June 5, 2015

Air Date: June 5, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

US House Votes New Fishing Rules

View the page for this story

Before 1976, global fishing was largely unregulated and foreign trawlers were depleting American fisheries, providing the impetus for the Magnuson-Stevens Act. The Act’s strong federal management standards implemented by regional councils have helped national fish stocks recover. But as Andrew Rosenberg of the Union of Concerned Scientists tells host Steve Curwood, the Act is up for reauthorization, and the changes passed by the Republican-led House of Representatives would improve monitoring but could also weaken protections. (07:10)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about a coral reef protections controversy in Australia, and an effective plan to manage and conserve water in Israel, in a region known for its water crises. And we remember the life of marine pioneer and explorer Jacques Cousteau, who was born 105 years ago this week. (04:25)

World Sailors Call For Plastic-free Oceans

View the page for this story

Since 1973, world-class sailing teams have competed in the Volvo Ocean Race, traveling nearly 40,000 miles around the globe from port to port. In their 9 month sprint, teams face high winds, unfavorable seas, but to their dismay, plastics ranging in size from microbeads to bags and polystyrene mountains are becoming an obstacle and harming marine life. Concerned for the health of seas, Ocean Race organizers along with policymakers, scientists and sailors recently gathered in Newport, RI to discuss the disturbing problem and push for policies that will protect our oceans for future generations. (04:30)

Testing Boston Harbor for Plastic

View the page for this story

Boston Harbor has undergone a historic cleanup over recent decades, but little is known about the nature of pollution from microplastics. These tiny plastic particles are everywhere in the world’s oceans, and scientists believe they’re a major threat to wildlife and human health. UMass Boston graduate student Tyler O’Brien tests the waters for these particles down at Savin Cove and explains the process, and how it could help us better understand the extent of microplastic pollution. (05:30)

Meeting the Challenge of Plastic Marine Debris

View the page for this story

Plastic is an indispensable material in the daily lives of millions, but as it makes its way into our oceans its global ubiquity poses a serious threat to marine ecosystems. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Dr. Sandra Whitehouse, a biological oceanographer and a Senior Policy Advisor for the Ocean Conservancy, about where most of the pollution comes from and what the United States can do to get a grip on its own plastic problem. (06:05)

Boston's Not-So-Dirty Water

View the page for this story

Years of pollution and waste dumping earned Boston harbor its infamous title as America’s filthiest harbor, but heavy cleanup efforts have turned it into an environmental success story. This is due in part to Deer Island’s state-of-the-art Treatment Plant, which processes all of the metropolitan area’s wastewater. The plant’s Director, David Duest, gave host Steve Curwood a tour of the plant and explained how the harbor has benefited from their efforts. (05:10)

The High Human Cost of Cleaning Up Boston Harbor

View the page for this story

Over budget and behind schedule, engineers raced to complete Boston’s Deer Island Treatment Plant. The final step before the treated wastewater outfall tunnel could be operational was to remove the plugs to release the cleaned water into the sea. Author Neil Swidey’s book Trapped Under the Sea relates the story of the five men who were sent on this ill-planned and untested task. Swidey joins host Steve Curwood on Deer Island to explain what went wrong, and the lessons learned. (10:50)

Kittiwake: A Life on the Edge

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Iceland is a volcanic country lashed by the North Atlantic. Still, writer Mark Seth Lender finds Black-legged Kittiwake daring to nest on inhospitable cliffs, and to hunt for fish in the tumultuous waves. (03:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Andrew Rosenberg, Tyler O'Brien, Sandra Whitehouse, Dave Duest, Neil Swidey

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Looking at the oceans, they’ve become a dumpsite, and we could face disaster if we don’t clean up our act.

WHITEHOUSE: In ten years we may have one ton of plastic in our oceans for every three tons of finned fish.

CURWOOD: But it’s not just the vast garbage patches that float in open ocean that are a concern: plastics break down into tiny microparticles.

O’BRIEN: Microplastics have been proven to have horrible effects for the environment and potentially human health. Microplastics will be ingested by small animals and those animals are eaten by larger animals and it just moves its way up through the food web in the ocean, and a lot of those animals we are actually eating as consumers.

CURWOOD: We’ll have plastics and much more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada, “Zoetrope,” In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country, Warp Records 2000]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

US House Votes New Fishing Rules

The pollock fish stock in Alaska is in good shape, thanks to the Magnuson-Stevens Act. (Photo: NOAA FishWatch)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The oceans cover over 70 percent of the Earth and they contain more than 95 percent of its water. The seas regulate our climate, feed billions, and provide half of the oxygen we and all the other creatures need to breathe. The UN designates June 8th as World Oceans’ Day, and that’s why they’re the focus of today’s program. This year’s theme is Healthy Oceans, Healthy Planet, and one area of crucial importance is the health of seafood. Since 1976 the US has relied on the Magnuson-Stevens Act to protect fisheries, first extending national waters to 200 miles to exclude foreign trawlers, and later setting sustainable catch limits. Well, the Republican-led House of Representatives just reauthorized Magnuson-Stevens to include such new technologies as electronic monitoring. But critics say some changes could hurt sustainability, and the President has promised a veto. Andrew Rosenberg is a former northeast regional administrator of the National Marine Fisheries Service, and joins us. Welcome to Living on Earth, Andrew.

ROSENBERG: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Andy, for listeners who aren't familiar with the Magnuson-Stevens Act, tell us what it is, where it came from and how it works.

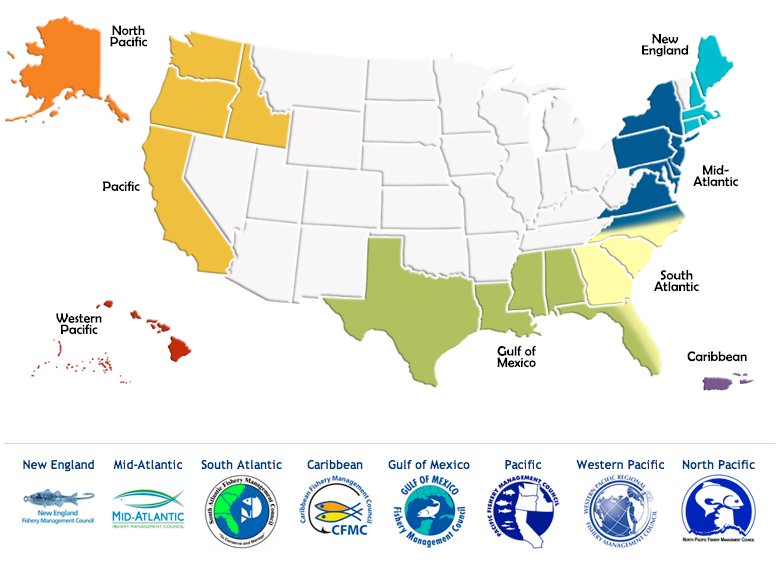

ROSENBERG: Well, originally it declared a 200 mile limit back in 1976 and then internationally the UN agreed in the Law of the Sea convention a 200 mile limit for all coastal states, but it also then set a set of management criteria for US fisheries within 200 miles of our coast. It gave authority for management to joint authority between the National Marine Fisheries Service and a set of regional fishery management councils. It's actually a quite unique structure, and those regional management councils are populated by representatives from each of the states and representatives from the affected industries, and sometimes those from other groups, including conservation groups. And those councils are charged with developing management plans for US fisheries.

CURWOOD: So how have these fisheries management plans worked over the years, in general, and then be specific about a couple, if you will, please.

ROSENBERG: Well, if you look back through history, initially we pushed all the foreign fishing vessels out at different rates in different coasts. Each of the regions did things slightly differently, but unfortunately in many places we replaced foreign overfishing with domestic US overfishing, and so that resulted in depletion of resources on most of our coasts. And over time the law has been modified to try to end the problem of overfishing for US fisheries — quite successfully, I would note, although it took us 30 years to do.

CURWOOD: Why do you think the act has been more successful in certain regions than in others?

There are 8 fisheries management councils in the US that work with the federal government to conserve fisheries and manage public and private interests. The councils are comprised of scientists, commercial and recreational fishing sectors and conservationist groups, among others. (Photo: National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA)

ROSENBERG: There's a number of important reasons. One is the starting position. The act has been very successful in Alaska and maintaining the fishery, but they had a really good starting position, effectively, for the pollock fishery, which is the dominant fishery, as well as crabs and others. They were not in an overfishing situation, whereas in New England, already there were very substantial depletion. A second reason is really regional culture, and how the councils were set up, and what their ethos was when they were set up, and so each of the councils has had different resource problems to deal with and different biology of the species, incidentally, but also a different culture within the council about what they view their job as.

CURWOOD: So we've had these revisions of Magnuson Stevens. What's going on with this recent effort to reauthorize it?

ROSENBERG: Well, the reauthorization effort now is really part of a push to change the way the authority for regulation works overall, from a federal government lead, to more authority to the regional management councils and what is labeled as “greater flexibility” in the law, so that those councils can address problems in different ways and different timelines. What it's doing is backing off on the strong standards that are in the law that the councils have had to meet — and, frankly have resulted in our ending overfishing — in the name of giving greater authority and flexibility to these regional bodies.

CURWOOD: Let me see if I understand what you're saying. In your view, the recent legislation to reauthorize Magnuson Stevens would weaken the protection of America's fisheries.

ROSENBERG: Correct, in my view, that's very much the case, that it would certainly weaken protections. For example, the law currently says if a fish stock, marine resource, is overfished — in other words, too much fishing pressure — without getting into any of the technical details, you should if it all possible, if it's biologically feasible to do so, rebuild that resource within ten years. That sets a strong timeline by which the councils must create a management plan. Now, in fact there's quite a lot of flexibility in there, but having that deadline is really quite important. The proposed modifications to the law would say, “well, we don't really need to restrict it to ten years, we can give the councils more flexibility, they can phase-in reductions in fishing pressure to account for economic factors.” Even though almost every analysis I've ever seen or ever done indicates that phasing in is an overall negative both economically as well as for the resource, because, unfortunately, the fish aren't there to wait as you decide you want phase in and make adjustments more slowly; if you continue to overfish, you continue to deplete the resource. So that's just a bad idea. You need to hold people to tighter timelines.

CURWOOD: Why weaken this law if, in your view, it's been so successful?

ROSENBERG: In every stage of the management process, it's always going to be contentious because you're telling people they can't do things that they want to do, because you're trying to manage for the public good, not for an individual entity or business. But one way to deal with a very contentious situation is to call for more flexibility, “Well, we'll take several more years to phase this in, so it'll ease the pain," even though that doesn't really work. And so that's one of the reasons.

Andrew Rosenberg is the Director of the Center for Science and Democracy with the Union of Concerned Scientists. (Photo: Courtesy of the Union of Concerned Scientists)

A second reason, and actually a really, I think, dangerous part of the proposals that are being put forward are that it would give the Magnuson-Stevens Act some primacy over -- essentially overriding other laws that regulate environmental actions, including the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Endangered Species Act, the Sanctuaries Act, and so on. The fisheries councils would basically substitute for those laws, and that's a really dangerous thing to do, because you can imagine that many other industries — energy industry, shipping industry, coastal development — would all say, “Well, gee, if the fisheries management councils could do this, then we don't really need to be subject to these rules either, because we can do an equivalent analysis." But that means that we're undermining the basic environmental protections that we have in the country, that actually have made a difference. And the consequences of that, I think, are really dire.

CURWOOD: Andrew Rosenberg is the Director for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thank you so much for taking the time today.

ROSENBERG: Thank you, Steve. I really enjoyed it.

Related links:

- The House passes Magnuson-Stevens Act reauthorization

- US Regional Fishery Management Councils and rules

- More about the Magnuson-Stevens Act, amended 2007

- National Marine Fisheries Service involvement with the Act

- Tracking commercial fishing vessels, globally

- Reauthorization Status of the Magnuson-Stevens Act

- “House bill would add 'flexibility' to federal fishing law”

- Andrew Rosenberg’s work with the Union of Concerned Scientists

Beyond the Headlines

CURWOOD: Well, we’ll check up on the world beyond the headlines now. As usual, we turn to Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org for a sidelong view on the news. He’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. In keeping with the oceans theme of the show, I’ve got a couple of items that are a frothy mix of good news and bad news.

CURWOOD: OK we’re ready to dive…

DYKSTRA: Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is not “In Danger,” according to the United Nations World Heritage Committee. But… it’s complicated.

CURWOOD: Huh, how so?

DYKSTRA: Well, the UN heard from conservationists and scientists about a multitude of threats to one of the world’s natural wonders – ship accidents, pollution, acidification, warming temperatures. But they also heard from the Australian government and the state of Queensland, where the reef is worth about three-quarters of a billion U.S. dollars a year in the tourist trade, and despite all the concerns and some real evidence of potential damage, the UN stopped short of offering a special status to the reef.

CURWOOD: The Australian government’s pretty much been at war with conservationists in recent years. Isn’t this causing an uproar?

DYKSTRA: Not really. The UN is sort of putting Australia on Double Secret Probation to protect the reef, and they’ll revisit the issue in 2017 to see how good a job they’re doing down under. The biggest new concern for the Great Barrier Reef is that Queensland is Australia’s coal country, and coal exports to Asia have to go around the reef — or, in one unfortunate case a few years ago, through a shortcut in the reef. In 2010, a Chinese coal freighter ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef trying to illegally cut through it. It caused a lot of damage and a lot of anger. Environmentalists view the 2017 date as a chance to force the Australian government to live up to its promises to protect the reef. Now let’s talk about a place where they’re making great strides taking the salt out of saltwater.

CURWOOD: OK, you’re on…

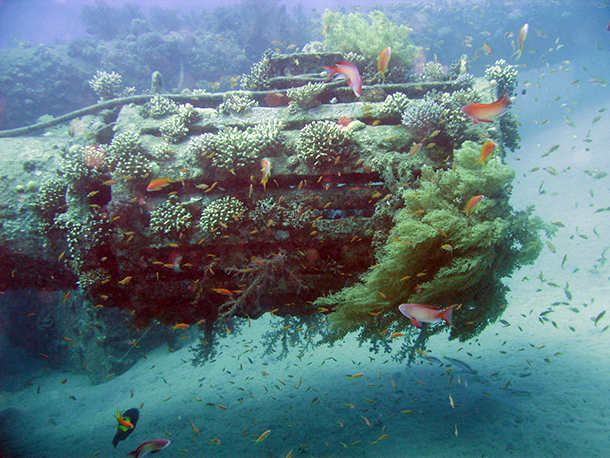

A desalination pipe coated in life off the coast of Egypt (Photo: Prilfish, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: In the Middle East, there’s something to break the pattern of too much strife and not enough water. So put aside the age-old rivalries and politics for just a second and check out what is mostly a success story. Through a combination of desalination, conservation, and water recycling, Israel has largely pulled out of what used to be a perpetual water crisis. Fixing leaky water systems, recycling used water for farm use, cutting overall use in both farms and homes, and desalination plants that now provide one-sixth of the country’s water will help save aquifers, and stop the Sea of Galilee from turning into a mud puddle.

CURWOOD: This sounds a little too good to be true, Peter. Historically, isn’t desalination energy intensive and expensive?

DYKSTRA: Not nearly as much as it used to be. The newer plants in Israel have brought the energy use and water costs way down. But there’s always a catch, and in Israel, it’s concern that sucking in billions of gallons of seawater along the Mediterranean coast will harm fish and other sea life.

CURWOOD: So this catch might be a smaller haul for fishermen?

DYKSTRA: Maybe!

CURWOOD: Well, I hope you’ve brought a marine moment in history for us.

Marine pioneer Jacques Cousteau would have been 105 this week. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Yes indeed. One hundred five years ago this week, one of the greatest ocean explorers was born. Jacques Cousteau contributed to the invention of scuba gear, then used that gear to take cameras underwater. Starting in the 1950’s, he produced underwater documentaries that were like nothing that had ever been seen before, opening up a new world beneath the surface to human eyes.

CURWOOD: He really did; you know, we tend to think of the great explorers as having lived centuries ago, but Jacques Cousteau is a modern pioneer.

DYKSTRA: Let’s throw in the word visionary, too. Like any explorer, it wasn’t always easy. His son Philippe died in a seaplane accident in 1979. His iconic ship, Calypso, was accidentally rammed and sunk in 1996, finally restored years later, then after Captain Cousteau’s death in 1997 there was a messy family feud over the estate, the rights to the Cousteau name. But the family’s back on course, Cousteau’s surviving son Jean-Michel and his grandchildren, Philippe and Alexandra, continue to educate and defend the sea.

CURWOOD: So, with all these new threats from climate disruption, overfishing, acidification, plastic pollution, what would Captain Cousteau think about the oceans today?

DYKSTRA: Well, a few years ago, his son Jean-Michel said Jacques Cousteau would be simply heartbroken. But he added that the Captain would still be hard at work, and clearly his legacy continues that work.

CURWOOD: Thanks Peter. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and the DailyClimate.org. Talk to you next time!

DYKSTRA: Thank you Steve, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website – LOE.org.

Related links:

- UNESCO heritage experts decide not to list Great Barrier Reef as 'in danger'

- Aided by the Sea, Israel Overcomes an Old Foe: Drought

- About Jacques Cousteau’s son, Philippe, who died in a seaplane accident

- Jacques Cousteau “would be heartbroken” at our seas today

[MUSIC: Smith & Meyers, “Sittin at the Dock of the Bay,” Acoustic Sessions EP, Atlantic, 2014]

CURWOOD: Coming up… heading to the dock of the bay to find out what’s in that seawater.

Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Medeski, Scofield, Martin & Wood, “North London,” Juice, Indirecto, 2014]

World Sailors Call For Plastic-free Oceans

May 15, 2015, the Ocean Summit on Marine Debris takes place during the Volvo Ocean Race Newport stopover. Attendees ranged from the sailing community and scientists to government and policy officials and more, all concerned about the health of our seas and the dangers of waste pollution.Crew member Eric Peron inspects the keel as Dongfeng Race Team sails through a floating patch of trash and debris in the Strait of Malacca during the third leg of the Volvo Ocean Race. (Photo: Sam Greenfield, Dongfeng Race Team)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The world’s oceans face numerous threats: there’s pollution and coastal habitat destruction related to industry and development, and they are becoming more acidic, thanks to CO2 from fossil fuels that promotes climate change. Fossil fuels are also the basis of plastic, and enormous and growing amounts of plastic are endangering our oceans. Plastics foul our beaches, swirl in vast mid-ocean gyres, kill the seabirds and sea turtles that mistake it for food, and lurk in micro-sized particles that are hazardous to much of marine life.

So this year, in connection with the round-the-world Volvo Ocean Race, policymakers, scientists and sailors recently gathered in Newport, Rhode Island, for a summit on the problem of plastic marine debris. Dee Caffari is part of the all-women racing crew for Team SCA.

CAFFARI: I’ve spent the last ten years having the ocean as my workplace, and I’ve covered a fair few miles. But what saddens me is the amount of waste that I’ve seen increase in my playground. And if I use some the examples from just this edition of the Volvo Ocean race, it is quite shocking. When we came through the Malacca straits we saw numerous volumes of polystyrene. Now, this is floating, this is made by us, used by us, and we can’t dispose of it. Every flat screen TV looked like it had been unpacked in the Malacca straits.

[AUDIENCE CLAPPING]

Catherine Novelli, US Undersecretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy and Environment (Photo: Ainhoa Sanchez /Volvo Ocean Race)

CURWOOD: The basic message of the day was that 80 percent of the plastic in the ocean comes from the land. Catherine Novelli, US Undersecretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy and the Environment, explained.

NOVELLI: This problem of plastic waste in the ocean is a perfect example of what we can all do. Because we know that plastic is useful. It helps health care, food preservation, it can reduce energy use as lightweight packaging, but plastic is the ultimate irony. Because many of these products are created for a single short term use, and then they live on for centuries as trash. So somebody might properly discard a water bottle, a bag from a grocery store, or some packaging that came with a new cell phone, and they can put it in the trash or recycling, but that plastic waste could stay with us for a really long time. And when it’s not properly managed, as you’ve seen, it finds its way into our waterways and ultimately the ocean.

CURWOOD: Laws and regulations can help, and already some localities ban microbeads in cosmetics and cleansers, and ban or charge for the thin plastic grocery bags that have little value for recyclers.

But Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democratic US senator from Rhode Island, held out hope that a more comprehensive federal approach could be adopted.

Ocean debris, including plastics, often collects in gyres, due to their circulating currents. (Photo: Avsa, Wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0)

WHITEHOUSE: There is a bipartisan Senate Oceans Caucus. There are a lot of issues we can’t address because some of our colleagues can’t talk about them, but one of the ones we have agreed to address on a bipartisan basis, Senator Murkowski and I are the two leads there, is marine debris. And we are now framing what that agenda is going to be. Our first was IUU pirate fishing. We got four treaties confirmed last year on one day that it had taken nine years to get the previous four treaties confirmed. So we actually have a little bit of a record. So, while we don’t have an answer yet, we do have a live process towards an answer in the Senate that is bipartisan, and I encourage you and everyone else to work with us to put teeth into that and make it work.

CURWOOD: As the Ocean Marine Debris summit moved to a close, Wendy Schmidt of the 11th Hour Project threw out a challenge to turn the talk into action.

SCHMIDT: I like to think about future generations looking back at us, and they will have, one way or another, a view of us. And they will either look back and they’ll hate us, because we didn’t have the courage to act and to make the world a better place. Or they might look back at us and love us. They might look back at us and thank us, for doing nothing less than saving their world for them. Thank you very much.

[AUDIENCE CLAPPING]

Related links:

- Volvo Ocean Summit on Marine Debris

- More about British yachtswoman Dee Caffari

- More about Catherine Novelli, US Dept of State Under Secretary for Economic Growth, Energy and the Environment

- More about Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI)

- More about Wendy Schmidt

Testing Boston Harbor for Plastic

Microplastic particles found in Chesapeake Bay (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, the next generation of marine leaders is taking on part of this challenge, by trying to understand the levels of plastics in Boston Harbor. The once notoriously polluted harbor has undergone an impressive cleanup in recent years, but there isn't much information on the extent of microplastic pollution. Still, there are eager graduate students at the University of Massachusetts Boston working to change that.

[SOUND OF WAVES LAPPING ON A DOCK IN BOSTON HARBOR]

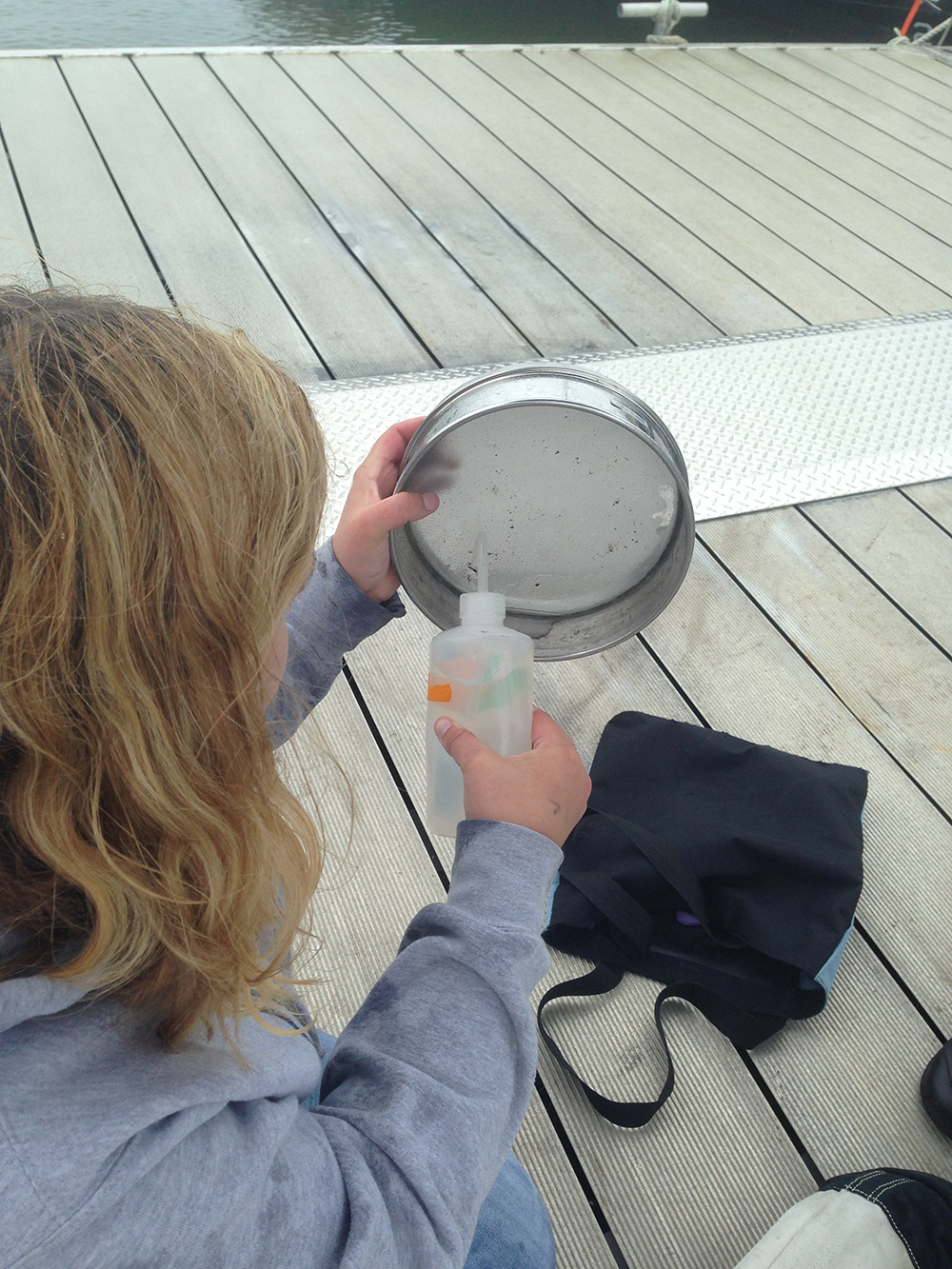

O'BRIEN: My name is Tyler O'Brien. I am a graduate student here at the University of Massachusetts Boston and I'm in the Marine Science and Technology's Masters. We are going to sample for microplastics here in Savin Hill Cove. Microplastics are pieces of plastics that are five millimeters in length or shorter, and they come from land-based sources, such as larger plastic, such as bags, bottles, everything that we have wrapped in plastic. And they can come into the water from land-point sources, rivers, streams, rain events. Plastic doesn't necessarily decompose, but it just breaks down through sunlight and wave energy. They can also just be from personal care products that are already small, like toothpaste and facial cleansers that have those little microbeads in them.

UMass Boston graduate student Tyler O’Brien gets a sample from Boston Harbor using a plankton net tow. (Photo: John Duff)

[OCEAN WAVES LAPPING ON THE DOCK]

Microplastics have been proven to have horrible effects for the environment and potentially human health. Microplastics will be ingested by small animals, and then those animals are eaten by larger animals, and it just moves its way up through the food web in the ocean. And a lot of those animals we are actually eating as consumers. So there are potential health hazards because of the chemicals that leach out of plastics.

The last five, ten years is really the only literature that's out there, and I think it still has a very long way to go to actually grasp how much is actually in our waters, how the abundance of microplastics. There's been research in the gyres and the great garbage patches and now it's really, what about our coastlines, where all the stuff is probably entering? So there's a lot of unknowns, but I think that we're in a really cool position to start really understanding it.

Today I just have a plankton net tow, so plankton talking about the little species in our water, and I am going to just take a plankton net tow to get the fixed volume, to see if there's microplastics in this sample. I'm going to do a one meter net tow today just to what's on the surface of the water, the water column. Alright. Here it goes.

Tyler explains how she’s going to treat her water sample to test for microplastics. (Photo: John Duff)

[METAL CLANK AND SPLASH]

O'BRIEN: So I just lower the net to the depth I want. Right at the one-meter mark and I just pull up.

[WATER SPLASHING]

O'BRIEN: There it goes. Now, with the sample I just collected, I have two metal sieves. One is 300 micrometers and the other is 63 micrometers. And I'm just going to pour the sample throughout the two different sieves that are stacked on top of each other and that will give me different size fractions of plastic, and why this is important is because I'm really trying understand the abundance, the composition, and the different sizes, maybe, throughout the water column. The size in general is important because zooplankton can feed on the smaller microplastics, which are usually 63 microns in size, and that just goes for further implications: well, maybe these plastics are moving up our food webs in the ocean, and plankton is the basis of all life in the ocean. Everything feeds off something that's fed off plankton, or they feed on plankton. Whales feed directly on plankton, and they're one of the largest animals, so just imagine the amount and concentration that can be going through the food web.

Tyler filters out larger particles before sending the sample to the lab. (Photo: John Duff)

Once I collect my sample I'll be going to my lab, and I am going to digest any biological material that might be on plastic, and it'll just leave me the plastics or other things that could be in the sample, could be glass or other materials like that. And from there, I'm going to further analyze it with instruments that will tell me the actual chemicals, or the composition of that specific plastic. So I can hopefully identify them further.

So, right in this sample right here, a lot of that floating debris is actually zooplankton and other phytoplankon species. So zooplankton are animals and phytoplankton are plants, but if you can see deep in the sample there, there is a blue speck. What it is, I'm not sure, but if I had a guess it's probably a piece of plastic of some sort. I am trying to get a baseline understanding of what our microplastic issue might be in Savin Hill Cove, and more, Boston Harbor in general. But just having the small sample area just to get the preliminary work down will be very important, probably, for future research and other people taking on similar projects.

CURWOOD: That’s UMass Boston graduate student Tyler O’Brien, testing the water for micropollution in Boston Harbor’s Savin Cove.

Related links:

- Invisible Ocean, an online short documentary about the ocean’s plastic problem

- The School for the Environment at UMass Boston

Meeting the Challenge of Plastic Marine Debris

A Blue Heron with a plastic bag. One way to keep plastic debris out of the waterways and ocean is to recycle it. While many nations are still lacking effective recycling programs, Sweden is not one of them. They are able to recycle about 99% of household waste by requiring recycling units within 300 meters of each residential area. But Sweden hasn’t always been so eco-friendly—in 1975 it recycled only about 38% of its waste. (Photo: Andrea Westmoreland, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now Dr. Sandra Whitehouse is a biological oceanographer and Senior Advisor to the Ocean Conservancy and one of the scientists who presented at the Oceans Summit in Newport. We asked her to explain some of the numbers for us. Dr. Whitehouse, welcome to Living on Earth.

WHITEHOUSE: My pleasure.

CURWOOD: We're talking about debris in the ocean, marine debris, and much of the concern, of course, is around plastic. So how much plastic are we putting in the ocean these days?

WHITEHOUSE: We have our first global estimate of plastic inputs into the ocean with the publication of the paper in the journal Science, where it was estimated that we're putting in approximately 8 million metric tons worldwide of plastic into our ocean.

CURWOOD: Every year.

Large amounts of marine debris drift off the land and come together in gyres, circular currents found in each of the world’s oceans. The biggest is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Much of the plastic debris is tiny bits of microplastic suspended below the surface in a soupy mixture. As the plastic breaks down, it releases toxic chemicals like bisphenol A that threaten marine life. (Photo: Lindsey Hoshaw, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WHITEHOUSE: Every year. If we continue on this rapid acceleration of plastic leakage into the oceans, in 10 years we may have one ton of plastic in our oceans for every three tons of fin fish, and that is a frightening prospect.

CURWOOD: Where is all this plastic coming from?

WHITEHOUSE: There are two major sources of ocean plastic. 20 percent is actually still coming from sea-based human activities, direct dumping of plastic in garbage off of boats, fishing gear that's either been lost or improperly discarded, or from containers spilled into the ocean. But what we also know is that 80 percent of plastic is originating from land from the human activities there, and, in that case, it's from a number of different sources. We now know that the 50 percent of the leakage of plastic into the ocean is currently coming from five rapidly developing countries in Asia and Southeast Asia, and those are: China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Sri Lanka.

One major source of marine plastic pollution is the tiny microbeads found in everyday products like facewash and toothpaste. Microbeads soak up pesticides, flame-retardants and other harmful chemicals, which can work their way up the food chain from fish to human beings. Fortunately, cosmetic companies are phasing out the use of microbeads in their products. (Photo: JB, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, in round numbers, China puts about 30 percent of this plastic into the ocean. How does plastic get into the water from China?

WHITEHOUSE: In China, it's really a collection problem. There are lots of people who live in rural communities, where the waste management infrastructure consists of only collecting your trash and putting it into a community dump, which is often on a riverbank or close to a waterway.

CURWOOD: Where is the United States on this list of the sources of plastic in the ocean?

WHITEHOUSE: United States is at number 20 on the list.

CURWOOD: That's pretty big number. Why are we in the top 20?

WHITEHOUSE: That is a big number, and it's really for three reasons. One, we have a lot of people living within the coastal area. Two, we generate a fairly large amount of waste on a daily basis. And three, a full 13 percent of that waste is made of plastic.

CURWOOD: Dr. Whitehouse, where are the success stories of keeping plastic out of the ocean?

WHITEHOUSE: Well, I would point to Sweden as being a country that has come further than we have in the United States, in terms of their waste management. For starters, they produce about a fifth as much waste per capita per day, and the proportion of that waste that is plastic is about a quarter what ours is here in the United States.

Marine debris has proven particularly deadly for sea turtles since they cannot regurgitate—and plastic bags bear an unfortunate resemblance to jellyfish. When debris breaks down in a turtle’s body, it releases gases that cause the turtle to float on the water’s surface, where it cannot feed or hide from predators. (Photo: Ryan Somma, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what could we do in the United States to improve things, in terms of keeping plastic from getting into the ocean?

Dr. Sandra Whitehouse is the Senior Policy Advisor to the Ocean Conservancy. (Photo: courtesy of Dr. Whitehouse)

WHITEHOUSE: Well, there's always for improvement in our own ways in management infrastructure. The combined sort of overflow systems in many cities are still somewhat antiquated. We can also continue to reduce littering; however, I think here in the United States, we also have an opportunity, as a developed country, to look at reduction or elimination of some plastic products. We use excessive packaging for many of our consumer products, even including our food, and, as example, I was in the airport last week and I wanted to buy a banana, but it was on top of a Styrofoam tray, wrapped in plastic. Nature's already produced the perfect packaging for the banana. We don't need to put it on a Styrofoam tray and wrap it in plastic. As an innovative, developed country, we can be redesigning our products so they don't include plastic. There's really no reason to have facial scrubs, have the microbeads made of plastic that then get washed down the sink and into the waterways and oceans. We can make products out of different materials. We can't redesign ourselves out of this problem worldwide, but I do believe here in the US we can make some progress with recycling and production.

CURWOOD: Dr. Sandra Whitehouse is a biological oceanographer and a Senior Advisor to the Ocean Conservancy. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WHITEHOUSE: Thank you for focusing on this very important issue.

Related links:

- Study: Calculating the ocean’s plastic pollution from land

- Plastic debris delivers toxins into the oceans, hurting humans too

- Steps to reduce plastic pollution

- Global effects of marine debris on ecosystems

- Sea turtles are suffering from the effects of marine debris

- Microplastics destroy ocean health

- Many ocean garbage patches full of plastic exist

- Microbeads in cosmetics are harming marine life

- Sweden recycles 99% of its household waste

CURWOOD: You can hear our program anytime on our website or get a website download. The address is LOE.org, that's LOE.org. There, you'll also find pictures and information about our stories, and we'd like to hear from you. You can reach us at comments@LOE.org. Once again, comments@LOE.org. Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. And you can call our listener line, at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988.

[MUSIC: Jon Brion, “Tabla,” Punch Drunk Love Soundtrack, Nonesuch 2014]

CURWOOD: Coming up: keeping sewage out of seawater, and what it cost in Boston Harbor. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Punch Brothers, “Passepied" (Debussy), The Phosphorescent Blues, Mercury 2009]

Boston's Not-So-Dirty Water

Twelve 130-foot-tall, egg-shaped digesters process the solid waste collected from Boston’s sewers. The system turns sludge into biogas, which is used to heat the plant; steam, which generates electricity; and processed solid waste that’s then turned into fertilizer pellets. (Photo: Frank Hebbert, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: The Standells, “Dirty Water,” Dirty Water, Tower/Capitol 1966]

CURWOOD: Love the place or not – back in the day, the “dirty water” was no exaggeration – sewage went into Boston harbor only partially treated, and the water was truly foul.

DUEST: Boston harbor was one of the dirtiest harbors in the nation, and we were actually rated at “D” or below for water quality. As a matter of fact, you couldn’t fish or swim within Boston harbor for most of the days out of the year.

CURWOOD: That’s Dave Duest, the man in charge of the answer to Boston’s filthy harbor. It was so disgusting that in the early 1980s, a series of lawsuits were filed, requiring proper treatment of Boston’s sewage. There were numerous delays, and the new infrastructure cost nearly $4 billion, though it doesn’t catch the microbeads we know about today. Still, by the year 2000, there was a modern treatment plant on Deer Island.

DUEST: We are actually in the middle of Boston Harbor, which is the outermost stretches of the metropolitan Boston area, and Deer Island treatment plant serves 2.3 million people, which is about 34 percent of the total state population for sewage treatment services.

CURWOOD: If you ever come to Boston, you see Deer Island from the aircraft. You’ve got these iconic big egg-shaped containers, looks like you're trying to hatch something out here. What, in fact, do they do?

With a peak capacity of 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater treated per day, Deer Island Treatment Plant is the second largest wastewater treatment plant in the nation. (Photo: Anthony92931, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

DUEST: They're actually a critical part of our wastewater treatment operations. We actually put all of the solid material that is conveyed within the wastewater into those vessels, each one of those being 3 million gallons apiece; and we have a dozen of those.

CURWOOD: All that flushing creates a lot of water. What happens to the water?

DUEST: We get, on average, 360 million gallons of wastewater a day into this plant, with peaks up to 1.3 billion gallons per day. All of that material gets pumped to Deer Island and then lifted up into the treatment process. After we clean it up, we remove 94 percent of the total solids out of that wastewater, and the remaining clean water then gets disinfected, dechlorinated and then sent out into Massachusetts Bay for final disposal.

CURWOOD: And where does that water end up?

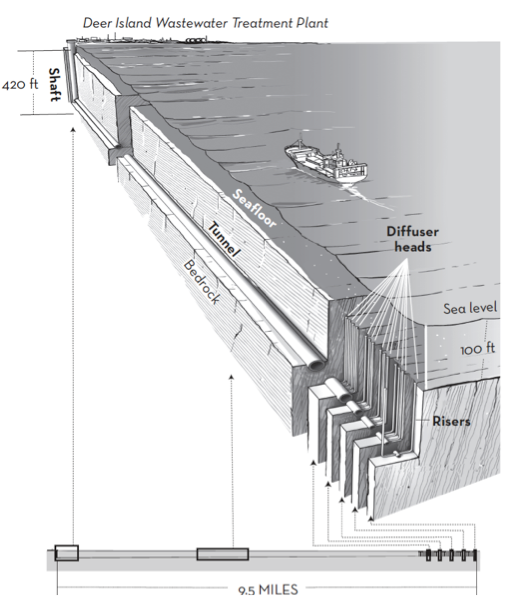

DUEST: Eventually, all the treated effluent is disposed of and Deer Island's outfall; goes into a deep broad tunnel that's 450 feet below the surface, travels nine-and-at-half miles eastward out into Massachusetts Bay. And that gets distributed over that last mile and a quarter through 53 risers that are just like sprinkler heads on the bottom of the ocean floor. And that actually disburses over a wide area, so you don't get that single one open end of a pipe that's going to impact that one area.

CURWOOD: And so, now, today, in Boston Harbor, what's different about the ecology here?

DUEST: The ecology is actually greatly improved. We've gone to a full secondary level of treatment so the quality of the effluent that leaves the facility is much, much cleaner than it was ever in the past. We haven't had any permit violations for over eight years now, and we're actually seeing a recovery of the harbor, so that things like Eel grass are actually naturally reestablishing themselves back into Boston Harbor. Eel grass is a very sensitive natural species of sea grass that only grows when the water is very, very clean.

Foam floating on the treated water is the result of chlorine that’s added to kill bacteria. The foam is skimmed off before the water travels down a 10-mile-long outfall pipe to the outer reaches of the harbor. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: Well, I'd really like to take a look at this outfall. I'm not sure I want to go all the way down the tunnel, and I guess it's full, so I can't right?

DUEST: You cannot. If you go in there it's the point of no return. You'll come out nine-and-a-half miles later, and about 12 hours later, actually.

CURWOOD: But I really want to take a look at where this is, so let's head over there.

DUEST: That sounds good.

[SOUNDS OF RUSHING WATER]

DUEST: Alright. We are now at the end of the disinfection basin just prior to the start of the outfall tunnel.

CURWOOD: It looks like sort of a ladder of a bunch of waterfalls with, well, a fair amount of detergent. Don't tell me that from somebody's washing machine.

DUEST: What you're actually seeing there is a little residual chlorine, that's actually causing a little bit of foaming. All of that foam, however, is collected in our systems and never actually makes it out into Massachusetts Bay. But really what you're seeing is the water spilling over and dropping about 10 feet over the edge and then filling up to a certain level, providing the head that it needs to send it to the outfall.

CURWOOD: Now, I'm looking over the side here, and I'm seeing — oh, there's a really deep long channel that goes way down. What am I looking at here?

Host Steve Curwood, on right, with David Duest, the Director of the Deer Island Treatment Plant in Boston, MA. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

DUEST: There's a bypass channel that you're seeing down below, which is actually one of the recycle streams. We use treating effluent as cooling water for some of our facilities.

CURWOOD: So how do you guys feel about this operation? How good is it?

DUEST: Deer Island's actually been in operation for 20 years, and it's doing very, very well. We're seeing the recovery of Boston Harbor, we're seeing no impacts to Massachusetts Bay, so I’d say that the Deer Island Treatment Plant is meeting its goals and objectives.

CURWOOD: Dave Duest is Director of the Deer Island treatment here in Boston Harbor. Dave, thanks for taking the time to walk us around your plant.

DUEST: You're welcome.

[MORE WATER SOUNDS]

Related links:

- How the Deer Island Treatment Plant works

- About the Boston Harbor cleanup

- “Boston Harbor: The Anatomy of a Court-Run Cleanup” (Academic paper)

- Video: “How We Cleaned Up the ‘Dirtiest Harbor in America’ – Travel Channel’s Off Limits

The High Human Cost of Cleaning Up Boston Harbor

By the time it was completed, the outfall tunnel contained oxygen-starved, toxic air that would be deadly to anyone who breathed it. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

CURWOOD: Well, Dave Duest mentioned the deep rock tunnel that channels the cleaned water nearly ten miles under Boston Harbor. It was an engineering feat that had a human cost as well. Boston Globe writer Neil Swidey chronicles this story in his recent book, "Trapped Under the Sea: One Engineering Marvel, Five Men, and a Disaster Ten Miles Into the Darkness." It tells the story of a group of divers whose lives depended on untested technology and questionable decisions, with deadly consequences. And overlooking the now sparkling harbor from Deer Island, he told us about it.

SWIDEY: I was fascinated by this story that I didn't know about, and that most people even here in Boston didn't know about, which was the final piece of this massive cleanup of Boston Harbor and the people who put their lives on the line to create this beautiful harbor that we see today. After building this massive, sophisticated treatment plant, there was the construction of the world's longest tunnel of its kind. It sends the treated wastewater out into the deep Atlantic waters of Massachusetts Bay. That tunnel, and the final piece of that tunnel, was the subject of the book.

The outfall tunnel carries effluent, or treated wastewater, from Deer Island Treatment Plant nearly 10 miles out into Massachusetts Bay. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

CURWOOD: You write about the people who worked on that last bit and the accident that happened. First tell me, what was the set-up. Why, in your view, looking back, was this an accident waiting to happen?

SWIDEY: It's fascinating. This project here that did this miraculous conversion and transformation of this harbor, taking the nation's dirtiest harbor, turning it into its cleanest urban harbor, it was a remarkable transformation. The people who worked on that were some of the best and the brightest minds in the world, and they made a host of good decisions over a decade, but at the end they made some serious and tragic bad decisions that forced a group of blue-collar workers to risk their lives to rescue this project.

CURWOOD: What exactly did these blue-collar workers have to rescue?

SWIDEY: So at the very end of the tunnel, it chokes down and it goes from 24 feet wide to just five feet in diameter. The whole point is this massive tunnel moves up to a billion gallons of treated wastewater through every day, and yet it doesn't use a single pump or electrical source — it's all gravity that moves that effluent through the tunnel every day.

While the project was being built, there was a series of safety plugs at the end to protect the sandhogs, the tunnel workers, for the decade that it took to build the tunnel. Nobody figured out how those plugs were going to get out. At the end, when this project was over-budget, past deadline and under federal court order to meet these deadlines, there was an enormous amount of pressure, an enormous amount of infighting among the various contractors and subcontractors, managers. Nobody could get along. Trust had gone down on the project. The powers-that-be looked for a rescue artist to come in, and that was a team of commercial divers who were going to go into the tunnel, which by the way at this point had been removed of all of its life-support, the oxygen, the lighting, the transportation. All those systems had been removed, but the tunnel wouldn't work unless these 55 safety plugs, these stoppers at the end of the tunnel, were removed.

Five divers were sent into the tunnel to release 55 safety plugs that would prevent the tunnel from flooding in the event that a diffuser head was damaged. Without the plugs’ removal, the outfall pipe would not be operational. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

CURWOOD: So somebody had to go down there and get those corks out. Some divers were hired. Doesn't sound so bad at this point, but I guess it went bad. What happened?

SWIDEY: Well, basically, divers were asked to do something that never been done before, because this was so far out, so remote and so confined, this space at the end of the tunnel, just five feet in diameter. In fact, those plugs were nestled in connector pipes that were 30 inches wide, so just slightly wider than our shoulders.

CURWOOD: Well, wait a second...I'm going to say...how does somebody get in there?

SWIDEY: They had to crawl in there, and the most fundamental source of risk on this was that it was too far out to bring conventional air supply that divers would be used to — high-pressure bottled air. You'd use up all your supply just getting out to this remote spot, and you wouldn't have the time to crawl into these slimy connector pipes in pitch black and remove these.

CURWOOD: So just to be clear, there's air in this tunnel, but apparently it's not air anyone can breathe.

SWIDEY: Yes, the tunnel hadn't been filled yet, so they didn't send in divers to swim into the tunnel. They sent in divers because they guys know how to do dangerous jobs in environments where they have to bring in their own air. At this point, deep into the tunnel a decade after it was being built, one or two breaths of the ambient air would be fatal, it was oxygen-starved, toxic air. And so the divers had to bring in their own breathing gear, something that they're used to. But the air they're used to has been tested, it's bottled air, it's a supply that you can trust. This was too far out, so this hotshot engineer that they hired came up with this plan to mix liquid oxygen and liquid nitrogen right there in the tunnel and turn that into breathable air.

The five men traveled as far as they could in the narrowing tunnel in two Humvees they’d brought – one towing the other backwards. Since there would be no room to turn a Humvee around, they planned to abandon one vehicle and drive the other back when their dangerous mission was complete. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

CURWOOD: This hotshot engineer gets the job as the lowest bidder?

SWIDEY: He gets the job really as the only bidder. The contractor cast about and they found a couple of people who came and toured this and said, "Sorry, no thanks. I don't care how much you're paying, it's not worth it. I can't do this safely." But this one engineer came in and said, "I can get you out of this jam and I've got this innovative cutting-edge plan to do this." But he didn't go in. He sent in this team of five divers, and not all of them made it out alive, tragically.

CURWOOD: So what happens?

SWIDEY: So five divers go into the tunnel. They take these converted Humvees — two of them, one towing one in the opposite direction — because once you get in, there's not enough room even to open the doors all the way, so you just take the other one heading back the other direction when you want to get back.

CURWOOD: This sounds bad already.

SWIDEY: Yeah, but then the Humvee could go only so far. Two of the divers would stay in the Humvee monitoring the breathing system for all five, while three proceeded on foot using umbilicals, hoses that were connected into the main system, and they went out into the dark to try and get these plugs out.

CURWOOD: So what exactly happened?

Since the air in the tunnel was so toxic, the divers needed to bring their own air. But their air supply system, which had never before been used on a project, malfunctioned – proving deadly for two divers. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

SWIDEY: This experimental breathing system that hadn't been fully thought through failed. At the very end, when the three-man excursion team who were on foot crawling, went into these narrow pipes and they pulled a couple of plugs out, and the foreman of that crew looked up at that one point and all their umbilicals had become tangled because it was so confined and there was so much crawling around back there and he said, "Let's stop and let's iron these out, let's get our things straightened out." And as that was happening, he looked in horror to see one diver collapse onto the tunnel floor and another one go right there. So he lunges for a safety valve to switch the divers to a back up system, and then they try to connect with the divers who were back in the Humvee to see what the oxygen percentage was. And, as you know, the oxygen we breathe is not 100 percent, it's 21 percent oxygen, but if it drops very far below that 21 percent, bad things happen. And he knew that if that percentage was below 16 percent they were in deep trouble, and so he said, "What's the oxygen percentage?" and they said, "We'll have to check,” because the system was so jerry-rigged someone had to leave the Humvee to check the pressure valves and come back. And then he reports back that it's 8.9 percent and then the line goes dead.

CURWOOD: So we know the story. So that means that some of them got out alive, but not all, I gather. How did the ones survive?

SWIDEY: Three drivers made it out alive, two tragically did not, but one of the most jarring revelations for me was how close it came to all five divers perishing — it was 30 seconds — 30 seconds, had that foreman not reached for that backup valve when he sensed trouble, all five of them would have perished.

CURWOOD: Well, surely, in these modern times we would've had the capability to not have that. How the heck did this happen in the face of how smart we're supposed to be?

The Living on Earth crew on-scene as host Steve Curwood speaks with author Neil Swidey. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SWIDEY: Yes, well, I think it happened because of organizational failure at the end of this project. When you have a situation where the contractor and the manager and the owner aren't getting along, you have to fix that, because if you don't fix it then this is what can happen. You have a lot of people who are responsible for this amazing project here who don't like talking about it because of how this ended, and that's a tragedy. They should be taking bows at conferences about what the success story was here, of how remarkable this transformation was here, and that means managing it all the way through. After the tragedy of the accident, the leader of the MWRA, Doug McDonald at the time said, "tensions and finger-pointing got us into this mess and worries about costs and who's going to pay what got us into this mess, so we're going to take money off the table and we are going to use our bright collective minds here to figure out how to solve this in a creative innovative way. And then we'll worry about money after that." And that gave people the permission to think creatively and come up with this innovative solution that ventilated this tunnel, got air back into the tunnel in this brilliant engineering solution that no one had thought of before, and those plugs came right – pop, pop, pop — out, in two days. The tunnel was operational and this transformation was allowed to begin. So the challenge, I think, for people looking at this is, how do we get that post-tragedy realization of, "we've got to work together here,” without suffering the tragedy?

CURWOOD: And there's a memorial for these men.

Neil Swidey is an award-winning staff writer for The Boston Globe Magazine and teaches at Tufts University. His other books include The Assist and Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

SWIDEY: So the five members of the team – DJ, Hoss, Riggs, Billy and Tim — all put together and asked to do this impossible job. Hoss, Riggs and DJ who were the furthest out, made it out alive. Tim and Billy did not. But those three who survived, that risked their lives more by bringing the bodies of their fallen team-members back, they added much more time to their already narrow escape path in order to bring those bodies home with dignity. And today, on this island, there are plaques to Billy and Tim, and there are memorial benches on this path that rings the island of bikers and walkers and roller-bladers and you can sit and look out directly above that ten-mile path of that tunnel. And you see that clean water, and you can think about those two otherwise anonymous workers, Tim Nordeen and Billy Juse and say "thank you" to them to the work that they did and that we all benefit from.

CURWOOD: Neil Swidey's book is called, "Trapped Under the Sea.” Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SWIDEY: Thank you, Steve. My pleasure.

Related links:

- Trapped Under the Sea

- Selection from Trapped Under the Sea

- About the outfall tunnel

- 1997 MWRA report on the outfall

[MUSIC: Elvis Costello, “Shipbuilding,” Punch the Clock, CBS, 1983]

Kittiwake: A Life on the Edge

Black-legged Kittiwake perch on basalt ledges above Grundarfjörður, Iceland’s turbulent sea on the Snaefellsnes Peninsula. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: The sea in Boston harbor was calm and peaceful that day, but the open ocean stands in constant and often violent opposition to the land. That’s what writer Mark Seth Lender found, when he visited Iceland and found Black-Legged Kittiwake daring to nest right on the cliffs, despite the wild waves lashing the shore below.

Kittiwake and Fulmar in the distance, Reyniusfjara, Iceland (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Kittiwake Nesting on an Ancient Basalt Core

Snaefellsnes Peninsula, Iceland

© 2015 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Lava works its way down, steams and smokes and spits as it meets cold water. Then, wears away, retreating inland till only the core remains: Black basalt crystalized in octagons like giant’s teeth, a long wall grinning and gnashing towards an ancient sea…. While the sea grins back. Waves are its teeth its tongue spray and foam. It puts the bite like Viking iron upon the stone chafing and gnawing. Pebbles that were bed rock leap as the breakers crash, roll like rain fall into the trailing spume; husssssh as the sea flows out, wusssssh, as the sea flows in. Small and small the ocean grinds volcanoes into sand. Ashes to ash, smoke to dust. Until once more the molten rock (and the landward side puts its shoulder to the task).

Black-legged Kittiwake on Evidghedsfjorden Glacier, Greenland. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Above this maelstrom, white traces the midnight rock like paint. Kittiwake, clinging to their narrow ledges where the basalt cleaved away. Their dark eyes, their black feet joined to this black place; until they spread their wings. Swooping like reckless kites down toward the gaping hunger of the sea. Then up, and through the surge on a rollercoaster of thin air, a pleasure in the peril, what else could it be? They cannot fish when the water is angry like this, and here it is angry all the time. They take a risk, the ocean reaching beyond its reach will knock them down. The fishes, coming from a line that is older (older than any of this), wisely lie beyond the turbulence. Kittiwake though they know where fish hide and where to find, instead put self (and therefore progeny) in harm’s way...

Kittiwake soar on the wind, swooping up and down in parallel with the sea’s surge, but just out of reach. Meanwhile, tasty fish lie just beneath the water’s surface. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Maybe risk is what it’s all about. And the birds are only reminding themselves: Life does not belong here. Iceland, hovering over the howling place where the Earth to its innards is split in two. The fire, patient, waiting for the break through, flexing its molten fingers until it reaches out, as the sea reaches for sea birds.

How beautiful, the way Life hangs on. How brave it is to Live.

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender, and there are photos at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- More about Black-legged Kittiwake

- Mark's guide in Iceland was Haukur Snorrason

- You can find more information about visiting Iceland at Iceland Naturally

- Nature Photo Tours provided additional support for mark's fieldwork

[MUSIC: Cassandra Wilson, “You Don’t Know What Love is,” Blue, Warner Bros 1993]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth… the great conservationist John Muir had a harsh father and a tough life – but that may have had hidden benefits.

WILLETT: It was so rough but it possibly has a lot to do with why he ended seeking sanctuary in Nature and why he was able to be so resilient.

CURWOOD: Celebrating John Muir – in music. That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Donald Fagen, “Walk Between The Raindrops,” The Nightly, Warner Bros 1982]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Shannon Kelleher, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Thanks this week to Haukur Snorrason of Iceland Photo Tours, Iceland Naturally and Nature Photo Tours. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org — and like us, please, on our Facebook page — it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth