November 13, 2020

Air Date: November 13, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate and the Biden Transition

View the page for this story

Along with climate action President-elect Joe Biden has pledged to rectify COVID-19, the economy and equal justice, goals that he can help achieve by getting strong start to his presidency in the transition process. Joe Aldy is a Harvard economist and veteran of the Obama White House and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how the Biden transition team can best plan to fight climate disruption after four years of policy disruption. (12:49)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Bobby Bascomb cover a sweeping ban on single use plastic bags in the State of New Jersey. They continue their conversation with a successful seagrass restoration project in Virginia. And they look back 70 years to the installation of the 14th Dalai Lama, who has advocated strongly for peace and a healthy environment. (04:01)

Lead in Hunted Meat

View the page for this story

Millions of American families who eat hunted meat may be exposed to lead poisoning from the bullets that killed the animal. What’s more, hunters donate some 2 million pounds of hunted meat to food banks across the U.S. each year, most of which is not inspected for lead contamination. Sam Totoni reported a series on lead in hunted meat for Environmental Health News and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the grave implications of this overlooked risk. (10:42)

Midtown Coyote

/ Berry JunghansView the page for this story

In an era of remote learning and spotty Zoom meetings, we humans still have it easier than many animals trying to raise their young. Writer Jennifer Berry Junghans on how a mother coyote manages to eke out a living in the heart of California’s capitol. (04:38)

Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Rings

View the page for this story

Trees are constantly storing information about climatic conditions in the rings they lay down each year. Paleoclimatologist Valerie Trouet of the University of Arizona uses the science of dendrochronology to learn about the ancient climate on Earth by studying tree rings. She’s the author of “Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Rings,” and joined Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about the incredible discoveries scientists have made thanks to tree rings. (15:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

201113 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joe Aldy, Jennifer Berry Junghans, Samantha Totoni, Valerie Trouet

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

How the Biden transition team can lay the groundwork for climate action starting on day one.

ALDY: I think it's critical to have a whole-of-government approach. Climate change does impact, and climate change policy will impact, virtually every corner of our society. So I think a National Climate Council could help make sure that everything the government is doing is really advancing the President's agenda on climate change.

CURWOOD: Also, rising concerns about toxic lead in the meat from hunting consumed by millions of Americans.

TOTONI: This issue is definitely real. Lead ammunition contaminates meat and is absorbed by the digestive system. And that is significant because there is no safe level of lead in the blood. There's just overwhelming scientific evidence that this problem is real.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate and the Biden Transition

President-elect Joe Biden and his transition team have to move quickly now to hit the ground running on climate change from Day One of his presidency. Seen here in 2014, then-President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden hustle along the Colonnade of the White House during a “Let’s Move!” video taping. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

By January 20th President-elect Joe Biden has to figure how to make nearly five thousand appointments of people to lead the federal government, and how to budget some five trillion dollars next year to get all the work done. Top priorities are Covid-19, climate, the economy and equal justice. The transition to power takes planning and coordination, but as we go to air, the Trump administration is making false claims of election fraud and denying Mr. Biden access to key government agencies and their information. And the Biden Harris transition crew also has to juggle plans in the face of not knowing until January 5th or so whether the Senate will have a friendly or oppositional majority in power. Joe Aldy joins us now to discuss how the Biden transition team can best plan to fight climate disruption. Professor Aldy is an Harvard economist and veteran of the Obama White House. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Joe!

ALDY: Thanks, Steve. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand you worked on the transition team for the beginning of the Obama-Biden administration. What was that like?

ALDY: Well, it was an incredible experience working for then President-elect Obama. But it actually began a few months before the election, there was a small group of us focused on energy and environmental policy, who began working about three months before the election. And then once President Obama was elected, we then moved into the headquarters for the Presidential Transition Team and started working with the entire staff who were trying to stand up a new administration for then President Elect Obama.

What is becoming clearer each hour is that record numbers of Americans — from all races, faiths, regions — chose change over more of the same.

— Joe Biden (@JoeBiden) November 7, 2020

They have given us a mandate for action on COVID and the economy and climate change and systemic racism.

As he aims to tackle 4 key issues facing the nation, each no small task, President-elect Joe Biden needs a smart transition team to lay a strong foundation for action on them.

CURWOOD: And after that you stayed in the White House for a while.

ALDY: I was honored to then move I started January 21, of 2009, working in the White House at both the National Economic Council and the Office of Energy and Climate Change, and did so for the first two years of the Obama administration.

CURWOOD: So to what extent do you think that President-elect Biden has followed that model working actually, on these issues well before the election and assembling a team?

ALDY: Well, I think it's clear, they started laying the groundwork and thinking through the key staff who would help organize and run a transition even before the election. And, and part of that is, standing up a new administration is an incredible amount of work. And so it's important to do your homework and be prepared, especially when we think about the daunting challenges that the President-elect faces, because of the COVID pandemic, the state of the economy, the nature of race relations across the country, and certainly, as President-elect Biden has noted, the climate crisis that we need to confront.

CURWOOD: Some people say that it's important to have a "whole-of-government" approach to dealing with the climate, because it touches so many things, from economics to equity, along with health, and, of course, the very science and technology of dealing with climate disruption.

Joe Aldy and other people involved in the Climate 21 Project have recommended that the Biden administration create a National Climate Council within the White House to coordinate a “whole-of-government” approach to the climate crisis. (Photo: Ken Lund, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

ALDY: I think it's critical to have a whole-of-government approach. And it's critical, because you're right, that climate change does impact and climate change policy will impact virtually every corner of our society. So it's important to have someone, say, at the Pentagon, who does procurement, to think about the decisions they make, that can actually help create markets for new energy technologies. It's important to have someone at, say, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, to think about their policies that affect housing infrastructure, to ensure that it is A, resilient to climate change shocks, but also B, that we make the kinds of investments in our housing, that can improve their energy efficiency, can improve their use of solar power, could actually make sure that we're all sharing in the benefits of a clean energy transition. So it's not just thinking, what does the EPA Administrator do or the Secretary of Energy, but really every part of the government is going to be critical. And I think one role that's going to be especially important going forward in this first year of a Biden administration, is to think through what the Secretary of the Treasury, perhaps the director of Office of Management and Budget, the chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, they're going to be the economic advisors helping President Biden think through economic recovery as we try to create new jobs and come out of the COVID recession. And so I think it's going to be critical that how you think about aligning investments in clean energy, aligning investments to improve our resilience to climate change. That's part of that economic recovery package. I think when we look back at the experience in 2009 one of the big things we worked on in the presidential transition, in fact, we were negotiating with congressional staff during the transition period, were on the clean energy components of what became the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the major stimulus bill that was signed into law in February of 2009. Then, we spent about 100 billion dollars on clean energy. And I think we had some really incredible success stories, when we look at how much wind and solar has been invested and how much the cost of those technologies have come down, in part because of the support through the Recovery Act. But what we've seen is President-elect Biden's laid out a much more ambitious spending agenda on climate change. And I think you can try to make a key component of that in what will be the economic recovery package. So I think that's the sort of first step of what's going to have to be a number of major policy steps to try to deliver on the ambitious climate change goals he's laid out.

CURWOOD: So the new president and his administration will have a great deal of discretion over executive actions, regardless of which party ends up controlling the Senate. So talk to me about some of the first actions you anticipate the Biden administration will make on climate?

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (left) shakes hands with then-US President Barack Obama (right) during a 2016 celebration of China and the United States joining the Paris Agreement, as China’s President Xi Jinping (center) looks on. The Biden administration will need to rebuild trust and relationships with other countries to lead on climate. (Photo: Eskinder Debebe / UN, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

ALDY: Well, the first thing they'll do is they'll stop any pending regulatory processes related to climate, but they'll probably do that across the board, that's actually kind of a standard operating procedure for a new administration, that they, they sort of stop the sort of midnight rule making processes, if you will, those that are at the very end of the outgoing administration. The second thing they'll do is I think they'll look at several executive orders that Trump implemented, and rescind those, some that are focused on climate that really tried to reorient the federal government towards fossil fuels, they'll rescind those; but some that have major implications for climate, but are broader than climate. So early in the Trump administration, there was a regulatory policy executive order that effectively set a kind of regulatory cost budget, and said that any agency that wanted to do a new regulation had a strike two existing regulations. And all that does is sort of slow down the regulatory process. It really recast what has traditionally been an approach to regulation dating back to Ronald Reagan, that we look at benefits and costs. And in the Trump administration, they focused just on costs and said you can't increase the cost on industry in any new rule making. So I think they'll get rid of that executive order, which then makes it easier to think through, how do you move forward with regulations that make a lot of sense for society, where we're going to be making investments where the benefits are going to exceed the costs that are going to allow us to make significant progress in reducing our CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions. So I think you'll see a lot of that in the early days as focused on those kinds of executive orders, that then sets the foundation for the regulatory agencies to start moving forward. And those regulatory processes do take some time, if you do them right. And if there's one thing we've learned from the Trump administration, it's that if you do your rulemakings wrong, you will lose in the courts. They did it fast, they did it sloppy. And I think that's one thing that you will see is, I think, an aggressive regulatory agenda in a Biden administration, but one that is going to be deliberate, methodical, carefully done, so it can withstand judicial scrutiny, which is going to be all the more important, given how the courts have become more conservative with the Trump appointments over the last four years.

CURWOOD: Joe, any particular executive orders that you think Biden should jump on right away?

ALDY: Well, another one that'll be important, which gets to the process, which is how does he think about organizing the whole-of-government approach? You know, so I worked as a staffer to the National Economic Council, I also spent time supporting those who worked on the National Security Council. So we have these kinds of policymaking councils within the White House. And so one idea is that you create a National Climate Council within the White House that tries to coordinate all policy efforts across the federal government that are related to climate change. I think you'd also want to think about how you would design this National Climate Council to coordinate, say, with the Office of Management and Budget, when it comes time to developing the budget, so to make sure that we are truly considering and accounting for climate change throughout all of our planning on the budget; how we develop bilateral relationships, which is one of the first things that actually a new president can do to signal the seriousness on climate change. It's something we did back in 2009 with President Obama, every head of state visit he had in 2009, we had some kind of climate or clean energy deliverable, an agreement among the heads of state how we were going to each take actions to move forward on climate change. So I think a National Climate Council could help make sure that everything the government is doing is really advancing the President's agenda on climate change.

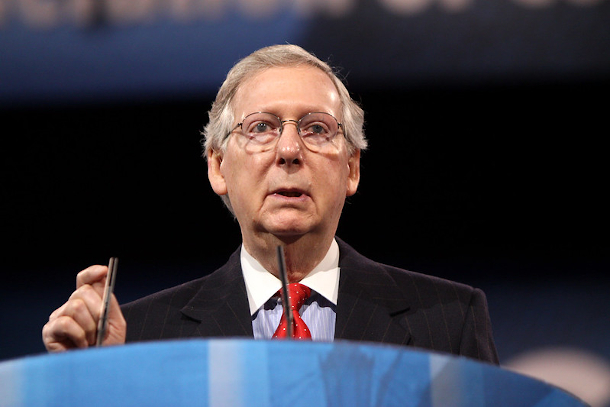

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has blocked many Democratic-led House bills including those for climate action from even reaching the Senate floor. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the international agenda right now. I mean, I assume that President Biden is going to make good on his promise to bring us back into the Paris Climate Agreement. But that's sort of the very least that can be done. What do you anticipate in terms of the international facing part of the new President's approach to dealing with the climate crisis?

ALDY: Saying that we're going to rejoin Paris, you're right, is actually the easy part. The challenge, I think, then is twofold. How do you think about describing what it is we in the United States will do to mitigate our emissions of greenhouse gases? In 2015, as a part of the Paris Agreement, President Obama put forward a mitigation pledge that the Trump administration has effectively walked away from. I think there will be high expectations for what's going to be in a Biden administration pledge. And these are pledges that countries around the world have made and in fact, the next UN climate talks to be in Glasgow, Scotland in November of 2021, are going to focus on how countries are updating and enhancing the ambition of these mitigation pledges. So I think there'll be a lot of attention focused on what the Biden administration will pledge, which then gets to how do you ensure that this pledge is credible, by illustrating the domestic actions you're going to take to implement that pledge. So there'll be a focus, I mean, I remember this back in 2009. Other countries didn't care about what exactly President Obama was saying, say, for our 2020 emissions, when we think about that in the context of the Copenhagen conference. They were focused on the details of the design of the Waxman-Markey bill in the House, they were following some of the emerging discussions about cap and trade legislation in the Senate at that time. They really care about what is in your domestic implementation. That's going to be the real challenge, I think, as the Biden administration moves forward, is reestablishing leadership internationally, but being able to demonstrate credible domestic action to do that.

CURWOOD: So it's too soon to know if there's going to be a Republican Senate or a Democratic-led Senate. To what extent does that outcome of control of the Senate affect what will be climate policy going forward, do you think?

Joe Aldy is an economist and professor of public policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School. (Photo: Courtesy of Joe Aldy)

ALDY: Well, I think it's gonna have a pretty significant impact in the near term on what an economic recovery package looks like. Does an economic recovery package, does it end up being a lean package, if you have to have a Speaker Pelosi working with a Majority Leader McConnell and a Biden White House, where whatever you need to do to get to a majority of votes in the Senate has to bring along Republicans? Or do you have something where you've got, you know, it's not a lot of maneuvering if it's a 50-50 Senate. You know, that means you have to keep every single member of the Democratic caucus and the Independents caucusing with the Democrats, keep them all in line in order to have Vice President Harris break any ties if you're not bringing any Republicans on board. You know, I remember from 2009-2010, from the beginning, McConnell kept his caucus fairly well together in not wanting to support anything we were doing, whether it was the economic stimulus bill, which in the end only had a couple of Republican Senators, whether it was Obamacare, whether it was Dodd-Frank on financial reform, the fact they were never there on cap and trade legislation on climate, which is why then-Speaker Reid never brought a bill to the floor. Because while we were told there were Republicans who liked cap and trade, who had actually sponsored cap and trade bills in the past, they were told by the Minority Leader at the time, McConnell, that they couldn't vote on that legislation. So the question is whether or not McConnell is able to keep his caucus together, and really obstruct action here, or whether or not there are some Republicans who see a future where like, we've got to deal with this problem, and say, I'll work with you. Maybe we work together on something that is sort of more moderate in terms of the policy design. I'm okay if it's sort of moderate in policy design, but it actually makes progress in dealing with this problem. We've, we've had too much inaction legislatively on climate, that I'm happy to make some first steps if it sort of creates momentum and builds some broader coalition that can span the political parties for those subsequent steps that come. But the history is not all that optimistic if we look at what McConnell's done in the past. So I think, I think what happens in Georgia is actually really, really important for the future of climate legislation.

CURWOOD: Joe Aldy is an economist and Professor of Public Policy at Harvard's Kennedy School who advised President Obama on energy and the environment. Professor Aldy, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ALDY: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “How Biden Aims to Amp Up the Government’s Fight Against Climate Change”

- Joe Aldy is on the steering committee of the Climate 21 Project, which made recommendations to the Biden team for a whole-of-government climate response

- The Biden-Harris Transition website on climate change

- About Joe Aldy

[MUSIC: La Musgana, “Las Hilanderas” on Temas Profanos, traditional Zamore/arr. La Musgana, Mad River Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – why the hunted meat millions of American eat can be toxic with lead ammunition. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mike Block, “Old Dangerfield” on Walls Of Time, by Bill Monroe, Bright Shiny Things Records]

Beyond the Headlines

New Jersey is banning single use plastic bags as well as polluting products like foam food products and clam shell takeout boxes. (Photo: Gill King, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

It's time now for a look Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with environmental health news that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Bobby, we're gonna start with a trip back to my beloved ancestral home New Jersey. Last week, Governor Phil Murphy signed the most sweeping restrictions on single use plastic bags, in grocery stores and other retail establishments, plastic bags are going to be phased out by May of 2022.

BASCOMB: Wow, that's amazing. Some 10 million people live in New Jersey, right? That's a big market.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, and that kind of thing. Even more so when a much bigger state like California makes the switch is that manufacturers and retailers tend to put a lot of weight on the new standards, because they don't want to have to manufacture and behave and distribute in two different ways. When the big states tend to be more restrictive they go from resisting that to supporting it. Let's see if that happens with New Jersey. First offense for a merchant is a warning. Once you get up to strike three on plastic bag violations it's gonna be a $5,000 fine.

BASCOMB: Wow, that'll add right up. And of course, New Jersey gave some early warning signs of the plastic crisis back in the 1980s. With all the medical waste washing up on the beaches there.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, medical waste on the beaches in New Jersey along with the sewage spills on beaches, were one of the real warning signs that gave a boost to the environmental movement, resulting in the big Earth Day celebration in 1990. But Jersey, led the way in a bad way with this plastic bag ban maybe it's going to be leading the way in a good way.

BASCOMB: Well, we can hope. What else do you have for us this week?

Virginia seagrass restoration projects have helped grow 9,000 acres of critical eelgrass habitat. (Photo: AJ Johnson, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: We'll go a little bit South of Jersey to the Virginia coastline. There's been a project underway for 20 years to restore seagrass. Seagrass around the world in estuaries long coastlines is valuable habitat, from everything from sharks, to juvenile fish, to sea horses. And in the 1930s, there was a pandemic that wiped out a lot of the seagrass areas along coastlines around the world. Some of them eventually recovered. Virginia and other areas never did. But this project that's been underway for two decades, involves seeding 500 acres with new sea grass. That was a success but the bigger success went to Mother Nature herself, because those 500 acres of newly planted seagrass spread to 9,000 acres because nature did what nature does. It's a small success in the global picture, but it's one that's being used as a model for what can help restore seagrass ecology all around the world.

BASCOMB: A small example but I mean, it is nice to be reminded of the fact that nature wants to heal itself, you know, we just have to sort of give it a nudge in the right direction, if possible,

DYKSTRA: Right and policy and tax dollars, helping to give that nudge in the right direction, also is a contributor to reversing some of our biggest challenges.

BASCOMB: That's for sure. Well what do you have for us from the history books this week?

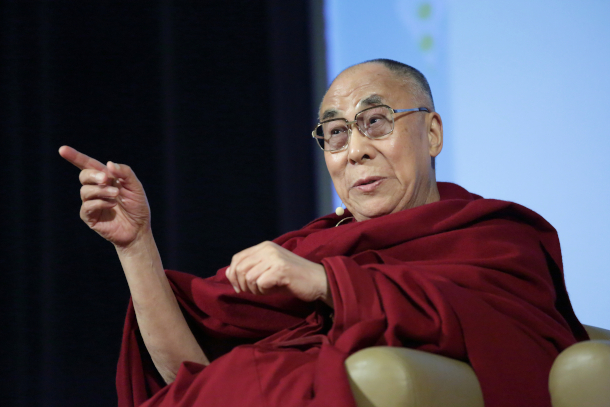

DYKSTRA: Go back to November 10th 1950, 70 years ago Tenzin Gyatso, a 15 year old Tibetan boy was installed as the 14th Dalai Lama. That's 70 years as a leader for peace and a healthy environment. He's spoken out so frequently on climate change and environment. He also has a heck of a sense of humor, if you ever hear him speak.

The Dalai Lama has served for 70 years and has spoken about protecting the environment. (Photo: National Institutes of Health, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Changing America | “‘New Jersey Signs Strongest Paper and Bag Ban in the US”

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientist | “‘Seagrass Meadows”

- The Quint | “‘Dalai Lama, an Environmentalist: A Commitment of 70 Years”

[MUSIC: Yungchen Lhamo “Happiness Is…” on Coming Home, by Yungchen Lhamo, Real World Records]

Lead in Hunted Meat

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service banned lead shot for waterfowl hunting on public lands back in 1991, but lead ammunition is still widely used for hunting other game, like the above white-tailed buck. (Photo: Larry Smith, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Fall is a peak time for hunting deer and moose, and millions of families put that meat on the table with pride. And what they can’t use is often given to food banks. But much of that game is shot with lead ammunition that splinters and contaminates the meat, which can lead to health problems in adults and impair cognitive development and functioning in children. There are alternatives to lead ammunition such as copper, and some 25 years ago the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service banned the use of lead shot to hunt waterfowl. And California recently became the first state to issue a full ban on hunting with lead bullets. But in the majority of states and on federal land it’s still legal to use lead ammunition to hunt deer and moose. And hunted meat goes largely unregulated, according to a recent investigative report from Environmental Health News which is raising concerns about the people who eat it, including food bank patrons , where millions of pounds of hunted game are donated every year. Samantha Totoni, a reporter for Environmental Health News, joins me now.

TOTONI: Thank you so much. It's an honor.

CURWOOD: You've done a series of research papers and articles about lead poisoning. What inspired your investigation into lead in hunted meat?

TOTONI: Well, I grew up in rural Pennsylvania where hunting is very popular. And I know that deer hunters use lead ammunition. But I noticed that in the public health world, lead ammunition wasn't typically included with other potential sources of lead exposure, like the dust from lead paint or contaminated soil and water. I thought that well, maybe that's because it's not really an issue of human health. I began reading the scientific literature and interviewing experts. And it didn't take long to realize, oh, this issue is definitely real. Lead ammunition contaminates meat and is absorbed by the digestive system. And that is significant because there is no safe level of lead in the blood. There's just overwhelming scientific evidence that this problem is real.

CURWOOD: Roughly, how many people hunt for meat in the United States, how many families could possibly be exposed to lead contaminated meat?

TOTONI: So roughly 10 million hunting families in the United States.

CURWOOD: Right now this time of year, for example, there's a moose hunt, there's a deer hunt. What kind of risk are people running if they eat the meat that they get by doing this kind of hunting?

TOTONI: So lead has similar properties to essential elements like calcium, iron and zinc. And this similarity allows led to gain access through cell membranes in the body. The average level of lead in contaminated meat that was donated to food banks in Wisconsin was predicted to cause blood lead levels in children that are associated with a loss of IQ points, decreased cognitive performance and behavioral problems. And those levels of lead for pregnant women have been associated with nearly quadrupling the odds of a miscarriage and increasing the risk of preeclampsia, which is a life threatening high blood pressure condition during pregnancy. Low levels of lead have also been associated with high blood pressure, chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease.

CURWOOD: That's quite a list of toxic consequences. Now, people who are eating the meat that they've hunted or that others have hunted, what happens when that animal is shot with a lead bullet, I mean, how much does the lead disperse throughout the meat that someone might eat?

Ground venison from a deer shot with lead bullets can contain tiny bits of toxic lead spread throughout the meat. (Photo: DC Central Kitchen, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

TOTONI: Well, upon impact a lead projectile from rifle or shotgun can fragment into really tiny pieces, too small to see with the naked eye or to sense when eating. So scientists have used x rays to visualize and count often hundreds of minute lead particles in hunted meat and have detected high concentrations of lead using chemical analysis in terms of hunted meat that's donated to food banks. When people have looked for lead in the donated meat, they have found it. This includes past efforts to x ray donated meat in North Dakota, Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota.

CURWOOD: Now there are some cultures that do subsistence hunting. I'm thinking of people who live in the far north, typically they go out they get a caribou, they get a seal, they eat a lot of meat. So to what extent are cultures that use subsistence hunting with modern weapons? How much have they been exposed to you think?

TOTONI: Well, there was an interesting case study that was published in the scientific literature a couple of years ago of a subsistence hunter in New Zealand, and they found that his blood lead levels were at about 74 micrograms per deciliter of lead in the blood. And for reference, lead in the blood is considered to be elevated at just five micrograms per deciliter. And so the author's provided the hunter with non lead ammunition and his blood lead levels subsequently began falling throughout the period where they were monitoring him.

CURWOOD: Now, give me a ballpark figure, about how much hunted meat goes to food banks each year?

TOTONI: Every year hunters donate over 2 million pounds of hunted meat to food banks across the US and these are great programs that provide critical nutrition for families in need. However, most states do not implement a lead inspection program for the meat even though most of it has been shot with lead bullets. Past efforts to x ray donated meat from food banks in North Dakota, Iowa, Wisconsin and Minnesota have all found lead in some portion of the meat.

CURWOOD: So what states have any are screening hunted meat for lead to keep it from winding up in these food banks where people might unknowingly eat it?

TOTONI: The Minnesota Department of Agriculture administers an inspection program for firearms hunted meat, and their program is reimbursed through their state's Department of Natural Resources. Last year, they screened about 13,000 pounds of donated venison for lead. And they ended up discarding over 940 pounds of it preventing that lead contaminated meat from reaching vulnerable people.

CURWOOD: Sam, it's been more than 25 years that the US Fish and Wildlife Service essentially issued a ban on using any lead and in ammunition aimed at waterfowl. Why do you think it's taken so long for, as you say, one state California to move ahead to ban lead and other hunting.

TOTONI: Bullets that are fired from high powered rifles have been shown to contaminate meat much more extensively than slower moving slugs fired from shotguns. And I think that a ban on lead ammunition for people hunting larger game is likely to influence people who use rifles more than the bans for waterfowl hunting related lead. One difference between now and 25 years ago, is the sophistication of the disinformation campaigns and their ability to reach a wider audience and convince hunters that this is not an issue that they should support.

CURWOOD: So I'm a little puzzled by that. I mean, if there's clear evidence that if hunters go out and they use lead based ammunition, and then they have several pounds of venison or moose in their freezer, that their families might eat over a long period of time that they will be concerned that they will be feeding their families something toxic, as opposed to wanting to deny that there's a problem with lead. What's the issue here is non lead ammunition so much more expensive than lead based ammunition or something?

In terms of price, 100% copper bullets are on par with high-quality lead ammunition. (Photo: Paul Ramos, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

TOTONI: So ammunition that's made out of 100% copper is comparable in price to the high quality lead based ammunition, although it can be twice as expensive as the very low quality lead based ammunition. I've spent a lot of time with hunters who use lead ammunition both in my research and reporting. And what they tend to say is that this really isn't a topic that comes up, and when it does come up that it seems to be coming from groups that they perceive to be anti hunting. And the vast majority of these hunters say that they do want to have information about the potential health effects of lead. Hunters don't want to be impacting the health of their family members or of the people who eat the meat that they donate.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the inspection of game meat is exempt at the federal level. How do you think that impacts the ability of various states to pass regulations regarding meat inspection, their ability and frankly, their willingness?

TOTONI: I spoke with state agencies in the states that are donating the largest volume of venison to food banks every year, including Missouri, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Iowa. And these states told me that the exemption on the federal level has resulted in the exemption at the state level. And meanwhile, it's unclear whether food banks realize there is no oversight of lead contamination in donated meat. In response to questions about accepting lead shot meet, the central Pennsylvania food bank said that they trust the high standards that are set by the State Department of Agriculture and the USDA, who in reality have no standards for this at all?

CURWOOD: What tips do you have to offer hunters who want to avoid getting contaminated by lead in the meat that they kill? I mean, one way of course is to not use lead bullets, but what other choices are there?

TOTONI: Well, there's another option, and that is to avoid grinding their meat. The inspection program conducted in Minnesota is unique in the respect that they do discourage meat processors from grinding meat during firearm season. Instead, they encourage processors to donate small roasts, and loin chops and this is because the vast majority of lead contaminated meat has been ground venison. Lead is very soft as a metal. So even if there's one piece of lead, the steel grinding equipment can actually fragment it and spread it into multiple packages.

CURWOOD: Samantha Totoni's articles on lead and hunted meat and at food banks appeared in Environmental Health News. Sam, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

TOTONI: Thank you!

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Exempt From Inspection: States Ignore Lead-Contaminated Meat in Food Banks”

- Environmental Health News | “Lead in Hunted Meat: Who’s Telling Hunters and Their Families?”

[MUSIC: Bill Price, “Black Dog Blues” on Acoustic Rainbow, volume 24, by Bill Price, PoetMan Records]

Midtown Coyote

The coyote darts across a street in Sacramento. (Photo: Jennifer Berry Junghans)

BASCOMB: The pandemic has put a spotlight on the challenges of parenting in the absence of childcare. But even in an era of remote learning and spotty Zoom meetings we humans probably still have it easier than many animals trying to successfully raise their young. Here’s writer Jennifer Berry Junghans on how a mother coyote manages to eke out a living in the heart of California’s capitol.

JUNGHANS: She dug her den in the dense ivy butting up against the sidewalk in a residential neighborhood of midtown Sacramento. A fresh mound of dirt at the entrance of her 10-foot burrow gave it away, behind caution tape that warned passersby to keep out.

The mother coyote dug her den in dense ivy along a midtown sidewalk. (Photo: Jennifer Berry Junghans)

I meet up with a friend. Within minutes we see her in the parking lot behind us. She rests under a southern magnolia but looks tense.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

She glances left, right, forward, back, like hands on a clock gone mad.

I wonder if she wonders where her two pups are. They’re 11 weeks old now, still small and cuddly to the eye but independent enough to roam the city without her. I think of the possibilities of what could go wrong. I think of her natural habitat along the riparian corridor of the American River, where pups play and tumble on golden knolls as moms watch nearby. A land she knows, rules even. A land where she is at home.

The mother coyote and one of her two pups. (Photo: Guy Galante)

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

But here in the city, it isn’t long before a man barrels into the parking lot and chases the coyote with his car. It’s distressing to see and it brings to life the tension of this scene. Some people are thrilled to share space with her and her pups. Others want them eradicated, like the man in the car. Some are fearful, some are fearful for them, and others pour bags of cat food on the ground, unintentionally habituating her to this booby-trapped urban setting.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

She’s agitated now, jumpy and uncertain as she bolts across the street and wanders through lanes with the swift leggy gait of a moving target. She locks eyes with me as she moves and I swear she can see through me. Moving through the intersection, she boomerangs back across the street, darts through parked cars, then down the sidewalk and heads my way. She sees me, and ducks into overgrown landscaping. I spot her again about 20 minutes later, grabbing a few mouthfuls of cat food. Something startles her. She jumps straight up in the air and lands a few feet away in the street.

“I swear she can see through me,” Junghans writes of the mother coyote. (Photo: Jennifer Berry Junghans)

I think about my choice to come see her. To bear witness to her experience, but my good intention is stripped down naked. I am just one more encounter she must gauge and respond to in this calamity of human activity.

State laws say she can’t be relocated. Even if she could, she may not find adequate food or water. And if she’s moved to a dominant coyote’s territory, he may attack her and kill her pups.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

So the plan is to keep the peace between man and beast, discourage her presence and hope she returns to wilder land.

It’s unlikely this will be the last time a coyote makes her den in midtown. We see them more and more, comingling in the spaces we call home. I wonder if one day we’ll mirror London, where wild red foxes that live among the urban neighborhoods are as common as cats lounging outdoors and people walking their dogs.

Both mother and pup are always on the lookout for danger. (Photo: Guy Galante)

But for now, we have no unity among our understanding of these animals or in our ability to live in harmony with them.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

Eventually, I go home. And her struggle continues on.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

BASCOMB: Writer Jennifer Berry Junghans with her essay, “Midtown Coyote.”

Related links:

- About Jennifer Berry Junghans

- A previous segment on LOE featuring Jennifer Berry Junghans: “The Pear Tree”

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Calisson,” Confectionery, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

CURWOOD: Coming up- What trees can tell us about climate change going back thousands of years. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Carrie Rodriguez, “Seven Angels On a Bicycle” on Seven Angels On a Bicycle, by Carrie Rodriguez & Chip Taylor, Train Wreck Records]

Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Rings

Each tree ring represents a year in the life of the tree. The youngest rings are the outer ones, closest to the bark. This bald cypress is estimated to have been about 700 years old when it was fossilized. (Photo: James St. John, North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

As we enter uncharted territory for humans with climate change many scientists are turning to the past to find answers about what to expect in the future. Shifts in the global climate happen naturally over millennia and they can leave a number of clues behind. At the University of Arizona, paleoclimatologist Valerie Trouet uses dendrochronology to learn about the ancient climate on earth by studying tree rings. Trees are constantly storing information about climatic conditions and some of them can live to be thousands of years old. Professor Trouet’s book, “Tree Story,” is about the science of tree rings and she joins me. Valerie, welcome to Living on Earth!

TROUET: Thank you so much for having me, Bobby.

BASCOMB: So, Valerie, how do you use tree rings to uncover information?

TROUET: What we do is we measure the width of those rings. And that gives us a lot of information about the past. So, for instance, I'm primarily interested in using tree rings to study the climate of the past. And the way that works is that if it's a good year, and the tree is happy, it will grow a lot and grow a wide ring. On the other hand, if it's a very dry year in Arizona, and the trees will be unhappy and form a very narrow ring in that year. And so if you have a 500 year old tree from Arizona, by measuring how wide or narrow each of those 500 rings in the tree is, that'll give you an idea of which ones were the wet years, represented by the wide rings and which ones were the dry years represented by the narrow rings in the past.

BASCOMB: And is it only precipitation that you can uncover by looking at these tree rings? What other information is available to you?

TROUET: Yeah, so that's a really good question. So I give the example of trees in Arizona where it's dry. But it's a very different story, for instance, in the European Alps, or in Canada, or Alaska, where it never really gets too dry for trees to grow a lot or to be happy, but it can get too cold. So the trees there record temperature, how hot or how cool it is, rather than how dry or how wet it is. Now the other thing is that we're not limited to living trees alone, we can really study the rings, and pretty much anything that's made out of wood, as long as it has enough rings in it. And so through the process of matching the patterns in the ring that I was talking about earlier, the patterns in the tree rings, we can also date wood that we don't necessarily know when it was used. But by matching it to the patterns of living trees, we can date when, for instance, archeological sites were built or when historical buildings were built, or when paintings were painted, or when musical instruments were made. So we can date a lot of wood material very precisely to the exact year by using dendrochronology.

BASCOMB: So, the idea there is if you have enough trees that overlap in years that they were living, you can actually look back quite far in time. And from what I understand, you can even use charcoal, you know, pieces of trees, as is the case from the Four Corners region. Is that right?

TROUET: Yeah, that's right. And I think that's really amazing as long, again, as long as they have enough rings in them, those pieces of charcoal. So, the structure of the wood is preserved in the charcoal, so you can still see the rings in the charcoal.

Dead trees in the Barrenbox Swamp Near Griffith, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo: Gregory Heath, CSIRO Science Image, CC BY 3.0)

BASCOMB: And then, you know, physically how do you get a core from a tree? And does it hurt the tree?

TROUET: Yeah, good question. Actually, I should have mentioned this much earlier that, to sample trees as dendrochronologists we don't cut down trees, it's very important to know that when we take a sample of it with a hollow core, so we have a core, it's about a quarter of an inch in diameter that we core by hand into the tree. And that allows us to extract a sample. It's a bit like a biopsy or drawing blood from a tree. And a sample you can think of it as like it's about the length and the diameter of a pencil. So you extract a pencil out of the tree that shows all the tree rings on it. And it doesn't hurt a tree because we have to think of a tree, at least a stem of a tree. You know, 99% of the stem of a tree is dead already. The only living part of the stem of a tree is a very thin layer of cells, we call the cambium cells in between the bark and the wood. So everything that's wood is dead already. And so when we sample the tree with our core, you only take a sample of about a quarter of a diameter out of the living tissue, out of the cambium, everything else is dead already so it doesn't harm the tree at all.

BASCOMB: Now, you say that most times you just take this sample and it doesn't hurt the tree, but I actually took a dendroclimatology class in graduate school and heard this story that I kind of thought was a bit of urban legend, but you confirm it in your book, of a researcher who got his instrument stuck inside of a tree so he applied to get a permit to cut it down. What happened? Can you tell us that story?

TROUET: Yeah, that's a very unfortunate story of Don Currey, who was a graduate student in the 60s, in the early 60s, who was interested in studying the Bristlecone pines that grow on the border between California and Nevada in the White Mountains. He was interested in studying them to look at past glacier activity in that region. It's not entirely clear why he switched from a bore to cutting the tree, but he started off with a bore, but for some reason...I mean, these are... these bristlecone pines are very gnarly and complex trees. They're not easy to core. But for some reason, he decided I'm not going to core his tree, he applied for a permit from the Forest Service to cut it down. He got the permit, cut it down with a chainsaw, and then brought the cookie sort of, a disk from one particular tree that he had in mind, brought the cookie back to his hotel room at night, and then started counting the rings in the sample from the tree that he had just killed. And it turns out that he had just killed the oldest living tree on Earth at that point in time, that we were aware of. So he killed the bristlecone pine, he cut it down, that was almost 5000 years old. Luckily, in 2012, one of my colleagues at the University of Arizona in the tree ring lab found another bristlecone pine that was even older than the one that had been killed. So the one that had been killed was not the oldest living tree on Earth. The now oldest living tree on earth is more than 5000 years old, it was 5062 years old when it was sampled in 2012. And its location and its identity are kept a secret, so that no one will hurt it.

BASCOMB: And you were also a part of a team that sampled trees from historic buildings in ancient Rome. What did you uncover with that work?

TROUET: It's interesting, because from Roman times in Europe, the aboveground wood is no longer around. That's been the case for a very long time now. But what is left in terms of Roman wood is wood that they use to build and align their water wells, because that wood was underwater for most of history. And so when it's underwater, it's preserved in anoxic conditions, in conditions without oxygen. And so bacteria cannot get to it. So we dated a lot of that archaeological wood from Roman times. And then we used it, combined with wood from living trees and from historical buildings, to develop a climate reconstruction for Europe going back 2500 years. And what we then found is that during Roman times, that this was a period of a very fluctuating climate, so of severe changes in climate. It would be wet for a couple of decades, and then dry again for a couple of decades, wet again for a couple of decades. So, we then hypothesized that this climate variability, these extremes in the climate might have contributed to the fall of Rome, or the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire.

These bristlecone pines in Clear Creek, Colorado, are estimated to both be over 1,000 years old. (Photo: Barry Dale Gilfry, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Wow, it's so interesting, what you can infer from these tree rings. You also talk in your book about Genghis Khan, and the tree rings that were dated from that time. Can you tell us about that?

TROUET: Yeah, that's one of my favorite stories. That's work by my colleague, Amy Hessl from University of West Virginia and Neil Pederson from from Harvard forest. They went to Mongolia, sampled some extremely old trees there, and then also used them to reconstruct the climate of the past. Now in Mongolia, what they were able to reconstruct is drought and wet periods in the past. And so when you think of Mongolia, when you look at the history of Mongolia, the period when Genghis Khan came to power is a very interesting period in Mongolian history. So when they looked at their climate reconstruction, their drought reconstruction, for the period, I want to say in the early 13th century, they noticed that this period that Genghis Khan was able to build his empire and expand his empire was actually one of the wettest periods in Mongolian history. It's almost an opposite of the story of the Roman Empire, where climate helps to explain, or is one of the factors contributing to the fall of Rome. In Genghis Khan's case, it's the other way around, where the really good climatic conditions, climate conditions, help him to build this and expand his empire.

BASCOMB: Well, this is just so fascinating, but what for you, what are some of the biggest discoveries of dendrochronology thus far?

TROUET: So these kind of collaborative research projects is what I find very exciting. A beautiful example is that of colleagues of mine who studied the ghost forests in the pacific northwest of the United States. So, ghost forests are forests of standing trees, standing dead trees. So, these are trees that died a few hundred years ago, but are still standing. And some of my colleagues sampled them, tree ring dated them, in four of those ghosts, forests and discovered that they all died in the exact same year, sometime in the winter between 1699 and 1700. And so, their hypothesis was that there was an earthquake in that year, that caused the ground to sink and salt water to come in, and so kill all of those trees at once. But when it came really interesting is when simultaneously in Japan, so on the other side of the Pacific, there were environmental historians who studied the history of tsunamis in Japan. And so they had found through going through written documents in Japan, that in the winter of 1699, to 1700, actually, on January 26, of the year 1700, there'd been a tsunami in Japan that had flooded pretty much the entire coast of Japan. So, there were records of shipwrecks, records of agricultural lands that had been flooded, and so forth. But there was no record of anything that might have caused that tsunami. So they called it the orphan tsunami, because they knew there was a tsunami, but they didn't know where it was coming from. And it wasn't until those environmental historians from Japan started talking to the dendrochronologists in the Pacific Northwest, on the other side of the Pacific, that they put one and one together and realized that it was a massive earthquake in the Pacific Northwest that caused the trees there to die. But that also went all the way across to Japan, and then caused a tsunami on that side of the Pacific. And so I think that's a really beautiful story to demonstrate what all we can find out with tree rings, and by collaborating with other scientists. But also it's a warning, because until that study, they didn't realize that earthquakes of that magnitude could occur in the Pacific Northwest. I mean, yeah, it must have been an earthquake of magnitude 8 or 9 to reach all the way to Japan. So, it's a warning for the possibility of environmental conditions that are possible.

A toolbox full of instruments used for dendrochronology at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, looking down the road a bit, what excites you most about possible applications for dendrochronology?

TROUET: One, I think, benchmark study, that was published about 20 years ago in 1998, and we keep seeing the same thing ever since, is the extraordinary character of the current climate change, and specifically how the current warming, global warming, is compared to the past. So, you know, we've been measuring the climate temperatures and precipitation with instruments, you know, let's say, since the early 1900s, on a global scale. The problem is that that's also the period after the start of the Industrial Revolution, since we've also been really messing with the climate. So by looking at instrumental data alone, we don't really have a good record of what natural climate variability is like, we only have a record of what the climate is like when we are influencing it as humans. So, to go further back in time to look at natural climate variability, that's where tree rings come in. So, they allow us to put the current climate change in a much longer-term context. And for instance, that hockey stick study shows that the current warming since the 1900s is really unprecedented over the last 1000 years. And it's called a hockey stick, because it describes the curve of the global temperatures over the past 1000 years. And so it slowly cools since 1000, to about 1850, and then there's a really steep increase in temperature since then. This steep increase, you keep seeing in the tree rings. Wherever, wherever I go, where the trees are sensitive to temperature, you always see an unprecedented warming in the 20th century, it's everywhere. You know, dendrochronology, really, we're able to study forests of the past, we're able to study climate of the past, we're able to study archaeology and human history. And so the link between those three, it's really, it's dendrochronology. It sits at the nexus between ecology, climatology, and archaeology. And so, as we move forward in a warming world where, you know, climate is gonna have a very big impact on ecology and ecosystems, it's also gonna have a big impact on humans, being able to provide a longer term and historical context to what we're seeing here. What is happening here and now, I think is exciting.

BASCOMB: Valerie Trouet is a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona and author of Tree Story. Valerie, thank you so much for sharing all of these tree stories with us.

TROUET: Thank you so much for having me, Bobby.

Related links:

- More on author Valerie Trouet

- Click here to read more about Tree Story

- PBS.org | “Dendrochronology”

[MUSIC: Time For Three featuring Jake Shimabukuro, “Happy Day” on Time For Three, by N. Kendall/arr.Rob Moose, Universal Music Classics]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth