September 18, 2020

Air Date: September 18, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Black & Latinx Voters Lean Green

View the page for this story

Surveys suggest Black and Latinx voters, along with younger voters, are more likely than white voters to view the environment and climate as their top concerns. However, due to both voter suppression and an enthusiasm gap people of color are less likely to exercise their right to vote. Pete Maysmith, Senior Vice President of Campaigns for the League of Conservation Voters, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how his organization plans to help mobilize Black and Latinx votes this November to boost pro-environment candidates. (09:51)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s look beyond the headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss a new law passed in California which will allow state inmates who have been fighting wildfires while serving prison sentences to get jobs in those same firefighting organizations upon their release. Later in the segment Peter and Steve take a deeper look at the climate costs of plastic manufacturing, and finally, their powers combine to celebrate the 30th birthday of Captain Planet, the blue-skinned, green-haired cartoon environmental champion. (05:17)

World’s Largest Wetlands on Fire

View the page for this story

As wildfires blaze across the West Coast of the U.S., Brazil grapples with its own fires, in its massive Pantanal wetlands and the Amazon rainforest. Host Steve Curwood speaks with biologist Daniel Nepstad, President of the Earth Innovation Institute, about the role of climate change in the wildfires and how they’re impacting Brazilian biodiversity, ecosystem services, and local communities. (15:11)

BirdNote®: Thick-Billed Euphonia: Deceitful Mimic

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

DECEITFUL MIMIC: The Thick-billed Euphonia is a songbird in South America who uses its power of vocal mimicry to hoodwink other birds into chasing off predators. BirdNote's Mary McCann reports on this tiny trickster. (01:41)

Spirit Run: A 6,000-Mile Marathon Through North America’s Stolen Land

View the page for this story

Every four years a 6,000-mile marathon run called Peace and Dignity Journeys unites Indigenous runners from all over North and South America, seeking to heal the wounds left from colonization and displacement. In his memoir Spirit Run: A 6,000-Mile Marathon Through North America's Stolen Land, Noe Alvarez shares how the communal run helped him reclaim a relationship with the land and reconnect with his parents' migration and life of labor in the agricultural fields of the Northwest, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about the journey. (15:47)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Noe Alvarez, Pete Maysmith, Dan Nepstad

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Massive wildfires in the Amazon and Pantanal wetland in Brazil are global threats.

NEPSTAD: If a significant chunk of the Amazon rainforest is destroyed it's going to be a lot harder for us to avoid the extreme impacts of climate change let alone the more guaranteed very dangerous impacts of climate change. So it's a big deal.

CURWOOD: Also, an indigenous marathon run from Alaska to Argentina brings healing to native communities.

ALVAREZ: You know a lot of the indigenous communities when they are able to honor the land in their own terms it's very much with deep respect. It's coming back to it and having a conversation with it and celebrating it and bringing people to the land and passing down stories that are very empowering, and that's the kind of land that I want to be proud of.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Black & Latinx Voters Lean Green

Above, former Vice President Joe Biden, the 2020 Democratic nominee for President. Pete Maysmith says mobilizing green-leaning voters of color could change the outcome of the upcoming Presidential election. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

If the past is any guide, more a third of eligible voters in America won’t cast a ballot in the closely watched November elections, and that is why environmental advocates and others are pushing get out the vote efforts. When it comes to the environment, research shows Black and Latinx voters, along with youth, are more likely than white voters in general to list the environment and climate as top concerns. Yet thanks to obstacles to voting and an enthusiasm gap, Black and especially Latinx voters are less likely to exercise their right to cast ballots. But if green leaning voters of color are mobilized to match white turnout, it could change the outcome for candidates who favor environmental action, and that’s why the League of Conservation Voters is spending millions to rally Black and Latinx voters. Pete Maysmith, Senior Vice President of Campaigns for LCV, joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MAYSMITH: Really glad to be here. Thanks so much for having me.

CURWOOD: So given that polls show that Black and Latinx voters care much more about the climate and environment than other groups, what's LCV's strategy for mobilizing these voters to get them out to the polls?

MAYSMITH: So we're really at LCV doing two things, Steve. First off, focusing on mobilizing and turning out young people and voters of color. That obviously includes in very significant numbers, Latinx and Black voters. Because we know that when they turn out, on balance, will support pro-environment, pro-climate change candidates. So talking to them this year, especially in this moment, given that so much of our voting is going to look and be different given the pandemic that we're in the middle of. And then the second thing that we're doing that we can talk a little bit about, if you'd like to, is also some persuasion, some longer term conversations. We want to make sure that Latinx and Black voters are choosing to vote for a pro-environment candidate -- in this case, of course, that's Joe Biden as we look at the Presidential ticket -- and making sure that they understand just how awful Donald Trump has been, he's been an environmental disaster as President.

Across the country, voters of color are less likely to turn out to the polls than white voters (Photo: Jamelah E., Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So another factor that the folks at the Environmental Voters Project did was look at what motivates people to vote to get out there. And at the end of the day, it's fairly emotional, they say, and actually the biggest way to motivate the demographics we're talking about here, Brown, Black and, and youth, is peer pressure. That if somebody in a social group is voting and makes a bit of noise about it, that's the most likely thing to persuade somebody else to get out there and vote. To what extent are you looking at emotional factors such as the peer pressure phenomenon?

MAYSMITH: Well, absolutely, Steve. I mean, first off, there's all sorts of methods and ways to connect in with voters and to talk about what their neighbors are doing, what their colleagues are doing, other family members are doing. So texting somebody, reaching out, you know, writing a letter to somebody, you know, connecting in some way to somebody to say, Hey, I'm voting, you should vote too. And then also higher profile influencers, whether it's, sometimes it's media stars and sports stars, we've seen LeBron James really step up in this regard, for example, talking about the importance of voting and why they're voting. It's sharing their story, is often very powerful to help motivate people to vote.

CURWOOD: So there are probably, you know, 6, 7, 8 states where the Presidential race is likely to be decided. And one of the most interesting right now appears to be Florida, which has a high Hispanic population. And if one believes recent polling, and of course polling has its strengths and weaknesses, Joe Biden is not getting the kind of response from Latino voters that he gets, let's say from Black voters. They, Latinos seem to be split about evenly right now, according to the recent polls. Given how important Florida is, given how much Florida is at risk from climate disruption, how are you trying to break through with Latino voters there?

MAYSMITH: So Steve, I think that's a great question. And so there's a couple things that we're doing, really knowing that there's a heavy concentration both of Latinx voters and of a high concern around climate change, is reaching into the state with messages that speak directly to what Trump has done. And this is, I think, an important point; in particular, in the moment that we're in with the pandemic, research that we did in the springtime and summertime showed that linking Trump's inaction and more importantly denial of the pandemic, along with inaction and denial of climate change, ignoring the scientists, tearing down the institutions that are designed to keep us safe, in both instances, right? And then how that has negative consequences and outcomes for you, your family, your neighborhood, and your community, again, in many, many instances, this is a prime example of environmental injustice, rearing its head. And so we've made those linkages and told those stories through digital ads and through direct mail to these voters in Florida.

Pete Maysmith, Senior Vice President of Campaigns for the League of Conservation Voters. (Photo: Courtesy of LCV)

CURWOOD: I'd like to play a clip here. This is the, the Democratic Presidential nominee Joe Biden in a speech on September 14, from Wilmington, Delaware.

BIDEN: If we have four more years of Trump's climate denial, how many suburbs will be burned in wildfires? How many suburban neighborhoods will have been flooded out? How many suburbs will have been blown away in superstorms? If you give a climate arsonist four more years in the White House, why would anyone be surprised if we have more of America ablaze.

CURWOOD: Pete, I don't think I've ever heard a Presidential nominee use that kind of language on climate, with Joe Biden calling Donald Trump a "climate arsonist." How strongly do you think that is resonating with voters?

MAYSMITH: Well, I think it is resonating. And I think in part that's why Biden used that language, and I think it's going to continue to resonate. You saw him tie it to the suburbs, right? Because Trump's been trying to pretend that if you live in the suburbs, you know, you'll be in peril, your life will end, the suburbs will somehow be destroyed and disappeared, which I don't remotely understand, if Biden were to be President. And but Biden is saying no, this climate arsonist, right? We have climate fires, we have climate floods, we have climate hurricanes. That's what is the real threat, again, to you and your community and your loved ones and the people in your orbit. That's the real threat. Voters want someone to react to that. And that's why Joe Biden's using that language, and good on him for doing that.

CURWOOD: And how could Joe Biden craft his language that speaks more directly to Black and Brown and younger people, because, you know, the suburban thing that President Trump has been talking about is a code word for, look out, white people in the suburbs, the Brown people are coming for you. What could or should Joe Biden say that speaks more directly to the Black and Brown?

MAYSMITH: Well, I think a couple of things. I mean, one should just, just be really direct and we've seen some of this from Joe Biden, that what is happening to Black and Brown communities as a result of environmental injustice, it is connected to racial injustice in this country, period, full stop. Communities that are, you know, have to live next to coal plants or, you know, facilities that dump toxic sludge into waterways or spew toxics into the air are predominantly, more than not, Black and Brown communities. That's why in part that you see higher rates of asthma and other disease and other illnesses in those communities. And so making that direct linkage and naming that, I think there's a lot of power, Steve, in naming that and saying that.

An LCV campaign ad geared toward Spanish-speaking voters. (Photo: Courtesy of LCV)

CURWOOD: Pete, we want to get back to you to talk in more detail about the Senate races, but briefly, which of the key Senate contests do you think are going to turn on the response of Black and Brown voters, at the margin of course?

MAYSMITH: Of course. In Michigan, Gary Peters, an incumbent Senator, big pro-environment champ, we want him back to cast pro-environment votes in the US Senate; Black voters are going to play a really important role in that race to help making sure that Gary Peters is reelected to the Senate and defeats his anti environment opponent. And then looking to Arizona, Mark Kelly is looking to unseat an anti-environment Senator. Her name is Martha McSally. And of course Arizona has a high number of Latino voters, high percentage of Latino voters, and so Latino voters are going to play an absolutely vital role in that US Senate race in Arizona. North Carolina has got a really tight hotly contested Senate race, Cal Cunningham is a pro-environment champ. Heavy influence of Black voters in North Carolina, virtually all everything we're doing in that state is targeted to Black voters to support and turnout for whether it's Joe Biden or Cal Cunningham. So those are three US Senate races: Michigan, Arizona, and North Carolina, Steve that I would highlight where voters of color are gonna be really important to the outcome.

CURWOOD: Pete Maysmith is Senior Vice President of Campaigns with the League of Conservation Voters. Pete, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

MAYSMITH: Absolutely, Steve, I really enjoyed the conversation. You have a great show and thanks so much for having me on.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure.

Related links:

- Read more about the League of Conservation Voters here

- Listen to our previous interview on "The Environmental Voting Gap"

- Register to vote

[MUSIC: Keb’ Mo’/Mermans Kenkosenki/Tal Ben Ari “Tula”/Vusi Mahlasela/et al, “One Love” on Playing For Change – Songs Around the World, by Bob Marley, Hear Music Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Over 2000 California State Prison inmates have been deployed on work-release to fight the raging wildfires, and a new law would allow them to get jobs with the state’s firefighting services upon their release (Photo: Carlos Cortés López, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: And joining us now from Atlanta for a look at the world beyond the headlines is Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and daily climate.org. On the line now, Hi there, Peter, how you been?

DYKSTRA: I'm doing all right, Steve. What I want to talk about to start today is just an awful situation with wildfires. California has always had sort of an auxiliary of firefighters that come right out of the state prison system, this year there are about 2000 inmates that are cleared to work as firefighters along with the feds, the Cal forestry people and others. There's a bill that was just signed by Governor Gavin Newsome, that would make it easier for the inmate population once they get out of prison to have their records cleared so that they can work full time with their day jobs as firefighters.

CURWOOD: Okay, sounds like some progress.

DYKSTRA: It is indeed it doesn't really allow for inmates to take part in every part of firefighting, for example, they can't work as EMTs. But they can work out in the heat in the flames in the smoke, along with their counterparts, who do it professionally. Now, all of this training and experience that those inmates acquire in these hellacious fire seasons we've seen can be put to good use as they rejoin society.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: There are a couple of reports out from nonprofits in recent months about the impact of plastics in climate change. Plastics, of course, are petroleum based products. One report estimates that plastic production over 10 years would be the equivalent of 300 new coal power plants in terms of their impact on the Earth's climate. The oil industry is looking at the eventual demise of its main products for oil and gas extraction, they want to make sure that plastics, even if fossil fuels go away, that plastics don't. And that's a lifeline to the oil and gas industry.

CURWOOD: And of course, plastic is more than just a carbon problem then, I mean, it winds up everywhere.

DYKSTRA: It's a carbon problem, we've seen information coming out in the past few years about plastic rain, micro particles of plastics that actually go up in the atmosphere fall back to Earth, getting soil potentially impact our crops, and of course, the deep impacts that we've seen, not just on water quality, with the Pacific Ocean plastics blob, every freshwater stream in the country and in the world has a huge and distressing amount of plastic waste poured into it which eventually makes its way to the ocean. It's a mess and one that we're finally beginning to get a little bit of a grip on.

CURWOOD: And you know, we shouldn't be so surprised about this. I mean, it takes millions of years to convert plant matter into hydrocarbons into coal and oil and such. So the fact that these compounds last for a very long time, in any form is like kind of basic chemistry. Hmm.

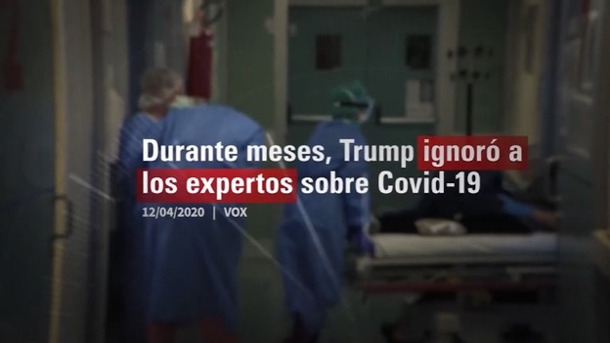

Captain Planet inspired a generation of environment-defending planeteers, and also pulled off several improbable outfits. (Photo: Mark Anderson, Flickr, CC by 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We're talking basically for the functional equivalent of life as we know it on Earth. Once we make those plastics, they're here forever, whether it's in a landfill, in our bodies, or in our waterways.

CURWOOD: Alright, Peter. Well, you started with good news. I guess this is not such wonderful news about plastic, but maybe when we turn to take a look at history, I can get a smile.

DYKSTRA: Well, you can get better in the smile, you can get a birthday party for Captain Planet, September 15 1990, the first episode of the animated action feature with Captain Planet and his blue skin and his green hair, maybe with a little bit of gray in it now. 30 years ago. They stopped original production a while back, but Captain Planet is still in syndication and still having an impact on now a couple of generations of kids who learned some of their first environmental knowledge from a cartoon.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra, thanks so much. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News that's EHN.org and daily climate.org we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: The power is yours, Steve.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the living on earth website LOE.org

Related links:

- Politico | “California clears way for inmate firefighters to enter profession upon release”

- Click here to read more about the climate implications of expanded plastic production

- Learn about some of the origins of Captain Planet

- Read about the Captain Planet Foundation, the spinoff charity arm of the children’s environment-centered cartoon

[MUSIC: Theme from “Captain Planet,” by Tom Worrall/Timothy Mulholland/Murray McFadden on Toon Tunes, Kid Rhino Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – As fires rage across America’s west coast, Brazil’s Pantanal, the largest wetland in the world, is also endangered by massive widlfires. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Charanga Cakewalk, “Melodica” on Chicano Zen, by M. Ramos, Triloka/Artemis Records]

World’s Largest Wetlands on Fire

Satellite imagery of the wildfires in the Amazon rainforest (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[Pantanal sounds]

CURWOOD: The Pantanal in South America is the largest wetland in the world. It lies mostly within Brazil on the Southwest border of the Amazon rainforest and at more than 42 million acres the Pantanal is roughly the size of Florida. Home to jaguars, the endangered maned wolf, and more than 650 species of birds the Pantanal is an ecological jewel. The World Wildlife Fund for Nature recently reported that in the past 50 years more than two thirds of animals have been lost around the planet, and in South America and Caribbean animal numbers have declined by more than 90 percent, making the Amazon and the adjacent Pantanal key refuges. In the Amazon rainforest farmers burn to open space for crops, a practice that degrades the rainforest. In the grassland Pantanal ranchers generally have used fire responsibly to clear dead forage during the annual dry season. But this year the equation has changed. Historic drought has led to out of control wildfires, and these record setting blazes have already scorched 20% of the Pantanal. For more I’m joined now by biologist Daniel Nepstad, president of Earth Innovations Institute. He’s also a lead author for reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Dan, welcome to Living on Earth!

NEPSTAD: Thank you. It's wonderful to be here.

CURWOOD: The Pantanal is teeming with biological diversity please describe some of the animals and plants that live in this sometimes wet sometimes dry land.

NEPSTAD: Yeah, I've lived for 12 years in the Amazon forest region and in that time, I've probably seen a Jaguar or five times in the wild in the middle of the forest. In the Pantanal I've been there a few weeks, and I've seen dozens of jaguars, dozens of giant anteaters, capybaras, caiman, these alligator reptiles. Sometimes you'll come up to a lake, you'll be riding a horse through the Pantanal on one of these Pantanero ranches, and there'll be 100 cayman, you know, five feet long lined up along a pond. It's just the wildlife blows your mind it’s just everywhere. I was crossing a little stream I noticed that there is this peculiarly shaped log in the stream and it was an anaconda that was about 25 inches in it's thickest spot it's probably where it ate a capybara. So it's it's just teeming with wildlife because with that seasonal rhythm of flooding and ebbing of the river, you get tremendous productivity of grasses of aquatic plants of fish. Piranha are very common there. The hyacinth macaw, the world's largest macaw that's its biggest population in the Pantanal giant river otters, the jabiru stork is very common there, the marsh deer. So it's just there's 1200 different types of vertebrates there and many of them are rare. A lot of them are not on the brink of extinction, just because there is a lot of intact, Pantanal remaining, and many of the species do leak over into some of the surrounding biomes.

The Pantanal wetlands are rich with biodiversity, and filled with jaguars. Unfortunately, the wildfires are threatening their existence. (Photo: Martha de Jong-Lantink, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Dan, it's the world seems to be burning up right now. We've got fires raging across the West Coast where you are as well as in Brazil, specifically in the Pantanal wetland, the largest wetland in the world. We'll talk more about the fires in a moment. But please, could you describe the Pantanal wetlands and why it is burning up right now?

NEPSTAD: Well, the Pantanal is, as you say it's the world's largest wetland and it's a seasonal wetland so that in the rainy season, the Paraguayan and Paraná Rivers fill up with water and they flood most of the Pantanal. And so the cattle herds at the Pantanal are literally wading through water and the cowboys with horses wading through water as they they ranch the Pantanal, they graze, the Pantanal and then the water goes down and it gets really dry and that's when the fires come in.

CURWOOD: So this year I gather is worse than others. What are we looking at right now?

NEPSTAD: We're looking at the the worst drought hitting the Pantanal and in about half a century, 47 years and river water levels are way down, the wells are drying out. And because of that the vegetation that can usually still tap into the water that's in the soil below the ground surface is parched. And when it's parched, and the temperatures are high, it catches fire and those fires get out of control very easily.

Brazilian wildfires are threatening capybara communities native to the Pantanal wetlands. (Photo: Martha de Jong-Lantink, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent are these fires intentional?

NEPSTAD: Well, the Pantanal has got a culture called the Pantanero culture. It's mostly cattle ranchers, who have adapted their cattle management systems to this seasonal rhythm of the rising and ebbing flow of the river and part of that management system is burning. And they will burn the pastures when the risk of the fires is not too high, and a lot of these are native grasslands. And it's really quite a sustainable system. The problem is when you hit that system with an extreme drought, like this year where the fires are starting, not just from those pasture management fires set intentionally, but they're being set accidentally and fires escaping their intended boundaries. So it's what is usually a fairly controlled fire burning season that's part of the the, the pasture management this year, it's just gone haywire. They can't control the fires.

CURWOOD: And by the way, why does fire manage the grasslands?

NEPSTAD: In the Pantanal system. So these grasslands get flooded every year they get a little injection of sediment from the river that brings in some nutrients and it goes down and when you burn the pasture, you get rid of the old growth, the woody shrubs that are invading the pasture. And the grasses come back greener and you can actually get better cattle production off of those recently burned pastures. If you don't have that input of river sediments every year, then the fires are actually a loss of nutrients and it's really running down the fertility of the soil. But in this case, it works pretty well.

Illegal deforestation on Pirititi Indigenous lands of the Amazon rainforest. Since 2018, over 4 million hectares of land have been cleared. (Photo: Brazilian Environmental and Renewable Natural Resources Institute, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Dan, what is the relationship between the Pantanal and the Amazon rain forest and what are the links, if any, in terms of the fires?

NEPSTAD: Yeah and so first of all, the Amazon if you think of the the northern part of South America, you've got these trade winds coming in from the east blowing West they take in all this moisture, then they cross the Amazon and that wind picks up more moisture. The wind hits up against the Andes and it either bends north or bend south. The airmass Is that bend South carry that water vapor into the Pantanal and into the Sahado Woodlands of Central Central South America and therefore they're a big source of rainfall. So there's a water connection between the Amazon in the Pantanal that's quite strong. A portion of the watershed of the the Pantanal the Cuiabá River for example that comes in to the Pantanal is draining it reaches up into the edge of the Amazon. The fires themselves first of all, there's a huge difference, the Amazon forest naturally burns about every five to 700 years. In other words, pre Colombian times that was the rhythm. It's a very unbelievable and infrequently burned forest. It's just so damp the canopy is so dark, so dense and I've set hundreds of fires Amazon forest as a scientist, and they almost always go out immediately, you know, they can burn for maybe a minute. It's just soggy and what happens during an extreme drought event is that sogginess disappears and it sounds more like a main forest walking through a main forest and the rustling of leaves, and those forests become flammable. And that happens every few years and it's more and more frequent and that's what we're seeing this year in the southern part of the Amazon. The Pantanal In contrast, is really mostly a large grassland and grasslands every year you can set on fire. In fact, much of the Pantanal is burned for the pantanero cattle management systems which rely on mostly native grass, although some African grasses are being planted there as well. So you've got a the Pantanal burns naturally and through cattle management and the forest there tend not to burn. And because the management system keeps those fires out of the forest, but they are flammable and this year, they're burning, everything is burning.

Satellite imagery of cross-country wildfires in the Amazon rainforest. (Photo: NASA, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: How concerned are you about this level of burning in the Pantanal now?

NEPSTAD: I think the really impactful way we're experiencing climate change is through these crazy fires, fires that are burning out of control because the vegetation is parched. And the temperatures the winds, the dry lightning like we had and here in California, are just much more frequent and higher and more intense and more violent. And in the Pantanal, the connection to climate change is not as direct it's really a warming of the tropical Atlantic Ocean north of the equator. That's part of this longer multi-decadal oscillation that we've had since the 90’s but climate change is feeding into that. In fact, climate change may be one reason we have this Atlantic oscillation, and it could be that it, it makes it stick around longer. And so it's a complex change underway. But what's really frightening to me and just living in this smoke here in California, and being part of a fire evacuation a few weeks ago, our lives are changing because of climate change. And this is a taste of things to come.

CURWOOD: Let's talk for a moment about the Amazon as a whole. I think it's safe to say the Amazon is the world's largest tropical rain forest and it's a huge carbon sink. I believe that it absorbs what on the scale of 5% of annual carbon emissions and puts out as much as 20% of the planet's oxygen. How does all this fire activity affect the Amazonian rainforest, ability to be a carbon sink?

NEPSTAD: The Amazon as you say, It's just in the trees of the Amazon, there's about 100 billion tons of carbon. And when that carbon is turned into carbon dioxide through burning or through decomposition, that means that there's a potential of nearly half a trillion tonnes of co2 in the Amazon forest. That's about a decade's worth of human caused carbon pollution today, if a significant chunk of the Amazon rainforest is destroyed, it's going to be a lot harder for us to avoid the extreme impacts of climate change, let alone the more guaranteed very dangerous impacts of climate change. So it's a big deal.

An increase in drought is making the Amazon rainforest more vulnerable to fires. (Photo: Doug Morton, NASA)

CURWOOD: So to what extent are you telling me that if we keep going, we're going to hit a tipping point where the Amazon and for that matter, other forests will become grasslands? How true is that and if so, where are we right now do you think in that process?

NEPSTAD: So there's really good science showing that when you clear the forests, you get less rainfall. And the big question is at what scale? We already have evidence that temperatures are rising and rainfall the dry season is longer in the eastern, southeastern part of the Amazon where most of the deforestation has taken place. And the big question is, are we going to reach a level where there's so much clearing that the entire Amazon rainfall system is inhibited so that there's not enough water, rainfall to get those forests through the dry season each year? And that is a bit up for grabs. You know, some scientists some models show we would hit that threshold. At 40% loss. We're at 17% currently, others say it's 25% others say it actually is not going to happen. There's some model experiments that do not give us a tipping point. I think the precautionary principle would say, what we need to do in the Amazon is slow deforestation and end it and reverse it. And there's actually a huge opportunity to do that, by in the case of Brazil, where we have two thirds of the Amazon forest, implementing the law 51% of the forests of the Amazon are protected in some way. Let's make sure those indigenous territories and parks are really well managed and not being invaded. 80% of every farm in the Amazon is supposed to be set aside as native forest. Let's make sure that the farmers who want to do that and are doing that are recognized and rewarded in some way. And currently, they're not if I'm a farmer in the Amazon, and every hectare of forest on my farm is going to be worth one fifth the value of the cleared area I have. And so the more I clear, the more value my farm has, and I'm thinking of passing this along to my kids, right? The value of that same Hector of forest $200 in the land market is $50,000 in damages done to the global economy, if it's cleared. And so that should be one of the easiest things to solve in the world, right? Where we can keep a hectare of rainforest standing by closing the gap between $200 and $1,000 when it's clear, that needs to be called out.

CURWOOD: Daniel Nepstad is president and founder of Earth Innovation Institute. Dan, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

NEPSTAD: Steve, it was my pleasure. Thank you.

Editors Note: The Amazon rainforest does not produce 20% of the world's oxygen. The Amazon rainforest accounts for 20% of the land's surface photosynthesis on the planet but it consumes as much oxygen as it produces.

The biggest contributor to Earth's oxygen supply is actually the ocean.

The Amazon is a crucial carbon sink, meaning if it were to completely burn, atmospheric CO2 concentrations would increase by around 10%.

Learn more at the link below.

Related links:

- About the Earth Innovation Institute

- Daniel Nepstad’s NY Times Op-Ed | “How to Help Brazilian Farmers Save the Amazon”

- CNN | “Tens of thousands of fires are pushing the Amazon to a tipping point”

- National Geographic | "Why the Amazon doesn't really produce 20% of the world's oxygen"

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Thick-Billed Euphonia: Deceitful Mimic

The Thick-Billed Euphonia is a songbird native to South Africa. (Photo: © Brennan Mulrooney)

CURWOOD: Bird calls can serve many functions. Attract a mate, defend a territory and as BirdNote’s Mary McCann reports fool a neighbor.

BirdNote®

Thick-billed Euphonia - Deceitful Mimic

[Northern Mockingbird song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/94375, 0.07-.14]

Northern Mockingbirds, the continent’s most proficient copycats, can learn to mimic the sounds of just about any other bird within earshot.

But they mimic to show off, not to deceive. Males with the greatest repertoire are the first to attract mates — that’s the payoff. If a mockingbird imitates a cardinal song, it is unlikely any cardinals are fooled in the process. No harm, no foul, no deceit intended.

[Thick-billed Euphonia song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/199537, 0.04-.08]

But a tiny songbird in South America called the Thick-billed Euphonia does employ what scientists call “deceitful mimicry,” a very rare trait among birds. When frightened by a predator near its nest, a Thick-billed Euphonia imitates the alarm calls of other birds nesting nearby. This stirs them into action, and they rush in to harass the predator, maybe chasing it off while leaving their own nests in peril. [Thick-billed Euphonia song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/199537, 0.04-.08]

The euphonia, meanwhile, sits tight.

Maybe shouting out a few more bogus alarms, while others do the dirty work.

The Euphonia mimics the distress calls of other birds when a predator is nearby. (Photo: Felix Uribe, CC)

###

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Northern Mockingbird [94375] recorded by W L Hershberger. Thick-billed Euphonia recorded by David L Ross Jr.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org June 2015/2020 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# TBEU-01-2015-06-24 TBEU-01

[Thick-billed Euphonia song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/199537, 0.04-.08]

Sources: http://www.bl.uk/listentonature/specialinterestlang/langofbirds8.html

http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/wilson/v088n03/p0485-p0...

https://www.birdnote.org/show/thick-billed-euphonia-deceitful-mimic

CURWOOD: For pictures flock on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org

Related link:

Listen to this story on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Entrain, “Right Away People” on No Matter What, by T. Major/J. Fuller/R. Lovot, Dolphin Safe Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – An indigenous relay run from Alaska to Argentina aims to heal the land and hearts. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Biff Smith, “First Rain” on Biff Smith Solo Piano, by Biff Smith, Callipygous Music (self-published)]

Spirit Run: A 6,000-Mile Marathon Through North America’s Stolen Land

Peace and Dignity Journey runners gather to bless the ceremonial staff before they set out on their daily run. (Photo: Courtesy of Jose Maldivo)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Every four years a marathon run called Peace and Dignity Journeys unites Indigenous runners from all over North and South America. Runners begin from opposite ends of the Americas: Chickaloon Alaska and Tierra del Fuego Argentina. The ending point can vary year to year but each leg meets somewhere in the middle. Noe Alvarez joined the run in 2004 as a way of reconnecting with the land and honoring his parents' lifelong struggles working as immigrant fruit packers in the agricultural community of Yakima, Washington. In his memoir 'Spirit Run' Noe shares how the pilgrimage helped him heal his relationship with nature and reconnect with his indigenous heritage. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: Give us a little bit of your own personal background, if you will, and how that influenced your decision to run.

ÁLVAREZ: Yeah, so my background, I'm still trying to figure out and I, you know, my parents are from Mexico, they immigrated to the United States to be laborers in the state of Washington. So they worked in the apple orchards in the fruit packing warehouses while I grew up. And, you know, that was my reality. My reality was very much working on the land and, and being, you know, told by my dad, my father, that you know, the land was a bad thing you needed to get out of it, because what it did to my people, and what it meant to work on the land. So for me, my reality was getting out and I didn't know what that look like and trying to be better than my dad, right? Because he wanted me to be different from him. And, you know, I was born and raised in Yakima, Washington and very small town and immigration had an impact on my life, you know, and so for many years, we were running sort of away from things away from fear. Running was a bad thing and so when I came across this run, it was an opportunity for me to reconnect in ways that I wasn't able to, spiritually, to be amongst other people who are talking beautifully about their emotions, about their flaws, but the things that needed to be worked through and I didn't have that going on. We just communicated through our hands and our hard work so Peace and Dignity Journeys was a sort of a second chance for me to reconnect with the child that I couldn't be when I was younger.

BASCOMB: Now you had a difficult time growing up, and then you actually ended up getting a free ride to college to Whitman college, but you had a hard time there and then ended up dropping out in order to participate in the PDJ. Can you tell me about that decision please?

ÁLVAREZ: Yeah, so I got accepted to Whitman College in Walla Walla, and that was a great moment in my life, right? My whole life is always just get into college, get into college. It was never what do you do once you get in because I don't think I ever believed that I would get into college here. Here I was finally able to save my family that was the narrative. You know going to college meant saving your family, making the money, making that whatever and then I finally got there and it was the war to college and it was just so much catching up to do and it was a culture shock, every step of the way. It was very difficult to sort of find my footing find my ground and so when I finally got there, I sort of had a meltdown, you know, especially since I felt like I was leaving my people, like literally I was, I was gone. I was, you know, I couldn't sit with the fact that I had made it here I was in college, while my parents and my people were still laboring away, stuck back home and no real out for them and so I had a lot to contend with. And peace and dignity sort of gave me the alternative language for me to learn the way my people learn, which is through migration, through the land movement about the land and I wanted to honor my parents migration, you know, I was I sort of wanted to reengage in that experience that they had and sort of retransform what it meant to migrate.

BASCOMB: I'd love for you to read a passage from your book. If you don't mind it starts on page 71, the third paragraph down.

ÁLVAREZ: I punch my arms into the air and beat my chest like I did along the Nachis River, reviving this human flesh into action. The wing cracks branches around me like a whip, whipping me into shape. In this isolation, I take the opportunity to shout it down, to scream at the ugly things inside of me as loudly as possible. I yield to make my speech physical to give my words muscle and to build the strength necessary to speak to things I never could. I run to follow as closely as I can the path of those who came before me, migrants who knew suffering and deprivation. I run to find fragments of my own parents sprinkled over the earth, artifacts their stories of hope and desperation. In facing these things I tried to find the bringing in to the suffering that has haunted me in childhood. I want to learn how to embrace my past, where I come from, and to love myself again. Finally, I feel in this forest on a path toward become free.

BASCOMB: Can you describe a typical day on the run for us please?

ÁLVAREZ: Every day was different, the typical routine was we would open up with ceremony and close with ceremony. So we would wake up before sunrise and you know, close, ideally when the sun was setting and we would have sort of a ceremony around the staffs that we carried. We carried ceremonial staffs that represented specific prayers, specific land, specific territories that people had donated to the run, to keep in mind when we ran and so there was a staff that would be dedicated to, to rain and to certain people who suffered from drought or a certain feather that an elder had donated for their youth who are struggling with drug addiction and a specific mom who wanted us to pray for a child who was in prison. And so these were the sort of staffs that we carry with us and every morning, who pick up a different staff, whichever one we wanted to pick up during the day. And when we carried those staffs it was sort of a kind of a visual reminder of the burden that we carry right? And of the power that we carry and you know that we're not alone. And so you know, we would sleep with the community territories in the region, we’d have ceremony and food with them and, and just engaging in talking with them and listening to what they had to say to us and what they wanted us to carry forward. So it was about just literally, you know, being messengers for the next community and telling them hey, the next community before you know, wants you to know that they're with you, and that they believe in you and so we were just trying to, you know, build that fire. So we, you know, we scrambled for food, you know, we were welcomed by numerous communities. They gave us what they could camped out a lot. And so we're very thankful what they could offer and we carried what we could every day.

Peace and Dignity Journeys has taken place every four years since 1992. It is an arduous journey during which runners average about 70 miles a day. (Photo: Courtesy of Hector Cerda)

BASCOMB: You know the way you describe it the runners going through all of these different communities it sort of reminds me of your like a needle and thread sort of stitching together a quilt made of two pieces and trying to hold it together. How do you see it?

ÁLVAREZ: Yeah, no, that's exactly it and part of the thing that I want to communicate in this book is that that's the beauty of this run that there was so much difficulty and so many obstacles still and we came at it from very different lifestyles a lot of us. A lot of us had our own traumas, our own histories, our own, you know, stitch work but the thing that we agreed on was that we came to put in the work around running specifically. So wherever you were coming from, that was a common ground. And that's what I try to write you know that there's a lot of pain and I don't want to shy away from that but I think I wanted to find some beauty and some strength. And then I wanted to put out an amplify a voice for people who are going through the same things, who might find power in these narratives, where not everything is resolved but that doesn't mean that the world is over right? It means that we're all human. There's a lot of beauty in the messiness of human nature, right? And so I just wanted to put it out there, especially as a male Latino where I personally didn't have very much model around articulating weakness articulating what it meant to be man, what it meant to be vulnerable, and what it meant to just, you know, love yourself. And that's sort of what I'm still trying to do.

BASCOMB: Well, let's talk a little bit about the physical act of running. It sounds really grueling at times, there are long days, a lot of miles and just a little food and you had some injuries along the way and some of the other runners are kind of difficult to get along with. What kept you going through all that and and how difficult was it?

ÁLVAREZ: It was extremely difficult. You know, you had to remind yourself why you were doing right? And it had to be some powerful It had to be something stronger than just calories stronger than just the competitive spirit. You know, it's not a competitive run. And I think what kept me going were the stories, right? Every day you were running through a different community. And every day you were meeting people who had something very special to say, you know, and it was that, that was what you want it to run. You were literally running to the next story. And so, you know, everyday you were running for a different reason. You know, one day I'd be running from my dad, my mom Sometimes the smell of a certain region helped me recall memories that I didn't want to confront when I was younger, there was a lot of healing for me on the run. But if you were doing it just for a competitive nature for sort of calorie burning or whatever, you wouldn't last. You had to tell yourself because it was, you know, it defies all logic, right? Like, why are you doing this? Why are you inflicting so much pain? And so you had to tell yourself you know, I was doing it for my family, I was doing it for me, I was doing it for these communities and you know, there's people who are counting on you to finish. There’s people counting on you to spread that message and, you know, you can't take that responsibility lightly. When someone shares something special and profound, and personal, so deeply personal about their, their history and their family you just can't displace it, you just can't dishonor it, you have to sort of put in really like the commitment to you know, running to the next community.

BASCOMB: So there's obviously a lot of personal healing in this but I understand another goal of the run is to bring healing to the land, and you pass through many, many sacred Native American sites including, you know, remote mountains in the middle of nowhere and downtown Los Angeles. Can you tell us about that and the different feelings that those places about out for you?

ÁLVAREZ: Yeah, it was. It was an amazing, an amazing experience. And it was it was really interesting how, you know, we we weren't running with technology at the time, we were literally going through with maps and navigating the areas. We were relying on indigenous elders to take us through ancient routes through trails that hadn’t been gone through for a while, and oftentimes the names of the communities where referred to as their indigenous name the names of their origin. So for the longest time, I didn't know where it was right, because they weren't referred to the the names of the big cities, right, because those were cities that conquered those those names that sort of oppressed them and so they were asserting their individuality and the reality and augmented by preserving the name of their land. So only until we reached the cities like Los Angeles or Portland or Vancouver BC that I was able to orient myself, oh, this is where I am. But it was sort of this magical middle ground because I was completely, you know, immersed in the land with the people who have such respect for the land and celebrated of the land and sang to the land and danced to it. And so, I felt like I was in a different world and that was the world that I wanted to be in. So connected, profoundly connected with the land and, and having a conversation with it, as opposed to how I grew up with the land, which was working it, you know, today, you know, tailing it, you know, and harvesting it, using it as a product to cultivate apples and just destroy the land at times. And then you know, it would destroy you too you know. You're working long hours for such low pay, and they weren't the best conditions and always worried about immigration coming in to you know take your parents away. It was it was a fear, you know, that that all of us had, that we were used, and then when we were no longer needed you know, be disposed of, and so there's a lot of fear around. So we couldn't celebrate the land the way we wanted to and my dad growing up almost made quite a profound connection to the land to down there but you know, his conditions didn't allow him to sort of sit with it the way you want it to. And so, here finally having the privilege of being born in the United States and being able to travel, I made it a mission to sort of sit with that and figure out what the lounge would be to me and I wanted to create a conversation that will last for generations in my families now that there's a conversation, a solid conversation about landscaping in our family, reclaiming it in our story.

Each runner carries a ceremonial staff gifted by Native American communities. Noé Álvarez can be seen on the far right of this picture. (Photo: Courtesy of Hector Cerda)

BASCOMB: You know, we had a guest on a while back. My name was Leah Penniman and she said something that really always kind of stuck with me. She said that nature, you know, the land is the scene of the crime, it’s not the crime itself. Now, she was talking about African Americans and slavery, but how relatable is that sentiment to you and to maybe some of the other runners.

ÁLVAREZ: Oh, that's, that's very beautiful and I think, I think very well put. I think that's very accurate that I always loved the land right when I was a young kid it's only as I grew older, and through the stories and my father that I learned the violence inflicted upon it, and just the suffering upon it. And so it was really conflictual to me to feel so much love for a land it was you know, eroding my people, my dad and had warped our sense of connection to it. That's how I wanted to transform my experience. I knew there was always some beautiful and special in the land I enjoyed running through the fields when I was younger, it's only when I had to sort of learn the trade that I too started feeling the same way I felt betrayed by the land betrayed that I I was only good for, you know, my own physical strength, I was only good for the product that I was able to help my dad produce. And so, but that was that was on someone else's terms and you know, a lot of the indigenous communities, when they are able to honor the land on their own terms, it's very much with deep respect. It's coming back to it in and not just having the land but it's having a conversation with it and celebrating it and bringing people to the land and passing down stories that are very empowering, that give you strength. That’s the kind of land that I want to have, that I wanted to be proud of. We all need a sacred space in the land is always been a place that’s made me happy. That's given me centeredness and I couldn't have done that I don't think without a community of Peace and Dignity Journeys, with people who have been working on it for generations. And so to lose something like that would be profoundly detrimental to our society, in our community in our landscapes. So we got to, we got to start introducing new stories and asserting how the land is a very powerful medicine for us.

CURWOOD: Spirit Run author Noe Alvarez, speaking with Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- New York Times | “Running Thousands of Miles in Search of Yourself”

- Learn more about Peace and Dignity Journeys

- The Fresno Bee | “Native American Runners in Valley on Alaska- to Panama Journey”

- More about "Spirit Run: A 6,000-Mile Marathon Through North America's Stolen Land"

[MUSIC: Nahko And Medicine For The People, “Give It All” on Take Your Power Back, SideOneDummy Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth