August 12, 2016

Air Date: August 12, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Flint, A Poster Child for Environmental Racism

View the page for this story

Dr. Robert Bullard, the “father of environmental justice”, says that the lead water disaster in Flint, Michigan is just the latest example in a long history of environmental injustice in the United States. Dr. Bullard tells host Steve Curwood that the working class and communities of color like those of Flint are far more likely to be exposed to toxic substances like lead. (11:50)

Illuminating Fishing Nets Prevent Bycatch

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

Bycatch is an economic and environmental problem for commercial fishing. Large trawlers often scoop up sea-life other than the species they're targeting, and if there’s too much bycatch fishermen sometimes have to dump their catch. But Bob Hannah of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife may have found a simple, affordable solution. He tells Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald how local shrimp fishermen are eliminating bycatch of an important smelt species by lighting up their nets with LEDs. (06:55)

Calling Over Boat Noise is Making Orcas Hungry

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

The Pacific Northwest is a nautical hub for ships and naval training, and the resulting engine noise is drowning out local marine life. Endangered orcas struggling to be heard increase the volume of their calls, and as EarthFix’s Ashley Ahearn reports, this extra effort requires them to eat more, and could stress the whales. (02:55)

Rising Seas and Real Estate Prices in Fort Lauderdale

View the page for this story

The south Florida community of Fort Lauderdale lies mostly just two feet above sea level, and already floods multiple times a year. Yet it’s also currently undergoing a home construction boom, and real estate prices are rising. Host Steve Curwood and reporter Katherine Bagley discuss the social consequences of this paradox. (06:50)

Boston's Not-So-Dirty Water

View the page for this story

Years of pollution and waste dumping earned Boston the infamous designation as America’s filthiest harbor, but heavy clean-up efforts have turned it into an environmental success story. This is due in part to the Deer Island’s state-of-the-art Treatment Plant, which processes all of the metropolitan area’s wastewater. The plant’s Director, David Duest, gave host Steve Curwood a tour of the plant and explained how the harbor has benefitted from its efforts. (05:00)

The Human Cost of Boston's Harbor Clean-Up

View the page for this story

Over budget and behind schedule, engineers raced to complete Boston’s Deer Island Treatment Plant. The final step before the treated wastewater outfall tunnel could become operational was to remove the plugs in the nine-mile pipe to release the cleaned water into the sea. Author Neil Swidey’s book Trapped Under the Sea relates the story of the five men who were sent on this ill-planned and untested task. Swidey joins host Steve Curwood on Deer Island to explain what went wrong, and the lessons learned. (10:40)

Kittiwake: A Life on the Edge

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Iceland is a volcanic country lashed by the North Atlantic. Still, Living on Earth’s explorer in residence, Mark Seth Lender finds Black-legged Kittiwake daring to nest on inhospitable cliffs, and to hunt for fish in the tumultuous waves. (03:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Robert Bullard, Bob Hannah, Marla Holt, Dave Duest, Neil Swidey

Reporters: Emmett Fitzgerald, Ashley Ahearn, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Predictions about global warming and sea level rise seem increasingly alarming – but that’s not deterring a building boom in low-lying South Florida.

BAGLEY: Prices are really doing well in South Florida. They're doing remarkably well, but I think most people would tell homebuyers that it's not a great investment. When you look at what could happen with sea level rise in the next 30 years you know it's kind of daunting to think about buying a house.

CURWOOD: To say nothing of the flood insurance. Also – bright lights as a solution to by-catch problems for shrimpers.

HANNAH: We moved the lights from one net to another, and every time we moved the lights to that side the vast majority of bycatch didn't show up in the net. If you have a lot of bycatch you might have to dump 3 or 4 or 5,000 pounds of shrimp, and at 50 cents a pound that covers the lights.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Flint, A Poster Child for Environmental Racism

People of color are especially vulnerable to environmental injustice and environmental racism. (Photo: courtesy of Petra Daher)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, it’s an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Over the past two and a half years a huge environmental scandal unfolded in Flint Michigan. To save cash in a city plagued by a low tax-base, officials switched the public water source from the Detroit system to the Flint River, but the corrosive river water caused lead to leach from the pipes into the drinking water supply. As many as 12 thousand local children were exposed to high lead levels, health effects are on-going, and replacing the thousands of unsafe pipes will cost millions. Since the majority of Flint’s residents are black and low-income, some observers call this disaster a classic case of blatant environmental racism. Texas Southern University professor Robert Bullard is a noted author and expert on environmental justice.

BULLARD: The Flint water case is the latest poster child for environmental justice. You have the coming together of a perfect storm, you have a low-income community or city, over 40 percent that's below poverty, you have a majority black city. You have a city that's already under stress economically whose democratic process has been removed from the local residents, and you have a decision made by other people who don't live in Flint about their water, and water is life.

CURWOOD: What happened to Flint that residents there lost the ability, the legal ability, to govern themselves and what relation to race do you think that might have?

Robert Bullard is the Dean of the Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs at Texas Southern University in Houston, Texas. He is often described as the father of environmental justice. (Photo: Michigan School of Natural Resources & Environment, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BULLARD: Well, if you look across the state, the cities that are under state control or in receivership, most of them are majority people of color, and I think any time you have the power of duly-elected officials of a municipality stripped, and you have an overseer type government, a disaster manager so to speak, you may get decisions which may be totally different than if people who voted and lived in the city and worked in the city and were concerned about the health of residents. And I think that process of having someone to decide your own fate, that's the heart of the environmental justice movement. You know, for too many cases, from Flint, Detroit, and Cleveland, Houston, LA, you start naming the cities. Oftentimes things are placed in communities of color and low-income companies and residents didn't decide it, they didn't have their political process of voting to determine what goes in and how much comes out, and that's the justice and the equity issue that I think the Flint case is bringing to light.

CURWOOD: Now, apparently it took more than a year and a half or on the scale of a year and a half for attention to be properly paid to the the disaster, the lead poisoning disaster in Flint. Why did it take so long, do you think?

BULLARD: Well again, the Flint case fits the example of what's happening on environmental justice across-the-board. Environmental problems of pollution and environmental degradation or response to disasters and health threats, they often take longer to be acknowledged, it takes longer for the response, it takes longer for the recovery in communities of color and low-income communities, so it didn't surprise me that it took so long for this to come to light because many of these environmental justice problems and challenges that impact low-income and communities of color, they're invisible, they're invisible to the state government, invisible to the federal government, to county officials, not that community residents don't know about them and have not been complaining about them, but they are invisible when it comes to the response.

CURWOOD: This is environmental racism. What do you think motivates environmental racism in this and other cases?

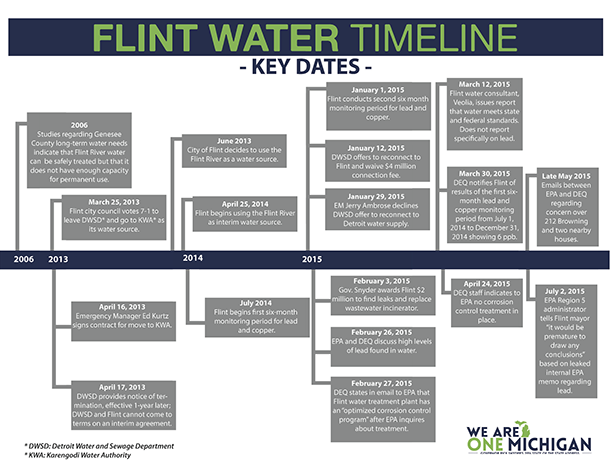

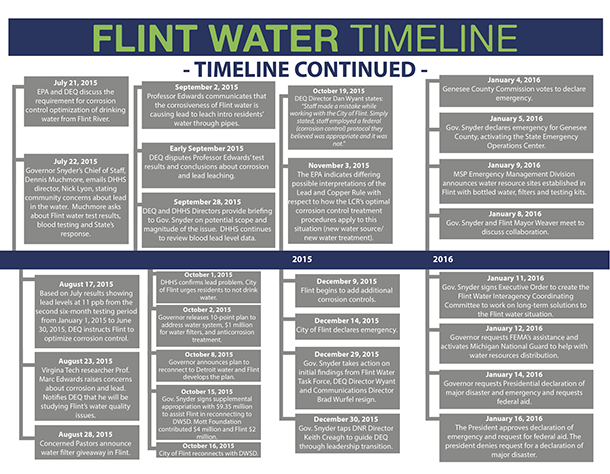

Michigan Governor Rick Snyder’s office released this Flint Water timeline to address questions on who knew what and when. According to the FlintWaterStudy, this timeline is missing some information, but overall is reasonably accurate. (Photo: Office of Michigan Governor Rick Snyder)

BULLARD: Well, I think the fact that environmental racism exists because in the real world, there are some communities that are not considered equal and valued the same as others. We have young people today talking about Black Lives Matter and I think that whole concept grows out of the fact that black communities and communities of color have not mattered for so long when it comes to giving equal protection, providing civil rights and human rights and so this whole notion of environmental racism, it's real. It's so real that even having the facts, having the documentation, having the information has never been enough to provide equal protection for people of color and poor people.

CURWOOD: Why is that?

BULLARD: Well because our society is a long way from being race neutral. Racism permeates every institution in our society. It permeates voting, it permeates housing, education, employment, so we should not be surprised that racism also permeates the way that environmental decisions are made.

CURWOOD: America has a president of recent African descent, and yet the Environmental Protection Agency, the region five that had Flint in its portfolio, dragged its feet, indeed, obstructed the work of a low-level worker who was trying to deal with the situation fitting into this pattern of environmental racism. We have a black president. Why do we still environmental racism in this country?

Timeline, continued. (Photo: Office of Michigan Governor Rick Snyder)

BULLARD: Well, you have to understand that the way the EPA operates is that you have the federal EPA headquartered in Washington, DC, and you have 10 regions, and the regions operate almost as autonomous little EPAs. Regional EPAs work very closely with the state departments of environmental quality and too often that relationship, that cozy relationship, gets in the way of protecting the most vulnerable communities, and so EPA regional offices will oftentimes communicate information with the state agencies and leave the impacted community out of the loop. And so even when you get complaints from Flint residents to the state officials that go up to the EPA, if that's not acted upon, you have to question whether not those individuals should be in those offices with the power and authority to control what happens in communities.

CURWOOD: Compare the national response to the natural gas leak, the massive natural gas in Porter Ranch, California, just outside of Los Angeles. Compare that response to what happened in Flint.

BULLARD: Well, I think the fact that we are talking about two different scenarios, we're talking about two examples, and so when you talk about the nature in which state officials and regional EPA officials have responded to the actions that were taken in Flint, Michigan, in a defensive way, whereas in California, I think, they have been responsive and the actions that have been taken, you don't see the kind of push back, you don't see the level of pushback. I think what this shows is that race and class still matter in terms of how the government response will be pushed forward.

I'll give you an example of ... I saw this up close and personal with how the waste that was cleaned up, the coal ash was cleaned up after the spill in Eastern Tennessee. All levels of government got behind the state of Tennessee to clean up that waste from the coal plant in eastern Tennessee in Roane county which predominantly white. But when the decision was made where to send this waste and where to dispose of it, the people in Tennessee said, “No we don't want this stuff disposed in our state or in our county”, and decision-makers at the state EPA in region four, the EPA in Atlanta decided OK, the best place to put it is to ship it 300 miles south to Perry County, Alabama, to Uniontown, a predominantly black county and predominantly black city that is very poor in Alabama, send it to the Alabama black belt. So if it's so poisoned for Eastern Tennessee, mostly white, very white, why is it not the same consideration given to a poor black area? That's the kind of blatant decision-making at the federal, state, and local level that really don't consider equity and outcomes that on their face may appear to be race neutral, but the outcome is that you're taking waste from white areas and shipping it to black areas and we say that is environmental racism.

Michigan Senators introduce bill to provide support to families in Flint. (Photo: Senate Democrats, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What about the question of climate change? To what extent is that an environmental justice issue?

BULLARD: Climate change is probably the number one environmental justice issue of our time. It is the global environmental justice issue, the communities that have contributed least to global warming and climate change will feel the impacts first, worst and longest, and I think the environmental justice movement, and the climate justice moment speak to this issue not just in terms of parts per million and CO2 and greenhouse gases, but also talk about the equity impact of climate change and talk about the solutions in that real solutions bring to the table those communities that have historically been left out of the environmental decision-making. Our communities, our front-line communities have to be in the room, have to be at the table and have to be part of any solution going forward as it relates to climate action plans.

CURWOOD: Now, you brought some students from historically black colleges and universities to Paris for the Climate Summit. What was that process like?

BULLARD: Well, because the climate change movement historically has not represented all of the diversity of our country, a group of us decided, Dr. Beverly Wright at Dillard University and myself, we decided to come together and form the Historically Black College and University Consortium on Climate Change, and we decided that we will raise the money and bring our young emerging leaders at our HBCUs to Paris for the COP 21. We were able to bring 50 students from 15 universities from Texas all the way across the Gulf Coast and South Atlantic and as far north as Pennsylvania. We bought the students and some faculty mentors who were working on climate and working on all kinds of STEM research and policy. We said that these young people, African-American students, needed to see how policies are being made and what was decided in December in Paris in 2015 will impact these young people going forward. And so they need to be in Paris to show that African-Americans are concerned about climate change and we are in solidarity with other people around the world and showing that the issues that impact people of color and people in the developing world, we have those same issues in our own country as it relates to climate justice.

CURWOOD: Bob, I think it was back in 1990 you wrote the book Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality. What's changed since then and what gives you hope for more change?

Clean water activists (Photo: Unitarian Universalist Service of California, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BULLARD: Well, when I wrote Dumping in Dixie in 1990, Dumping in Dixie was the only book, it was the environmental justice Bible at the time. Today if you Google or if you look on the Internet and search for environmental justice books there's hundreds of books on the topic. There's lots of researchers doing environmental justice scholarship. I see more and more courses and programs at college and universities integrating these concepts of justice into the curriculum across-the-board, and if you look at this whole notion of Dumping in Dixie and environmental justice we confine that book to the southern United States, but today environmental justice covers not just the United States but environmental justice now is a global movement and the issues and the framing has spread across the globe. To me, that's the maturation of our movement.

CURWOOD: Robert Bullard is the Dean of the Barbara Jordan - Mickey Leland School of Public affairs at Texas Southern University. Thanks for much for taking the time today, Bob.

BULLARD: My pleasure.

Related links:

- About Robert Bullard and his work

- Read about Environmental Injustice in Flint

- It’s not just Flint: Poor communities across the country live with ‘extreme’ polluters

- What Zika and the Flint Water Crisis Have in Common

- Bullard: Flint is part of a pattern: 7 toxic assaults on communities of color

- How the EPA Has Failed to Challenge Environmental Racism in Flint—and Beyond

- A Question of Environmental Racism in Flint

- More on Environmental Justice Movement and the history of Environmental Racism

- Gas Leak in Los Angeles Has Residents Looking Warily Toward Flint

[MUSIC: No Strings Attached, “March Of the Picnic Ants,” No Strings Attached, Folk Era Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A bright light for sea life in the Pacific Ocean.

Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Punch Brothers - Passepied (Debussy) From the Album The Phosphorescent Blues, Nonesuch]

Illuminating Fishing Nets Prevent Bycatch

One of the lights attached to a shrimping net. Bob Hannah estimates that these lights will pay for themselves quickly, since eliminating bycatch allows fishermen to keep more of their nets of valuable shrimp. (Photo: Stephen Jones, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife)

CURWOOD: It’s an encore edition of Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. The waters off the coast of Oregon teem with delectable pink shrimp. But shrimpers often also scoop up fish they don’t want, what’s known as “by-catch”, in particular a smelt called the eulachon. And that is costly – for the eulachon, and the fishing boat operators. But Government scientists have discovered a nifty way to cut the eulachon by-catch using LED lights. Bob Hannah of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife told Living on Earth's Emmett FitzGerald all about it.

FITZGERALD: So, first off, tell us a bit about this fish. What is a eulachon?

HANNAH: Yeah, it's a neat fish. It's also called the candlefish. It's an anadromous smelt, lives in the ocean, but it runs up rivers like the Columbia to spawn, and it's been harvested by lots of people for many years, including Native American tribes for food and other uses.

FITZGERALD: And so when did you first notice that these fish were getting trapped in shrimping nets?

HANNAH: These fish have been a bycatch in the shrimp fishery since day one when the fishery began in the ’50s. In fact, fishermen invented the smelt belts to sort them out in the ’80s because they were so abundant at that time.

The Eulachon is a small smelt species of fish. (Photo: Sam Beebe, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

FITZGERALD: And what's a smelt belt?

HANNAH: Smelt belt. It's a rotating sandpaper belt that's part of their deck gear, shrimp slide down them but the smelt stick and they're pulled up and go out a trash chute. They've been abundant enough to require mechanized sorting for a quite a long time.

FITZGERALD: And so, now, fisherman in Oregon have been using grates also in their nets to sort of exclude some of the fish like the eulachon, that they don't want to prevent that bycatch. How do those work?

HANNAH: Well, they work very, very well. They're an inclined panel of vertical bars that sort the large fish out. They go out the top, out of the net and let the shrimp pass through. They work very, very well on large fish. They also work, to some degree, on eulachon and other small fish, but it still left a fair amount of bycatch in the catch.

FITZGERALD: So how did you come up with the idea to use lights to light up these fishing nets?

HANNAH: Well, it was a little bit by accident, a little bit by design. We had done some camerawork, underwater camera work, to look at the behavior of the eulachon as they were being excluded from the trawls. We wanted to make sure they were in really, really good condition and that they weren't just being completely stressed out before they were excluded from the trawls. And we wondered how the lights of our camera system were affecting what we were seeing and so we decided to test what the effect of light was on the exclusion efficiency. So we came up with this light experiment. It was funny. Our hypothesis going in was that if we put these lights around these grates, that more eulachon would go out of the net, and the exact opposite happened. More of them went through the grate and ended up getting caught, in fact, it about doubled the bycatch. Fortunately for us, we also had decided to try them up on the footrope at the front of the trawl, right where the netting attaches. And the nets in this fishery run about 18 inches to 24 inches above the seafloor, so there's a big space underneath for fish to go through. They just won't use it a lot of times.

Shrimp catch (and eulachon bycatch) without lights (Photo: Stephen Jones, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife)

FITZGERALD: And so what did you find? So when you put the light to the front of the net what was the impact on bycatch?

HANNAH: Well, it was amazing. These vessels are double rigged. They're on two nets at one time, so it's really nice...you put lights on one net, no lights on the other. You dump the catches into a divided hopper, and you can see immediately the difference. When we dumped our first tow with the lights up on the footrope it was amazing. There was quite a bit of fish in one side with the shrimp and the other side was basically nothing but shrimp. We all looked at each other, we knew something very significant had just happened unless it was just a fluke. So we did a few more tows and we moved the lights from one side, one net to the other and every time we moved the lights to that side, all of a sudden the vast majority of bycatch didn't show up in the net.

So that evening - we finished seven tows that day, that evening were sitting around the dinner table and the skipper was skimming the boat toward shore. I didn't really know why but I was so focused on my dinner. We get inside cell phone range and he picks up the cell phone, calls his wife and orders $2,000 worth of these lights. When he got off the phone I asked him “Are those to pay for themselves?” and he says “Probably in a day”. If you have a lot of bycatch in your net sometimes you have to dump the whole tow and have to dump 3, 4, or 5,000 pounds of shrimp and 50 cents a pound that covers the lights.

FITZGERALD: So, Bob, tell me what you think is going on? What about having the lights at the front of the nets is enabling the eulachon to avoid becoming bycatch?

Shrimp catch with the lights. (Photo: Stephen Jones, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife)

HANNAH: Well, OK, here's our working hypothesis. The shrimp fishery works at pretty deep depths, 60 fathoms up to 140 fathoms. So there's not much light on the sea floor. It's virtually dark. So what we think is happening is: the fish react in what's called an opti-motor response. They just avoid an approaching object even if they can just barely see it. We think that in both cases at the grate and at the front of the trawl adding a light allows the fish to navigate through a confined space in the back of the trawl that they go through the grate and I think they can see that there's something back there that they're comfortable going to. I think at the front they see that there's a space between the net and the seafloor that they can get through and get back to sea floor so I think it allows them to utilize escape routes that are there.

FITZGERALD: So you're basically just using a little bit of technology and giving them a hand to save themselves.

HANNAH: Yeah, but it's very interesting in it's kind of a cool thing because it's been known for a long time that in the day and the night fish react differently to approaching trawls and inside the trawl. And now what we've shown is that by adding a light you can alter the effect in a low light situation in terms of how they respond to the components of the trawl. So it may have applications in other fisheries to get the fish you want out of the trawl, out of the trawl.

FITZGERALD: So tell me a little bit about the reaction you've had from fishermen in the area. Are people excited about this development?

Bob Hannah (center) poses with a bycatch reduction grate (Photo: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife)

HANNAH: Oh, they are so excited. We did send a newsletter out to the fleet to tell them, hey, this is a good thing to do. And within two months, the entire fleet virtually was using these lights. Anybody who didn't have them, had them on order, and when we surveyed the fleet back in September, October, of last year we got these written surveys and we got a lot of great comments, "Thanks for doing this”. “This is great. How did you think of this?” “We really appreciate you guys," and we're still getting comments like that from people who are coming back into the fishery. "We're so glad you guys figured this out." And I don't think that's coming from an overwhelming sense of conservation concern for the eulachon, I think it's coming from some of the operational difficulties that the technology solved for people who were having high bycatches.

FITZGERALD: Bob, at the end of the day what do you hope comes out of this research?

HANNAH: What I hope comes out of this, I hope that the people in a lot of trawl fisheries around the world come up with innovative ways to reduce bycatch in other fisheries with other problems and understand better methods for motivating fish to use bycatch escape routes in trawls so that trawl fishing in general can be cleaner and more sustainable.

CURWOOD: That’s Bob Hannah of the Oregon Dept of Fish and Wildlife in conversation with Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald.

Related link:

Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife’s report on the use of LEDs to reduce Eulachon bycatch

Calling Over Boat Noise is Making Orcas Hungry

A dolphin trainer records orca vocalizations at different volumes to help scientists understand energy expenditure in the presence of underwater ship noise. According to the lab, all procedures were approved under U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service permit No.13602. (Photo: courtesy of Terrie Williams' Mammalian Physiology lab at University of California, Santa Cruz)

CURWOOD: Becoming by-catch isn’t the only problem for sea creatures off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. Undersea noise levels are increasing in the region as thousands of freighters, ferries and other vessels motor up and down the coast. And some new research details how that noise could make life harder for endangered marine mammals. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn has the story.

AHEARN: Picture yourself at a noisy bar. You realize that you have been shouting at the top of your lungs all night just to be heard. Well, orcas in Puget Sound are in kind of the same situation.

[LOUD VESSEL NOISE]

AHEARN: This is a recording from a hydrophone that was suctioned on to a wild killer whale in the San Juan Islands, near a passing vessel. Loud boat noise like this forces endangered killer whales to raise the volume of their calls. Marla Holt is a biologist at the NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle.

HOLT: But the question is, OK, so they do it, but so what? What are the biological consequences of them doing this?

AHEARN: To answer that question, Holt and her NOAA colleague, Dawn Noren, studied captive bottlenose dolphins. In the experiment the dolphin swims into this funny little floating plastic helmet-looking thing, that’s positioned over its head. Then the trainer asks it to make its normal whistling call for two minutes for a fishy reward.

[DOLPHIN WHISTLES]

Dawn Noren measured how much oxygen the dolphin used during those two minutes.

Though the killer whale (orca) species is not endangered globally, the population residing off of the Pacific Northwest’s coast is. (Photo: Robert Pittman/NOAA; Wikimedia Commons)

NOREN: And then by knowing oxygen consumption you can determine metabolic rate or how much it costs you to work, or work harder.

AHEARN: Then the trainer asked the dolphin to pump up the volume.

[LOUD WHISTLES HERE]

Making that louder call takes more energy. Holt and Noren found that when the dolphin was whistling harder and louder its metabolic rate rose by up to 80 percent above normal resting levels. And just like people, when their metabolic rate goes up, they burn more calories, so they have to eat more.

NOREN: If you have multiple incidences where you’re increasing your vocals to compensate for a noisy environment, you could have some increased need to find more fish.

AHEARN: The scientists say that when wild orcas are around loud ships, the volume of their calls increase by the same amount, or more, than the dolphins in the lab. That could mean wild orcas need to eat more salmon to make up for the calories they’re burning to vocalize more loudly around big ships.

HOLT: The concern is basically for animals that are maybe just getting by or not really getting by, we could say, this is how much more fish it would cost an animal if it was disturbed that much more.

AHEARN: Holt says that as the region considers proposals to expand coal and oil shipments, as well as Naval training activities, this research could be used to calculate specific impacts on marine mammals like endangered killer whales. There are just 81 of them left.

I’m Ashley Ahearn in Seattle.

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for Earthfix, and to be clear, while there are as many 50,000 Orcas still on the planet, the population often found near Seattle is considered endangered because of its small numbers.

Related links:

- More about orcas and noisy oceans

- Study: Speaking up: Killer whales (Orcinus orca) increase their call amplitude in response to vessel noise

[MUSIC: Abdullah Ibrahim, “Mannenberg,” Amandla! A Revolution In Four-Part Harmony, ATO/BMG]

Rising Seas and Real Estate Prices in Fort Lauderdale

Fort Lauderdale is undergoing a construction boom in anticipation of 50,000 more residents -- about a third of its current population -- in the next fifteen years. (Photo: Katherine Bagley)

CURWOOD: Concerns about fishing and noisy oceans aren’t the only kinds of sea stories we often report on – increasingly there are reasons to worry about the waters rising. This is one of the most obvious and ominous effects of global warming, and that makes living in low-lying coastal areas increasingly risky. Yet some of the very places that will be most affected by rising seas are undergoing real estate booms, such as South Florida. In Fort Lauderdale, “the Venice of America” for example, developers are cashing in on new housing near the sea, though its 165 miles of canals, make it particularly vulnerable to rising seas, as much of the city is close to sea level already. Writer Katherine Bagley reported on Fort Lauderdale’s real estate bonanza and impending sea level rise for InsideClimate News and she joins us now. Kat, welcome to Living on Earth!

BAGLEY: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about Fort Lauderdale's growth? How much is Fort Lauderdale projected to grow over these next several decades, at least according to the Chamber of Commerce.

A seawall undergoes repairs along one of Fort Lauderdale’s numerous canals. (Photo: Katherine Bagley)

BAGLEY: It's expected to grow by a third. There's about 50,000 people that are expected to move to Fort Lauderdale in the next 15 years and currently the city doesn't have the housing to be able to accommodate those people so there's this massive building boom happening within city limits. There's skyscrapers going up and new condos, new apartment buildings. The city is really transforming itself to accommodate this huge influx of population.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, there are many cities along the coastline. Why is Fort Lauderdale so vulnerable to sea level rise?

BAGLEY: Fort Lauderdale, as you had mentioned, is the Venice of America, so it has 165 miles of canals that wind its way really through the innards of most parts of the city, and like most of South Florida it sits on top of a limestone bedrock which is a very porous bedrock, and it means that when sea levels rise they not only creep over sea walls, they also actually creep through the underlying bedrock of the city and so you'll have water that will creep under homes and into streets. It really affects almost every part of the city. The water is really the heart and soul of Fort Lauderdale and it could be its downfall in the end, unfortunately.

CURWOOD: So to what extent is flooding already happening in Fort Lauderdale?

The streets of Fort Lauderdale flood with seawater a couple of times a year, during “king tide” events, when the sun, moon, and the earth align. (Photo: Katherine Bagley)

BAGLEY: Right now the worst flooding that you see is around these king tide events which is when the Earth, the sun, and the moon all align. They happen a few times a year and that's when high tide is 18 inches above normal. Streets flood, yards flood, critical infrastructure is at risk. Because sea level has risen 8 inches in the last 100 years that king tide is 18 inches on top of sea level rise, so it's getting worse and worse and worse every year.

CURWOOD: So how has the real estate market reacting to this increased risk, this increased reality of flooding?

BAGLEY: The real estate market itself, I mean, like I say, it's booming, and as of right now construction codes in the city require that buildings are built one foot above the floodplain but no more than that. I had city officials telling me; “It's true that some of the buildings that are going up now might be dealing with severe flooding in 30 years”, and that's the lifespan of a mortgage.

CURWOOD: What kind of disclosure is there to people who are buying these properties about the flood risk?

What sea level rise looks like in Fort Lauderdale. (Photo: courtesy of InsideClimate News)

BAGLEY: There's not really any disclosure. The real estate community doesn't really want to talk about this and so they're not required to talk about flood risk. When you buy a house and there's lead paint you have to get a disclosure form, there's nothing like that for sea level rise, and climate change and flood risk.

CURWOOD: Now, how do the locals you talk to feel about the fact that sea levels are projected to rise so much and flooding is just going to become more and more common in Fort Lauderdale?

BAGLEY: The last several years those king tides have been a real wake up call and so most people in South Florida know about climate change, they're aware that it's happening, and city officials are racing to take action. Fort Lauderdale officials are putting in a bunch of new flood mitigation measures, things like one-way valves to stop sea levels from creeping onto roads. They are taking steps to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, but it's a really tough battle.

Canal water spilled over a seawall into a Fort Lauderdale backyard during a recent king tide event. (Photo: Katherine Bagley)

CURWOOD: What about the low income and minority communities there. Often around the world, they're on the front lines of climate disruption. What's the situation there in Fort Lauderdale?

BAGLEY: So the low income communities in Fort Lauderdale are actually at the highest point of elevation in the city and so right now they are the safest. The question becomes when the waterfront properties start flooding, the higher income properties, where are those people going to want to move? And they're going want to move into the higher elevation areas. One of the experts that I talk to termed it "climate gentrification" and when you have sea level rise and the oceans rising to the east and you have the Everglades to the west, there's really no place for these people to go.

CURWOOD: So how does the City of Fort Lauderdale's response to this compare to the state’s response on the dangers of climate disruption?

BAGLEY: Fort Lauderdale and South Florida are very much alone in their battle against climate change. Tallahassee, the state capital, Gov. Rick Scott, most of the state legislators are very much against climate action. Gov. Scott has reversed most of the climate programs that previous governors have put in place. They've banned the term “climate change” in government work, and so really communities in Florida that want to deal with this issue either have to band together with their surrounding areas which is what South Florida has done or they really have to fight it alone. They don't have much support from the state.

Luxury waterfront properties in Fort Lauderdale tend to be owned by the wealthiest residents of the city; as they relocate due to sea level rise, lower-income populations may be priced out of their homes on higher ground. (Photo: Katherine Bagley)

CURWOOD: So how many individuals who own places there are starting to smell the coffee and quietly putting their places on the market so they can get some money for them now while there still is money to be had?

BAGLEY: I think you're seeing a few people start to do that, but of course you haven't seen this mass exodus, and even if they were, there would be plenty of people willing to come in and buy their property and take their place.

CURWOOD: So, property values are staying flat at least, maybe even rising?

Katherine Bagley reported the story on Fort Lauderdale’s real estate boom for InsideClimate News. She is now an editor with the online magazine Yale Environment 360. (Photo: courtesy of Katherine Bagley)

BAGLEY: They're definitely rising. Prices are really doing well in South Florida especially considering they were just in a recession a couple years ago. They're doing remarkably well, but I think most people would tell homebuyers that it's not a great investment. When you look at what could happen with sea level rise in the next 30 years you know it's kind of daunting to think about buying a house and it's not just the value of the house, it's the flood insurance. At some point our flood insurance premiums are going to increase and some economists have said that the premiums could rise so much that nobody would be willing to buy a house.

CURWOOD: Katherine Bagley reported on Fort Lauderdale for Inside Climate News and is now an editor at the online magazine Yale E360. Thanks so much, Kat.

BAGLEY: Thank you so much for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Katherine Bagley’s article, “Rising Seas Pull Fort Lauderdale, Florida’s Building Boomtown, Toward a Bust”

- Sea level rise simulator

- About Katherine Bagley

- Living on Earth’s previous discussion on the climate risk for real estate values in south Florida

[MUSIC Ray Charles, “Laughin’ and Clownin’, on Singular Genius: The Complete ABC Singles Sampler, Sam Cooke (ABKCO Music), Concord Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up -- Keeping sewage out of seawater – and what it cost in Boston harbor. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Medeski, Martin, Wood, Scofield “North London” juice 2014 Indirecto]

Boston's Not-So-Dirty Water

Twelve 130-foot-tall, egg-shaped digesters process the solid waste collected from Boston’s sewers. The system turns sludge into biogas, which is used to heat the plant; steam, which generates electricity; and processed solid waste that’s then turned into fertilizer pellets. (Photo: Frank Hebbert, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's an encore edition of Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: I love that dirty water, Oh Boston, you’re my home.” The Standells, 1966]

CURWOOD: Love the place or not – back in the day, the “dirty water” was no exaggeration – sewage went into Boston harbor only partially treated, and the water was truly foul.

DUEST: Boston harbor was one of the dirtiest harbors in the nation, and we were actually rated at “D” or below for water quality. As a matter of fact, you couldn’t fish or swim within Boston harbor for most of the days out of the year.

CURWOOD (with ambi under): That’s Dave Duest, the man in charge of the answer to Boston’s filthy harbor. It was so disgusting that in the early 1980s, a series of lawsuits were filed, requiring proper treatment of Boston’s sewage, though it doesn’t catch the microbeads we know about today. There were numerous delays, and the new infrastructure cost nearly 4 billion dollars. But the result was a state-of-the-art treatment plant on Deer Island.

DUEST: We are actually in the middle of Boston Harbor which is the outermost stretches of the metropolitan Boston area and the Deer Island treatment plant serves 2.3 million people, which is about 34 percent of the total state population for sewage treatment services.

CURWOOD: If you ever come to Boston, you see Deer Island from the aircraft. You have got these iconic big egg-shaped containers, looks like you're trying to hatch something out here. What, in fact, do they do?

With a peak capacity of 1.3 billion gallons of wastewater treated per day, Deer Island Treatment Plant is the second largest wastewater treatment plant in the nation. (Photo: Anthony92931, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

DUEST: They're actually a critical part of our wastewater treatment operations. We actually put all of the solid material that is conveyed within the wastewater into those vessels, each one of those being 3 million gallons apiece; we have a dozen of those.

CURWOOD: All that flushing creates a lot of water. What happens to the water?

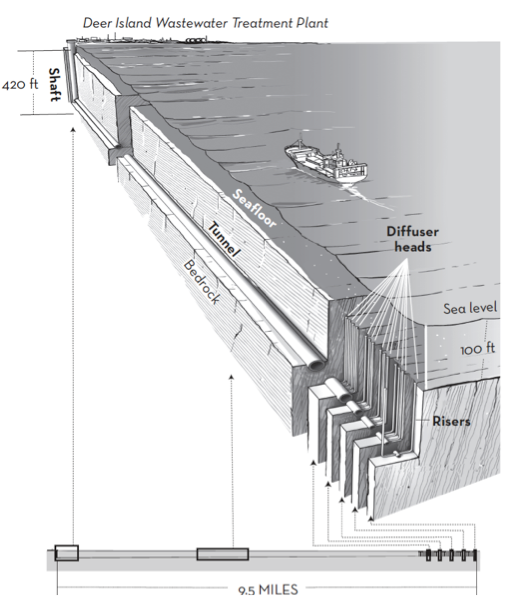

DUEST: We get up on average 360 million gallons of wastewater a day into this plant with peaks up to 1.3 billion gallons per day, all of that material gets pumped to Deer Island and then lifted up into the treatment process. After we clean it up we remove 94 percent of the total solids out of that wastewater and the remaining clean water then gets disinfected, dechlorinated and then sent out into Massachusetts Bay for final disposal.

CURWOOD: And where does that water end up?

DUEST: Eventually all the treated effluent is disposed of in Deer Island's outfall, it goes into a deep broad tunnel that's 450 feet below the surface, travels nine-and-at-half miles eastward out into Massachusetts Bay and that gets distributed over that last mile and a quarter through 53 risers that are just like sprinkler heads on the bottom of the ocean floor, and that actually disburses over a wide area so you don't get that single one open end of a pipe that's going to impact that one area.

CURWOOD: And so, now, today, in Boston Harbor, what's different about the ecology here?

DUEST: The ecology is actually greatly improved. We've gone to the full secondary level of treatment so the quality of the effluent that leaves the facility is much, much cleaner than it was ever in the past. We haven't had any permit violations for over eight years now and we're actually seeing a recovery of the harbor so that things like Eel grass are actually naturally reestablishing themselves back into Boston Harbor. Eel grass is a very sensitive natural species of sea grass that only grows when the water is very, very clean.

Foam floating on the treated water is the result of chlorine that’s added to kill bacteria. The foam is skimmed off before the water travels down a 10-mile-long outfall pipe to the outer reaches of the harbor. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: Well, I'd really like to take a look at this outfall. I'm not sure I want to go all the way down the tunnel, and I guess it's full, so I can't right?

DUEST: You cannot. If you go in there it's the point of no return. You'll come out nine-and-a-half miles later about 12 hours later actually.

CURWOOD: But I really want to take a look at where this is, so let's head over there.

DUEST: That sounds good.

[SOUNDS OF RUSHING WATER]

DUEST: Alright. We are now at the end of the disinfection basin just prior to the start of the outfall tunnel.

CURWOOD: It looks like sort of a ladder of a bunch of waterfalls with, well, a fair amount of detergent. Don't tell me that some somebody's washing machine.

DUEST: What you're actually seeing there is a little residual chlorine that's actually causing a little bit of foaming. All of that foam however is collected in our systems and never actually makes it out into Massachusetts Bay, but really what you're seeing is the water spilling over and dropping about 10 feet over the edge and then filling up to a certain level providing the head that it needs to send it to the outfall.

CURWOOD: Now I'm looking over the side here, and I'm seeing oh, there's a really deep long channel that goes way down. What am I looking at here?

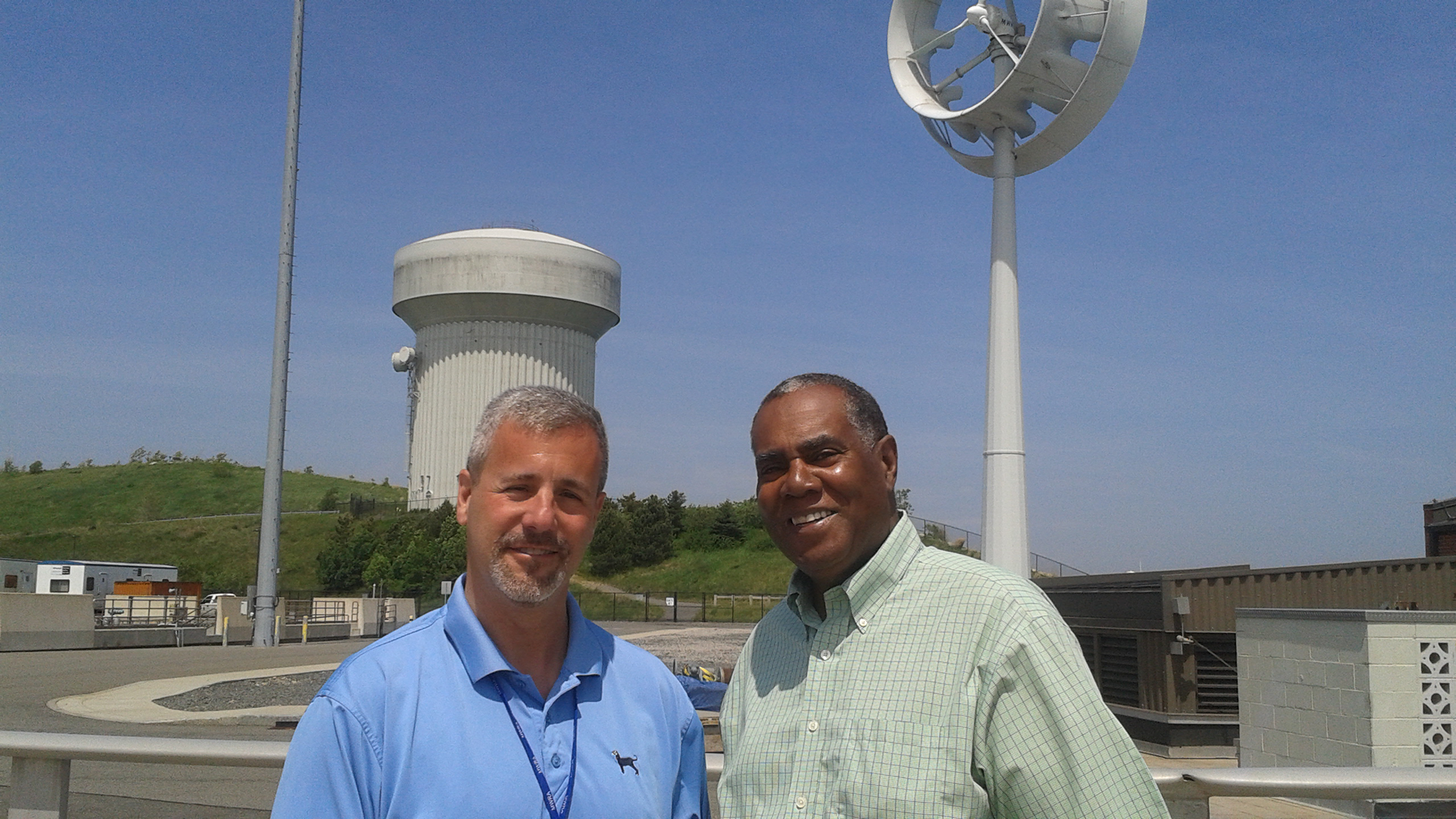

Host Steve Curwood, on right, with David Duest, the Director of the Deer Island Treatment Plant in Boston, MA. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

DUEST: There's a bypass channel that you're seeing down below which is actually one of the recycle streams. We use treating effluent as cooling water for some of our facilities.

CURWOOD: So how do you guys feel about this operation? How good is it?

DUEST: Deer Island's actually been in operation for 20 years and it's doing very, very well. We're seeing the recovery of Boston Harbor, we're seeing no impacts to Massachusetts Bay, so I’d say that the Deer Island treatment plant is meeting its objectives.

CURWOOD: Dave Duest is Director of the Deer Island treatment here in Boston Harbor. Dave, thanks for taking the time to walk us around your plant.

DUEST: You're welcome.

[MORE WATER SOUNDS]

Related links:

- How the Deer Island Treatment Plant works

- About the Boston Harbor cleanup

- “Boston Harbor: The Anatomy of a Court-Run Cleanup” (Academic paper)

- Video: “How We Cleaned Up the ‘Dirtiest Harbor in America’ – Travel Channel’s Off Limits

The Human Cost of Boston's Harbor Clean-Up

By the time it was completed, the outfall tunnel contained oxygen-starved, toxic air that would be deadly to anyone who breathed it. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

CURWOOD: Well, Dave Duest mentioned the deep rock tunnel that channels the cleaned water nearly ten miles under Boston Harbor – it was an engineering feat that had a human cost as well. Boston Globe writer Neil Swidey chronicles this story in his recent book, Trapped Under the Sea: One Engineering Marvel, Five Men, and a Disaster Ten Miles Into the Darkness. It tells the story of a group of divers whose lives depended on untested technology and questionable decisions, with deadly consequences and overlooking the now sparkling harbor from Deer Island he told us about it.

SWIDEY: I was fascinated by this story that I didn't know about, and that most people even here in Boston didn't know about, which was the final piece of this massive cleanup of Boston Harbor and the people who put their lives on the line to create this beautiful harbor that we see today. After building this massive, sophisticated treatment plant, there was the construction of the world's longest tunnel of its kind. It sends the treated wastewater out into the deep Atlantic waters of Massachusetts Bay. That tunnel and the final piece of that tunnel was the subject of the book.

The outfall tunnel carries effluent, or treated wastewater, from Deer Island Treatment Plant nearly 10 miles out into Massachusetts Bay. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

CURWOOD: You write about the people who worked on that last bit and the accident that happened. First tell me, what was the set-up. Why, in your view, looking back, was this an accident waiting to happen?

SWIDEY: It's fascinating. This project here that did this miraculous conversion and transformation of this harbor, taking the nation's dirtiest harbor and turning it into its cleanest urban harbor, it was a remarkable transformation. The people who worked on that were some of the best and the brightest minds in the world and they made a host of good decisions over a decade, but at the end they made some serious and tragic bad decisions that forced a group of blue-collar workers to risk their lives to rescue this project.

CURWOOD: What exactly did these blue-collar workers have to rescue?

SWIDEY: So at the very end of the tunnel, it chokes down and it goes from 24 feet wide to just five feet in diameter. The whole point is this massive tunnel moves up to a billion gallons of treated wastewater through every day and yet it doesn't use a single pump or electrical source - it's all gravity that moves that effluent through the tunnel every day.

While the project was being built, there was a series of safety plugs at the end to protect the sandhogs, the tunnel workers, for the decade that it took to build the tunnel. Nobody figured out how those plugs were going to get out. At the end, when this project was over-budget, past deadline and under a federal court order to meet these deadlines, there was an enormous amount of pressure, an enormous amount of infighting among the various contractors and subcontractors and managers. Nobody could get along. Trust had gone down on the project. The powers-that-be looked for a rescue artist to come in, and that was a team of commercial divers who were going to go into the tunnel, which by the way at this point had been removed of all of its life-support, the oxygen, the lighting, the transportation. All those systems had been removed but the tunnel wouldn't work unless these 55 safety plugs, these stoppers at the end of the tunnel, were removed.

Five divers were sent into the tunnel to release 55 safety plugs that would prevent the tunnel from flooding in the event that a diffuser head was damaged. Without the plugs’ removal, the outfall pipe would not be operational. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

CURWOOD: So somebody had to go down there and get those corks out. Some divers were hired. Doesn't sound so bad at this point but I guess it went bad. What happened?

SWIDEY: Well, basically, divers were asked to do something that never been done before, because this was so far out, so remote and so confined, this space at the end of the tunnel, just five feet in diameter. In fact, those plugs were nestled in connector pipes that were 30 inches wide, so just slightly wider than our shoulders.

CURWOOD: Well, wait a second...I'm going to say...how does somebody get in there?

SWIDEY: They had to crawl in there and the most fundamental source of risk on this was that it was too far out to bring conventional air supply that divers would be used to - high-pressure bottled air. You'd use up all your supply just getting out to this remote spot and you wouldn't have the time to crawl into these slimy connector pipes in pitch black and remove these.

CURWOOD: So just to be clear, there's air in this tunnel but apparently it's not air anyone can breathe.

SWIDEY: Yes, the tunnel hadn't been filled yet, so they didn't send in divers to swim into the tunnel. They sent in divers because they guys know how to do dangerous jobs in environments where they have to bring in their own air. At this point, deep into the tunnel a decade after it was being built, one or two breaths of the ambient air would be fatal, it was oxygen-starved, toxic air and so the divers had to bring in their own breathing gear, something that they're used to, but the air they're used to has been tested, it's bottled air, it's a supply that you can trust. This was too far out, so this hotshot engineer that they hired came up with this plan to mix liquid oxygen and liquid nitrogen right there in the tunnel and turn that into breathable air.

The five men traveled as far as they could in the narrowing tunnel in two Humvees they’d brought – one towing the other backwards. Since there would be no room to turn a Humvee around, they planned to abandon one vehicle and drive the other back when their dangerous mission was complete. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

CURWOOD: This hotshot engineer gets the job as the lowest bidder?

SWIDEY: He gets the job really as the only bidder. The contractor cast about and they found a couple of people who came and toured this and said, "Sorry, no thanks. I don't care how much you're paying, it's not worth it. I can't do this safely." But this one engineer came in and said, "I can get you out of this jam and I've got this innovative cutting-edge plan to do this." But he didn't go in. He sent in this team of five divers and not all of them made it out alive, tragically.

CURWOOD: So what happens?

SWIDEY: So five divers go into the tunnel. They take these converted Humvees - two of them, one towing one in the opposite direction - because once you get in, there's not enough room even to open the doors all the way so you just take the other one heading back the other direction when you want to get back.

CURWOOD: This sounds bad already.

SWIDEY: Yeah, but then the Humvee could go only so far. Two of the divers would stay in the Humvee monitoring the breathing system for all five while three proceeded on foot using umbilicals, hoses that connected them into the main system, and they went out into the dark to try and get these plugs out.

CURWOOD: So what exactly happened?

Since the air in the tunnel was so toxic, the divers needed to bring their own air. But their air supply system, which had never before been used on a project, malfunctioned – proving deadly for two divers. (Photo: MWRA file photo)

SWIDEY: This experimental breathing system that hadn't been fully thought through failed. At the very end, when the three-man excursion team who were on foot were crawling into these narrow pipes and they pulled a couple of plugs out, and the foreman of that crew looked up at that one point and all their umbilicals had become tangled because it was so confined and there was so much crawling around back there and he said, "Let's stop and let's iron these out, let's get our things straightened out." And as that was happening, he looked in horror to see one diver collapse onto the tunnel floor and another one go right there.

So he lunges for a safety valve to switch the divers to a back up system, and then they try to connect with the divers who were back in the Humvee to see what the oxygen percentage was. And as you know the oxygen we breathe is not 100 percent, it's 21 percent oxygen, but if it drops very far below that 21 percent bad things happen. And he knew that if that percentage was below 16 percent they were in deep trouble, and so he said, "What's the oxygen percentage?" and they said, "We'll have to check because the system was so jerry-rigged because someone had to leave the Humvee to check the pressure valves and come back and then he reports back that it's 8.9 percent and then the line goes dead.

CURWOOD: So we know the story. So that means that some of them got out alive but not all I gather. How did the ones survive?

SWIDEY: Three drivers made it out alive, two tragically did not, but one of the most jarring revelations for me was how close it came to all five divers perishing - it was 30 seconds - 30 seconds had that foreman not reached for that backup valve when he sensed trouble. All five of them would have perished.

CURWOOD: Well, surely, in these modern times we would've had the capability to not have that. How the heck did this happen in the face of how smart we're supposed to be?

The Living on Earth crew on-scene as host Steve Curwood speaks with author Neil Swidey. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

SWIDEY: Yes, well I think it happened because of the organizational failure at the end of this project. When you have a situation where the contractor and the manager and the owner aren't getting along, you have to fix that, because if you don't fix it then, this is what can happen. You have a lot of people who are responsible for this amazing project here who don't like talking about it because of how this ended and that's a tragedy. They should be taking bows at conferences about what the success story was here, of how remarkable this transformation was here and that means managing it all the way through.

After the tragedy of the accident, the leader of the MWRA, Doug McDonald at the time said, "Tensions and finger-pointing got us into this mess and worries about costs and who's going to pay what got us into this mess, so we're going to take money off the table and we are going to use our bright collective minds here to figure out how to solve this in a creative innovative way. And then we'll worry about money after that." And that gave people the permission to think creatively and come up with this innovative solution that ventilated this tunnel, got air back into the tunnel in this brilliant engineering solution that no one had thought of before, and those plugs came out – pop, pop, pop - in two days. The tunnel was operational and then this transformation was allowed to begin. So the challenge I think for people looking at this is how do we get that post-tragedy realization of "We've got to work together here" without suffering the tragedy?

CURWOOD: And there's a memorial for these men.

Neil Swidey is an award-winning staff writer for The Boston Globe Magazine and teaches at Tufts University. His other books include The Assist and Last Lion: The Fall and Rise of Ted Kennedy. (Photo: courtesy of neilswidey.com)

SWIDEY: So the five members of the team – DJ, Hoss, Riggs, Billy and Tim - all put together and asked to do this impossible job. Hoss, Riggs and DJ who were the farthest out, made it out alive. Tim and Billy did not. But those three who survived that risked their lives more by bringing the bodies of their fallen team-members back, they added much more time to their already narrow escape path in order to bring those bodies home with dignity. And today, on this island, there are plaques to Billy and Tim, and there are memorial benches on this path that rings the island of bikers and walkers and roller-bladers and you can sit and look out directly above that ten-mile path of that tunnel and you see that clean water, and you can think about those two otherwise anonymous workers, Tim Nordeen and Billy Juse and say "Thank you" to them to the work that they did and that we all benefit from.

CURWOOD: Neil Swidey's book is called, "Trapped Under the Sea". Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SWIDEY: Thank you, Steve. My pleasure.

Related links:

- Trapped Under the Sea

- Selection from Trapped Under the Sea

- About the outfall tunnel

- 1997 MWRA report on the outfall

[MUSIC: Elvis Costello, Shipbuilding, Punch the Clock, CBS, 1983]

Kittiwake: A Life on the Edge

Black-legged Kittiwake perch on basalt ledges above Grundarfjörður, Iceland’s turbulent sea on the Snaefellsnes Peninsula. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: The sea in Boston harbor was calm and peaceful that day – but just as often the ocean can show its tough and merciless side. That’s what our explorer in residence Mark Seth Lender found, when he visited Iceland – and found Black-Legged Kittiwake daring to nest right on the cliffs, despite the wild waves lashing the shore below.

Kittiwake and Fulmar in the distance, Reyniusfjara, Iceland (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Kittiwake Nesting on an Ancient Basalt Core

Snaefellsnes Peninsula, Iceland

© 2015 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: Lava works its way down, steams and smokes and spits as it meets cold water. Then, wears away, retreating inland till only the core remains: Black basalt crystalized in octagons like giant’s teeth, a long wall grinning and gnashing towards an ancient sea…. While the sea grins back. Waves are its teeth its tongue spray and foam. It puts the bite like Viking iron upon the stone chafing and gnawing. Pebbles that were bed rock leap as the breakers crash, roll like rain fall into the trailing spume; husssssh as the sea flows out, wusssssh, as the sea flows in. Small and small the ocean grinds volcanoes into sand. Ashes to ash, smoke to dust. Until once more the molten rock (and the landward side puts its shoulder to the task).

Black-legged Kittiwake on Evidghedsfjorden Glacier, Greenland. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Above this maelstrom, white traces the midnight rock like paint. Kittiwake, clinging to their narrow ledges where the basalt cleaved away. Their dark eyes, their black feet joined to this black place; until they spread their wings. Swooping like reckless kites down toward the gaping hunger of the sea. Then up, and through the surge on a rollercoaster of thin air, a pleasure in the peril, what else could it be? They cannot fish when the water is angry like this and here it is angry all the time. They take a risk, the ocean reaching beyond its reach will knock them down. The fishes, coming from a line that is older (older than any of this), wisely lie beyond the turbulence. Kittiwake though they know where fish hide and where to find, instead put self (and therefore progeny) in harm’s way....

Kittiwake soar on the wind, swooping up and down in parallel with the sea’s surge, but just out of reach. Meanwhile, tasty fish lie just beneath the water’s surface. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

Maybe risk is what it’s all about. And the birds are only reminding themselves: Life does not belong here. Iceland, hovering over the howling place where the Earth to its innards is split in two. The fire, patient, waiting for the break through, flexing its molten fingers until it reaches out, as the sea reaches for sea birds.

How beautiful, the way life hangs on. How brave it is to live.

CURWOOD: Writer Mark Seth Lender – and there are photos at out website, loe dot org.

Related links:

- More about Black-legged Kittiwake

- Mark's guide in Iceland was Haukur Snorrason

- You can find more information about visiting Iceland at Iceland Naturally

- Nature Photo Tours provided additional support for mark's fieldwork

[MUSIC: Donald Fagen, “Walk Between The Raindrops” on The Nightfly s1982, Warner Brothers]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Anica Green, Jay Feinstein, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Charlotte Rutty, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at l-o-e dot org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth.

I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes fom the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth