April 15, 2016

Air Date: April 15, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Youth Win Right to Sue Feds Over Climate Change

View the page for this story

A federal judge in Oregon has found that 21 young people have the right to sue the federal government for failing to properly protect future generations from the dangers of climate change. Vermont Law Professor Pat Parenteau tells host Steve Curwood it’s a surprising and perhaps landmark decision that shows climate change is a unique challenge for the legal system. (09:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood discuss the fact that the numbers of wild tigers are growing, that responses to replacing lead water pipes differ from city to city and look back on Aaron Burr, who proposed a municipal water system for New York City in the 18th century, but later as vice-president shot Alexander Hamilton. (04:25)

I Feel the Earth Move

View the page for this story

Climate change is doing more than melting ice sheets. It’s actually changing the Earth’s rotation. NASA’s Erik Ivins tells host Steve Curwood that the planet resembles a large top wobbling on its axis as the weight of ice lifts, but the wobble has no major effects for humans. (06:55)

Controversial Arctic Cruise

View the page for this story

Thanks to global warming, a 1000-passenger luxury cruise liner will travel through the fabled Northwest Passage in the Arctic for the first time this summer. Canadian legal scholar Michael Byers was invited to come along as a lecturer, but he declined because he is so concerned about climate change. He tells host Steve Curwood that tourism in the Arctic is dangerous and too much ecotourism could threaten the ecosystem and the people who live there. (10:15)

BirdNote: Spider Silk and Birds’ Nests

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

In nesting season, ingenious birds make use of many objects they find to construct a snug home for their eggs. But as Michael Stein reveals, some small birds like kinglets and hummingbirds have found that spider silk collected from webs is just the thing to hold nests together, the bird equivalent of duct tape. (02:00)

Revisiting Africa’s Great Green Wall

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

As human activity puts pressure on land in Africa and the planet warms, the Sahara desert threatens to overtake the arid Sahel region. But a bold initiative to plant a wall of trees 4,300 miles long across the continent could keep back the sands of the Sahara, improve degraded lands, and help alleviate poverty. We return to a 2012 Living on Earth story on the Great Green Wall, reported by Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb in Senegal. (05:00)

Great Green Wonder of the World

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Africa’s Great Green Wall is making slow progress, and helping provide employment to keep young people on the land. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer reports on the hopes for the project to help local economies and the environment. (05:30)

Elephant Matriarch Puts Her Foot Down

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

On a blistering day at an African watering hole, Living on Earth’s Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender witnesses a confrontation between basking crocodiles and a small herd of elephants seeking to quench their thirst. (03:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Erik Ivins, Michael Byers,

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Helen Palmer, Peter Dykstra, Michel Stein, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Young people have the right to sue the US government for failing to protect them from the future ravages of climate change, a federal judge in Oregon says.

PARENTEAU: If it goes to trial, it will be the trial of the century, it will outdo the Scopes trial, because you're going to have all kinds of climate scientists saying how grave the threat is, how little time we have to address it, and that would be a very interesting spectacle frankly.

CURWOOD: But legal scholars say it’s a long shot to get to trial.

Also, checking in on the Great Green Wall, an ambitious plan to keep the Sahara Desert in check as the Earth warms.

TANGAM: Great Green Wall is not only about trees. The Great Green Wall is about development, it’s about sustainable, climate-smart development, at all levels.

CURWOOD: That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

Youth Win Right to Sue Feds Over Climate Change

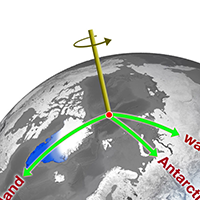

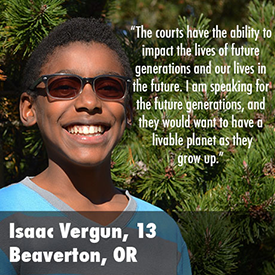

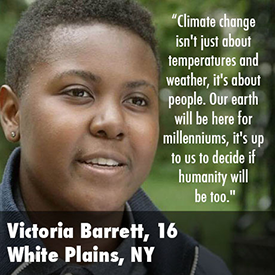

Victorious Children’s Trust plaintiffs after learning their climate suit can proceed (Photo: Our Children’s Trust)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. A federal judge in Oregon has found that 21 young people have the right to sue the federal government for failing to properly protect future generations from the dangers of climate change. In making this landmark decision Magistrate Judge Thomas Coffin in part took his cue from a lower court in the Netherlands that found the Dutch Government must act on climate change because of its existential threat to its citizens. The case now goes to US District Judge Ann Aiken, who will determine if and when there would be trial. We turn now to Pat Parenteau, Law Professor at Vermont Law School, to explain this case. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat.

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Steve. Good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So I'm looking at this order from the judge in this case, all 24 pages of it. I've never seen anything like this. How surprised were you?

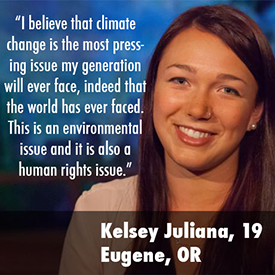

(Photo: Our Children’s Trust)

PARENTEAU: I was very surprised. This is a series of lawsuits that Our Children's Trust has filed across the country - some are federal courts, some in state courts - and in the past the children who are the named plaintiffs in the case have won some minor procedural victories but this one is more significant. This is the magistrate judge in Oregon whose decision then has to be referred to the actual federal judge in Oregon and it's Judge Aiken and she will have to actually decide whether to accept the recommendation of the magistrate judge, but Magistrate Judge Coffin has done something no other judge has been willing to do which is to recognize that the youthful plaintiffs have a potential constitutional claim that the United States government is falling down in its duty to protect the younger generation from the threats of climate change going forward.

CURWOOD: Let's tease apart upon some of the legalese here. Now when you say constitutional claim, what does that mean in plain language?

(Photo: Our Children’s Trust)

PARENTEAU: They're claiming a due process right based in the ninth amendment. This is the same amendment that has given rise to the right to privacy, to marriage equality, to a variety of individual rights not spelled out in the constitution, but contained within what's called the penumbra of the ninth amendment so that's what this judge is relying on. He's relying on case law from the Supreme Court that recognizes there are certain unwritten rights in the Constitution that come to light, if you will, as judges evaluate threats to American citizens, and in this case the judge is saying because the young population of the country will suffer the worst effects of climate change, they need to have their government respond by of course reducing the carbon pollution that is causing climate change now because they won't have the ability to do that in the future.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about the elements of Judge Coffin’s decision here. First he says that the kids have standing, and really a special standing because they're young folks. Can you explain that please?

PARENTEAU: The youth are saying they are harmed in ways that are different than, let's say the older population of America, which won't live long enough to see the worst consequences. So that's what makes this both a fascinating case and a really difficult case for the courts to deal with. The plaintiffs here, the children are saying, we're a special class when it comes to climate change because the only way for us to avoid the effects we're going to feel is if efforts are stepped up now to reduce carbon pollution.

(Photo: Our Children’s Trust)

CURWOOD: What are the plaintiffs seeking to have the federal government do in this case?

PARENTEAU: They've asked for a very broad range of remedies. They've asked specifically that the government cancel contracts to export gas from an LNG, a liquefied natural gas terminal in Oregon. That's one of the most specific things they've asked for, but they've also asked that the government do an accounting for the greenhouse gas emissions that are occurring, and what is the government doing to reduce those emissions over what period of time. And they're actually asking that the court order the government to reduce the loading of carbon in the atmosphere down to the 350 parts per million level that's been recommended by several scientists including James Hansen, who is named as a guardian in this case for the children. So they're asking for an extraordinary relief never before ordered by a court telling the government to begin reducing carbon emissions and literally bring them down to a point where there is no longer at least a serious threat from climate change.

CURWOOD: And how is the government supposed to do this according to the plantiffs?

(Photo: Our Children’s Trust)

PARENTEAU: Well, they don't spell that out. They are basically asking for a plan, and the question, of course, is who would provide that plan - the President, the Congress, those are all questions. They're problematic questions, frankly. I think the courts are going to have a hard time ordering the United States government to take the steps that the plaintiffs are seeking and it may be that the real value of a case like this is to elevate this issue in the court of public opinion certainly with an election coming up, and try to get the elected politicians to respond to this. They're seeking a court order, but I have my doubts that a court is going to order the kind of relief they're asking for.

CURWOOD: And what's the major reason you think that this will fail ultimately?

PARENTEAU: In the courts I think the separation of powers between the executive branch, the legislative branch and the judicial branch is a real barrier to a case like this. It's not a traditional function for our courts to be ordering this kind of broad scale economic energy policy that's really economywide. And it's also the case that even if the United States of course were to do everything it could to reduce its carbon pollution...unless the other major emitters in the world do likewise it won't accomplish the purpose. That's another reason why I think courts are going to be reluctant to be imposing duties on the executive and legislative branches of government where this is a global problem that requires a global solution.

CURWOOD: What about the question of a constitutional right to be free from CO2 emissions that’s in this case?

PARENTEAU: Well, you know, there have been courts that have recognized the right of bodily integrity, which means that you have a right to be free of contaminants or threats to your health that would emanate from activities that were either permitted by the government or perhaps not permitted and should be permitted. And it's in that vein, I think, that this judge is referring to the threats of climate change as being not only a threat to the bodily integrity of these young plaintiffs, but even more fundamentally that this is threatening the very viability of ecosystems to provide food and shelter and so forth for citizens. In that sense it's at the outer edges certainly of constitutional theory, but the idea that American citizens should be protected from an existential threat like climate change is not really that far-fetched. It is after all the fundamental duty of government to protect the citizens from existential threats and that's exactly what climate change represents.

CURWOOD: So what happens here going forward, do you think? What will happen next?

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School (Photo: courtesy of Vermont Law School)

PARENTEAU: Well I think that Judge Aiken has a big decision to make as to whether to accept the recommendation of the magistrate judge or whether to hold further hearings in argument or maybe accept a part of what Magistrate Coffin has said and not all of it. So that's the next step. Assuming that Judge Aiken accepts those recommendations, then the next step will be will the government file a motion for summary judgment in which they can argue, “you no longer should accept what the plaintiffs are saying as true. We're going to introduce affidavits to counter what the plaintiffs are saying.” For example, they're going to say “the government is taking lots of steps to address climate change. It's not true that we're just sitting on our hands, certainly not true of the president.” So we'll have another round of argument, I think, and maybe the case will get resolved on summary judgment and maybe not. If it goes to trial, it will be the trial of the century. It'll outdo the Scopes trial because you’re going to have all kinds of climate scientists coming in saying how grave the threat is, how little time we have to address it, and that would be a very interesting spectacle, frankly.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a professor from Vermont Law School. Thanks for joining us today.

PARENTEAU: You're welcome, Steve.

Related links:

- Press Release from Our Children’s Trust

- Our Children’s Trust

- Watch a video of young people responding to legal victory

- About Pat Parenteau

Beyond the Headlines

A captive tiger at a zoo in Bridgeport Connecticut (Photo: Animal People Forum, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some stories fit to print don’t make it onto the front page – and those are the ones that Peter Dykstra searches out beyond the headlines. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org and joins us from Conyers, Georgia. Hello, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. I’ve got some good news again this week.

CURWOOD: Uh hey, that’s two weeks in a row for you ... you feeling OK?

DYKSTRA: I’m feeling fine and I’ve got a survey from the World Wildlife Fund. Several Asian governments and conservation groups and together they report that tiger populations are on the rise in Asia after a century’s worth of decline.

CURWOOD: Now that is some good news, but tigers are hardly out of the woods, or should I say, out of the forests of the night.

DYKSTRA: Oh not at all. The count is 3,890 tigers, up from about 3,200 six years ago. But consider that in 1900 it was a hundred thousand wild tigers in Asia. And here’s a number that really shocked me: there are far more captive tigers alive today than wild ones – at least 5,000 alone in the U.S. in zoos, circuses, wildlife ranches and private menageries.

CURWOOD: That is kind of surprising. But what do you think are the reasons for the increase in the wild?

DYKSTRA: Well there’s better wildlife protection, a slowing of habitat loss, and a commitment by Asian nations including Russia, China, and India to try and double wild tiger populations. There’s another recent Google-Earth-based study has measured both the loss and the protection of tiger habitat, identifying key habit areas because even if we want tigers out of the woods, we don’t want them out of the forests.

CURWOOD: Unless they’re in zoos. Hey, what’s next?

DYKSTRA: Well here’s a tale of two cities and their respective dealings with lead contamination. Fifteen years ago, Madison, Wisconsin launched an ambitious project to eliminate lead drinking water pipes from the city. It cost just under $20 million to remove lead from 5,600 properties, with the owners footing about 20 percent of the bill.

Lead pipes call into question the safety of Philadelphia's drinking water. (Photo: Jakeline, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hey, that sounds relatively cheap.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but the estimate for doing the same thing in Wisconsin’s biggest city, Milwaukee, is at least half a billion dollars to swap out 70,000 lead water lines. But onto another lead story from another city.

CURWOOD: OK.

DYKSTRA: As with many big cities, Philadelphia’s school system is facing enormous challenges over budgets and the infrastructure of aging schools. As early as 1993 the city knew its schools might have a lead problem and while it took a few years and some pressure from health officials, by 1999 Philadelphia’s schools started to get the lead out. They removed some lead pipes, dismantled some water fountains and painted do not drink sign over bathroom sinks.

CURWOOD: So the problems are all solved in Philly?

DYKSTRA: No but let’s call it mixed results. Things may be better, but this is hardly a shining success. The Philadelphia School Board knew, but didn’t tell anyone about the lead issues for six years at first. And when they did, one report says EPA testers were blocked from entering schools to do their jobs and find out how bad the problems are. Those “Do Not Drink” signs are still up in many schools and when the water fountains were removed, some were never replaced, leaving kids with few places to get a drink of water at school.

CURWOOD: And that shows just how hard to fix those problems can be, particularly for governments and school systems that are a bit short on cash. Hey what do you have us from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: Let’s take you back to April, 1799 in New York City. A group of citizens headed by a future Vice President got together to create a financial firm and launch an ambitious project – a centralized water system for the growing city. It was called the Manhattan Company, and it was the origin of not only one of the largest drinking water systems in the world, but the financial side evolved into today’s giant J.P. Morgan Chase.

Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr’s famous duel was preceded by their financial competition. (Photo: From a painting by J. Mund. [Public domain], Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Hmm, the New York water system and JP Morgan Chase – two things that are too big to fail. Who was the Vice President?

DYKSTRA: The one and only Aaron Burr. The big financial competitor for Burr’s Manhattan Company was the Bank of New York, founded by Alexander Hamilton, who had been George Washington’s Treasury Secretary. The Bank of New York also eventually got swallowed up by JP Morgan Chase. Now of course, Burr and Hamilton didn’t like each other very much. Five years later at a spot not far from the modern day Jersey end of the Lincoln Tunnel, Burr killed Hamilton in a duel.

Hamilton today is the subject of a Broadway musical and model for the ten dollar bill; Burr finished out his term, but was a pariah best known today for being tied with Vice President Cheney as having shot the most people while in office.

CURWOOD: And I thought modern-day politics was a bloodsport! Peter Dykstra’s with Environmental Health News and the Daily Climate.org, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. Thanks Peter, we’ll talk to you again next time.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve. Thanks, we'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “Wild tiger numbers are up for the first time in a century”

- The Guardian: “Forests still large enough to double the world’s tiger population, study finds”

- WisconsinWatch.org: “First in the nation: City of Madison replaced all lead pipes”

- The Guardian: “How Philadelphia schools’ vast effort to rid water of lead went under the radar”

- About Aaron Burr’s Manhattan Company

[MUSIC: Tony Allen, “Asiko,” PRI’s The World Presents Global Hits: Beats (Originally on Black Voices), PRI (Originally published by Comet Records)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from Wunder Capital, an online investment platform that allows individuals to invest in solar projects across the U.S. More information and account creation at Wunder Capital.com That's Wunder with a 'U'. Wunder Capital, Do well and do good.

CURWOOD: Just ahead...NASA scientists explain how climate change is also changing the rotation of the planet itself. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Geoff Muldaur, “Chevrolet/Big Alice,” The Secret Handshake, Ed and Lonnie Young/Don Pullen, Hightone Records]

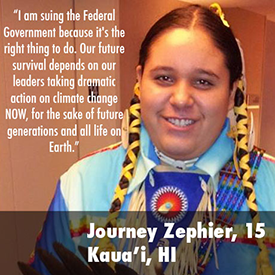

I Feel the Earth Move

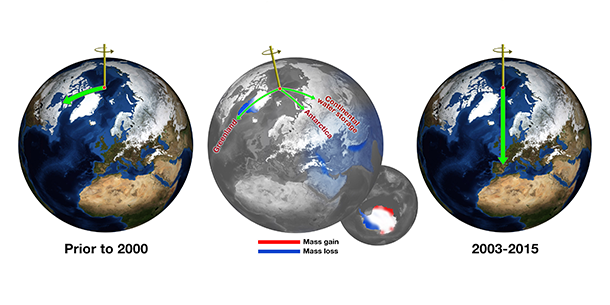

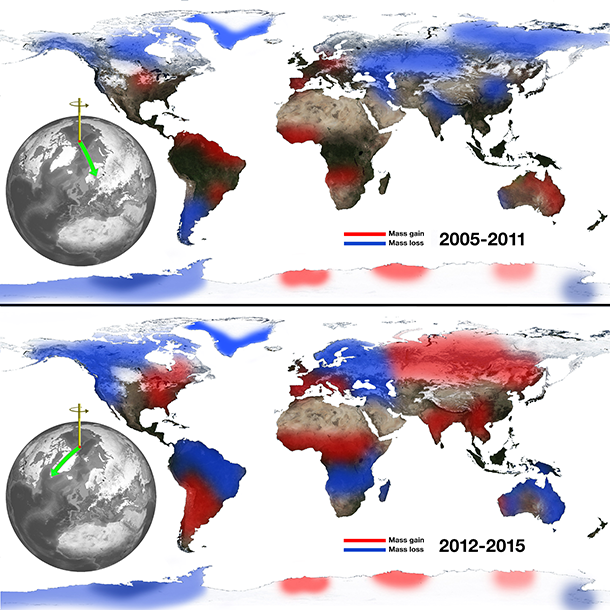

Before about 2000, Earth's spin axis was drifting toward Canada (green arrow, left globe). JPL scientists calculated the effect of changes in water mass in different regions (center globe) in pulling the direction of drift eastward and speeding the rate (right globe). (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. As global warming advances, there are profound effects on our planet, with heat waves, melting ice sheets, sea level rise, and changes in rainfall and storm patterns. And now a new study from NASA published in Science Advances points to an unexpected result of all that ice in Greenland and Antarctica melting and running off into the oceans: it’s moving the axis of rotation of the entire planet. This wobbling was first noticed by Jianli Chen of the University of Texas at Austin. And to try to understand this better we spoke with the co-author on the new study, Erik Ivins of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in his backyard in Pasadena. Welcome to the program.

IVINS: Thank you.

CURWOOD: I have to say I was surprised by the opening statement in your paper. You say the Earth's spin axis has been wandering since the year 2000. How can the axis which is just so fundamental to our planet wander?

IVINS: Actually, we know that it's been wondering for maybe about the last five million years at least, ever since the ice sheet started to build up in northern Canada and in Scandinavia periodically in periods of about a hundred thousand years, and as the ice sheets disappeared they left kind of a depression. It was sitting there. That's a mass deficit with respect to the average Earth and it causes the pole to want to wander in the direction of that little hole that's left there. So we do know that we have been recording the drift in that direction since about 1899 or so, but starting in about 1999 to about 2001 we started to see the Earth start to move in a new direction and that new direction really can only be explained by Greenland ice mass that is lost.

The relationship between continental water mass and the east-west wobble in Earth's spin axis. Losses of water from Eurasia correspond to eastward swings in the general direction of the spin axis (top), and Eurasian gains push the spin axis westward (bottom). (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

CURWOOD: Describe for me exactly what you mean by “the axis is moving”?

IVINS: Well, let's say that you have a toy top and you spin that top. When you start to spin the top since it's very symmetrical, it will tend to nicely form just a single axis of rotation. But if you were to take a tiny piece of chewing gum and stick it on there, you would find out that this spin axis would slightly tip over. That's because the body is no longer symmetric. It has an off axis piece of mass on it and it's causing the moments of inertia to change. And this is what causes this strange polar motion. Just to give you another analogy: let's say that you were a baseball pitcher and you were frustrated that too many of your hitters were being able to figure out what your pitches were doing. Well, you would use this old technique called "foreign substance", either pine tar or your own spit.

CURWOOD: This is not legal. This is not legal...a spitball, doctor!

IVINS: All the hall of famers are spitball pitchers. Now, what they're doing is they're changing the moments of inertia slightly so it changes the entire dynamical character of the pitch as it approaches that batter.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is located at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

CURWOOD: Makes it wobble and harder to hit.

IVINS: Well, it slightly changes the trajectory because the spin will change, and as the spin changes of course it tends to flutter around a little bit more in the eyes of the batter.

CURWOOD: So you folks are positing that human driven climate change plays a role in this wobble of the Earth axis but I understand initially that wasn't your hypothesis. It wasn't what you were looking for. What led you in this direction?

Dr. Surendra Adhikari and Dr. Erik Ivins of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory researched how the movement of water around the world contributes to Earth's rotational wobbles. (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

IVINS: Well, we were looking to build a software capability to connect calculations of ice sheet change so that we can project ice loss or gain for a period of about 200 years and try to predict what global warming will do to sea level rise. To improve that situation, we needed to include the Earth's dynamics and gravitational effects that the ice changes would have on global seas. Then as a way of being able to do a reality check, we looked both that the work that Jianli Chen had done on Greenland and we also looked at the actual raw data that was coming from the international rotation service and we found it was pretty close match especially when we included the details of Antarctica. And we also decided that it would be interesting to use the Grace mission data that determines how masses are changing on the surface of the Earth to include land hydrology. And once we included land hydrology, we found a near perfect match to the position of the Earth's spin pull.

CURWOOD: And who is Jianli Chen?

IVINS: Jianli Chen is a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin. He is also an expert at hydrology and Grace, and he's the first person that really published a nice paper explaining what the new drift direction was and that the Greenland ice loss was dominating this new direction.

CURWOOD: Wow. By the way, what is Grace? What's the Grace satellite?

IVINS: Grace satellite is a pair of satellites that follow one another and track one another, and they do such a good job of tracking one another with microwaves that they can tell when they separate and when they get closer to one another. And when they get closer to one another and then separate again they're going over a mass anomaly and they're so sensitive that if there is a change in water underneath them they record that and then map that very, very well.

CURWOOD: This is so interesting. What do you think of the practical effects of the movement of the Earth's axis?

Dr. Erik Ivins co-authored the recent paper, “Climate-driven polar motion: 2003–2015,” published in Science Advances. (Photo: courtesy of the Keck Institute at Caltech)

IVINS: There are really none because it is so small. We're suspecting that these changes are occurring at a meter, a meter and a half at the most per year. If you start to get up to about 100 kilometers, then you're changing the amount of solar radiation that's coming into some parts of the Earth so that can only occur and be of significance when we're thousands and thousands of times larger in terms of our scale.

CURWOOD: So this is a tremendous wake up call, I guess for our civilization that anthropogenic human related climate disruption is actually changing how the Earth is rotating.

IVINS: Yeah, I guess you could say that. I think one of the things that Jianli Chen mentioned was it's just another strange thing that the climate does. It doesn't have a feedback that is necessarily important for us, but it is just one of those things you can list on that list of "Oh my God! climate change really does that one?” Well, this is yet one of those.

CURWOOD: Erik Ivins is a senior research scientist at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Thanks so much for taking the time with us, Eric.

IVINS: OK, thank you, Steve. It's a pleasure talking to you.

Related links:

- “Climate-driven polar motion: 2003–2015,” in Science Advances

- Video: Nasa’s Earth Minute: Greenland Ice

- NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at California Institute of Technology

- “NASA Study Solves Two Mysteries About Wobbling Earth”

Controversial Arctic Cruise

Crystal Cruises’ new luxury vessel will embark on a trip through the Bering Strait and Northwest passage in a trip that begins in Alaska and docks in New York City 32 days later. (Photo: Reeve Joliffe Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The loss of sea ice in the high north is also changing the economic life of the planet with new shipping lanes, chances for oil exploration, and tourism. This fall Crystal Cruises will run a 1,000 passenger cruise ship on what they’re calling the Northwest Passage expedition through the Arctic Ocean. Joining us to discuss the trip and the prospects for Arctic tourism more generally is Michael Byers, the Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia. Welcome to Living on Earth.

BYERS: It's good to be here. Thank you.

CURWOOD: Hey, tell us a little bit please about this cruise. What kind of a ship are we talking about and what's the route?

BYERS: Well, we're talking about the world's most luxurious cruise ship. The Crystal Serenity is going to sail from Anchorage, Alaska, to New York City around the northern coast of North America through the fabled northwest passage, through the 19,000 islands that constitute Canada's high Arctic. The voyage will take a month and it will cost each passenger between $25,000 US dollars all the way up to $120,000 for one of the top suites. It's going to be quite a trip.

Trade and tourism in the Arctic have become a point of interest in recent decades as portions of the region that were previously frozen have begun to melt. (Photo: Gary Bembridge, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, and how unprecedented is? I mean how many ships have done this route before?

BYERS: Well, no cruise ship the size has done the route before. There have for a number of years been smaller so-called expedition cruise ships that carry 100 or 150 passengers. There have been a few large cargo ships that have made the voyage, and of course, Coast Guard icebreakers from Canada and the US have done so, as well increasingly as so-called adventurers in private yachts upwards of 25 or 30 a year, but no cruise ship of this size. These 1,000 passengers have very large cabins, they're being cared for by 650 crewmembers. They're even bringing a support ship along that has its own helicopter, so it's a major enterprise and I was in fact invited to go on board the Crystal Serenity as a lecturer and after considerable thought, two months ago turned the trip down.

CURWOOD: Why? Why did you say no? It sounds like a great trip.

A voyage through the Northwest Passage could offer a chance to see threatened species like the polar bear (Photo: LWP Kommunikáció, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BYERS: Well, a couple of reasons, the most significant being I've become increasing concerned about climate change and to be entirely open I've done the trip before on Canadian Coast Guard ice breakers, and on one occassion on one of these smaller expedition cruise ships, and I thought about whether I needed to be part of this trip. First of all because the ship has a pretty large carbon footprint so it's contributing to climate change by going to the Arctic and also the fact that this trip is a form of so-called extinction tourism. The only reason that the passengers can go to the Arctic is because the Arctic is on the edge of a precipice, the sea ice is melting and the ecosystem is being overturned. It's a little bit like going to see an endangered species on the savannah of Africa or the Galapagos Islands because you don't think it will be there in five or 10 years and I again found that a bit perverse and decided I could not personally go. Now, I'm not criticizing those people who choose to go. Again, I've been...I've already seen it. I don't need convincing about the reality of climate change.

CURWOOD: I'm also wondering about the impact of such a tour ship. I mean, you go to place like Nome, Alaska, and you know how big Nome is. It's not exactly...I mean a snowball maybe you could throw from one end of downtown to the other almost. How can Nome handle 1,000 people disembarking there?

A US Coast Guard ice breaker in the Beaufort Sea (Photo: NASA, CC BY 2.0)

BYERS: Well, that's a question for the residents of Nome, Alaska, and also for the three small aboriginal communities in Canada's high Arctic where the ship will stop. And certainly the cultural impact could be severe, the environmental impact on the local wildlife could be significant. But that's a decision that the residents need to make. There’s a more problematic issue in terms of the impact on the marine ecosystem as this large ship passes through. For instance, there are many whales in the Arctic - Bowhead whales, Beluga whales, Narwhal - and these whales are highly sensitive to noise because they communicate using sound and if you have large ships passing through this can disrupt the whales while they're calving, while they're mating, and so that's a concern. There's also a potential risk of an oil spill, and I don't want to overstate it with regards to the Crystal Serenity because the Crystal Serenity is very well-managed. But any large ship will have hundreds of thousands of gallons of fuel oil on board and oil in cold water degrades very slowly. So if you remember the Exxon Valdez and you transfer that situation to the high Arctic you have a situation that's even worse.

CURWOOD: Well, I'm also wondering about basic safety for those thousand passengers. If something goes wrong - I know Crystal cruises as you say it is very well run, but it's a human invention so things can go wrong. How the heck do you get 1,000 people out of the high Arctic if there's a problem?

The cruise ship will stop in Nome, Alaska and several indigenous towns (Photo: Dan Perez, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

BYERS: Well, you might not be able to do so, and even though the ship is passing through the Arctic during the late summer, I have sailed the same waters in the summertime in 20 foot waves, in gale force winds. So, there are risks and search and rescue capacities in the Arctic are very stretched. Canada bases its search and rescue helicopters in southern Canada on the west coast and on the east coast, it can take them up to two days to get to the northwest passage, so we're talking about very poor search and rescue coverage and real dangers from shallow uncharted waters, from the increased existence of icebergs in these waters. This is actually one of the ironies of climate change. Although the sea ice that forms on the surface of the water in the winter, although that is diminishing, the number of icebergs is actually increasing as climate change melts the surface of land-based glaciers, and that meltwater lubricates the motion of the glaciers into the sea and small chunks of icebergs called growlers are very, very hard to see because they're very dense, they floating on the water and they can punch a hole in the hull of a cruise ship. In fact, a decade ago a small expedition cruise ship sank in Antarctica after striking a growler, and if the Crystal Serenity were to have that kind of accident happen in the Canadian Arctic, well, quite frankly, I would not want to be on board.

CURWOOD: You are perhaps alluding to the first passage of a major large super-large ship more than a century ago. Sounds like this could end up like the Titanic?

BYERS: Well I don't want to exaggerate the risk. Again Crystal Cruises is a very good company. Passengers pay an awful lot of money to have the highest standards of safety so this ship will probably be OK. My biggest concern about cruise ship safety actually involves the other ships that will follow in subsequent years. Crystal is going to open this door and Holland America and Disney and Costa are

all going to come through in the future because it's a place that people want to visit, that they want to see, and all of your listeners will remember the Costa Concordia which crashed onto the rocks along the coast of Italy a few years ago. The Canadian Arctic, the north coast of Alaska is infinitely more dangerous than the coast of Italy.

One of the concerns with the trip is that rescue would be very difficult in the high Arctic if an accident were to occur (Photo: Lin Padgham, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So you say that we're likely to, after this voyage, we'll see many many more. How should this industry be regulated?

BYERS: The first thing is that people should be making informed choices as to where they go on vacation. I personally think that if we're concerned about climate change perhaps we should fly less, perhaps we should stay closer to home. In terms of what governments could do is to make sure that the strictest safety standards apply to these voyages. So to give you just one simple example: ships that are sailing within the coastal waters of the United States and Canada on the Pacific or the Atlantic coasts are required to use low-sulfur fuel to reduce the amount of air pollution. That's not the case in the American or Canadian Arctic and this is a real problem because that high-sulfur fuel produces a lot more particulates which when they land on ice or snow darken the surface, absorbs more solar energy, and accelerate the melting process. Now, coming back to the Crystal Serenity, again, Crystal is a good company. They are voluntarily using low-sulfur fuel for this voyage, but the ships that follow might not do so, and the US and Canadian governments are not requiring that they do so.

CURWOOD: Michael, by the way you wrote a book called "Who owns the Arctic?" So tell me, who controls this territory and what laws would apply to companies who are trying to do business in the high Arctic?

Michael Byers is a the Canadian Research Chair in Global Politics and international law at the University of British Columbia and author of the book, “Who Owns The Arctic?” (Photo: courtesy of Michael Byers)

BYERS: Well, Canada and the United States dispute the legal status of the northwest passage. United States says that, “yes it's Canadian waters but there's almost an easement through Canadian waters that enables foreign ships to enter with very little restriction.” Canada objects to that, says, “no, this is a situation of internal waters were the full force of Canadian law applies.” One of the things that the voyage of the Crystal Serenity should be saying to politicians in Washington and Ottawa is that the northwest passage is now opening, we can't afford to have a diplomatic dispute between these two countries. I've been making this pitch for a long time and governments don't listen to me, but the whole point is the Arctic is opening. Climate change is real. These waters are becoming busy and governments need to get their act together to protect the environment while we still can.

CURWOOD: Michael Byers is the Canada research chair in global politics and international law at the University of British Columbia. Thanks so much for taking the time.

BYERS: It's been a great pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- “Who Owns the Arctic?” by Michael Byers

- About Crystal Cruises

- Read Susanne Goldenberg’s op-ed in the Guardian about Arctic tourism

BirdNote: Spider Silk and Birds’ Nests

Some hummingbirds and kinglets use spider webs in the construction of their nests. (Photo: Andy Teucher)

[MUX - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: At my house we know it’s spring when ducks swoop down to our pond for a quick bite to eat on their way North, and phoebes show up to build nests under the eaves of the house. And as Michael Stein explains in this BirdNote®, for some species, nest building can involve ingenious repurposing, the bird version of reduce, reuse and recycle.

http://birdnote.org/show/spider-silk-duct-tape-bird-nests

BirdNote®

Spider Silk and Bird Nests

A spider’s web is an intricate piece of precision engineering. And the spider silk it’s constructed with is amazing. Made from large proteins, it’s sticky, stretchy, and tough. So it’s no surprise that many small birds make a point of collecting strands of spider silk to use in nest construction – birds like hummingbirds, kinglets, gnatcatchers, and some vireos.

[Golden-crowned Kinglet song, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/197096, 0.15-.19]

Golden-crowned Kinglets, among the smallest of songbirds, build a tiny, square nest. They often use strands of spider silk to suspend the structure from adjoining twigs, like a tiny hammock.

A tiny Anna’s Hummingbird sits on a nest held together by spider’s silk. (Photo: Steve Berardi)

[Ruby-throated Hummingbird squeaks, wing hum, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/176299, 0.13-.16]

When a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird is building her nest, she collects the spider silk she needs by sticking it all over her beak and breast. When she reaches the nest site, she’ll press and stretch the silk onto the other materials – such as lichen and moss – creating a tough, tiny cup. Spider silk not only acts as a glue, holding the other bits together, but it’s flexible enough to accommodate the growing bodies of nestlings. And it’s resilient enough to withstand all the bustle of raising those hungry babies.

[Ruby-throated Hummingbird squeaks, wing hum, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/176299, 0.13-.16]

Where we might reach for duct tape, these birds turn to spider silk.

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Golden-crowned Kinglet [197096] recorded by Bob McGuire; Ruby-throated Hummingbird [176299] recorded by G A Keller

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2016 Tune In to Nature.org April 2016 for Living on Earth Narrator: Michael Stein

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2658765/

http://birdnote.org/show/spider-silk-duct-tape-bird-nests

CURWOOD: Duct tape! Who’d a thunk it? For more flap on over to our web site – where you’ll find – not spiders, but photos.

Related links:

- Read more on the BirdNote website

- More unique bird nests

- Listen to the Anna’s Hummingbird and other bird songs on the Macauley Library website

- Study: The elaborate structure of spider silk: structure and function of a natural high performance fiber

[MUSIC: Geoff Muldaur, “Chevrolet/Big Alice,” The Secret Handshake, Ed and Lonnie Young/Don Pullen, Hightone Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a frontline in the fight against climate change – the Great Green Wall of Africa. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Luminescent Orchestrii, “Kombucha Monster,” Neptune’s Daughter, Rima Fand, Nine Mile Records]

Revisiting Africa’s Great Green Wall

Women plant and take care of a dozen different vegetables in their gardens. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. To mark Earth Month – yes at Living on Earth, we believe our only planet deserves more than just a day – we’re celebrating by catching up on the progress of some stories we covered in the past. Today, we head to Africa, through a story Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reported on back in 2012 – the ambitious plan to build a Great Green Wall of trees, at least 9 miles wide, to stretch more than 4,000 miles across the continent. The Great Green Wall is designed to encourage sustainable development and keep the Sahara desert from advancing further south as the planet heats up. And when it is finished it will cross 11 countries from Senegal and Mauritania in the west to Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti in the east. Bobby reported from a village in the arid Sahel in Senegal where trees were already being planted to hold back the desert.

BASCOMB: The Peuhl are the dominant ethnic group in the Senegalese Sahel. Extremely tall and lean, they wear long flowing robes of emerald green and sapphire blue. They look like jewels against the rust colored sand and brown dry grass.

Traditionally nomadic, the Peuhl are now helping tend to the trees…. and gardens. One day a week women in the area volunteer to help care for gardens full of carrots, cabbages, tomatoes, even watermelon. On this day a group of women, including Guncier Yarati, is using the sides of their flip flops to mound the sandy soil around potato plants.

Women mound the dry dusty soil around their potato plants (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[SOUNDS OF SCRATCHING WITH FLIP FLOPS]

[SOUND OF WOMEN WORKING / LAUGHING UNDER]

YARATI: I like working here. I like working with my friends. We laugh and play while we work but what’s really great is that we have more diverse vegetables. We eat the vegetables and can sell them in the market as well.

BASCOMB: The closest market is about 30 miles away and before the gardens came along it was a day’s trek in a horse drawn cart to get fresh vegetables.

[WATERING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Most of the gardens are watered using drip irrigation. A hose with holes in it delivers just the right amount of water to each plant to minimize evaporation loss but some plants are watered by hand.

[SOUNDS OF FILLING WATER CANS]

BASCOMB: The women dip large plastic cans into a basin filled with water from a nearby well. Nime Sumaso pours her jug of water over some carrots.

[WATERING SOUND UNDER ACTUALITY]

SUMASO: When people came from Dakar and showed us that they could plant vegetables in their center we saw that it was a way to help women in the community so we knew the Great Green Wall project was important for us.

BASCOMB: It’s exactly that kind of community support that the government is hoping to garner. While women here mostly see benefits of the project in their gardens, the men have a different perspective.

[COW SOUNDS, WATER TOWER SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: In the early morning white hump-backed cows with giant horns gather around water troughs. The Peuhl depend on their large herds of cows and goats for subsistence…. and livestock need a lot of water. French colonizers built water wells every 20 miles in this region. In an area that gets as little as 6 inches of rain each year, water is life.

[DONKEY CART SOUNDS THEN WATER TOWER AND COW SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Scientists say the trees of the Great Green Wall will improve rainfall and recharge the water table. That pleases Alfaca, a local herdsman.

ALFACA: Planting trees is good for us. Those trees can bring water and water is our future. Water can solve our problem. We are praying for this project to continue.

Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb interviews a local herdsman called Alfaca. (Photo: Mark Fabian)

BASCOMB: Roughly 40 percent of Africa is affected by desertification, where non-desert land turns to desert. The United Nations says two-thirds of Africa’s arable land could be lost by 2025 if the desertification trend continues.

Everyone involved in the Great Green Wall agrees that the end goal is to help rural communities. But opinions vary on how the project will do that. African leaders envision the Great Green Wall as a literal wall of trees to keep back the desert. That’s what was proposed by the president of Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo, when he came up with the idea in 2005. But scientists and development agencies see it more as a metaphorical wall… a mosaic of different projects to alleviate poverty and improve degraded lands.

SINNASSAMY: Sustainable management of natural resources with the aim of reducing poverty, this is really our goal for this program.

BASCOMB: Jean-Marc Sinnassamy is a program officer with the Global Environment Facility, one of the funders of the Great Green Wall.

SINNASSAMY: We do not finance a tree planting initiative. It’s more related to agriculture, rural development, food security and sustainable land management than planting trees.

Related links:

- Listen to the full original Living on Earth story on the Great Green Wall

- Read Bobby Bascomb’s blog from Senegal

- The Global Environment Facility on the Great Green Wall

- Scientific American on the Great Green Wall

Great Green Wonder of the World

The Sahel is a semi-arid transitional zone between the Sahara desert and the Sudanian Savannah. (Photo: Daniel Tiveau / Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: That’s Jean-Marc Sinnassamy of the Global Environment Facility, that helps fund the Great Green Wall, in Bobby Bascomb’s report from 2012. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer has been checking out what’s happened since then.

PALMER: For those in charge of making this ambitious dream a reality, it’s not just about planting trees to hold back the desert. At the Paris climate talks, I met up with Elvis Paul Tangam, the African Union Commissioner for the Sahara and Sahel Great Green Wall Initiative.

TANGAM: Great Green Wall is not only about trees. The Great Green Wall is about development, it’s about sustainable, climate-smart development, at all levels.

PALMER: Development at all levels means sustainable land management to provide jobs and cash, to keep people in their communities and able to thrive in a harsh climate. Tangam says it’s a matter of life or death for millions, particularly young men.

TANGAM: It’s about value. The issue of migration, which is very fundamental because it is the nexus between migration, land degradation, poverty. Every young person wants to be valued. In the African context, every young person, especially young man, has the responsibility to take care of their family.

The Sahara desert is encroaching on the Sahel (Photo: Antonio Cinotti, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PALMER: Tangam says idle young men, who’ve seen crops and animals die and have no work, face terrible choices. They might join rebel groups, or terrorist groups like Boko Haram or join the exodus of desperate migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean on rickety boats to find work in Europe. Although the idea of the wall of trees is a decade old, it remains more vision than reality. Yet Tangam says a lot has been achieved in terms of cooperation.

TANGAM: The first biggest achievement of the Great Green Wall is the fact that people of those regions have accepted to work together, for a common goal. The second achievement is that each of those countries developed national action plans. That is the biggest achievement because now they own it. It’s about ownership, and that has been the failure of development aid because people were never identified with it. But this time they identify, this is our thing.

PALMER: But there has also been success on the ground - according to Tangam. About 15 percent of the actual “wall of trees” is already planted.

A child refugee displaced by Boko Haram. Tangam says that the job creation spurred by the Great Green Wall may help prevent young Africans from turning in desperation to terrorism. (Photo: EU/ECHO/Isabel Coello, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

TANGAM: Senegal has reclaimed more than four million hectares of land along the Great Green Wall. They have planted more than 27,000 hectares of indigenous trees, that don’t need watering. All animals that had disappeared from those regions are reappearing – animals like antelopes, we are talking about hares, we are talking about birds that for the past 50 years nobody saw.

PALMER: The United Nations commissioned a virtual reality film to show the progress so far – it features the Fulani people at a village called Koyli Alpha.

CHILD: Already our well is filling up. And now my mother doesn’t have to walk for hours to get water. There’s more work for everyone, and the market is busy again.

PALMER: And Tangam says it’s not only Senegal, there’s progress in Mauritania, in Chad, Niger, Ethiopia and Nigeria, where they’ve developed market gardens and grow fodder to feed animals in the dry season, giving the young population work.

Elvis Paul Tangam at the November 2015 Paris climate talks, where the Great Green Wall Initiative set up a station with virtual reality goggles to watch an immersive video about the project. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

TANGAM: You see that many young people who probably would have been joining the Boko Haram, they are now part of either the firefighting brigades, they are now part of the Great Green Wall brigade, and they are in their communities because they have a source of income and they are putting value to their lives.

PALMER: And, according to Tangam, another hopeful sign is the money to pay for this huge project – last December the UN climate meeting brought firm pledges of additional funding for the Great Green Wall.

TANGAM: We have, generally, $4 billion dollars of pledges, which is a lot of money! And we are going to get them. The French government said, we are going to increase our investment in climate resilience and programs by 2020 by one billion euros. The President of the World Bank said, they’re going to give $1.9 billion dollars for Great Green Wall and other related programs.

PALMER: Still, the UN says that 100 million Africans are threatened by growing desertification as the climate changes and the worst drought in 30 years affects parts of the continent. That makes any project such as this, that Africans claim as their own and believe in, both more vital and more likely to succeed.

[VIDEO MUSIC FADES IN]

CHILD: My grandfather says that all of this here is part of a Great Green Wall that will stretch across Africa. He says it is going to be a wonder of the world.

PALMER: Though, as Elvis Paul Tangam and all the stakeholders agree – to realize this wonder of the world will take at least a generation. For Living on Earth I’m Helen Palmer.

[MUSIC FROM THE UN GREAT GREEN WALL VIDEO]

Related links:

- About the Great Green Wall Initiative

- Video: “Growing a World Wonder” (virtual reality film)

- Scientific American on the Great Green Wall

Elephant Matriarch Puts Her Foot Down

The thirsty elephants seek out water on a blisteringly hot day (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: There’s a savage drought in parts of southern Africa, and that’s putting extreme stress on wildlife. But our Resident Explorer, writer Mark Seth Lender discovered that at a waterhole in Zimbabwe, even when water is scarce, animals have learned to keep the peace.

Restraint © 2015 Mark Seth Lender All Rights Reserved

LENDER: The crocodiles are lying in a circle at twelve, at five, at nine o’clock. They surround the only waterhole with water in it, an immobile, unbreachable line. Just off center a hippo lounges half-imbedded in the mud. He humps up out of the water like a boulder.

It is late afternoon.

The sky is white.

The heat is beyond description.

The elephant herd heads for the watering hole at a run (Photo: courtesy of Donald Young Safaris)

Out of the wavy distance a small herd of elephants appears. They already know there is water here but as the smell of it reaches them, they break into a silent dumbling run. At the bottom of the slope, they hold back. They have seen the disturbing clockwork and there is a baby with them, only the one. He looks out from between the legs of the others, sheltered by mothers and aunts. They stand like tree trunks, waiting, despite their thirst, which by now is all they can think about..… except for the crocs.

The matriarch breaks off from the herd. She walks up to Five O’clock and stops. Straightens her neck. Lifts her chin. Looks at the crocodile as if over a pair of pince-nez; a look intended as a warning which the crocodile… ignores.

PMFFF!

A foot that is half a meter in diameter lands three minutes on the gauge from his face.

The matriarch steps back. She tilts her head and looks at him sideways...

A layer as fine as chalk settles on his nostrils, and jaw, and the hooded sockets of his immovable eyes.

When a crocodile refuses to move, the elephant matriarch puts her foot down with a loud thump. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

WHUUUMMMP!

This time the distance is measured in a clock-tick and the crocodile’s big boney skull bounces, raising its own drab puff of clay.

The Matriarch looks down.

And the crocodile… rises (just enough to let him move) and slips, into the water, slowly. Very… slowly. His tail, sculling side to side pushes him away from the banks towards the center, preferring the considerable risk of hippo to the imminent threat of Elephant.

The herd comes closer.

The matriarch continues in her deliberate precession. Step by step she clears out Nine, then Noon, and the elephants unfurl their trunks and drink their forty gallons each of what passes for water in this fetid season of the year in southern Africa. One of the females stands with the baby, and he also drinks and bathes as well as he can and they spray the muddy stuff over themselves, and him, and then go back the way they came under the red dust sun, that is hot, and unforgiving as it will be for at least another month of hardship all around.

The land begins to cool after a hot, dry day in the African desert (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Light quickly fades.

The land begins to cool.

The crocodiles retake the positions they had before, marking their ancient place in time.

Again, the danger is them.

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender. There are some of his photographs of lumbering elephants at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Mark's fieldwork in Africa is conducted with Donald Young Safaris

- About Mark Seth Lender

[MUSIC: Kieran Kane/Kevin Welch//Fats Kaplin, “Mr. Bones,” Lost John Dean, David Olney/Claudia Scott/John Hadley/Kevin Welch, Dead Reckoning Records]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth: To mark Earth Day, countries will sign the Paris Climate Agreement, and its chief executive Christiana Figueres, says there is no time left to waste.

FIGUERES: We're five minutes to twelve. So the speed and scale of implementation is going to have to be pretty aggressive.

CURWOOD: Assessing the climate Agreement and more next time, on Living on Earth from PRI.

[MUSIC; Ann Hobson Pilot, “Berceuse,” ANN HOBSON PILOT: Harpist, Gabriel Faure, Boston Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Peter Boucher, Adelaide Chen, Jaime Kaiser, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Thanks this week to Donald Young Safaris. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. And Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. And from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth