January 13, 2023

Air Date: January 13, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Pink Snow and the Climate

View the page for this story

Pink snow, also known as “watermelon snow” or “glacier blood,” is the result of a typically late summer bloom of pink colored algae that flourish in melting snow. And although snow algae are still very understudied, scientists are worried that darker snow will absorb more of the sun’s heat than white snow and cause the snowpack to melt more quickly. Jim Elser, a professor of ecology at the University of Montana, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain the implications for climate change and summertime water supplies that rely on steady runoff. (10:50)

Extreme Weather and the Jet Stream

View the page for this story

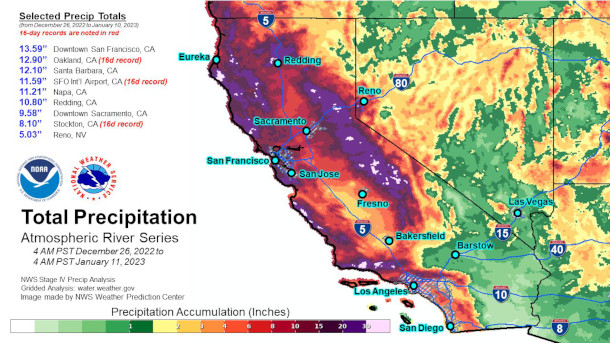

Weather records are now routinely getting shattered across the United States, with recent severe rainstorms in California, freezing temperatures in Texas, and a warm January thaw for the northeast. Jennifer Francis, Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, joins Host Steve Curwood to explain why a climate disrupted jet stream is behind much of this extreme weather. (21:37)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s look Beyond the Headlines, environmental journalist Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood admire the greenery in New York City, which a new study has reported absorbs as much carbon as all the traffic in the city emits on many summer days. They then discuss the climate implications of the Republican House Speaker battle before looking back at Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, who created the Grand Canyon national monument on January 11th, 1908. (05:07)

BirdNote®: White-Browed Coucal

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Many cuckoos forgo the demands of parenting by laying their eggs in the nests of other birds. But as BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports the white-browed coucal, common in many parts of Africa, build their own nests and raise their own young. (01:43)

Rescuing Bats from Extreme Cold

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

In Texas, this winter’s extreme weather delivered an unusual cold snap that some bats just couldn’t deal with. So, Mary Warwick, the Wildlife Director of the Houston Humane Society, sprang into action and along with help from Bat World Sanctuary saved around 1600 Mexican free-tailed bats from hypothermic shock. Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran shares her story. (07:14)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230113 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jim Elser, Jennifer Francis

REPORTERS: Paloma Beltran, Peter Dykstra, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

From fires to floods, California’s severe weather is yet another sign climate disruption is here.

FRANCIS: Yes, storms have always hit California, we've always had these kinds of patterns, but we're seeing them on steroids now. We're seeing them fueled by more moisture, by more heat in the oceans, and so it's not just your run of the mill storm anymore.

CURWOOD: Also, warming promotes algae that can cause snow to turn pink.

ELSER: Imagine the world's largest watermelon snow cone you've ever bought. It really literally looks like that, when you get close to it or pick it up; it looks like an Icee: pink, watermelony kind of a tinge, maybe sometimes along the orange side; it's pretty strange.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Pink Snow and the Climate

“Glacier blood” is another nickname for the melted remnants of pink snow. (Photo: Jim Elser)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Parts of California are now drowning amid days of downpours. The sudden influx of rain could help pull the state out of record droughts but it’s too much too fast to store and fully absorb into the ground, especially in developed areas with engineered canals and levees designed to contain water and not allow it to soak into the soil naturally. Likewise, much of the American West relies on snow melt to fill lakes and streams and recharge aquifers but when the snow melts too quickly water simply runs off the land before it can be absorbed. Scientists have long worried about how climate change is causing snow to melt more quickly and now they have a new concern. Pink snow. Sometimes called “watermelon snow,” or “glacier blood” pink snow is the result of pink colored algae that flourish in melting snow. And although pink snow is still very understudied, scientists are worried that darker snow will absorb more of the sun’s heat than white snow and cause the snow pack to melt more quickly. That has important implications for climate change and summertime water supplies that rely on steady runoff. Here to explain is Jim Elser, a professor of ecology at the University of Montana. He joins us now, welcome to Living on Earth!

ELSER: Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: So how would you describe pink snow for someone who's never seen it before?

Snow algae thrive in high-altitude snow patches at just above freezing (Photo: Jim Elser)

ELSER: Well, I like to imagine the world's largest watermelon snow cone you've ever bought. It really literally looks like that, when you get close to it or pick it up, it looks like an Icee: pink, watermelon-y kind of a tinge, maybe sometimes along the orange side, but it looks like someone has spilled a snow cone maker down the side of the mountain. It's pretty strange.

BASCOMB: So how wide of an area are we talking about that would be pink?

ELSER: It'll depend. Sometimes it can be the entire, an entire snowfield in front of you, you know, you're looking at a 50, 100 meters of snow around you. And it's also sort of got this pink color to it. Very often, it'd be very patchy, it'll be a tiny little patch, maybe the size of a throw rug or something like that or smaller, or there'll be a whole sort of channel of it, you know, where the snow is a little bit lower in some depressions, and it'll be visibly red there and not so much anywhere else.

BASCOMB: And is there a part of the world where you're more likely to find this pink snow? Which mountains are we talking about here?

ELSER: It's worldwide. It's polar regions; best studied in the polar regions, especially in Greenland in the ice sheet and other areas in the Arctic; the snow algae are documented in the Antarctic, and they're found in mountains all around the world. It's a ubiquitous phenomenon. not well understood I'd say, as far as, you know, what controls its spatial distribution, or how dark it is, or which species necessarily it is. So those are still a lot of open questions, which is fun when you're a researcher, obviously.

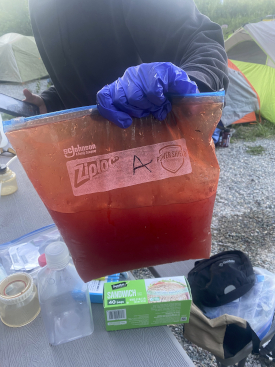

A snow core sample containing pink snow and the snow algae that causes it (Photo: Jim Elser)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I mean, it leads to a lot of questions that you can answer, a lot of research to be done.

ELSER: Or, or, struggle to answer! [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Well, I mean, if all the answers came easily, where's the fun in that, right? Anybody could do it.

ELSER: That's right, that's right.

BASCOMB: So why exactly is the snow pink? I understand that it's algae. But what's going on here?

ELSER: Yeah, well, paradoxically, pink snow algae or pink snow is generally caused, usually, by members of the green algae. Now that's confusing! "Green algae" is the sort of phrase we use to describe members of a certain type of algae. They're pink because they make red pigments, carotenoid pigments, like the ones you have in carrots, and they make those pigments probably to protect themselves against the extremely high light intensities that they experience at the surface of the snow. And so you're looking at carotenoids, that's why we see them as that red watermelon color.

BASCOMB: And what do they live off of? I mean, we're talking about very cold regions, snow, there's not a whole lot going on there to support life.

ELSER: Yeah, I know, that's, well it's sort of a extreme environment, except, you know, these are cryophiles: "cryo" meaning cold, "phile" meaning loving; they love the cold, actually, do best when it's cold. And you know, if you grow them in the lab, they do best when it's like two degrees centigrade, right, just a little bit above freezing. So they actually like it cold. In any case, so how do they make a living? Well, they're photosynthetic, so they're harvesting sunlight and using that to make sugar, the way that all sort of photosynthetic organisms do. Of course, there's a lot more to growing and making a big bloom than just getting light. They have to get nutrients, and especially nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, the same sort of stuff we put in fertilizers to make crops grow or our grass green. So there's nitrogen and phosphorus in snow -- snow is not just pure frozen water. It forms in, you know, snow forms in the atmosphere, gets nucleated around dust particles, and those have phosphorus and nitrogen in them. There's nitrogen oxides that are in the atmosphere that come out in snow, there's ammonia and urea from fertilizer that gets volatilized and put into the atmosphere and that comes out in snow. So the snow has different amounts of phosphorus and nitrogen in it and they are taking that up and using that to build their biomass. And so it's sort of like the same way algae have to make a living, the same way they do in lakes, right? They harvest the sun, they take nutrients from the water and they grow. It's the same sort of story with snow algae.

A bag of red snow algae collected for processing in the lab resembles watermelon juice (Photo: Jim Elser)

BASCOMB: So pink snow, it's more important to us than just this curiosity. Why is pink snow actually important to climate science?

ELSER: Great question. Yeah, so it is fascinating to learn about, obviously, but there are other dimensions of it. So for snow algae to grow, they need free water. They need unfrozen water to grow and take up nutrients in. And you know, under warmer conditions that, that obviously come in summer, you know, the snow melts, starts to melt a bit and the snow algae can grow to take up nutrients. And the more, the longer in the summer we have the warmer conditions, there's more free water availability, both seasonally but also day and night, right? So that free water availability allows the snow algae to metabolize and take up nutrients and proliferate. And then there's an interesting feedback further. And that is the snow algae obviously changes the color of the snow, makes it darker, changes the albedo. Scientists call the brightness of something the "albedo" -- how much incoming radiation from the sun is reflected back. And white snow is obviously reflecting everything back at you at all the wavelengths, that's what white light is. But when there's a lot of snow algae in the snow, it has a dark red color. That means it's only reflecting a lot of the red back, it's absorbing a lot of the other wavelengths. And that, that absorption changes the melting, warms the snow up a bit more. And so the snow algae's sort of affecting their own environment. And there's a little bit of a feedback that gets going there, right. So as they proliferate, they make it darker and the albedo goes down, absorbs more radiation, melts the snow a bit more. So we're concerned about snow algae proliferation, because it can change the rate at which snow and ice are melting in the cryosphere, the cryosphere being the frozen part of the, of the world.

BASCOMB: So the more pink snow you have, the more the snow warms quickly; the more warming you have, the more algae you have, the more pink snow you have, the more warming you have. It's, it's a positive feedback loop.

Jim Elser in the field while studying pink snow algae. (Photo: Jim Elser)

ELSER: Yeah, it's a little concerning. Yeah, that's right.

BASCOMB: And is that being accounted for in, you know, the big climate modeling that scientists are looking at?

ELSER: Not yet, I think there's been some calls for it to be incorporated. I think, you know, especially, you know, people who are just, who are trying to model snowpack with respect to like water output, right, that's needed for irrigation or other uses, right? Having more information, better understanding albedo effects of snow algae might be able to help us improve the modeling, even at the watershed scale of snow melt, and its timing. And at the global scale, yeah, I, you know, there's a lot of things that go into those models. I think that it would be useful, especially for those modeling the larger ice sheets, they're starting to incorporate the albedo effect. And they need to because I think it's been shown that 75% of the melting on the Greenland ice sheet is attributable to the albedo effects of glacier algae. So the Greenland ice sheet is getting quite dark. And it's mostly because of ice algae, not snow algae, like we're talking about, it's a different group of organisms, but it's a similar sort of story. So to understand the Greenland ice sheet, people are realizing that we need to understand the snow algae growing there. And there's a lot of people working on that problem right now, thankfully.

BASCOMB: Yeah, that's huge. That's absolutely huge. What do we know about this type of snow algae historically? And how can that information maybe inform us, you know, what we should be looking at going forward?

Postdoctoral researcher Pablo Almela Gomez of the University of Minnesota logs snow algae data in the field. (Photo: Jim Elser)

ELSER: Unfortunately, yeah, there's not, you know, historical monitoring of snow algae, it's, it's hard to monitor; it's in a difficult location. You know, you have to get back up in the mountains and unlike other ecological phenomena, like lake productivity or lake clarity, where we have some excellent records going back a century or so, and there are some forest ecosystems and grassland ecosystems which have very good long term data. There is no long term monitoring program for any snow algae. So we don't have really good records of snow algae abundance going back to know how it's changed or not. I, I'm wondering and thinking that paleolimnology methods, that is the study of the past through the sediment records of lakes, could help us. So if you're in a catchment with a high elevation lake that has, you know, snowpack in it and snow algae in it, then perhaps remains of those snow algae after the snow has melted find their way into the lake and get stored in the sediments. And so we might be able to reconstruct the history of snow algae in a catchment or in the set of catchments, if we can find a way to reconstruct the remains of snow algae in the sediments. We might, if we had, you know, be able to go back a bit with satellite, you can sometimes see, you know, pronounced blooms in satellite images. But even the resolution of those is pretty poor once we go back more than 20 or 30 years. So, we're sort of stuck in the "invisible present," as it's been called. So we don't really know whether snow algae is going up or down right now because we don't have any long term records.

BASCOMB: Jim Elser is a professor of ecology at the University of Montana and the Director of the Flathead Lake Biological Station. Jim, thank you for your time today.

ELSER: It's my pleasure.

Related links:

- High Country News | “Pink Snow Is a Red Flag for the West’s Water”

- About Flathead Lake Biological Station

- Elser’s research is supported by a grant from the Ecosystem Studies Program at the US National Science Foundation

- About Jim Elser

[MUSIC: Ennio Morricone,/Bulgarian Symphony Orchestra, “The Tropical Variation,” on The Best of Ennio Morricone by Ennio Morricone, Sony BMG Masterworks]

CURWOOD: Coming up – how climate disruption is shifting into a higher gear. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dr. Michael White, “Give It Up” Gypsy Second Line, on New Orleans, by Michael G. White, Putumayo World Music]

Extreme Weather and the Jet Stream

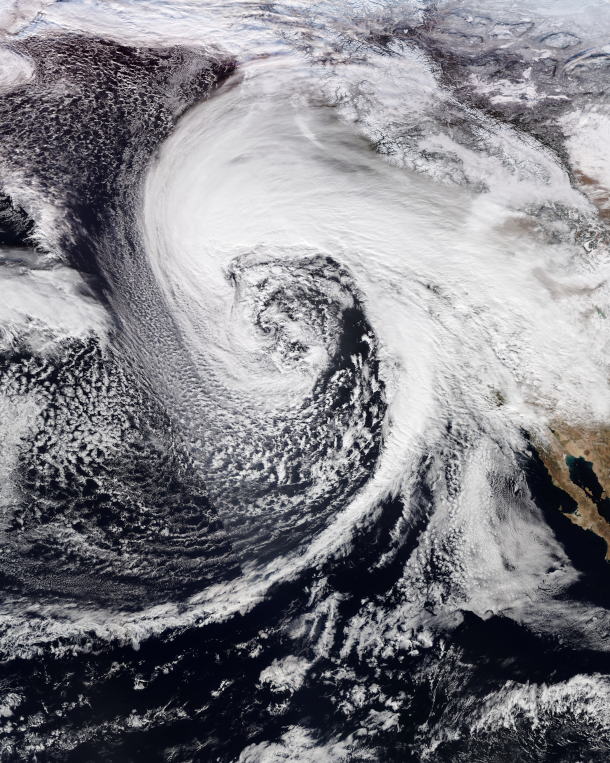

The northwestern United States bomb cyclone in January 2023. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

2023 has barely begun and already weather records are being shattered around the world, including the severe rainstorms in California.

ANNOUNCER: The city of Santa Barbara is seeing about 6 inches of rain yesterday alone. Flooding homes and major highways with more rain on the way.

ANNOUNCER 2: North bound of the 101 shutdown because of this. What is typically a babbling creek is now a raging class 5 river. This is what 6 inches of rain on top of saturated ground looks like.

ANNOUNCER 1: A new round severe weather is now triggering flood waters in areas at risk of mudslides because previous wildfires that have made vegetation less stable.

BASCOMB: At the same time parts of Europe experienced a heat wave that had many ringing in the New Year in t-shirts. Meanwhile on the south coast of the US, Florida broke heat records and much of Texas plunged to below freezing.

CURWOOD: It seems the pace of human-induced climate disruption is gaining steam, so we called up Jennifer Francis, Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. She studies how the rapidly warming Arctic affects our weather. Jennifer, welcome back to Living on Earth!

FRANCIS: Thank you so much. It's great to be back.

CURWOOD: So it seems like month after month, year after year, there are more extreme weather events happening. How true is that perception?

FRANCIS: It's absolutely true. It's measured not only by scientists like me who study the climate system, but also by companies like insurance companies that really care about these extreme events, because of course, they cost a lot of money. And they end up shelling out a lot of compensation for damages. And so there's absolutely no doubt that we're seeing an increase in the frequency of extreme events of many kinds. Not all kinds, but most of them, I would say.

CURWOOD: So in the Northeast United States, where we're based, we went from below zero temperatures, it seemed like, towards the end of 2022 to shirtsleeve weather. We saw the city of Buffalo get buried under, I don't know if there are measuring sticks for the amount of snow that they got. What's the reason behind such sudden changes and events like that? Suddenly, a bunch of snow being dumped, suddenly the temperature changing?

FRANCIS: Well, you know, pretty much all the weather that we experience around the northern hemisphere in the wintertime is caused by fluctuations in the path of the jet stream. And the jet stream is this river of wind that blows from West to East, high up in the atmosphere where jets fly. And the jet stream really does create all of our weather and steers storms, it steers high pressure areas and low pressure areas. So, whatever is going on with the jet stream is felt by us down on the surface as changing weather. So what happened over the last several weeks, where it caused those big flips and extremes, as you said, first, it was extremely cold. When we experience extreme cold like that, it means that the jet stream has dipped south of us. And when it does that, it's basically the boundary between the cold air to the north, and the warm air to the south. And so when it is south of your location, that cold air from the north can plunge way far south. And in this particular case, it was a very cold airmass that came down from far northern Canada, came down over the whole middle of the country, and caused a lot of problems for places that really aren't used to dealing with the cold. And, you know, it's sort of a flashback to what happened back in February 2021, when Texas and Oklahoma and some of those southern central states got whacked by that very severe cold spell. It was the same kind of thing, it was a big southward dip in the jet stream. So conversely, when that dip goes by your area, you can be in a place where the jet stream swings way north of you. And then that allows the warm air from the South to penetrate maybe much farther north than usual. And in this case, again, it was a very extreme case of the jet stream bringing all this warm air from the south and bathing the Eastern two thirds of the continent in very warm air. So it really just depends on where you are relative to these northward and southward dips in the jet stream. That is what our weather is created by.

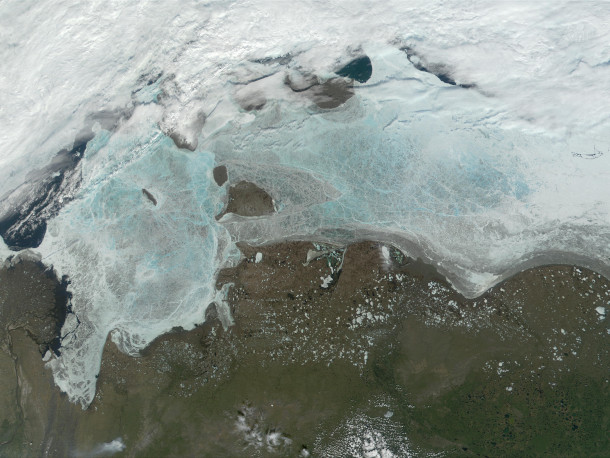

Over the last 40 years, Arctic Ocean surface sea ice has reduced by half. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Now, you've done a fair amount of research on why the jet stream is behaving in such extreme ways, going so much further south than it might have in periods past. And I believe that research is related that to the warming and the formation of Arctic ice. Can you explain what your research tells us?

FRANCIS: Sure. So I should start though, by saying that, you know, the jet stream is a very complicated feature in our atmosphere, our atmosphere is a very chaotic beast, if you will. And there are many factors that can affect the jet stream. So you might know and your listeners might know that right now we are in what we call La Niña conditions. And it's when there's a big pool of colder than normal water extending from, say, the coast of Peru all the way across the Pacific along the equator. The opposite of that is El Niño. And we know that's basically when there's warm water instead of cold water there. And that has a lot of weather implications and it can affect the jet stream. But it's true that my research that I've been doing over the last decade or so, along with a lot of colleagues around the world now, all looking into the various ways that climate change is influencing the path of the jet stream, the strength of the jet stream and therefore weather patterns as well and extreme weather. And one of the factors that we think is a very important one is the fact that the Arctic is now warming about four times faster than the globe as a whole. This has resulted in about half of the sea ice, which is the ice that's floating on the Arctic Ocean, disappearing in the summer, over the last 40 years. So we've literally lost half of the sea ice cover in 40 years. And if you take into account how that ice has thinned, you can multiply the thickness of the ice times this coverage and you get the volume, the volume of the ice has decreased by almost three quarters in that same time period. It's just a huge change to a very important component of the climate system. It's happened over a very rapid period. And there's absolutely no way that a change of that magnitude is not having an impact on the atmosphere and the jet stream. And so the real difficulty in the research now is to figure out exactly how, and it won't be the same in every case, because as I said, there are many factors that affect the jet stream, this being just one. But in a nutshell, what we think is happening because the Arctic is warming so much faster than the rest of the globe, and particularly areas to the south of the Arctic, it's really that north-south temperature difference. So it being warm over the United States, say and much colder in the Arctic, when that temperature difference is large, the winds of the jet stream are strong. And when the winds of the jet stream are strong, it tends to blow relatively, in a straight path from west to east and it circles the whole northern hemisphere. But as we warm the Arctic much, much faster, it means that north-south temperature difference is getting smaller. And when it's small, the winds of the jet stream weaken. And a weaker jet stream is more easily deflected from its west to east path by things like mountain ranges. And even ocean heat waves, is a term that some of your listeners might have heard before, it's basically a blob of very warm water in the ocean. And that can also influence the path of the jet stream. So what we're seeing though, is that the Arctic is warming so fast, we are able to measure weakening of the winds of the jet stream. And we have also been able to measure that the jet stream is now wavier than it used to be, it is taking on these big north-south swings more often than it used to.

CURWOOD: And I think last summer, when people were talking about the huge heat waves that they were talking about double jet streams. Did I hear that, or are my ears not working?

FRANCIS: Well, it's, it's not so much a double jet stream as the jet stream splits into two branches. So I mean, it's the same thing, I guess. But what we see is that oftentimes in the summer, especially now it's happening more often, we're seeing the jet stream split into two branches. So one branch would, say, blow along the Arctic coast, say along the north coast of Europe, for example. And then the other branch would go through the middle of Europe. And this is a summertime phenomenon that we're talking about right now. And when we see this happen in the summer, what happens is the space in between there, those atmospheric features, so high pressure, low pressure, whatever, they don't have any winds to blow them along. So they tend to get very stagnant in one place. And if you happen to be stagnant in a place where there's no rain, the sun's beating down, no clouds, so a high pressure area, then that tends to build up the heat, it dries out the soils, and it leads to these very intense and persistent heat waves. But it can also affect places where it's in the rainy part. So a low pressure area in the same region that's that's basically stuck in place. And that has contributed to some massive flooding in places like Pakistan and other places over the years. So those have been connected to this tendency for the jet stream to split more often during the summertime.

CURWOOD: So the intense weather we're seeing in the wintertime, the intense weather of the summertime, all related to how the jet stream is doing. How much of this sort of change in behavior of the jet stream over this period of time is related to overall warming of the planet?

FRANCIS: Well, I think we should probably back up just a little bit, not every impact of climate change is related to the jet stream itself. There are some very direct connections between the warming globe that we're causing by building up greenhouse gases in the atmosphere through our carbon emissions, and some extreme weather events. So we are clearly warming the globe. And this is directly related to more intense, more long-lived, more frequent heat waves that we've been seeing. So you know, that is a pretty intuitive connection there. That warmer air is also sucking more moisture out of the soil. And so evaporation is increasing everywhere over the oceans and over land and where that evaporation is taking the moisture out of the soil. We're seeing, of course, worse droughts and that has a direct effect on agriculture. So those are two very directly linked weather extremes to climate change. And another aspect of that increased evaporation is that there's now more moisture in the atmosphere, that moisture is absolutely critical, it has a lot to do with how intense a storm gets, how much rain it drops. And that extra water vapor is also a greenhouse gas. So it's exacerbating the heat trapping of the atmosphere. So those are very direct connections between climate change and the kinds of extreme weather events we've been seeing happening much more often. The connections to the jet stream are, I would say, still a very active area of research. And as I said in the beginning, it really depends on what other factors are in play at the same time as, say, the Arctic is warming, or we've got an ocean heat wave, or we have a La Niña. You know, all of these factors play into it. And it's really tough to, you know, disentangle one factor from all the others and say, you know, this particular extreme event was because of that factor, or how much by that factor.

CURWOOD: Welcome to a warming planet. Is that the right title of what's going on?

FRANCIS: Yeah, or another possible title would be the climate crisis is here. You know, it's not for our grandchildren, it is already here. We are already feeling the effects of the warming that's already happened in the climate system, because of our emissions of greenhouse gases and the thickening of this blanket that we're putting around the Earth. So these more intense downpours of rain, more intense, tropical storms, more rapidly intensifying storms, more intense droughts, and long lived droughts, wildfires, these atmospheric rivers that are affecting California this week, all of these things are absolutely symptoms of the changing climate that we've been expecting to see. And here they are, right now, they're happening to us today. They're causing a lot of damage, both in terms of infrastructure, and costs, and lives. And this is the climate crisis. It's already here.

Total precipitation for California from December 26, 2022 to January 11, 2023. (Photo: Weather Prediction Center, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: But wait, the folks in Paris, in 2015 said that we needed to keep it below one and a half degrees centigrade rise in global average temperature, but I think we're only up, what, 1.2 degrees average global temperature?

FRANCIS: That's true. Well, every 100th of a degree that we increase the global temperature, we're going to see that many more extreme events happening. And it's not a hard threshold. It's not that you know, if we can keep it below 1.5, that we're out of the woods, because we're already in the woods, we'll just be deeper into the woods. The warmer it gets, the worse it's going to get. And, you know, 1.5 is a target. It's something that we can aspire to. And I think you know, it's going to be a tough one to, to meet, but it's still possible barely. But as I said, you know, every bit of warming that we can prevent is going to make these extreme events a little less likely.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, I have to mention that some folks would say, there have always been warmer than average winters and colder than average winters and hotter summers and colder summers. And they'll say, well, how much of this is due to natural variability and weather as opposed to disrupting the climate? How would you respond to such questions?

FRANCIS: Well, I would agree that they've always been colder than normal winters colder than normal, summers, wetter, drier, all of those things. But what we see now are trends that are way beyond what is considered natural variability. You know, we've heard the word unprecedented used in extreme events so often in the last couple of years. That means that it's never happened before. And we've seen these unprecedented events unfolding, and clear trends in many kinds of these extreme events. So there's only one kind that is maybe some good news. And that is that we're not breaking cold records as often as we used to. And we're breaking many more high temperature records than we used to. So that kind of goes along with the general warming. But that doesn't mean we still can't get these very extreme cold spells like we've had this winter and also back in 2021, those can still happen. And that's where this very complicated topic of how the jet stream is behaving comes into play, because it isn't just average warming, or average cooling. It's these pulses of cold air that can come down when the jet stream gets into one of these very wavy patterns. So you know, that's another kind of variability, but we're also seeing what looks like the jet stream taking more extreme paths. And this is something that we also expect.

The Arctic is warming three to four times as fast as other parts of the globe. Warmer temperatures will make storms like Merbok much more likely in the future and further exacerbate other ongoing climate hazards such as permafrost thaw, flooding, and erosion.

— Woodwell Arctic (@woodwellarctic) December 6, 2022

(????️: @g_fiske) pic.twitter.com/dadfrkdYxg

CURWOOD: Now we started to see the term weather whiplash, used to describe situations like what we've seen in California or in the Northeast. How is that term defined, if it has, indeed any kind of scientific basis? In fact, what does climate science say about so-called weather whiplash?

FRANCIS: That's a great question because we just published a paper on weather whiplash a few months ago. And there is no, I would say, agreed upon definition of what it really means. But sort of conceptually, it's when you've been in one kind of a weather regime for a while, you get used to, say, above normal temperatures during the winter along the east coast, and all of a sudden, this new airmass moves in, because that wave in the jet stream has passed you by. And all of a sudden, now you're thrown into cold or snowy or very different conditions from what you have been having for the last week or so. And this paper that we've just published, actually takes a look at weather whiplash from a different angle. And that is to look at these continental scale patterns in the jet stream. And measure when they get kind of stuck in one place in one pattern, and then look at when it shifts to a very different pattern. And thinking about that as a weather whiplash, because usually, it's not just one location that experiences it, it's a big shift in the whole atmospheric regime, or the whole pattern across the continent. And so we wanted to characterize it in terms of these, you know, really continental scale shifts, rather than just a sort of ordinary cold front passing through Dallas, Texas, or something like that.

CURWOOD: So in the western US, they've been facing extreme storms and flooding after years of drought, right and wildfire. What's going on there?

FRANCIS: Getting back to this connection to the jet stream, I hope everybody takes away from this discussion that they need to understand that the jet stream is really controlling all the weather that we experience in the wintertime. So what had been happening in the West for a very long time is a tendency for one of these big northward swings in the jet stream to be parked over the West Coast. And that steered most of the storms up into British Columbia and up into Alaska, and away from California and the southwestern states. So they were left high and dry. But now what we're seeing is a very different pattern in the jet stream. We're seeing one of the southward dips just off the west coast. And when we see that happen, just downstream from that big dip in the jet stream is where you get storm development. And so it's been sitting there for days now and developing these very strong storms coming in to the West Coast, there's a lot of cold air coming down from the Arctic, fueling these storms, and a lot of moisture over the very warm tropical oceans that's being sucked into the storms as well. So, you know, any storm that forms today is forming in a different atmosphere from what it was a few decades ago. And so it has more moisture to work with, which means it's going to dump more precipitation, that moisture is also a source of energy for the storm to feed on and become more intense. And so as I said, you know, yes, storms have always hit California. We've always had these kinds of patterns. But we're seeing them on steroids now. We're seeing them fueled by more moisture, by more heat in the oceans. And so it's not just your run of the mill storm anymore. It's this extreme flooding event that California is still dealing with.

Jennifer Francis is a Senior Scientist at Woodwell Climate Research Center. (Photo: Courtesy of Woodwell Climate Research Center)

CURWOOD: There was a paper published in Nature Climate Change earlier this year that said it's been 1200 years since the American West has had such a prolonged, profound drought. And the decades-long drought that has gripped the West since the year 2000 is the driest 22 year period since at least AD 800. What's going on there?

FRANCIS: Yeah, it goes back to what I was saying that you know, the air is warmer now. And it is more able to suck that moisture out of the soil. Once the soil dries out, that is a big deal, because when soil has moisture in it, that heat that it absorbs from the sun goes into evaporating that moisture so the soil doesn't warm up very much. But once it's dry, all of that energy from the sun goes into heat, pure heat. And then that starts to kind of start a vicious cycle in the atmosphere, when you get the soil getting really hot, it tends to heat the air even more, it builds up a bubble of hot air over that dry, hot soil. And that tends to drive the jet stream even farther northward, it creates what has been called a heat dome. These heat domes are really formed by that extra warming that's happening at the surface and basically building a bubble of hot air over that region which also tends to steer any storms that might come in up to the north and away from that area so that it tends to make the dry hot conditions last a lot longer. And that's kind of what we've been seeing. The patterns in the upper atmosphere have been tending to steer the storms away from California. And that just kind of builds on itself after a while. And fortunately, that cycle has broken, at least temporarily and the reservoirs are getting filled. But yes, this is a very severe, widespread, extreme drought that has been affecting many of the western states and there's really no human precedent for it.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Francis is a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Thanks so much for taking time with us today.

FRANCIS: Happy to be here. Thank you, too.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “The Toll Extreme Weather Took in the U.S. During 2022, by the Numbers”

- Vox.com | “Welcome to the Era of Weather Whiplash”

- Jennifer Francis at the Woodwell Climate Research Center

[MUSIC: Rob Van Bavel, “De Tor Ahead” on Time For Ballads – The Maene Sessions, Rob Van Bavel]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Rescuers saved thousands of bats felled by the holiday season cold snap in Texas. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rob Van Bavel, “De Tor Ahead” on Time For Ballads – The Maene Sessions, Rob Van Bavel]

Beyond the Headlines

A new study finds that the greenery in New York City absorbs as much carbon as all the traffic in the city emits on many summer days. (Photo: Neerav Bhatt, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

And with me on the line from Atlanta, Georgia is environmental journalist Peter Dykstra. Hi there, Peter, how are you doing? What do you have for a look beyond this week's headlines for us?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We're gonna start with a little bit of good news about the greenery in cities. There was a study that appeared in the journal 'Environmental Research Letters', carried out by Columbia University, and found that on many summer days, about 40% of greenhouse gases emitted in New York City, were offset by the city's greenery. Essentially, they offset all of the traffic emissions.

CURWOOD: Hmm. So that works great in the summer, as you say, Peter, but what about the winter because those cars and cabs and all that stuff keep going even when the leaves are gone from the trees?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, temperate cities around the world are all like that they lose much of their carbon emissions-absorbing ability in the wintertime. But at least in summer, not just big parks like Central Park and Van Cortlandt Park. But all the little backyard gardens and little patches of greenery throughout the city, do more than we had ever given them credit for, not only making New York a greener place, but greenery has shown in other research, that it makes New York a happier place, and other cities, and a less asthmatic place.

CURWOOD: And I imagine those trees as they absorb the CO2 are also soaking up some of the toxic chemicals that come out of the tailpipes of cars. So it's nice to get a bit of good news anyway, Peter, thank you. What else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: I wouldn't say that it's been beyond the headlines to discuss the new party in power in the House of Representatives, the Republicans, not being able to agree on their own Speaker of the House. But there are a couple of things that come out in terms of climate. One is that the hardliners on the Republican side in Congress, who are not only hardliners on conservative issues, but they're also climate deniers, they got more than their collective weight should have allowed them to bargain for in the Speaker's race. They're also part of the "drill baby drill" movement starting in 2008 that was associated with Sarah Palin's vice presidential campaign. Steve Scalise, generally considered to be the second most powerful Republican in the House of Representatives is also a big oil and gas man.

Kevin McCarthy was elected house speaker after a long battle among Republicans, hinting at the difficulty of passing climate policy in the coming years. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, of course, the Senate stays democratic and that was, of course, the folks along with the Democratic House that passed the Inflation Reduction Act otherwise known as the largest measure to address the climate in this country. But the House and the Senate, I guess, aren't going to agree on much in these next couple of years. What does that do for the climate situation?

DYKSTRA: It certainly lessens any promise that collectively Congress is going to get more serious about climate change. Let us not forget that the Republicans are also looking at a majority of their appointees to the Supreme Court and we'll have some cases coming before the Supreme Court in the next few years regarding climate change as well.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Let's take a look back in history, something about Republicans?

DYKSTRA: In January of 1908, more than a century ago, when a Republican was the most prominent conservationist in the country, that, of course, being Teddy Roosevelt, he made the Grand Canyon a national monument. It's a precursor to making the Grand Canyon a national park, that was actually done in 1919 by President Woodrow Wilson. Both Wilson, the Democrat, and Teddy Roosevelt, the Republican, were concerned that mining interests were beginning to encroach on areas not just near the canyon, but near sacred sites for many Native American tribes. And bear in mind that back in 1908, Arizona wasn't even a state yet. It didn't become a state for another four years.

The Grand Canyon in Arizona was declared a national monument by Theodore Roosevelt on January 11th, 1908. (Photo: Bernard Spragg, Picryl, public domain)

CURWOOD: And I believe now the world recognizes the Grand Canyon as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. And you have to say, Peter, when you go and you stand on the rim of the Grand Canyon, or if you make your way down it as I have a couple of times. It's just so powerfully awesome.

DYKSTRA: Who wouldn't recognize the Grand Canyon, one of the absolute breathtaking wonders of the world. But the Grand Canyon was finally recognized by Roosevelt in 1908 as an area to be treasured and protected.

CURWOOD: Well, we can be grateful for that. Peter Dykstra is an environmental journalist in Atlanta, Georgia. I want to thank you for taking the time with us today and we will talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve, thanks a lot and I'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage that's LOE.org.

Related links:

- Yale Environment 360 | “New York City Greenery Absorbing All Traffic Emissions on Many Summer Days”

- E&E News | “3 Climate Takeaways from the GOP Speaker Meltdown”

- History.com | “Theodore Roosevelt Makes Grand Canyon a National Monument”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: White-Browed Coucal

The white-browed coucal perches on a twig. (Photo: Francesco Veronesi, CC)

BASCOMB: We travel now to Sub Saharan Africa with this week’s birdnote and the white crowned coucal.

BirdNote®

White-browed Coucal

[White-browed Coucal “bubbling” call]

This call, likened to the sound of water running out of a bottle, is common in many parts of Africa. It usually comes from a dense thicket—its origin a puzzle—and is most likely to be heard at dawn and dusk. But if you watch long enough, you might be rewarded with a sight of the bird that makes this call. [White-browed Coucal call]

It’s a White-browed Coucal (pronounced coo-kle as in coo, not cookie), a streaky bird with red eyes, red-brown wings, a long black tail, and a white stripe over each eye. “Streaky and sneaky” best describes these birds, as you’ll be lucky to see one. Yet, because their habitat is so dense, dew often dampens their feathers. And when that happens, they hop to the top of a bush and spread their wings and tail to dry in the morning sun.

[White-browed Coucal call]

Coucals are members of the cuckoo family, but instead of laying eggs in the nests of other birds as many cuckoos do, coucals build their own large nest. They lay four eggs and raise their own young.

The white-browed coucal bows its head. (Photo: Harald Olsen, CC)

[White-browed Coucal call]

Support for BirdNote comes from the Cornell Lab’s Bird Academy, with online courses that share the wonder and joy of birds. More at All About Birds dot org.

###

Written by Dennis Paulson

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Call of the White-crowed Coucal recorded by M.E.W. North.

South African ambient recorded and provided by Martyn Stewart, naturesound.org

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org October 2016/2020 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# 101507coucalKPLU coucal-01b

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/white-browed-coucal

BASCOMB: For photos strut on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org

Related link:

More on the White-Browed Coucal

[MUSIC: Rob Van Bavel, “De Tor Ahead” on Time For Ballads – The Maene Sessions, Rob Van Bavel]

Rescuing Bats from Extreme Cold

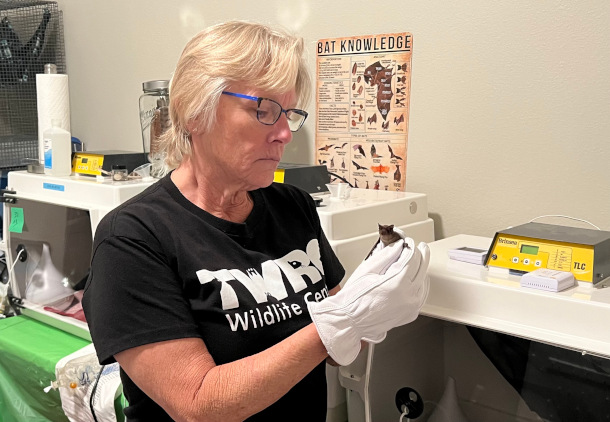

A Mexican free tailed bat in the care of Bat World Sanctuary. Bat World Sanctuary was key in aiding Wary Warwick rescue the Mexican free tailed bats. Their volunteer helped Mary sort through the healthy bats vs the injured ones who needed critical care. Bat World Sanctuary made two 12 hour round trips to bring about 120 bats to Bat World Sanctuary; they could treat injuries and provide care until they are ready to be released. Some of these bats will require lifetime care by Bat World Sanctuary due to their injuries. (Photo: Courtesy of Bat World Sanctuary)

CURWOOD: This winter’s extreme weather delivered an unusual cold snap to parts of Texas, bringing below freezing temperatures to Houston. That’s cold that some local wildlife, including bats, just can’t deal with unless they get help as Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran learned from a local wildlife rehabilitator.

WARWICK: I looked down and these bats look like large chunks of bark. They didn't look like a living organism, you know, they were just kind of, they look dehydrated.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Fission Forming,” Trailhead, Blue Dot Studios 2021]

BELTRAN: A few days before Christmas, Mary Warwick was walking under the Waugh Bridge in Houston and noticed hundreds of tiny Mexican Free Tailed bats lying on the ground. The fuzzy brown bats weighed just a few ounces and had fallen from the bridge above to the cold ground below.

WARWICK: You might not even realize there were a bat if you didn't know there was a bat colony above you.

Mexican free tailed bats recovering from the Texas cold snap next to a blanket to keep them warm. (Photo: Courtesy of Mary Warwick)

BELTRAN: Mary Warwick is the Wildlife Director of the Houston Humane Society, which teamed up with an organization called Bat World Sanctuary to help the hypothermic bats. As a wildlife rehabilitator, she’s already been vaccinated against rabies.

So she sprang into action to nurse the first 138 bats she found back to health.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Night Light,” Nursery, Blue Dot Studios 2020]

WARWICK: I didn't have anything really with me at the time. So I just went back to my car and found a box that was holding other things and dumped it out and got some Kleenex and put it in the bottom of the box and went back down. And this was during the day and put all the bats in the box. And then it was about 22 degrees out at that point. And so I put them on my seat and turned my seat on the heat warmer and then headed to where I live which is about 40 minutes away. And in about 15 minutes or so you could kind of see them starting to move a little bit, little feet stretching and stuff like that so that's a good sign.

[BAT SFX]

WARWICK: So with any injured wildlife, they need two things immediately. They need heat support and they need hydration so they can't use food in their gut until they're warm and hydrated. So those are always the two things we do first so we get them warm and then we give them some subcutaneous fluids under their skin with a little tiny needle and syringe and get them nice and hydrated. And after that you can start force feeding them and things. Bats eat on the wings, so they fly to catch insects. If you put a bowl of insects in front of them, they're not going to know what to do and they're typically not the insects they would eat anyway, like mealworms, they're not what they would normally eat. So you have to force feed them. So it can be very labor intensive.

The freezing December 2022 temperatures caused Mexican free tailed bats found in Houston’s Waugh bridge to go into hypothermic shock, lose their grip from the bridge and fall to the ground. Some of the bats needed to be put in an incubator for recovery (pictured above). (Photo: Courtesy of Mary Warwick)

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Edge of the Woods,” The Caravan, Blue Dot Studios 2022]

BELTRAN: The Houston Humane Society posted on social media that Mary was rescuing the bats by herself. But after that she wasn’t alone for long.

WARWICK: I think this is one of the most organic things I’ve been involved with in a long time because when people started hearing that I had picked up bats, they started going out on their own and picking up bats and then I was getting Facebook messages like I've got 50 bats or I've got 20 bats or whatever, can you get somebody to pick them up and so it just kind of became like an old fashioned phone tree kind of thing where everybody's reaching out and calling this person or that person. It was just the most hodgepodgey thing.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Edge of the Woods,” The Caravan, Blue Dot Studios 2022]

WARWICK: When I had 100 or 200, or something like that, myself and the people from Bat World could kind of handle that. And then we picked up 929 bats from another bridge the second night. So that really magnified the number of animals we had to take care of. And so it's impossible for us to force feed 929 bats plus the other ones we had.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Night Light,” Nursery, Blue Dot Studios 2020]

Around 1500 bats were kept safely inside several dog kennels in Mary Warwick’s attic as they recovered from hypothermic shock. (Photo: Courtesy of Mary Warwick)

WARWICK: So we decided that rather than keep them warm and their metabolism up where they would need to use glucose. We decided to cool them down so that they wouldn't freeze but they would kind of go into hibernation. It's called torpor, where their metabolism slows down so they would still need to drink every once in a while but they would be okay without food. And so my attic is warm enough that they wouldn't freeze but cold enough that they would slow down.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Night Light,” Nursery, Blue Dot Studios 2020]

BELTRAN: Mary had about 1500 recovering bats in large dog kennels in her attic.

WARWICK: So they were there Christmas day when I had family over for dinner, and coming in and out of the front of the house you could hear them through the attic door and they talk a lot because they're so social and so even though their metabolism was slowed down, they weren't in hibernation. They were still kind of awake and chatting to each other kind of like a slumber party. You know, everybody's just kind of laying around talking. They were just up there chatting away and they will get quieter sometimes and then louder other times. It's a great little sound to hear.

[Bat SFX]

An estimated 250,000 Mexican free-tailed bats call the bridge in Houston Texas home. (Photo: Ann Froschauer, USFWS, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: After a few days of recovering in the dog kennels in Mary’s attic, the bats were not only chatting but flapping around and ready for release.

Mary says this wasn’t the first time bats have struggled with cold weather in recent years, and it is unlikely to be the last.

WARWICK: Since 2019, this is the third time this has happened with bats. We had another freeze in 2022. But it was so hard that we were trying to save human lives at that point, people perished in that freeze. So to tell you the honest truth, I didn't even think about bats. I was worried about my mother and you know, things like that. And so here it's happened again already. And so, you know, it's happening more often, more often. And then not only do we have the problem of that in the winter, but in the summer season when we can have hurricanes or big tropical storms which are getting worse, you know the bayou floods all the way up to the bridge and the bats can drown. So they are just really living on the edge now, and, and all of these things are tied to climate change.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Fern and Andy,” Love and Weasel, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

BELTRAN: Thanks to Mary Warwick and a team of volunteers more than 1600 bats were saved from freezing to death in the recent cold snap. It’s a network of people the bats will likely need to rely on again, as climate change continues to bring unusually cold weather to Texas.

Mary Warwick, wildlife director for the Houston Humane Society, holds a Mexican free-tailed bat as it recovers from the 2022 Texas winter freeze. (Photo: Courtesy of Mary Warwick)

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Fern and Andy,” Love and Weasel, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran with Mary Warwick the Wildlife Director of the Houston Humane Society. To see a video of the rescued bats in Mary Warwick’s attic head on over to the Living on Earth Website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the bats under Waugh Drive bridge

- Houston Chronicle “ Hundreds of (now unfrozen) Houston bats successfully released under Waugh Bridge"

- Learn more about Houston Humane Society

- Learn more about Bat World Sanctuary

- Watch the Mexican free-tailed bats recover in Mary Warwick’s attic

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Fern and Andy,” Love and Weasel, Blue Dot Studios 2017]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth