March 8, 2024

Air Date: March 8, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Vital Ocean Current Threatens Collapse

/ Seth BorensteinView the page for this story

As the climate crisis intensifies, a vital ocean current that includes the Gulf Stream seems to be falling apart, and thus could fail its mission to moderate the climate by bringing heat north from the tropics and cold back south. AP science and environment reporter Seth Borenstein joins Host Steve Curwood to explain the latest research and the potentially disastrous shutdown of this current. (09:38)

Plastic Bag Bans and Pushback

View the page for this story

A decade ago California became the first US state to ban single-use plastic bags, and eleven states followed suit. But some 18 other states have gone in the opposite direction and even blocked local cities and towns from prohibiting single use plastic bags. Judith Enck, President of Beyond Plastics and a former EPA Regional Administrator, joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss successes and setbacks for efforts to minimize plastic bag waste. (08:39)

Fracking Under Ohio State Parks

/ Kathiann KowalskiView the page for this story

In Ohio, drilling and fracking may soon begin underneath Salt Fork State Park, Ohio’s largest, as well as the Valley Run and Zepernick State Wildlife Areas, despite legal attempts to halt the extraction. Energy News Network reporter Kathiann Kowalski joins Host Steve Curwood to describe concerns about the potential risks of drilling under these lands. (08:29)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Paloma Beltran discuss the FDA’s announcement that PFAS used to grease-proof food packaging is no longer being used in the U.S. Also, the new offshore wind farm Vineyard Wind now has 5 of 62 planned turbines up and running and helping power the Massachusetts grid. And in history, they look back to when Monty Python met bat biology, with the 2008 documenting of pipistrelle bats living inside the castle of a foul-mouthed Frenchman played by John Cleese. (04:41)

Ross Gay's Book of (More) Delights

View the page for this story

Poet and essayist Ross Gay is back with a follow up to his 2019 Book of Delights, loaded with moments of good that sprout amid our troubles. He joins Host Steve Curwood to share readings from his new Book of (More) Delights celebrating simple joys such as clothes on a clothesline, garlic sprouting, and dandelion abundance. (15:13)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240308 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Seth Borenstein, Judith Enck, Ross Gay, Kathiann Kowalski

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The Gulf Stream is part of a vital ocean current called the AMOC that circulates heat around the planet. And it could shut down in decades and lead to sudden climate disruption.

BORENSTEIN: For much of climate change, there is no cliff you fall off of, but AMOC is one of those cases where scientists worry about, sort of like an on-off button.

BELTRAN: Also, more delights from poet Ross Gay.

GAY: It is truly overnight sometimes it seems that the dandelions put on their crowns, and just like that, the world is suddenly brighter, more abundant, more possible— this, of course, if you, like me, adore the dandelion, see their un-martialed ranks suddenly outflanking the gloom, outflowering the doom.

BELTRAN: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Vital Ocean Current Threatens Collapse

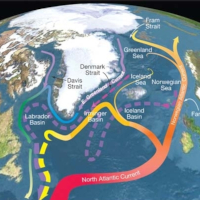

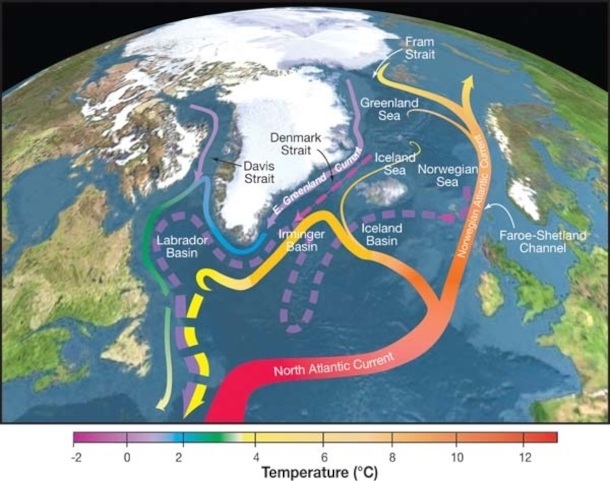

The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, also known as AMOC, influences weather patterns on land as well as ocean salinity and temperature. (Photo: R. Curry, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution / Science / USGCRP, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

As the climate crisis intensifies, a vital ocean current that includes the Gulf Stream seems to be falling apart, and thus could fail its mission to moderate the climate by bringing heat north from the tropics and cold back south. For decades, scientists have been studying the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, also known as the AMOC, in the hopes of figuring out just how soon its collapse might come. And as AP science and environment reporter Seth Borenstein tells us, the latest data do not bode well. Seth, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BORENSTEIN: Thanks for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the physics of all of this. How exactly does an ocean current like this work?

BORENSTEIN: Actually, if you think about it, it's something we can all understand. It's saltwater versus freshwater. Saltwater is more dense, freshwater isn't. The saltier it is, the more it moves, and there's the problem: it's getting less salty. Or you could call it more fresh, if you prefer. What's happening is we're seeing a lot of melt in Greenland. And that water that is melting from the ice sheets, it's fresh. And if it's a giant conveyor belt, the engine is just off of Greenland. And it's pouring more freshwater than it used to get there. So it's sort of like watering down your gas tank.

CURWOOD: Hm. That's not a good idea. I mean, your car does not like water in its gasoline.

BORENSTEIN: So this has happened before. I mean, this is, you know, we've seen it slow down before, millennia ago, long time ago. Because we've also seen ice sheets melt before. It's melted naturally, this is not natural. This is from human-caused climate change causing a dramatic melt in Greenland, as well as other places. But Greenland has a giant ice sheet. And you can go there and actually sea melting occurring before your eyes. And that is freshwater going in there.

The AMOC slowdown is a result of melting glaciers, primarily in Greenland, releasing freshwater into the ocean. This disrupts the salinity levels, which in turn affects the rate at which the water circulates. (Photo: Saskia Madlener, NASA, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, for years, I think probably decades I should say, people like Wallace Broecker at Columbia University were saying what he called the North Atlantic Conveyor Belt, which we now call the AMOC, the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. He said this thing, if we keep warming the planet, we're going to imperil the functionality of this. And in fact, he said, even way back when, it's starting to slow down. So scientists have been worried about this for quite a while. What new data do we have now, Seth? What's been presented to us?

BORENSTEIN: Well, first off, scientists have worried for about this for a long while, I've been covering climate change, like you, for more than a quarter century. And strangely enough, that made me much more skeptical. Because in the late 90s, there was a lot of study about the AMOC slowing down. And then the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and others said, whoa, slow down on this slowdown stuff. It's not as bad as it looks. It's centuries away. It's an issue, but it's not an issue for right now. And it's happening slowly. But this was about the time, if you remember the movie The Day After Tomorrow, which is horribly fictional, you know, it is by no means science. But that is sort of the science it is very loosely based on. So you have this. And like others in the late 90s, early 2000s, I was writing about it. And then, you know, I was sort of convinced by mainstream scientists who said, you know, this is not as bad as we feared. And so I personally have actually been skeptical and waiting. But in the last three, four years, we're seeing more data. And that's because starting in 2004, scientists started measuring it regularly, which they didn't do. So before, it was based on a lot of observations that were not as good and a lot of modeling and physics. Now it's based on data—and modeling and physics. And so there have been studies in the last two years. One in 2023. And then one in February, that came out and said, we are seeing slowing down. Not only are we seeing slowing down, this latest study that came out last month, said, okay, here's what we should be looking for. Here's sort of this key measurement. And it's an awfully complicated measurement, and it's based on salinity, and it's based on temperature. And they're saying, when we do computer models and see everything go to hell, essentially, fall off a cliff, they're showing we're getting closer to that. So these studies the last couple of years are saying, hey, it may not be centuries, it may be decades or generations away. No one's saying it's tomorrow. No one is saying it's next year. But it's looking closer. It's still, at least for me, and maybe you and many listeners, not in our lifetime, but it could be in lifetime with some of the younger people. And if it happens, then boy, watch out.

Western Europe experiences a warmer climate than other regions at a similar latitude due to the warm waters transported Northwards by the Gulf Stream. A collapse of the AMOC would plunge temperatures in the region by an estimated 9 to 27 degrees Celsius. Shown here is the aftermath of Storm Emma in Dublin, which brought abnormally high snowfall of nearly 2 feet. An AMOC collapse would make storms like this increasingly common and extreme. (Photo: William Murphy, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, so what will be the consequences of the AMOC collapse? How would it be felt around the world?

BORENSTEIN: Well, if you think about it, remember, this is distributing energy. Basically, it's taking warmth from the southern hemisphere and the Americas to Europe and the northern hemisphere. If that shuts down, what you would see is the northern hemisphere get colder, and quickly. And you would see the southern hemisphere get warmer, and quickly. The biggest effect, scientists say, of an AMOC collapse, is incredibly colder temperatures in Europe and England and the United Kingdom area. You would see sea level rises beyond climate change, and warming in the southern hemisphere. The effects in North America, certainly not as extreme as they are in Europe. But it is a dramatic change in climate. And strangely enough, if and when it happens, you have what is considered global warming causing icier conditions, frigid conditions in parts of Europe. But that is part of climate change.

CURWOOD: Climate disruption, some call it.

BORENSTEIN: Yes.

CURWOOD: So now let's talk a little bit of the math here. So as I understand it, the AMOC circulation has decreased some since the 1950s. What's the rate of change? Is it just off a certain amount? Or is the decrease increasing?

BORENSTEIN: In other words, are we seeing an acceleration of the slowdown?

CURWOOD: Exactly.

BORENSTEIN: Which is an odd phrase, if you think about it.

CURWOOD: It is! It’s so hard, yes!

BORENSTEIN: The most recent study said that it is slowing down more, or we're seeing it's getting worse. So that's why the concerns are growing. They're seeing this rate of slowing increase.

CURWOOD: But the slowdown isn't all that existential for civilization, right? It's the sudden stop. I mean, it's sort of a binary thing. Either the thing is going or it's not, if I understand correctly.

BORENSTEIN: Right, yeah, that is the concern. So much of climate change is not binary. Yes, there is a temperature at which humans cannot live, but we're not really near that temperature. Things get worse as temperatures grow, but for much of climate change, there is no cliff you fall off. But AMOC is one of those cases where really what's concerning is sort of like an on/off button. And right now it's slowing, but it's not off. So we aren't seeing the severe cold, the severe impacts of a shutdown.

CURWOOD: Seth, to what extent is this looming shutdown of AMOC baked in to the emissions that we already have? The amount of carbon dioxide that's already in the atmosphere from human activities? And we're just looking at the date that this might happen, as opposed to the possibility that well, maybe if we stopped emissions it might not happen?

Seth Borenstein is a science writer with the Climate and Environment team at the Associated Press. (Photo: Courtesy of Seth Borenstein)

BORENSTEIN: That's a great question. So you have to go back to the engine. And you basically have to go back to Greenland and say, okay, can we stop this melt, dumping the cold water in it? And unfortunately, that's not the only thing, because this whole slowdown is a feedback loop. A lot of glacial melt, they have said, is now inevitable. We have gotten to that point, but not everything. And the one thing to look at is emissions have changed. 25 years ago, we were looking at a world of four or five degrees Celsius warming. Now we're looking at a world of two to three. Is that enough to arrest? To be honest, just gonna say it, I don't know. I'm not sure anyone really knows. It's not overly promising.

CURWOOD: Seth Borenstein is a science writer with the Climate and Environment Team at the Associated Press. Thank you for taking the time with us today, Seth.

BORENSTEIN: It was my pleasure. Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Associated Press | “Ocean System That Moves Heat Gets Closer to Collapse, Which Could Cause Weather Chaos, Study Says”

- Seth Borenstein’s Associated Press page

[MUSIC: Kendol Bacchus, “Deep River” Traditional African-American]

BELTRAN: After the break, the state of Ohio moves to frack for oil and gas from under its largest state park. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: New Orleans Nightcrawlers, “Keep on Gwine” on A Celebration of New Orleans Music, by Mel Lastie, Rounder Records and Marsalis Music]

Plastic Bag Bans and Pushback

A “loophole” in a 2014 California law banning single-use plastic bags at checkout allowed slightly thicker plastic bags to be used instead, leading to more plastic bag pollution by weight. California lawmakers have now introduced a new bill to ban all plastic bags at checkout. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

A decade ago, California became the first US state to ban single-use plastic bags, and 11 states as well as some territories followed suit. But some 18 other states have gone in the opposite direction and even blocked local cities and towns from prohibiting single-use plastic bags. And now Florida appears ready to join them, with a proposed statewide measure to bar local cities and towns from banning single-use plastic items. Against that trend there is now a proposal in California to update its pioneering law and eliminate loopholes that have apparently led to more plastic waste, not less. Here to discuss is Judith Enck, former EPA Regional Administrator and President of Beyond Plastics. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Judith!

ENCK: I always love being on Living on Earth. Thank you.

BELTRAN: We always love to have you. So I understand that legislators in California are now trying to correct or fix legislation from 2014 that banned single-use plastic bags in the state. What was the substance of that original legislation and in what ways did it not turn out as planned?

ENCK: Well, the public is really tired of seeing plastic bags everywhere in our communities. You look up in trees, you see plastic bags, you see it littered at beaches and parks. And so the state of California actually went first and passed a statewide ban to prohibit supermarkets and retail stores from handing out single-use plastic bags. Because they went first, they didn't have the benefit of knowing about mistakes in drafting the law. And unfortunately, they made a mistake, and they only banned thin film bags. And then the response from supermarkets and plastic bag makers were to then sell thicker single-use plastic bags, and kind of mislead the public and try to get people to think that these were actually reusable bags when most of them really weren't. So in fact, it made the status quo worse. We went from millions of thin plastic bags to millions of thick plastic bags that were typically only used once or twice. Thankfully, California lawmakers recognized that the original plastic bag ban is not working well at all. And so they've introduced a bill to fix it and not have it just say that they're banning thin film plastic bags, but all plastic bags, and that's the common-sense way to approach it. That's what the state of New York and other states have done.

New Jersey's single-use plastics reduction law, NJ SB 864 / AB 1978 bans both plastic and paper bags at supermarket checkouts. Some consumers opt for bringing their own reusable bags like the ones pictured above. (Photo: Tim Samoff, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: So you mentioned New York—what are some of the states that have made progress on plastic bag pollution, and that California might look up to as a model?

ENCK: I would look to New York and New Jersey as good models to reduce plastic bag pollution. The New York law bans all plastic bags at retail checkouts, full stop. You're not supposed to be receiving any kind of plastic bag whatsoever. And in New Jersey, we have that same law. But New Jersey went a step even further to promote reusable bags by also banning paper bags at the checkout, which was a surprise. And that initiative actually came from the supermarket companies. They opposed the original plastic bag ban. But once they saw that New Jersey lawmakers were going to pass it into law, they were worried that many consumers might not bring reusable bags and would ask for paper bags, which are more expensive than plastic bags. So in a twist, the supermarket lobby said, don't just ban plastic bags—if you're going to do that, ban paper bags as well. And that is the law in New Jersey. And so you've seen a very significant shift toward consumers consistently bringing their own reusable bags to the store.

BELTRAN: So what has been the plastic industry's response to these plastic bag bans?

A tracking study by ABC News found that plastic bags dropped off for recycling often end up in landfills or incinerators. (Photo: A.Davey, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

ENCK: Oh, the plastic industry always opposes these plastic bag bans, or they try to make them weaker. The other thing they've done in some states is adopt state laws prohibiting local governments from banning plastic bags. It's always interesting to watch the trajectory toward when you get a statewide plastic bag ban. It often happens first at the city or municipal level, and then it trickles up to the state level. And whether it's your city council, or your state legislature, if they have proposed anything to reduce plastic bag pollution, the plastics industry shows up in force fighting these proposals. The excuse they use on why we shouldn't ban plastic bags is they say we can just recycle plastic bags. But plastic bag recycling has been an abysmal failure. There have been some journalism projects whereby little electronic trackers were put inside plastic bags that you drop off in your supermarket recycling bin, and oftentimes the plastic bags are tracked to landfills or incinerators. So I'm really losing confidence in any ability to even recycle single-use plastic bags. Once states adopt these laws, using reusable bags just becomes second nature. So it's just a matter of passing a good law, no loopholes like the California law, strict enforcement. And we save literally hundreds of millions of plastic bags in states every single year.

BELTRAN: Yeah. And speaking about local decision making on plastic issues, in Florida, the state legislature is working on a law known as "ban on bans" that will impact local decision making on plastic issues. Can you tell me more about that?

Judith Enck is president of Beyond Plastics and former Regional Administrator for Region 2 of the EPA. (Photo: Courtesy of Judith Enck)

ENCK: Yes. This is a very sinister move by the plastics industry. They know that the public is tired of seeing plastic litter all over communities, entering rivers and the ocean, affecting our own health. And so there's a real interesting and strong grassroots movement to reduce plastics, for many reasons—climate change reasons, environmental justice reasons, health reasons, and a realization that plastic recycling mostly doesn't work. So at the local level, many volunteers come together, they petition their city council or their county government. And they want to adapt a local plastic bag ban, or perhaps a ban on polystyrene foam food containers. Another popular move is something called "skip the stuff." So when you order takeout food, you don't automatically get all the plastic utensils and condiments and straws. So we're seeing this growing movement against plastic pollution all over the country. So the reaction by some state legislators—at the request of the plastics, chemical and fossil fuel lobbyists—is to adopt what's called a ban on bans. So in Florida, they are considering adopting a law that says local communities cannot adopt local laws dealing with plastics. These bans on bans have been adopted in at least 18 states, including states like Texas and Oklahoma. And they sure seem to be anti-democratic. You have the state government telling local government they cannot act to protect the environment and health in their communities. It's a shrewd move. And it's really unfortunate that state lawmakers and governors are blocking progress at the local level to reduce plastic pollution.

BELTRAN: Judith Enck is a former EPA Regional Administrator and president of Beyond Plastics. Thank you so much for joining us.

ENCK: My pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- Check out the list of local bag bans in California

- Los Angeles Times | “California’s Plastic Bag Ban Is Failing. Here’s Why”

- Learn more about Judith Enck

- Learn more about Beyond Plastics

- ABC News | “We Put Dozens of Trackers in Plastic Bags for Recycling. Many Were Trashed.”

- Read about New Jersey’s Legislation Banning Single-Use Paper and Plastic Bags

[MUSIC: Instrumental City, “Firework (Orchestral Version)" Original by Katy Perry: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pEDBjydXRTw]

Fracking Under Ohio State Parks

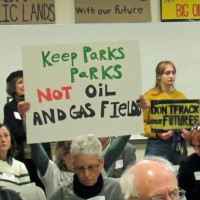

Protesters attended a meeting in November, when the Oil and Gas Land Management Commission voted to allow drilling and fracking under Salt Fork State Park, Valley Run Wildlife Area, and Zepernick Wildlife Area. (Photo: Cathy Cowan Becker/ Save Ohio Parks)

CURWOOD: State parks and wildlife areas are spaces for nature that we humans can enjoy as well. But in Ohio, drilling and fracking may soon begin underneath some treasured places. The Ohio Oil and Gas [Land] Management Commission recently selected two companies to drill under Salt Fork State Park, Ohio’s largest, as well as the Valley Run and Zepernick State Wildlife Areas. Citizens groups have filed legal actions to block the extraction, but one has already been dismissed while another is still pending. The Ohio Department of Natural Resources could allow drilling and fracking under these parks to begin as early as this spring. Kathiann Kowalski covers the state of Ohio for Energy News Network. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kathi!

KOWALSKI: Glad to be here. Thank you.

CURWOOD: Kathi, talk to me about these areas in Ohio under which drilling and fracking might soon start. What are these places like?

KOWALSKI: They're lovely. Salt Fork Park is the largest state park in Ohio. It's more than 17,000 acres, mostly wooded. It's in Guernsey County, which is kind of the foothills of Appalachia. There's a large lake there, hiking trails, a lodge, there's cabins. It's just a great place for people in the area to go and experience nature. It's also a place that draws visitors from across the whole state. I'm actually planning to go there for an overnight stay after Easter.

Salt Fork State Park is the largest state park in Ohio with around 22,000 acres of land. (Photo: Ohio Environmental Council)

CURWOOD: And I guess there's some wildlife areas also in this part of Appalachia that fracking might start?

KOWALSKI: Yeah, there's the Valley Run Wildlife Area in Carroll County. That's 304 acres. It's mostly wooded with a small stream. There's the Zepernick Wildlife Area, up in Columbiana County, and that's 521 acres. And that's also got a lake and a lot of woods, and people do hunting and fishing and birding. Guernsey County, where Salt Fork Park is, and Carroll County where Valley Run is, are two of the top seven oil and gas producing counties in the state of Ohio. So that explains why the industry has an interest in drilling for part of the land there where it hasn't previously been drilling.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the potential consequences of drilling and fracking in these areas. What are the opponents to this worried about here?

Valley Run Wildlife Area. (Photo: Courtesy of Melinda Zemper/Save Ohio Parks)

KOWALSKI: Well, the opponents are worried about air emissions in the area, they're worried about noise and light and extra traffic and additional industrial development while the drilling is going on. For example, you will have water being brought in to be mixed with chemicals for purposes of fracking. And that requires millions of gallons of fluids. And they're also just worried about possible accidents, possible spills of liquids. The actual drilling will take place outside the park in these instances. So it will be what they call laterals, horizontal piping coming in underneath the ground, a couple of thousand feet down. But anything that goes on on the surface, even if it's just outside the boundaries of the park, has the potential to affect the air, the groundwater, and the surface water there.

CURWOOD: What about concerns that there may need to be emergency evacuations? How often do those happen in conjunction with fracking?

KOWALSKI: There have been a handful of emergency evacuations over the last five years. But they do happen. They're rare. But when they have happened, usually you'll have people within half a mile or a mile having to get out of the way. And when we looked at accident data last year, the industry's position was well, gee, there were only a few instances that rose to the category of being major incidents. That means we're doing a good job. But the citizens groups were saying, wait a minute, even a handful of major incidents is too much when you're talking about something in or near a state park or wildlife area.

Zepernick Wildlife Area. (Photo: Courtesy of Melinda Zemper/Save Ohio Parks)

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, some of the opponents are opposing this on the grounds of hey, how smart is this in the context of climate change? What are they telling you?

KOWALSKI: They're saying it's not smart at all in the context of climate change. This is withdrawing more fossil fuels from the ground. Burning those fossil fuels emits greenhouse gases. Also there tend to be fugitive methane emissions from fracking pads and as natural gas is processed. So there's a real concern about adding to the carbon dioxide and methane that's already in the air, and methane has been identified as a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

CURWOOD: Yeah, much more potent, about 80 times more potent when it first is released. Hang on here, I mean, aren't state parks and wildlife areas supposed to be protected by definition, when they're established? I mean, how does the Ohio Department of Natural Resources justify their actions here?

Groups that oppose the projects include Save Ohio Parks, Ohio Environmental Council, Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, and Buckeye Environmental Network. (Photo: Cathy Cowan Becker/ Save Ohio Parks)

KOWALSKI: Their position is that because the drilling is under the surface, they believe that they are still preserving the uses of the properties on the surface. And they believe that extra terms they included will protect the rights of visitors to the parks. The citizens groups say those provisions are inadequate. And they also say, regardless of what the Ohio Department of Natural Resources says, they believe, yes, their enjoyment of the parks will be interfered with. And these are supposed to be lands set aside for everybody's enjoyment.

Opponents argue that fracking threatens water and air quality in the area. They are also concerned about increased greenhouse gas emissions, increased industrial activity, and possible evacuations. (Photo: Paul Becker/Becker1999, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the supporters of these projects, the oil and gas industry. I mean, what do they say are the benefits to the public that come from drilling and fracking under state parks and wildlife areas?

KOWALSKI: Their position is that they are getting energy resources that people need and use. And their position is also that this is going to produce revenue for the state of Ohio. The state will get $58.4 million from Infinity Natural Resources based in West Virginia for the parcels at Salt Fork State Park. Encino Energy will pay a little more than a million dollars for parcels at Valley Run Wildlife Area. And then it will pay about $230,000 for the parcel at Zepernick Wildlife Area. Those amounts are in addition to the royalty amounts of 12 and a half percent. And that's less than the current market value of about 25%.

CURWOOD: What do you see as the long-term potential consequences of allowing these projects to go forward?

KOWALSKI: Well, first, you would have the risk of lasting environmental harm if something goes wrong. And that is a serious concern when there's a relatively small percentage of land in Ohio set aside for public parks and wildlife areas at the state level. And then for Ohio and beyond, the whole situation calls into question the nature of state parks and wildlife areas as being for everyone rather than for the profit interests of a few companies.

Kathiann Kowalski is a Cleveland-based reporter who covers the state of Ohio for Energy News Network. In addition to her journalism career, Kathi is an alumna of Harvard Law School and has spent 15 years practicing law. (Photo: Kathiann Kowalski)

CURWOOD: Kathiann Kowalski is a reporter based in the Cleveland area, who covers the state of Ohio for Energy News Network. Thank you so much.

KOWALSKI: Thank you, glad to be here.

Related links:

- Associated Press | “Ohio Commission Awards Bids to Frack Oil and Gas Under State Parks, Wildlife Areas”

- Read Kathiann Kowalski’s latest article in Energy News Network, “Court Dismisses appeal to block drilling and fracking under Ohio Park and Wildlife Areas”

- Franklin County Judge Jaiza Page’s February 23 decision to dismiss environmental groups’ appeal

- Energy New Network | “Opponents Appeal Decision to Allow Drilling Under Ohio State Parks and Wildlife Areas”

- Opponents’ November 30 appeal to decision to allow drilling under Ohio state park and wildlife areas

- Oil and Gas Commission November 15 Meeting Highlight Reel Video (Save Ohio Parks)

- Energy New Network | “Declaring Natural Gas ‘Green Energy’ in Chicken Bill Violated Ohio Constitution, Groups Argue”

- Initial 2011 law that allows oil and gas drilling in state-owned lands in Ohio

- House Bill 507

- Groups brief arguing HB507 is unconstitutional

[MUSIC: Ken Bonfield, “Homecoming” on Homecoming, by Ken Bonfield, BWE Music]

Beyond the Headlines

Fast food chains like McDonalds are now in compliance with the Food and Drug Administration’s plan of phasing out PFAS from food packaging. PFAS has health issues like cholesterol, weakened liver function and cancer. (Photo: Waferboard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: With me now on the line from Atlanta, Georgia is Living on Earth contributor Peter Dykstra. Hi there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Paloma. We've got news of a collaboration between a government regulatory agency and industry, something we don't hear about very often. But the Food and Drug Administration is collaborating with food manufacturers to eliminate PFAS, the so called forever chemicals from food packaging. Companies like McDonald's already stopped using any packaging with PFAS.

BELTRAN: And we've talked about PFAS chemicals in the past here on the show. Remind us, what are some of the health risks associated to them?

DYKSTRA: There are plenty. Some of the severe health issues could include raised cholesterol, problems with liver function and the immune system, and cancer risks as well. And the forever chemicals part of it is important because these are substances that once appearing in the environment tend to never go away.

BELTRAN: And you shared this recent announcement by the FDA that fast food companies in the US are now in compliance with phasing out PFAS from fast food wrapping. But PFAS is still in a lot of other sources, right?

DYKSTRA: Drinking water is another key source for how it can enter our food chain and our bodies. And there are cleaning products and other things that are a part of our everyday life. But getting it out of our food system is one way to reduce the risks that we're just now beginning to understand.

BELTRAN: PFAS in our fast food sounds really unappetizing, so this definitely seems like a small step in the right direction. Where should we go to next, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's some news from your neck of the woods in Massachusetts. There's an offshore wind farm that has started powering homes in Massachusetts. You might remember 10 or 12 years ago, the saga of Cape Wind, the first attempt to bring large scale wind power to New England. There was a struggle of over a decade. Eventually after a lot of outside money and fierce opposition, the funders of Cape Wind couldn't hold out any longer, the project died. But now very near the site of Cape Wind is a new company called Vineyard Wind. They plan 62 wind turbines, 5 of which are already running, enough to power 30,000 homes. And if and when all 62 of those turbines are up, that potential is going to increase more than tenfold to about 400,000 Massachusetts homes.

Vineyard Wind, the wind farm under construction off the coast of Massachusetts, has begun delivering energy to the power grid, around 68 megawatts of power, enough to power about 30,000 homes. (Photo: National Renewable Energy Lab, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: 400,000 homes, that's amazing. Maybe we'll get some of the energy to help run the LOE broadcast.

DYKSTRA: There you go.

BELTRAN: Now let's look back into history. What do you see Peter?

DYKSTRA: March 8, 2008. There's a meeting of mammalian biology with Monty Python. A castle in Doune, Scotland that was featured in the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail became a field lab for studying migratory bats. Specifically a small bat called the pipistrelle was discovered spending its winters in the castle, where a foul-mouthed French soldier played by John Cleese once taunted King Arthur and his court.

MONTY PYTHON FRENCHMAN: I'll blow my nose at you so-called Arthur King. You and all your silly English kiiiiiiingilits [SPIT].

BELTRAN: Cheap insults and a hit movie and the study of bats, sign me up Peter.

In 2008 more than 30 pipistrelle bats were found hibernating in Doune castle, the Scottish keep featured in the 1975 film "Monty Python and the Holy Grail." (Photo: Dave. Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Oh yeah, and you're dealing with studying mammals, with pythons who of course are not mammals, in a meeting between movies, comedy and biology. Now, go away, or I shall taunt you a second time.

BELTRAN: All right, Peter, thank you for bringing these stories as always. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth contributor and we will talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right Paloma, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BELTRAN: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “US Fast-Food Packaging Says Goodbye to ‘Forever Chemicals’”

- The Daily Climate | “Massachusetts’ Offshore Wind Farm Starts Powering Homes”

- AP News | “Wind Farm Off the Massachusetts Coast Begins Delivering Steady Flow of Power”

- BBC News | “Holy Grail Castle in Bats Mystery”

[MUSIC: San Fernando Symphonic Assembly, “Homeward Bound: King Arthur’s Theme (From Monty Python and the Holy Grail)” on The Dark Crystal: Themes From Epic Fantasy Films and Television Series, BSX Records Inc.]

BELTRAN: Coming up, Ross Gay is back with a Book of (More) Delights. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jacob Christoffersen Trio, “We Want You” on Stunt Records 2017, by J. Christoffersen, Sundance Music]

Ross Gay's Book of (More) Delights

Ross Gay’s The Book of (More) Delights highlights the joy one can find in everyday life and in the natural world. (Photo: Courtesy of Ross Gay and Algonquin Books)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Living on this earth can be a challenge these days. Plenty of crises from the climate to geopolitics can make you feel blue. But poet and essayist Ross Gay keeps creating antidotes to brighten you up. A few years ago he compiled The Book of Delights, loaded with moments of good that sprout amid our troubles. And now after the pandemic he’s back with The Book of (More) Delights with even more scrumptious moments to savor on our complicated planet. Hi Ross and welcome back to Living on Earth!

GAY: Thank you. It's good to see you.

CURWOOD: So this is your second Book of Delights. But what is a delight, exactly?

GAY: You know, I lately have been thinking of it as just like the sort of pleasant, fleeting, often evidence of life. That's really what I've been thinking of it as, this kind of something sweet that happens that often is surprising, that often we don't necessarily know it's delightful, but it happens and we recognize it. And that that, to me, sort of constitutes, "Oh, delight."

CURWOOD: Now, your first Book of Delights came out in 2019. Since then, a few things have happened, like the pandemic. So how did your approach change when writing this book?

Ross Gay’s work focuses on delight not only as one of the pleasures of human life, but as a source of resistance against oppression. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

GAY: I feel like the books are, they're contemporary. They're sort of like considering what's happening day to day, they have a kind of diaristic quality to them. So I'm talking about what's happening. I think, really, the thing that changed most is that it was five years later. I had aged.

CURWOOD: Oh, my goodness, that does happen, doesn't it?

GAY: So you know, like, in the process of writing it, elders died, you know, like, my relationship with my mother is changing as we both are getting older. All kinds of things like that. The book is really a book about aging. I feel like that's one of the things that it is.

CURWOOD: Yeah, this is not television, of course, but you do have a few more gray hairs in that beard, Ross.

GAY: [LAUGHS.] It's true.

CURWOOD: Now, one of your delights is about the joy of clothes on a clothesline. My mother and grandmother loved bringing the clothes in from the line, and this one really hits home for me. I mean, she’d tell me to bury my face in the sheets—“Smell that,” she'd say. Would you mind reading that delight for us? It's on page 19.

The Book of (More) Delights reminds us that we are life. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

GAY: Yes. "The Clothesline." There are so many simple pleasures, simple delights, and maybe the goal, the practice, is to be delighted especially by them, the simplest of things. For instance, today, among the many, I offer the clothesline, not only for its utility, how it keeps the house from getting hot in the summer, how it saves a little energy and burns a little less CO2, but also for how it reminds you that your grandma in northern Minnesota loved to hang her sheets on a clothesline in the winter for how they smelled after they froze, and that your mother loves the smell of anything hung out. But also this, I’m thinking today, as I admire my T-shirts and shorts and drawers and towels blowing in the wind like Tibetan flags, like a ramshackle and sometimes threadbare rainbow: that a clothesline reminds you how often we make of our simple daily labors (hanging clothes, folding clothes, washing dishes, arranging the fridge or the cupboards, chopping veggies or wrapping the bread, sweeping up, or mopping) an art.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now a lot of your essays talk about finding delight in the natural world. How intentional was that? Or does it just simply kind of emerge on its own?

GAY: I think it emerged on its own. I'm a serious gardener. I love the garden. And you know, I spend a lot of time kind of paying close attention to trying to pay close attention to what's happening out there. So I think it probably just emerges by being part of what I do regularly.

CURWOOD: There's a great example of a delight about the natural world and you getting your fingers dirty in the ground. It's called "Garlic Sprouting." It's on page 145. Could you read that, please?

Author Ross Gay enjoys spending time in his garden, watching garlic sprout. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

GAY: "Garlic Sprouting." Although I infrequently feel it when I’m planting garlic in the fall, always later than I’m supposed to (ballpark Halloween, in my book), and although this is my thirteenth consecutive year of planting garlic, during which I’ve had twelve either reasonably or exceptionally successful crops, I realized today that I plant garlic, every year, with no small degree of doubt that it will actually come up, or make, as we say in the trade. I mean, when it comes to garlic, I am batting 1.000. I should say, garlic is batting 1.000. I just hand garlic the bat. But you get my point. Though I didn’t realize, or better yet, I didn’t register, that I plant garlic doubtfully until today, as I was sitting on the back porch, because spring is springing and we’re having a warm one, and midway through a phone call I cast my gaze unexpectantly over the garlic beds and, wouldn’t you know, they were all sprouting, unsheathing a few hundred green blades up toward the sun. With the enthusiasm of someone witnessing a miracle, Lazarus waltzing from his cave or something, I interrupted the friend I was talking to, Wait, wait, yo, it’s up, it’s sprouting! The garlic’s sprouting! It’s up! (The friend seemed glad for me.) Who knew that in addition to vampires and getting your tomato sauce right, garlic’s your tiny professor of faith, your pungent don of gratitude?

CURWOOD: Indeed. I never knew that until now.

GAY: [LAUGHS.] I know, it took me a long time to realize that too. And again and again and again it feels like the garden shows me that like, oh, and this is another thing to be grateful for.

CURWOOD: One of my other favorite delights that you have is the "Squirrel in a Pumpkin." It's on page 80 And I will try to not laugh while you're reading because I don't want to mess up the recording. But could you please read it for us?

Ross Gay’s work includes books such as Inciting Joy: Essays, Be Holding, and Catalog of Unbashed Gratitude. (Photo: Courtesy of Ross Gay and Algonquin Books)

GAY: Sure. "Squirrel in a Pumpkin." On a porch, down the block, on my way, distracted from which, reminded of which, and I was very still, so the critter gobbled away though with an eye on me, which you could tell was really on me when looking down into the pumpkin for more goodies, looking at me, then looking down, then looking at me, then looking down, then looking at me one more time to be sure I guess I was not actually one of the neighborhood cats dressed up like a human being with a backpack, before plunging headlong into the gourd so that all that remained visible of the critter was that plump butt, those long-footed rear legs, and that tail, buoyant, flamboyant, and well, gaudy, even gauche, truth be told. Until popping back out of the pumpkin, eyeballing me again while working over this seed, which, to the squirrel, from the looks of it, would be like me eating a little pizza. I’m talking scale here. This squirrel was in the plumping phase of the year, not worried about spring break. And because of my job, a lucky job as far as they go, I thought, Oh, this is a delight, let me write this down. So I elegantly swiveled my backpack into my frontpack, unzipped slowly as possible, reached into the bag, and as I was pulling out my notebook, the squirrel looked at me like Oh no you don’t you cat dressed as a human, and tipped away, as they do, which might be a small but useful lesson on the differences, or perhaps the consequences, of acquiring, versus being with, or in, or of, the delight.

CURWOOD: So I love this image of make sure that one of those neighborhood cats dressed up like a human.

GAY: It's a sweet one.

CURWOOD: And then gently admonishing us to stay in the moment.

GAY: Yeah.

CURWOOD: You know, like so many of us pull out our iPhones to take a picture of something that’s going on.

GAY: I know it. I know it. That's one of the things that I sort of recognize, and people ask, also, is if the writing down of the delight is a kind of interruption of that process of being in the delight. I think it's a great question. And I also think there's some real deep impulse in us to note and share what we love. And I think that's also like a thing to really value.

Ross Gay finds delight in the simplest of tasks, like doing laundry. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

CURWOOD: Now, you wrote a delight almost every day for an entire year, but you limit the book to 81 delights. So what makes a delight really compelling in your view?

GAY: There's probably a bunch of things. But one of the things, for sure, is if the delight comes from a question as opposed to an understanding. So if the delight sort of holds the fact that I'm wondering about what makes it delightful, as opposed to this other thing, which is like sometimes I'm delighted by something that I kind of know why, and I'm going to explain it. In a way, it almost feels like that's the simplest sort of measure of whether or not I'm going to find it interesting enough to keep. The reason that I write, as I sometimes think these days, is to unknow myself. I want to write with a kind of wonder that makes what I thought I had thought a little bit shaky. Thinking about what you love is one of the ways to do that, to think as powerfully, as closely, as sort of intensely about something. Ideally, for me, I'll come to know that whatever it is that I'm thinking about differently.

CURWOOD: By the way, you have in your book, a recipe for dandelion fritters. The delight is called “Truly Overnight Sometimes It Seems.” I'm wondering if you could please read that essay for us. It's on page 177.

Writing The Book of (More) Delights following 2019's The Book of Delights inspired Ross Gay to think more about the aging process. (Photo: Ross Gay and Algonquin Books)

GAY: "Truly Overnight Sometimes It Seems." It is truly overnight sometimes it seems that the dandelions put on their crowns, and just like that, the world is suddenly brighter, more abundant, more possible—this, of course, if you, like me, adore the dandelion, see their unmartial ranks suddenly outflanking the gloom, outflowering the doom, and if you, like me, make love (a little much?) with its absolutely usable body, body of utter benevolence, body of total beneficence, petite and profligate and gleeful lovenote: the roots for all kinds of medicine, not to mention your various probiotic, bitter, hot morning drinks (for the caffeine-weaning among us); the flowers, which are actually (get close—no, closer—you’ll see what I mean) a million flowers, which the pollinators bloom into a winged dancefloor at our feet; and the leaves, little lion’s teeth, which, in addition to throwing them into your tomato sauce or greens or smoothie or black-eyed-pea fritters, you might do like this: handful or two of leaves, chopped, flour of your choice (cornmeal, chickpea, lentil, whole wheat), onion, garlic powder, paprika, salt, baking powder, water enough to get it all to a clumpy, dandy consistency. Fry in oil on low heat. Or bake them. You can use the flowers for this, too, which can probably be a way of managing or curtailing their reproduction—they [BEEP] like bunnies: those million flowers turn into a million seeds turn into a million million dandelions turn to a million million seeds, all of which is to say, the dandelion giggles at the capitalistic (and monotheistic [No other god but me & etc.] and pop song monogomistic [no one will ever love you like I do & etc.]) myth of scarcity for which it must be destroyed, and quick!—which I have no interest in doing, for they are my most consistent, prolific, generous, trouble- and labor-free crop. I mean, when the squash bugs get the squash, and the cabbage moths the collards, and the blight the tomatoes, the dandelions are steady Freddy. They are the Draymond Greens and Marcus Smarts of the garden. The Brian Grants. The Mo Cheekses or Bobby Joneses. The Patrick Beverleys. They always show up and give their all. We need to give them their flowers! They are also little beacons of the it’ll be okay, and if they had a soundtrack, it would be “O-o-h Child.” Maybe their prettiness, by which I really mean beauty, is because their roots go so far down, they fathom the depths (which, pretty sure, also explains their nutritive profile: Kale can’t hold dandelion’s jockstrap), and those beautiful flowers are missives from the deep. Or the dark. Or the mystery. Or the unknown. Or the underworld. Whichever word we want to use today to mean the dead, or at least the dead-adjacent. Missives from the dead, these little festive blooms. To which, I don’t know about you, but I’m trying to listen.

CURWOOD: Ross, these are difficult times for some of us, maybe all of us. I mean, you think of the climate crisis, various political situations, the world does not feel to be in such a great place. And sometimes when people get depressed they, they're not necessarily interested in finding delights. How can they make the connection, get the antidote to this despair and, and sadness?

GAY: The thing that I think I could say is that it often feels like we live inside of a kind of culture of death, say economy of death, certainly. By which I mean, there's money to be made off of war. There's money to be made off of illness. There's money to be made off of precarity. You know, we're in the midst of a genocide in Gaza. The United States is funding and supporting that genocide. It feels to me that among the things that delight does, is to remind us, as I said at the beginning, that it reminds us that we are life. It reminds us that we are among the living. And it feels to me that the reason we refuse brutality is because we savor and honor and love the sweetness. We refuse the brutality because we are being reverent to life. And it feels like delight is like a little way that we're reminded like, oh, remember life, like remember this sweetness of our connection to one another. Remember this way that we are in fact beholden to one another, and the one another as sort of grand and you know, like these, you know, when the garlic comes up. That's the evidence of being beholden to this thing called life. It seems to me that we have to remember we are in fact beholden to and we need to spend time revering.

CURWOOD: Ross Gay is a poet and author of The Book of (More) Delights. Ross, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

GAY: Thank you. It's great to talk with you.

Related links:

- Listen to our previous interview with Ross Gay

- Read more of Ross Gay’s work

- Purchase Ross Gay’s The Book of (More) Delights: Essays from Bookshop.org to support both Living on Earth and local independent bookstores

[MUSIC: Taj Mahal, “When I Feel the Sea Beneath My Soul” on Sun Rise, by Taj Mahal, Geffen Records (Rereleased by Sony Music)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Paloma Beltran.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth