August 6, 2004

Air Date: August 6, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

California Government Overhaul

/ Ingrid LobetView the page for this story

When a team convened by California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger went hunting for ways to cut government and pull the state out of its crushing debt, they suggested dissolving the legendary Air Resources Board. Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports. (04:00)

Ford Boycott

View the page for this story

If you happened to page through the New York Times lately, you might have noticed a full-page ad asking consumers to boycott Ford vehicles. Environmental groups led by the Bluewater Network placed the ad in response to what they see as Ford’s lax efforts to better its fuel economy. Host Steve Curwood talks with Bluewater’s director Russell Long about the extent of the ad campaign’s success. (06:00)

Advocate Ads

/ Joe TherrienView the page for this story

Non-profit advocacy groups haven’t always been able to reserve full-page advertising to promote their messages. Rates have traditionally been too high for start-ups and non-profits to afford. But Joe Therrien says major newspapers like the New York Times are starting to offer special rates for non-profits that may change the face of advertising. (02:30)

Toxic Trailway

/ Guy HandView the page for this story

Producer Guy Hand rides a new bike trail through the famously polluted former mining regions of North Idaho. The trail is a recreational Superfund site, designed by the EPA. (16:00)

Health Note/Location, Location

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on a study that links community design to your risk of obesity. (01:20)

Listener Letters

View the page for this story

Comments from our listeners on some of our recent broadcasts. (02:30)

Have No Fear

View the page for this story

Thirty years ago, Frances Moore Lappe proposed a diet for the planet that made her an international food expert. She blamed the world’s food shortages not on a scarcity of food, but a scarcity of democracy. Her new book identifies fear as the underlying cause of most of today’s environmental problems. She and Jeffrey Perkins talk with host Steve Curwood about their new project, “You have the Power: Choosing Courage in a Culture of Fear.” (12:30)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Russell Long, Frances Moore Lappe, Jeffrey Perkins, Joe ThferrienREPORTERS: Guy Hand, Ingrid LobetNOTE: Jennifer Chu

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living On Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. In northern Idaho the Environmental Protection Agency is trying to make the best of a bad situation. The EPA has poured asphalt over an old mining rail line to make one of the longest bike trails in the nation - and some folks are pleased with the results.

MALE: We've been on rail trails all over the country and this is the best rail trail I've ever been on.

CURWOOD: But others say the government has just paved over the problem and they don’t think attracting tourists to an environmental hazard is such a good idea.

TONI HARDY: It's beautiful, but it's contaminated and this is a Superfund; it's not a recreational trail.

CURWOOD: Turning poisoned land into a playground. Also, the independent agency that regulates air pollution in California and sets trends for the nation is now in the crosshairs of the Schwarzenegger administration. Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

California Government Overhaul

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

|

|

Now their examination is done and they claim the nation's most populous and indebted state could save an average of $6 billion a year over the next five years by eliminating or consolidating many state agencies. But as Living on Earth’s Ingrid Lobet reports, one recommendation may come as a shock to clean air advocates around the nation. LOBET: The budget review culminated in a giant warehouse chosen for its symbolic value: a place where the state currently spends, or wastes, some $94,000 a month storing old furniture and computers. Amid fanfare, the reviewers presented their six-inch sheaf of cost-cutting recommendations. MALE: Governor (CLAPPING) this is volume one (CLAPPING) and this is volume two. (WILD CLAPPING AND CHEERING) LOBET: Many Californians, including environmentalists, agree the state could well stand to reduce agency overlap and eliminate unnecessary boards. But most were surprised to see the California Air Resources Board proposed for elimination. Tim Carmichael is executive director of the Coalition for Clean Air. CARMICHAEL: The suggestion that we would eliminate one of the most effective agencies in the world, not just the state, but in the world, at reducing air pollution is really curious. LOBET: The California Air Resources Board is credited with pushing for new, clean technology that then becomes the standard across the country -- cleaner gasoline, cleaner boat engines, lawnmowers, paints. The results are measured in tons of pollutants kept out of the air. Several people I spoke with think the budget reviewers swept the Air Resources Board into their broader recommendations to eliminate 118 boards and commissions, which can be quite costly to run. But some people, like Gail Ruderman Feuer of the Natural Resources Defense Council, think this is not simply a case of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. FEUER: I assume industry had a direct hand in it and it was very purposeful, but I don't know specifically who would speak with whom. Clearly the auto industry would be thrilled with this recommendation LOBET: Or maybe not. One industry source wasn't so sure that dissolving the Air Resources Board would mean an improvement -- there would still be an air pollution division but it would be under the state's environment chief, Terry Tamminen. And could the proposed elimination of the Air agency be an attempt to kill its new effort to regulate carbon dioxide in tailpipe exhaust? No way, says Tamminen. The governor's committed to it. TAMMINEN: He said in the Los Angeles Times and other places that he fully supports California's landmark greenhouse gas law and intends to defend it from the anticipated court challenges along the way, those are literally his words. LOBET: Tamminen says any department reorganization might yield greater scrutiny of industry. And he rejects the refrain that environmental regulation means a steady loss of business in California. He cites the example of a new Fox animation studio that would have brought lots of new jobs. TAMMINEN: But they ultimately chose to build it in Arizona and the top two reasons that they cited was not the cost of doing business or environmental regulation, it was rather the lack of it – it was traffic and air pollution. They didn't want to raise their families in the community as they found it in southern California. LOBET: The recommendations of the budget reviewers are in any case very preliminary. They will have to pass through many screens, a special panel, public hearings, the governor, and then the legislature. And if he doesn't find success there, Arnold Schwarzenegger may try to bring the overhaul, in some form, directly to the voters. For Living On Earth, I'm Ingrid Lobet in Los Angeles.

Ford BoycottCURWOOD: Joining me now is a man who has helped craft and push through new air pollution laws in California, Russell Long. He’s director of the Bluewater Network in San Francisco, and his group has been heavily involved in efforts to reduce emissions from ships and increase fuel efficiency in the auto industry. His latest project takes aim at the Ford Motor Company in the form of a full-page ad that appeared recently in the New York Times. The ad lists what the group considers Ford’s failings towards the environment, and goes so far as to ask people to boycott Ford vehicles. Russell Long, welcome. LONG: Thank you very much. CURWOOD: Could you describe this ad for us as it appears in the New York Times? LONG: Well, the first ad we ran depicts Bill Ford with an extended Pinocchio nose. And it goes on to mention that Mr. Ford has made various pledges to protect the environment, including the pledge on increasing fuel mileage 25 percent, and in year 2003 he reneged on that. And we subsequently ran another ad recently which actually shows the fuel mileage of the top three auto manufacturers in the U.S. – Ford, GM, and Toyota – and Ford is at the bottom and getting worse. And it’s been continuing to get worse for the past four years, ever since Bill Ford took over the company. And at the very bottom of the ad, of course, we have coupons to cut out that readers can send to us. We forward those to Mr. Ford, that state, “I pledge not to buy a Ford until you clean up your cars and you go to Congress and ask them to voluntarily increase the nation’s auto mileage efficiency. Until then the planet can’t afford a Ford.” CURWOOD: Now, what kind of response did you get from Bill Ford, the CEO of Ford Motor? It seems that there’s a fine line between a group’s right to speak and questions of slandering or defaming him or holding him up to public ridicule. What kind of legal action has there been in response to these ads? LONG: Well, they sent us a cease-and-desist letter from their attorneys, and we had to meet with our own attorneys to find out whether or not we’d violated the law. And our attorneys said no. Other than one extremely minor copy edit in our ad, they thought we were just fine. And so we let Ford know that we were happy to make the minor copy edit change. But, you know, unfortunately I think this is not the way you do business today. I think Ford has invested too heavily in attorneys rather than going out there and just getting the engineers to do the job right in the first place. CURWOOD: I notice there’s no Pinocchio depiction in your recent ad – how much is that a function of the request, the letter from Ford, asking for a cease-and-desist in using that kind of imagery? LONG: Well, it has more to do with the New York Times, unfortunately. They received some phone calls, apparently, from Bill Ford’s office, and there was a great deal of gnashing of teeth. And the New York Times decided they didn’t want to run that Pinocchio ad anymore. They’re okay with caricatures but they felt this one went a little farther than they liked. As far as the new ad, you know, we were not going to continue to run the Pinocchio nose anyway. I think the important thing here is the American public needs to understand this company is not a leader, they are a follower. And they are the worst of the bunch when it comes to fuel mileage. CURWOOD: We have tried to be in touch with the Ford Motor Company about your advertisements, and they have declined to sit for an interview with us. But we should point out in Ford’s favor that they have taken some green initiatives. And they are building a hybrid SUV, the Ford Escape, which on its own gets pretty good mileage. Shouldn’t Ford get some kind of credit for taking these efforts to move forward? LONG: I think they’ve done a great job with that vehicle – I think it will be getting 30, 35 miles a gallon, and that’s a big improvement over what we see with typical SUVs. But the problem is it’s not going to do anything on a large scale to decrease their emissions or to increase their fuel mileage averages. And until we see that hybrid technology in every single vehicle which they are building, it’s really not going to do a tremendous amount. CURWOOD: What kind of response have you had to these ads? In particular, how many customers do you think your efforts are turning away from Ford? LONG: Well, we’ve been receiving hundreds of letters from around the county, people signing these pledge coupons saying they’re not going to buy Ford vehicles. And it’s important that Ford no longer be perceived as having an environmental halo. In fact, that halo rightfully belongs to Toyota and Honda, who really have done tremendous things for the environment over the past ten years. And I think Ford is headed in the right direction with this one hybrid they have. But until they have a fleet of them, unfortunately we’re not going to be where we need to go. CURWOOD: Russell Long is director of the Bluewater Network in San Francisco. Mr. Long, thanks for taking this time with me today. LONG: My pleasure. Related link:

Advocate AdsCURWOOD: It wasn’t long ago that Bluewater and other nonprofit groups were not able to place ads in such high-profile publications like the New York Times. That’s because rates for prime advertising space were expensive. But today major newspapers and magazines are making room for cash-poor nonprofits and advocacy groups. The kinds of groups that Joe Therrien represents. He’s an account executive with the Public Media Center, the ad agency responsible for placing the Ford ad in the New York Times. Mr. Therrien welcome. THERRIEN: Thank you very much, Mr. Curwood. CURWOOD: Now, I understand you’ve been in the ad business for quite a while. How have you observed the advertising market opening up to advocacy groups that may be on a shoe-string budget? THERRIEN: It’s a significant change. It makes available powerful podiums like The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, at prices that nonprofits can afford that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to use. CURWOOD: Now, I’m wondering what exactly these special advertising rates are that are being offered to nonprofits? THERRIEN: Well, if you wanted to buy a full page in The New York Times, the rate card tells you it would cost you net $127,000. But if you are a nonprofit or advocacy group that doesn’t have a tight timeline, then, if you were a client of mine, I would suggest that you look at what’s called a “standby rate.” You give the Times the authority to run your ad in the window of a week or two weeks or three weeks. You could get that same ad for $39,000. CURWOOD: Now, in many cases, of course, these messages could be quite aggressive and confrontational. What’s been some of the most particularly challenging cases that you’ve tried to present, in terms of getting these ads to pass muster? THERRIEN: Well, we had an ad several years ago that called on readers to boycott Japanese goods because Japan was the leading purchaser of Tiger penises, and its popularity as a medicine was causing the destruction of tigers throughout Asia. There was a very considerable fight with the editors of a major West Coast newspaper. Ultimately, they finally agreed to run it, since there was nothing lascivious about the ad. It was simply a statement of the part of the anatomy of the animal that was causing the destruction of the entire animal. It’s good to have that kind of a test because they’ll make you prove your point. If you can substantiate the proof of what you’re saying, you are not going to find resistance you can’t overcome. CURWOOD: Joe Therrien is the principle with the Public Media Center in San Francisco. Thank you so much, sir. THERRIEN: Thank you, Steve, I appreciate it. CURWOOD: The Ford Motor Company declined to comment for this story but did send us a list of its environmental commitments. These include investments in hydrogen fuel cell and biodiesel technologies and hybrid electric vehicles. And later this fall the company’s first “no compromise” hybrid electric SUV, the Escape, is expected in showrooms. But in Ford’s recent corporate citizenship report, the company noted that the fuel economy for its U.S. fleet will decrease by more than two percent this year. Ford says the reason for the decrease is due to its decision to cut production of its ethanol burning vehicles. Coming up: From toxic trail to bike path. The EPA paves over a Superfund site and invites tourists and controversy. Keep listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Govinda “Tu M’aimes” EROTIC RHYTHMS FROM THE EARTH (Earthtone – 2001)]

Toxic TrailwayCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Throughout the West communities are trying to build new, recreation-based economies over the old ones based on mining. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes is a literal example. This new bike trail in North Idaho converts an old mining-era rail line to recreational use. It’s one of the longest Rails to Trails projects in America. But beneath the miles of fresh asphalt there’s also toxic mining debris strewn the length of the line. Indeed, some call it a recreational Superfund site, a trail for bikers, hikers and skaters built to contain contaminants and promote tourism. Producer Guy Hand cycled the Trail of the Coeur d'Alenes to see if this exploited piece of the American west can bury its past and pave the way to a brighter future. [BANJO MUSIC AND CROWD NOISE] HAND: It's not surprising that when the Coeur d'Alenes bike trail officially opened in June, people in the North Idaho mining towns that dot it's path were ready to celebrate. SIJOHN: Okay, ladies and gentlemen, we're getting started here. HAND: This 72-mile long black strip of asphalt running through the mountains is a symbol of hope for residents who've been living under the label "Superfund Site" for over 20 years—a label that many says has been toxic to tourism despite the region's stunning beauty. MOORE: And today on behalf of Union Pacific I'd like to present to the citizens of the entire Pacific Northwest, the state of Idaho, and Coeur d’Alene tribe, I present to you the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes. [CLAPPING] HAND: Ed Moreen is project manager with the Environmental Protection Agency. MOREEN: When we were still constructing the trail, it was evident that the people in the basin were excited about the trail. In fact, when the contractors were placing the asphalt, it was still steaming and people were right behind the paver wanting to ride down the path on their bikes. [SOUND OF DERAILLEUR SPINNING, PREPARING TO RIDE] HAND: At the trail's eastern end, where I begin my bike ride, the rail line doesn't hide its polluted past. A sign explains how tailings laced with lead, cadmium, zinc, and arsenic were used to build the rail bed itself. Ore dust also drifted out of open or damaged rail cars. It spilled from derailed ones. It piled up in loading areas. Over a century, heavy metals so contaminated the rail line that in places soil measured 80 times the EPA safe lead level. [SOUND OF MOUNTING BIKE, SHIFTING GEARS THEN RIDING] HAND: This part of the trail goes right through the mining town of Kellogg. This is the town that is home to the Bunker Hill Mine and Smelter, where some of the worst pollution occurred during the mining era. You can see on the hills around the town the trees are still stunted from the tainted smoke that came out of the smelters.

[BIRD SONG] HAND: But soon the trail leaves the more obvious signs of mining pollution behind and rolls through a landscape that looks pristine, but still isn't. Lead concentrates under this part of the trail average nearly 8,000 parts-per-million, or eight times the Superfund site's safety standard. HAND (ON BIKE): Gorgeous meadows off to my left. HAND: The stubborn beauty of this place—the steep mountains, lush meadows, and shimmering waterways—has the power to wash away concerns about lead tainted soil. And that's just fine with Joe Peak, a businessman with high hopes for the economic future of these mining towns. [BAR CROWD, CASH REGISTER] HAND: The bike trail runs right in front of Peak's bar and restaurant, The Snake Pit. PEAK: Right outside we have two bike racks and those bike racks on weekends are full. Usually on Saturday afternoons and Sunday afternoons it's not unheard of for 50 to 60 percent of our business to be trail related. Let me get some customers… HAND: Peak's a little distracted on this early Saturday evening. The place is packed. He figures the trail is adding a hundred thousand dollars a year to his business. PEAK: We could get anywhere from 75-150,000 visits per year and we feel that the spin off on that could be as high as $14 million a year in the Silver Valley and the corridor from Mullen to Plummer. Need some change? [BAR SOUNDS, THEN BIKING] HAND: Just west of Peak's place the trail heads into some of the most stunning country of the ride.

HAND: A little further along I meet a young woman pulling her son in a kid cart behind her bike. HAND: Hi. Do you ride the trail very often? WOMAN: No, this is my first time on the trail. I'm actually from Colfax, Washington. HAND: Oh really? Who's riding in back? WOMAN: This is Adam. He is two years old. So he's not quite ready for a bicycle yet. HAND: So what do you think of the trail? WOMAN: Oh, I like it. It's great. How do you like the trail? HAND: I think it's amazing. It’s gorgeous. HAND: I find myself forgetting that just under the 2 1/2 inches of asphalt I glide over there's lead, arsenic, and more. Lead is a neurotoxin. It impairs cognitive abilities, especially in children. Arsenic, a potent carcinogen, can cause skin lesion and cardiovascular problems. But the EPA says the trail is perfectly safe. As long as you obey the occasional signs warning you to clean your hands before eating, stop only at designated rest areas, and stay on the asphalt. [RIVER SOUNDS] HAND: Yet, it's tempting to wander off. On this hot afternoon, a dip in the cool Coeur d’Alene River is hard to resist. The river and lake parallel nearly the entire length of the trail, but hold some of the highest concentrations of mine poisons in the nation. Still, a little further along, I see two young girls fishing, ankle deep in the river.

HAND: Clifford Villa, assistant regional council for the EPA says that it's often easier to control the human usage of a contaminated area than to remove the contaminants themselves. It's an approach the EPA has employed at Love Canal and many other national Superfund sites. And here, when EPA determined it was impractical to remove the entire 72 miles of railbed contamination, a bike trail capping the problem seemed the best solution. VILLA: One thing that the Rails to Trails program allows us is to insure the use of an area for recreational purposes. We actually did a risk assessment before the trail was constructed that estimated that people could use the trail up to 24 hours per week. That's some pretty intensive running or biking without any cause for concern about existing contamination. HAND: But what about those two girls I saw fishing off the trail? VILLA: Before the trail was built, people were using this corridor anyway. So we know people were here and we’re not going to keep people off. We're just going to try to control that use and promote safe uses as much as possible. HAND: Villa says the EPA can't eliminate all risk, but since people are going to use the area anyway, he believes the trail has made things much safer. In fact, he considers the trail one of his biggest Superfund successes. VILLA: It's very satisfying to not only take something away in the form of contamination, but to leave something behind in terms of something that all the people of this area can appreciate from here on. [OUTDOOR SOUNDS] SCHLEPP: As you can see, the trail actually comes by our hay shed there… HAND: Farmer Mike Schlepp shows me where the trail of the Coeur d’Alenes cuts through his 550-acre farm at about mile post 33. He's a vocal critic of the trail and doubts the wisdom of attracting tourists to a Superfund site. SCHLEPP: All of us landowners have had problems with people getting off the trail and wandering on to private property. HAND: The EPA's own study admits that the trail will probably entice visitors to pick berries and wander off trail to hike, fish, or swim. The study says those quote off-trail exposures fall beyond the scope of the trail plan. SCHLEPP: We actually had a family that left the right of way and were attempting to set up an overnight camping spot with their children. One of the children was still an infant. And we did explain that they were actually having their children recreate on a heavy metals site and asked them to leave and really they were quite belligerent. Regretfully, they just went down the trail about a mile and a half and set up camp for the night just off the right of way. HAND: The EPA says trail managers will catch violators like these, but Schlepp argues that the former owner of the line, Union Pacific railroad, should have removed the contamination altogether—just like any other landowner. SCHLEPP: I have not seen anywhere in Superfund law that it says that if a polluter can actually make the problem big enough that he can be relieved from cleaning it up because it's just too big. HAND: The EPA is expanding its Superfund work from the worst hit mining towns to the entire basin. But now that the railroad is enshrined as a bike trail, the cleanup Schlepp hoped for will never reach his property. He says that every time it floods, and it floods frequently here, the contaminants contained in the trail get flushed into his fields. SCHLEPP: They will eventually have the entire basin cleaned up except for this 150-foot wide swath of contamination that goes right through the underbelly of the basin. [SOUND OF BIKE RIDING]

|

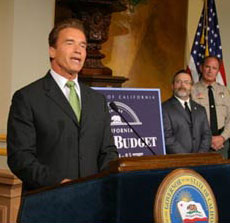

(Photo: State of California)

(Photo: State of California)

The bike trail runs through this landscape. (Photo: ©Guy Hand Productions)

The bike trail runs through this landscape. (Photo: ©Guy Hand Productions)  A warning sign on the trail with the Coeur d’Alene River in the background. (Photo: ©Guy Hand Productions)

A warning sign on the trail with the Coeur d’Alene River in the background. (Photo: ©Guy Hand Productions)  A sign praising the trail in the village of Harrison, Idaho. (Photo: ©Guy Hand Productions)

A sign praising the trail in the village of Harrison, Idaho. (Photo: ©Guy Hand Productions)