February 18, 2022

Air Date: February 18, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Green Voter Opportunity

View the page for this story

The Environmental Voter Project has spent years identifying registered environment-first voters and motivating participation. Their recent research found nearly 1 million environmentalists who voted in the 2020 presidential election but have never voted in a midterm election. Nathaniel Stinnett, founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about why these so-called environmental drop-off voters could be decisive in the 2022 midterms if they show up at the polls. (12:53)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Koalas are endangered. This iconic Australian species has suffered from habitat loss and wildfires. Host Steve Curwood and Peter Dykstra, an editor at Environmental Health News discuss Australia’s response. On a more optimistic note, one of America’s biggest utilities, Duke Energy, is pledging to quit coal by 2035 and become carbon neutral by 2050. And from the history books, DuPont is awarded a patent for nylon and begins integrating plastics into our lives and environment. (05:11)

Love Overwhelms National Parks

View the page for this story

Amid the restrictions and stresses of COVID, throngs of visitors seeking the solace of nature at many of our national parks threaten to overwhelm the chronically underfunded and understaffed park system. Kristen Brengel, Senior Vice President of Government Affairs for the National Parks Conservation Association, discusses these challenges with Host Bobby Bascomb. (12:03)

Black History on the Mississippi

View the page for this story

After 1865 Black Americans freed from the sugar plantations of slavery rose up and built thriving communities in the deep rich bottom land along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. But a century later, the petrochemical industry moved in and now more than 150 facilities pollute the air, land, and water in what’s been dubbed Cancer Alley. Sharon Lavigne, the founder of environmental justice group RISE St. James, joins Host Steve Curwood to share her memories of what her home was like before industrial poisoning, and to talk about the ongoing struggle to protect its residents. (17:08)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220218 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Nathaniel Stinnett, Samantha Freeman, Kristen Brengel, Sharon Lavigne

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Voters who rank the environment as their number one priority could be crucial in the midterm elections in key battleground states.

STINNETT: Each of these eight states has a combination of important and competitive Senate races, and gubernatorial races and House races...These are important states, where infrequent environmental voters can make a really, really big difference if we show up.

CURWOOD: Also, a call to end the tragic black history so far in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley.

LAVIGNE: I was diagnosed with lead in my body, I was diagnosed with aluminum in my body. I was diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis, I researched it and it said it came from industrial pollutants. How much more do they need? Do they need all of us to die to have proof?

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Green Voter Opportunity

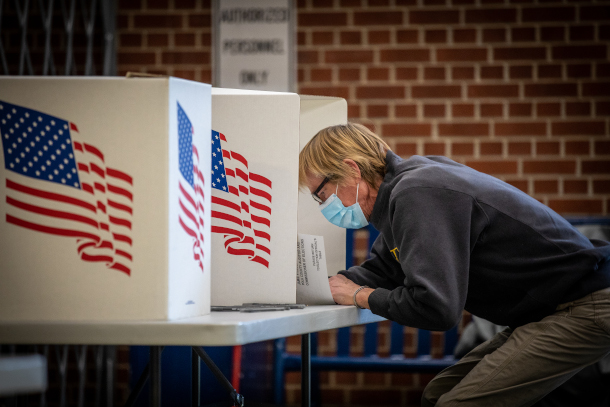

Almost 1 million environment-first voters cast a ballot in the 2020 election, but have never voted in a midterm election. (Photo: Cindy Shebley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

To date the United States Congress has done nothing major to combat the growing dangers from climate disruption, though it came close in 2009 when the Waxman-Markey bill was passed by Democrats in the House but derailed in the Senate by the filibuster. And so far, along with Democratic caucus defections, the threat of a filibuster still looms large in the failure to take climate action by the present Congress. Political consultants say there are enough potential environmental activist voters who could shift the balance of power in Congress in the upcoming mid-term elections if they get out to vote, and those consultants include Nathaniel Stinnett. Nathaniel Stinnett is founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project, which looked at environmental voter data from eight battleground states. This research finds that nearly 1 million environmentalists who voted in the 2020 presidential election have never voted in a midterm election. He joins me now to explain how these so-called environmental drop-off voters might make an impact this fall. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Nathaniel!

STINNETT: Thank you so much, Steve. I always love chatting with you.

CURWOOD: As do I. Now, remind us, how does the Environmental Voter Project define an environmental drop-off voter?

STINNETT: So these are voters who in our targeting research show up is having a really high likelihood of not just caring about climate or the environment, but literally listing it as their number one priority. But we see from public voter files that they vote in presidential elections, but not in midterms. So that's where that term drop-off comes from. And as you can imagine, these are important mobilization targets for campaigns, because they may not be great voters, but they at least have some history of voting. They're the closest to being pulled off the sidelines.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel, let's talk about the states that you looked at here.

STINNETT: Yeah, so we studied eight states, so Arizona, Nevada, Texas, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, for two reasons. First, they have huge populations of non-voting, and infrequently-voting environmentalists. So these are the states where the climate and environmental movements have a lot of untapped political power. And then the second reason is, they're all midterm battleground states. So each of these eight states has a combination of important and competitive Senate races, and Gubernatorial races and House races. So we knew this data would be both timely and important in 2022. These are important states, where infrequent environmental voters can make a really, really big difference if we show up.

CURWOOD: So now, what are the demographics of these environmental drop-off voters? How do they compare to overall environmental voters and voters in general?

STINNETT: So, they're very similar to overall environmental voters. So the difference between these drop-off voters and other environmental voters isn't that different. But when we look at how they compare to the overall electorate, these environmental drop-off voters are younger, they're more likely to be women than men. And they're more likely to be people of color than white, with especially large groups of Hispanics and Asian Americans. So to give you an example, let's look at Pennsylvania. So, Pennsylvania is one of the states that we studied. In Pennsylvania, women outnumber men among these drop off voters by 18 percentage points. Asian Americans make up 3.8% of these environmental drop off voters. And that might not sound like a lot. But Asian Americans are only 1% of the overall population in Pennsylvania. So they're almost four times as prevalent among these environmental drop off voters as they are in the whole electorate.

The Environmental Voter Project identified several battleground states with potential for environmentalists to make decisive change with their voting power. (Photo: Phil Roeder, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What are some of the numbers? Let's keep talking about Pennsylvania. How many voters there that will make a difference in the midterm elections? And how do the environmental drop-off voter numbers compare to the key margins in those races?

STINNETT: Yeah, so that's a great question. So first, let me give you some context. In Pennsylvania, if we go back to the last midterm election in 2018, a little over 5 million ballots were cast. We have identified 185,000 of these environment-first drop-off voters. So that's a pretty pretty big number, even out of the 5 million ballots that were cast. But let me give you some more context, because we all know that Pennsylvania is an important state, and boy are the margins tight there. So let's look at 2020 and 2016. In 2016, Donald Trump won Pennsylvania by 44,000 votes. In 2020, Joe Biden won it by 80,000 votes. So the fact that there are 185,000 of the super environmentalists who vote in presidentials, but not midterms, is really, really important. I mean, this is a huge pool of latent political power for the environmental movement in a really important state.

CURWOOD: Now, in the 2020 elections, certainly the numbers of people that your environmental voter projects encouraged to get out. Those numbers were larger than the margins by which the Senate races and for that matter, the Presidential race was decided there. So which states now do you find most intriguing for these midterm elections?

STINNETT: So a lot of the states that we we studied, Steve, have huge numbers of these infrequent environmental voters, particularly Pennsylvania, Arizona, New Hampshire. But the state I am totally obsessed with during these midterms, Steve is Nevada. Nevada, has over 56,000 of these environmental drop off voters, which would be a big number in any state but in Nevada, that's truly enormous. So for context, 975,000 people cast ballots in the 2018 midterms in Nevada. So what that means is these environmental drop off voters are equal to almost 6% of all ballots cast in Nevada's last midterm. So that's a huge pool of potential political power. And then when you combine that with the fact that Nevada is going to have a competitive gubernatorial election, a competitive US Senate election, and three out of their four House districts are going to be competitive. Well, that means these Nevada environmentalists won't just impact the future of their own state, they could very easily determine all our futures, they could determine the Senate, they could determine the House, they could determine so so much. So I encourage everybody out there: don't sleep on Nevada this year, it's going to be a crucially important state.

Help us turn 1 million environmentalists from presidential voters into midterm voters. https://t.co/DqwFqXhfjy #ClimateActionNow #ClimateAction #ActOnClimate

— Environmental Voter Project (@Enviro_Voter) January 28, 2022

CURWOOD: And Nevada is relatively closely divided, right? It's not particularly red, it's not particularly blue, but purple, is the way some of you political folks refer to it.

STINNETT: That's exactly right. It is absolutely a purple state. All of those competitive races that I just mentioned, are really, really close. Now, obviously, we're nine months out and polls change, but they're very, very close. And so yeah, this is one of the most purple of purple states. And it often gets overlooked for the Georgias and Arizonas and Pennsylvanias of the world. But Nevada is razor razor thin, these margins.

CURWOOD: So Nathaniel, talk to me about Arizona, what's going on there? We've seen a supposedly Democratic senator hold out against the President for what could have would have been climate action. And there's a Senate race there for the other seat for the chap who just finished out a term.

STINNETT: Yeah, Arizona is so important. And it's also such a huge opportunity for the environmental movement in 2022. And here's what I mean by that. First, there's a competitive Senate race, a competitive gubernatorial and at least four maybe more competitive House seats. The second reason is there are over 101,000 of these environmental drop-off voters that we've identified in Arizona. That is a number so large that it equals 4.3% of all ballots that were cast in the 2018 midterms. So that's a big, big pool of potential political power. And then the third thing I'll say about Arizona is this is a state where the presidential election was decided by a little more than 10,000 votes. I mean, that's nothing. That is nothing. I mean, a butterfly flaps its wings in the Sonoran Desert, and that eventually can impact more than 10,000 votes. I mean, 10,000 votes is nothing in politics. And so the fact that we've identified 101,000, environmental drop off voters in the state is a huge, huge opportunity for us. Arizona has tons of local elections this winter and spring, they then have their primary, they then often have special elections. And so we're going to get multiple bites at the apple, multiple opportunities to talk to these environmental drop off voters before November comes around. And so it is such a great opportunity for us, if we can only get five or 10% of these drop off voters to show up. That's the margin of the entire presidential election in Arizona. That can be a big, big deal.

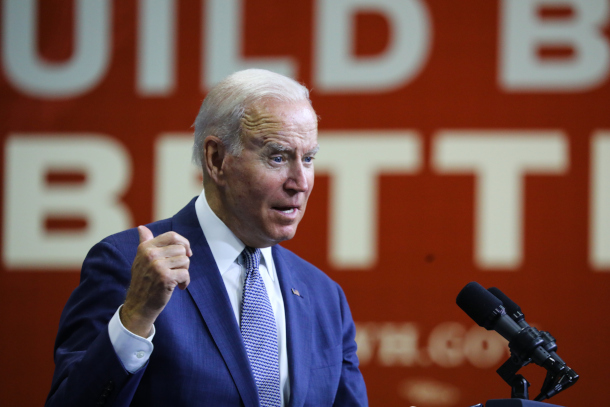

After Congress failed to pass the environment-forward Build Back Better bill, many environmental activists say they feel discouraged. (Photo: Edwin J. Torres, New Jersey Governor’s office, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Nathaniel, to what extent are climate and environmental voters deflated or upset by, say, the major losses like the Build Back Better Plan that was supposed to deliver on the climate in such a big way?

STINNETT: Well, there's no doubt that the underlying premise of your question, Steve is true. Climate voters are demanding more. And a recent political poll even said that 80% of left-leaning voters think Biden has done too little to combat climate change. But if we truly want more climate leadership, we need to be honest with ourselves about why we're not getting it right now. And the hard truth is that the environmental movement simply doesn't have enough political power right now to pressure senators and governors and mayors and yes, presidents into leading on climate. And it's kind of wishful thinking to assume that politicians will ever combat climate change unless voters start forcing them to. I mean, these are political animals, and the only thing that moves politicians is political power. So we need more of it. Even when we're frustrated by politics, we need to get stronger and exercise more voting power on election day, not less, because ultimately, the climate crisis doesn't care whether we're conflicted or unhappy on election day. But if we stay home, and environmentalists don't vote then things are going to get a whole lot worse really quickly.

CURWOOD: So how do you get these people to vote?

Nathaniel Stinnett serves as Founder and Executive Director of the Environmental Voter Project. (Photo: Courtesy of the Environmental Voter Project)

STINNETT: Well, usually, oddly enough, we don't treat them as rational beings, we don't try to try to rationally convince them of the importance of their one vote. Usually, we treat them as social beings, we try to figure out what societal norms they buy into, who they want to be. And so we use things like peer pressure. We'll send them a message and let them know how many of their neighbors voted last time there was an election, things like that. And then in particular, for these drop-off voters and this report that we just released, Steve, we can use a really, really special technique with these drop-off voters, a phenomenon known as loss aversion, which is the idea that people usually fear losing something more than they appreciate gaining it. So what do I mean by that in this instance? Well, our messaging thanks these environmentalists for voting in 2020, and then says stuff like: don't break your streak! Don't mess up your new good voting record! And that way, instead of making voting in the midterm seemed like a new hard step that they need to take, we're characterizing it as a way to retain or not lose an already existing part of their personality, which is being a voter. And that works really, really well. Taking advantage of that loss aversion can dramatically boost turnout, because we're making voting seem like something they've already got. And it's important not to lose it.

CURWOOD: Nathaniel Stinnett is the founder and executive director of the Environmental Voter Project. Nathaniel, thanks so much for taking your time with us today.

STINNETT: Thank you so much for having me, Steve. I always really enjoy it.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Environmental Voter Project

- Read the Environmental Voter Project’s report

- Listen to LOE’s most recent segment with Nathaniel Stinnett about 2021’s Georgia run-off elections

[MUSIC: Michael Oakland, “Samba De Gaia” on Witness, by Michael Oakland, TTM/Outermost]

BASCOMB: Coming up – In the face of the pandemic, visits to National Parks have increased dramatically. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michael Oakland, “Samba De Gaia” on Witness, by Michael Oakland, TTM/Outermost]

Beyond the Headlines

A Koala grips the sides of a eucalyptus tree. Fires and urban development projects have led to widespread destruction of eucalyptus, which koalas rely on for both food and shelter. (Source: Flyinglester, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

And on the line from Atlanta, Georgia is our favorite editor with Environmental Health News and DailyClimate.org. It's Peter Dykstra, and he's here to take us behind the headlines. Hi there. Peter, what do you got for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. And I should say first, that all of the EHN editors are my favorite editors, including my boss. But we'll start out with some big news from Australia. The government there has declared koalas to be endangered. This is primarily due to habitat loss and deforestation. They estimate that 30% are already lost, with extinction a possibility by as soon as the year 2050.

CURWOOD: No, no, no, these are such adorable creatures, you know, that little button nose and they kind of look like a teddy bear. But are they bears, Peter?

DYKSTRA: No, they're marsupials, and they do look adorable, but they would tear your nose off if you got a little too close on the huggy side. Marsupials like the koala, are most known to exist in Australia, but they do exist in other places. And even here in the US, where we have our own homegrown marsupial, the possum. Anytime any species is lost, it's a tragedy. Anytime any species is endangered it's a tragedy. We tend to pay more attention, right or wrong, when an emblematic, charismatic animal like the koala is endangered.

CURWOOD: But what went wrong? Why are they disappearing in Australia? Since it is so important to the identity of Australia, the government and the people will be taking care of them.

DYKSTRA: The government has put up millions of dollars in an effort to save them or actually to save their habitat. In eastern Australia, the most heavily populated part of the country along the coast is being lost, in some cases to suburbs. In a lot of cases to logging and deforestation. Some of the worst wildfires in Australia have happened in that same area. And everything is coming down where koalas live and unfortunately, are vanishing in much greater numbers than they can sustain.

CURWOOD: So sorry to hear that. Tell me you have some good news this week for us, Peter, please.

DYKSTRA: Ah, yeah, this is good news. If you like clean energy. One of the biggest utilities in the United States, Duke Energy, based in the Carolinas is pledging to quit coal, that's a lot of coal plants by 2035 and be carbon neutral by the year 2050. They say they've already cut 44% of what they emitted in carbon back in the year 2005. So in a sense, they're well underway. But it's an encouraging sign, if it's a promise that can be kept.

One of Duke Energy’s cliffside coal plants funnels emissions into the air. The power company says that it has already cut 44% of what it emitted in carbon since 2005. (Source: Rainforest Action Network, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: But how many coal fired power plants do they have, anyway, if that's what they're saying they're gonna do?

DYKSTRA: They're actually just shutting down a few. But one thing about the Duke Power power plants is that one of the biggest spills from a coal waste lagoon happened at a Duke plant several years ago. It poisoned parts of the Dan River. It's still being litigated and cleaned up today.

CURWOOD: Yeah, you don't want to be downstream from one of those coal fly ash impoundments. It's pretty toxic stuff.

DYKSTRA: It is. But what's not toxic, you don't want to have a wind spill or a solar spill because there's no such thing. Wind and solar are a big part of what Duke Energy sees as its future, and also converting its existing natural gas plants to what is now experimental, but they're looking toward hydrogen to be a source of public electricity in the future.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. Well, that is some good news. Let's take a look back in history and tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: February 16, 1937. There was a chemist who worked for the DuPont Company named Wallace Hume Carruthers. He and DuPont were awarded a patent for nylon. It's a landmark event in the manufacture of synthetic products. And in a way, it's a herald to the oncoming of synthetics and the plastic industry in general.

A worker fits nylon stockings over mannequin legs. DuPont’s nylon patent, awarded in 1937, democratized stockings for women at a high environmental cost. (Source: Public Record Office Victoria, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: When I hear the word nylon, I think of my mother and grandmother, the stockings they wore.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, and two years after that 1937 patent, nylon stockings went on sale first in a department store, and DuPont's hometown, Wilmington, Delaware. By the time World War Two came around, they had become a fad and a big deal. And also part of the war effort because nylon began to be used in the manufacture of parachutes and other military tools. And now we're dealing with them not as just a part of our lives, but a part of our environment.

CURWOOD: Yeah, indeed. Too bad because you know what, those nylon stockings democratized stockings for women because back in the day, you had to buy silk for a stocking. And not a lot of people could afford this.

DYKSTRA: No and not a lot of worms could afford to make the amount of silk that humans would want to buy .

CURWOOD: Alright Peter, Thank you. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news that's EHN.org and Dailyclimate.org We'll talk again real soon

DYKSTRA: Okay Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website, that's loe.org.

Related links:

- The New York Times | “Australia Declares Koalas an Endangered Species”

- Utility Dive | “On Track to Eliminate Coal by 2035, Duke Expands Net Zero Carbon Goal to Include Indirect Emissions”

- Learn more about the nylon patent

[MUSIC: Orchestra Baobab, “Ndongoy Daara” on Specialist in All Styles, by Orchestra Baobab, World Circuit/Nonesuch]

Love Overwhelms National Parks

Parking lots and roads in famous national parks are more congested than ever, as many families seek outdoor vacation alternatives amid the ongoing pandemic. (Photo: Walt Richardson for NPCA)

BASCOMB: The late E.O. Wilson coined the term biophilia, that is the notion that human beings have an innate instinct and need to connect with nature. And scientific research shows that spending time in nature is good for our mental health. Samantha Freeman at the University of Cambridge recently conducted a study looking at how the amount of time children spent in nature during the COVID lockdown affected their mental health. She looked at 3 to year 7 year olds in the UK and found those who spent less time in nature during the initial lockdown had more behavioral and emotional problems like feelings of sadness, isolation and worry. Two thirds of the children studied actually spent more time in nature during lockdown and had improved behavior as reported by the parents. Here’s Samantha Freeman.

FREEMAN: It would seem like time and nature is a low cost way of supporting Child Mental Health. And so I think parents can be comforted by the fact that it seems like spending time outside engaging in a variety of different activities, whether that's digging in the garden, going for a walk, eating breakfast outside, all of these things seem to be linked to improved well being, and there don't seem to be a whole lot of downside to it. So while we can't be as prescriptive as, as maybe parents would like, it does seem that the takeaway message is spending time outside is beneficial to well being and is really a low cost way of, of kind of accessing mental health benefits.

BASCOMB: And Samantha says this type of mental health improvement is well documented for adults so it shouldn’t come as a surprise to have similar findings in children.

FREEMAN: There's a lot that we know about time in nature for adults. So we know things like noticing nature, even as simple as that viewing natural landscapes for adults can have a lot of benefits for stress reduction, improvements for depression, less anxiety, these types of things. So lots of research on adults, less research on children, but still some pointing towards similar things, reductions in stress and anxiety, less hyperactivity, these types of things.

BASCOMB: Samantha Freeman’s work with the University of Cambridge focused on children in the UK but here in the US plenty of people are also seeking solace in nature amid the social restrictions of COVID. Visitation rates to many of our national parks have gone up dramatically since the pandemic began. Last year, 40 percent more people visited Yellowstone and 45 percent more went to Canyonland National Park. In 2020 the bipartisan Great American Outdoors Act allocated 9.5 billion dollars for maintenance backlogs in our National Parks and public lands. That sounds like a lot of money but the parks have been chronically underfunded for decades and much more is needed, especially with the huge increase in visitors. Some parks have become so popular that visitors must make a reservation in advance, not unlike getting a table at a popular restaurant. For more I’m joined now by Kristen Brengel, Senior Vice President of Government Affairs for the National Parks Conservation Association. Welcome to Living on Earth!

BRENGEL: Thanks for having me.

Due to overcrowding, visitors to popular national parks have been met with requests to “come back later,” pushing some travelers to change plans at the last minute. (Photo: Walt Richardson for NPCA)

BASCOMB: So what does this exponential increase in park visitation actually look like? I mean, are we talking about lines to see bison in Yellowstone or to get a look at the Grand Canyon?

BRENGEL: Generally speaking, the parks have been understaffed for this entire pandemic. And so, you couple that understaffing with more people going to visit parks. That's where you start to really see so many issues in terms of moving people around a park. One example that I can give you is in Arches National Park in Utah. Everyone wants to go see Delicate Arch and get their picture taken underneath. I did it too. And arches is a wilderness park. It's an in and out road for the most part. So what happened in Arches for the past few years is people simply could not get in. So you are greeted mostly by a sign that said, "Come back in three hours”. And so folks were sort of being turned away at the entrance early in the morning, and seeking out other places to potentially go for the day. And park staff who were once doing interpretation in the park, were directing traffic instead. And so, this isn't the park experience that we want people to have. And it pains everyone, whether it's the Park Service staff or advocates like me, when you hear people getting turned away at an entrance because the park simply can't handle the volume of people.

Well-known national park trails have recently been overloaded by visitors, as many seek outdoor alternatives during the pandemic. (Photo: Walt Richardson for NPCA)

BASCOMB: And from what I understand this increase in park visitation and all of the, you know, protocols that have to go along with it hasn't been met with a commensurate increase in funding for the parks. What's going on there?

BRENGEL: Well, part of it is that Congress put a cap on spending for many, many years. And so really, very little within the federal government got increases over several years. Now that that period of time and those funding caps have been lifted, we've seen some small increases in park funding. This year, we're hoping the Park Service gets a pretty decent increase. Congress has really focused on park funding the last few years. And so we're hoping that they seize the moment.

BASCOMB: Well, what could be accomplished with more money for the parks?

Visitation to popular spots like Delicate Arch in Arches National Park in Utah has skyrocketed in recent years. (Photo: Walt Richardson for NPCA)

BRENGEL: Many things. The Park Service has been well understaffed for a pretty long time, especially in the last 10 years, it's gone down about 17%. We simply don't have enough historians that are working at the Park Service, enough experts. When it comes to resource protection, not enough wildlife biologists. Then we have to bring the parks into the 21st century. So one of the things that we want to focus on as an advocacy group is making sure that interpretation is really well updated, that people can access information on their phones and in other ways, and that the museum experience that you have in a park is improved and updated. And the stories have evolved. I always like to use Yorktown in Virginia as an example. The last time I was there, which was several years ago, they had a reel to reel movie that you watched in the Visitor Center. And it reminded me of being an elementary school child in the 80s. That needs to be updated. There's no question. And there are such great stories to tell about Yorktown. And that's a place where if you watched Hamilton, he was there during the Battle of Yorktown. All of that can be updated and told in a way that can really grab the public and educate folks about our history. And so there's a lot of work to be done in the parks in terms of where they could put funding right now, if if they had it.

BASCOMB: So what about the great outdoors act that passed in Congress a couple years ago? How does that impact the parks?

Many people wishing to experience the fantastical landscapes of US national parks have been greeted by swarms of tourists in recent years. (Photo: Walt Richardson for NPCA)

BRENGEL: Almost two years ago now, Congress passed a bill called the Great American Outdoors Act in the most bipartisan way you can possibly imagine, in this day and age having over 300 House members on the same bill, which goes to show how much everyone loves their national parks. And what we've seen already in terms of the implementation of the bill are, you know, the towpath that Cuyahoga in Ohio is getting fixed. The Loop Road at Yellowstone is getting fixed. The water system at Grand Canyon is getting fixed. So all these amazing projects that have just sat there, but could have ruined these parks and the visitor experience for these parks are now getting fixed. So this is sort of an inspirational moment for the country. We're getting our parks fixed, they're going to be in better condition. We're going to make sure people have a great experience when they go there. And hopefully, and one of the most important things I was hoping to get out of the Great American Outdoors Act is some of these historic sites where the roofs and the brickwork and some of the amazing places that have just broken down over time are going to finally get fixed, so people can access them and enjoy them, maybe for the first time in their lives.

BASCOMB: It certainly sounds like there's a backlog of work to be done. There's an increased visitation rate. And at the same time, we know that climate change is really taking a toll on many of our national parks. Can you talk a bit about the challenges that you're seeing there with climate change?

The National Park Service, which has struggled to secure adequate funding and staffing for decades, is struggling to deal with a recent surge in visitors. (Photo: Takashi M., Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BRENGEL: Climate change has hit the parks really hard. In fact, parks are warming twice as fast as the rest of the country. And that's because parks are typically the highest mountains, the beaches. They are seeing dramatic changes right now because of climate change, whether it's beach erosion, storm surges in West Virginia at Harpers Ferry where there's incredible flooding, drought at Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the Colorado River is not doing well. And then we see fires, wildfires. We see glaciers melting. We know that Joshua trees are dying faster in Joshua Tree National Park. The effects of climate change are real. We don't have enough places protected right now to maintain nature in the state that we see it today.

BASCOMB: Yeah, well, there are a lot of challenges here that we've been talking about. But you know, the national parks, they've been called, "America's Best Idea," right? I mean, I think everybody loves the fact that they're there. Even if we don't get to visit them, just knowing that they're there-- I don't know is comforting, at least to me. That's how I've always kind of felt

BRENGEL: Absolutely.

The National Park Service is working hard to both protect fragile habitats and preserve outdoor experiences for visitors, all while larger crowds flock to “bucket-list” spots such as Glacier National Park. (Photo: Cody Wellons, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Looking into the future, though, you know, 20, 30, 50 years even. What do you see, as an ideal national park system? What would that look like to you?

BRENGEL: Such a great question. We love so many national parks because you can have these unbelievable experiences in nature. You can see a geyser go off, you can see a herd of bison. In the case of-- I was just in Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico, you can go see a kiva, climb the ladders, see cliff dwellings, and really experienced these things that are once in a lifetime. So part of it, right, is to protect these places very, very well. So people can continue to have those incredible experiences. Then you have the side of updating the interpretation, the storytelling, make sure people really see themselves in the national parks, whether you're a Native American, a woman, an African American, telling the whole range of stories. I was up a few years ago at Paul Revere's house in Boston. The young interpretive staff there told the story of Paul Revere's wife, which we never hear. We never hear about this incredible woman who literally held down the fort while he was out telling everyone else the British were coming. And so, how do we make sure that we all can see ourselves in these places? And that's what I think our hope is, for the future of the National Parks is that we have sites that represent all of us in the country. Right now, we have so few sites that even just represent women, women's history.

Kristen Brengel climbing the ladders at Bandelier National Monument. (Photo: Kristen Brengel)

And so, but we have so many sites that tell the story of our presidents. And so I don't want to get rid of the ones with the presidents. Those are really important too. But we how many sites can either enhance their interpretation to tell more stories about women or more sites to celebrate women's history? It took about 12 years, and a lot of hard work, to designate the two sites for Harriet Tubman. That is way too long. You know, we need to make sure there are more sites that just tell stories about all of us and that our kids can see themselves in all of these places. I think the parks of the future are those that really bring all of America together.

BASCOMB: Well, I certainly hope so. Kristen Brengel is the Senior Vice President of Government Affairs for the National Parks Conservation Association. Kristin, thank you so much for taking this time with us today.

BRENGEL: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- National Parks Conservation Association | “July 2021 Congressional testimony on visitation by NPCA’s Government Affairs lead Kristen Brengel”

- National Parks Conservation Association | “Yosemite Valley to Herself, After a Wait”

- Learn more about the United States’ National Parks at Recreation.gov

- Click here to visit the National Park Service website

[MUSIC: Richard Smith, “The Entertainer” live for Nashville Tune Stream, by Scott Joplin/arr. Richard Smith]

CURWOOD: Coming up – How the lush farmlands bought by freed slaves along the Lower Mississippi became a hellscape once the petrochemical industry moved in. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mario Grigorov, “Ice Hotel (piano version” on Paris to Cuba, by Mario Grigorov, Warm & Genuine Records]

Black History on the Mississippi

Founder of RISE St. James and 2021 Goldman Environmental Prize winner Sharon Lavigne speaks at the first annual African American Celebration at the gravesite of enslaved ancestors at the Buena Vista Cemetery. The land was purchased by Formosa for a proposed petrochemical complex. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

As part of black history month we’re going consider the story of people who came up from the sugar plantations of slavery and built thriving communities but then became bound by deadly pollution a century later. An 85 mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans has been dubbed Cancer Alley, thanks to the petrochemical industry that began building there in the 1960’s. Today over 150 petrochemical facilities pollute the region’s air, land and water, leading to high rates of cancer, respiratory illness, and mental health challenges. Sharon Lavigne lives on land bought by her grandfather in St James Parish Louisiana and when she saw her friends and neighbors getting sick and dying she retired as a special education teacher to devote herself full time to anti-pollution advocacy. She founded RISE Saint James, an environmental justice group working to stop more toxic chemical plants from moving into her community. Her organization and others sued Formosa, a Taiwanese company that wants to build an ethane cracking plant for producing plastic nearby. The litigation prompted the Army Corps of Engineers and the courts to halt construction and require an updated environmental impact statement of the proposed facility. For her work Sharon Lavigne was awarded the 2021 Goldman Environmental Prize for North America and she joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth Sharon!

LAVIGNE: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So Sharon, how are you doing? Last time we talked, it was right after Hurricane Ida had struck your neighborhood and the surrounding region?

LAVIGNE: Well, I'm doing a little bit better because I'm living in a travel trailer at night and in the morning, I come in my home to sit by my kitchen table to get on my laptop. So that's a little bit better. And the roof on my house is completed. Now we trying to find a contractor to do the inside of the house.

CURWOOD: Oh my goodness, trying to find a contractor is like trying to find a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow I think.

LAVIGNE: That's right. It's hard to find a contractor at this time because so many homes were destroyed. So it's hard to find one.

Indeed they are: Louisiana Chemical Plants Are Thriving Off of Slavery - The Atlantic @theccr @risestjames @labucketbrigade https://t.co/yIpOG6QYPh

— Pam Spees (@PamSpees) May 7, 2021

CURWOOD: So you've lived in the St. James Parish, what your whole life and generations before you? What was it like there as a kid?

LAVIGNE: Oh, in St. James, it was wonderful. It was living the American dream because at that time, we had clean water, we had clean air, we plant gardens, the trees had pecans, plum trees, persimmon trees, orange trees, lemon trees. We had everything. We had gardens, we had our livestock, we didn't have to buy any meats from the store. My daddy would kill hogs, chickens, cows. And it was about the life of Riley, it was so wonderful back then.

CURWOOD: And today, what are things like there?

LAVIGNE: Today, it's like living almost in a cesspool, close to it. We have chemical industry that came in, in the late 60s and after that more and more started to come and with all of these combined it made the pollution so powerful. It made it where whenever we walk outside you could smell a foul odor and we can't drink the water anymore because the water is polluted, and we can't do a productive garden anymore because the soil is polluted. So it's a whole different world now. We trying to live in this filth but not knowing at the time when it first came in it would be like this. Everybody thought it was wonderful that industry came in but now it's not wonderful.

CURWOOD: That's right, when when you're were young, St. James Parish is right along the Mississippi there so there's really rich bottom land that you could grow anything inn, right?

LAVIGNE: It was at one time it was, yes.

CURWOOD: And people used to grow sugar cane in that region?

LAVIGNE: That's right, we still do. But a lot of the industries bought out the sugarcane farmers land. And now we have the industry in place of the sugar cane in some of the areas.

CURWOOD: Now your family participated in the civil rights movement in your your father did do some sugarcane farming. Tell me about that history.

LAVIGNE: Well, as long as I can remember, we had sugarcane. My daddy harvested the sugarcane. And back in the 60s, when he tried to integrate the school in St. James on the West Bank that's when the local factories stopped taking his sugarcane because of the work he was doing. So you have to go to another parish to have them to pick up his sugar cane. The local people they denied him, they denied his sugar cane, his business.

CURWOOD: Because he was doing civil rights actions?

LAVIGNE: Action. That's right. That's right.

A tractor in a sugarcane field in Louisiana. (Photo: Faungg, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now you received an award for fighting against the plants there in your neighborhood. There was a big plastics plant by Formosa. There was another one that's proposed. So far what are the results of your opposition to these plants?

LAVIGNE: Well Formosa, it's on hold right now. The Army Corps of Engineer has to do a complete EIS, environmental impact statement and that's going to take about a year or two. So that's the hold up right now. But the word that I heard is, they are trying to go to another parish. And I also heard that they are going to buy land from another industry that's in Plaquemien and tag along next to that industry. That same industry that they're going to tag along to, that industry tried to come in Convent, Louisiana, back in the 1990s and 80s and the people ran them away. I was a little girl back then and my dad and my cousin Emelda West, they would talk about it in the kitchen when I would pass through the kitchen and they would talk about how this plant wants to come into Convent. And cause an email to said she's not going to let it come and it didn't come and she fought against that.

CURWOOD: And Convent Louisiana is in which parish?

LAVIGNE: It's in St. James, but it's on the East Bank.

CURWOOD: So your activism along with so many other people in the in the communities along cancer alley, certainly it doesn't go unnoticed. But it's a huge fight. I mean, these are multi billion dollar corporations that spew these toxic contaminants and they are allowed to exist so close to the homes of all these people. What inspires you to keep going? Why is this important?

LAVIGNE: It's important because if we don't fight, we will die. This place is so polluted and so many people have cancer, so many people have already died from cancer, so if we don't fight to keep it away from here, we will die. That's the bottom line- there's no ifs, ands or buts. We will die, because we already have twelve in a 10 mile radius in the 5th district. We had nine in the fourth district. I think we have seven now. And we have a grand total of data that shoots across the river straight to my house. And one of the plants have particulate matter (PM) 2.5. I didn't even know anything about that until after I started doing this work. But look how many years I passed by that plant and they're polluting us. So whatever is in my body is coming from these industries over a period of time. It just didn't happen overnight. So if Formosa comes in here, we will not live because they will triple the emissions in the fifth district and it will double throughout the parish. And I live two miles from where this plant wants to be built, only two miles. And the church is one mile and a school is one mile. So no, St. James, 5th district is full and we can't take anymore.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, there was an old cemetery an old slave cemetery.

LAVIGNE: Yes, yes, it's there. And one thing I didn't like about Formosa, we had to bring it to the parish council about the grave site, they kept it a secret for 17 months. Then when we found out about it we brought it to the parish council, they didn't do anything about it, he didn't even care it looked like. They didn't care that we found a gravesite or if they desecrate the grave. They didn't even respond to us. So we stopped that, because they were going to build that plant on top of the grave sites. But we expose them, so they're not gonna build at all. But that's our ancestors in those graves and it's more than one great site. And we went out there, and we had an action and we did a Juneteenth out there and we did a celebration with the Bishop of Baton Rouge for All Saints. And we did a black history program out there. And trust me, you can feel the presence of our ancestors. It's like they were rejoicing that we didn't forget about them. I felt it. I don't know about other people but it looked like they were so glad that we were out there at the site rejoicing. And I don't know what other people but I felt the spirit, I really did. And it made me so happy. I wanted to cry, I felt so good. It was just that powerful.

CURWOOD: To what extent are they guiding you now?

LAVIGNE: The ancestors?

CURWOOD: Yeah.

Community members at RISE St. James’ first annual African American Celebration at the Buena Vista Cemetery, the gravesite of enslaved ancestors. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

LAVIGNE: Oh, their spirit, they’re telling me to fight. They are telling me to fight and you know what I want to do? I want RISE to get some funding so we can buy the land and preserve those grave sites. And they’re going to be even more happy when they know we care about them. Because you see they don't have a headstone or anything, they just have markers. The archaeologists showed us the markers and we can put some kind of symbol or something there, you know, to let everybody know that that's the gravesites of our ancestors. So that's what I would like to do.

CURWOOD: Now, during the recent presidential campaign, President Biden came to this part of the Lower Mississippi. It's called cancer alley because of what there's more than 100 petrochemical plants, between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. Right. And President Biden promised to put environmental justice at the center of his mandate. So what have you seen in the way of any changes so far in the community when it comes to addressing all that overwhelming chemical pollution from those plants?

LAVIGNE: I don't see hardly any improvement from the time he ran for office until now. That was why we had a meeting with the White House last week. Because we talked to them, to ask them why is he leaving us out. Because he campaigned in about cancer alley. He campaigned about a whole lot of things about the environment and he's not helping us. He keeping promises but other things that he said but he's not keeping his promise with us with cancer alley and specially with St. James Parish, because he mentioned St. James Parish in this campaign, and he haven’t come back to see about us. He haven't reached out to us. I know he's busy with COVID and other things, but I don't think he should put us on the back burner. I think he should let us see something. The EPA said they was gonna put some monitors in the area, you know some air monitors. So that's in the making right now. But we don't see them putting a halt to our deaths over here in cancer alley. That's what we don't see. We are still dying, people are still dying.

CURWOOD: So the air monitors don't help in your view?

LAVIGNE: The air monitors would help if that's the way they want us to prove to them that we are being poisoned. That will be a big help but we don't have them yet in St. James.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think more proof is needed that these plants are killing people?

LAVIGNE: Blood. Test blood it's in the blood, it's in the blood. Trust me, it's in the blood. I was diagnosed with lead in my body. I was diagnosed with aluminum in my body. Then in 2016, I was diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis, I researched it, and they say it came from industrial pollutants. How much more do they need? They need all of us to die to have proof? No, it's in the blood. Tell him to do a blood study, a health study. The governor said he would do a health study. When I asked him to stop Formosa the answer he gave me was he would do a health study. We haven't gotten that yet. They just tell you something just to throw you off.

Part of the Dow petrochemical industry complex on the west bank of the Mississippi in Iberville Parish. (Photo: Louisiana Sea Grant)

CURWOOD: We've been trying to get in touch with the EPA administrator about what's going to happen with these monitors. He briefly came there and there were a lot of photographs, just wondering how much substance there was to his appearance.

LAVIGNE: Oh, it was it was a plus, because nobody else came to visit us or see about us. At least he came and he walked around with us. And we showed him the sights, we showed him the chemical plants. And we showed him the oil storage tanks and how close they were to the people's homes. So that was something that no one did before. And especially coming to St. James to ask for us to speak with us that was wonderful. And the thing that that I like about him, he didn't want to speak to the politicians, he wants to speak to the citizens. We told him the truth, we didn’t candy coat anything. We told him how the politicians are voting for all of these industries to come in here and the people are sick and they are dying.

CURWOOD: So as we mentioned, President Biden campaigned in the cancer alley region and promised to do something about it. What do you now expect from the Biden administration?

LAVIGNE: I expect them to keep their word. I really do. They said we're going to help us. We don't have any help yet. The people living here and breathing the air, they want him to put a halt to all these industries that are poisoning us. That's what we want. I would like to speak to President Biden in person and tell him how I feel. Because Formosa is not coming here. I know they will leave. They're not coming two miles from me and I'm not leaving. I'm staying right here and if they want to go somewhere, they better go somewhere else. But I wouldn't advise the people and let these people come in. These people will poison them, they will poison the community. The same way they kill the fish in Point Comfort, Texas, the bay was all destroyed and Diane Wilson is fighting that fight. And the people in Taiwan don't want them there. So what they think they could come over here and just poison us? I don't think so. No way. No way. No way darling I could tell you that.

CURWOOD: Keep on keeping on Sharon Lavigne, thank you.

LAVIGNE: I will try. Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: Oh, by the way, is there any music? Are there any songs or tunes or anything that you associate yourself with?

LAVIGNE: Yes. On our first march, we had a march on November 3, 2018. And when the lady was interviewing me I said “Formosa this needs to stop, you will not come here”. And I said “victory is mine” and I started singing. That's our theme song, Victory is Mine. And so whenever Formosa throw in the towel, that's going to be our song.

CURWOOD: Can I hear it now?

LAVIGNE: Oh, alright. Victory is mine, victory is mine. Victory today is mine I told Formosa get thee behind, victory today is mine. Joy is mine, joy is mine, joy today is mine. I told Formosa get thee behind. Victory today is mine!

[MUSIC: Dorothy Norwood, “Victory Is Mine” on The Gospel According To Malaco, Malaco Records]

CURWOOD: Sharon Lavigne is the founder of the environmental justice group Rise. St. James. Thanks so much, Sharon, for taking the time with us today and we'll be getting back to you to see how the Biden administration deals with your concerns over time.

LAVIGNE: Okay, thank you.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “US to Hold Surprise Plant Inspections Targeting Pollution in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley”

- Learn more about RISE St. James

- IOP Science | “Air Pollution is Linked to Higher Cancer Rates Among Black or Impoverished Communities in Louisiana”

- Listen to Living on Earth’s story about the destruction brought by Hurricane Ida to St. James Parish

[MUSIC: Dorothy Norwood, “Victory Is Mine” on The Gospel According To Malaco, Malaco Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Gabriella Diplan, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth