October 23, 2020

Air Date: October 23, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Environmental Justice Debated

View the page for this story

The second and final 2020 U.S. presidential debate featured climate and the environment more prominently than ever before in a general election debate, with environmental justice discussed for the first time in such a forum. Hosts Steve Curwood and Bobby Bascomb talk about some of the debate highlights on environmental topics, from “fenceline communities” plagued by pollution, to Donald Trump’s claims about wind energy, to Joe Biden’s plan to phase out fossil fuels. (04:53)

Climate and Senate Races in North Carolina and Georgia

View the page for this story

Since the 1960’s North Carolina and Georgia have favored Republican candidates, but Senate races there this year show a tight race between Republicans and Democrats. More climate awareness and the growing number of young people migrating to these states is changing the electorate there. InsideClimate News Reporter Marianne Lavelle joins Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to look at how climate politics is affecting the North Carolina and the Georgia special election Senate races. (08:19)

Rapid Ice Melt and Rising Seas

View the page for this story

The Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets are melting at alarming rates thanks to climate change, and will continue to do so for decades even if the Paris Climate Agreement goals are met. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Princeton University climate scientist Michael Oppenheimer about how these massive ice sheets contribute to global sea level rise, and why their melting necessitates both the reduction of global warming gases and adaptation to protect vulnerable coasts. (08:55)

Overcoming Climate Anxiety

/ Jenni DoeningView the page for this story

Climate change is disrupting lives and causing deep anxiety, especially for the young people organizing to address it. The new book A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet lays out strategies for addressing climate-fueled anxieties and moving beyond them to help Gen Z activists envision a resilient future. Author Sarah Jaquette Ray joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering for a virtual live event to discuss the importance of equipping young activists with the emotional tools they need to bring about change. (09:12)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood take a peek Beyond the Headlines to look at the New York Power Authority's decision to convert some of their “peaker” plants to clean energy. Then, the two cross the pond to Finland, where a recent study suggests that childhoods spent playing in the grass and dirt might help strengthen immune systems. Finally, they take a trip back in history to the anniversary of Toyota's Prius prototype. (04:27)

Hiking in 6-Inch Heels

View the page for this story

Growing up as a queer person, photographer Wyn Wiley was often told: The great outdoors is for everybody, but only if you look and act a certain way. Now, he works to break down this barrier. His drag queen alter-ego, Pattie Gonia, hikes in 6-inch heels and a full face of makeup, preaching on Instagram that enjoying the outdoors transcends gender identity and sexual orientation. Wyn Wiley speaks with Bobby Bascomb as Pattie to discuss her journey as a queer environmental activist and the solace she finds in nature. (10:24)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

201023 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood and Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Pattie Gonia, Marianne Lavelle, Michael Oppenheimer, Sarah Jaquette Ray

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Environmental justice in the Presidential debate, and how climate change is shaping Senate races in North Carolina and Georgia.

LAVELLE: One of the things that you’re seeing in both of these states is a lot of migration of young people. It's just not acceptable for these new immigrants to North Carolina and to Georgia to deny climate change.

CURWOOD: Also, a chat with an environmentalist drag queen on making nature more accessible for all.

PATTIE GONIA: When I do drag in the outdoors I feel the most me. And yes, that means literally backpacking in high heels, which you can think is a very silly and stupid and dangerous thing but so is riding a mountain bike down a mountain at 45 miles an hour. So you know, pick and choose your danger in the outdoors. I just choose to wear six inch heels.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Environmental Justice Debated

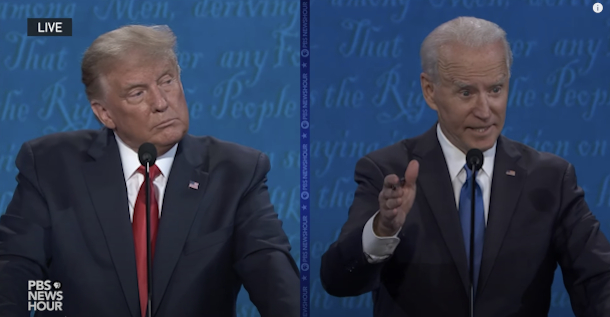

During the final presidential debate of the 2020 election, Joe Biden talked about his $2 trillion climate plan and getting the U.S. back into the Paris Climate Accord, while Donald Trump blamed countries like China, Russia, and India for “filthy air.” (Photo: PBS NewsHour debate coverage screenshot)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Well Bobby, the second and final live Presidential debate before the elections once again touched on the climate crisis, and broke some new ground on environmental justice.

BASCOMB: Yes Steve, and nothing like a mute button and a strong moderator to make it possible to hear those points.

CURWOOD: So let’s listen to some excerpts of the debate, starting when Joe Biden pointed to quote good paying jobs unquote in the wind and solar industries, and the rapid growth of solar. Donald Trump had a sharp retort short on facts.

TRUMP: I know more about wind than you do. It's extremely expensive. Kills all the birds. It's very intermittent. It's got a lot of problems and they happen to make the windmills in both Germany and China and the fumes coming up, if you're a believer in carbon emission, the fumes coming up to make these massive windmills is more than anything that we're talking about with natural gas, which is very clean. One other thing, solar-

BIDEN: Find me a scientist who says that.

President Trump attacked wind energy as “extremely expensive” and “very intermittent” and falsely claimed that wind turbine production creates more carbon emissions than using natural gas to generate electricity. (Photo: Jeffrey G. Katz, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

BASCOMB: Well, in fact president Trump’s own scientists in US fish and Wildlife service says the bird deaths from collisions with wind turbines are a tiny fraction of birds killed by cats, as well as collisions with buildings and power lines.

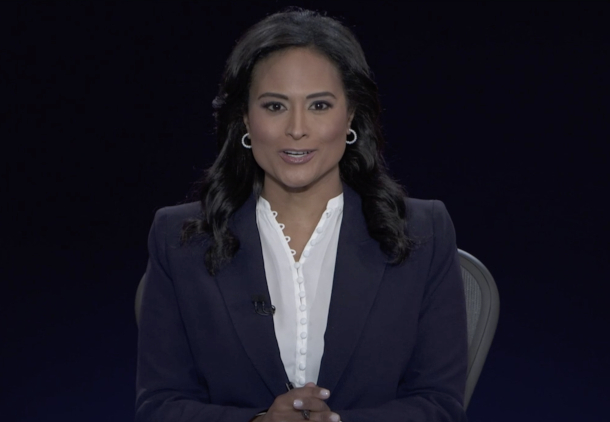

CURWOOD: And then after some back and forth on fracking moderator Kristen Welker brought up a topic never heard before in general presidential election debate, environmental justice.

WELKER: President Trump, people of color are much more likely to live near oil refineries and chemical plants. In Texas, there are families who worry the plants near them are making them sick. Your administration has rolled back regulations on these kinds of facilities. Why should these families give you another four years in office?

TRUMP: The families that we're talking about are employed heavily and they are making a lot of money, more money than they've ever made. If you look at the kind of numbers that we've produced for Hispanic, for Black, for Asian, it's nine times greater the percentage gain than it was under in three years than it was under eight years of the two of them to put it nicely, nine times more. Now somebody lives, I have not heard the numbers or the statistics that you're saying, but they're making a tremendous amount of money. Economically, we saved it and I saved it again a number of months ago, when oil was crashing because of the pandemic. We saved it. Say what you want about relationship. We got Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Russia to cut back, way back. We saved our oil industry and now it's very vibrant again and everybody has very inexpensive gasoline. Remember that.

WELKER: Vice President Biden, your response and then we're going to have a final question for both of you.

BIDEN: My response is that those people live on what they call fence lines. He doesn't understand this. They live near chemical plants that in fact, pollute, chemical plants and oil plants and refineries that pollute. I used to live near that when I was growing up in Claymont, Delaware and there are more oil refineries in Marcus Hook and the Delaware River than there is any place, including in Houston at the time. When my mom get in the car and when there are first frost to drive me to school, turning the windshield wiper, there'd be an oil slick in the window. That's why so many people in my state were dying and getting cancer. The fact is those frontline communities, it's not a matter of what you're paying them. It matters how you keep them safe. What do you do? And you impose restrictions on the pollutions that if the pollutants coming out of those fence line communities.

In his response to the moderator’s question on environmental justice, Joe Biden talked about the “fenceline communities” who face harmful pollution from nearby industries. (Photo: photos.de.tibo, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: There was far less interrupting during this debate compared to the last one, but there was plenty of jabbing nonetheless.

WELKER: Okay. I have one final question called.

TRUMP: Would he close down the oil industry?

WELKER: It falls-

TRUMP: Would you close down the oil industry?

BIDEN: By the way, I have a transition from the old industry, yes.

TRUMP: Oh, that's a big statement.

BIDEN: I will transition. It is a big statement.

TRUMP: That's a big statement.

BIDEN: Because I would stop.

From left, Democratic Nominee for President Joe Biden, moderator Kristen Welker, and President Donald Trump on the debate stage. (Photo: PBS NewsHour debate coverage screenshot)

WELKER: Why would you do that?

BIDEN: Because the oil industry pollutes, significantly.

TRUMP: Oh, I see. Okay.

BIDEN: Here's the deal-

TRUMP: That's a big statement.

BIDEN: Well if you let me finish the statement, because it has to be replaced by renewable energy over time, over time, and I'd stop giving to the oil industry, I'd stop giving them federal subsidies. You won't give federal subsidies to the gas, oh, excuse me to solar and wind.

TRUMP: Yeah.

BIDEN: Why are we giving it to oil industry?

TRUMP: We actually do give it to solar and wind. That's maybe the biggest statement. In terms of business, that's the biggest statement.

WELKER: Okay.

TRUMP: Because basically what he's saying is-

WELKER: We have one final question, Mr. President.

TRUMP: ... he is going to destroy the oil industry. Will you remember that Texas? Will you remember that Pennsylvania, Oklahoma?

NBC anchor Kristen Welker was widely praised for her skillful handling of the second debate between Donald Trump and Joe Biden. (Photo: PBS NewsHour debate coverage screenshot)

WELKER: Okay, Vice President Biden, let me give you 10 seconds. Okay.

WELKER: Vice President Biden, let me give you 10 seconds to respond-

TRUMP: Ohio.

WELKER: ... and then I have to get to the final question. Vice President Biden.

BIDEN: He takes everything out of context, but the point is, look, we have to move toward net zero emissions. The first place to do that by the year 2035 is in energy production, by 2050 totally.

CURWOOD: Bobby, for me the takeaway from this second debate is the new place climate change has on the list of public priorities. It’s not if but what to do. And I think it’s fair to say whichever man wins this election pressure will be on to fight climate disruption.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “Biden Says the U.S. Needs to Move off Oil to Tackle Climate Change As Trump Attacks the Plan’s Cost, Economic Impact”

- Grist | “Biden Schools Trump on Environmental Justice During Debate”

- Learn more from NAACP about the harmful pollution fenceline communities experience

- Carbon Brief on the “insignificant” carbon footprint of wind energy compared with gas

- Watch the final 2020 Presidential debate

- Watch the presidential debates here, courtesy of C-Span

Climate and Senate Races in North Carolina and Georgia

Democrat Cal Cunningham is running for the North Carolina senate seat. Picture by Grayson Barnette. (Photo: Grayson Barnette, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: You can see climate now in the senate elections as well this year, in several key races.

CURWOOD: Yeah, Bobby, we’ve covered a lot of these battleground states before and today, you have something for us on North Carolina and the Georgia special election, we already covered the contest between David Perdue and Jon Ossoff.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I talked with Marianne Lavelle, a reporter for Inside Climate News, about these two races in the South, where Democratic candidates are becoming more and more competitive. And once again, there’s increasing focus on climate change and environmental justice. I started by asking Marianne about the Republican incumbent in North Carolina, Senator Thom Tillis, and where he stands on climate change and the environment.

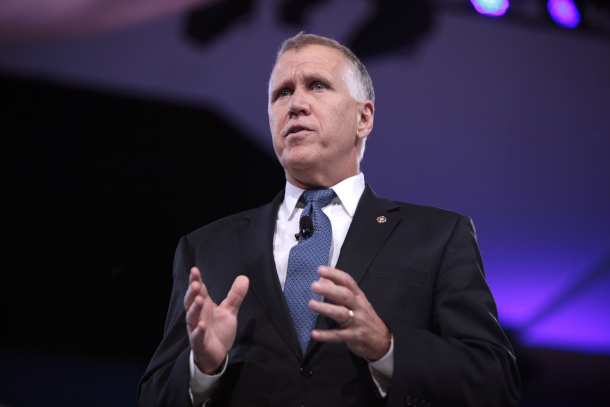

Republican North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis has changed his perspective on climate change since he was elected in 2006. Previously he denied the existence of climate change and was a strong proponent of offshore drilling but recently he has expressed openness to “market-based solutions”. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY ND 2.0)

LAVELLE: Well, Thom Tillis is kind of the example of a Republican who's trying to evolve his position on climate change. When he was first running for senate six years ago, like all of the other Republicans he was running against, absolutely said he just doesn't by that climate change is happening. And very early on, he was really unabashed promoter of fossil fuel development, including drilling offshore of North Carolina. Well, since then, North Carolina has been hit by five hurricanes, which all you know, in various ways have caused a lot of damage in the state. And the coastal counties even though a lot of them are Republican they are not in favor of offshore drilling at all. And it was kind of easy for Thom Tillis to be in favor of offshore drilling six years ago, when President Obama was in it wasn't going to happen but with President Trump he was moving forward on offshore drilling. So fast forward to today, he kind of took credit for the Trump administration's decision just a few weeks ago to say, we're going to back off on offshore drilling for a few states, including North Carolina. And so Thom Tillis is still in line with the republican position on energy. He votes very, very closely in line with President Trump on almost everything, and he has a very low score from the League of Conservation Voters on his Environmental record, but he is talking about himself as someone who cares about climate change. He just doesn't want to hurt the economy.

BASCOMB: Well, let's talk now about his challenger, Democrat Cal Cunningham. He served in the US Army Reserve and as a North Carolina State Senator. And he recently put out a campaign ad that shows North Carolina getting pummeled by hurricanes. And he links that to climate change. Let's have a listen to that ad:

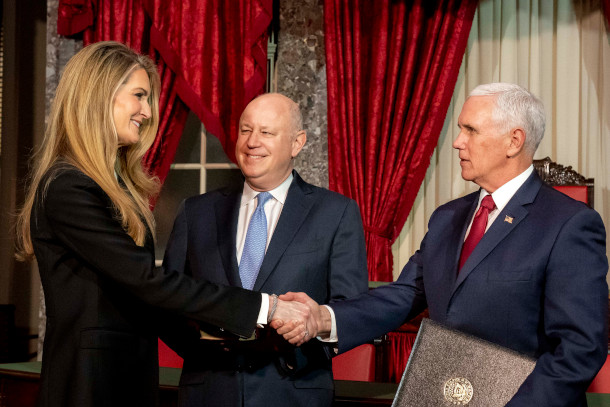

After Republican Senator Johny Isaacson stepped down at the end of 2019, Republican Georgia Governor Brian Kemp appointed Kelly Loeffler as successor. The image above shows Vice President Mike Pence swearing in Kelly Loeffler in January 2020. (Photo: D. Miles Cullen, Public Domain)

CUNNINGHAM: [AMBIENT MUSIC] Taking on climate change is going to be a priority of mine. Because of the impact it's having right here on North Carolina.

VOICES: That is not lightning, those are transformers blowing out. . .

This storm is so immense . . .

CUNNINGHAM: But the size of the storms, we can't deny it. Twice in the last two years, 500 year floods, devastating large portions of our state. [AMBIENT MUSIC]

LAVELLE: What's really interesting about that ad is it's not that common for the candidates themselves to feature climate change in their ads, especially in a very purple state like North Carolina, where the Democrats are trying to appeal to the moderates. They're not just going after progressives. So really to make this strong statement on climate change by Cunningham is a statement of how much traction the issue has in North Carolina. He definitely backed strong environmental legislation when he was in the North Carolina legislature. He also was a business person who worked for a consulting company that helps companies reduce their waste. So that also gives some some green credentials.

Republican Doug Collins is running for the Georgia Senate seat against 19 other contenders. (Photo: Office of Congressman Doug Collins, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: Well, let's turn now to Georgia where there are two seats up for grabs. We covered the race between incumbent Senator David Perdue and Jon Ossoff a few weeks ago on the show, but there's also a special election in Georgia to permanently fill the seat of former senator Johnny Isaacson who had to step down last year because of illness. That seat was temporarily filled by Republican Kelly Loeffler. What can you tell us about her environmental record?

LAVELLE: Right? Well, Kelly Loeffler has voted 100% with President Trump. She has a very, very solid record with him. She has voted against things like renewable energy, you almost hear her kind of echoing the rhetoric of the White House on many controversial issues and I would expect her to do the same on climate.

BASCOMB: Well, Senator Loeffler is up against some 20 challengers in this special election. Let's look at just a couple of the front runners starting with Republican Doug Collins. Now both are Republicans, as I said, but how do they compare and contrast on these issues, if at all?

LAVELLE: Well, Doug Collins, again, very, very closely aligned with President Trump. He's very conservative. He doesn't talk about climate change, but you could expect him to be very much in line with the White House on climate change. That has kind of been his pitch. The really interesting person is Reverend Raphael Warnock.

BASCOMB: Hmm. He's the leading Democrat in the race, according to polls, what can you tell us about him?

Reverend Raphael Warnock, a Democrat, in a debate against some of the contenders for the Georgia senate seat special election. Starting at the bottom left is Democratic candidate Matt Lieberman, Lisa Rayam of WABE 90.1, Democratic Candidate Ed Tavern (D-GA), Republican candidate Doug Collins, Scott Sade of WSB Radio, Greg Bluestein of the Atlanta Journal Constitution, and Libertarian Party Candidate Brian Slowinski. (Photo: Screenshot of the Georgia Senate Debate hosted by The Atlanta Press Club)

LAVELLE: Right, and the interesting thing is that he's been just slightly in the lead in that race ahead of everyone. And he is a pastor. He has been pastor of Martin Luther King's church, the Ebenezer Baptist Church, in Atlanta, and he has really made environmental justice, his top issue. He's has worked on interfaith meetings on environmental justice, even before running for Senate, he brought Al Gore inn to talk to folks in his church, he has really tried to energize folks in the church to work on climate and environmental justice issues, he really tries to stress the connection between the environment and poverty.

BASCOMB: Well, both North Carolina and Georgia are historically red states that are starting to turn blue or at least a shade of purple. Generally, how would you say that climate change and the environment play into that shifting political orientation?

LAVELLE: I think one of the things that you're seeing in both of these states is there is a lot of migration of young people to the States. And it's not that the young people moving in are like really radical progressives. But it's just not acceptable for these new immigrants to North Carolina, and to Georgia, it's not acceptable to deny climate change. That seems like really backwards, and I think they don't want to tear down the economy, but they want to build it up and they see a pro climate action as the, you know, pro economic growth sort of approach and I think you're seeing that in both Georgia and North Carolina.

BASCOMB: Marianne Lavelle is a reporter for InsideClimate News. Marianne, thanks for taking this time with me today.

LAVELLE: Glad to be here.

Related links:

- Learn more about the North Carolina senate race

- Learn more about the Georgia senate races

- Watch the special Georgia senate race debate

[MUSIC: Ellis Marsalis, “Sweet Georgia Brown” on Heart Of Gold, Sony Music Entertainment Inc.]

CURWOOD: You can hear our program anytime on our website, or get an audio download. The address is LOE dot org. That's LOE dot O-R-G. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you: You can reach us at comments @ l-o-e dot org. Once again, comments @ l-o-e dot O-R-G.

Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. And you can call our listener line, at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88.

[MUSIC: Ellis Marsalis, “Sweet Georgia Brown” on Heart Of Gold, Sony Music Entertainment Inc.]

BASCOMB: Coming up – A field guide to easing climate anxiety, especially for young people.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Rothenberg/John Wieczorek/Robert Jurjendal, “On All Tides” on Soo-Roo, by Rothenberg/Wieczorek/Jurjendal, Terra Nova Music]

Rapid Ice Melt and Rising Seas

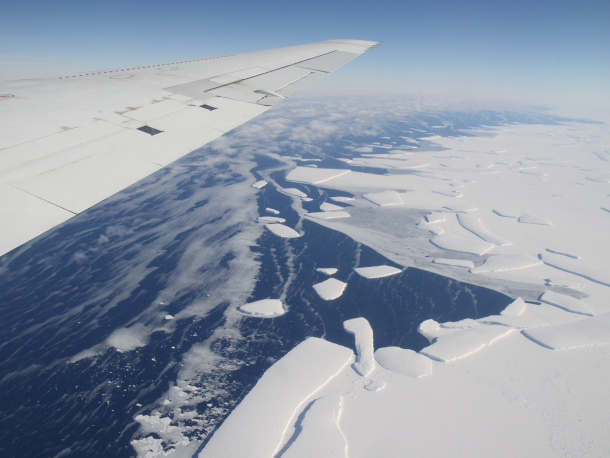

Ice shelves in West Antarctica are shedding icebergs due to warming ocean waters. (Photo: Jefferson Beck, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

As the planet continues to warm, the ice of Antarctica and Greenland melts faster and faster, adding to sea level rise. Scientists say even if the Paris Climate Agreement goals are met, melting from the West Antarctic ice sheet alone could raise the oceans some eight feet by the end of the century. Sooner than that, in less than 30 years, the ice losses from Antarctica, combined with the rapid melting of Greenland are projected to elevate the seas one if not two feet. And that doesn’t factor in the impacts of thermal expansion of water already in the ocean and the melting of mountain glaciers. Here to discuss the latest research is Michael Oppenheimer, Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs at Princeton University. Michael Oppenheimer, welcome to Living on Earth!

OPPENHEIMER: Glad to be here!

CURWOOD: Walk me through the science behind the melting of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets. What's going on?

OPPENHEIMER: First of all, let's understand what an ice sheet is and how it forms. Think about a pancake on a griddle, the pancake slowly spreads out. And the reason it does is the weight of the liquid when you pour it down, and once that spot basically pushes the pancake, so the circle of pancake expands, well, an ice sheet forms when instead of pancake batter, snow falls on the middle of a very cold continent. And as that mountain of snow piles up and transitions to ice, the weight is increasing. And that weight, just under the force of gravity, pulls the whole thing down, and the ice spreads out and eventually covers the continent. That's what happens in Greenland. And that's what happens in Antarctica. And then that addition of ice due to snowfall is balanced out, because as the pancake or mountain of snow and ice spreads and gets toward the ocean. Well, the ocean is warmer than the land area in the Arctic. And number two, as that mountain of pancake or ice collapses and spreads, it's getting lower in altitude. So if you go toward the edges where the ocean is, you're at sea level eventually, and the atmosphere is colder up high and warmer down near sea level. So those two effects mean that the ice around the edge is going to start to melt a little bit. If you look at the Greenland ice sheet, the primary contribution to sea level rise is the runoff of melting water. Antarctica is a little more complicated. The ice doesn't just melt there, it doesn't melt much at all. In fact, what it does is it slides. Just think of that pancake again, the stuff is oozing towards the edge of the pan. Same thing with the ice, it oozes or flows. And when it gets to the water to the ocean edge, pieces break off -- those are icebergs. So there are two contributions to sea level rise from these ice sheets, direct melting and their warmer parts, and flow and formation of icebergs when the flowing ice gets to the ocean's edge.

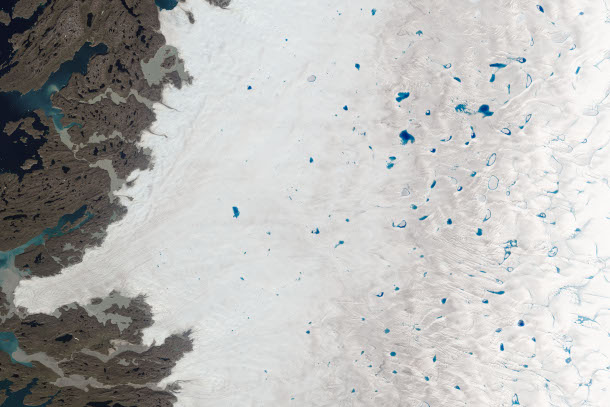

Blue meltwater lakes known as melt ponds appear on the Greenland Ice sheet in the middle of the summer. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Michael, give me some numbers, what's going on with the nexus of sea level rise and the loss of ice?

OPPENHEIMER: Well, let's look at it historically, what happened during the 20th century, for instance. Sea level rose about six inches. And that was largely absent any significant contribution except for the last 15 years maybe of that century from the ice sheets. And it rose six inches, largely due to thermal expansion and the melting of mountain glaciers. As I said, the rate is now accelerated, it's going now at sea level rise the equivalent of 12 inches per century, but it's not going to just stay at that level, it's already accelerating. And it's going to get faster and faster. By the end of this century, depending on which projections you look at, the rate of sea level rise could wind up being about five times what it was, about five times that six inches in the 20th century. And we're having trouble dealing with the six inches that we had trouble last century. In this century, five times as fast sea level rises can be awfully difficult to deal with. At this point, we're not ready for it. We're not primed to deal with it. We haven't deployed the adaptive measures that we really need to at the scope and rate that we need to. So this is a looming not just a difficulty, but in some cases a disaster.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the challenges that coastal communities face now amid these rising sea levels.

OPPENHEIMER: Well, there are two major challenges. One is sea level is rising in some sense faster than people's ability to grasp what's going on and government's ability to mobilize and act. And secondly, there's a larger uncertainty about exactly what's going to happen because of the uncertainty in the behavior of the ice sheets. But we know that the thermal expansion of seawater is happening, we know that mountain glaciers are happening, that part is not subject to a lot of uncertainty. And furthermore, the other big uncertainty in this problem is how much greenhouse gas we're going to emit into the atmosphere in the next 20, 30, 40 years and therefore, how warm the planet will get and therefore how much ice melt and thermal expansion will get. And when you put all that together, what you see interestingly is the difference in the sea level rise projections between a lot of emissions and not too much emissions is not very much until you get out to about 2040/2050. So for the next approximately 30 years, you can say with fairly good confidence that we know what the sea level rise is going to be.

The Greenland ice sheet is melting, forming streams and rivers on the surface. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what is that number? How much sea level rise for parts of the United States by the year 2050?

OPPENHEIMER: Well, we're talking about one or two feet, which may not sound huge, but on a typical East Coast beach, a foot of sea level rise takes away a hundred feet of beach horizontally going inland, unless you keep feeding the beach. And that's just sort of symbolic of what's going to happen. A lot of areas aren't beachy. There are buildings in places like downtown Boston or downtown Manhattan, that are just a few feet above sea level, and you add high tide to it, and you add a storm to it, and all of a sudden, you got a lot of flooding, just like happened in Hurricane Sandy. or forget Hurricane Sandy, a big Nor'east storm. A Nor'easter in this neighborhood does the same thing at a slightly smaller scale. So we have a problem today, this isn't a problem for the future. This is what we failed to protect against adequately today.

CURWOOD: If the ice continues to melt at this pace, what does this mean for the future of humanity?

OPPENHEIMER: Well, it means among other things, that we are inevitably going to lose a lot of cultural heritage, because a lot of human cultural heritage is built right along the coast. And that's unfortunate, but it also means huge amounts of money lost. And it also means lives lost because people are caught unaware in big floods that happen now more and more regularly.

CURWOOD: So before you go, give me an assessment please of what policies you think are necessary to curb this damage to the ice sheets, to at least slow down this process? And what do you think the role of the United States is in this? And for that matter, what do you think of the various climate proposals that are around here in the US?

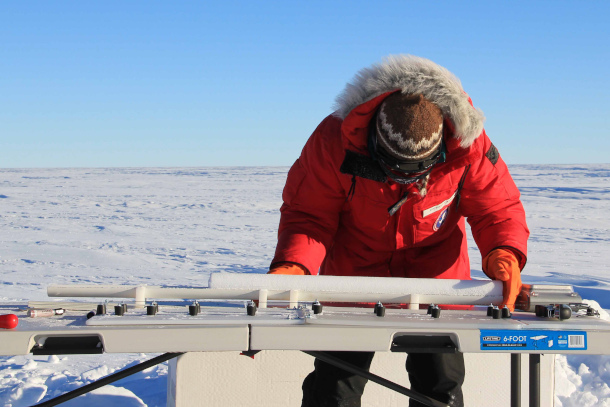

A scientist studies ice cores on the West Antarctic ice sheet to calculate its snow accumulation. (Photo: NASA ICE, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

OPPENHEIMER: The bottom line is we're not going to get anywhere. And we're always going to be behind if we don't implement very quickly a serious program to reduce emissions of the greenhouse gases, particularly carbon dioxide from burning coal, oil and natural gas that are causing the problem in the first place. As much adaptation as you do, climate change will always have run into if you don't control the greenhouse gas emissions. As much greenhouse gas emissions as you control, it won't be enough to protect people, unless we also do a significant amount of adaptation. So we have to do both. We need to build cities and other settlements smartly, so they're not so exposed to sea level rise. There should be funding for building sea walls, surge barriers, whatever coastal defenses are necessary, where they're necessary, and there should be funding for facilitating people who make the choice to relocate away from the coast or away from forest fire areas or away from any area that's threatened by climate change, and where there's a limit to how much protection the governments can offer or that individuals can take upon themselves. So it all fits together that solving climate change isn't like often some corner by itself. Solving the climate change problem is integral to setting our society right again.

CURWOOD: Michael Oppenheimer is a Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs at Princeton University. Michael, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

OPPENHEIMER: It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Nature | “The Worst Is Yet to Come for the Greenland Ice Sheet”

- The Guardian | “Melting Antarctic Ice Will Raise Sea Level by 2.5 Meters – Even if Paris Climate Goals Are Met, Study Finds”

- Michael Oppenheimer’s role in the Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment

- The YEARS Project | Governments are Failing to Adapt to Sea Level Rise

[MUSIC: Abba, “SOS.” on ABBA: The Studio Albums, Capitol Records]

Overcoming Climate Anxiety

A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety helps provide readers with an ‘existential toolkit’ for confronting the climate crisis. (Image: Courtesy of Sarah Jaquette Ray)

BASCOMB: From melting glaciers and sea level rise to tropical deforestation and habitat loss the many problems associated with climate disruption can feel overwhelming and, frankly depressing. And people are already feeling the impacts of climate change that will be with us for the rest of our lives. With such a burdensome future many young people are organizing for climate action, yet it can be hard to deal with the feelings of powerlessness and despair that can accompany the hard work of social movements. So, for some cheer they might want to read a new book called A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How To Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet. Its author is Sarah Jaquette Ray, professor of environmental studies at Humboldt State University in California. In front of a live audience at a Good Reads on Earth virtual event, she spoke with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So what inspired you to write this book, A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety?

RAY: Yeah, so what inspired me to write this book was that I'm sort of hyper-empathetic for my students and I, it's one of the reasons why I love to teach. And as a college professor and leading environmental science programs for the past 10 years, I had noticed that over the last four or five years or so, students were increasingly getting more and more existentially wrought over these issues. And when I say these issues, I don't even mean climate change. At that point, it was mostly just things like environmental injustice, and the extent to which humans have affected the environment, sort of all of these realities sinking in, in the college level, and a lot of the challenges to the things that they had learned themselves growing up. It's overwhelming, and increasingly young people are feeling the effects of climate change too, they're no longer, it's no longer a distant thing that's happening only to polar bears or something. It's really happening, and they're, they're reframing it as "the fires that I'm experiencing," or "the rising sea levels I'm experiencing," or "the increased heat I'm experiencing." All of a sudden, these, the dots are getting connected to climate change. And they're, they're no longer thinking of it as something that's going to happen 100 years from now, or 200 years from now, but really in their lifetimes. And I think that the despair and anxiety around that was starting to be overwhelming to me as well. I had sort of been able to push those things in a cupboard and, and ignore it and just get on with my life and have children and go on being a professor of environmental studies, when I realized that the tools I was going to need for myself and for students, were really going to be something other than what I had been trained in during my PhD.

DOERING: Let's talk about some of these strategies that you bring up in your book to help people cope with climate anxiety. I wonder if you could highlight a few of the most important big takeaways, and kind of like the themes that you have in this book.

Prof. Sarah Jaquette Ray leads the Environmental Studies Department at Humboldt State University. (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Jaquette Ray)

RAY: Yeah, one of them is that environmentalism as a movement has generally been a movement that has emphasized scarcity and deprivation and guilt and these kinds of feelings, right? And so I really am really strongly arguing in this book, that environmentalism needs to be reframed. And we can take the lead again, from young people, as a movement of abundance and pleasure and desire, and the imagination of what the world could possibly be like if we wanted to manifest it and make it.

DOERING: So just to pause there for a sec; you know, pleasure and desire, these were things I did not know could be associated with, like the environmental movement before reading this book. So can you explain what does that mean?

RAY: Yeah, so I think, less stick, more carrot, right? You know, we know how dopamine works in the human brain, and people will keep coming back when there's pleasure associated with things. Environmentalism ought to use pleasure really strategically around how it is that we manifest the worlds that we want. And so instead of operating from a place of, "look at this awful world that's unfolding ahead of us," instead, taking the cue from young people, that we ought to be thinking about a world that's unfolding and turning into something much better. And so young people thinking about a future that they desire and imagining that every single day that they are crafting and moving step by step in small ways towards this future, even if all it is, is creating that world in their immediate scale around them, is an extremely empowering argument to make. And it also taps right into pleasure and desire. And that's what I noticed with my students, right, all of a sudden, and this kind of segues into my second main takeaway, when I realized that my students were not just individual bodies in there, and that I had individual relationships with them; that in fact, the biggest outcome that they could have would be to have a community with each other, and across cohorts and to see each other as, as a lab for the world that they're trying to build outside of college, that this is really, this is the practice, right now. It changed everything about the way I teach.

DOERING: And on that note of community, actually, I'm curious, have you seen changes in the students as you've been like putting these strategies into practice? Have you seen changes in the ways that they've been organizing themselves and, you know, going about divestment or whatever they want to take on as students?

RAY: Yeah, I think, I think one of the key things there is, and this would be the third point, which is to resist burnout. And I think a lot of young people sort of maybe wear their exhaustion and their burnout as kind of a badge of credibility, that this is the way that they're showing that they are invested enough and that they are sacrificing, they're sacrificing, that must mean that they are, you know, credibly engaged. One of the things I have students do, one of the exercises is I, we read this book by Adrienne Maree Brown called Emergent Strategy. And in Emergent Strategy, Adrienne Maree Brown talks a lot about misery resistance, having a practice of misery resistance. And so there's a sense of, instead of waiting around for enough people to care about it, build a community that you have right around you, and make the connection be what's valuable, what's going to make the change happen. And so when students start to internalize things like the critique of individualism, that burnout is not a badge of honor, that the planet needs you to not burn out, right? That resourcing yourself and feeling pleasure is part of the way you're going to keep doing this work and also share the love of this work with other people, then they take that into the stuff that they're doing. And the other thing I've noticed that's so different is that they really see that humanity and people and human connections are going to be the way to get where we need to go with the environment, rather than seeing humanity and human relationships as an impediment to that.

DOERING: What can we learn from other social movements about the importance of addressing our fears and anxieties and resisting burnout?

As seen in the 2014 People’s Climate March, the climate movement spans generations, but the impact of a changing climate has fallen heavily on the shoulders of young people, who face a lifetime when the effects of the changing climate are ubiquitous. (Photo: Open Minder, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

RAY: Yeah, so social movements can teach us that the kind of instrumentalism around our actions, this sort of expectation that we're going to see immediate results, that is really dangerous, and that that will undermine us, and we'll give up right away. And so the folks who I'm thinking about talk a lot about a kind of hope that isn't so instrumental, that doesn't require evidence to prove that your actions are resulting in these kinds of results, right? Social movements can really teach us different emotions that we need to be, you know, deploying and using strategically, and how to deal with grief, and how to get up and still be resilient in the face of a lot of evidence against you. And they also, social movements have never had a problem, thinking seriously about emotion and the role of emotion in advocacy. Environmental studies educators and educators in general, in higher education, we think of young people as leaving their hearts at the door, and only bringing in their heads. And social movements know that engaged, long-term advocacy needs the heart, hand, and the head. You need action, you need feelings -- you need your sort of soul and spirit and feelings -- and you also need cognitive analysis and skills. And so that sort of trilogy of all three different modes of being have been completely ignored by higher education in general, and in general, from the climate movement as well.

DOERING: Have you had any students from communities affected by climate change now, and do their emotions differ from students from more affluent communities?

RAY: That is a very good question. And the answer is an absolute yes. So the CSU that I work in, the Cal State system, is not a very affluent system to begin with. So my students, I wouldn't say are privileged relative to lots of college students in that sense. But even then, environmental studies used to attract more of a white, somewhat more privileged, you know, demographic of students, and the dominant emotion that they were having when they would learn these things, was kind of disillusionment and really a sense of their pervasive complicity in all of the problems, and so guilt was kind of the main thing. And I called it kind of, eco white fragility, right? There's a sort of white fragility thing, but there's a green white fragility, that's a different thing, right? But to go to the question of, is it different for people experiencing it, absolutely. And so increasingly, environmental studies classes are getting more diverse. And the affect is very different, the emotional response to this material is very different because what they're reading about and learning about is their communities now, it's not just some other community. And if you assume that your students are white, privileged, environmentalist, that just re-centers the white experience again, right? Coming to environmental education with trauma-informed pedagogy, for example, when you assume they experience your students are experiencing trauma of some kind, whether it's displacement, or intergenerational trauma, or sexualized violence, or police brutality, or climate trauma, then you have a very different set of approaches and obligations to those students.

BASCOMB: That’s Sarah Jaquette Ray, author of A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Read more about A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety

- Learn more about climate anxiety and some of the efforts to address it

- Why is it important to address this issue for youth? Read about the efforts of youth climate activists here

- Watch the LOE "Good Reads on Earth" virtual live event

[MUSIC: Fred Simon/Bonnie Herman/Liz Cifani, “Time and the River” on Soul Of the Machine, by Fred Simon, Windham Hill Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – why digging in a bit of dirt and grass can be healthy for children, That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Rothenberg/John Wieczorek/Robert Jurjendal, “On All Tides” on Soo-Roo, by Rothenberg/Wieczorek/Jurjendal, Terra Nova Music]

Beyond the Headlines

Seven of New York’s fossil fuel “peaker” plants, which operate only when the city hits peak power necessity, are in the process of being converted either to cleaner energy or to conservation. (Photo: Wally Gobetz, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

And it's time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. He's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. What may be a little good news coming out of New York State. The New York Power Authority better known as NYPA, which governs the generation of electricity, not just in New York City, but all over the state cut a deal with environmental justice groups to ensure that six of what are called "peaker" power plants in poor minority communities in New York City, be transitioned from fossil fuels to clean energy or conservation.

CURWOOD: Okay, hey, and remind us what are peaker plants?

DYKSTRA: Peaker plants are sort of a quirk in the power generation grid. When plants have to work overtime, let's say in hot weather to power air conditioners, they will turn on dormant plants, those are the peaker plants, to serve peak power generation times. Right now, New York City has a lot of older fossil fuel plants. Among its 18 peaker plants, about a third of those they hope are going to be converted to conservation to save energy, or clean energy.

CURWOOD: And what do these old peaker plants burn?

DYKSTRA: Some of them burn really nasty stuff, like heating oil or kerosene. Some are natural gas plants. And every time there's a hot day in Manhattan, there are some poor neighborhoods in the Bronx, and Queens, and Brooklyn that pay the price in dirty air. But the bottom line is these kinds of plants under this deal will be used a little bit less in New York City.

CURWOOD: That's a good news story. Peter, what else do you have for us today?

A study out of Finland lends credence to the “hygiene hypothesis”, the notion that children who are exposed to a certain level of microbial life build up a stronger immune system throughout their lives. (Photo: Chiot’s Run, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: It's an interesting piece of research. It's a kind of a small study out of Finland. The study says that greener play areas can help children's immune systems. They show that gravel play areas tend to host fewer microbes. Because there are fewer microbes, the immunity systems for kids don't build up as well as if you had soil and grass and other things within a playground area. And of course, gravel to grass makes it look a whole lot nicer.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now, what kind of diseases are they talking about?

DYKSTRA: A lot of sort of the first level of autoimmune diseases, everything from allergies and asthma, to eczema in the skin, type 1 diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and even MS.

CURWOOD: Multiple Sclerosis. Folks have argued for years that if kids are too isolated from germs, it's not good for them.

DYKSTRA: That's right. You know, if you want every kid to live in a bubble, you're sort of working against what's called the hygiene hypothesis. Where if kids are in an atmosphere, where they're kept theoretically immaculate, they're not gonna develop all of the defenses that they need to get through life.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. So crack open one of those history books that you got there, tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: Well, crack open the history book and out pops a 25th anniversary, October 21, 1995. At the Tokyo Auto Show, Toyota rolls out its first prototype of the Prius, its now-legendary hybrid gas and electric car.

The Toyota Prius model NHW10 was unveiled as a concept car at the 1995 Tokyo Motor Show. (Photo: M.rJirapat, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I remember two years later, at the Kyoto climate conference, the execs from Toyota brought around a couple of them for us reporters to ride in, but they wouldn't let us behind the wheel.

DYKSTRA: Well, two years behind history, you could do worse than that. And the Prius has become such an institution around the world, along with its hybrid competitors, and more recently, its purely-electric vehicle competitors. They've sold a million Priuses, or Prei I don't know what you'd call it, around the world since that momentous date 25 years ago.

CURWOOD: Sounds like success for a car. Hey, thanks so much, Peter, for taking the time with us today. Peter Dykstra's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Grist | “New York Says Goodbye to 6 Dirty Power Plants and Hello to Working with Communities”

- The Guardian | “Greener Play Areas Boost Children’s Immune Systems, Research Finds”

[MUSIC: Andrew Bockelman/Neil Candelora/Brendan Peleo-Lazar, “Baby You Can Drive My Car” by Lennon and McCartney, on Ably House]

Hiking in 6-Inch Heels

Pattie Gonia on a beach in Hawaii. (Photo: Courtesy of Pattie Gonia)

BASCOMB: The great outdoors is wild, rugged, and often cast in masculine terms. So, it can be easy for queer and gender non-conforming people to feel excluded from outdoor spaces. But photographer Wyn Wiley wants to change that. Wyn spends his spare time hiking in the back country as Pattie Gonia, a drag queen complete with wigs, exaggerated makeup and six inch heels. Pattie posts pictures of herself on Instagram to encourage everybody, regardless of gender identity and sexual orientation, to get out and enjoy nature. She has amassed some 300,000 followers on Instagram and joins us now, in those 6 inch heels, to discuss her journey as a queer environmental activist and the solace she finds in nature. Pattie Gonia, welcome to Living on Earth.

PATTIE GONIA: Thank you for having me. I'm excited.

BASCOMB: Yeah, we're so excited to have you. Growing up in Nebraska. What was your relationship like with the environment, with the natural world around you?

PATTIE GONIA: Yeah. Growing up in Nebraska, I had nature all around me, I lived my life, my grandma's farm and in my backyard. And there's no more vivid memory of childhood than like the giant oak tree in my backyard and the swing attached the oak tree. And I also spent a lot of time growing up in Boy Scouts and that brought me outdoors as well.

BASCOMB: Now today, you're putting together your love of nature and your expression of yourself through drag. Can you tell us about that, about hiking outdoors in full drag regalia? What does that look like? And how does it feel for you?

Wyn created Pattie Gonia two years ago and has accumulated over 300,000 follows on the account’s Instagram page. (Photo: Courtesy of Pattie Gonia)

PATTIE GONIA: I feel very lucky that my passions get to intersect so much. I really feel like for anyone in life when you can get a chance to intersect your passions, and kind of Venn diagram one circle over the other and find that middle, ooey gooey like good zone, it's so wonderful. I feel so alive. So when I do drag in the outdoors I feel the most me. And yes, that means literally backpacking in high heels, which you can think is a very silly and stupid and dangerous thing but so is riding a mountain bike down a mountain at 45 miles an hour. So you know pick and choose your danger in the outdoors. I just choose to wear some six inch heels, but it's really beautiful for me to get to also be very feminine and be in touch with my femininity and a space I feel is very feminine. And I feel like we're told through media, through just the narratives and through the archetypes in the outdoors that the outdoors are a very masculine space. They're very, they're there to conquer, and I enjoy being with them, and I enjoy making art with them. It totally changes my experience with the outdoors when I'm in drag as well. I feel like I noticed things I wouldn't out of drag.

BASCOMB: Really like what

PATTIE GONIA: You know when you sit and you do your makeup for three hours and you're in one place, you just notice a lot of things. You notice the birds. You notice the flowers around you, I think I spent so much of my life, especially pre quarantine going at such a fast pace. And I think when you're out on the trail you also can go such a fast pace even though you're walking, you know, you're you're going by so much so fast. And I feel like when I'm sitting there, I can just notice what's actually around me and can realize how much of a, how much of like a symphony at all is how much everything has a purpose, myself too.

BASCOMB: And what inspired you to start doing drag to begin with?

PATTIE GONIA: I think what inspired me to do drag was finally wanting to do it for myself. I grew up in Nebraska, in an incredibly beautiful environment, but one that basically was told to me only accepted me if I was straight passing. So when I came out, it was conditional love. It was, hey, we love you. This is beautiful. We accept you for who you are, but never do drag but never want to transition to be a female. But never, this never that. Don't change your voice. Don't don't have a feminine voice. So I think drag for me was the release of kind of a lot of toxicity that I'd internalized since initially coming out. And just falling in love more and more with drag ever since. I'm fascinated with the freedom that I feel when I'm a drag.

Many of Pattie’s looks, like this one, are inspired by animals, plants, and the great outdoors. (Photo: Courtesy of Pattie Gonia)

BASCOMB: And so for someone that hasn't seen your Instagram posts, can you describe a typical outfit that you might wear on the trail or even a favorite outfit that you've worn that would really give people an image in their mind?

PATTIE GONIA: Absolutely. So I just want you to think of the most absolutely absurd things you could ever imagine a drag queen to wear and that's literally what I'm wearing. So one of my favorite outfits is actually made by one of my friends, Angela, and the dress is actually a full functioning tent. You can take off the dress, you can literally put poles in it and it turns into a tent. I'm not kidding. So she originally designed it as a jacket that was used to basically bring up the conversation of refugees. So she's made hundreds of these coats to give to refugees to be able to have as jackets slash coats and also as tents that they can sleep in as well. But we're repurposing it for the outdoors as well. So it's fun. I think it's definitely fun to just have fun with fashion to not take it too seriously. Some of my favorite looks are things I throw together like that. And or I have a piece that I want to show and tell with you that I want to describe for listeners.

BASCOMB: That'd be great.

PATTIE GONIA: So so this is a wig made of over 100 pieces of plastic.

BASCOMB: Woah, looks like a giant disco ball of plastic.

PATTIE GONIA: Yes, it is very, I think very like Amadeus. Like, like very much queen, old royalty, like can we create a two foot tall wig on a head? Yes, we can. And let's do that of plastic. So this is all differently like upcycled plastic items. And I'm going to set the phone number so I can put on and then I'll pick up the phone again. So give me one second.

Pattie showing off her six-inch heels. (Photo: Courtesy of Pattie Gonia)

BASCOMB: Perfect yeah.

PATTIE GONIA: Okay, just so you can see the full effect.

BASCOMB: Perfectly I love it.

PATTIE GONIA: Okay, so this is it. It literally looks like I am wearing just a giant stacked pile of trash on my head because I am.

BASCOMB: Well it looks very, you know, Marie Antoinette to me, you know, like back in that era, there was so over the top with things like that weren't even trying to look real.

PATTIE GONIA: Absolutely. And it's great it like, ruffles in the wind, like you can kind of hear it. We'll do some ASMR. Something I'm thinking about all the time is that drag as a culture is inherently very wasteful. And I'm really trying to deconstruct drag for the purpose of making it as sustainable as can be. So this is a wig made of plastic because plastic wigs you see drag queens wear that look like real hair are literally plastic. So why am I putting new plastic into the world rather than wearing trash? So I am a trashy queen? Here I am.

BASCOMB: Love it.

PATTIE GONIA: So I'm gonna take this off because it's gonna be like audio interference. But yeah.

BASCOMB: It doesn't look too comfortable, either.

PATTIE GONIA: It's actually really comfortable. It's -

BASCOMB: Really?

PATTIE GONIA: One of my most comfortable wigs. Yeah, it's amazing.

Pattie’s short film, Dear Mother Nature about being herself in the outdoors was nominated for several awards. (Photo: Courtesy of Pattie Gonia)

BASCOMB: Yeah, super fun. And what kind of reactions do you get from other people on the trail that are probably not expecting to run into a drag queen? Well, you know, out and about in the woods?

PATTIE GONIA: Absolutely. Um, it's always a mixed bag. I'm fascinated with how much even just wearing heels even if they're not in for drag, but just hiking in heels, is such a disarming moment, like people will, it'll catch them off guard and notice the heels and they'll light up inside and they're like, oh my gosh, hi. Whoa. And it's always a conversation starter. Of course. It's not like you see people walking in six inch heels out in nature. But I think it's a really beautiful touch point to learn. And I love opening up conversation with people if they're open to it on the trail, but I've definitely had an experience homophobia on the trail, too. I've definitely not felt comfortable at many points on the trail, especially when I'm more in full form drag, have been called a circus act on the trail. I've been called other words, we will not say on public radio, so it's a mixed bag. But I'm amazed at how often it's a positive interaction.

BASCOMB: You know, we've had a few segments on Living on Earth recently about people of color, enjoying the outdoors, and I'm sure you're familiar with the story of Christian Cooper, the African American man who was birding in Central Park when a white woman called the police on him after he asked her to leash her dog. You know, people of color routinely report feeling unsafe or unwelcome in the outdoors. How does that sentiment resonate with you as a queer person, as a drag queen?

PATTIE GONIA: Absolutely. I think the practice of drag really lets me know that the hate that I face and the homophobia that I face is a sliver of what people of color experience, is a sliver of what my trans and non binary queer community members experience on the trail. It's a very different experience in a very privileged experience that underneath drag, I am a white, straight-passing male. And that's something I'm thinking about all the time. And thinking about how much drag really lets my queerness unfold. But the privilege it is to be able to wipe off makeup at the end of the day, the privilege to be able to pack away my heels and have no one know about my difference or about that I'm a member of a marginalized community. So I think it's a really, really interesting practice. And I'm not at all comparing my experience to theirs, but it literally does very much let me know how much work we have to do in the outdoors to truly make them an inclusive place for everybody.

BASCOMB: And why do you think it's important to see queer people in the outdoors?

Pattie describes herself as an intersectional environmentalist. (Photo: Courtesy of Pattie Gonia)

PATTIE GONIA: I think it's important to see queer people in the outdoors, because nature is so queer itself. Because queer people are people too. Because if the outdoors can't be a place where we celebrate diversity, something that Mother Nature knows is absolutely key. For the longest time, I didn't see myself represented in the queer community because I'm not a person that's going to spend their Friday or Saturday night in a bar club. And I'm not dogging that. I'm just saying, I'm going to be out on the trail. I'm gonna be out camping. And so I've been really thankful for this journey with Pattie to really remind me how much we can create queer community in the outdoors and how important that is and how many queer people were already out there in the outdoors. We just didn't have as many campfires to kind of gather around.

BASCOMB:Wynn Wildly is Pattie Gonia intersectional environmentalist and self described photos drag queen. Thank you so much for taking this time with me and sharing your story.

PATTIE GONIA:Thank you so much for letting one of my baby steps of being a drag queen be being on your show.

Related links:

- Pattie Gonia’s Instagram page

- Dear Mother Nature, featuring Pattie Gonia

[MUSIC: Yonji Visomoku/Kim Miguel, “Dance the Night Away” by Van Halen, Cry Baby Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth