April 8, 2016

Air Date: April 8, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Terrifying Math of Melting Ice Sheets

View the page for this story

Recent studies of the physics of ice sheets suggests that we may be vastly underestimating how fast the West Antarctic ice sheet is melting because of global warming. Penn State Climate Scientist Michael Mann tells host Steve Curwood that combined with the melting from other glaciers around the world, seas could rise over six feet by 2100, putting many coastal cities underwater. (10:50)

Climate Change Threatens Trillions Worth of Financial Assets

View the page for this story

New research from the London School of Economics estimates that a broad range of global stocks and other financial assets are overvalued because investment managers don’t take the risks of climate change into account. LSE researcher Alex Bowen tells host Steve Curwood that when investors factor in those risks, present values worldwide could fall by 2.5 trillion dollars, but the worst-case scenario is far, far worse. (05:10)

Louisianans Rally Against New Gulf Oil Leases

View the page for this story

Louisiana has long been a friendly state to the oil and gas industry, but after the 2010 BP oil spill and Hurricane Katrina, Louisiana residents are more aware of the risks associated with the fossil fuel industry. Hundreds of people recently rallied at the Super Dome in New Orleans to protest the sale of new federal leases in the Gulf of Mexico for oil and gas extraction. Anne Rolfes of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade tells host Steve Curwood that the oil industry is losing its sheen in the Bayou State. (09:30)

Marsh Restoration Revisited

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

We revisit a story from a decade ago, a year after the disaster of Hurricane Katrina. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young chronicles miscalculations in the planning of the protections for New Orleans, and experiments to rebuild the marshes that had once absorbed storm surges. (05:50)

Bayou Restoration Progress

View the page for this story

There are today ambitious plans to rebuild thousands of acres of marshes in the Mississippi Delta, the first line of storm-surge defense for New Orleans and the surrounding communities. But as Paul Kemp, wetlands expert at Louisiana State University explains to host Steve Curwood, there are still questions over the funding, and even if the marsh restoration plans work, the Delta will be far smaller than it used to be. (06:10)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s edition, Peter Dykstra shares encouraging news about India’s ambitious electric vehicles goal with host Steve Curwood, before complaining about the decline of the DC Metro system and BP’s tax breaks. (04:50)

The Place Where You Live: Morro Bay, California

/ Lauren PlatteView the page for this story

Living on Earth is giving a voice to Orion Magazine’s longtime feature in which readers write about their favorite places. In this week’s edition, Lauren Platte takes us to Morro Bay on the California coast, where the estuary is a refuge for people and wildlife alike. (04:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Mann, Alex Bowen, Anne Rolfes, Paul Kemp

REPORTERS: Jeff Young, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: New research about potential sea-level rise suggests a very damp future.

MANN: No amount of sea walls or other adaptations will be able to maintain New York City as a habitable city. We will literally need to retreat from our coastlines. We're talking about the relocation of hundreds of millions of people.

CURWOOD: And it’s not just New York – hundreds of other cities could become uninhabitable. Also, how the effects of global warming put investments at risk.

BOWEN: This is basically the impact that could take place right now today on the value of financial assets if market participants suddenly came to realize how the risks were panning out. It would be $2.5 trillion loss.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

The Terrifying Math of Melting Ice Sheets

An iceberg off the coast of West Antarctica (Photo: NASA, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks to human activities, the global warming gas CO2 has reached concentrations not seen for millions of years, back when oceans were 20 to 30 feet higher than today. Until recently many scientists thought it might take hundreds of years for melting ice in Antarctica and Greenland to cause severe sea level rise.

But now new research, including a study led by Rob DeConto, at UMass Amherst, and David Pollard at Penn State, and another led by James Hansen of Columbia, strongly suggest sea levels could rise much faster. We asked Michael Mann, a Professor of Climate Science at Penn State, to put this research in perspective. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Michael.

MANN: Thanks, it's great to be with you.

CURWOOD: So what's new here? We've known about the threat of melting from the West Antarctic ice sheet for long time.

MANN: Well, we've known it's a threat. What has remained rather uncertain is how much and how quickly, and some of these latest studies now have given us quite a bit more information particularly about how rapidly we could potentially lose large parts of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

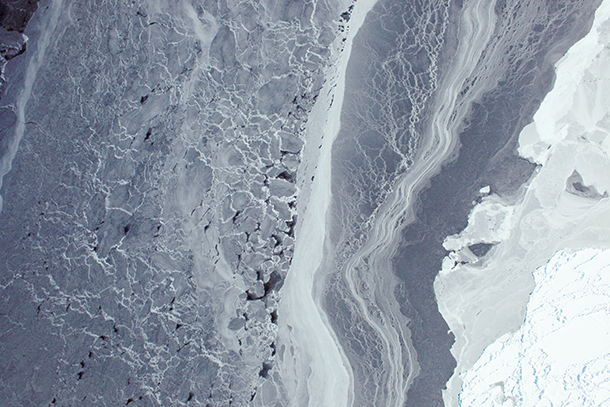

Store Glacier in West Greenland (Photo: Penn State University, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, how does this paper - your colleagues or Penn State were very much part of this process - how does this paper in nature change our understanding of the mechanics of ice sheet melting.

MANN: So, what the the scientists did actually built on some ideas of another Penn State colleague of mine Richard Alley and it has to do with the geometry of the Western Arctic ice sheet. It's a very large ice sheet, there's a lot of mass in the middle of that ice sheet and because of that downward gravitational force the bedrock actually sags in the middle. What it means is that as ice begins to break away, as the ice shelves begin to decay and expose literally an ice cliff at the edge of the ice sheet where the ice meets the ocean...well, these clips get higher and higher as you lose ice and the cliff penetrates inward towards the center of Antarctica because of the downward sloping nature of that ice sheet, and it turns out that a ice cliff structurally can only be so high before it literally collapses under its own wait and so what happens is these ice cliffs become more and more unstable and you lose ice more and more quickly and that leads to an acceleration in the rate of loss of ice that really hasn't been taken into account in past studies that didn't really resolve some of the important physics here in how ice sheets behave.

CURWOOD: Now, I've heard that the West Antarctica ice sheet is kind of like a boat aground on a shore. How accurate is that analogy and what does that mean. I mean, could the whole thing slip into the water at once?

MANN: It is a good analogy and it's essentially moored. Just like a boat has a mooring, the ice sheet is basically moored where it meets the bedrock and the shelves of the ice sheet are sort of the edges of the ice that literally spill out over the ocean and if you lose those ice shelves they don't actually contribute to sea level rise because they're already floating on the ocean just like an ice cube in a glass of water as it melts doesn't raise the level of the water - it's the same principle. The problem is those ice shelves actually act as buttresses that help prop up the inland ice and when the ocean melts those ice shelves from beneath, inland ice literally begins to calve into the ocean and it's that inland ice sheet it's the ice that is grounded that has the potential to contribute to global sea level rise, so when you melt those ice shelves one of things that happens is that you literally allow the edge of the ice shelf to lift off where it was previously in contact with the bedrock below the surface of the ocean. It's sort of like you've let it unmoored the boat, you've let it free.

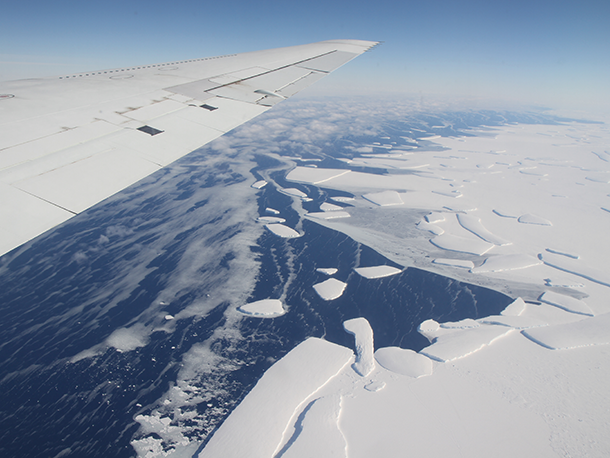

West Antarctic Ice Sheet from above (Photo: NASA, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: How much sea level rise we talking about and how soon do you think?

MANN: Well, we probably set in motion already the unstoppable loss, the decay of most of the West Antarctic ice sheet, enough to give us in 10 to 14 feet of sea level rise. What we hoped was the case and what some previous studies had suggested was the case was that it would take many hundreds of years for that to happen, but these past studies didn't really resolve the ice mechanics and the ice physics at the level that this latest study by Pollard and DeConto has done, and what they find is that when you take into account of this instability associated with the ice cliffs, that greatly accelerates the rate at which this can happen to the point where we could probably get the better part of one meter, so more than three feet of sea level rise just from the Western Antarctic ice sheet by 2100. Now, if you look at what the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and their latest report about the state of understanding of climate change, they concluded that we probably wouldn't get much more than about a meter - three feet - of sea level rise by the end of this century. What DeConto and Pollard have included is we may well get a meter of sea level rise - three feet of sea level rise - from the West Antarctic ice sheet alone by 2100. Now if you add in the contribution from the thermal expansion - as water warms it expands and so the warming of the oceans contributes to sea level rise - and we have other glaciers that are also melting and that the water is flowing off into the ocean. If you total up those contributions you get another meter, so the total now is two meters where there's a very good chance we could see two meters of sea level rise by 2100, nearly twice as much as the IPCC concluded just a few years ago.

CURWOOD: What about melting from Greenland? To what extent are the same processes in play there?

West Antarctica by plane (Photo: NASA, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MANN: So the geometry of the situation in Greenland is somewhat different. The Greenland sheet is pretty well contained by the surrounding bedrock of Greenland. It doesn't have large ice shelves spilling out into the ocean like the West Antarctic ice sheet, and because of that this particular instability that is focused upon in this latest study is unlikely to apply to Greenland. That having been said we know that during the last warm interglacial period, 125,000 years ago, before the last Ice Age, when global temperatures were very comparable to what they are now, sea level was probably four to five meters higher. What that suggests is that there was probably a fairly large loss of ice from the West Antarctic ice sheet but there was also probably a contribution from Greenland, so there is the potential that with the warming that we might see you by the end of this century under business as usual burning of fossil fuels we could get another couple meters of sea level rise ultimately from Greenland. Now, that might play out more slowly, but here's the thing...we've been subject to a few surprises already. This latest study by Pollard and DeConto was a bit of a surprise to the community so that's really reason to take some pause. In completely dismissing the possibility that the Greenland ice sheet could indeed melt faster than the models currently projected to. We know from satellite measurements that in fact we are losing more ice from Greenland than the model suggested we were likely to see at this point.

CURWOOD: So this research on the West Antarctic ice sheet adds to what we know about Greenland says that a child born today, in his or her 80s, would see another six feet or more I gather of sea level. What does that mean for coastal cities and infrastructures?

MANN: Well, I'll tell you what it means. Take Hurricane Sandy, Superstorm Sandy. That storm produced a storm surge of about 13 feet at Battery Park in New York City. Global sea level rise was one foot of those 13 feet. The storm surge was 13 feet rather than 12 feet because of global sea level rise. It might sound like a small difference but that one extra foot meant 25 additional square miles of flooding in the New York City metro area of the Jersey coastline. It meant somewhere in the range of $7 billion in additional damage. That's what one foot of global sea level rise does. Imagine what six feet of global sea level rise could do. In fact, we've been doing some work at Penn State and we find that a Sandy-like storm that produces a devastating storm surge in New York City...during the early 20th century that was roughly what we call 100 year event...it shouldn’t have happened any more often than once in 100 years. By the end of the century if we continue with business as usual burning fossil feels, that sort of event will become a one in three year event.

Michael Mann is Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science at Penn State University (Photo: Penn State University)

CURWOOD: OK. So you add six feet to 13 feet of a strong hurricane super storm in the New York area and what does that do?

MANN: Right. You know if you add six feet to that 12-foot storm surge, the surge is now an 18-foot storm surge say in 2100. A large part of New York City is below 18 feet. If a storm like that literally becomes a one in three year or one in four event, something like that happens every three to four years then we're exceeding what we call our adaptive capacity, which is to say no amount of sea walls or other adaptations will be able to maintain New York City as a habitable city. We will literally have to retreat from our coastlines. We're talking about the relocation of hundreds of millions of people. You want to talk about an expensive proposition. That's an expensive proposition, so when somebody says it will cost too much to act to reduce our carbon emissions, the fact is the cost of not acting, the damages we'll see if we don't act are far far greater. The good news if there is good news in this latest study by Pollard in DeConto, they argue that there is still time to avoid warming the planet enough to guarantee that scenario of six feet of sea level rise by 2100, but it's a narrow window of time that we have to act, and it's vastly disappearing.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thank you, Steve, always a pleasure to talk with you.

Related links:

- Read the new paper in Nature on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet

- New paper from CUNY professor Marco Tedesco on melting from Greenland

- Michael Mann teaches at Penn State University

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital, Do well and do good.

[MUSIC: Gary Burton/Chick Corea/Pat Metheny/Roy Haynes/Dave Holland, “Soon,” Like Minds, Concord Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...the risks of steep financial losses linked to global warming. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Colleen Raney and Colm Maccárthaigh, “Fonn Mall Acla,” Cuan, Colleen Raney Records.]

Climate Change Threatens Trillions Worth of Financial Assets

Coal mines in Wyoming. Coal stocks and bonds assets are risky given economic trends and the prospect of increased regulation on carbon. (Photo: Flickr Image Library CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Economists at the London School of Economics say denial of the risks of global warming, from rising seas to droughts to civil unrest, is promoting the overvaluation of certain financial assets – in other words, a bubble. Some of the risks have already been recognized, for instance, concerns over stranded assets that led shares in Peabody Coal to crash from the equivalent of more than $1,000 back in 2011 to less than $3 today.

But these economists say the risks are much broader than the fossil fuel industry. Alex Bowen of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change at LSE, is co-author of this study published in Nature Climate Change. He estimates financial assets worldwide are presently overvalued by perhaps $2.5 trillion, and in the worst case, $24 trillion. And he says massive climate-related write-downs are not far off in the future, which would mean huge losses for investors who ignore the risks.

BOWEN: This is basically the impact that could take place right now today on the value of financial assets if market participants suddenly came to realize how the risks were panning out. So the best way I think of thinking about this is what would've happened had participants in financial markets gone to sleep one night as complete climates skeptics, woken up the next morning and realized the current state of climate science. What impact would that have had on the value of financial assets at that moment? And our central guess if you like is that it would be $2.5 trillion USD loss. But then if financial market participants realized that actually some of the uncertainties were going to be resolved towards the pessimistic end of the spectrum, then they would mark down their assets as soon as they found that information. So we're talking about these losses to financial assets, they could take place today or tomorrow basically as soon as people active in financial markets change their view of what's going to happen over the next hundred years or so.

Agribusiness is one of the sectors most vulnerable to the threat of climate change. (Photo: Asian Development Bank, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sounds like you're suggesting that when financial managers wake up to the risks of climate change to their assets, we could see a phenomenal sell-off, people wanting to get rid of those assets while they could get something for them. So the median projection is that we could lose $2.5 trillion dollars overnight and we could lose 10 times that if people are super pessimistic.

BOWEN: Indeed that's the case. Now it may be that some of this value at risk as it’s called is already reflected in the current market valuations, but it's remarkable how many investment managers haven't actually looked at issues such as the prospects of fossil fuel companies in a carbon-constrained world. It's amazing how many people still doubt the climate science.

CURWOOD: So who would feel the impacts of these losses the hardest, the ones that you're projecting here?

Some economists worry that coastal real estate in towns like Miami could also be overvalued. (Photo: Daniel Chudosov, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

BOWEN: We didn't look at this in detail in the paper, but I think it's reasonable to suppose that the impacts of climate change would be fairly broadly spread, but some sectors would be hurt much more than others. I think that agribusiness would have particular problems because of the adverse impacts of climate change on agricultural productivity. Tourism is another one that's likely to be hit, and I think that amongst financial institutions wealth managers particularly exposed to any financial assets from poorer countries in the tropics will be worried about risks. Perhaps the sovereign debt of poorer countries from the tropics who are going to be hit much harder by climate change.

CURWOOD: What do you hope comes out of your paper, Alex?

Economist Alex Bowen is a Principal Research Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. (Photo: London School of Economics)

BOWEN: What I think is particularly important is that people who own or manage wealth look at the evolving states of climate science, climate economics, and keep an eye on whether scientists, for instance, begin to find that the climate is more sensitive to greenhouse gas emissions than they previously thought. We might get good news on that front. I'm not saying we're definitely going to see the pessimistic outcomes, but it’s surely very important for wealth managers to keep an eye on this kind of thing because it could have a very big impact on their portfolios, and they need to look at some of the sectors like agribusiness which would be particularly badly affected if climate change began to run away from us.

CURWOOD: Alex Bowen is a research fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics. Thanks for taking the time today.

BOWEN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read the paper in Nature Climate Change

- The London School of Economics

- About Alex Bowen

[MUSIC: Vusi Mahlasela, "Loneliness," The Voice (Ilivi Lebantfu), ATO Records/BMG]

Louisianans Rally Against New Gulf Oil Leases

Demonstrators march through the streets of New Orleans protesting gas and oil lease auctions in the Gulf (Photo: LA Bucket Brigade)

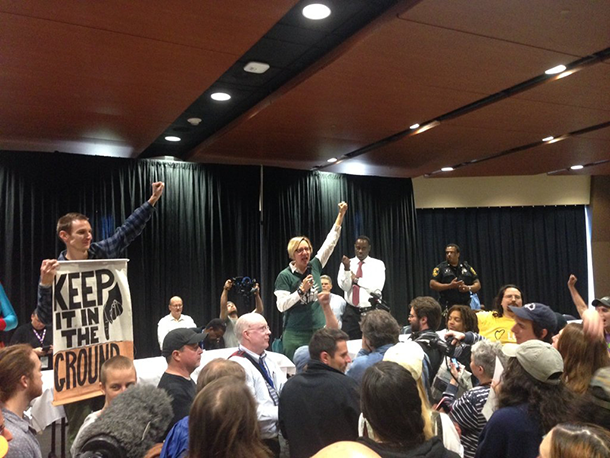

CURWOOD: Concerns about climate change have sparked a campaign to halt the leasing of public lands in the US for the extraction of fossil fuels, and recently protesters marched in New Orleans to demonstrate against a government auction of gas and oil leases in the Gulf of Mexico. Their rally at the Superdome also underscored local worries about oil spills, in light BP’s Deepwater Horizon well blowout six years ago, which spewed millions of gallons of oil into the sea. Joining us now is Anne Rolfes of the Environmental Justice Organization the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, who told us what happened at the protest.

ROLFES: We marched down the streets to the Dome. It was as if we were going to the Saints game, right? You walk into that Superdome, you're happy, you're hopeful...and even that process of marching in downtown New Orleans was an amazing experience in large part because that doesn't really happen in this part of the world. I mean, I've been working on the subject for 16 years and we certainly have not had many moments where we've had hundreds of people in the streets standing up to big oil. We did not anticipate that we would be able to get into the Superdome but we did, and so we went into that room and I think it is fair to say that we took it over. We went into the front, we stood on the podium. Yes, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management was still at the microphone but they could not be heard over our din and we had a pretty basic message which was “the gulf is not for sale”.

Protesters enter the Super Dome (Photo: LA Bucket Brigade)

CURWOOD: So what kind of impact did your protest have on the sale?

ROLFES: Well, they were able to auction off all the plots that they wanted to auction, and so their spin was, you know, “what protest?” They honestly acted as if it didn't happen and I imagine that that's strategic to try and deter us from such actions in the future, but by any measure, this is a different day and those of us who participated in this understand that and understand that this is only the beginning.

CURWOOD: Now, you'd think that certain times and places if a crowd of people marching into a federal auction that police would show up, there would be a bunch of arrests and people would be hauled off. What happened to you?

ROLFES: New Orleans has Mardi Gras and so the police do know how to handle a crowd and I think they just used that approach. They asked me at one point, "Do you want to be arrested?" and I said: “No we don't want to be arrested, we want the drilling to stop.” I think that's often a dynamic in these situations with the police and with direct action. They say, "Do you want to be arrested?" Of course that's not our goal. Our goal is to stop drilling, stop Wall Street investment and fossil fuels. And so I think it was very much the laissez-faire attitude of this part of the world.

CURWOOD: You've had firsthand experience what happens when offshore drilling goes wrong. I imagine the police officers who were there also remember what happened in the gulf. To what extent do you think the BP oil spill cast a shadow over the sale and encouraged folks who might have been less patient with you to be perhaps more patient.

Oil executives inside the lease sale (Photo: LA Bucket Brigade)

ROLFES: Well, I think that's a great point. To me there is a line before BP and after BP and I can tell you that absolutely changed attitudes. People who were willing to live with the oil industry before that aren't willing to live with it anymore, and so ordinary people, police officers, artists, students, teachers, yes, that's why we were out in force at the Superdome because it doesn't take a brain surgeon to see that we got a serious problem here.

CURWOOD: And by the way, oil and gas extraction has had a huge impact on the wetlands of Louisiana. Can you talk us a bit about that?

ROLFES: Yes, I mean one of most remarkable things about the oil industry's operations here in this state is that they're acting like it's the 1980s. They're saying the same things that they were saying then, pretending like they don't have a problem with accidents, pretending like their spills don't cause harm, and one of the greatest harms that they done to this state is they're digging of canals both for navigation but also to lay pipeline and even by their own studies, they're responsible for at least a third of the wetland loss and some accounts put it as high as 75 or 80 percent of our wetland loss. And so a result of that has been that they have physically dug out our land, which was our protection from storms and so one of the reasons that Katrina was so devastating is because of that wetland loss. The oil industries destruction of our coast makes us more vulnerable to every single hurricane that comes and one of the ironies is that the oil industry has a study that acknowledges this and yet in their own reports of Louisiana they show our state as it would have looked circa 1970, right, as if we have all of our wetlands, as if our state is really a boot like it used to be when really that boot has eroded.

CURWOOD: So then what has happened to the public mood in Louisiana about the oil industry in the face of Katrina, linked to the cause of wetlands I think in the public mind to a certain extent, to the Gulf oil spill, the Macondo well blowout there off of the Gulf of Mexico that was so devastating, BP's oils spill there, and now the threat of climate disruption, of climate change. How have these concerns and events combined to affect the public mood when you have a demonstration against more drilling in the Gulf?

ROLFES: I think that the public mood has been shifted for some time. Just in my conversations around the state, people who might have been on the side of the oil industry have shifted. I think what has though been the problem is that people think, “oh what can you do...they're huge, it's big oil...there's no way we can stand up to that”. And so, our work now is to have that opinion and those feelings manifested into action, and certainly the action at the Superdome was the first step to that.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, this isn't the first protest we seen of these kind of auctions. Tim DeChristopher famously was arrested and went to jail for buying at a lease, recently Terry Tempest Williams the author, bought land at the auction. Seems like this is all part of growing trend, huh?

Protesters carry signs inside the sale (Photo: LA Bucket Brigade)

ROLFES: Absolutely. That's what's so exciting about it, is that we are part of the movement and certainly gives us a lot of power. I mean, we had a wonderful local and regional network of groups and of individuals who worked on this and we partnered with national groups and I think this is one of the rare times in which our interests are perfectly aligned. I mean, we have the same agenda, we're part of a movement, and that's why I always have faith, right, I always have faith, and my faith comes from the people that I work with who are from neighborhoods that have been decimated by oil pollution, and yet they have remarkable faith that they can beat the Exxons and the Shells of the world, and with that example, you know, I follow their faith that we can absolutely beat this and being part of the national movement makes me even more confident.

CURWOOD: Now Obama administration recently said that it will no longer pursue offshore drilling in the Atlantic coast. What you make of that decision?

ROLFES: Well, every news report I read about that decision chalked it up to activism, chalked it up to local resistance and what is instructive for our situation is that along the Atlantic coast you had a very similar situation. You had governors and senators and congressmen and elected officials at the national level and the state level who were buying big oil's story about job creation and being able to drill safely and encouraging drilling, but on the local level you had both local elected officials and regular people and business owners and people who enjoy the beaches saying, “no”. And local people and regular people prevailed despite their elected officials, and it's a very similar situation here.

CURWOOD: Why do you think the Obama administration is going to continue to permit drilling in the Gulf but not off the East Coast? What's different?

ROLFES: Well there's no question that the idea of resistance in the Gulf of Mexico is a foreign idea and so they will take the path of least resistance. So if they don't get resistance in the Gulf, then they will drill here. They got resistance on the west coast, they got resistance on the east coast, but they have not had resistance here and that's why they're doing it. I mean, it certainly doesn't make sense in terms of his larger climate strategy. I can't possibly explain that, but they drill here because we've let them.

Anne Rolfes and others make their views heard on oil leases in the Gulf (Photo: LA Bucket Brigade)

CURWOOD: Well, so maybe there's been this push back on the west and east coast, but you seem to be leading a pushback right there in the gulf. It may be changing, huh?

ROLFES: Yes, absolutely. I mean, the push back that we've had to date has always been around mitigating the harms, you know, “please oil industry would you stop polluting, please oil industry would you stop expanding, please oil industry would you stop your accidents.” They've never cooperated with those requests and so we've changed. Now we’re saying: “Oil industry, we're not asking anymore...we're telling you not to drill and we're going to make sure that happens. No new drilling. Our days of supplication are over.” One of the expressions we had during this action was: “take your rigs and go home. You've destroyed our state for long enough”.

CURWOOD: Anne Rolfe is Director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. Thanks for joining us.

ROLFES: Thank you. Thank you.

Related links:

- About The Louisiana Bucket Brigade

- The Obama Administration holds oil and gas lease sale for the Gulf of Mexico

- Bureau of Ocean Energy and Management delayed their hearings on lease sales to accommodate public meetings following the protests

- Watch a video of Anne Rolfes' reactions right after the protest

Marsh Restoration Revisited

The Caernarvon Freshwater Diversion seen from the air. (Photo: John McQuaid, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, during April, we like to revisit some past reports to celebrate Earth day, and we’re staying down in New Orleans to catch up on a story we broadcast a decade ago – before the disaster of the Deepwater Horizon – but after the disaster of Hurricane Katrina. That monster storm killed nearly 2000 people, flooded large portions of the city and caused $100 billion worth of damage. It also brought home how many years of building canals and pipelines to accommodate oil drilling in the Gulf had helped erode and destroy the marshlands that once protected New Orleans from furious storms. The Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with building 125 miles of levees to protect the city. But the protections they built were not high enough – they were only designed to hold back storm surge from an average hurricane. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young reported back then on the protection efforts and how they fell short. Retired Army Corps General Gerald Galloway said the plans were inadequate.

GALLOWAY: I would argue that the problem began when we failed to specify the level of protection to be provided.

YOUNG: All along, the Corps plan to protect New Orleans was based on a late 50s study by the weather service guessing the strength of storms most likely to hit. It was called the standard project hurricane.

Cost-cutting measures may have encouraged the Army Corps of Engineers to build the levees New Orleans too low for adequate protection. Many levees breached in multiple spots in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, flooding much of the city. (Photo: News Muse, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

GALLOWAY: When we picked the standard project hurricane for New Orleans we were picking low not high. We went in the wrong direction: instead of taking the biggest storm that we could conjure we took a sort of moderate storm and as we’ve seen the results were disastrous.

YOUNG: The Corps upgraded its storm calculations with a study in the late 70s. Louisiana State University Hurricane Center Director Ivor Van Heerden says the Army even issued a directive in 1981 to use those new findings and design protection for a stronger storm.

VAN HEERDEN: Unfortunately the corps seems to have stayed with the 1959 definition of a standard project hurricane, which was a much, much weaker storm.

YOUNG: They paid for this study. Why didn’t they use it?

VAN HEERDEN: We see cost cutting efforts one after the other. And we see this term in their internal correspondence—about “this will cut costs, this will cut costs.” So it looks like, perhaps, that the use of a weaker hurricane meant you didn’t have to build levees as robust or as high and as a result you cut your costs.

YOUNG: So was the problem a shortage of money? The storm protection system was still not complete when Katrina hit. And the Bush administration had cut maintenance budgets for levees. But still, Louisiana got more money for Corps projects over the past five years than any other state—nearly 2 billion dollars. Steve Ellis is with the budget watchdog group taxpayers for common sense.

Floodwall construction along the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, or MRGO (Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

ELLIS: So it wasn’t that we didn’t spend enough money, it was going to the wrong things. Rather than concentrating our resources and maintaining what we had and trying to actually provide adequate or better flood protection we were building other things across the state.

YOUNG: Ellis says Corps projects too often waste money and hurt the environment. The Corps says it’s changed to make restoration a major part of its mission. Two Corps projects just a few miles apart provide evidence for both arguments: the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet and the Caernarvan diversion.

[NAT SOUND OUTDOORS ON CAERNARVAN LEVEE]

YOUNG: So I’m walking along the Mississippi river levee of the downstream from New Orleans at a big bend in the river called the english turn in St Bernard’s Parish. There’s a little community called Caernarvon. Now Caernarvon is locally infamous, because in 1927 during the great flood, the powers that be that ran New Orleans dynamited the levee right here. It’s one of those funny coincidences of history that if you visit Caernarvon these days you’ll find there’s another intentional hole in the levee. Listen, you can hear some of the Mississippi river rushing through the levee. This time the goal is to use that water to save some of the disappearing wetlands.

VILLARUBIA: This is right near the spot where the levee was blown up and so we’re trying to replicate that albeit in a much in a smaller way.”

The wetlands fed by the Caernarvon Freshwater Diversion support wildlife including alligators (Photo: Corey Harmon, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

YOUNG: Biologist Chuck Villarubia manages the Caernarvon freshwater diversion for Louisiana’s Department of Natural Resources. It’s an Army Corps project that the state now operates.

VILLARUBIA: And what we have is a series of five tubes, that are 15 by 15 feet. That then distributes the water from the river into the marsh. What this does is help simulate the overflow flooding that happened before the levees were here.

YOUNG: OK. and so are we gonna open the gates here?

VILLARUBIA: Yeah we can open the gates and show ya how it works.

[SOUND OF RUSHING WATER UP THEN UNDER ]

YOUNG: With the gates fully open 8 thousand cubic feet per second of muddy Mississippi rush through. In some parts of the country that would be a river itself. But it’s spare change here.

[WATER SOUND FADES INTO NAT SOUND OF BIRDS, A LITTLE WIND]

YOUNG: The river water pushes back saltwater from some abandoned fields. Now the marsh is starting to come back, as is wildlife.

VILLARUBIA: There’s an alligator--pretty decent sized one--kind of checking us out a little bit.

YOUNG: The concern about losing wetlands and the land itself is so great, it must be satisfying to come here and say, ‘we’re starting to turn the tide’ at least a little.

VILLARUBIA: Caernarvon I think has been successful, it’s been nice to see it work And particularly now after the hurricane we’ve seen, and we’ve known that we need to have this marsh in front of the levees to make them more effective. Most of the levees look fine there, at least in this area. So we need to make this wetland restoration work along with levees for the protection of the whole area.

CURWOOD: That’s Chuck Villarubia of the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources, ending that portion of Jeff Young’s report from a decade ago.

Related link:

U.S. Government Accountability Office report on Hurricane Protection System

[MUSIC: The Blind Boys of Alabama, "You and Your Folks/23rd Psalm," Higher Ground, George Clinton/Clarence Haskins/William Nelson/Bernard G. Worrell, Real World Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how the efforts at restoring the wetlands of Louisiana are faring now. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: James Booker, “Black Minute Waltz,” Junco Partner, Frederic Chopin/James Booker, Hannibal Records ]

Bayou Restoration Progress

Louisiana’s wetlands comprise about 40% of the nation’s wetland area, but coastal erosion erases between 25 and 35 square miles of the state’s wetlands per year. (Photo: Ryan Hagerty, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Over a decade after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans is in many ways a different city, but still not fully protected by levees and rebuilt marshes. There are ambitious plans to restore the wetlands that once buffered the city, but progress is not as fast as it might be. To update our report from a decade ago, we turn to Paul Kemp, who teaches Oceanography and Coastal Science at Louisiana State University. Welcome to Living on Earth.

KEMP: Thank you, Steve, I'm pleased to be here.

CURWOOD: Now in our earlier piece, we spoke with a biologist about the Caernarvon freshwater diversion project. What's the status of this project today?

KEMP: Well, it's our oldest operating artificial river diversion and it's been now operating since 1991.

CURWOOD: And what is it designed to do exactly?

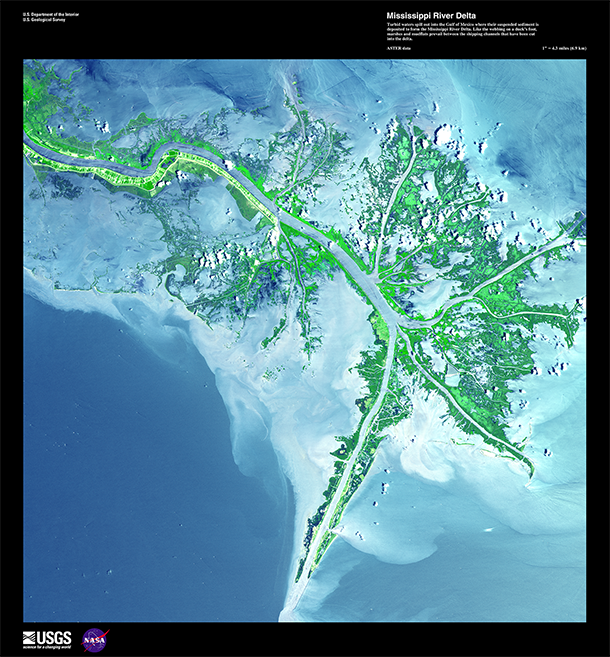

KEMP: Well, the Mississippi River built the Mississippi River delta. It spread out and delivered water across hundreds of miles of coast through many channels called distributaries. It's understood that if we’re going to have this delta survive with the kind of sea level rise that we're seeing, we have to recreate those distributaries and that's what Caernarvon is, it's the model for a new artificial distributary system.

Wetlands restoration is an important piece of minimizing the impact of storm surges like Hurricane Katrina. (Photo: Information, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA)

CURWOOD: How successful is the Caernarvon diversion project in terms of rebuilding the wetlands there?

KEMP: Well, its purpose was actually to keep salt water that was moving up into the wetlands, keep it farther out to sea, mostly for the benefit of people growing oysters. It has had a beneficial effect on, on the wetlands also. It's actually building a small delta and in places it's enhancing the productivity of the marsh but it's not really meant as a land building marsh.

CURWOOD: Now, what about other such diversion projects. How successful are they proving?

KEMP: We have only three artificial diversions operating right now. Caernarvon as I said is the oldest. There's another one on the other side of the river that's about the same size called Davis pond, and it's been around since the early 2000s. And then we have the West Bay diversion, and so we only have really three of these diversions in operation.

CURWOOD: So there's a major overarching plan. It's a 50-year plan for $50 billion to rebuild as much as some 33,000 acres of wetlands marshland. What's been achieved so far if anything with that?

The Mississippi River Delta played a vital role in shaping much of Southern Louisiana over thousands of years. (Photo: ASTER data (direct), Wikimedia Commons)

KEMP: Well I mean a lot has been achieved. I mean land loss continues of course because a lot of what pushes land loss is actually the sinking of the Delta and the rising of sea level which is a global phenomenon, but we are now getting close to opening up diversions that are large enough to really reverse loss over substantial areas; the footprint of the delta of the 21st century will be much smaller than it is today, but it will still be a very substantial delta.

CURWOOD: By the way, the West Bay diversion, how's that doing, what's it done in terms of useful amounts of rebuilding land?

KEMP: Well it's done quite a lot. We have seen a tremendous amount of development both below sea level and more of it now above sea level with vegetation beginning to take hold there. What we learned was that you have to protect the the areas that are receiving sediment from waves and that when you do that land building really takes off.

CURWOOD: Paul, all of this is very expensive. As I understand it the penalty portion of the BP Deepwater Horizon settlement was slated to go to restoration, but in the end I understand it was less than some had hoped. How do you feel about that?

KEMP: Well I mean, the plan ...the 50 year plan that you referred to earlier, Steve, this is a $50 billion plan, and so even when we're talking about the billions in terms of the settlement with BP we're still talking about only a fraction of what is needed. There are pressures of course in this time of very tight budgets to try and move some of that funding toward other important purposes - education, health so on in the state - but those are being resisted very strongly. What we have found is that people in the state and actually at the national level have understood that this is something that has to happen for there to continue to be a place for us to live.

CURWOOD: Professor, recently federal government auctioned off a large tranche of oil and gas leases for the gulf. How might that help or hurt the cause of rebuilding the wetlands?

KEMP: Another source of funding that has been identified is actually mineral revenues from the outer continental shelf. There was a law passed several years ago that stated that starting in 2017, a portion of the proceeds from lease sales and royalties that would normally go to the federal government would actually be distributed to the coastal states that are really feeling the impact of that development in terms of losses to the environment, that will provide additional revenue for coastal restoration.

Paul Kemp is a Coastal Oceanographer and Geologist at Louisiana State University. (Photo: courtesy of Paul Kemp)

CURWOOD: So, Paul, ultimately how hopeful are you about all of this looking ahead?

KEMP: I guess it's more my nature to be hopeful. I teach students and they are helpful and I encourage them to be hopeful and to take an active role in restoration and to restore our coastal landscapes. I think there is some reason to be hopeful. As I said we have the advantage of having the Mississippi River, which is a huge land building asset if it is properly managed.

CURWOOD: Paul Kemp is a geologist, marine scientist and wetlands expert at Louisiana State University. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

KEMP: It's been great, Steve.

Related links:

- Proposed oil and gas leases in Louisiana

- Caernarvon Freshwater Diversion Fact Sheet

- Paul Kemp’s Research

[MUSIC: Dr. John, "Traveling Mood," In the Right Place, James Waynes, ATCO Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Indian company Tata unveiled its “Megapixel” model, a range extended electric vehicle, in 2012. (Photo: TheChargingPoint.com, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now it’s time to find out about stories beyond the headlines. We join Peter Dykstra of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hello, Steve. Let’s start out with a little good news and then after that, I can get back to complaining about stuff like I usually do.

CURWOOD: You feeling all right? Good news?

DYKSTRA: I’m fine Steve, and the good news is that with both traffic and air pollution choking its cities, India is planning to set a goal of 100% electric vehicles on the street by the year 2030.

CURWOOD: Well that would be terrific, and address both climate change and really bad air there, but usually such goals made to be forgotten, right?

DYKSTRA: Often they are yeah you’re right, but hats off to India for reaching high. Only two other nations have made similar pledges, and they’re far more affluent ones – Norway and the Netherlands. India would face huge obstacles in making EV’s affordable, not to mention charging EVs with clean power. But fighting climate change is a pretty good long-range incentive, and not being able to breathe is a really good short-term one, and the huge Indian automaker Tata has some proven experience putting affordable cars on the road.

CURWOOD: As I recall they made a $3000 car just a few years ago and it doesn’t hurt to have an economic example if your marketplace has over a billion people in it.

DYKSTRA: Absolutely, India has immense energy obstacles and opportunities. Over 50 million Indian households still don’t have basic access to electricity.

CURWOOD: Ah, I hear an opportunity for solar. Hey, what’s next; you mentioned something about a complaint?

DYKSTRA: Yes, I have a complaint. From opportunities abroad to something I regard as a national disgrace here at home. When I lived and worked in Washington DC throughout the 1980’s, the Washington Metro system was a mass transit model – architecturally striking, remarkably efficient, and at the core of the revival of a city that suffered from decades of traffic and urban decay. Now, its only 40 years old, but the Metro’s falling apart, in deep financial trouble, and with no bright prospects for recovery.

Washington, D.C.’s Metro transit system hasn’t aged well in the past forty years. Union Station, above, is one of three stations serving the Capitol Hill area. (Photo: Bossi, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Huh? What’s going on with the DC Metro? Usually crumbling infrastructure is from stuff that was built you know a hundred years ago or so.

DYKSTRA: Well, maintenance problems, from unsafe trains and tracks to broken escalators and also a projected hundred million dollar budget shortfall this year, that’s what’s wrong with the Metro, due in part to a Byzantine funding formula where Metro has to go begging every year to Maryland, DC, Virginia, local governments and the Feds. Congress created Metro in the 1970’s, but aiding public transit is not very high on the list of action items for an inactive Congress.

CURWOOD: And the irony here is that there are two stops for the Metro on either side of the Capitol building; that’s the way Congressional staffers to get to work.

DYKSTRA: Actually there are three stops that are pretty nearby the House and Senate office buildings! It’s also the way I got to work for a dozen years. And here’s what happened recently; the current boss of the transit system declared an abrupt one-day shutdown to Metro’s rail system last month, tying the city in knots in the middle of the week. Ridership is down 6 percent this year as commuters lose faith in the system, which means the DC area’s beleaguered roads get more crowded. It’s one thing to hate big government, but it’s a shame when you neglect your capital city.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Hey what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

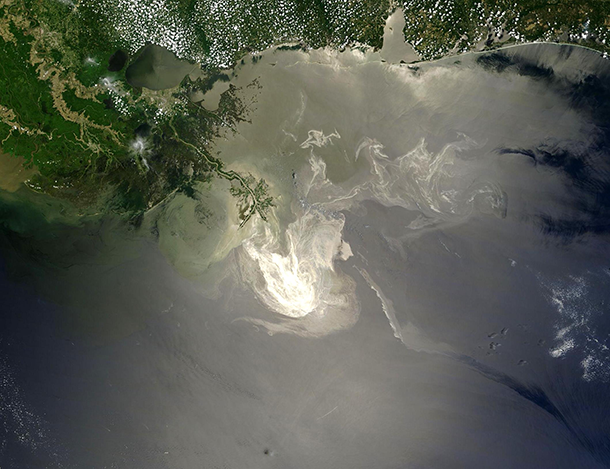

DYKSTRA: Something from seven years ago this week. The U.S. Interior Department granted British Petroleum what’s known as a “categorical exemption” from environmental impact assessments for its Deepwater Horizon drilling platform. Deepwater Horizon, maybe you’ve heard of it?

The massive oil slick from the Deepwater Horizon well blowout reflects back sunlight in this photo taken by NASA’s Terra satellite. (Photo: NASA/GSFC, MODIS Rapid Response, CC government work)

CURWOOD: Err – duh! I mean this has got to be one of the worst oil disasters of all time. What was the reason for the exemption?

DYKSTRA: Because the Interior and its Minerals Management Service yielded to arguments from BP lobbyists that major spills just don’t happen anymore

CURWOOD: Oh yeah, I’d forgotten. A year later, I think, President Obama repeated that reasoning.

DYKSTRA: Yes he did, just 3 weeks before Deepwater Horizon exploded, sank, and gushed oil for months and of course let’s not forget that 11 workers died in the disaster.

CURWOOD: And another casualty was the bureaucracy, the Minerals Management Service.

DYKSTRA: Right, they were heavily criticized for failing to regulate the offshore industry. And you might remember BP’s Gulf Spill response plan included items like how to protect the Gulf of Mexico’s walrus population - apparently they just cribbed it from an Arctic oil plan. The agency was reorganized under a different name following the BP disaster. But let’s wrap this up with a riddle: Why is BP’s $20 billion fine for the oil spill like a gift to public radio?

CURWOOD: Huh?

DYKSTRA: Well, because they’re both tax deductible. Last week a federal judge ruled that BP can write off three quarters of the fine as a routine cost of doing business. Happy tax Season, everybody!

CURWOOD: Ok! Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much for taking the time, Peter.

DYKSTRA: OK Steve, thanks a lot we’ll talk to you soon!

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE dot org.

Related links:

- The Times of India: “India aims to become 100% e-vehicle nation by 2030: Piyush Goyal”

- The New York Times: “Washington Metro, 40 and Creaking, Stares at a Midlife Crisis”

- The Washington Post: “U.S. exempted BP's Gulf of Mexico drilling from environmental impact study”

- Reuters: “Walruses in Louisiana? Eyebrow-raising details of BP’s spill response plan”

- OilPrice.com: “Most Of BP’s $20.8 Billion Deepwater Horizon Fine Is Tax Deductible”

[MUSIC: The Beatles, “Tax Man,” Revolver, George Harrison, Parlophone Records]

The Place Where You Live: Morro Bay, California

The calm waters of the estuary reflect a colorful sunset (Photo: Lauren Platte)

CURWOOD: We head off to the California now, for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to put their homes on the map and submit essays to the magazine’s website, and now we’re giving them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

CURWOOD: There’s a watery theme in today’s show – and this essay fits right in…

PLATTE: I'm Lauren Platte and this is my essay about the Morro Bay Estuary.

The Platte family at the Morro Bay estuary (Photo: Lauren Platte)

From above, the Estuary of Morro Bay looks like a primeval lung, chambered and channeled, spongy marsh and slick black mud. It exhales nutrients and minerals of land into sea in clouds of silt, the tide swelling and sucking. A slow, susurrus breath.

[SOUNDS OF BLACK BRANT, AND SEA WASH]

When Black Brant land in legions you hear their social gabble, guttural and constant, borne across the water on salt-soaked air. They drift in great raucous rafts, mingling with other wet-winged mariners. Ancestral spirits gathering.

Great-Granddad called this place his Innisfree. He and Great-Grandma-Mom migrated here from North Hollywood in the 1950’s, and the family, flocking, followed them. Ancient Estuary became new homeland. Our heartland.

Platte’s parents were married at the estuary in 1970. (Photo: courtesy of Lauren Platte)

[MUD SOUNDS, SEAWASH, SEABIRDS]

As a child I sank barefoot, knee-deep, into this sponge. Squished mud between toes. Grew to recognize the glimpse of eternity when starlight glimmers upon the glassy mirror of a spring tide. To feel the whispered, billowing sigh as I am absorbed.

Embedded in its flesh, I’ve grown as much a part of this organism as the marsh grass, one with ebb and flow.Whether by call of seabird, magnetic migratory pull, or by surging breath of tide, I too have been drawn back into the land of my birth. I’ve borne my own children here, raising the fifth generation of our blood in this mud.

[CHILDREN PLAYING]

Singing prayers to the stars that they too may set their children’s feet on this land one day. That the Estuary will still respire, each inhalation teeming with life. Our homeland. Our heartland. Breath of this body. Center of the soul.

Platte’s daughter enjoys paddle boarding at the estuary (Photo: Lauren Platte)

[MUSIC: Vitamin String Quartet, "Home," Tribute to Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, Modern Wedding Collection II (Vitamin Records 2013)]

PLATTE: My great-grandfather was a retired English professor and college counselor. He called this place Innisfree in reference to a poem by William Butler Yates. And to me the meaning is that of a refuge, a place of peace where people can come and live a simple live with the natural world. It's a place of refuge for others, too, not just us, but it's an important layover site for migratory birds every year, primarily the Black Brant and other geese who come in droves, the Cinnamon Teal, the Hooded Merganser, the white pelicans, many visitors that come to this place every year on their journey south.

[BIRDS]

My son, he just turned four and my daughter just turned nine. We love to take them out on kayaks, on standup paddleboards. My husband has a fishing boat so they'll go out on the estuary and just catch and release.

Platte’s 4-year-old shares a silly moment while out paddle boarding on the bay (Photo: Lauren Platte)

[WATER SPLASHING]

SON: Whoa, it's big.

PLATTE: It has really become a part of their childhood too. Unfortunately things are changing now, a long awaited sewer is being built in our town and with it will come a lot more building and development. So I feel like the more of us who connect with this place, the longer it will exist as a healthy ecosystem and be protected.

[MUSIC: Vitamin String Quartet, "Home," Tribute to Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros, Modern Wedding Collection II (Vitamin Records 2013)]

Lauren Platte lives in Baywood Park, California near the Morro Bay estuary. (Photo: Brittany App)

CURWOOD: Lauren Platte, and her much-loved home at the California shore. You can tell us about the place where you live if you like. There’s more about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read Lauren Platte’s full essay on the Orion Magazine website

- About black Brant geese

- Morro Bay National Estuary Program

- Morro Coast Audubon Society

- Surfrider, San Luis Obispo Chapter

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Peter Boucher, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Thanks this week to the McCaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1 Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth