August 6, 2021

Air Date: August 6, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Youth Mental Health Problems from Pollution

View the page for this story

Small particulates from fossil fuels are linked to as many as 300,000 excess deaths in the United States each year. Now, there is mounting evidence that these small, PM 2.5 particulates may also be harming the mental health of children and teens by worsening depression, anxiety, suicidality and more. Brian Bienkowski, the editor of Environmental Health News joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the correlation. (06:12)

Sea Lion Cave

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Sea lions can be extremely friendly and inquisitive but as Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, reports it’s still best to keep your distance. (03:01)

Colorado River's Dwindling Water Supply

/ Luke RunyonView the page for this story

The Colorado River that carved the Grand Canyon and now quenches the thirst of much of the American West is parched in a “megadrought.” Two key reservoirs are expected to drop to record low levels this year and trigger a formal water shortage declaration. Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River Basin and joins Host Steve Curwood from station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado. (11:23)

Climate Change Disrupts Major Transportation Corridor

/ Dan BoyceView the page for this story

I-70 is a transportation lifeline linking East to West and an engineering marvel as it barrels through the Rocky Mountains. But fires and mudslides along Glenwood Canyon are increasingly forcing I-70 to shut down, creating huge delays. As Colorado Public Radio’s Dan Boyce reports, it’s just one example of the transportation challenges linked to climate disruption. (05:04)

Science Note: Can Plants Hear?

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Flowers don’t have ears like ours, but research has found that some flowers, like evening primrose, can “hear” the buzzing of bees’ wings. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports on how these flowers sometimes quickly respond to nearby pollinators by sweetening their nectar. (02:02)

Confronting Climate Change Through Sound

/ Sandy HausmanView the page for this story

The seemingly constant onslaught of grim statistics and graphs about climate change may cause some people to shut down, unwilling or unable to process one of the most serious environmental issues of our time. To draw people back into a conversation about our changing climate, researchers at the University of Virginia are using something called eco-acoustics – sounds that illustrate the relationship between humans and their environment. Reporter Sandy Hausman has the story. (04:11)

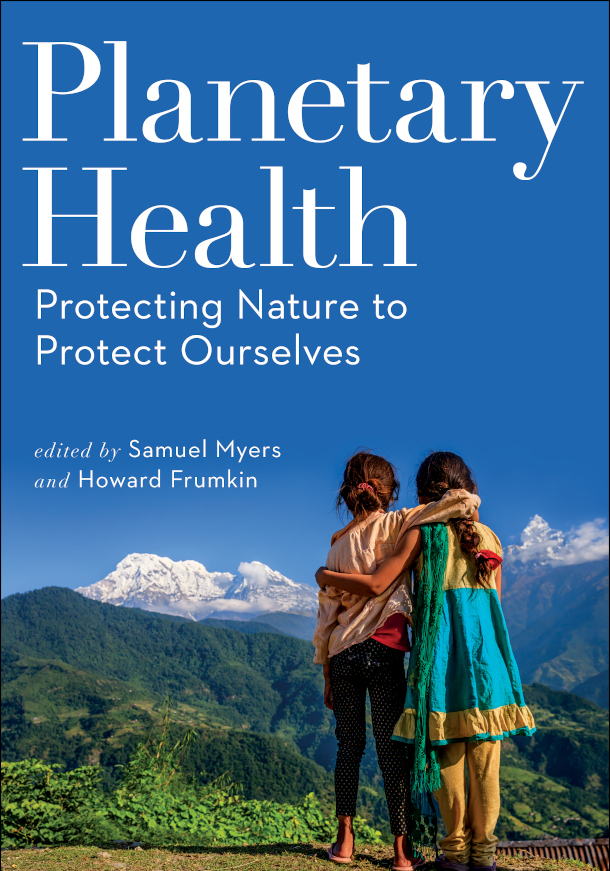

Planetary Health

View the page for this story

A healthier planet also means a healthier society. That's the basis of a 2020 book drilling down on the intersection of environmental change and human health. Physician Sam Myers co-edited Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves with Howard Frumkin. He joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss his book and to explain how saving the planet can also save human lives. (14:56)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210806 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Brian Bienkowski, Sam Myers

REPORTERS: Luke Runyon, Dan Boyce, Don Lyman, Sandy Hausman, Mark Seth Lender

From PRX this is Living on Earth

(THEME)

I’m Steve Curwood

As is much of the west the Colorado River basin is experiencing a megadrought, forcing tough decisions about who gets water.

RUNYON: If you compare it to the Mississippi River, it’s a very small river but because the area is so arid the reliance on the Colorado River is huge and there’s just not enough water supply to go around.

CURWOOD: Also, preserving the health of the planet to keep ourselves healthy.

MYERS: Planetary health is focused on understanding the human health implications of our own disruption and transformation of most of our planet's natural systems. How global environmental changes actually come back to threaten our own health and well being.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

Youth Mental Health Problems from Pollution

Children’s worsening mental health effects may be linked to small particulate matter air pollution, which comes from sources like the burning of diesel fuel. (Photo: Indiana Public Media, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Small particulates from fossil fuels like diesel, gas and coal are linked to roughly 300,000 excess deaths each year in the United States. Most of those deaths are in the form of strokes, heart attacks, and asthma. And evidence published in Environmental Health Perspectives suggests such small particulates, known as PM 2.5, may also be harming the mental health of children by worsening depression, anxiety and other troubles such as bipolar disorder and suicidality. Researchers at the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital examined over 13,000 emergency room visits, and looked back at recent exposures to small particulates. Brian Bienkowski is the editor of Environmental Health News, and he joins us now with more on the story. Welcome back to Living on Earth Brian!

BIENKOWSKI: Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: Statistics show that around one in seven kids in the US have a mental health condition. How many kids were looked at in this study?

BIENKOWSKI: So, they ended up examining about 6,800 children, and some of them had multiple emergency room visits over a five year span. So, it was about 13,000 emergency room visits for those kids.

CURWOOD: And when they went to the emergency room, they were psychiatric emergency room visits.

BIENKOWSKI: Right. So, we're talking about anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, kids who are experiencing thoughts of suicide. And these are usually cases that are pretty serious if you're ending up in the ER.

CURWOOD: And how bad was the air pollution that these children experienced?

BIENKOWSKI: So it varied. What the researchers did was look at an air pollution type called PM 2.5, which is very small, tiny particular matter. And for every 10 microgram per cubic meter of increase in this air pollution, they saw a large jump in emergency room visits for the kids. And this kind of pollution comes from you know, everything from traffic, to industry, to dust from wildfires.

CURWOOD: How did these levels compare to the federal guidelines?

BIENKOWSKI: All of the air pollution that they looked at, the kids were experiencing air that would not be regulated under the federal guidelines for PM 2.5.

CURWOOD: So, in other words, the air was considered safe.

BIENKOWSKI: Correct.

CURWOOD: There was some correlation between children's mental health and their exposure to air pollution. What other factors might have been examined during this study, say socioeconomic status or race?

BIENKOWSKI: So, kids that come from high poverty neighborhoods were more susceptible to the air pollution being correlated with more ER visits. The hypothesis is that poverty causes high stress, inflammation that can harm children's brains, all these things can exacerbate mental health disorders. And so, when you add in the air pollution, the idea is you get this double whammy approach.

Over 13,000 psychiatric emergency room visits, made by about 6,000 children, were analyzed for this study. (Photo: Eric Staszczak, KOMU, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, if we have one in seven children in the United States with mental health issues, and in many places, even federally-okay ambient air sending kids to the emergency room, how big a deal is this?

BIENKOWSKI: Well, it's hard to say, Steve. What we don't know is how or why the air pollution is causing these problems in children if in fact, it is. Some studies suggest, in laboratory animals, that air pollution can spur inflammation, oxidative stress, perhaps even impact our brain chemistry, our DNA. All of these would in fact, spur or exacerbate mental health problems in children. But we don't know that for certain right now, all we're seeing is these high correlations between children that do experience high exposures to air pollution, and going into the ER or reporting symptoms of mental health disorders.

CURWOOD: Now that we understand that there's a correlation between aggravation of mental health conditions, and particulate pollution, what advice, if any, is out there to help parents cope with this with their children if they have such mental health conditions?

BIENKOWSKI: So, the simple answer is when there's pollution try to get away from it. And that's just not for mental health disorders. We already know that air pollution is triggering asthma and lung problems and also heart conditions in people. So less pollution is better, even if this link is not yet fully proven. But this can mean keeping your children away from high traffic areas. If a nearby industry is going to have some kind of large emission event, to make sure that the children are indoors or not around that. If there's a wildfire or other sources of particulate matter, just try to make sure that the children are indoors and not outside breathing that air in.

CURWOOD: So, as I understand it, this study looked at five or so years of data from Cincinnati, Ohio. But there's been other research that suggests the link between worsening mental health and air pollution. Share some of that with us, if you could, please.

BIENKOWSKI: Sure. In fact, these same researchers right there in Cincinnati, they looked at traffic related air pollution and they linked it to the same cohort: children having higher anxiety. So, similar data, but looking specifically at traffic pollution. And then in the companion study, they found that traffic pollution was associated with more self-reported depression and anxiety in the children. So again, these are all correlation studies, but all kind of have that same finding. And then, I wrote about a large study of Danish and U.S. folks, and these were not children, but these were adults. And those who were exposed to high levels of air pollution had greater odds of suffering from all kinds of illnesses like depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. And some of these links were off the charts.

Brian Bienkowski is the editor of Environmental Health News. (Photo: Courtesy of Environmental Health News)

CURWOOD: So, the sources of particulate matter, 2.5 microns, scientists call it PM 2.5, are largely associated, I guess, with fossil fuels, and in particular, heavier fossil fuels like diesel and coal tend to have even more of this stuff.

BIENKOWSKI: Correct.

CURWOOD: And there's been some controversy. In fact, I think, even some concern in some communities about school buses that burn diesel, they idle. And there's a big cloud of particulates around kids that might be waiting to get on or those who sit in the back of the bus.

BIENKOWSKI: Right.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think this research adds to those concerns that people have about those exposures?

BIENKOWSKI: Well, I think it certainly adds to them. And if you think about what we already know about air pollution, again, you're talking about developing lungs in these young children. You're talking about links to heart problems with this particulate matter. We already have enough evidence to know that this is bad, that this is harming health. So, when you add on this layer of mental health research, it's just another strike against using these kind of fuels that we know are harming our health and the futures of our children.

CURWOOD: So, maybe if there's a bright side to this as we move to electricity for transportation and get away from burning fuel, maybe we'll be happier, huh?

BIENKOWSKI: Well, that certainly could be true. Save on healthcare costs, happier children.

CURWOOD: Brian Bienkowski is the editor of Environmental Health News. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Brian.

BIENKOWSKI: Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Is Air Pollution Worsening Kids’ Mental Health?”

- Click here to read the study in Environmental Health Perspectives

[MUSIC: Bob Zentz, “Horizons” on Songs for the Earth: A Tribute to Rachel Carson, M.U.S.E]

Sea Lion Cave

A solitary sea lion reaches above the surf to exhale. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Sea lions can be extremely friendly and inquisitive but as our Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, reports it’s still best to keep your distance.

Sea Lion Cave

Southern Sea Lion

Sea of Cortez

© 2021 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: This is the place where sea lions live. Islands of stone softened by time, the color of wood the color of shell in the Sea of Cortez. Underwater, the barking of the big males carries louder than in air. And further, and deeper.

Ahrr! Ahrr!

Ahrr! Ahrr! Ahrr! Ahrr! Ahrr!

Your body thrums when they pass beside you close enough to touch; but that would be a foolish thing to do. You don’t want to startle them. They might take umbrage. With a mouth full of teeth and they weigh a thousand pounds.

While I am… weightless. Enveloped, in a personal silence displaced only by the hiss and click of the regulator timed to the metronome of my breath. It is slack tide. There is no current to fight. I let myself drift into the underwater cave...

The floor is white sand made turquoise by water, the walls and ceiling high enough, wide enough there is no sense of entrapment and the ripples splash light all around. And the young sea lions arrive, more and more, each to see what the others have found, which is me.

A sea lion naps in the midday sun. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

They want to know every thing there is to know, about me.

One of them takes my arm in his mouth, his jaws smaller than his father’s but big enough and He works his way down, shoulder to hand, testing my wetsuit with just the pressure required to feel through the neoprene. Not yet sure… Is the suit just the suit and the part that gives differently, inside, something else? Another makes the same test, then swims away, then circles back so we are eye-to-eye except he is floating upside down and -

- BOOH! -

Blows bubbles in my face.

He covers the length of me back toward the opening of the cave in that easy liquid way in which they move. And just when it’s been long enough I think he’s gone -

Chomp! As hard as he can! And tugs with all the force his young body can deliver -

- on my flippers!

Because, by some sense some intuition or precocious knowledge he now knows: “This part is not you and there I can do whatever I want!”

As if, he has, a sense of… Humor!

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Learn more about author and photographer Mark Seth Lender’s work

- Read Mark's Field Note for this essay

- Special thanks to Destination: Wildlife

[MUSIC: Will Duncan and Bobby Horton, “Peace At Last” on The National Parks – America’s Best Idea (The Soundtrack), by Will Duncan, The National Parks Film Project/PBS Distribution]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Transportation challenges in the face of climate change. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at SailorsForTheSea.org.

[MUSIC: Keola Beamer, “Keiki Dream (Child’s Dream)” on Mauna Kea – White Mountain Journal, Dancing Cat Records]

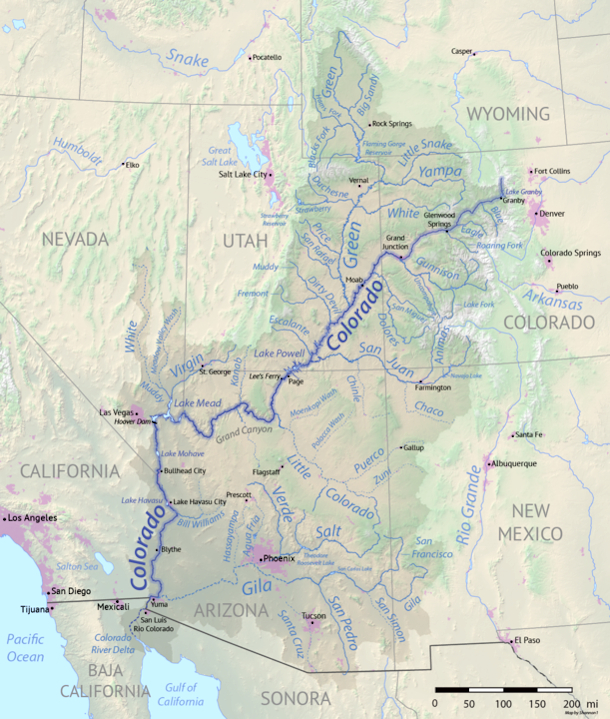

Colorado River's Dwindling Water Supply

The thick white “bathtub ring” at shrinking Lake Mead, which is impounded by Hoover Dam. (Photo: Ricardo Frantz on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The Colorado river that carved the Grand Canyon and now quenches the thirst of much of the American West is parched in a “megadrought,” with two key reservoirs at record low levels this year. Lake Mead behind the Hoover Dam is the biggest human made reservoir in the US and it’s now less than half full and our second biggest reservoir, Lake Powell behind the Glen Canyon dam, is even worse off at roughly a third of its capacity. With forecasts that hot and dry drought conditions could persist for years, the odds now favor the federal government declaring a formal water shortage in the Colorado River Basin. Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River Basin and is on the line now from station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado. Welcome to Living on Earth Luke!

RUNYON: Hi, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So Luke Runyon, you cover the Colorado River Watershed as a beat, huh? What's the extent of the watershed?

RUNYON: So the Colorado River flows through seven US states. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed. And California, Nevada and Arizona make up the lower watershed. It also crosses over the US-Mexico border and two Mexican states use water from the river as well. And it acts as a drinking water supply for some of the West's largest cities; when you think of Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Denver, they all pull water from the Colorado River. And it also acts as a really important agricultural irrigation water supply. You're looking at some of the most intensely farmed areas of the country: California's Imperial and Coachella Valleys use water from the Colorado River; the Yuma, Arizona area, which is kind of the "lettuce basket" of the country, that uses Colorado River water as well. So it's a really important water source for a large swath of the American Southwest.

Lake Powell is holding less than 35% of its capacity. (Photo: Zetong Li on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Wow, how big is the Colorado River flow when it's at its full-throated strength? Compare it to another major river for me, would you?

RUNYON: Well, it's actually, if you compare it to, like, the Mississippi River, it's a very small river. It, you know, it flows through some of the most arid reaches of the country. But we've tasked the river with a lot of different jobs. Because the area is so arid, the reliance on the Colorado River is huge. And there's just not enough water supply to go around. And so it's an intensely managed system in order to try and stretch it as far as we can.

CURWOOD: Now just how low today are the Colorado River water levels? We're speaking in May of 2021.

RUNYON: The Colorado River, you can kind of judge its health based on its two largest reservoirs. And this is Lakes Mead, and Lake Powell, which are in southern Utah for Lake Powell, and kind of the border between Nevada and Arizona, near Las Vegas, for Lake Mead. They are approaching record low levels. And that's because we've had essentially 20 years of above average temperatures in the basin, and below average flows on the whole over that 20 year period. And that's showing up in these reservoirs that are supposed to cushion between the really dry years. We're also seeing some changes in soil moisture, which is another thing, it's kind of like the hidden water bank. We always get so focused on surface water because we can see it, we can, you know, look at a river and know, oh, the river is high, or the river is low. But groundwater plays a huge role in the Colorado River Basin. And right now, soil moisture levels in parts of the Colorado River Basin are at the lowest that we've ever seen, and some much below the record. And you can kind of think of the ground as this giant sponge: when it's really dry, any new precipitation that falls, it's going to fill up that deficit that's left in the ground before it flows off into rivers. And so even a year where you have decent snowpack, you can see that snow not necessarily turn into a huge amount of water supply, because it's getting soaked up by that sponge in the ground.

CURWOOD: Now how much of the shortage in the Colorado River system is because of growing demand, that we have more and more people in places like Los Angeles and Phoenix and throughout the Southwest?

The Colorado River basin. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed, while California, Nevada, and Arizona make up the lower watershed and two Mexican states use water from the river as well. (Photo: Shannon1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

RUNYON: Demand definitely plays a role. But I think the biggest concern really is on the declining supply. In a lot of big cities in the West, demands have been flat, or in some cases have actually declined. And there are many different case studies of cities that have been able to grow while having their water demands either stay static or actually decline. The problem really is when you have the same amount of demand that you've had for a long time, but then the supply is shrinking. Those demands have to shrink along with that supply. And that's really the hard part. And those are the hard discussions that are going on in the basin right now, is, whose water supply should be curtailed in order for us to match the declining supply that we're seeing? And that's a really hard discussion to have, because we've built up massive cities and we've built up agriculture. We have all these expectations of what the river is is supposed to deliver to us and it just doesn't want to deliver that anymore, because of climate change and warming temperatures.

CURWOOD: So what are water officials on both, well, the regional as well as the national, federal level, saying they're going to do about this shortage?

RUNYON: It's not like there's one agency, or one overriding commission that makes all of the decisions on the Colorado River. It's managed by all of the people who, who depend on it. All of the various agencies and states, the federal government plays a role. And so it has to be collaborative by nature, because all of these various entities have to come to the table and decide who gets what amount of water. And they come to these agreements. And right now, all of these various entities are coming to the table, deciding how to implement old agreements and how to come up with new ones. And really, the driving question is, who has to use less water? The current agreement that the watershed is under is called the Drought Contingency Plan. It was passed in 2019. And really, it's kind of a band-aid to some of the past agreements that haven't been enough to halt the decline in some of these reservoirs. The Drought Contingency Plan lays out this series of cutbacks that Arizona, Nevada, Mexico and California have to take as Lake Mead declines. As the level of the reservoir gets lower, those states and the country of Mexico have said, we will take less water from the Colorado River.

Most of the water people take from the Colorado River quenches the thirst of crops like lettuce in Yuma, Arizona. (Photo: Tina Sibley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent would the federal government be in a position to come in and, say, declare an official water shortage situation? I gather if the Interior Department were to declare that there is an official water shortage in the Colorado River Basin, it would trigger, I would think, some reductions, even some mandatory cuts. What's the status of that at this point?

RUNYON: We're looking at a very high likelihood of an official water shortage being declared in the Colorado River Basin later this year. That declaration is tied to the level of Lake Mead. And so when Lake Mead dips below a certain threshold, within an agreement, it says that the Interior Secretary will be able to declare an official water shortage. And it's a bold statement, saying, we don't have enough water to meet everyone's needs.

CURWOOD: So Luke, to what extent can water conservation practices help alleviate the shortage, bring things back from the break?

RUNYON: It depends on the type of water conservation practice that you're talking about. If you're talking about like a large, systemic conservation initiative, like installing a new water recycling plant in a large city, that can play a huge role in, you know, ensuring that that city has enough water to meet the really dry times ahead. You know, a lot of cities in the Colorado River Basin have put some effort toward getting people to remove their lawns because outdoor residential water use is some of the largest water usage in a large metropolitan area. So I think the individual decisions that people make play a really big role. But the Colorado River Basin is such a large, complex system, it really takes states, large governments, federal agencies coming together to manage this crisis. Because really, these issues are so much larger than just the individual decision.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, what, 70, 80% of the water in the Southwest goes to agriculture, to growing things, even some things that are not very water efficient, like rice, or hay. What are ways that agriculture could conserve water to help alleviate this, this shortage?

RUNYON: You can talk to a lot of farmers who say, yes, we need to figure out how to use water more efficiently. You know, we need to be looking at different types of infrastructure, different methods to irrigate, maybe even different crops to grow in order to be more water efficient. You're also starting to see some of the states talk about what they refer to as demand management. So these are programs that would essentially pay farmers not to irrigate, and send that water downstream for another use or put it into a reservoir for later storage.

Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River basin for KUNC and 20+ NPR stations in the southwest. (Photo: Courtesy of Luke Runyon)

CURWOOD: You know, given the effect that climate disruption is having on drought and, and water usage, what's the long term outlook for water supplies in the West and Southwest?

RUNYON: Yeah, and I wouldn't want somebody to hear this conversation and think that, you know, we're quickly approaching Mad Max-style water wars in the Southwest. But I do think that there is a certain level of alarm that you're hearing from those who pay really close attention to the Colorado River. You're starting to see a lot more scientists, you know, water managers, saying that this is a huge issue and it needs a lot of attention and it needs a lot of investment in order to make sure that, that we don't approach the level where we're having people fighting over water in the Colorado River Basin.

CURWOOD: Luke Runyon is a reporter with KUNC in Greeley, Colorado, who covers the Colorado River Basin. Luke, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

RUNYON: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- KUNC | “With First-Ever Colorado River Shortage Almost Certain, States Stare Down Mandatory Cutbacks”

- The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation predicts at least 2 more dry years ahead for the Colorado River Basin

- About reporter Luke Runyon

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Peace” on Spirit, by Horace Silver, Jazz Legacy Productions]

Climate Change Disrupts Major Transportation Corridor

The Grizzly Creek Fire, which started on August 10, 2020, kept the I-70 highway closed for two weeks. (Photo: White River National Forest / U.S. Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: We stay in the west now in Colorado. I 70 is the only major interstate highway that runs over the continental divide in the Centennial State. And in 2020 it was closed for two weeks following the Grizzly Creek Fire in Glenwood Canyon. As Colorado Public Radio’s Dan Boyce reports, it’s just one example of the transportation challenges linked to climate disruption.

BOYCE: Summer 2020 was going gangbusters for Steve Nieslanik.

NIESLANIK: Prior to the canyon flows, it was the best five weeks we ever had.

BOYCE: He owns an Indian restaurant called ‘Masala and Curry’ in the Colorado mountain town of Glenwood Springs. Tourists were pouring over the continental divide from the densely populated Denver Metro area, looking for that COVID summer staycation. And they were using this area's biggest --really it's only -- major transportation artery, interstate 70.

NIESLANIK: And then, when the interstate closed, it was like none.

Many of Colorado's roads had to stay closed due not only to the fire, but to excessive traffic accidents. (Photo: White River National Forest / U.S. Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BOYCE: It was the Grizzly Creek wildfire burning through nearby Glenwood Canyon. The canyon is so steep, so narrow, that it can't even accommodate for interstate lanes. Instead, a massive bridge deck built into the cliff side carries the westbound lanes above the eastbound lanes for miles, all while the Colorado River rushes on down below. Paul Chinowsky teaches environmental design at the University of Colorado. He says the corridor already has its share of dangers.

CHINOWSKY: These great cliffs, thiet grades -- these are perfect areas where we could have risk from roads being closed due to boulders coming down.

BOYCE: Or landslides or flash floods or avalanches -- all kinds of stuff. All right, fine, but we got to get across the mountains, right? Janoski says trouble is hen these roads were built, engineers were using their perception of the local environment at the time to judge risk factors.

CHINOWSKY: The issue with climate change is all of these factors are changing.

BOYCE: Chinowsky helped author the transportation chapter of the most recent national climate assessment. It says “increased drought and heat, coastal flooding and more heavy rain events. All of it will decrease the reliability of the nation's travel infrastructure and increase the cost to maintain it.”

The Grizzly Creek Fire closed interstate-70 for two weeks back in August. Even still, there's a section of Glenwood Canyon reduced to one lane of traffic each way. The canyon walls consist of these striking horizontal layers of crumbling rock hundreds of feet high, layers normally covered in greenery. Now, what you notice is so much of it is black and charred.

A boulder fell from the cliffs and crashed into the guardrail, bending it, before the rock shattered, leaving debris scattered. (Photo: White River National Forest / U.S. Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

LEW: You can see right behind you that the fire came right up to the road.

BOYCE: That's Colorado Department of Transportation director Shoshona Lew on a recent tour of the canyon for state officials. With the stabilizing vegetation now gone from the cliff sides, this stretch will see problems for years. More rock slides, avalanches, and closures from future rain and snow storms, storms that climate change make harder to predict. Lou says her department does have a team of geohazard experts.

LEW: They know what to look for when a rock could be vulnerable and they know how to identify when we need to take rocks down in order to avoid the falling into the road.

BOYCE: Meanwhile, the U.S Geological Survey is placing monitoring devices through the stretch to help landslide prediction models and the U.S Forest Service is looking into the potential for revegetation.

Examine just this most recent interstate 70 closure and quickly see cascading consequences. Greg Fulton runs a Colorado trade group focused on the trucking industry.

FULTON: A lot of the time we look at I-70 as almost our own little neighborhood street sometimes.

BOYCE: Of course it isn't, though.

FULTON: Businesses and consumers throughout the country get affected when there's any significant closure of this highway.

BOYCE: You see there just aren't that many reliable ways for a semi-truck to get over the Rocky Mountains. Fulton says the Colorado options besides I-70..

FULTON: They’re twisting and we don't have as much in the way of passing lanes. Nor is there any truck parking there.

The sky appears orange and smoky as the Grizzly Creek Fire continues to rage. (Photo: White River National Forest / U.S. Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BOYCE: He says truckers outside Colorado will often opt to bypass the state entirely during an I-70 closure. More mileage, more money, more time. Colorado senator Michael Bennet on that Glenwood Canyon fire tour paints what happened here as an opportunity.

BENNET: We need to put more people to work in our forests doing the fire mitigation and the work that can be done to help prevent these fires from happening in the first place and make them easier to fight when they happen.

BOYCE: That could mean a lot of jobs in the rural West. Congress would have to pay for them though. And looking at transportation spending, the American Society of Civil Engineers estimates there's already a $1.2 trillion dollar gap in funding for travel infrastructure nationally. And that's before the impacts of climate change are taken into account.

CURWOOD: That’s Colorado Public Radio reporter Dan Boyce.

Related links:

- Learn more on the Colorado Department of Transportation Website

- Read more on CODOT’s 50th Anniversary of the Interstate System

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “Rhythm Of the Desert” on Southwest, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

Science Note: Can Plants Hear?

Researchers observed that when evening primrose was exposed to the sound of a flying bee, or similar (but synthetic) sound-signals, the flowers began to excrete sweeter nectar within three minutes. (Photo: TJ Gehling, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Coming up after the break, protecting human health by protecting planetary health but first this Note on Emerging Science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

[SFX BUZZING OF A BEE]

LYMAN: Humans can hear the gentle buzzing of a honey bee with our ears of course, but it turns out that some flowers can also hear the sound of their favorite pollinators. Well, kind of…researchers at Tel Aviv University recently found that the concentration of sugar in the nectar of evening primrose temporarily increased within minutes of sensing vibrations from pollinators’ wings. The researchers suspect the flowers act like ears, and can pick up the specific frequencies of bees’ wings, but are able to tune out background noise, like wind.

To test their hypothesis, scientists exposed plants in the lab to five sound treatments: silence, recordings of a honeybee from four inches away, and computer generated sounds in low, intermediate and high frequencies.

Plants under sound proof glass jars – the silence group – as well as plants in the intermediate and high frequency groups,

[SFX]

had no significant increase in sugar concentration in their nectar.

But plants exposed to recordings of bee sounds

[BUZZING]

and similar low-frequency sounds

[LOW FREQUENCY SOUND]

produced as much as 65 percent more sugar in their nectar within three minutes of exposure to the recordings.

The researchers believe that sweeter nectar may attract more pollinators and increase the chance that bee detecting evening primrose will cross-pollinate with other plants and pass on their bee hearing genes.

Evening primrose and other plants “hear” due to how their petals vibrate when sound waves pass them by. (Photo: U.S. Forest Service, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The researchers also conducted experiments that showed that the bowl-shaped flowers of the primrose picked up and amplified sound vibrations.

This single study has opened up a new field of scientific research, which the researchers call phytoacoustics.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Smithsonian Magazine | “Flowers Sweeten Up When They Sense Bees Buzzing”

- Read the original article published in bioRxiv here

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[MUSIC: Eric Tingstad, “This Train of Thought” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records]

Confronting Climate Change Through Sound

As glaciers shift and melt, many unsuspected sounds can emerge from the ice. (Photo: Unsplash, Vince Gx)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. When we see statistics and graphs about climate change, many of us may start to shut down, unwilling or unable to process one of the most serious environmental issues of our time. To draw people back into a conversation about our changing climate, researchers at the University of Virginia are using something called eco-acoustics – sounds that illustrate the relationship between humans and their environment. Reporter Sandy Hausman has the story.

HAUSMAN: Willis Jenkins teaches religious studies, but lately he’s been called to the coast, to record the sounds of sea level rise and oyster reefs.

JENKINS: When you hear the reef recording you’re going to hear a snapping or cracking sound, and that is actually pistol shrimp, and then you can also hear kind of micro-currents of water moving in and around the reef, and there may be a few low fish calls.” And then every now and then theres a discreet low sound as the oysters metabolism expels undigested food from it’s gut.

HAUSMAN: People who hear that recording are drawn into dialogue.

JENKINS: The sound element is so captivating that people ask lots of questions about it, and then they begin to ask questions about organisms and data change over decades, in conversations that typically go longer than if I were to just tell you about the health of these wetlands.

HAUSMAN: His colleague in UVA’s music department agrees. Matthew Burtner is now working from a cabin near Anchorage, where he’s recording glaciers as they melt slowly --- or suddenly fall into the sea.

[GLACIER FALLING SOUND]

BURTNER: It’s an amazing symphony of sounds actually. There are incredibly low, booming sounds. They sound like jet engines up close as these large pieces of ice calve and fall, and then there are most delicate tinkling, trickling sounds that you’ve ever heard – these little tiny patterns of water moving across the ice as the ice melts and creates little tiny melodies, little tiny rhythms, and the whole surface of the glacier is just alive with sound.

[WATER DROPS SOUND]

HAUSMAN: After recording the sounds of the arctic, he translates climate data into notes and combines them to create compositions that tell the story of global warming. Hearing it, he says, is fundamentally different from reading or talking about climate change.

BURTNER: A lot happens when we shift our focus from looking at the world and moving in the world to just listening to the world. It’s a more contemplative way of being. If we could understand the glaciers as a complex symphony of sound the way we listen to Beethoven, that could do a lot for our relationship to the natural world.

HAUSMAN: The work itself is challenging. It was 65 degrees in Charlottesville when I reached Burtner in Alaska’s Chugach Mountains. There, he said, conditions were very different.

BURTNER: Today it’s three degrees and it’s snowing outside. You know, to do anything you have to shovel out and then you’re constantly trying to keep the equipment warm, because the equipment is not designed to function in sub-zero temperatures.

HAUSMAN: But he loves being outside in any weather, and recording off the Eastern Shore is a pleasure. He and Jenkins can now assess the health of an oyster reef through sound and monitor the size of crustaceans by listening to what they call crab flutes – sounds heard as the wind blows over holes in the sand.

BURTNER: We hoped to be able to record the crab, but the crab made almost no sound, and we couldn’t hear it, but we could hear the wind whistling over the top of the crab flute – this wind instrument that the crab has made.

HAUSMAN: You can hear Burtner’s work on his newly released album, Glacier Music on Revallo Records, featuring what will surely be a hit song entitled the “Syntax of Snow”.

For Living on Earth, I’m Sandy Hausman.

BASCOMB: Sandy Hausman’s story comes to us courtesy of WVTF in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Related links:

- Read the original story from WVTF

- More on Pistol Shrimp

[MUSIC: Snorre Kirk, “Pastorale” on Stunt Records Compilation Vol. 25, by Snorre Kirk, Sundance Music/Stunt Records]

Planetary Health

Planetary Health delves into the intersection of environmental change and human health. (Image: Courtesy of Island Press)

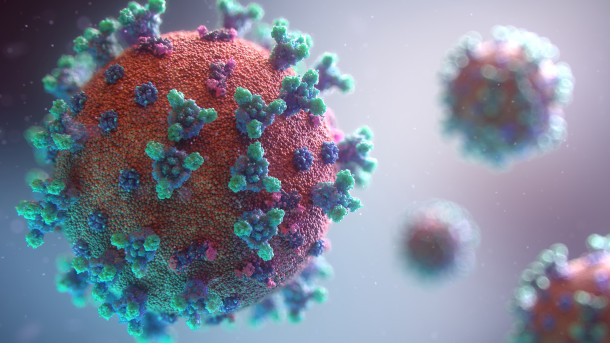

CURWOOD: Human health is an integral part of any discussion about our changing planet and with the pandemic, it is more relevant than ever. Scientists say that our impacts on the environment increase the risk of pandemics. Deforestation, for example, brings us closer to animals that might have zoonotic diseases like Covid 19. And our agricultural system relies on large livestock farms that could serve as reservoirs for viruses. Physician Sam Myers studies the intersection of environmental change and human health. As part of our LOE Book Club live event series, I spoke to him about his book Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves, co-edited with Dr. Howard Frumkin. Sam is the director of the Planetary Health Alliance and also a principal research scientist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health.Welcome to Living on Earth, Sam!

MYERS: It's such a pleasure to be here with you, Steve. Thank you.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. So Sam, the book we're talking about, it's named Planetary Health. This is the name of a brand new field of study and consideration that you've been involved with since the very beginning. So please tell me, what is planetary health? And how did you get involved in this field?

MYERS: Yeah, well, so you're right. Planetary health is a very new, very interdisciplinary field that I think has really emerged out of this moment that we globally find ourselves in. And it's a field that's focused on understanding the human health implications of our own disruption and transformation of most of our planet's natural systems. So it's about how global environmental changes actually come back to threaten our own health and well being.

Environmental change can impact the spread of infectious diseases like COVID-19, but also non-infectious diseases like diabetes. (Photo: Trinity Care Foundation, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And I suppose if biologist E. O. Wilson were with us at this moment, he'd say, well, what do you expect we we all evolved from this particular ecosystem? And you would say?

MYERS: Yeah, I would say that we've evolved over four million years in close conjunction with a set of actually relatively stable biophysical conditions and that now we are changing those biophysical conditions really across the board at the fastest rates in the history of our species. And so it isn't that surprising that those biophysical changes are translating into some pretty significant threats for human health across just about every dimension of health.

CURWOOD: So now, let's zoom in for a moment to one of the sections of this book. And I have to say you have many, many fascinating, interesting sections. And, it's a shame that we don't have five or six hours to go through everything that you have in this. But let's look at one section. You have a chapter on mental health on a changing planet. For a lot of people, this isn't such an obvious topic. But please tell us why you and Howie Frumkin thought this was important to include.

MYERS: Yeah, I think that mental health is one of the, you know, really understudied and under emphasized, but maybe one of the most important areas where accelerating environmental change is threatening our health. And, you know, there's a very large sort of well established body of evidence around the mental health effects of big disasters, we know that these fires across the West Coast are going to have an enormous mental health toll. We know that the big hurricanes have, you know, huge mental health effects in terms of depression, anxiety, job loss suicidality, and we know that those impacts are actually very robust and long lasting. So if you go back to Katrina victims, 10 years, 15 years later, you're still seeing mental health effects in those populations. But there's this whole realm of much more subtle mental health effects that people are starting to call eco anxiety or ecological grief. And, you know, it sort of begs the question, what is the burden that we carry with us of knowing that our own actions collectively are sort of systematically dismantling natural systems? What's the mental health burden people experienced when we learned that about two thirds of the mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fishes that used to inhabit the planet have been pushed off the planet by our own, you know, activities, and there's a whole area of research now starting to try to understand what those burdens are that may be almost invisible, but could still be very significant.

CURWOOD: So Doctor, I know you're very early in this process, but what treatments have you come across that are going to help with this intense pressure on our mental health?

MYERS: We talk about that very specifically in the mental health chapter that, you know, collective action, movement, building, social organizing, coming together to take action is not only necessary, it's also therapeutic. You know, Chris Jordan, who is a producer and an artist and did this amazing film Albatross about the challenge of plastics in our oceans, talks about how grief is the other side of love. And I think that's true. I think that if we love something, and it's in distress, then we grieve for it. And so I think the first step is to acknowledge that things are really challenging and that it's extraordinary that almost every single person in this country right now tonight, as we speak, is experiencing in some form or another some kind of ecological associated threat. But then we need to move from acknowledging the grief to coming together to take collective action. And I think that's why some of the movement building that's been going on over the last couple of years is so exciting. Whether we're talking about, you know, the climate strike movement and Greta Thunberg, or we're talking about the Extinction Rebellion, or we're talking about the birth strike movement, or, you know, any number of other kinds of social movements that not only are they the only way to address big power problems, where people actually have to hold governments and industries accountable to take the right actions, but they also bring us together, which is itself a therapy, I think, against the kind of ecological despair that I'm talking about.

Carbon dioxide has been shown to affect the levels of iron, zinc and protein in staple food crops. (Photo: Ellenm1, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sam, let's talk about another section of your book. And this, of course, actually a couple of sections on disease. In one section, you detail infectious diseases, I'm thinking of malaria, along with non infectious diseases: cancer, diabetes, heart disease. Tell us please about the correlation between environmental change and the risk of disease.

MYERS: Well, it's a huge topic, it's really kind of the first half of our book. And, you know, it's people tend to gravitate in their heads toward infectious diseases, we think about the hot zone, we obviously are all thinking about COVID now. We think about Ebola. And certainly, all kinds of biophysical change is associated with big changes in infectious disease exposures. But in a lot of ways, it's the non infectious diseases that are likely to drive the largest global burdens of disease. And so yeah, for example, the non communicable diseases. A big report came out a couple of years ago about global pollution of air, water and soil, showing that about 9 million excess deaths a year are attributable to pollution. And those deaths are non communicable diseases, their heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, some kinds of cancers, you know, the mental health effects that we just talked about, you know, and then there's this huge category of nutritional diseases, which is where I do a lot of my own research, where we're seeing biophysical changes associated with changes not only in the quantity of food that we can produce, but also even the quality.

CURWOOD: Yeah, Sam, let's drill down, in fact, on some of the research that you're doing on nutrition, it's now a number of years ago that we first noticed here on Living on Earth, the work that you were doing, showing that as carbon dioxide levels went up that this was bad news for a number of commodity crops. So talk in some detail about your research here in this area of nutrition during these times, please.

MYERS: So I wear two hats, I direct the Planetary Health Alliance, and then I'm also a research scientist. And so with my research, I'm engaged in a bunch of research projects, and most of which really look at how changing biophysical conditions affect nutritional outcomes around the world. And so one example is the work you were talking about where with a team of people all over the world, we're looking at this question of how rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere might affect the nutritional quality of staple food crops that we depend on for our nutrients. And what we found a while ago was that when you grow crops at carbon dioxide levels that we expect to reach by the middle of this century, they lose a lot of their iron and zinc and protein, really essential nutrients for human health. And so we spent several years after that initial finding, then modeling the diet of populations in 152 countries around the world to understand how these nutrient changes would actually alter the total sort of intake of those nutrients for people around the world. And whether it would push them into deficiencies of those nutrients, which are very serious public health problems. And what we found was on the order of 150 to 200 million people would be likely to be pushed into new risk of deficiencies like zinc and protein as well as you know, the billion or so people who already aren't getting enough those nutrients in their diets. And so that's just one small example of how, in a way that was almost impossible to anticipate, which is another theme in Planetary Health, right? These surprises and these unintended consequences, but who would have thought if we were sitting around 20 years ago, having a beer that, you know, adding carbon dioxide would make our food less nutritious. But, you know, that's one impact of adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, and yet it potentially affects hundreds of millions of people.

Sam Myers is the director of the Planetary Health Alliance and a principal research scientist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. (Photo: Sam Myers)

CURWOOD: So what about solutions? Then let's just drill down for a moment on the question of solutions in this food and nutrition area. What things do you want to point to?

MYERS: Well, I mean, I think there are you know, there are solutions that we could point to around these specific questions like CO2, but that's really a tiny little piece of the big picture, you know, big picture is that our food system is probably more responsible for our transformation of the global environment than anything else. We use 40% of the terrestrial land surface for crop lands and pasture about half the accessible freshwater mostly to irrigate our crops, we're fishing out, you know, 90% of monitored fisheries so that there's a huge ecological footprint to our food system. And then the flip side is that environmental change is creating these enormous headwinds in producing food right when we need to roughly double food production in order to keep up with demand. And so we have this sort of, eye of a needle that we have to thread between destroying the biosphere by expanding agricultural production and still feeding 10 billion people. And, you know, that's where the, we really need to think about solutions. And we're starting to see that we're seeing you know, precision agriculture really taking off in the use of robotics to be much more efficient in how we use agricultural inputs, we're seeing new things like impossible burger or protein fermentation, the production of synthetic milk, or eggs that actually has a much, much, much smaller ecological footprint and is presumably considerably healthier for us to consume. Ther’e all of these innovations that are taking place, they're also our old tried and true methods from agro ecology, that are being shown through research to be much more effective, you know, more profitable with much lower ecological footprints. So when you start to look at this whole sort of huge menu of solutions that can be drawn from and you see similar things across energy systems and urban design. That's what I mean about this sort of rich terrain of solutions.

CURWOOD: So we just need the willingness, huh Sam?

MYERS: So I really think it's a matter of political will, yeah.

CURWOOD: I mean, I think probably an interesting example is bacon. I think many people will see bacon is, you know, really not very healthy. And yet, if you put it out, especially around the campfire, it'll disappear in a moment. How do we change?

MYERS: Well, I think we are changing. I mean, I think that the COVID pandemic has taught us that we're capable of actually changing in profound ways very quickly, which we didn't even know about ourselves. I think we have to start by the diagnosis, we have to start by recognizing that we're in really an extraordinary moment in human history. It's an inflection point, we cannot continue on our current trajectory, you know, our global house is on fire. And so we have to, we have to be motivated by the fact that we can't stay on this course. And then I think it's more than policy. I think it's it's more than what governments can do. I think that ultimately people and this goes back to your question about mental health, people need to come together to take collective action to organize and to hold their governments, you know, accountable and insist that stimulus packages are spent, you know, towards Green New Deals or, you know, other kinds of investments in infrastructure that could, that's going to take us in the right direction. At the end of the day, I think, you know, there's a spiritual sort of cultural dimension to this, we need to tell ourselves some different kinds of stories about our relationship to nature. And, you know, underlying all of these sort of ecological and public health crises, there's, I think, a spiritual crisis, where we've kind of lost our way and we've lost our sense of connectedness to the natural world.

Solastalgia describes the emotional distress caused by environmental change. (Photo: pandrii000, PxHere, Public Domain)

And I think we need to move from stories of sort of exploitation and dominance, which underlies so much of our action to stories of, you know, regeneration and reciprocity and codependence with natural systems. And so, you know, there's a role for our artists and our spiritual leaders in kind of getting us back on track on that level as well.

CURWOOD: Again, Sam, thanks so much for taking the time and congratulations for two years of hard work that I think people are going to use for many years going forward as a resource.

MYERS: Thank you, Steve. It's a great pleasure to be with you, I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- More on Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves

- More on Sam Myers

- LOE’s previous coverage with Sam Myers on how CO2 affects nutrients in food

[MUSIC: David Chevan and Warren Byrd, “Let Us Break Bread Together” on Let Us Break Bread Together: Further Explorations of the Afro-Semitic Experience, traditional African-American, CD Baby]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Anna Canny, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joshua Siracusa, Tivara Tanudjaja and Jolanda Omari.

Special thanks this week to Destination wildlife.

Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Steve Curwood

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth