April 30, 2021

Air Date: April 30, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Methane and Swift Climate Action

View the page for this story

METHANE AND SWIFT CLIMATE ACTION: A United Nations report is expected to point to reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, livestock and other sources as key for acting quickly to limit climate change. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas that doesn’t last long in the atmosphere, so reducing it can have almost immediate benefits for the climate. Michael Oppenheimer, Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs at Princeton University, joined Host Jenni Doering to discuss the role methane plays in planetary and human health. (07:17)

Senate Votes for Strong Methane Rules

View the page for this story

SENATE VOTES FOR STRONG METHANE RULES: The Trump administration placed severe limits on the EPA’s ability to regulate methane, a strong greenhouse gas. Now lawmakers in the U.S. Senate have voted 52-42 to disavow the Trump methane policy and return to stronger Obama-era regulatory standards, and the House is due to take up the measure soon. Senator Martin Heinrich (D-NM), a lead co-sponsor of the bill, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the need for swift legislative action to limit leaking methane. (07:07)

Biden, LOE and Dykstra

View the page for this story

BIDEN, LOE AND DYKSTRA: Environmental Health News weekend editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood for a quick recap of President Biden's climate and environment mentions in his first address to the joint houses of Congress. Then, the two discuss Living on Earth's thirty-year anniversary and some of their favorite memories from the show's tenure. (06:38)

Getting Bushmeat Off the Table

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

GETTING BUSHMEAT OFF THE TABLE: The forests of the Congo Basin are among the most biodiverse in the world. But as the region’s cities grow, the demand for forest bushmeat is threatening food sources for indigenous communities and endangered pangolins and monkeys. The government of the Democratic Republic of Congo launched a campaign encouraging people in cities like Kinshasa to cook traditional bushmeat recipes with protein alternatives that don't harm the region's biodiversity. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran joined Host Jenni Doering to talk about the bushmeat trade and this campaign. (06:54)

“Planet” by Poet Catherine Pierce

View the page for this story

“PLANET” BY POET CATHERINE PIERCE: To close out Poetry Month and Earth Month, poet Catherine Pierce shares her poem “Planet”. She’s the author of Danger Days and other books of poems that grapple with climate disaster. (02:12)

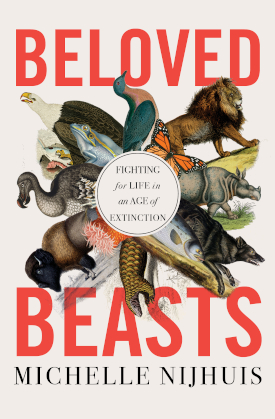

Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in An Age of Extinction

View the page for this story

BELOVED BEASTS: FIGHTING FOR LIFE IN AN AGE OF EXTINCTION: Animals like the American Bison, bald eagle, and giant panda are just a few of the charismatic species that have come dangerously close to extinction. But thanks to some visionaries, species like these have been saved from that fate. In her new book Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction, science writer Michelle Nijhuis shares the stories of some conservation heroes. She joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about Rosalie Edge and Aldo Leopold and to debunk the myth of the tragedy of the commons. (17:08)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210430 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Martin Heinrich, Michelle Nijhuis, Michael Oppenheimer, Catherine Pierce

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

With a bipartisan vote the US Senate has moved to restore rules crippled by the Trump administration that restrict methane emissions.

HEINRICH: This stuff is dangerous; in its uncombusted form, a very powerful driver of climate change, and it’s bad for public health. So we just can’t have it in these communities. This is something we know how to fix, we should fix it.

CURWOOD: Also, some histories of people who pioneered pushback against extinction.

NIJHUIS: What I hope people will realize is just because we can’t save everything, doesn’t mean that what we’re doing doesn’t matter. It’s still possible to make a huge difference, it’s still possible to save species that are going to be valuable not only for our own survival but for the survival of the future generations.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Methane and Swift Climate Action

Although methane has a much shorter lifespan than carbon dioxide it is a major component of the greenhouse effect. Smog could be reduced globally by cutting methane emissions. (Photo: Josh, Flickr, CC BY ND-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Talk of the climate emergency usually points to big bad CO2. But the smaller molecule CH4, what we call methane, is more than 80 times stronger than carbon dioxide over the short term. And although there’s a lot less of it in the air compared to CO2, methane is responsible for as much as a quarter of the climate impact of humans. So in a forthcoming report, scientists with the UN Environment Program and the Climate & Clean Air Coalition are expected to say that targeting methane can help jumpstart climate action. They say “cutting methane is the strongest lever we have to slow climate change over the next 25 years.” Joining us now is Michael Oppenheimer, he’s Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs at Princeton University. Welcome to Living on Earth!

OPPENHEIMER: Thanks for having me today.

DOERING: So professor, why is cutting methane the strongest lever, we have to slow climate change over the near term?

OPPENHEIMER: Methane has a much shorter lifetime in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. That means each molecule you put up there only lasts something on the order of a decade, instead of hundred, or even hundreds of years. So that if you want to effect the amount of greenhouse effect in the short term, and reduce the rate of increase of human made warming, one of the easier things you can do is reduce the emissions of methane into the atmosphere because the amount of methane in the atmosphere responds immediately to emissions reductions, essentially, immediately. While the amount of carbon dioxide has a lot of inertia and it hardly responds to any immediate emissions reduction at all, you have to reduce emissions over decades to see an answer or a response to the warming of the earth.

DOERING: So this report, and I think some other recent research finds that methane is actually playing a more critical role in climate disruption than we had accounted for. What do we know so far?

OPPENHEIMER: Well, what happened was that the amount of methane which had grown steadily since pre industrial times, as humans, mined more coal, coal mines release methane when you open them, as humans drilled for natural gas and oil, both of which leak methane into the atmosphere, because natural gas is largely methane. And because when you drill oil, there's a lot of pockets of methane down there with the oil. And the industry used to just flare the stuff wasted, even though it has a high commercial value. And then there were other sources like for instance, landfills. And cow belching it's one of the major sources. And frankly, if we all went over the vegetarian diet, we'd be having a positive effect on greenhouse gases that is reducing them, because we'd largely eliminate this particular source of warming. So there's a whole sequence of these sources, a whole series of them. And because of that methane emissions grew in the amount of methane in the atmosphere grew for many decades. And one of the major new findings is that the oil and gas industry is releasing a lot more methane than we used to think, not simply through flaring, or opening mines, coal mines or drilling oil. But because the systems that drill for natural gas, the systems that distribute natural gas transmitted across the country, and then distributed, for instance, to factories and homes have leaks all over the place and the leak rates are much, much higher than we previously expected. And that has really added to the urgency of the problem. It used to be thought that because methane has less carbon in it per unit of energy produced by burning by combustion then does coal that would be a net benefit to make a transition from coal to natural gas. But with these leaks happening all over the place, in fact, it may be no benefit at all.

DOERING: What kinds of health benefits could we see from reducing human caused methane levels?

The image above shows an oil plant in Texas flaring-burning flammable gases like methane that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere. Instead of flaring, methane could be recuperated and used as an energy source. (Photo: Jonathan Curter, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

OPPENHEIMER: There are several ways it would help human health. Interestingly, at a global scale methane is one of the important hydrocarbon precursors of smog. So you could reduce smog levels globally, by cutting methane emissions. And smog, particularly in densely populated industrial areas, it causes very high death rates and even in this country, 1000s of people every year have their lives cut short, because they're subject to too much air pollution. A second way, which relates more directly to warming is that the biggest cause of climate related mortality in this country is heat related death, and he related death is going to go up to the number of very high days it's increasing quickly. And a way to make the quickest possible dent in that is to reduce the heat trapping effect of methane. Some people say, well, people have air conditioning. Well, fine for rich people but there are a lot of people in this country that aren't wealthy and that aren't middle class, and they can't afford air conditioning. It's one of these climate justice or environmental justice issues, where people don't think about how most of humanity lives.

DOERING: You know, the climate emergency and, you know, what we're what we're facing really feels just hugely daunting. And you know, we have less than 10 years at this point to half our emissions in order to be on track to the Paris goals. How hopeful Are you that human beings can collaborate on the global scale that is needed in order to really deal with this climate emergency that we're facing?

The cattle industry produces 37 % of all methane emissions from human activity. Although methane is shorter lived than carbon dioxide when it is first emitted it is about 80 times more potent in warming the planet. (Photo: Kyle Spradly, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

OPPENHEIMER: Well, first of all, I don't want anybody to lose hope. I teach that's my job. I teach young people. And I particularly in the last few years am astounded by the way that they have sort of come together to figure out what they can do to solve the problem. So they’re not distraught. They're not immobilized, they're angry. They're angry that we dumped this stuff on and basically with this problem. And so as long as they don't give up hope you shouldn't give up hope because that means there's a whole generation of people out there trying to solve the problem. So there are things that can be done. First of all, there's an energy revolution going on. This has happened partly because the government invested for decades in research and development of solar energy and wind energy. But it also happened because then after those technologies became available the market forces kicked in. So there's a picture that fits together that involves government, it involves the private sector, and involves individuals in their purchasing decisions. And the sooner we can get those three things synchronized with tighter regulations, with industry knowing that this is the future and they have to act fast, and with people changing some of their buying and living habits, we’ll be there.

DOERING: Michael Oppenheimer is a professor of Geosciences and International Affairs at Princeton University. Michael, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

OPPENHEIMER: My pleasure.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Halting the Vast Release of Methane is Critical for Climate, U.N. Says”

- Learn more about Professor Oppenheimer

[MUSIC: Women Of the World, “Latibonit” on Makana, traditional Haitian folk song/arr. Deborah Pierre with Annette Philip, Sashank Novaladi, self-published]

Senate Votes for Strong Methane Rules

A natural gas flare in Balmorhea,Texas. (Photo: Ken Lund via Flickr, CC BY 3.0)

CURWOOD: In a bipartisan vote, the U.S. Senate approved a bill that would undo the Trump administration’s major weakening of methane emission rules. And it is expected to pass the House. The measure takes advantage of the Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to void regulations made at the last minute by an outgoing administration. Democratic Senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico co-sponsored the bill and joins me now from Washington. Welcome to Living on Earth, Senator!

HEINRICH: It's my pleasure.

CURWOOD: Now the Trump administration notoriously weakened a number of environmental regulations. Talk to me about how it weakened the methane rule. And what did that mean for the nation, and for that matter, our planet for these past four years?

HEINRICH: It really meant lost time in terms of addressing the challenges that we had, and lost international leadership. We should be leading the world's efforts to control methane. It's one of the most straightforward things we can do. And even most of the international majors in oil and gas, understand that by capturing this methane, they're actually selling more product than if they let it become fugitive methane and just leak out of the infrastructure. So this is something that we should have done, obviously, five, six years ago, and we're making up for lost time.

CURWOOD: You're a co-sponsor of the Senate methane bill. Senator Heinrich, why was it so essential for the Senate to act now under the Congressional Review Act, rather than draft its own legislation going forward?

Democratic Senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico is the lead Senate sponsor of the bill to reinstate Obama-era methane regulations. This bill passed 52-42 this Wednesday. (Photo: United States Senate)

HEINRICH: Well, the Congressional Review Act is sort of a ticking time bomb when a new administration comes in. So if you wait too long, you lose the ability to revisit those rules. This puts us in a position of leadership again, right out of the gate. And it also creates a situation where the EPA can look at further rules down the road, and sort of sets a clean slate so that they can look at other sources and what rules might be appropriate for those. So rather than spend a lot of time writing new legislation for something that we already know how to fix, that there's wide support for, this gets us as good a starting point as we could hope for in a new administration.

CURWOOD: So how do your constituents feel about having the methane rule essentially reinstated? I understand there was a flyover study by the New Mexico Environment Department and the EPA that said that there was pretty heavy methane leak rate from oil and gas industry in your state, perhaps 5%.

HEINRICH: We've seen an increasingly high amounts of methane leakage in the southeast part of the state. And one of the things I would argue is, every cubic foot of leaked methane is one that doesn't go to market and benefit the state. This is a positive for the state's budget. But it's also just the right thing to do. This stuff is dangerous, in its uncombusted form a very powerful driver of climate change. And it's bad for public health. So we just can't have it in these communities. This is something we know how to fix, we should fix it.

CURWOOD: How does the oil and gas industry feel about having the methane rule reinstated? What's the economic balance for them?

HEINRICH: I would say that the math is fairly clear that they actually do better by controlling the methane. And that is why you will see many of the International majors have endorsed this effort: Shell, Equinor, BP. And in the case of those portions of industry that have not been willing to do that, I think it has been more a case of dogma and culture that it has been of dollars and cents.

CURWOOD: Senator Heinrich, this vote to undo the weaker methane regulations that were put in place under the Trump administration, was in fact bipartisan. What kind of precedent does this set in terms of bipartisan cooperation around fossil fuels and things that affect the climate?

Fossil fuel use and production is a major contributor to global methane emissions. (Photo: Eric Kounce via Wikipedia, CC)

HEINRICH: My experience is that success breeds more success and failure breeds more failure. And the good news is, we now have twice in a row, in just a matter of months, fixed some things that were obvious and must fixes to begin to address climate change. We dealt with hydrofluorocarbons, which are those refrigerants that are super powerful climate drivers. And we did that in a bipartisan way. Now we've dealt with methane. So my hope is that this builds some momentum for continued bipartisan progress on at least some of the things that we have to do if we're gonna stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about another climate related issue that you are pushing legislation about, I'm talking about electrification. What are you calling for exactly? And how does this connect with the long term reality of transitioning our society away from natural gas and the other fossil fuels?

HEINRICH: Well, as we look at investing in infrastructure in our country, I think one of the things that's important is to create incentives to really reduce the amount of combustion writ-large that we do in our homes and businesses. Indoor air quality is a huge public health problem. And part of the reason why we have such challenges with indoor air quality is because we continue to burn natural gas inside our homes, inside our businesses. So, having incentives in place to switch those appliances out to completely clean non-emission, electrified appliances like heat pumps, like heat pump water heaters, like induction stoves, is a big part of how we get at some of the more challenging portions of our emissions footprint. We also need to have a grander vision of how we clean up our entire energy infrastructure in this country and on this planet. And I think you're gonna see a pivot of companies that are involved in the oil and gas sector today, moving towards technologies like hydrogen. And we're going to change out many of the things that we do today, the way we do them with technologies that are much cleaner and much better for our public health.

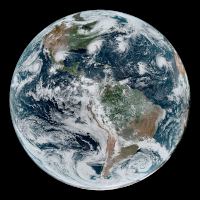

Global sources and sinks of methane for the decade 2008-2017. (Photo: The Global Carbon Project, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: How quickly does the kind of transformation that you're talking about here need to happen in order to really make progress in dealing with the climate crisis do you think?

HEINRICH: I think to hit our goals, what we need to do is start now. And we need to apply it to all of our major appliances as they get to the end of their service life. So it's not critical that you take your existing gas water heater and change it out to a heat pump water heater today. But it is critical that we create the incentives that when you reach that end of service life, that you replace that appliance with something that is cleaner and healthier. And if we do that, we have a real chance at mitigating the worst impacts of climate change.

CURWOOD: Democratic Senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico, thank you for being with me today.

HEINRICH: My pleasure.

Related links:

- The Hill | “Senate Votes to Nix Trump Rule Limiting Methane Regulation”

- The New York Times | “Senate Reinstates Obama-Era Controls on Climate-Warming Methane”

- More on methane from the Climate and Clean Air Coalition

- KRWG | “Heinrich Praises American Jobs Plan”

[MUSIC: Guy’s All-Star Shoe Band, “When the Red, Red Robin Comes Bob, Bob, Bobbin’ Along” on Shake It, Break It and Hang It on the Wall, by Harry Woods, High Bridge]

DOERING: Coming up – protecting the Central African rainforest by pushing bushmeat off the menu of urban weddings and funerals. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Charles Mingus, “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting” on Something To Believe In, by Charles Mingus, Hear Music/Warner Special Products]

Biden, LOE and Dykstra

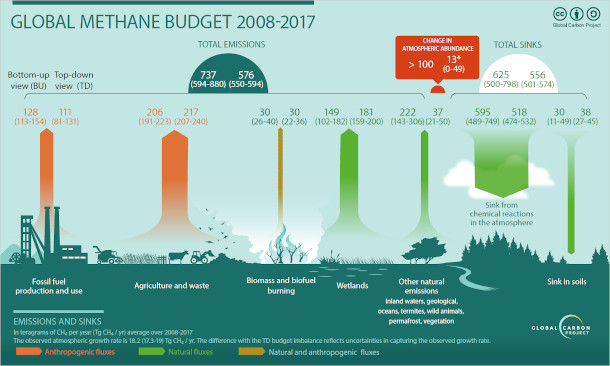

On April 28th, 2021, President Joe Biden gave his first public address before a joint session of the United States Congress – called the “State of the Union” address in years other than a president’s first year in office. (Photo: Screenshot from the White House video of President Biden’s Address)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: And with me now on the line from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra. He's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hi, there, Peter, let's talk about President Biden's speech to the nation.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, this week he gave his not-the-State of the Union address. One of the traditions is that a rookie president just refers to it as an address to a joint session of Congress. There was a restricted audience because of COVID. And of course, there were two women on the dais behind him. They're all breaks from the scenario of the normal speech. But there was also a lot of mention, much more than normal, about climate and the environment.

CURWOOD: Indeed, in fact, one thing that really caught my ear and eye was when he talked about lead pipes and lead poisoning, let's hear that bit of tape.

BIDEN: American jobs plan creates jobs replacing 100% of the nation's lead pipes in service lines, so every American can drink clean water.

CURWOOD: So Peter, lead is a huge problem for the brains of growing children, even small amounts of exposure to lead reduce IQ and can cause difficulties in both physical and mental functioning. And those places that have lead pipes for supply lines tend to be in less affluent neighborhoods and places more occupied by people of color.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, it's a pretty clear environmental justice story, one that's rooted in literally thousands of American communities. Biden, as he did with climate change, and other issues, couched it all in the framework of an infrastructure opportunity to create, as he said with climate: jobs, jobs, jobs.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and there are a lot of jobs there, because I mean, we know about the disaster in Flint, Michigan, when the water supply was changed, and started leeching the lead out of the pipes. But folks with FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, tell me that there are more than 4000 cities and towns and jurisdictions that have significant amounts of lead pipes in the supply lines to homes.

DYKSTRA: And Biden made what comes pretty close to a promise to get rid of all of those service lines going into homes. That's a tall order, he may have very little time to do that, for the political winds are blowing against him to get his agenda served. That's also true with climate, and so many other specific issues that went unmentioned, like the growing plastics pollution problem. No president has ever so much as mentioned that in any kind of a speech to Congress.

CURWOOD: That's right. And he knows from his experience, that he has a very short window to get big things like this done. There'll be the midterm elections very soon. And yet, what he's talking about are things which will largely pay well after, even if he were to be president for eight years. For example, cleaning up the waters or keeping the climate from going off the rails. These are all things that we'll know about well after he leaves office.

DYKSTRA: That's right. And hopefully we can recognize them then. But it's easier said than done, because past presidents have talked a lot about fixing environmental issues, and it hasn't necessarily come to pass.

CURWOOD: Okay, give me the rundown, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, we can go back to the 2000s when President George W. Bush confessed that we are addicted to oil. Those were the exact words spoken into the camera to all Americans, by a man from a family that made its fortune in the oil industry. Go back to the 1990s, Bill Clinton promised to deal with Superfund, that still hasn't happened. Go back to the 1980s and Ronald Reagan, of all people, bemoaned partisanship on environmental issues and said there's no place for it.

CURWOOD: I think a lot of people are hoping that Mr. Biden is able to keep these promises that he's making, which if they happen, Peter, how fair is it to say that this will be transformative for the United States?

DYKSTRA: It would be absolutely transformative. The question is, will it happen? Steve, you've been here for 30 years measuring such things and whether they happen and how badly they're needed. And that's something else we should talk about.

CURWOOD: Oh, okay, you're talking about the show. 30 years, huh?

Living on Earth Founder, Host and Executive Producer Steve Curwood in the recording studio. (Photo: Courtesy of Steve Curwood)

DYKSTRA: Living on Earth made its debut on public radio stations in April of 1991. A young Steve Curwood hosted the show, raised money for the show, wrote a lot of the pieces, produced the pieces, and has been the voice of LOE for 30 years ever since.

CURWOOD: And I had plenty of help. People like Deb Stavro and George Homsy, Peter Thomson, Loretta Hobbs at CPB, so many others that really encouraged this project. And, of course, along the way, I got to work with you.

DYKSTRA: Oh, gosh.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Back in the day, we were working together on the Society for Environmental Journalists, a journalism organization that was put together in no small measure in response to industry saying, oh, they're just a bunch of environmental advocates. And you've been instrumental of that, Peter, all those years you spent at CNN. And of course, now you've been doing this with Environmental Health News and us.

DYKSTRA: Oh, you know, I've been a part of the show for the last five years. I'm really proud of that. But you have things like the BirdNote segment, great use of audio. We have beautiful essays from your Explorer-in-Residence. And that makes my segment in the show my third favorite part of the show, but I have one question for you. Do you have a favorite moment or moments in your 30 years with the show?

Host and Executive Producer Steve Curwood founded and piloted the Living on Earth program in April 1990. (Photo: Living on Earth)

CURWOOD: Wow. I mean, I'm not sure that it's fair to pick the various children because so many interesting works have been done by people that I've worked with here. But I will say this, that on a personal level, my favorite environmental advocate interview was with Pete Seeger, the folk singer who got so involved with the efforts to clean up the Hudson River. And in terms of moments to report on and witness, I think 1997 in Kyoto and then in 2015, in Paris, when the international climate agreements came together. I really felt that our journalism helped to make a difference, especially since for many, many, many years, we were one of the very few voices that broadcast on this nationally about what was going on at the UN. And I'm glad to have been part of the effort to tell the story.

DYKSTRA: And as they said back in the movie, Casablanca: Steve, we'll always have Paris and Kyoto.

CURWOOD: Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Well, thanks, Steve. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read the full text of President Biden’s address to congress here

- See more from Peter Dykstra here

[MUSIC: Benny Carter, “Evening Star” on SONGBOOK Volume II, by Benny Carter, MusicMasters Jazz]

Getting Bushmeat Off the Table

Dried fish at a weekly market in Yangambi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Wildmeat, or bushmeat, is also commonly sold in markets. (Photo: Axel Fassio, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: The Congo Rainforest in Central Africa is the second largest rainforest on the planet, after the Amazon, and it’s a treasure trove of biodiversity. Picture chimpanzees and bonobos swinging from branches; okapis and elephants making trails through the forest; and at least 10,000 species of birds singing in the canopy. But in the wake of a colonized past, the war-torn region has suffered political turmoil and years of conflict. Meanwhile the forest is being hollowed out by the rising demand for bushmeat in big cities like Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Brazzaville, across the border in the Republic of Congo. The wild meat trade can and does exist legally, but most of this meat in the cities is illegally sourced from poaching. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran has been looking into the problem, and she’s here now -- Hey Paloma!

BELTRAN: Hi Jenni!

DOERING: So why is bushmeat so popular in the DRC and Republic of Congo?

BELTRAN: So wild meat is part of Central African culture. I talked to Robert Mwinyihali he’s the bushmeat coordinator for the Wildlife Conservation Society and he’s based in Kinshasa.

MWINYIHALI: Wild meat is a social norm. You can see that when people are organizing marriage ceremony or funeral any other ceremony it is built around wild meat, right. When you visit somebody in the village, the only food they will present to you is bushmeat. So, full wild meat was a traditional staple in every forest region in Central Africa.

BELTRAN: And it’s being consumed more and more as cities grow.

Kinshasa in the DRC is one of the biggest cities in Africa; its population has grown by three million in the last five years. Now there’s more than six-teen million people.

DOERING: Wow - I think New York City is like 9 million, that’s not even close!

So do they all eat bushmeat?

Pangolin in a tree. The animals, along with antelopes, monkeys, duikers and other wild animals have long been consumed as a part of traditional Congolese cuisine. Over-consumption of such animals is now threatening their future. (Photo: Louis Mornaud, Unsplash)

BELTRAN: Well it turns out that on average each person in the city of Kinshasa eats bushmeat about once a year at an important feast, and even that is putting huge pressures on wildlife. I talked to Robert’s colleague Michelle Wieland, the Africa Socio-economic director for the Wildlife Conservation Society.

WIELAND: Well, so we've already seen that wildlife species are disappearing from forests around cities. So if you go around Kinshasa, or even around towns like Kisangani, the forests are almost empty. Right, and we call it the empty forest syndrome. And so what happens is that you end up with communities, particularly indigenous hunter gatherers, who end up destitute because their whole culture and their whole food systems rely on wildlife.

DOERING: An empty forest… Paloma, that’s so sad, and I mean what are these forests without their animals?

BELTRAN: Yes exactly! Michelle also talked about how the health of forests depends on the existence of animals. It’s not just the animals that are being lost but the role they play.

WIELAND: So when you start to lose your big animals, which is what hunters go for first, so elephants, gorillas, buffalo, chimpanzees, what happens is that you lose your seed dispersers, right, because they eat the fruits that fall from the trees. And so if you don't have host animals to take those seeds, and move them around the forest, you end up with sick forests. And we all know that, these unhealthy forests can also lead to problems for all of humanity, because it increases that risk of zoonotic transfer, and just weak ecosystems.

DOERING: Right I mean we’re all dealing with the consequences of that kind of thing right now.

A forest near Yangambi, DRC. Over-hunting of wildlife has led to the “empty forest syndrome.” (Photo: Axel Fassio, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: Yes Jenni, and the Congo has experienced its fair share of zoonotic diseases like Ebola. And bushmeat is really hard to track and control. It’s often dried for preservation and by the time it reaches the city it’s hard to identify if the meat came from an endangered species. There have been several campaigns aimed at getting people in the cities to stop eating poached meat. But they’ve had little success. So the DRC government is trying something new.

VIDEO: Yoka Pimbo describing ingredients

DOERING: Oh, what are we cooking?!

[Audio of Chef Muvaru]

BELTRAN: That’s Maman Muvaru [Maman Muvaru cooking] She is a celebrated Congolese chef and she’s joined this campaign to show people how they can switch out wild meat in traditional recipes for alternatives. For example she's cooking up a stew which is traditionally made with a kind of bushmeat like pangolin or antelope but it tastes just as good with goat. Cooked down with spinach, onion, tomatoes, okra, and garlic, until it’s…

(“mmm. Yoka Pimbo!”)

BELTRAN: That means delicious in Lingala.

DOERING: Mmm, Paloma, Bon Appetit!

BELTRAN: Yeah I’m getting hungry! And what's cool about this campaign is that it’s focused on celebrating Congolese culture instead of suppressing it.

WIELAND: We really understand that meat is an important part of African cuisine. And we're targeting some of the wealthier people in the cities. Who can afford to try something new. We're inviting people to substitute it with local alternatives. Goats, caterpillars, smoked fish, fresh fish.

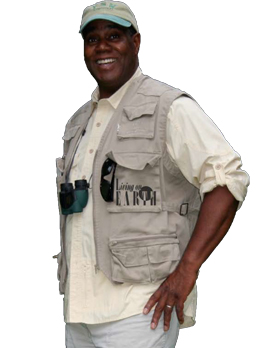

Robert Mwinyihali is the project director for urban bushmeat based in Kinshasa and Brazaville working for the Wildlife Conservation Society. (Photo: Courtesy of Robert Minyihali)

DOERING: Wait - did I hear that right, caterpillars?

BELTRAN: Yup! I’m not sure what they taste like but they're a good source of protein!

DOERING: Hey, I guess so! Hey so Paloma, how are people reacting to this?

BELTRAN: Well the campaign is huge. It’s all over the radio, tv, people are tweeting about it, and they have an instagram. And you know it just started in April so we don’t know what kind of impact it’s having yet. Or if it’s changing behaviour but Robert has worked for more than 20 years in conservation and he’s optimistic because this campaign is designed to cherish and elevate Congolese cuisine.

MWINYIHALI: We didn't want to go with the traditional message of conservation. We wanted this campaign to fit in local values, local values of the cities, the campaign to be more positive. The campaign to be something that individual consumers can do.

DOERING: Well, the illegal bushmeat trade is such a huge and daunting problem, but it sounds like they’re trying to break it down into bite size pieces!

BELTRAN: Yeah! You can’t protect wildlife and the indigenous communities who depend on it without considering the human part of the equation.

DOERING: Well thanks, Paloma, well, let’s see how well this campaign works!

BELTRAN: You got it, Jenni!

Related links:

- Culinary campaign website

- Video of Chef Maman Muvaru making a dish with goat meat instead of bushmeat

- The Sustainable Wildlife Management (SWM) Programme

- Our Voices from United Nations University | “Bushmeat Stories: Voices from the Congo Basin”

[MUSIC: Oumou Sangare, “Sukunyali” on Seya, by Oumou Sangare, World Circuit/Nonesuch]

“Planet” by Poet Catherine Pierce

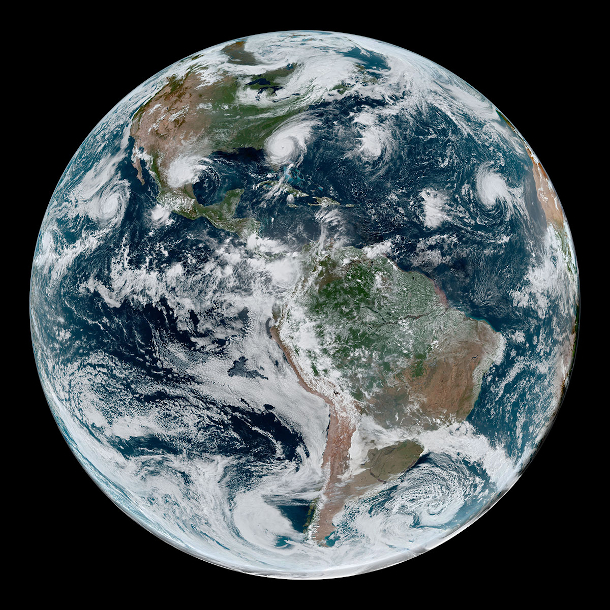

Poet Catherine Pierce confronts the climate emergency head-on in her work, and even finds beauty within it. (Image: NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens; NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service)

CURWOOD: Catherine Pierce is the author of Danger Days and other books. And, to close out Poetry Month, and Earth Month, here is her poem called Planet.

PIERCE: This morning this planet is covered by winds and blue.

This morning this planet is lit with dustless perfect light,

enough that I can see one million sharp leaves

from where I stand. I walk on this planet, its hard-packed

dirt and prickling grass, and I don’t fall off. I come down

light if I choose, heavy if I choose. I never float away.

Sometimes I want to be weightless on this planet, and so

I wade into a brown river or dive through a wave

and for a while feel nothing under my feet. Sometimes

I want to hear what it was like before the air and so I duck

under the water and listen to the muted hums. I’m ashamed

to say that most days I forget this planet. That most days

I think about dentist appointments and plagiarists

and the various ways I can try to protect my body from itself.

That last weekend I saw Jupiter through a giant telescope,

its storm stripes, four of its 67 moons, and was filled

with fierce longing, bitter that instead of Ganymede or Europa,

I had only one moon floating in my sky, the moon

called Moon, its face familiar and stale. But this morning

I stepped outside and the wind nearly knocked me down.

This morning I stepped outside and the blue nearly

crushed me. This morning this planet is so loud with itself—

its winds, its insects, its grackles and mourning doves—

that I can hardly hear my own lamentations. This planet.

All its grooved bark, all its sand of quartz and bones

and volcanic glass, all its creeping thistle lacing the yards

with spiny purple. I’m trying to come down light today.

I’m trying to see this place even as I’m walking through it.

Catherine Pierce is the author of four books of poems including Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World and is professor of English and co-director of the creative writing program at Mississippi State University. (Photo: Megan Bean / Mississippi State University)

CURWOOD: Writer and poet Catherine Pierce teaches at Mississippi State University.

Her poem “Planet” first appeared in the Southern Review.

Related link:

Catherine Pierce’s poetry and more

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Dulci Forte” on Pure Hammered Dulcimer, by Joshua Messick, self-published]

DOERING: Just ahead – some conservation heroes working to save our “beloved beasts.” Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Taj Mahal Meets the Culture Musical Club of Zanzibar, “Catfish Blues” on Blues Around the World, by Taj Mahal, Putumayo World Music]

Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in An Age of Extinction

As many as 30-60 million American Bison once roamed the plains. They were nearly hunted to extinction around the turn of the century but have recovered from the brink thanks to conservation efforts. (Photo: Road Travel America, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

American Bison… Bald Eagle… Giant Panda. These are just a few of the charismatic species that have come dangerously close to extinction. Once a species is gone it’s gone forever, and these days humans are usually to blame. But thanks to some visionaries, large herds of bison are back, bald eagle populations are soaring, and giant panda numbers are on the rise. The stories of some conservation heroes are told in a new book by science writer Michelle Nijhuis. It’s called Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction, and Michelle Nijhuis joins me from White Salmon, Washington. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

NIJHUIS: Hi, Jenny, thanks so much for having me.

DOERING: You know, one of the stories in your book, Michelle, that really inspired me was about Rosalie Edge, and her courage in standing up against these Audubon Society leaders the establishment that was really unwilling to protect birds that sportsmen considered pests or targets. She even bought a mountain to help conserve raptors. Can you tell us about her and her story?

The cover of Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction (Image: courtesy of W.W. Norton)

NIJHUIS: Rosalie Edge is one of my favorite characters too. Rosalie Edge, immersed herself in the suffrage movement. She was a leading suffragist fighting for women's right to vote. And after that victory was achieved after suffrage was achieved in New York State and after it was on its way to being achieved nationally. Rosalie edge and her husband separated and while she was mourning the breakup of her marriage, she discovered real solace in the company of birds. And she wrote very movingly about how the natural world was a comfort to her in the midst of this personal disaster. And so she became in her 40s a devoted birdwatcher. And as she got to know the birding community in New York City, she learned that the primary organization fighting for the protection of birds the Audubon Society was not sticking up for all birds. The Audubon Society was sticking up for the birds that it considered, quote, unquote, good birds, not birds of prey that many of its members considered pests at the time. So Rosalie edge thought this was ridiculous, and she took it upon herself to show up at a annual meeting of the board of the Audubon Society and give them a piece of her mind. And she rallied Audubon members and other people who cared about conservation to demand that the Audubon Society which had become a bit complacent. They demanded that the Audubon Society get more ambitious on behalf of other species and work for the protection not just of species that they happen to like and appreciate but all species.

DOERING: Yes and they wrote some pretty fiery pamphlets that just got sent out, I guess, mailed out by the hundreds calling for this establishment to take a stand.

NIJHUIS: Well, they were very popular, they named names and, you know, warned of what tragedies would befall the natural world if the Audubon Society didn't grow some kind of backbone. And she made herself a real pain in the neck. And she succeeded. she succeeded at waking up the Audubon society's leadership and membership. And I think that the Audubon Society retains a sort of grassroots feistiness that owes a lot to Rosalie Edge.

DOERING: And some of these birds that weren't being protected properly. Were raptors like hawks especially. Why were these Raptors under such attack?

Conservationist Rosalie Edge and companions at the entrance of Hawk Sanctuary, 1940. (Photo: courtesy of Hawk Mountain Sanctuary)

NIJHUIS: Well, a lot of sportsmen did consider raptors pests. They had these exaggerated ideas about how often they ate farm animals and poultry mostly, and they just disapproved of them in a way they thought they were scavengers and kind of lowly animals. So there was a particular Ridgeline in Pennsylvania where the topography and the wind currents converge so that the hawks that were migrating up and down the East Coast in the spring and fall, were funneled over this one ridge top, so sportsmen would go there. And because there were so many raptors passing so close to the top of this ridge top, they were able to just shoot them by the dozens, even the hundreds. And Rosalie edge saw a picture of hot carcasses lined up on the forest floor and was just horrified that this was happening that this, you know, these birds were just being shot wholesale, really for no reason. And she found out that the land on that ridge top was for sale, and she bought it and established a hawk sanctuary that still stands today. And not only has it protected the Raptors that use that migration corridor. But the data taken there, Rosalie Edge, suggested that the caretakers start recording the numbers and kinds of birds that passed over during their migration. That data is now one of the longest record of raptor migration in the world.

DOERING: Wow, it sounds amazing to be there. And you did go there. What is it like to be on Hawk Mountain watching the raptors flyby?

NIJHUIS: I really recommend that people take a trip. It's not too far from most of the major East Coast cities but it is a different world because you climb up to the top of this ridge line, kind of an unassuming looking ridge line in Pennsylvania. But once you get up there, you realize how magical it is because the birds are flying by, not only above you, but sometimes beneath you. So it's not not only an amazing experience of being close to birds, but it's a popular place. And so most of the time you're up there with, it can be just a couple of other people or it could be a whole crowd of people who are all just gripped by this natural phenomenon. And it's delightful to feel their joy along with your own as you stand there and watch these birds do what they have done for so many years, and can do thanks to the foresight of Rosalie edge.

The view from the top of Hawk Mountain in Eastern Pennsylvania. (Photo: Mike Nichols, Flickr, CC BY ND NC 2.0)

DOERING: So another person who really helped shape conservation, and maybe a lot of people will know this name was Aldo Leopold, what do you think is his most important message for us today?

NIJHUIS: Well, many people may have run into Aldo Leopold's book, A Sand County Almanac. It's his best known book. I've always loved Aldo Leopold. And it was a real joy to get to know him better. In the process of writing this book, he was such an eloquent writer. And he had such a sense not only of the complexity of other species, but of the complexity of the human species. But his primary accomplishment, I think, was to bring the science of ecology into conversation with the work of conservation, because one thing I observed in learning about the history of conservation is that some people are drawn to conservation because they are eager to get away from their fellow humans, sometimes for very good reasons. Sometimes people, you know, had had a terrible loss early in life, and they found comfort in other species, or as I mentioned, like Rosalie Ed's, they experienced a tragedy, and they found solace and other species. But there are definitely people in conservation who feel more comfortable with other species than with their own. And Aldo Leopold was not one of those people, he he felt as warmly toward his own species as he did toward other species, I can't help but think that that informed his work. And that he saw, unlike so many conservationists, he saw that humans could have a constructive role to play when it came to conserving other species, that conservation wasn't just about protecting species from the destruction that humanity can wreak. It was also about finding that constructive role. And I think that's still a piece that's missing from conservation today. And that's something that Leopold can still remind us of.

DOERING: Yeah, that really resonates with the part of your book, where you're talking about the myth of the tragedy of the commons. And you know, the fact that it's handed us this idea that the only way to manage resources sustainably, whether that's like an aquifer or an antelope herd, is to impose this order from the top down. How has this been proven to be the wrong way of looking at conservation?

Aldo Leopold is considered by many to be a groundbreaking writer about wildlife ecology. (Photo: Pacific Southwest Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

NIJHUIS: The tragedy of the commons is a mysteriously persistent metaphor that was proposed in the late 1960s, by an ecologist named Garrett Hardin. And as you say, he theorized this was an idea he had not something he tested in real life. But he he proposed that humans given the chance would use up as many resources as they could until the resource was gone. And that the only way around it was total government control or total privatization. But scientists since then, and even while he was proposing this theory, were observing that that was not true at all, that people had for centuries, developed rules that allowed them to both sustain their own livelihoods and sustain the resources, the species that they needed. And I think the tragedy of the commons is persistent, in part because it does happen. And we do experience it in small ways all the time. Anyone who's been in a traffic jam has experienced the tragedy of the commons.

DOERING: Or trying to buy that last roll of toilet paper.

NIJHUIS: Yes, or trying to buy that last roll of toilet paper. I mean, it's it is all around us in small ways. But I think it's so important for everyone and for the conservation movement, in particular, to remember that it doesn't have to be that way that we as humans have figured out ways of avoiding it. And even as Garrett harden was publishing, the theory of the tragedy of the commons, in the journal Science, there was a young political scientist named Elinor Ostrom, who was reading his article and thinking, well, that's not true at all, because she was working on her PhD in Los Angeles at the time, and she had been observing that water users in the Los Angeles basin where groundwater is of course, you know, a highly prized resource, had figured out a way of cooperatively sharing their resource that didn't involve radical privatization that didn't involve total government control and and she devoted the rest of her life to studying systems all over the world where people were cooperatively managing their resources. And she eventually won the Nobel Prize in Economics for her work shortly before her death. So she's very respected and she, in fact, was the founder of a whole field that continues today. But I think that as respected as she was in his her work is still not as well known as it should be. I think it It hasn't had the staying power that the idea of the Tragedy of the Commons has, but I do hope that we as a society, we as a species, will embrace the complexity of Elinor Ostrom work because in that complexity, I think lies the solutions that we need for conservation to be meaningful worldwide.

Elinor Ostrom’s research presented an alternative to the “tragedy of the commons” and earned her the Nobel Prize in Economics. (Photo: Holger Motzkau, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: Yes. And you saw some of this complexity in action, you saw the importance of local involvement, you know, as opposed to like a top down government order or, or privatization, you know, communities really caring for the species and and the places that they've lived among for many, many years. So what did you take away from your visit to a community conservancy group in Namibia?

NIJHUIS: Well, I got to visit Namibia in southern Africa in the course of research for this book. And I was quite inspired by the work of the National Community Conservancy system in Namibia, which has been in place for about 30 years now. And the goal of community conservancies is to reawaken the relationship that local people had with their the species they lived alongside and have lived alongside for centuries. Before colonialization these species were often managed through the kinds of systems that Elinor Ostrom observed throughout the world. Colonization disrupted those systems and disrupted the relationship that people had with their local species. And it became quite common for people to think of other species, especially troublesome or dangerous species as the property of the government something that they they didn't benefit from. And they didn't have any responsibility for and they just considered kind of a burden. People often saw themselves as bearing all the burdens of conservation and and not realizing most of the benefits, they saw the benefits as as going to, you know, foreign tourists who visited national parks. The goal of the community conservancies is to restore that relationship by returning some conservation authority to the local level, giving people the ability to set their own hunting quotas, based on data that they help collect. They have the ability to earn money from tourism, they have the ability to earn some money from commercial hunting. And I was able to see some of this work in action. And I was so struck by it because I went to a annual meeting of one of the community conservancies in the midst of a deep drought, during a very tough time for the community. And the meeting on its surface was a little bit chaotic. There was an argument that broke out at one point, there were a variety of issues that needed to be handled. But when I got up to leave, I realized I was exhilarated in a way that I never am when I've gone to similar meetings in North America, in meetings with people who have far more resources and far more expertise available to them. And I realized I was exhilarated because people had taken the trouble to come to this meeting and think about the long term future of these species. And I think the success of the community conservancies is that they've reduced the burdens of conservation, enough conservation still cost something it's still is, you know, it still can be troublesome to live beside a herd of elephants, it still can cost money to restrict your exploitation of neighboring species. But it's reduced those costs enough so that people are willing and able to pay them. Because I think, at heart, most people don't want their neighboring species to go extinct. They're willing to go to some lengths to protect them. They just need to have some assurance that they have a say in how these species are managed, and that they have a way to support their families and to make a living. And I think once those things are in place, most people are quite willing to do what it takes to protect species for the long term.

DOERING: Michelle, at so many points in the history of conservation, you know, even as its leaders have accomplished great things like like saving species that were on the brink of extinction. They've gone about it in such a blinkered and misguided way a lot of the time and they've really left essential communities out of the process. So I guess I'm wondering now do you think the conservation movement has learned anything and what do you think is missing now from the conservation movement?

Michelle Nijhuis is an award-winning writer with a background in biology who focuses on stories about conservation and global change. (Photo by Darcy Hunter)

NIJHUIS: There is a long history of racism and colonialism in the conservation movement, which is not to say that the project of conservation that the work of conservation is necessarily racist or colonialist or to say that conservationists as a whole, have these blind spots. But it is to say that in every generation of the conservation movement, there have been people who have these very destructive, blind spots. One of the reasons I wanted to write this book is that I felt that it can only be good for conservation, for conservationists, to examine this history, to look at these patterns and see how they can be avoided in the future. I think the conservation movement, in many ways has learned from its mistakes. And there is a reckoning now over race and privilege taking place in society that I think the conservation movement is involved in in a very significant way. And I think many people are learning from that. And I think that's a very promising sign for the future. In the past, these blind spots have been so counterproductive for conservation because they have left out most of society, they have shut most of society out of the conservation movement. A more inclusive conservation movement will not only be a more just place to be an activist, but it will also be more effective, in that includes people in a constructive role in conservation.

DOERING: Michelle, Nijhuis is the author of Beloved Beasts Fighting for Life in an Age of Extinction. Thank you so much, Michelle.

NIJHUIS: Thank you, Jenni.

Related links:

- Learn more about Michelle Nijhuis and her work

- Learn more about the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary founded by Rosalie Edge

- Click here for the Beloved Beasts book (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Rikard From, “It’s an Upright Thing”, Rikard From]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth