May 3, 2013

Air Date: May 3, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

UN Leader Optimistic About Global Climate Deal

View the page for this story

Christiana Figueres, Executive Secretary of the UN Climate Secretariat, visited the Living on Earth studios on her way from UMass Boston to international negotiations in Bonn, Germany. The Bonn session is one of many leading up to a meeting in Paris, France in 2015 when nations have pledged to sign a binding agreement to curb global warming gases. Secretary Figueres told host Steve Curwood she's sure there will be a global deal because there is no other choice, and it's in every country's interest. (15:00)

Greener Concrete

/ Qainat KhanView the page for this story

Qainat (Kine-att) Khan reports in this LOE Science Note about a greener, stronger concrete developed by Kansas State University professor Kyle Riding's team of researchers. (02:05)

Solar Shines On

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Thanks to incentives and growing awareness, solar panels are becoming increasingly popular across the country. Living on Earth's Helen Palmer had an array assembled on her roof last year, and in this update she tells host Steve Curwood that, among other benefits, the panels have eliminated her electricity bills. (07:35)

Electric Cars To Buffer the Grid

View the page for this story

A team based at the University of Delaware has developed a way to use electric car batteries to make the grid more stable and resilient. One of the project’s leaders, Professor Willett Kempton, tells host Steve Curwood that the system could earn real cash for electric car owners. (07:45)

Climate Change and Land Slides in the Northwest

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

Climate change experts predict an increase in precipitation in the Northwest, which could mean more landslides in the future. EarthFix’s Ashley Ahearn reports. (05:30)

Flood Control With New Hybrid Grass

View the page for this story

As the atmosphere heats up, flooding is on the rise throughout the world. Kit Macleod, a scientist at the James Hutton Institute in Scotland, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss a new hybrid grass his team helped breed. It restructures soil to reduce runoff from pastures and could help cope with global warming. (05:25)

Robins on the Hunt-By Ear

/ Jeff RiceView the page for this story

You may have noticed the way robins jauntily cock their heads as they hop along the ground this time of year. Turns out they're listening, very carefully, for the movements of worms under the grass. Jeff Rice reports. (02:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Christiana Figueres, Willet Kempton, Kit Macleod

Reporters: Helen Palmer, Ashley Ahearn, Qainat Khan

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The latest round of UN Climate talks are underway in Bonn Germany, and Christiana Figueres, the negotiations chief, says she's optimistic about finding a real solution to global warming.

FIGUERES: We don't have an option. We don't have a plan B because we don't have a planet B. We are going to solve this.

CURWOOD: How to chart a path forward to a global climate deal by 2015. Also, listening very intently for very quiet sounds under the earth - the sound that's made by worms.

ROBINS: They're extremely quiet. The only way we were able to record them was to put them in a chamber called an anechoic chamber and use a very high sensitivity directional microphone and pointing it right at the soil about centimeter from the worm.

CURWOOD: The world under our feet, and much more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

UN Leader Optimistic About Global Climate Deal

Host Steve Curwood with UNFCCC Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres. (Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In case anyone was wondering if global warming is getting worse, consider the number 400. That’s how many parts per million of CO2 the world is likely to reach later this month, and that's higher than it's been in more than three million years.

CO2 is the major greenhouse gas associated with human activity, and according to the Global Monitoring Division of NOAA we’re already well over 399 this year - up from a bit more than 350 back when the UN first started climate negotiations in 1992. And on April 29 UN climate negotiators came to Bonn, Germany for the latest in a series of meetings over the next two years aimed at a climate agreement that binds all nations, after a meeting in Copenhagen intended to do that ended in failure in 2009.

Christiana Figueres is the executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, and she stopped by the Living on Earth studios on her way to the meeting in Bonn. Madame Secretary, welcome to Living on Earth.

FIGUERES: Thank you very much for the invitation.

CURWOOD: Copenhagen is largely considered to have ended in disaster. Why did you take this job?

FIGUERES: I took this job because I believe this is the most important thing that humanity is doing right now. We have never faced a more serious challenge. And I thought, “You know, there may be some little grain of sand that I can contribute to this.” And, honestly, I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror, having two children, and say I did everything I could unless I really tried to do my best. So here I am.

CURWOOD: But let’s consider, the United States is out - although it originally signed Kyoto, it then took it back. Canada is out, Japan won’t go ahead with more commitments…what’s the point of the Framework Convention on Climate Change today?

FIGUERES: The point continues to be the original point, which is to shepherd governments toward their collective efforts to bring down emissions - which they haven’t done yet as a collectivity - and to support their efforts to adjust to the now inevitable effects of climate change. And I am the first one to admit we can’t tick that box, we can’t say “done,” “succeeded,” but we are definitely moving in the right direction.

CURWOOD: What has been accomplished since Copenhagen?

FIGUERES: A couple of things are really, really different now than Copenhagen. First of all, governments have actually, formally, committed themselves to come to a global agreement. They had not done that by Copenhagen. They have now said, “We are going to negotiate a legally-based universal agreement,” and they have set themselves the timetable for 2015.

Secondly - unfortunately, actually - there is much more evidence for climate change. There is not one single country not being affected by climate change - the United States included, because I don’t have to remind anyone in this country about the droughts of last year and about Sandy that hit certainly New York, but the East Coast.

So much more evidence of climate change, but also the good news is there is much more going on. We have around the world already 30 countries that have binding climate change legislation. We have 100 countries with renewable energy legislation. We have many more countries with energy efficiency incentives. We have the private sector moving in to invest in clean technologies. There’s much more bottom up activity to respond to climate change and to address climate change than we had before.

In addition to that, what governments have actually moved on is, they’ve moved into the Kyoto Protocol second commitment period, which started on the first of January of 2013. The reason why the Kyoto Protocol is important is because it is the treasure box of the rules and regulations that give integrity, environmental integrity, to the efforts of governments. Without those rules and regulations, we wouldn’t know whether we’re progressing or not.

The downside to the Kyoto Protocol, as we have it now - because you mentioned some countries have exited - is the fact that it only covers 10 to 12 percent of global emissions. So governments understand that, and they understand that they actually need to cover 100 percent of emissions, which is why they have now committed themselves to a global agreement by 2015.

CURWOOD: Some would say that the structure of the Kyoto Protocol itself—to have developed countries go first—was flawed, given that it required a country to surrender what they perceived to be a competitive advantage to big, powerful developing countries such as Brazil and China and India, and especially as progress was delayed for so long. What’s your opinion of that in hindsight?

FIGUERES: I don’t think the Kyoto Protocol was flawed. It was very well fundamented on the principle of historical responsibility. It is incontrovertible that industrialized countries - in particular, the large industrialized countries - let’s talk about the United States - have much more of the historic responsibility. So the Kyoto Protocol was conformed according to that rationale, and that was fundamentally correct.

Now, however, we are moving into a different future. And now it is not just about historical responsibility; it is also about future capacity to contribute to the solution, and it’s also about the gradual recognition that the countries are all coming to that actually, it is a collective responsibility of all countries, no matter how small and how large. We are now at the point where every single country has to assume some responsibility according to their capacities.

The other thing that is very important is to realize that many countries are coming into their efforts on addressing climate change not just because of their sense of moral responsibility but perhaps for a much more compelling reason, because they understand that this is their greatest opportunity, because they understand that we are moving toward a lower-carbon economy and it is in their interests to remain competitive in the future low-carbon global economy that they themselves become low-carbon. Otherwise, they’re going to become a beast of the past.

CURWOOD: So the two biggest emitters on the planet...

FIGUERES: The US and China.

CURWOOD: The US and China, yes, recently announced that they are going to set up a joint task force to look at greenhouse gases. But that’s outside the worldwide comprehensive agreement of Kyoto. What’s your view of this process?

FIGUERES: I very much welcome these efforts on both the US and the China governments. Both governments have been having bilateral conversations for quite a few years and have actually been collaborating with each other because they understand that they need each other today and in the future.

But bottom line: every single country needs to be at the table and needs to have its interests represented. Just because Tuvalu doesn’t have any global responsibility in the past, present, or future doesn’t mean it’s not being affected. So all countries, large and small, need to be at the table, need to agree to the framework that is going to take us forward, but it is fundamentally clear that the largest economies need to come to an agreement with themselves.

CURWOOD: What do you think is needed politically to get the United States aboard a binding worldwide deal to reduce global warming gas emissions?

FIGUERES: You know, I actually think the United States is already moving in a very, very impressive direction. I was in California last week to congratulate California for its leadership, certainly in this country. But also across the United States, we already know the EPA has put in transportation fuel standards that have helped. We know that they are working on finalizing the regulations on new power plants, and that will also help. They’re looking at a very broad array of policies and measures that can be taken under leadership of the federal government to actually bring the United States to what it has already promised, which is a 17 percent reduction in their emissions.

CURWOOD: That is rather like, you know, the couple that is living together - the US is doing all the stuff but not willing to sign, not willing to get married to the rest of the world, to have a deep commitment, and a deep expressed commitment.

FIGUERES: I think the US actually is intending to get married to the rest of the world. I can’t imagine that the US would want to live without the rest of the world. It would actually be pretty lonely. I do think that what the United States is doing is preparing the ground, and preparing the ground with China is absolutely key. But they will also have to come in with a commitment that is measurable, that is transparent, and that is credible. They have to convince the rest of the world that their efforts are credible and that those efforts are commensurate to the responsibility of the United States.

CURWOOD: Secretary of State John Kerry, who’s been a leader in the US, while he was in the Senate, on the matter of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, took great care to announce that this process is going forward. What do you read into that?

FIGUERES: John Kerry is fully aware of the importance of this topic. He is one of the most knowledgeable people in the United States on this topic. He is now bringing his political clout to bear on solving the problem. And he fully well understands that the United States needs to do its part, and that China needs to do its part, and that both of them need to agree with each other on how they are collectively going to support each other moving forward and how they are going to reach out to the rest of the countries.

CURWOOD: Now what about China? China has a long record of reducing emissions and has some fairly ambitious activities, but at the end of the day, they keep saying they want it to be a voluntary thing for them. How can China be brought to the table to, again, get married to the rest of the world with a binding agreement?

FIGUERES: Well, I also think China is very much looking to the rest of the world, and, in fact, to its leadership in the world and is not shying away from that. They have actually very, very ambitious targets on renewable energy, energy efficiency, building codes, vehicle codes. So they are doing their homework, also, and in fact every single one of the targets they have set themselves has not just been met - it has been exceeded. And they are also doing that for their own purposes. We have just heard over the past few days the terrible pollution situation that citizens in Beijing have had. So they’re doing it not just to save the world; they’re doing it out of their own national interest, which is the most compelling motivation for a country to move forward.

CURWOOD: How possible is it to get a worldwide agreement that binds all to important greenhouse gas emission reductions?

FIGUERES: You know, I’m optimistic that this will be done in 2015. For the very simple reason - two reasons: A, that governments have had a while to consider this and continue to reiterate their commitment to this, and B, frankly, because we don’t have a choice. The scenarios without a global framework agreement on this are too scary to even consider. And governments know that. So they are going to reach an agreement.

CURWOOD: How much time is left for the world to come to an agreement on this?

FIGUERES: This is not, you know, like jumping off a cliff…all of a sudden, there’s one magical date. What is absolutely clear is that the longer we delay our emission reduction efforts, the more expensive it’s going to become. It’s important to accelerate as much as possible the market signals that policy can give so that investors can shift their investments into the low emission technologies.

And they are doing that; we have already surpassed $1 trillion into renewable technologies around the world. And in fact, in the United States - I’m happy to share with you - just last year, just in the year 2012, the United States installed three gigawatts of solar energy, 13 gigawatts of wind. If you add both those two together, 49 percent of all the new energy that was installed in the United States last year - 49 percent was renewable energy. So we’re moving in the right direction.

CURWOOD: What’s the host country for the negotiation sessions in 2015? And what has been their record?

FIGUERES: France. France will be hosting us for 2015, and I am happy to share with you that the French government is already now - three years out - already getting ready for that. They have already chosen their lead negotiator, they’re putting their team in place. So I’m actually delighted to be already today working with the French presidency on this.

CURWOOD: Now later this year, the countries meet in Poland on their way to this big meeting in France in 2015. What needs to happen this year in Poland?

FIGUERES: This year in Poland, there needs to be much more clarity than we have right now as to what the milestones are going to be. What are they going to accomplish on the road toward the agreement? Because the draft agreement needs to be on the table by December of 2014. So it’s a very, very important year. I call it the “sponge year.” It’s a very important year in which they need to collect as much information from each other as to what their expectations - their collective expectations - are, what this framework is going to look like and how is it going to be flexible into the future, building flexibility into a legally-based framework is not an easy thing, but that is their challenge.

CURWOOD: Christiana Figueres, what gives you hope?

FIGUERES: What gives me hope is two things. Both the fact that the next generation - represented for me very personally by my daughters - expects us to step up to the plate. We are responsible adults. We cannot walk away from a problem that we fully understand. And B, what also gives me hope is that we actually have the tools. We have the capital. We have the technologies. We have the science.

It’s a question of focusing our political and collective civil will to actually solving this problem. I have no doubt that humanity rises to the challenges that we’re faced with. We have always done that in history. This happens to be the greatest challenge that we are faced with right now. But every other challenge that we have actually stepped up to in history has been the greatest challenge. So we don’t have an option. We don’t have a plan B because we don’t have a planet B. We are going to solve this.

CURWOOD: Christiana Figueres is Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Thank you so much for coming by.

FIGUERES: Thank you for the invitation.

[MUSIC: Sex Mob “La Strada” from Cinema, Circus & Spaghetti (Sexmob plays Fellini: The Music Of Nino Rota) (Royal Potato Family 2013)]

CURWOOD: You can hear more of our interview with Christiana Figueres on our website, LOE.org. Coming up...a sunny report from our in-house solar entrepreneur. That's just ahead here on Living on Earth.

Related links:

- More of the LOE interview with Secretary Figueres

- More about the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Kyoto Protocol

[CUTAWAY: Booker T Jones: “Harlem House” from The Road From Memphis (Anti Records 2011)]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Just ahead - how electric cars can make the power grid more efficient - and earn some cash for the car owners as well. But first this note on emerging science from Qainat Khan.

Greener Concrete

(bigstockphoto.com)

KHAN: Every year we use seven billion cubic meters of concrete. That’s one cubic meter for every person on Earth. And producing that much concrete also produces up to eight percent of carbon dioxide emissions worldwide. So researchers at Kansas State University thought, well, if we could find a way to make concrete go a lot farther, we could reduce the total concrete production and cut greenhouse gas emissions. Kyle Riding is an engineering professor at KSU and he and his team have created a concrete mix that does just that.

Most of the carbon dioxide in the concrete process comes from making cement. Cement’s the most important component in concrete, and it needs lime, which you make by heating calcium carbonate until it breaks down into lime and carbon dioxide. So to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, you need to use less cement in your concrete mixture. Riding’s team did this by replacing 20 percent of the cement in the concrete mix with silica. When silica's mixed into cement, it reacts to make concrete stronger and more durable. This is what ancient Romans did when they mixed their lime with volcanic ash.

And Riding’s team found this high silicate miracle compound in an unlikely place: the landfill. The substance - called high lignin residue - is the waste from a process used to make cellulosic ethanol. But this organic material is usually just trashed. So Riding’s concrete mixture could help to solve two problems: it could cut carbon dioxide emissions and reduce landfill waste. Which just goes to show, less can be more. That's this week's note on emerging science, I'm Qainat Khan.

Related links:

- Kansas State University

- Green Building News

Solar Shines On

Traver fitting the panels.

CURWOOD: We've been bring you updates on some of our stories these last few weeks - and one I've been curious about is the piece one of our team, Helen Palmer, put together about her quest with her downstairs neighbor Eric Grunebaum to get solar panels on their two family house. One thing that influenced them was the slew of tempting cash incentives available. Here's part of her report from last year.

The finished solar array at the front.

PALMER: Federal and local incentives have helped give solar a gigantic boost in the last couple of years. In 2011, the U.S. added 1.7 gigawatts of solar - enough to power about one and a half million homes. California leads the sun-powered pack - but Massachusetts ties Hawaii for second place in terms of incentives and strength of the market. Richard Sullivan is Massachusetts' Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs.

SULLIVAN: Right now there are great incentives there's certainly at the federal level there's tax credits, there are here locally in Massachusetts and the cost of manufacturing solar, the cost of installing solar has also dramatically come down.

Massachusetts Energy and Environmental Affairs Secretary, Rick Sullivan.

PALMER: Meantime my neighbor Eric was researching what those incentives and new efficiencies added up to in hard cash - he came upstairs.

[KNOCK AT DOOR]

PALMER: Come in!

GRUNEBAUM: Hi.

PALMER: Hi, Eric. He had an armful of folders...

GRUNEBAUM: So I got a price from so far from one company called Sun Bug...total price is $13,000...but then there are these credits you get from the state and federal government...the state credits are adding up to $3,300 roughly and the federal tax credit is $3000. Oh look, there's another state credit of $1,000 so the cost after all the rebates is $6,000. So it's actually cutting more than half off the price…

PALMER: There are dozens of tax benefits, grant programs and incentives to go energy green - 38 states have property tax breaks - 28 states have sales tax incentives - the list goes on. But this was the first time I learned about one of the biggest boondoggles of all - the cash you actually get paid.

Solar engineers up on the roof.

GRUNEBAUM: Every year, for every 1,000 kilowatts you produce, you get what's called a solar renewable energy credit, which everyone calls SREC, because it's too long to say that other thing. And it’s because utilities are required to buy solar energy.

PALMER: Yes, there's a requirement that the state generate so much from renewables, right?

GRUNEBAUM: Yes, it's called Renewable Portfolio Standard.

PALMER: Thirty states have mandatory Renewable Portfolio Standards - in most cases the green energy requirement goes up every year - Massachusetts demands 15 percent by 2020. And SREC prices vary from state to state - Pennsylvania paid less than $22 in June this year - while the Massachusetts price was $545. And the tax credits may go down. The federal credit is good through 2016, but state Energy Secretary Rick Sullivan says Massachusetts' credits will sunset.

SULLIVAN: These rebates and incentives are really designed to encourage the growth of the industry - but over time they will decline will eventually go away - and we're seeing that happen - we've seen the rebate offered go down I believe it's four times - again the goal is to get it to be zero and have private industry be competitive, the solar industry be competitive with the other sources of energy.

Half the panels up on the back of the house.

PALMER: To date, they've done their job; prices dropped over 40 percent in the last four years and in Massachusetts, at least 200 solar companies are trying to persuade businesses and homeowners to slap solar panels on the roof.

CURWOOD: Well, it's been just over a year since Helen slapped her panels on the roof and got them turned on - and now she's here in the studio for an update. Hey, Helen, how did that work out?

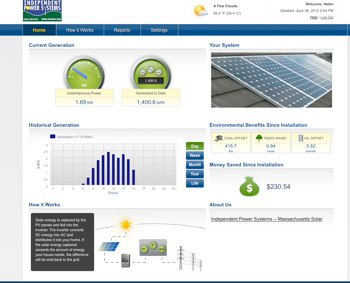

PALMER: Well, we can look. We can open up the laptop here. You remember my solar dashboard?

Helen Palmer’s computer dashboard, showing real time generation and savings.

CURWOOD: How could I forget? I think you’re kind of obsessed with this thing.

PALMER: I was, but it’s a bit better now. Look, you can see that I’m generating at the moment 2.82 kilowatts of power. It’s a sunny day - middle of the day. And overall, in the year, I’ve generated 4,683 kilowatt-hours altogether. That offsets 1,389 pounds of coal.

CURWOOD: That’s like a half a ton or more of coal.

PALMER: A half a ton of coal. Wow. And it’s also, what it’s actually saved in electricity costs is $770.

CURWOOD: And what have we got in terms of the electric bill?

PALMER: Ha! No electric bill. Not one since March 2012. And actually I just checked - we have a credit of $42.61 - so actually I think they've worked out pretty well.

CURWOOD: And what about those renewable energy credit payments for doing the solar stuff you that were expecting?

PALMER: Ah yes, the famous SRECs. Well, actually, those haven't worked out so well.

CURWOOD: I think I remember you talking about $500 every time you generated 1,000 kilowatt-hours. So 4,000 kilowatt hours, that’s more than $2,000...

PALMER: Yes, don't rub it in. I think what happened is we kind of caught a wave - the incentives that persuaded us to go solar persuaded thousands of other Americans too. Actually, in 2012 the US added 3 and a third GIGA-watts of solar power - that's twice as much as they put on their roofs the year before and nearly as much as the nation's largest nuclear plant can generate. So the price of the renewable energy credits dropped, as the market was flooded with folks generating clean power, the price per megawatt in Massachusetts slumped to $200. But still, in Pennsylvania, it was only $10. So, it’s not so bad.

CURWOOD: But what about the basic incentives and rebates? They still there?

PALMER: Yes, both nationally, and here in the Bay State, there's a special program called "Solarize Massachusetts.” That has lots of incentives and the Governor, Deval Patrick, he just announced a new goal of 1600 megawatts on roofs by 2020 - we blew through the last goal of 250 megawatts four years early.

CURWOOD: How unique is Massachusetts with all this?

PALMER: Not actually as unique as all that. It’s a very good set of programs, but actually most states have them. They have all sorts of grants, loans, property tax and sales tax breaks, lots of ways to persuade us all to go for green power.

CURWOOD: And Helen, before you go, I’ve got to ask you something else. You are our resident bee-keeper.

PALMER: Not at the moment because my bees died over the winter.

CURWOOD: In fact, that’s what I wanted to ask you. There's another update on another story we've been following - bees and the neo-nicotinoid pesticides - and those chemicals are suspected of being one cause of the massive die-off of honeybees.

PALMER: Yes, and the real new development is that in the European Union, where campaigners have been very vocal about the dangers of these systemic pesticides, 15 of the 27 EU member countries voted to impose a ban on three of the main ones. It's only limited - it’s just a two year ban on their use on flowering crops that attract bees. But campaigners and bee-keepers are very pleased and what they hope this will give bees a chance to recover, and also demonstrate that important pollinators are healthier when these pesticides aren't being used. And also, I mean, most importantly, that crop yield doesn't slump because of the ban.

CURWOOD: OK, Helen. Well, keep things buzzing for us will you.

PALMER: Well, I am getting some new bees!

CURWOOD: Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- Listen to the Original Story

- Follow Secretary Sullivan on Twitter

- Visit the Energy Smarts blog

- Massachusetts Dept of Energy and Environmental Affairs

- Independent Power Systems

- Computer plan of two solar systems on our house, separated by the dormer.

- The "very efficient" panels installed on our roof.

- A typical sized solar proposal.

- Eric's comparison chart.

- A summary of incentives state by state

- Statement from the office of Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick on reaching the solar power goals 4 years early—and setting a new goal

[MUSIC: Jorma Kaukonen “Sweet Hawaiian Sunshine” from Quah (BMG Heritage 1974/2003)]

Electric Cars To Buffer the Grid

The electricity hook-up for the Tesla, an electric sports car (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Now, electric cars are still big-ticket items, but a new system developed at the University of Delaware now allows electric car owners to sell some of the power stored in their batteries back to the grid when the car's not in use. This could ease some of the costs of electric cars, and give the grid a new, more efficient tool for keeping the grid stable.

"Load balancing" ensures that there is always enough power to go around. It keeps our lights from flickering and our clocks from running slow. Joining us now is Willet Kempton. He's Professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and the Environment at the University of Delaware, and a member of the team. Welcome to Living on Earth.

KEMPTON: Thanks, Steve, I appreciate it.

Professor Willett Kempton (photo: The University of Delaware)

CURWOOD: Professor, your system helps the grid balance its power. How does the grid balance its power now and what does the system that you've developed offer as an advantage?

KEMPTON: Well now the grid balances power by large generators that are run at half speed. So if you got a 100 megawatt power plant you run about half that, 50. And then when there's too much power you drop down at bit from 50 towards zero. When there's not enough you push up from 50 up towards your maximum amount. So they're shifting up-and-down these huge power plants.

CURWOOD: And that’s fairly inefficient.

KEMPTON: It is. You’re taking a big unit that’s supposed to be run at a single speed and you’re changing speed constantly. Plus, you’re only getting half the ability to produce power that the system was designed for.

CURWOOD: So what can the electric car do to be more cost-effective in balancing this load?

KEMPTON: Look, a car battery can either charge - the way if you were charging up for a trip - or it can discharge. There's several automakers that have car batteries that can discharge onto the grid. We’re using one of those. So that is the same thing as varying the speed of a power plant. If there's too much electricity on the system, we charge the batteries faster. If there's not enough electricity on the system, we discharge into the power system. So that allows us to take a totally clean device that changes very quickly, has very minimal wear and tear by moving up and down, and we can use that for the same purpose that large power plants are used for now.

What we're doing is asking, “well, there’s batteries out there...the average American drives one hour per day...that means 23 hours a day there's a big battery system that is already purchased.” And now we're just saying we got a second use for that. So you're driving, you know, if you’re typical, an hour a day - maybe you travel further, two hours a day - but that means another 22 hours per day that the car is parked and maybe some or all of that time it's close to an electrical outlet. So we’re going to give you some value for those other hours that you’re not driving.

The electricity hook-up for the Tesla, an electric sports car (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: So how does this benefit an electric car owner financially?

KEMPTON: Well, per car, so far what we've gotten...because we are on the market now - we’ve done all the permitting, paperwork, bidding and all that - we're getting about five dollars per car per day. So an individual car at that rate would earn $150 a month.

CURWOOD: OK. I've got an electric car. I’m plugged into your system, but now I want to jump in the car and go to work. I need all the juice that I need to get to work. How can I be sure that I’m going to have that juice waiting for me when I needed it?

KEMPTON: Well, if you sign up for our program, we’re going to ask you some questions. We’re going to say what’s your typical day’s driving? What would you like to have as the minimum amount? So if you have a car that has a 100-mile range, which would be typical for an electric car, maybe going to work is 30 miles there and 30 miles back. That would actually be a bit more than the average commute. So we’ll say you can’t plug in at work - maybe PRI hasn’t installed a charging station yet - so that means you need 60 miles on a typical day or add a bit to that just to make sure you don’t run out. We’d make sure you’ve always got 80 miles in the morning.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the wear on the batteries. You can shorten the life of a battery if you’re constantly drawing it down a bit and topping it off without fully discharging it. How does your system deal with that problem?

KEMPTON: Well, we have spent a lot of time thinking about this, and actually have gotten a bunch of patents issued. We stay in the middle of the charge. If you look at the wear pattern on a lithium-ion battery, which is what we’re using, most of the wear occurs when it's nearly all the way discharged or nearly all the way filled up. So if you think about the way your cell phone or laptop computer works and it's the same with an electric car, the standard way of doing it is you plug it in. It just goes all the way up to the top just in case you can take a really long trip tomorrow.

BWM’s electric Mini Cooper E, the car that is being used in the University of Delaware project (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

What we do is we have a predictive model try to predict how much is going to be needed, and generally we don't fill it up more than 60 or 70 percent. We're moving a lot around the 40 percent to 60 percent range but it turns out that doesn't wear the battery nearly as much as filling up to the top every day. So we have to measure it. We may wear the batteries a little more than typical use, or maybe a little less. We've worked a lot of trying to minimize that wear.

CURWOOD: So, scale is really important here, professor. How many cars do you need in any given area to really have this make sense?

KEMPTON: Well, we're using BMW Mini Es, which are fairly high power - not the highest power - but with those kind of cars we need 10 cars to have a sufficient amount to qualify as a generator.

CURWOOD: Only 10 cars? Wow. Cars use a lot of power.

KEMPTON: They do, but their size...here’s the way we win with this...it's kind of a serendipitous design issue - they're sized for you to get on that on-ramp, pedal to the metal and go 0 to 60 or 70 or whatever you do in 10 seconds or 15 seconds or whatever...so they've got the capacity to really push power out quickly and so we take advantage of that. That’s already designed into the car.

CURWOOD: How do you think your system might encourage the growth of the electric car business?

KEMPTON: Well, electric cars are still more expensive than gasoline cars. You get a fuel saving over over time. It's got electricity, more or less a dollar a gallon equivalent, so you’re doing great in terms of fuel costs. Of course it shows up on the electric bill rather than when you pump at the gas station. So that's good.

But the cost of these are higher, batteries are pretty expensive, so for right now electric cars are substantially more expensive at the sticker price level of the showroom. What this system does is provide an additional revenue stream for the electric car owner. And as I said, it’s about $150 a month, so that makes the whole owning and operating an electric car less expensive. It brings it down more close to the cost of a gasoline car.

CURWOOD: How important could your system be in our quest for a low-carbon future?

KEMPTON: Well, one of the characteristics of wind and solar, which are our most abundant low carbon and your zero carbon resources, one the characteristics of both of them is that they fluctuate and fluctuate with the forces of nature, not with when we need more or less power.

So storage or the balancing service that we're talking about which is needed today will be needed more and more in the future if we have more and more wind and solar. So if you have a system that is easily expandable, and in fact inherently expands as more electric vehicles are purchased and used, this gives us a low-cost way of leveling out the fluctuations of low-carb and resources.

CURWOOD: Willet Kempton is a Professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and the Environment at the University of Delaware. Thanks so much for joining us.

KEMPTON: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- U Delaware Project site

- Willett’s Kempton’s faculty page at the University of Delaware

[MUSIC: Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Heart’s Club Band “Drive My Car” from Beatles Instrumental Renditions (Purple Pyramid records 2008)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a new grass sprouts and it could help control flooding. Stay tuned for more of Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Duke Ellington: “Take The A Train” from Ellington Uptown (Columbia Records 1951) (Happy Birthday Duke 04/29/1899)]

Climate Change and Land Slides in the Northwest

BNSF Railway has had 200 landslides on or near its tracks this season, making it one of the worst since the company began keeping records in 1914. (Ashley Ahearn)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Much of the Pacific Northwest was once a large temperate rainforest, and there is still plenty of rain around, as Seattle area residents know all too well. And as the planet becomes warmer, there's expected to be even more intense rain.

One consequence may well be more mudslides. A spectacular slide recently took out a home and threatened dozens of others on an exclusive island in Puget Sound. But less dramatic and far more regular slides are now plaguing passenger and freight rail service.

Over the past winter BNSF, the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway has had 200 landslides on or near its tracks making it one of the worst seasons since the company began keeping records in 1914. Ashley Ahearn of the public media collaborative EarthFix has our story.

[OCEAN WAVES LAPPING]

AHEARN: One of the busiest stretches of railway in Washington State runs along the shores of Puget Sound between Seattle and Everett. It’s also one of the most high-risk corridors for landslides. Every day about 40 trains full of freight or passengers travel these tracks, en route from Seattle and points south toward Canada. But for the moment, anyway, you won’t hear any approaching trains, just some sea lions bantering offshore and some men in orange vests operating heavy machinery a little ways down the track.

[DIESEL MOTORS]

MELONAS: We're out here as you can see. We have a ditcher, front-end loader-dozer right now removing the debris.

AHEARN: Gus Melonas is spokesman for BNSF Railway. Behind where he's standing, a massive truck overflowing with exposed tree roots and mounds of earth rolls past, clearing the tracks after a recent landslide. Melonas says this has been a bad year for slides.

MELONAS: This would rate right at the top – definitely top five as far as slide after slide – some feel top three.

AHEARN: That’s top three worst years for landslides in BNSF’s recorded history. The company has been keeping a tally since 1914. Landslides are caused by a lot of different things: increases in housing development on bluffs, changes in vegetation. But ultimately...

GODT: ...what causes a landslide is ultimately gravity.

AHEARN: That's Jonathan Godt. He's a scientist with the US Geological Survey and has studied landslides in Western Washington.

GODT: So you’ve got a steep slope and gravity wants to pull everything down and then when water infiltrates into the soil it changes the stress of the soil.

Trucks clear away debris after a recent landslide shut down rail traffic near Everett. (Ashley Ahearn)

AHEARN: That’s right, water stresses out soil. It pushes the particles apart, weakening the composition of say, a bluff overlooking Puget Sound, and making the soil heavier with moisture. Climate change experts predict that in the Northwest we could see more precipitation overall, with heavier downpours and storm events. In Washington, the average annual precipitation has increased by about a third of an inch each decade since the beginning of the 20th century. And this winter saw above average rainfall in the north Puget Sound. That’s where BNSF says 95 percent of its landslide problems have occurred.

WHITELY-BINDER: That has certainly arisen as a very prominent issue and one in which there is a very clear climate connection.

AHEARN: That's Lara Whitely-Binder. She's with the Climate Impacts Group at the University of Washington. Whitely-Binder says that while you can loosely tie individual rain events to mudslides, there's no way to prove that climate change is to blame for this year’s bout of landslides. Landslides are nothing new for the Northwest. BNSF Railway has documented 900 slides on their tracks in the past 100 years. But Whitely-Binder says in the future there could be more wet winters like this past one.

WHITELY-BINDER: So moving forward through time, we are expecting to see more winter precipitation and more intense precipitation events, so we would anticipate seeing a greater risk of landslides moving forward in time.

AHEARN: The Washington State Department of Transportation had 55 rail cancelations due to mudslides in 2012. Carol Lee Roalkvam heads environmental policy at WSDOT. In 2011 she co-authored an assessment of WSDOT's vulnerability to climate change.

ROALKVAM: We’re aware now of more upriver flooding than we’ve seen in the past, more extreme rain events - the sudden and intense rain that we’ve been experiencing more frequently - so a lot of the state routes are vulnerable to landslides today and the projections are that those will be worse.

AHEARN: But Roalkvam says she’s confident that WSDOT has strategies in place to respond to the infrastructure risks posed by climate change.

ROALKVAM: I don’t think anyone can design themselves away from every single risk but I think we have a lot going for us here.

AHEARN: Gus Melonas with BNSF agrees that there are a lot of near-term engineering solutions for the railway.

MELONAS: We’ve made appropriate drainage, ditching, we’ve put up catchment walls, we've put up retaining walls, slide detection fences, the marine wall along Puget Sound, we've beefed it up.

AHEARN: Melonas added that the railroad has spent “millions and millions of dollars” on rail upkeep, but he could not give a specific figure. The federal government has provided $16 million to fund landslide reinforcement at six sites along this problematic stretch of railroad. Meanwhile, passenger rail traffic is on the rise and if a proposed coal export terminal is built near Bellingham, rail use could jump as much as 50 percent above existing traffic levels here. I'm Ashley Ahearn in Seattle.

CURWOOD: Our story on the land sliding away in Washington State comes to us from the public media collaborative EarthFix.

Related links:

- Earth Fix

- USGS on Landslides

- Report on Washington transportation disruptions from mudslides

[MUSIC: Fleetwood Mac “Landslide” from Rumors (Warner Bros. 1977)]

Flood Control With New Hybrid Grass

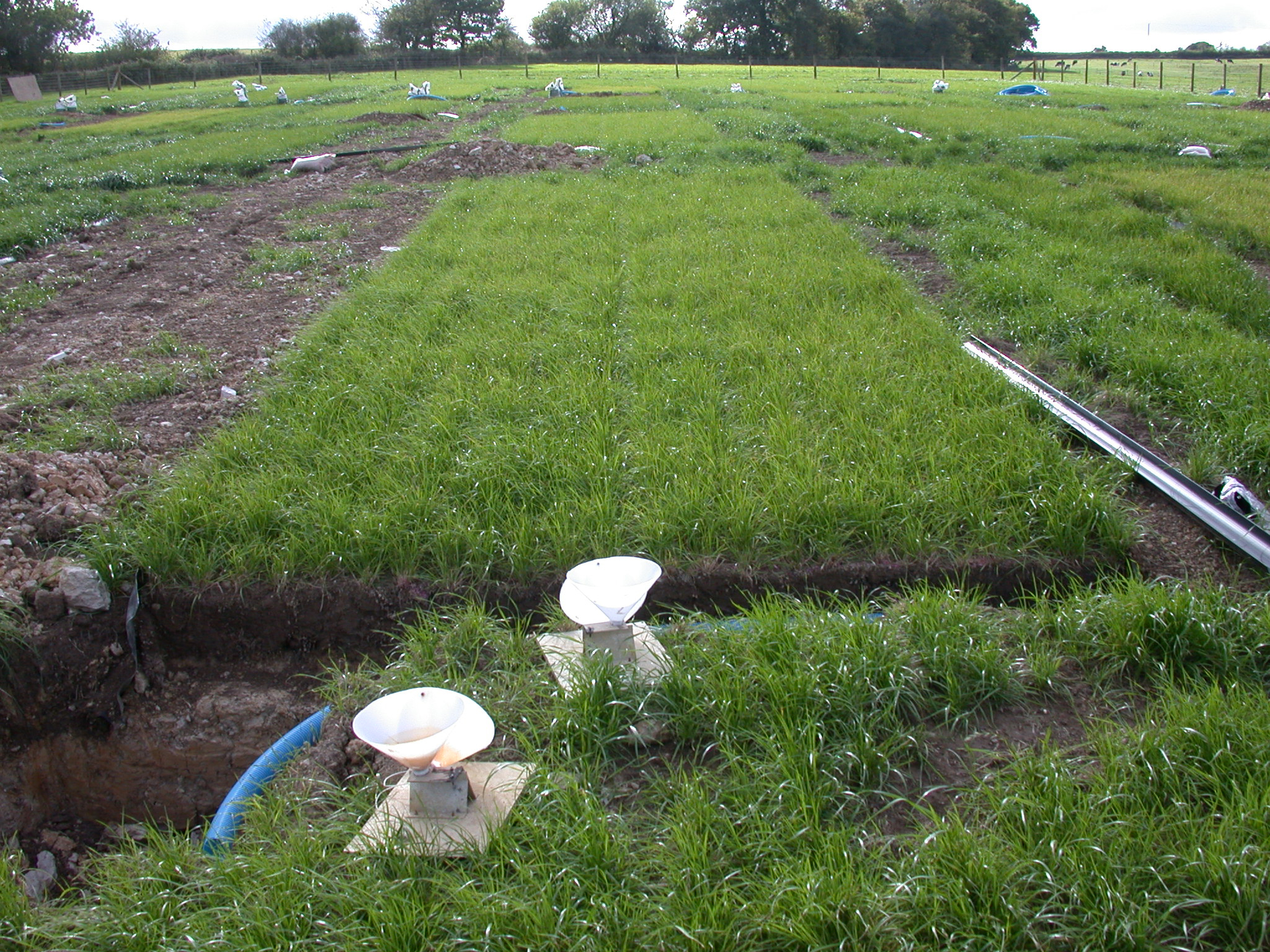

The rainfall-runoff plots were engineered so the scientists could collect the rainfall that moved laterally along the soil above and near the surface. There is little opportunity for water to percolate deep into the soil (photo: Kit Macleod)

CURWOOD: Now, if we're to cope with the increased rainfall and flooding of a warming climate, we'll need all the skills of our scientists. So, at the James Hutton Institute in Scotland, they've come up with one novel solution - a hybrid grass that could reduce runoff from pastures in much of the world. Kit Macleod is one of the researchers at the Hutton Institute, and he joins us now from near Aberdeen. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MACLEOD: Hi, thank you.

Kit Macleod (photo: The James Hutton Institute)

CURWOOD: So what exactly is this grass called, and what does it look like?

MACLEOD: Well, this grass is a hybrid between two grasses that are widely grown in the UK and other areas. The grass itself, called a festulolium, because one parent is a fescue and the other one is a lolium. It’s a forage grass that’s used in a lot of fields like people’s lawns. So green, maybe 10 centimeters long, depending on how it’s being cut or grazed. And it’s used for rearing cows and sheep primarily.

CURWOOD: By the way, for people who aren’t plant experts, what’s a hybrid?

MACLEOD: A hybrid is where we’ve bred a new sort of grass based on two distinct parent groups using traditional breeding techniques where it brings together traits from both of them.

CURWOOD: It’s not genetic engineering though.

MACLEOD: It’s not. It’s using traditional sort of cross breeding approaches.

CURWOOD: And the two parent groups are...?

MACLEOD: The perennial rye grass is widely used, the lolium. And then a meadow fescue, which is known not so much for production, but its known for having good rooting and a good sort of environmental stress tolerance.

CURWOOD: Now specifically, how does this work to blunt the effects of flooding?

MACLEOD: Well, in areas where we’ve got a lot of livestock in the UK, we’ve got quite poorly draining soils - clay rich - they’ve got little storage. So when it rains, the water runs off the farmers’ fields quite rapidly. So what we’ve found is that this grass, it certainly reduces the amount of water that was running off the fields. I think that’s due to the grass creating a more loose soil structure - basically more storage, more sponginess in these grass and fields due to the rooting of the grass - and the roots turning over and creating space and the wetting and the drying of the soil.

CURWOOD: So basically, it increases the capacity of the soil to store water then?

MACLEOD: Yes.

CURWOOD: So in your tests, how effective was this hybrid grass in reducing runoff from storms?

MACLEOD: Over a two-year period, when we had our experiment set up at the plot scales basically a patch of grass about 10-meters long to understand those processes. These grasses, for a number of rainfall events, reduced the runoff by 50 percent.

In addition to measuring runoff, the scientists collected data on the productivity of the grass for farming. Here is a picture of the small plot equipment to harvest the grass and weigh it automatically (photo: Kit Macleod)

CURWOOD: So what other uses would this hybrid have?

MACLEOD: Well, that’s one of the real drivers of the project. There’s a lot of interest in multifunctional land use. So it’s not only good for reducing runoff, but also good for production. Measured near the herbage in which it was being produced, it’s on par with the grass so the land is still productive, and providing an income for the farmer, but would also provide this wider environmental benefit.

CURWOOD: So, this isn’t something someone would want to use in the city to improve runoff, I take it.

MACLEOD: Potentially. We haven’t explored that. There’s a lot of interest in rain gardens and sustainable urban drainage systems. There’s potential there. You have the same processes; if you’ve got poorly draining soils, then it could. Then it’s a big issue. Cities like London, large amounts of people’s lawns are being turned into car parking spaces, and that changes how rapidly water moves off of the land into other people’s gardens or into rivers.

CURWOOD: I’m wondering where in the future might we see this grass in pastures around the world?

MACLEOD: Well, mainly, first of all, the seed companies need to carry out their trials and further develop these grasses before they are available to farmers. And the main market would be these sub-temperate areas where Lolium perenne - I’m not sure where it’s grown in North America - but it’s grown widely in the UK, parts of Europe and parts of Australia. Areas of similar bioclimatic conditions.

CURWOOD: How useful do you think your hybrid could be in flooding around the world?

MACLEOD: Well, I think it really depends on the context you’re applying it. We would hope with further research that within a certain grassland setting, that it would make some difference in how much runoff is being produced. Not for extreme events, and an extreme event with a large amount of precipitation, no matter what you do, changing runoff from land use is not going to be the big solution there. But hopefully, and overall, it would help slow the flow of the water coming down the catch basins. There’s a lot of interest in that at the moment.

CURWOOD: Kit, how comfy is it? Is it like lush? Would I want to lie down on it on a nice hot summer day with a good book? Or is it kind of spiky and scratchy?

The grass plots were grown from 2006 to 2009 and instrumented to automatically to measure the rainfall that came from the plots (photo: Kit McLeod)

MACLEOD: Oh, it’s lovely and lush. You know, sitting under a tree in the English countryside watching some baby walk past; sipping a pint of cider. It’s perfect for that.

CURWOOD: Kit Macleod is a scientist at the James Hutton Institute in Scotland. Thanks so much for joining us.

MACLEOD: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- James Hutton Institute website

- Kit Macleod’s staff page

- Hutton Institute press release about the hybrid grass

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy “Flood from Tell Your Friends (Ropeadope 2010)]

Robins on the Hunt-By Ear

CURWOOD: Now one of the other drivers of soil structure is the world of life under the grass - the many invertebrates that mostly we don't think about. But as the world starts to bloom, and breed, robins are busy listening for the sound of that world below. From the Western Soundscape Project, Jeff Rice listens in.

RICE: Take a listen to your lawn for a minute, just beneath the soil.

[SOUND OF MOVEMENT IN THE SOIL]

RICE: Those are earthworms.

MONTGOMERIE: The worms are moving through the soil and the little particles of sand are hitting against each other.

RICE: That's Dr. Bob Montgomerie of Queen's University in Canada. He made these recordings. Chances are you've never heard earthworms before.

MONTGOMERIE: No, they're extremely quiet. The only way we were able to record them was to put them in a chamber called an anechoic chamber and use a very high sensitivity directional microphone. One that would pick up a human's voice at a couple of hundred meters and pointing it right at the soil about centimeter from the worm.

RICE: So you might think that such a very, very quiet sound would be pretty insignificant. Hardly a sound at all really. But consider this. Next time you see a robin on your lawn...take a look at how it catches worms.

[ROBIN CHIRPS]

MONTGOMERIE: Well, way back into the 1800s, people writing about robins have thought that they were listening when they were foraging on lawns. You see a robin hopping along and then it cocks its head and lots of people, lots of naturalists have written popular articles saying that they were listening for worms.

RICE: Nothing was scientifically proven until several years ago when Dr. Montgomerie and a colleague were taking a break from their usual fieldwork -- Dr. Montgomerie studies, among other things, reproductive behavior in birds -- and they noticed robins cocking their heads toward the ground.

MONTGOMERIE: You know, it really looks like they're cocking their head and listening.

RICE: They decided to answer the question once and for all and devised a series of experiments.

MONTGOMERIE: Well, we caught a few robins. We were working on them anyway. We were studying the way that they look after their babies and choose mates. And so we grabbed a couple and put them in an outdoor aviary that we had at our field station. And then we designed a careful experimental protocol to try to eliminate each of the sensory modes in order.

RICE: They tested everything short of robin ESP. They hid worms behind barriers. Eliminated the possibilities of smell and touch. But just based on hearing, robins...

MONTGOMERIE: Found the worms with no problem.

RICE: The two scientists published their findings in the journal Animal Behavior. Just how a robin is able to hear something as quiet as an earthworm is still unknown, but they are not the only birds that can locate food this way. Magpies are also known to locate scarab beetle grubs in the ground through hearing. For Living on Earth, I'm Jeff Rice.

[MUSIC: Jimmy McGriff “The Worm” from The Worm (Blue Note Records 2002)]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week deep within South Africa's Madikwe Game Reserve.

[MUSIC: John Bullitt “Mandikwe game Reserve” from Night Of A Thousand Songs (Akalitko records 2008)]

[FROGS CALLING AND CRICKETS BUZZING]

CURWOOD: During the day, elephants, giraffes, lions and warthogs come to drink at the Inkwe Pan water hole, but at night it comes alive with a chorus of male kassina frogs, and crickets.

[TOADS CROAKING]

The raucous toads - Bufo Rangeri - join the night chorus, as all of the creatures seek romance in the African night. John Bullitt recorded these musical insects and amphibians for his CD Night of a Thousand Songs.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Alicia Juang, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. And we bid a grateful farewell to Qainat Khan, and wish her much success. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth