June 7, 2013

Air Date: June 7, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

British Columbia Rejects Tar Sands Pipeline

View the page for this story

With the Keystone XL Pipeline decision still up in the air, Canada is looking for alternative export routes for Tar Sands oil. But as Danielle Droitsch of the Natural Resource Defense Council's Canada Project tells host Steve Curwood, British Columbia has rejected a proposal to send a pipeline through their pristine Province. (05:40)

Legal Battle Over Drilling Pollution in the Amazon

View the page for this story

In a case that dates back two decades indigenous groups and subsistence farmers successfully sued oil giant Texaco (now merged with Chevron) for polluting an area the size of Rhode Island in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Chevron media advisor, Jim Craig, claims the trial was a fraud and the company shouldn’t have to pay the $19 billion awarded as damages. So Juan Pablo Saenz, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, says they are now going after Chevron’s assets in countries other than Ecuador. Both guests explain their positions to host Steve Curwood. (08:45)

Love That Dirty Water, Swimming in Boston’s Charles River

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Boston’s Charles River was once so polluted with sewage, and industrial waste that people who accidentally fell in were advised to get a tetanus shot. Now, after decades of cleanup, the river is host to an annual swim. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports. (09:05)

California’s Fish in Trouble

View the page for this story

Many of the fish that swim in California’s rivers can be found nowhere else in the world. But as fish biologist Peter Moyle tells host Steve Curwood, some of those unique species may be in trouble and threatened with extinction. (06:30)

South African Tea Farmers Adapt to Changing Climate

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

Rooibos or red bush tea is grown only in the western part of South Africa in the Succulent Karoo, an area with a unique climate and ecosystem. But as climate change starts to make farming more unpredictable, scientists are working with farmers in the region to help them adapt their traditional farming practices to what lies ahead. Living on Earth host Steve Curwood reports. (17:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Danielle Droitsch, Juan Pablo Saenz, James Craig, Peter Moyle

Reporters: Bobby Bascomb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. British Columbia says "no" to a pipeline to move tar sands oil to the Canadian west coast for export. Authorities there say it's just too risky.

DROITSCH: Tar sands oil is very different than conventional oil. Keep in mind that it's solid in its natural state, it actually has to be mixed with chemicals to push it through a pipeline, so this actually poses much greater threats to water.

CURWOOD: Also, what's happened to the dirty water in Boston's Charles River.

HAMLIN: Everyone understood the river was dirty and if you had an open cut or something like that you really tried to avoid getting your hands in the water. And of course, the joke back in our day was that if you fell in you had to go immediately to Stillman infirmary to get a tetanus shot but that’s no longer the case.

CURWOOD: No indeed. Nowadays the Charles is so clean you can swim in it! That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic smoothies, yogurt, and more.

British Columbia Rejects Tar Sands Pipeline

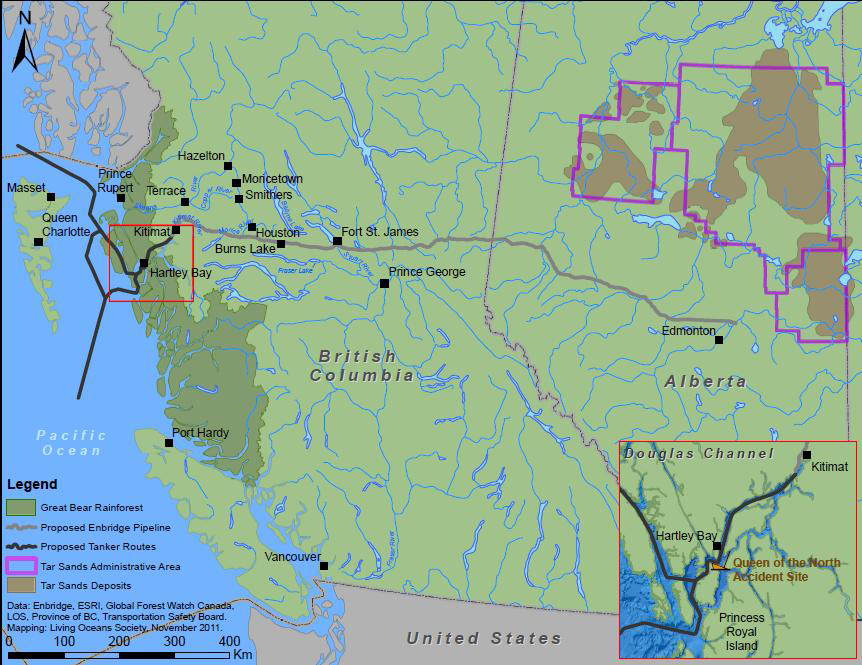

Map of the proposed pipeline route through British Columbia (photo: Natural Resource Defense Council)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The Canadian west coast province of British Columbia has rejected a proposed pipeline to bring tar sands oil to its ports. The decision likely means more troubles for the proposed and hotly debated Keystone XL pipeline through the US to Texas refineries. Activists are fighting hard against Keystone XL, arguing it would aggravate global warming - though the US State Department claims that with or without Keystone, the tar sands oil will be exported. But Danielle Droitsch, head of the Natural Resource Defense Council’s Canada Project, says the British Columbia decision changes the game.

DROITSCH: Basically, the British Columbia government said "no" to moving half a million barrels a day across 600 miles across rugged and pristine areas of British Columbia. And they did that because of the risk of spills to that pristine environment, the risk to the commercial salmon fishery and the risk to human health.

Danielle Droitsch (photo: Natural Resource Defense Council)

CURWOOD: What's different about tar sands oil than regular oil?

DROITSCH: Well, that’s one of the things that the British Columbia government pointed out and it's a lesson we can certainly take from the Keystone XL tar sands pipeline - which is that essentially tar sands oil is very different than conventional oil. Keep in mind that it’s solid in its natural state. It actually has to be mixed with chemicals to push it through a pipeline. So this actually poses much greater threats to water.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about Canadian politics. How important is it for the province to make this ruling on a matter like this. I mean, what power does the central government, does the federal government going to have to overrule the province here?

DROITSCH: The decision to approve pipelines is the jurisdiction of the federal government. So the federal government could go ahead and ignore what the province has said and approve the pipeline, but there are a number of risks in doing that. 60 percent of British Colombians are opposed to the tar sands pipeline that has just been rejected. It would be very unusual for the federal government to ignore the province.

CURWOOD: Now British Columbia has many indigenous groups, many First Nations, that have treaties. What say do those First Nations have on the pipeline coming through?

River in Vancouver, British Columbia. The proposed pipeline would have to cross over 700 rivers and streams to reach the coast. (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

DROITSCH: Well, the issue of First Nations and this tar sands pipeline is actually quite significant. There are over 70 First Nation communities that are along the pipeline’s path and every single one of them are opposed to this project. The federal government could overrule the provincial government, but they don't legally have the ability to overrule the opposition of 70 First Nations. And that's really where a lot of financial analysts are basically acknowledging that because there are 70 First Nation communities with legal constitutional rights to stop the project, they’re basically saying this project is not likely to move ahead at all.

CURWOOD: Apart from Keystone, what are the other alternative pipeline and rail projects that could bring tar sands oil to international ports?

DROITSCH: They are now looking at routes to the east. They've actually even floated ideas to go up to the Arctic which seems a little crazy, but actually certainly is possible if they're that desperate. But really all those other projects have tremendous hurdles; there's either significant Canadian opposition, there’s First Nations opposition, it’s economically not feasible, and that is why Keystone XL has become a focal point for the industry so that they can pursue a massive expansion plan.

CURWOOD: Now the United States State Department said in their recent report that if Keystone doesn't get built that tar sands is going to market anyway. What impact do you think British Columbia government decision has on that argument?

DROITSCH: The decision by the British Columbia government should force the State Department to completely revisit its conclusion that tar sands development will happen anyway. It really illustrates that tar sands development is not inevitable. The tar sands industry will not be able to get its product to Asian markets through the Canadian lands. They’re planning...the tar sands industry is planning to get its product through the United States to international markets. Keep in mind that Keystone XL is not a pipeline to America - it’s a pipeline through America.

CURWOOD: In the wake of this decision by British Columbia where do you see this all headed?

DROITSCH: Well I think we basically are looking at unfolding developments every month that demonstrate in both the United States and in Canada that there’s more awareness; that tar sands and tar sands pipelines pose particular unique and greater risks to the environment. Historically a lot of people thought that this was really the same thing as conventional oil, and that there really hasn't been a problem. But the more we learn, the more we realize that this particular type of oil is actually something that is not great for water, it certainly isn't good for climate, and it's not something that most people are wanting to go through their communities.

CURWOOD: Danielle Droitsch is head of the Natural Resource Defense Council’s Canada Project. Thanks for taking the time with me today.

DROITSCH: Well thanks for having me.

Related links:

- BC Government Report on Enbridge Pipeline

- NRDC report on Enbridge pipeline in BC

Legal Battle Over Drilling Pollution in the Amazon

A boy stands on an oil pipeline in the Ecuadorian Amazon near the town of Lago Agrio. (Lou Dematteis and Kayana Szymczak)

CURWOOD: Meanwhile, at its recent annual meeting, the oil giant Chevron was once again pressured by nearly a third of its shareholders regarding widespread contamination of water and soil in Ecuador that dates back to the 1960s. Texaco drilled in Ecuador, then later merged with Chevron. After more than 20 years of litigation, the combined company has been ordered to pay $19 billion in damages. Chevron claims it has been unfairly treated and has refused to pay, so the plaintiffs are going after Chevron assets in other countries including Argentina. Juan Pablo Saenz is an Ecuadorian lawyer for the plaintiffs. He says the area contaminated by the drilling decades ago is still unsafe and unpleasant for the people living there.

A local woman walks out of a cemetery where her father, brother and sister are buried. All of them died of cancer. (Lou Dematteis)

SAENZ: Well, it smells just like a gas station. Previously where you would have rivers and lakes where indigenous groups would fish - now they’re devoid of any animal life. Those indigenous groups now they need to eat canned tuna and stuff like that. There’s this thing that oil companies used to do. They used to pour oil on the dirt roads - I don’t know exactly what their justification for that is - and it’s these roads that people have to walk back and forth to work every day. And you hear stories all the time that they were walking those roads in flipflops and they would get stuck to the road so they would have to walk barefoot. It’s just all those little things that explains it’s important how pervasive all this...living in this area was, and how pervasive the oil problem is through the area.

CURWOOD: How large is the area that’s affected?

SAENZ: It’s contained within two provinces in northern Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest about the size of the state of Rhode Island.

Oil contaminates open pits in the Ecuadorian Amazon. (Rainforest Action Network)

CURWOOD: And how much oil was spilled there?

SAENZ: Actually what caused the most damage to the area were about 16 billion gallons of toxic produced water that were pumped directly to the waterways, and that were pumped directly to the rivers. Also, you have there about 1,000 open air pits - they just dug them directly into the soil with no lining so actually there was ways for contaminants that managed to flow into nature and from them into animals and then into human beings.

An unlined oil pit in the Ecuadorian Amazon. (Lou Dematteis and Kayana Szymczak)

CURWOOD: Now the residents in the area say they have a lot of health problems associated with with living with toxicity of the oil-related water pollution. Tell me about that please.

SAENZ: That’s probably the hardest part about all this - just the human suffering. Cancer rates are 150 percent higher than one would expect from this sort of environment. There’s a lot of child leukemia. There’s a lot of ovary cancers and general reproductive health problems for women, miscarriages. This is made worse because these people have no access to real healthcare. They don’t have access to clean drinking water, you know?

Residents in the affected area still use the contaminated river for swimming and drinking water. (Rainforest Action Network)

CURWOOD: How did this area get to be so pollluted? I mean, drilling for oil can result in occasional spills, but this sounds far more reaching than a spill or two.

SAENZ: This was designed to pollute. When Texaco - that’s Chevron’s predecessor - when Texaco came into Ecuador they promised that they could extract the cheapest oil barrel in the world. And that’s precisely what they did. How they did that was designing this operation with utter disregard for human life and only considering maximizing economic gains. When they had technology, for instance, to reinject some of the toxics to levels where they wouldn’t do any harm to nature or to human life, they just made a cost-benefit analysis and they simply chose not to.

A photograph of Texaco’s work to remediate oil contamination in an open pit. (Chevron Corporation)

CURWOOD: Just remind us of how Chevron got into this case, because it was filed 20 years ago against Texaco.

SAENZ: Sure. Texaco basically merged with Chevron between 2001 and 2002. Basically what they did was they got merged. At the beginning it was called Chevron-Texaco company but once they figured out that didn’t look good for Chevron because of Texaco’s previous environmental record, they just dropped the Texaco portion altogether. They’re hiding behind lots of subsidiaries, lots of complicated structures to try and hide responsibility, to try and hide behind a corporate veil.

CURWOOD: So this case has been going on a long time. Just what exactly happened here?

Texaco workers washing oil off debris. (Chevron Corporation)

SAENZ: At first, we filed suit in New York originally - the federal courts in New York. Chevron fought us for ten years arguing that it was the Ecuadorian courts that were supposed to handle this case. The court actually agreed to do that, but made them promise that Chevron would abide to any decision coming from the Ecuadorian courts. So we go back to Ecuador because back then Chevron was real chummy and had a big influence with the government, and they thought that this would get resolved over a game of golf. So we come back to Ecuador, we spend ten years litigating. We win the trial. We win on appeals, but right now they are refusing to pay. And that forces us to basically make a list of countries where Chevron holds assets because they do not in Ecuador. And right now we’re in the process of trying to collect the damages in other jurisdictions.

CURWOOD: Have any of these other nations taken action on your request?

SAENZ: Yes, for instance in Argentina, we asked there for the assets to be frozen and they did it. This money that normally flows from Chevron’s Argentinian’s subsidiaries to Chevron’s headquarters in the U.S. - all that money is set aside in an escrow account.

CURWOOD: So what’s next in this case? We will keep on vigorously fighting and defending these actions in Canada and Brazil and Argentina. We will be starting new enforcement actions in other jurisdictions, but what’s coming soon is that hopefully we will be able to start with the remediation of the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. And that cannot happen soon enough.

CURWOOD: Juan Pablo Saenz is an Ecuadorian lawyer in Quito representing the plaintiffs in the Chevron-Texaco case. Thank you so much.

SAENZ: Thank you, Steve, it was a pleasure.

CURWOOD: To hear Chevron's side of the story we called up Jim Craig. He's a media advisor for the Chevron corporation.

CRAIG: The plaintiffs’ lawyers in the case bribed, defrauded, and colluded their way to a $19 billion judgment against Chevron in Ecuador. There’s no reason why one would have to accept a judgement based on this sort of corruption and wrongdoing.

CURWOOD: What about the substance of the disagreement here? In your view, is Texaco responsible in any way for the pollution that has been observed in the area in question?

CRAIG: No, any pollution or contamination that may exist today is not the responsibility of Texaco. Texaco did a complete remediation in the 1990s. It received a release from the Ecuadorian government and the Ecuadorian state oil company PetroEcuador, who was Texaco’s majority partner at the time. The company that didn’t do their share of remediation was PetroEcuador. PetroEcuador agreed to and had an obligation under contract and the law to remediate its two-thirds share of any impacted site. They didn’t do so for almost two decades. They operated exclusively for 23 years with what everyone agrees is an abysmal environmental record. So if there’s any contamination today in the Amazon of Ecuador, it’s the responsibility of PetroEcuador.

CURWOOD: So you agree then that there were...there was a whole lot of pollution in that area?

CRAIG: I didn’t say that.

CURWOOD: Well, do you say that there wasn’t pollution in that area?

CRAIG: There were identified...a certain number of sites that needed remediation, but there isn’t the massive contamination that the plainiffs have continually insisted that there is. Texaco had an obligation to remediate it’s one-third share of sites. Those were identified in an audit and were the basis of an agreement which required Texaco to conduct its remediation.

CURWOOD: Has Texaco ever paid any damages to the communities that are the subject of its remediation activities?

CRAIG: Yes, it did. It conducted a remediation program for $40 million which included several million dollars to settle claims by the same communities that the plaintiff’s lawyers claim to represent.

CURWOOD: So Chevron paid how much to the communities?

SAENZ: Again, it wasn’t Chevron. It was Texaco. Six or seven million dollars, I believe.

CURWOOD: So your response to the people there that have health concerns, cancer, miscarriages and such is that take it up with PetroEcuador?

CRAIG: Well, look. I could say something about the health claims that you just mentioned. Official statistics show that the cancer mortality rates in the oil producing region are lower than both the capital Quito and the non-oil producing areas of the Amazon. You know, we have a lot of reason to believe that these supposed cancer claims are false. So again, if people really have claims to bring, they ought to bring them to the only company that’s responsible today for any problems that might exist in that region. That’s PetroEcuador.

CURWOOD: James Craig is a spokesperson for Chevron. Thank you so much for taking the time, Jim.

CRAIG: Sure thing.

Related links:

- Amazon Watch

- Chevron on the lawsuit in Ecuador

[MUSIC: Daft Punk “Motherboard” from Random Access Memories (Columbia Records 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...clean up efforts pay off -- at least for some of American's once filthy rivers. That's just ahead here on Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Monty Alexander: Sneaky Steppers” from Yard Movement (Island Records 1996) Happy Birthday Monty Alexander 06/06/1944]

Love That Dirty Water, Swimming in Boston’s Charles River

Swimmers returning to the dock (Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The Charles River meanders for 80 miles through eastern Massachusetts on its way down past Harvard, BU, MIT to the Boston Harbor. King Charles I of England named it after himself when it was first explored by the British back in the 17th century, yet by the 19th century the Charles had become a dumping ground for sewage and industrial waste. But now as summer begins, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports the Charles is not only cleaner, for some folks it also means a lot of fun.

[SPLASHES]

The Charles River. (Photo Alicia Juang)

BASCOMB: It’s a hot sunny June morning on the Boston Esplanade. 150 swimmers in numbered yellow and orange caps tread water in the Charles River just in front of the Hatch Shell where the Boston Pops accompany the Fourth of July fireworks every year.

HESTER: Is everybody ready?

CROWD: Whoo! Yeah!

HESTER: I’m going to count down from 10 and then blow the whistle. That’s the start.

Swimmers getting ready to jump into the Charles. (Bobby Bascomb)

[COUNTING DOWN IN BACKGROUND]

BASCOMB: Swimmers had to sign up early to qualify and be able to swim a mile in less than 40 minutes. The Charles River Swimming Club organizes the race. They’ve held it for the last 8 years but it had to be cancelled three times because of unsafe algae levels after heavy rain.

[WHISTLE BLOWS]

BASCOMB: Franz Lawatez is president of the swimming club. He says opinions of the river tend to vary depending on age.

LAWATEZ: I think the younger generations are a little bit more open minded. They’ve seen people wind surfing on it. They’ve seen this swimming race for the last eight years or so. So I think there’s a bit more receptivity to the idea of getting in the water.

BASCOMB: There are still problems with urban runoff and many Bostonians remember what it used to be like.

[SONG: LOVE THAT DIRTY WATER BY THE STANDELLS]

LAWATEZ: The people that have known the river at its worst, which tends to be the older generations, they usually have a more reliably negative reaction because they’ve seen the river back in the day when it inspired that famous song, Love That Dirty Water.

[SONG: LOVE THAT DIRTY WATER BY THE STANDELLS]

Charlie Hamlin dips his oar into the Charles River. (Alicia Juang)

BASCOMB: In 1966, when the Standells were singing about Boston’s dirty water, Charlie Hamlin graduated from Harvard. He was a member of the university rowing team.

HAMLIN: Everyone understood the river was dirty and if you had an open cut or something like that you really tried to avoid getting your hands in the water.

BASCOMB: Today Hamlin is treasurer of the Cambridge Boat Club. We talked there on a cool morning just as boats full of rowers were heading out on the river to train.

Charlie Hamlin on the deck of the Cambridge Boat Club. (Alicia Juang)

HAMLIN: Of course, the joke back in our day was that if you accidentally fell in you had to go immediately to Stillman infirmary to get a tetanus shot but that’s no longer the case.

[WALKING]

BASCOMB: Charlie leads the way down a gravel path to the dock.

HAMLIN: I’ve got one of my sculling oars with a white blade on it and if I push it straight down it disappears about five feet into the water whereas back in the day if I only put it a foot under the water you wouldn’t be able to see it. It’s an indication of how much the water’s been cleaned up.

BASCOMB: The pollution on the Charles and many other urban rivers in the US started shortly after the first European settlers arrived, when they built mills on the river. Bill Walsh Ragalski is a lawyer for the Environmental Protection Agency. He says the mills weren’t the worst problem.

WALSH RAGALSKI: The real pollution began around 1840 when the public water supply was built in Boston because there was then indoor plumbing and most of the plumbing drained into the Charles. So there were high levels of sewage going into the Charles. It became worse in 1908 when the dam was built, what’s called the Old Dam, which turned the river, an estuary, into a lake so all of that sewage just stayed there as opposed to getting flushed in and out every day.

BASCOMB: Add blood and offal from five slaughter houses upstream to the raw sewage and you had a pretty foul mix. Later came a paint factory and weapons arsenal, and along with them pollutants like PCBs, copper and lead. Again, Bill Ragalski.

RAGALSKI: If you take a look at the distribution of contaminants in the sediments there are high lead levels under the bridges because until recently they just scraped the bridges to repaint them and of course there was lead in the paint.

BASCOMB: The US Geological Survey recently took core samples of sediments in the Charles. They found a spike in lead levels that correspond with the arrival of the automobile and a steady increase until unleaded gasoline was introduced.

Swimmers waiting for the whistle to mark the beginning of the race. (Bobby Bascomb)

RAGALSKI: The sediments in the Charles River is a history of the automobile in Boston in some respects.

BASCOMB: More than a century of pollution added up to a river so dirty that the idea of swimming in it was the subject of ridicule. In 1988, Boston comedian Mike McDonald offered sunbathers on the river bank $10 to go for a swim.

MCDONALD: Would you consider swimming?

MAN: No, never.

MCDONALD: Not even for money?

MAN: No.

MCDONALD: Why wouldn’t you swim in this river?

MAN: It’s disgusting, it’s polluted. It’s like swimming in a toilet. It’s worse.

MCDONALD: Would you swim in the Charles for 10 bucks?

WOMAN: Uh...I think perhaps not.

MCDONALD: What isn’t attractive to you about that?

WOMAN: I’m not interested in motor oil floating, oil slicks and things like that, you know.

MCDONALD: Do you believe the river is polluted?

MAN: I know it’s polluted.

MCDONALD: With what?

MAN: Pollutants

[LAUGHING]

Swimmers taking off on a mile long swim in the Charles River (Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: The Clean Water Act in 1972 marked the beginning of a turnaround for the Charles and urban rivers across the country. It was a long road to recovery but for the first time, industrial and municipal discharge into rivers was regulated. Today, after decades of clean up efforts, the Charles is a model for river rehabilitation. In 2011, the Charles beat out 146 applicants from 21 countries to win the prestigious International Rivers Prize.

ZIMMERMAN: It’s sort of the academy award for river groups world wide. It brought with it a $330,000 first place prize.

BASCOMB: Bob Zimmerman is the Executive Director of the Charles River Watershed Association. His organization has been working to clean up the Charles since 1965 and received the award. Zimmerman says the Charles is now clean enough for fish to thrive.

ZIMMERMAN: The department of marine fisheries and department of fish and game have been restocking the river; we have one of the better herring runs on the east coast.

BASCOMB: In 2012, a fisherman spotted a sturgeon in the Charles. It’s an ancient fish that predates the dinosaurs but hasn’t been seen here in living memory. Generally, urban rivers across the country are cleaner now than they have been for generations. And, says Amy Kober of American Rivers, public enthusiasm for outdoor recreation is on the rise, creating an unprecedented interest in swimming in urban rivers.

KOBER: We are seeing more and more swimming in rivers that used to be polluted. Places like Washington, DC, the Potomac River is home of the nation’s triathlon. The Willimette River in Portland, Oregon. There are a number of swims on the Hudson in New York, there’s a triathlon on the Ohio River, there’s a swim on the Beaufort River in South Carolina, the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest. So, really all around the country people are using the rivers in that kind of way.

BASCOMB: Back at the Charles the first swimmers are returning to the dock.

[CHEERING, SWIMMING SOUNDS]

OLDER MAN: How’s the water taste?

YOUNGER MAN: Not that bad, I’m trying not to swallow it!

BASCOMB: Swimmer Nick Hill says he trusts the EPA when it says the water is safe for swimming still…

HILL: I probably swallowed between half a cup and a cup so I hope it’s safe. They had some environmentalists say it was safe for swimming. They didn’t say it was safe for drinking. But I have a decent immune system. I’m confident I will survive.

BASCOMB: What made you decide to want to do this race at all?

HILL: This looked like it would be a fun thing, a challenge. It was. And it’s kind of bragging rights. Everyone says, “you swam in the Charles?!”

BASCOMB: John Wilkinson won the race in just over 22 minutes.

WILKINSON: I love the location, it’s so cool being right in the middle of a city doing a swim race. And the water really is clean. I know years ago it had a bad reputation. It’s amazing how far rivers like the Charles and the Hudson have come. There are tons of races in those water bodies now and it’s a testament to all the work that’s been done to clean up our rivers.

BASCOMB: EPA testing shows the Charles is actually safe for swimming roughly 60 percent of the year. But it’s virtually always closed - there’s no funding for lifeguards or public beaches. Still, in July the Charles River Conservancy will host its first ever public swim and all the groups working to clean up the river hope that in the future there will be more swims and maybe even clean safe public beaches. For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb beside Boston’s Charles River.

[MUSIC: The Standells “Dirty Water” from The Very Best Of The Standells (UMG Records 1998 reissue)]

California’s Fish in Trouble

Juvenille Coho Salmon, one of the most endangered fish species in California (photo: Caron Jeffres)

CURWOOD: As summer begins along many US rivers, you'll find anglers patiently contemplating their rods in the flowing water. But researchers say when it comes to California, in the future they may be out of luck if they are looking to hook an indigenous fish. A new study from the University of California at Davis finds that many of California’s unique fish species could go extinct if global warming continues at current rates. Peter Moyle, one of the lead authors on the study, joins us now from UC Davis. Welcome to Living on Earth, Peter.

MOYLE: Thank you very much!

CURWOOD: Now tell me why are freshwater fish particularly vulnerable to climate change?

Professor Peter Moyle, holding a Sacramento pikeminnow, one of California’s fish that is not threatened by climate change (photo: Jacob Katz)

MOYLE: Well, freshwater fish don’t have any place to escape climate change is one of the reasons. You know, when you’re in a stream, you can only go upstream so far before you run into a waterfall or something, so if the conditions in that stream change, you’re pretty much stuck. And that’s what’s going on in California and throughout the west especially. Streams are predicted to get a lot warmer, four to six degrees Fahrenheit, especially in late summer. And the stream flows are going to become more variable. So the fish are really going to be stressed as a result of climate change. And this will be a cumulative thing over the next 50 to 100 years.

CURWOOD: So how did you determine the vulnerability of freshwater fish? How do you quantify this?

MOYLE: Well, I’ve done periodic assessments of the California fish fauna - I did one in 1975, one in 1989, one in 1995 and now more recently. And this in turn allowed me - when I wanted to do a climate change assessment - to go through the literature and rate them on 20 different metrics in terms of their vulnerability in climate change. When we scored 121 native fishes and 43 non-native fishes, 82 percent of the native fishes are going to suffer heavily from climate change and many of them to the point where they’ll go extinct. Basically, many of the endangered fishes are already on a downward trajectory because of so many other things going on with California’s water and climate change adds that extra stress. It’s more likely to push them to extinction.

CURWOOD: You’re saying that 80 percent of endemic, that is native, freshwater fish in California, likely to go extinct - or close to extinct - because of what is happening to the climate?

MOYLE: That’s right.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the fish species that are the most vulnerable, and the ones that were surprises for you as well.

MOYLE: Well, the fish that are most vulnerable are those that require cold water. Those fishes include very distinctive populations and runs of Chinook salmon, Coho salmon, Steelhead trout, as well as species like Delta Smelt and Eulachon. These are the species that require cold water, and many of these rivers are simply going to get too warm for them.

Endangered chinook salmon, in California’s Central Valley (photo: Alan Harthorne)

CURWOOD: Now, what about the non-native fish? Your report said they are going to do a lot better. Why?

MOYLE: Well, basically when people...Europeans, I should say, came to California in the 19th century, they decided native California fish fauna wasn’t good enough for them. So they brought in all kinds of non-native fish, especially those that can do well in reservoirs and in really warm water habitats. Because we’ve been essentially changing things in California ever since the Gold Rush and generally creating warmer water habitats anyway. So you’re bring in your catfish, your bass, your carp - species that thrive in warm water environments. And essentially, we’re creating more of those environments with climate change. So these species are just going to thrive and then that provides an additional stress factor on the native fish because there is competition between native and non-native species. So as you make the environment become more favorable for the non-native species, they put additional pressure on the natives and help to accelerate their decline.

CURWOOD: So salmon, Steelhead trout, these are pretty tasty fish. What impact might this have on the California economy?

MOYLE: Well, when you talk about the California economy, you always find that, fisheries, especially for salmon, are a tiny fraction of any economy. We’re not like Washington or Oregon that have a major part of their economy driven by these fisheries. But the important thing is that our fisheries will decline, and to the great distress of the fishermen unless we work hard to reverse the trend.

CURWOOD: What will it do for nature around these streams and lakes to lose these fish?

MOYLE: Well, salmon, of course, are a species which comes up from the ocean in large numbers and die in streams where they’re spawning. This provides a big influx of nutrients for the fish, and for the invertebrates and for everything else around these streams. I did a study once relating what salmon nutrients do to a steam surrounded by vineyards. And we found that not only did local wildlife benefit from salmon, we even got photographs of deer coming to munch on salmon carcasses, what we found was that the vineyards alongside the stream actually incorporated marine nutrients into the leaves of the grapes. The Caspian grapes were partially being fertilized by salmon. So there’s a real benefit in that regard to wildlife and even to farming from having salmon coming upstream.

CURWOOD: So what can we do to save California’s fish?

MOYLE: Well, the biggest single thing you can do in California from a water management point of view is to re-upgrade our dams. We have roughly 1,500 really large dams in the state and another couple thousand that are smaller. Most of these dams do not release enough water below them. The way you release water is you have to maintain your cold water pool in the reservoirs because in reservoirs water stratifies. It flows into the reservoir in the winter when the water’s cold. The cold water sinks to the bottom, and then you get this surface water that’s really warm. But most reservoirs can release water from the bottom. When they do that, you’re releasing the cold water that native fishes like salmon really like. So you have to conserve that cold water and use it specifically for fish as long as you can during the summer months. So we know there’s lots of things we can do. But it takes some fairly sophisticated management of our dams and rivers to make these things happen.

CURWOOD: Peter Moyle is a professor of fish biology at UC Davis. Thanks so much for joining us.

MOYLE: You're very welcome.

Related link:

Check out Peter Moyle’s webpage at UC Davis

[MUSIC: Steve Earle “Pocket Full Of Rain” from The Lost Highway (New West Records 2013)

CURWOOD: Coming up...the changing climate and its effects on one of life's essential pleasures - a nice cup of tea. That's next on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Steve Cropper: “Help Me Somebody” from Dedicated – A Salute To The 5 Royales (Stax Records 2011)]

South African Tea Farmers Adapt to Changing Climate

Rooibos tea farmer Koos Koopman holds up one of the bags the collective uses to ship Fair Trade organic rooibos tea. (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. As science was predicting more weather extremes linked to climate change, a group of researchers in South Africa began working with farmers to see if traditional methods might provide resilience for agriculture. Nearly a decade ago, Living on Earth's Eileen Bolinsky and I visited South Africa’s Succulent Karoo, to discover how this unique agricultural area was faring as climate change began to bite.

[WILDLIFE SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: It’s daybreak in the far southwestern corner of Africa, a few hours drive north of the Cape of Good Hope. We’re in the wild lands and farming country known as the Succulent Karoo. The broad plateaus look like a desert dotted with shrubs called fynbos, vast and bland except when early spring rains ignite blooms of wildflowers. Like other parts of South Africa, there are many plants here found nowhere else in the world, and with its biting winters and scorching summers, the semi-arid Karoo has a radically different climate from much of the rest of the country. Its unique location and size have attracted scientists looking for evidence of the local impact of global climate change.

[TRACTOR]

CURWOOD: Farmers here grow grains like oats and barley, and raise sheep. This is also the only place where the famous South African rooibos or red bush tea grows. This woody shrub looks much like the many other Fynbos bushes, though a closer look reveals shiny dark green leaves shaped much like the herb rosemary. Traditionally the Khoisan or Bushmen brewed a bright reddish-orange tea from the rooibos leaves. Now, thanks to smooth taste of the tea and its reputation as a promoter of health, the cultivation of rooibos is the biggest cash crop for many farmers here, including Koos Koopman.

[TRACTOR COMES TO A HALT]

KOOS: I grow rooibos tea, and then I make a little bit of small fruits, a little bit of vegetables in the garden...potatoes, carrots, cabbages, oranges, guavas. I don’t plant vegetables for marketing. I want to do it, but I haven’t got enough money yet to do that.

Farmer Koos Koopman in his rooibos tea fields.(Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

CURWOOD: Koos Koopman grew up on this land as the son of a colored farm hand. In the days of apartheid, “colored” was a distinct classification, different from white or black African. Koos’s bronze skin, almond shaped eyes and wiry build suggest that he may well have some Khoisan ancestors. He moved away to the city of Cape Town for three decades, but a few years ago after the end of apartheid he came back to the area. By then he and his brother Barry were in their fifties. They used government assistance to purchase this farm of more than ten square miles from the white farmer who had once employed Koos and his father.

KOOS: I was always thinking of this farm. And so about two years back, I come here one day and he tell me that they got problems. As we sit here in front of the house he ask me, Koos, I want to sell this farm now and I want you to buy this farm.

CURWOOD: So you’re all in this together, this is a family farm?

KOOS: It’s a family farm. Can we go to there…I want to see my…I want to make some soup for us, for lunch time.

[CONVERSATION WHILE WALKING]

KOOS: You know that’s the way I grow up…with my pots on the outside. We bake our own bread, we make everything for ourselves, you know. We try to purchase as little as possible from the shops. And that’s the only way you can survive on the farm.

[CONVERSATION WHILE COOKING. BUBBLING SOUP, STIRRING]

Mariette van Wyk (Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

CURWOOD: Saving money is especially important when you have a new and high mortgage on your farm. And during the drought of 2003 things were very difficult for Koos - forty to seventy percent of his rooibos plantings withered and died. Cultivated rooibos is his biggest source of cash, but there was a tiny bright spot: during the drought the wild rooibos plants scattered among the brush on his land seemed to hold their own. Like every farmer, Koos knows there can be bad years, but he does feel that the seasons are becoming less predictable. I asked him how they are changing.

KOOS: Sometimes very hot. Sometimes, very cold. I’m not talking about the rain. Cold, and then…snow, like a lot of snow, and it is dry and it burns the plants. And some of the things…when it is wet and the rain fall and it is very cold in the evening, and during the day it gets very hot.

[LAMBS AND SHEEP BLEATING]

CURWOOD: A few kilometers closer to town in Nieuwoudtville, the family of Mariette and Willem van Wyk has been farming for six generations since their ancestors came from the Netherlands.

[INDOOR ATMOSPHERE, TEA POURING]

CURWOOD: Mariette van Wyk pours me a cup of the naturally caffeine free rooibos tea and tells me that their operation has also been hit hard by the drought of 2003.

VAN WYK: Well, for the past ten years we couldn't complain and then last year came as a total surprise, being so dry. We had one major rain but everything failed.

CURWOOD: Usually they harvest 40 tons of rooibos a year. In 2003, 80 percent of the crop failed. And when it became clear that the magnificent display of spring flowers was also not going to happen, it meant the tourists didn’t come to the bed and breakfast the van Wyks have run for almost two decades. And with nothing growing for forage they could not afford much in the way of rations for their flock of 2000 sheep. Parsing out what little grain they did have to the sheep and recently born lambs proved to be a heartbreaker for Mariette.

VAN WYK: When they see the bakkie or the pickup coming they all run to that because they know it's food. In the commotion every mother loses her lamb. So every morning you will find, umm, 20, maybe less--hopefully less, sheep or little lambs dead around the... And the first time my husband took me out with him I felt like crawling under the bed when I came back, I just couldn't handle all those little dead bodies lying there. If we have good rains for the next two years we hope to recover, umm, in about two to three years.

CURWOOD: So let me ask you this: how much does it seem that the weather is outside the normal range of what it seems to have been all the years that your family has been farming here?

VAN WYK: Um, I am always careful to, ah, say this: people are talking a lot about they don't understand the weather any longer. And it's happening later and later that the winter clothes are coming out.

[BUMPING ON THE ROAD IN A NOISY TRUCK]

CURWOOD: On the road along the front of the Suid Bokkeveld Mountains into the town center of Nieuwoudtville rows of cultivated rooibos look dusty and dry in the heat of what locals say should be a cool early winter day. Signs that this could be more than just the odd dry spell have attracted the interest of scientists at the Climate Systems Analysis Group at the University of Cape Town. The science involved is complicated, but the general scientific consensus is that the Earth is warming because of the widespread burning of coal, oil and gas since the Industrial Revolution, as well as the cutting of vast amounts of forests. The El Niño weather pattern that seems to come more and more often with this warming tends to parch this corner of the planet.

ARCHER: One of the climate change projections is that there will be kind of a long term drying out or a reduction, for the broader area, not just for the Suid Bokkeveld but for interior South Africa.

CURWOOD: Dr. Emma Archer is a geographer with the Climate Systems Analysis Group.

ARCHER: A second one which is quite worrying is that there may be an increase in the frequency in what we call dry spells. So a period without rain, which is critical for agriculture, we may be getting more of those. And most importantly, the broad projection, and something which the World Meteorological Association actually put out a brief last year on which they agreed. Whereas people may have been receiving rainfall within a certain range, around a normal value, it seems as though that variability will increase, and so more extreme precipitation events will be experienced.

Dr. Emma Archer (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Emma Archer is in Nieuwoudtville to get the word out to local farmers that not only should they expect less rain, but they will also get it at different times than they are used to getting it, and it’s time to start planning how to adapt.

[WIND BLOWING]

CURWOOD: A few years ago a group of rooibos farmers in the Nieuwoudtville area organized themselves into the Heiveld Cooperative, with the help of the Environmental Monitoring Group, an advocacy agency. To boost income, they got their crop certified as organic and developed markets in Europe where the reputed health benefits of rooibos are prized. They are also working on strategies to cope with the effects of long term-drought. Noel Oettle is program manager for the Monitoring Group.

OETTLE: The farmers are quite aware that the climate is getting tougher, that's their perception, and the data is certainly supporting a trend towards drier and - and more extreme climatic events, and there are a number of ways in which they can adapt their practice towards production, which is less likely to be affected by climate.

Noel Oettle of the Environmental Monitoring Group

(Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

CURWOOD: Some growing techniques involve plowing in ways that conserve moisture, and using other plants to block winds that promote drying. And the experience of Koos and other farmers with drought tolerant wild rooibos is prompting some botanical research as to the feasibility of using the wild tea to help adapt to climate change. Rhoda Louw is a graduate student in botany at the University of Cape Town who is conducting a study with farmers of the Heiveld Cooperative.

LOUW: We’re looking at the sustainable harvesting of rooibos wild tea...

CURWOOD: Which is relatively slow-growing, but Rhoda is looking to see if farmers could gather enough of it to make it economically worthwhile.

LOUW: And we were particularly looking at the wild rooibos tea because it’s a strong source of income for the people in Suid Bokkeveld.

CURWOOD: There could be advantages. The cultivated tea that farmers use now can be harvested every year, but it has to be replanted every few years at considerable expense. The wild variety only needs to be carefully harvested by hand where it is found, although it can only be cut every two years.

A cultivated rooibos field, after harvest.

(Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

Rhoda and Emma want to take me on a tour of Rhoda’s experimental plots in Koos’s wild rooibos fields. But first, we decide to try a bit of research on our own: from the perspective of a consumer, me.

[TEA POURING WITH DOG BARKING IN BACKGROUND]

LOUW: Would you like some sugar with your tea?

CURWOOD: Oh no thank you, just a little bit of milk.

CURWOOD: If wild rooibos tea is to be successfully marketed it will need to stand up to the flavor of the popular cultivated rooibos. So Noel, Rhoda and Emma give me a taste test…

[STEVE SIPS THE TEA]

CURWOOD: OK. Mmmm, this is good.

[SETS DOWN CUP]

CURWOOD: This is outstanding.

NOEL: Steve, you get our "wildman from the North" award.

[LAUGHTER]

CURWOOD: The cultivated tea is delicious and the wild rooibos tastes great, with a sweet aftertaste like honey.

[KOOS CALLING AND FEEDING SHEEP]

Koos Koopman and his sheep (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: We’re back on the farm of Koos Koopman to see the wild tea plants that Rhoda Louw is studying. But before we head for the fields, Koos stops to tend his flock of sheep. In case of drought, he says he’s careful to limit the size of his flock; he wouldn’t want them to over-graze and clean out his wild rooibos. He’d like to sell the meat as organic but he’s not on the market yet. Still, he forgoes hormones and antibiotics in favor of traditional herbs to treat any illnesses in the flock. As we wait to drive into the fields, botanist Rhoda Louw explains how she will use the data about wild rooibos she’s gathering at the Koopman Farm.

LOUW: We’re trying to marry the scientific knowledge with the indigenous knowledge, which there is a great body of, and try to integrate that. The final product will not be just the thesis, but also a harvesting manual that will come out of the research based on the results.

Rhoda Louw (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: What are some of the indicators you are using for your study?

LOUW: One of the research questions is what is the difference between the wild tea and the cultivar. To measure that, we are looking at the life cycles of the two and comparing them over time. Another experiment is we are trying to see which harvest season gives you the greatest re-growth after a year.

[CAR DOWN SLAMS, DRIVES AWAY]

CURWOOD: Climate researcher Emma Archer, Rhoda, and Koos point out some planted tea fields, and various soil conditions, on our way to the wild rooibos. And Rhoda does a bit of translating as Koos slips into Afrikaans.

KOOPMAN [TRANSLATED BY LOUWS]: This is cultivated tea on both sides. This tea is about six years old. And if you look at this patch over here on my left, you’re going to get more moisture here than down below.

ARCHER: Koos is saying there is more rain here because it’s higher elevation.

CURWOOD: But it’s out of the vehicle to see the wild tea, and more than just a short hike.

[WALKING]

LOUW: I’m going to take you to some of the sites, to some of the samples in the experiments here…

CURWOOD: Rhoda has about 250 plants in her experiment. The tea bush branches are cut off by hand with a sickle, leaving enough behind so it can keep growing. Farmers already know that the planted or cultivated rooibos might produce for less than a decade. The wild bushes have a longer productive life - and can grow to be 50 years old. The wild tea is also more resistant to pests than its cultivated cousin, although the same pests go after both.

Rhoda Louw measures a rooibos bush.

(Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Can you move wild rooibos...can you move the plant and replant it?

KOOS: That is something I experienced at the moment. I’m busy with it, Rhoda and me, but it don’t work.

CURWOOD: As we walk through the brush we find the experimental plants, we see one that was harvested the previous year in April during and it’s almost dead. Others fared a bit better. And then we come upon a particularly robust rooibos plant, and Rhoda flashes a big smile.

LOUW: This is the July - one of the samples harvested from July.

CURWOOD: So, this is one of your more successful ones?

LOUW: From what I’m seeing, this is the most successful.

CURWOOD: What is the traditional time to cut this?

KOOS: The traditional time is any time from February to April. But look at those ones that were cut in January, February and into March. The experiments of that and the growing of that are much slower than the one of July. So, this is something that I’m working on. Maybe. But there’s one thing; you can’t dry the tea in July month because it needs sun and it is our rainy season -July. And we need sun, no rain, when we harvest the tea and make the tea.

[WIND BLOWS]

LOUW: So the production factors play a role in when tea gets harvested conventionally. But the tea, from what I’m seeing, the tea is responding to rain events, not season patterns but rain patterns.

[WALKING BACK TO TRUCK, ENGINE REVS UP]

CURWOOD: As we leave the experimental plot, the ironies sink in. Wild tea is more resilient than cultivated tea, but it does its best when it is harvested during the rainy season, yet traditional methods of curing the tea must be used when there is no chance of rain.

Windbreaks help prevent soil erosion.

(Photo: Eileen Bolinsky)

Like much good research, this study is raising as many questions as it is answering…for example, what cost-effective techniques could be used to process wild rooibos when it rains? And could timing the harvest according to the rains help the cultivated rooibos, as well? Long established farmers in the region as well as people trying to get started like Koos all share the changing climate of this place, and hopefully all can share in the benefits of the adaptation strategies that farmers, as well as scientists, develop in the coming seasons.

[TRUCK MOTOR]

CURWOOD: Meanwhile, Koos is working toward a future that he hopes he can pass on to his children. And he’s confident with his experience and faith and the findings of the researchers, he’ll find a way to survive.

KOOS: Come and see me and we pray for the rain. Come and see me in five years time.

CURWOOD: What happens if it doesn’t rain?

KOOS: Ah, I will never say that it won’t rain. It will rain. God makes summer, winter, spring and everything. You know, that’s one thing that a farmer must have - he must never lose hope.

CURWOOD: South African farmer, Koos Koopman. Well, in the Succulent Karoo seven years on, the wild rooibos and the adaptation strategies have proved their value. Production and exports of organic rooibos have expanded, and researchers there are now turning to traditional methods in collaboration with local livestock farmers to find out how their flocks can cope in the face of hotter summers and less predictable rainfall.

[MUSIC: Hugh Masakela “Grazing In The Grass” from Live At The Market Theater (Four Quarters Entertainment 2007)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth...rethinking energy use to fight global climate change - how that's working out for some South African winemakers.

BACK: I’d like to think that we’re taking at least 20-25% off the bottom line as far as fuel and electricity goes.

CURWOOD: Doing well by doing good. Next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Alicia Juang, Helen Palmer, Poncie Rutsch, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth