January 31, 2025

Air Date: January 31, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Bird Flu Warning

View the page for this story

So far avian flu hasn’t been seen spreading from human to human, but recent mutations indicate some variants are becoming better adapted to infecting humans. Dr. Richard Webby of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital also directs a World Health Organization center on the ecology of influenza. He joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain what we know about bird flu so far, and how we can prepare for the possibility of a pandemic. (14:01)

Life As An Incarcerated Firefighter

View the page for this story

Around a thousand of the firefighters who battled blazes around southern California in January 2025 were incarcerated. They do essentially the same work as other firefighters but are paid as little as around $5 a day. Eddie Herrera Jr. shares with Host Aynsley O’Neill what it was like to serve as an incarcerated firefighter, and how the experience helped him forge a new life after prison as a professional firefighter. (11:56)

Exploring the Parks: Brand-New Chuckwalla National Monument

View the page for this story

In his last days in office President Biden designated a new national monument in the southern California desert called Chuckwalla. Producer Paloma Beltran joins Hosts Aynsley O’Neill and Jenni Doering to share perspectives from locals on this unique landscape, including a Native tale of how Coyote gave the “painted canyon” in Chuckwalla its name. (06:57)

Birdnote®: Goldeneyes and Whistling Wings

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

On a still winter afternoon, you may hear Common Goldeneyes flying low across the water. As Ernest Hemingway wrote, their wings make the sound of ripping silk. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports. (01:53)

An Ancient Climate Solution

View the page for this story

As the planet warms, water supplies are dwindling in Athens, Greece. To meet demand the city is looking to antiquity for solutions. One that’s attracting attention is an ancient aqueduct that runs beneath Athens. Niki Kitsantonis is a freelance journalist for the New York Times and a long-time resident of Athens, and she joins Host Jenni Doering to describe the project to fix it up and raise awareness about water scarcity. (09:38)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Eddie Herrera, Niki Kitsantonis, Richard Webby

REPORTERS: Michael Stein

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

So far avian flu hasn’t been seen spreading from human to human but there are warning signs.

WEBBY: When the Canadian authorities and the CDC sequenced the virus, there was evidence that the virus was starting to make some of the key changes that would make it more infectious for humans, so starting to adapt to the human host.

DOERING: Also, a tale of how Coyote created the "painted canyon" in the new Chuckwalla National Monument.

RESVALOSO: He dropped the red blood all over the mountainside. So when you sit here, like from our headquarters, you can look at the mountain, and you can see these red dots, red purple dots out that dot the land along the hillside, that go along all the way towards the east. And that's part of our creation.

DOERING: We’ll have that and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Bird Flu Warning

Avian flu is rampaging through poultry farms, driving up egg prices. (Photo: Alexxx Malev, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The cold winter months are typically thought of as cold and flu season, and in recent years, we've also heard a lot about COVID19 and RSV around this time. But there’s another virus now making headlines: H5N1. That's the name for a variant of influenza we know as bird flu, and the virus itself has been around for decades. But here at the start of 2025, it has been running rampant in the wild bird population, it’s destroying flocks of chickens, and has mutated to infect cows. One variant even resulted in a human death in Louisiana in recent weeks and hospitalized a Canadian last fall. For more, we turn now to Dr. Richard Webby of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

He’s also the director of the Collaborating Centre for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds at the World Health Organization. Dr. Webby, welcome to Living on Earth!

WEBBY: Well, thanks Aynsley. It's great to be here.

O'NEILL: So what is the distinction between H5N1 and your typical seasonal flu?

WEBBY: The major difference between these are the hosts that they're associated with. So the seasonal flu that we get every winter, that's a virus that is maintained just within humans. So its goes human to human to human. There's no involvement of any other animal species in the maintenance of that virus. What is the ancestry of those viruses? So at one stage, they were avian viruses. All influenza viruses exist as the natural host in the aquatic bird reservoirs of the world. So the human seasonal strains went from birds to humans, now maintained in humans. The H5, again, so genetically, it's related to the viruses in humans, they're all influenza viruses, but it's a virus that is much more adapted for replication still in the avian host, it hasn't adapted to humans. So I guess the real answer to your question is, they're all influenza viruses, but they have slight differences in terms of how they interact with host cells, how they replicate. One prefers to bind to avian cells, that's the H5. The others prefer to bind to human cells.

The H5N1 virus, also known as bird flu, has a variant that has mutated to infect dairy cows. Experts warn that unpasteurized milk could be contaminated and dairy workers could become infected. (Photo: RF Vila, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: And from what I have heard, the very serious cases and the fatality are likely caused by the outbreak in wild birds, as opposed to being traced to maybe the bovine outbreak. Correct?

WEBBY: That's correct. I think, if you're sort of summing up where we are in the US now with the H5 situation, we've already got two fronts going on. We have the virus -- again, went from birds into cows in early 2024, maybe late 2023 -- that's maintained primarily just in cows now, with the odd spill over to other hosts. And then the other front is the virus that caused the more severe infections in Canada and Louisiana. It has also caused mild infections as well. We can't forget about that, but that is a purely a wild bird driven event. So as the migratory birds came down from up north, they brought this particular version of the virus with them. So, H5 in both wild birds, poultry and cows, but you can think of it probably like the variants with COVID: slight variants of the same virus in each of those hosts right now.

O’NEILL: If the virus mutates to become transmissible, human to human, what do you think is likely to happen? You know, should we be gearing up for the next COVID-like pandemic?

WEBBY: [SIGHS] Oh, I really wish I had the answer to this one, Aynsley. It's tough, right? So intrinsically, this H5N1 virus, at least in my mind, has the capacity to cause far more severe disease than the Coronavirus that caused the COVID pandemic. At least what we're seeing in terms of many of the hosts that are being infected with it. We're not seeing that same degree of disease in most of the humans to date, but that's probably because this virus, as you sort of alluded to, is not well adapted to humans right now. So should it change, we don't really have a good idea of what disease may look like, but on paper, we've been looking at influenza viruses for many decades here at St. Jude, and this is the nastiest virus that we have dealt with. So the potential is really, really scary, but bottom line is, we don't know. Would we be faced with worst case scenario, middle case scenario, or best case scenario? Unfortunately, it's something we just don't, we don't have the answer to, so we're just got to, what we got to do is be prepared for the worst case scenario and hope that's not the case.

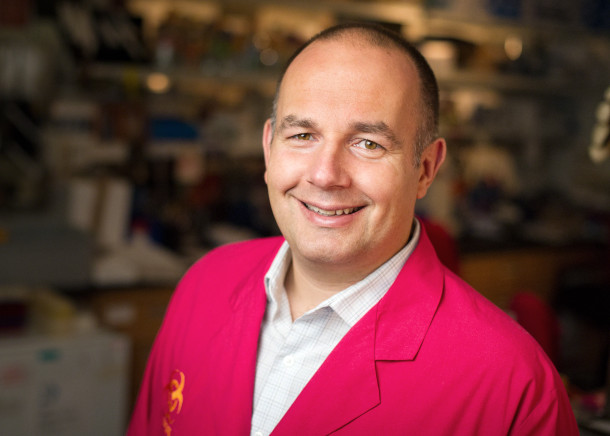

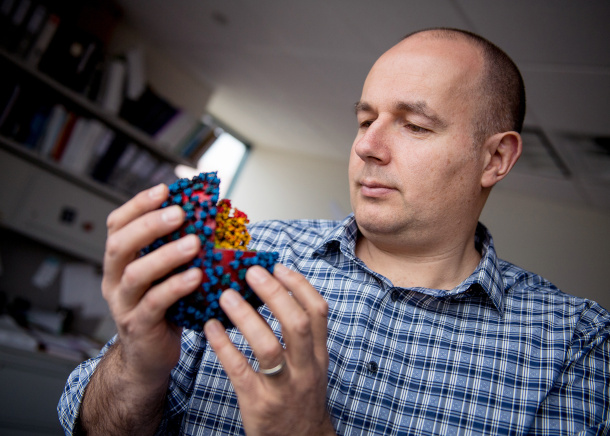

Dr. Richard Webby is a member of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital’s faculty and the director of the World Health Organization’s Collaborating Centre for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds. (Photo: Courtesy of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital)

O'NEILL: Now, what about vaccines? What is the status of any vaccinations that may be in progress, and how would they possibly affect the reach of this virus?

WEBBY: There's sort of multi fronts to that question. One, we can vaccinate cows. Two, we can vaccinate chickens. Or three, we can vaccinate humans. If we look at those sort of individually, from the cow front, there are vaccines that are being developed and are being tested. Exactly where they are in the process, I'm not sure, but you know, certainly field testing was initiated on those vaccines. So theoretically, we could have a vaccine to immunize cows, should that be needed. From a poultry front, there are approved, licensed poultry vaccines that are used across the globe. They're not approved for use in the US because of trade barriers that come about through use of vaccines in birds. So they're there if they're needed, but they're not approved for use. In humans, if we think of all the nasties that are circulating in animal populations that human health is worried about, we're probably more prepared for an H5 in terms of vaccines than anything else. Studies have been going on for two decades with H5 vaccines in humans -- how do we formulate them best? How do we best deliver them? What's the best way to grow them and make them? And so from that perspective, we know how to make an H5 vaccine, unlike the beginning of the COVID pandemic, where we really had no idea. So we know how to make them. We've made them. We've tested them. Some countries, including the US, have some amounts of vaccine stockpiled, which could be useful at the very, very beginning. And of course, the US and other countries have also invested in some of these newer technologies as well. So the vaccines I talked about, there are more of the traditional shot-in-the-arm vaccines that we're used to. The mRNA technologies, of course, they have the capacity to contribute to a response as well. And the US government has invested heavily in pushing some of the mRNA vaccines forward as well.

Dr. Webby warns duck hunters to be careful when handling their catches because they could be infected with H5N1. (Photo: Alain Carpentier, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

O'NEILL: Yeah, I remember mRNA vaccines, I mostly associate with the COVID 19 pandemic. What have you heard about that development? And to what extent are you hopeful about it or not so hopeful?

WEBBY: Yeah, so the mRNA vaccines, a lot of them were being tested on flu before the COVID pandemic came along. The US government has invested heavily in this to bring this technology along as a backup to traditional methods, should a pandemic occur. Where are those vaccines now? They're being made. They're being tested. The manufacturers can make the vaccines fine. What we don't really know is how well they work in humans against the H5 virus. So H5 vaccines historically have been a little bit poor in their ability to induce a really robust immune response. So while I absolutely think we need to invest and find out how an mRNA vaccine would work, we don't yet know how that will behave in humans when targeting an H5 virus.

O'NEILL: What can individuals be doing about this to reduce their risk?

WEBBY: I think it's important to say, yeah, if you're not in contact with dairy cattle or large poultry operations, your risk right now is exceedingly low. All the human cases have been bird or cow to human and no human to human transmission. So if you don't have those exposures, your risk is low. But what you can do, again, considering we have seen an uptick of activity of H5 virus in wild birds over the past few weeks, if you're out and about and you see a bird acting weirdly, meaning it's just walking in circles and looking very sick. Just give it a wide berth, and treat it like it could be potentially infectious. The other group that I quite often get asked questions about is duck hunters. Should they be worried? Just be a little bit sense about this. Just treat a bird like yes, potentially is infected. Chances of getting infected from it are slim, but it's not zero. So again, particularly if you're eviscerating the bird, cleaning the bird, just be really careful. Wear gloves, do it in an outside, ventilated area. But otherwise, there's not too much the average person needs to do or can be doing.

While a H5N1 pandemic could be catastrophic, unlike with the COVID vaccine shown here, scientists already have H5N1 vaccines stockpiled. They are likely, but not guaranteed, to be effective. (Photo: City of Greenville, North Carolina, Flickr, public domain)

O'NEILL: And then what about on a public health level?

WEBBY: So from a public health level, the three, I think, pillars, to the response are testing, ability to treat, and sort of a vaccine response. And you know, there have been efforts in all of those three pillars over the past few months. Resources are being put into increasing capacity to test for H5, increasing the availability of some of the flu antivirals, and also development of the vaccines as well. So from public health, there is some preparedness going on. Is it enough? No, it's never enough. But it does take resources, and it's resources for something that may never happen. So it's a challenging equation to get right.

O'NEILL: Dr. Webby, at this point, just how worried are you?

WEBBY: I tell people I'm a little more uneasy now than I was six weeks ago. So where were we six weeks ago? The big risk was infected dairy cattle, but the virus had been circulating in that host for now close to a year, and we haven't really seen that virus evolve into something that's a little bit more infectious for humans. We know, when we sequence the viruses from cows, we know some of the markers that we're looking for to suggest, okay, this is a virus. That's a bird virus, but these are some changes, mutations it’s making that probably make it more infectious for humans. We really hadn't seen much of that going on. But we are, what's happened more recently, one is the two severe cases in Canada and Louisiana. It wasn't so much the severity of infection that worries me, but when the Canadian authorities and the CDC sequenced the virus from those individuals, there was evidence that the virus was starting to make some of the key changes that would make it more infectious for humans, so starting to adapt to the human host. So before that, we hadn't seen any of the evidence the virus was making these changes. Now we've seen it so we know it probably can make those changes. And there's also a study that came out recently from investigators at the Scripps Institute in California, where they could show that a single mutation in the virus switched it from recognizing the preferred receptor for the avian virus to the preferred receptor for the human virus. And what does that mean? It just simply means that a single amino acid mutation could potentially make the virus bind to human cells better. It's a virus that's got to bind to the human cells to get inside and replicate. So combined, those two things are making me a little a little more uneasy. I don't think this virus is, meaning the H5, virus is a human pathogen. Certainly it's not a human pathogen yet, and I do think the barriers for it to overcome are probably pretty high. But the potential consequences of an H5 pandemic, if the worst case scenario were to occur, is frightening. So it, it’s, how to balance that? Yes, it's probably a rare event. But should that rare event occur, it's going to be awful.

O'NEILL: Dr. Richard Webby is a researcher at St Jude Children's Research Hospital and the director of the World Health Organization's Collaborating Center for Studies on the Ecology of Influenza in Animals and Birds. Dr. Webby, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

Dr. Richard Webby and other virologists are monitoring any mutations of the H5N1 virus to see if it becomes more of a threat to humans. (Photo: Courtesy of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital)

WEBBY: Well, thank you so much. I've enjoyed it.

DOERING: Gosh, so, Aynsley, sounds like we'll have to keep an eagle eye on this bird flu story going forward.

O'NEILL: Definitely, but one thing that could complicate efforts to stay vigilant is the communication freeze that the Trump Administration put in place for health agencies including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

DOERING: Hmm. And on day one, I believe, President Trump issued an executive order to pull the US out of the World Health Organization. So how might those moves imperil our ability to respond to a potential avian flu threat?

O’NEILL: Right, as you might imagine disease reporting that’s collected and disseminated by the CDC is essential to this country's disease response and control strategies. City and state health departments need to know if a new public health threat is starting to emerge, whether that’s avian flu or something else. Meanwhile, pulling out of the World Health Organization cuts off communication between the WHO and the CDC. You know, it takes a full year to officially withdraw – so we’re still on the hook for paying our membership dues of $130 million dollars – but even so, U.S. officials like those at the CDC have not been attending meetings at the WHO. As such, our researchers will be unable to examine the recent data from those gatherings on diseases like the avian flu.

DOERING: And the WHO has what, nearly 200 member states still? Sounds like we’ll be left out of the loop.

O’NEILL: We really could. And although many city, state, and nongovernmental organizations will be doing what they can to track disease numbers and spread, the exit from WHO and the pause on federal public health communication could lead to an epidemic spiraling out of control.

Related links:

- Learn more about St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

- Explore the CDC’s bird flu page.

- Read about Dr. Richard Webby’s work.

[MUSIC: Oscar Peterson, “Stormy Weather” on Work From Home with Oscar Peterson, UMG Recordings]

DOERING: Just ahead, working as firefighters offers incarcerated people a path to redemption. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Oscar Peterson, “Stormy Weather” on Work From Home with Oscar Peterson, UMG Recordings]

Life As An Incarcerated Firefighter

Eddie says that incarcerated fire fighters face greater risk from the health effects of smoke inhalation if they don’t get access to the high-quality healthcare free firefighters receive. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

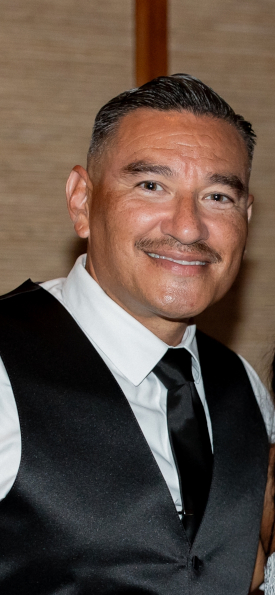

The wildfires that have burned entire neighborhoods in Los Angeles this January took a massive response from firefighters to start to get under control. According to state officials more than 16,000 personnel battled the blazes across southern California at the height of the disaster. And over 1,000 of those people are currently serving prison sentences. While incarcerated firefighters do the same work as their counterparts, they are paid much less, as little as $5.80 a day. Here to talk to us about his experience in the program is Eduardo Herrera Jr. Eddie served eighteen years in prison and spent the final two of them as a firefighter. Now, he’s a professional firefighter for the state of California. Hi Eddie, welcome to Living on Earth!

HERRERA: Thank you for having me, pleasure to be here.

O'NEILL: So I understand that you were an incarcerated firefighter between 2019 and 2020, what is the day to day life like for an incarcerated firefighter?

HERRERA: So for me, it’s very unique. I actually lived at a firehouse. So my title was Institutional Municipal Firefighter. So what you would see in your normal municipal firehouse was very much the day to day, other than me being incarcerated, obviously. So I got up in the morning, did my training, did my six minutes of safety and weather, and then started my day running calls or just doing training.

O'NEILL: And now is that the standard setup, or was yours a unique case?

Eddie Herrera Jr. is a professional firefighter for the state of California. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

HERRERA: So in the state of California, every adult prison has a firehouse to service the prison system itself, but that also some of them have what we call a mutual aid contract. And not all of them do. But in my case, mine had a strong mutual aid contract with the county I service, and so that therefore you service the community where you're housed at. But to be clear, that station is outside the prison grounds.

O'NEILL: And now, we're talking about this in terms of wildfires. But was that the majority of calls that you were taking, or were there other types as well?

HERRERA: For the most part, it's a lot of medical calls, but there's definitely a balance between vegetation fires, wildland fires, vehicle accidents, residential structure fires, rescues. So depending how the season goes or the call volume is, it can vary.

O'NEILL: And how did you become involved in this program in the first place?

HERRERA: So I started with requesting to be there. I had to work my way down and go through a vetting process, and obviously applying, and then going through an interview process with the captain of the firehouse, and then upon completion of the interview, then I was able to go through an actual testing process. It takes approximately two and a half months to three months, and you do the cycle motor skills, and then you also do the academic and curriculum part of it. So completing that, once you upon completing that, now you actually can shadow but if you do not complete that, then you actually go back to the prison you're housed at and you're not in the program.

O'NEILL: And now there's been a lot of discussion surrounding fair compensation with incarcerated firefighters, especially in the light of these recent wildfire outbreaks in California. During your time, when you were incarcerated, how much were you paid for your firefighting work, and how did you feel about that compensation?

Incarcerated firefighters are currently fighting the L.A. wildfires while getting paid well below minimum wage. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

HERRERA: So it's very different. I will say I got paid a lot less than your fire camp or wildland firefighters. I figured, since we were servicing the community and actually going into people's houses to perform medical and mitigate those situations and actually being close to the community, I thought it would be more, but it was actually $56 a month. That was the max I would make. It didn't matter if I was running a residential structure fire, saving a house, or CPR call. It did not matter. I was still going to make $56 a month. So it's very little compared to what you make in fire camp. When you're actually fighting a fire, you make $1 an hour. So if you're out on a fire and that fire lasts three weeks, you do the math, it can add up.

O'NEILL: And now there's special concerns about this low compensation given the round-the-clock firefighting that is happening, especially with California opening the program up to inmates under 26. How do you respond to concerns about this?

HERRERA: Well, I definitely think that we should be compensated a lot more than what we're getting paid. I mean, simply put as this, we're doing the job, and now the public is is starting to see it, because we do save property. We do save lives, right? And so how can you put a price on that? And at the end of the day, like, the big picture is you do it because you believe in yourself. You want to demonstrate, you know, that you're not defined by your crime. But, I mean, let's be realistic, the amount of pay that you're making is really nothing compared to what an actual individual that does do the exact same thing gets paid a lot more. Not only that, gets a pension, right, and gets great medical service. And we, as inmate firefighters or incarcerated firefighters, are more exposed to smoke inhalation, and we're in the front lines, and so therefore those health issues affect us directly. So being in prison shouldn't be a death sentence, you know. So I totally think that there should be some compensation in regards to that, because at the end of the day, when you are released from the program, there's a very likelihood that you have some health issues moving forward in your life.

Inmate firefighters receive all of the standard firefighting training while incarcerated, but if they want to continue with the career after their release, they must go through nearly identical training all over again. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

O'NEILL: So as I understand it, you were trained to be a firefighter while incarcerated, and then after release, you had to undergo the same training all over again?

HERRERA: That is correct. So me, as an institutional municipal firefighter, all the training that I did there, I did it all over again when I went to the Ventura Training Center. But as far as the job itself, it's still the same. And the same thing as wildland firefighters that are in fire camp, you get the exact same wildland training because you're already doing the job, the work. So it's no different, but just with the training that I had, I could have done the job when I came home. But the one thing I will say is that most important is, it's invaluable, is the experience. Because I had more experience than some of these firefighters that are out now, that are 18, 19-year-olds that are working as firefighters. I had 14 structure fires under my belt, vehicle fires, countless CPRs, medical calls, and wildland fires, and was already doing the job. I will share with you this one call that I ran, saving a residential structure fire, pulling up, seeing it on fire, extinguishing the fire, but finding out afterwards it was a correctional officer's house, and them coming to me and my partner's hands and shaking her hand and saying, "Thank you for saving our house." So these are the things that we're capable of doing. That, in itself, demonstrates that that we can do the job. Who better than individuals that were previously incarcerated, that want redemption, want to prove themselves? We are one of the hardest workers out there, and we've demonstrated it time and time again, consistently.

O'NEILL: Now there's a noted connection between personal history of trauma and incarceration. And then on top of that, we recently covered how merely being exposed to wildfires is traumatizing in and of itself, not to mention actually fighting these fires. So that's trauma on top of trauma. How do you and your fellow former inmates or the current inmates cope with the mental health aspect of this?

While incarcerated, Eddie responded to a full range of calls from CPR calls at the prison to saving the house of a correction officer. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

HERRERA: Great question, and I think that that is one of the biggest challenge. For me, I'll speak on my personal experiences. I did a lot of work prior to going to the firehouse, before I even started running calls and fire calls, so I developed coping skills, resiliency. However, there is a lot of trauma when you see things and experience that, as far as running wildland fire calls or just calls in general. And so when you see these things, you're taking them in, and they're just there. And if you don't know how to process them, eventually they come out. And so an individual that is currently incarcerated, seeing all this devastation, seeing these fires, is on heightened alert, always, high stress level situation, and then comes home, is released in society, and then now sees it again. They're triggered. And so being able to have things in place, as for instance, mental health, you know, addressing mental health is very important. And we don't, unfortunately; in the fire service or as an incarcerated firefighter, there's a stigma that goes with that that mental health. So a lot of people don't ask for help. I do believe that as an incarcerated firefighter and individuals are still incarcerated, it’s so important to address these issues, because upon coming home, just something like the smell of smoke or hearing the sirens can trigger it, you know? And so I think it's very important for that to be addressed now and recognized now.

O'NEILL: What do you want people to know about either incarceration, generally speaking, or specifically the experience of incarcerated firefighters?

HERRERA: Yes. So it makes me think about, I'm paraphrasing here, but a quote by Dostoevsky where he says, "You can tell a lot about a country by how it treats its prisoners." And so for me, the way I look at it is, well, how it treats his heroes, because an incarcerated firefighter is now deemed as a hero. So I think that that's very important, because we're no longer defined by our mistake that we've made. We're going to come home. 90% of the population that are currently incarcerated are coming home. What kind of people do you want them to come home to? Do you want an inviting society, and if so, demonstrate it in actions: allow the opportunities to be able to have programs, classes, just stuff, so they can come home as better people. I would say, for the general public and individuals that are now experiencing this to think about that, because the key to it is this one word is, is hope. We all want hope and hope for change, right? And that's exactly what myself and individuals who have been incarcerated, that's what allows us to survive and move forward, is that hope.

Eddie is grateful for the redemption that the incarcerated firefighting program offered him. He wants everyone to know that inmates are more than the crimes they are incarcerated for. (Photo: Courtesy of Eddie Herrera Jr.)

O'NEILL: We've talked a bit about the concept of redemption and change as it relates to this program. What kind of support is needed from the wider world when these formerly incarcerated firefighters and these former inmates, generally speaking, are coming home?

HERRERA: So one of the biggest way you can support us is changing laws. In life, our words are validated by our actions. So if people really want to create change, they have to be willing to show up. And showing up is in the polls, is when they see something that's injustice, see something that's not right, is put it into action and change those laws. Because you guys are our voices. We don't have a right to vote. So for the public, what I would like to see changes is demonstrated in action by showing up and changing those laws that don't allow us to get paid what we should be getting paid, allowing us to have the funding, to be able to have classes and training in place, that if you are an incarcerated firefighter, therefore you're able to get the actual accreditation while you're still incarcerated, since you're already doing the job, so therefore when you are released, it's a lot easier for you to transition into that job and become a career firefighter. So I'm grateful that we're having this discussion now, because it's personal to me. So thank you.

O'NEILL: Eddie Herrera, Jr. is a professional firefighter for the state of California. Eddie, thank you for giving us some of your time today.

HERRERA: Absolutely. Thank you for having me. I'm humbled just by being able to be here and speak with you.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Anti-Recidivism Coalition.

- High Country News | "What it’s like to be an incarcerated firefighter"

- Explore California’s incarcerated wildfire fighter program.

[MUSIC: James Galway, “Morning Mood” from Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46, on The Best of James Galway, by Edvard Grieg, Sony Music Entertainment]

Exploring the Parks: Brand-New Chuckwalla National Monument

The Chuckwalla National monument is named after the Chuckwalla lizard pictured above. (Photo: Brent, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So, Aynsley, remember the “Exploring the Parks” series we’ve featured on Living on Earth in the past few years?

O’NEILL: Oh, for sure I love that segment – we’ve talked about Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Aniakchak National Monument in Alaska…

DOERING: Oh that was one of my favorites, there was also Petrified Forest National Park, and Sequoia and Kings Canyon, just to name a few. Well, I think it’s time to add to that series and we might as well start with some brand-new protected areas. During his last days in office former President Biden declared two new national monuments, the Chuckwalla and Sáttítla.

O’NEILL: And both of those, I believe, were from your home state of California, right Jenni?

DOERING: That’s right, and our colleague Paloma Beltran, who hails from around there too has been talking with some of the community leaders and tribal members who advocated for them. Hi Paloma! So can you tell us about Chuckwalla National Monument? Where exactly is it?

BELTRAN: Hi Jenni, sure! So, this one is in Southern California out in the desert, and it’s around 624,000 acres from Coachella Valley all the way to the Colorado River. It’s named after the Chuckwalla lizard, native to the area. And it extends a conservation corridor that goes from Bears Ears National Monument in Utah to Joshua Tree National Park in California, a 600-mile stretch of protected land.

And there was a lot of support for the creation of this monument. You know, business groups, the California legislature, more than 370 scientists, residents of the eastern Coachella Valley, and multiple tribal nations.

The painted canyon hills or Mecca hills inside the Chuckwalla National Monument are part of the Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla tribe creation story. (Photo: Courtesy of Gary Wayne Resvaloso Jr.)

O’NEILL: Ok wow, lots of people on board. And specifically what kind of connection do the tribal communities have to the area?

BELTRAN: So there are sacred trails, sites and objects, rock art, and culturally important plants and wildlife. I talked to Gary Wayne Resvaloso Jr., a Torres Martinez Desert Cahuilla Tribal Council Member, and he said that the area is home to painted canyons, also known as the Mecca hills, that are part of their creation story.

RESVALOSO: When they cremated our Creator, right? They sent Coyote to the west to gather some stuff to help with the ceremony, because they understood that nature is to scavenge, right? So they understood that he would try to eat our Creator. So when the smoke went up, Coyote’s seeing it, he came back in. He grabbed Mukat’s heart and he ran with it, because his thing is, he wanted to eat it, right? He wanted because, he wanted to take him. And as he ran with it, he dropped the red blood all over the mountainside. So when you sit here, like from our headquarters, you can look at the mountain, and you can see these red dots, red-purple dots out there that dot the land along the hillside, that go along all the way towards the east. And that's, that's part of our creation. That's what that is, it's that beautiful landscape that's out there.

O’NEILL: Whoa! So no wonder you said the place is now known as a “painted canyon.”

DOERING: Yeah, what an amazing creation story! And what about the biodiversity there?

BELTRAN: Well, one local who had a lot to say about that was Evan Trubee, Palm Desert City Councilor and owner of Big Wheel Tours, a bike and car tour company that works across Palm Desert. And he described it as a transitional zone where the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts come together, offering stunning landscapes, and all sorts of wildlife.

The round tailed ground squirrel survives in the Sonoran Desert and Mojave Desert by estivating during summer months. (Picture: Bhavishya Goel, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

TRUBEE: It is rocky, it is arid, it is full of life, and it is magnificent. The desert tortoise is, that's definitely their habitat, particularly in some of the washes and areas that we go visit, you have everything from large mammals, even mule deer, mountain lions, kit foxes, coyotes, all the classic desert creatures that you would expect, road runners, all the way down to the beetles and insects that all play a role in this incredibly dynamic ecological system.

BELTRAN: Evan said that designating the Chuckwalla area as a national monument prevents development, which is a way to protect endangered species like the Mojave Desert Tortoise. The solar energy industry has been interested in the area, but solar stakeholders were consulted as the monument was being developed, and they’re generally in support of it. You know, thanks to that blazing sunshine combined with desert dryness, this is a land of extremes, where in the summer it can get up to 120 degrees or more and it can get below freezing overnight.

O’NEILL: Oh yeesh…

DOERING: Wow, talk about weather whiplash.

BELTRAN: Yeah I know! But Evan Trubee says animals adapted to these conditions still manage to survive.

TRUBEE: As hard as it is for people to believe, the desert creatures are still out there doing their thing, hunting for food and hunting for water and doing everything else they need to live. There's one particular squirrel, who body temperature can get up to 107 degrees and they will actually estivate in the summertime, in response to extreme heat and aridity. When water is scarce and the temperatures are hot, they will go into an almost hibernation. They will dig a burrow about a foot and a half underground, and slow down their metabolic rates, like one heartbeat and two breaths a minute or something of that nature, and stay in that state for two or three months until it's safe to come back out and there's plenty of food and water again. That’s an extreme. So you've got, gosh, over the course of a year, you could have 100 degree temperature variations in one desert location out there in what is now Chuckwalla national monument. It's incredible, it’s like no other place.

The Chuckwalla National Monument protects 624,270 acres in Riverside and Imperial counties and borders Joshua Tree National Park. (Photo: U.S. Department of the Interior, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

O’NEILL: That’s so cool, I love hearing about a resilient desert creature.

DOERING: Yeah, I’m impressed. So, despite the heat what sorts of activities can people do out there?

BELTRAN: Well, overall it seems like the ideal place to get out and enjoy nature.

Evan says there’s hiking, horseback riding, camping, you name it.

TRUBEE: Believe it or not, there's some mining claims out there that date back to the 1800s and are still even active today, sort of as hobbyist claims. So that's one of the activities that a lot of people don't even think about regularly. Dirt road driving that you can do on jeeps, motorcycles, quads, sand rails, vehicles like that; mountain biking. So there's wheeled vehicle activities that you can do out there on designated trails. And that's the key that I really want to reiterate to people, or hope that most people understand, that you want to keep it on the trails. It's a delicate, delicate ecosystem that does not recover well after being trammeled. So it's just an outlet for people to get out and enjoy nature. Get out of the big cities, get out of the hustle bustle, get out of their daily routine and get quiet and enjoy the activities they like to enjoy and commune with nature. It's a beautiful place.

O’NEILL: All right, well I’m going to have to slather on some sunscreen and get out to Chuckwalla National Monument, it sounds incredible!

DOERING: Sign me up too! Thanks Paloma. And I’m looking forward to hearing more soon about the Sáttítla National Monument in northern California as part of our “Exploring the Parks” series.

BELTRAN: Sure thing - thank you both!

O’NEILL: And if you want to hear more of those “Exploring the Parks” segments head on over to LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Chuckwalla National Monument

- Audubon California | “Chuckwalla National Monument"

- LA Times | “Biden to Create Chuckwalla National Monument”

- Coachella Valley Independent | “Hiking With T: The New Chuckwalla National Monument Includes Some of the Best Desert Hiking in Southern California”

[MUSIC: Cindy Cashdollar, “Foggy Mountain Rock” on Bluegrass Album Band: The Bluegrass Guitar Collection, Rounder Records]

DOERING: Coming up – Athens is bringing back to life an ancient underground aqueduct to help cope with worsening drought. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gary Burton, “O Grande Amour” live at KNKX Public Radio, by Antonio Carlos Jobim, Youtube]

Birdnote®: Goldeneyes and Whistling Wings

A common goldeneye soars close to the waves. (Photo: © Andrew Reding CC, Courtesy of BirdNote®)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

O’NEILL: With the concerns about wild birds carrying avian flu these days, one of the great things about being a birdwatcher – if you’re so inclined -- is that you don’t have to get close to enjoy them. You just need to keep your eyes peeled -- and your ears, for that matter. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein has this one.

BirdNote®

Goldeneyes and Whistling Wings

Written by Todd Peterson

(Sound of Barrow’s Goldeneye wings in flight)

You may get to know these birds by sound as much as sight.

On a still winter afternoon, walking the shore of Puget or Long Island Sound, you’ll hear them coming low across the water. Goldeneyes, also known as “whistlers”, their wings sibilant, making the sound, as Ernest Hemingway wrote, of ripping silk.

(Waves lapping and whistling wings)

You’re likely to see their piercing golden eyes and the striking domino black-and-white of the male’s plumage as you board a ferry or travel by boat along the shore.

(Sound of ferry horn)

Sometimes in squadrons, they dive for crustaceans and mollusks.

Autumn brings both species of Goldeneyes, Common and Barrows. You’ll know the male Barrow’s by the half-moon of white between its brilliant yellow eye and short bill.

Enjoy them now while you can. In spring, goldeneyes will be gone, returning to the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska to breed and hatch their young in the cavities of trees. And you’ll have to wait until next November to hear again the music of their wings.

(Sound of goldeneye wings in flight)

I’m Michael Stein.

BirdNote's newsletter delivers the wonder and joy of birds directly to your inbox. Sign up at BirdNote dot org to get a weekly preview of our shows, stories, photos, and more.

###

Sounds of the Barrows Goldeneye provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recordist WWH Gunn.

Ambient provided by Kessler Productions

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org November 2016/ 2018/ 2019/ 2024

ID#BAGO-01b-2019-11-10 BAGO-01b

O’NEILL: For pictures, fly on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related link:

This story on the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Pepe Barcellos, “Anhanga” on Brazilian Playground, by Pepe Barcellos, Putumayo Kids]

DOERING: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, sign up for our free, weekly newsletter. You’ll get special access to show highlights and early notification about upcoming live virtual events.

O’NEILL: And we now feature exclusive letters from our staff. This January our Executive Producer Steve Curwood wrote about the early warnings on the climate crisis dating back to the Carter presidency, and he pointed out that despite the delay it’s not too late to act.

DOERING: Intern Daniela Faria shared what she learned from our recent story about the “Dirty Dozen” and “Clean Fifteen” guides to minimizing pesticide exposure without breaking the bank. And our producer Sophia Pandelidis tapped into her Greek heritage and gave a preview of the Athens story you’re about to hear. And Aynsley – you’re on deck this week, right?

O’NEILL: Ooh, that I am, Jenni! But no spoilers! – you’re just going to have to read it yourself. So don’t miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe dot org. That's loe dot org.

[MUSIC: Sippe Wallace with Roosevelt Sykes, piano, “Women Be Wise” on Women Be WisJe, by Sippe Wallace, Alligator Records]

An Ancient Climate Solution

Hadrian’s aqueduct, built in the second century AD by Roman emperor Hadrian, still carries water under the city of Athens. (Photo: Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, , Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Climate disruption has plagued the city of Athens, Greece with intensifying drought and extreme heat. And as the water supply dwindles and demand surges from residents and tourists alike, the city is looking to antiquity for solutions. One that’s attracting attention is an ancient aqueduct that runs beneath Athens, and it’s largely intact. So, a project to fix it up and repurpose it is underway. Niki Kitsantonis is a freelance journalist for the New York Times and a long-time resident of Athens. Welcome to Living on Earth, Niki!

KITSANTONIS: Thanks very much, Jenni.

DOERING: So tell me about this ancient aqueduct underneath Athens. Just how extensive is it, and how did it serve the city in the past?

KITSANTONIS: Well, it's an aqueduct that was built in the second century AD, it was commissioned by the Roman Emperor Hadrian, and hence its name, Hadrian's aqueduct. And it pretty much supplied Athens with water for a very long time. In fact, it only really stopped, there was a pause during Greece's Ottoman occupation when much of it was destroyed. And what isn't really widely known by the people of Athens and in Greece generally, is that it continues to operate. It's still functional. In fact, it's the longest operational underground ancient aqueduct in Europe. So it's about 15 miles, and it has lasted the test of time. I mean, it's lasted essentially 2000 years. The issue is that it hasn't been tapped into. So although the water was continuing to run, it wasn't actually being used. And that's what they're trying to change now, sort of reharnessing this ancient network to try and solve a modern problem, which is drought, or, you know, scarce water supplies.

DOERING: So what's the plan for getting this off the ground? How will the water be used, and who will get to use it?

Athens is facing climate-change induced drought, heat, and wildfires. (Photo: dronepicr, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

KITSANTONIS: So the test project area for the aqueduct reoperating is in Halandri. Halandri is a suburb of Athens. It's actually just north of the capital, quite big for the area. It's about 80,000 people that live there. A few hundred have applied to be connected to the pipeline in the first instance. So there is, obviously, there's the ancient aqueduct, and then there's this new, smaller network that runs parallel to the ancient aqueduct and is connected by pipeline to a number of homes in this particular borough. The water is non potable, so it won't be drinking water. It'll be for use in like watering gardens, washing, that sort of thing. So the aim is then to spin it out to another seven boroughs under which the aqueduct runs. The challenge, I think that the authorities have is in raising awareness and public interest in the aqueduct, because at the moment, there isn't anything really resembling a national or even local awareness campaign. And in fact, when I was reporting it, I was talking to people literally drinking coffee in a cafe called Reservoir, the name of the cafe's Reservoir. It's right next to the central reservoir of the ancient aqueduct. And nobody knew that it existed. Most people said, Oh, I just thought that was the name of the cafe. I had no idea it was linked to an actual aqueduct.

DOERING: What is the scale here in terms of how much this aqueduct might make a dent in Athens’ water savings over, let's say, a year?

The aqueduct has survived, largely intact, for almost 2000 years. However, water hasn’t been meaningfully collected for about a century. (Photo: Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

KITSANTONIS: Well, to be honest, the actual savings in terms of water are a fraction of what Athenians use. So assuming that this network is extended to another seven boroughs, the projected saving is around 250 million gallons, which sounds like a lot, but when you bear in mind that the average annual consumption in Athens is 100 billion gallons of water, it's less than 1%. So we're talking about quite a small fraction of water that is actually going to be saved. But what the authorities are really flagging is the need to change what they call the water culture in Greece, to change the way that water is used, and to change people's habits whereby water is not just something that you can leave the shower running or the water running in the garden, as people used to do, and as lots of people I spoke to said, that that's what they used to do. And now they're telling their children, switch off the water in the garden, to cut down on their shower time, fill the bath halfway. This is something very new in Greece, because it is such a hot country, and it's becoming hotter. People were very liberal in their use of water, and this is something now that they're hoping that the reactivation of this aqueduct will help people change the way they think about water and just view it as a precious commodity, and something that needs to be preserved and not wasted.

DOERING: So it sounds like it's about more than the numbers. It's about changing culture.

KITSANTONIS: That's right.

DOERING: To what extent are there, you know, of course, this water would be going to some homes, but are there going to be any other more visible projects that, in the ways that this water is used, that Athenians will be able to see and enjoy?

Authorities hope that by earmarking water from the aqueduct for non-potable uses, Athenians will become more aware of when and why they use water. (Photo: Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

KITSANTONIS: So in addition to the homes, the schools, the water from the aqueduct will be used to irrigate green areas. And the idea is to sort of reduce this heat island effect in that particular area. And the aim is to then present this as a test project to other boroughs, so that they can see what can be done with this additional water and how the impact of climate change during the summer, particularly, can be tackled with just a different approach to using water and redirecting water in a smart way to bring down temperatures.

DOERING: Yeah, as you say, that sounds really important on a really hot day in summer in Greece, to have, you know, lush green space, like a park where people can go and enjoy the benefits of those plants cooling the area.

KITSANTONIS: Right, yeah.

DOERING: So how might this model be used elsewhere? What other cities have the potential to tap into these kinds of ancient systems to address these present challenges?

KITSANTONIS: Well, one city that has asked for help from the Greek authorities is the Portuguese city of Serpa. They have a 17th century aqueduct that they plan to reharness in the same way that Athens has done with its ancient aqueduct. They're also very interested in the citizen participation aspect of the project, and the way that so many different parties managed to sort of collaborate in such an effective way. Locals in the Halandri area, the test project area, got so involved in the project. And children, school children also got involved in, not only learning about the sort of the ancient history of it, the engineering of it, but they actually got involved with some of the urban design. So they designed water tanks that are going to be in the schools. They designed green areas that are going to run over the aqueduct's course in their neighborhoods. And this is something unusual. You don't really see that much citizen participation in Greek sort of local authority projects. It's something that isn't the norm, let's say. This is also something that officials in Rome have been very interested about, which is quite ironic, because Hadrian was obviously a Roman emperor, so the Romans are now asking the Athenians for help in, not actually in reactivating an aqueduct, but in using citizen participation in other initiatives.

Over the last few years, wildfires have come closer to Athens. (Photo: George E. Koronaios, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: So Niki, from your perspective, to what extent are the climate crisis and its effects part of the public conversation in Athens and Greece more broadly, and how might this project contribute to that conversation?

KITSANTONIS: Well, the climate conversation in Greece is something relatively new and is only really something that authorities started talking about because they started seeing the intense repercussions of climate change in terms of mega fires, wildfires that spiraled out of control, heat related deaths, something very new for Greece. And in 2024 we saw three or four islands actually declaring a state of emergency because they ran out of water. So this was something that was really in the news this year, something relatively new, and something that authorities, in a way, have been obliged to start talking about. So it's becoming a part of the conversation, but only very recently. Some argue that it's a bit too late. As one would say, though, climate change is something that worldwide has been tackled, perhaps with a bit of a delay, but at least we're seeing some discussion about it now, albeit in response to quite tragic developments.

DOERING: Before you go, as a resident of Athens yourself, Niki, what are you hoping the city will look like in the coming years as we continue to adapt to climate change?

Niki Kitsantonis is a freelance journalist for the New York Times based in Athens. (Photo: New York Times)

KITSANTONIS: Well, as a resident of Athens, I do worry about what the city is going to look like in the next few years, because the truth is, over the last few years, I struggle with rising temperatures. I find that I've had to change the way I work, the way I plan my day around extremely high temperatures that were not the norm 20 years ago when I moved to Athens from London. And it's something that I worry about, because every year it gets worse and worse and more intense and it gets harder to deal with. So the thought that this could continue to intensify is quite terrifying, actually. Because apart from the practical problems of adapting to work, there's also what you see around you in terms of forest fires, which have become increasingly common and have actually become visible closer to the capital now, so it's beginning to change our life in a very visible way. And the idea behind this project is to sensitize the public to the fact that water is running out and the fact that action needs to be taken.

DOERING: Niki Kitsantonis is a freelance correspondent for The New York Times based in Athens. Thank you so much, Niki.

KITSANTONIS: Thanks, Jenni, thanks a lot.

Related link:

Read Niki Kitsantonis’ article in the New York Times

[MUSIC: Mikis Theodorakis, “Zorba the Greek: Zorba’s Dance” on Zorba the Greek (Remastered), FM Records]

O’NEILL: Next time on Living on Earth, there’s a lot of forest in Maine, to make a huge understatement. So how do scientists know which part of the woods are the old growth and the most important to protect from logging?

HAGAN: We are using light detection and ranging, LIDAR, to try to find the old growth forest in the vast 10 million acres. It's like looking for a needle in a haystack. It turns out that LIDAR is kind of like a CAT scan of the forest. If you shoot LIDAR at the forest from an airplane, it gives you a three-dimensional signature of the forest if, if, if you know art history it’s kind of like pointillism, it's just a massive three-dimensional point cloud of the forest and that, turns out, can tell us exactly where the old forest is. We didn't know, before LIDAR and how we use it to map it, we didn't know where it was. You, you had to stumble upon the old forest to find it or to know about it. Now we've got a map and the older stands are blue, magenta, everything that's younger is yellows or oranges or light greens. You can color it any way you want, but it's kind of like a neon sign. It's like light up this old growth forest on the map and LIDAR’s just, I call it magic. I'm supposed to be a scientist, but to me, LiDAR just seems like magic, what it shows you about the forest.

O’NEILL: We’ll travel to the forests of Maine, next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Simon Oslender, Steve Gadd, Will Lee, “Along the Coast” Single, Broken Silence Records / Leapord]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt and El Wilson. And we welcome interns Melba Torres and Ashanti McLean.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and You Tube music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth