March 26, 1999

Air Date: March 26, 1999

SEGMENTS

Retrofitting America's Malls

/ David PollockMany of the first generation of America's shopping malls are too small or too old-fashioned to attract top retailers. They end up as outlet malls, discount centers or just plain empty. In Chattanooga, the new owners of one mall are trying to turn it into a real town center. David Pollock reports. (06:10)

Town in the Dumps

/ Linda TatelbaumChange comes slowly to a small town. But as Living On Earth commentator Linda Tatelbaum explains, losing the town dump can make things change a lot faster. (02:35)

Wolves in Midtown ... or Jogging with Wolves

New Yorkers have long been on the cutting edge of all sorts of social innovations. While their fair city is not known for vast open spaces, its residents often respond to the call of the wild. That's why some New Yorkers say the city is just the place to try to introduce a troubled species to an urban setting. As April begins, Amy Eddings takes a look at a potential new immigrant in Central Park. ()

The Greening of Israel

/ Patricia GolanWhile it's the Holy Land for some, for others the tiny nation of Israel has become a waste heap. The record amounts of water and air pollution plaguing Israelis had largely gone unnoticed. That is until politicians began incorporating environmental themes into their latest campaigns. Patricia Golan reports on whether this new 'green consciousness' will make a difference in the May national elections. (06:50)

The Living on Earth Almanac

This week, facts about... the largest inland body of salt water in the western hemisphere, Utah's Great Salt Lake. (01:25)

Three Mile Island Retrospective

/ Terry FitzPatrickTwenty years after Three Mile Island we look back at the nation's worst commercial nuclear accident. Using archival materials and interviews with area residents who lived through the accident, Living On Earth’s Terry FitzPatrick reconstructs the days in late March and early April, 1979, that changed the nation's energy policy. He also looks at whether radiation released during the accident has had lasting health effects on people who live near the plant. (11:20)

TMI Today

Host Steve Curwood talks with Tom Kaufman, a spokesperson for Three Mile Island operators General Public Utilities - Nuclear, about his reflections on the accident and how it affected the nuclear industry. (04:55)

A Resident Reminisces

As a life-long resident of Middletown, Pennsylvania, just across the river from the Three Mile Island plant, Bonnie Valentine talks with Steve about how the accident forever changed the character of her hometown. (04:45)

Culture Melt-Down

From movies and music to television and even board games, the accident at Three Mile Island quickly became part of American popular culture. (03:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

REPORTERS: David Pollock, Amy Eddings, Patricia Golan, Terry FitzPatrick

GUESTS: Tom Kaufman, Bonnie Valentine

COMMENTATOR: Linda Tatelbaum

(Theme music intro)

CURWOOD: From National Public Radio, this is Living on Earth.

(Music up and under)

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Chattanooga, Tennessee tries a new twist to fight sprawl: jazz up those old inner-city suburban shopping malls and turn them into village centers.

MINGUS: Six or 8 months ago there was nothing in this place. Now we've got this skating rink. There's a dad holding his daughter's arm going around the skating rink. We've got families here.

CURWOOD: And as April begins, we hear about plans to introduce wolves into New York City's Central Park.

STERN: When I was appointed commissioner of Mayor Giuliani, I said I wanted to be a man for all species. And the more different animals and plants we can introduce to New York City parks, the broader and more diverse our ecosystem will be. That's good.

CURWOOD: Also, a rural community faces the end of a social institution. The town dump is shutting down. We'll have that and more this week on Living on Earth, right after this news.

(NPR News follows)

(Music up and under)

Retrofitting America's Malls

CURWOOD: This is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Sprawling development can seem unstoppable. Like so many cities years ago, downtown Chattanooga, Tennessee, went into decline as businesses and homeowners expanded out to the suburbs. And before long, that inner ring of suburbs tumbled into decay as well, as developers sought more space further out for newer and bigger shopping malls and homes. But things are turning around in Chattanooga. Its downtown now has plenty of busy restaurants, stores, and entertainment. And Chattanooga's inner ring of faded strip malls is the target of a unique suburban renewal project that holds plenty of promise. David Pollock reports.

(Voices echoing)

POLLOCK: Sitting in the middle of the once-thriving Eastgate Mall, a group of long-time residents sips coffee and laments the slow death this mall experienced over the last 10 years. One man says the decline of the mall reflects the decline of the neighborhood.

(Echoing voices and music in the background)

MAN 1: It's old and run-down. It's low-income families for a large part. There are some pockets of places that are well-kept, but there are many pockets of places that are run-down, and people just stay away from there.

POLLOCK: This mall was once part of a lively suburb. When it was built 35 years ago, it contributed to the decline of downtown. But now the mall, and the neighborhood around it, have become victims of suburban sprawl, themselves.

MAN 1: Restaurants, your nice restaurants. You don't have all those along here any more. They all moved out there.

POLLOCK: "Out there" is 5 miles further out of town, where 10 years ago a newer, bigger mall opened and subsequently drained much retail activity from Eastgate Mall and the entire Brainard community. Property values fell and the mall virtually closed.

Recently, city and business leaders have come together to reverse the decay of this suburb and slow the city's outward sprawl. The effort began when Jerry Shovin's company, Eastgate Enterprises, bought the mall with intentions of turning it into an office park for several major clients. But when the company asked residents of the area what they thought the mall should look like, Shovin says they clamored for more than offices.

SHOVIN: They wanted to see grocery. They wanted to see a dry-cleaner. They wanted to see a drug store. They wanted to see some restaurants. They wanted to be able to come here and congregate, you know; they wanted to come here and enjoy retail without going out to other locations.

POLLOCK: What they wanted, Shovin concluded, was a new town center. Brainard, like many suburbs, has no social or business center, so the mall redevelopment evolved.

SHOVIN: We can create, in essence, a neighborhood within a neighborhood. We can take this center with its surrounding parking and its 65-70 acres, and transform it into an urban-looking, mixed-use center.

POLLOCK: The project is similar to many downtown renewal efforts, except that it is attempting to recreate a downtown in the suburbs.

SHOVIN: When we're done, we will have approximately 45,000 office workers. They can come to work in a safe environment, geographically close to where they live, drop their child, go to work, see their child at lunch time, get their nails done, go to the dry-cleaner, stop at the grocery store, and go home. One-stop shopping, and the conveniences of connecting to amusement, entertainment, you know, back to Main Street USA.

POLLOCK: The town center plan appealed to local officials, because the development could occur using infrastructure that was already in place around the mall. Unlike with the new suburban subdivision, the city doesn't have to invest in new roads, sewers, and other public services.

(Traffic sounds)

POLLOCK: Driving through the neighborhood of small, working-class box homes, city planner Rick Wood says that by creating a downtown-type Main Street, he hopes local residents will join office workers there in making the place a lively and functioning town center. If Wood has his way, neighborhood roads that dead-end at the mall parking lot will be reopened to connect the main street with the neighborhood.

WOOD: As you can see, when we're sort of driving down this street, you saw a big Dead End sign on the end of this street. We don't think that there's nothing dead at the end of the street, you know; we want to focus on connecting the houses and the people that live here and the residents to the activity and the new activity at the mall.

POLLOCK: Mall activity will now focus on pedestrians. The redesign includes turning stores outward toward the sidewalks and providing angled parking in front of them. The most visible part of the redevelopment will look like a small-town Main Street with 2-story shops on a town square. The city of Chattanooga will build a park, and on the park will be perhaps one of the most unique aspects of the Eastgate redevelopment.

(Traffic)

MINGUS: If we kind of cross this roadway, which will be approximately here, then we've just about now walked onto the site. And so the sanctuary will be just about where that red car is parked right now.

POLLOCK: Pilgrim Congregational Church plans to move onto the new town center square. The Reverend John Mingus says that being in the middle of things enables his church to be a vital park of the community.

MINGUS: We have a particular thing, a thing that people need in their lives, a place to connect with their life, to connect with their faith. And it just makes sense to me to put it downtown. This is a downtown for this part of the city.

POLLOCK: Reverend Mingus says that with the work already begun on the project, the beginning of the town square, new facades on the mall, an ice- skating ring in the mall's center, for example, new life is already coming to the area.

(Voices and laughter echo)

MINGUS: Six or 8 months ago there was nothing in this place. Now we've got this skating rink. There's a dad holding his daughter's arm going around the skating rink. We've got families here.

POLLOCK: Creating this new town center is a work in progress. The dead-end streets, for instance, may or may not be opened up. Efforts to bring new residential housing onto the property are stalled for now. And owners have balked at the suggestion they cut a street right through the center of the mall. But the developers are confident their new town center will work, not only for the Brainard community but for their business as well. In fact, they are so confident for the idea, they are planning to create another town center: an old mall in a run-down section of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. For Living on Earth, I'm David Pollock in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

(Echoing voices up and under)

Town in the Dumps

CURWOOD: Change can come slowly to the places where we live, and to small towns it often comes very slowly. But as commentator Linda Tatelbaum found out, losing the town dump can make change come a whole lot faster.

TATELBAUM: When a town loses its dump, it loses more than the communal gossip center. It loses more than the ability to bury what it doesn't want to deal with. A town without a dump loses its innocence. Now there are consequences to every action.

In the good old days we backed our loaded trucks to the edge of the abyss. We were too busy socializing as we jettisoned our junk to notice the pit growing shallower, the pile growing higher. When the state outlawed burning, we began to bury the stuff. Nothing could stop our communal ritual. But the pile grew higher, the abyss shallower, until finally you pitched your stuff up and watched it roll back down to land at your feet. All that junk mail finally did us in. The state closed our dump.

Now, instead, we sip our solitary coffee and watch a truck haul away our household trash at a dollar a bag. The rising cost forced us to recycle. It's easy for newcomers, who came here intending to live by old ways. But they can't convince the old-timers, who hoped to put hardship behind them forever after World War II. And now here we are again, crushing our cans and bundling our newspapers.

Dealing with what we don't want to deal with has an emotional cost as well. The dump used to be where we buried our differences. Now, some of us push for community composting and conscientious consumerism, while others resist. The only outlet for stress is the carefree tossing of junk from moving vehicles. For every plastic bag with an official "paid for" sticker sitting responsibly, even primly, by the roadside, there's a field dotted with forlorn junk in search of the lost landfills of yesteryear.

Oh, for the days when the dump satisfied our hunger to hang out together. All we have left now to heal our differences is Town Meeting in March, when cabin fever drives us to crave company. But starting this year, Town Meeting will be held in June, when we're all too busy for jawing. The fiscal year sets the schedule, now that we have to pay to get rid of our junk. You see, once a town loses its dump, before you know it, everything will change.

CURWOOD: Linda Tatelbaum lives in Appleton, Maine, and teaches English at Colby College. Her latest book is "Carrying Water as a Way of Life: A Homesteader's History."

(Music up and under)

Wolves in Midtown ... or Jogging with Wolves

CURWOOD: Reintroducing wolves into parts of the United States has been a controversial but largely successful venture. Wolf populations in Yellowstone National Park are thriving. The animal is holding its own in Arizona. And North Carolina's red wolf program is held up as a model of how to restore species to their original habitat. These success stories are prompting calls to bring the wolf back into places like New York State's Adirondack Mountains. And as Amy Eddings of member station WNYC reports, even New York City is getting into the act, with a plan to release wolves in the Big Apple's biggest open space, Central Park.

EDDINGS: Yes, you heard that right. Wolves in Central Park. The plan seems totally wacky until you spend time with wolf biologist John McCloskey. This native New Yorker's enthusiasm is infectious, and his passion for wolves is so great he adopted 5 pups who were orphaned last November in Montana. He takes me to where he's been keeping them in a large, wooded enclosure in Westchester County.

(Footfalls amidst bird song)

McCLOSKEY: Come on! (Whistles) Come on! Hey, Scooter!

EDDINGS: Is that the alpha male?

McCLOSKEY: (whispers) Yeah, yeah, that's right. Scooter, he's a big fella, if he comes around -- Scooter! Scoot! Hey, look at him now, see?

EDDINGS: Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

McCLOSKEY: His big blue eyes.

EDDINGS: Wow.

McCLOSKEY: (laughs) Now, does that look like a terrifying beast to you?

EDDINGS: McCloskey says wolves will never attack humans. He feeds them mice, squirrels, groundhogs, rabbits, and rats, exactly the kind of diet they'd eat if released in Central Park. For 2 years McCloskey helped Federal officials successfully reintroduce wolves in Yellowstone. Parks officials here have already restored native species like snapping turtles and white pine to the park. McCloskey says wolves are a natural extension.

McCLOSKEY: They're a more romantic figure. They're a more exciting figure. They're -- they're hungry, and they're social, and they are creative and adaptable in their behaviors. Wolves are New Yorkers.

EDDINGS: Central Park contributor David Feingold has invested nearly $80,000 in the project, primarily toward publicity and marketing tie-ins, like a glossy brochure for park visitors called "On the Trail of the Wolf." Feingold opens the brochure to a map of the park dotted with different colored wolf paw prints.

FEINGOLD: Some of these are viewing areas. Some of them are concession areas. And many of you may remember that there's a structure by the Harlem Meer [word?], and we're proposing that that be turned into a restaurant for dining and viewing experiences.

EDDINGS: Feingold says wolves will draw visitors to the park and double concessions' profits through the sale of wolf T-shirts, caps, books, and stuffed animals. And he's convinced that in a year or 2 the wolves will pay for themselves. That's if the plan overcomes the fierce opposition of community groups neighboring the park. The plan was leaked 2 weeks ago to residents like Ruth Messina. She's president of Coalition for Kids, an Upper West Side park and playground advocacy group.

MESSINA: The fact is, has this ever been done before? Have you introduced wolves into an urban area? No, this has not been done before. I personally don't want to put my 2-year-old son Trevor into the jaws of a wolf. I don't want to take that risk.

EDDINGS: And some environmental advocates say the plan is not good for the wolves. They'll say they'll run into traffic, eat rat poison, or be hunted down by pranksters. Parks Commissioner Henry Stern hasn't commented yet on the project, but says a healthy ecosystem is good for the park.

STERN: When I was appointed commissioner of Mayor Giuliani, I said I wanted to be a man for all species. And that includes animals and plants. And the more different animals and plants we can introduce to New York City parks, the broader and more diverse our ecosystem will be. That's good.

EDDINGS: McCloskey, meanwhile, keeps his spirits up through frequent visits to the Westchester wolf enclosure.

(Wolf pups howl)

EDDINGS: As we talk outside his office a half a mile away, the thrilling sound of the howling pack arches over the trees.

(Howling continues)

EDDINGS: That's great.

McCLOSKEY: Can you imagine that answering back when you have a [word inaudible] concert in Central Park? (Eddings laughs)

EDDINGS: If not Central Park, then other parks. John McCloskey is currently studying places like Albany and Boston for his urban wildlife restoration project.

(Howling continues)

EDDINGS: For Living on Earth, I'm Amy Eddings in Westchester County.

(Howling continues; fade to music up and under)

CURWOOD: We welcome your comments on our program. Call our listener line any time at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988. Or send us an e-mail at LOE@NPR.ORG. Once again, LOE@NPR.ORG. Our postal address is 8 Story Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138. And you can find our Web page at www.livingonearth.org. That's www.livingonearth.org. Coming up: we'll travel to Israel, where a green political party is trying to blossom. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

(Music up and under)

The Greening of Israel

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Israelis consider their land sacred, but Israel is one of the most polluted countries in the world. Untreated industrial waste flows directly into rivers and streams. Air pollution is dangerously high. Until recent municipal elections, ecology wasn't high on the political agenda. But for the first time, green parties won important electoral seats in Haifa and Tel Aviv. And some 80 candidates for local office signed a pledge to improve environmental quality. From Jerusalem, Patricia Golan looks at the role green activists are playing in Israel's upcoming national elections.

(Men chant in Hebrew)

GOLAN: Dozens of students demonstrate in central Tel Aviv, demanding that in this election year political parties pay more attention to the need for mass transportation. Highways are a disaster. Trains are the solution, they chant. Some of the protestors poke their heads through sheets sewn together and painted to look like train carriages. Like a bizarre Chinese dragon, they snake their way through the crowded streets. In recent years traffic on Israel's highways has become increasingly congested. Traffic deaths have skyrocketed, and pollution from vehicle exhaust is at dangerous levels. The protesters' spokesman, David Perelman, complains about the Israeli government's cutback on mass transit.

PERELMAN: All they've done in the last 50 years is taken apart trains, and only the trains can solve the problems of the people dying from traffic accidents, people dying from air pollution, massive problems on the roads from the congestion. And also in such a small country, there's no room to build more roads.

GOLAN: This student group, called Green Course, is the largest environmental network in Israel, with branches on 14 campuses. The week before, members chained themselves to bulldozers that were paving a highway in the West Bank. Such green activism is a fairly new phenomenon in Israel. While in the past local environmentalists made up a small, somewhat elitist group, today some 140,000 Israelis belong to an array of local environmental organizations. In municipal elections this past November, 13 environmental activists were elected to city and town councils throughout the country. Shmuel Chen of the Israeli Economic Forum for the Environment says the election results were a shot in the arm for green activists.

CHEN: Environmentalists have been working in Israel for years, being aware for environmental problems, but not really succeeding when it came down to, you know, budget questions, decision-making questions. They could lobby, but they couldn't really make the change. The last elections were a big breakthrough for the, I'd say, Israeli environmentalists.

RONEN: [Speaks in Hebrew]

GOLAN: Doubtless encouraged by the newfound popularity of green issues, in January the Director General of the Environment Ministry, Nahama Ronen, launched a new party, the Voice of the Environment, to run in the May elections for Israel's parliament, or Knesset.

RONEN: [Speaks in Hebrew] TRANSLATOR: We've got an ecological time bomb in this country. Fifteen- hundred Israelis die every year from air pollution. In another 10 years we won't have anywhere left to dump our refuse. Politicians are devoting their time to issues like negotiations with the Palestinians, the Golan Heights, and figuring out Israel's borders. But they are failing to deal with the environmental problems that threaten our lives.

GOLAN: But less than a month later, Ronen abandoned her new environmental party and announced she was joining the newly-formed Center Party held by former Defense Minister Itzhak Mordechai. Alon Tal, founder of the Israel Union for Environmental Defense, admits that Ronen worried she would not get enough votes to make it into the next parliament as head of an independent, environmentally-oriented party. But, says Tal, moving to the Center party means that an environmental presence in the Knesset is now a sure thing.

TAL: The strong feeling amongst many Israelis that the Center party will be sitting in whatever coalition ultimately arises, that means for the first time you have a serious green or environmentally-sensitive leverage going into the political process.

GOLAN: Though Nahama Ronen jumped ship, there is another independent environmental party running for Knesset.

VIESNER: [Speaks in Hebrew]

GOLAN: Peher Viesner heads the Israeli Green Party, which won 2 seats in Tel Aviv in the November municipal elections. The party was formed after the 1997 Maccabeeah Bridge catastrophe, in which 4 Australian athletes attending the games died and more than 60 were injured after a temporary footbridge collapsed. The athletes fell into the polluted waters of the Yarkon River, and probably died from inhaling toxic wastes. Viesner says that the foot-dragging over cleaning up the Yarkon River has shown Israelis that they need political power to save the environment. But what chance to greens have of gaining meaningful participation in the Knesset? Under an electoral reform that allows Israelis to cast 1 vote for prime minister and another for political party, there is more temptation than ever to vote for a small party. Still, a party has to break a 1.5% threshold, about 50,000 votes, to win 1 of the 120 seats in the parliament.

(Many voices milling)

GOLAN: Earlier this year, representatives of more than 60 Israeli environmental organizations met in a Tel Aviv suburb to discuss strategies for the future. Participants here agree that the success of the greens in the municipal elections, and the fact that the environment is on the agenda in the national elections, points to a new awareness among Israeli politicians and the electorate. Whether this trend will translate into ballots come May remains to be seen. For Living on Earth, I'm Patricia Golan in Tel Aviv.

(Milling continues; fade to music up and under)

CURWOOD: It's NPR's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

(Music up and under)

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Ford Foundation for reporting on environment and development issues; the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for reporting on western issues; the Pew Charitable Trusts for reporting on threats to the world's marine environment: www.pewtrusts.com; Jennifer and Ted Stanley; and Church and Dwight, a tradition of environmental responsibility: the makers of Arm and Hammer Baking Soda, the standard of purity.

(Music up and under)

NPR ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

CURWOOD: Just ahead: 20 years ago disaster derailed nuclear power in the US. We assess the impact on the industry and those who live in the shadow of Three Mile Island. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

(Music up and under)

SECOND HALF HOUR

(Theme music up and under)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood

(Music up and under)

The Living on Earth Almanac

CURWOOD: Great Salt Lake in Utah is the largest inland body of salt water in the Western Hemisphere. It's a remnant of a prehistoric lake which covered 20,000 square miles of what is now Utah, Nevada, and Idaho. The surrounding mountains are still ringed like a bathtub by the shorelines that existed 25,000 years ago. And the lake continues to shrink as water from its rivers is diverted for irrigation. The Great Salt Lake is about 5 times saltier than the oceans. That's because the rivers that dump into it contain water that's high in mineral salts. And since it doesn't have an outlet to the sea, the minerals get trapped. The lake today holds about 400 million tons of salts. Though local legends place a school of whales and a bellowing monster in the lake, the only things known to live in it are microscopic brine shrimp and bluegreen algae. But millions of birds nest on the shores and islands of the Great Salt Lake. And on its largest island, antelope and buffalo indeed do roam. And for this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac.

(Music up and under)

(Surf)

Three Mile Island Retrospective

Three Mile Island was the site of America's worst commercial nuclear accident. The nuclear core suffered a partial meltdown, and radiation releases forced the evacuation of thousands of people.

CURWOOD: Along the banks of the Susquehanna River here near Middletown, Pennsylvania, you can see the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. It's by far the dominant feature on the landscape.

(Humming)

CURWOOD: There's a gigantic hum of electric power that emanates from this sprawling facility. It's out on a sand bar in the middle of the river and has 4 concrete cooling towers, each one as tall as a 40-story building. Dense clouds of white water vapor are billowing up from 2 of the towers. It's dramatic, but it's normal. But what happened here on March 28, 1979, was anything but normal. Three Mile Island was the site of America's worst commercial nuclear accident. The nuclear core suffered a partial meltdown, and radiation releases forced the evacuation of thousands of people. Today, 20 years after the accident, we'll try to assess its impact on the physical and emotional health of people who live here. And we'll explore how this single event changed the course of the nuclear industry and the nation's energy policy. In a few minutes, we'll talk with a spokesman for the plant, and with a woman whose family used to farm the land where the facility now sits. But first, Living on Earth's Terry FitzPatrick takes us back to the spring of 1979.

The Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania was the site of America's worst commercial nuclear accident. On March 28, 1979, a combination of technical malfunctions and human error caused the reactor core of Unit Two to melt, releasing radioactivity and forcing the evacuation of thousands of local residents. Unit Two remains closed, but Unit One continues to generate power. Clouds of water vapor rise from Unit One's massive cooling towers along the banks of the Susquehanna River.

(Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

(Humming continues up and under)

FITZ PATRICK: It happened on a Wednesday morning at 4AM, at one of America's newest and biggest nuclear power plants.

(Voice: "This breaking story has just come in. State police in Harrisburg have been called to the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, where plant officials have called a general emergency...)

FITZ PATRICK: A leaky pipe and faulty valve forced an emergency shutdown.

WHITTICK: I heard this loud roar. It sounded like a big jet taking off very close by.

FITZ PATRICK: The noise awakened William Whittick, who lives a mile away from the plant.

WHITTICK: I went to the window, and I could see this jet of steam coming up.

(Humming continues; fade to distant radio voices)

FITZ PATRICK: Inside the control room, inadequate instruments and poorly- trained operators led officials to believe the radioactive core was safely covered with coolant. In fact, the reactor was melting.

(Radio voices continue)

MAN 1: That all the numbers you got?

MAN 2: Yeah, those are the only numbers.

MAN 1: Okay.

FITZ PATRICK: When consultants from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission arrived later that day, they were shocked by what they found.

MAN 1: Couple of radiation levels.

MAN 2: Okay.

MAN 1: Two hundred R per hour.

MAN 2: Yeah.

MAN 1: In-stack containment --

MAN 2: Holy Jesus! Oh, they've got a release inside. Two hundred R per hour?

FITZ PATRICK: Several hours passed before plant officials told local authorities about the shutdown. At first, they said the situation was under control. Then they said the reactor was still unstable, and that radiation was released into the surrounding community. Robert Reed, who was mayor of Middletown, the town closest to the plant, was furious he hadn't been told the full story immediately.

REED: Here it is, 8, 8:30 in the morning. People are going to work, kids are going to school, out in the playground. I said boy oh boy, I think we got zapped by a good dose of radiation. And I felt, here we have a nuclear facility run by people that don't know what they're doing. Either they don't know what they're doing or they're telling us lies.

ANNOUNCER: This is the CBS Evening News, with Walter Cronkite.

CRONKITE: Good evening. The world has never known a day quite like today. It faced the considerable uncertainties and dangers of the worst nuclear power plant accident of the atomic age. And the horror tonight is that it could get much worse. It has not...

FITZ PATRICK: Over the next few days, things did get worse. Radioactive gas continued to escape, as technicians struggled to cool the smouldering core and prevent a rupture in the building that contained it. Pennsylvania Governor Dick Thornburg called for a limited evacuation.

THORNBURG: I am advising those who may be particularly susceptible to the effects of any radiation, that is, pregnant women and preschool-age children, to leave the area within a 5-mile radius of the Three Mile Island facility until further notice.

FITZ PATRICK: To reassure the public that the situation was under control, President Jimmy Carter, a nuclear engineer himself, toured the facility with the First Lady at his side.

CARTER: The primary and overriding concern for all of us is the health and the safety of the people of this entire area. If we make an error, all of us want to err on the side of extra precautions and extra safety.

(Humming continues)

FITZ PATRICK: Five days after the accident began, technicians restabilized the reactor, and the 140,000 people who had evacuated returned home. Eventually they would learn that 50% of the reactor core had melted, sending 20 tons of uranium fuel onto the containment room floor.

(A motor starts up. A dog barks.)

FITZ PATRICK: Now, 2 decades later, some area residents are still bitter over the way the accident was handled. And people still debate whether radiation releases harmed the public. Plant officials say the average radiation exposure to people living within 10 miles of Three Mile Island was equivalent to a chest X-ray. Dr. Kenneth Miller of Penn State University Hospital in nearby Hershey, Pennsylvania, says there have been no long-term health effects.

MILLER: About a dozen different health effects studies conducted on the populations in this area showed that there have been no increases in any type of disease in this area that could be attributed to anything that happened during that accident.

FITZ PATRICK: However, researchers from the University of North Carolina have recently found an alarming incidence of cancer near the plant. Their conclusion is hotly debated among scientists, and the conflicting medical studies have left residents like Mary Osborn suspicious and angry.

OSBORN: The industry and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and our state government and Federal government got away with murder here. You know, that's the simple truth.

FITZ PATRICK: Ms. Osborn believes the amount of radiation emitted during the accident was far greater than officials have disclosed. And since 1979, she's documented subsequent radiation releases during clean-up operations at the plant. The damaged reactor is closed forever, but Ms. Osborn still keeps a black hand-held device on her coffee table.

Mary Osborn of the grassroots anti-nuclear group TMI Alert, checks her personal radiation monitor. Many people who live near the plant now keep "Rad Alert" devices inside their homes. The device creates a high-pitched chirping sound, much like a household smoke alarm, if excessive radiation is detected. (Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

OSBORN: This is my radiation monitor. (Beeps) I have mine on all the time.

FITZ PATRICK: So that goes off every now and then around here.

OSBORN: Yes, it does. Yeah. A lot of the time it's just background.

FITZ PATRICK: This seems depressing. Because you've got to live with this thing?

OSBORN: (laughs) Yeah, but you have to understand something. Living without it is more depressing, you know, because after you go through an accident and you're lied to so much, who do you trust? (Beeps)

FITZ PATRICK: This is life today in the shadow of Three Mile Island. Some residents live in fear. And whenever a neighbor or family member becomes seriously ill, they question if the accident somehow caused it. But not everyone feels this way.

(Traffic)

LANE: I've had a health effect. I certainly don't blame it on this incident.

FITZ PATRICK: Current Middletown Mayor, Barbara Lane.

LANE: I developed non-Hodgekins lymphoma, and never one time did I question myself, was it was out of TMI? Because the type of non-Hodgekins I had probably was attributed to chemicals through hair dye, and never one time did I blame it on the accident.

FITZ PATRICK: Others, though, remain convinced the accident has taken a terrible toll. Annie Myers lived on a dairy farm 5 miles from the plant, but did not evacuate.

MYERS: Well, that day, I always remember because it was my birthday. It was frightening. I thought it was frightening.

FITZ PATRICK: Ms. Myers picks up a portrait of her family. Her husband, Herbert, is pictured on the left.

(To Myers) This is him here.

MYERS: Mm hm. He had thyroid cancer, died October, it was 9 years.

FITZ PATRICK: Nine years ago.

MYERS: Mm hm.

FITZ PATRICK: There's no proof the accident at Three Mile Island killed Herbert Myers. But his widow is convinced it did.

MYERS: I still believe, yeah, that it had something to do with it, because 3 years after my husband died my son got cancer, too.

FITZ PATRICK: Her son's thyroid cancer is currently in remission.

(Shifting)

FITZ PATRICK: Ms. Myers gets up from the couch where we've been sitting and takes me to her bedroom.

(A door opens)

FITZ PATRICK: From the closet, she pulls out what is perhaps the strangest piece of evidence suggesting her farm was hit by radiation.

Local resident Annie Meyers holds a two-headed calf that was stillborn on her family farm near the Three Mile Island Plant two years after the accident. The family preserved the heads to show to curious neighbors. Ms. Meyers' husband died of thyroid cancer several years after this calf was born. Her son also developed thyroid cancer, which is currently in remission. The family did not evacuate during the accident, remaining to care for their herd of dairy cows. Ms. Meyers is uncertain if the accident caused the genetic mutation in this calf, or the cancers in her family.(Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

(To Myers) Oh my God.

(The door shuts)

MYERS: This is the 2-headed calf.

FITZ PATRICK: Oh.

A stillborn calf with 2 heads, born 2 years after the accident. The family had a taxidermist preserve it.

(To Myers) It's almost like Siamese twin heads.

MYERS: Mm hm. Yeah, they both have eyes. They both have a nose, but only, like, 2 ears.

FITZ PATRICK: Joined at the back of the head.

MYERS: Right.

FITZ PATRICK: There's no proof that radiation from Three Mile Island caused this bizarre mutation. In fact, quite a few 2-headed calves have been born elsewhere in the US. Still, the image of this animal haunts this region, underscoring the lingering fear about what happened here 20 years ago.

(Traffic and bird song, horns)

FITZ PATRICK: Today, Middletown, Pennsylvania, looks like any other American town. Officials had feared a devastating exodus and a crash in housing prices. That did not occur. In fact, clean-up work at the plant created high-paying jobs.

(Humming continues)

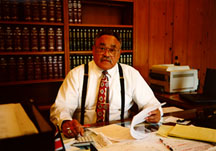

Former Middletown, Pennsylvania Mayor Robert Reid, who helped evacuate pregnant women and pre-school-age children after radiation releases from the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. Today, citing what he feels is a rash of cancer in his town, Mr. Reid feels that all residents should have been evacuated. (Photo: Terry Fitzpatrick)

FITZ PATRICK: Many people also feared the restart of Three Mile Island's other nuclear reactor, which had been idled for refueling when disaster struck its twin. But it's been running without incident since 1985, and even former Middletown mayor Robert Reed feels it's safe.

REED: There's one thing we have going for us. We know how to run a plant now. There are plants all over this country. They never had an accident. There's one out there waiting to happen. But I don't think it'll be at this plant again.

(Traffic)

FITZ PATRICK: For Living on Earth, I'm Terry FitzPatrick in Middletown, Pennsylvania.

(Traffic continues up and under)

TMI Today

"I think the best way to put it is that there were very poor communications at the time. We weren't able to get clear, accurate information out to the media and the public. ... And at that point the media went to other sources for their information." - Tom Kauffman

CURWOOD: With new procedures and safeguards, the odds of another accident at Three Mile Island are extremely low. And so far, only one of many medical studies has been able to point to any lasting health effects. But the credibility of the nuclear industry remains low. And many wonder if present science is good enough to detect the health effects of the kind of release of radioactivity that took place here 20 years ago. So there's still a lingering unease here about what happened.

(Air monitor motors)

KAUFMAN: Well, we're outside our visitor center, Three Mile Island visitor center, and what you're hearing are some continuous air monitors. These are part of our environmental monitoring program.

Tom Kauffman with Living on Earth's Steve Curwood inside the control room training simulator at Three Mile Island. The simulator is an exact replica of the working control room inside the plant, and is used to train operators in emergency procedures. (Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

CURWOOD: Tom Kaufman is one of the people responsible for the image of safety and efficiency that the operators of Three Mile Island try to project today. And on this sunny but cold March afternoon, he's showing us one of several new mechanisms installed at the plant since the accident. Equipment like these air quality monitors, that transmit air radiation levels not just back to the technicians inside the plant, but also to the nearby county courthouse, so that the public can monitor the readings independently. Tom Kaufman has been with the general public utilities for more than 20 years. Today he's a media and community relations representative, but on March 28, 1979, Mr. Kaufman was an equipment operator at Three Mile Island. He arrived for work about 7 that morning. Alarms were already sounding. He was told there was a problem down at Unit 2, which in retrospect he says was the understatement of the day. Within hours, he and other workers were evacuated from the building. But Mr. Kaufman says he remained confident that everything would turn out all right.

KAUFMAN: The only time that I felt some apprehension was actually when I went home and was watching the television, and you were hearing about all these possible things that might happen. I found that interesting, that I would hear something, I'd call the control room and say hey, the media's saying that the plant can blow up.

CURWOOD: So the press really blew this thing up beyond what really happened here..

KAUFMAN: I won't go that far. I think the best way to put it is that there were very poor communications at the time. We weren't able to get clear, accurate information out to the media and the public. We lost our credibility as far as providing accurate information. And at that point the media went to other sources for their information. So it's just, the flow of information and communication at the time was very poor. And that led to problems on both sides.

CURWOOD: Do you think that nuclear power got an unfair, bad rap out of this?

KAUFMAN: One of the lessons learned as a result of the accident was that clearly the people who lived around Three Mile Island, and many others in our nation, didn't have a good understanding of our technology, what we were doing, and the relative risks. We've learned a lot since then. The nuclear industry in this country has greatly improved. It's safer, it's more efficient, more reliable than ever. Whether there will be growth in this industry, in this country in the future, remains to be seen. But it is growing elsewhere in the world, because there is confidence in the technology.

CURWOOD: Now, your company has settled with some, what, 300 plaintiffs, folks who sued fairly early on. I think the amount is $14 million. But your company now is fighting some 2,000 others who are still suing. Why settle with some and not the others?

KAUFMAN: The original suits that were filed, I believe were stress-related. The other lawsuits that are involved are alleged health effects related to the radiation that escaped the plant. So there is a definite difference between the 2 sets of lawsuits. And a Federal judge in Harrisburg dismissed all those cases due to a lack of evidence that any of the plaintiffs had been exposed to enough radiation to cause the health effects that they claimed. Those are currently in the Court of Appeals.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you about this. I understand that in March of 1998, you had an emergency drill here, inside the plant, that would have warranted, I understand, a general alarm. So why didn't your people, during this drill, recognize that the alarm should have been called? Some people would say, boy, we're worried about that, we don't think that they've learned their lesson here.

KAUFMAN: We have performed dozens of drills, graded drills, for the NRC, very well. In that particular case, we didn't perform very well, certainly not as well as we should have, and not as well as we wanted to. We took our eye off the ball, you might say. And we're not saying we're perfect. No one is. I think it's important that when you do make mistakes, it's your response to those mistakes. And our response to the drill that we did not perform well on was to take a long, hard look at why we didn't perform well. We increased our training. And we certainly did very well in the next drill, and we have since.

CURWOOD: Well, Tom Kaufman, thanks for taking this time with us today.

KAUFMAN: You're welcome.

A Resident Reminisces

Elsie Weaver, Bonnie Valentine and Dale Weaver show Living on Earth's Steve Curwood the former site of Ms. Weaver's family farm house. Her family had farmed the land for generations, before the Three Mile Island nuclear plant was built in the 1970s.

CURWOOD: We say goodbye to Tom Kaufman and walk a few hundred feet to a parking lot to meet a woman with a different view of this nuclear facility. She takes us up a hill behind the visitors center, and points to a field now landscaped with huge towers that carry electric power from TMI.

VALENTINE: If you look straight out there you can see the little fenced-in cemetery. See straight out there? That is the family cemetery, right out there.

CURWOOD: For 4 generations Bonnie Valentine's family farmed the land on and around Three Mile Island. Her grandfather was known county-wide for his watermelons and cantaloupes. That is, until the family homestead was sold and torn down to make room for the nuclear plant. Bonnie Valentine was 5 months pregnant with her second child, and outside washing windows on the morning of the accident. By the afternoon she was gone. She spent 2 weeks in a motel in York some 15 miles away, waiting out the crisis. When she returned she says her home town just wasn't the same.

VALENTINE: This little corner of the world has always been a safe and secure haven. The things that happened in the rest of the world did not happen here. And suddenly we were the focus of the entire world. I mean, it was really a change. Forever.

CURWOOD: What are some of the biggest things that changed forever for you?

VALENTINE: The safety and security that we felt in living here. That was certainly a big change. And as I look back upon it, we were really blissfully ignorant of how serious it could have been. Had we known, I think we would have been a lot more panicked. You know, here were all of our families, all these people that are so important to us. And, you know, they would have been lost to us. It's more frightening to me now than it was at the time. There's also, in this area, a strong faith. We believe that God was in control. And we're thankful, we're very thankful that it was not worse. It certainly could have been.

CURWOOD: How do you feel about this place, being here?

VALENTINE: Well, my husband worked on the Island for 7 years, and the whole time they were working on it I would tell him I liked it much better when it was just a peaceful little island in the middle of the Susquehanna River. You know, as children, I can remember my dad had a little boat, and he would take us over there, and we would hunt arrowheads. And I bet most of the little kids in Middletown had that experience. That it was just a wonderful place to go to and explore. And to me, that was a real loss.

CURWOOD: How would you say things are now between the nuclear power plant and the community? How would you describe that relationship.

VALENTINE: (sighs) I think we would probably be reluctant to believe anything they said, really. I would say there's a real credibility issue, because we know that they weren't totally honest with us 20 years ago when it happened. And once that trust is destroyed and you can't believe in the honesty of a corporation, you know, you're just not real comfortable with hearing what they have to say.

CURWOOD: Is this a good place to live? Do you want your children to stay here? Would you tell friends to come and live here?

Harrisburg, the state capital of Pennsylvania, is ten miles upstream from the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant. The plant's massive cooling towers and plume of water vapor are clearly visible from Harrisburg, along the banks of the Susquehanna River. (Photo: Terry FitzPatrick)

VALENTINE: Unh... That's a hard question. I love it because it's home to me. I want my children to stay here because I want them close to me (laughs), selfishly. As far as other people coming in? I don't know that TMI is really a threat any more. I don't know that it is. If it is we certainly don't hear about that. So I don't know, I really can't say if I would advise other people to come here or not. I really don't know.

CURWOOD: Why is this anniversary important, 20 years after?

VALENTINE: You know, we are all here. And we need to celebrate that. And I also think it's important that the world does not forget what happened here. And I think that we need to be remembering the potential for these kinds of things. When we move this kind of stuff into communities, we need to be more cognizant of the potential for disaster and for disruption to the lives of all the people who live here.

CURWOOD: Bonnie Valentine is a teen parent educator who lives with her husband and their 2 children in Middletown, Pennsylvania.

(Music up and under)

Culture Melt-Down

Once the immediate danger posed by the accident passed, Three Mile Island became grist for talk show hosts and comedy troupes.

CURWOOD: It didn't take long for the accident at Three Mile Island to become part of the American experience. To knit itself into the fabric of the nation's popular culture. In fact, the process began nearly 2 weeks before the actual incident. When Hollywood released its version of a nuclear meltdown, in a film called The China Syndrome.

(Noise in the background)

FONDA: The what?

MAN: If the core is exposed for whatever reason, the fuel heats beyond core heat tolerance in a matter of minutes. Nothing can stop it. And it melts right down through the bottom of the plant, theoretically, to China. But of course as soon as it hits ground water it blasts into the atmosphere and sends out clouds of radioactivity. The number of people killed would depend on which way the wind is blowing, render an area the size of Pennsylvania permanently uninhabitable, not to mention the cancer that would show up later.

CURWOOD: The scenario played out in the move was so similar to the reality of Three Mile Island that in retrospect the feature film is often described as documentary-like.

MAN 1: Operations.

LEMMON: This is Jack Godell. We have a serious condition. You get everybody into safety areas and make sure that they stay there.

(Hangs up)

PA SYSTEM: All personnel, proceed directly to safety areas. Caution. Code 6, this is not a drill. This is not a drill.

SNL ACTOR 1: What is happening?

(Buzzer)

SNL ACTOR 2: I'll tell you what's happening. The Pepsi Syndrome.

(Audience laughter; music and applause)

CURWOOD: Once the immediate danger posed by the accident passed, Three Mile Island became grist for talk show hosts and comedy troupes. In this Saturday Night Live spoof, a soft drink spilled on a control room panel triggers a meltdown scare at the Two Mile Island nuclear plant. With art imitating life, President Jimmy Carter visits the crippled facility and gets a little too close to the melting core.

(Buzz, shutting)

SNL ACTOR 1: Mr. President! You're glowing!

SNL ACTOR 2: Jimmy!

ACKROYD: Don't touch me! I'm a nuclear engineer and I'm pretty worried right now.

(Audience laughter; fade to music: "Takin' It To The Street")

CURWOOD: The accident at Three Mile Island also galvanized popular opposition to nuclear power. People took to the streets, and pop stars took to the stage. A group called Musicians United for Safe Energy, or MUSE, gathered for 5 nights at benefit concerts in New York City in September of 1979. The proceeds went to pro-solar organizations, as the likes of Bruce Springsteen, James Taylor, and Bonnie Raitt wailed against the perils of splitting the atom.

(Singing: "Oh... [inaudible]" "One more time!" Audience applause)

CURWOOD: Popular culture references about nuclear safety waned in the years following Three Mile Island, but they haven't disappeared.

(Theme music from The Simpsons up and under)

CURWOOD: America's favorite animated family lives in the shadow of a nuclear reactor, and its patriarch Homer Simpson, works at the plant owned by the conniving Mr. Montgomery Burns.

BURNS: Homer, they're trying to shut us down. They say we're contaminating the planet.

SIMPSON: Well, nobody's perfect.

BURNS: Can't the government just get off our backs?

CURWOOD: One of our favorite take-offs on the dos and don'ts of nuclear safety is an unofficial Three Mile Island version of the popular board game Risk.

(Suspenseful music)

CURWOOD: The object of the game, of course, is global domination. But if you roll the dice and come up with double-4s, 5s, or 6s, you melt the nuclear core and turn your territory into a wasteland.

(Nuclear explosion)

MAN: No, operator, give me the number for 911!

(Music up and under)

CURWOOD: And for this week that's Living on Earth. Next week: down but not out: the nuclear industry says it has a whole new generation of safe and inexpensive reactors ready to meet the world's energy needs.

MAN: The AP-600 is designed such that even if there were a problem, unlikely as it is, an operator could literally walk away because natural systems such as gravity will take over the whole operation.

CURWOOD: The future of nuclear power next week on Living on Earth.

(Music up and under)

CURWOOD: our program on Three Mile Island was produced by Terry FitzPatrick, Liz Lempert, Jesse Wegman, Miriam Landman, and Alexandra Davidson, with thanks to Steve Kennedy, Central Pennsylvania Magazine, and WITF Radio in Harrisburg. Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. Our production staff includes George Homsy, Daniel Grossman, and Stephanie Pindike, along with Roberta deAvila, Peter Shaw, Leah Brown, Bree Horowitz, and Barbara Cone. We had help this week from Aly Constine and Chris Burnick. Michael Aharon composed the theme. Eileen Bolinsky is our technical director. Peter Thomson heads the Western Bureau. Our senior editor is Joyce Hackel, and Chris Ballman is the senior producer. I'm Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

(Music up an under)

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the W.K. Kellogg Foundation for coverage of sustainable agriculture; the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation; the National Science Foundation for coverage of science in the environment; the David and Lucile Packard Foundation; and the W. Alton Jones Foundation, promoting new economic approaches to advance environmental protection and human prosperity; www.wajones.org.

NPR ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

The preceding text has been professionally transcribed. However, although the text has been checked against an audio track, in order to meet rigid transmission and distribution deadlines, it has not yet been proofread against tape.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth