February 8, 2013

Air Date: February 8, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

US Carbon Emissions At A New Low

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

US carbon dioxide emissions have fallen by 13% in the last five years to the lowest levels in nearly two decades. A new study finds that cheap natural gas, along with President Obama’s all of the above energy policy that includes renewable energy and increased efficiency explain the reduced emissions. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports. (05:45)

Waste Heat

View the page for this story

Cities burn a lot of energy and release a lot of heat. A new study finds that enough waste heat rises from cities to influence regional climate, especially in the winter. Host Steve Curwood learns how cities’ heat affects climate from Dr. Veerabhadran Ramanathan, Professor of Atmospheric and Climate Sciences at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (05:20)

Deadly Smog

View the page for this story

Deadly smogs in the mid-20th century caused the United States and Great Britain to pass clean air legislation. Now, Beijing has the world’s thickest smog, and the health problems could be serious. Beijing journalist Jocelyn Ford tells host Steve Curwood about the air she’s breathing. Then, Dr. Tracey Woodruff explains her new study linking air pollution to low birth weight. (08:40)

Science Note: Why We Get Bathtub Wrinkles

/ Annie SneedView the page for this story

Scientists think they have an evolutionary answer to why we get wrinkly fingers and toes after a soak in the tub. Living on Earth’s Annie Sneed reports. (02:05)

Salt Pans

/ Meara SharmaView the page for this story

Harvesting salt is a way of life for thousands of Gujarati villagers in western India, and it's hard work in difficult conditions. As Meara Sharma reports, landowners and middlemen make a handsome profit from salt, but not the villagers who toil in the burning sun. (08:05)

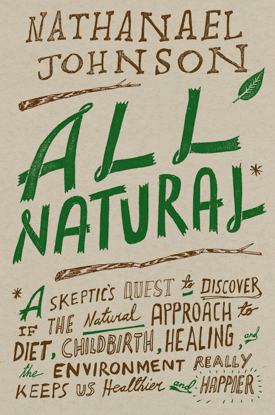

All Natural

View the page for this story

Nathanael Johnson grew up in an California family that didn’t believe in sugar, diapers, or TV. In his debut book, he sets out to see what science has to say about the true health benefits of his parents’ all natural lifestyle. Nathanael Johnson joins host Steve Curwood to discuss his book All Natural. (12:30)

Sounds of Winter

/ Sy MontgomeryView the page for this story

Listen closely. The frigid months of winter have a sound uniquely their own. As commentator Sy Montgomery points out, the cold and gray season’s bareness and rigidity help make its sounds vibrant. (03:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Veerabhadran Ramanathan, Jocelyn Ford, Tracey Woodruff, Nathanael Johnson

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Annie Sneed, Meara Sharma, Sy Montgomery

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. There seems to be little chance of US legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions anytime soon, but emissions have fallen anyway - thanks to cheap natural gas - and renewables.

ZINDLER: We’ve seen the approximate doubling of renewable energy capacity over the past four years. The wind industry set a record by installing over 13,000 megawatts of new capacity.

CURWOOD: But getting all the way down to the long-term goals might be tough. Also lending an ear to the special sounds of winter.

MONTGOMERY: Listen to the voices of the trees. They creak like rusty hinges as they sway in the wind. Sometimes trees will even pop loudly - it can sound like fireworks - their wood expanding and contracting during sudden changes in temperature.

CURWOOD: Well have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around.

[MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm.

US Carbon Emissions At A New Low

Improved fuel efficiency standards and high gas prices have reduced emissions from the transportation sector. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

President Obama has said time and again that he wants an "all of the above" energy mix to help reduce the US dependency on foreign oil - tapping domestic oil, gas, geothermal, biomass and renewables.

Now a new report from Bloomberg New Energy Finance suggests that "all of the above" strategy is also reducing our emissions of carbon dioxide. And that's a good news message for the President as he seeks a new environmental team - he needs leaders for NOAA, the EPA, and the Departments of Energy, Transportation and the Interior.

Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports now on why emissions are shrinking.

BASCOMB: US carbon emissions have gone down by 13 percent in the last 5 years to reach their lowest levels since 1994. But there’s no single answer as to why. Natural gas is a large factor. Developments in technologies like fracking have made natural gas abundant and cheap. Ethan Zindler is a policy analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

natural gas emits roughly half the carbon dioxide of coal for the same energy burned. (Bigstockphoto.com)

ZINDLER: Natural gas last year accounted for 31 percent of US electricity consumption. That’s up from 22 percent just as recently as 2007 and most of that growth has essentially come at the expense of coal generation.

BASCOMB: Historically, King Coal reigned over the US energy mix.

[SONG “COAL KEEPS THE LIGHTS ON”]

BASCOMB: Coal used to keep the lights on but last year natural gas turned on more lights than coal. And natural gas produces the same amount of energy as coal with only about half the carbon dioxide emissions. So that explains a lot of our emissions reduction success.

ZINDLER: But not all of it.

BASCOMB: Again Ethan Zindler.

ZINDLER: The other thing that’s happened is we’ve seen the approximate doubling of renewable energy capacity over the past four years. The wind industry set a new record by installing over 13,000 megawatts of new capacity. Solar is more price competitive than we’ve ever seen it before even on a potentially unsubsidized basis.

Electricity capacity from renewable energy roughly doubled in the last 5 years. (Bigstockphoto.com)

BASCOMB: An electricity analysis in Texas found that wind and solar will be price competitive with oil and natural gas over the next two decades and will likely out perform coal. Renewables are on the rise but they still generate less than 10 percent of our overall energy.

Another reason for the savings is improved energy efficiency.

ZINDLER: In the last 30 years there’s been about a 40 percent improvement in energy intensity in commercial buildings. In the use of energy for heat or for cooling there’ve been some very substantial improvements.

BASCOMB: But improved technology for energy efficiency is only part of the picture. We’ve also changed the way building efficiency is financed. Last year we spent roughly 14 billion dollars to reduce energy use and half of that cash came from utilities. Building owners have a strong incentive to improve efficiency if someone else is paying for it.

Efficiency has improved in the transportation sector as well. In August of last year the EPA raised fuel efficiency standards for new cars. By 2025 they’ll get nearly 55 miles per gallon. Those new standards and gas at more than three and a half dollars per gallon are spurring other change in consumer choices.

ZINDLER: Last year we tracked just under half a million hybrid electric and pure electric sales. Hydrids themselves, the Prius and others are extremely popular now and that represented about 3.5 percent of all automobile sales on the road last year.

BASCOMB: Of course, a less than robust economy could also explain part of our decline in energy use. Some politicians argue that if we reduce carbon emissions our economy will contract as a result. But Lisa Jacobson says that logic doesn’t hold water. She’s president of the Business Council for Sustainable Energy.

JACOBSON: Between 2007 and the first nine months of 2012 we’ve seen GDP increase by 3 percent as a country but our energy related emissions have fallen by 13 percent. Also we show in a similar time period a 6 percent decline in energy use. So clearly we can have strong economic growth and we can still reduce emissions and protect the environment.

BASCOMB: At the 2009 climate conference in Copenhagen President Obama set a goal to reduce US carbon emissions. By the year 2020 emissions must go down 17 percent below 2005 levels. We are more than half way to that goal and on track to meet it but the things we’ve already done were relatively simple. Dallas Burtraw is Senior Fellow at Recourses for the Future.

BURTRAW: Regulators can do a pretty good job of seeing the low hanging fruit and developing regulations to pick that fruit, to harvest that fruit and achieve emission reductions. The fruit that’s higher up in the tree is harder for regulators to see.

BASCOMB: Those fruits at the top of the tree include improved regulation of existing stationary sources like power plants and cement factories. We’ll need to do that and much more to reach Obama’s long-term goal - that’s to reduce emissions 80 percent by the middle of the century.

BURTRAW: I don’t think anyone sees the way to get there from here exactly.

BASCOMB: Yet even if Dallas Burtraw says the path isn’t clear now, he’s optimistic.

BURTRAW: I am confident that we can get there if we start now and do it in a smart way, that provides incentives for the market to play its part in achieving emission reductions.

BASCOMB: But with almost all of President Obama’s green team leaving and spending under pressure on Capitol Hill it’s not certain what incentives will be on the table.

For Living on Earth, I'm Bobby Bascomb.

Related links:

- Bloomberg’s Sustainable Energy in America 2013 Factbook

- Resources for the Future

- Business Council for Sustainable Energy

Waste Heat

View of New York City looking south from Rockefeller Center. (Photo: Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: Now a significant contribution to global carbon emissions comes from cities - from busy offices, idling traffic and lights left on all night. Cities are tightly packed with people and buildings that burn a lot of energy and release a lot of waste heat - enough heat, a new study says, to influence regional climate. Here to explain it all is Dr. Veerabhadran Ramanathan, Professor of Atmospheric and Climate Sciences at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. Welcome to Living on Earth.

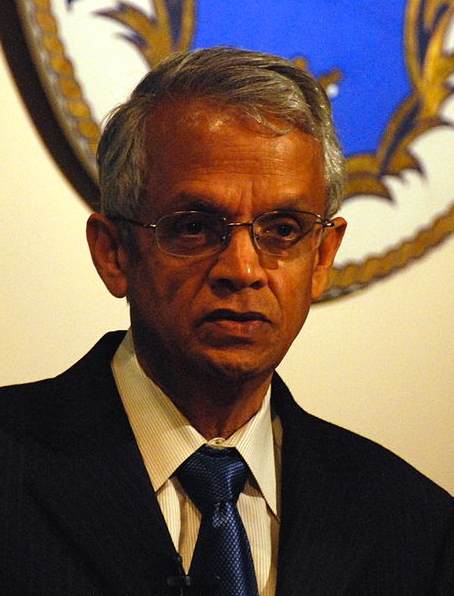

Dr. Veerabhadran Ramanathan, Professor of Atmospheric and Climate Sciences at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. (Photo: Wikipedia)

RAMANATHAN: Thank you very much!

CURWOOD: So how exactly is waste heat from cities affecting climate?

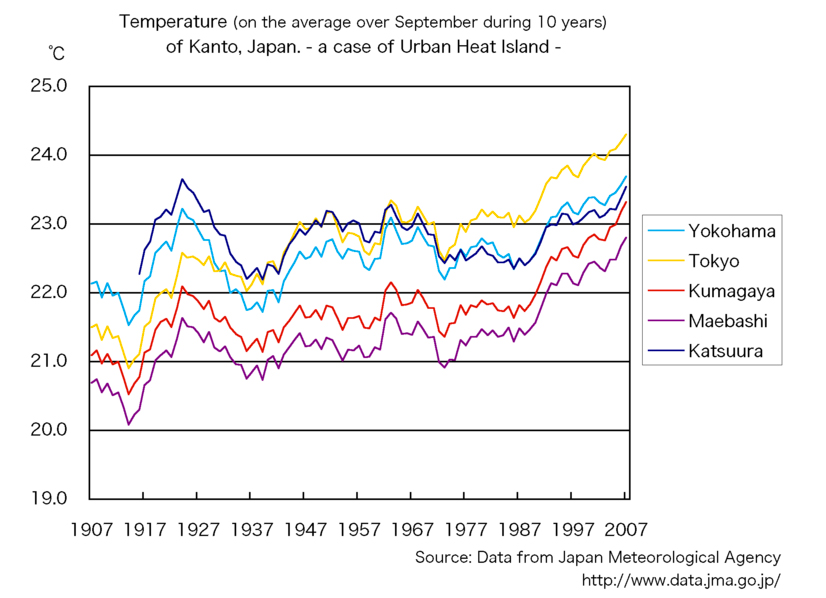

RAMANATHAN: Basically, the heat we put out, our car engines, factories, home heating - they all ultimately end up in the air. See, for example, Tokyo, they give a number of heat generated. That heat is two to three times larger than sunlight which heats Tokyo. So we can just imagine the amount of heat we put out. During wintertime, we have this so-called jet stream, fast winds blowing around the planet. And this wind is able to carry the heat we dump over cities like New York, Chicago, Tokyo, Beijing, Shanghai, etcetera, and blows this heat within few weeks around the planet. And that’s why what we think is a local phenomenon can become a regional and global phenomenon.

Clouds along a jet stream over Canada. (Photo: Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: The study is titled “Energy Consumption and Unexplained Winter Warming over Northern Asia and North America.” So why does the waste heat effect on climate only happen in the wintertime? Why isn’t it year-round?

RAMANATHAN: This waste heat is changing the temperature pattern by moving around the jet stream. The jet stream is dominant during wintertime. During the summer, for example, the jet stream loses its strength, and our regular temperature is more controlled by other processes, whereas in the wintertime, we are under the firm grip of the jet stream in terms of when it snows, when you have high-pressure and warm climate. So that sends the waste heat since it's changing the jet stream its effect is particularly strong and visible during wintertime.

CURWOOD: In the northeast especially where there’s been disturbances attributed to movement in the jet stream, this waste heat from cities is what is moving the jet stream, the study tells us.

RAMANATHAN: The last 10, 20 years, the jet stream seems to have a mind of its own, and it sort of fluctuates and moves back and forth, north and south rapidly. What this study is showing is that this waste heat might have moved the jet stream a little bit southwards. When the jet stream moves south is when you get huge cold spells in areas like Florida, Texas. But we have to be careful; there’s so many other natural phenomena that also contributes to this neurotic movement of the jet stream. Certainly, we are not helping it. We are adding one more monkey wrench there to move the jet stream.

CURWOOD: So what parts of the world are the most affected by the urban waste heat?

RAMANATHAN: The main countries or regions affected by this waste heat is North America, particularly the United States, northeastern United States, the entire Canadian region, and what we call Eurasian region. These regions have warmed up by as much as a degree and what's really exciting to climate scientists about this study is that these regions, they’ve been showing anomalous warming in the wintertime. And this study finds it's exactly during the wintertime when the waste heat warms up this entire continent.

CURWOOD: So part of the study then is good news; that climate disruption, global climate disruption, may not be occurring quite as fast as it might appear to people who live in these regional areas that are affected by this waste heat phenomenon.

RAMANATHAN: Well, I wouldn’t put it that way, because the warming you see in these regions during spring and summer and fall is still largely due to global warming. The good news is that our models are able to explain very closely how our planet has been warming. The bad news is, it confirms that our models may be right after all, and that global warming is as large as they think it is.

CURWOOD: And how does this affect our understanding of climate change in the models?

RAMANATHAN: This study really is sort of major impact on our thinking about local processes and global processes. We had always thought of this heat from cities as an urban heat island effect - just local heats up the cities and we knew that - that's been known for decades. What we didn't know is that this local phenomenon, it is a large signal in the background of global warming that's been going on for the last hundred years.

Tokyo, an example of an urban heat island. Normal temperatures of Tokyo go up more than those of the surrounding area. (Photo: Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: Veerabhadran Ramanathan is a Professor of Atmospheric and Climate Sciences at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. Thank you for taking the time.

RAMANATHAN: Thank you so much!

Related link:

More on Dr. Veerabhadran Ramanathan

[MUSIC: Meshell Ndegeocello “Turn Me On” from Pour une ame souveraine – A Dedication To Nina Simone (Naïve records 2013)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead - polluted air. It's not just dangerous for your lungs, it's a hazard for unborn babies too. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Monty Alexander: Running Away from Stir It Up: The Music Of Bob Marley (Telarc 2006)Happy Birthday Nesta Robert Marley 2/6/1945 – 5/11/1978]

Deadly Smog

Pollution in China (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. They used to sing about Foggy London town, but after World War II the British capital was more famous for its swirling smog, from coal burning power plants, coal fires in the hearth and diesel buses and trucks. The worst incident came in December 1952.

MAN1: “I don’t think the bleeding devil himself could have driven it all away. It was that thick. From that night it was vicious.”

WOMAN: “It was a warm fog. It was wrapped around you. It was all possessing.

MAN2: “It was smelly. It was dirty. It was black.”

MAN3: “It had an acrid, acidy feel about it.”

MAN4: “It seeped into the houses and indoors, everywhere was covered with grey film. It was quite uncanny."

CURWOOD: As many as 12,000 deaths were blamed on that killer smog and the British government was forced to act, passing the Clean Air Act in 1956. The United States, which had its own killer smog in Donora, Pennsylvania, in 1948, passed its own Clean Air Act in 1963. Since then, health problems due to poor air quality have fallen dramatically in both countries.

Without similar environmental protections, China is now facing a dirty air crisis, with toxic levels of air pollution throughout Beijing this past month. Jocelyn Ford is a journalist and a filmmaker based in Beijing, and she joins us via Skype. Welcome to Living on Earth!

FORD: Hello!

CURWOOD: So what's it like there, or particularly, what’s it like to take a breath there?

FORD: Well, on a bad air day, I actually try not to go outside because I don't want to be breathing in the equivalent of a pack of cigarettes a day. You can feel it in your lungs; your throat gets all clogged. It’s really not very pleasant. I tried to avoid even going to yoga so I wouldn’t have to breathe deeply!

CURWOOD: So how far can you see from your apartment?

FORD: I usually see...I have a wonderful view. I’m on the 16th floor. I can see all sorts of skyscrapers miles away. But this past month it's more or less like a Chinese ink painting with a little bit shade of grey the further you good, and then it becomes totally misty.

CURWOOD: What are people saying in the press in particular about the air? Any criticism of the government?

FORD: This first time that Chinese state media has really been paying attention to the dangers of bad air. Back in 2008 when China started to clean up its air for the Olympics, the air would be bad and people would say, “oh, its just fog,” because the media never talked about the smog. But now people are aware that the air is bad, the Chinese government has started making public meetings on just how bad the air is. People are becoming much more concerned about their health and about their children’s health. There’s a lot of concern for example that kids shouldn't be outside playing in the playground when the air is really putrid. And the public is really up in arms about this. They want the government to do a lot better job, and there are a number of foreigners who are now think about, “is it really worth staying in China with all of this?”

CURWOOD: And what’s your answer? Are you coming home?

FORD: The days when the air is bad and the internet doesn't work, I think, what am I doing here? [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: You know, we’d send you a bottle of oxygen, but probably the government wouldn’t allow it.

FORD: Actually, they’re already selling it here so I’m afraid we can probably get it cheaper.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Jocelyn Ford, filmmaker and journalist. Thank you so much.

FORD: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Well, Feb 9th sees the start of the Year of the Snake, and the Chinese people love nothing more at New Year’s than to let off fireworks which could worsen their smog. Scientists know that air pollution causes multiple medical problems for the people who breathe it in, but now a team of researchers from around the world has demonstrated a connection between dirty air and low birth weight. Mothers exposed to high levels of particulates, the scientists found, are more likely to give birth to underweight children, putting them at risk of developmental delays and illness.

One of the study's lead authors is Dr. Tracey Woodruff, the Director of the Center for Reproductive Health and the Environment at the University of California at San Francisco. She says that the size of the study’s sample shows that their conclusions should be taken seriously.

Dr. Tracey Woodruff (photo: UCSF)

WOODRUFF: We had over three million births in our study, so this makes it a very large study. In fact, we think it’s the largest study that’s been done to date to look at this question about maternal exposure to air pollution and its effects on birth weight.

CURWOOD: Now in which countries did you do your research?

WOODRUFF: We had participants in 14 centers on every continent except for Africa. We had several researchers in Europe, Brazil, Seoul, Korea, Australia, Vancouver, Canada and several locations in the United States including in California, New Jersey, Connecticut and Massachusetts. A lot of people have been conducting studies in their individual countries looking at air pollution and adverse pregnancy outcomes, both low birthweight and pre-term delivery. And they all worked out a little differently, they all found slightly different results so we gathered all the researchers together.

Through our discussions, we realized if we worked together we might have a stronger ability to look at this relationship between air and pollution pregnancy outcomes. We developed a protocol that everyone would do the same method in each of their studies. They acquired the same protocol, gathered the results, we aggregated them, and that was the result of the study. We can actually look across all the centers and pull all the information together to get a robust estimate about the relationship between maternal exposure to air pollution and low birth weight.

CURWOOD: And what did you find?

WOODRUFF: What we found was that there's an increased risk of low birth weight with increasing levels of particulate matter in air pollution.

CURWOOD: What was the increased risk?

Steel plant in Beijing, China (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

WOODRUFF: We saw an increased risk of 3 percent in low birth weight. It's not a very large increase for one person, but we’re talking about millions of pregnant women around the world were exposed to this. Because so many people are exposed you can have many people who were infected across large populations.

CURWOOD: Why does birth weight matter so much? What is it such an important statistic?

WOODRUFF: Birth weight is a very important indicator of essentially fetal health and doctors and public health practitioners are all concerned about the extent to which there’s low birth weight in the population. Babies who are born too small can be at increased risk of chronic conditions either during infancy or in childhood. Things like increased risk of infection, they might have developmental delays. And now we know that being born too small at birth can be an increased risk of adult disease. So things like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, what we call metabolic disorders, so really being born too small can set you off on a less healthy path in life.

CURWOOD: We're hearing a lot about air pollution in China right now, what would your study suggest might be going on in terms of the long-term effects of this rather poor air quality?

WOODRUFF: It reminds me of that earlier pollution episodes that actually led to the regulation of particular matter air pollutions, such as the London Fog of the 1950s, which also had very high levels of pollution. In terms of reproductive and developmental health concerns, the London Fog episode, well, they saw people actually dying and going to the emergency room in the hospital. They also saw an increase in infant mortality from that very high air pollution episode. And I would anticipate that in China that would be an issue for very young infants, and I would also anticipate that this would be affecting pregnant women, and increasing their risk of potentially adverse pregnancy outcomes.

CURWOOD: What do you hope comes out of this research?

WOODRUFF: Well, one of the reasons we were very interested in doing this research is to be able to provide people who are trying to make decisions a better estimate about the relationship between air pollution and pregnancy outcomes. The decision-makers are looking to figure out ‘if I have to do a regulation on air pollution, what are the potential benefits from regulating air pollution?’ And when they look in the scientific literature, it is often difficult to understand the meaning of what the different studies say because it’s not aggregated in a way that's useful for policymakers. So a second goal of the study was to essentially provide a better understanding about the relationship and then estimates that can be useful for people trying to make decisions about air pollution.

CURWOOD: Tracey Woodruff is the Director of the Program for Reproductive Health and the Environment at the University of California at San Francisco. Thank you so much, Professor Woodruff.

WOODRUFF: Thank you.

Related links:

- Maternal Fetal Medicine

- Maternal Exposure to Particulate Air Pollution and Term Birth Weight

- You Tube Video, Killer Fog

- Read the study

- UCSF press release

- Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment

- Toxic matters- tips for families for lowering chemical exposures

- a story about doctors and the challenges of talking about environmental exposures

[MUSIC: Donald Harrison “Bob Marley” from Nouveau Swing (GRP Records 1997)]

CURWOOD: In a moment - the salt harvest in India. Salt gives us the word salary - yet there's very little of that for salt workers who face brutally long hours in the hot sun. But first this Note on Emerging Science from Annie Sneed.

Science Note: Why We Get Bathtub Wrinkles

A wrinkled finger after a warm bath. Researchers found that wrinkles improve grip in wet conditions and they argue the puckered skin probably provided an evolutionary advantage to early humans. (Photo: Wikipedia)

SNEED: Hang out in the bathtub too long and your fingers and toes shrivel up like raisins. It’s not obvious why soaking in water results in wrinkles. But now, scientists think they have an evolutionary answer to this apparently useless trait. Back in the 1930s, researchers noticed the fingertips of people with nerve damage in their hands weren't wrinkled after being soaked. They concluded that the nervous system must cause this wrinkling, much as it does other involuntary responses such as breathing or sweating.

Yet for years researchers had no scientific explanation for why this would happen. Now a group of evolutionary biologists at Newcastle University in the UK think they have an explanation. They conducted a study where participants picked up wet and dry objects, such as marbles, either with dry hands, or after steeping their hands in water. The people with wet, wrinkly fingers picked up wet marbles more handily than those with dry fingers. But it made no difference whether hands were wet or dry when picking up dry marbles.

The researchers concluded that wrinkles improved grip in wet conditions. They compared the wrinkles on fingers and toes to treads on a car tire, and argued that they probably provided an evolutionary advantage to early humans. Wrinkled fingertips would have helped them forage and grip in wet vegetation or water. The same goes for toes - wrinkles would have given them better footing on wet ground. Even though we no longer go wading into marshes to gather our food, the adaptation remains. So next time you're soaking in the bathtub, keep one hand wrinkle-free, and give the marbles a try. For Living on Earth, I'm Annie Sneed.

Related link:

Newcastle University’s Tom Smulders explains the evolutionary reason for bathtub wrinkles on the Guardian

Salt Pans

The water has evaporated, leaving just the salt behind. (Photo: Henry Peck)

CURWOOD: For the last few months, cities and towns across India have been celebrating a slew of holidays, from Navratri, which honors the nine forms of the goddess Durga, to Diwali, the festival of lights. But for thousands of villagers in the western state of Gujarat, the festival season heralds a more somber kind of movement. In this season, thousands of Gujaratis migrate from their villages to salt harvesting sites, some along the coast and others deep in the desert, where they will remain for eight months to work in India’s multi-million dollar salt industry. From the Gujarati coast, reporter Meara Sharma has our story.

[FOOTSTEPS CRUNCHING ON SALT PANS, VOICES IN GUJARATI]

SHARMA: On the western coast of India in the state of Gujarat, tidewaters from the Arabian Sea spill into large, shallow rectangles cut into the earth. These are called salt pans. A checkerboard of hundreds of pans runs along the shore, and the crystals sparkle in the blazing sunlight. The landscape looks like an overexposed photograph.

[GANDHI SPEECH/PROTEST SOUNDS]

SHARMA: Salt has always been an important commodity in India, but it was controlled by the British during colonial rule.

MAN: CHANTING: "LONG LIVE..."

CROWD: GHANDAJI!

MAN: "LONG LIVE..."

CROWD: GHANDAJI!

SHARMA: 82 years ago, Mahatma Gandhi led thousands of people to the Gujarat coast in a march to protest the British monopoly over this native resource. The march energized Gandhi’s civil disobedience movement, and salt became a tangible symbol of Indian independence.

[ARJUN BHAI’S VOICE, SPEAKING GUJARATI]

SHARMA: But today, Arjun Bhai and his fellow laborers face a harsh reality in the Indian salt industry. Each year, Arjun and thousands of other villagers, leave their homes behind to work in the salt pans of Gujarat. It's incredibly barren here and there's no escape from the scorching sun.

Arjun says they will live on the pans for eight months harvesting crystals of the sea.

Sea water is funnelled into pans to evaporate for the salt harvest. (Photo: Henry Peck)

TRANSLATOR: They will plough this again. And after 25 days, they will get salt.

SHARMA: Each salt harvest takes 20 to 30 days. First, workers dig narrow canals to fill the shallow pans with tidewater that flows from the sea. Then, the sun goes to work, beating down on the pans and heating the seawater to the optimum temperature for crystallization - 75 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit. The laborers use crude shovels to gather the salt, and then carry the harvest in buckets on their heads to communal heaps where it glistens in the sunlight.

TRANSLATOR: It is shining. Yes, you can see it sparkling. This is salt – that shining thing.

SHARMA: Each pan yields about 200 tons of salt per year. It's an industry worth 200 million dollars and industrialists and landowners reap enormous profits. But the laborers in the salt pans endure unforgiving conditions and a punitive labor contract to eke out a living.

[ARJUN BHAI’S VOICE IN GUJARATI]

TRANSLATOR: We receive an advance of 15,000 rupees at the beginning of the monsoon season. The monsoon lasts for 4 months, and there is no work during that time. After the monsoon we must come and work in the salt pans for the next 8 months.

The fruit of the harvest, sparkling salt crystals. (Photo: Henry Peck)

SHARMA: 15,000 rupees is about 300 hundred dollars. That might seem like a large sum for a laborer in India, but it’s all these workers get, all year.

TRANSLATOR: But the hidden condition is that they have to work here only. Right, yes of course.

SHARMA: Two people, often a husband and wife team, work in each pan, wading barefoot in extremely salty water.

TRANSLATOR: Suppose if you get wound here, some injury, and you put your leg or hand in the water, it is very paining.

[MACHINE PUMPING]

A pump brings briney water up from deep under the desert. (Photo: Henry Peck)

SHARMA: The pans on the coast aren’t the only source of salt in Gujarat. Further inland, a white desert called the Rann of Kutch is home to a different kind of salt production. This desert was once submerged in the Arabian Sea, and the groundwater is still full of salt. Here, bore wells are dug hundreds of feet deep, and salty water is pumped into pans above ground.

[AMBIENT SOUND OF WELL AND REPETITIVE WATER PUMP SOUND]

SHARMA: The sound of the bore well pumping is constant and grating. But this process is necessary for collecting what some argue is a superior kind of salt.

TRANSLATOR: Yes, quality is different.

SHARMA: Which is better?

TRANSLATOR: This is best quality. Because this is from underground water. Marine salt is like this - grainy.

SHARMA: Yes, and this is crystals.

TRANSLATOR: Crystals.

SHARMA: On the coast, hundreds of workers harvest side by side, but the desert is a lonely place. The six members of the Raja family tend to four pans between them. Their house is a rickety structure made of tree branches, grass and plastic tarp. Around them, there’s no fresh water, no shade, and no visible roads – just cracked, dry earth.

SHARMA: Do they ever feel afraid, being so far away from water, or other people?

TRANSLATOR: No, absolutely not.

MAN: They are very brave.

SHARMA: Yet laborers in the desert are subject to the same kind of inequitable work agreement as those in the coastal pans. They receive a single payment at the beginning of the monsoon, and must commit to work for the rest of the year. But for all these workers, there are advantages to the system. Back on the coast, Arjun tells us that receiving a lump sum allows family members to pool their earnings and pay for important events - like weddings.

[ARJUN BHAI SPEAKS IN GUJARATI]

TRANSLATOR: I had to pay a dowry for my daughters when they got married. This is 50,000 to 60,000 rupees. With our family income from working here, we have that much money at one time and we were able to pay these dowries.

SHARMA: In this region of Gujarat, the caste system still tends to define social roles and occupations. Arjun Bhai and the Raja family are part of the Koli community, who have traditionally worked in the salt industry. And for many members of this community, including Arjun Bhai, salt work is an inherited profession.

SHARMA: How long have you been working here?

[ARJUN BHAI RESPONDS IN GUJARATI]

SHARMA: His whole life?

TRANSLATOR: Whole life.

SHARMA: And your family as well?

[ARJUN BHAI RESPONDS IN GUJARATI]

TRANSLATOR: His forefather was working same, his father’s work is same, since long.

[WATER FLOWING FROM WELL]

SHARMA: Despite the grueling way of life on the salt worksites, laborers are proud to be part of an industry that Gandhi made the symbol of their country’s independence movement.

There are hundreds of salt pans along the coast. (Photo: Henry Peck)

[ARJUN BHAI SPEAKS IN GUJARATI]

TRANSLATOR: He made a good garden for us, Mahatma Gandhi. India is a garden. It was spoiled by another country. But Gandhi renovated it.

SHARMA: And for the laborers in the salt pans, even the desert is a fertile part of this garden. They’ll be there, tilling and harvesting salt, until next summer, when the monsoon rains return.

For Living on Earth, I’m Meara Sharma in Gujarat.

[MUSIC: Bombay Dub Orch “Monsoon Malabar” from 3 Cities (Six Degrees Records 2008)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...navigating the journey from child of nature to responsible adult in the technological world - it takes research and compromise. That's just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway, for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Padio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Donald Byrd: “Hush” from Royal Flush (Blue Note Records 2006 Reissue) R.I.P. Donald Byrd (12/9/1932 – 2/4/2013)]

All Natural

All Natural (photo: Rodale Books)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Our ancestors depended much more directly than we do on the natural world for food and shelter, yet cultures often distrusted and feared nature. After all, dangerous creatures lurked in forests and savannahs, along with poisonous plants. But these days, some people see our increasingly technological age as the source of ailments - so they opt for free range and organic.

Nathanael Johnson’s parents were early adopters of the natural lifestyle, outlawing sugar and TV, and making clothes optional at home. So, about to become a father himself, Nathanael Johnson decided to investigate the science behind lifestyle choices, from childbirth to vaccines. His debut book All Natural, is an effort to determine if his parents’ approach to living was healthier or not.

JOHNSON: I grew up in a family that really believed that it was healthier to embrace nature, rather than protecting ourselves with technology against nature. When I was a baby I didn't wear diapers at all. They just kind of followed me around and wiped up and, you know, it was a lifestyle of a lot of kale and a lot of brown rice and backpacking every summer. They really did have this feeling that technology was corrupting. They made sure that there weren’t televisions in the house and when they eventually did break down and get a computer, they made sure that we played outside for three hours for every half-hour that we were on the computer. That was the rule.

CURWOOD: To what extent did you buy into this lifestyle that your parents set out for you?

JOHNSON: When I was young, I really bought into it, this idea that what's natural is healthy is really tenderly wedded into my sense of childhood innocence, but at a certain point, probably around the age of five, I started wondering if my parents lifestyle was actually holding me back. Because that was the age when I started coming into contact with other families and seeing how they lived.

CURWOOD: Tell me about the incident at age five or so where you first had to question your parent’s lifestyle?

JOHNSON: [LAUGHS] So my parents took me my little brother to a potluck out at this little lake, and it's a warm summer evening, there’s mosquitoes buzzing around, families are spooning up casserole and chicken salad. And in the lake, there’s a floating platform, and all these other kids are swimming out to the platform and pushing each other off, and it just looked heavenly to me. So I pulled at my parent’s pant leg and said, “I want to go swimming.” And I haven't brought a swimming suit, but this was really not a problem because in our family, nudity was the norm around the household. So my parents said, “Just go skinny-dipping. Go on in.”

So me and my little brother, we swam out to the platform, we pulled ourselves up, we’re ready to take all comers and instead everything just stops. And this little girl on the platform shouts, “They’re naked! They’re naked!” And they all dive off the opposite side and they swim for shore. It was like one of those monsters from the 1950s horror movies wanders into the beach party and destroys everything. And that was the first time I came back and had this strange sense of shame that I hadn't really ever felt before. And it made me wonder if there was something wrong with the way we were living.

CURWOOD: How much of a rebel did you become against your family’s all natural lifestyle?

JOHNSON: I wouldn’t say that I was a rebel. I wasn't acting out, but I was always the annoying one. I was always the one that was questioning, saying, “Is that really true? Can you prove to me that if I have this ice cream cone it's really going to be bad for me because I think that maybe, just maybe, it's going to make me stronger.” I was always the skeptic in the family who wanted hard evidence. It wasn't that I ran away from home and started smoking cigarettes and watching television all the time and eating sugar by the handful, but I did start thinking.

CURWOOD: Let’s fast forward to the arrival of your own child. Now you have to start making choices for this person that you’ve brought into the world. What do you do?

JOHNSON: Exactly. I obsessively bury myself in research.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

JOHNSON: My wife comes from a very different background. My parents are West Coast hippies, her parents are East Coast Republicans. I was born at home and she was born by scheduled Cesarean section. And we both kind of rebelled from our parents - all children seem to - and we met somewhere in the middle. But we really had to negotiate all these different things. She wants to protect Josephine from the sun, I tend to want to protect Josephine from sunscreen. Becoming a parent forces you to move from abstraction down to the brass tacks. It forces you to put your ideas into practice, especially your ideas about nature because normally the way we think about nature in this country is pretty abstract. It's out there, it’s in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge where we revere it, but when it comes into your own life and you actually have to deal with it, make a choice whether to control it or adapt to it, it becomes very different. And an infant really is a representative of nature. And so I started having to, from the beginning, make decisions. I was born at home. Was I going to do that with my own family, or was I going to try and influence my wife who has a lot more to say about this decision? And then all the way up, making choices about what my daughter would eat and all these things. I really felt like I had to pin down what I really believed and how much of my parents’ lifestyle I was going to copy. And that was in a large part the genesis of this book.

CURWOOD: Your book begins with a chapter on birth, and you did some deep research here. You spent time with midwives in rural Appalachia. Tell me what you learned at the farm in Tennessee?

JOHNSON: Well, I went to the farm in Tennessee, which is one of the original communes. And they started the midwifery center. Ina May Gaskin is the head midwife that was one of the original founders of the farm and they really have a remarkable program there, much lower C-section rates than we have in the rest of the country and much lower rates of complications. So I wanted to go see what they were doing right there. I was really hoping to be able to see a birth. I asked one of midwives, “Would it be alright if I went in and just talked to one of the women who’s here?” And she said, “We just don't do that. We don’t want to bring your male energy into this process; this is a very private spiritual process.” And I was surprised because I expected that sort of thing, that reflexive privacy from big hospitals, but I hadn't expected that from this homespun midwifery clinic.

CURWOOD: ...until, and you changed your perspective completely on this...

JOHNSON: I learned from Ina May and from going back and looking at anthropology and research on human evolution that the process of birth really depends a lot on the way that people feel and the company that they keep. The hormones that lead to a successful labor have a lot to do with the way that people feel. This idea that my energy, or my presence as a stranger, my disruption, could actually slow things down actually makes a lot of sense.

CURWOOD: I have to say one of the most amazing things that I learned from this book was that despite technological progress, the mortality rate for women in childbirth has actually been going up in recent decades in places like California. Can you explain that for us?

JOHNSON: Well, when you look at the maternal mortality rate in California it does seem to be rising. There’s pretty good evidence that it’s going up and probably in the rest of the country as well. And there are certain complications that are directly related to Cesarean section - there is no scientific disagreement about this. This really terrible complication where the placenta grows through the scar of an old C-section has increased to just epidemic levels. It’s still incredibly rare but the increase is really remarkable. And there's even better evidence showing that severe maternal injuries - women who have acute kidney failure during labor, it’s going up significantly. The number of women who have heart attacks during birth has increased 80 percent in the last decade. And so, while it's still much safer to give birth than it was back at the turn of the century, we are seeing some erosion in our progress. And whether it's from these social factors like obesity or whether it's from medicalization - and it’s probably from both - it does say something about how pushing forward with technological process in our hospitals. If you push too far, sometimes the results turn bad.

CURWOOD: Final note here on birth - what happened with your own daughter?

JOHNSON: I think that I really learned from the midwives in Tennessee that it's important beyond all else for the woman to be comfortable and where Beth was most comfortable - where my wife was most comfortable - was in the hospital. So we ended up at a hospital that has a midwife-run labor and delivery unit with very up-to-date standards and we felt very comfortable there.

CURWOOD: And what was the outcome?

JOHNSON: We had a beautiful little baby girl who’s just become the light of our lives.

CURWOOD: And your wife’s health?

JOHNSON: My wife is incredibly healthy; she bounced right back and two days later we actually walked home carrying the baby.

CURWOOD: Nathanael Johnson, tell me what you learned about vaccines? And what did you think going into your research and what did you learn?

JOHNSON: I wasn't one of these people who was crazy about vaccines who, you know, there are a lot of people who are pretty extreme and vehement that vaccines are causing all types of problems. But at the same time, I did worry about them. It just seemed so alien to inject yourself with something made far away by a corporation that you don’t know anything about. And I worried there was some blind spot that the medical orthodoxy was overlooking. So I started doing the research on this, and to make a long story short, I was really stunned to find that every theory that I tracked down, every worry about overloading the immune system and autism and all of these things lead back to scientific dead ends. And there was so much science there that just really made me feel comfortable by the end. And now when Josephine goes in for her shots I really don't have a second thought.

CURWOOD: I want to ask you now in the end where do you come down on all of this? Are you a proponent of the technological or the all natural perspective?

JOHNSON: Well it would make my book a lot easier to sell if I had an easy answer to that! If it were simply ‘trust nature and you’ll be healthy and live forever’ or ‘nature’s bad - just do anything you can to protect yourself against it’ - that kind of polemic would be a lot easier to explain to people. But I think in the end these polarized visions we have over nature have less to do with nature and more to do with the way that we look at the world. The way forward is to hold both perspectives at the same time and the people that I found in the middle of these debates who were really doing interesting work and moving the ball forward were the people who were able to look at the big ecological picture, and then bring in that detailed scientific deductive practice to get the details right.

CURWOOD: In your conclusion you do seem to come down on one side here. Could you read from that one section for me please?

JOHNSON: ‘It's not so terrible when the all-natural right-brained reflex guides us toward phony alternative medical practitioners or overpriced groceries. Sure, people, or more often, pocketbooks, are harmed by a credulous assumption of natural goodness, but the number of people seriously hurt by these things is relatively low. I’m more concerned with the problems that arise when the technological left-brain gaze fixes tenaciously on the perceived problem, while ignoring the larger systematic problems that might exist. The gravest dangers we face, in my opinion, stem from our tendency to grasp desperately at control where none is available. They stem from our tendency to focus so intently on small technical solutions that we lose sight of the whole and holy.’

CURWOOD: Nathanael Johnson's new book is called All Natural: a skeptic’s quest to discover if the natural approach to diet, childbirth, healing and the environment really keeps us healthier and happier. Thank you so much, Nathanael.

JOHNSON: Thank you so much, I really appreciate it.

Related link:

Nathaniel Johnson

[MUSIC: Donald Byrd “Cristo Redentor” from A New Perspective (Blue Note Records 1999 Rudy Van Gelder Edition Reissue)]

Sounds of Winter

(Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: New England winters are usually cold and gray. So it’s easy to have pity on those of us who live and work here in the frozen north, especially this year with near record low temperatures and blizzards clobbering parts of the region. But winter can have a silver lining for those who take the time to listen. Living on Earth commentator and New Hampshire resident Sy Montgomery explains.

[CHICKADEE CHIRPING AND WINGS FLAPPING]

MONTGOMERY: At no other time of the year are sounds so sharp. The scolding winter call of the chickadee. Wind howling through oaks, or whispering through pines. The clarion call of wind chimes, piercing as the cold itself.

[XYLOPHONE-LIKE SCALE OF WIND CHIMES SOUNDING]

MONTGOMERY: Hearing may be the richest sense. Helen Keller wrote she felt its absence a handicap far worse than blindness. As if to make up for winter’s void – of colors muted, touch numbed, and scents sealed – winter’s sounds are the most vibrant.

[WHIZZ OF RUBBER SNOW TUBE SLOWING TO A STOP, CHILDREN LAUGHING]

MONTGOMERY: Sound travels further over frozen ground. Frozen surfaces are rock-hard, so they don't absorb sound – they reflect it. And when the atmosphere above is warmer than the ground, sound bounces back toward the ground. Winter’s freeze is like having a sound reflector in the sky.

[SCRAPING, RHYTHMIC GLIDE OF SKATES ON ICE]

MONTGOMERY: Winter’s bareness amplifies and clarifies its voices. Spring and summer are crowded with ambient noise: the sounds of birds and insects, the rustle of animals in the woods, the whisper of grasses and leaves – not to mention the hubbub of so many people and their machines.

[CREAK OF SWAYING TREE]

(Bigstockphoto.com)

MONTGOMERY: In summer, leaves absorb sound, especially the higher frequencies. But now, the trees are bare, summertime’s murmurs are hushed, and snow is covered with hard ice crust. Sound slices through the air—stark, clear, pure.

[CRUNCH OF FOOTSTEPS IN SNOW]

MONTGOMERY: So this is the best time of year, I think, to go somewhere secluded – just to listen. Listen for the voice of the wind. The ancients said that Boreas, the north wind, loved a nymph who was changed into a pine tree. Boreas still rages and howls through oaks and maples and beech, but his voice is quite different when he speaks to his love.

Listen to the voices of the trees. They creak like rusty hinges as they sway in the wind. Sometimes trees will even pop loudly – it can sound like fireworks – their wood expanding and contracting during sudden changes in temperature.

Listen to the voice of the ice. On a lake, sometimes, you can hear the ice squeak, or crack, or even boom. Even safe, solid ice will make a cracking sound as it expands. Scary to an ice skater – but if you’re walking in the woods, the booming of a lake is like music.

And remember, in winter, that one of the greatest rewards of listening can be silence. Orchestras know this. At the end of a performance of Mozart’s Fantasy in C Minor, a thousand ears strain for the last note.

[PIANO MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

MONTGOMERY: Silences are different in winter, too. This is not the soft, glowing stillness of pre-spring, or the absorbing quiet of swimming underwater. No, winter’s silence, like its sounds, is piercing, clear and cleansing, like a shooting star, well worth seeking and savoring.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery is the author of more than a dozen books including The Good, Good Pig, The Search for the Golden Moon Bear, and The Wild Out of Your Window: Exploring Nature Near At Hand.

Related links:

- Sy Montgomery

- More about Sy Montgomery

[MUSIC CONTINUES: Andreas Haefliger, Mozart “Fantasia for Piano in C minor K475” from Piano Sonatas (Sony Classical - 1991)]

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Annie Sneed, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director.Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. Or at Twitter at LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at justeatorganic. com. Support also comes from you our listeners. The Go Forward Fund and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at PaxWorld.com. Pax World, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth