April 29, 2022

Air Date: April 29, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

How Purpose Trusts Can Support Corporate Sustainability

View the page for this story

For many corporations it’s all about the bottom line, and that can come at the expense of the environment, employees and consumers alike. But there’s another way to structure a for-profit company for a higher purpose. Sarah Joannides, the managing director of Alternative Ownership Advisors, joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about how perpetual purpose trusts can help companies uphold core values like sustainability. (09:21)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

On this week's trip beyond the headlines, Host Jenni Doering chats with Environmental Health News' Weekend Editor Peter Dykstra about two moves from the Biden Administration: one, to inventory and protect old growth forests, and two, a $6 billion bailout for nuclear power plants. And then, from the history books, the two take a look at the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986. (04:58)

Electric Vehicle Sales Stuck in the Slow Lane

View the page for this story

Electric vehicles are key to decarbonizing the transportation sector, but most cars sold in the U.S. are still gas-powered. Even in Massachusetts, where a climate law requires net zero emissions by 2050, EV numbers are nowhere near where they need to be. Boston Globe Reporter Sabrina Shankman joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about what’s keeping electric vehicles in the slow lane and how to speed the transition. (08:27)

150-Year-Old Law Robs Public Lands Riches

View the page for this story

Extraction of minerals on U.S. public lands is based on a 150-year-old law that doesn’t require royalty payments or adequate protection for the environment and local people. Reporter Jim Robbins talks with Host Bobby Bascomb about the concerns around a proposed lithium mine in Nevada and efforts to reform the antiquated mining law. (08:01)

200 New Freshwater Fish Species Discovered

View the page for this story

More than 200 new species of freshwater fish were discovered worldwide in 2021, including a blind eel found in Mumbai and a fish dubbed the Wolverine pleco for its hidden spines. Harmony Patricio is conservation program manager at Shoal, which compiled the report and she joins Host Bobby Bascomb for details. (07:49)

An Interview with the Ocean

View the page for this story

As we close out Poetry Month, we share the timeless poem “I Go Down to the Shore” read by the late Mary Oliver, and a sound rich performance of a creative piece it inspired. Author Kate Horowitz wrote “An Interview with the Ocean” and joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to bring it to the airwaves. (08:21)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220429 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Sarah Joannides, Harmony Patricio, Jim Robbins, Sabrina Shankman

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Kate Horowitz.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Ramping up electric vehicle sales in a way that is affordable for more consumers.

SHANKMAN: If everybody just switches over from gas vehicles to EVs, we haven't really solved the problem; we also have to electrify transit, get better bike lanes, get people on bikes, E-bikes. But there will still be a lot of drivers, and so for that it has to be equitable. And we have to find a way to get lower and moderate income people, you know, make it in reach for them as well.

BASCOMB: Also, a purpose trust allows companies to serve more than shareholders.

JOANNIDES: Employees get additional profit sharing. Farmers get additional programs and grants that they can have access to as do the customers and the community allies. So there’s a way that each of them can participate in the economic benefit in a way that is equitable across all stakeholders.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

How Purpose Trusts Can Support Corporate Sustainability

One of the stipulations for Organically Grown Company’s perpetual purpose trust involves supporting local organic farmers who are often squeezed out of a heavily consolidated agricultural supply chain. (Photo: Courtesy of Organically Grown Company)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

And I’m Jenni Doering.

For many corporations it’s all about the bottom line, and that can come at the expense of the environment, employees and consumers alike. But there is another way to structure a for-profit company for a higher purpose. In 2018, Organically Grown Company, or OGC, a wholesale distributor of organic produce, adopted a unique structure that enshrines its goal to transform and sustain a healthy and fair food system. It uses a perpetual purpose trust, a type of corporate entity that exists to ensure the company will stay true to its mission in perpetuity. Sarah Joannides is the managing director of the consulting firm Alternative Ownership Advisors, an offshoot of Organically Grown Company. Sarah, welcome to Living on Earth.

JOANNIDES: Thanks so much for having me.

DOERING: So first, just what is a perpetual purpose trust? And why is it a useful framework for businesses that want to help care for the environment?

JOANNIDES: So a purpose trust, you can think of it like a benevolent owner, they are simply or it is simply an entity that can hold a company in perpetuity for as long as the company is viable. So typically, you have an owner, or owners that have the control of the company, and they have the right to take profits, and they can sell the company whenever they want to. So when you instead, think about trust ownership, what you're doing is you're putting the common stock of the company, and you're putting it into a mechanism that holds it. It's there to act as a governor of the company to ensure that the company remains focused on its purpose. So generally, governors of a company have a profit motive, because the decisions they make impact how much they will earn, at the end. With a trust, the stewards of the trust can make decisions based on what's right for the health of the business, and the health of the stakeholder community. Again, the difference here is the beneficiary of a purpose trust is the purpose of the organization.

DOERING: And what are some examples of this purpose that the trust would enable the company to pursue?

JOANNIDES: Right. So we see some people or some companies that establish a trust for the benefit of employees, other people focus on elements of their mission that are very important to them. So an example we use a lot of the time, which is actually our parent company, Organically Grown Company. And it's a company that's been focused on supporting organic agriculture and sustainable food systems for over 40 years. And the trust is there to enable the company in supporting sustainable agriculture and aligned businesses that support organic agriculture and sustainable food systems.

DOERING: And these are for profit companies. So when they do make a profit, where does that profit go exactly?

JOANNIDES: Good question. So generally, what we see is that the owners set up a framework for how they're going to distribute profits at the end of the year. So certainly, you need to have money set aside for capital expenditures to meet all of your obligations. But what's leftover, in this case, you design a framework that says this is how we're going to distribute profits, based on who we determine or the stakeholders of this company. With OGC they have what they call a cash flow waterfall. And so each says that after all of those obligations have been met, whatever's leftover is divided out in a manner that is fairly equal across the rest of the stakeholders. Employees get additional profit sharing, farmers get additional programs and grants that they can have access to, as do the customers and the community allies. So there's a way that each of them can participate in the economic benefit in a way that is equitable across all stakeholders.

DOERING: What is the problem with conventional business structures? Why do we need alternative models like the perpetual purpose trust?

JOANNIDES: Well, I think, you know, many folks would agree that there's been a lot of unintended consequences with capitalism, with money being highly concentrated in the hands of few verses, more broadly shared prosperity. And part of that has to do with the ownership dynamic, where owners have the rights to the control of the company and all of the profits of the company. And while many, many companies act very responsibly from a corporate social responsibility standpoint, it's certainly not required of them. And so over time, as you have smaller companies that are running in a very mission driven way, being bought and consolidated into larger companies that are of a traditional shareholder primacy focus, you tend to have that control of the focus being on driving profits, versus on really thinking about the purpose. Especially in the situation where business owners, they are transitioning their business, they're getting ready to retire or they're ready to move on to something else. But they feel that there's a reason why the business should continue to exist because of the good it does in the world, through commerce but in the mission that it has.

DOERING: So walk me through the journey of your parent company, organically grown company, as it adopted this new trust structure in 2018 I think. Why did it seem like a good fit?

JOANNIDES: Yeah, well, they were certainly at an interesting crossroads. They were a company that had iterated their ownership structure many times, actually, they started as a nonprofit. Just a bunch of guys kind of in a garage.

DOERING: The Wikipedia page says a bunch of hippies came together.

Sarah Joannides is the managing director of Alternative Ownership Advisors. After switching to a PPT, Organically Grown Company received an influx of interest from other purpose-driven corporations. Alternative Ownership Advisors, a group created by Organically Grown Company, guides them along their transition. (Photo: Courtesy of Sarah Joannides)

JOANNIDES: Well, I was gonna say hippies and then I thought, well, maybe that sounds judgmental, but that's exactly what it is, right? It's a bunch of hippies, in Eugene, Oregon thinking about organic agriculture. And then they realized well, this is all fine and good but let's actually create a cooperative and let's help each other create a business model that is sustainable for selling organic produce. And they did that for a time and then they realized, well, actually, in the Northwest, there's only so many products we can grow in our region, and we want to actually become a distributor. And then a few years down the road, they said, we have this ownership divided up amongst all these farmers that started the organization but what about all these other employees that weren't original farmers that are bringing value? So they said, oh, well, let's start an employee stock ownership plan. And they were getting to a juncture in time where the employee stock ownership plan was actually creating obligations that they weren't sure that they could meet. Essentially, companies have to buy back the stock of the employees that leave and organic agriculture related industries, the valuations have gone kind of sky high in a lot of cases where there's a lot of almost speculation on the part of buyers saying I could go in and do something with this company, and I could make it really huge. So the obligations are really hard to predict. You're constantly buying back your stock. And so they sat down, and they wrote kind of a list of what do we really want. We want to be able to reward our employees in real time, we want to provide some liquidity for these early farmers that came on board. We want a ownership structure that ensures that the business won't be sold to another company that was really important to them. And unfortunately, with an employee stock ownership plan, the trustees of the ESOP have to entertain offers to sell the company if it's financially beneficial to the beneficiaries of the ESOP. And lo and behold, they came across trusts as an option. And they haven't been used very much for this purpose in the US. But there's a lot of companies in Europe that had been owned in a trust form of some kind or other, that had been very long lived, very multigenerational types of companies. So it was just this perfect storm of fit. So much of our mission is about helping the resiliency of our supply chain and of regional food systems and farming. And if we were to help them with different ownership solutions, isn't this work we should be doing? And so they decided to do that. And that's why, you know, I'm doing the work that I am today sort of spreading the word and helping others come to this particular solution.

DOERING: So most big emitters of greenhouse gases are larger, publicly owned corporations. And I'm wondering how much pressure you can put on these types of corporations with the perpetual purpose trust model.

JOANNIDES: Right, the types of companies that consider trust ownership are not publicly held companies and for the most part have not been really large companies more smaller to mid market companies. But I think what's worth saying here is that I think oftentimes, the smaller companies that are perhaps more mission driven and have been potentially acting in a way that's, you know, maybe being more responsible when it comes to emissions and other elements, giving them a way to remain viable as an independent company versus only providing them with options for being swallowed up by a larger company. That's where trust I think can provide a alternative that maybe doesn't address the large emitters. But hopefully, means that there's more smaller companies that can be resilient and sustainable over time. So again, not a solution to large emitters, but perhaps a helpful alternative that maybe reduces the amount of consolidation in some industries.

DOERING: Sarah Joannides is the managing director of Alternative Ownership Advisors, a subsidiary of Organically Grown Company. Thank you so much Sarah!

Related links:

- Alternative Ownership Advisors

- Organically Grown Company

- Learn more on perpetual purpose trusts

[MUSIC: Katie Viqueira, untitled piece, by Katie Viqueira on Amores Torcidos self-published]

Beyond the Headlines

President Biden’s executive order will create the first-ever inventory of old-growth forests on federal lands. (Photo: Dan Myers on Unsplash)

DOERING: It's time to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And he's on the line from Atlanta, Georgia. Hello, and a belated Happy Earth Day, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Happy Earth Day to you too, Jenni. We're going to start with an item from Earth Day last week when President Biden traveled to Washington State to announce an initiative to protect old growth forests. Something completely surprised me is that the United States has never taken an inventory of how much old growth forest exists on federally owned and managed lands.

DOERING: Really? That's so surprising, because we know that these are such important carbon sinks, Peter.

DYKSTRA: They are and they're just important from a symbolic standpoint that you don't want to cut old growth back. They tend to harbor some endangered species like the northern spotted owl, which was a big endangered species controversy a few decades ago. Biden signed an executive order that not only created this first ever inventory of old growth forests on federal lands, but it's also going to do a better job of looking after old growth in the face of increased wildfires. Something else that I didn't know is that wildfires in California over the last couple of years claimed what is estimated to be 10% of the entire world's biggest trees, those giant sequoia Redwoods in California.

DOERING: That's just shocking. I mean, when you think about those trees, many of them have been growing for the last 2000 years. You know, if you lose 10%, every few years, they'll be gone soon.

DYKSTRA: You kill off the old forests, you kill off other animals as well.

DOERING: Well, hopefully, at least inventorying what we have left will help protect these ancient trees. What else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: I'm gonna go nuclear on you, Jenni. There's another thing announced by the Biden administration, maybe not quite so welcomed by many conservationists. The Energy Department has launched a $6 billion nuclear plant bailout effort. Now what this would do is help utilities that because of economics are closing down nuclear plants early, they hope to extend the life of nuclear plants, reasoning that nuclear is carbon free. And this would help combat climate change. Distressed owners and operators of nuclear plants, they're going to apply for grants to prevent those plants from closing too early.

Units 3 and 4 of the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant in Waynesboro, Georgia have been under construction since 2013. (Photo: Southern Nuclear, Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: With a bailout that big, Peter, I guess that must mean that these plants are really in hot water economically.

DYKSTRA: No pun intended, economically or any other way.

DOERING: Well, what do you have for us in the history books this week, Peter?

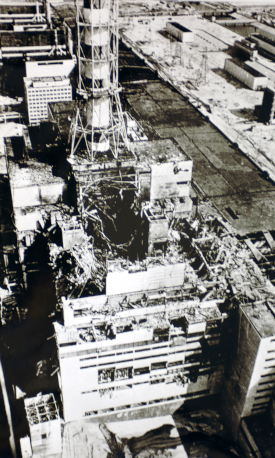

The ruins of Chernobyl’s #4 reactor, which was destroyed in April of 1986. (Photo: Ukranian Society for Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, IAEA Imagebank, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: I have more nukes, and this one also pertains to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Because on April 25, 1986, there was an explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Complex, north of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, in what was then part of the Soviet Union. A reactor core partially melted. Radiation was released in astoundingly high levels, later detected as much as 1000 miles away in Scandinavia. The Soviets relocated 350,000 people. There's a huge exclusion zone around the contaminated plant. Nobody can agree on how many people were affected by the radiation. And of course, Chernobyl is back in the news these days, because when the Russians came into Ukraine, one of the first things they did is to occupy the Chernobyl site, ostensibly to keep their hands on radioactive materials. But they may have done that literally because they were said to be digging and mucking around in areas known to be contaminated, adding to the risk to those Russian soldiers that were part of the invasion. Russia pulled out of the Chernobyl exclusion zone in a matter of weeks and left it to the Ukrainians to deal with.

DOERING: Right, I mean, one has to wonder if they really understood the risk that they were getting into with digging into this contaminated, radioactive soil.

DYKSTRA: Or given the way the rest of the war has been pursued, not necessarily whether they knew, but whether they cared.

DOERING: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And we'll talk to you again next week, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Okay, bye bye Jenni.

DOERING: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Reuters | “Biden Unveils Plans to Rescue Giant Trees as Part of Earth Day”

- The Washington Post | “Biden Administration Launches $6 Billion Nuclear Plant Bailout”

- More on the Chernobyl disaster

[MUSIC: Matt Glaser with Bruce Molsky, “Voodoo Chile,” by Hendrix/arr.Anger, on Diary Of a Fiddler, Compass Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – How a 150 year old mining law is impacting the future of renewable energy. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rajery, “Rila” on Dorotanety, by Rajery/based on traditional Malagasy music, Label Bleu/Harmonia Mundi]

Electric Vehicle Sales Stuck in the Slow Lane

The Biden administration aims for electric vehicles to make up half of all new vehicles sold by 2030. In 2021, just 6 percent of vehicles sold in the U.S. were electric. (Photo: Waldemar Brandt on Unsplash)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Switching from gas-powered cars to clean electric vehicles is a key part of the Biden administration’s plans for the U.S. to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. That’s the target the United Nations says gives us a shot at keeping temperature rise below 1.5 degrees Celsius. But that transition is so far stuck in the slow lane. Electric vehicles made up just 6 percent of all vehicles sold in 2021. That’s an increase from 4 percent in 2020 but still far from President Biden’s goal that electric cars make up half of all new vehicles by 2030. Some states are much farther ahead than others, and California is the leader by far, with 40% of the EVs in the country. The state recently surpassed 1 million electric vehicles sold. But even in Massachusetts, where a legally binding climate law requires net zero emissions in the state by 2050, EVs are nowhere near where they need to be. Reporter Sabrina Shankman covers the climate crisis for the Boston Globe and joins me now to discuss. Sabrina, welcome to Living on Earth!

SHANKMAN: Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: So how many electric vehicles does Massachusetts have right now compared to what it needs to reach its climate goals?

A lack of public chargers is hampering electric vehicle adoption across the U.S. (Photo: Roger Starnes Sr on Unsplash)

SHANKMAN: Yeah, so right now, or at least as of last month, Massachusetts had 51,431 electric vehicles on the road, but only about a little over 30,000 of those are actually fully electric, the rest are plug-in hybrids. By 2025, so right around the corner, the state is supposed to be at 300,000, according to some past goals. And by the end of the decade, right now, technically, there's a goal of 750,000, but that goal is most likely going to be revised to 1 million by 2030. So there's a lot of work to be done.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's a huge gap, I mean, if you only have about 50,000 in the state right now, and you're looking at 300,000 in just a few years. Why is the state lagging so far behind in its EV goals?

SHANKMAN: Yeah. So my co reporter on this project, Taylor Dolven, and I looked into that, and found that there were several different reasons why this is such a dire situation. One is a money problem. You know, right now, electric vehicles cost more than their gas counterparts. And what all the experts we interviewed said is that until electric vehicles reach cost parity, are equal to the gas counterparts, you're not going to see enough people flooding into them. And so that's where rebates come in. There's a federal rebate, but that's sort of iffy and complicated, and then the states can come in with their own. But Massachusetts has never really found a stable and consistent funding source so that people could have faith in it. It actually had to shut down its program a couple years ago when it ran out of funds. So that's one side of it. There's also an issue with chargers, right, because if you're buying an EV, and you're going to jump in, you want to make sure that you can have the charging infrastructure in place so that you're not gonna get stuck somewhere. A lot of people can charge at home, but if you live in an apartment, it's more complicated. So you need to make sure there's the infrastructure out on the road. And there, you know, the state is really behind, too. I mean, there are now just under 5,000 public chargers in the state. But to get to the 2025 goal of 300,000 electric vehicles on the road, National Grid did some work and found that we needed roughly 21,000 chargers.

Traffic along Storrow Drive in Boston, Massachusetts. Until electric vehicles achieve cost parity with gas powered cars, experts say, rebates are needed to encourage consumers to shift to EVs. (Photo: Second Light Photography, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's a big difference. Yeah.

SHANKMAN: Right? And then on top of all this is the added complication of the moment that we're in right now with COVID, because we have a major supply chain problem. So I have talked to people, and especially since our story ran, heard from tons of people who are like, I want an EV. I would love to have an EV! But I can't find one. Or if I do find them, the prices have been, you know, jacked up so high that they're just totally out of reach.

BASCOMB: And, of course, I'm sure Massachusetts is not alone in this set of problems that you just outlined. But are there any states that are doing this well, and that are actually making progress on their EV goals?

Electric vehicles are key, but clean public transit and safe biking infrastructure are equally critical to reducing carbon emissions from the transportation sector. (Photo: Eric Wheeler, Metro Transit, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SHANKMAN: Yeah, there's a lot. I mean, California is always the gold standard when you're talking about electric vehicles. And they've had a series of measures that have helped folks get into EVs and have helped speed up the rate of public charging infrastructure. Oregon is another one that has a really high rate of electric vehicle ownership. And they're, you know, they have a couple of things that Massachusetts doesn't have, in particular, larger rebates for low and moderate income residents. If you're a low and moderate income resident, you can get a rebate up to $7,500 in Oregon. In Massachusetts, if you're buying an electric vehicle, and it's under $50,000, then you can qualify for a rebate, it's going to be $2,500 for basically everybody. So that is considered to be one of the big things that a state can do to help drive ownership. Because we don't just want wealthy folks driving Teslas, we need everybody to get on board. I would be remiss if I didn't also add that a huge part of reaching our climate goals is also just getting fewer people to drive. That's a major part. If everybody just switches over from gas vehicles to EVs, we haven't really solved the problem. We also have to electrify transit, get better bike lanes, get people on bikes on E-bikes. But there will still be a lot of drivers. And so for that it has to be equitable. And we have to find a way to get lower and moderate income people, you know, make it in reach for them as well.

BASCOMB: Well, on a federal level, the $1 trillion infrastructure bill that was signed into law last year included roughly seven and a half billion dollars for electric vehicle infrastructure. I know it's only been a few months here, but how might that money helped to encourage electric vehicle sales on the state level? And are you actually seeing any changes yet?

The Massachusetts State House as seen from Boston Common. In 2021 the Massachusetts Legislature passed, and Governor Charlie Baker signed into law a legally binding climate goal of 50% emissions reductions by 2030 and net zero by 2050. (Photo: Daniel Mennerich, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SHANKMAN: So we're not seeing any changes yet, but the state is still working on plans that would direct a good chunk of that money toward building out the infrastructure. But everyone that we talked to said, you know, you can't just rely on that alone. It will be both using that money really strategically to make sure that those charges are getting put in the right places, but also finding other funding sources so that we can build on that in a much bigger way. Because, at the end of the day, if you don't electrify transportation, electrify our buildings and clean up the grid so that what is powering those buildings and vehicles is, is renewable energy, we're just not going to meet our climate change goals. And in Massachusetts, it's a legally binding climate goal, I mean we had a bill that passed last year that was signed into law. And it requires that the state reduce emissions by 50% below 1990 levels by the end of this decade, and hit net zero by 2050. So the writing's on the wall, there are these very clear deadlines and time is running out.

BASCOMB: Well, how optimistic are you that the policies will come through and the buildout of charging infrastructure will happen and consumers will soon switch from buying mostly gas powered cars to electric ones?

SHANKMAN: Optimism is, is a tricky thing, when you're a climate change reporter. [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] I know!

Sabrina Shankman covers climate change for the Boston Globe. (Photo: Courtesy of Sabrina Shankman)

SHANKMAN: I, um, I have a lot of faith in the people that I talked to who are working in this space, I think that there are really smart advocates and legislators and experts who are doing all the right things, you know, who are, who are really being innovative and creative and treating this challenge with the urgency that it requires. And so that's awesome. But then when I walk around the city of Boston -- and you know, when you work on a story, you suddenly become very attuned to everything related to it. So I was walking around Boston the other day, and I was thinking about chargers. And as I'm rolling through these neighborhoods on foot, I'm thinking, Oh, okay, so where are the, where are the chargers in that lot, and what about that? And I just wasn't seeing them, you know? Between now and 2030, which is really, like, I have an elementary school kid, like, he'll be, he'll still be living at home! [LAUGHS] There have to be chargers everywhere we look. And so to think about the scale of the transition that is needed is, it's really shocking. We're no longer at the part where we can be ramping up. We're sort of at the part where, like the, not to make a driving analogy, but like your foot has to be all the way down on the gas at this point, you know? And so it's just a question of if these measures that are being talked about right now can do what needs to be done quickly enough.

BASCOMB: Sabrina Shankman is a reporter with The Boston Globe. Sabrina, thank you so much for your time today.

SHANKMAN: Thank you.

Related links:

- The Boston Globe | “Massachusetts Needs At Least 750,000 Electric Vehicles on the Road By 2030. We Are Nowhere Close.”

- The New York Times | “As Gas Prices Went Up, So Did the Hunt for Electric Vehicles”

- Check out the Boston Globe’s other climate coverage

- Connect with Sabrina Shankman on twitter

[MUSIC: The Vignola Collective, “Slayer In the Grass” on Gypsy Grass, by Hanneman/King, Dare Records]

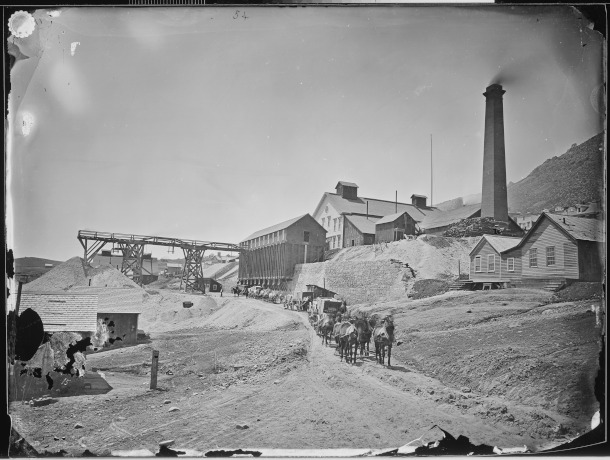

150-Year-Old Law Robs Public Lands Riches

Opencast mining (Photo: Geography Britain and Ireland, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Well making electric vehicles affordable for consumers isn’t the only challenge in transitioning away from cars powered by fossil fuels. To fast track electric vehicles and a renewable energy transformation we also need minerals like lithium that make battery storage possible. But in the US, the legal extraction of those minerals on public lands relies on a 150-year-old law, the General Mining Law of 1872, which doesn’t require that mine operators pay royalties to the government. It was put in place to spur settlement of the West when the country was young but today the antiquated law affords very limited protection for the environment or local people. For more, we turn to Jim Robbins, a veteran journalist based in Helena, Montana who wrote about the mining law for Inside Climate News. Jim, welcome to Living on Earth.

ROBBINS: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So last year, a new open pit lithium mine was approved and Thacker passed Nevada, give us a sense, please of the importance of lithium and some of the other minerals found out west in terms of transitioning towards a green economy.

ROBBINS: Lithium is probably the most important mineral for the decarbonization of the world. It is central to electric batteries for electric vehicles. It's lightweight, it holds the charge very well. And you can charge it again and again and again. So its importance can't be overestimated. And there is a global competition to be the companies that extract and sell lithium. It's it's really soared in price in the last few years and will probably go even higher.

BASCOMB: That obviously creates a lot of demand if the price is going up.

ROBBINS: Yes, I mean, the demand is off the charts. And there's a worldwide scramble for new resources. This mine, in fact, her pass in Nevada, near the Oregon border is the largest in the US. So it's very valuable. It's worth it right now at these prices are over 4 billion. And it may be worth a lot more as the mine continues.

BASCOMB: Now, these mining companies that are extracting these minerals are operating under a law put in place by Ulysses Grant back in 1872. Give us a sense of the law, please. You know, how does it apply to these mining companies and what rights and restrictions are in place?

ROBBINS: Ulysses Grant signed this into law a few months after he signed The National Parks Act that created Yellowstone National Park. So he had a, a varied approach to to the West in just a few months time. The law was created to spur the development of the West to bring people out primarily for gold and silver deposits. It was essentially a giveaway. So people would make the trip to the west and explore if you go out on the landscape and pound for stakes in and locate a claim that entitles you to explore for minerals on that 20 acres exclusively. And if you find something, you can patent it. And if it's valuable, you have to prove it up, you have to show that it's worth developing. If you do prove that it's worth something you can patent it, which means you can own it outright.

Savage Silver Mining Works, located in Virginia City, Nevada predates the 1872 mining law. (Photo: Timothy O'Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Well, a lot of the Western US the land is federally owned this new lithium Mine is in Nevada, which is almost 90% of the state of Nevada is owned by the federal government, be it Bureau of Land Management National Park, what have you. But you write here that these mining companies that work on this publicly owned land, they don't have to pay any royalties or fees to access the land. I mean, oil companies have to pay royalties, why not mineral companies?

ROBBINS: Well, that's the way the law was written because it wanted to benefit miners who would come out here and make as much money as they could and it would spur development. You know, what's interesting to me is a lot of the mining in the West is done by Canadian companies. So they're profiting off of this archaic law substantially. And then in this case, Lithium America is the largest shareholder is Chinese. And Chinese are one of our great competitors in lithium mining. So a lot of the benefits of the mining law of 1872 are going to other countries and mining companies and other countries. And it seems a bit ironic that our competitors are benefiting from such a law that not only gives away our mineral deposits, but lets them get away with less than a full reclamation of these sites.

BASCOMB: Let's unpack that a little bit. It seems like there's a lot of potential environmental concerns here. And chief among them are water. Roughly 40% of Western watersheds you write in your article have been contaminated by mining. What kind of contamination are we talking about here?

ROBBINS: Well, in this case, it could be sulfuric acid, a story in The New York Times said antimony is one of the minerals that could leach. According to the Environmental Impact Statement, arsenic is another chemical that could leach into groundwater. A lot of times these mines with bare rock when they get rained on, they create sulfuric acid which leeches into the water and this water one of the ranchers has said this groundwater could, could drive him out of business, if it becomes polluted because he won't have any to raise his cattle. It's supposed to drop the water table by 12 feet according to the environmental documents. So there's a whole host of things that the state and federal regulators have said, well, we can live with these. But people are saying well if if things get out of control, or they don't happen the way they've planned, then we can have some real damage here.

Large scale mountaintop removal mining operation in the Kentucky Appalachian Mountains. (Photo: Doc Searls, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Right. And you write that the mining companies very often don't stick around to remediate the mines once they're done extracting the lucrative resources or to cleanup the watershed, if they've contaminated. Taxpayers are often left with that bill, how much is that costing us?

ROBBINS: There are 140,000 abandoned mine features across the West. And as of two years ago, it's cost about 50 million for just for one site to clean up and billions of dollars to put these things right. And there is money in legislation pending in Congress that would add to that, because there are so many sites that have been left untreated.

BASCOMB: Let me just get this straight. Because I think this is a lot to wrap your mind around. We have a 150 year old law that allows foreign companies from Canada, China, wherever to come to the United States extract these very, very valuable resources without paying any royalties, any money going to the citizens of this country, the government, they take these valuable resources out, make a bunch of money from it, and they don't necessarily have to pay for the full damage that they might cause. What are we getting out of this?

ROBBINS: Now the company would say, this is critical for clean energy future, the Biden administration has made this a priority to mine lithium and cobalt and nickel and other things central to these batteries. But at the same time, they've said we have to have reform for the mining law of 1872. So we'll see how that goes. There have been bills introduced over and over again, since even before electric vehicles became a thing. I've been covering this subject since 1980s. And there have been many bills introduced to reform the mining law of 1872. They've never passed, there's too much money to be made. And there's a lot of resistance from mining companies which are very powerful. And so any effort to pass congressional reform is probably not going to make it. Experts tell me the best bet for reform will come through regulations. The BLM and Forest Service will have to promulgate those regulations to tighten the law and the reclamation requirements.

BASCOMB: Jim Robbins is a veteran freelance reporter based in Montana, Jim, thanks for your time today.

ROBBINS: You're welcome. Thanks for having me.

[MUSIC: Matt Glaser with Richard Greene and Buell Neidlinger, “Bemsha Swing” on Diary Of a Fiddler, by Best/Monk, Compass Records]

DOERING: Coming up – 200 new species of freshwater fish were discovered last year, we’ll have details about a few of them just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dan Sullivan, “Wave” on Cape Cod Magic, by Antonio Carlos Jobim, self-published]

200 New Freshwater Fish Species Discovered

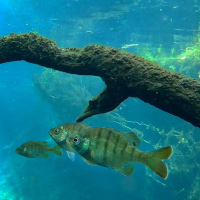

About half of all fish species live in freshwater. Pictured above is the bluegill sunfish, commonly found east of the Rocky Mountains. (Photo: Siddarth Machado, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

More than 200 new species of freshwater fish were discovered in 2021, that’s according to a recent report from the conservation organization Shoal. The discoveries add to the more than 18,000 species of freshwater fish already know to science. Harmony Patricio is Shoal’s conservation program manager and she joins me now for more. Harmony, welcome to Living on Earth.

PATRICIO: Thank you, thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: These 212 new freshwater fish species, I mean, these aren't just tiny little, you know, minnows or little things that you could see how they can easily be overlooked for a long time. Some of these are actually large fish, can you describe a couple of your favorites for us please?

PATRICIO: One of them is called the Mumbai blind eel, and it has no eyes, fins or scales. It just has smooth skin that is full of blood vessels and gives it this reddish coloration. It's a subterranean fish. It is from the northwestern Ghats of India. And one remarkable thing about this story of this discovery is that this blind eel was found in a 40 foot deep well, on the premises of a school for the blind. And the genetic analysis, the researchers who described the species have done show that it's likely it's split from its closest relative over 1 million years ago. So it's had a lot of time to evolve very distinct attributes.

#NewSpecies:

— Shoal (@Shoal_Org) April 4, 2022

Mumbai blind eel.

❌ NO fins.

???? NO eyes.

⚖️ NO scales.

???? May have split from closest living relative ONE MILLION years ago, making it remarkably unique.

???? https://t.co/79pDjZL9eI pic.twitter.com/Cu1jAlkOU1

BASCOMB: And I understand there's also something scientists have called a wolverine fish. Can you tell us about that?

PATRICIO: Yeah, this one has gotten a lot of interest, I think because of the name Wolverine. It's a wolverine pleco, it's called. It has an interesting characteristic where it has these lateral spines that can protrude from its Gill coverings that it uses to defend itself in a somewhat violent manner. If anything tries to mess with it, they're gonna be in trouble. The researchers who described this species said in the process of collecting them from the wild, they ended up with bloody fingers. And interestingly enough, other closely related species in this family have never been seen to exhibit this type of behavior, even those that do have these type of spikes.

BASCOMB: I wonder if maybe that's why scientists haven't described them before. Now, you know, they just came up with an individual that looked kind of similar to another one and said, oh, that one's too rough let's let it be.

PATRICIO: [LAUGH] Oh that's a good point. Yeah, maybe nobody wanted to mess with it. Apparently the local fishers in the area where the scientists are working decided to call the fish Buffalo Bill, because it was so aggressive and stabbing everybody with its with its spines.

BASCOMB: That's a solid defense, you have to admit.

2⃣1⃣2⃣ species of freshwater fish were newly identified last year, including this brightly coloured goby from Okinawa, Japan ????????

— Shoal (@Shoal_Org) March 24, 2022

Shoal today release a landmark New Species 2021 report detailing this guy, a fish called Wolverine, and much more.. Read on!????https://t.co/statOFhdSG pic.twitter.com/yUDlKDjvEO

PATRICIO: [LAUGH]

BASCOMB: On the other end of the spectrum, I understand that they found a fish where you can actually see its brain through the skin on its scalp. Can you tell us about that?

PATRICIO: Yeah, this is a pretty interesting story. So this is an example of a species that was known to science, but had been misidentified for years. It's native to Myanmar and it's very tiny about the size of your thumbnail. And it's been used by neuroscientists for research for several years. So it's just sitting under their noses until they did some genetic analyses, and found out it's a completely different species than they thought it was, it became a unique species at least 15,000 years ago. The reason it's such a great organism for neurophysiological research is because as you said, it has an open skull, and transparent skin on the top of its head. So you can visually observe its brain while it is alive. And you can use that to collect data on brain activity related to different behaviors. The males of these species communicate with each other through sound. And that's another really interesting thing that they're able to see is like, what does the brain do when they're receiving these communicative sounds and how does it process those sounds. So these studies are actually providing data that can expand our understanding of brain function in humans as well.

BASCOMB: Wow. So interesting. Now, we've been talking about all of these new species of freshwater fish, but from what I understand roughly a third of freshwater fish that we know of, are threatened with extinction and the populations of some freshwater fish have dropped really dramatically. Can you tell us more about that? Why are freshwater fish so threatened right now?

PATRICIO: It's a combination of factors. A lot of it stems from the fact that humans are, you know, inherently reliant on freshwater ecosystems for our own survival. Part of the issue is for some species, is that they have been over harvested, especially in the cases of mega fish as we call them, which are the world's biggest freshwater fish. Their populations have collapsed by around 94%. Typically, they do not mature to where they're able to reproduce until very late age. And so if they're harvested, you know, when they're only five or 10 years old, they haven't had a chance to breed yet, it's going to really drop down the population very quickly. Another big problem is invasive species. About a third of modern freshwater fish extinctions can be traced back to the impacts of invasive species. They change the environmental conditions in the water bodies that they're introduced too. They often prey upon native species, or compete with them for food sources. Also, pollution has been a huge problem all from agricultural runoff to industrial that can really affect fish's health and ability to reproduce successfully. The fragmentation of habitats such as damming rivers and reducing fishes ability to complete their life cycles by moving from downstream to upstream has had a significant impact. And climate change is also starting to have a real impact as well.

There are more than 2,000 freshwater fish in Brazil alone. Some can be found in areas like the Iguazu Falls pictured above. (Photo: Boris Kasimov, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, why are freshwater fish so important? And why should we really be paying attention to this problem?

PATRICIO: I would say there are many reasons that we should all be paying attention and concerned about the decline of freshwater fish. In many ways. They're like the canary in the coal mine. They're an indicator group of animals that show us what's happening with the health of aquatic ecosystems that we as humans are highly dependent on. If the fish are not doing well, we can be assured that those systems are not going to be very useful for humans down the road.

BASCOMB: Harmony Patricio is the Conservation Program Manager at Shoal. Harmony Thank you so much for your time today.

PATRICIO: Thank you, Bobby. It was great to talk to you.

Related links:

- The Guardian “Wolverine Fish and Blind Eel Among 212 New Freshwater Species”

- Eco Watch “Over 200 Newly Discovered Freshwater Species: Shoal Report”

- Read the report published by the conservation organization Shoal on the New Freshwater Species discovered in 2021

[MUSIC: Lewis Porter-Phil Scarff Group, Skies of South Africa Suite: Bird Songs Of Hermanus on Three Minutes To Four, by Lewis Porter/Phil Scarff, Whaling City Sound]

An Interview with the Ocean

A turbulent ocean (Photo: Aaron Huber on Unsplash)

DOERING: As we close out Poetry Month, we want to share a timeless poem read here by the poet herself, Mary Oliver.

“I Go Down to the Shore”

Reprinted by the permission of The Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency as agent for the author. Copyright © NW Orchard 2012 with permission by Bill Reichblum

OLIVER: I Go Down To the Shore

I go down to the shore in the morning

and depending on the hour the waves

are rolling in or moving out,

and I say, oh, I am miserable,

what shall —

what should I do? And the sea says

in its lovely voice:

Excuse me, I have work to do.

DOERING: Mary Oliver won the Pulitzer Prize for a collection of her work in 1983. She passed away in 2019 but her depiction of the Ocean as a steadfast companion in times of trouble continues to inspire other poets like Kate Horowitz. Kate told us she turned to Mary Oliver’s poem at a challenging point in her own life.

HOROWITZ: The morning after what was probably the worst night of my life, I went to a diner and got myself breakfast and brought a book of Mary Oliver poems, because that’s what you do, and I was looking for anything that could help me. And I came across that poem, “I Go Down to the Shore.” And the pragmatic perspective of it really just kind of helped me come down from the intense state of nervous system activation I was in, it really just made me feel like, this is a problem, things are bad, and life is going to go on.

[OCEAN WAVES -- HOLD UNDER BELOW SCRIPT AND PHASE IN MUSIC, GULLS]

DOERING: And here is the work inspired by that moment, titled An Interview with the Ocean. In it, Kate plays herself and The Ocean is portrayed by Living on Earth’s own Aynsley O’Neill.

[MUSIC, SOFT OCEAN SOUNDS, SEAGULLS]

HOROWITZ: Good morning. Thanks so much for being here.

O’NEILL: It’s fine. I don’t have anywhere else to be.

HOROWITZ: I have to admit, I’m feeling weirdly nervous about this conversation.

O’NEILL: Why would that be weird? I’m the ocean.

This interview is probably a big deal for you.

HOROWITZ: Well, it definitely is, but we’ve spoken so many times before.

Informally. Off the record.

O’NEILL: Have we?

HOROWITZ: Ouch.

O’NEILL: It’s just that there are so many of you—

HOROWITZ: No, no, I totally understand.

HOROWITZ: [voice catches]: I’m sure I didn’t say anything memorable anyway. [coughs, clears throat]: Anyway. Let’s get into it.

O’NEILL: Sure.

HOROWITZ: In her poem “I Go Down to the Shore,” Mary Oliver recounts an exchange with you that she found particularly meaningful.

She remembers telling you her problems and unburdening the weight from her heart.

O’NEILL: Ok.

Writer Kate Horowitz “interviewing” The Ocean with her smartphone. (Photo: Courtesy of Kate Horowitz)

HOROWITZ: Your response to her sharing, as Oliver recollects it, was “Excuse me, I have work to do.”

O’NEILL: [chuckling]: Well, that definitely sounds like me.

HOROWITZ: Do you recall that conversation at all?

O’NEILL: I really don’t. As I said, there are so many of you.

And honestly—don’t take this the wrong way—I can’t tell you apart.

HOROWITZ: Ah.

O’NEILL: You all say the same things.

“Oh, I am miserable. What shall—what should I do?”

HOROWITZ: That’s exactly what Mary Oliver said.

Are you quoting her poem? Do you know it?

O’NEILL: No, and that’s my point.

Whoever this person is, she definitely wasn’t the first one to say it, and she wasn’t the last.

I get the impression that you’re all kind of miserable.

HOROWITZ: Yeah. Things have been pretty rough lately.

O’NEILL: Lately?

HOROWITZ: Well, ok. Forever. But more lately.

It’s just…hard. It’s hard being a person.

Rocks on the shore (Photo: Courtesy of Kate Horowitz)

O’NEILL: So don’t be. Have you tried changing?

Becoming something better?

Lobsters seem to have things figured out.

HOROWITZ: I don’t know if I could become a lobster.

I don’t think we get to choose.

[sniffs]

O’NEILL: Are you crying? Are you actually crying in an interview?

An interview you’re conducting?

Don’t you have to be trained to interview people?

Don’t they teach you on like the first day of interviewer school or whatever that you should never cry on the air?

If they don’t, they should. Talk about unprofessional.

HOROWITZ: [sniffling]: Why are you being so mean today?

O’NEILL: Am I? Wait, what do you mean, “today”?

HOROWITZ: [sniffling] I cry with you all the time.

O’NEILL: You do?

HOROWITZ: [blowing nose]: Yeah. I come visit you after work.

I sit with you, and I watch the waves, and I breathe in the salt air, and I cry.

O’NEILL: Why?

HOROWITZ: Why what?

O’NEILL: Why do you come visit me?

HOROWITZ: Well, I—

O’NEILL: Why do any of you come visit me?

[louder]: Why do you think I have the answers?

Why me? I don’t— [voice breaks] [RAIN, THUNDER]

[a large wave crashes]

HOROWITZ: …Are you crying?

O’NEILL: No. I’m the ocean. I can’t cry.

HOROWITZ: It seems like…maybe you can? And you are?

It’s ok if you are.

O’NEILL: [crying]: Everyone’s just so lost. You’re carrying such heavy burdens.

I don’t know how you can even move. So much suffering.

Even the lobsters! Especially the lobsters.

O’NEILL: [crying]: It’s all of you. And I don’t know how to help.

The Ocean cries, “So much suffering. Even the lobsters! Especially the lobsters.” (Photo: Eric Heupel, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

HOROWITZ: Oh.

[a larger wave crashes, then one even bigger.]

Hey, hey, hey, hey. Is it ok if I put my hand on your back?

O’NEILL: [sniffling]: Yeah.

[quiet splashing sounds]

HOROWITZ: Hey. It’s ok. It’s ok.

O’NEILL: [sniffs]: Would you listen to me? I’m such a cliché.

“I’m miserable! And I don’t know what to do.”

HOROWITZ: Oh.

O’NEILL: It’s why I always say I’m busy.

O’NEILL: [laughs hoarsely]: I’m not busy! This stuff basically runs on autopilot.

I don’t even do the tides. That’s all the moon.

[sighs]: I just feel helpless. I see you hurting—each of you—all of you—and I can’t do anything about it.

HOROWITZ: But you don’t have to do anything. That’s kind of the point.

O’NEILL: What do you mean?

HOROWITZ: I don’t come down to the shore so you can fix my problems.

I can handle my problems. I just like being with you.

You don’t have to do or be anything other than what you are.

You’re the ocean! You’re already perfect!

What more could you possibly be?

O’NEILL: [sniffs]: That’s true.

HOROWITZ: Who you are is wonderful.

[quiet splashing sounds]

Who you are is enough.

Kate ends by soothing a troubled Ocean: “Who you are is wonderful… who you are is enough.” (Photo: Thomas Vimare on Unsplash)

DOERING: That’s writer Kate Horowitz and Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill performing Kate’s piece, “An Interview with the Ocean,” which first appeared in the science writing blog, The Last Word on Nothing.

Related links:

- Kate Horowitz’s piece “An Interview with the Ocean” first appeared in the science writing blog, The Last Word on Nothing

- About Kate Horowitz

- Kate Horowitz Instagram

- Kate Horowitz Twiter

[MUSIC]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Gabriella Diplan, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth