helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC:Dick Hyman Group “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” on Sweet and Lowdown: Music from the Motion Picture SONY classical 1999]

Container Farming in the City

Corner Stalk Farm grows an acre’s worth of lettuce in a shipping container that only takes up 320 square feet. (Photo: Jay Feinstein)

CURWOOD: Industrial agriculture today is a resource-intensive endeavor, requiring big machines, plenty of land, water, and energy to produce much of the food on a typical American dinner table. And as the public trends more toward plant-based foods, some are thinking outside the box by bringing farms inside the box. By retrofitting old shipping containers with grow lights and hydroponic gear, what would take about an acre of land to grow vegetables such as lettuce can be fit into just 8 by 40 feet. Living on Earth's Jay Feinstein and Aynsley O'Neill took a trip to Corner Stalk Farms in East Boston, Massachusetts to find out more.

GPS: Your destination is on the right.

O’NEILL: The only other time I've been to East Boston was to go to the airport. So I'm a little surprised at how busy it is. And I see these shipping containers. I mean, right in the middle of these houses and behind the auto body shop...but, here we are!

FEINSTEIN: You know, the funny thing is a farm like this would not have even been legal until 2013, when Boston revamped its zoning code.

O'NEILL: I didn't even know that someone would make a farm illegal.

FEINSTEIN: Yeah, I know, right?

O'NEILL: Do you think that's the guy up front?

FEINSTEIN: Yeah, I think so.

O'NEILL: He's a little less sunburned than most farmers.

COONEY: My name is Shawn Cooney. And I'm the partner and owner of Corner Stalk farm in East Boston, Massachusetts, and we started in 2014. So this is it. So we...there's not too much to it. I mean, it's basically you've seen the whole of the farm by walking the 120 feet or so.

FEINSTEIN: That's amazing.

COONEY: And we've got four units that are you know, basically growing lettuce year round. And, you know, that's it. Do you wanna go inside?

O'NEILL: Yeah!

FEINSTEIN: We'd love to.

COONEY: Cool.

O’NEILL: Well, it's definitely a few degrees cooler in here.

FEINSTEIN: And these lights are blinding. I mean, these red and blue lights, LEDs, it’s something like out of a sci fi movie.

O'NEILL: Are those the plants in those columns all up and down?

COONEY: Right. You really need just an industrial area, You need a, you know, a place where you can basically bring as many plants as possible into as little amount of square footage as possible. So we kind of look at it as cubic feet. In a real farm, you're talking about square footage and acreage. Here, it's really cubic feet. We've got so many feet on the floor, but we plant plants up to ten high.

FEINSTEIN: So, show us around.

COONEY: Okay, so basically, you walk in and we're in a complete self-contained farm. We've got a climate control system, and a lot of fans keep the air moving so that everything's happy. And the plants get a little bit of stress. If you just leave them without any movement, the plants actually get weak.

O'NEILL: Wait, so they need exercise? They're lifting weights, they're jumping jacks, they're?

The shipping container uses a combination of red and blue LED grow lights and hanging hydroponics to grow their plants. (Photo: Jay Feinstein)

COONEY: Uh, pretty much yeah, it's stressing the plants is what it's really called in the industry, but they do need to be moved around for them to have a good texture to them, so that the cell walls are thick enough, so that it's not just eating a piece of water.

O'NEILL: And you can maintain it all using a box on the side of the container.

COONEY: Yeah, there's a tiny little antique style computer that's, that's very industrial. And you can log into it from the outside world. If you want to fiddle around with settings, or just check on everything, you can do that from home, you can do it from from vacation, you can do it, whatever.

FEINSTEIN: So how did you get into this?

COONEY: I started three software companies and sold them. And I started doing business plans, looking for the next thing, and one was the ag tech farming. This kept coming up is something that was interesting. Dug a little further, did a little more business planning, and it won. My wife and I self funded it, and we have loans and the loans are from the US Department of Agriculture, like a regular farmer would get his loans.

FEINSTEIN: So what are you growing in here?

COONEY: Well, mainly we grow lettuce. That's our business. And we've grown tomatoes, we've grown lots of flowers, we've grown all kinds of herbs, and God knows what else. But it turns out that as a business, you have to sell what people buy every day. And what people buy every day is our greens, even our restaurants, that's what they want.

O’NEILL: Well, so you sell to individuals and you sell to restaurants.

COONEY: We sell, we sell to both, we sell probably 50/50. We sell to a bunch of nice restaurants in the Boston, downtown Boston area. We deliver to them. And we sell to regular consumers.

FEINSTEIN: But still most of your customers, are they still in Boston? Because that's hyper local, when you think about it. You growing in Boston, you're selling in Boston?

COONEY: Oh, yeah. Yeah, no, they're all in the metro Boston area. A lot of Cambridge customers. But it is, you know, it is basically a hyper local thing. The reason we keep the customers is it's a better product than what you can by at, you know, pretty much anywhere. Basically what it comes down to is it looks better. It tastes better, and it's got more nutrients, and it feels better. It's got better texture. So that's kind of what people are buying.

FEINSTEIN: Tell us more about hyper local, it's sort of a buzzword nowadays. People say it's better for your health; it's better for the environment. Is that true?

COONEY: Pretty much, yeah, it's true. And it's got a downside. The downside is it's probably a little more expensive also. But it is - any vegetable, once you harvest it, loses some somewhere around 7% of its nutrient value every day from the day they're harvested, up to a point. And they lose a lot of their texture, and their attractive qualities. What we sell is still alive, we sell the lettuces with the roots on them. You get a much better life cycle lot of them that way. So they're, they're basically not losing any nutrients. And they maintain their freshness. If you ever had the experience of buying a nice box of brand name, cut lettuce in a plastic bin, that looks great, and you get home and then two days later, it smells funny and you've got black sludge on the bottom. That won't happen with what we're selling.

O'NEILL: I was wondering because there are times when I have bought, like you said, cut lettuce from the grocery store. And it's a race against the clock.

COONEY

I mean, that's one of our biggest customer satisfaction points, and our selling points was that you get to use it all. It's not like you're buying a $10 package of lettuce and using $3 worth. You know, with us you buy a $10 package of lettuce and you get to eat $10 worth of lettuce. But you can go on vacation, you can go on a business trip, and you can come back and still have something in there that's perfectly palatable.

FEINSTEIN: What type of environmental cost are you saving?

COONEY: Regular farming is a "grow as much as you possibly can and sell it when it's ready, as fast as you can". We’re an on-demand business, because we don't grow extra. We’re growing pretty much what we're selling, give or take a little bit. You know, and one of the things we definitely don't do is waste any water. No matter how good you are at growing outside, you could never grow with the kind of water use we have. We use, say 1000 plants we can grow in one unit, we probably use 25 gallons of water a week. So you couldn't water your patio plants for a week with 25 gallons and keep them alive.

Shawn Cooney and his wife Connie (not pictured) own Corner Stalk Farm, in East Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo: Jay Feinstein)

O’NEILL: So what was the inspiration behind deciding to build a farm inside? And I don't mean in a greenhouse. And I don't mean in a window box or anything like that? What was the shipping container idea?

COONEY: Part of it is, it's a durable, clean environment that can put up with the stresses that farming puts on a space. And basically there's all kinds of stuff that goes on in here that would basically bring down a building. You know, it would ruin the walls, you couldn't clean it. If something ever happened in here, we had some kind of a mold infestation or something. You could shut everything off. And you can sanitize this place just like you would the clean room in a restaurant or a food processing center.

FEINSTEIN: To what extent do you use chemicals in here?

COONEY

We do use them once in a great while. We can't be organic because we don't grow in dirt, it’s a water based environment, but we adhere to the organic principles. Generally, the way we control any kind of a pest in here is kind of preemptive. We basically use ladybugs. We ship them in once a month or so, and sprinkle them around, and they pretty much do the policing of any kind of bugs in here. And when we have had to use something it's called chrysanthemum oil.

O’NEILL: May I ask? May I try some of the lettuce?

COONEY: Sure. Okay, well we harvested some

FEINSTEIN: What is it?

COONEY: This is the Salanova Red Butter. There's not many people who actually have favorites, but if they do, this is the one that they want. So go ahead, have a taste.

O'NEILL: Sure looks like normal lettuce...

[SFX CHEWING]

O’NEILL: I don't mean to sound incredulous, but I'm a little incredulous. Might I have another one?

COONEY: Sure.

O'NEILL: Alright.

COONEY: Finish them all.

FEINSTEIN: It's very green.

O'NEILL: It's very green.

FEINSTEIN: I’m gonna try this too.

[SFX CHEWING]

FEINSTEIN: Wow, you can taste like it was grown right here. It was.

O'NEILL: It's definitely fresh. I mean, you literally just clipped it right in front of us. But it's... that's... I've never had lettuce like this. This I would eat. on its own, I don't even feel like I need to be you know, putting salad dressing on it. Or, oh, I need a crouton or something.

FEINSTEIN: And this is a weird thing to say too. But it kind of feels alive.

COONEY: You guys want to try something a little, little further on the edge? This is called wasabi arugula. And I grow it for a couple of restaurants. And they use it instead of wasabi on their crudo and their raw fish and their raw meats. So here, take a leaf of that and be prepared.

Jay Feinstein (left) and Aynsley O’Neill (right) prepare their notes and audio equipment outside Corner Stalk Farms. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

FEINSTEIN: All right, I'm prepared. I don't know what to expect here.

[SFX CHEWING]

FEINSTEIN: It does taste like wasabi. But it it's a little milder, but I love it actually.

O'NEILL: I myself am a little terrified. I have an all time low tolerance for wasabi.

[SFX CHEWING]

O’NEILL: Well, it is a bit much for me, but it is really good. And I'm a little astonished that it's not coming in those tiny little balls of green mush.

COONEY: It's actually a real arugula, and it just happens to have that flavor profile. It's not related to wasabi at all. It's the same as the arugula you buy in the plastic package, family wise.

O'NEILL: Well, I know that some people will call arugula "rocket". And that was certainly, you know, a blast off of flavor.

COONEY: Yeah, this is much closer to the rocket family part of arugula than the general arugula you buy in the store.

O'NEILL: So what do we owe you now? 10 bucks for the lettuce, and how much for the arugula?

COONEY:10 bucks for the lettuce, and the arugula is free.

O'NEILL: Well, I think we're all ready to head out. Thank you again for showing us around.

COONEY: Oh, you're welcome.

FEINSTEIN: Thank you so much.

COONEY: Thanks for coming. I appreciate everyone's time.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill and Jay Feinstein with farmer Shawn Cooney at the shipping container called Corner Stalk Farms.

Related links:

- Corner Stalk Farm

- Freight Farms, the creators of the shipping container farms used by Corner Stalk

[CUTAWAY MUSIC:Secret Garden/Davy Spillane, “Pastorale” on Songs From a Secret Garden, by Rolf Lovland, Philips]

Saving West Africa’s Last Rainforest

Lawyer Alfred Brownell fought and won against Golden Veroleum Liberia’s attempts to take over indigenous land and wreck West Africa’s largest remaining tropical rainforest without due process. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: The winners of the Goldman Environmental Prize each year are nothing if not courageous.

Many risk their lives to protect endangered species, rare natural resources, and indigenous land rights.

Lawyer and human rights advocate Alfred Brownell of Liberia is the 2019 African Goldman recipient for his work to save over 800,000 acres of Liberia’s Upper Guinean rainforest from development into massive palm oil plantations.

This rain forest and carbon sink is the largest in the region and nicknamed the “lungs of West and North Africa”.

It’s a biodiversity hotspot and home to many indigenous people.

Attorney Brownell’s conservation efforts nearly cost him his life as he battled Liberian government officials and the palm oil company, Golden Veroleum Liberia.

And after he found a way to block the financing of the project he was forced to flee with his family to the United States, where he is now serving as a Distinguished Scholar at Northeastern University’s School of Law in Boston.

Alfred Brownell welcome to Living on Earth.

BROWNELL: Thank You, it’s a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: You’ve risked your life to protect this forest, please tell us why you were willing to risk everything to guard it against the palm oil plantation folks?

BROWNELL: What more of an honor it is to fight for this planet, to fight for this forest, to fight for a way of life of people who are preserving it? It's a life worth giving. If no one is prepared to lay their life down, to fight to preserve Mother Nature, to protect this planet, to ensure that generations unborn will come and have a safe and healthy environment, and clean water and soil that is not poisoned by agrochemicals, and species in nature that are protected, that allow for generations unborn to perpetually and continually serve. If you're not able to give your life for that, then what cause you are able to stand up for? So I think I was always prepared to give that life, and even now I'm prepared to do that. The sort of threat we now face because of the way our forests and landscape are being destroyed, that is now warming of our planet, that is now creating the sort of challenges that the world now face -- drought, flood, forest fires, mass migration, poverty, and conflict. If the world and the planet is not worth the battle, if you are not able to stand up and allow yourself to be counted, and put your life on the line to fight for that, what else are you prepared to give your life up for? What is the meaning of your life? What is the meaning of your purpose on this planet?

Now living in exile in the United States, Brownell teaches at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Locally, in Liberia, why is the conservation of the Upper Guinean forest essential to the preservation of the local people who are there, the indigenous folks who are there, and their culture?

BROWNELL: If you flew over Liberia, all you see is the vast expanse of forests. It's like you are flying over an ocean of trees, green in color. It's actually one of the wonders of the world, to just see a continuous span of trees going over. And all that one will feel and think is that, these are just trees. And below them these are just animals. But a forest is also your home, to indigenous people. It represent their history, their culture, their tradition, their way of life. They refer to the forest as their supermarket, this is where they go and get the food. They refer to the forest as their pharmacy, this is where they go and have its medicinal plants. They refer to the forest as their university, this is where they teach the young people about the way of the tribes and the culture; how to become farmers -- and sustainable farmers; how to develop indigenous business enterprises. So over the years, they've learned how to coexist their life with nature, in a very sustainable way. That's why this forest is important. But much more than that, this is the last refuge of what west Africa once used to look like. If you went back in the times in West Africa, it was completed green across the entire region. Completely green, it was completely blanketed in green forests. The only portion of that blanket of forest in that entire region is what we now have in Liberia. It's the only intact forest. In other countries, they are all fragmented. So that's why it's important to protect this forest. It's the largest carbon sink in all of North and West Africa.

CURWOOD: So when you got concerned about this in a public way, what happened when you started speaking out against the Golden Veroleum Liberia company, these are the folks that want to do palm oil plantations, and you used your training as an attorney to, to launch a legal advocacy campaign against that firm. What happened to you?

BROWNELL: [LAUGHS] Well, of course they were not happy. I mean, this is a multi billion-dollar investment that has come. And the Government of Liberia had signed away massive amount of land. Think about that, 350,000 hectares of forest. That's as almost like, almost 800,000 acres of land, to this company. The government had not consulted the communities; the government had not even gone to do any kind of mapping of the land area. You know, it's how, you know sometimes elites in many other countries, you know, don't have respect for locals who have lived on this land, and just give this land to this company. And they went ahead and you know, said well, we have authority from the government and we want to take the land. And started to evict folks and clear away the land. And so my attention was drawn to what was happening. And I went and I saw what has happened; I was shocked, because I have seen entire towns and villages, completely bulldozed, by these companies. I have seen stream and creeks poisoned. I've seen people shrines, religious sites, their gods -- desecrated. I have seen people's burial grounds of their great warriors, their tribal chiefs, those who establish their towns and villages -- and like in the US it's talking about someone going in and desecrating the graves of -- what's the first president?

CURWOOD: George Washington.

BROWNELL: George Washington. And I'm wondering what Americans will say about that. Or it's like, to the African American, someone going and trying to desecrate the grave of Martin Luther King. What would they say about that? This is what these companies were doing to those people. Their entire history, their value, their way of life, their culture, their very essence, what made them indigenous people, was under threat and attacked by these palm companies.

Liberians discussing the threats oil palm developments are bringing to their land and indigenous communities. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: So what did you do?

BROWNELL: So I had to act. So the first thing we did was, well, we felt, maybe this has been done out of ignorance, maybe there wasn't an awareness, the government didn't know about this. So at the local level in the region, we informed the local authorities, government officials; we moved into the cities; we went from ministries and agencies of the government to complain; organized massive press conferences, to draw attention. No one cared. They were in deal with the companies and was taking on destruction.

CURWOOD: So we're talking about the motivation of money here.

BROWNELL: Absolutely. This was not a venture that was intended to fail, it was too big to fail. This was intended to transform Liberia into a desert of oil palm. So we had to find a way to organize. The plan was to challenge just the grant of the rights, on the basis that the government of Liberia had no authority to give the lease rights to a transnational corporation, on land that indigenous people have existed on and occupied, even before the existence of Liberia.

CURWOOD: But how do you stop that? I mean, if the government is going to rule on any complaint that you bring forward, they're in charge of this process.

BROWNELL: Absolutely. Given how the government was involved in this process, and given that they ignored all of the pleas that we made, we felt that if we had gone to court, we probably wouldn't have prevailed.

CURWOOD: So what's the answer?

BROWNELL: And then a friend of mine said, Well, you know, Golden Veroleum is a member of an international consortium called the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, which is a certification body to ensure that palm companies were engaged in the sustainable production and marketing of oil palm.

CURWOOD: So your strategy is, this palm oil company needs to certify their palm oil as sustainable, because there are great concerns about this from Indonesia to West Africa. And so you went to this certification agency to tell them, uh-uh, this ain't sustainable.

BROWNELL: But certification is not just about a label that would give to them, you have to understand what the label means to the companies that are involved in the production.

CURWOOD: Okay, what does it mean?

BROWNELL: Because, given what has happened in Southeast Asia, given the alarming nature of how palm oil companies are operated in Indonesia and Malaysia, and the impact on the forest, and the species and orangutans -- it's creating alarm, it's creating concern, among activists, environmentalists, and social activists, and among consumers, and they demand for more sustainability. So it meant that many palm companies were not even having the financing to engage in production and to engage in the marketing. So they needed this label, to show to the banks, to investors, to shareholders, to their suppliers, to the consumers, that indeed they can get the financing to do this. And so we filed a complaint. We actually said, "We are open to an independent assessment and verification of the allegations we made." And they took the bait.

Alfred Brownell’s position at Northeastern University has given him a new platform and resources with which to fight oil palm developers’ attempts to take indigenous lands. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Ooh.

BROWNELL: Yes.

CURWOOD: So they came and investigated.

BROWNELL: Of course.

CURWOOD: And they found?

BROWNELL: And they found that we were right, every single bit. This is very important for our audience to understand what this is, because sometimes many folks will pitch this as development. How come poor villagers, living in misery and poverty, will have concerns about a multi-billion-dollar investment coming to their community, why are they opposing that? Don't they want a better way of life? But what many people don't understand is how this occurred on the ground. So imagine Golden Veroleum, for example -- a multi-billion dollar, the second-largest palm person in the world, going to poor villages. These villages, before the palm came, had their own palm. They had indigenous palm, they had their food crops, and the company wanted that. So the women, for example, had planted oranges, that they would sell every year, between the harvests. An orange tree will produce anywhere from between 8 to 12 bag of oranges. A bag of orange will sell for 10 U.S. dollars. So if a lady was able to harvest a tree of oranges, and had 12 bags, it meant that she had 120 U.S. dollars in her pocket. She would have that to support she and her family and her kids. The oil palm companies came and they didn't want that. They took away that tree, and guess how much they paid this woman.

CURWOOD: Nothing?

BROWNELL: 20 U.S. dollar per tree. Per tree. Not even the economic or market value. So what development is that, that will further impoverish people who already, out of their bootstraps, have engaged into entrepreneur activities? And so we had to act. And so, when those were established, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil wrote them and said, you have to stop further clearing, further development, and sit down and negotiate with these villagers.

In addition to a monetary prize, Goldman Prize winners each receive a bronze Ouroboros sculpture. Common to many cultures around the world, the Ouroboros, which depicts a serpent biting its tail, is a symbol of nature’s power of renewal. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: We're speaking with Attorney Alfred Brownell, Goldman Environmental Prize winner from Liberia and we'll continue with his story of protecting West Africa’s largest old growth rain forest after the break. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jerry Leake, “Children’s Song” on Vibrance: Jazz Vibes and World Percussion, by Chick Corea, RhombusPublishing.com]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We continue our conversation now with Alfred Brownell, the Goldman Environmental Prize winner from Africa who saved West Africa’s largest rainforest from palm oil development. In the middle of the fight the palm oil company allegedly tried to have Attorney Brownell killed.

The six 2019 Goldman Environmental Prize recipients participated in a ceremony on Friday, April 26th. From left: Belén Curamil Canio of Chile (on behalf of her father, Goldman recipient Alberto Curamil); Jacqueline Evans of the Cook Islands; Alfred Brownell of Liberia; Linda Garcia of Vancouver, Washington; Bayarjargal Agvaantseren of Mongolia; and Ana Colovic Lesoska of North Macedonia. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BROWNELL: And they try, they try to assassinate me, you know, their private securities. And this is very emotional.

CURWOOD: Tell me this story, what happened? Talk to me about the day that you understood that the assassins were coming for you What happened that day?

BROWNELL: Do you really want to hear this story?

CURWOOD: Yes, people should know.

BROWNELL: It's very personal... it's very personal. But you know, as a defender, I also know that there are many others who were not lucky like me, to be sitting down before you to tell this story. Many of my people, the communities I come from, as environmental and rights defenders, have paid the ultimate price. And bowed down and gone to see their ancestors. People like Berta and others, Ken Saro-Wiwa and others, who have died. And so in as much as this is very painful, I have actually made a commitment that I can be their voice, to keep echoing what, what this really is: the danger the defenders are facing. So as you will know, they were very angry. Now they have the stop order, and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil had instructed them to sit down and negotiate, develop a work plan and obtain the consent of communities. So they figure out that well, this certification board is based in Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. We are in Liberia in remote villages; we can ignore what they said and continue to do this. So part of our job was to investigate their compliance with this order. So when they told them to stop, they did not stop. They continue to take the land. They build much more strong relationship with the government. They pressure the government to put more pressure on us. So that's where the threats started to come in, from the government to us. That's where we're being labeled as anti-country, anti-development, anti-investment. My very citizenship was being questioned, that I was not a patriotic Liberian. How dare I challenge an investment that will build the infrastructure and generate revenue and create employment. But we kept reporting back to the certification body that Golden Veroleum was not following their order. And so they organize the first fact-finding mission ever done by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil to a country to ensure that one of his members was actually following their instructions. So when the team came to Liberia, we took them to a place called Tarjuowon, in Sinoe County. It was in fact an area where, after the stop order was issued, Golden Veroleum had identified that it would build a mill. It was on a hill which was referred to as Palloh Hill. This was a shrine, a religious site, of the Blogbo people in Sinoe Tarjuowon, the indigenous people, who every year, would go and pray and pay homage to their ancestors. It was so revered; it was so sacred. And this was where the company decided that they would make it the site for their mills. And so the local decided to show this to the fact-finding mission. So we went in, and we proved, we actually met the earth-moving equipment that were tearing down these shrines. And when I turned around to look at these community people, some folks just dropped on the soil. People were just crying, they were just crying, they just couldn't believe that their religious site, their shrine, had been completely torn apart. So unknown to us while we're doing that inspection, assessment, Golden Veroleum and maybe some actors in the government had decided that, well, we are really going too far. And that would have been the last day I was taking my breath, and so on our way back, as we came out of the operation area, we enter a town called Sinoe Town. We came across a group of men and there was a massive roadblock, they had logs on the road. And then our cars were all surrounded by these men. And they were going around shouting, "Where's the lawyer? Where's this lawyer, we are looking for Brownell! Where's the lawyer, we are looking..." And so they were searching for me. And then one of the guys said, "Here is Brownell." And then there was a shout from the crowd, they were so happy that they found their prey. And then, you know, they started threatening and trying to open the car doors, trying to puncture the tires, knocking the glass. These men were all dressed in the company uniform, they had the coats, they had the working tools from the company. And they started dancing, "Well, today is your last day." They were happy. Then I noticed that some other folks were sharing alcohol. So folks started to drink, they started to beat drums. And then some folks stared to put chalk, the traditional war dance -- in Liberia they have to the traditional war dance that the tribes would do.

Aerial view of an oil palm monocrop and the remaining forest in Sentabai Village, West Kalimantan, Indonesia, in 2017. (Photo: Nanang Sujang / CIFOR, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: You put chalk on your face.

BROWNELL: Chalk on your face. And some of the leaders came to the car and said, Well, you know today is going to be your end, you're never going to stop this company anymore. You know, we are going to, to eat your heart. We're going to take out your heart and eat it. And then someone say in fact, my boss is waiting for your skull. You know, he's going to turn it into a mug, he's going to drink his palm wine from your skull. And I was just being taunted, back and forth, they were dancing. And it was not easy. The colleagues who were in my car had all like given up. Some of the folks in the vehicle had already fainted. So I didn't know what to do. I just kept praying, what will happen? And I was just waiting for my time. Then they said, "Well, let's get the chief." Now this local chief was actually on the side of the company, we knew that he was one of the persons who was being paid by the company. It meant that if he gave his order, it meant that that was the end for us. So they went and they brought the chief. And he reached my vehicle and he knocked my windshield and said, "Roll down," -- I rolled down. And the chief said, "Are you Mr. Brownell?" I said, yes. He looked at me, and he said, "These people want to kill you. But I'm the chief. I don't know how that's gonna happen." And he turned around and said . . . [CRYING] he told them, he told them, "I'm not going to let you kill this man here. I'm not going to let you kill him. This blood must not waste on my land; this blood must not waste on my land. If you want to kill him take him to another town, but I am not going to allow you to kill him, and this blood will not be on my land." Then a young man who stood by him was very angry, and then he assaulted the chief and hit the chief. Then some of the young people from the village got angry that the chief had been assaulted. And there was conflict. The chief said, "Ah, so you insulted me. Then I'm going to remove the roadblock, and this car's going to go." And you know, they went and were fighting over the logs, tried to move that. And then we managed to flee the area. And we went to another village, where we stopped in a place called Buto, where we started our original campaign. And the company guys tried to chase out there and the Buto people came and said, "We're not going to allow you to touch our lawyer." We stay there for like, five days, protected by the indigenous people. Every night a movement from one house to another house in the night; people don't know who or where they would come but just like as in customs, trying to locate me. But the tribes protected me through all the time. And then they found a way to provide safety along the road back to the city. And we went, we came back to the city, we complain, we issue press statement. Couple of months later, my office strangers burglarize. I had electronic gadgets in my office, no one tried to take them away. There were DVDs, and phones, cell phones; I even had some money, some petty cash on my desk. No one took the money.

CURWOOD: What did they steal?

An oil palm stem, weighing about 10 kg (22 lb), with some of its fruits picked. (Photo: T.K. Naliaka, Flickr CC BY-SA 4.0)

BROWNELL: Documents, financial records. Then I started having strange vehicles following me. And then five years of bank records from my organization was taken. There were stories written to the media saying that I was corrupt, that I was using donor money to create a slush fund for myself. But I continued to persevere. And to be honest with you, I felt that it was worth the fight. It was worth the battle. And like I told you earlier on, if I faced the same attack again, I would go on. . . I'm embarrassed when I have to tell this story.

CURWOOD: Why?

BROWNELL: Because it makes me look like I'm weak.

CURWOOD: Courage is weak?...

BROWNELL: But I feel that it's important for the world to hear it. Because like I said before, I'm lucky to live, but I want the rest of the world to know what this is about. That an ingredient that you wouldn't even notice if you walk into your supermarket or grocery store, or you bought a bottle soap, or you bought chewies, or you went into McDonalds and you bought your fast food, or you went to Kentucky Fried and took your fries and your chickens. Or if you're someone who love lipstick, who buy lipsticks; or you love ice creams. You have no idea that oil palm is all over you. It's all over you. And while you are enjoying this -- both beautifying yourself and enjoying the flavor that it brings, and the happiness and joy that it brings to you and your family on this side of the world, it was raining destructions on another side of the world. So while you are beautifying yourself as a lady, there were women who were being flogged, who were being stripped naked, and chained in prison. There were the history, there was a culture, there was a religion, there were the shrines of people who have been desecrated. This is what the palm oil was doing to that country.

CURWOOD: So ultimately, of course, you felt that you had to leave. That it was just too much for your family and yourself and you came to the United States. But I imagine that the Liberian government is still trying to pursue this deal, still trying to pursue palm oil development, and other threats to the Upper Guinean forest. So now, from here in America, what kinds of legal or political strategies do you think could be used to protect the forest now from this development?

Orangutans in Borneo are quickly losing their habitat to oil palm developments. (Photo: Andrea Schieber, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BROWNELL: Well, so sometimes folks believe that they are threatening you. And maybe that's how the government of Liberia and the palm companies felt, when I left Liberia they felt they had won a victory with my removing, and they can do business as usual. But I think now they realize it was the biggest mistake in their life.

CURWOOD: Because?

Many if not most packaged products Americans consume contain palm oil. It’s found in lipstick, soaps, detergents and ice cream. (Photo: Rain Rabbit, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

BROWNELL: It was here in the US, it was here at Northeastern University School of Law. When I came and Northeastern University offered me a refuge and gave me a platform, a desk to continue my work in dignity. That's the idea -- when you go into exile, you lose everything. I left Liberia, just in one suit. The day my office was attacked by the police on the raid, I was not able to go back to my office, neither to my home. My family left in just the clothes they had on; I had to grab my kids, friends had to help me to take my wife and my kids along with me out of the country. And quickly fly me to a third country before I came to the US. But here in the US, at Northeastern, I had a platform. I had a group of students who was involved in my research, who are supporting with research. I had professors who were assisting me, I had an office, I had 24-hour electricity. I had 24-hour fast speed internet.

CURWOOD: So you can tell the story.

BROWNELL: So I could sit down and tell the story. I could sit down and continue to put pressure on the certification body. It was here that when the company launched its appeal against our complaint, that they lost. People put a lot of pressure on them. And so it was in August of 2018, a year and a half later, of sustained engagement, both supporting the communities directly in Liberia from a platform here in the US, using WhatsApp and other social media, working directly with the coalition head office that we were able to counter the appeal, and we won. And it is from here that I will continue pursuing those cases, to make sure that they are not going to take away that forest.

Alfred Brownell and his kids sharing a moment of fun in the snow. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

CURWOOD: Alfred Brownell is the founder and lead campaigner of Green Advocates International and this year's recipient of the African part of the Goldman Environmental Prize. Professor Brownell, congratulations. And thanks for coming by.

BROWNELL: Thank you. It's a pleasure.

Related links:

- About Alfred Brownell, 2019 Goldman Environment Prize recipient

- Watch: Alfred Brownell’s Goldman story

- Listen to our conversation with co-recipient Linda Garcia

- Listen to our conversation with co-recipient Jacqueline Evans

Since this story first aired last year Sime Darby, one of the 2 companies Alfred Brownell was fighting against in Liberia have pulled out of the country.

That leaves half a million acres of rainforest undeveloped, for now.

Locals are working to permanently protect the forest for communities in the region.

As for Mr. Brownell, he is now a visiting faculty at Yale Law school and working on climate change issues in West Africa.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eddie Pennington, “Over the Rainbow” on Eddie Pennington Walks the Strings…and Even Sings, by Harold Arlen/E.Y. Harburg]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

we tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Steve Curwood

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth