April 7, 2017

Air Date: April 7, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Keystone Fight Renewed

View the page for this story

Fulfilling a campaign promise, President Trump’s State Department has approved completion of the Keystone XL pipeline. But pipeline builder TransCanada still faces significant hurdles in federal court and in the state of Nebraska. Jane Kleeb ,founder and President of Bold Alliance|Bold Nebraska, tells host Steve Curwood how worries about water safety have caused many citizens, farmers, ranchers, and Native American tribes to unite to oppose the pipeline’s route through Nebraska’s sensitive Sandhills area. (11:25)

Clues to the Long-term Effects of Gulf Spills

/ David LevinView the page for this story

An international team of scientists is studying the effects of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill – by looking back at another spill 35 years ago in the Gulf of Mexico. In this report, David Levin tags along as Mexican and American researchers unearth sediment cores from the ocean floor near the site of the Ixtoc oil well blowout that reveal how the seabed reacted. (08:30)

Yurok Tribe Losing Salmon and Way of Life

View the page for this story

The Yurok Tribe has lived along the Klamath River in Northern California for thousands of years, relying on the annual salmon run for food and revenue. But dams on the Klamath have created conditions for a deadly aquatic parasite that threatens to wipe out the vital Chinook run. Yurok Tribal Chairman Thomas O’Rourke shares what might save the salmon and fishing communities of the Klamath. (08:00)

Remembering Sir Derek Walcott, Nobel Prize-Winning Poet

View the page for this story

We remember the renowned writer Sir Derek Walcott, who died in March. The Saint Lucian poet focused on the sea and the Caribbean ecology, and in 1992, won the Nobel Prize in Literature. In this recording, Sir Derek reads his poem "Sea Grapes." (01:30)

A Blueprint for $1 Trillion Infrastructure Spending

View the page for this story

The Trump administration promises a $1 trillion investment to rebuild the nation’s infrastructure, but has yet to offer design or budget details. Host Steve Curwood spoke with former Massachusetts governor and 1988 Democratic Presidential nominee Michael Dukakis offers a vision of rebuilt and expanded infrastructure, including national rail and public transportation. (15:50)

BirdNote: Thieving Frigatebirds

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Some seabirds are brilliant at catching fish, but as Mary McCann explains, blue-footed boobies need to watch out for hungry thieving Frigatebirds. (02:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jane Kleeb, Thomas O’Rourke, Michael Dukakis

REPORTERS: David Levin, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Ranchers, Native Americans, and climate activists unite again in Nebraska to fight the Keystone XL pipeline.

KLEEB: This pipeline would open up a huge superhighway to export tar sands to the export market. This is not about, you know, providing tar sands to America. We don't think our property rights and our water and our climate should be put at risk so Canada can make a bunch of money.

CURWOOD: Tar sands, Trump and trouble for the climate all on the table.

Also our bridges and dams and railroads are falling apart and, despite the promises from Mr. Trump to rebuild, so far there is no budget commitment.

DUKAKIS: Do we need a stealth bomber? Which is going to cost us $300 billion dollars? Or might it make more sense to take that money and invest it in this country's infrastructure? I think the question answers itself.

That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Keystone Fight Renewed

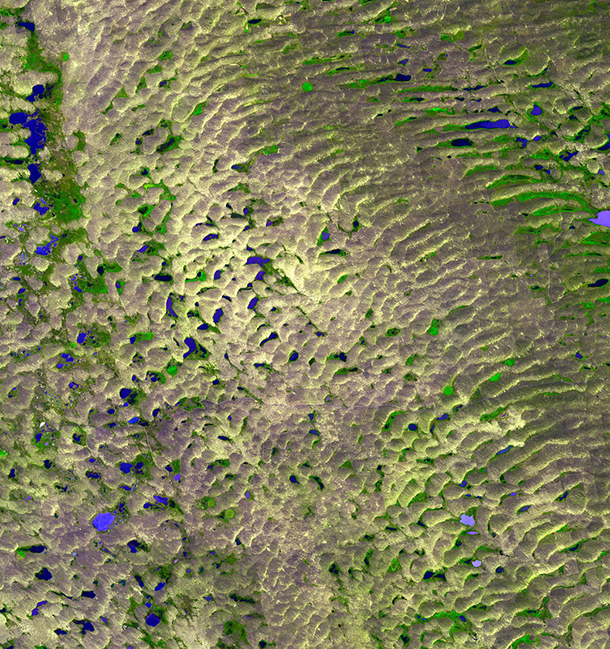

The Nebraska Sandhills, the largest sand dune formation in America, seen from NASA’s Terra spacecraft. The Sandhills and the underlying Ogalla aquifer could be impacted by a potential heavy crude oil spill. (Photo: NASA/GSFC/METI/ERSDAC/JAROS, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Thanks to President Trump, TransCanada may soon proceed with the controversial Keystone XL pipeline, designed to link Alberta’s tar sands with Texas oil refineries. President Obama rejected the pipeline on grounds it would aggravate global warming, but the Trump State Department overturned that ruling. Groups including the Natural Resources Defense Council, Center for Biological Diversity and Bold Alliance have sued, alleging that move violated the law. TransCanada also needs a permit from the State of Nebraska, but activists there say the pipeline would be harmful to Native American communities and would threaten the Sandhills ecosystem. This is a fragile part of the prairie where water recharges the massive Ogallala aquifer which stretches from West Texas to South Dakota, and serves 30 percent of irrigated crops in the US. Jane Kleeb is the president of Bold Alliance/Bold Nebraska. Jane, welcome to Living on Earth!

KLEEB: It's always good to be with you.

Jane Kleeb (Photo: Mary Anne Andrei / Bold Nebraska)

CURWOOD: First, Jane, to what extent did you and your fellow opponents of the pipeline see this approval coming?

KLEEB: We knew from the campaign trail that President Trump would eventually approve the federal permit for Keystone XL. You know, despite him saying that he was going to require TransCanada to use 100 percent American made steel which Keystone does not use - It's actually 70 percent foreign steel - but we figured he would find a way to wiggle out of that and approve the pipeline, and that's exactly what he did for the federal level.

CURWOOD: And how do you feel about that?

KLEEB: You know, it's frustrating because we think that President Trump is completely ignorant about what is happening here on the ground. He's never talked to a single one of us, and he prides himself on being in touch with rural voters and standing up for world people, and yet he's throwing us completely under the bus.

CURWOOD: Jane, take a moment for us, please, to explain why this State Department permit doesn't seal the deal for Keystone XL and why the Nebraska is the next hurdle that TransCanada must get over.

KLEEB: You know, the great news is, is that in our country we still have something called states’ rights, and for oil pipelines they are permitted at the state level. And so TransCanada still has to get a state permit to cross into our state for the Keystone XL route. It's a very vigorous process. It'll actually be the first time that the public service commission reviews an oil pipeline route in Nebraska. It's no surprise probably to listeners that we're an ag state and not an oil state. We have a lot of corn and cattle, not a lot of oil pipelines. No one really knows how it's going to end because the PSC has never really had to do this before.

Bold Nebraska used large-scale crop designs as part of their efforts to persuade former President Obama to reject the pipeline. He did so on November 6th, 2015. (Photo: Dakota Aerials / Bold Nebraska)

CURWOOD: And just to remind people about our unusual Nebraska politics are, you have just one house for your legislature, the unicameral, as you call it, and people aren't elected to that by political party, but they are apparently to this Public Service Commission.

KLEEB: Yeah, so Nebraska is so interesting. You know, I often try to remind people that, you know, we have not only this nonpartisan unicameral where there's no party identification on the ballot, but we have 100 percent public power, so we don't have any private utilities in our state. It's all run at the very local level with boards that you can run on as a citizen. We're a very populist, independent, local-control state. That is the lifeblood of the backbone of our politics. So, this is going to be interesting, right? Because it is a partisan body at the public service level.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the membership of the Public Service Commission. They’re the ones that need to approve this. Who are these folks, and what kinds of indications have they given so far?

KLEEB: So, there's five commissioners. There's only one Democrat, but the two commissioners that represent a lot of the counties along the proposed route are very independent. One in particular, Mary Riddle, is a rancher, is a very strong independent voice, and so we're going to make our case directly to them, following the rules that they set out, which TransCanada has the burden of proof through this process to prove that this is in the public interest of Nebraska. So we think that we can clearly show that this threatens our water, threatens livelihoods, and takes away property rights.

CURWOOD: Now, when the state department approval was announced, President Trump said he’d call Nebraska’s governor, make sure that he'd approve the pipeline route to the state, but how much power does Nebraska's governor have in that decision? You have the Public Service Commission, right?

KLEEB: Yes, so Governor Ricketts has absolutely no say in the pipeline route decision. So President Trump can call Ricketts anytime he wants. They can even go to a Cubs game, which is what the Ricketts family owns. They have lots of money, and TD Ameritrade is actually one of the big banks that is financing the Keystone XL Pipeline. So, Ricketts clearly supports the pipeline, but ranchers and farmers who elect a lot of Republicans in our state are firmly opposed to this pipeline because of the eminent domain and because of water. So thankfully Ricketts does not have a say in the decision.

CURWOOD: So, what could the federal government do anything to override the Nebraska Public Service Commission, should it decide that Keystone XL is not in the best interest of “huskers,” you call yourselves?

KLEEB: Yes! You know, so the huskers are keeping an eye on Congress. We do know that Congress could attempt to override state rights. We think that that obviously would set a very dangerous precedent for Republicans, to be overriding state rights, but we know that that is a possibility that they could do. Our state legislature could also attempt to undo the powers of the Public Service Commission when it comes to pipelines, although I don't think they will do that. They actually tried that before, when we had a different governor, and that landed the unicameral and the Governor in court, and landowners won in that case. I'm not sure they'll try that again, but I don't put anything past Governor Ricketts and Trump with their desire to get this pipeline in the ground. I think one of the possible outcomes that could happen in the law that got passed was, they have to consider an existing corridor, and TransCanada has an existing corridor in our state. They have Keystone 1 pipeline that went into the ground under George Bush in 2008. So, the outcome of this could be, no new land taken out of production, eminent domain is not used, the Ogallala aquifer not at risk, but TransCanada still gets a second pipe, but they have to be forced to put it next to Keystone 1.

At a Bold Nebraska rally on March 22nd, 2017, landowners and citizens gathered at the Public Service Commission office in Lincoln, Nebraska to deliver their intervenor applications (Photo: Marty Steinhausen / Bold Nebraska)

CURWOOD: So, tell me about this route that TransCanada wants now, compared to this existing route that they already have a pipeline on.

KLEEB: You know, the current route that they're proposing, that's on the table for the Public Service Commission to review, cuts right through the Sandhills which is a very fragile, sensitive soil in our state and where the vast majority of cattle producers are because that's also where the Ogallala Aquifer recharge zones are, meaning the aquifer is very close to the surface, and all of our drinking water supplies really come from the aquifer, and it's only possible because the Sandhills essentially act like a big sponge and replenishes the aquifer in those recharge zones. So, it's like the worst possible place you could be putting a maximum-pressure, maximum-capacity tar sands pipeline because we know, when tar sands hits water, it's very difficult, if not impossible, to clean up. It's very different than traditional oil because it's heavier and has lots of chemicals. It sinks. So, we are really arguing that it is not in the public interest to shove that pipe through the Sandhills and the aquifer and that, if it gets approved at all, it should be definitely forced to go to next to their Keystone 1 route which is on the eastern part of our state, away from sensitive soils.

CURWOOD: How does your organization feel about it getting approved at all? In your view, how positive would it be to have a Keystone XL, if it ran, say, at the eastern end of your state, not risking the water?

KLEEB: You know, our major concerns always with Keystone have been the risks to water and property rights of farmers and ranchers. You know, we don't believe that eminent domain should be used for private gain, especially a foreign owned corporation. But we also acknowledge and have from day one way the risks of tar sands and climate change. This pipeline would open up a huge superhighway to export tar sands to the export market.

Members of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and guests gathered at the prayer camp to oppose Keystone XL, in March 2014. Native American tribes in Nebraska are once again gearing up for a fight against the pipeline’s route through their sacred sites. (Photo: Matt Sloan / Bold Nebraska)

This is not about, you know, providing tar sands to America. We don't use tar sands. It's a much heavier form of oil, and we have enough oil with the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota. So, this is really about Canada being in a very difficult spot. They don't have export-market capability where they are right now. The tar sands are landlocked, and going through the United States was the best way for them to get this stuff on the export market to make lots of money. We don't think our property rights and our water and our climate should be put at risk so Canada can make a bunch of money.

CURWOOD: Jane, take a moment to tell us about the Native American tribes there. Which ones have a stake in this, and what are they doing in opposition to Keystone XL?

KLEEB: The tribes are a critical part of our alliance. You know, we do lots of actions with the tribes. We call ourselves the Cowboy and Indian Alliance when we do actions together, and so, I think, you know, sometimes people look at the movies and think that folks in kind of the rural areas are at odds with tribes, when in fact in our state and in South Dakota, the ranchers and the tribes really did work hand-in-hand, especially in the early days, and now we see everything is at stake - our water, our livelihoods, their sacred burial grounds along the route. And in particular for Nebraska, the Ponca Trail of Tears is directly crossed and threatened by this pipeline.

So, for the past four years, we've worked with the Ponca tribe, and we've planted their Ponca Sacred Corn inside the route as medicine. It's now certified by the USDA as Ponca Sacred Corn, and so we think that we have lots of actions like that, that we will continue to lift up, not only to bring people together but if we need to file a court challenge to protect that Ponca Sacred Corn, we will do that as well.

CURWOOD: So, cowboy or Indian, you're all cornhuskers, huh?

KLEEB: [LAUGHS] That's right, that’s right. We all wear Wranglers and we all wear boots.

CURWOOD: So, what do you understand the Native American tribes are going to do in response? There's the courtroom and the encampments that we saw at the Dakota Access Pipeline protests.

Volunteers with Bold Nebraska plant Ponca sacred corn along the proposed Keystone XL pipeline route (Photo: Mary Anne Andrei / Bold Nebraska)

KLEEB: Yes, so the Rosebud Sioux tribe has already set up their Spirit Camp, and they had a Spirit Camp on Keystone XL route the last time we fought it, and it was really a center point for people to pray, and they have 12 teepees up, and they’ll continue to hold that encampment, and people will come in and out of that encampment. And then we do know that the Ponca and the Winnebago and Pawnee and the Omaha here in Nebraska are also going to be very engaged in the Public Service Commission level as well as actions.

You know, we have some creative actions planned for inside the route. Just to give you a example, like, we built a solar barn inside the Keystone XL route last time around because TransCanada's contracts say that you can't have any permanent structures inside. So, that was us and the tribes' message to the president saying, “You’d have to tear down clean energy and a symbol of our livelihoods in order for this dirty pipeline to go in”. So, you know, we work hand-in-hand with the tribes, and I think that's one of the things that actually terrifies companies like TransCanada is that there's no dividing us. Whether it's the tribes in the United States, the First Nations in Canada, the farmers, the ranchers, and our tree huggers, we are a united front.

Bold Nebraska built a “solar barn” in the proposed pipeline path to send a message that building the pipeline would be a choice to tear down renewable energy and a symbol of Nebraska economy. (Photo: Mary Anne Andrei / Bold Nebraska)

CURWOOD: Jane Kleeb is the Founder and President of Bold Alliance/Bold Nebraska. Jane, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

KLEEB: Thanks for visiting with us.

Related links:

- Lincoln Journal Star: “PSC approves nearly all petitions for KXL intervener status”

- The Nebraska Public Service Commission’s oil pipeline approval process

- About the Nebraska Sandhills

- CNN: “Trump administration approves Keystone XL pipeline”

- The Hill: “Green groups sue Trump over Keystone XL approval”

- About Jane Kleeb

[MUSIC: Abigail Washburn, “Song Of the Traveling Daughter” on Song Of the Traveling Daughter]

CURWOOD: Coming up...a California salmon run on the brink of total collapse is upending the way of life of local Native Americans. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Abigail Washburn, “Backfoot Cindy/Purple Bamboo” on Song Of the Traveling Daughter]

Clues to the Long-term Effects of Gulf Spills

The C-IMAGE crew lowers the multi-corer into the water (Photo: David Levin)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The deadly Deepwater Horizon blow-out spewed huge amounts of oil into the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, and scientists have been working ever since to understand its long term effects. Now, an international team of scientists from C-IMAGE -- That’s the Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem -- has been looking to a different spill that happened 35 years ago off the coast of Mexico for some clues, and as David Levin reports, the aftermath of that disaster is giving them insights into the future health of the Gulf of Mexico.

[BOAT ENGINES START.]

LEVIN: It’s just before dawn, and I’m stepping into a tiny fishing boat in Ciudad del Carmen, Mexico. We’re sitting in a small inlet, hidden by thick mangroves, and nearby, big fiberglass yachts rock gently in the water. They’re from all over Mexico, even Louisiana and Delaware, and they’re drawn here by one thing: oil. Just offshore, there are hundreds of wells in the Gulf of Mexico. Today, we’re heading 15 miles off the coast, into the heart of those wells, to meet up with a Mexican ship called the Justo Sierra.

Adriana Gaytán-Caballero, a PhD student at UNAM (the national university in Mexico) and Travis Washburn, a PhD student from Texas A&M, siphon out the water near the top of a core sample to collect tiny worms and other creatures so they can study the health of the ocean floor. (Photo: David Levin)

[ENGINES REVVING, WATER SOUNDS, RADIO CHATTER]

LEVIN: Aboard this ship, two dozen Mexican and American researchers are studying a massive spill that happened here more than three decades ago. In 1979 a well called Ixtoc 1 exploded, spewing millions of barrels of oil into the water. Until the Deepwater Horizon, it was the biggest spill ever to hit the Gulf of Mexico. But scientists still don’t know exactly how it affected the environment, and this what they’re looking into now. By studying how this region recovered, they’re hoping it’ll say something about the impact of major spills decades after they happen.

[ENGINE STOPS, RADIO CHATTER IN SPANISH]

LEVIN: An hour later, I arrive. At 160 feet long, the Justo Sierra dwarfs our little fishing boat, and the ship’s captain has to improvise to get me aboard.

[SPANISH SPEAKING ON RADIO]

ORTEGA-ORTIZ: So he recommends that you pack your gear so you can use all your hands. Every step you take, you really need to commit.

LEVIN: Okay.

LEVIN: That’s Joel Ortega Ortiz from the University of South Florida. He’s my guide on this trip and the first one to scale a 20 foot rope ladder the crew drops over the side.

ORTEGA-ORTIZ: There’s the ladder…

LEVIN: A wave kicks up and rocks the boat, and Joel sees his chance. He swings onto the side, and in a few steps, he’s onboard.

[CLANKING SOUNDS OF CLIMBING LADDER]

And now it’s my turn. And, by the way, climbing the side of a ship while holding a microphone is way harder I thought.

[CLANKING SOUNDS OF CLIMBING LADDER]

HOLLANDER: Welcome aboard man, good to see you!

LEVIN: You too!

LEVIN: David Hollander is one of the scientists who organized this cruise. He’s the principal investigator of a team of researchers called C-IMAGE, and he’s here to collect sediments from the ocean floor.

HOLLANDER: Understanding the events that happened in the Ixtoc will give us a vision for what we can expect in the northern Gulf of Mexico over the next couple of decades around the Deepwater Horizon.

LEVIN: To get those sediments, Hollander and his team are using something called a multi-corer. It’s a cone-shaped cage of pipes, about 10 feet tall. Looks like an unfriendly jungle gym. When it hits the bottom, twelve plastic tubes inside it sink down and fill with mud.

Polychaete worm found in a core sample (Photo: David Levin)

ROMERO: So we want to collect the sediments from the bottom because the sediments record the history of what happened in the area.

LEVIN: Isabel Romero is a geochemist at the University of South Florida.

ROMERO: So, every time that we pull and get sediments some of us are gonna look at the chronology. Some of us gonna look at the organics, the chemistry, to see what is the condition of the area.

LEVIN: Sediment cores act almost like tree rings. Each season a new layer of mud settles onto the ocean floor and leaves a record of what happened in the water. Researchers like Romero and Hollander will look at the chemistry of the mud, while others focus on the tiny animals inside.

[CRANE WHIRRING, DECK SOUNDS]

LEVIN: As the multi-corer settles back on the deck, a swarm of scientists gathers. They carefully remove and store the cores, but first they siphon water delicately off the top of each one, collecting the organisms that live there. Adriana Gaytán-Caballero is a Ph.D. student at UNAM, the national university in Mexico City.

GAYTÁN-CABALLERO: [TRANSLATION] We work with organisms that are associated with sediment. Then what we see is which type of organisms are most abundant. You may see some groups, some families, that are more abundant than others if there’s some event that’s different from what they are used to.

[GAYTÁN-CABALLERO SPEAKING IN SPANISH]

LEVIN: Some of the animals she finds are microscopic. Some are as big as an earthworm. But they all tell her something about the environment. Certain worm species can only live in pristine mud, but others are attracted to oil, and thrive in places that would kill off other animals. Studying which ones are living there can tell her how the marine ecosystem’s doing.

[WATER SPILLING ON DECK; CLANKING]

VOICE #1: Anyone know what that is?

VOICE #2: That is a polychaete.

VOICE #3: Oh, a worm! Travis?

WASHBURN: That is exactly the kind of stuff we’re after. That’s about as big as they get down there, actually, so that’s very easy to pick out, very easy to identify when you see it, so those are the ones we like to see…

LEVIN: Like the Mexican team, Travis Washburn studies worms in the sediments. He’s a Ph.D. student at Texas A&M.

The Justo Sierra research vessel (Photo: David Levin)

WASHBURN: The two things that are constant in our work are death and gravity. So, everything dies, and everything sinks.

LEVIN: In other words, contamination in the water eventually goes away, but bits and pieces of contaminated mud and dead animals settle onto the ocean floor. Those sediments stick around, and so do the worms that live inside them.

WASHBURN: So they’re basically a record of the overlying water column. You can use the worms and the sediment to tell you everything that’s happened above them.

LEVIN: But sediment samples don’t always paint a clear picture. In some cases, those layers of mud can be mixed up by currents or burrowing animals, so it’s tough to figure out where oil landed in the past. Looking at chemistry and animals can offer some clue, and David Hollander has a few more tricks up his sleeve. He’s borrowed an old technique used by oil workers, a UV light. It makes crude oil glow bright purple.

[DOOR SHUTTING, QUIET ROOM]

LEVIN: Inside a dark cabin, he shows me how that works. On the table, he pours out a few tiny drops of crude, and immediately wipes them up.

HOLLANDER: Oil. No oil. Right? Looks clean to you?

LEVIN: It does.

HOLLANDER: Okay, but if I was “crime scene investigation, CSI: oil spill”, I would put on my UV lamp, and… Oh…Oh!

LEVIN: Oh, yeah!

HOLLANDER: I missed a spot.

LEVIN: Yeah, it just jumps right out.

HOLLANDER: See it right there?

LEVIN: That’s incredible.

HOLLANDER: Yeah.

LEVIN: It’s hard to miss. A bright, glowing spot where the oil used to be. And without the UV light, we never would’ve seen it.

David Levin (Photo: David Levin)

HOLLANDER: In this instance, even very, very faint amounts that you can’t see fluoresce very distinctly.

LEVIN: So, if there’s a band of oil that you can’t see with the naked eye, you’ll be able to spot it with this.

HOLLANDER: Exactly. That’s why we use it.

LEVIN: At each site, Hollander splits one of the cores and scans it with the UV lamp. This method gives the team a quick-and-dirty way to evaluate each site and let them know if they need to come back for more samples later. They’ve only got two weeks aboard the Justo Sierra—so they need to know at a glance where to focus their efforts. It’s not the last time they’ll be out here, though. There are a few more cruises planned over the next three years, on both Mexican and American ships.

Hollander hopes this collaboration will open up new insights into the Gulf as a whole. He says getting the big picture’s essential for planning how both nations will respond to the next spill. After all, an oil slick doesn’t just stop at the border.

HOLLANDER: I think there’s a globalization of these issues. The Mexican government and the Americans realized that they have potentially a problem that is shared by both countries.

LEVIN: And it’s an urgent problem. Right now both countries are drilling in waters that lie right on the border. By studying how both Ixtoc and the Deepwater Horizon spill have affected the Gulf, the C-IMAGE team wants to inform policy makers in the US and Mexico. As more wells are built offshore, this research will help lay out the environmental dangers that come with them.

HOLLANDER: I think that’s principally one of our major goals. These are shared marine resources. We just want to make sure that we are good stewards of these common resources that are owned by all of us and manage them appropriately.

LEVIN: For Living on Earth, I’m David Levin.

Related links:

- Video: The C-IMAGE multi-corer in action

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute: Ixtoc I Oil Well

- The C-IMAGE website

- David Levin’s production company, Mind Open Media

[MUSIC: Entrain, “North Shore Drift” on Can U Get It, T. Major/J. Fuller/B. Alex, Dolphin Safe Records]

Yurok Tribe Losing Salmon and Way of Life

The mouth of the Klamath River is a busy hub for salmon on their way to spawn further inland. Yurok tribal lands encompass a 44-mile stretch of the river beginning here at the Pacific Ocean. (Photo: Linda Tanner, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: When the ice sheets retreated in North America about ten thousand years ago, indigenous peoples in the temperate rainforest that sprung up on the west coast from northern California to Alaska built societies dependent on salmon along the great rivers. Today most of the great trees of that rainforest in northern California are gone, as are most of the fish, pushed even faster toward extinction by the construction of dams. And now the Yoruk Tribe, that lives near the Oregon border, itself is losing its way of life, as the annual run of Chinook salmon from the Pacific into the Klamath River is on the verge of collapse.

Thomas O’Rourke is Tribal Chairman.

O'ROURKE: The Klamath River is our lifeline. We have depended on this river since time immemorial. Our stories go back to the time of darkness, our creation stories as Yoruk people. I growed up, born and raised here on the Klamath River, and as a child there was a lot of salmon. We had runs when I was a child that don't exist here anymore. I learned to the fish at a very young age, at probably about seven or eight years old. When I was a child, we didn't have much money, and the land provided about 90 percent of our food. Our roads are terrible here, and our roads would go out and sometimes we couldn't get out of here for weeks at a time, and if we didn't have food in jars, we did not eat. We relied on the game animals, the deer and the elk, the salmon which come from the river, the eels, the steelhead, the sturgeon, these are what I growed up to know how to eat and what kept us alive, what sustained us.

Chinook salmon, the largest species of salmon, spawn in Alaska. Their range stretches south all the way to California’s central coast. (Alaska Fish Habitat Partnerships, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: In a good year, what would the salmon count look like on the Klamath?

O'ROURKE: In 2000 or so, we had over 100,000 fish allocation, which allowed us to both catch fish for subsistence as well as to have a commercial season, which our people very much depend on, you know, because of the lack of job opportunities that are here.

CURWOOD: And what does the salmon look like today?

O'ROURKE: You know, when they told us our numbers, last year was bad. I mean, bad. We had trouble swallowing our numbers last year. We got 6,000 fish which isn't even enough for one salmon a person, for a tribal member. This year, we have a tenth of that. So, we have a little over 600 fish allocations for harvest, and our tribe is the largest tribe in the state of California with right around 6,200 tribal members, and we have 650 fish to sustain ourselves.

It's hard to understand my emotions, you know, of how I feel and our tribal members emotions, how they feel. You know, all of sudden we're told we're not going to be able to fish, you know, when we've fished all of our lives. The fish had always been there, you know, at least some kind of numbers. Well, this year is probably the lowest that I've ever knowed it to be.

Our river is sick, water quality being a major issue, water management being a major issue, and so we are in the process of putting together a fix that we see that we can attain.

CURWOOD: I understand that the Yoruk tribe conducted studies investigating the presence of an aquatic parasite on local fish population. How prevalent is this parasite and what has its effect been on the river's fish?

O'ROURKE: C Shasta is, it’s a parasite. They multiply inside the polychaete worm, and then it spreads across the floor of the Klamath River, and that's the one that’s been really infecting our salmon when they are juveniles. And it's due straight up to poor water quality, management, flows, dams.

We have four dams that we're working on to remove. And that what they do is that they incubate for this parasite. You know, it likes the warm water. It likes everything that them dams have in it, so the fertilizer, the byproducts. And so, it is infested badly. The disease rate has gone sky high, and now we're starting to see the impacts of this disease that is caused pretty much by man.

Advocates have been fighting for river dam removal for years. In 2006, Klamath Basin Tribe members and allies staged a rally at the bi-annual meeting of the International Hydropower Industry -- Hydrovision -- calling for the removal of PacifiCorp’s four Klamath River dams. (Photo: Patrick McCully, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: How much would it help if the dams were removed?

O'ROURKE: Well, we'll get our natural flows. Right now we get warm water off of the top of the dams. You know, the cold water doesn't come down which the fish very much need. It's hot here. It gets hot. It gets up near 110 degrees. It also stops the fines from coming down. You know that in the past all the spawning material, the gravel, the fines, you know, have been washed out, and the dams are stopping new fines from coming in, new gravel so the fish can spawn. So, it's imperative to get these dams out. There's four major dams that are causing most of the problems upstream.

We have been working since right around 2000 working towards dam removal. In the year 2010, Pacific Corps made its final decision to remove the dams. And that's big news for us because, once the dams are removed, then we can begin the real healing process for the river, and we will have a much better quality of water.

Quality of water means everything. You take a couple of fish and you throw them in a fishbowl, goldfish. You put them in a little bowl, and they'll do fine, and the water can be pretty warm. But if you throw a few more in there, you know, they're going to start to die. If you take and you put an oxygen hose in there, you know, they'll do fine, and you can throw some more fish in there. Then, they'll still do fine. But if you take a couple of ice cubes and put some ice cubes in that little fishbowl along with the oxygen, then, you know, you can fill that bowl up with fish, and they'll do fine.

CURWOOD: What are the plans for removing the dams? How soon are they coming down?

O'ROURKE: In the year 2020, the dams are scheduled to come out. Many stakeholders pulled together to make this happen. It's something that people said was impossible 20 years ago, 15 years ago, 10 years ago. People say it's pretty much impossible, but I see them coming down.

CURWOOD: Aside from undamming the river, what else could help restore the fish?

O'ROURKE: We were put here in the beginning as gardeners, the caretakers. So you can look at the river as a garden, and it's not just the water and the salmon directly, you know. It's the forest, it's everything in the ecosystem that ties together to make the river healthy. So, you can't just fix one component. Many components need to be fixed, erosion control because of the poor logging practices.

Yurok Chairman Thomas P. O'Rourke Sr. speaks with Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell at the signing of an agreement made last year to decommission four Klamath River dams. (Photo: Yurok Tribe/Facebook)

We have to address it across the board. When the forest is restored, then our spring waters will be restored, our ground waters will be restored. It all works together. It's a complex big picture. If the river dies, we die as a people, our way of live dies, our society it becomes extinct. And so, we will restore and revive our fisheries and our river.

CURWOOD: Thomas O'Rourke is the Chairman of the Yoruk Tribal Council in northern California. Thanks so much for taking the time Mr. Chairman.

O'ROURKE: Thank you very much and have a good day.

Related links:

- Times-Standard: “Klamath River salmon season faces closure due to ‘unprecedented’ forecast”

- Indian Country Media Network: ‘Nightmare’ Yurok Salmon Fishery Collapse

- NOAA: “Commerce Secretary Pritzker declares fisheries disaster for nine West Coast species”

- Yurok Tribe website

[MUSIC: Entrain, “Mo’ Drums/Can You Get It” on Can U Get It, R. Loyot/T. Major/J. Fuller, Dolphin Safe Records]

Remembering Sir Derek Walcott, Nobel Prize-Winning Poet

Sea grapes, whose scientific name is Coccoloba uvifera, are native to coastal beaches in the Caribbean and can be fermented into sea grape wine. (Photo: Cayobo, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: On March 17, one of the most gifted and renowned poets of the last century departed his native St Lucia to sing eternally among the bards on Mount Olympus. Sir Derek Walcott celebrated his Caribbean heritage and ecology, railed against its colonial history, paid constant homage to Homer, and won a McArthur genius grant and the Nobel prize. Here is Derek Walcott himself with “Sea Grapes."

Sir Derek Walcott OBE was awarded the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature (Photo: Bert Nienhuis, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

WALCOTT: That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband's

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa's name

in every gull's outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant's boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

CURWOOD: Derek Walcott and his poem "Sea Grapes."

Related links:

- The text of “Sea Grapes”

- NYTimes: “Derek Walcott, Poet and Nobel Laureate of the Caribbean, Dies at 87”

- Derek Walcott reads the beginning of his critically-acclaimed epic poem “Omeros”

- NYTimes analysis of “Omeros”

- About sea grapes (Coccoloba uvifera)

[MUSIC: David Foster, “Water Fountain” on Songs Without Words, Windham Hill Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...Michael Dukakis on options for a trillion dollar investment in American infrastructure. That’s next on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Burt Bacharach, “The Windows of the World” on Music By Bacharach, Universal Music Special Markets]

A Blueprint for $1 Trillion Infrastructure Spending

Successfully advocating for the high-speed Acela train, which began running from Boston to Washington, D.C. in 2000, was one of Michael Dukakis’s major achievements after his tenure as Governor of Massachusetts. (Photo: Ryan Stavely, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

On April 3, a seemingly minor derailment at Penn Station in New York City led to monstrous delays affecting hundreds of thousands of people in the New York area and up and down the east coast. You see, like much of America’s infrastructure, the antiquated rail system at Penn Station is overloaded and under maintained.

The Trump administration promises to invest a trillion dollars to fix rails, roads, bridges, and transit, but so far it hasn’t put out any money where its mouth is. There is bipartisan support for infrastructure investment, and no one wants it more than former Massachusetts governor and Democratic presidential nominee, Michael Dukakis. Governor Dukakis now teaches at Northeastern University, and he’s a long-time advocate of public transit and a former Vice Chair of Amtrak. Michael Dukakis joins us now from Los Angeles where he’s a visiting professor at UCLA.

Welcome to Living on Earth, Governor.

DUKAKIS: Thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, in your view what's the state of the U.S. infrastructure right now?

DUKAKIS: It’s lousy and getting worse. While we're gonna spend another 60 something billion dollars on a military budget, which is already enormous and is financing a defense system involving 837 American bases in 150 countries, and we can't repair our bridges. I think that's crazy. I think this increase in the defense budget is crazy, and in the meantime the rest of the world is going right by us. High-speed rail, excellent highways. You go to other countries, it's a little embarrassing to come back to the United States.

CURWOOD: So, now, why did the American Society of Civil Engineers rate our national infrastructure at a D+? It's practically flunking.

DUKAKIS: Might be generous because we're not maintaining it. I don't think we need any more highways in this country. We need a very strong investment on public transportation and high-speed rail, especially in our cities.

Michael Dukakis, a longtime advocate for public transportation, has some thoughts and advice for Trump on his $1 trillion infrastructure plan. (Photo: Northeastern University)

You know, I mean, Greece has got an infrastructure that looks a hell of a lot better than ours these days. With all of its problems and all of its struggles economically, those highways are in superb shape. The metro in Athens is remarkable and probably better than any public transportation in any city in the United States. And that's true all over the world. Go to Spain. Not a wealthy country, but it's two and a half hours now from Barcelona to Madrid. Used to be four. Now it's two and a half, and in the meantime, we're standing still.

CURWOOD: Now, during the campaign, Donald Trump, the candidate, promised he would fix railroads, the bridges, airports, hospitals, roads, and now is promising to invest a trillion dollars in infrastructure. What could one actually do with a trillion dollars, do you think?

DUKAKIS: Well, let me begin, Steve, first by saying that Trump has never identified the money he's talking about. Look, this country is currently running a deficit of a half a trillion dollars at the end of the Obama administration, at a time when we're getting very close to full employment, and where we ought to have a surplus in the federal treasury. And he proposes not only tax cuts primarily for the wealthy, in the billions, but he's going to spend a trillion dollars on infrastructure. Where is going to get it? Infrastructure has been conspicuous by its absence in the first couple of months of this administration, and I don't think we have any present prospects for anything serious here, unless he's going to run a current deficit of a trillion dollars, in which case it raises interesting questions about whether or not this country can ever pay its bills.

You know, we did have a handsome quarter of a trillion dollar surplus when Bill Clinton left office, and in point of fact, if you will remember, Clinton, in his last State of the Union address, proposed a plan to reduce and eliminate the national debt in 10 to 12 years, and it was serious. And had Al Gore – Well, he was elected -- but had he in fact taken office, we today would have virtually no debt. Instead we have an $18 trillion dollar national debt. Under this guy, it's probably going to go to $20 trillion. Where's the money going to come from for infrastructure? I have no idea. I don't think he has any idea.

CURWOOD: If the money could be found, Michael Dukakis, what would be your top priorities for America's infrastructure?

DUKAKIS: A first-class, national, high-speed rail system and excellent public transportation, mostly rail-based, in the major cities in this country. Those would be my top two. I mean, the interstate highway system is pretty much completed now. It's got to be maintained, and that's important, but I’d begin with first-rate, modern, speedy ground transportation on rail in the nation's major metropolitan areas and, of course, nationally.

CURWOOD: By the way, the latest Trump budget zeroes out Amtrak funding.

DUKAKIS: That's correct.

CURWOOD: How much sense does that make?

DUKAKIS: None. None whatsoever and totally inconsistent with what he's been talking about. Point of fact, as you point out, in the campaign, he was talking about building our rail system. Amtrak is actually the national rail system which requires less subsidy than any other national rail system. Amtrak makes more of its money from the fare box than any other national rail passenger system in the world.

And yes, in point of fact, national rail gets subsidies, but think of the subsidies that highways get. I mean, think of these numbers. Right now, highways in America get something in excess of $40 billion dollars from the federal government every year. Air gets $16 billion. Amtrak is down to a few hundred million, and about 85 percent of its expenses are paid for by passengers and system revenue. That's pretty remarkable, and I don't think most people understand this. So, it's doing exceedingly well. On the other hand, we've got a new administration pledged to build our rail system, right? Pledged to fix our infrastructure and its budget, zeroes out Amtrak. Now, does the president know that? I don't know.

CURWOOD: What would a comprehensive high speed rail system cost in America, do you think?

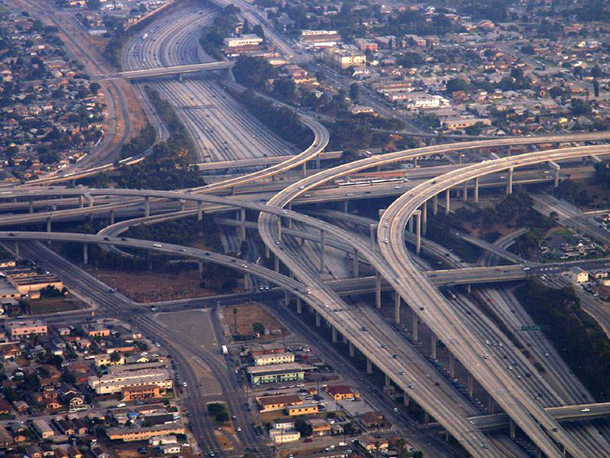

Interstate highways like these in Los Angeles dominate the transportation landscape in California. The city is currently focusing federal funds to improve the metro and regional connector systems. (Photo: Storm Crypt, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DUKAKIS: Well, when Barack Obama took over he asked for $10 billion to start it, and he got it from the first Congress, which, remember, was a Democratic Congress that first two years before Republicans came back and took it over. I would think somewhere in the range of $100 -$150 billion, but the states are deeply and actively involved in this. When the Obama administration asked for proposals from the states for that first $10 billion, Steve, they were overwhelmed. I think they got a $100 billion in requests. So, you're talking, I would think, in the range of $100, $200 billion and then a continual investment to make it better and better and stronger and stronger. But compared to what we're spending on the military, I mean, that's a rounding error.

CURWOOD: Michael, what about integrating rebuilding America's infrastructure with urban development and redevelopment? I'm thinking of better pedestrian spaces, bicycles, new vehicles such as driverless cars.

DUKAKIS: Well, that's part of it. But I think you can rely pretty heavily on states and local governments to do that kind of thing. And in point of fact, Steve, right now, here in Los Angeles, the voters of Los Angeles County have voted not once but twice to increase their sales taxes, to invest at long last in a first-class, rail-based transit system.

I just toured the so-called Regional Connector out here, which is a part of this major investment in transit, and it’s well underway. It's underground, at some point 100 feet underground. It will fully integrate and connect the entire Los Angeles transit system. And once that happens, in addition to major expansions of their transit system, this city is going to be one of the most impressive in the country, if not the world. And it's long overdue, needless to say, because the traffic situation here is horrendous. And a great deal of this is being financed by local taxes. On the other hand, it is getting some federal assistance, and that's pretty much the way these projects have been financed in the past. So, this partnership between the states and the local governments on the one hand and United States Department of Transportation on the other has worked quite well just as long as the feds are picking up their side of the bargain.

CURWOOD: Umm, Michael Dukakis, you were governor of Massachusetts for three terms.

DUKAKIS: Indeed.

CURWOOD: And famously, you rode the public transportation from your office on Beacon Hill out to Brookline where your house is, the Green Line in the Boston area. And, by the way, I think in that period of time, riders said that it ran better than before and perhaps after.

DUKAKIS: Dramatically so, they say. [CHUCKLES] But you'd be surprised at what you learn as a governor on the transit system. I mean, people would come up to me and say, "Hey, Governor, can I talk to you?" I learned more about what was going on in my administration on the street car than I did in the State House.

CURWOOD: And given your experience with Amtrak and the T, the MTBA in Boston. I imagine you've heard plenty of arguments against transportation infrastructure spending during your career. Talk to me about some of the most common challenges you've faced and what you would say to opponents right now.

DUKAKIS: I don't see the kind of opposition now, Steve, that we had 25 or 30 years ago, when we were still kidding ourselves that more and more highways could solve the problem. In fact, as you know better than anybody, we came dangerously close to building a kind of California-style freeway system in, on, and over the city of Boston, which in my opinion, would have destroyed the city. And you were there, reporting on this, when we had a 10-year battle over whether or not we would build a master highway plan. Fortunately, we stopped it, and then, thanks to a sainted man named Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr., who at that time was Majority Leader and soon became the Speaker of the House, we were the first state in the country to be able to use our interstate highway money for public transportation. It had never been done before. You couldn't bust the Highway Trust Fund, remember?

The Green Line is one of several light rail lines that make up the MBTA subway system in Boston. When he was governor, Michael Dukakis was famous for commuting on the Green Line to work at the Massachusetts state house in downtown Boston. (Photo: Jasonic, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

It was gasoline tax money. It had to be spent on highways. We were the first state to be able to break that and ended up with a big chunk of federal money, which had been allocated for highways, which made it possible for me to really invest heavily in what was a decrepit old transit system. I mean, I was riding streetcars when I first became governor that had been built in 1942, and we changed all of that, which just gives you some sense of what you can do when you have the resources to go out there and do stuff. But like everything else, you got to keep investing in it, and you got to have excellent managers.

But, I don't know of a mayor in the United States of America of a major city that isn't strongly advocating for major investment in his or her public transportation system. And Los Angeles is a good example of this. We've had two mayors, Antonio Villaraigosa and now Eric Garcetti, both of them strong proponents of investing in this new and very exciting, rail-based transit system out here in Los Angeles, and they're very typical of mayors all over the country.

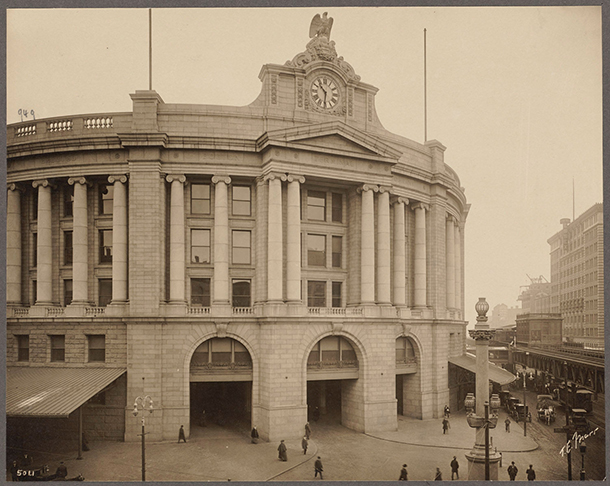

CURWOOD: You know, Speaker O' Neill, Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr., was famous for saying, “All politics is local”. And people listening to us may not know about the Boston transportation grid, but one of the things about Boston which is very odd when it comes to railroads, is that you could take a railroad all the way from Miami, Florida, to what's called South Station in Boston, but if you want to go on to New Hampshire or Maine, you've got to get out and go across town to the other railroad station. There's no link.

DUKAKIS: Right.

CURWOOD: I understand your latest project has been advocating for such a link. Why don't we have it? What do you think would be necessary to get it done as an example for the rest of America?

DUKAKIS: It was part of the so-called Big Dig plan which started with my first term in 1975, and that project was planned with a double rail line right down the middle of it. I mean, if you're going to rip up the entire city, that's the time to connect the two stations, right?

And, by the way, this is not a problem unique to Boston. You go to Paris, they originally had four railroad stations, right? And why? Because the railroads were run by private companies in those days, and every company wanted its station.

So, in Boston, New York-New Haven-and-Hartford wanted and got South Station. Boston-and-Maine then got North Station. Then there was this gap of a mile. I can show you legislative commission reports going back to 1910, ’12, ‘15 advocating for the connection. It didn't happen for a variety of reasons. Finally, I got elected in 1974, came in 1975. We started working on the Big Dig plan, and obviously, one of them was this double rail line right down the middle of it.

We then went to Washington, and the Reagan administration fought us tooth and nail on that project. Ronald Reagan actually vetoed the provision of the transportation law that would have financed the Big Dig. And, thanks to Tip [Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr], we had plenty of votes to override him in the House, but there was a real battle in the Senate, and for a variety of reasons we had to back off on the rail thing. After all, it was taking a precious lane for automobiles out of that project.

We did finally get two-thirds, so we proceeded with the Big Dig. As you know, it took too much time and cost too much money, but we never did the rail connection. Crazy. I mean think what it would do for the transportation system not only of metropolitan Boston but the entire northeast because we're talking about high-speed trains coming up to South Station as you know where they stop. Then you got to go over to North Station to get on the [Amtrak] Downeaster which takes you to Portland, Maine.

This is not unusual. You look at major cities all over the world. All of them have these 19th century stub-end stations, and they are all connecting them. In Europe -- Zürich, Stockholm, Malmo, Paris, of course. In Asia, you go to Japan, go to China, they're doing this on a regular basis.

From the archives of the Boston Public Library, the above photo shows Boston’s South Station, built in 1900. South Station connects Boston with New York, New Haven and Hartford by rail. (Photo: Boston Public Library, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some people say the opposition to public transportation funding is the perception by many people that public transit is for "them", for somebody else. “I'm gonna to ride in my car and go exactly when I feel like it. So, if there's going to be public transit, it has to be for those people over there”. How common is this, and how does one confront this?

DUKAKIS: Well, I don't think it's a problem these days. I mean, go to New York. It's not just poverty stricken people riding their transit system. Everybody does. I mean, Los Angeles, get on the new Expo line and take a look at the people that are riding it. These are not poverty stricken people. I mean these are just folks that want to get from home to work and back again. I think we're by that one. I think now, it's a question of, are we prepared to do some serious planning and investing in the national rail passenger system and excellent metropolitan transportation systems? And I think we are.

CURWOOD: So, Governor, you're saying that sort of contempt for public transportation is now out of date, certainly among millenials living in the city, but how do you persuade the GOP to get involved?

DUKAKIS: Fortunately, there are a number of Republicans in the Congress that understand this and are very supportive of this, and it's been a bipartisan majority that has really supported transit and rail investments. And I think when all is said and done with this Trump budget, you will see significant support for Amtrak in that budget and significant support for public transportation.

CURWOOD: Including the Tea Partiers?

DUKAKIS: Not including the Tea Partiers, but the Tea Partiers for the most part don't represent districts that have major, urban, metropolitan areas. But fortunately there are 50 governors, all of whom are very concerned about transportation as well.

CURWOOD: So, when it comes to public transit, build it and they will come, huh?

DUKAKIS: Yes, if it's good, if it's well maintained, it's well managed, if it's clean, attractive, and that's what we're seeing in this city and that's what we're seeing in cities all over the country. We just need more of it. Do we need a stealth bomber which is going to cost us $300 billion, or might it make more sense to take that money and invest it in this country's infrastructure? I think the question answers itself.

CURWOOD: Michael Dukakis is a former Democratic nominee for President of the United States and former governor of Massachusetts. Thanks so much for taking time with me today.

DUKAKIS: Great to talk with you.

Related links:

- NYTimes Editorial Board: “Missing: Trump’s Trillion-Dollar Infrastructure Plan”

- American Society of Civil Engineers report card history

- The Boston Globe: “State asks for bids in $2 million North-South Rail Link Study”

BirdNote: Thieving Frigatebirds

A frigatebird attacks a seabird for its meal. (Photo: Neil Winkelmann)

[MUSIC - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: One of the most glorious sights of tropical oceans is the vision of the Magnificent Frigatebird soaring over the waves. But as Mary McCann points out in today’s BirdNote, sometimes the way these fork tailed creatures behave is, well, less than magnanimous.

http://birdnote.org/show/frigatebirds-kleptoparasitism

BirdNote®

Frigatebirds’ Kleptoparasitism

[Featured bird sound/audio]

MCCANN: Some birds are masters at catching fish. In the warmer regions of the world’s oceans, large seabirds called “boobies” plunge headfirst into the water, snatching fish in their dagger-shaped bills.

But as a booby flies up from the waves with a fish now in its gullet, there may be another big seabird, a frigatebird, waiting overhead, with its eye on the booby and on the booby’s fresh catch.

[Red-footed Booby aggressive call, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/6036, .32-.33]

Airborne Frigatebird. (Photo: José Zayas)

Now begins one of nature’s great chase scenes. The booby flaps full throttle away from the frigatebird, but there’s no escaping. With a light body suspended on long, narrow wings and a long, scissor-like tail to match, the frigatebird is faster and more agile. It lopes up behind the frantic booby and with its long, slender, hooked bill, clamps onto the booby’s tail or wing-tip. Thus snagged in mid-air, the booby flails. A crash is imminent, unless it surrenders what the frigatebird wants. So it disgorges the fish it’s just captured. The frigatebird releases the booby and swiftly snatches the free-falling fish.

[Magnificent Frigatebird, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/136232, 0.04-.06]

Fortunately for boobies, frigatebirds don’t steal all their meals. Most of the time, they hunt their own seafood, perhaps a squid snapped from the ocean surface or a flying fish as it skims across the waves.

But now and again, when a chance comes up, they’ll take it.

I’m Mary McCann.

[Magnificent Frigatebird, http://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/136232, 0.04-.06]

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York.

6036 recorded by Robert J. Shallenberger and 136232 recorded by Martha J. Fischer.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Sallie Bodie

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org March 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

Video of frigatebird kleptoparasitism: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ifes66o4t7s

Another good source is http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Fregatidae/

http://birdnote.org/show/frigatebirds-kleptoparasitism

CURWOOD: And for photos, soar on over to our web site, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Listen on the BirdNote website

- More about Frigatebirds from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds

- Another BirdNote about Frigatebirds

[MUSIC: Cecil Payne Quartet, “Bosco” on Casbah]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Kit Norton, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our theme. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth.

And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth