August 19, 2016

Air Date: August 19, 2016

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Change Threatens Trillions Worth of Financial Assets

View the page for this story

New research from the London School of Economics estimates that a broad range of global stocks and other financial assets are overvalued because investment managers don’t take the risks of climate change into account. LSE researcher Alex Bowen tells host Steve Curwood that when investors factor in those risks, present values worldwide could fall by 2.5 trillion dollars, but the worst-case scenario is far, far worse. (05:10)

I Feel the Earth Move

View the page for this story

Climate change is doing more than melting ice sheets. It’s actually changing the Earth’s rotation. NASA’s Erik Ivins tells host Steve Curwood that the planet resembles a large top wobbling on its axis as the weight of ice lifts, but the wobble has no major effects for humans. (00:06)

The End of Night

View the page for this story

Humans have always had a basic fear of the dark, but the advent of electric light in the late 19th century brought control over the night in the developed world. But with an explosion of light pollution blocking out the natural night sky in much of the world, author Paul Bogard tells Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer we might have gone too far and it might be harming our health. (08:25)

Conserving the Dark

/ Emmett FitzGeraldView the page for this story

The National Park Service protects the land, water, and wildlife in some of the most beautiful places in the United States. But Nate Ament, a park ranger based in Moab, Utah is working to protect another resource—darkness. In a world increasingly flooded with artificial night, a clear view of the night sky has become more and more rare. Reporter Emmett Fitzgerald takes a night walk to see the stars with Nate through Arches National Park. (10:00)

The Night Bird

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Most songbirds sing during the daylight hours, but it’s the Eastern Whip-poor-will that comes alive as the sun sets. BirdNote’s Michael Stein reads Henry David Thoreau’s account of the lovely nightjar bird’s song and notes how habitat loss is causing the population’s decline. (02:00)

A Prayer to Share Earth as a Commons

View the page for this story

Jesuit Priest Albert Fritsch has long called for “Earth Healing” through his website and work with advocacy groups in both Washington DC and rural Kentucky. Now, Father Fritsch speaks with host Steve Curwood about how he’s using his chemistry background to lead his parish in discussions about Pope Francis’s environmental encyclical, emphasizing the moral and religious relevance of protecting the Earth’s resources for all people. (14:45)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Alex Bowen, Erik Ivins, Paul Bogard, Nate Ament, Father Albert Fritsch

Reporters: Helen Palmer, Emmett FitzGerald, Michael Stein

CURWOOD: From PRI, it’s an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. The potential effects of global warming put investments at risk.

BOWEN: This is basically the impact that could take place right now today on the value of financial assets if market participants suddenly came to realize how the risks were panning out. It would be $2.5 trillion loss.

CURWOOD: But few investors are taking account of these potential dangers.

Also – bright lights from cities can block out the stars but a few pockets of darkness survive.

AMENT: A lot of visitors will say that it’s by far the most exciting and memorable part of their trip…seeing the Milky Way over my head every night when I slept out, or seeing the stars in the dark sky that I’d never seen before.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, innovating to make the world a better more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Climate Change Threatens Trillions Worth of Financial Assets

Coal mines in Wyoming. Coal stocks and bonds assets are risky given economic trends and the prospect of increased regulation on carbon. (Photo: Flickr Image Library CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, it’s an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Economists at the London School of Economics say denial of the risks of global warming, from rising seas to droughts to civil unrest, is promoting the overvaluation of certain financial assets – in other words, a bubble. Some of the risks have already been recognized, for instance, shares in coal companies have crashed, but these economists say the risks are much broader than the fossil fuel industry. Alex Bowen of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change at LSE, is co-author of this study published in Nature Climate Change. He estimates financial assets worldwide are presently overvalued by perhaps $2.5 trillion, and in the worst case, $24 trillion. And he says massive climate-related write-downs are not far off in the future, which would mean huge losses for investors who ignore the risks.

BOWEN: This is basically the impact that could take place right now today on the value of financial assets if market participants suddenly came to realize how the risks were panning out. So the best way I think of thinking about this is what would've happened had participants in financial markets gone to sleep one night as complete climates skeptics, woken up the next morning and realized the current state of climate science. What impact would that have had on the value of financial assets at that moment? And our central guess if you like is that it would be $2.5 trillion USD loss. But then if financial market participants realized that actually some of the uncertainties were going to be resolved towards the pessimistic end of the spectrum, then they’d mark down their assets as soon as they found that information. So we're talking about these losses to financial assets, they could take place today or tomorrow, basically as soon as people active in financial markets change their view of what's going to happen over the next hundred years or so.

Agribusiness is one of the sectors most vulnerable to the threat of climate change. (Photo: Asian Development Bank, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sounds like you're suggesting that when financial managers wake up to the risks of climate change to their assets, we could see a phenomenal sell-off, people wanting to get rid of those assets while they could get something for them. So the median projection is that we could lose $2.5 trillion dollars overnight and we could lose 10 times that if people are super-pessimistic.

BOWEN: Indeed that's the case. Now it may be that some of this value at risk as it’s called is already reflected in the current market valuations, but it's remarkable how many investment managers haven't actually looked at issues such as the prospects of fossil fuel companies in a carbon-constrained world. It's amazing how many people still doubt the climate science.

CURWOOD: So who would feel the impacts of these losses the hardest, the ones that you're projecting here?

Some economists worry that coastal real estate in towns like Miami could also be overvalued. (Photo: Daniel Chudosov, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

BOWEN: We didn't look at this in detail in the paper, but I think it's reasonable to suppose that the impacts of climate change would be fairly broadly spread, but some sectors would be hurt much more than others. I think that agribusiness would have particular problems because of the adverse impacts of climate change on agricultural productivity. Tourism is another one that's likely to be hit, and I think that amongst financial institutions wealth managers particularly exposed to any financial assets from poorer countries in the tropics would be worried about risks. Perhaps the sovereign debt of poorer countries from the tropics who are going to be hit much harder by climate change.

CURWOOD: What do you hope comes out of your paper, Alex?

Economist Alex Bowen is a Principal Research Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. (Photo: London School of Economics)

BOWEN: What I think is particularly important is that people who own or manage wealth look at the evolving states of climate science, climate economics, and keep an eye on whether scientists, for instance, begin to find that the climate is more sensitive to greenhouse gas emissions than they previously thought. We might get good news on that front. I'm not saying we're definitely going to see the pessimistic outcomes, but it’s surely very important for wealth owners and wealth managers to keep an eye on this kind of thing because it could have a very big impact on their portfolios, and they need to look at some of the sectors like agribusiness which would be particularly badly affected if climate change began to run away from us.

CURWOOD: Alex Bowen is a research fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics. Thanks for taking the time today.

BOWEN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read the paper in Nature Climate Change

- The London School of Economics

- About Alex Bowen

[MUSIC: Vusi Mahlasela, "Loneliness," The Voice (Ilivi Lebantfu), ATO Records/BMG]

I Feel the Earth Move

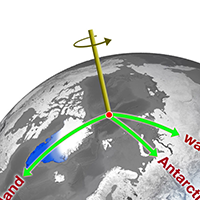

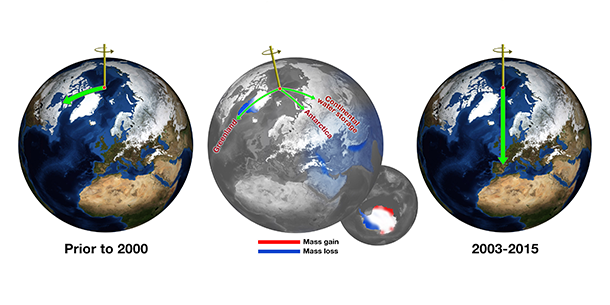

Before about 2000, Earth's spin axis was drifting toward Canada (green arrow, left globe). JPL scientists calculated the effect of changes in water mass in different regions (center globe) in pulling the direction of drift eastward and speeding the rate (right globe). (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

CURWOOD: As global warming advances, it’s not just investments that are affected, there are profound effects on our planet as well, with heat waves, melting ice sheets, sea level rise, and changes in rainfall and storm patterns. And a study from NASA published in Science Advances points to an unexpected result of ice in Greenland and the poles melting and running off into the oceans: It’s moving the axis of rotation of the entire planet. This wobbling was first noticed by Jianli Chen of the University of Texas at Austin. And to try to understand this better we spoke with the co-author on the new study, Erik Ivins of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in his back yard in Pasadena – welcome to the program!

IVINS: Thank you.

CURWOOD: I have to say I was surprised by the opening statement in your paper. You say the Earth's spin axis has been wandering since the year 2000. How can the axis which is just so fundamental to our planet wander?

IVINS: Actually, we know that it's been wandering for maybe about the last five million years at least, ever since the ice sheet started to build up in northern Canada and in Scandinavia periodically at periods of about a hundred thousand years, and as the ice sheets disappeared they left kind of a depression. It was sitting there. That's a mass deficit with respect to the average Earth and it causes the pole to want to wander in the direction of that little hole that's left there. So we do know that we have been recording the drift in that direction since about 1899 or so, but starting in about 1999 to about 2001 we started to see the Earth start to move in a new direction and that new direction really can only be explained by Greenland ice mass that is lost.

The relationship between continental water mass and the east-west wobble in Earth's spin axis. Losses of water from Eurasia correspond to eastward swings in the general direction of the spin axis (top), and Eurasian gains push the spin axis westward (bottom). (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

CURWOOD: Describe for me exactly what you mean by “the axis is moving”?

IVINS: Well, let's say that you have a toy top and you spin that top. When you start to spin the top, since it's very symmetrical, it will tend to nicely form just a single axis of rotation. But if you were to take a tiny piece of chewing gum and stick it on there, you would find out that this spin axis would slightly tip over. That's because the body is no longer symmetric. It has an off axis piece of mass on it and it's causing the moments of inertia to change. And this is what causes this strange polar motion. Just to give you another analogy: let's say that you were a baseball pitcher and you were frustrated that too many of your hitters were being able to figure out what your pitches were doing. Well, you would use this old technique called "foreign substance", either pine tar or a little bit of your own spit.

CURWOOD: This is not legal. This is not legal...a spitball, doctor!

IVINS: All the hall of famers are spitball pitchers. Now, what they're doing is they're changing the moments of inertia slightly so it changes the entire dynamical character of the pitch as it approaches that batter.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory is located at California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

CURWOOD: Makes it wobble and harder to hit.

IVINS: Well, it slightly changes the trajectory because the spin will change, and as the spin changes of course it tends to flutter around a little bit more in the eyes of the batter.

CURWOOD: So you folks are positing that human driven climate change plays a role in this wobble of the Earth’s axis but I understand initially that wasn't your hypothesis. It wasn't what you were looking for. What led you in this direction?

IVINS: Well, we were looking to build a software capability to connect calculations of ice sheet change so that we can project ice loss or gain for a period of about 200 years and try to predict what global warming will do to sea level rise. To improve that situation, we needed to include the Earth's dynamics and the gravitational effects that the ice changes would have on global seas. Then as a way of being able to do a reality check, we looked both that the work that Jianli Chen had done on Greenland and we also looked at the actual raw data that was coming from the international rotation service and we found it was a pretty close match especially when we included the details of Antarctica. And we also decided that it would be interesting to use the Grace mission data that determines how masses are changing on the surface of the Earth to include land hydrology. And once we included land hydrology, we found a near perfect match to the position of the Earth's spin pull.

Dr. Surendra Adhikari and Dr. Erik Ivins of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory researched how the movement of water around the world contributes to Earth's rotational wobbles. (Photo: courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech)

CURWOOD: And who is Jianli Chen?

IVINS: Jianli Chen is a researcher at the University of Texas at Austin. He is also an expert at hydrology and Grace, and he's the first person that really published a very nice paper explaining what the new drift direction was and that the Greenland ice loss was dominating this new direction.

CURWOOD: Wow. By the way, what is Grace? What's the Grace satellite?

IVINS: Grace satellite is a pair of satellites that follow one another and track one another, and they do such a good job of tracking one another with microwaves that they can tell when they either separate and when they get closer to one another. And when they get closer to one another and then separate again they're going over a mass anomaly and they're so sensitive that if there is a change in water underneath them they record that and then map that very, very well.

CURWOOD: This is so interesting. What do you think of the practical effects of the movement of the Earth's axis?

IVINS: There are really none because it is so small. We're suspecting that these changes are occurring at a meter, a meter and a half at the most per year. If you start to get up to about 100 kilometers, then you're changing the amount of solar radiation that's coming into some parts of the Earth so that can only occur and be of significance when we're thousands and thousands of times larger in terms of our scale.

Dr. Erik Ivins co-authored the recent paper, “Climate-driven polar motion: 2003–2015,” published in Science Advances. (Photo: courtesy of the Keck Institute at Caltech)

CURWOOD: So this is a tremendous wake up call, I guess for our civilization that anthropogenic human related climate disruption is actually changing how the Earth is rotating.

IVINS: Yeah, I guess you could say that. I think one of the things that Jianli Chen mentioned was it's just another strange thing that the climate does. It doesn't have a feedback that’s necessarily important for us, but it is just one of those things you can list on that list of "Oh my God! climate change really does that one?” Well, this is yet one of those.

CURWOOD: Erik Ivins is a senior research scientist at Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Thanks so much for taking the time with us, Eric.

IVINS: OK, thank you, Steve. It's a pleasure talking to you.

Related links:

- “Climate-driven polar motion: 2003–2015,” in Science Advances

- Video: Nasa’s Earth Minute: Greenland Ice

- NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at California Institute of Technology

- “NASA Study Solves Two Mysteries About Wobbling Earth”

[MUSIC: Victoria Williams “Wobbling” , Swing The Statue 1990 Mammoth]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – In search of the dark – and the distant stars it reveals… Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rick Braun “Coolsville”, Body & Should 1997 Mesa Blue Moon Recordings]

The End of Night

Light pollution in major cities prevent many people from experiences natural darkness and a clear night sky (Photo: Tom Bricker, Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's an encore edition of Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. More than half of the world’s population now lives in cities, and the glaring lights increasingly make the sky too bright to see the stars. That’s a concern for Paul Bogard, who wrote the book “End of Night” which examines the increasing use of light for public safety, which results in light pollution blanketing our world and blotting out the heavens. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Now one of the reasons that I think people have embraced light is basically this fear of the dark. Do you think that's really what's at the base of the growth in light?

BOGARD: Well, you know it's a complex problem, a complex issue but I do think that we have a basic fear of the dark. I sometimes laugh because I admit in the book that I'm afraid of the dark and people think, you're the guy who wrote the book on the value of darkness, how can you be afraid of the dark? But I think it's a perfectly natural thing to be afraid of the dark. I think what's not natural is to then compensate for that fear by trying to light up our nights as bright as our days and to think that we can somehow do away with darkness by turning up the lights ever brighter.

Paul Bogard met many dark sky enthusiasts who seek out the earth’s darkest places (Photo: Jay Raz, Creative Commons 2.0)

PALMER: But I think there is this feeling that with light will come security. You have this feeling of the murderer or thief sort of lurking in the darkness. And so, obviously, we turn on the lights to become more safe. Has it made us in that way more safe? Or does more light make us more safe?

BOGARD: Yeah, sure, I think that's really at the heart of it, and when you ask people, do we need all this light, people say often times, well, yeah we need it for safety and security, but the truth is that while some light can help us be more safe and secure and no one's suggesting that we just turn off all the lights, but what people are suggesting is that we don't need all this light for safety and security and that in fact when you have ever more light you often create more problems than solutions. Oftentimes when you have lights they’re too bright, they cast shadows where the bad guys can hide. There's so much light in our nights that are glaring lights that make it hard for us to see, and then also, too much light tends to create the illusion of safety. We think we can be reckless purely because it's light out and that's obviously not the case.

PALMER: So it basically destroys our night vision as well.

BOGARD: Yeah it really does. One of the most startling estimates that I found what I was doing the research for the book is that some 40 percent of Americans and Western Europeans never experience or rarely experience night vision. We're in the light so much that our eyes never switch to night vision.

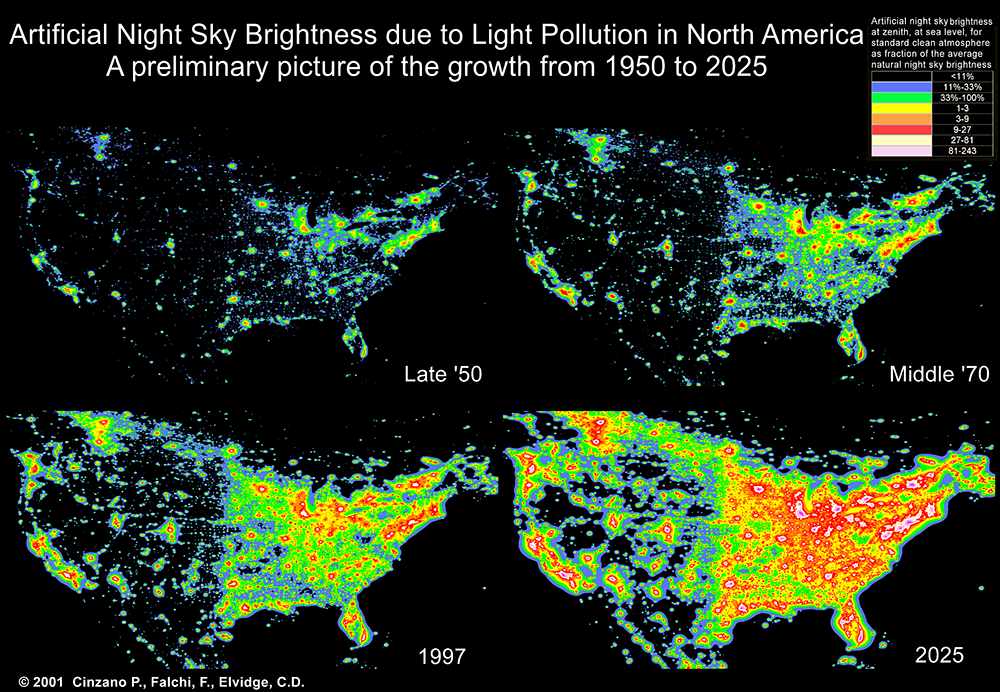

Growth in light pollution in the last 75 years (Photo: P. Cinzano, F. Falchi [University of Padova], C.D. Elvidge [NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder]. Copyright Royal Astonomical Society. Reproduced from the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astromical Society by permission of Blackwell Science)

PALMER: You tell that very sad story of somebody saying, “What are all those white dots up in the sky?”

BOGARD: [LAUGHS] Exactly and you know if you live in a major urban area, major city, you're not seeing anything close to the night sky that we ought to be able to see, and I had several nights when I was traveling for the book where, say, I was standing on a bridge in London and I looked up and I could count about 20 stars and that's just, that's nothing when it comes to the night sky.

PALMER: Well it's not only the inability to see the stars that the problem. You actually point out that this excess light is actually making us sick.

BOGARD: We're learning more and more. More and more research is showing us that light at night in fact is impacting our physical health and in three primary ways. It’s interrupting our sleep and contributing to sleep disorders, which are tied to every major disease that we're dealing with now. It's confusing our circadian rhythms, those internal rhythms that orchestrate our body's health and then perhaps most troubling it's impeding the production of the hormone melatonin. Melatonin is only produced in the dark and what scientists are finding is that a lack of melatonin in our bloodstream is linked to an increased risk for breast and prostate cancer. So nobody is saying, you know. that yeah, that light at night gives you cancer, but what everyone I talk to did say was we've evolved in bright days and dark nights just like all life on Earth and we need both for optimal health. To think that we can simply flood our nights with artificial light and have it not have an effect on our health is probably foolish.

The Bortle Scale (Photo: The International Dark Sky Association)

PALMER: One thing that I know night workers complain about is that they all put on weight. It seems to somehow in fact really upset the circadian rhythms in terms of digestion as well.

BOGARD: Yeah, it really does and I think you know the folks that are bearing the brunt of all this light probably most directly right now are those people who are working the night shift or rotating shifts and that happens to be more and more of us. And too often it's the poorer folks who need to work at night, but I talked to a number of folks who work the night shift who have put on weight and just say it's really really difficult to live this way. You feel exhausted all the time, you feel tired all the time and they can sense that it isn't right but they have to do it.

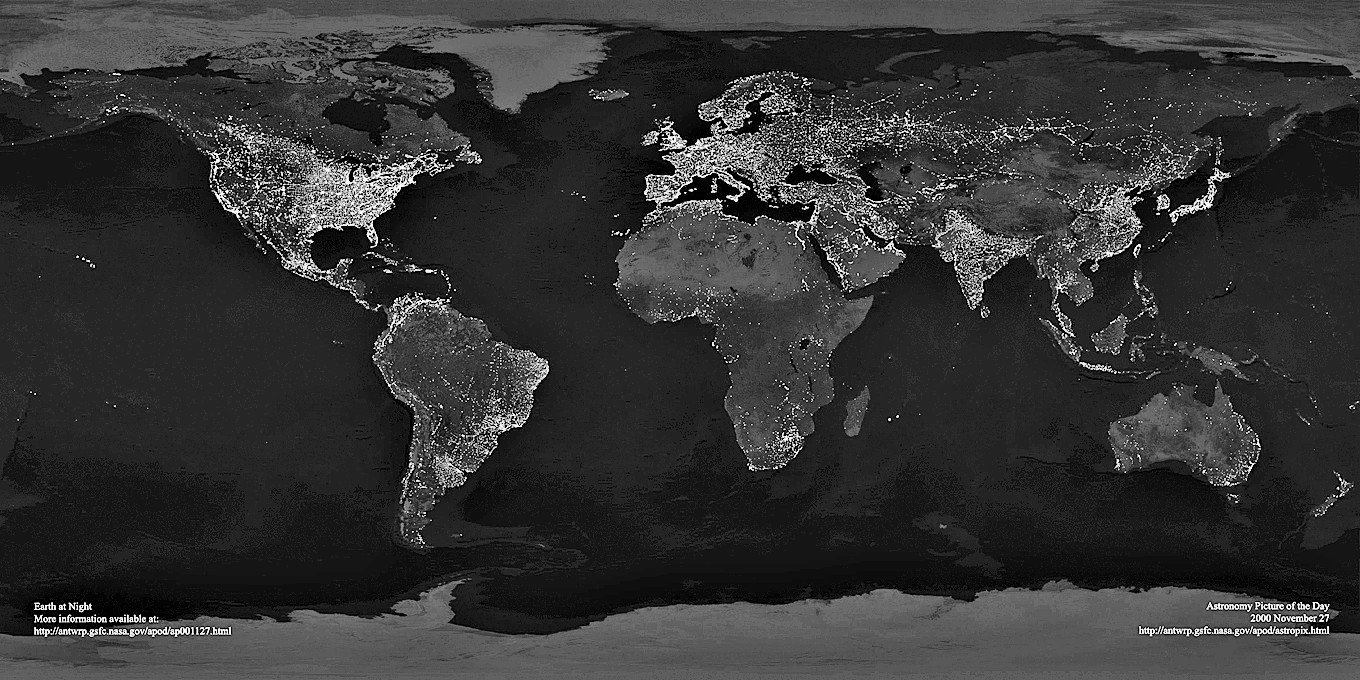

The earth at night (Photo: C. Mayhew & R. Simmon (NASA/GSFC), NOAA/NGDC, DMSP Digital Archive)

PALMER: Well even if we actually sleep in a theoretical dark room, there are all these sort of LED lights, the little lights on the alarm clocks by our bed. There are the lights on our watches, the lights on our phones. It's amazing if you just look around the bedroom—theoretically, the dark bedroom—what is still on.

BOGARD: [LAUGHS] It's true. We have a lot of little lights. And I think a lot of folks aren't even aware of how important it is to be sleeping in the dark, to pull those shades completely shut and to turn off the lights in the hall room and to, if you get up to use the bathroom in the middle of the night, to not turn that bright light on. One thing that researchers are seeing a lot of is that people are doing a lot of reading on the computer, on the tablet, their phone, what have you, right up to the time they turn off the light and go to sleep at night, and this keeps the production of melatonin from starting when it normally should. What scientists are finding is that it's the blue lights in the screen that's having the most negative effect on our physical health and a lot of the new LEDs that we're seeing in our streetlights and a lot of our gadgets are really heavy with this blue-rich white light that we really shouldn't be seeing in the night.

Excessive glare from artificial lights can actually make it more difficult to see people lurking in the night (Photo: George Fleenor)

PALMER: One of the things you're doing in your book is going around searching out these advocates for dark skies across the world. Actually there seem to be many of them. What did they advise or could we basically do to reverse this trend of ever brighter, ever brighter, ever more destructive?

BOGARD: Well you know I'm optimistic about it. I think there's a lot that we can do and it starts with the way that we use light and I like to say that light at night is not the problem, it's how we use it. So that is true in our homes where we can have light that is shining only downward, we can turn off our lights when we go to bed, that continues into our communities where we can have a lighting ordinance in our communities that will describe the kind of night that we want to have in the places that we live. Most of us don't want to live in places with glaring super-bright ugly lights. We prefer to have lighting that is subtle and nuanced and maybe even beautiful even as it provides us with the safety and security that we know we want. So, from the individual all the way up to the community and even on the statewide level there are things we can do right now to begin to control this.

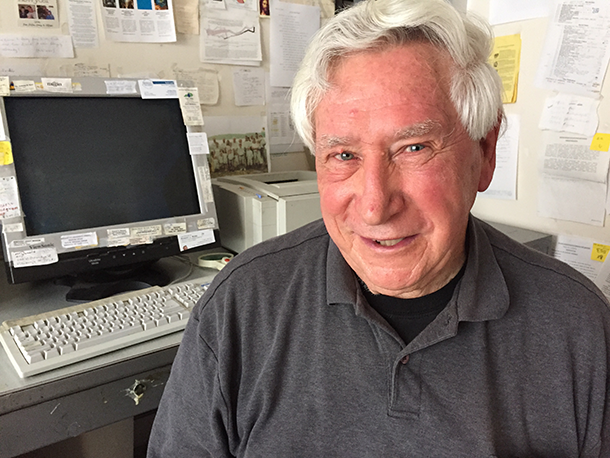

Paul Bogard (Photo: James Madison University)

PALMER: Things like downward pointing street lights and stuff like that you’re talking about?

BOGARD: Absolutely. One of the biggest problems that we have with our lighting, one of the, I guess, biggest basic problems is that we have light shooting in all directions right now, and we have light that is being sent straight into the sky and we have light that's being shined into our eyes as drive down the street and we have too much light that's just shining from one neighbor or one streetlight into our houses and none of that light is doing any good. In fact, it's just all wasted light. So simply by directing our light downward just to where we need it we can have a huge positive impact.

CURWOOD: Paul Bogard wrote the book “End Of Night”. He teaches English at James Madison University in Virginia and spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. Some conservationists are now also counting dark skies among other threatened resources and celebrating them where they still persist. Canyonlands National Park in Utah was named an International Dark Skies Park, and the Park Service is working to get a similar designation for nearby Arches National Park. Living on Earth’s Emmett FitzGerald went to see for himself.

Related links:

- Paul Bogard’s website

- Light Pollution Map

- Light Pollution And Astronomy: The Bortle Dark-Sky Scale

Conserving the Dark

The view of the cosmos through the South Window at Arches National Park (Photo: Jacob W Frank)

[FOOTSTEPS]

FITZGERALD: Tonight isn’t really the best night to see the stars. The moon is two thirds full above Arches National Park in Eastern Utah. But that hasn’t deterred my guide.

AMENT: My name is Nate Ament. I'm the Colorado Plateau Dark Skies Coordinator with the National Park Service. We’re headed towards the North Window, we’re going to do some stargazing and look at the landscape under the moonlight here.

FITZGERALD: This park is named after its signature red rock arches, or windows, so massive you could drive a fire truck under them. Nate’s been out here countless nights, but he says it still feels like the surface of Mars.

AMENT: I came out here for the first time when I was a kid, and this was just magic land for me. I mean it still is, but I just didn’t even know that landforms like this existed. It just boggled my mind. It’s totally otherworldly.

The night sky above Arches National Park (Photo: Jacob W Frank)

FITZGERALD: Nate points out the spot where the writer Edward Abbey parked his trailer when he worked for the National Park Service here in 1956 and ’57. Abbey’s field notes from that stint formed the basis his iconic book Desert Solitaire. Abbey wrote of his dark nights in Arches:

Leaving the flashlight in my pocket where it belongs, I remain a part of the environment I walk through and my vision, though limited, has no sharp or definite boundary. The night flows back, the mighty stillness embraces and includes me; I can see the stars again and the world of starlight.

[FOOTSTEPS]

We pass the North Window, a giant eye-shaped hole in the rock wall and head south. Nate’s wearing a headlamp tonight, and unlike Abbey’s flashlight, it’s red.

AMENT: Red light actually preserves your night vision. Your eyes have to adapt to the darkness and when you use a red light it doesn’t break down the chemical inside your eyes that allows you to see better in the night. So we use a red light for stargazing so we can preserve our night vision.

[FOOTSTEPS]

People aren’t used to it. It’s interesting when you get them out in a really dark place and let them dark adapt you get these people saying, “WOW I’ve never seen the stars like this before!” And I’ve never seen these kind of colors in the night sky, because they took the time to let their eyes adapt.

FITZGERALD: We arrive at the South Window, and Nate turns off the headlamp. The moon is bright, casting a silver glow across the sky, but there’s still plenty to see.

AMENT: So if you look straight above us here that’s is three stars right there, Altair, Deneb, and Vega, and those three make up the summer triangle. Cassiopeia is actually just behind the South Window here, we’re looking through the South Window into the cosmos beyond and we can see the constellation Cassiopeia. If it was just a little bit lower we’d be able to look just to the right of Cassiopeia and see just this faint little wisp of light and that’s actually the Andromeda galaxy, which is our closest neighbor. A little bit lower on the horizon we’d be able to see Sagittarius, which is if you will it's like the teapot, and the steam coming out of the teapot that’s the core of the Milky Way, it’s the center of our galaxy. And if the moon wasn’t out and the rock wasn’t in the way we could see that right now.

A composite image of the sky above Canyonlands National Park (Photo: Dan Duriscoe, used with permission)

FITZGERALD: It’s hard to complain about this rock though. [LAIGHS]

AMENT: [LAUGHS] Yeah I mean that’s the perfect picture frame for the cosmos. You can’t really complain about that.

FITZGERALD: For years the National Park Service has worked to protect some the most beautiful views in the country — Sentinel Dome at Yosemite, the old faithful geyser at Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon. Nate’s job is to protect the increasingly rare view of a clear night sky. It’s part of a recent initiative within the National Park Service.

AMENT: The idea goes back quite a ways to several rangers in the National Park Service who were really enthusiastic about getting people out under the night skies, and they wanted to know where the really dark places were and they wanted to know how to preserve those really dark places.

FITZGERALD: And so the Natural Skies and Night Sounds division of the National Park Service was born.

AMENT: And they measure how dark the skies are in parks. I think they’ve taken measurements in over 400 locations. So we have this really rich dataset of darkness all over the entire country.

FITZGERALD: One metric for darkness is called the Bortle Scale, and it rates the sky from 1 to 9.

AMENT: Where we are right now because of the light pollution from Grand Junction and Moab would be like a Bortle Class 3. Whereas if you went into the middle of New York City it’s a Bortle Class 9, which is the other end of the spectrum, the brightest of the bright, you can’t really see any stars.

FITZGERALD: Humans have lit up so much of the world that it’s almost impossible to find a Bortle Class 1 any more. But some of the darkest skies in the country are right here at the Four Corners where Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico meet on the high desert of the Colorado plateau. Canyonlands National Park, just down the road from Arches has been measured at a Bortle class 2, and was recently named an International Dark Skies Park. It’s the seventh on the Colorado Plateau to get that honor.

AMENT: And that’s by far the highest concentration of these parks in the entire world. There’s only 28 worldwide so we have 7 of them right here on the Colorado plateau.

FITZGERALD: With so much federally protected land on the plateau, Nate says there’s a chance to preserve a really large swath of darkness right in the heart of the West. He works with towns like Moab to cut unnecessary lighting and introduce technologies like light shields that reduce sky glow. Smart lighting isn’t really a hard sell when you explain how much money it can save. One town that’s been particularly forward thinking about its lights is Flagstaff, Arizona.

AMENT: There’s one study that estimates if the entire state of Arizona were to take up Flagstaff’s lighting practices it could save the state $30 million per year. So that gets people attention.

Arches National Park has over 2,000 natural stone arches, hundreds of soaring pinnacles, massive fins and giant balanced rocks. (Photo: Diana Robinson, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

[LAUGHS]

FITZGERALD: Nate says reducing light pollution isn’t just about aesthetics. There’s a growing medical consensus that overexposure to artificial light can disrupt human circadian rhythms, and may even contribute to health problems like diabetes and certain cancers. And the excess light impacts wildlife as well.

AMENT: There’s a lot of documented cases of bird migrations being disrupted by really bright white lights. Bats have their predator prey cycles disrupted because insects flock to these bright white lights. There’s a lot of interference in other predator prey relationships that can be really disruptive to certain ecosystems.

FITZGERALD: But more than anything else, Nate just wants to give the many people who live in over-lit cities a shot at seeing the night sky as Edward Abbey would have seen it.

AMENT: Two-thirds of the people in the world can’t see the Milky Way from where they live. And so you get an idea of how rare it is to come out and see these dark skies in places like Arches and Canyonlands, and you can see why people come from all over the world to see them. And a lot of visitors will say it’s by far the most exciting and memorable part of their trip when they go around the camp and ask, “What was your favorite experience, what will you remember most?” people say, “Seeing the Milky Way overhead overnight when I slept out, or seeing the stars in the dark sky that I’d never seen before.”

[FOOTSTEPS]

FITZGERALD: As we head back, we come across two men with binoculars looking up at the sky. Ken and Robert are east coast friends on a road trip through the west.

ROBERT: Well we came out because we’re looking for pitch dark. The moon is kind of spoiling it a little bit although it’s beautiful too, but we wanted to see as many stars as we could. Clear, no moisture, it’s beautiful. We weren’t going to leave here without coming out here at night.

FITZGERALD: Ken and Robert aren´t the only ones out here at night. Flashlights held by stargazers flicker on and off throughout the park. Robert says he really appreciates that Arches keeps the gates open after hours. This view is part of why he made this trip in the first place.

Author Edward Abbey described the Canyonlands as "the most weird, wonderful, magical place on earth—there is nothing else like it anywhere.” (Photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

ROBERT: It’s just cool. When it gets so dark that you can see the Milky Way clear, look at how far away you’re looking. You think about little things like how long it took that light to get here. Stuff like that.

FITZGERALD: As we walk back to the car Nate’s smiling.

AMENT: Yeah it’s super gratifying to see somebody and just talk to them and they’re from out of town and “what brings you here?” “Well I came out here for the dark skies and the stars” and it’s like, "Yes! I’m doing my job! Alright."

[FOOTSTEPS]

FITZGERALD: In the 20th century, conservationists like Ed Abbey worked tirelessly to protect the air and water and wildlife in parks like this one. And now Nate Ament is adding a resource for the 21st century to that list, a clear night sky like this one, spread out from horizon to horizon.

For Living on Earth this is Emmett FitzGerald in Arches National Park.

Related links:

- Canyonlands named an International Dark Skies Park

- Arches National Park

- Nate Ament is part of the Colorado Plateau Dark Skies Cooperative

- Abbey’s Desert Solitaire

- The Bortle Scale

- Light pollution adversely affects some wildlife

[MUSIC: Brian Eno and Harold Budd, Falling Light, Ambient 2 The Plateaux of Mirrors, Editions EG]

The Night Bird

Eastern Whip-poor-wills are not technically songbirds, but their calls function as a song. (Photo: Laura Gooch, Flickr CC)

[MUSIC - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: A bird who relishes the dark cover of the US forests is the star of today’s BirdNote, and the shrinking of those forests is having noticeable effects because it relies on tree cover to nest. Here’s Michael Stein.

BirdNote®

Eastern Whip-poor-will – Bird of the Night Side of the Woods

[Whip-poor-will song throughout]

In September of 1851, Henry David Thoreau wrote:

“The Whip-poor-wills now begin to sing in earnest about half an hour before sunrise, as if making haste to improve the short time that is left them.

[Whip-poor-will song]

Eastern Whip-poor-wills have brindled plumage, which camouflages them well amongst dead leaves and tree bark. (Photo: Jerry Oldenettel, Flickr CC)

…They sing for several hours in the early part of the night, then sing again just before sunrise.”

Clearly and continuously, the bird announces its name [Whip-poor-will song].

In summer to early fall, Eastern Whip-poor-wills breed in woodlands of eastern North America. Their camouflaged plumage blends seamlessly with dead leaves on the forest floor. At dawn and dusk and all through moonlit nights, whip-poor-wills sally out from tree branches to hawk flying insects.

Woodland habitat has greatly diminished for Eastern Whip-poor-wills, as forests become more fragmented. The National Audubon Society lists them among the Top 20 Common Birds in Decline. Protecting and restoring large expanses of forest are crucial for many forest species, including the whip-poor-will.

[Whip-poor-will song and crickets]

It remains, as Thoreau described: “…a bird . . . of the night side of the woods, where you may hear the whip-poor-will in your dreams.”

I'm Michael Stein.

Eastern Whip-poor-wills are part of a bird classification called nightjars. This group is known to be active during the late evening, night and early morning. (Photo: Richard Crossley, CC BY-SA 3.0)

###

Written by Frances Wood; revised by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Song of the Whip-poor-will (Eastern) [84871] recorded by W.L. Hershberger. BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producers: Chris Peterson/Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org September 2015 Narrator: Michael Stein

Related links:

- Whip-poor-wills on BirdNote®

- More about Whip-poor-wills on All About Birds

- Whip-poor-wills on Audubon’s Guide to North American Birds

[MUSIC: Balval “Molin Molette”, Le ciel tout nu 2013 Whaling City Sound]

CURWOOD: Coming up – We meet a Jesuit priest who helped inspire the environmental encyclical of Pope Francis. That's just ahead on Living on Earth – stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Miles Davis “Green Haze” , Green haze 1976 Prestige]

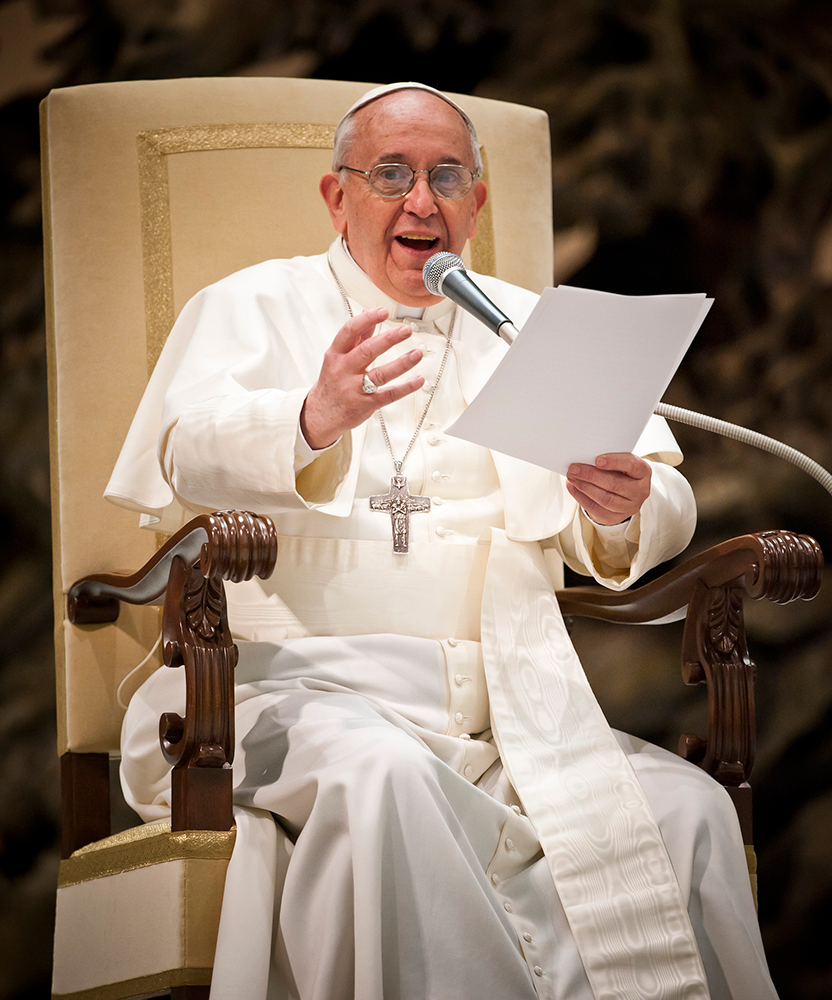

A Prayer to Share Earth as a Commons

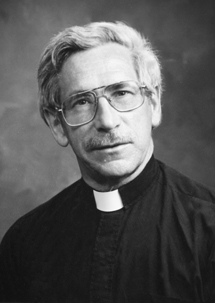

Father Al Fritsch, S.J. is the Director of Earth Healing, a website dedicated to providing daily reflections on simple living and matters of faith. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: It's an encore edition of Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Pope Francis, the charismatic leader of the Roman Catholic Church, is demanding action to combat the threat of global warming. The Pope’s encyclical Laudato Si framed climate change as an urgent and moral issue and it drove conversations in and out of the church. The Pope’s environmental concerns go back a long way, according to the web manager for EarthHealing.info. Earth Healing focuses on Catholic care for creation, and the manager says the pontiff visited the website before his election as Pope. And the website’s creator, Father Albert Fritsch like the Pope, is a Jesuit priest with training in chemistry. I spoke with Father Albert at the rectory of Saint Elizabeth Parish in Ravenna Kentucky, which is in one of the poorest counties in the US, not far from where he grew up on a farm.

FRITSCH: Well, my father was an extremely good farmer, and we took these very poor farms and turned them into very productive landscape, even crushing our limestone rock which was there and spreading it out, and of course we had rotation of crops, tobacco which was the normal crop along with mixed corn, hay and wheat. And that's what we grew on our farm along with vegetables and fruits and therefore we were mostly self-sufficient, and we never sent anything outside the farm as waste. We fed foodstuffs that were left over to the hogs and the chickens, everything was used up in our own area, what we had.

CURWOOD: So you decided to leave the farm. Where did you go?

FRITSCH: I went to college, went to Xavier in Cincinnati. It was a very good school. I got a undergrad and a masters degree there in chemistry.

Father Fritsch grew up on a farm in rural Kentucky where his family grew tobacco, corn, hay, and wheat, along with vegetables and fruits. (Photo: Todd Shoemake, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And you got a doctorate as well in Chemistry.

FRITSCH: Yes, I did, from Fordham, and went on to do a post-doctorate at the University of Texas.

CURWOOD: So what got you interested in the priesthood?

FRITSCH: Well, I saw people I really liked very much who were Jesuits. I also had a great problem with what chemistry usually involves and that is to go to a commercial institution, work for a company. I didn't like the idea of that. Academics - well that was good but I was hoping to do something that would apply the great gifts that we have with chemistry for the betterment of society especially for the poor.

CURWOOD: So what was the draw of the priesthood? Now you have a doctorate in chemistry, you're concerned about how people use chemistry, and you feel yourself being drawn to the priesthood and the Jesuit priesthood at that.

A coal train rolls by a few blocks from Father Fritsch’s parish in Ravenna, KY. Father Fritsch’s concern for the effects of coal mining on the landscape where he was raised eventually brought him back to rural Kentucky. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

FRITSCH: Well, it was to save our own souls, of course, is the first thing that we do it for, but also immediately it is to help all other people in some way, and I didn't see that a lot of the people who were connected to career jobs and trying to make a lot of profit in the work which they did, I didn't see that that was really the calling for what I was doing myself or for the field itself. I felt that science, if you look back upon it, a lot of people over a long period of history had contributed a lot to making chemistry what it was, and in seeing this it struck me that here is a Commons that we all have, but suddenly it's been picked up by some and used and made a fortune out. And why should it? Because was part of a Commons that we all had.

CURWOOD: Now, you finish up your doctorate and you decide that you're going to, well, help people, and you start to do some rather practical environmental things. What kinds of things did you do?

FRITSCH: Well, I began the work after my studies and I was still at University of Texas, met a young fellow in a march that we were on, and he was going to work with Ralph Nader as one of his hot shots for the summer, you know, and I asked him, "Well,” I said “I've been looking for something that would be more of a public interest field. Would you ask Ralph if he needed somebody like that." So he did, came back the next week and said, "Yes, go and have a connection with him and see if you can work out something." We started there at the Center for the Study of Responsive Law in 1970 and the next year we set up the Center for Science of Public Interest, with two other scientists who were working with Nader, and that field I stayed with in Washington for seven years and then decided that we really needed a branch that came closer to the poor of the country and so I had a Appalachia Science of the Public Interest which exists to this day, and so Ralph Nader has been very helpful to us in helping us get donations and things even to this day and so we've been friends ever since.

A strong supporter of Pope Francis’s encyclical on the environment, Father Fritsch hosts a series of discussions with his parishioners on its teachings. (Photo: Catholic Church England and Wales, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So you decided when you were in Washington you would come back to Appalachia where you were born and raised, to have a ministry here. Why?

FRITSCH: Why did I come back? Well, one of the first grants that we had received was from Jay Rockefeller who was then the treasurer over at West Virginia and he asked us to work on some surface mine issues for the state of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Kentucky, the different regulations related to them. And so from the beginning I began to see that strip mining was really affecting parts of Kentucky where I was from and we did that type of work in Washington for a period of time, but we moved back because Washington DC is surrounded by seven of the wealthier counties of the country and yet if we’re going to make a simple lifestyle that people have to go to and live, we better go back to where the poor people are and see if the challenge can’t be done there first. That's why I came back.

CURWOOD: So what was it like to come back here?

FRITSCH: Well people were interested in the fact that we were trying to do a simple place and therefore we set up an appropriate technology center in south central Kentucky. There we had compost toilets and we started growing intensive gardens, organic ones, quite concerned about the forest itself, making sure it was being taken care of well, and I got into some coal issues at the beginning but moved on into solar. We had the first complete solar house in America. We were saying that it isn't that we were just attacking what was being done wrong, but we have to look forward to a new economy that would be a renewable energy one, and so for 25 years I ran that center and I thought that was enough time, so I've come to doing more pastoral work in two of the small parishes.

CURWOOD: Why do you consider caring for the Earth to be a moral and religious issue?

Father Fritsch and Pope Francis are both members of the Society of Jesus; Pope Francis is the first Jesuit Pope. St. Ignatius of Loyola, depicted here in a painting by Peter Paul Rubens, founded the Society in 1534. (Photo: mark6mauno, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

FRITSCH: Because if we don't care for it, the vitality of the earth will be destroyed. This is the deepest of the pro-life issues, for if we don't have a living Earth, we cannot live on it ourselves, and so it's also got tremendous theological implications because we believe that Christ came to save the world, and what we have never considered is that we as part of his body are now asked to save the Earth. He is our redeemer. We enter into the very act of redemption.

CURWOOD: Why should Catholics in particular care about environmental stewardship?

FRITSCH: Well, not just Catholic but Christian people in general have been baptized in the Lord and that means that just as Christ loved the whole of creation, we are people who are like him in every way and therefore we imitate the Lord and our love for nature and for God's creation comes from the very part of our following that we commit ourselves to.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a bit about why this perspective of the Earth is important?

FRITSCH: It's very important because even though in the Acts of the Apostles, some of the very first communities brought together people who shared everything in need, the big trouble was in the last few centuries we have had Marxism, which took some of the same ideas really and imposed it with an atheistic background to it, but in all actuality the world is a Commons. God created it for all of us. We have found in the course of history that more of us working together can take care of it better than individuals can, and so now when we move to a society in which an immense amount of wealth can come to a few in a very short period of time, it becomes imperative for us to bring again the idea that this is a Commons and we cannot have billionaires and destitute people at the same time. It's a poorer community because Commons means that we share together and if people can't share but instead they sequester, they take everything to themselves and hold onto it, while others don't have enough, this destroys our society.

CURWOOD: How did you feel when you heard about the Pope's encylical on the environment?

On September 24th, 2015, Pope Francis became the first Pope to address a joint session of the U.S. Congress. (Photo: NASA HQ PHOTO, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

FRITSCH: At first, to be honest with you, I was nervous thinking that, well, he might not say enough. You know the Pope is a very busy man. How could you write a 100 page, 40,000 word document when you're doing everything that he's doing, but really when I look at his philosophy it's exactly the same as mine. I read that encyclical and I would not disagree with a single point on it. I may have arranged it a little differently because it's a very long document, longest encyclical ever written, but at the same time I think that everything that it says is good. But it also adds a burden. We've now got a duty to spread the word as much as we can. This is talking about the needs that we have on Earth and that we have a good tradition in his second chapter from our biblical tradition that we should do something about it and it's been misinterpreted, especially by those who want to make a little fortune in thinking that we could subjugate other people, you know. But the fact is that the time has come for us to share as a people in the world, not to look at ourselves as elite or different from others but that we are together with others.

CURWOOD: Tell me about your own parish's response to the Pope's encyclical.

FRITSCH: Well, they all liked the idea. In fact the person that called me a Communist and walked out one time and not only did he come back but he was one that asked that we do something about this, and my feeling is that a lot of people who are climate change deniers are really honest and good people. They don't realize what is happening, and therefore I feel like a special attention must be given with a certain amount of mercy we might say and care for those who have a difficult feeling that we have to change the status quo which they've gotten some good out of the past. If we combine a sense of mercy and pastoral care with a sense that we’ve got to change together, I think we could do more and I think this applies not only here but I really think most of my writing is directed because, see, I'm a social conservative and I am a fiscal conservative, but on political matters I differ. But I guess but I believe I call myself a true conservative because I believe it goes back beyond the capitalistic system and it has to include things which are far more sharing in our past than what we have today, and therefore if I can bring that point out to people, that they can break from their politicization, you might say the partisanization of these issues, which, when I started to work, the Republicans and Democrats were all together, in 1970 to 1980, I'd like to get back to that and get away from the idea that this is a political issue. This is something far deeper than that. It is a moral issue of which we all share.

Father Fritsch earned a Ph.D. in Chemistry before embarking on the path to priesthood. (Photo: Ed Uthman, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Let's see here. You give me a bit of a handout describing each of the chapters of the Pope's encyclical. I gather you're sharing this with your congregation.

FRITSCH: Yes.

CURWOOD: This is quite detailed and you have at one point, 10 American applications of the encyclical. So let's just briefly describe them. The first one is to read the encyclical...

FRITSCH: ...second the need for personal and domestic conversion. And conversion is a second big point. We have to convert ourselves from what we've been thinking in order to save our Earth. We just cannot save it by some of the ways that we've had in the past. The third is to organize and attend meetings and church gatherings and, of course, that's why we're setting up one, and this is a doctrine that I'm sending out on our website. Climate change deniers hold that well, it's still a battle going on, there's still people that deny it. Well, our answer is that that is a situation they are trying to set up in order to prolong the profit motivation that is accomplishing for the big energies, that is the fossil fuel ones, profits that will last just like they did in the past on the tobacco issue. Tobacco areas were really scientifically concluded back in the ’60s that there was something really wrong with smoking tobacco and what happened in between almost 40 years it was always saying that there was some denial occurring. The merchants were denying it and therefore they were holding back from having regulations. We are having the same thing happening with fossil fuel. The differences is there it shortened the lives of about three million people. But here we're talking about the very vitality of the Earth itself.

Father Fritsch’s work with the Center for Science in the Public Interest and Appalachia—Science in the Public Interest spanned more than thirty years. (Photo: courtesy of Father Al Fritsch)

CURWOOD: So this is the fourth point, to talk to people, those who regard themselves as climate change deniers. Now, what about your last call here?

FRITSCH: The last call is the fact that not every Catholic likes what the Pope wrote and we don't know how many there are out there, but the possibility is half of them in this country. We have far more deniers, climate change deniers in this country than they have in another parts of the world. The great possibility is many of them will do what some of our presidential candidates who are Catholic say and that is that this is beyond the Pope's expertise, but the answer is, “Oh, no, this is a moral issue and that's exactly where he needs to be and must stand there”. And we have to face the fact that we have to convert and have to proselytize you might say our own people to listen to what the Pope has to say, and not just dismiss it, because it's extremely important and they've got to talk about it within their family, within their church communities and we are hoping that other parishes begin to talk among themselves in an honest way about how we all have got to change our lives in order to save our Earth.

CURWOOD: Father Albert Fritsch is the Rector of St. Elizabeth's here in Ravenna, Kentucky. Thanks so much for taking the time.

FRITSCH: Thank you.

Related links:

- Father Albert Fritsch’s website, Earth Healing

- The Catholic Climate Covenant

- U.S. Catholic Bishops’ letter to Congress on the encyclical

- Center for Science in the Public Interest

- Appalachia -- Science in the Public Interest

- Pope Francis’ Encyclical

[MUSIC: Cindy Cashdollar/ Jorma Kaukone “Living In the Moment”, Slide Show ℗ 2004 Silver Shot Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering, Anica Green, Jay Feinstein, Emmett Fitzgerald, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Charlotte Rutty, Adelaide Chen, Jennifer Marquis and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe, Jake Rego and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

Find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and like us, please, on Facebook - It’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes fom the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth