January 8, 2021

Air Date: January 8, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Georgia's Green and Brown Voters

View the page for this story

After the historic turnout of the 2020 Presidential election, all eyes turned to Georgia for the twin runoff races that would determine control of the Senate. Democrats pulled off victories for both Senate seats and gained control of the chamber, thanks in part to Georgia's environmental voters, who are statistically more likely to be people of color and young, and to live in urban centers. Nathaniel Stinnett, founder of the Environmental Voter Project, joins Steve Curwood to look at how the winning margin for the Senatorial victors was boosted by those unlikely voters who rank the environment as their top priority. (07:21)

ANWR Oil Leasing

/ Alex DeMarbanView the page for this story

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge likely has billions of gallons of oil under it and for decades it’s been one of the most high-profile environmental battles. Despite opposition from conservationists and native peoples, a judge allowed the Trump Administration to proceed with a January 6 auction of oil and gas drilling leases in the refuge. Anchorage Daily News Reporter Alex DeMarban joins Bobby Bascomb to talk about the ongoing litigation over ANWR. (06:34)

BirdNote®: The Oilbird’s Lightless Life

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

Oilbirds live their whole lives in darkness, emerging from the South American caves where they live only at night. BirdNote®’s Ashley Ahearn shares how oilbirds use echolocation and night vision to forage, and how the bird got its unique name. (01:51)

Activism Cuts Plastic Waste in the Bahamas

View the page for this story

As an island nation, the Bahamas finds itself drowning in plastic carried from far away by ocean currents as well as from its tourism industry and domestic use. Environmental activist Kristal Ambrose saw firsthand the profound harm plastic waste can cause to wildlife, started a nonprofit and successfully lobbied her government to ban all single-use plastics in the Bahamas. She’s been recognized for her work with a 2020 Goldman Environmental Prize and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about the inspiration for her organizing and further efforts to curb plastic waste and pollution. (10:45)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Steve Curwood go Beyond the Headlines to talk about how scientists are taking a close look at Arctic ‘browning’ of tundra plants in addition to greening as the region warms. And in another climate consequence, Norfolk, Virginia is already experiencing such sea level rise that its stormwater systems are becoming overwhelmed. In the history calendar, it’s 50 years since Marvin Gaye released “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”, his song which decried air and water pollution, radiation, and other environmental ills and became an R&B and pop sensation. (04:40)

Remembering Barry Lopez

View the page for this story

Barry Lopez, who passed away on Christmas Day 2020, is being remembered as a beloved environmental writer who authored National Book Award-winning Arctic Dreams and many other works. His final book, Horizon, is a sweeping account of his lifetime of traveling the world and seeking the perspectives of diverse cultures as humanity faces growing challenges. Barry Lopez spoke with Steve Curwood in 2019 about striving towards a more humane and hopeful future. (15:54)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210108 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Kristal Ambrose, Alex DeMarban, Barry Lopez, Nathaniel Stinnett

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Peter Dykstra

HEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

New mostly young and black environmental voters were key to Georgia’s recent Senatorial wins.

STINNETT: 6,700 of these unlikely-to-vote environmentalists who we know voted early, didn't even vote in the presidential election. Nobody skips a presidential election, and then votes in a runoff, this is completely unprecedented!

CURWOOD: Also, President-elect Biden could block last minute plans to allow drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

DEMARBAN: Biden has said he opposes drilling there. In fact, his campaign that said he wants permanent protections in the refuge, which would be no drilling ever. And that's another thing that our Alaska Republican delegation has feared with Democratic control of both branches.

CURWOOD: That’s this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Georgia's Green and Brown Voters

Many credit Georgia’s unprecedented voter turnout to voting rights groups and activists, including Stacey Abrams, former Minority Leader of the Georgia House of Representatives. (Photo: Callie Giovanna, TED, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

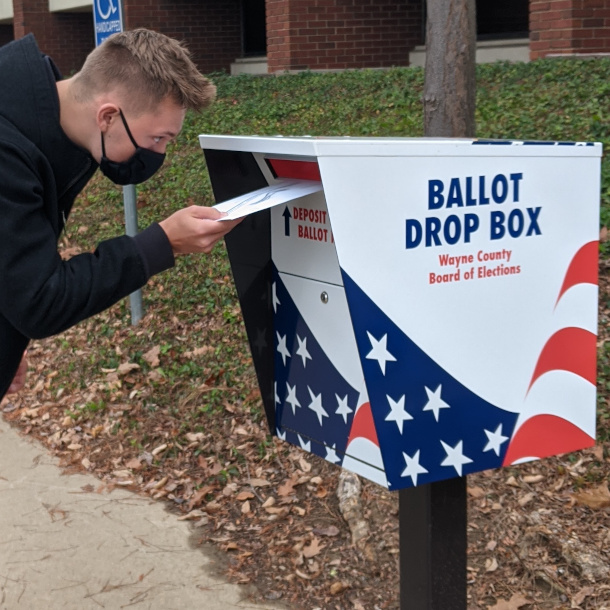

Voters most likely to rate the environment number one in their concerns are young, black and brown, and they were key for the recent two senatorial wins in Georgia that gave the majority to Democrats, says Nathaniel Stinnett of the environmental voter project. He says data already available from the early voting in Georgia shows these environmental voters even outpaced participation by the general electorate.

Nathaniel Stinnett joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

STINNETT: Oh, thank you so much for having me. I always love being here.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about some of the numbers that you've seen from the Georgia runoffs. And what do they tell us?

STINNETT: We just saw record breaking turnout in Georgia, more than 4.4 million people voted. And to provide some context, Steve, there was record breaking turnout in Georgia for the presidential election, and only 5 million people voted. So I mean, we're gonna get to 90% of what presidential turnout was, of what record breaking presidential turnout was, for Georgia in this runoff, which was really extraordinary. Moreover, we know that environmentalists really, really punched above their weight. So, when we look at these environmentalists whom we identified at the environmental voter project, we know that before election day even arrived, Steve, 51% of them had cast early ballots, as opposed to only 40% of all registered voters had voted early in Georgia. So, before election day even arrived, the environmental movement was outpacing all registered voters in Georgia by 11 percentage points. And that was because there was historic Black turnout. I think a lot of your listeners are probably aware that there was historic Black turnout in Georgia. But what's really important to understand is two things. One, by historic we mean it will likely end up that more Black voters voted in this runoff than voted in the presidential election in Georgia.

The 2020 Presidential election saw an all-time high voter turnout nationally, as well as in Georgia, where around 5 million people cast ballots. In Georgia’s run-off, the total ballots are expected to nearly match that number. (Photo: Karri VanKirk, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Really?

STINNETT: Really. Votes are still being tallied, but it's going to be darn close, and we may even see higher turnout than we saw in the presidential. The second thing is college educated youth turned out huge. And those two groups? That's what the environmental movement looks like in Georgia, Steve, and they turned out big time in this runoff.

CURWOOD: So, part of your work is to encourage people who don't or who haven't voted in the past. To what extent do you think that your work got people out to vote in this runoff that had never voted before?

STINNETT: So, we were targeting 382,000 unlikely-to-vote environmentalists in Georgia. And what we know is that 30% of them, 115,000, voted early. We know that because we can see that in public voter files in Georgia. 6,700 of these unlikely-to-vote environmentalists who we know voted early, didn't even vote in the presidential election. Nobody skips a presidential election, and then votes in a runoff. This is completely unprecedented. And we saw almost 7,000 environmentalists do that in Georgia. To reiterate, Steve, these people weren't supposed to vote at all. They were unlikely voters, which means they had either never voted before, or they had only voted in presidential elections before. And to have 30% of them vote early. That is truly extraordinary, and it's not just because we at the Environmental Voter Project do a good job. The entire environmental movement did a great job. And Black churches did a great job. And youth organizations did a great job. I mean, this was historic environmental turnout.

CURWOOD: Now, you don't know what the party registrations or party affiliations of any of your voters are in Georgia, Nathaniel, but what is your best take as to who they might have been? How many of them identify as GOP?

STINNETT: So, it's hard to put our finger on it. And it's not because I'm trying to be squirrely, it's because we have a 50-state patchwork of how voter files are put together. For instance, in Georgia, we don't know the party affiliation of any of the environmentalists we're going after. So, that's really hard to put a finger on. What we know from what we just saw in 2020 is that Republicans will go where the votes are, just like Democrats will, because every politician wants to win elections. I mean, we know from this fall, when Republican senators in Montana and Colorado were instrumental in pushing through the Great American Outdoors Act. We also know from Republicans who were running for Congress in Florida, that they will lead on the environment. But are there many more Democratic voters who care about climate and the environment? Oh, yeah. Yeah, you better believe it. But what we see in our data is that the environment is, at least not yet, an ideological litmus test for Republicans. Rather, it's more of a strategic consideration. They will not lead on climate or the environment, if they don't think it's necessary, because then they can get all this fossil fuel money and support. But where it is necessary to lead on the environment, where it is necessary to lead on climate change, in order to win an election. Well, Republicans will do what any politician does, and that is go where the votes are.

Nathaniel Stinnett serves as Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Environmental Voter Project)

CURWOOD: So, some would say that Joe Biden owes his path to the White House to Black people, Jim Clyburn speaking up in South Carolina, Stacey Abrams in Georgia. What, if anything, have you seen in your in your surveys that tells you what Mr. Biden needs to do to keep that coalition behind him?

STINNETT: We really need to think of this on two axes. It's how do you get people from a certain community to really like you a lot. But also, how do you get the disengaged members of that community to engage. Joe Biden has a significant level of support from the Black community. But it is never going to be enough, unless he also makes sure that ones who have been previously disengaged from politics remain engaged. And for that he needs to lead in an aggressive and powerful way on environmental justice issues. It's very clear in all of our data, that Black Americans and Latinx Americans don't care deeply about the environment because of some fluke. They care about it because coal fired power plants aren't put in lily-white suburbs. They're put in communities of color. And environmental injustice is the main driving reason why the environmental movement looks the way it does look, as we've been discussing today, Steve. And so I am really confident that President Elect Biden not only needs to, but it would be politically smart for him to lead on environmental justice issues and make sure to get cleaner air and cleaner water and climate resilience in communities of color and our big urban centers.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel Stinnett is the founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Thanks so much for your time today, Nathaniel.

STINNETT: Thank you so much for having me, Steve. Happy New Year.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Environmental Voter Project

- Listen to LOE’s most recent segment with Nathaniel Stinnett

- The New York Times | “Georgia Highlights: Democrats Win the Senate as Ossoff Defeats Perdue”

ANWR Oil Leasing

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is one of the largest national wildlife refuges in the United States. It is considered one the country’s last untouched areas of wilderness. (Photo: Hillebrand, USFW, Flickr, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: So, Steve the elections in Georgia are a political game changer with Democrats in control of both houses of Congress and of course the presidency. But the Trump administration still had time for a last minute push to open up ANWR.

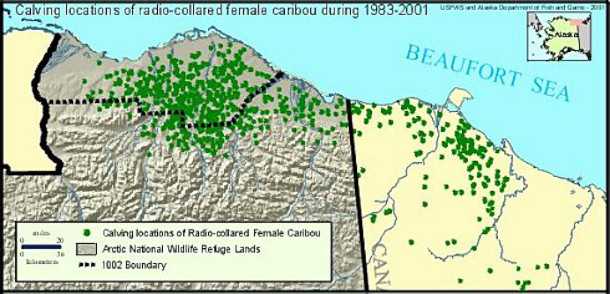

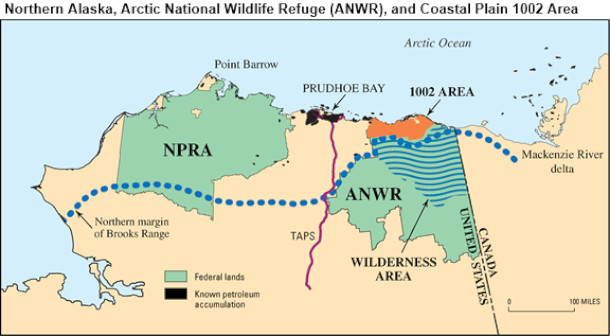

CURWOOD: Right, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, now there are potentially billions of gallons of oil under it and Republicans and the fossil fuel industry have been eyeing ANWR for decades.

BASCOMB: Exactly, but it’s a national wildlife refuge and a crucial habitat for wildlife like the porcupine caribou herd, which has the longest land migration on earth, 1500 miles long. And for the Gwich’in indigenous peoples, it’s known as “sacred land where life begins.” But supporters of oil drilling, especially Alaskan Republicans, claim opening ANWR to drilling is key to revenue and job creation. And as you said, this fight does goes back 4 decades but in 2017 the Alaska congressional delegation was able to get a sale of oil leases into the budget resolution bill, claiming it would generate 1 billion dollars of revenue for the government. Then in the next year several conservation and indigenous groups sued the Trump administration to try to block oil leasing in ANWR. But despite the lawsuits the Bureau of Land Management finally scheduled some ANWR lease sales for this January 6th. And on January 5th U.S. District Court Judge Sharon Gleason denied request for an injunction that would have delayed the bidding process until after president Trump leaves office. For more, let’s bring in Anchorage Daily News Reporter Alex DeMarban. Welcome to Living on Earth, Alex.

DEMARBAN: Thanks. Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, what exactly did judge Gleason say in this case? What was her rationale for ruling in favor of the Trump administration?

DEMARBAN: Gleason, interestingly, didn't I think focus on some of the arguments that the conservation groups had made, such as that the Trump administration did not study the emissions appropriately, that would come from oil development. So she instead focused on the fact that the conservation groups did not say that there would be immediate and irreparable harm, which was something that she needed if she was going to immediately halt the issuance of the leases. So rather than focusing on whether environmental steps have been overlooked, she had to focus on whether there was going to be irreparable damage caused by leases being issued to companies before she could make a decision. And she said that she had time to make a decision, if any such damage were to occur, she can make that decision before that damage might occur. So she focused on a very narrow part and said, it's not ready right now to be stopped.

Loss of sea ice due to global warming threatens the polar bears that live in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Environmentalists and scientists believe that drilling for oil and gas in the refuge will only exacerbate the effects of climate change and further endanger polar bears. (Photo: Steven Arstrup, USGS, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: So basically, she's saying that the lease sale itself doesn't pose any imminent danger, because the company would still have to get another permit to begin seismic testing and then undergo, you know, an environmental impact statement, all of which I would think could take many years. Do I have that right?

DEMARBAN: Somewhat, she's saying that, yes, a lease sale won't cause immediate harm, and she can make a decision if it were to cause any harm before then. Not necessarily in years but maybe in months, for example, there's a seismic program that might take place this winter. And before any irreparable harm is done, she says she still has time to make a decision. She also said that that seismic exploration program isn't even approved yet. So there's nothing she can rule on there but she invited the conservation groups to try again, if they want to stop that once it is approved and she would consider that request. So it's not an into the case. It's just a very small part of the case in which she said, at least sale itself doesn't cause damage to the land, or to values in the refuge immediately.

BASCOMB: Alex DeMarban is a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News.

DEMARBAN: Yeah, thanks for having me. I appreciate it.

BASCOMB: So, Steve as Alex just told us drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge isn’t necessarily going to get started any time soon. But this decision keeps the possibility alive.

CURWOOD: Right the lease sales began the very next day after Judge Gleason gave her decision. What happened there?

BASCOMB: Well, there were 22 tracts of land available for lease sales but only half of them were actually purchased and none of the big oil companies put in a bid.

Caribou calving takes place in the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where oil and gas drilling leases are underway. (Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So, Bobby, tell us why.

BASCOMB: Well, there could be a few factors here. First, bowing to pressure from conservation groups, half a dozen financial institutions, including Bank of America, have pledge to not fund any Arctic drilling. So that means, extraction companies would largely have to invest their own money to work in the Arctic. And the price of a barrel of oil is quite low right now so there’s not a driving economic incentive for them to take on drilling in a remote controversial region like ANWR.

CURWOOD: Ok, so who did buy up these rights then?

BASCOMB: Two small companies bought one parcel each. One is Regenerate Alaska, which is an affiliate of an Australian oil company. And the Knick Arm Services, which appears to be a LLC based in Alaska but very little information is available on it. The biggest bidder was the State of Alaska itself. Oil is of course a big business in Alaska, the government relies heavily on extraction for both revenue and jobs. So the state-owned Alaska Economic Corporation bought the rights to 9 parcels of land, totaling roughly half a million acres. They paid the minimum of $25 per acre but will actually get half that money back as part of the sale.

CURWOOD: So, this isn’t exactly the windfall that the Trump administration hoped it would be.

BASCOMB: No, certainly not. The administration hoped this sale would bring in on the order of a billion dollars but it’s actually totaled less than 15 million. Mr. Trump himself has made opening ANWR a key part of his plan for expanding domestic oil production. So, this lack luster sale must come as a disappointment though of course he has far bigger concerns after the events of this week.

CURWOOD: Right! Well, what if anything can President Biden and the new Democratic majority Congress do to reverse course on drilling in ANWR now that there are a few oil leases?

The image above shows the area where oil and gas leases have been sold. The 1002 Area covers about 1.5 million acres, accounting for about 8% of the total area of ANWR. (Photo: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: President-elect Biden has routinely said that he opposes drilling in the Arctic and he’s opposed to allowing new leases on any public land for that matter. There are some legal hoops that the lease buyers still need to jump through so if the sales aren’t finalized by inauguration day it’s possible that they could be blocked. A more long lasting solution though would be for the new congress to reverse the 2017 legislation that allowed the sale to move forward to begin with. And then of course work on a law to permanently protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

CURWOOD: I imagine there will be a lot things on their agenda.

BASCOMB: Yes, no doubt.

Related links:

- Washington Post | “Trump Auctions Drilling Rights to Arctic National Wildlife Refuge On Wednesday”

- Alaska Public Media | “Here’s What You Need to Know About the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s First Ever Lease Sale”

- Anchorage Daily News | “As Arctic Refuse Oil Sale Looms a Court Will Consider a Request To Stop the Trump Administration From Issuing Leasing”

[MUSIC: John Scofield, “Green Tea” on A Go Go, The Verve Music Group]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The 2020 Goldman Prize winner for the Island Nations on her successful quest to ban single use plastic in the Bahamas.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joey Alexander, “Draw Me Nearer” on Eclipse, Motema Music LLC]

BirdNote®: The Oilbird’s Lightless Life

Oilbirds have excellent night vision, due to having the highest density of rods of any known vertebrate. (Photo: Roger Alham)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

CURWOOD: Birds have evolved in many surprising ways to adapt and thrive, from swimming penguins to hovering humming birds. Ashley Ahearn of Birdnote reports on a South America bird that shares an adaptation with bats.

BirdNote®

The Oilbird’s Lightless Life

[Calls of Oilbirds: http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/4559]

Oilbirds roost in caves, but need to live near forests in order to obtain food. (Photo: Roger Alham)

These are the freakish snarls of the Oilbird, which spends its whole life in the dark. These birds live in caves in Trinidad and South America and fly out at night to search for food. The Oilbird is adapted to this lifestyle. It uses echolocation — like a bat — to find its way in the pitch-black of its cave. [Oilbird echolocation clicks and calls] And the birds have excellent night vision — rivaling that of an owl’s — to help them forage after dark. Fossils suggest that the Oilbird diverged from other bird families more than 50 million years ago. It has no close living relatives. [Oilbird echolocation clicks and calls] The Oilbird isn’t black, as its name might suggest. It’s actually a rich brown with large white spots. It has a hooked beak, like a hawk, but it’s not a meat-eater. The Oilbird lives on tree fruit, especially palm nuts and avocados, which it finds thanks to its keen sense of smell. This diet, rich in fat and oils, leads to plump chicks… and the name… Oilbird. In fact, humans used to boil down the birds to make oil.

Oilbirds’ favorite fruit is the fruit of the oil palm. These fruits can be collected and boiled down to extract their fat for use as fuel. (Photo: Tony Palliser)

[Calls of Oilbirds: http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/4559]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

First set of bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York: Oilbird calls [4559] recorded by David W Snow in Trinidad and Tobago's Arima Valley, in 1959.

Oilbird echolocation clicks and calls recorded by Andrew Spencer in Ecuador.

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

Editor: Ashley Ahearn

Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone

Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill

© 2015 BirdNote January 2015 / January 2020 Narrator: Ashley Ahearn

ID # oilbird-01-2015-01-27 oilbird-01b

https://www.birdnote.org/show/oilbirds-lightless-life

CURWOOD: For pictures navigate over to the Living on Earth website, LOE dot org

Related link:

Find out more on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Zoe Lewis, “One Night” on A Cure For the Hiccups, by Zoe Lewis, Dog called “dog” music]

Activism Cuts Plastic Waste in the Bahamas

2020 Goldman Environmental Prize winner Kristal Ambrose at a beach cleanup in the Bahamas (Photo: Dorlan Curtis Jr. and Jawanza Small)

BASCOMB: Plastic waste is an overwhelming problem in the Bahamas. Ocean currents routinely wash tons of foreign plastic on to the beaches of the island nation. Add in waste from the tourism industry and domestic use and the Bahamas finds itself drowning in plastic. Without enough space and resources to recycle the plastic, the Bahamas has been forced to burn or bury much of it in landfills. Environmental activist Kristal Ambrose was struck by the profound harm to wildlife caused by plastic waste. So, she started a non-profit to fight it and successfully lobbied her government to ban all single-use plastics in the Bahamas. For her work, Kristal is the 2020 Goldman Environmental prize winner for Island Nations. She joins me now. Kristal, welcome to Living on Earth.

AMBROSE: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, what did the problem of plastic waste look like in the Bahamas when you were growing up, and before you started working on this issue?

AMBROSE: That's a really great question, and I couldn't tell you because you know, when you're not aware of something, it doesn't jump out at you. So it took me working in the field of marine science to realize that it was an issue. And it wasn't until 2008 when I worked at a local aquarium, and we had this sea turtle exhibit. And we noticed that one of our sea turtles, she had isolated herself from the population, she wasn't eating, and we called in a marine vet. So he came in and he gave an x-ray, and noticed that she had some intestinal blockage. So for about two and a half days, we went into the rectum of this turtle and we pulled out plastic piece off the plastic piece, candy wrappers, fragments. And my goal, or my job at the time was to hold down her front flippers. And if you know anything about sea turtles, when they come up on the beach to nest, they have the salt glands in their eyes, where they produce tears to protect their eyes. So because the turtle was on land, I was holding the flippers down, she was crying, I was crying, and I was like, "I'll never drop another piece of plastic on the ground again." You know, so I saw right then and there the direct impact of plastic and what it had on wildlife. But even though I made this vow to stop littering, because I was guilty of throwing, you know, candy wrappers or things on the ground, I was still a big plastic offender. So it wasn't until 2012, when I got this opportunity of a lifetime to sail across the Pacific Ocean to study the western garbage patch. So I lived on a sea boat, on a sailboat for nearly 20 days with a crew of about 14 people. And there was nothing around us except wildlife and waste. It was just us and garbage! And just seeing it firsthand, and I remember feeling so angry, like "Why are humans doing this? Who's trash is this?" And then once we started dissecting all that debris, and I started to see the toothbrushes and the combs and the plastic forks, and I realized that it was my waste, it was things that I used every day in my life, and that I was a huge part of the problem, and equally so, I could be a part of the solution. So that was the awakening for me. So I can't say if there was a difference growing up compared to now, but that's when I really took notice.

To inspire passion for their oceans, Kristal takes Bahamanian youth swimming, often for the first time. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BASCOMB: Kristal, the Bahamas are obviously an island chain, you know, and they're, I would think perfectly situated to be collecting a lot of this ocean plastic that you saw on your trip. Can you tell me about that, please?

AMBROSE: Definitely. So it's estimated that by 2025, the Bahamas is set to have some 687 million metric tons of plastic debris accumulating on its shorelines. That number is alarming because that's where we live right? Soon, the amount of plastic will displace the biomass of the people that actually live within these islands. So a lot of the debris that we find that wash up in the Bahamas, because of our proximity to the North Atlantic Gyre and the Gulf Stream, we get a lot of debris that comes up through there. So we get things like octopus pots that wash off the coast of West Africa, from their fisheries, we get things from the southern Caribbean, like water bags, or detergent containers that wash up on our beaches. In addition to the usual suspects, you know, we have oil jugs, and ropes and packaging straps from the fishing industry. And all of that is obviously fragmented. And then we have copious amounts of microplastics in our sand. So that's how a lot of it gets there. And on top of that, this is a multifaceted issue. We're dealing with the waste that we generate, locally from the tourism industry, from the locals that live there, from the plastic that washes onto our shores. And now as climate change intensifies; last year, we had hurricane Dorian. And we have to now deal with disaster debris, and that alone left behind 1.5 billion pounds of of disaster debris, you know. So it's a serious issue.

BASCOMB: And what kind of capacity does the Bahamas have for dealing with it, for recycling or processing that waste in a useful way?

AMBROSE: Right now, I think there's a company in Nassau, they just took over the landfill. So I think they have some plans for recycling. But when we look at it, what makes this really challenging is the geography of the Bahamas. We're many islands, you know, scattered across the Atlantic, and there's no infrastructure. So even the question if we do all these cleanups, where does the garbage go? It goes to the landfill where it's deliberately burned, where it's not properly engineered. So right now we don't have the infrastructure or, or the capacity to deal with this waste.

A beach in the Bahamas (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BASCOMB: Which makes the case for getting to the root of the issue and not just the cleanup of it. So you came back from this trip and you are fired up on plastic. What did you do? What was your first step in tackling this issue?

AMBROSE: Well, my first step! When I came back from the trip, I was like, "Well, that was fun! I'm going to go back to scuba diving, and counting fish and you know, studying coral reefs." And the more and more I learned about plastic pollution, I couldn't look away. So I was really interested in understanding how much plastic was actually on Bahamian beaches. So I started a citizen science project with the help of my friend Carolyn Box from Five Gyres. And we looked at how plastic was moving over space, and over time on beaches in the Bahamas. And I was working at a research station at the time, and I realized, you know, in the science field, there's a lot of science that is done, but the community is often left out. And I wanted to bridge that gap between community and science. So I got students to come to the beach with me to help me collect data. So we would go to the beach, collect data, and every time I was on the beach, I would jokingly say, "This is the Bahamas plastic movement!" And I wouldn't think anything of it, you know, it was just me on the beach, we were doing research. And I kept having these manifestations and visions of this nation, you know, these people walking with me to create this nation free of plastic debris. And I was like, I'm gonna start a nonprofit. And I did! And that's how that's how it came about.

BASCOMB: So you started this nonprofit, and what did you do with it? How did you lobby the government, and for that matter, local businesses and things to get on board with this?

Kristal and other volunteers clean up plastic waste on a beach in the Bahamas (Photo: Dorlan Curtis Jr. and Jawanza Small)

AMBROSE: It was a process that was five, six years in the making, you know, didn't happen overnight. And the four pillars of our organization, it's research, education, citizen science and policy change. So once we did that citizen science research, it's like, okay, what's next, like, people need to know. And that's where the education came in. And the focal point of the education were youth, young people in the Bahamas and using them as catalysts to then take this message home to their families and spread the message also within their community. So on December of 2017, I hosted a youth activism workshop, and we brought in a local lawyer, and she taught our students all about legislation, and how to write laws in the Bahamas, I brought in a social scientist, and she taught them all about surveys, how do you measure attitudes and perceptions. Is a plastic ban something locals actually want? We did case studies where we looked at different countries, and what they did to ban plastics in their, in their land or in their nation. And with the help of the lawyer, we wrote a bill of what a single use plastic bag ban would look like for the Bahamas. And we took that to the Minister of Environment, he accepted our meeting. So we flew to the capital of Nassau. So when we went there, initially, I was like, "Okay, kids, we have to wear blazers, we have to be professional, we gotta, you know, speak in our best professional tones." And they're like, "Miss Kristal, that's boring!" So we went in there beating on the desk singing, "We are the change, we have the solution, we can fix this plastic pollution!" And we gave him three deliverables that we wanted by the end of the quarter. And we went there in January of 2018. And we wanted him to pass our bill through the House of Assembly. By the end of March, we wanted a national campaign, an awareness campaign, we wanted the Bahamas to sign the United Nations clean seas initiative. And he agreed, and the Minister of Environment mentioned that, you know, even though they were kind of working on this, slowly, but surely, seeing the young kids in front of him petitioning for their future, it really put the fire under him. And on Earth Day of 2018, he held a national press conference, announcing that the Bahamas was banning single use plastics. And the rest is history.

BASCOMB: So what's next for you? I understand that you're now in Sweden, studying for a PhD? What are your future plans?

AMBROSE: My future plans? I'm getting back to the research, you know, and what brought me to this is because of my my background, my connection to the ocean, that I know, yes, we got the victory, we got the plastic ban in place. But every time I go to beach, the plastic is still there streams of plastic are still washing onto shores, not only in the Bahamas, but throughout the entire Caribbean region. What happens to that plastic? You know? So that's something that I'm looking at. How can we create better management strategies to address marine litter concentrations in the Bahamas? How can we revision that? Can it be a valued item, you know, which is kind of weird, because when they made plastic, it was never made with any value in the first place. So now all of us in the plastic realm, we're putting this artificial value on plastic, on beach plastic especially. So it's a long way, a long way from true true solutions that need to come from the industry level. But in the interim, I want to know how can I now use this as an empowerment tool, potentially to boost local awareness and local economies?

Kristal with Ocean Ambassadors, student eco-activists from the Bahamas Plastic Movement. (Photo: Bahamas Plastic Movement)

BASCOMB: Kristal Ambrose, also known as Kristal Ocean, is this year's Goldman Prize winner for the islands and island nations. Kristal, congratulations and thank you so much for joining us today.

AMBROSE: Thank you. Thank you so much for having me. And let me share this platform.

Related links:

- Read more about Kristal Ambrose, 2020 Goldman Prize Recipient for Islands and Island Nations

- Check out our interview with Chibeze Ezekiel, 2020 Goldman Prize Recipient for Africa

- Find our interview with Lucie Pinson, 2020 Goldman Prize Recipient for Europe

[MUSIC: Marley’s Ghost, “Run, Come See Jerusalem” on Travelin’ Shoes, by Blake Alphonso Higgs (Blind Blake), Sage Arts]

Beyond the Headlines

Researchers observed browning among Salix Polaris dwarf shrubs like this one. (Photo: Henna K., Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hi there, Peter. How you doing?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. Here in Georgia, we're recovering from the bonus two extra months of slimy mean, ugly attack ads coming from both parties, and both sides for two Senate seats. But to answer your question shorter, I'm fine.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Well, you know, we got a democracy. What do you have for a story for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, a story about how scientists are using tree rings in a part of the world that have no trees. Aren't they clever, those scientists.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Okay. So what's the trick?

DYKSTRA: It's a new study of growth rings in Arctic shrubs that appeared recently, in the proceedings of the National Academies of Science revealing a trend that's surprising in the Arctic. We're looking at a lot of greening vegetation everywhere because of the warming temperatures, but little tiny tree rings that also exist in twigs and branches in shrubs show that shrubs in the Arctic are experiencing browning, because summer conditions in the tundra have grown too hot and too dry.

CURWOOD: Oh boy, if the Arctic gets browner, that means that more heat will be absorbed from the sun, and it'll, it'll warm even faster.

DYKSTRA: And the Arctic already has plenty of troubles as it is.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter, what's another story you have for us today beyond the headlines?

Stormwater systems in Norfolk, VA are increasingly overburdened as sea level rise causes flooding. (Photo: Aileen Devlin, Virginia Sea Grant, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: This one comes from the Hampton Roads area of City of Norfolk, Virginia, particularly, and down there at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, rising tides have not only threatened residents during storms, but they've kept the region's storm water systems at 50% capacity, even when it hasn't rained. Even when there hasn't been a high tide. And the result has been very, very little room in that storm water system to do what it is intended to do. And hold out substances for treatment, returning cleaner water to the Chesapeake, and to Hampton Roads, and the Atlantic Ocean.

CURWOOD: Boy, that's not gonna get better for a place that is what, really important to the US Navy? There's a big base there, what other things happen in Norfolk?

DYKSTRA: It's a naval base, it's a major US seaport, and it's a pretty big metro area, much of which is already very wary of what storms can do to the city, coal docks, the naval docks, and everything else that by nature have to be at sea level, even if the sea level doesn't want to stay where it is now.

CURWOOD: Let's have some fun with history today, I hope. Fun story?

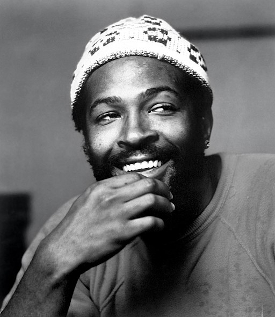

DYKSTRA: It's a fun story in the sense that it involves a really great song. The message from the song, not so much fun. But it's been 50 years since the late Marvin Gaye recorded Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology). Marvin Gaye was already an R&B giant, a Motown legend, and he put together an introspective moody string of songs written in 1970, after his partner Tammy Terell died of a brain tumor. Marvin Gaye and Tammy Terell were absolute hitsville in the late 60s. Marvin took a break after Tammy's death, but this song Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology) decries mercury in fish, pollution in freshwater, in saltwater, in the air, radiation and more.

Marvin Gaye in 1973, 2 years after the release of “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” (Photo: Jim Britt, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: Now, I don't think this was the brand of Motown Records back in the 70s to be doing ecology, huh?

DYKSTRA: No, the closest thing they got to pollution songs were the ones that came from Smokey Robinson, get it? Had to get that one in there. But Berry Gordy, the Motown Records empresario, is said to have absolutely hated it. Berry Gordy denies that, but when it was released as a single in the summer of 1971, Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology) made it to number one on the R&B charts, and number two on the pop charts.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Real soon it'll be. And since this is our first one in the new year, happy new year. Hope it's better for everybody.

CURWOOD: I have to agree with that. And there's more in these stories on the Living on Earth website. LOE.org.

Related links:

- Yale e360 | “Study of Growth Rings in Tundra Shrubs Reveals Spread of Arctic `Browning’”

- Read the Arctic shrub browning study

- The Virginian-Pilot | “In Norfolk, sea level rise reduces some stormwater system capacity by 50%, data shows”

[MUSIC: Marvin Gaye, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” on What’s Going On, Universal Motown Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – We’ll take a look back at the life and travels of the late environmental writer Barry Lopez. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Frank London’s Klezmer Brass Allstars, “Another Glass Of Wine To Give Succor To My Ailing Existence” on Carnival Conspiracy, traditional/arr.Frank London, Piranha Music]

Remembering Barry Lopez

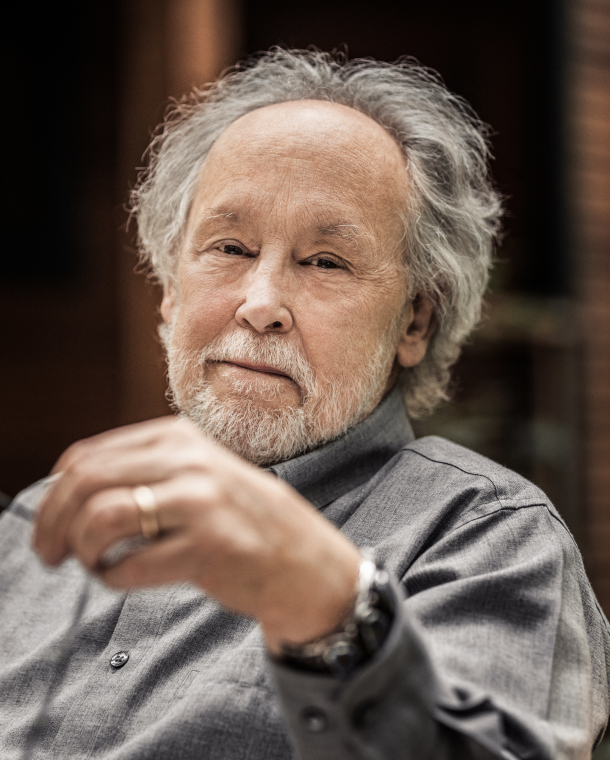

Barry Lopez, essayist and author of Horizon and sixteen other books, passed away on December 25, 2020. (Photo: John Clark)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Writer Barry Lopez was among those we lost in 2020. He passed away on Christmas Day, after a lengthy battle with cancer. A prolific environmental writer with an urgent message of repairing the rift between humans and nature, he was celebrated for works including Arctic Dreams, for which he won the National Book Award, and Of Wolves and Men. In a tribute in Orion Magazine, author Margaret Atwood wrote, “Barry was a prophet in the wilderness. A lonely speaker then—he must often have wondered whether anyone was truly listening—he is an essential speaker now.” In 2019, Barry Lopez published his final book, Horizon, which was 30 years in the making. It’s an expansive reflection on his travels all over the world, with a focus on the current need for humanity to navigate through these treacherous times. Barry Lopez joined me when the book came out for a conversation well worth sharing with you again now. We started by asking him to describe his inspiration for writing Horizon.

LOPEZ: I have made a life out of going away from my home and sojourning in other places, Antarctica or Afghanistan, and on and on. And while I was doing that, and writing articles about those places, I was asking myself the question, why are you doing this? Are you just running away? Or have you actually accomplished something in all these years of travel? So I think that was the trigger for the book. What had I done as a writer? That incubated inside of me; when I signed the contract in 1989, everybody at Knopf basically gave me their blessing, and they said, "when you are ready, bring this book to us. Nobody's going to ask you about, 'what'd you do with that advance?'." [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

LOPEZ: So between signing the contract about 30 years ago, and writing the book, I wrote five or six other books and wrote a lot for magazines. But I had to get myself educated, I had to mature as a human being. And once I felt, roughly in my late 60s, that I could understand what the book was supposed to be about, then I started writing it. But it incubated, Steve, for a very long time.

CURWOOD: Of course, your book is an elegant song of praise to the interactions between people and place —

LOPEZ: Yes.

CURWOOD: — and you dwell on your own relationship with a recently clear-cut patch of forest in Cape Foulweather, Oregon –

LOPEZ: Right.

Horizon is a work more than 30 years in the making. (Image: courtesy of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.)

CURWOOD: So, so tell me why you started your practice of visiting this clearcut, and why it became meaningful to you.

LOPEZ: I had for most of my adult life been intrigued with James Cook, and what he was up to, what he was about. And so I would read biographies and make notes and was going in no particular direction with that impulse. But I did know that, on his third voyage, he sighted North America and his landfall was at Cape Foulweather; they got there in a horrendous storm, and so he named the cape for the weather. And I thought, well I'll, I'll learn something, if I go over there and just sit quietly. So I went on these back roads, logging roads, and got some elevation, and camped in a clearcut where I could see, straight out in front of me, the Pacific. And I guess I went there 10 or 12 times and would camp there for a while. I didn't have an agenda. But I had tremendous curiosity about what this anonymous, and anomalous, place was. You know, I made a catalog of the plants and the birds, and was there in all kinds of weather. And to open the book, to open Horizon, I chose to go when a really big storm was moving in. I knew this storm was coming out of the Gulf of Alaska, and I thought, I'm going to go out to Cape Foulweather and, and weather the storm out there, just to get a little bit of a feeling of those few days when he was inside of Cape Foulweather. It was also a way for me to present a man named Ranald McDonald, who was born at the mouth of the Columbia River, he had a Chinook mother and a Scots father. And he didn't get the breaks in life that James Cook did, because he was mixed race. He was told in a very direct way that a person of mixed race like him had no business trying to approach or date a white woman. And he became the character for me that stood for modern times. We live in a mixed race culture, there's a mix of ideas, and the character of James Cook, although laudable, wasn't the full story. The world is full of characters like Ranald McDonald, who are heroic, but unheralded.

Barry Lopez opens Horizon with a scene at Cape Foulweather, Oregon, where he muses on the legacy of Captain James Cook and another heroic, but unheard of, navigator named Ranald MacDonald. (Photo: Kirt Edblom, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: You know, I view this part of your book as a fascinating take on, excuse the phrase, the 'great white hunter' phenomenon.

LOPEZ: Yes.

CURWOOD: And a commentary about, so who gets to make all these decisions about exploration? Who tells the story when you get there? And how do you, how do you get credit and support for doing something unusual like this, if, if, in fact, you are the guy that actually finds the game for the 'great white hunter'.

LOPEZ: I wanted, in this book, to set in motion the questions that you have just phrased. And throughout the book, I'm posing, I think, two questions that arise with Cook. And that is, all of us know hell is coming. You can call it global climate change, you can call it the disintegration of democratic forms of government, you can go anywhere and say, "this doesn't look good, this looks really bad". So the need to attack this issue, to me, is like one of the great voyages that we now have to choose to make: move into unknown territory, uncharted lands. So our model for that is this fellow Cook, and his ship. And my hope in the book is that people will say, we're in trouble. What is going to be the vessel on which we sail? And, maybe more importantly, who is going to be the navigator? Are the qualifications for a navigator today different than they were in the late 18th century? Oh my, yes. We have atomic weaponry, we have constant warfare, we have failing supplies of fresh water. We need a navigator the like of which we've never seen. So I think if you are doing your job as a writer, first of all has nothing to do with you; as the writer, you're the conduit, through which is coming something that maybe the writer doesn't understand. But it's an effort to put in front of people a vision of the world that allows them who have different expertises to say, "here's what we should do. This is how we take care of ourselves."

CURWOOD: You know, that book title, simply Horizon, there's no subtitle. 30 years ago, you picked it when you signed the contract.

LOPEZ: Right, I did.

CURWOOD: Why? Why did you choose that title?

LOPEZ: The question that you've asked is one I ask myself, why did I choose that word for the title of the book? I had to write the book before I understood why the book is called Horizon. The book early on also had a subtitle, which I decided to get rid of because it was pretentious, and was not earning its place on the cover. I think especially with a big book like this, the process of editing is, in large part, is getting rid of the scaffolding. You set up the scaffolding to create the edifice, and if you want it to be seen in a clean way, you've got to get rid of all of that scaffolding. So the subtitle was a bit of scaffolding. And I looked at it one day and thought, "oh, give me a break."

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

LOPEZ: So the, the title and the subtitle were once Horizon: The Autobiography of a Journey. And it is an autobiographical book, and it is about the narrator's trying to grow up, trying to be a real person. And early on in the book, you know, I did something that was completely foolish and humiliating for me to discover in myself, which is a failure to understand that the other people are different from you, and you don't know; they do. And when I did that, I felt, I have to write about this, and I have to expose my vulnerability. And I have to make common cause with every reader who, all of us have done things we regret doing. And then, then you grow up. And so the whole book is about arriving at a position of impassioned embrace of all human beings. People often say to me, "well, you go to these exotic places, what's the key?" As though there was, you know. But the answer to that is, when you are in a place that is not your own, among people who are not like you, the first impulse always has to be respect. Even if you don't understand, you have to show respect for what is technically called another epistemology, another way of knowing the world.

The Captain James Cook statue in Christchurch, New Zealand. (Photo: Roger Wong, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So to what extent would you say that Horizon tells the story of you discovering the Other?

LOPEZ: You're so good at this, Steve; it is that, I hadn't thought of that. But if you'd let me what I would say – yes, it is a story of the discovery of the Other. But I think it's a plea as well, to everyone to take the same journey, to realize the stakes are so high now that you must make common cause with all people. You could say, we need to rid ourselves of racism, and ethnic warfare, etc, etc. We aren't doing that, we're still living with that horror. But we have to discover a politics, for example, that takes place as though all those things have been accomplished. So you're saying to yourself all the time, "what would it be like, if we didn't have this racist horror drifting through American culture?" And then you have to make a politics that's founded on the fact that we were able to do that. Time is so short; you can sit down with people who make the models for global climate change, and what they all agree on since they started in the late 70s, is, we got some things right. Each time we do this, we get many things right. But the one thing we get wrong consistently, is how fast this is happening. So we have not too much time, and we need calm voices, common cause, compassion, empathy for all people who are in bad straits. And when we fall down, somebody helps us up, we have to be there when somebody else falls, and you help them up. If we can't make that giant leap, everything we pray for in our lives, in our different religions, is going to come to nothing.

CURWOOD: Your book is both searing in its indictment of the way we're conducting things, and our plight, and hopeful, so hopeful –

LOPEZ: Yes.

CURWOOD: — that somehow we are going to deal with these huge challenges that humanity is facing. Why?

LOPEZ: Whenever people say something nice about my work, or, or what I've done, I always point out that I had really good teachers. And I mean, I had great teachers in university, and then I went into cultural worlds different from my own, and there too, I had great teachers. They were not of my race, they were not of my religion. They weren't, they didn't speak my language. But these men and women helped me to understand what it means to be a grownup. And, you know, a grownup is somebody who no longer needs to be supervised, they can be left alone, to act on behalf of their people, without the fear that they're going to favor one group, or one age, or one gender over another. One of those people said to me one time, when I expressed doubt about myself and about the direction of the book, he said, "the only thing you can do wrong, is to destroy someone's sense of hope. For you, the sense of hope that they are carrying might be poorly thought out or untenable. But you cannot say that to somebody, you have to support them on their journey to arrive at a hopeful end." So I knew that I had to state in the book some of the terrible episodes that we all have experience with, or at least know about, like the slave trade. And we have to reckon with that. But I knew the book had to end with an elevation of the reader's spirit that was believable. Many of us have become cynical, because of the atmosphere around, if you will, the current occupant of the White House, we've become very cynical about what can be done. And we can't go into that place, we have to maintain a vision that, you know, is on the horizon, of a different way of doing things that is less harmful, less cruel. It's a request, I suppose, for a larger view of things than the horrible moment of the present. And I count on readers to come alive with this book and say, I now understand better what it is I really want for myself or my family or my children.

CURWOOD: And you're an optimist about that.

LOPEZ: There's no good thing that can be said about despair and pessimism. The whole thing is on the line right now, the entire meaning of the evolution of Homo sapiens. We either show that our power of invention is tremendous, or we show that the development of imagination in the hominin line was maladaptive.

CURWOOD: Barry Lopez is the author of the National Book Award-winning Arctic Dreams and his 2019 book is called Horizon Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

LOPEZ: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Barry Lopez recently died, but he leaves behind a lasting legacy of sharing his love for the wonders of this planet we all call home.

Related links:

- Horizon by Barry Lopez

- Barry Lopez’s website

[MUSIC: Jacqueline Schwab, “La Maestra” on True Blue Waltz, by Keith Murphy, Midsummer Recordings]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aaron Mok, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Casey Troost, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth