February 15, 2013

Air Date: February 15, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Obama Doubles Down on Climate Action

View the page for this story

In the State of the Union address, President Obama called climate change a clear and present danger, promising executive action if Congress won't pass legislation. Host Steve Curwood discusses the second term environmental agenda with Ann Carlson of the Emmett Center on Climate Change at the UCLA School of Law, and Kevin Knobloch of the Union of Concerned Scientists. (13:30)

Starving Polar Bears

View the page for this story

Polar Bears have long been the poster species for the problem of climate change. But a new paper in Conservation Letters argues that supplemental feeding may be necessary to prevent polar bear populations from going extinct. Polar bear expert Andrew Derocher from the University of Alberta joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how we can save the largest bear on the planet. (08:15)

The Thrills and Spills of Backyard Hockey

/ Bob CartyView the page for this story

In Canada, backyard skating is a favorite winter pastime. Canadian journalist Bob Carty brings us an audio postcard from his neighborhood rink in Ontario, and if you don't have one, he tells you how to make one. (04:25)

Rinkwatchers and Citizen Climate Science

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Backyard skating rinks are as common in Canada as basketball hoops in the United States. But now, global warming is threatening this Canadian tradition. In response, a group of scientists has started a website called Rinkwatch.org. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald reports on this effort to turn backyard skaters into citizen scientists and make climate change relevant to every day Canadians. (03:30)

Women & Population

View the page for this story

The inequitable treatment of women can exacerbate a whole host of global problems, from violence to poverty to overpopulation. Eco-activist Laura Turner Seydel discusses how justice for women also helps the environment with host Steve Curwood. (04:00)

Louis Agassiz

View the page for this story

The legendary naturalist Louis Agassiz was much loved by Americans in his time, but today, Agassiz has a mixed legacy. Host Steve Curwood talks with author and Indiana University English professor Christoph Irmscher about his new biography, “Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science.” (12:20)

Earth Ear: Daybreak at Iguaçu

View the page for this story

Steve Curwood and Dan Grossman recorded the dawn chorus of birds at Iguaçu Falls on the border of Argentina and Brazil. (01:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Kevin Knobloch, Ann Carlson, Andrew Derocher, Laura Turner Seydel, Christoph Irmscher

REPORTERS: Bob Carty, Emmett FitzGerald

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. President Obama is talking big about climate dangers, and has already hired former Senate Relations Committee Chair John Kerry to spark international efforts.

CARLSON: The Secretary of State is going to play a key role in upcoming negotiations to try to extend the Kyoto Protocol and to get the international community really committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. And I think the signal it sends to have somebody who is such a strong senator on climate now leading the state department is really really important, and he's got an opportunity here to signal to the rest of the world that the United States is serious about reducing its own emissions and getting the global community to follow suit.

CURWOOD: The world may want to follow suit - but the US Congress may have other ideas. Also the thrills and spills of backyard skating, and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[THEME]

[MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm.

Obama Doubles Down on Climate Action

President Barack Obama delivers the State of the Union address at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., Feb. 12, 2013. (Official White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. 2013 could launch the era of climate action for the Obama administration, if we're to take the rhetoric seriously. In January, as the President stood on the steps of the Capitol to be sworn in for a second term, he put the climate challenge front and center. And most recently in his State of the Union address the President laid out more details - and connected the dangers of climate instability to recent extreme weather.

OBAMA: It’s true that no single event makes a trend. But the fact is, the 12 hottest years on record have all come in the last 15. Heat waves, droughts, wildfires, floods - all are now more frequent and more intense. We can choose to believe that Superstorm Sandy, and the most severe drought in decades, and the worst wildfires some states have ever seen were all just a freak coincidence. Or we can choose to believe in the overwhelming judgment of science - and act before it’s too late. [APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: We turned to two seasoned observers of science and climate policy for some perspective. Environmental Law professor Ann Carlson is a co-director at the Emmett Center on Climate Change at UCLA, and first here's Kevin Knobloch; he’s President of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Left to right: Steve Curwood, Kevin Knobloch, and Ann Carlson (Photo: Helen Palmer)

KNOBLOCH: What he's doing in talking about the impacts is connecting to the millions of Americans who now experience climate impacts and the costly destruction of climate impacts. You know if you’re a gardener or a hiker, carpenter who works outdoors you already are observing and connecting the dots between climate influenced weather events and climate change. And so the President is simply tapping into that and reminding many other Americans that this thing is real.

CURWOOD: So the president says this is happening, he says the people see that this is happening...realistically is any chance of Congress getting together and saying that this is happening and that action should happen now based on the science?

KNOBLOCH: I thought it was a brilliant stroke that the president called on Congress and cited Senator John McCain and Senator Joe Lieberman’s earlier work in trying to move a comprehensive climate bill through the Congress. Because it is the Congress’s responsibility to respond to an urgent problem like this. He then said, ‘if Congress won’t act, I will.’

CURWOOD: Professor Carlson, you're a lawyer who looks closely at environmental law. So tell us, what can the President do on his own if the Congress doesn't act?

CARLSON: The most expansive power he has is under the Clean Air Act, and he’s used that in two respects. One, to ratchet up fuel efficiency standards to really quite dramatic levels going forward, and the second thing he's doing is he's issuing regulations that are actually required under a court decision called Massachusetts vs. EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from new and existing coal-fired power plants and other utilities. He’s also got power to, for example, use his procurement power to have his agencies purchasing green vehicles, to get the Defense Department, as it already has, focused on the development of renewable power. He’s done a fair amount on federal lands in getting the siting of renewable facilities to produce renewable energy through more quickly. So he’s not only already done a lot, but continues to have a fair amount of power.

CURWOOD: I noted that in his speech he certainly suggested he would continue to push renewable energy to keep up with China among other things. Is there enough energy in the renewable energy program the President has laid out so far, Kevin Knobloch?

KNOBLOCH: Yes; here's the interesting thing about what's happening with renewable energy in this country. Not only is it growing rapidly, but it’s driving manufacturing growth - American manufacturing growth. So in 2005 the percentage of wind towers, turbines, gearboxes installed in this country - made in this country - was 35 percent. Today it’s 70 percent. So through the deep recession this is one of the few growing areas of American manufacturing - and that has everything to do with state policies and federal policies and investments to drive renewable energy.

CARLSON: So here's a place where Congress has cooperated with the president - although on a short-term basis - is in passing and extending the production tax credit which really is one of the reasons why renewable energy has continued to grow throughout the recession. One of the things that the President is trying to do in his State of Union and speaking directly Congress is to suggest that there may be areas where Congress can agree with the president - on ways to stimulate new energy innovation, potentially to stimulate research and development, without actually tackling the larger question of an overall national climate policy.

CURWOOD: Now elsewhere in this speech he says he plans to cut red tape and speed up oil and gas permits. So do you see that as an olive branch maybe to the fossil fuel industry or heartland Democrats?

CARLSON: I think Obama's energy policy all along has been to focus heavily on domestic energy sources, not always renewable ones, and I think some of that is political; I think some of it is economic reality. There is a huge boom in the drilling of natural gas and I think it's something that no president can ignore. Natural gas prices have fallen really dramatically, and trying to encourage that has a couple of consequences - one of which is positive in the short run for climate change - and that is that natural gas is displacing coal which is a much more carbon intensive fuel than natural gas. And so in the short term that's really led to a reduction in emissions and that’s not a bad thing to encourage. In the long run, if we really do accomplish the kinds of climate goals that scientists believe are necessary to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we’re going to have to move away from natural gas as well - or figure out how to do something with emissions that natural gas and coal generate by sequestering them into the ground or something that doesn't release them into the atmosphere.

KNOBLOCH: The low price of natural gas is also creating some competition and stress for cleaner renewable energy and we have to be mindful about that.

CURWOOD: The President’s plan, though, to speed up oil and gas permits; does it raise any red flags, Kevin Knobloch? Does it say anything about the approval of the Keystone XL pipeline, for example?

Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood in conversation with Kevin Knobloch and Ann Carlson (Photo: Helen Palmer)

KNOBLOCH: The Keystone XL pipeline, which would transport dirty oil from the so-called tar sands sites up in Canada through the vertical length of this country down to our export ports in Texas, really has become an emblem among people worried about climate change, in great part because we don't have a coverage policy this country, a declining cap on carbon and other heat trapping emissions within which to consider these projects. So what’s happening now, whether it’s this proposed pipeline or efforts to open up coal export ports in the state of Washington is that the people across the country who worry about climate change - the pace of change and the role of fossil fuels driving and accelerating it, stepping up and opposing these projects. Our sense is that we need to get a comprehensive policy in place; it rapidly drives down greenhouse gas emissions and gives us a fighting chance to hold off catastrophic changes. Until then, it is likely to be a pitched battle over every major pipeline or coal export and becomes a symbol of turning a blind eye to what the burning of fossil fuels is doing to the ability of this planet to sustain life.

CURWOOD: Professor?

CARLSON: So I think the Keystone XL question raises a really important question that is mostly avoided in the State of Union, but I think we’re really going to need to focus on as well, and that is that the United States can't go at it alone on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. And as we do things like focus on domestic natural gas, the rest of the world is still heavily dependent on coal, and in fact, things like ports that Kevin mentioned to export coal simply mean that we could shift a lot of the emissions away from the domestic economy and to the global economy - and one of the problems of that is overall greenhouse gas missions aren’t reduced. So one of the really interesting and important questions will be the degree to which Secretary of State Kerry, for example, makes the goal of reducing international global admissions central to his mission diplomatically.

CURWOOD: So the president proposed to use federal oil and gas revenues to fund what he calls an energy security trust, and he said that this would drive research and shift our cars and trucks off of oil for good. Let’s hear a bit of that tape.

OBAMA: Tonight I propose we use some of our and gas revenues to fund an energy security trust that will drive new research and technology to shift our cars and trucks off oil for good. If a nonpartisan coalition of CEOs and retired generals and admirals can get behind this idea, then so can we. Let’s take their advise and free their families and businesses from the painful spikes in gas prices we put up with for far too long.

KNOBLOCH: It's a powerful vision. It’s really the kind of presidential leadership that you look to a president for, to set an ambitious long-term vision that helps solve a range of problems. The trust fund is an intriguing idea; it would create revenues for research on hydrogen fuel cells and battery electric vehicles along with low-carbon biofuels and so on. It’s a little bit of a mixed signal to draw the revenues from oil and gas drilling on public lands. But there may actually be an exquisite partnership there.

CARLSON: I think one of the things that might be a place where you can get bipartisan agreement is to fund research into technology and innovation. That seems to be less controversial than, for example, regulating carbon emissions or putting a price on carbon by imposing either a tax or a cap and trade scheme. So I think this is a place where maybe he can get some bipartisan agreement. I don’t know whether he’ll get it out of those particular revenues. I would also add that I think the push to move our automobile fleet away from conventional gasoline and to electricity and to other fuels that do not emit carbon is an absolutely necessary move if we are to reduce our carbon emissions in the way that scientists think we need to in the course of the next 30 or 40 years. It's a long-term strategy, but it’s a strategy we got to begin now.

CURWOOD: The President, to do all this, needs a team. Most of his green team has left - the Secretary of Energy is moving on, the Secretary of the Interior, the administrator of the EPA, the leader of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - all these folks have left the administration. Why do you think such turnover in the green team for the President if he's making such a new commitment here?

CARLSON: The turnover to me seems to be just the natural result of having served for four years, a very intense four years, and not in any way a statement about whether the people who are leaving have a commitment to the President's agenda going forward. And I trust that he will find equally impressive replacements for all those very talented and extremely qualified public servants. So it doesn't concern me there’s turnover, it just seems like a natural turnover at the end of a first term.

CURWOOD: Quick last comment on new administration member John Kerry, Secretary of State...the XL pipeline decision first goes through the Department of State. As a senator, John Kerry sponsored really strong legislation - it didn’t pass - on climate. How do you think having Mr. Kerry at State is going to effect something like the pipeline decision, Kevin Knobloch?

KNOBLOCH: There's been no stronger leader on climate action in the Congress than Senator Kerry. I think we should have every reason to expect him to bring that leadership into his role as Secretary of State. The most important thing is that the Environmental Impact Assessment that the State Department is conducting on the Keystone Pipeline take into account climate change and climate impacts. Any serious environmental assessment of climate impacts of this pipeline will show that it would have very significant harm.

CARLSON: The only thing I would add is that the Secretary of State is going to play a key role in upcoming negotiations to try to extend the Kyoto protocol and to get the international community really committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. And I think the signal it sends is to have somebody who is such a strong senator on climate now leading the State Department is really, really important and he's got an opportunity here to signal to the rest of the world that the United States is serious about reducing its own admissions and to getting the global community to follow suit.

CURWOOD: Kevin Knobloch is President of the Union of Concern Scientists, Ann Carlson is a Professor of Environmental Law at UCLA. Thank you both.

CARLSON: Thank you so much.

KNOBLOCH: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Video of State of the Union

- Union of Concerned Scientists

- Ann Carlson’s page at UCLA Law School

- Click Here to Hear a Longer Interview

[MUSIC: Manu Katche “Running After years” from Manu Katche (ECM Records 2012)]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line at anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-99-88. Or write to PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. Our email address is comments@loe.org. That’s comments@loe.org. You can hear our program anytime on our website, or get a download of the audio to listen when you want at LOE.org. Just ahead...news from up north where ice is both a matter of survival and a recipe for fun. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Grover Washington Jr. “Love Makes It Better” from A Secret Place (Verve Music Group 1976)]

Starving Polar Bears

Two polar bears (photo: Andrew Derocher)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The polar bear has become an icon of the melting arctic, the poster species that illustrates the rapid advance of climate change. And now a paper published in the journal Conservation Letters argues that drastic measures may be needed to save Ursus maritimus from extinction, including supplemental feeding. Andrew Derocher is a Professor of Biology at the University of Alberta, a long-time polar bear researcher and one of the paper’s primary authors.

DEROCHER: We’ve got 19 different populations of polar bears in the circumpolar Arctic and each one of them has a slightly different story to tell. Some of the populations are definitely undergoing stress with climate changes where the sea ice melts away, particularly those bears that live in the Hudson Bay system in Canada, but also the bears off of Alaska in the Southern Beaufort Sea population are showing clear signs of stress. Other populations are quite secure and will continue to be so for quite some number of years into the future.

Biologist Andrew Derocher with two tranquilized polar bears (photo: Andrew Derocher)

CURWOOD: Now, talk to me a bit about the basic biology of a polar bear...just why does it need this Arctic ice?

DEROCHER: Well, basically it’s the platform that they live on and they travel across it, so they undertake long-distance migrations covering vast distances in a single year. They sort of move between different places to hunt their primary prey which are Ring seals and Bearded seals. They're only found where the sea ice exists and we only have polar bears where there are these two species of seals.

So basically the bears are adapted to dealing with the sea ice environment; you really have to think of them more as a marine mammal than a terrestrial mammal. Virtually all of their nutrition comes from the marine environment.

CURWOOD: Tell me how climate change affects polar bears so intensely?

DEROCHER: It’s a simple story really. It’s just a habitat loss issue so, as we warm up the climate, the Arctic is showing very rapid changes in sea ice, and basically, polar bears are just being pushed away from places where they have lived in recent tens of thousands of years. We expect them to continue to lose their habitat in the south; they’ll persist for some longer period of time at very high latitudes, but of course it’ll be a much diminished number of bears than we have today. The very best studies were done by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and their estimates were that we'll lose two-thirds of the global population of polar bears by midcentury. Some indications are that that might have been overly optimistic; we may lose some of these populations much, much sooner than.

CURWOOD: By the way, people still shoot polar bears in many places, yes?

A polar bear walking on the ice (photo: Andrew Deroche

DEROCHER: Yes that's still pretty common in much of the Arctic. We still have a harvest throughout North America and Greenland; Norway doesn't hunt bears, and Russia has a very limited hunt. And that is a concern, but it's not really what's pushing the conservation issues for the management of polar bears or their conservation. Some of these populations have a sustainable harvest and there’s no reasons why local people can’t continue to live in a subsistence manner and harvest polar bears. The problem is some of our populations won’t have a sustainable harvest, or don’t have one right now. And that’s where there’s a lot of challenges coming for local people that have relied on these resources for thousands of years.

CURWOOD: Your paper outline some potential strategies for saving the polar bear...please discuss them with me now.

Polar bear at sunset (photo: Andrew Derocher)

DEROCHER: We basically raise a bunch of options, which is from sort of a minimalistic sense -you do nothing, you just watch them disappear. The other option is that you perhaps start to rehabilitate some of these starving bears, try to keep them alive and put them back into the population. So feed them up, then let them go.

CURWOOD: Feeding bears? How necessary do you think that might be?

DEROCHER: I think we're going to be doing it; I think there's such intense interest in polar bears that I think we will be feeding them. There's no doubt in my mind that some of these populations are going to probably be sustained with supplemental feeding. To put it into perspective, we feed other species to keep them alive as well. So if you go into a European context, their equivalent of our Grizzly bear, the Brown bear, there are populations that are fed all the time to keep a viable population in an area - and to keep them away from humans as well. We also do it with species like California condors to provide them with clean food. So it's not unheard of and you can see the hand of humans and conservation of many species.

CURWOOD: Well, how do you feed a hungry polar bear?

DEROCHER: Very carefully for starters, and certainly not close-up. But what we argue is that probably because the prey of polar bears is also going to be highly endangered - Ring seals and Bearded seals are not going to have a good time with disappearing sea ice - so we're probably looking at alternate food sources. We really suggest that we’ll probably be dealing with sort of commercial polar bear chow similar to what a polar bear would see in a zoo.

CURWOOD: Wait a second; you start feeding a polar bear chow, they get used to the handout from folks, I mean, you don't have a wild polar bear anymore.

DEROCHER: No, and that's really what we talk about in this. In some places down the road, we may be looking sort of at what we would call a semi-wild bear park model, which is not inconceivable in some areas. What we would hope is that we wouldn't have to support the bears fully, that there would still be enough sea ice forming in some of these areas, that the bears would disappear and go hunt seals when they are available - but this would be sort of a means of keeping the population more viable.

CURWOOD: So if I understand what you're talking about here, the notion is that, hey, maybe we should be feeding these bears when the time comes, so there will be more time to deal with the impact of climate change?

DEROCHER: None of the options we outlined in this paper really do much good in the longer term if we don't deal with greenhouse gas emissions. The whole field of conservation biology hinges on the idea that you have the habitat of the species in place, so that you can actually keep them alive in the wild. The big challenge for polar bears, and what’s different compared to a lot of terrestrial species is we’re just losing sea ice at such a rate that it's hard to believe we’re going to turn this around in time to save most of the polar bear populations. What we’re hoping is we're going to hold onto some bears at very high latitudes in the Canadian Arctic and probably in Northern Greenland and that that might be the sort of nucleus of an expansion of a population perhaps hundreds or thousands of years from now if the planet starts to cool down again and we start to see an expansion of sea ice into lower latitudes again.

CURWOOD: Now there’s some people out there who argue that polar bears may in fact be able to adapt to changes in the climate and just change their diet to rely less heavily on seal blubber. How do you respond to that argument?

DEROCHER: Well, it’s pretty simple, I mean, we played out that scenario about 10,000 years ago in the Baltic Sea. We have very good evidence of fossil polar bears being all around Finland and Sweden and Denmark, in Northern Ireland, because the planet was a lot colder then. It was an Ice Age; the bears were very far South; we don't have polar bears in Ireland and we don't have them in Sweden or Finland anymore. Basically the bears blinked out when the sea ice disappeared. So we know what's going to happen. It's pretty clear that highly specialized species like these don't adapt to climate change.

Biologist Andrew Derocher measuring a polar bear’s head. (photo: Andrew Derocher)

CURWOOD: So in the end, Andrew, what you think we need to do to save the polar bear?

DEROCHER: There’s a simple solution to saving the polar bear and that’s really that humanity has to deal with two issues. One is overpopulation and excessive use of fossil fuels. Until we can deal with those two issues, the future for polar bears is definitely going to be challenging. But it's not just polar bears. It’s going to be so many other species and ecosystems that are going to be pressed so hard by climate change. At the end of the day, the climate’s warming; polar bears are going to be one of the clear victims of it.

CURWOOD: Andrew Derocher is a Professor of Biology at the University of Alberta. Thank you so much.

DEROCHER: It’s been my pleasure.

Related links:

- Andrew Derocher’s Book Polar Bears: A Complete Guide to Their Biology and Behavior

- Andrew Derocher’s faculty page at the University of Alberta

- “Rapid ecosystem change and polar bear conservation” by Andrew Derocher et al

[MUSIC: Beaver & Krauss “A Short Film For David” from Gardharva (Rhino Records 1970)]

The Thrills and Spills of Backyard Hockey

A young goalkeeper (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Every year, when the temperature drops low enough, Canadians take to the ice. And when there isn’t a pond in the neighborhood, they make their own. Backyard skating rinks are about as common in Canada as driveway basketball hoops in the United States. Bob Carty sent us this audio postcard from his neighborhood outside Ottawa.

[SKATING, A CHILD FALLS AND WHIMPERS]

CARTY: You okay? What happened there?

CHILD 1: I plunged into a snowbank head first when I was skating too fast.

CHILD 2: He just couldn't stop somehow, and he just slammed into a snowbank.

CARTY: Are you okay?

CHILD 1: Uh huh.

CHILD 2: Don't try to skate backwards when you haven't even tried it yet, or practice. That's pretty much it. A bruise map is kind of like a map where it shows you where all your bruises are. Those kind of things.

[CHILDREN PLAYING]

WOMAN 1: When I was a kid, I remember the boys always used to play hockey in my friend’s backyard. And my brothers - I have three brothers - they would use me and other little sisters as goalposts.

WOMAN 2: [LAUGHS] I learned how to skate with the kitchen chair. It had metal legs, and my creepy older brother tried to get me to lick the steel, but no, I didn’t do it.

MAN 1: How to make a backyard rink, by Howard Purchase of Mt. Pearl, Newfoundland. All you need is snow, water, patience, and a cold day. When planning a rink, make sure your hose can reach the area where you are putting the rink. To start, pack the snow solid with a shovel or a rented roller. Or have some children run around on it for a while. They love it, and it gets the job done. There are two ways to make a backyard rink, with plastic, and without plastic.

Backyard hockey rink (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

MAN 2: The first year we started the rink, and tried to do the whole thing in a traditional manner. You’d be out here; you’d be stomping on the snow; you’d put slush and try to have banks of snow on the sides. I was lucky that year because we had good conditions. Last year was a bad winter for making rinks. We didn’t have any snow at the start. So what I was doing was out in the front yard, and I was shoveling all the snow off up the driveway - and wheelbarrowing to the back.

[LAUGHS] That wasn’t enough snow, so then I started shoveling the front street. And then I started shoveling the neighbor’s driveways, but wasn’t going anywhere. And so I finally broke down and started to introduce technology.

MAN 2: Jiffy Rink; it’s an instant skating rink the size of approximately 10 feet by 20 feet. It's a big bag and you fill it up with water. And after it freezes over, after 24 hours it freezes over, the top piece you pull off. You just pull it right off and there you go. There’s your rink.

MAN 1: This year I was planning to buy these bags again, and then my wife was on the internet and found out that there are companies out there that will sell you plastic sheets as liners for your rinks, and so we went and we ordered them on the internet.

[SWEEPING]

MAN 1: Why do I sweep? What you're trying to do is to have as flat a service as possible when you put the flood down. Any little bit of snow, any chip of ice or something like that, it’s going to spoil that. I know it's sad; it's a pretty sad statement, but this is about perfection, making the perfect rink.

MAN 3: I tell people I think my deepest thoughts at six in the morning out there with a half inch hose. And I suppose there is a certain satisfaction in making flat ice.

WOMAN 3: It’s pathetic. [LAUGHS] He’ll go and get the hose and he’ll drag it along slowly like a snake. [WATER RUNNING] And you know it’s great because if we had to go pee, we didn't have to walk down from the park. We could just skoot in the back door and then we’d skoot back out and we’d be skating again and it would only take a couple of minutes.

[CHILDREN PLAYING OUTSIDE]

[MUSIC: Fitzgerald: Neil Young “Born In Ontario” from Psychedelic Pill (Reprise records 2012)]

CURWOOD: Our audio postcard of backyard skating rinks was produced by Bob Carty.

Related link:

Bob Carty’s website

Rinkwatchers and Citizen Climate Science

The Rinkwatch scientists hit the ice (photo: Wilfrid Laurier University)

CURWOOD: And now, some Canadian scientists are turning skaters like those into citizen scientists. They want to use homemade rinks to generate awareness, and data, about our warming climate. Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald has the story.

FITZGERALD: If you want to get Canadians to care about something, connect it to ice-skating.

MCLEMAN: If you’ve ever seen a Canadian five-dollar bill, we actually have a picture of a bunch of kids skating on a pond. It’s on our money because it’s in our bones.

FITZGERALD: That’s Dr. Robert McLeman, professor of Geographic and Environmental Studies at Wilfried Laurier University in Ontario. These days, he says, the backyard rink is under threat.

MCLEMAN: With global warming, the backyard skating experience may be an endangered species in coming years.

FITZGERALD: Although he’s worried about Canada’s favorite winter pastime, Professor McLeman sees the slushy rinks as an opportunity to gather data on the changing climate and build awareness about global warming. And he’s enlisting…

MCLEMAN: …an army of citizen scientists right across North America.

The Rinkwatch team. Left to right: Haydn Lawrence, Robert McLeman, Colin Robertson (photo: Wilfrid Laurier University)

FITZGERALD: Professor McLeman and his colleagues recently launched Rinkwatch.org, a website that allows people to pin the location of their backyard rink on an interactive map and upload information about daily skating conditions.

MCLEMAN: We’re simply asking people could you skate on the rink Wednesday or Thursday this week because of the weather. And if it was cold enough you just click yes or no.

FITZGERALD: For good skating, the temperature needs to stay below about 25 degrees Fahrenheit.

MCLEMAN: And we pool that data from right across North America, and then we can start to observe trends and patterns of what’s going on there.

FITGERALD: He says the reaction to Rinkwatch has been overwhelming, and not just in Canada.

MCLEMAN: Our server started to crash immediately in the first week. Right now we have over 1,000 registered users and over 750 skating rinks from the Yukon Territory in the Northwest right down to Massachusetts.

FITZGERALD: I had to see for myself. So I grabbed my laptop and headed over to the website.

All right, Rinkwatch.org. [COMPUTER KEYBOARD TYPING] Ah, it says: “Welcome to Rinkwatch: where backyard skating meets science.” Little skating stick figures that represent the rinks. They’re all over the place. Ha, there’s one in Norway and another in Greenland… And one way up in Russia.

The map is color coded. It looks like the blue icons represent rinks with good ice, and the red icons represents rinks that are not skatable. It looks like the rinks up in northern Canada seem to be doing ok, but there’s a big cluster of red skaters right around the U.S. border which makes sense given some of the erratic weather we’ve had.

MCLEMAN: This has been a really tough winter. There’s been a lot of freezing and thawing, which is really tough on backyard rinks.

FITZGERALD: Climate scientists predict that the weather is only going to get more erratic in years to come. Professor McLeman and his colleagues hope to use Rinkwatch to track changes in the length of the winter and variability in temperatures over the next few years. Along the way, they will involve thousands of everyday people in the scientific process.

MCLEMAN: Environmental change seems to be speeding up and having greater impacts on our day-to-day wellbeing. So we need to get people involved in doing something about it, and this is one way I hope we can.

FITZGERALD: One of the biggest challenges for climate scientists is making numbers matter. 392 parts per million CO2 in the atmosphere doesn’t mean much to most people. But perhaps projects like Rinkwatch can help make those figures relevant by showing global warming’s growing impact on our culture.

For Living on Earth, I’m Emmett FitzGerald.

Related links:

- Rinkwatch

- Robert McLeman’s Blog

CURWOOD: Coming up...re-evaluating the naturalist that some call the creator of American Science. That's just ahead on Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Beatlejazz: “Beautiful Boy” from All You Need Is Love (Lightyear Records 2007)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway, for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Women & Population

One Billion Rising event in San Francisco (Photo: Charlie Korda)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. On Valentine’s Day the world woke up to allegations that South African Olympic athlete Oscar Pistorius had shot and killed his girlfriend, model Reeva Steenkamp in the heat of a domestic dispute. The incident highlighted what some, including eco-activist Laura Turner Seydel see as a key to many problems. Not only is violence against women simply wrong, Ms. Seydel said in a recent speech, but the unfair treatment of women around the world also fuels troublesome conditions from poverty to overpopulation. Laura Turner Seydel joins me now on the line from Atlanta. How are you, Laura?

SEYDEL: Oh I'm very well, Steve, how are you?

CURWOOD: I’m doing OK. Let me ask you about a talk you recently gave at a women's event where you made the connection between the population problem and empowering women.

SEYDEL: Yes, and there really is big connection - obviously we are more than seven billion people on the Spaceship Earth. And like you’ve said, I've made the connection, and there are many others including Dr. Lester Brown that says if we promote and uplift the status of women and girls, that naturally the population fertility rates will come into check. And this really means that we need to give women and girls access to reproductive health care and family-planning and contraception. And you know we also have to make sure the girls are staying in school, and that way they put off early marriage and early childbearing - which is a real struggle when you're young and you're trying to find your way in the world. And it's proven that when you do that the population rates will come into check.

Laura Turner Seydel (Photo: Laura Turner Seydel)

CURWOOD: We have a rising population in the United States which is unusual for an industrial nation. We have this huge pay gap between men and women in the United States. What relationship is there, do you think, between our population rise and the discrimination we still seem to see against women in United States?

SEYDEL: Well, I really believe that there are a lot of things happening to make sure that women are paid equally to men. And I can just say, for instance, Eve Ensler, who started V-Day, and there’s this global campaign called One Billion Rising, it’s really to end violence against women and girls. And the statistics are staggering - one in three women will be brutally beaten or raped in her lifetime.

And I think you have those kinds of atrocities happening in this country and around the world, but it's easy to take advantage of women in other ways. And I know women are not being paid equal, and they’re sexually objectified in this country, in media and in film. And women just need to come together and rise up against all of these atrocities and unfairness in the workplace. And I think Eve Ensler with her global campaign that has a series of events on Valentine's Day this year will make women think about all of these issues at one time, and to strike, dance and rise up on behalf of their sisters. And we’re not going to leave enlightened men out, by the way. It’s really all hands on deck here. But I do think if there's consciousness about, everybody's thinking about it, then we can start pushing corporate CEOs to add more women to the boards and to pay them equally - and to make our world a rape and violence free zone.

CURWOOD: Eco-activist Laura Turner Sydel. Thank you so much for speaking with me today.

SYDEL: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- Laura Turner Seydel

- Eve Ensler and V-Day

- One Billion Rising

[MUSIC: Jose James “Do You Feel” from No Beginning, No End]

Louis Agassiz

Christoph Irmscher, is author of the new book, Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science. He’s a professor of English at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. (Photo: Annie Sneed)

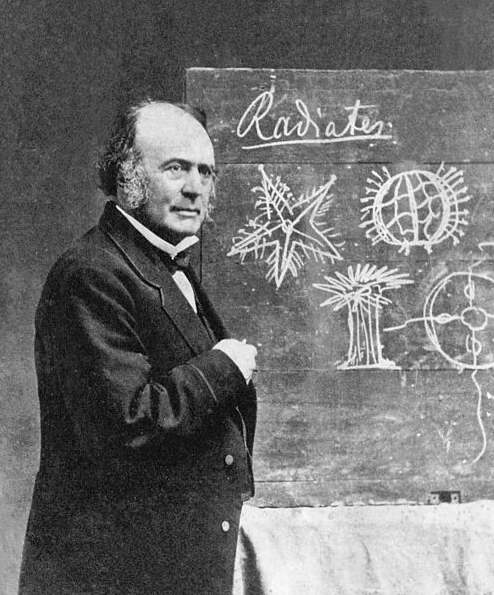

CURWOOD: Harvard University’s Museum of Natural History was founded by the great 19th century naturalist, Louis Agassiz. Passionate and popular at the time, today Agassiz has a mixed legacy; he was both an enthusiastic racist and a denier of Darwin’s theory of evolution. Professor Christoph Irmscher of Indiana University at Bloomington is author of a new biography called “Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science.” As we spoke during a visit to the Museum Agassiz founded, he said the man was hard to classify.

IRMSCHER: Louis Agassiz was a Swiss naturalist, he was a paleontologist, he was a zoologist, he was a marine biologist, he was an embryologist. There was no limit to his interests, and he brought the comprehensiveness of his interests to the United States, trying to instill the love of science in the masses.

CURWOOD: So let’s get Louis Agassiz from Switzerland to the United States, starting with his upbringing. How did his upbringing spur his passion for science?

IRMSCHER: He was born in Môtier, a small village close to a lake. He was an avid sportsman, avid outdoorsman, avid collector. His father was a country parson who did not encourage his plans to become a scientist, and that's what he really wanted to be, and he didn't want to become a doctor, that was his father’s career plan. He compromised by getting a degree in medicine, but getting a degree in natural history at the same time. And he studied with the great Cuvier, the greatest biologist of his time, as he saw it, and he acquired the mentorship of Alexander Van Humboldt who is probably the second great man. He had enormous nurturing. Coming to America in 1846 is the best career move that could have happened. What also happened is that his marriage failed. His first wife - who was not equipped to put up with somebody whose main interest wa science and hanging out with his buddies in the mountains and trekking on glaciers - she did something unprecedented - she took the kids, left him, moved out, at that point the invitation came to come to Boston.

CURWOOD: Louis Agassiz was famous for his work on glaciation. This was big time for Agassiz and his glacier work. He’s really among the very first to say we had ice ages.

IRMSCHER: He was the first to promote the notion of the ice age publicly, but there were people who had been working on it. There were scientists in Switzerland who had been talking about this for some time. There were even guides, mountain guides who had discovered things they would share with Agassiz. Agassiz was always very adept at taking an idea that other people had been thinking about and making it into his, and promoting it as such, and it happened in his career again and again. He had a falling out with somebody who basically said, “I did this and you’re taking my work.” In this case, it was a fellow student that he met in Munich who had been working on similar things, and who unfortunately would scribble his notions, his ideas, on loose sheets of paper, but not take them to the public. Agassiz did.

CURWOOD: So how did Agassiz the great naturalist first become recognized for his scientific prowess?

IRMSCHER: He first became recognized essentially for his work on Brazilian fish. He, when he was a student in Munich, he was promoted by one of his professors who was working on a volume about Brazilian fish, and Agassiz was the one who completed it, and that was essentially what put him on the map. He was very proud and he wrote to his sister at the time, ‘would it not be a great thing if the best book in our father’s library is a book written by me?’ And then he embarked on many multi-volume projects, one of which was about fossil fish. That was really what got the most attention and what kept encouraging him - work on the fish, complete your fish.

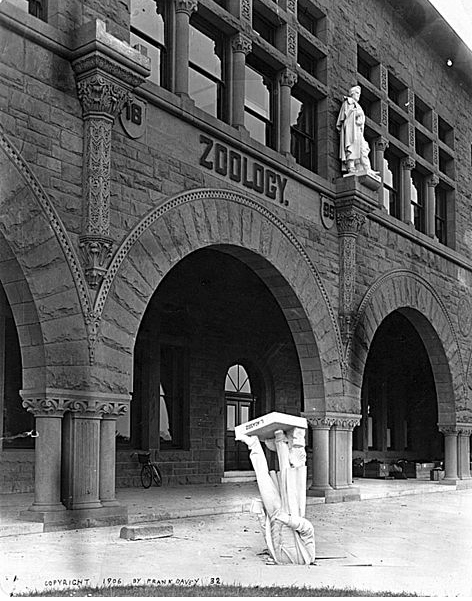

The museum complex, which includes both the Harvard Museum of Natural History and the Museum of Comparative Zoology, founded by Agassiz. This building was not built until 1892, long after his death. (Photo courtesy of Harvard Museum of Natural History).

CURWOOD: We’re in the Museum of Natural History here at Harvard that Louis Agassiz founded, and we’re in the room that has all these fossil fish. What of this collection do you think he knew something about directly?

IRMSCHER: This is actually a fossil fish specimen that he collected that was what his multi-volume work on fossil fish was about. Looking at the past, trying to find traces of life in fossil specimens. On his lecture circuit one of the things that he perfected that was one of his party tricks, he’d ask audiences to give him a scale of any fish and he would, from that single scale, draw in chalk the fish on the blackboard with both hands because he was ambidextrous and so the fish would emerge. He would ask the audiences to weigh in on what else was missing. The fins, the head and finally a living fossil fish. An oxymoron would rise before his audiences.

CURWOOD: Louis Agassiz was very prominent in his time, obviously, but he was also one of the fiercest critics of Charles Darwin, and Darwin's theory of evolution. Why did Louis Agassiz so adamantly object to the notion of evolution?

IRMSCHER: He believed that God's hand was visible in creation, that everything that had been created was supposed to be, or had been ordained to be by God. So there was this divine purpose in nature. He felt - and this is where things get perhaps a tad provocative - he also felt that the scientist was capable of deciphering God’s plan to the extent that there really were no secrets in nature for Agassiz. Secrets are there just because you have not uncovered them yet, but it was not a hypothesis that made any sense to Darwin.

He didn’t need a divine principle to describe nature. He described nature as unfolding on his own terms without any human presence required. There’s no human observer required. For Darwin, as he later said in “The Descent of Man”, there’s no more amazing instrument than the brain of the ant. That is not something that Agassiz accepted as a working premise, human superiority was what underlies all of Agassiz’s thinking, all of his work. It's very close to Emerson in nature - Emerson says at one point that the ant is interesting precisely for the ray of relation that goes from the ant to me.

CURWOOD: So what was the nature of the personal relationship between Charles Darwin and Louis Agassiz?

Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood talking with author Christoph Irmscher. (Photo: Annie Sneed)

IRMSCHER: It was a relationship that started with Darwin respecting Agassiz for his knowledge of data. Field work was Agassiz’s specialty. Darwin always relied on observers in the field that would provide him with things that he needed. It started with Agassiz essentially encouraging him to work on barnacles which Darwin did, and it was work that was very important for Darwin en route to the “Origin of Species”. Agassiz would provide him specimens, and the more Darwin realized what he was working on, where he was headed, the clearer it became to him that Agassiz would be his main target. And very, very fortunately for him, Agassiz’s colleague at Harvard, Asa Gray, a brilliant botanist, became Darwins’s respondent, became his associate essentially in promoting the theory and Asa Grey became quite brilliant in provoking Agassiz into making public statements, into embarrassing himself publicly in service of Darwin’s theory. Darwin would continue to write to Agassiz for information that Agassiz would still try to answer. Darwin sent him a complimentary copy of the “Origin of Species” offering it as he said to Agassiz “in the best spirit of scientific inquiry”. And the heavily marked up copy is still here at Harvard - Agassiz’s copy of Darwin’s “Origin of Species”.

CURWOOD: He didn’t tear out any pages?

IRMSCHER: He did not.

CURWOOD: So Louis Agassiz’s first wife walks out on him - he’s insufferable, and he comes to the United States, and he gets married, and not just to an ordinary woman, but to one of the first families in Boston - Elizabeth Cabot Cary - I believe was her name. How did that work out?

Louis Agassiz in 1870. (Photo: Wikipedia)

IRMSCHER: It worked out extremely well for him. He married a woman who was very gifted - she was a talented writer - and she became his public voice basically. She became the woman who wrote down his lectures, published them as articles. She became later on the founder of Radcliffe College, which some people see as a direct outgrowth of the kind of training she had received under Agassiz. She was in the field. She would always distance herself a little bit from what was going on and would say, “I’m just an amateur.” But in order to write the things she did, she had to be much more than an amateur.

CURWOOD: So Louis Agassiz may not have been such a big deal without this woman in his life.

IRMSCHER: He was a big deal when he came. He would have had a hard time maintaining his big deal reputation without her.

CURWOOD: Here in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where we are at the Museum of Natural History at Harvard, he’s rather famous for his racism. Why was Louis Agassiz such an outspoken racist? Why did he care?

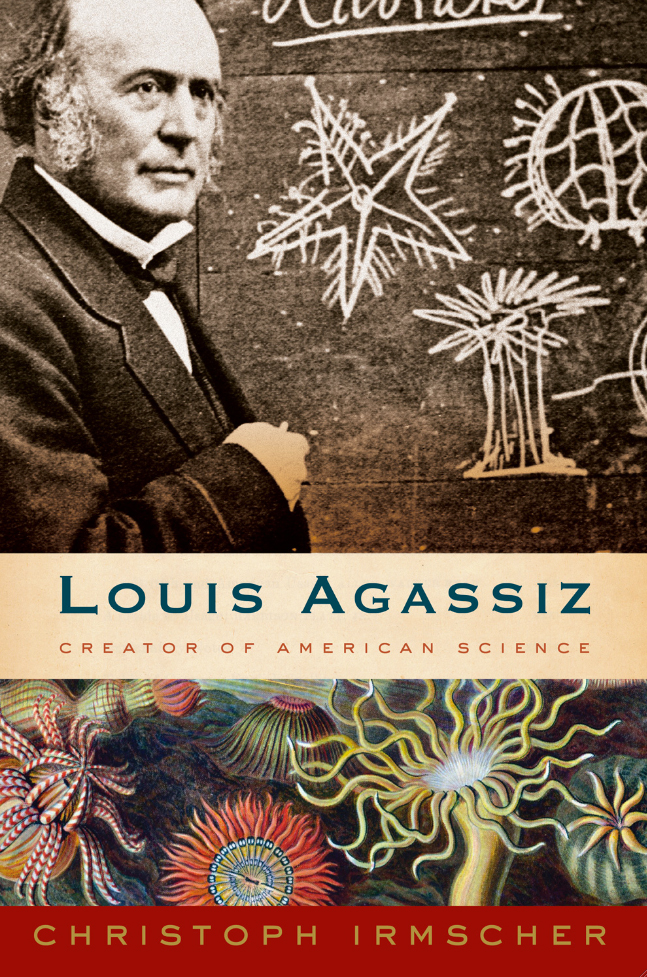

(Photo: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

IRMSCHER: It’s a complex story. Race played no real part in his scientific work before he came to the United States. When he came to the United States in 1846, he realized quickly that having an opinion on race, being an expert on race, would further bolster his public importance. He believed in biological differences between races as if they were species. He believed there were biological differences that made it impossible for blacks and whites to intermarry. And he would publicly talk about these biological issues. All of it sounds very offputting - one thing that we need to remember is that most of his racial opinions were shared by people at the time. None of this was important for the rest of his scientific work. It is a puzzling fact that he got so engaged in it. Do I wish he had not said any of this? Yes, but in part the book got its impetus from the complexity of this man with many, many affable, many, many positive sides - and other sides that are deeply troubling - and they’re part of the same coin.

CURWOOD: Indeed Louis Agassiz had many, many faults - selfish, plagiarizing, racist, braggart - yet he was admired by many people in America who looked up to him. Why do you think?

During the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, a statue of Agassiz fell from its niche on the front of the Stanford University zoology building. Stanford President David Starr Jordan later wrote, "Somebody – Dr. Angell, perhaps – remarked that 'Agassiz was great in the abstract but not in the concrete." (Photo: Wikipedia)

IRMSCHER: The sheer energy, the sheer passion, that he brought to his work, it was deeply admirable. Here was a man who would show up in the lecture halls, his pocket stuffed with specimens he would pull out. And he would hold something up, he would speak with this absolutely attractive French accent. He would talk about “leedle fish, leedle beetles” he would pull these things out and show them as he was demonstrating. He was a man who would take his students to the beach, and would ask them to go bodily into the water; “If you can’t get the jellyfish out of the water, you need to go where they are.” He would encourage his students to touch things. This was fieldwork in the modern sense. This is what he brought to America, he changed the face of science education permanently. That's part of his legacy. So that's all part of Louis Agassiz as he was at the time. And it’s part of the mesmerizing force that he exerted on the people around him. There’s a famous story that they like to tell that at one point when his eyes had given out from too much looking, and looking was extremely important to him, he used his tongue to taste a fossil specimen, to actually lick it because he wanted that sensory contact with the specimen in front of him, and that was very different from the kind of science people were used to. He believed that science had to be woven into the common life of society, at which he thought that everyone should be knowledgable about science. Everyone theoretically could become a scientist given the proper instruction, which of course someone like Louis Agassiz could provide.

CURWOOD: Christoph Irmscher’s book is called “Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science.” Thank you so much.

IRMSCHER: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The Harvard Museum of Natural History

- The Museum of Comparative Zoology

- More on author and professor Christoph Irmscher

Earth Ear: Daybreak at Iguaçu

Iguaçu Falls (Photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: We leave you this week deep in the rain-forest.

[EXOTIC BIRDS CHIRPING]

A chorus of brilliant-colored birds greets the dawn near Iguaçu Falls close to the border of Brazil and Argentina.

[MORE EXOTIC BIRDS CALLING]

There are over a hundred bird species in the area -- including toucans, motmots, woodpeckers, flycatchers, antbirds, and manakins.

bigstock-Toucan-152626.jpg

Dan Grossman and I recorded this dawn chorus when we visited the falls a few years ago.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Annie Sneed, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. We had engineering help this week from Dana Chisholm. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at justeatorganic. com. Support also comes from you our listeners. The Go Forward Fund and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at PaxWorld.com. Pax World, for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth